1. Introduction

Almost all modern buildings have Building Automation Systems (BAS) [

1]. Literature clearly indicates that building automation can be classified as Cyber Physical System (CPS) [

2,

3]. In this context, building automation combines several broader areas like Smart Buildings (SB) [

4], Intelligent Buildings (IB) [

5], smart cities [

6], enhanced living environments [

7], Information and Communication Technology (ICT), Industrial Control Systems (ICS), smart grid [

8], Internet of Things (IoT) [

9] and others. This shows the necessity of combining many different and independent systems into one integrated system.

Khan et al. [

10] recognize the interaction and interconnectivity between the different systems in the CPS environment through the use of ICT. With regard to BAS, for example, [

11] introduced the topic of the energy saving potential in heating, cooling and lighting through ICT based automation systems. Also, the EU`s Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) [

12] recognizes the strong backlog demand regarding the intelligence capability of a building and its underlying controls. In the context of smart devices and sensors, the requirement to connect different BAS’s is also supported by Kastner et al. [

13]. They specifically refer to the increasing requirement for close cooperation between the different trades involved in building automation engineering. Continuing towards broader integration, Hammadi et al. [

14] are clear that indoor guidance and assisting via smartphone will become a significant trend in modern buildings. They also explicitly point to the interaction of smartphones and building automation as the key to implementing such a concept. In the context of linking electrical power systems and BAS, Kiliccote et al. [

15] make clear that smart grids are also on the agenda of smart buildings. ASHRAE [

16] has also started work on corresponding standards for the connection between building automation and smart grid systems. In the broader context of CPS, Zhukabayeva et al. [

17] highlight the integration of networked sensors into cloud applications, while also underscoring the significant number of accompanying security concerns.

The examples given of the diverse interconnection of different systems go hand in hand with a broad and complex attack surface [

2,

17,

18]. Which is reminiscent of the challenges of modern warfare and thus brings into play issues such as asymmetric or hybrid threats or composite vulnerabilities. Hybrid threats refer to a wide range of hostile actions that combine multiple, often unconventional methods to achieve strategic objectives, usually by exploiting multiple vulnerabilities in one or more targets [

19]. Composite vulnerabilities are those vulnerabilities that can occur through the totality or combination of connected systems [

20]. The question arises as to whether such threats are also conceivable in the field of building automation.

The following contributions are made by this paper:

A comprehensive review of field bus systems, protocols and standards used for data transport from sensors in building automation.

An overview of practical examples of threats to building security that have not yet been covered in the literature. Especially with regard to sensor technology in usually unprotected areas.

A thorough analysis of whether literature from the field of warfare or composite vulnerabilities has been previously applied to the field of CPS and specifically to BAS, for the benefit of researchers and practitioners in the field.

The previous part explained the background and motivation for this review paper. The second section describes the necessary context and shows some practical examples.

Section 3 describes the methodology and defines the scope, focus and limitations. The fourth section summarizes the results in categories and describes them in detail. Particularly with regard to their potential applicability in building automation. The final section summarizes the most important results and concludes the key findings, by highlighting aspects of security in building automation that have not yet been considered in the literature.

2. Related Work and Practical Examples

2.1. The Multi-Layered Communication in Building Automation

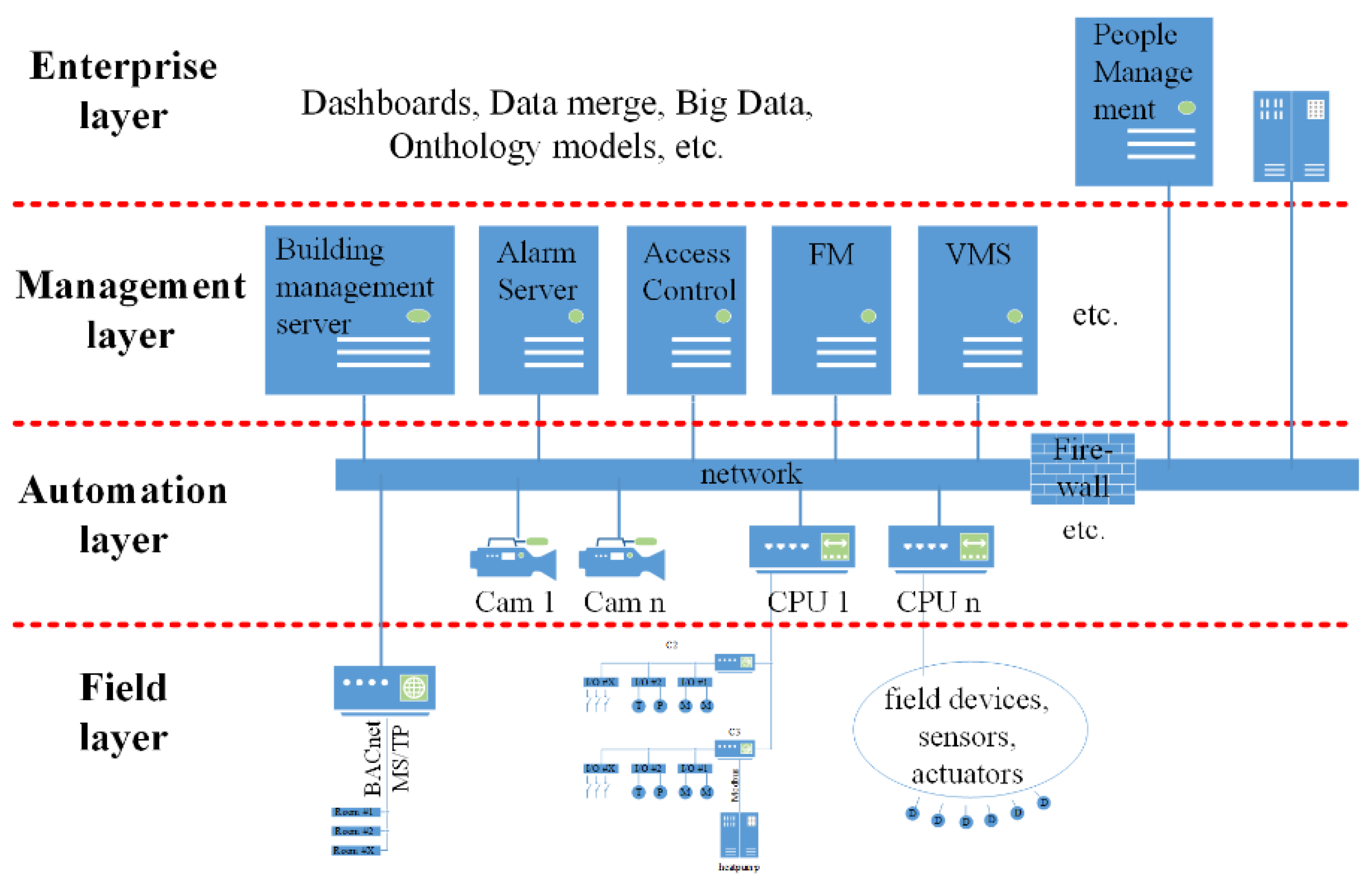

Building automation systems are divided into layered communication, which is supported by several authors and widely used in the literature [

21,

22]. To better illustrate these layers with a picture,

Figure 1 shows the typical four layers of a BAS.

There are different types of building automation and their underlying communication mechanisms. The sensors in the field layer are located all over the building, for example an outside air temperature sensor sits usually on the outside wall, occupancy sensors are located in rooms or corridors and sensors for Air Handling Units (AHU) are located at the AHU itself. The Direct Digital Controllers (DDC) sit in a control panel or are also distributed throughout the building and the workstations and servers of the management layer are usually situated in an office or a dedicated server room [

21]. Data exchange in horizontal communication is primarily used for process control and is characterized by smaller data volumes. Data exchange in vertical communication is primarily intended for the access by the management level and is typically characterized by higher data volumes, e.g. for historical data collection [

13].

2.2. Practical Examples

On the one hand, the following practical examples are intended to illustrate examples that have not yet been dealt with in the literature. On the other hand, these scenarios have been included here in line with [

23], who promote documenting real-world results in order to improve data management and strengthen real-time capabilities of fault detection. Furthermore, these examples should help to understand the criticality of potential composite vulnerabilities and hybrid threats to building automation.

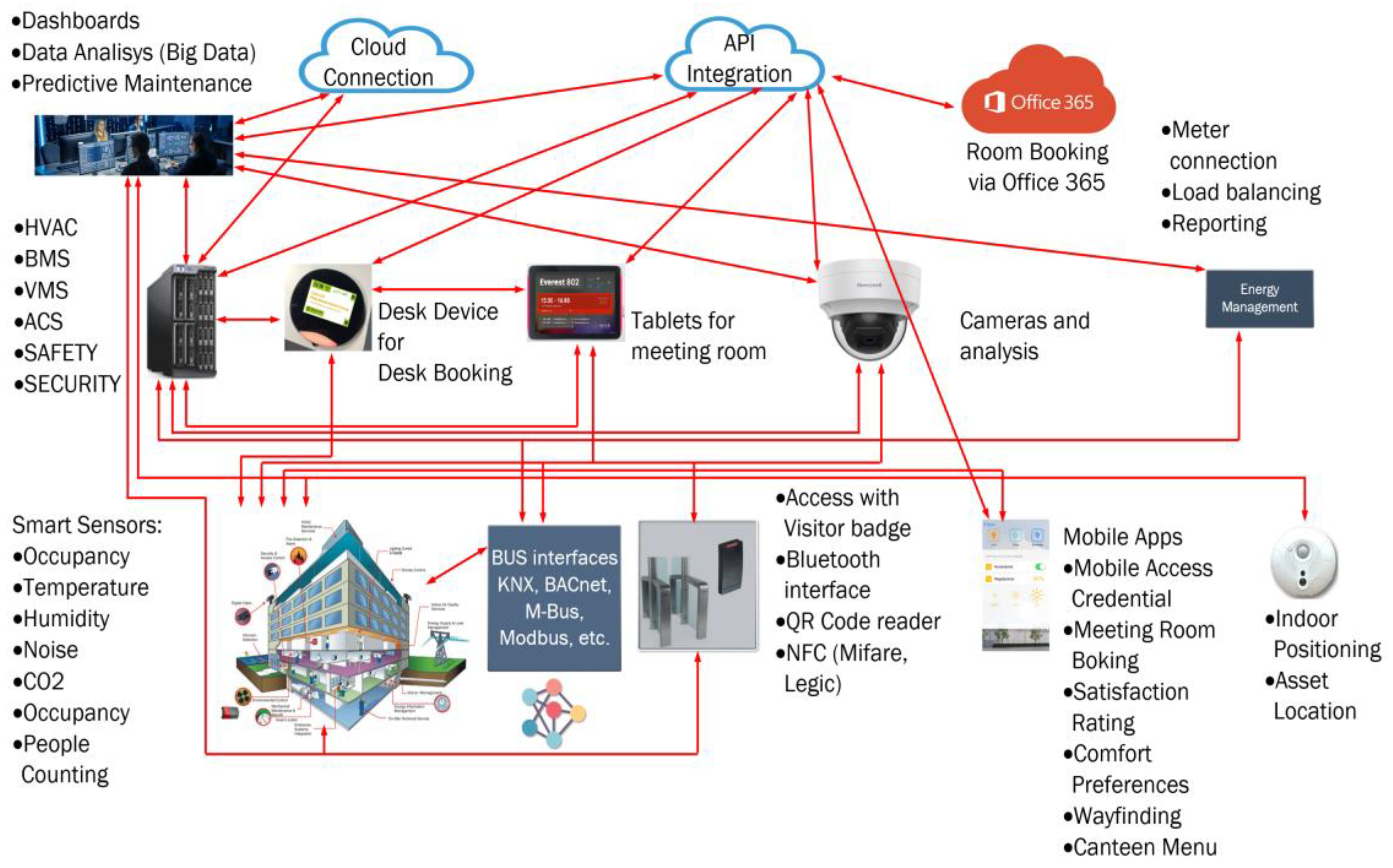

2.2.1. Example 1, Composite Vulnerabilities

A visitor to a building is sent a QR code to their mobile phone after a meeting has been booked via a Microsoft Outlook calendar appointment object. They also receive a floor plan to make it easier to find their way to the relevant meeting room. The visitor then enters the building by presenting the QR code to the access card reader at the entrance door. This event data is stored in the Access Control System (ACS) and recorded by the Video Management System (VMS). If it is an employee, the data is also sent to the human resources payroll system to recognize the employee’s presence and set their daily attendance account to ‘active’. In addition, the visitors way to the office is automatically lit when it is dark and the office space is heated or cooled to the desired temperature. The blinds are also opened or closed depending on the weather conditions. Furthermore, the presence detectors recognize whether people are still in the room and the media control system activates the appropriate lighting scenarios for a presentation. In other words: An ACS is connected to the Time and Attendance (T&A) system, to the payroll system, to the lighting system, to the HVAC (Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning), to the VMS, to the media control panel, to the electrical power supply system and in some way to the mobile phone of an external person.

Figure 2 illustrates this scenario.

Figure 2 also shows a strong fusion between IT and OT (Operational Technology) and a correspondingly strong networking between the various automation systems, which is also currently the focus of the literature [

17,

24]. In addition to the broad attack surface [

2], such scenarios offer the potential for attacks on one system to affect multiple, other connected systems and support the spread of malware.

2.2.2. Example 2, Composite Vulnerabilities

In an airport there is a car rental for electric cars. The power supply of the loading stations does not provide enough power capacity to load all vehicles in parallel. To ensure that the rented vehicle was fully charged at the time of handover, a charging schedule was created. This schedule defined the time and corresponding State of Charge (SOC) of the. Battery. This data was transferred to an SQL (Structured Query Language) database, which was then connected to the controller via an ODBC (Open Database Connectivity) connection. The connected controller was then also used to disconnect other large loads when larger amounts of power were needed for rapid charging. Thus, the controller was connected to many AHU`s (via FOXnet), an electric heater for defrosting a ramp (via ModBus), to the refrigeration compressor network of the entire refrigeration supply (via BACnet) and to the other vehicle loading stations (via Modbus). This common and widespread use of unsecured connections supports potential cyberattacks and represents a large, poorly secured attack surface. For example, an attack could be carried out via the BACnet weather station, which is often poorly secured outdoors, or via BACnet room control units. Furthermore, an attack on a single system can have significant consequences for other systems. For example, an attack on the controller, which is located in the control cabinet of the ventilation system and is therefore more easily accessible, can also result in the de-icing of the access ramp being disabled, which also poses a significant risk of accidents.

2.2.3. Example 3, Composite Vulnerabilities

Following [

8], who had already identified the direct connection between the smart grid, the energy management system, and the HVAC system as a potential threat, such scenarios are also being implemented in practice. For example, energy meters are connected directly to the controller via unsecured protocols (M-Bus, Modbus, BACnet, etc.), which are then often directly connected to enterprise dashboards or cloud solutions. On the one hand, this makes cyberattacks on unsecured protocols easier and, on the other hand, the connections to cloud solutions and enterprise networks make it much easier to spread malware.

2.2.4. Example 4, Hybrid Threats

In buildings, there are usually one or two large air handling units supplying the whole building with fresh air (such as classrooms, event rooms, offices, patient rooms, exhibition rooms, etc.). These AHUs are often equipped with an outside air intake at floor level, which represents a major vulnerability. This allows potentially harmful or lethal gases to be placed near the intake of the ventilation system, causing significant damage and even life-threatening situations without much effort. While this example does not refer to sensors in unprotected areas or unsecured data transmission, it clearly demonstrates the vulnerability of ventilation systems to hybrid attacks. Sensors in the intake tract that detect harmful gases could partially counteract such attacks. However, the most sensible approach would be to install the intake ducts in inaccessible areas, which often involves higher installation costs.

3. Methodology

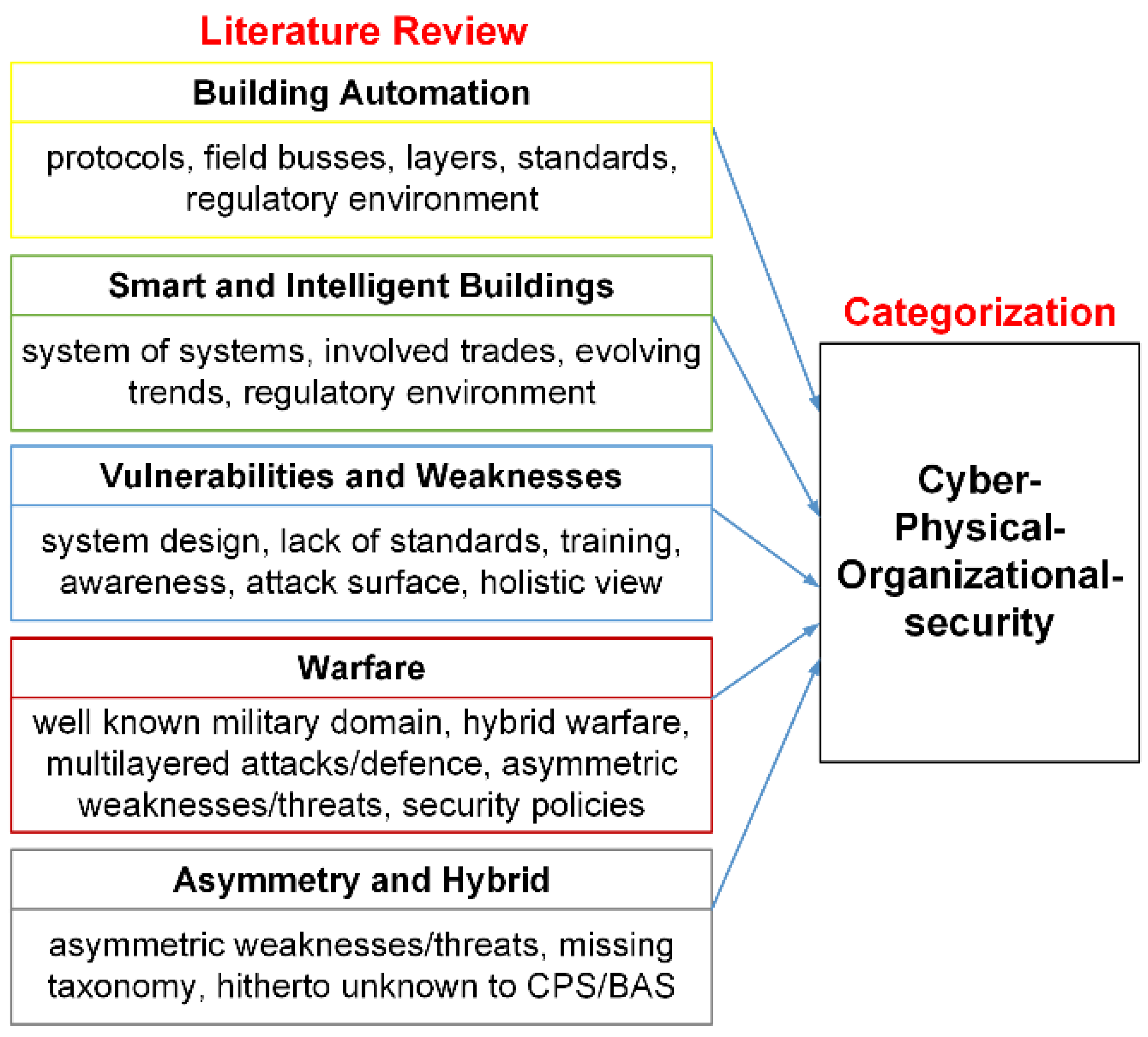

The overall aim was to find literature that can help to improve the security of buildings with building automation systems. Methods from other areas were to be analyzed and then projected onto the security of buildings in general. The security of buildings in this work is to be considered holistically, in order to be able to evaluate as many vulnerabilities as possible.

3.1. Design of the Literature Review

Firstly, the current state of the art in building automation was determined with the aim of demonstrating the implementation or non-implementation of various security mechanisms. This analysis then served as the basis for the applicability of the further topics of investigation.

Figure 3 shows the areas reviewed in literature and their categorization into cyber, physical and organizational security.

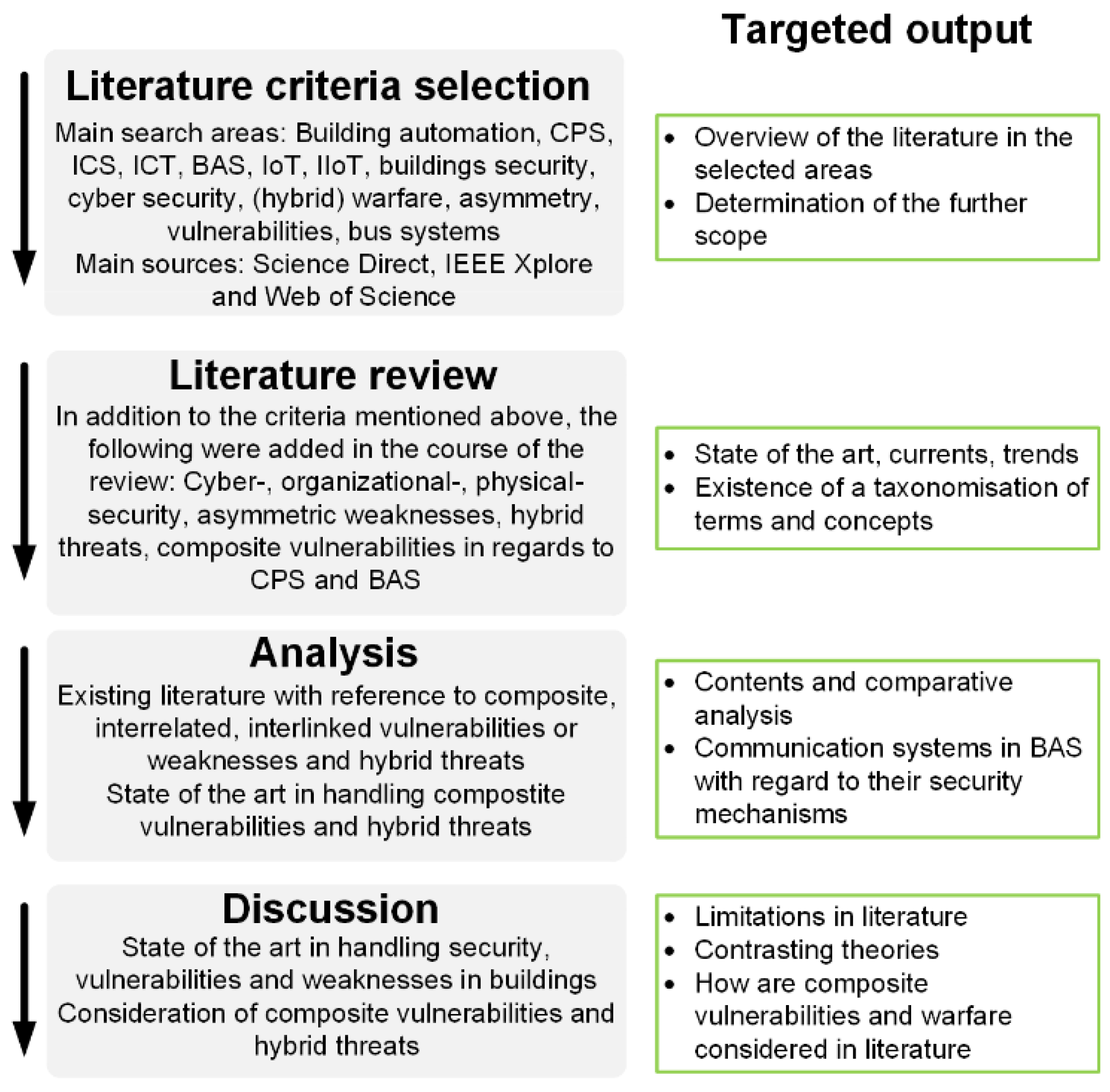

3.2. Review Method and Selection Process

The literatures were first selected on the basis of the title, if inclusion of the title was selected, further selection was made on the basis of the abstract. The initial search areas were intentionally chosen broad, to cover most possible areas which can contain any information about composite, interrelated, interlinked, hybrid and asymmetric vulnerabilities or weaknesses.

Figure 4 shows the methodological process and the desired result of each sub-step.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In order to keep the search scope as broad as possible, the following types of literature were analyzed: Books, conference papers, government documents, journal articles, legal rules or regulations, reports, standards. datasets, electronic articles, online databases, newspaper articles, press releases and webpages. No inclusion or exclusion criteria were defined for authors, the cite score or geographical affiliation. Because of the longevity of BAS [

26], no time restriction was set for the initial searches in order to obtain an overview of the relevant areas. However, if more recent literature on the same topic was available, the more recent literature was favored. Literature regarding safety, natural hazards or events such as floods, storms, earthquakes, avalanches, etc. was excluded. Literature related to terrorist attacks was included if it fell under the above categories. As there were often hits in the context of smart/intelligent buildings, BAS and CPS for the topics data privacy or GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), these were excluded as they did not match our research focus.

3.4. Search Procedure

The platform used in the initial searches was google scholar, as it also performs a search in established research platforms and offers broader coverage across different disciplines [

27]. For further, more detailed research on the specific topics, a separate search was then carried out via the following sources: eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), eBook Open Access (OA), Science Direct, IEEE Xplore, Scopus and Web of Science. A total of 131 search strings were applied, which were then used in the various search queries on the respective topics. The initial search terms were taken from relevant literature on the subject of security in building automation, smart buildings and intelligent buildings [

22,

28,

29,

30,

31].

3.5. Data Extraction and Presentation

Due to the diversity of the areas analyzed, it was not possible or appropriate to present the extracted literature in a single table. The extracted and analyzed reports were therefore presented in the respective areas. The division of the areas into cyber-, physical- and organizational-weaknesses is based on the results of the literature found.

3.6. Quality Declaration

The review was carried out according to the quality criteria and checklists of the Prisma framework [

25] as demonstrated in

Figure 4. As per the partially semi-structured approach, there is a possibility that the results may be distorted, as not all areas of literature on the topic of security in buildings with building automation were possibly found. This bias was counteracted by analyzing all reports for references to other threats or vulnerabilities in the context of buildings.

4. Results of the Literature Review

A total of 548 documents were classified as relevant based on their title and abstract, of which 72 articles were analyzed in detail.

4.1. Occurrences of Real-World Scenarios in the Literature

Articles in the CPS area on threat classification or vulnerabilities related to asymmetry are rare, appearing in only eight out of 29 articles examined. This is essentially also supported by [

32], who suggests that it is important to taxonomize asymmetries in order to better understand how to deal with the corresponding vulnerabilities. Some approaches on new attack vectors for BAS have been made [

33]. In the area of IoT, further contributions deal with the adaptation of existing, standardized databases [

34,

35] that can be followed up and adopted in regards to BAS.

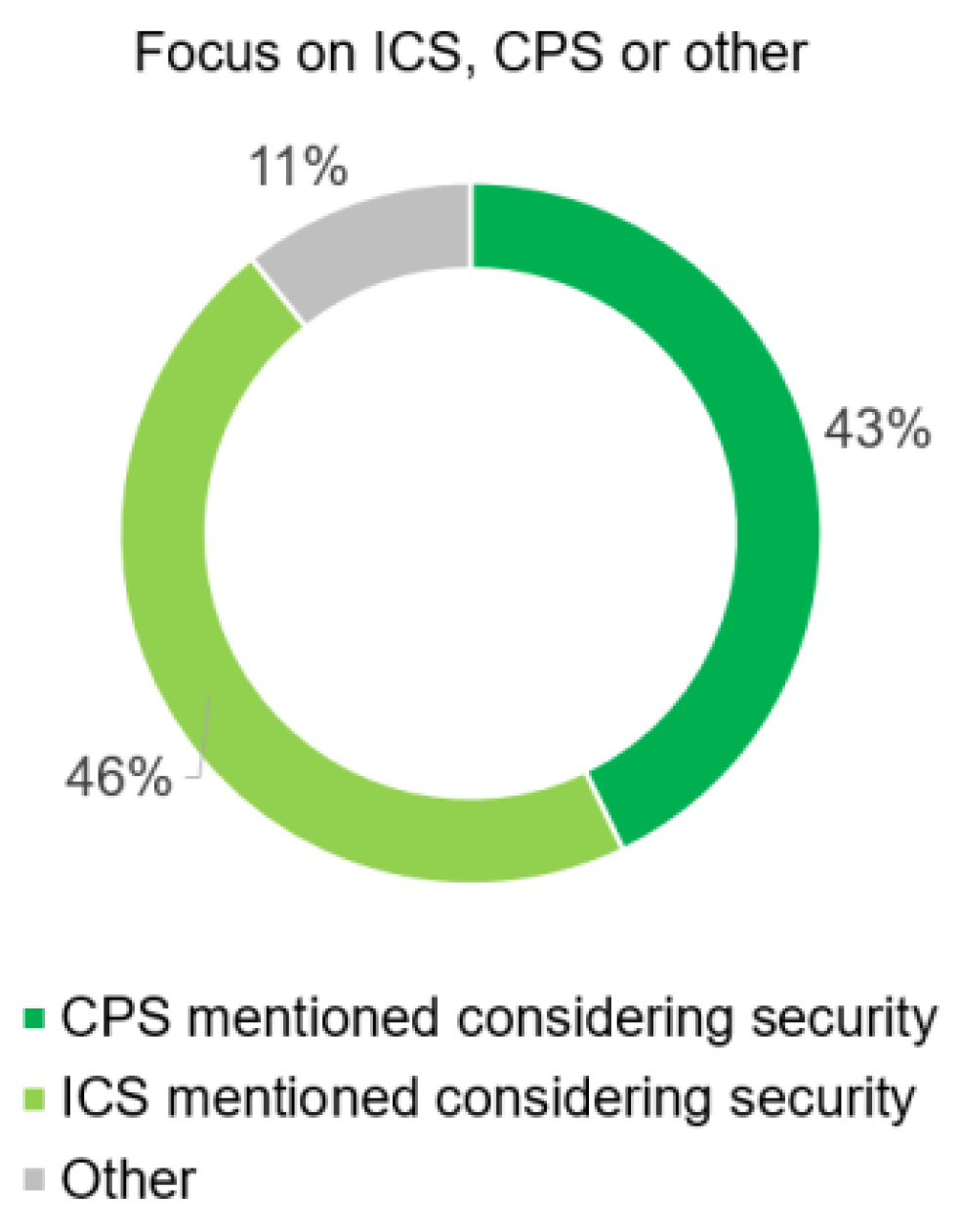

In terms of practical applicability, the distribution of real-world scenarios is interesting, as shown in

Figure 6. The sum of real-world examples and real-world tests scenarios occurs in less than 50% of the literature examined, thus the theoretical treatment of vulnerabilities, weaknesses and threat-scenarios predominates. Which is essentially confirmed by [

24]. The distribution of the reviewed literature in the areas of ICS and CPS is almost equally distributed, shown in

Figure 5.

4.2. Adoption of Standardized Vulnerability Databases for CPS and BAS

Looking at the Common Vulnerability Scoring System CVSS [

36] or the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) [

37], a problem with the various vulnerabilities and their classification is that the information content is sometimes difficult to understand for CPS operators. Often the vulnerabilities are described rather vaguely as information break, distorted input value, channel weakness or similar, which sometimes has little practical significance, allows little conclusion about the effect or the source or just misses out the context to the application [

38]. The origin of these designations usually comes from computer technology and poses great challenges for CPS or BAS operators in terms of understanding the statements, as these statements are too focused on the area of network technology or general IT [

39]. Without appropriately trained personnel or corresponding specialist departments, such vulnerability reports are therefore mostly useless for CPS and BAS owners, or their informative value can usually not be interpreted appropriately and even less implemented in countermeasures. In their current form, these databases are therefore rather unsuitable for use in the BAS area.

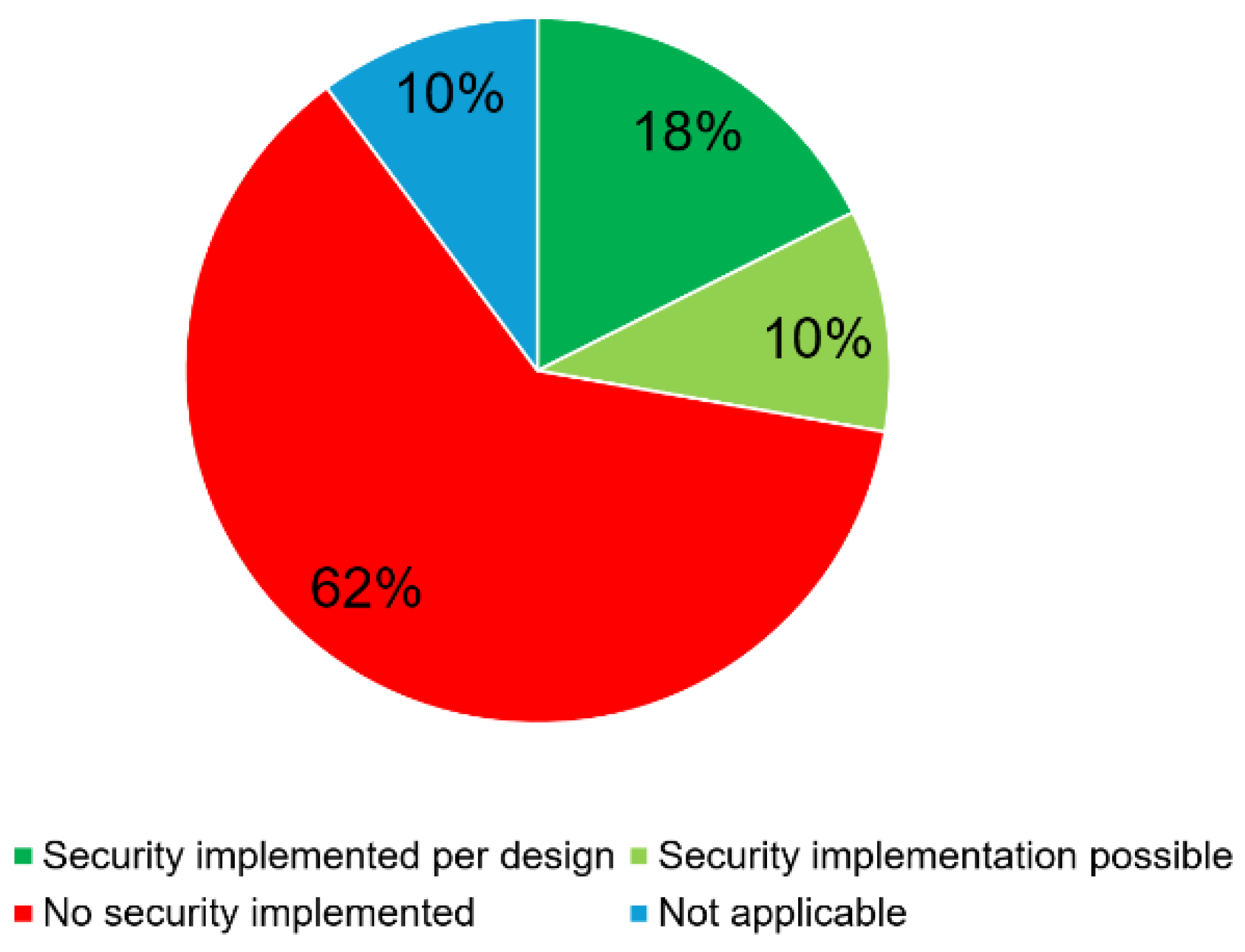

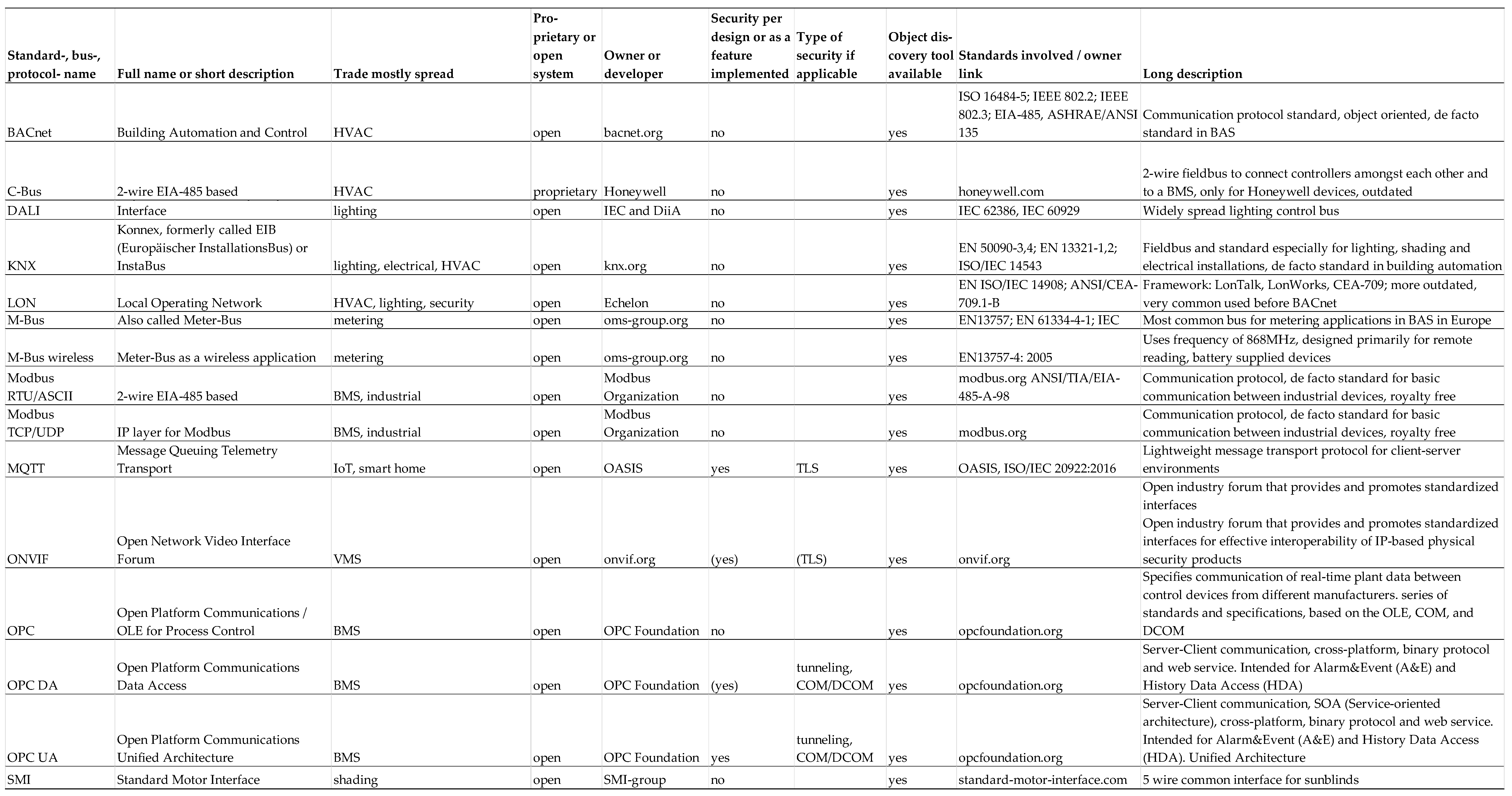

4.3. Categorization of Fieldbus Systems, Protocols and Standards in BAS with Regard to Security

In the context of ICT, Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) and Distributed Control System (DCS), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) created an overview of all the corresponding threats and vulnerabilities and provides guidelines to mitigate the associated risks [

40]. There is a comprehensive survey of Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) protocols [

35], which is also applicable to some parts of the building automation. However, their focus was on IIoT and thus many protocols used in building automation were not investigated. This gap was closed by analyzing 108 protocols and fieldbus systems used in BAS and their implementation of security mechanisms.

Figure 7 shows that only 19 of the 108 protocols and fieldbus systems analyzed have implemented security by design and 11 of them have the option of selecting a security mechanism.

Furthermore, the potential penetration path via discovery tools has not yet been considered in the literature.

Table 1 shows that 15 of the 108 bus systems analyzed enable automatic detection of all bus devices and usually also their entire objects, including the control and regulation parameters. This means that, for BACnet as an example, the ‘Who-Has’ service can be used to determine where certain devices or objects are located without having to know the exact addresses of all devices in the network. Together with the ‘Who-Is’ command, the ‘Who-Has’ service helps to determine the network addresses and object IDs of objects that are located in other BACnet devices. Most protocols also utilize the option of transporting their messages via TCP/IP packets. In practice, this leads to cases where smart sensors in unprotected areas are connected via two-wire bus systems and then connected directly to the OT via gateways using TCP/IP. In addition, they are often also connected directly to the organization’s IT network, as described in “2.2.1 Example 1, composite vulnerabilities” and shown in

Figure 2.

4.4. Literature Around Composite Vulnerabilities in Relation with CPS, ICT and BAS

Considering BAS as a ‘system of systems’ with the many connections within the layers and also among each other and between the various trades, new vulnerabilities can arise that are ignored or do not occur in the individual consideration. This perspective was taken up by Ciholas et al. [

20] in the higher-level context of CPS’s. They refer to the resulting system vulnerabilities as ‘composite vulnerabilities’ and also point out that e.g. NIST, CPNI (Centre for Protection of National Infrastructure) or similar organizations have not yet taken up this topic or only focus on individual vulnerabilities in their publications or use IDS to focus on attacks that are already in progress. New vulnerabilities that can result from the aggregation of different systems or individual vulnerabilities were named as ‘emergent vulnerabilities’ [

41]. They try to counteract this complexity of systems from different points of view, e.g. by considering the adversary goals, existing cyber and threat databases or attack-centric analysis. In the area of information systems, Qu et al. [

42] mention that there is no way to objectively measure composite vulnerabilities. Besides their general observation that there are currently no established systems for measuring interrelated vulnerabilities in information systems, they point out that there are already established methods for measuring individual, independent vulnerabilities such as the CVSS or the NVD. However, in their specific example, they found that CVSS is not able to measure composite vulnerabilities.

Also in the context of composite vulnerabilities, but not mentioning the term explicitly, [

29] and [

26] mention the use of smart sensors and actuators that are connected to the automation layer via bus system like KNX, BACnet, LON, etc. They point out that the possibility of local access to these bus systems leads to considerable vulnerabilities at the field layer, especially since smart sensors and actuators are often installed in unsecured areas [

43,

44]. This observation is particularly interesting in conjunction with the study by Pierre et al. [

43], who point to the penetration of threats between the three layers in a BAS during attacks. This can mean that attacks carried out in the often unsecured field layer can lead to the distribution of malware throughout the BAS network. This is in contrast to [

38], who state that local access to field devices only creates local vulnerabilities limited to small parts of the BAS.

4.5. Literature Related to (Hybrid/Asymmetric) Warfare in Connection with CPS, ICT and BAS

Although from different angles, relevant asymmetric challenges have been extensively studied by only the defense [

45,

46] and cyber security research communities [

47]. Asymmetric tactics are an important part of the history of warfare. For example, Miles et al. [

48] emphasize the need to exploit the opponent’s strengths and weaknesses and use them accordingly. It has been established that nations, organizations and individuals have either discovered opportunities to use ICT to benefit from asymmetric weaknesses, or, conversely, are threatened by asymmetric weaknesses. [

49]. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) defines hybrid threats rather general and also includes all asymmetric conflict scenarios, low-intensity threats, cyber-terrorism, organized cyber-crime and others [

19]. Due to relative recency and rapid developments, the building automation community is yet to address this area.

By mentioning the increasing integration level of automation systems, Mahmoud et al. [

18] point out that insecurities of the physical layer are intertwined with the design of the application controller and both must be considered accordingly in the design of the security policy for the entire system. Their reference to the necessity of looking at the whole system was also investigated by [

50] in relation to asymmetric warfare. They found that aggressors who have a massive resource disadvantage will utilize asymmetric techniques to a maximum, whereas their definition of asymmetric techniques is that of achieving the best ‘cost-benefit ratio’. Thus, attackers only have to look for the weakest point in the entire system, which often leads to even the most experienced defenders not being able to correctly assess the situation in the attack scenario. In the context of CPS, this topic was taken up by [

51]. Their work is based on the analysis of a Denial of Service (DOS) attack on the CPS where they try to formulate the behavior of attacker and defender as well as possible mathematically in order to be able to carry out a corresponding simulation. They also showed that the scientific community has become increasingly interested in the diversity of securing CPS in recent years.

4.6. Literature Related to Asymmetrical Weaknesses in Connection with CPS, ICT and BAS

In recent years the term ‘asymmetrical- weaknesses, threats or vulnerabilities’, also called ‘hybrid threats’ in the context of CPS and ICT came into play [

52,

53]. Asymmetry is also cited in relation to the information asymmetry between the attacker and the defender, mostly in reports aiming general IT security issues [

54,

55]. A start was made on taxonomizing the concept of asymmetry in a literature review, not in relation to CPS or ICT, but with a focus on security and privacy in networks [

56]. With regard to CPS, there is already a good approach to identifying system weaknesses using STRIDE (Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of Service, Elevation of privilege) and evaluating the associated risk using DREAD (Damage, Reproducibility, Exploitability, Affected users, Discoverability) [

57]. Potential system interdependencies and asymmetric threats were also taken into consideration. However, the approach is theoretical and no real-world scenarios are explicitly cited or analyzed. Furthermore, no study was found that linked the issue of asymmetric or hybrid threats and BAS.

Considering BAS and its limited resources in field devices like memory, computing capacity, power restrictions, etc. [

21], it is currently not possible to implement sophisticated, up-to-date security mechanisms [

58]. This brings in another factor of asymmetry, namely the difference between the different layers in building automation, which can also be considered as asymmetry [

52]. This is broadly in line with [

43,

44,

59], who note that field devices are often located in unsecured areas, leading to further asymmetry in terms of the attack surface of a BAS. This also means that the sum of possible, physical entry points for BAS devices in unsecured areas is higher than for devices in secured areas. Thus, possible perpetrators have several possible points of attack which the perpetrator can access the BAS behind the device, or even multiple systems if BAS is connected to them [

60,

61]. In addition, modern fieldbus systems are usually also available at IP level [

62], which transfers the vulnerabilities from the field layer up to the IP layer, or even the enterprise network [

63], if this is not appropriately secured by firewalls or gateways.

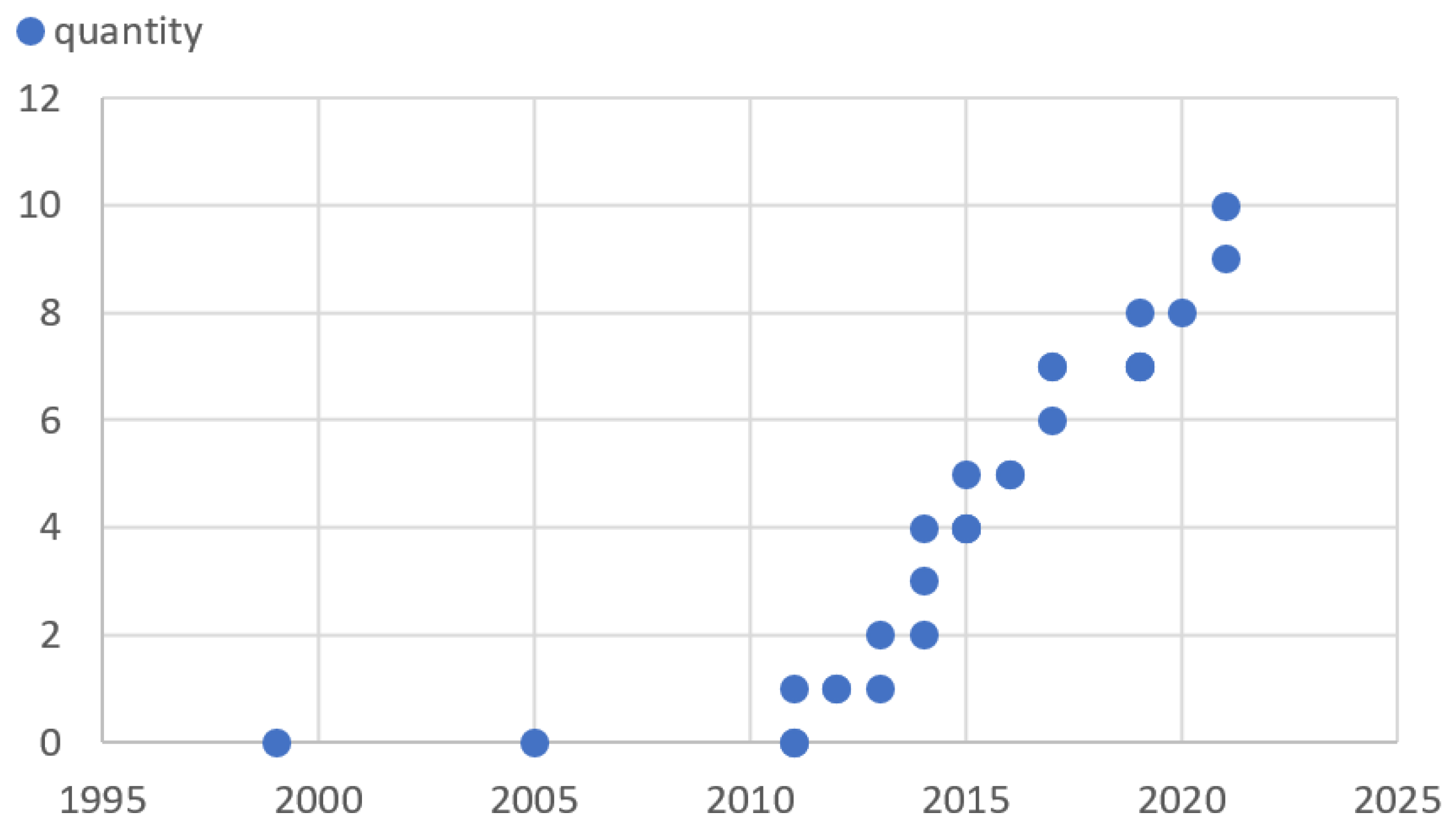

4.7. Intrusion Detection Systems in CPS

It is also apparent that there is a clear trend towards the use of behavioral models for cyber-physical processes to detect intruders for cyber-attacks.

Figure 8 shows, that starting from 2011, the idea of for monitoring the system behavior of the entire physical process has already been thought of more than ten years ago [

64]. Whereas in the first reports it was still assumed that the attackers have access to the configuration system, which might not cover too many attack scenarios. Shortly afterwards, around 2013, references were already made to industry-standard machine learners for attack detection in ICT applications, which thus maps a function of an IDS [

65].

Intrusion detection systems are usually classified into three types. Signature-based, which detect based on documented behavior, anomaly-based, which detect based on machine learning including history data analyses. And hybrid, which is a combination of signature- and anomaly-based [

66]. Most of the current IDSs which have their origin in the IT sector focus on the behavior of network traffic, which is not sufficient for a reliable detection of all attack vectors in a CPS [

67,

68]. This is also supported by Zhang et al. [

66], who add that there are still too few studies on the subject of cyber security in relation to process data. Considering the building automation area, the literature review has shown that there is no literature on the topic of behavioral analysis for anomaly detection, threat prevention or intrusion detection. Implementing behavioral model analyses for the use as IDS has a lot of advantages. Especially in CPSs, the thought of implementing security comes afterthought. This is often due to the fact that safety requirements are mutually exclusive to functional requirements [

69]. In addition, cost constraints often preclude the implementation of security by design in the early stages of CPS planning. At this point the usage of a behavior model based IDS can be a later workaround if security was not implemented by design. The use of a digital twin in BAS as an IDS would be an interesting research work, as the digital twin delivers situational awareness of the whole CPS or BAS. If there is already a digital twin available in a BAS, e.g. for energy consumption modelling or predictive maintenance, the same model can be used as a base for an IDS. Dedicated literature in this topic was not found in this review.

Table 2 provides an overview of existing research into behavioral models in the context of BAS.

With regard to security monitoring in BAS, for example, [

22] suggest using dedicated devices in addition to the control equipment already implemented, which would then detect anomalies and potential attacks. This is in contrast to most proposed solutions in IDS, which are based on behavioral model analysis and would also not be feasible to implement in BAS. As limited memory, computing capacity and power restrictions of the devices at the field and automation layer would not be sufficient for this purpose [

21,

58]. In addition to the limitations mentioned above, there are also other challenges for behavioral models in building automation, e.g. the limited bandwidth of fieldbus systems, their high latency and their highly variable network traffic due to many loosely coupled devices. This is also partially confirmed by Jefrey et al. [

24], whereby they point out that further research is necessary in the area of more complex learning models in large and heterogeneous systems in order to achieve better recognition accuracy.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Asymmetric attacks and hybrid warfare are well understood in the military domain because there have been studies for decades. In comparison, the IT revolution is still very young and ongoing. Therefore, from a scientific point of view, the taxonomy of cyber vulnerabilities is still immature and the process of categorization is not yet complete. In addition to the security vulnerabilities in the cyber domain, buildings also have potential vulnerabilities in the physical domain that are intertwined with those in the cyber domain. Furthermore, when considering an integrated system such as the BAS, it is imperative to acknowledge the significance of the social and organizational perspectives that it encompasses.

This review has shown that existing literature focuses predominantly on cyber, physical, or organizational vulnerabilities in isolation. The consideration of the entire CPS as a ‘system of systems’ with respect to security has been neglected to date. Specifically for building automation, as a subset of CPS, no literature was discovered. Considering the totality of a BAS, their many different trades and their ever-increasing interconnectivity, the question arises as to what new vulnerabilities, which have not yet been investigated in the literature, could result from the combination of individual vulnerabilities. It is recommended that future research place greater emphasis on real-world scenarios, with a view to enhancing the robustness and reliability of behavior models. In the context of hybrid threats, particular attention must be directed towards unprotected sensor technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D.; methodology, K.D.; validation, M.G.; formal analysis, M.G.; investigation, M.G.; resources, M.G.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, K.D.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, K.D.; project administration, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

This research was conducted without financial support or other commercial relationships that could represent a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACS |

Access Control System |

| AHU |

Air Handling Unit |

| ASHRAE |

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| BAS |

Building Automation System |

| CPNI |

Centre for Protection of National Infrastructure |

| CPS |

Cyber Physical System |

| CVSS |

Common Vulnerability Scoring System |

| DCS |

Distributed Control System |

| DDC |

Direct Digital Control |

| DOS |

Denial of Service |

| DREAD |

Damage, Reproducibility, Exploitability, Affected users, Discoverability |

| EPBD |

Energy Performance of Buildings Directive |

| FTA |

Fault Tree Analysis |

| GPDR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| HAZOP |

Hazard and Operability Analysis |

| HVAC |

Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning |

| IB |

Intelligent Buildings |

| ICS |

Industrial Control System |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technology |

| IDS |

Intrusion Detection System |

| IIoT |

Industrial Internet of Things |

| IMECA |

Intervention Mode Effects and Criticality Analysis |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IT |

Information Technology |

| NATO |

North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

| NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NVD |

National Vulnerability Database |

| ODBC |

Open Database Connectivity |

| OT |

Operational Technology |

| RBD |

Reliability Block Diagram |

| SB |

Smart Buildings |

| SCADA |

Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SQL |

Structured Query Language |

| STRIDE |

Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of Service, Elevation of privilege |

| TCP/IP |

Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol |

| VMS |

Video Management System |

References

- Fan, C.; Xiao, F.; Yan, C. A framework for knowledge discovery in massive building automation data and its application in building diagnostics. Autom. Constr. 2015, 50, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Bakakeu, F. J. Bakakeu, F. Schäfer, J. Bauer, M. Michl, and J. Franke, “Building Cyber-Physical Systems - A Smart Building Use Case,” in Smart Cities, 2017, pp. 605-639.

- Schmidt, M.; Åhlund, C. Smart buildings as Cyber-Physical Systems: Data-driven predictive control strategies for energy efficiency. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Perry, “Smart Buildings: A Deeper Dive into Market Segments,” American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, https://www.aceee.org/, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.aceee. 1703.

- Wong, J.; Li, H.; Wang, S. Intelligent building research: a review. Autom. Constr. 2005, 14, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delsing, J. Smart City Solution Engineering. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Z. Tragos et al., “An IoT based intelligent building management system for ambient assisted living,” presented at the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Communication Workshop (ICCW), 2015.

- Nge, C.L.; Ranaweera, I.U.; Midtgård, O.-M.; Norum, L. A real-time energy management system for smart grid integrated photovoltaic generation with battery storage. Renew. Energy 2019, 130, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marksteiner, S.; Jimenez, V.J.E.; Valiant, H.; Zeiner, H. An overview of wireless IoT protocol security in the smart home domain. 2017 Internet of Things - Business Models, Users, and Networks. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, DenmarkDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–8.

- R. Khan, K. R. Khan, K. McLaughlin, D. Laverty, and S. Sezer, “STRIDE-based threat modeling for cyber-physical systems,” presented at the 2017 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), 2017.

- Aghemo, C.; Virgone, J.; Fracastoro, G.; Pellegrino, A.; Blaso, L.; Savoyat, J.; Johannes, K. Management and monitoring of public buildings through ICT based systems: Control rules for energy saving with lighting and HVAC services. Front. Arch. Res. 2013, 2, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. (2016). DIRECTIVE (EU) 2018_844 of amending Directive 2010_31_EU on the energy performance of buildings and Directive 2012_27_EU on energy efficiency. 30 May.

- Kastner, W.; Neugschwandtner, G.; Soucek, S.; Newman, H.M. Communication systems for building automation and control. Proc. IEEE 2005, 93, 1178–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammadi, A. A. Hebsi, M. J. Zemerly, and J. W. P. Ng,” presented at the 2012 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conferences on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology, 2012., “Indoor Localization and Guidance Using Portable Smartphones.

- Kiliccote, S.; Piette, M.A.; Ghatikar, G.; Hafemeister, D.; Kammen, D.; Levi, B.G.; Schwartz, P. Smart Buildings and Demand Response. PHYSICS OF SUSTAINABLE ENERGY II: USING ENERGY EFFICIENTLY AND PRODUCING IT RENEWABLY. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 328–338.

- ASHRAE, “Information Model Standard for Integrating Facilities with Smart Grid,” (in english), ASHRAE Journal, vol. BACnet Today & the Smart Grid, p. 5, 2011. [Online]. Available: https://www.ashrae.org/File%20Library/Technical%20Resources/Bookstore/Information-Model-Standard.pdf.

- Zhukabayeva, T.; Zholshiyeva, L.; Karabayev, N.; Khan, S.; Alnazzawi, N. Cybersecurity Solutions for Industrial Internet of Things–Edge Computing Integration: Challenges, Threats, and Future Directions. Sensors 2025, 25, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. S. Mahmoud and Y. Xia, “Cyberphysical Security Methods,” in Networked Control Systems, 2019, pp. 389-456.

- S.-D. O. V. Bachmann and H. D: Gunneriusson, “Terrorism and Cyber Attacks as Hybrid Threats, 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Ciholas and J. M. Such, “Composite vulnerabilities in Cyber Physical Systems,” in “Security and Resilience of Cyber- -Physical Infrastructures,” Security Lancaster, eprints.lancs.ac.uk, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/79052/4/Proceedings_serecin_2016.

- H. Merz, T. H. Merz, T. Hansemann, and C. Hübner, Gebäudeautomation Kommunikationssysteme mit EIB/KNX, LON und BACnet. Fachbuchverlag Leipzig (in german), 2016.

- Graveto, V.; Cruz, T.; Simöes, P. Security of Building Automation and Control Systems: Survey and future research directions. Comput. Secur. 2022, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, D.; Andrade, E.; Rativa, D.; Maciel, A.M.A. Fault Detection and Diagnosis in Industry 4.0: A Review on Challenges and Opportunities. Sensors 2024, 25, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, N.; Tan, Q.; Villar, J.R. Using Ensemble Learning for Anomaly Detection in Cyber–Physical Systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA. Available online: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- T. Mundt and P. Wickboldt, “Security in building automation systems - a first analysis,” presented at the 2016 International Conference On Cyber Security And Protection Of Digital Services (Cyber Security), 2016.

- Harzing, A.-W.; Alakangas, S. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: A longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coole, M.; Evans, D.; Brooks, D. A Framework for the Analysis of Security Technology Vulnerabilities: Defeat Evaluation of an Electronic Access Control Locking System. 2022 IEEE International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology (ICCST). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, Czech RepublicDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Granzer, W.; Praus, F.; Kastner, W. Security in Building Automation Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 57, 3622–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common Weakness Enumeration. Common Weakness Enumeration [Online] Available: http://cwe.mitre.org/data/index.

- NIST-resilience-research. “resilience research.” NIST. https://www.nist.gov/resilience (accessed 9.9.2022, 2022).

- Kshetri, N. Information and communications technologies, strategic asymmetry and national security. J. Int. Manag. 2005, 11, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Meyer, J. D. Meyer, J. Haase, M. Eckert, and B. Klauer, “New attack vectors for building automation and IoT,” presented at the IECON 2017 - 43rd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, 2017.

- S. A. Kumar, T. S. A. Kumar, T. Vealey, and H. Srivastava, “Security in Internet of Things: Challenges, Solutions and Future Directions,” presented at the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), 2016.

- Figueroa-Lorenzo, S.; Añorga, J.; Arrizabalaga, S. A Survey of IIoT Protocols. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- first.org. “Common Vulnerability Scoring System SIG.” first.org. https://www.first.org/cvss/ (accessed 4.10.2023.

- NIST. “National Vulnerability Database (NVD).” NIST. https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/national-vulnerability-database-nvd (accessed 4.10.2023.

- D. J. Brooks, M. D. J. Brooks, M. Coole, P. Haskell-Dowland, M. Griffiths, and N.

- Security Industry Association. Mmm.

- Building Owners and Managers Association, securityindustry.org, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.securityindustry.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/BACS-Report_Final-Intelligent-Building-Management-Systems.

- R. J. Thomas and T. Chothia, “Learning from Vulnerabilities - Categorising, Understanding and Detecting Weaknesses in Industrial Control Systems,” in Computer Security, (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2020, ch. Chapter 7, pp. 100-116.

- K. Stouffer, V. K. Stouffer, V. Pillitteri, S. Lightman, M. Abrams, and A. Hahn, “Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security,” NIST, Ed., ed. https://www.nist.gov/: National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2015.

- D. K. Wittenberg, J. D. K. Wittenberg, J. Smith, R. Gray, and G. Eakman, “Automotive Vulnerability Detection System,” 2015. [Online]. Available: https://www.cs.brandeis.edu/~dkw/papers/ESCARVDS4.pdf.

- Qu, Y.; English, A.; Hannon, B. Quantifying the Impact of Vulnerabilities of the Components of an Information System towards the Composite Rise Exposure. 2021 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 788–793.

- C. Pierre, L. C. Pierre, L. Aidan, S. Parvin, and S. J. M., “The Security of Smart Buildings: a Systematic Literature Review,” (in english), Computer Science > Cryptography and Security, vol. 2019; 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Ly and Y. Jin, “Security Challenges in CPS and IoT: From End-Node to the System,” presented at the 2016 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), 2016.

- M. Montgomery C., “Unorthodox Thoughts about Asymmetric Warfare,” OMB No. 0704-0188, 2003. [Online]. Available: https://apps.dtic. 4856.

- Lele, “Asymmetric Warfare: A State vs Non-State Conflict,” (in english), Universidad Externado de Colombia, vol. OASIS 20, Research Fellow at Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, p. 15, 2015. [Online]. Available: https://revistas.uexternado.edu.co/index.php/oasis/article/view/4011.

- Chen, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Dispersing Asymmetric DDoS Attacks with SplitStack,” presented at the Proceedings of the 15th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks, 2016.

- F. B. Miles, “Asymmetric Warfare: An Historical Perspective,” U.S. Army War College, 1999. [Online]. Available: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA363836.

- N. Kshetri, “Information and Communications Technologies, Cyberattacks, and Strategic Asymmetry,” in The Global Cybercrime Industry, 2010, ch. Chapter 6, pp. 119-137.

- G. Pernin, Arroyo Center., and United States. Army., Lessons from the Army’s Future Combat Systems program. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, ARROYO CENTER, 2012, pp. xlii, 330 pages.

- Gupta, A.; Langbort, C.; Basar, T. Dynamic Games With Asymmetric Information and Resource Constrained Players With Applications to Security of Cyberphysical Systems. IEEE Trans. Control. Netw. Syst. 2016, 4, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoom, I.; Abolhasan, M.; Lipman, J.; Liu, R.P.; Ni, W. Anatomy of Threats to the Internet of Things. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2018, 21, 1636–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Jajodia, G. S. Jajodia, G. Cybenko, P. Liu, C. Wang, and M. Wellman, Adversarial and Uncertain Reasoning for Adaptive Cyber Defense (Lecture Notes in Computer Science). 2019.

- G. Cybenko, M. G. Cybenko, M. Wellman, P. Liu, and M. Zhu, “Overview of Control and Game Theory in Adaptive Cyber Defenses,” in Adversarial and Uncertain Reasoning for Adaptive Cyber Defense, (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2019, ch. Chapter 1, pp. 1-11.

- M. G. Jones, “Asymmetric information games and cyber security,”. PhD Dissertation, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Giorgia Tech Library, 2013.

- Pawlick, J.; Colbert, E.; Zhu, Q. A Game-theoretic Taxonomy and Survey of Defensive Deception for Cybersecurity and Privacy. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Z.A.; Singh, Y. A Hybrid Threat Assessment Model for Security of Cyber Physical Systems. 2022 Seventh International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Grid Computing (PDGC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 582–587.

- Liu, Y.; Pang, Z.; Dan, G.; Lan, D.; Gong, S. A Taxonomy for the Security Assessment of IP-Based Building Automation Systems: The Case of Thread. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2018, 14, 4113–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. T. Siebel, “Securing IT Networks for Industrial and Building Automation Systems,” (in English), International Journal of Trend in Research and Development, pp. 134-136, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.htw-berlin.de/forschung/online-forschungskatalog/publikationen/publikation/?eid=11379.

- Younus, M.U.; Islam, S.U.; Ali, I.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.K. A survey on software defined networking enabled smart buildings: Architecture, challenges and use cases. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 137, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzin, F. Golatowski, and D. Timmermann, ” presented at the IECON 2017 - 43rd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, 2017., “A survey on information modeling and ontologies in building automation.

- Soucek, S.; Zucker, G. Current developments and challenges in building automation. e i Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik 2012, 129, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Tenkanen and T. Hamalainen, “Security Assessment of a Distributed, Modbus-Based Building Automation System,” presented at the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (CIT), 2017.

- Liu, Y.; Ning, P.; Reiter, M.K. False data injection attacks against state estimation in electric power grids. In Proceedings of the 16th of ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Chicago, IL, USA, 9–13 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- J. M. Beaver, R. C. J. M. Beaver, R. C. Borges-Hink, and M. A. Buckner, “An Evaluation of Machine Learning Methods to Detect Malicious SCADA Communications,” presented at the 2013 12th International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications, 2013.

- Zhang, F.; Kodituwakku, H.A.D.E.; Hines, J.W.; Coble, J.B. Multilayer Data-Driven Cyber-Attack Detection System for Industrial Control Systems Based on Network, System, and Process Data. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2019, 15, 4362–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Goh, S. J. Goh, S. Adepu, M. Tan, and Z. S. Lee, “Anomaly Detection in Cyber Physical Systems Using Recurrent Neural Networks,” presented at the 2017 IEEE 18th International Symposium on High Assurance Systems Engineering (HASE), 2017.

- Gawand, H.L.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Roy, K. Securing a Cyber Physical System in Nuclear Power Plants Using Least Square Approximation and Computational Geometric Approach. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2017, 49, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Á. J. Varela-Vaca, D. G. Rosado, L. E. Sánchez, M. T. Gómez-López, R. M. Gasca, and E. Fernández-Medina, “Definition and Verification of Security Configurations of Cyber-Physical Systems,” in Computer Security, (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2020, ch. Chapter 9, pp. 135-155.

- Abdulmunem, A.-S.M.Q.; Kharchenko, V.S. Availability and Security Assessment of Smart Building Automation Systems: Combining of Attack Tree Analysis and Markov Models. 2016 Third International Conference on Mathematics and Computers in Sciences and in Industry (MCSI). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, GreeceDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 302–307.

- A.-S. M. K. Abdulmunem and V. K. Akhmed Valid Al-Khafadzhi, “The method of IMECA-based security assessment: case study for building automation system,” (in english), Ivan Kozhedub Kharkiv National Air Force University (KNAFU), vol. Vol. 1, 1(138)’2016 pp. 138-144, 2016. [Online]. Available: http://www.hups.mil.gov.ua/periodic-app/article/15263. National Aerospace University “KhAI”, Kharkiv.

- Jones, C.B.; Carter, C.; Thomas, Z. Intrusion Detection & Response using an Unsupervised Artificial Neural Network on a Single Board Computer for Building Control Resilience. 2018 Resilience Week (RWS). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 31–37.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).