Introduction

ICU patients with sedation and drug-induced muscle paralysis have compromised ocular protection mechanisms, making them more susceptible to developing Ocular Surface Diseases (OSDs), of which Exposure Keratopathy (EK) is the most common in the intensive care setting. This condition affects 20-42% of all ICU patients (Hernandez et al., 1997), with 60% of those having been sedated for at least 48 hours (Grixti et al., 2013; Werli-Alvarenga et al., 2011).

The EK manifests as corneal dryness due to excessive tear evaporation on the eye’s surface. If not detected and treated, this condition can lead to ulceration, microbial keratitis and permanent vision loss caused by scarring (Hernandez et al., 1997).

Unfortunately, limited studies are available to determine or compare the effectiveness of various prevention and treatment methods, making it difficult to determine what is the best evidence-based practice for eye care in ICUs patients (Alansari et al., 2015). As a result, these treatments continue to be implemented constructed on individual beliefs or knowledge.

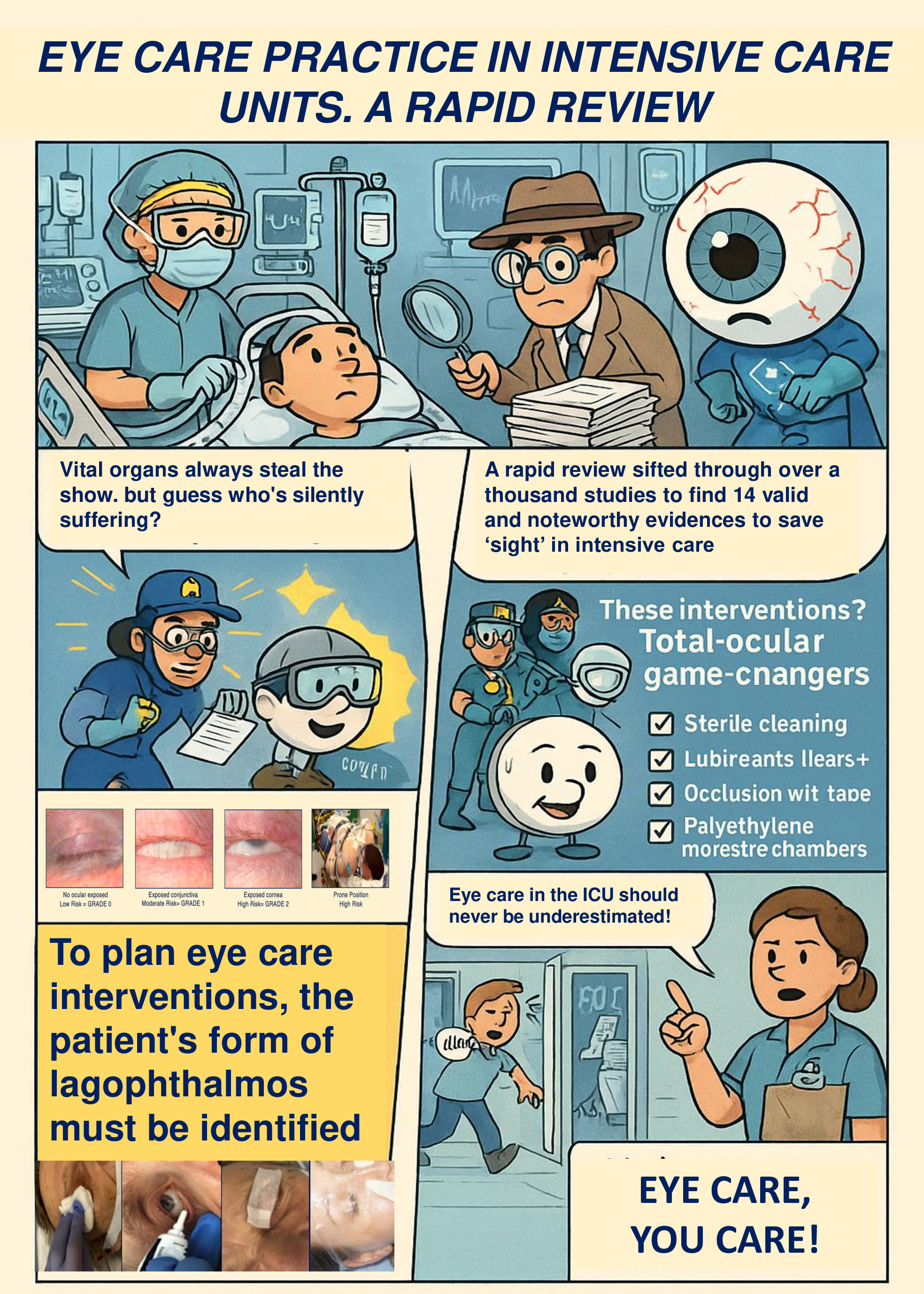

The aim of this rapid review is to identify the main evidence-based eye care practices to prevent and treat OSDs in critically ill, sedated patients on mechanical ventilation in the ICUs.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A rapid review was conducted from February 1 to August 31, 2024, following the method recommended by the World Health Organization (Tricco et al., 2017) and further refined by Langlois et al. (2019) in seven phases: (1) needs assessment and topic selection; (2) study development; (3) literature search; (4) study screening and selection; (5) data extraction; (6) risk of bias assessment; (7) knowledge synthesis.

In accordance with the aim of this study, the search question was: “what are the best evidence-based practices for eye care in patients under sedation and invasive mechanical ventilation to prevent and treat Ocular Surface Diseases (OSD) in Intensive Care Units (ICUs)?”.

The project was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD4202*******.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was designed by all members of the research team and subsequently submitted for expert academic review (AMG). In February 2024, an initial search was conducted in the Google Scholar search engine and the MEDLINE database via PubMed, allowing the authors to identify keywords for the search strategy. From March to May 2024, the MEDLINE database was searched via PubMed, CINAHL (EBSCO), and EMBASE (Elsevier) using the search strings shown in Table 1.

Table 1-Literature Search Strategy.

Study Selection

In compliance with methodological standards for systematic reviews (Page et al., 2021), a screening, eligibility and inclusion process was conducted by two independent ICU experts (LC and SGS). A third independent ICU expert (SL) was consulted to resolve any emerging disagreements.

For the screening, eligibility, and inclusion process, the RYYAN software for systematic reviews was used (Ouzzani et al., 2016). The following inclusion criteria were applied during the search phase: (1) adults (≥18 years old) admitted to ICUs, (2) articles published in English, (3) articles published within the last 10 years. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles referring to pediatric populations (<18 years), (2) settings other than intensive care (e.g., recovery rooms or operating theaters), (3) articles not focused on the nursing contribution.

Quality Methodological Assessment of Included Studies

Only primary studies with well-structured designs were included to reduce the overall risk of bias. These studies were critically appraised independently by two reviewers (LC and MC) using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for assessing methodological quality (risk of bias) (Aromataris et al., 2015).

The appropriate evaluation form was selected according to the research type of the article. Each evaluation checklist had 8 to 13 questions with a label Y = yes, N = no, UC = unclear, NA = not applicable. Studies with a score of ≥7 out of a maximum score of 10 or ≥70% if the maximum score was not 10 were considered high quality; studies with a score of <4 or 40% were considered low quality studies. Studies with a score between 4 and 7 (40%-70%) were considered of medium quality (Mersha et al., 2020). Any disagreements were resolved through consensual discussion between two reviewers.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

Due to the clinical heterogeneity (intervention strategy, duration of interventions) and studies desing it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis of the extracted data, the results obtained are reported in narrative form.

The target factors were first classified according to ocular damage and then organised chronologically in the data extraction table. Further results, relating to the general characteristics and methodological quality (risk of bias) of the included studies, were organised in customised tables.

Results

Search Results

A total of n=1305 records were initially identified through database searches. Following the application of automated tools and the removal of duplicates, n=1095 records were excluded. The remaining n=210 records underwent a preliminary screening based on title and abstract. Of these, n = 167 studies were excluded for not meeting the predefined inclusion criteria. Subsequently, n=43 full-text articles were retrieved for detailed assessment. After full-text review, n=12 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Additionally, a manual search using other sources, including Google Scholar and backward citation tracking, yielded n=2 further eligible studies. Therefore, a total of n=14 studies were included in the final synthesis (Kalhori et al., 2015; Bendavid et al., 2017; Babamohamadi et al., 2018; Kousha et al., 2018; Vyas et al., 2018; de Araujo et al., 2019; Dhanapala et al., 2021; Badparva et al., 2021; Pourghaffari et al., 2021; Nikseresht et al., 2021; Yu, et al., 2021; Rezaei et al., 2022; Mobarez et al., 2022, Pai et al., 2023). The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1-Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses PRISMA flow Diagram.

Study Attributes

Details about the study features are reported in Table 2. All the articles are covering the last 10 years. This rapid review included research from n=6 countries. Data synthesis revealed that 43% of the articles (n=6) were published before 2019, while the remaining 57% (n=8) were published between 2020 and 2024. 79% (n=11) of the studies were conducted in Asia. Analyzing the study design, 64% (n=9) were experimental with a strong prevalence of RCTs, and the remaining 36% (n=5) were observational. Across the studies, ICUs patients were predominantly sedated, mechanically ventilated, and at risk of OSDs, with sample sizes ranging from 27 to 371 patients. Several interventions were investigated, including polyethylene covers, preservative-free artificial tears, vitamin A and antibiotic-based ophthalmic ointments, moisture chambers, eye taping techniques, and structured nursing protocols. Comparative effectiveness among these interventions varied; however, polyethylene covers and ointments emerged consistently as effective strategies for preventing exposure keratopathy and other ocular complications. A minority of studies also evaluated the impact of nursing education and protocol adherence on patient outcomes, with findings indicating significant reductions in ocular morbidity following structured training. Overall, the reviewed studies provided clinically relevant, though methodologically heterogeneous, evidence for constructing evidence-based nursing protocols tailored to eye care in the intensive care setting.

Table 2—Data Summary.

Table 3—Study Attributes.

Methodological Quality

Analysis of the data using the JBI checklists revealed that 72% (n=10) studies were of good quality, 28% (n=4) studies were of moderate quality, and no studies were of poor quality. Regarding the included observational studies, the data showed good quality in terms of study design and data collection, with some limitations related to sample representativeness and control of sampling bias. On the other hand, the experimental studies generally met the criteria for randomization and blinding, although some studies had follow-up issues that could affect the reliability of the results.

Table 4—Quality Assessment of the Included Studies.

Discussion

A total of n=14 full-text articles were included from the international literature, encompassing eyes care practices in over 1,322 sedated patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation across various countries. Notably, no prior rapid reviews addressing this topic were identified, making the present study the first of its kind.

Based on a multidimensional assessment of methodological quality, the included studies demonstrated a high degree of consistency, clinical relevance, and both internal and external validity, with 72% of them classified as high-quality.

The narrative synthesis revealed that a primary objective of ocular care in critically ill patients is the maintenance of ocular surface integrity through adequate cleaning and hydration, primarily by minimizing tear evaporation. Interventions were generally tailored to the degree of lagophthalmos and accompanied by environmental adjustments, such as regulating ambient light, temperature (22.5–25.5 °C), and humidity (50–60%) (Yu et al., 2021). For ocular cleansing, several studies recommended cleaning every 2–4 hours, or at least once per nursing shift, using sterile gauze soaked in isotonic saline or sterile water (Werli-Alvarenga et al., 2011; Kousha et al., 2018; Hearne et al., 2018; Vyas et al., 2018; Sanghi et al., 2021). Direct irrigation with isotonic saline alone, however, is not advisable due to the associated risk of cross-contamination and a higher incidence of ocular surface disorders (Werli-Alvarenga et al., 2011; Davoodabady et al., 2018). To maintain corneal hydration, preservative-free lubricants ointments applied at regular intervals (every 2, 4, 8, or 12 hours) are preferred, as noted by Şimşek et al. (2018). These lubricating ointments have demonstrated greater effectiveness than manual eyelid closure or artificial tears alone (Ahmadinejad et al., 2020). Notably, Hearne et al. (2018) found no significant difference between frequent ocular lubrication and eyelid taping with microporous tape in preventing corneal abrasions in patients with Grade 1 lagophthalmos. Lubricating agents have thus long constituted a cornerstone of ICU eye care protocols (Werli-Alvarenga et al., 2011). More recent evidence favors the use of moisture chambers—such as polyethylene film or swimming goggles—which provide comprehensive corneal coverage and effectively reduce tear evaporation. A meta-analysis by Rosenberg and Eisen (2008) demonstrated the superior protective effect of moisture chambers compared to lubricating ointments. Additional advantages include easier application and less frequent reapplication, improving compliance with care protocols. Sanghi et al. (2021) also found that artificial eye shields and polyethylene film offered superior corneal protection compared to lubricating drops, with efficacy comparable to lubricating ointments. Although data are limited, vitamin A–based ophthalmic ointments appear beneficial in preventing corneal injury among unconscious, mechanically ventilated patients (Badparva et al., 2021; Babamohamadi et al., 2018). Similarly, prophylactic or therapeutic use of antibiotic ointments containing 0.3% ofloxacin or 1% chloramphenicol (sificetin) is supported in selected cases. When microbiological testing yields specific sensitivities, targeted antibiotic therapy is recommended (Kousha et al., 2018; Vyas et al., 2018).

It is worth noting that only one of the included studies focused on patients in the prone position, limiting generalizability for this subgroup. However, the recommendations by Lightman & Montgomery (2020) and Sanghi et al. (2021) suggest similar eye care strategies as those employed for supine patients, including frequent ocular cleansing, eyelid taping with microporous tape, application of preservative-free lubricants, and use of polyurethane films (10 × 10 cm), in conjunction with postural adjustments such as anti-Trendelenburg positioning and head rotation every 4 hours, where feasible.

Importantly, ICU nurses have demonstrated the ability to screen for ocular surface disorders, such as exposure keratopathy and keratoconjunctivitis, with acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity (McHugh et al., 2008). Regular nursing assessments and documentation of ocular condition may facilitate early identification and timely management, improving clinical outcomes.

This rapid review underscores an often-overlooked aspect of patient safety in intensive care: the prevention and management of ocular surface disorders in deeply sedated, mechanically ventilated patients. Despite their impact on visual function and post-discharge quality of life, these complications are frequently neglected in daily care. The literature demonstrates that protocolised and meticulous eye care substantially reduces ocular morbidity and contributes to better long-term outcomes (Kadri et al., 2011; Demirel et al., 2014; Masoudi et al., 2014). In alignment with international guidelines (Pourghaffari et al., 2021; Lightman & Montgomery, 2020; NSW Agency, 2024), this review synthesizes current evidence into a practical, nurse-led protocol—“Eye Care, You Care”—proposed for implementation in ICU settings (Supplementary Material). By addressing a critical gap in care delivery, this work offers a timely and evidence-based tool for standardizing eye care practices and enhancing multidisciplinary collaboration in critical care environments.

Several limitations of this review must be acknowledged. First, due to heterogeneity in study designs and outcomes, a meta-analysis could not be performed, limiting the ability to derive pooled effect estimates. Second, many of the included observational studies relied on non-probability sampling, which may introduce sampling bias. Finally, despite the structured and systematic nature of the review process, selection and information biases may have occurred due to the limited number of databases searched and the exclusion of grey literature and secondary studies. While the overall methodological quality and relevance of the included studies were deemed acceptable, these limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings and guiding future research.

Conclusions

This rapid review provides the first structured synthesis of current evidence on eyes care for critically ill, sedated, and mechanically ventilated patients in ICU. The findings consistently endorse the implementation of targeted practices—such as regular ocular cleansing, the use of preservative-free lubricating ointments, and moisture chambers—tailored to the degree of lagophthalmos and modifiable environmental conditions. The reviewed literature highlights the urgent need for the development and implementation of standardized, evidence-based protocols to harmonize and enhance eye care practices in the ICU.

Addressing this often-overlooked dimension of patient safety holds the potential to substantially improve clinical outcomes and post-ICU quality of life. While the heterogeneity of study designs precluded meta-analytic synthesis, the methodological consistency and quality of the included studies offer a robust foundation for clinical guidance. The proposed empirical nurse-led protocol “Eye Care, You Care”, operationalizes these findings into a practical tool for routine ICU application. Future high-quality, multicenter research is essential to validate the effectiveness of specific interventions—particularly in patients managed in the prone position—and to support broader protocol implementation across ICU settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

C.L.: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, investigation and writing original draft. S.S.G.: conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, writing-review and editing. L.S.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, validation and writing-review and editing. A.R.: conceptualization, methodology, visualization, and writing-review and editing. C.M.: conceptualization, supervision, and writing-original draft, visualization and writing-review editing. M.G.: conceptualization, visualization, and writing-review editing B.C.: conceptualization and writing-review and editing. G.A.M.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and writing-original draft. G.G.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and writing-original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This declaration adheres to the current guidelines established by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). All individuals involved in the editorial and research process have acted responsibly and in accordance with the ethical principles set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. Authorship has been limited to those who have made substantial contributions to the conception, design, administration, execution, or interpretation of the study. All authors confirm that the submitted work is entirely original. Where the work and/or words of others have been used, appropriate paraphrasing or verbatim quotation has been employed and duly referenced following APA Style. All publications that have informed the rationale or content of the current work have been explicitly cited. The manuscript does not include any copyrighted material previously published elsewhere. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and consent to its submission for publication in the journal. With the submission of this manuscript, the authors agree that, if accepted for publication, all economic rights of exploitation—without limitation of medium, format, or technology, whether existing or future—will be transferred to the Journal and its Publisher. The study was reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional authority (Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico S. Matteo, Pavia, Italy). All participants provided informed consent. Since no patients were involved in the study, submission to an ethics committee was deemed unnecessary according to local regulations. The research was conducted without interference in professional clinical activities, ensuring complete anonymity and privacy of collected data. Moreover, the study did not affect patient care or treatment timelines. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors are available to provide all relevant data and materials upon reasonable request.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the nurses from the Anesthesia and Intensive Care Unit 1 Research Group of Fondazione IRCCS Policlinic S. Matteo for their interest and enthusiasm in participating in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare the total absence of any conflict of interest with respect to the research carried out, authorship and publication of this article.

References

- Ahmadinejad, M., Karbasi, E., Jahani, Y., Ahmadipour, M., Soltaninejad, M., & Karzari, Z. (2020). Efficacy of Simple Eye Ointment, Polyethylene Cover, and Eyelid Taping in Prevention of Ocular Surface Disorders in Critically Ill Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Critical care research and practice, 2020, 6267432. [CrossRef]

- Alansari, M. A., Hijazi, M. H., & Maghrabi, K. A. (2015). Making a Difference in Eye Care of the Critically Ill Patients. Journal of intensive care medicine, 30(6), 311–317. [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E., Fernandez, R., Godfrey, C. M., Holly, C., Khalil, H., & Tungpunkom, P. (2015). Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. International journal of evidence-based healthcare, 13(3), 132–140. [CrossRef]

- Babamohamadi, H., Nobahar, M., Razi, J., & Ghorbani, R. (2018). Comparing Vitamin A and Moist Chamber in Preventing Ocular Surface Disorders. Clinical nursing research, 27(6), 714–729. [CrossRef]

- Badparva, M., Veshagh, M., Khosravi, F., Mardani, A., & Ebrahimi, H. (2021). Effectiveness of lubratex and vitamin A on ocular surface disorders in ICU patients: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 22(2), 136–142. [CrossRef]

- Bendavid, I., Avisar, I., Serov Volach, I., Sternfeld, A., Dan Brazis, I., Umar, L., Yassur, Y., Singer, P., & Cohen, J. D. (2017). Prevention of Exposure Keratopathy in Critically Ill Patients: A Single-Center, Randomized, Pilot Trial Comparing Ocular Lubrication With Bandage Contact Lenses and Punctal Plugs. Critical care medicine, 45(11), 1880–1886. [CrossRef]

- Davoodabady, Z., Rezaei, K., & Rezaei, R. (2018). The Impact of Normal Saline on the Incidence of Exposure Keratopathy in Patients Hospitalized in Intensive Care Units. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research, 23(1), 57–60. [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, D. D., Silva, D. V. A., Rodrigues, C. A. O., Silva, P. O., Macieira, T. G. R., & Chianca, T. C. M. (2019). Effectiveness of Nursing Interventions to Prevent Dry Eye in Critically Ill Patients. American journal of critical care: an official publication, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 28(4), 299–306. [CrossRef]

- Demirel, S., Cumurcu, T., Fırat, P., Aydogan, M. S., & Doğanay, S. (2014). Effective management of exposure keratopathy developed in intensive care units: the impact of an evidence based eye care education programme. Intensive & critical care nursing, 30(1), 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Dhanapala, M., & Sabaretnam, S. (2021). Audit of Eye Care for Ventilated Patients in Intensive Treatment Unit During COVID-19 Pandemic. Sri Lankan Journal of Anaesthesiology, 29(1). [CrossRef]

- Grixti, A., Sadri, M., & Watts, M. T. (2013). Corneal protection during general anesthesia for nonocular surgery. The ocular surface, 11(2), 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Hearne, B. J., Hearne, E. G., Montgomery, H., & Lightman, S. L. (2018). Eye care in the intensive care unit. Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 19(4), 345–350. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, E. V., & Mannis, M. J. (1997). Superficial keratopathy in intensive care unit patients. American journal of ophthalmology, 124(2), 212–216. [CrossRef]

- Kadri, R., Hegde, S., Kudva, A. A., Achar, A., & Shenoy, S. P. (2011). Self-medication with over the counter ophthalmic preparations: is it safe?. Int J Biol Med Res., 2(2), 528-530. [CrossRef]

- Kalhori, R. P., Ehsani, S., Daneshgar, F., Ashtarian, H., & Rezaei, M. (2015). Different Nursing Care Methods for Prevention of Keratopathy Among Intensive Care Unit Patients. Global journal of health science, 8(7), 212–217. [CrossRef]

- Kousha, O., Kousha, Z., & Paddle, J. (2018). Exposure keratopathy: Incidence, risk factors and impact of protocolised care on exposure keratopathy in critically ill adults. Journal of critical care, 44, 413–418. [CrossRef]

- Langlois, E. V., Straus, S. E., Antony, J., King, V. J., & Tricco, A. C. (2019). Using rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems and progress towards universal health coverage. BMJ global health, 4(1), e001178. [CrossRef]

- Lightman, S., & Montgomery, H. (2020). Ophthalmic services guidance: Eye care in the intensive care unit (ICU) (No. 409, pp. 1–14). Royal College of Ophthalmologists. https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Eye-Care-in-the-Intensive-Care-Unit-2020.pdf (accessed: 07/23/2024).

- Masoudi, A.N., Sharifitabar, Z., Shaeri, M., & Adib Hajbaghery, M. (2014). An audit of eye dryness and corneal abrasion in ICU patients in Iran. Nursing in critical care, 19(2), 73–77. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, J., Alexander, P., Kalhoro, A., & Ionides, A. (2008). Screening for ocular surface disease in the intensive care unit. Eye (London, England), 22(12), 1465–1468. [CrossRef]

- Mersha, A. G., Gould, G. S., Bovill, M., & Eftekhari, P. (2020). Barriers and Facilitators of Adherence to Nicotine Replacement Therapy: A Systematic Review and Analysis Using the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behaviour (COM-B) Model. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(23), 8895. [CrossRef]

- Mobarez, F., Sayadi, N., Jahani, S., Sharhani, A., Savaie, M., & Farrahi, F. (2022). The effect of eye care protocol on the prevention of ocular surface disorders in patients admitted to intensive care unit. Journal of medicine and life, 15(8), 1000–1004. [CrossRef]

- Nikseresht, T., Rezaei, M., & Khatony, A. (2021). The Effect of Three Eye Care Methods on the Severity of Lagophthalmos in Intensive Care Patients: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Journal of ophthalmology, 2021, 6348987. [CrossRef]

- NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. Eye care of the critically ill: Clinical Practice Guide. Sydney: ACI; 2024. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/239731/ACI-Eye-Care-of-the-Critically-Ill-Clinical-Practice-Guide.pdf (accessed: 07/07/2024).

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic reviews, 5, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Pai, A., Kamath, A., Vasava, I., Bhosale, D., & Nambiar, G. (2023). Impact of ocular care training of nursing staff on the incidence of ocular surface disorder in medical intensive care unit patients. Indian journal of ophthalmology, 71(4), 1446–1449. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., & Moher, D. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 134, 103–112. [CrossRef]

- Pourghaffari Lahiji, A., Gohari, M., Mirzaei, S., & Nasiriani, K. (2021). The effect of implementation of evidence-based eye care protocol for patients in the intensive care units on superficial eye disorders. BMC ophthalmology, 21(1), 275. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, K., Amini, N., Rezaei, R., Rafiei, F., & Harorani, M. (2022). The Effects of Passive Blinking on Exposure Keratopathy among Patients in Intensive Care Units. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research, 27(2), 144–148. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J. B., & Eisen, L. A. (2008). Eye care in the intensive care unit: narrative review and meta-analysis. Critical care medicine, 36(12), 3151–3155. [CrossRef]

- Sanghi, P., Malik, M., Hossain, I. T., & Manzouri, B. (2021). Ocular Complications in the Prone Position in the Critical Care Setting: The COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of intensive care medicine, 36(3), 361–372. [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, C., Doğru, M., Kojima, T., & Tsubota, K. (2018). Current Management and Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. Turkish journal of ophthalmology, 48(6), 309–313. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Langlois, E. V., & Straus, S. E. (Eds.). (2017). Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide (p. 119). Geneva: World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/258698.

- Vyas, S., Mahobia, A., & Bawankure, S. (2018). Knowledge and practice patterns of Intensive Care Unit nurses towards eye care in Chhattisgarh state. Indian journal of ophthalmology, 66(9), 1251–1255. [CrossRef]

- Werli-Alvarenga, A., Ercole, F. F., Botoni, F. A., Oliveira, J. A., & Chianca, T. C. (2011). Corneal injuries: incidence and risk factors in the Intensive Care Unit. Revista latino-americana de enfermagem, 19(5), 1088–1095. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Y., Xue, L. Y., Zhou, Y., Shen, J., & Yin, L. (2021). Management of corneal ulceration with a moisture chamber due to temporary lagophthalmos in a brain injury patient: A case report. World journal of clinical cases, 9(5), 1127–1131. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).