Submitted:

06 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

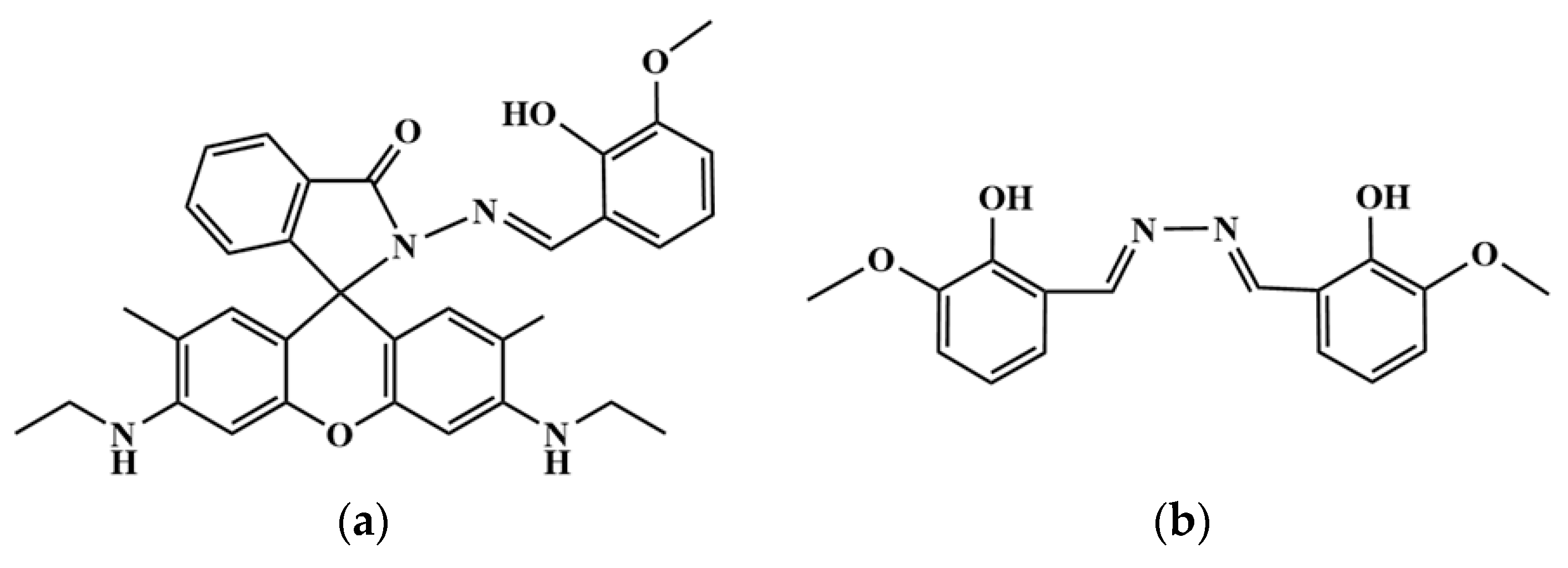

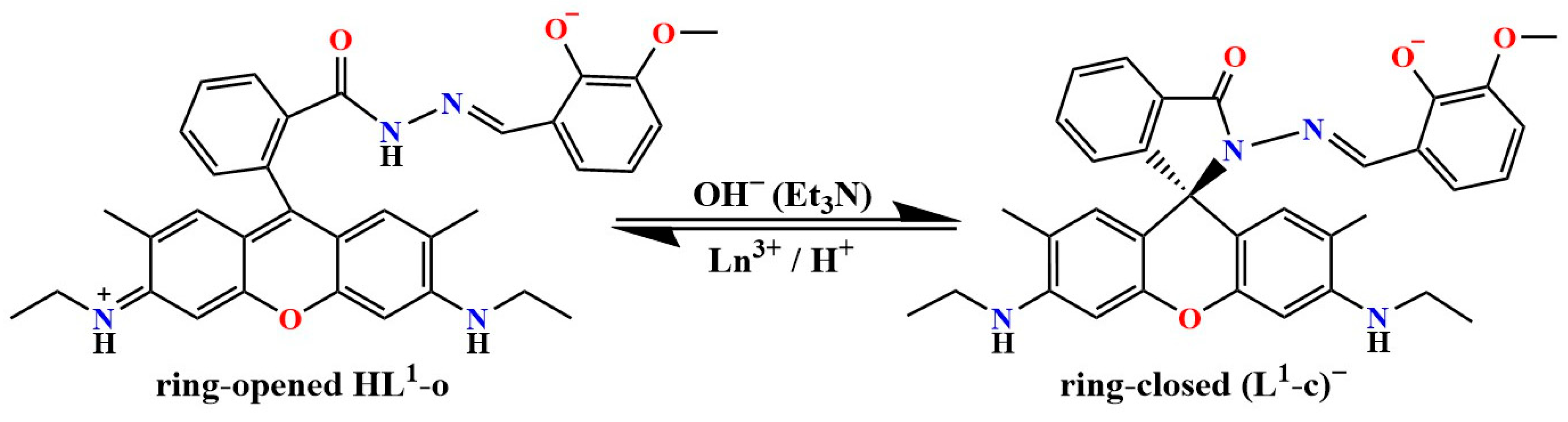

2.1. Synthesis

2.1.1. Synthesis of [Dy(HL1-o)(NO3)2(CH3OH)2]NO3·CH3OH (Complex 1)

2.1.2. Synthesis of [Dy4(L1-c)2(L2)2(μ3-OH)2(NO3)2(CH3OH)4](NO3)2·2CH3CN·5CH3OH·2H2O (Complex 2)

2.1.3. Synthesis of [Gd4(L1-c)2(L2)2(μ3-OH)2(NO3)2(CH3OH)4](NO3)2·2CH3CN·5CH3OH·2H2O (Complex 3)

2.2. Physical Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

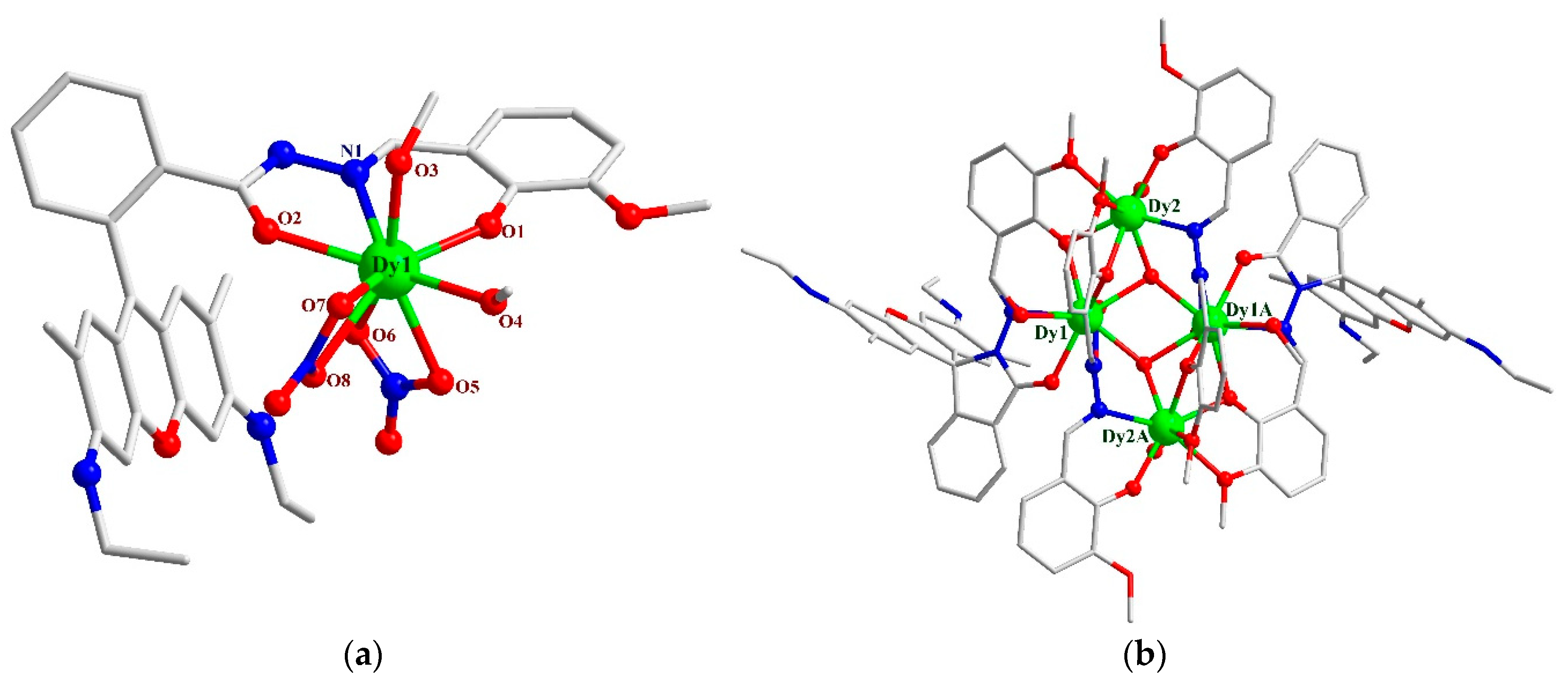

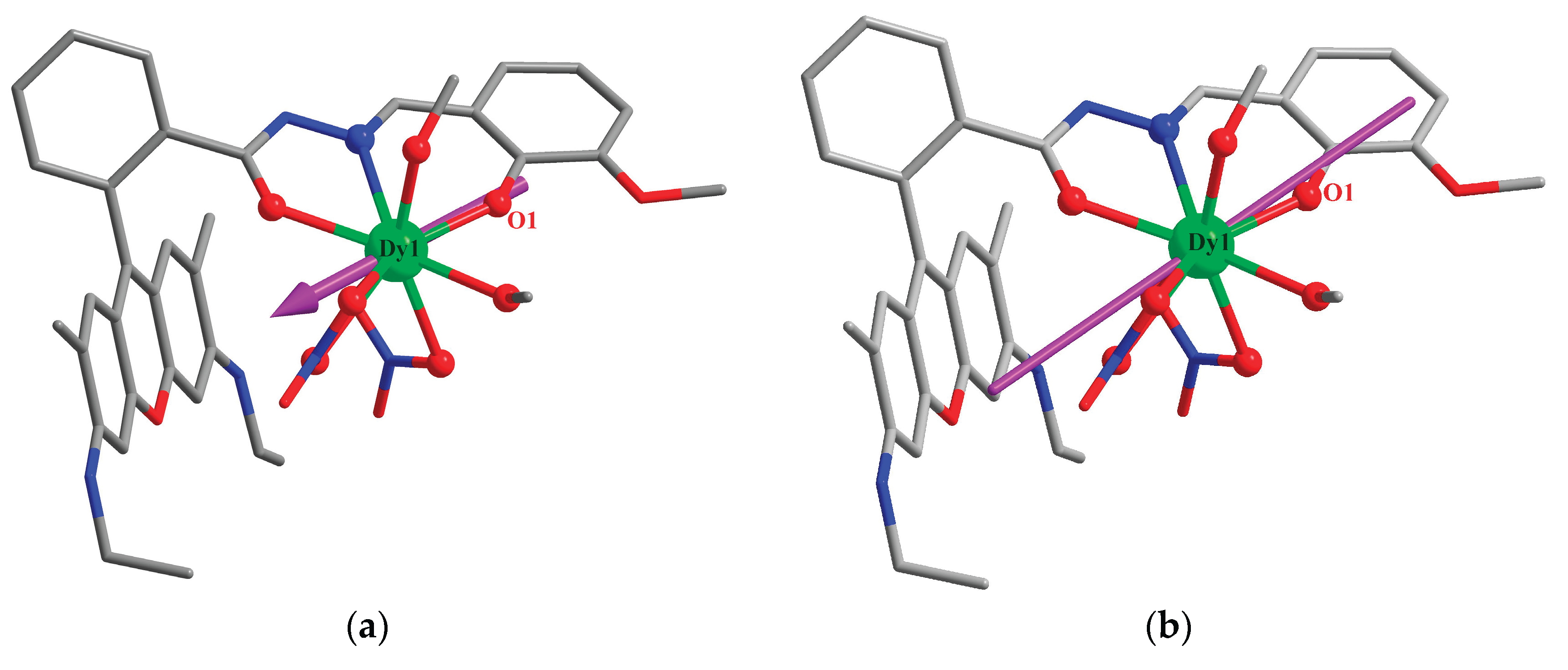

3.1. Crystal Structures

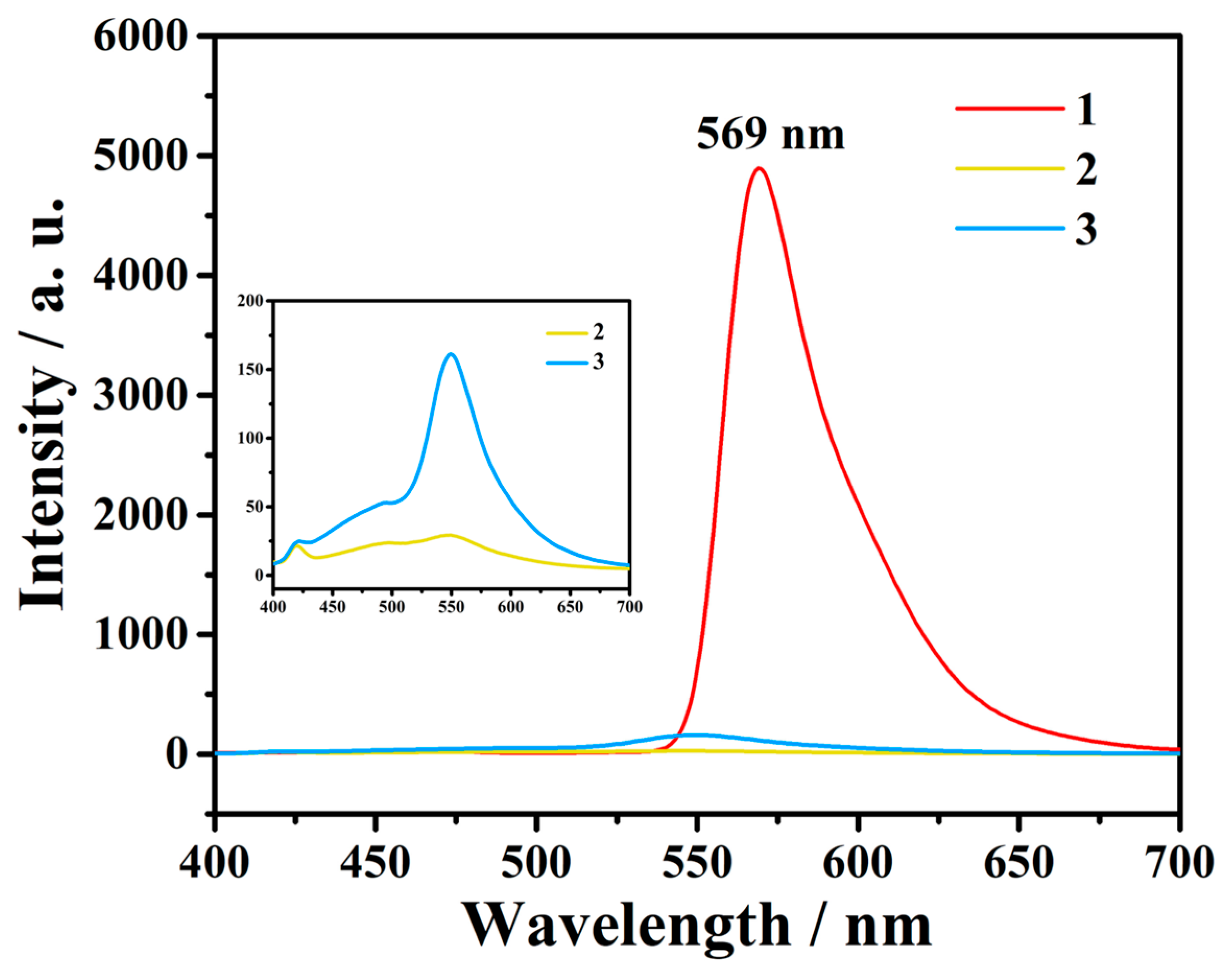

3.2. Characterizations

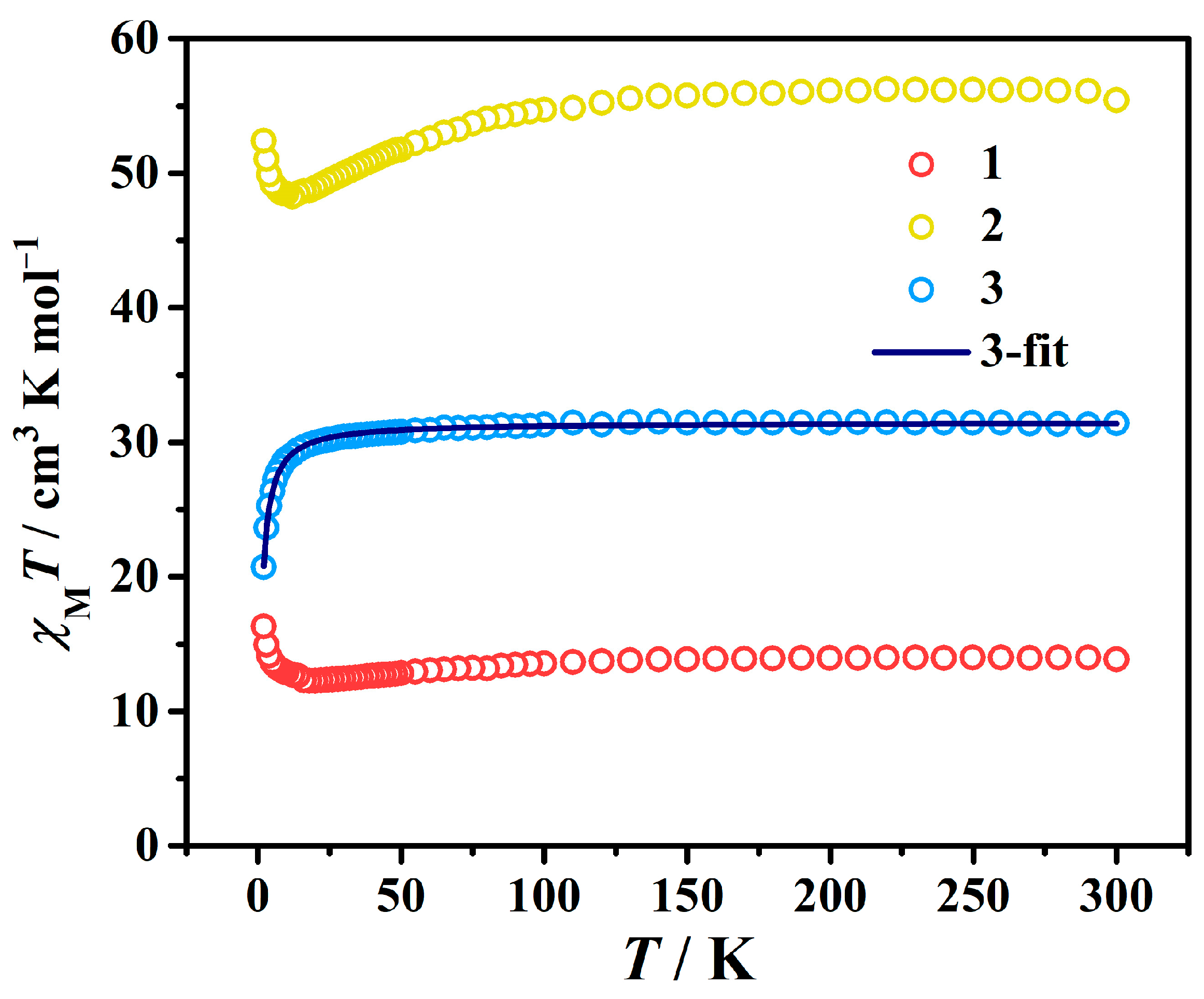

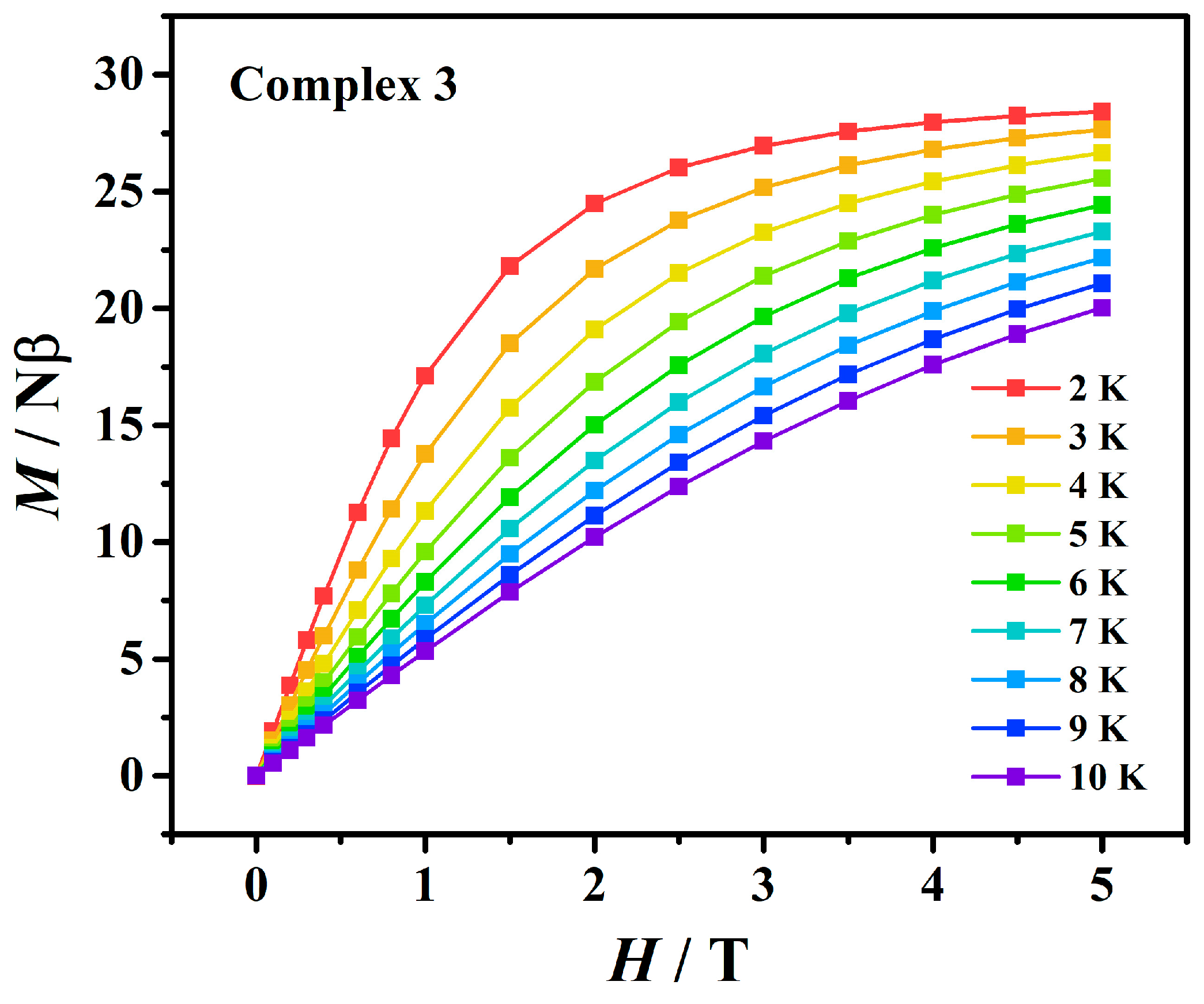

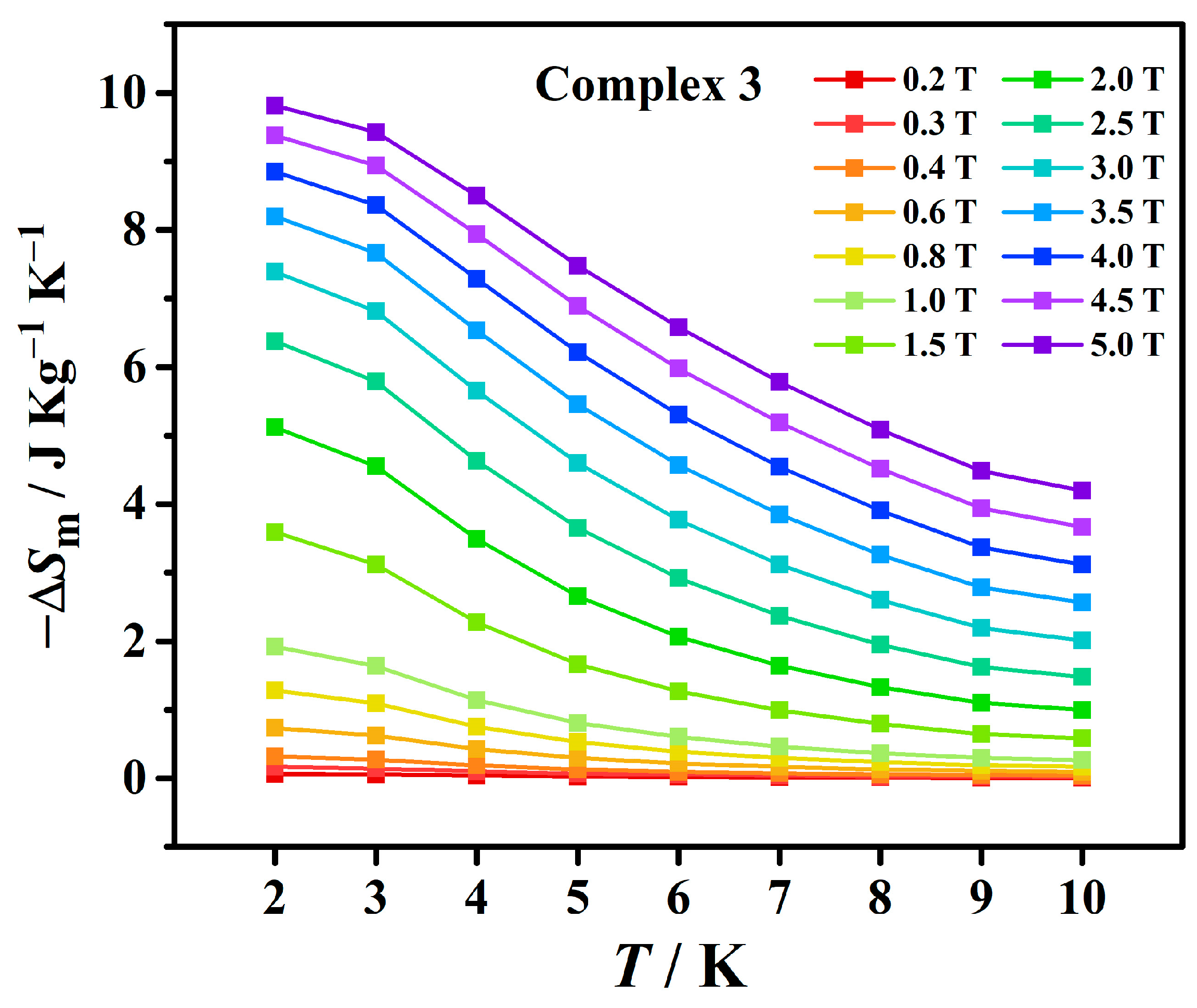

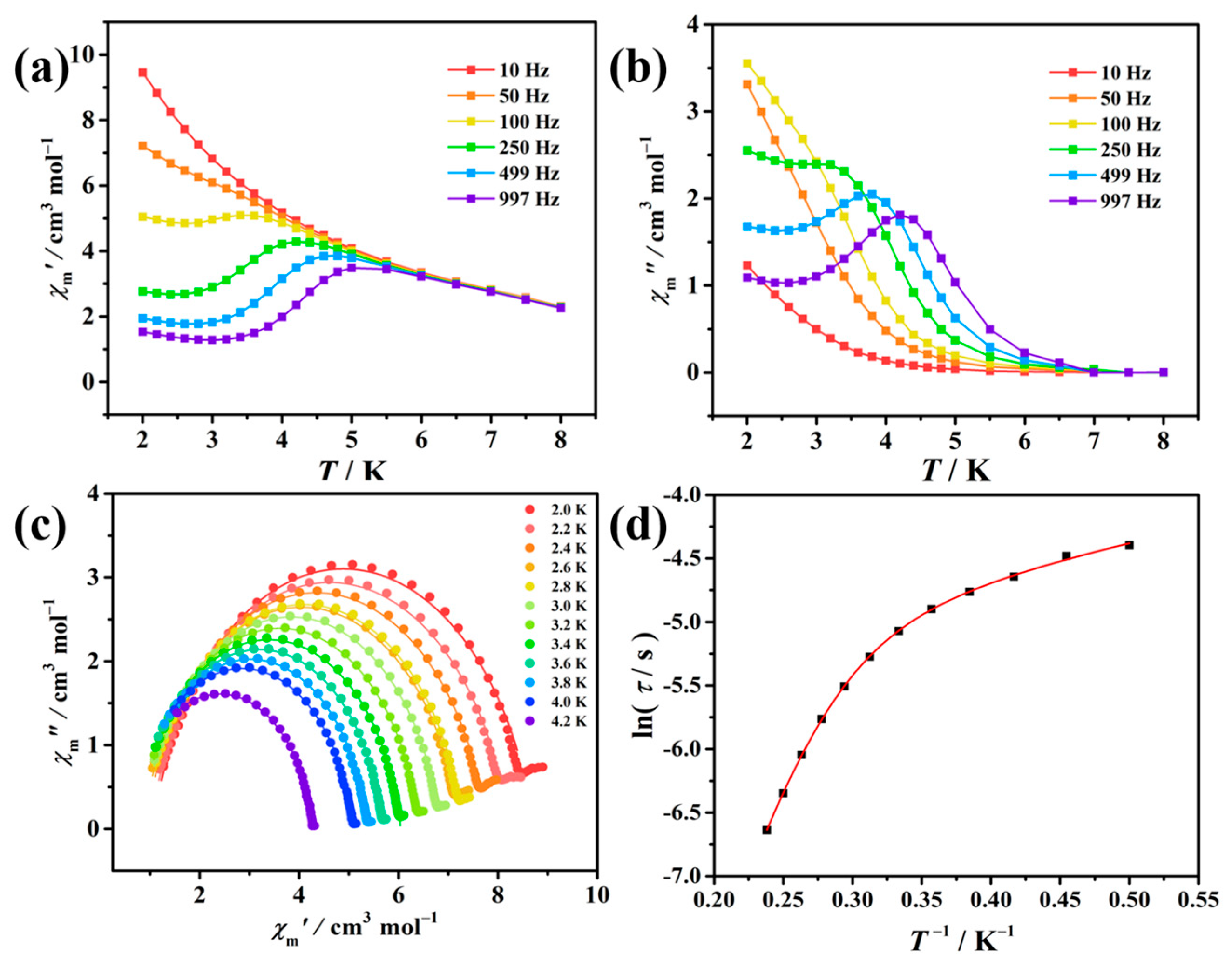

3.3. Magnetic Measurements

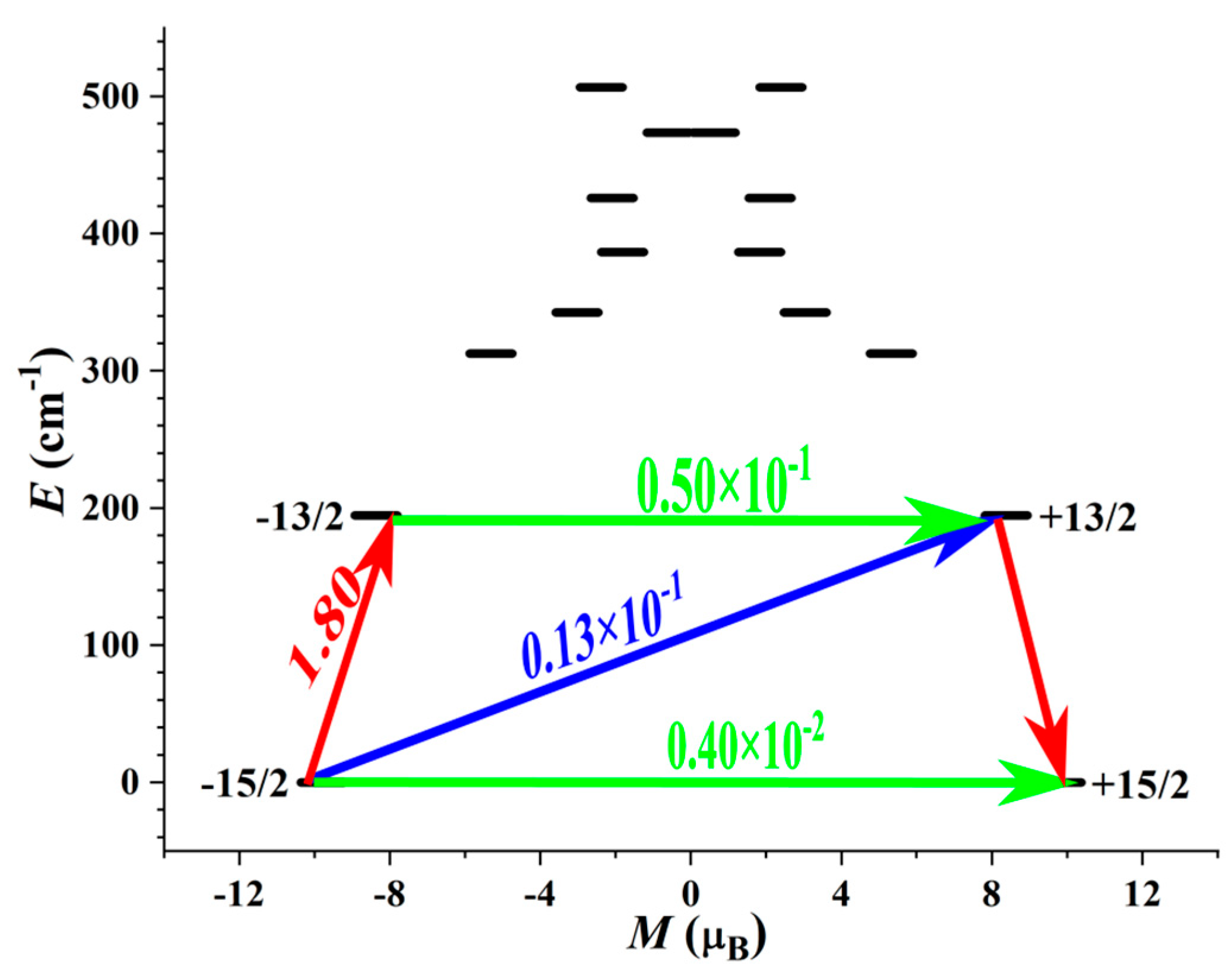

3.4. Theoretical Calculations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMMs | Single-molecule magnets |

| PXRD | Powder X-ray diffraction |

| LLCT | Ligand-to-ligand charge transfer |

| DC | Direct current |

| AC | Alternating current |

| MCE | Magnetocaloric effect |

| χ"M | Out-of-phase AC susceptibilities |

| QTM | Quantum tunneling of the magnetization |

| CASSCF | Complete-active-space self-consistent field |

| KDs | Kramers doublets |

| TA-QTMs | Thermal-assisted QTMs |

| CF | Crystal-field |

References

- Caneschi, A.; Gatteschi, D.; et al. Alternating current susceptibility, high field magnetization, and millimeter band EPR evidence for a ground S = 10 state in [Mn12O12(CH3COO)16(H2O)4]·2CH3COOH·4H2O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 5873–5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessoli, R.; Gatteschi, D.; Caneschi, A.; Novak, M. A. , Magnetic bistability in a metal-ion cluster. Nature 1993, 365, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, S. M. J.; Wemple, M. W.; Adams, D. M.; Tsai, H.-L.; Christou, G.; Hendrickson, D. N. , Distorted MnIVMnIII3 Cubane Complexes as Single-Molecule Magnets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7746–7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.-R.; Sarachik, M.-P. Macroscopic Measurement of Resonant Magnetization Tunneling in High-Spin Molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 76, 3830–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuenberger M., N.; Loss D. J., N. Quantum computing in molecular magnets. Nature 2001, 410, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, L.; Benelli, C.; Gatteschi, D. Lanthanides in Molecular Magnetism: Old Tools in a New Field. Chem. Soc. Rev, 2011, 40, 3092–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiani, F.; Affronte, M. Molecular Spins for Quantum Information Technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2011, 40, 3119–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Q.-W.; Wu, S.-G.; Chen, Y.-C.; Wan, R.-C.; Huang, G.-Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.-L.; Reta, D.; Giansiracusa, M.; Wang, Z.-X.; Chilton, N.; Tong, M.-L. Opening Magnetic Hysteresis by Axial Ferromagnetic Coupling: From Mono-Decker to Double-Decker Metallacrown. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 5299. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.-G.; Ruan, Z.-Y.; Huang, G.-Z.; Zheng, J.-Y.; Vieru, V.; Taran, G.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Liu, J.-L.; Ho, L.; Chibotaru, L.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Chen, X.-M.; Tong, M.-L. Field-induced oscillation of magnetization blocking barrier in a holmium metallacrown single-molecule magnet. Chem 2021, 7, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.-D.; Wang, B.-W.; Sun, H.-L.; Wang, Z.-M.; Gao, S. An Organometallic Single-Ion Magnet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 4730–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C.; Ortu, F.; Reta, D.; Chilton, N.; Mills, D. Molecular magnetic hysteresis at 60 kelvin in dysprosocenium. Nature 2017, 548, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.-S.; Day, B.; Chen, Y.-C.; Tong, M.-L.; Mansikkamäki, A.; Layfield, R. Magnetic hysteresis up to 80 kelvin in a dysprosium metallocene single-molecule magnet. Science 2018, 362, 1400–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, C.; McClain, R.; Reta, D.; Kragskow, J.; Marchiori, D.; Lachman, E.; Choi, E.-S.; Analytis, J.; Britt, D.; Chilton, N.; Harvey, N.; Long, J. Ultrahard Magnetism from Mixed-Valence Dilanthanide Complexes with Metal-Metal Bonding. Science 2022, 375, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, T.; Lu, F.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.-Q. Understanding the Magnetic Relaxation Mechanism in Mixed-Valence Dilanthanide Complexes with Metal–Metal Bonding: A Theoretical Investigation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 3088–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojorat, M.; Sabea, H.-A.; Norel, L.; Bernot, K.; Roisnel, T.; Gendron, F.; Guennic, B.; Trzop, E.; Collet, E.; Long, J.; Rigaut, S. Hysteresis Photomodulation via Single-Crystal-to-Single-Crystal Isomerization of a Photochromic Chain of Dysprosium Single Molecule Magnets. J Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bünzli, J.-C. Benefiting from the Unique Properties of Lanthanide Ions, Acc. Chem. Res. 2006, 39, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.-H.; Li, Q.-W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Liu, J.-L.; Tong, M.-L. Luminescent single-molecule magnets based on lanthanides: Design strategies, recent advances and magneto-luminescent studies. Coord. Chem. Rev, 2019, 378, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; Mota, A.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A.; Titos, S.; Herrera, J.; Ruiz, E.; Cremades, E.; Costes, J.; Colacio, E. Field and Dilution Effects on the Slow Relaxation of a Luminescent DyO9 Low-Symmetry Single-Ion Magnet. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7916–7918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Jiang, S.-D.; Wang, B.-W.; Han, J.-B.; Sun, J.-L.; Bian, Z.-Q.; Wang, Z.-M.; Gao, S. Thermostability and Photoluminescence of Dy(Ⅲ) Single-Molecule Magnets Under a Magnetic Field. Chem. Sci., 2016, 7, 5020–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Wu, X.-R.; Liu, C.-M.; Kou, H.-Z. Assembly of a Heterotrimetallic Zn2Dy2Ir Pentanuclear Complex toward Multifunctional Molecular Materials. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 14275–14281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, X.-J.; Meng, X.-X.; Shi, W.; Cheng, P.; Powell, A. Constraining the Coordination Geometries of Lanthanide Centers and Magnetic Building Blocks in Frameworks: a New Strategy for Molecular Nanomagnets. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2423–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Q.; Geng, Y.-. Wei Zhimo Wang, Changjian Xie, Tian Han, Peng Cheng, Two-Dimensional Metal−Organic Framework with HighPerformance Single-Molecule Magnets as Nodes Showing Magnetic Coercivity Photomodulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 21, 18044–18053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Wu, S.-Q.; Liu, M.-J.; Sato, O.; Kou, H.-Z. Rhodamine 6G-Labeled Pyridyl Aroylhydrazone Fe(II) Complex Exhibiting Synergetic Spin Crossover and Fluorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9426–9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, M.-J.; Wu, S.-Q.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, N.; Sato, O.; Kou, H.-Z. , Substituent effects on the fluorescent spin-crossover Fe(II) complexes of rhodamine 6G hydrazones. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-J.; Yuan, J.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-M.; Kou, H.-Z. , Rhodamine Salicylaldehyde Hydrazone Dy(III) Complexes: Fluorescence and Magnetism. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 4061–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-J.; Wu, S.-Q.; Li, J.-X.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Sato, O.; Kou, H.-Z. , Structural Modulation of Fluorescent Rhodamine-Based Dysprosium(III) Single-Molecule Magnets. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 2308–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-J.; Fu, Z.-Y.; Sun, R.; Yuan, J.; Liu, C.-M.; Zou, B.; Wang, B.-W.; Kou, H.-Z. , Mechanochromic and Single-Molecule Magnetic Properties of a Rhodamine 6G Dy(III) Complex. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, M.-J.; Ding, M.-M.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Kou, H.-Z. A Dy(III) Fluorescent Single-Molecule Magnet Based on a Rhodamine 6G Ligand. Inorganics 2021, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, M.-J.; Zeng, M.; Kou, H.-Z. Chiral Zn3Ln3 Hexanuclear Clusters of an Achiral Flexible Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 12814–12821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-N.; Xu, G.-F.; Gamez, P.; Zhao, L.; Lin, S.-Y.; Deng, R.-P.; Tang, J.-K.; Zhang, H.-J. Two-Step Relaxation in a Linear Tetranuclear Dysprosium(III) Aggregate Showing Single-Molecule Magnet Behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8538–8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gschneidner, K. A.; Pecharsky, V. K. Thirty years of near room temperature magnetic cooling: Where we are today and future prospects. Int. J. Refrig. 2008, 31, 945–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelisti, M.; Brechin, E. K. Recipes for enhanced molecular cooling. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 4672–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskelo, E. C.; Liu, C.; Mukherjee, P.; Kelly, N. D.; Dutton, S. E. Free-Spin Dominated Magnetocaloric Effect in Dense Gd3+ Double Perovskites. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 3440–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorusso, G.; Sharples, J. W.; Palacios, E.; Roubeau, O.; Brechin, E. K.; Sessoli, R.; Rossin, A.; Tuna, F.; McInnes, E. J. L.; Collison, D.; Evangelisti, M. A Dense Metal-Organic Framework for Enhanced Magnetic Refrigeration. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 4653–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.-C.; Pan, Y.-Y.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. Magnetocaloric effect and thermal conductivity of Gd(OH)3 and Gd2O(OH)4(H2O)2. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 7317–7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, E.; Rodríguez-Velamazán, J. A.; Evangelisti, M.; McIntyre, G. J.; Lorusso, G.; Visser, D.; de Jongh, L. J.; Boatner, L. A. Magnetic structure and magnetocalorics of GdPO4. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Mater. Phys. 2014, 90, 214423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Qin, L.; Meng, Z.-S.; Yang, D.-F.; Wu, C.; Fu, Z.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Liu, J.-L.; Tarasenko, R.; Orendáč, M.; Prokleška, J.; Sechovský, V.; Tong, M.-L. Study of a magnetic-cooling material Gd(OH)CO3. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 9851–9858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Prokleška, J.; Xu, W.-J.; Liu, J.-L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.-X.; Jia, J.-H.; Sechovský, V.; Tong, M.-L. A brilliant cryogenic magnetic coolant: magnetic and magnetocaloric study of ferromagnetically coupled GdF3. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 12206–12211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q. F.; Liu, B. L.; Ye, M. Y.; Zhuang, G. L.; Long, L. S.; Zheng, L. S. Gd(OH)F2: A Promising Cryogenic Magnetic Refrigerant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 13787–13793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. W.; Gong, P. F.; Guo, R. X.; Fan, F. D.; Shen, J.; Zhang, G. C.; Tu, H. Improvement on Magnetocaloric Effect through Structural Evolution in Gadolinium Borate Halides Ba2Gd(BO3)2X (X = F, Cl). Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 15584–15592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, I. F.; Vacher, M.; Alavi, A.; Angeli, C.; Aquilante, F.; Autschbach, J.; Bao, J. J.; Bokarev, S. I.; Bogdanov, N. A.; Carlson, R. K.; Chibotaru, L. F.; Creutzberg, J.; Dattani, N.; Delcey, M. G.; Dong, S. S.; Dreuw, A.; Freitag, L.; Frutos, L. M.; Gagliardi, L.; Gendron, F.; Giussani, A.; González, L.; Grell, G.; Guo, M. Y.; Hoyer, C. E.; Johansson, M.; Keller, S.; Knecht, S.; Kovacevic, G.; Källman, E.; Manni, G. L.; Lundberg, M.; Ma, Y. J.; Mai, S.; Malhado, J. P.; Malmqvist, P. Å.; Marquetand, P.; Mewes, S. A.; Norell, J.; Olivucci, M.; Oppel, M.; Phung, Q. M.; Pierloot, K.; Plasser, F.; Reiher, M.; Sand, A. M.; Schapiro, I.; Sharma, P.; Stein, C. J.; Sørensen, L. K.; Truhlar, D. G.; Ugandi, M.; Ungur, L.; Valentini, A.; Vancoillie, S.; Veryazov, V.; Weser, O.; Wesołowski, T. A.; Widmark, P.; Wouters, S.; Zech, A.; Zobel, J. P.; Lindh, R. OpenMolcas: From Source Code to Insight. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 5925–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chibotaru, L. F.; Ungur, L.; Soncini, A. The Origin of Nonmagnetic Kramers Doublets in the Ground State of Dysprosium Triangles: Evidence for a Toroidal Magnetic Moment. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2008, 47, 4126–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungur, L.; Van den Heuvel, W.; Chibotaru, L. F. Ab initio investigation of the non-collinear magnetic structure and the lowest magnetic excitations in dysprosium triangles. New J. Chem. 2009, 33, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibotaru, L. F.; Ungur, L.; Aronica, C.; Elmoll, H.; Pilet, G.; Luneau, D. Structure, Magnetism, and Theoretical Study of a Mixed-Valence CoII3CoIII4 Heptanuclear Wheel: Lack of SMM Behavior despite Negative Magnetic Anisotropy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12445–12455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunghi, A.; Totti, F.; Sessoli, R.; Sanvito, S. The role of anharmonic phonons in under-barrier spin relaxation of single molecule magnets. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14620–14626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.; Ding, M. M.; Li, J. X.; Wang, B. L.; Zhang, Y. Q. Why lanthanide ErIII SIMs cannot possess huge energy barriers: a theoretical investigation. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 14576–14583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Guo, W. X.; Zhang, Y. Q. Largely Enhancing the Blocking Energy Barrier and Temperature of a Linear Cobalt(II) Complex through the Structural Distortion: A Theoretical Exploration. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M. M.; Shang, T.; Hu, R.; Zhang, Y. Q. Understanding the magnetic anisotropy for linear sandwich [Er(COT)]+-based compounds: a theoretical investigation. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 3295–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, T.; Lu, F.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y. Q. Understanding the Magnetic Relaxation Mechanism in Mixed-Valence Dilanthanide Complexes with Metal–Metal Bonding: A Theoretical Investigation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 3088–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).