Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Index and Relatives

2.2. Coagulation Tests

2.3. Genetic Investigation

2.4. In Silico Analysis of Pathogenicity

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Features of Cases with FXI Deficiency

3.2. Molecular Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barg AA, Livnat T, Kenet G. Factor XI deficiency: phenotypic age-related considerations and clinical approach towards bleeding risk assessment. Blood. 2024;143:1455-1464. [CrossRef]

- Asakai R, Chung DW, Davie EW, Seligsohn U. Factor XI deficiency in Ashkenazi Jews in Israel. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:153-158. [CrossRef]

- Asselta R, Paraboschi EM, Rimoldi V, Menegatti M, Peyvandi F, Salomon O, Duga S. Exploring the global landscape of genetic variation in coagulation factor XI deficiency. Blood. 2017;130:e1-e6. [CrossRef]

- Peyvandi F, Palla R, Menegatti M, Siboni SM, Halimeh S, Faeser B, et al. European Network of Rare Bleeding Disorders Group. Coagulation factor activity and clinical bleeding severity in rare bleeding disorders: results from the European Network of Rare Bleeding Disorders. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:615-621. [CrossRef]

- Saes JL, Verhagen MJA, Meijer K, Cnossen MH, Schutgens REG, Peters M, et al. Bleeding severity in patients with rare bleeding disorders: real-life data from the RBiN study. Blood Adv. 2020;4:5025-5034. [CrossRef]

- Moellmer SA, Puy C, McCarty OJT. Biology of factor XI. Blood. 2024;143:1445-1454.

- Palla R, Siboni SM, Menegatti M, Musallam KM, Peyvandi F; European Network of Rare Bleeding Disorders EN-RBD group. European Network of Rare Bleeding Disorders (EN-RBD) group. Establishment of a bleeding score as a diagnostic tool for patients with rare bleeding disorders. Thromb Res. 2016;148:128-134. [CrossRef]

- Duga S, Salomon O. Congenital factor XI deficiency: an update. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013;39:621-631. [CrossRef]

- D'Andrea, G.; Colaizzo, D.; Vecchione, G.; Grandone, E.; Di Minno, G.; Margaglione, M.; GLAnzmann's Thrombasthenia Ita- 489 lian Team (GLATIT). Glanzmann's thrombasthenia: identification of 19 new mutations in 30 patients. Thromb. Haemost. 2002, 490 87, 1034-42. [CrossRef]

- Pugh RE, McVey JH, Tuddenham EG, Hancock JF. Six point mutations that cause factor XI deficiency. Blood. 1995;85:1509-16. [CrossRef]

- Castaman G, Giacomelli SH, Dragani A, Iuliani O, Duga S, Rodeghiero F. Severe factor XI deficiency in the Abruzzo region of Italy is associated to different FXI gene mutations. Haematologica. 2008;93:957-8. [CrossRef]

- Saunders RB, Shiltagh N, Gomez K, Mellars G, Cooper C, Perry DJ, et al. Structural analysis of eight novel and 112 previously reported missense mutations in the interactive FXI mutation database reveals new insight on FXI deficiency. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:287-301. [CrossRef]

- Esteban J, de la Morena-Barrio ME, Salloum-Asfar S, Padilla J, Miñano A, Roldán V, Soria JM, Vidal F, Corral J, Vicente V. High incidence of FXI deficiency in a Spanish town caused by 11 different mutations and the first duplication of F11: Results from the Yecla study. Haemophilia. 2017;23:e488-e496. [CrossRef]

- Guella I, Soldà G, Spena S, Asselta R, Ghiotto R, Tenchini ML et al. Molecular characterization of two novel mutations causing factor XI deficiency: a splicing defect and a missense mutation responsible for a CRM+defect. Thromb Haemost 2008; 99: 523-530. [CrossRef]

- Smith SB, Gailani D. Update on the physiology and pathology of factor IX activation by factor XIa. Expert Rev Hematol. 2008;1:87-98. [CrossRef]

- Sharman Moser S, Chodick G, Ni YG, Chalothorn D, Wang MD, Shuldiner AR, Morton L, Salomon O, Jalbert JJ. The Association between Factor XI Deficiency and the Risk of Bleeding, Cardiovascular, and Venous Thromboembolic Events. Thromb Haemost. 2022;122:808-817. [CrossRef]

- Zadra G, Asselta R, Tenchini ML, Castaman G, Seligsohn U, Mannucci PM et al. Simultaneous genotyping of coagulation factor XI type II and type III mutations by multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction to determine their prevalence in healthy and factor XI-deficient Italians. Haematologica 2008;93: 715-721. [CrossRef]

- Castaman G, Giacomelli SH, Caccia S, Riccardi F, Rossetti G, Dragani A et al. The spectrum of factor XI deficiency in Italy. Haemophilia 2014; 20: 106-113. [CrossRef]

- O'Connell NM, Saunders RE, Lee CA, Perry DJ, Perkins SJ. Structural interpretation of 42 mutations causing factor XI deficiency using homology modeling. J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3: 127-138. [CrossRef]

- Harlow SD, Campbell OM. Epidemiology of menstrual disorders in developing countries: a systematic review. BJOG. 2004; 111:6-16. [CrossRef]

- Fasulo MR, Biguzzi E, Abbattista M, Stufano F, Pagliari MT, Mancini I, et al. The ISTH Bleeding Assessment Tool and the risk of future bleeding. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:125- 130. [CrossRef]

- Tiscia G, Favuzzi G, Chinni E, Colaizzo D, Fischetti L, Intrieri M, et al. Factor VII deficiency: a novel missense variant and genotype-phenotype correlation in patients from Southern Italy. Hum Genome Var. 2017;4:17048. [CrossRef]

- Barcellona D, Favuzzi G, Vannini ML, Piras SM, Ruberto MF, Grandone E, Marongiu F. A Sardinian Family with Factor XI Deficiency. Hamostaseologie. 2019;39:398-403. [CrossRef]

| Case index # | Sex | Age at the presentation | FXI activity (IU/dL ) | Variant 1 | Variant 2 | Symptoms |

| 1 | F | 21 | 51 | p.Asp34His | Asymptomatic | |

| 1-1 | F | 26 | 47 | p.Asp34His | Asymptomatic | |

| 1-2 | F | 49 | 55 | p.Asp34His | Asymptomatic | |

| 2 | M | 58 | 43 | p.Cys56Trp | Bleeding after surgery | |

| 2-1 | M | 32 | 38 | p.Cys56Trp | Asymptomatic | |

| 2-2 | F | 25 | 38 | p.Cys56Trp | Asymptomatic | |

| 3 | F | 56 | 42 | p.Val89stop | Repeated bleeding after surgery | |

| 4 | M | 35 | 32 | C.325+1G>A | Epixastis | |

| 5 (a) | F | 1 | 1 | p.Ala109Thr | C.325+1G>A | Asymptomatic |

| 5-1 | M | 31 | 48 | C.325+1G>A | Asymptomatic | |

| 5-2 | F | 4 | 41 | p.Ala109Thr | Asymptomatic | |

| 5-3 | F | 29 | 35 | p.Ala109Thr | Asymptomatic | |

| 6 (a) | M | 32 | 39 | p.Glu135X | Epixastis | |

| 7 (a) | F | 60 | 44 | p.Glu135X | Repeated bleeding after surgery, Menorrhagia | |

| 8 (a) | F | 26 | 38 | p.Glu135X | Asymptomatic | |

| 8-1 | F | 37 | 34 | p.Glu135X | Asymptomatic | |

| 9 | M | 16 | 28 | p.Glu135X | Asymptomatic | |

| 9-1 | F | 13 | 25 | p.Glu135X | Asymptomatic | |

| 9-2 | M | 43 | 48 | p.Glu135X | bleeding after surgery or trauma | |

| 9-3 | F | 46 | 33 | p.Glu135X | Asymptomatic | |

| 10 | F | 7 | 4 | p.Glu135X | p.Cys321fs | Asymptomatic |

| 10-1 | F | 34 | 69 | p.Cys321fs | Asymptomatic | |

| 10-2 | F | 5 | 3 | p.Glu135X | p.Cys321fs | Asymptomatic |

| 10-3 | F | 3 | 39 | p.Glu135X | Asymptomatic | |

| 11 (b) | F | 47 | 1 | p.Glu135X | Repeated bleeding after surgery or trauma | |

| 11-1 | M | 76 | 50 | p.Glu135X | Asymptomatic | |

| 11-2 | F | 74 | 76 | p.Glu135X | Asymptomatic | |

| 11-3 | M | 45 | 1 | p.Glu135X | Repeated bleeding after surgery or trauma | |

| 11-4 | F | 33 | 52 | p.Glu135X | Asymptomatic | |

| 11-5 | M | 41 | 2 | p.Glu135X | Repeated bleeding after surgery or trauma | |

| 12 (a) | F | 55 | 1 | p.Glu135X | p.Cys136Arg | Asymptomatic |

| 12-1 | F | 57 | 2 | p.Glu135X | p.Cys136Arg | Asymptomatic |

| 13 | F | 26 | 40 | p.Glu135X | Menorrhagia | |

| 14 | F | 41 | 60 | p.Glu135X | Menorrhagia | |

| 15 | M | 10 | 22 | p-Thr141Met | Asymptomatic | |

| 15-1 | M | 54 | 35 | p-Thr141Met | Asymptomatic | |

| 16 (a) | M | 7 | 34 | p.Thr150Met | Epistaxis | |

| 16-1 | M | 38 | 52 | p.Thr150Met | Epistaxis | |

| 16-2 | M | 46 | 41 | p.Thr150Met | Asymptomatic | |

| 16-3 | M | 21 | 34 | p.Thr150Met | Epistaxis | |

| 17 (a) | F | 6 | 47 | p.Arg162Cys | Asymptomatic | |

| 17-1 | F | 6 | 43 | p.Arg162Cys | Asymptomatic | |

| 17-2 | F | 36 | 45 | p.Arg162Cys | Asymptomatic | |

| 18 (a) | M | 20 | 34 | p.Cys230Arg | Bleeding after surgery | |

| 18-1 | F | 50 | 34 | p.Cys230Arg | Asymptomatic | |

| 19 | M | 41 | 44 | p.Phe301Leu | Repeated bleeding after surgery | |

| 20 | F | 5 | 46 | p.Phe301Leu | Asymptomatic | |

| 21 (a) | F | 8 | 6 | p.Phe301Leu | p.Trp519X | Bleeding after surgery |

| 21-1 | F | 39 | 40 | p.Phe301Leu | Asymptomatic | |

| 22 (a) | F | 14 | 4 | p.Phe301Leu | c.595+3A>G | Asymptomatic |

| 22-1 | F | 43 | 85 | c.595+3A>G | Asymptomatic | |

| 22-2 | M | 49 | 51 | p.Phe301Leu | Asymptomatic | |

| 23 | M | 15 | 40 | p.Leu306Pro | Asymptomatic | |

| 23-1 | F | 11 | 45 | p.Leu306Pro | Asymptomatic | |

| 23-2 | F | 49 | 38 | p.Leu306Pro | Asymptomatic | |

| 24 | F | 3 | 34 | p.Glu315Lys | p.Ala561Asp | Asymptomatic |

| 24-1 | F | 29 | 36 | p.Glu315Lys | p.Ala561Asp | Asymptomatic |

| 25 | F | 37 | 28 | p.Glu315Lys | Menorrhagia | |

| 25-1 | F | 36 | 33 | p.Glu315Lys | Bleeding after surgery | |

| 25-2 | M | 66 | 18 | p.Glu315Lys | Bleeding after surgery | |

| 26 (a) | F | 24 | 7 | p.Glu315Lys | p.Trp519X | Menorrhagia |

| 26-1 | F | 22 | 29 | p.Glu315Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 26-2 | M | 60 | 49 | p.Trp519X | Asymptomatic | |

| 26-3 | F | 46 | 39 | p.Glu315Lys | Repeated bleeding after trauma | |

| 27 | M | 16 | 34 | p.Glu315Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 27-1 | M | 45 | 27 | p.Glu315Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 28 | M | 10 | 31 | p.Glu315Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 28-1 | F | 49 | 37 | p.Glu315Lys | Menorrhagia | |

| 29 | M | 4 | p.Glu315Lys | Asymptomatic | ||

| 30 | F | 15 | 36 | p.Glu315Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 30-1 | M | 38 | 28 | p.Glu315Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 31 | M | 6 | 41 | p.Glu315Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 31-1 | M | 40 | 40 | p.Glu315Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 32 (a) | F | 18 | 38 | p.Arg326His | Asymptomatic | |

| 32-2 | F | 44 | 62 | p.Arg326His | Asymptomatic | |

| 33 (a) | F | 29 | 43 | p.Gly418Val | Spontaneous ecchymoses | |

| 33-1 | F | 52 | 45 | p.Gly418Val | Repeated bleeding after trauma | |

| 34 | M | 10 | 21 | p.Arg497Gln | Asymptomatic | |

| 35 (a) | F | 40 | 14 | p.Trp515Gly | Asymptomatic | |

| 35-1 | M | 17 | 30 | p.Trp515Gly | Asymptomatic | |

| 35-2 | F | 15 | 44 | p.Trp515Gly | Asymptomatic | |

| 35-3 | F | 43 | 27 | p.Trp515Gly | Asymptomatic | |

| 35-4 | M | 46 | 36 | p.Trp515Gly | Asymptomatic | |

| 35-6 | F | 69 | 36 | p.Trp515Gly | Asymptomatic | |

| 36 | F | 82 | 40 | P.Glu565Lys | Repeated bleeding after surgery | |

| 37 | F | 18 | 29 | P.Glu565Lys | Spontaneous ecchymoses | |

| 37-1 | M | 57 | 50 | P.Glu565Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 38 | M | 10 | 30 | P.Glu565Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 38-1 | M | 6 | 28 | P.Glu565Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 38-2 | M | 36 | 28 | P.Glu565Lys | Repeated bleeding after surgery - Epistaxis | |

| 38-3 | F | 63 | 39 | P.Glu565Lys | Asymptomatic | |

| 39 | M | 21 | 48 | c.1717-2A>G | Epistaxis | |

| 39-1 | F | 24 | 42 | c.1717-2A>G | Asymptomatic |

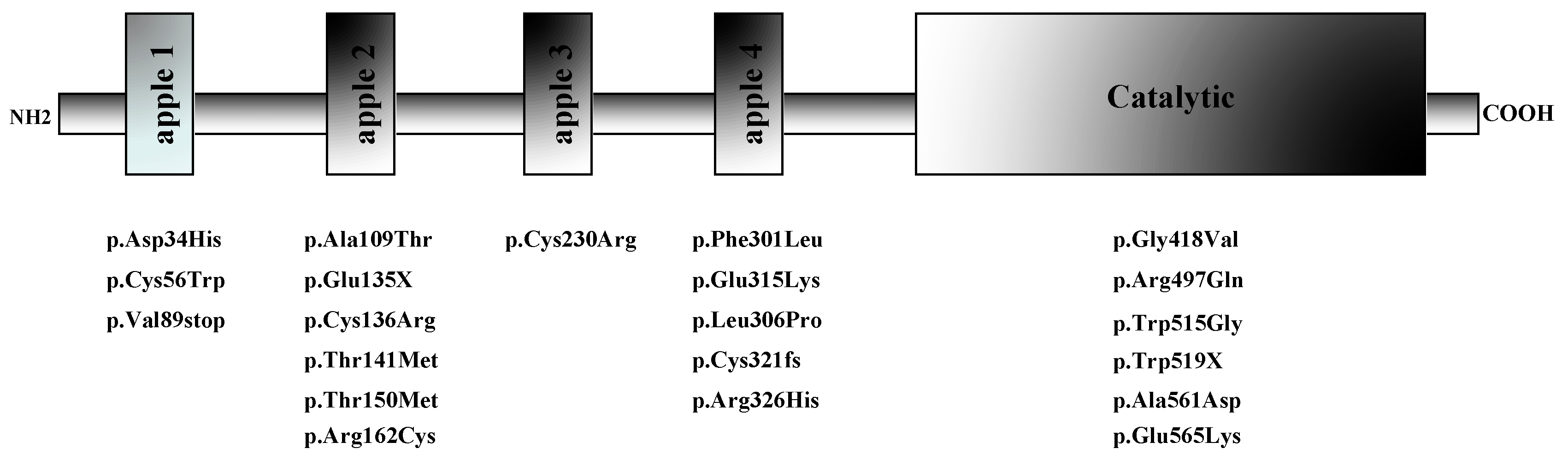

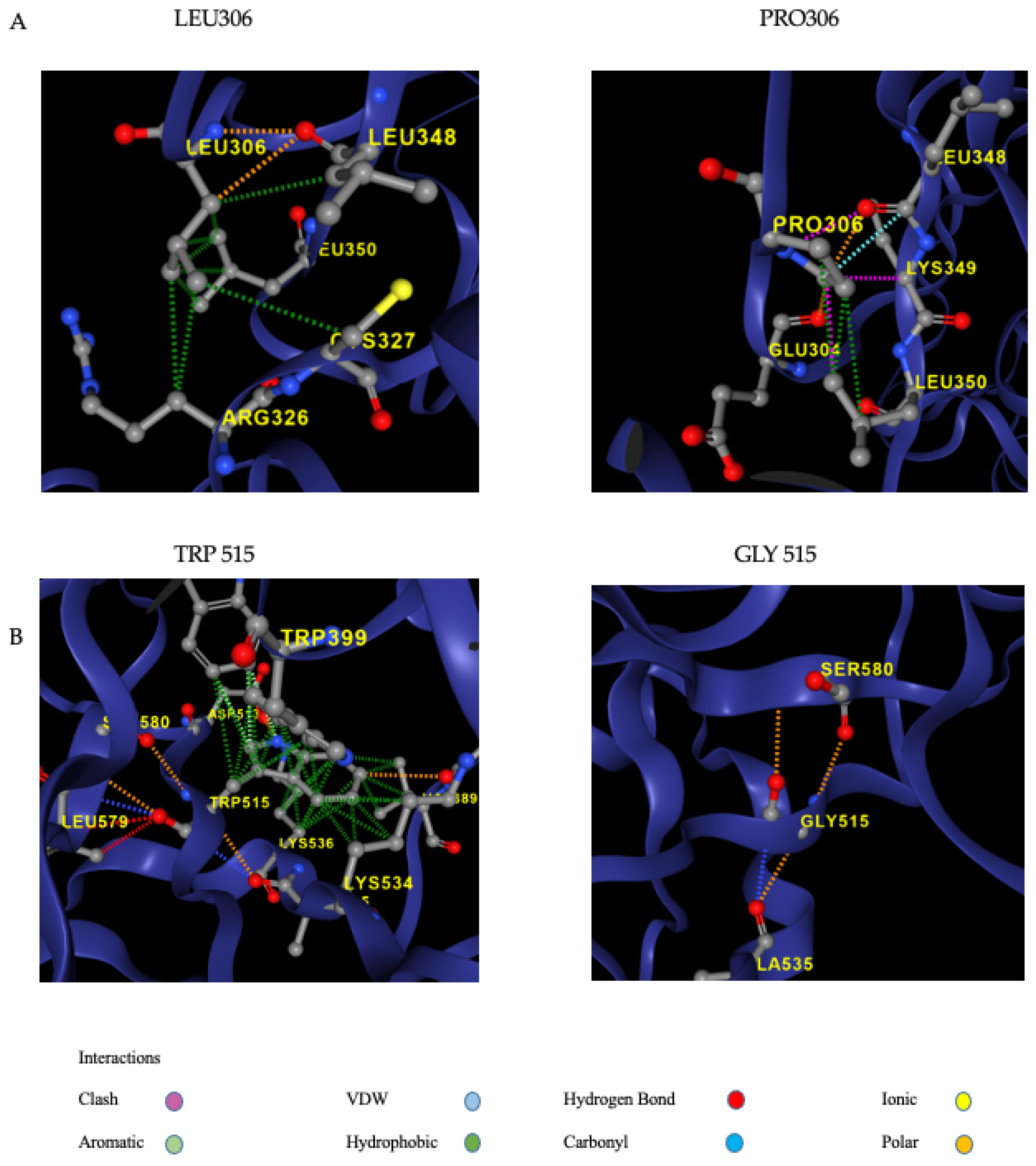

| GENE | Protein Variation | Frequencies | ClinVar | DyneMut2_ (ΔΔGStability) | Predicted Stability Change | Effect on Protein Structure | ACMG | ACMG Supporting Criteria |

| FXI | p.Leu306Pro | Exomes: not found genomes: not found |

No data available | -0,32 kcal/mol | destabilising | disallowed phi/psi | VUS | PM2,PP3,PP2 |

| FXI | p.Trp515Gly | exomes: not found genomes: not found (cov: 31.9) |

No data available | -2,94 kcal/mol | destabilising |

-disrupts all H-bonds

-expansion of cavity |

VUS | PM2,PP3,PP2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).