Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

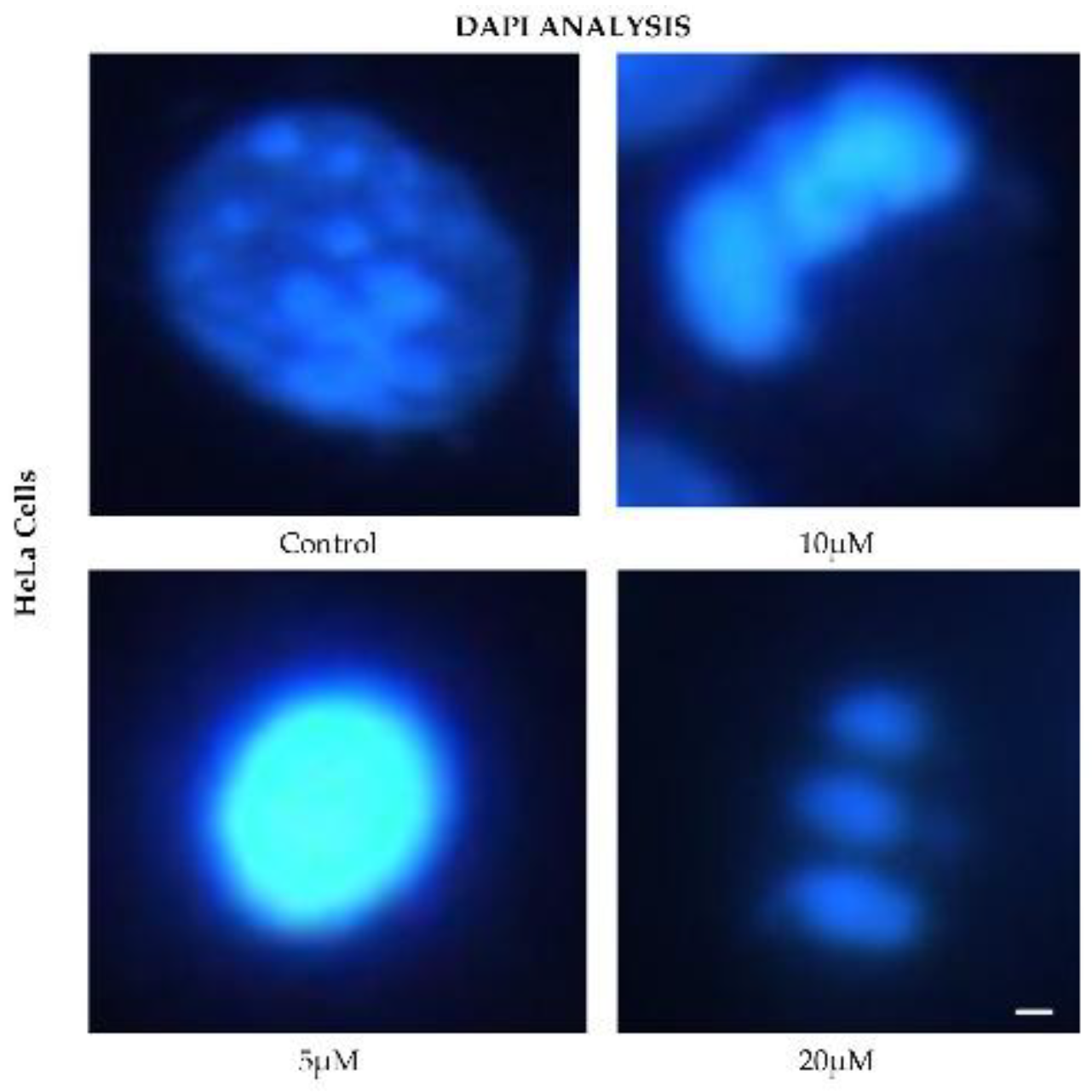

2.1. CBD Induces Morphological Changes in Cancer Cells

2.2. CBD Decreases Nuclear Fluorescence Intensity in Cancer Cells

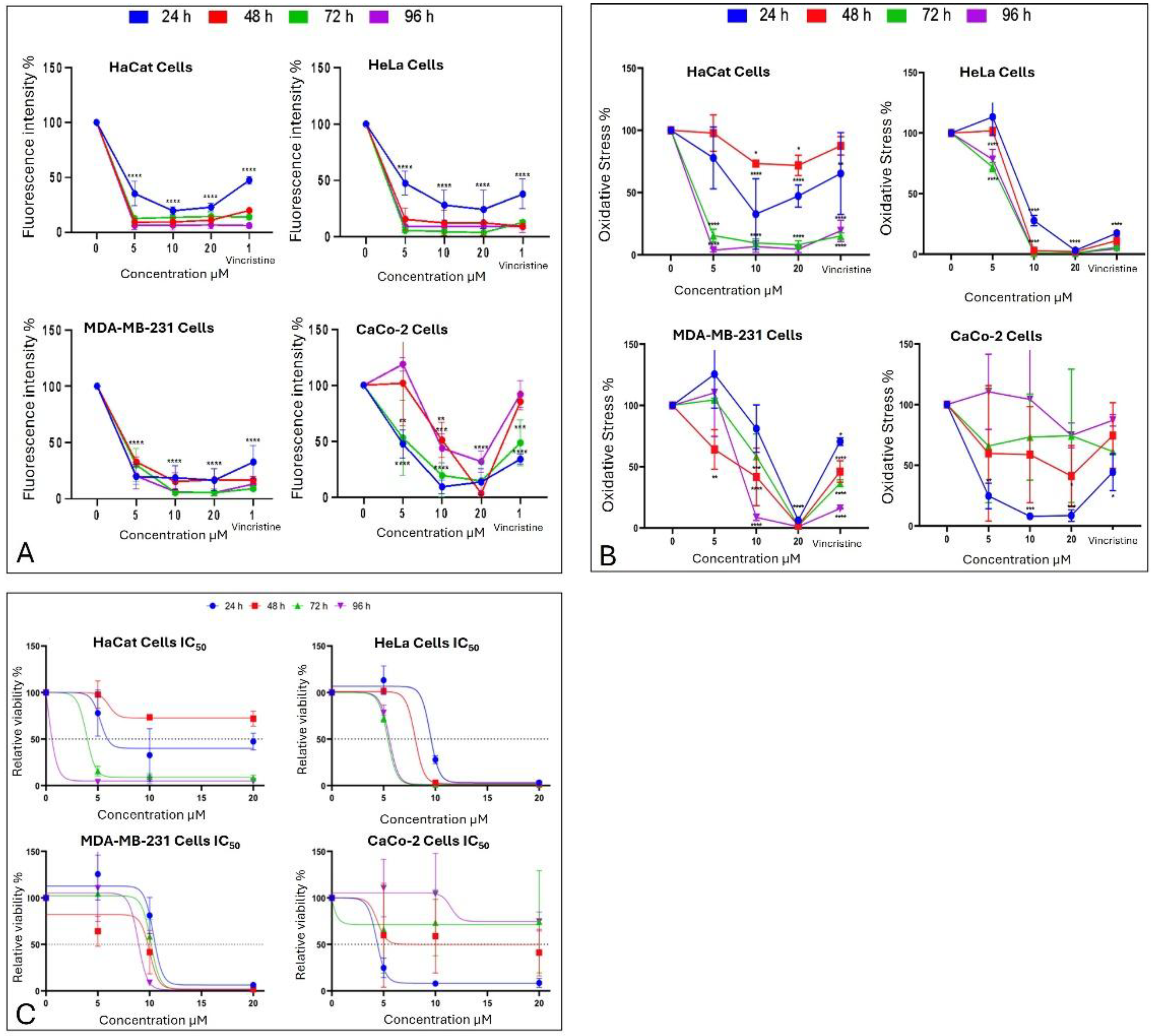

2.3. CBD Induces an Alteration of Metabolism in Cancer Cells

2.4. CBD Decreases Cell Viability in Cancer Cells

2.5. Determination of the Median Inhibitory Dose (LC50) of CBD in Cancer Cell Lines

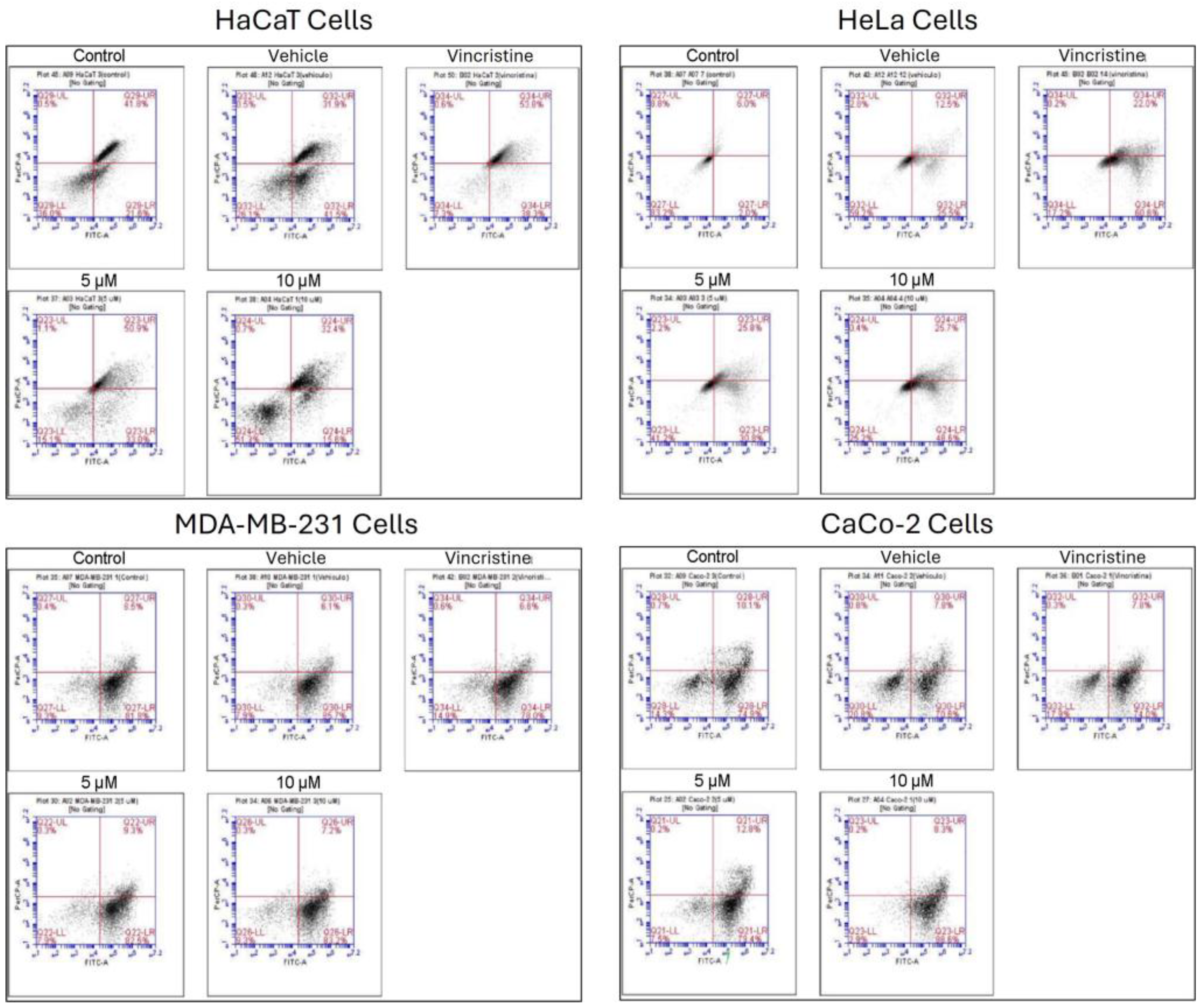

2.6. Type of Cell Death Induced by CBD

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. CBD Source and Chemical Characterization

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. Cell Viability Assay

4.4. Nuclear Fragmentation Assay

4.5. Apoptosis and Necrosis Assay

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Globocan (2020) All cancers. Recuperado de https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/39-All-cancers-fact-sheet-pdf el 12 de abril del 2023.

- National Cancer Institute. (2022). Tipos de tratamiento del cáncer – Recuperado el 4 de diciembre del 2023, de https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/cancer/tratamiento/tipos.

- Atalay, S. , Jarocka-karpowicz, I., & Skrzydlewskas, E. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties of cannabidiol. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baswan, S. M. Baswan, S. M., Klosner, A. E., Glynn, K., Rajgopal, A., Malik, K., Yim, S., & Stern, N. (2020). Therapeutic potential of cannabidiol (CBD) for skin health and disorders. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology 2020, 13, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, A. , Kuzontkoski, P. M., Groopman, J. E., & Prasad, A. Cannabidiol induces programmed cell death in breast cancer cells by coordinating the cross-talk between apoptosis and autophagy. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2011, 10, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, A. S. , Marie, M. A., & Sheweita, S. A. (2018). Novel mechanism of cannabidiol-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines. Breast, 41, 34–41. [CrossRef]

- Di Marzo, V. , & Piscitelli, F. (2015). The Endocannabinoid System and its Modulation by Phytocannabinoids. In Neurotherapeutics (Vol. 12, Issue 4, pp. 692–698). Springer New York LLC. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A. H. Tortolani, D., Ayakannu, T., Konje, J. C., & Maccarrone, M. (2021). (Endo)cannabinoids and gynaecological cancers. Cancers 2021, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramer, R. , Merkord, J., Rohde, H., & Hinz, B. (2010). Cannabidiol inhibits cancer cell invasion via upregulation of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1. Biochemical Pharmacology, 79(7), 955–966. [CrossRef]

- Aviello, G. , Romano, B., Borrelli, F., Capasso, R., Gallo, L., Piscitelli, F., Di Marzo, V., & Izzo, A. A. (2012). Chemopreventive effect of the non-psychotropic phytocannabinoid cannabidiol on experimental colon cancer. Journal of Molecular Medicine, 90(8), 925–934. [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, F. , Pagano, E., Romano, B., Panzera, S., Maiello, F., Coppola, D., De Petrocellis, L., Buono, L., Orlando, P., & Izzo, A. A. (2014). Colon carcinogenesis is inhibited by the TRPM8 antagonist cannabigerol, a Cannabis-derived non-psychotropic cannabinoid. Carcinogenesis, 35(12), 2787–2797. [CrossRef]

- Petrosino, S. , Verde, R., Vaia, M., Allará, M., Iuvone, T., & Di Marzo, V. (2018). Anti-inflammatory properties of cannabidiol, a nonpsychotropic cannabinoid, in experimental allergic contact dermatitis. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 365(3), 652–663. [CrossRef]

- Sangiovanni, E. Fumagalli, M., Pacchetti, B., Piazza, S., Magnavacca, A., Khalilpour, S., Melzi, G., Martinelli, G., & Dell’Agli, M. (2019). Cannabis sativa L. extract and cannabidiol inhibit in vitro mediators of skin inflammation and wound injury. Phytotherapy Research 2019, 33(8), 2083–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , Hao, D., Wei, D., Xiao, Y., Liu, L., Li, X., Wang, L., Gan, Y., Yan, W., Ke, B., & Jiang, X. (2022). Photoprotective Effects of Cannabidiol against Ultraviolet-B-Induced DNA Damage and Autophagy in Human Keratinocyte Cells and Mouse Skin Tissue. Molecules, 27(19). [CrossRef]

- Lukhele, S. T. , & Motadi, L. R. (2016). Cannabidiol rather than Cannabis sativa extracts inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in cervical cancer cells. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 16(1). [CrossRef]

- Collins, J. A. , Schandl, C. A., Young, K. K., Vesely, J., & Willingham, M. C. (1997). Major DNA Fragmentation Is a Late Event in Apoptosis. In The Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry (Vol. 45, Issue 7).

- Crowley, L. , Marfell, B., & Waterhouse, N. (2016). Analyzing Cell Death by Nuclear Staining with Hoechst 33342. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- D’Aloia, A. , Ceriani, M., Tisi, R., Stucchi, S., Sacco, E., & Costa, B. (2022). Cannabidiol Antiproliferative Effect in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells Is Modulated by Its Physical State and by IGF-1. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(13). [CrossRef]

- Williams Nkune, N. , Kruger, C. A., & Abrahamse, H. (2022). Oncotarget 156 www.oncotarget.com Synthesis of a novel nanobioconjugate for targeted photodynamic therapy of colon cancer enhanced with cannabidiol. In Oncotarget (Vol. 13). www.oncotarget.

- Almeida, C. F. , Teixeira, N., Correia-Da-silva, G., & Amaral, C. (2022). Cannabinoids in breast cancer: Differential susceptibility according to subtype. In Molecules (Vol. 27, Issue 1). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Olivas-Aguirre, M. , Torres-López, L., Valle-Reyes, J. S., Hernández-Cruz, A., Pottosin, I., & Dobrovinskaya, O. (2019). Cannabidiol directly targets mitochondria and disturbs calcium homeostasis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cell Death and Disease, 10(10). [CrossRef]

- Jane, L. Armstrong, David S. Hill, Christopher S. McKee, Sonia Hernandez-Tiedra, Mar Lorente, Israel Lopez-Valero, Maria Eleni Anagnostou, Fiyinfoluwa Babatunde, Marco Corazzari, Christopher P.F. Redfern, Guillermo Velasco, Penny E. Lovat,. Exploiting cannabinoid-induced cytotoxic autophagy to drive melanoma cell death. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S. , Li, J., Yao, Z., & Liu, J. (2021). Cannabidiol induces autophagy to protects neural cells from mitochondrial dysfunction by upregulating SIRT1 to inhibits NF-κB and NOTCH pathways. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 15, 654340.

- Solinas, M. , Massi P., Cantelmo AR., Cattaneo MG., Cammarota R., Bartolini D., Cinquina V., Valenti M., Vicentini LM, Noonan DM., Albini A., Parolaro D. (2012). Cannabidiol inhibits angiogenesis by multiple mechanisms. British journal of pharmacology, 167(6), 1218-1231. [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Meléndez GA, Villa-Cedillo SA, Pérez-Hernández RA, Castillo-Velázquez U, Salas-Treviño D, Saucedo-Cárdenas O, Montes-de-Oca-Luna R, Gómez-Tristán CA, Garza-Arredondo AJ, Zamora-Ávila DE, de Jesús Loera-Arias M, Soto-Domínguez A. (2021). Cytotoxic Effect In Vitro of Acalypha monostachya Extracts over Human Tumor Cell Lines. Plants (Basel). 10(11):2326. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Cell line | Time of exposure | LC50 | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| HaCaT | 24 h | 5.233 | 0.417 |

| 72 h | 3.903 | 0.157 | |

| 96 h | 0.183 | 1.525 | |

| HUVEC | 24 h | 2.1647 | 0.419 |

| 48 h | 2.6887 | 0.265 | |

| 72 h | 1.3471 | 0.256 | |

| 96 h | 0.268 | 0.058 | |

| HeLa | 24 h | 9.495 | 0.157 |

| 48 h | 8.034 | 0.555 | |

| 72 h | 5.400 | 0.029 | |

| 96 h | 5.547 | 0.074 | |

| MDA-MB-231 | 24 h | 10.373 | 0.248 |

| 48 h | 9.993 | 0.292 | |

| 72 h | 10.110 | 0.105 | |

| 96 h | 8.893 | 0.848 | |

| CaCo-2 | 24 h | 4.340 | 0.122 |

| 48 h | 4.389 | 1.299 |

| Flow Cytometry Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line | Concentration | Viability | Early Apoptosis | Late Apoptosis | Necrosis |

| HaCaT | Control | 38.87% | 18.16% | 42.28% | 0.68% |

| Vehicle | 26.42% | 35.38% | 37.68% | 0.51% | |

| 5 µM | 17.91% | 29.54% | 51.05% | 1.49% | |

| 10 µM | 48.07% | 22.30% | 28.79% | 0.85% | |

| Positive Control | 7.53% | 41.56% | 50.35% | 0.56% | |

| HeLa | Control | 80.99% | 4.20% | 7.11% | 7.70% |

| Vehicle | 60.66% | 22.86% | 13.30% | 3.18% | |

| 5 µM | 45.23% | 28.01% | 24.52% | 2.24% | |

| 10 µM | 24.37% | 52.87% | 22.38% | 0.38% | |

| Positive Control | 22.10% | 56.47% | 20.90% | 0.53% | |

| MDA-MB-231 | Control | 9.40% | 79.70% | 10.48% | 0.41% |

| Vehicle | 8.87% | 82.71% | 7.98% | 0.44% | |

| 5 µM | 7.41% | 82.68% | 9.53% | 0.38% | |

| 10 µM | 8.24% | 81.78% | 9.68% | 0.31% | |

| Positive Control | 12.56% | 80.74% | 6.23% | 0.48% | |

| CaCo-2 | Control | 14.62% | 75.26% | 9.67% | 0.45% |

| Vehicle | 20.42% | 70.36% | 8.48% | 0.75% | |

| 5 µM | 7.60% | 79.19% | 12.90% | 0.32% | |

| 10 µM | 3.05% | 87.36% | 9.26% | 0.33% | |

| Positve Control | 15.26% | 75.63% | 8.81% | 0.30% | |

| Abbreviation | Dry Wt. % | Dry Wt. mg/g |

|---|---|---|

| THCA | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| Δ-9-THC | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| Δ-8-THC | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| THCV | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| CBDA | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| CBD | 99 % (A) | 990.0 mg/g |

| CBGA | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| CBG | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| CBDVA | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| CBDV | 1.00% | 10.0 mg/g |

| CBN | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| CBL | < LOQ | < LOQ |

| CBC | < LOQ | < LOQ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).