1. Introduction

Myotonic dystrophy is an autosomal dominant multisystem disorder with variable penetrance [

1]. Two types of myotonic dystrophy have been described, type 1 myotonic dystrophy (DM1) [

2,

3] and type 2 myotonic dystrophy (DM2). [

4] DM1 is caused by an unstable expansion of a CTG trinucleotide repeat within the myotonic dystrophy pyruvate kinase (DMPK) gene at 19q13.3 (OMIM 160900) [

5]. DM2 is caused by a genetic mutation involving unstable expansions of CCTG repeats within the CNBP gene (also known as ZNF9 at 3q21 (OMIM 602668). [

6] While type 2 myotonic dystrophy is almost exclusively limited to adults, type 1 myotonic dystrophy can present at any age [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Cardiac involvement is common in both DM types [

7,

8,

9].

Brugada syndrome (BrS; OMIM 601144) is a conduction abnormality follows an autosomal dominant mode of transmission and is genetically heterogeneous. BrS is characterized by the occurrence of ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads (V1 to V3), referred to as electrocardiogram (ECG) type I. BrS is responsible for sudden cardiac death (SCD) in individuals with an anatomically normal heart, and it mainly affects men in their third and fourth decades of life. [

10] The main genetic cause of BrS is represented by variations in the SCN5A gene, which account for up to 25% of all clinically diagnosed BrS patients. An additional 27 genes have been associated with the disease, but these are considered minor genes collectively representing approximately 5 to 10% of cases [

11,

12,

13,

14].

A patient with genetically confirmed DM2 who developed clinically significant cardiac arrhythmias and syncopal episodes has been described. [

15] This patient showed Brugada-like ECG findings. Family history was negative for BrS. SCN5A gene sequencing revealed a previously unreported genetic variant c.4140 C > A, p.N1380K. [

15] Loss-of-function mutations in the SCN5A gene, which are associated with the development of Brugada syndrome, have also been found in patients with type 1 myotonic dystrophy [

16,

17]. It is has been proposed that disrupted RNA splicing may alter the normal splicing of SCN5A leading to altered mRNA transcripts, which can result in the production of abnormal proteins or even protein degradation in patients with type 1 myotonic dystrophy [

18]

We investigated a patient with genetically confirmed DM2 who presented with clinically relevant ventricular arrhythmias and a Brugada-type ECG pattern. We report, for the first time, the presence of a variant in the ANK2 gene, associated with BrS, in a patient with genetically confirmed DM2.

2. Case Presentation

The index case was a 70-year-old woman of Italian origin who was affected by DM2. She had a positive family history of DM2 and demonstrated myotonia on electromyography (EMG).

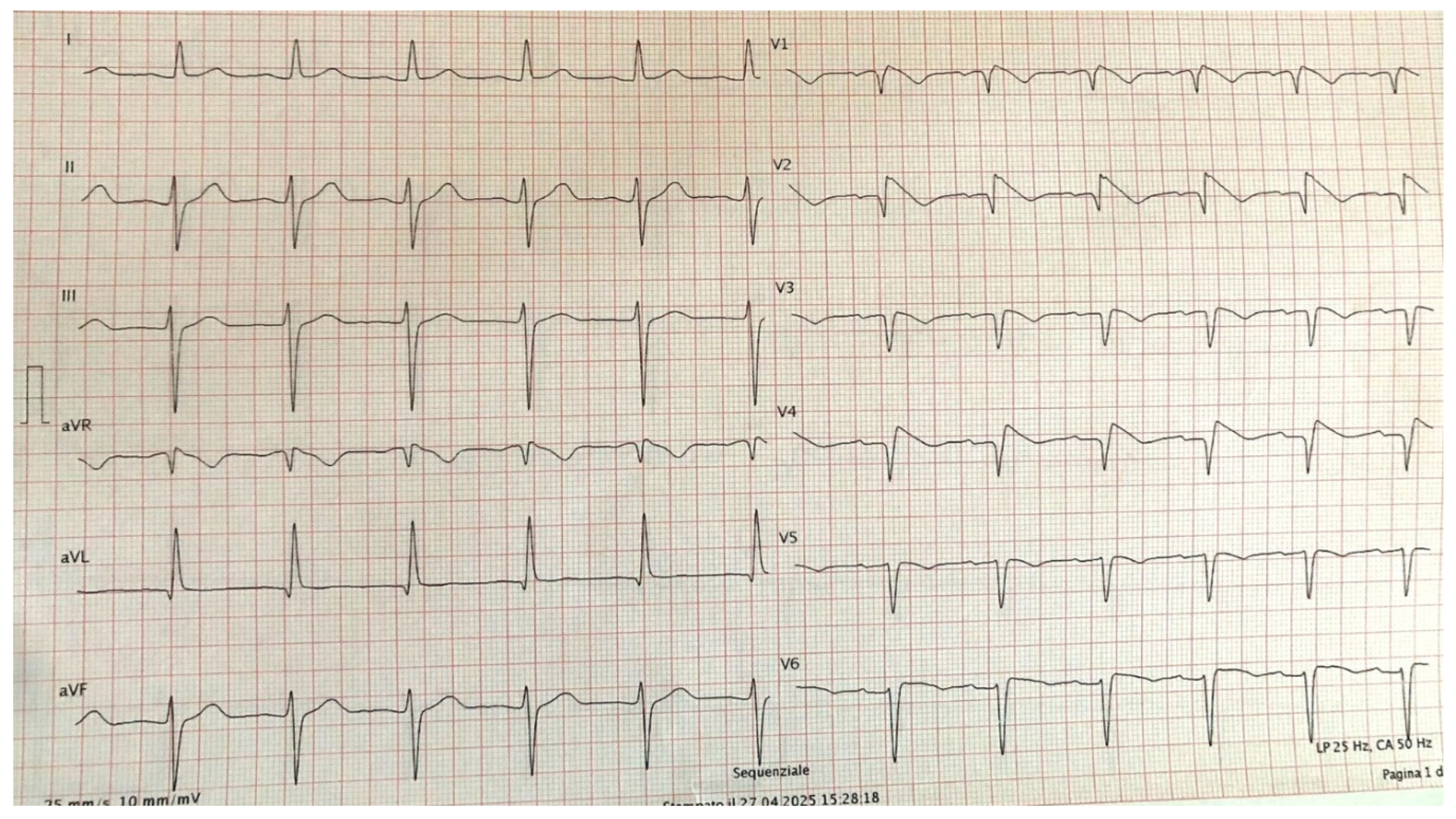

The patient had been hypertensive for approximatively two years and was recently admitted to the neurology department due to a transient ischemic attack (TIA). Subsequently, she underwent a cardiology evaluation, during which a Brugada pattern (Type II) was identified, characterized by marked ST-segment elevation in the precordial leads. Her family history was negative for BrS. As a result, a flecainide challenge test was recommended. Flecainide (100 mg) was administered intravenously over 10 minutes. During continuous ECG monitoring, a progressive accentuation of ST segment elevation in V1-V2 at the second and third intercostal space was observed. Approximately 6 minutes after administration, the ECG converted to type 1 BrS pattern (

Figure 1). No arrhythmias were detected during the monitoring period. The observed type 1BrS pattern completely resolved, and ECG returned to baseline approximately 45 minutes later.

3. Genetic Analysis

The patient underwent pre-test counselling during which she was informed about the significance of molecular analysis and provided written informed consent for the anonymous use of her clinical data. The study was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Genetic analysis for DM2 diagnosis was performed in 2024 at the Medical Genetics Unit at Tor Vergata Hospital, one of the main reference diagnostic labs for myotonic dystrophies in Italy. Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh blood with EZ1 automatic extraction workstation (Qiagen). Diagnostic testing for DM2 was carried out following established protocols, using a combination of both Short-Range (SR-PCR) and Long-Range PCR (LR-PCR) targeting the expanded region of the CNBP gene [

19,

20]. PCR fragments obtained from SR-PCR were analyzed on the SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Long-Range PCR and blotting of PCR products for the detection of CNBP expanded alleles were performed using a 5’ digoxigenin-labelled (CCTG)5 DNA probe.

To investigate BrS genetics determinants in the patient, whole-exome sequencing (WES) investigation was performed as previously described. Library preparation was carried out using Illumina DNA prep with enrichment (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Exome-enriched libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 550 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Raw reads were quality-checked, and low quality reads were removed using the Analysis Toolkit (GATK 1.6). Variant annotation was performed using eVai (Expert Variant Interpreter) engenome. [

21]

The

Supplementary Material (Table S1) contains the gene panel used for investigating arrhythmic sudden death syndromes. This includes candidate genes associated with BrS, other well-known arrhythmias, and genes related to arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies validated in in vivo models.

4. Results

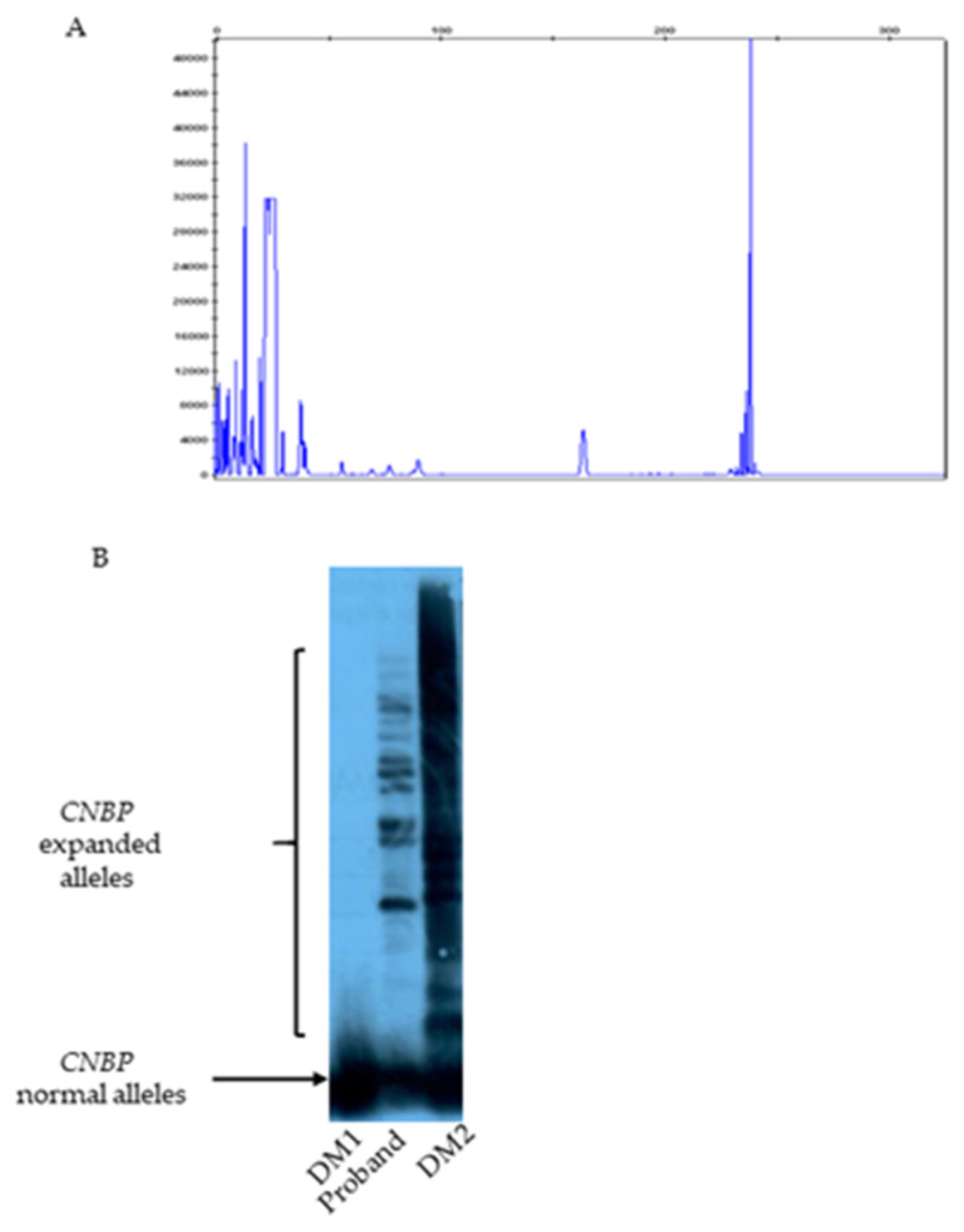

Short range PCR analysis using primers across the DM2 repeated region, followed by capillary electrophoresis, revealed a single 239 bp signal within the normal alleles range of the CNBP gene (

Figure 2A). Subsequent Long Range PCR and Southern blotting analysis using a (CCTG)5 DNA probe detected multiple hybridization signals corresponding to CNBP expanded alleles in both the patient and a DM2 positive control, thereby confirming the molecular diagnosis of DM2. (

Figure 2B)

WES sequencing allowed the identification in DM2 patient of a novel variant in the ANK2 gene (NM_001148.6), which encodes ankyrin-B, located on chromosome 4 at position 4q25-q26. No pathogenic variants involving other known BrS susceptibility genes were detected.

The heterozygous missense variant identified, c.37G>A p.(Gly13Arg) (rs745356870), is located in exon 1 of the ANK2 gene. This variant results from a G-to-A substitution at nucleotide position 37, leading to the substitution of glycine with arginine at amino acid position 13. (

Table 1)

This variant is extremely rare in the general population (gnomAD exomes: ƒ = 0.000003421). It occurs at a highly conserved site (phyloP score: 8.65), where glycine is consistently preserved across species. In silico predictive tools suggest a damaging effect: PolyPhen-2 predicts the variant to be “probably damaging” (score: 0.975), and CADD v1.7 assigns a high deleteriousness score (32). SAM (Sequence Analysis Methods) using MobiDB-lite identified residue #13 within a region enriched in basic and acidic residues (range: amino acids 1–14), which are crucial for protein structure, stability, and function. Additionally, residue #13 is located within a disordered region of the ANK2 protein (range: amino acids 1–34), which may further contribute to functional disruption (

Table 2).

5. Discussion

In the current study, we investigated a 70-year-old woman of Italian origin affected by DM2, who demonstrated myotonia on electromyography. Genetic testing confirmed the diagnosis of DM2. Molecular analysis revealed the presence of a (CCTG)n repeat expansion in the CNBP gene, consistent with the clinical phenotype.

The patient also exhibited clinically significant ventricular arrhythmias based on Brugada-type electrocardiographic findings.

Muscular dystrophies are a group of inherited disorders affecting both skeletal and cardiac muscle [

2]. Two forms of myotonic dystrophy have been described: type 1 (DM1) and type 2 (DM2). Cardiac involvement is common in both forms [

6,

9]. In DM1, the most frequent cardiac manifestations beyond the neonatal period include dilated cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias, including Brugada syndrome (BrS) [

7]. In DM2, cardiac conduction defects, supraventricular arrhythmias, and cardiomyopathy are known to occur. However, to date, only one DM2 patient has been reported with Brugada syndrome associated with a novel SCN5A variant. This suggests that Brugada syndrome may also occur in DM2, as it has been observed in DM1. [

15]

Brugada syndrome is a well-recognized cause of sudden cardiac death in young individuals without structural heart abnormalities. [

24,

25] Although only a limited number of SCN5A variants have been definitively associated with BrS, over 20 genes have been implicated in its pathogenesis. [

26,

27] Loss-of-function variants in the ANK2 gene, which encodes ankyrin-B, have been linked to a variety of cardiac arrhythmias including long QT syndrome (LQTS), sinus node dysfunction, conduction disorders, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, and Brugada syndrome. [

28]

Ankyrin-B, a member of the ankyrin protein family, plays a critical role in regulating the expression and membrane localization of cardiac ion channels, transporters, receptors, and signaling molecules [

29]. The canonical 220-kDa ankyrin-B protein consists of several functional domains [

30]: The N-terminal membrane-binding domain (MBD) contains 24 highly conserved ankyrin (ANK) repeats involved in protein-protein interactions; The spectrin-binding domain (SBD) comprises a tandem of zinc-binding domains (ZU5N-ZU5C-UPA) that mediate interaction with spectrin; The regulatory domain (RD) includes a death domain (DD) and a variable C-terminal domain (CTD).

Variants in ANK2 associated with cardiac disease are distributed across these different functional regions.

In our case, the DM2 patient demonstrated a pharmacologically induced BrS-ECG pattern and was found to carry a ANK2 gene variant, c.37G>A, p.(Gly13Arg), identified through whole-exome sequencing. The heterozygous variant identified has a rare frequency, affected an amino acid residue highly conserved among all species. The substitution of a glycine for an arginine was predicted to be highly likely deleterious (CADD v1.7 score 32). SAM - Sequence Analysis Methods for automatic annotation- MobiDB-lite identify the residue #13 in a region with composition bias-basic and acid residue (Range aa 1-14). These charged residues play crucial roles in protein structure, stability, and function. In addition, SAM- MobiDB-lite localize residue #13 in a disordered region of ANK2 protein (Range: aa 1 – 34). Disordered regions are structurally flexible protein segments that play regulatory roles. More frequently disordered regions result mutated in patients than in relatively healthy individuals, and it has been demonstrated that they carry a set of characteristic functional features. It has been reported that Disordered protein segments are biologically important and lead to pathogenesis upon mutation. The heterozygous missense variant is extremely rare in the general population and affects a glycine residue highly conserved across species. The glycine-to-arginine substitution is predicted to be deleterious, with a CADD v1.7 score of 32, indicating a high likelihood of pathogenicity. SAM (Sequence Analysis Methods) using MobiDB-lite identified residue #13 as part of a region enriched in charged amino acids (range: aa 1–14), which are essential for protein structure, stability, and function. Furthermore, the same residue is located in a disordered region of the ankyrin-B protein (range: aa 1–34). Disordered protein regions are structurally flexible and play important regulatory roles. It has been reported that these regions are more frequently mutated in patients than in healthy individuals and are associated with distinct functional characteristics. Mutations in disordered protein segments have been shown to contribute to disease pathogenesis.

6. Conclusions

Our data suggest that the ANK2 p.(Gly13Arg) substitution may be associated with autosomal dominant Brugada syndrome in the investigated DM2 patient. We hypothesize that the presence of charged residues at this position could play a critical role in the structure, stability, and function of the ankyrin-B protein.

In conclusion, the ANK2 p.(Gly13Arg) variant may contribute to altered calcium homeostasis and represent a potential cause of Brugada syndrome in a patient with DM2. This finding supports the hypothesis that Brugada-type arrhythmias can occur in DM2, as has been observed in DM1.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, DA.M., DA.MR., and M.M.; methodology, DA.M., DA.MR., P.MP., and M.M.; validation, R.A., DE.G., and M.M.; formal analysis, B.A.; resources, S.R., N.G., and M.M.; data curation, DA.M., B.A., S.F., N.G., and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, DA.M., B.A., and DA.MR.; writing—review and editing, S.R., N.G., and M.M.; visualization, G.DA., supervision, DA.M., and B.A.; project administration, N.G., and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author recognizes the financial contribution of European Union– NextGenerationUE as part of PNRR MUR – M4C2 – Investimento 1.3 - Public Call “Partenariati Estesi” - D.D. n. 341/2022 and PNRR MUR - M6C2 – Investment 2.1 Enhancement and strengthening of biomedical research in the NHS.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee) of Policlinico Foggia University-Hospital (protocol code 3261/CE/20).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hahn C, Salajegheh MK. Myotonic disorders: A review article. Iran J Neurol. 2016 Jan 5;15(1):46-53.

- Echenne B, Bassez G: Congenital and infantile myotonic dystrophy. Handb Clin Neurol, 2013; 113: 1387–93.

- Ho G, Cardamone M, Farrar M: Congenital and childhood myotonic dystrophy: Current aspects of disease and future directions. World J Clin Pediatr, 2015; 4(4): 66–80.

- Suominen T, Bachinski LL, Auvinen S et al: Population frequency of myo tonic dystrophy: Higher than expected frequency of myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2) mutation in Finland. Eur J Hum Genet, 2011; 19(7): 776–82.

- Campbell C: Congenital myotonic dystrophy. J Neurol Neurophysiol, 2012; S7.

- Liquori C, Ricker K, Moseley ML, et al. Myotonic dystrophy type 2 caused by a CCTG expansion in intron 1 of ZNF9. Science 2001; 293: 864–867.

- Groh WJ, Groh MR, Saha C, et al. Electrocardiographic abnormalities and sudden death in myotonic dystrophy type 1. N Eng J Med 2008; 358: 2688–2697.

- Day JW, Ricker K, Jacobsen BS, et al. Myotonic dystrophy type 2: molecular, diagnostic and clinical spectrum. Neurology 2003; 60: 657–664.

- Wahbi K, Meune C, Becane HM, et al. Left ventricular dysfunction and cardiac arrhythmias are frequent in type 2 myotonic dystrophy: a case control study. Neuromuscul Disord 2009; 19: 468–472.

- Miyazaki, T.; Mitamura, H.; Miyoshi, S.; Soejima, K.; Aizawa, Y.; Ogawa, S. Autonomic and antiarrhythmic drug modulation of ST segment elevation in patients with Brugada syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1996, 27, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Luna, A.B.; Brugada, J.; Baranchuk, A.; Borggrefe, M.; Breithardt, G.; Goldwasser, D.; Lambiase, P.; Riera, A.P.; Garcia-Niebla, J.; Pastore, C.; et al. Current electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of Brugada pattern: A consensus report. J. Electrocardiol. 2012, 45, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priori, S.G.; Wilde, A.A.; Horie, M.; Cho, Y.; Behr, E.R.; Berul, C.; Blom, N.; Brugada, J.; Chiang, C.E.; Huikuri, H.; et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRSexpert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhyth mia syndromes: Document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm Off. J. Heart Rhythm Soc. 2013, 10, 1932–1963. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1200 11 of 13 6. 7. 8. 9.

- Crotti, L.; Brugada, P.; Calkins, H.; Chevalier, P.; Conte, G.; Finocchiaro, G.; Postema, P.G.; Probst, V.; Schwartz, P.J.; Behr, E.R. From gene-discovery to gene-tailored clinical management: 25 years of research in channelopathies and cardiomyopathies. Europace 2023, 25, euad180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Apolito M, Santoro F, Ranaldi A, Cannito S, Santacroce R, Ragnatela I, Margaglione A, D’Andrea G, Brunetti ND, Margaglione M. Genetic Background and Clinical Phenotype in an Italian Cohort with Inherited Arrhythmia Syndromes and Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (ACM): A Whole-Exome Sequencing Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Jan 30;26(3):1200.

- Rudnik-Schöneborn S, Schaupp M, Lindner A, Kress W, Schulze-Bahr E, Zumhagen S, Elbracht M, Zerres K. Brugada-like cardiac disease in myotonic dystrophy type 2: report of two unrelated patients. Eur J Neurol. 2011 Jan;18(1):191-4.

- Pambrun T, Mercier A, Chatelier A et al: Myotonic dystrophy type 1 mim ics and exacerbates Brugada phenotype induced by Nav1.5 sodium channel loss-of-function mutation. Heart Rhythm, 2014; 11(8): 1393–400.

- Perez-Riera AR, Baranchuk A, Zhang L et al: Myotonic dystrophy and Brugada syndrome: A common pathophysiologic pathway? J Electrocardiol, 2017; 50(4): 513–17.

- Wahbi K, Algalarrondo V, Becane HM et al: Brugada syndrome and abnormal splicing of SCN5A in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Arch Cardiovasc Dis, 2013; 106(12): 635–43.

- Bonifazi E, Vallo L, Giardina E, Botta A, Novelli G. A long PCR-based molecular protocol for detecting normal and expanded ZNF9 alleles in myotonic dystrophy type 2. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2004 Sep;13(3):164-166.

- Botta, A., Bonifazi, E., Vallo, L., Gennarelli, M., Garrè, C., Salehi, L., et al. (2006). Italian guidelines for molecular analysis in myotonic dystrophies. Acta Myol. 25, 23–33.

- d’Apolito M, Ceccarini C, Savino R, Adipietro I, di Bari I, Santacroce R, Curcetti M, D’Andrea G, Croce AI, Cesarano C, Polito AN, Margaglione M. A Novel KCNN2 Variant in a Family with Essential Tremor Plus: Clinical Characteristics and In Silico Analysis. Genes (Basel). 2023 Jun 29;14(7):1380.

- D’Apolito M, Santacroce R, Vazquez DO, Cordisco G, Fantini CA, D’Andrea G, Leccese A, Colia AL, Martinez P, Zanichelli A, Josviack D, Margaglione M. DAB2IP associates with hereditary angioedema: Insights into the role of VEGF signaling in HAE pathophysiology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024 Sep;154(3):698-706.

- Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, Kircher M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019 Jan 8;47(D1):D886-D894. Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, Kircher M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019 Jan 8;47(D1):D886-D894.

- d’Apolito M, Pisanelli D, Faletra F, Giardino I, Gigante M, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Goulet O, Gasparini P, Campanozzi A. Genetic analysis of Italian patients with congenital tufting enteropathy. World J Pediatr. 2016 May;12(2):219-24.

- Ahmed SS, Rifat ZT, Lohia R, Campbell AJ, Dunker AK, Rahman MS, Iqbal S. Characterization of intrinsically disordered regions in proteins informed by human genetic diversity. PLoS Comput Biol. 2022 Mar 11;18(3):e1009911. [CrossRef]

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, Gussak I, LeMarec H, Nademanee K, Perez Riera AR, Shimizu W, Schulze-Bahr E, Tan H, Wilde A. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 2005 Feb 8;111(5):659-70.

- Antzelevitch, C. Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006 Oct;29(10):1130-59.

- d’Apolito M, Santoro F, Ranaldi A, Ragnatela I, Colia AL, Cannito S, Margaglione A, D’Arienzo G, D’Andrea G, Pellegrino P, Santacroce R, Brunetti ND, Margaglione M. Investigation of a Large Kindred Reveals Cardiac Calsequestrin (CASQ2) as a Cause of Brugada Syndrome. Genes (Basel). 2024 Jun 21;15(7):822.

- d’Apolito M, Santoro F, Santacroce R, Cordisco G, Ragnatela I, D’Arienzo G, Pellegrino PL, Brunetti ND, Margaglione M. A Novel DLG1 Variant in a Family with Brugada Syndrome: Clinical Characteristics and In Silico Analysis. Genes (Basel). 2023 Feb 8;14(2):427.

- Guo L, Wu D, Zhu W. Reappraisal of ANK2 Variants in Cardiovascular Diseases: Uncovering Mechanisms and Future Directions. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2025 Jan 15;26(1):26013.

- York NS, Sanchez-Arias JC, McAdam ACH, Rivera JE, Arbour LT, Swayne LA. Mechanisms underlying the role of ankyrin B in cardiac and neurological health and disease. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2022; 9: 964675.

- Wang C, Yu C, Ye F, Wei Z, Zhang M. Structure of the ZU5 ZU5-UPA-DD tandem of ankyrin-B reveals interaction surfaces necessary for ankyrin function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012; 109: 4822–4827.

- Sucharski HC, Dudley EK, Keith CBR, El Refaey M, Koenig SN, Mohler PJ. Mechanisms and Alterations of Cardiac Ion Channels Leading to Disease: Role of Ankyrin-B in Cardiac Function. Biomolecules. 2020; 10: 211.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).