1. Introduction

Brucellosis is a globally distributed zoonotic disease caused by Gram-negative bacteria of the

Brucella genus. The disease primarily affects domestic and wild animals, which act as reservoirs, facilitating transmission to humans [

1]. Among the species most pathogenic to humans are

B. melitensis,

B. suis, and

B. abortus. In animals, brucellosis is closely linked to reproductive disorders, including abortion, premature birth, orchitis, epididymitis, and infertility. In pregnant women, numerous studies have reported an increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes such as preterm delivery, spontaneous abortion, fetal death, and low birthweight [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Notably, infection can be transmitted to the fetus, primarily through transplacental spread [

8,

9]. Given the association between

Brucella infection and reproductive complications, understanding its impact on key processes at the maternal-fetal interface is crucial.

Establishing a successful pregnancy relies on maternal endometrial receptivity during the implantation window. A pivotal event in this process is decidualization, which involves structural and functional changes in endometrial stromal cells, including cell enlargement, spiral artery remodeling, and immune cell infiltration by macrophages and uterine natural killer cells [

10]. Endometrial stromal cells, the predominant cell type in the endometrium, undergo cyclic differentiation during the luteal phase in response to rising levels of estrogen and progesterone [

11]. This differentiation transforms stromal cells from a fibroblast-like morphology into epithelioid-like decidual cells, a process that in humans occurs even in the absence of implantation and reaches full maturity at the onset of gestation. Decidualization not only supports implantation by promoting the secretion of key factors such as prolactin but also facilitates immune tolerance by attracting predominantly anti-inflammatory leukocytes, preventing excessive recruitment of cytotoxic T cells [

12]. Additionally, decidual cells secrete chemokines that promote trophoblast invasion and angiogenesis, essential for early pregnancy development[

13].

At the maternal-fetal interface, the decidua and the placenta form a highly specialized structure critical for pregnancy maintenance. The placenta contains three types of trophoblasts: cytotrophoblasts, which are mononuclear proliferative cells; syncytiotrophoblasts, which form a multinucleated layer covering the chorionic villi; and extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs). Among these, EVTs invade the decidua to anchor the placenta and remodel maternal spiral arteries, ensuring adequate blood flow to the fetus. Together, the decidua and trophoblasts contribute to the production of essential hormones and nutrients required for fetal growth. Proper decidualization and trophoblast invasion are, therefore, fundamental processes that, if disrupted, may lead to pregnancy complications.

Although the uterus provides a unique immune environment that supports the development of the semi-allogeneic fetus, it remains susceptible to infections. Pathogens may access the endometrium via ascending routes from the vagina or through hematogenous circulation [

14], potentially altering its function and triggering inflammatory responses that can compromise pregnancy [

15]. Infections have been implicated in up to 15% of early pregnancy losses [

16,

17]. Decidual and non-decidual stromal cells express various pathogen recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and Nod-like receptors (NLRs), which detect microbial components and initiate immune responses through the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and metalloproteinases [

18,

19]. This innate immune defense is essential for limiting infection but can also lead to tissue damage and impaired decidual function when dysregulated.

Altered decidualization, measured by reduced expression of decidual markers such as prolactin, has been linked to pregnancy complications, including miscarriage, preeclampsia, and intrauterine growth restriction[

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, infections by bacteria such as

Chlamydia trachomatis have been shown to impair decidualization and decidual function in uterine stromal cells [

23]. Despite these findings, little is known about how bacterial infections, such as those caused by

Brucella, affect the interaction between endometrial stromal cells and EVTs at the maternal-fetal interface.

We previously demonstrated that

B. abortus infects fully decidualized and non-decidualized endometrial stromal cells, inducing a proinflammatory response [

24]. Moreover, a recent study in mice showed that lipopolysaccharide from

B. suis S2 disrupts decidualization and reduces implantation rates[

25]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the effects of infection with highly virulent

Brucella species on stromal cell decidualization, as well as its subsequent effects on trophoblast migration, adhesion, invasion and immune responses in the context of trophoblast-decidua interactions.

3. Discussion

Trophoblast invasion of the maternal endometrial stroma and the remodeling of spiral arteries mediated by these cells are fundamental processes in early placental development. Disruptions in any of these steps can compromise pregnancy progression and lead to severe gestational pathologies. Decidual stromal cells play a pivotal role in modulating trophoblast function during implantation. These maternal cells create a finely tuned microenvironment that supports trophoblast migration, invasion, and differentiation by secreting cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and extracellular matrix components. For example, factors secreted by decidualized endometrial stromal cells enhance trophoblast invasion by upregulating matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and integrins [

35]. Moreover, decidual stromal cells actively shape the local immune landscape, contributing to immune tolerance and tissue remodeling, both essential for successful placentation.

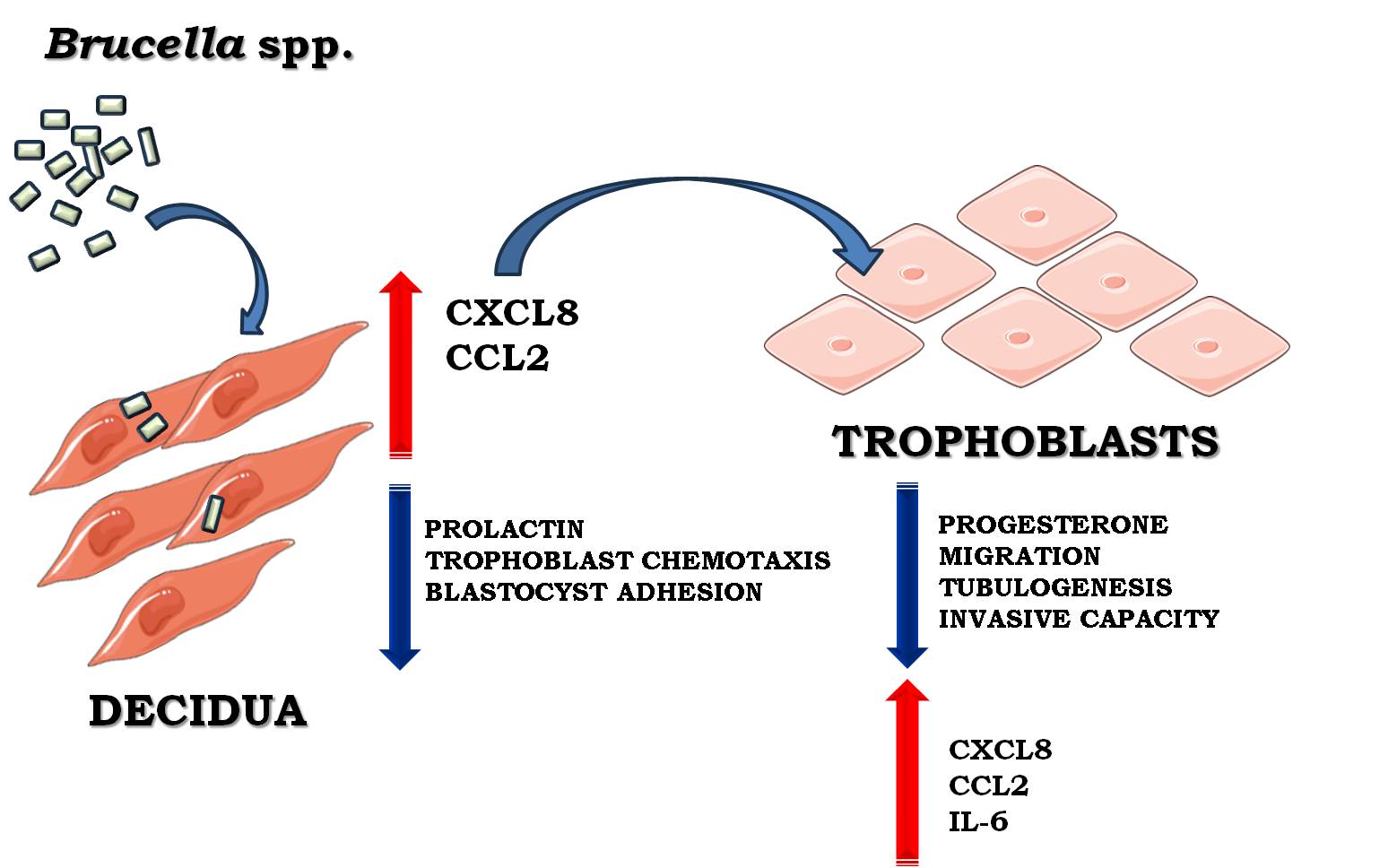

Using the first-trimester placental trophoblast cell line Swan-71 and the telomerase-immortalized human endometrial stromal cell line T-HESC as experimental models, we demonstrated that infection with virulent Brucella species impairs endometrial decidualization and induces an exacerbated inflammatory microenvironment, ultimately disrupting trophoblast functionality.

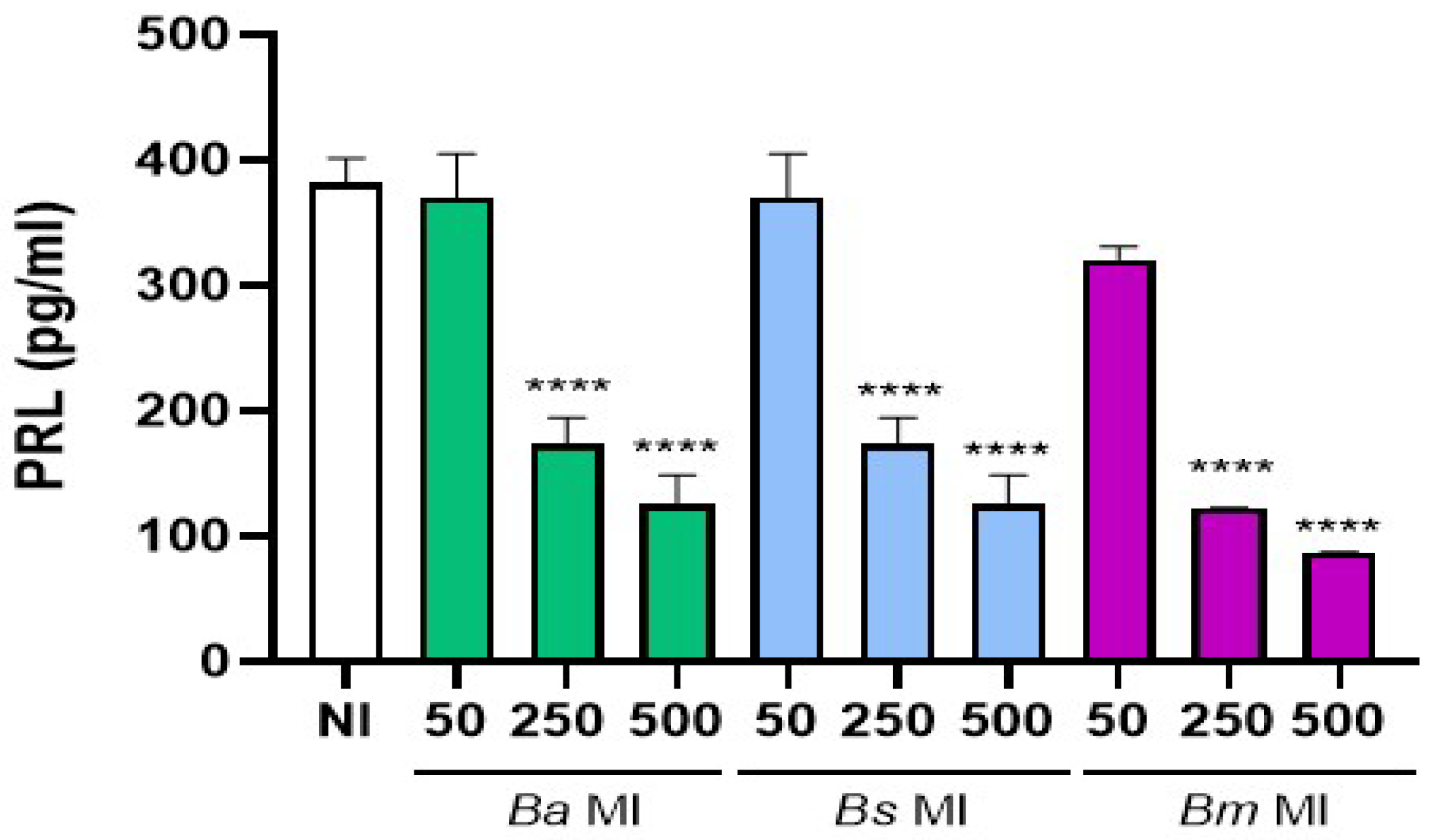

We had previously reported that

B. abortus infection of already decidualized stromal cells did not alter their decidual phenotype [

24]. However, the present study shows that prior

Brucella infection of stromal endometrial cells attenuates the subsequent decidualization process, reflected in reduced PRL levels, in a MI-dependent manner across all virulent

Brucella species tested.

This observation is particularly relevant because animal models show that the uterus can serve as a reservoir for

Brucella persistence and replication even outside pregnancy, and chronic

Brucella infection has been linked to infertility [

26]. Thus, previously infected stromal cells may undergo incomplete or defective decidualization, impairing crosstalk with trophoblasts and contributing to gestational complications associated with brucellosis. Interestingly, Lei et al. [

25] recently demonstrated that purified LPS from

B. suis S2 also disrupts decidualization, leading to implantation failure.

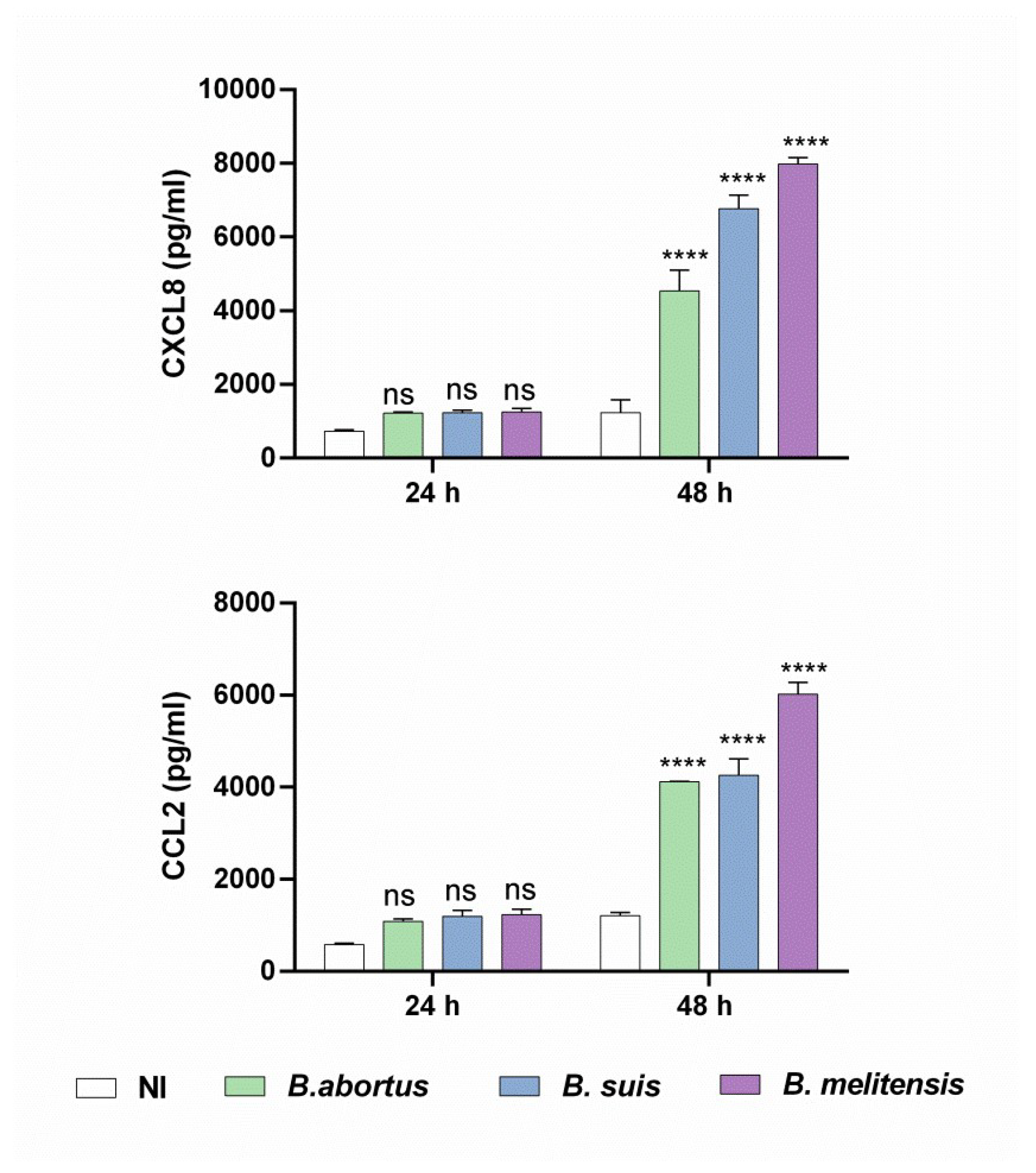

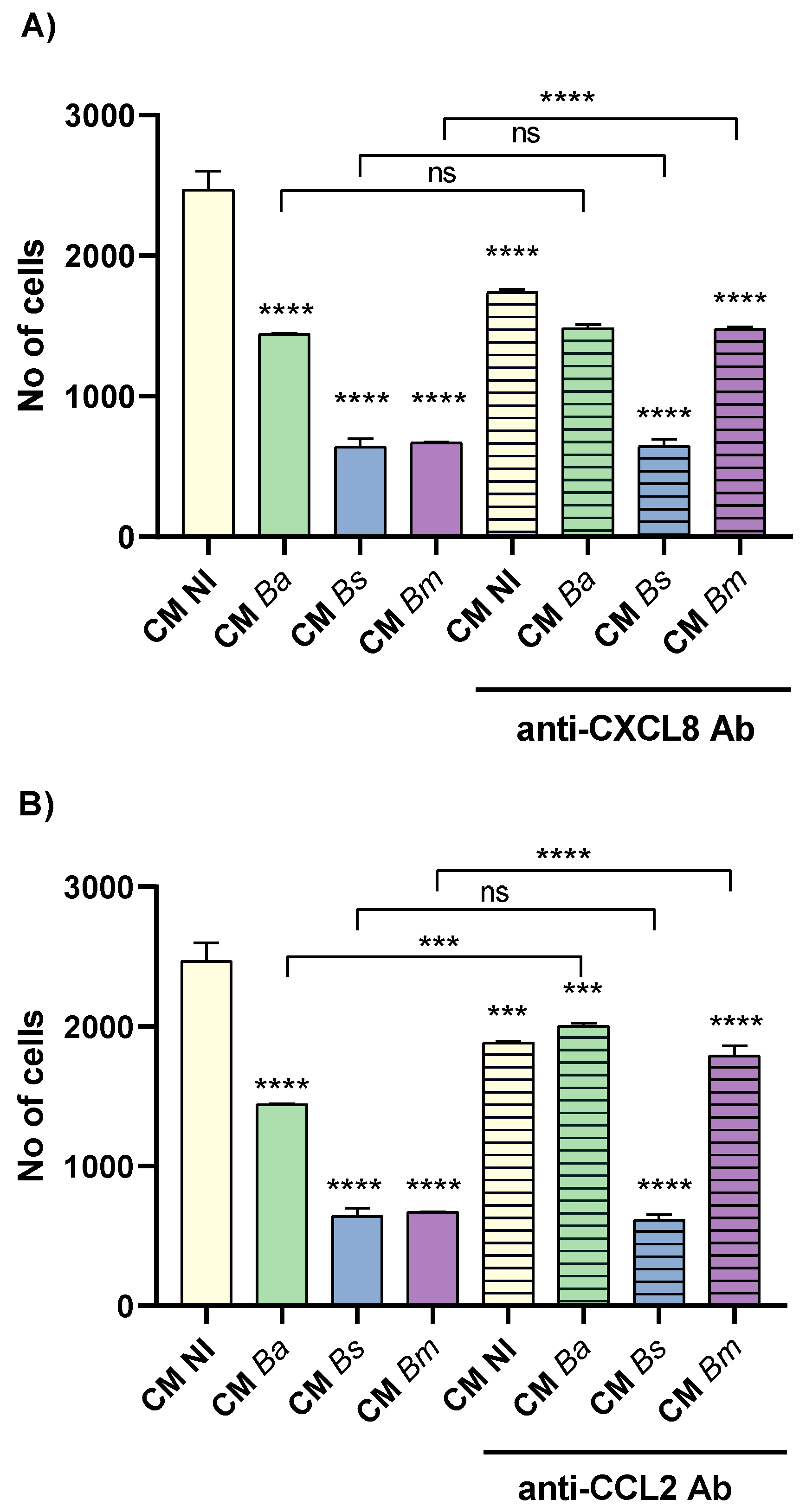

Importantly, we found that the secretome of infected and decidualized T-HESCs showed increased levels of CXCL8 and CCL2 but not IL-6. In turn, CM from these cells stimulated Swan-71 trophoblasts to secrete IL-6, CXCL8, and CCL2. Notably, these infection-driven changes in the decidual microenvironment correlated with reduced acquisition of invasive phenotypes by trophoblasts, suggesting that an altered cytokine milieu negatively affects trophoblast behavior.

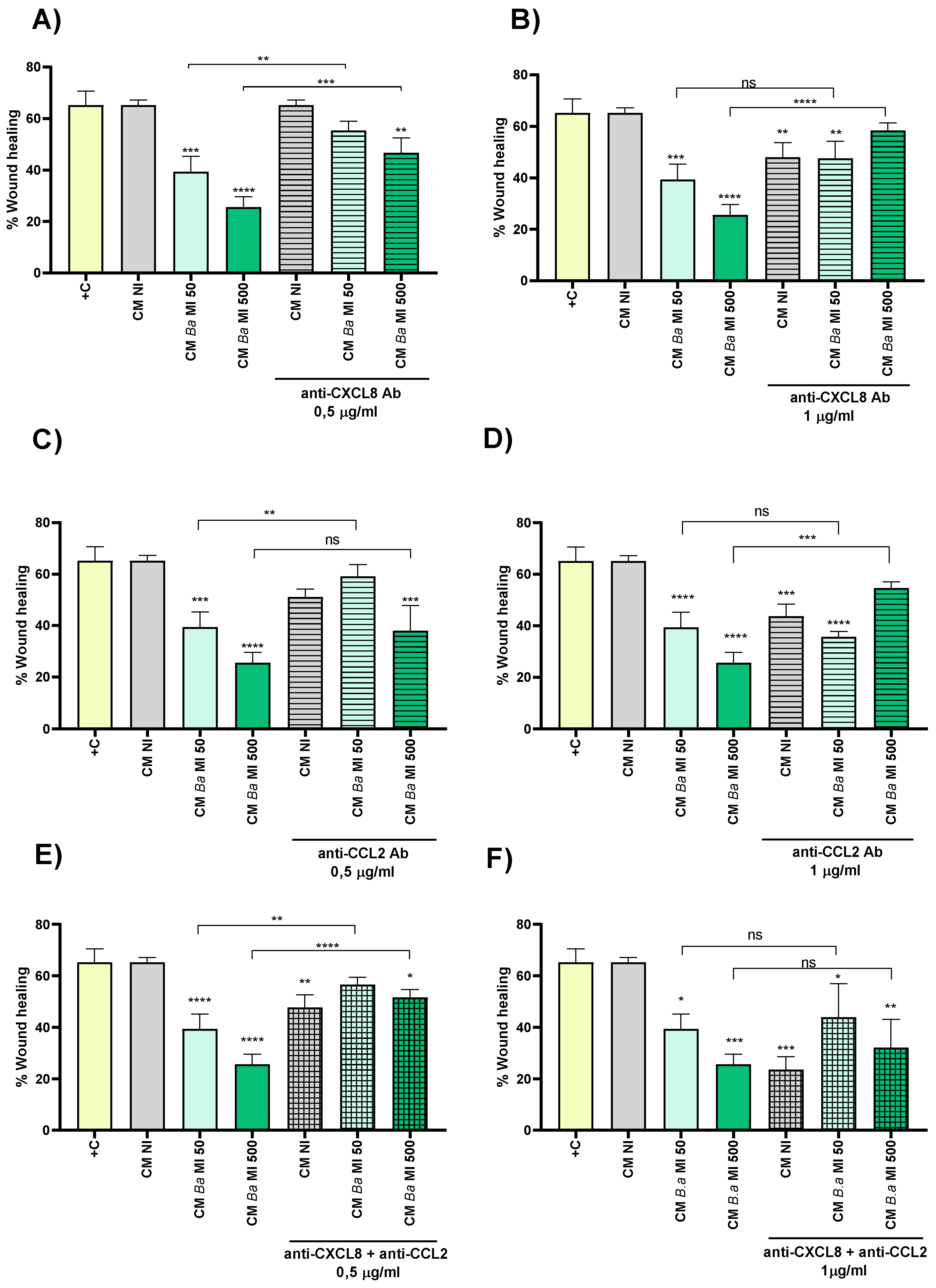

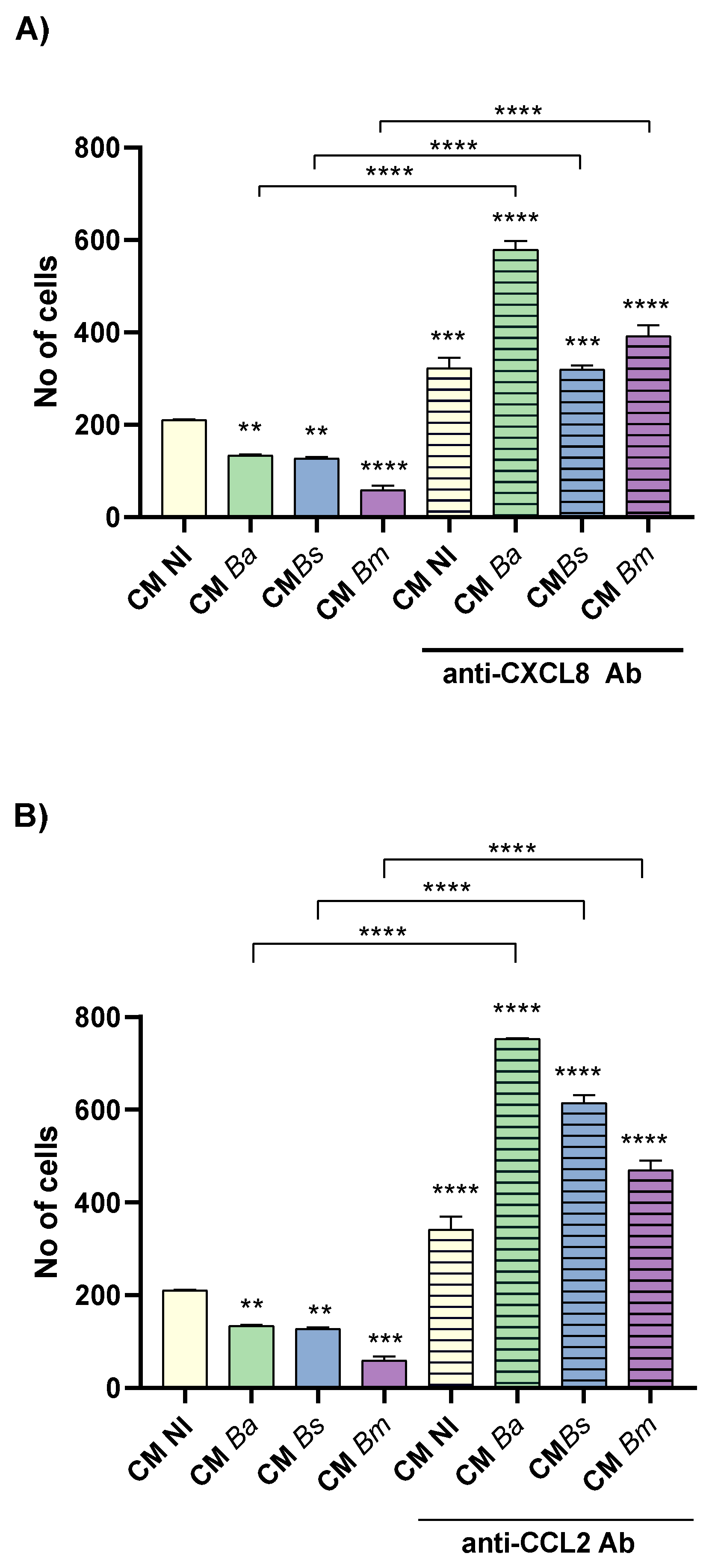

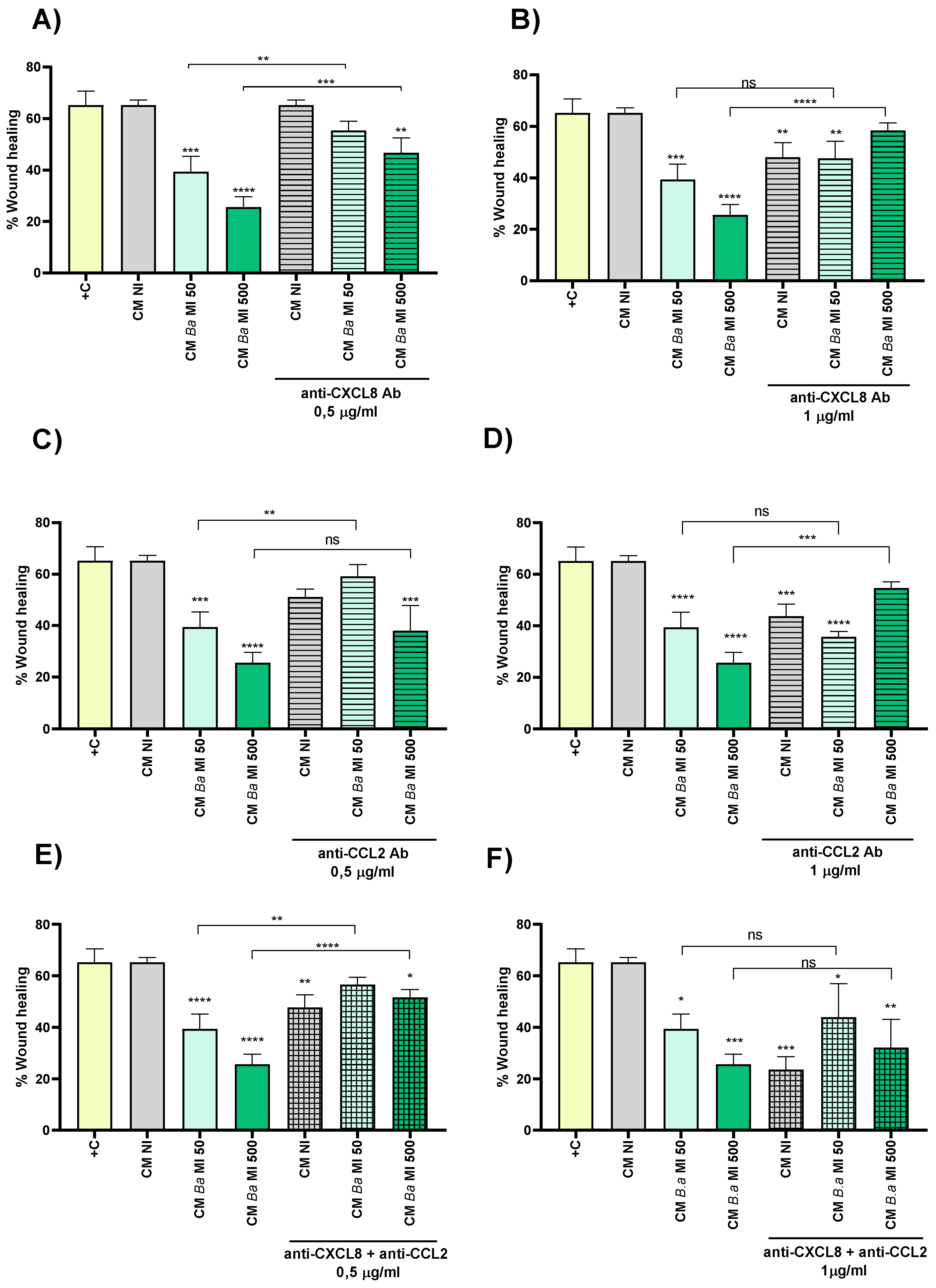

A key step in implantation is thus the coordinated migration and invasion of trophoblast cells through the maternal tissue. Among the various maternal-derived factors modulating this process, CXCL8 and CCL2 play a critical role. Decidual stromal cells and uterine natural killer cells are prominent sources of CXCL8 within the maternal-fetal interface, and its receptors are highly expressed on extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs) [

36]. Proper CXCL8 signaling is considered essential for a successful pregnancy, as diminished levels of CXCL8 or its receptors have been linked to recurrent pregnancy loss [

37]. Our group [

38] and others [

39,

40] have shown that exogenous CXCL8 stimulates MMP secretion, thereby promoting the migration and invasion of HTR-8 trophoblast cells. However, under pathological conditions, excessive CXCL8 levels may exert detrimental effects, shifting from a stimulatory to an inhibitory role on trophoblast behavior [

38,

39]. Consistent with these previous observations, we demonstrate here that neutralization of CXCL8 partially reverses the ability of CM from

Brucella-infected and decidualized T-HESCs to inhibit trophoblast migration and invasion. Interestingly, the highest concentration of neutralizing anti-CXCL8 antibody also reduced migration induced by CM from non-infected decidualized T-HESCs, reinforcing the idea that a fine-tuned balance of CXCL8 is critical for optimal trophoblast function.

Moreover, our study shows that trophoblast migration was also restored when CCL2 in the CM from infected and decidualized T-HESCs was neutralized. CCL2 is secreted by decidual tissue during early pregnancy, where its production is induced by cytokines, estrogens, progesterone, and hCG, and is regulated in an autocrine manner via the ERK/MAPK pathway through its receptor CCR2 [

41,

42,

43]. Variations in CCL2 levels can influence both normal pregnancy progression and pathological outcomes [

43,

44]. Although CCR2 mRNA has been detected in first-trimester bovine trophoblasts [

45], the expression of CCR2 in human trophoblasts remains uncertain. Nevertheless, CCL2 can promote cell migration through the CCR4 receptor [

46]. CCR4 expression has been specifically detected in invasive EVTs where it mediates migration [

47]. Thus, the CCL2/CCR4 axis could partially mediate the migratory response seen upon treatment with CM from

Brucella-infected decidual cells.

Beyond direct effects, CCL2 exerts indirect trophoblast regulation by recruiting macrophages expressing G-CSF, which promote EVT growth and invasion [

48], guiding Th17 cells that produce IL-17 [

45], and suppressing COX-2-associated oxidative stress, creating a favorable implantation environment. Additionally, since Swan-71 cells stimulated with CM from infected decidual cells also secreted CCL2 and CXCL8, we cannot exclude autocrine effects of these chemokines on trophoblast migration.

Although IL-6 has been shown to enhance trophoblast migration and invasion [

49], we observed no significant increase in IL-6 levels following decidual infection. However, excessive IL-6 produced by Swan-71 cells in response to CM from infected dedicual cells could still contribute to the inhibition of migratory and invasive capacity.

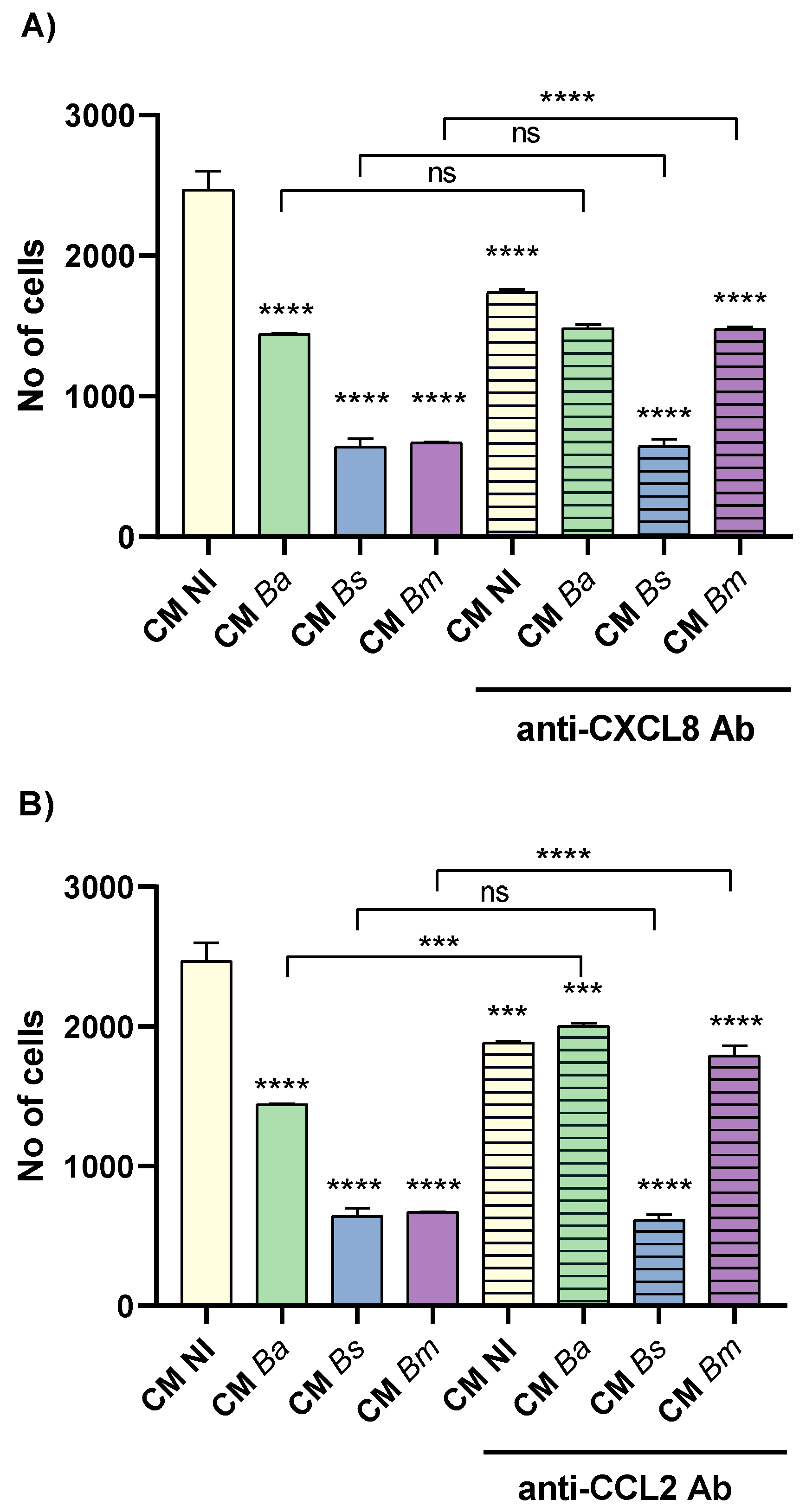

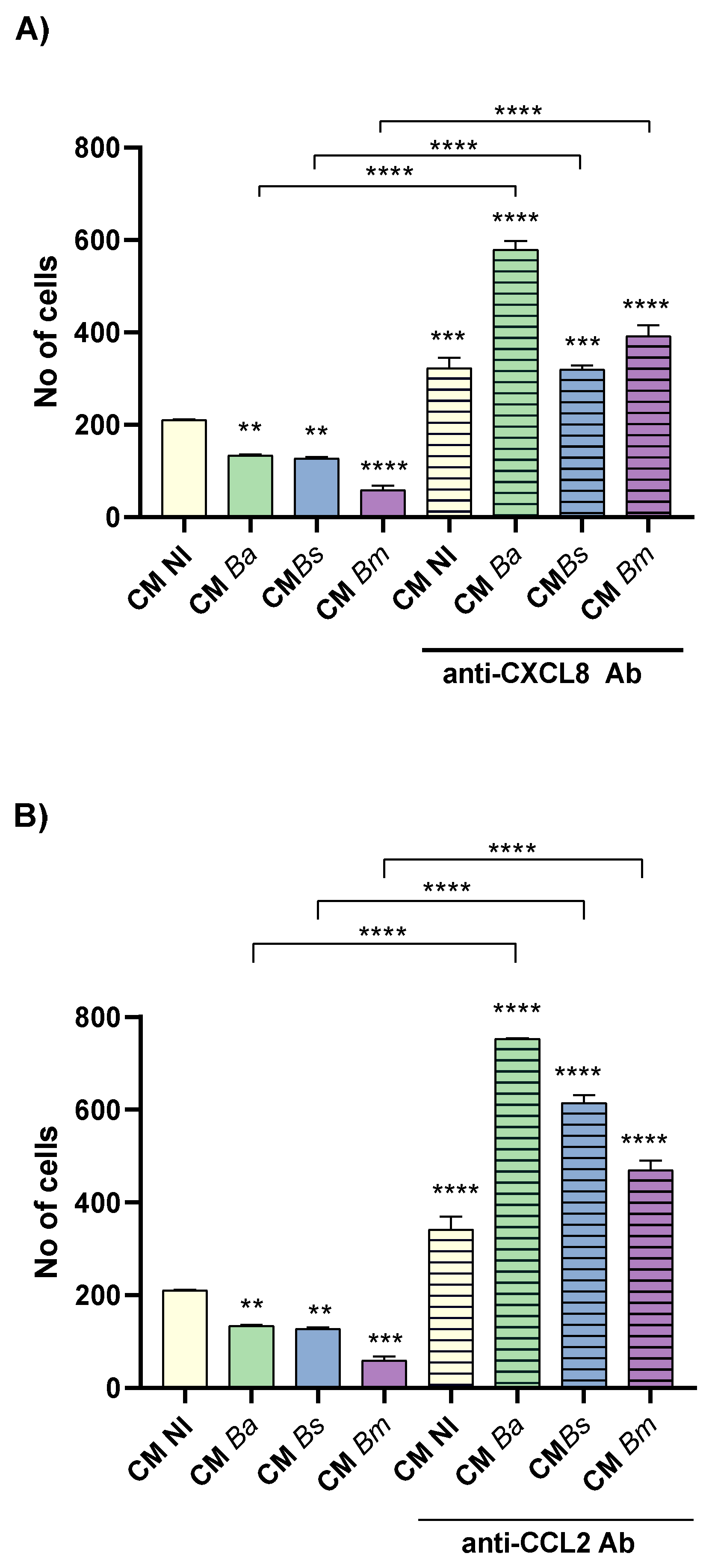

Our data further show that previous Brucella infection of stromal endometrial cells not only modified the cytokine profile but also affected the chemotactic response of trophoblast cells, reducing their directed migration toward the CM. These findings highlight that beyond impairing intrinsic trophoblast invasive capacity, infection-driven alterations in the decidual secretome compromise its chemotactic and supportive functions towards trophoblasts, further disrupting the finely orchestrated maternal-trophoblast interactions essential for successful implantation and placentation.

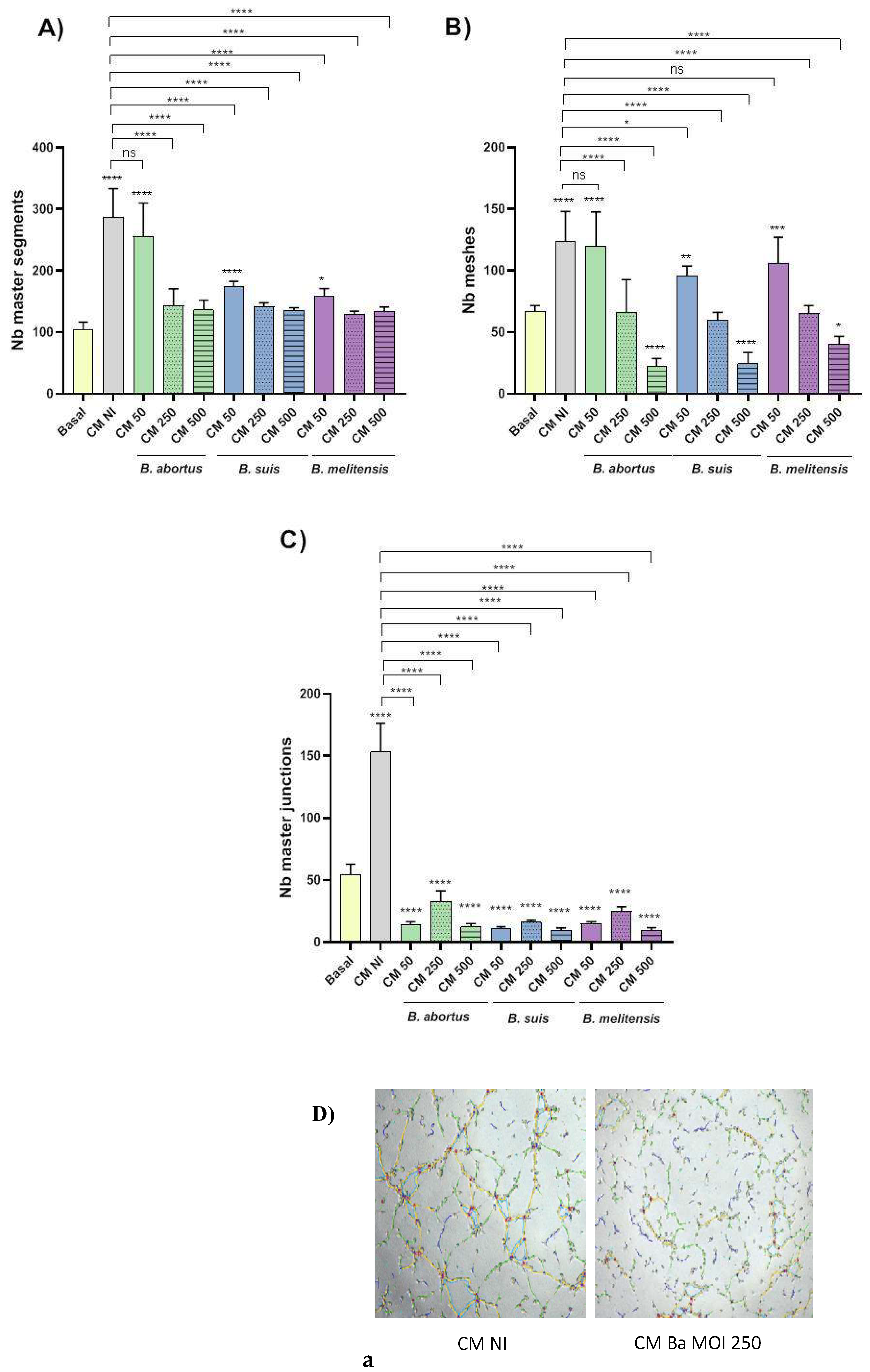

Following the initial stages of implantation, extravillous cytotrophoblasts progressively invade the uterine wall and maternal spiral arteries, undergoing a specialized epithelial-to-endothelial transition known as vascular mimicry or pseudo-vasculogenesis, which is essential for proper placental vascular remodeling [

34]. The remodeling process can be seen as a form of tubulogenesis, where new tubular structures (the remodeled spiral arteries) are formed. Our results demonstrate that CM from

Brucella-infected decidualized T-HESC significantly impairs the tubulogenic capacity of Swan-71 trophoblast cells, whereas CM from non-infected THESC promotes tubule formation. This inhibitory effect was MI-dependent across all

Brucella species tested. Therefore,

Brucella infection may also hamper a proper vascular remodeling of the placenta, leading to pregnancy complications.

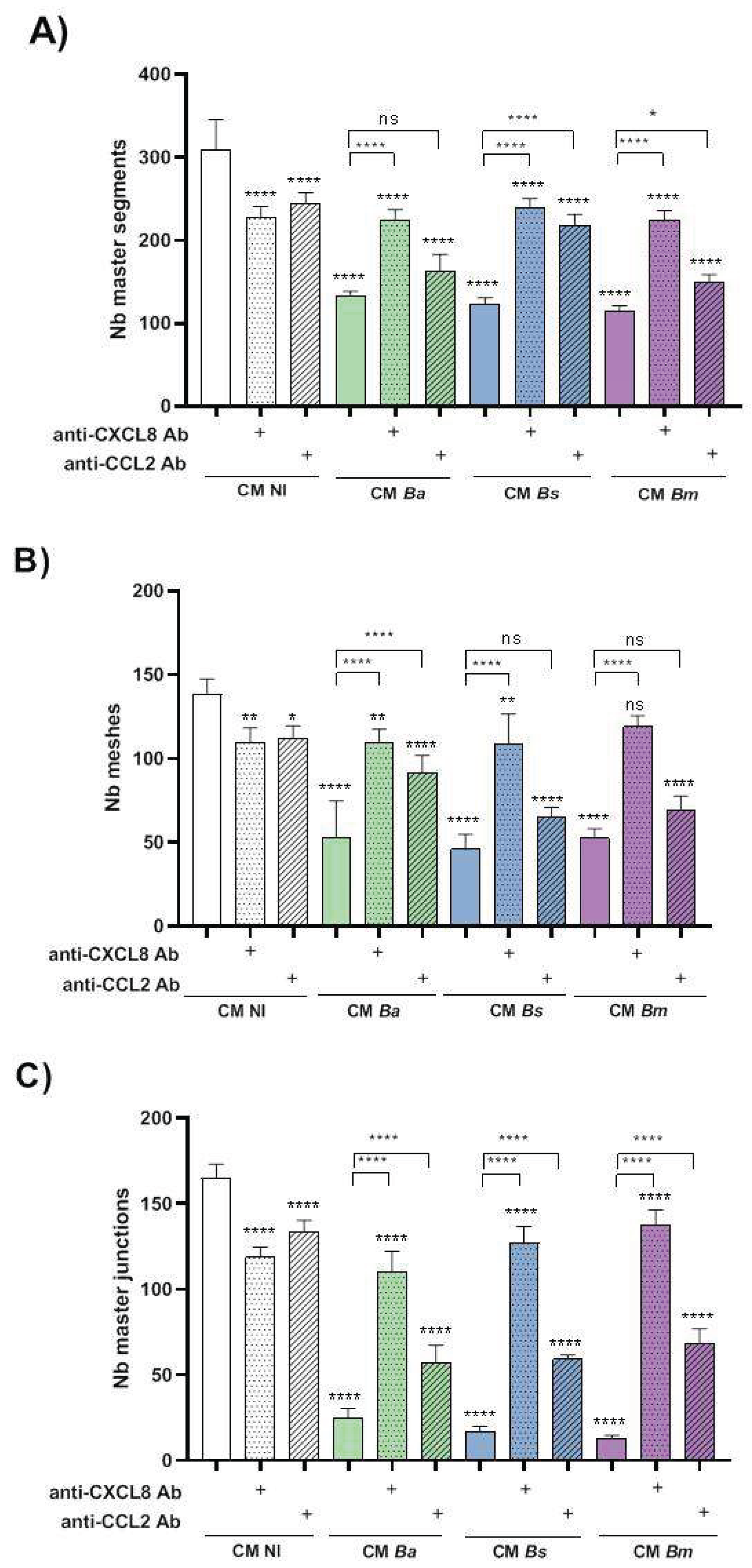

Although numerous studies have shown that CCL2 promotes angiogenesis in endothelial cells [

50], a recent report demonstrated that thrombin can inhibit tube formation by HTR-8 trophoblast cells through the induction of CCL2 production [

51]. Consistent with these findings, our study shows that CCL2 present in CM from infected decidualized T-HESC negatively and partially regulates the tube-forming capacity of Swan-71 cells. While CCL2 is essential for maintaining a successful pregnancy, elevated CCL2 levels have been associated with pathological conditions such as preeclampsia [

43]. Therefore, we speculate that the negative impact of CM from the infected decidua on Swan-71 tubulogenesis and spiral artery remodeling may critically depend on the local concentration of CCL2.

Another key pro-angiogenic factor involved in trophoblast function is CXCL8. Our results reveal that CXCL8 present in the CM of infected decidualized T-HESC plays a central role in regulating tubulogenesis, as neutralization of CXCL8 in this CM partially restores tubule formation to levels comparable to those observed with CM from non-infected controls. These findings suggest that, although physiological levels of CXCL8 promote trophoblast migration, invasion, and tubulogenesis, consistent with its well-established pro-angiogenic effects in both endothelial and trophoblast cells [

52,

53], excessive or deregulated CXCL8 under pathological conditions may disrupt these processes, contributing to defective spiral artery remodeling and compromised placental development.

Overall, our study highlights the dual and context-dependent roles of CXCL8 and CCL2 signaling in trophoblast biology, underscoring the importance of maintaining a finely tuned balance of pro-angiogenic factors at the maternal-fetal interface to ensure successful placentation.

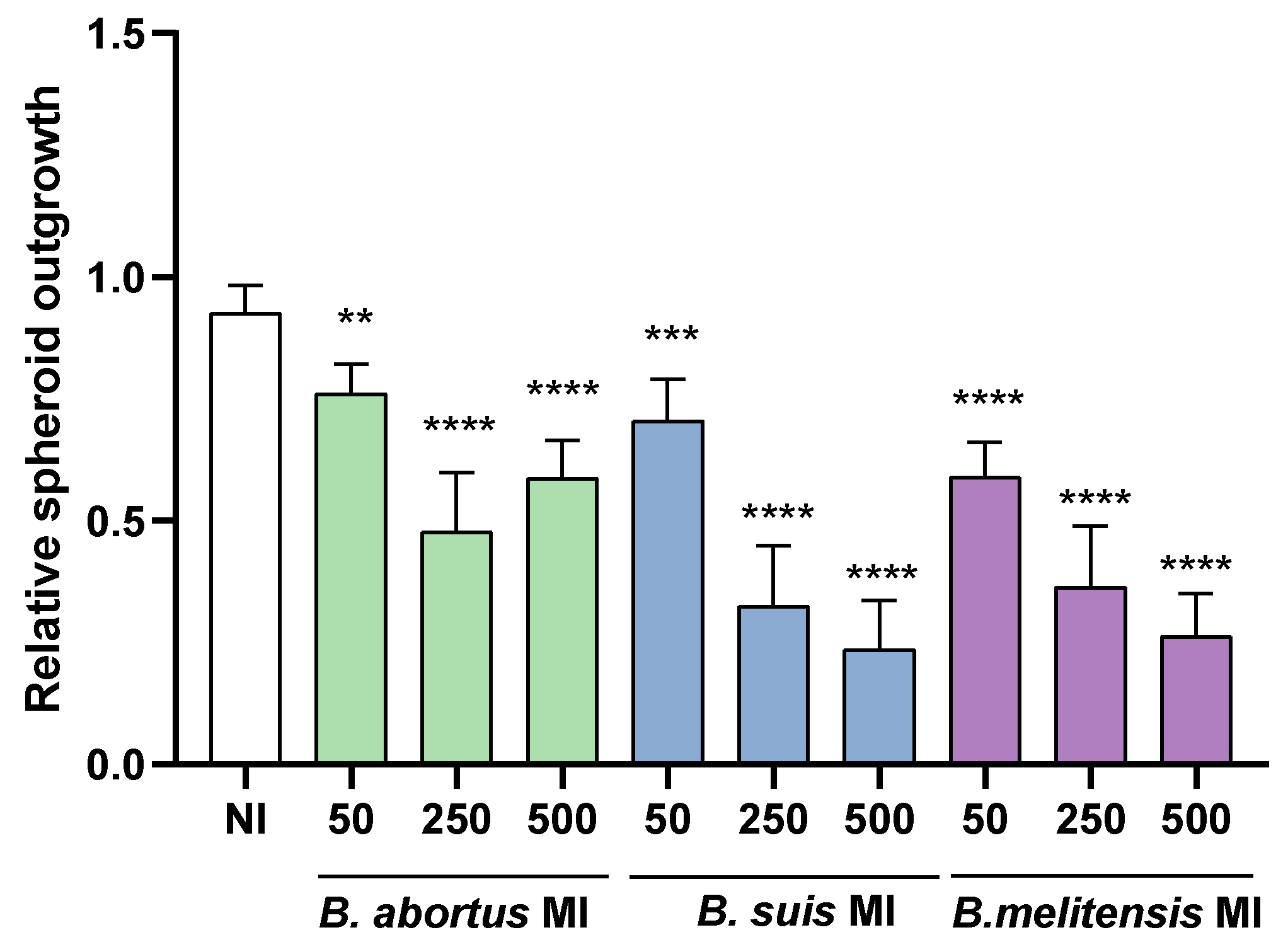

Previous studies have established that the decidua plays a pivotal role in supporting implantation by facilitating trophoblast outgrowth. Decidualized human endometrial stromal cells are notably more effective in this role compared to their non-decidualized counterparts, largely due to their capacity to secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), migrate, and encase the blastocyst, thereby regulating the extent of its invasion [

33,

54]. To investigate how

Brucella infection affects endometrial receptivity, we developed an in vitro implantation model by laying blastocyst-like spheroids derived from Swan-71 trophoblasts on either

Brucella-infected or uninfected decidualized stromal cells. Our results revealed that

Brucella infection significantly impaired trophoblast spreading over the stromal monolayer, with

B. melitensis exerting the most pronounced inhibitory effect. These results suggest that

Brucella infection of the decidua may also lead to implantation failures.

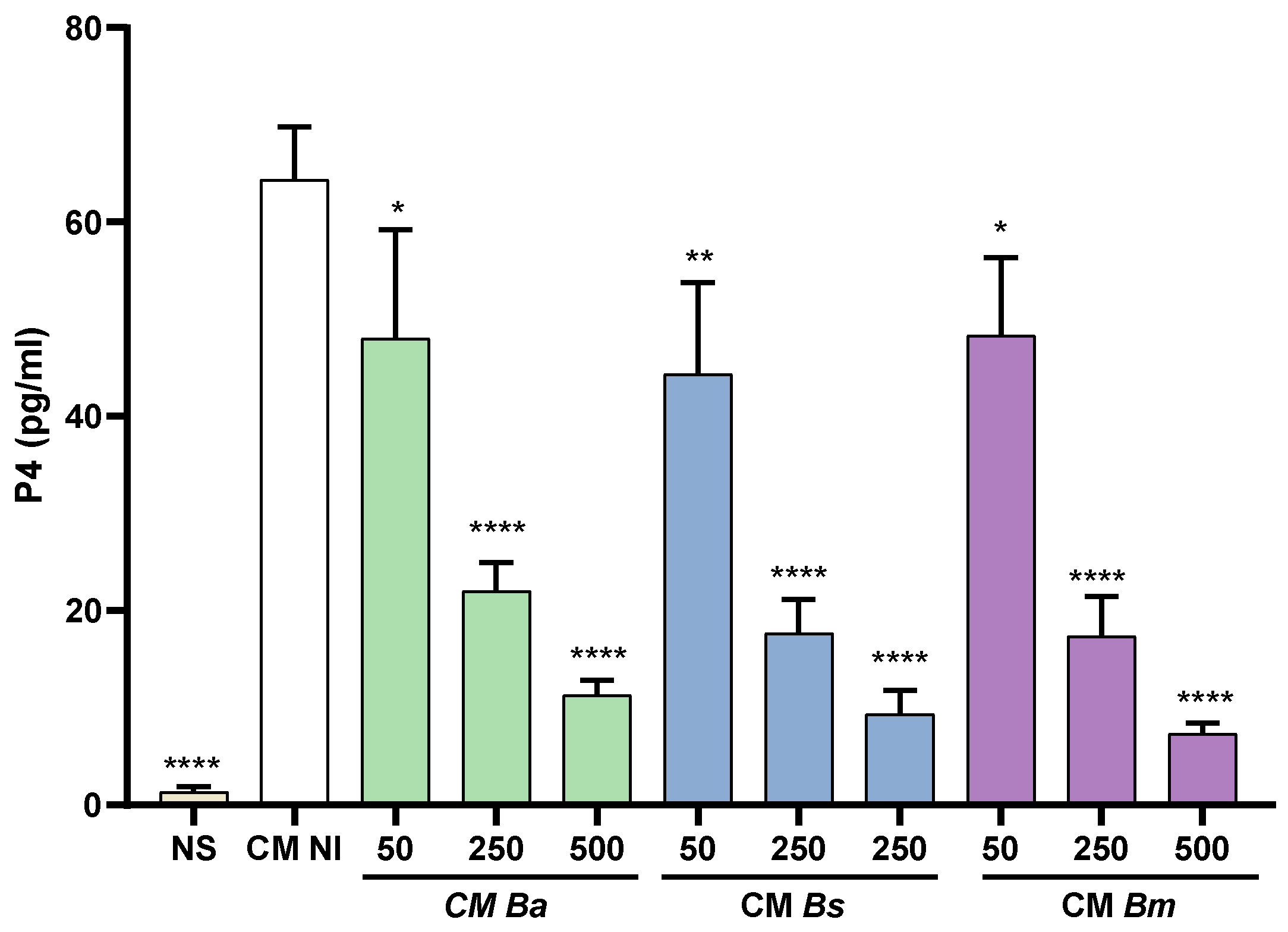

Progesterone has several key roles in pregnancy maintenance, including modulation of maternal immune responses, reduction of uterine contractility, improvement of utero-placental circulation, promotion of extravillous trophoblasts invasion to the decidua, and stimulation of proliferation and differentiation of endometrial stromal cells [

11,

29]. After placental development, progesterone is produced by trophoblasts under the control of several factors including estrogen, hCG, and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). GlycodelinA, a glycoprotein secreted by decidual cells, has been shown to stimulate progesterone and hCG production in different trophoblast populations[

32,

55]. Here we found that CM from decidualized T-HESC cells stimulates progesterone production in trophoblasts, but this stimulatory effect is significantly reduced when T-HESC are infected with

Brucella prior to decidualization. While the mechanisms involved in this reduced progesterone production remain to be established, these results suggest that

Brucella infection may negatively impact the ability of decidual cells to stimulate progesterone secretion by trophoblasts thus reducing the gestation-promoting effects of this hormone.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Brucella spp. Growth Conditions

B. abortus 2308, B. suis 1330 and B. melitensis 16M (wild type strains, obtained from our collection) were grown in tryptic soy broth at 37 °C with agitation. Bacterial cells were washed twice with sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS), and the respective inocula were adjusted to the desired concentration based on optical density (OD) readings. Aliquots of each inoculum were plated on tryptic soy agar (TSA) and incubated at 37 °C to determine the actual number of colony-forming units (CFU) per mL. All live Brucella manipulations were performed in biosafety level 3 facilities.

4.2. Cell Lines

The human endometrial stromal cell line used in this study (T-HESC, kindly provided by Dr. Andrea Randi, University of Buenos Aires) was derived from normal stromal cells through immortalization by telomerase (hTERT) transfection, and conserved the characteristics of the regular endometrial cells [

56]. T-HESC were maintained in DMEM-F12 (without phenol red) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, 50 mM sodium pyruvate and 500 ng/mL puromycin. For infection assays, cells were cultured for 24 h in antibiotic-free culture medium.

The human trophoblastic cell line Swan-71, obtained from normal first trimester trophoblasts through immortalization by hTERT transfection, was kindly provided by Dr. Gil Mor (Wayne State University). These cells conserve most phenotypical characteristics of primary trophoblasts as well as their biological responses[

57]. Swan-71 cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, 50 mM sodium pyruvate.

4.3. Cellular Infections

T-HESC cells were dispensed at 5x104 cells/well in 24-well plates, and were cultured for 24 h in antibiotic-free medium at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were infected with B. abortus, B. melitensis or B. suis at a multiplicity of infection (MI) of 50, 250 or 500 for 2 h. After dispensing the bacterial suspension, the plates were centrifuged (10 min at 400 xg) and then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Non-internalized bacteria were eliminated by several washes with medium alone followed by incubation in medium supplemented with 100 µg/ml gentamicin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin. After that, cells were washed and then incubated with culture medium without antibiotics.

4.4. Decidualization of T-HESC Endometrial Cells

T-HESC were infected or not with

B. abortus,

B. suis or

B. melitensis at different MIs (50, 250, 500) as described above, and 24 h later cells were subjected to decidualization treatment as described previously [

58], with minor modifications. Briefly, T-HESC (5x104 cells/well) were cultured in DMEM/F12 2% FBS with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, 1 µM) and dibutyryl cAMP (0.5 mM). The culture medium was replaced every 48 hours to maintain hormonal stimulation. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 throughout the experiment. Decidualization status was evaluated at 1, 2, 4, and 6 days after the initiation of treatment by measuring prolactin levels in the culture supernatants using a sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.5. Preparation of Conditioned Media from Infected and Decidualized T-HESC

Conditioned media (CM) were obtained from T-HESC that had undergone sequentially the infection and decidualization procedures described above. After 8 days of decidualization treatment, culture supernatants were collected and subsequently filtered through 0.22 µm pore-size filters to ensure sterility. To obtain control CM, mock-infected T-HESC were subjected to the same decidualization protocol to simulate the infection and decidualization conditions without bacterial exposure. The levels of CXCL8 (interleukin-8, IL-8) and CCL2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, MCP-1) were measured in these CM using commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems).

4.6. Cytokine Response of Trophoblasts Stimulated with T-HESC Conditioned Media

To evaluate the impact of a Brucella-infected decidua on the cytokine response of adjacent trophoblasts, Swan-71 cells (5x104 cells/well) were stimulated with CM from infected and non-infected decidualized stromal cells. The CM was applied at 1:2 and 1:5 dilution. After 24 and 48 h of stimulation, culture supernatants were collected to measure interleukin-6 (IL-6), CXCL8, and CCL2 levels using commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems). To determine the cytokine production specifically attributable to the stimulated trophoblasts, baseline cytokine levels present in the corresponding CM were subtracted from the measured levels in the stimulated cultures.

4.7. Progesterone Response of Trophoblasts Stimulated with T-HESC Conditioned Media

Swan-71 trophoblasts (5x104 cells/well) were stimulated for 48 h with CM from infected and decidualized T-HESC (B. abortus, B. suis and B. melitensis infections) or from non-infected decidualized cells. Culture supernatants of the stimulated trophoblasts were harvested to determine progesterone levels using a commercial ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical Company, USA) following the instructions of the manufacturer.

4.8. Functional Response of Trophoblasts Stimulated with T-HESC Conditioned Media

a) Migration. The effect of CM from infected and non-infected decidualized stromal cells on the migration ability of trophoblasts was evaluated using the scratch test essentially as described by Rattila et al. [

59]. Swan-71 cells were plated at 5x104 cells/well in culture medium without antibiotics to allow the formation of a confluent layer. The following day, the culture medium was carefully removed and cells were gently washed with DMEM-F12. A vertical scratch was performed through the monolayer using a pipette tip, and cells were cultured in the presence of CM from infected and non-infected decidualized stromal cells. Swan-71 cells cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% FBS were used as a positive control of migration. Pictures were taken at time 0 and later on the same microscopic field at 18 h post-stimulation. Each wound area in duplicate wells was measured with ImageJ software. The degree of wound closure was calculated as: [(area time 0 h - area time = 18h) / area time = 0 h] x 100. The independent experiments were repeated three times.

b) Invasion. Trophoblast invasive capacity was evaluated as described by Rattila et al. [

60]. A Geltrex matrix (0.6 mg/mL in DMEM-F12) was applied to Transwell inserts (8 µm pore size) in 24-well plates to simulate the basal membrane. Swan-71 cells (3×104) were pre- treated for 1 hour with CM (1:2 dilution) from non-infected or

Brucella-infected decidualized stromal cells (

B. abortus,

B. suis,

B. melitensis, MI 250), then seeded in the upper chamber on top of the Geltrex matrix. CM was maintained throughout the assay in the upper chamber.

In the lower chamber of the insert 500 µl of DMEM-F12 with 10% FCS were dispensed. After 18 h of culture the medium was removed and the matrix was cleaned with a cotton swab. Transwells were very carefully washed with PBS and were fixed with PFA 4% for 15 min. After a further wash, the transwells were stained with crystal violet for 15 min. The excess of colorant was removed with distilled water and the membrane was carefully cleaned with a swab on the upper side, without touching the lower chamber to avoid the removal of cells that crossed the matrix and the membrane. The membranes of inserts were analyzed using an EVOS microscope (Thermo Fisher) to determine the number of cells that crossed the membranes. The positive control wells included 10% FBS as the attractive stimulus to check the functionality of cells.

c) Tubulogenesis. This assay was performed essentially as described by Rattila et al.[

59]. A Geltrex matrix (9 mg/ml in DMEM-F12) was dispensed in a 96-well plate. When gelification was complete, Swan-71 cells (2x104/well) previously stimulated for 1 h with CM from infected (

B. abortus,

B. suis or

B. melitensis, MI 50, 250 or 500) or non-infected stromal decidualized cells were dispensed. After 6 h the wells were imaged using an EVOS microscope (Thermo Fisher) to evaluate the number of master junctions, master segments and meshes using using ImageJ software and the Angiogenesis Analyser plugin. CM were kept during the whole assay.

4.9. Evaluation of the Chemotactic Effect of Conditioned Media from Decidualized Stromal Cells on Trophoblasts

To assess the chemotactic effect of CM from decidualized stromal cells, either infected with Brucella or not, a Transwell-based migration assay was performed. This assay aims to determine whether soluble factors present in the CM can promote the directed migration of trophoblast cells. A similar protocol to the invasion assay described above was used, with key modifications to specifically evaluate chemotaxis. CM from infected (MI 250, three Brucella species) or non-infected decidualized stromal cells was placed in the lower chamber of the transwell inserts, while Swan-71 cells were seeded in the upper chamber on a Geltrex matrix without prior CM treatment. The assay was conducted for 6 hours, with 2% FBS present in both chambers to control for serum-driven migration. The membranes of inserts were analyzed using an EVOS microscope (Thermo Fisher) to determine the number of cells retained in the membranes.

4.10. Neutralization of CXCL8 and CCL2 in Conditioned Media

To test the role of CXCL8 and CCL2 in the effects produced by CM from infected or non-infected decidualized stromal cells, in some experiments these CM were preincubated for 1 h with neutralizing antibodies against these chemokine (R&D Systems) in two different concentrations (0.5 µg/ml and 1 µg/ml). The neutralizing antibodies in CM were maintained for the duration required for each functional assay in which they were used. In some experiments CM were preincubated with mixtures of both antibodies.

4.11. Spheroids Adhesion to the Infected Decidua

In order to form blastocyst-like spheroids[

61], Swan-71 cells were stained with VybrantTM DiD (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) and were dispensed in a low-binding Petri dish at 2x104 cells per 20 ul drop of medium (DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 2% FCS). Cells were incubated at 37 °C with agitation for 48 h. At this time cells were observed under the optical microscope to check whether the spheroids had formed correctly.

T-HESC cells were plated at 1x104 cells/well in 96-well plates, were infected (or not) with the tested Brucella species (MI 50, 250, 500) and were later decidualized as described above. Trophoblasts spheroids were carefully laid on the decidualized cells using a pipette with a blunt end tip to avoid damaging the spheroids. Images were taken at time 0 (T0) and 24 h later (T24) using an EVOS microscope (Thermo Fisher), and were analyzed using ImageJ software. Spheroids areas were measured at both time points and results were expressed as relative spheroid outgrowth calculated as: area T24/area T0.

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed in duplicate on three separate occasions. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by either Tukey’s post hoc test or Dunnett’s post hoc test, with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

Figure 1.

Brucella pre-infection impairs the decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. Endometrial stromal cells from the T-HESC line were infected with B. abortus (Ba), B. melitensis (Bm), or B. suis (Bs) at different multiplicities of infection (MI) or were left uninfected (NI) as controls. At 24 h post-infection, both infected or non-infected cells were subjected to the decidualization protocol. Culture supernatants were collected at day 6 post-decidualization, and prolactin (PRL) levels were quantified by ELISA. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. *** p<0.0001 versus NI.

Figure 1.

Brucella pre-infection impairs the decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. Endometrial stromal cells from the T-HESC line were infected with B. abortus (Ba), B. melitensis (Bm), or B. suis (Bs) at different multiplicities of infection (MI) or were left uninfected (NI) as controls. At 24 h post-infection, both infected or non-infected cells were subjected to the decidualization protocol. Culture supernatants were collected at day 6 post-decidualization, and prolactin (PRL) levels were quantified by ELISA. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. *** p<0.0001 versus NI.

Figure 2.

Brucella preinfection induces a proinflammatory chemokine response in decidualized human endometrial cells. T-HESC cells were infected with the different Brucella species (MI 250) or were left uninfected (NI) as controls. At 24 h post-infection, both infected and non-infected cells were subjected to the decidualization protocol for 8 days. Cells were incubated for a further 24 or 48 h, and at culture supernatants were harvested for measuring CXCL8 and CCL2 using commercial ELISA kits. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. ns: non-significant; ***p<0.001 versus NI at the corresponding time point.

Figure 2.

Brucella preinfection induces a proinflammatory chemokine response in decidualized human endometrial cells. T-HESC cells were infected with the different Brucella species (MI 250) or were left uninfected (NI) as controls. At 24 h post-infection, both infected and non-infected cells were subjected to the decidualization protocol for 8 days. Cells were incubated for a further 24 or 48 h, and at culture supernatants were harvested for measuring CXCL8 and CCL2 using commercial ELISA kits. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. ns: non-significant; ***p<0.001 versus NI at the corresponding time point.

Figure 3.

Factors secreted by Brucella-infected decidualized stromal cells stimulate a proinflammatory response in trophoblasts. Trophoblasts from the Swan-71 cell line were stimulated for 24 or 48 h with conditioned medium from B. abortus–infected and later decidualized THESC cells (CM Ba) or from non-infected but decidualized cells (CM NI). After stimulation, CXCL8, IL-6, and CCL2 levels in the culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. Cytokine levels present in the CMs were subtracted from those detected in the supernatants of stimulated trophoblast to account for baseline cytokine presence. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. NS: non-stimulated control. ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; ****p<0.0001 versus NS.

Figure 3.

Factors secreted by Brucella-infected decidualized stromal cells stimulate a proinflammatory response in trophoblasts. Trophoblasts from the Swan-71 cell line were stimulated for 24 or 48 h with conditioned medium from B. abortus–infected and later decidualized THESC cells (CM Ba) or from non-infected but decidualized cells (CM NI). After stimulation, CXCL8, IL-6, and CCL2 levels in the culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. Cytokine levels present in the CMs were subtracted from those detected in the supernatants of stimulated trophoblast to account for baseline cytokine presence. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. NS: non-stimulated control. ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; ****p<0.0001 versus NS.

Figure 4.

Brucella infection reduces the ability of decidualized T-HESC cells to stimulate progesterone production in trophoblasts. Swan-71 trophoblasts were stimulated with CM from B. abortus-, B suis-, or B. melitensis–infected and later decidualized THESC cells (CM Ba, CM Bs and CM Bm, respectively) or from non-infected but decidualized cells (CM NI), or were kept non-stimulated (NS). At 48 h post-stimulation culture supernatants were harvested to measure progesterone with a commercial ELISA. The results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. **** p<0.0001; *** p= 0.0004; ** p= 0.002 versus CM NI.

Figure 4.

Brucella infection reduces the ability of decidualized T-HESC cells to stimulate progesterone production in trophoblasts. Swan-71 trophoblasts were stimulated with CM from B. abortus-, B suis-, or B. melitensis–infected and later decidualized THESC cells (CM Ba, CM Bs and CM Bm, respectively) or from non-infected but decidualized cells (CM NI), or were kept non-stimulated (NS). At 48 h post-stimulation culture supernatants were harvested to measure progesterone with a commercial ELISA. The results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. **** p<0.0001; *** p= 0.0004; ** p= 0.002 versus CM NI.

Figure 5.

Brucella infection of decidual stromal cells impairs the adhesion of trophoblast spheroids. THESC cells were infected with Brucella species at different multiplicities of infection (MI) or were left uninfected (NI), and were then decidualized. Blastocyst-like spheroids formed by non-infected trophoblasts were then laid on decidualized cells. Pictures were taken at 0 y a las 24 h to measure the area of spheroid outgrowth. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over bars indicate differences versus the NI condition (** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001).

Figure 5.

Brucella infection of decidual stromal cells impairs the adhesion of trophoblast spheroids. THESC cells were infected with Brucella species at different multiplicities of infection (MI) or were left uninfected (NI), and were then decidualized. Blastocyst-like spheroids formed by non-infected trophoblasts were then laid on decidualized cells. Pictures were taken at 0 y a las 24 h to measure the area of spheroid outgrowth. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over bars indicate differences versus the NI condition (** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001).

Figure 6.

Conditioned medium from Brucella abortus-infected decidual cells impairs trophoblast migration. Swan-71 trophoblasts were dispensed at 5 x 104 cells/well and were grown until confluence. A scratch was performed in the culture with a pipette tip, and then cells were stimulated with conditioned medium from B. abortus–infected and later decidualized THESC cells (CM Ba) or from non-infected but decidualized cells (CM NI). Stimulation with the corresponding CM was maintained during the whole assay. Swan-71 cells cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% FBS were used as a positive control of migration (+C). To evaluate wound closure, pictures were taken at time 0 and at 18 h post-stimulation on the same microscopic field. Pictures were processed using ImageJ software. The percentage of wound healing was calculated as: [(area time 0 h - area time = 18h) / area time = 0 h] x 100. In parallel experiments, CM Ba and CM NI were preincubated (or not) for 1 hour with two concentrations (0.5 and 1 µg/ml) of neutralizing antibodies against CXCL8 (A and B) or CCL2 (C and D) or a mixture of both (E and F) before performing the wound healing assay. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over bars indicate differences versus the +C condition, whereas asterisks over lines indicate differences between antibody-treated and untreated conditions (*p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001).

Figure 6.

Conditioned medium from Brucella abortus-infected decidual cells impairs trophoblast migration. Swan-71 trophoblasts were dispensed at 5 x 104 cells/well and were grown until confluence. A scratch was performed in the culture with a pipette tip, and then cells were stimulated with conditioned medium from B. abortus–infected and later decidualized THESC cells (CM Ba) or from non-infected but decidualized cells (CM NI). Stimulation with the corresponding CM was maintained during the whole assay. Swan-71 cells cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% FBS were used as a positive control of migration (+C). To evaluate wound closure, pictures were taken at time 0 and at 18 h post-stimulation on the same microscopic field. Pictures were processed using ImageJ software. The percentage of wound healing was calculated as: [(area time 0 h - area time = 18h) / area time = 0 h] x 100. In parallel experiments, CM Ba and CM NI were preincubated (or not) for 1 hour with two concentrations (0.5 and 1 µg/ml) of neutralizing antibodies against CXCL8 (A and B) or CCL2 (C and D) or a mixture of both (E and F) before performing the wound healing assay. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over bars indicate differences versus the +C condition, whereas asterisks over lines indicate differences between antibody-treated and untreated conditions (*p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001).

Figure 7.

Conditioned medium from infected decidualized stromal cells impairs trophoblast invasion capacity. Swan-71 trophoblasts were incubated for 1 hour with conditioned medium (CM) from decidual cells infected with B. abortus (Ba), B. suis (Bs) or B. melitensis (Bm), or from non-infected cells (NI). Then, trophoblasts were seeded onto a protein matrix-coated membrane placed in the upper compartment of a Transwell system and were maintained with continuous exposure to CM. The lower compartment was supplemented with DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS to promote invasion. At 18 h of culture, the cells retained on the membrane were stained and quantified using microscopy-based image analysis. The same experiment was performed with pre-treatment of CM from both infected and non-infected cells with neutralizing antibodies against CXCL8 (A) or CCL2 (B). The results represent the number of cells in the membrane (migrating cells) and are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over bars indicate differences versus the CM NI condition whereas asterisks over lines indicate differences between antibody-treated and untreated conditions (** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001).

Figure 7.

Conditioned medium from infected decidualized stromal cells impairs trophoblast invasion capacity. Swan-71 trophoblasts were incubated for 1 hour with conditioned medium (CM) from decidual cells infected with B. abortus (Ba), B. suis (Bs) or B. melitensis (Bm), or from non-infected cells (NI). Then, trophoblasts were seeded onto a protein matrix-coated membrane placed in the upper compartment of a Transwell system and were maintained with continuous exposure to CM. The lower compartment was supplemented with DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS to promote invasion. At 18 h of culture, the cells retained on the membrane were stained and quantified using microscopy-based image analysis. The same experiment was performed with pre-treatment of CM from both infected and non-infected cells with neutralizing antibodies against CXCL8 (A) or CCL2 (B). The results represent the number of cells in the membrane (migrating cells) and are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over bars indicate differences versus the CM NI condition whereas asterisks over lines indicate differences between antibody-treated and untreated conditions (** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001).

Figure 8.

Brucella infection of decidualized stromal cells impairs their chemotactic capacity for trophoblasts. Swan-71 cells suspended in medium with 2% FBS were seeded onto a protein matrix-coated membrane placed in the upper compartment of a Transwell system. Conditioned media (CM) from decidual stromal cells infected with B. abortus (Ba), B. suis (Bs) or B. melitensis (Bm) or from non-infected cells (NI) were placed in the lower compartment to evaluate chemotactic activity. After 6 hours of incubation, cells retained on the membrane were stained and quantified using microscopy-based image analysis. The same experiment was performed with pre-treatment of CM from both infected and non-infected cells with neutralizing antibodies against CXCL8 (A) or CCL2 (B). The results represent the number of cells in the membrane (migrating cells) and are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over groups indicate differences versus the CM NI condition, while asterisks over lines indicate differences between antibody-treated and untreated conditions (***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; ns: non-significant).

Figure 8.

Brucella infection of decidualized stromal cells impairs their chemotactic capacity for trophoblasts. Swan-71 cells suspended in medium with 2% FBS were seeded onto a protein matrix-coated membrane placed in the upper compartment of a Transwell system. Conditioned media (CM) from decidual stromal cells infected with B. abortus (Ba), B. suis (Bs) or B. melitensis (Bm) or from non-infected cells (NI) were placed in the lower compartment to evaluate chemotactic activity. After 6 hours of incubation, cells retained on the membrane were stained and quantified using microscopy-based image analysis. The same experiment was performed with pre-treatment of CM from both infected and non-infected cells with neutralizing antibodies against CXCL8 (A) or CCL2 (B). The results represent the number of cells in the membrane (migrating cells) and are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over groups indicate differences versus the CM NI condition, while asterisks over lines indicate differences between antibody-treated and untreated conditions (***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; ns: non-significant).

Figure 9.

Factors produced by Brucella-infected decidualized stromal cells impair trophoblast tubulogenesis. Swan-71 cells were seeded on a protein matrix (Geltrex) and incubated for 6 h with conditioned media (CM) from B. abortus, B. suis or B. melitensis-infected decidual cells (MI 50, 250 or 500) or from non-infected cells (NI), or were left untreated (Basal). After incubation, images were captured using a microscope to assess the number of master segments (A), meshes (B) and master junctions (C). The results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over the bars indicate differences versus the Basal condition whereas asterisks over lines indicate differences versus CM NI (** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001; ns: non-significant). Representative images of the assay are shown in panel D.

Figure 9.

Factors produced by Brucella-infected decidualized stromal cells impair trophoblast tubulogenesis. Swan-71 cells were seeded on a protein matrix (Geltrex) and incubated for 6 h with conditioned media (CM) from B. abortus, B. suis or B. melitensis-infected decidual cells (MI 50, 250 or 500) or from non-infected cells (NI), or were left untreated (Basal). After incubation, images were captured using a microscope to assess the number of master segments (A), meshes (B) and master junctions (C). The results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over the bars indicate differences versus the Basal condition whereas asterisks over lines indicate differences versus CM NI (** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001; ns: non-significant). Representative images of the assay are shown in panel D.

Figure 10.

Proinflammatory chemokines induced by

Brucella infection in decidual cells contribute to the reduced ability of trophoblasts to form tubular structures. A tubulogenesis assay was performed as indicated in

Figure 9, but conditioned media (CM) from

Brucella-infected decidual cells were preincubated with neutralizing antibodies (Ab) against CXCL8 or CCL2 before addition to Swan-71 trophoblasts. After incubation, images were captured using a microscope to assess the number of master segments (A), meshes (B) and master junctions (C). The results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over bars indicate differences versus the untreated CM NI (white bar), whereas asterisks over lines indicate differences between each Ab-treated and the untreated CM for each

Brucella species (*p <0.05; ** p<0.01; **** p<0.0001; ns: non-significant).

Figure 10.

Proinflammatory chemokines induced by

Brucella infection in decidual cells contribute to the reduced ability of trophoblasts to form tubular structures. A tubulogenesis assay was performed as indicated in

Figure 9, but conditioned media (CM) from

Brucella-infected decidual cells were preincubated with neutralizing antibodies (Ab) against CXCL8 or CCL2 before addition to Swan-71 trophoblasts. After incubation, images were captured using a microscope to assess the number of master segments (A), meshes (B) and master junctions (C). The results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Asterisks over bars indicate differences versus the untreated CM NI (white bar), whereas asterisks over lines indicate differences between each Ab-treated and the untreated CM for each

Brucella species (*p <0.05; ** p<0.01; **** p<0.0001; ns: non-significant).