Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Conditions

2.2. Alcohol Treatments

2.3. Measured Traits

2.3.1. Determination of Leaf Chlorophyll Index (LCI) and Fluorescence

2.3.2. Gas Exchange Measurements

2.3.3. Morphological Traits

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

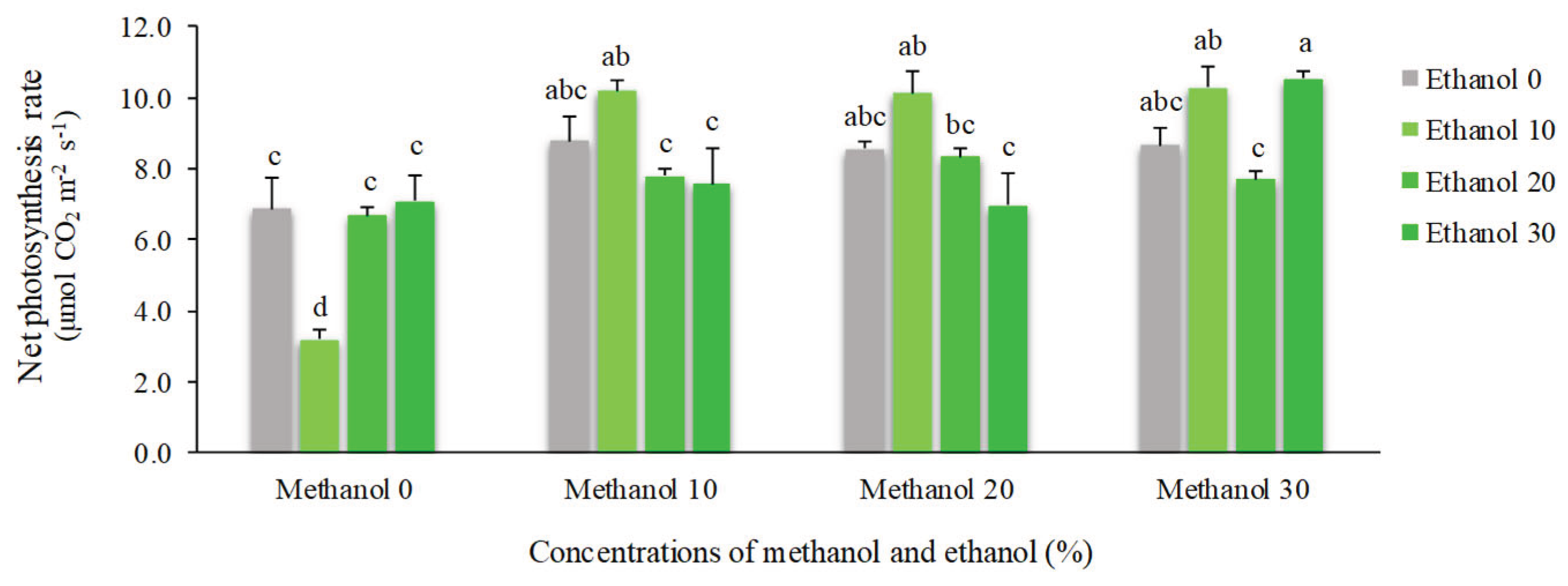

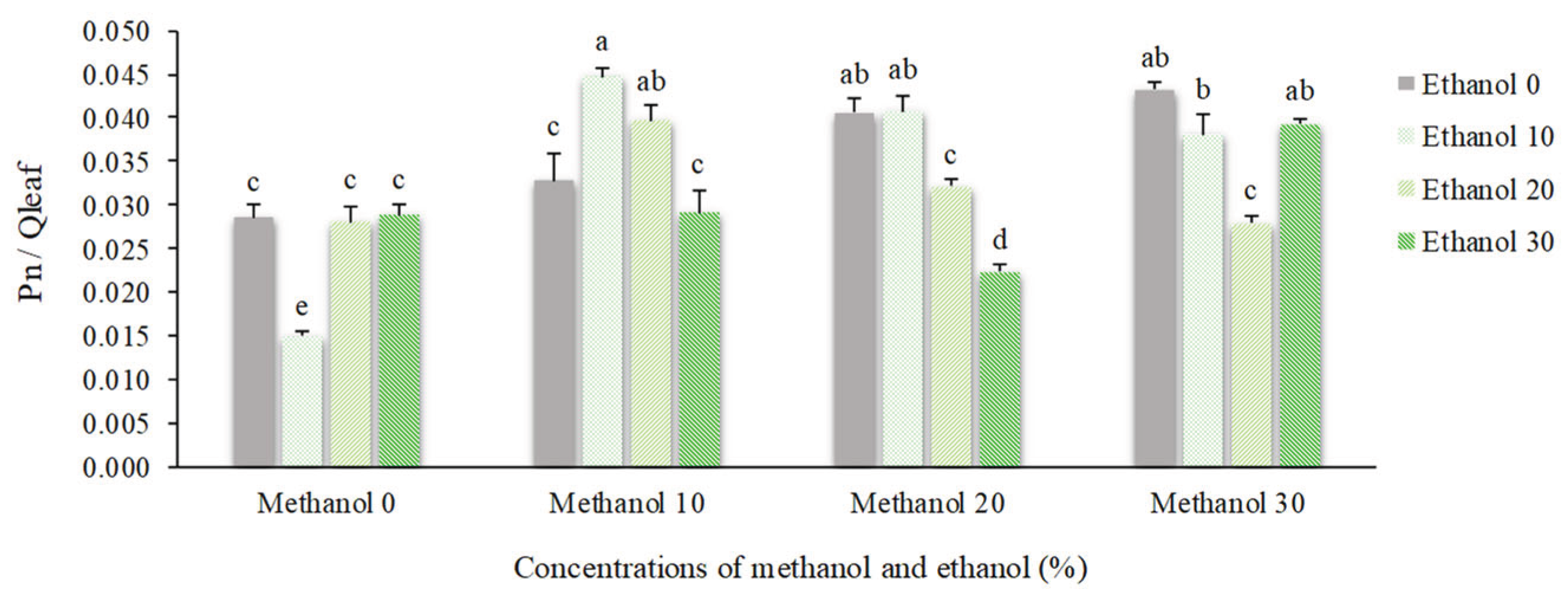

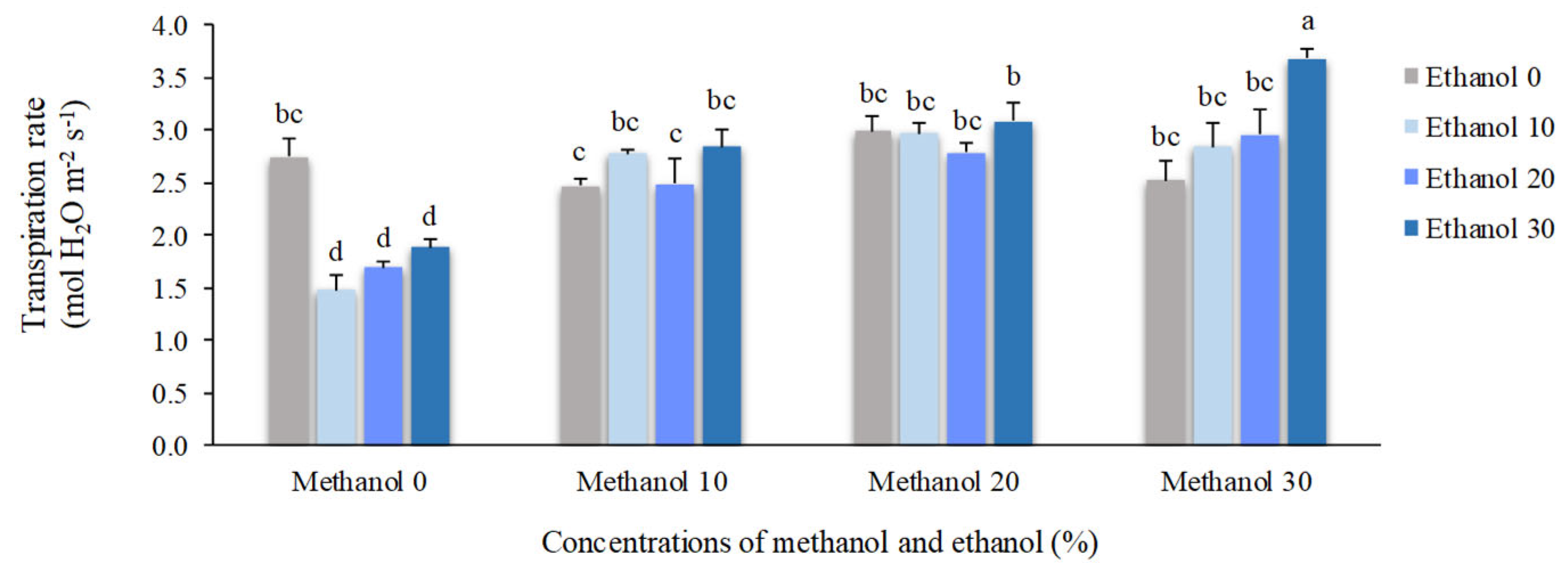

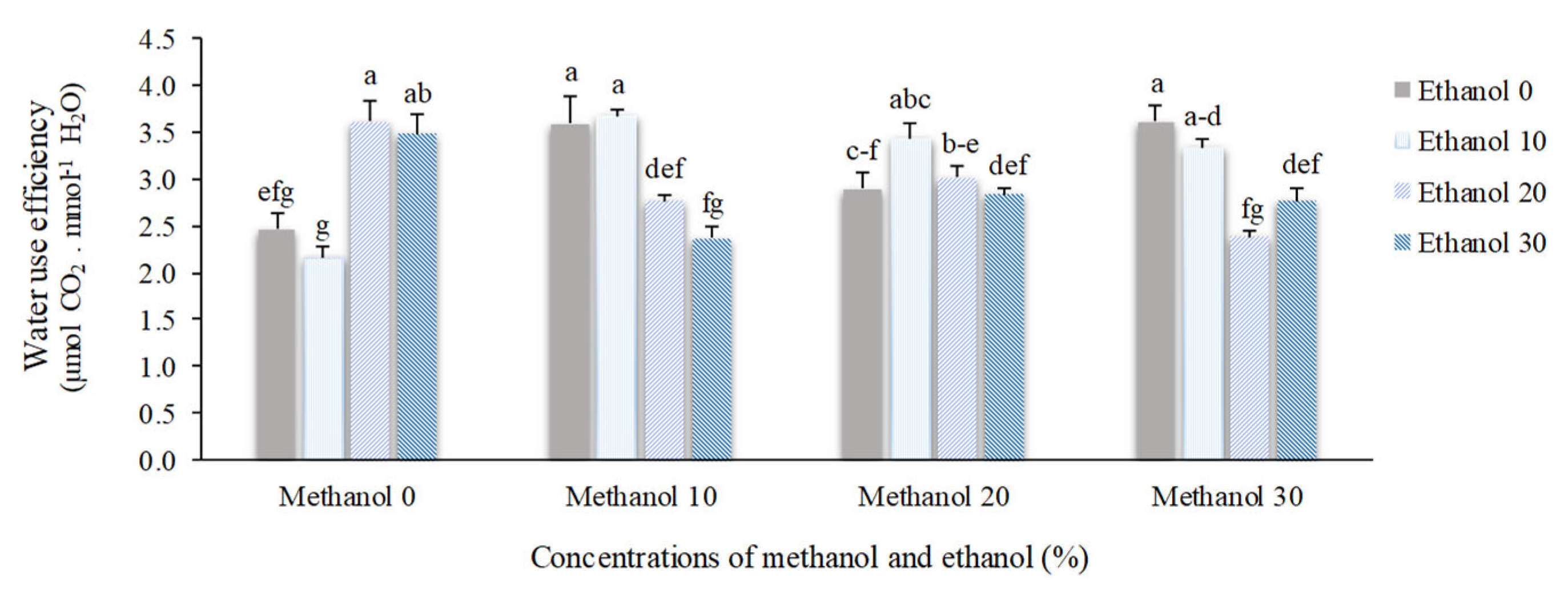

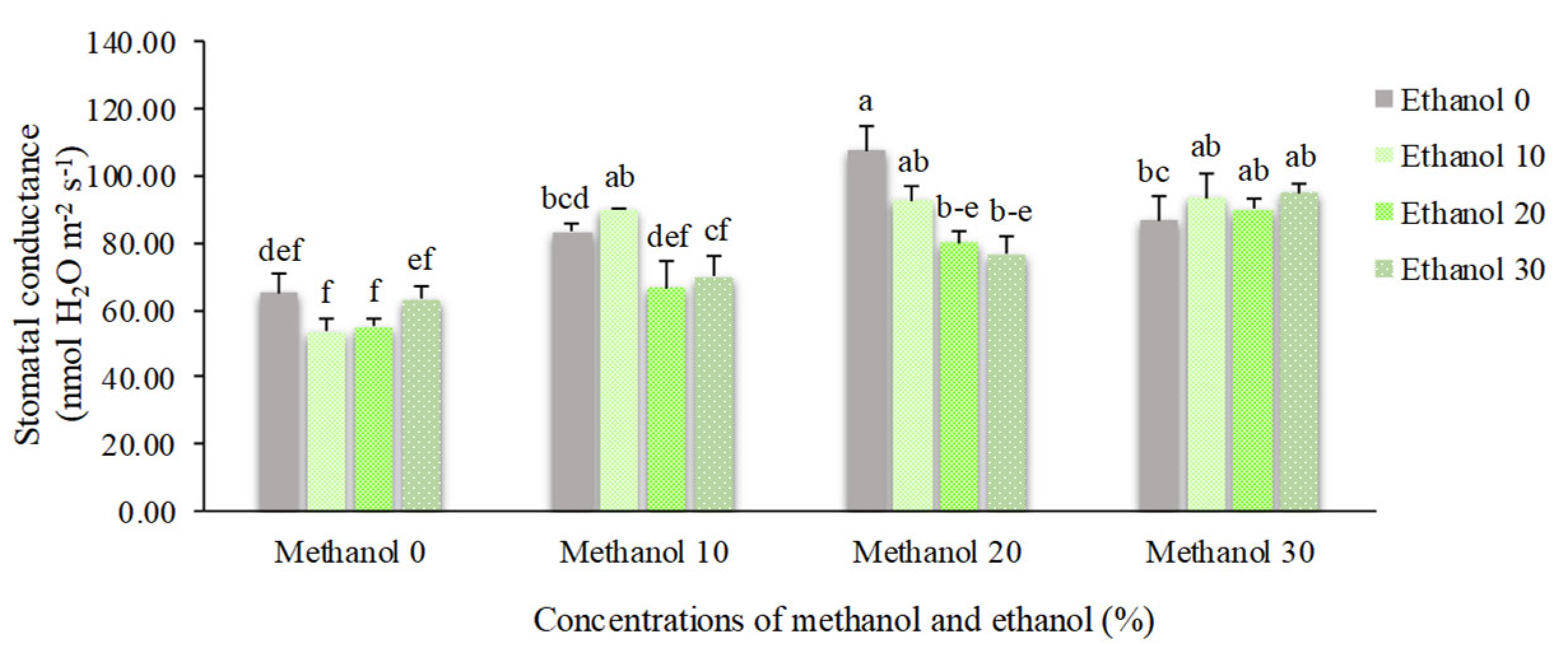

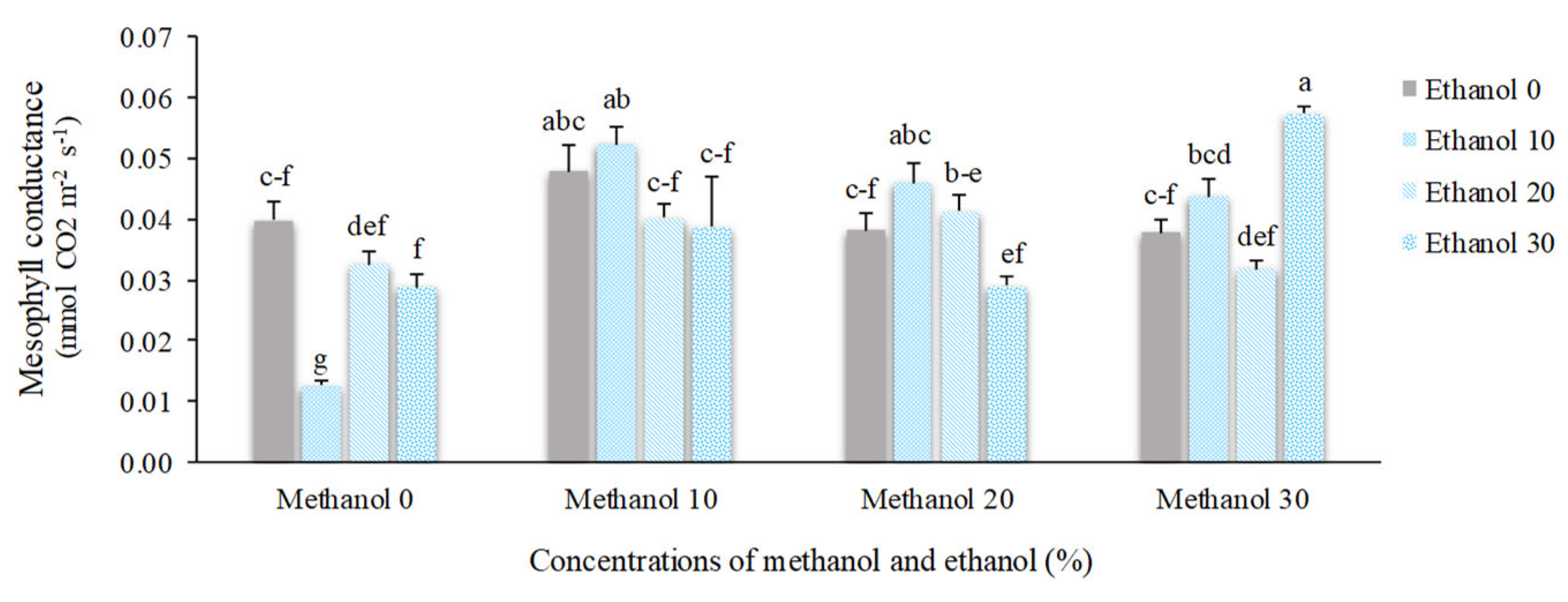

3.1. Gas Exchange Measurements

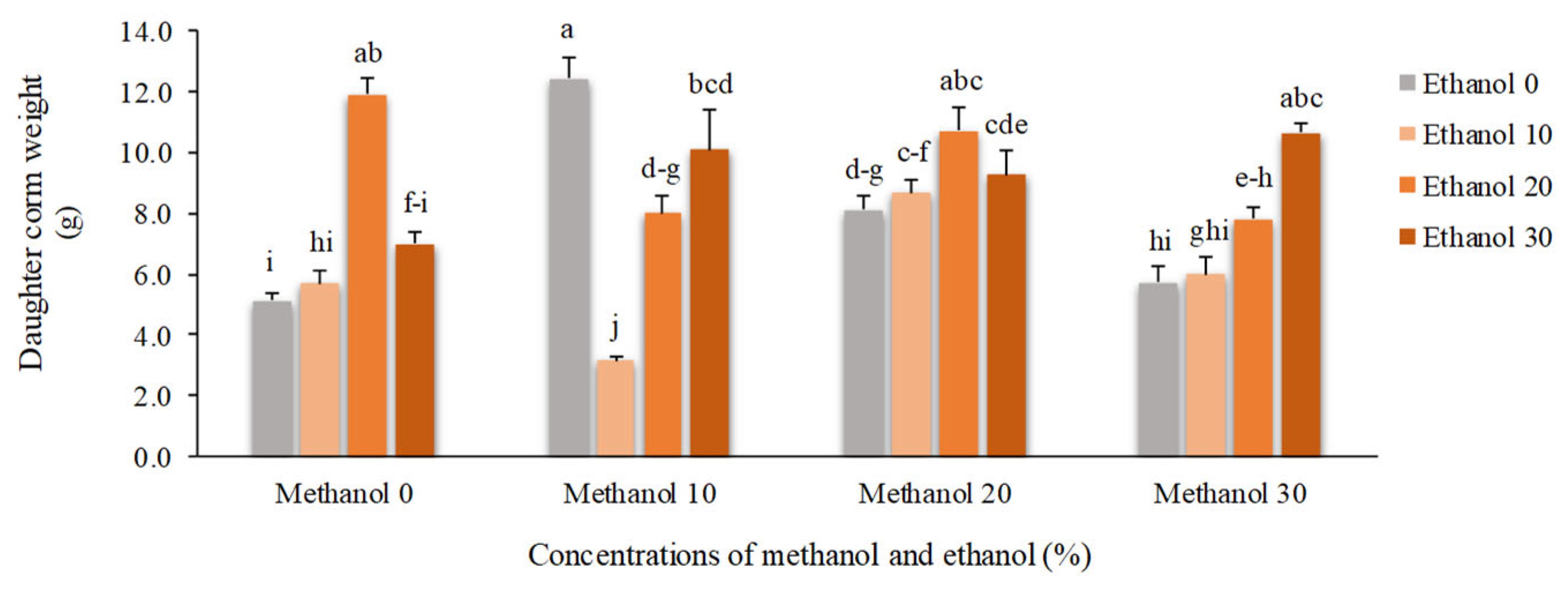

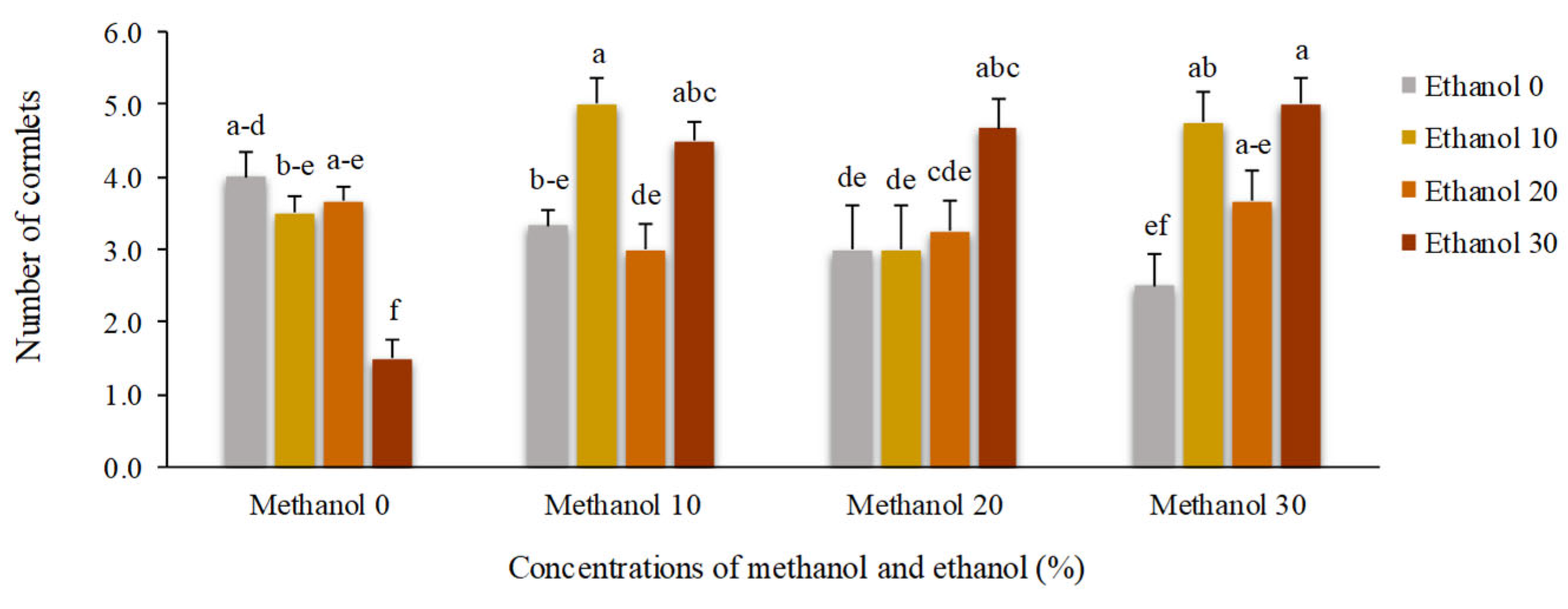

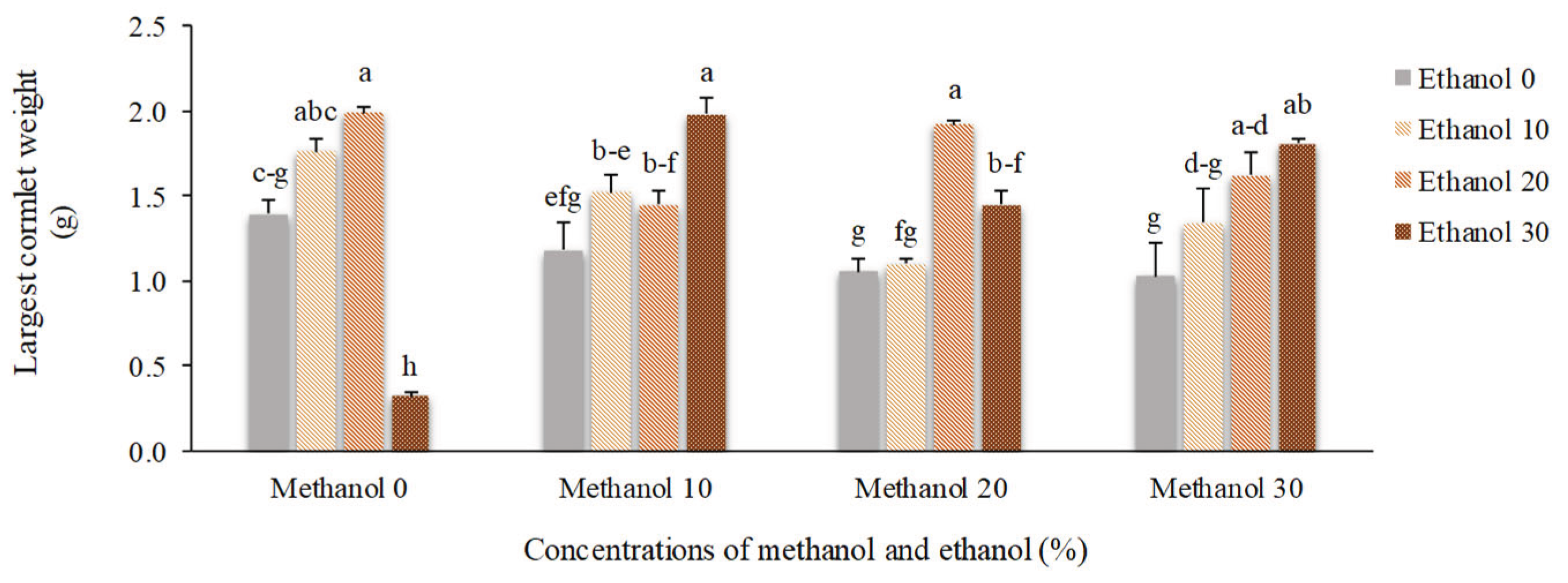

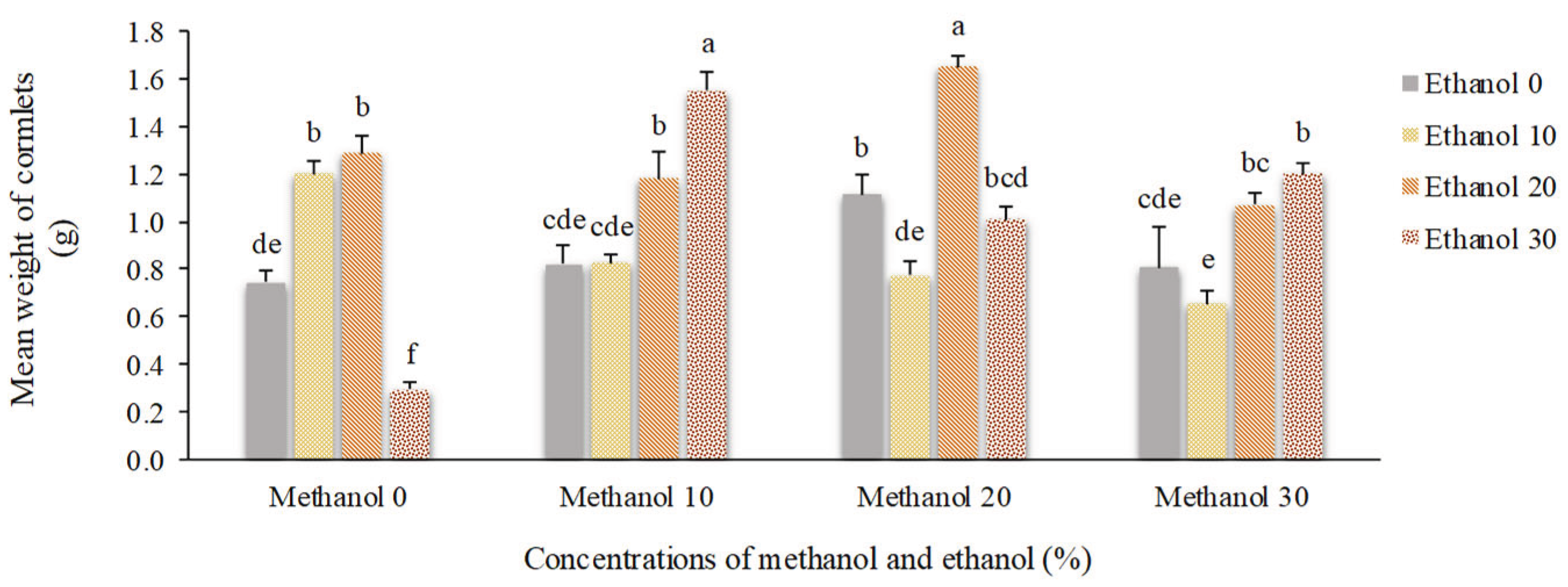

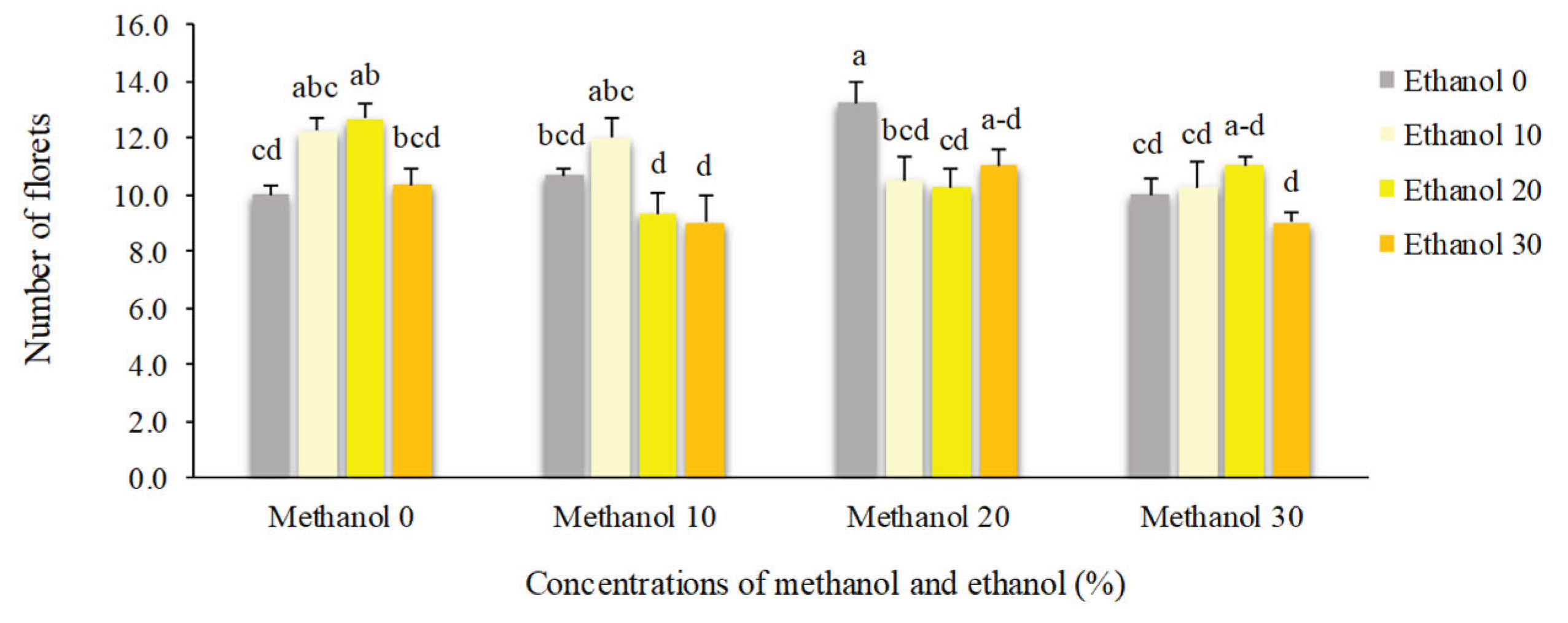

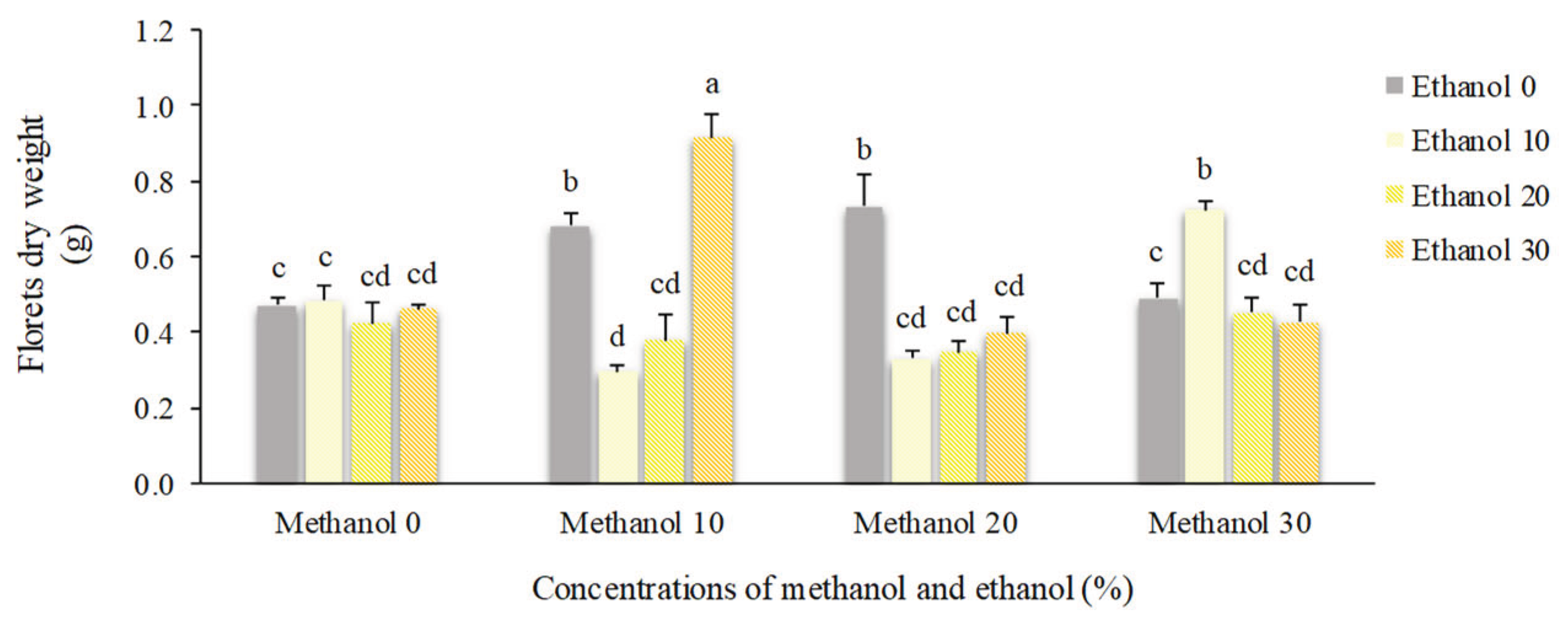

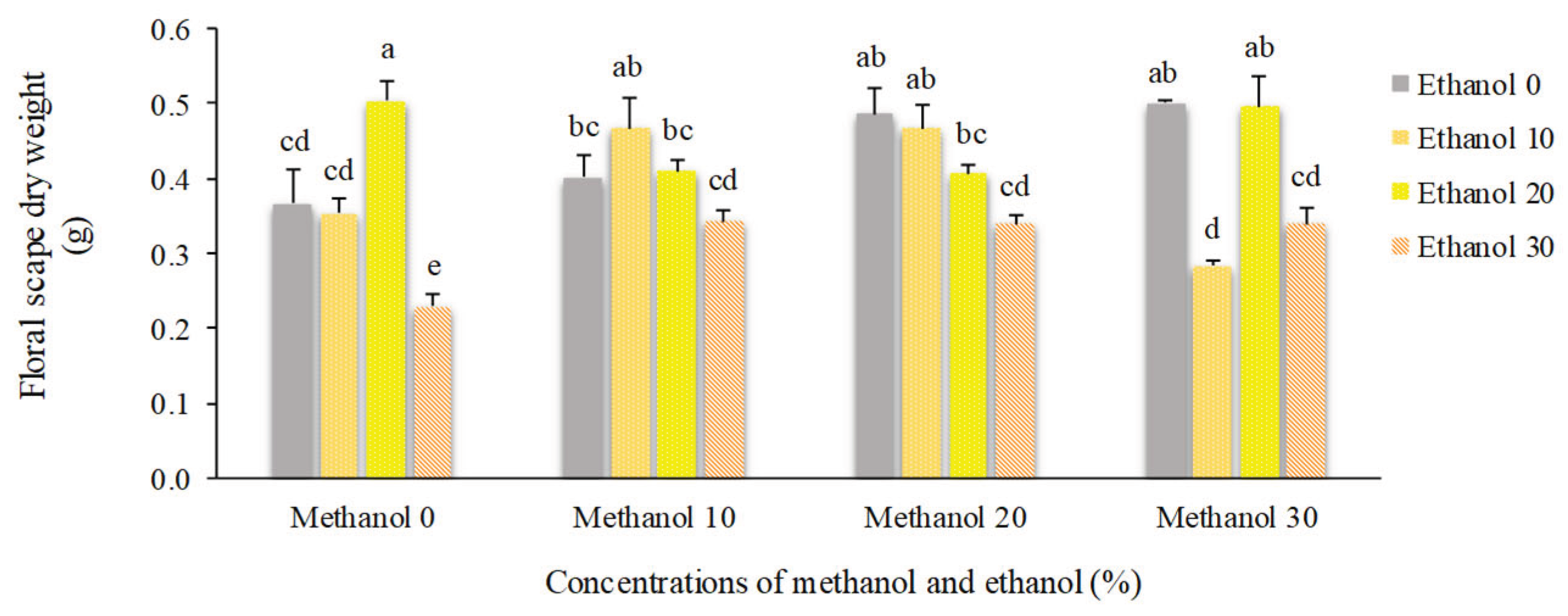

3.2. Morphological Traits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Pn | Net photosynthesis |

| Pn/Qleaf | The quantum efficiency of photosynthesis |

| Tr | Transpiration rate |

| WUEins | Instantaneous water-use efficiency |

| Ci | Sub-stomatal CO2 |

| gs | Stomatal conductance |

| gm | Mesophyll conductance |

References

- Anderson, N. O. Flower breeding and genetics issues, challenges and opportunities for the 21st century; Springer: The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 665–693. [Google Scholar]

- De Hertogh, A.; Le Nard, M. The physiology of flower bulbs; Elsevier: The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, P.V. Greenhouse operation and management – Seventh Edition; Pearson: USA, 2014; pp. 336–342. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Lv, J.; Wang, J.; Shi, K. CO2 enrichment in greenhouse production: Towards a sustainable approach. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1029901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonomura, A.M.; Benson, A.A. The path of carbon in photosynthesis: Improved crop yields with methanol. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89, 9794–9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andre´s, R.; La`zaro, J.; Chueca, A.; Hermoso, R.; Gorge´, L. Effect of alcohols on the association of photosynthetic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase to thylakoid membranes. Physiol. Plant. 1990, 78, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, D.; Criddle, R.; Hansen, L. Effects of methanol on plant respiration. J. Plant Physiol. 1995, 146, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorokhov, Y.L.; Sheshukova, E.V; Komarova, T.V. Methanol in plant life. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komarova, T.V.; Sheshukova, E.V.; Dorokhov, Y.L. Cell wall methanol as a signal in plant immunity. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorokhov, Y.L.; Shindyapina, A.V.; Sheshukova, E.V.; Komarova, T.V. Metabolic methanol: molecular pathways and physiological roles. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 603–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, J.N.; Huang, S.; Winder, T.L.; Brownson, M.P.; Ngo, L. Physiological aspects of methanol feeding to higher plants. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting of Plant Growth Regulator Society of America, USA; 1994; pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Speight, J.G. Biomass Processes and Chemicals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tesniere, C.; Torregrosa, L.; Pradal, M.; Souquet, J.-M.; Gilles, C.; Dos Santos, K.; Chatelet, P.; Gunata, Z. Effects of genetic manipulation of alcohol dehydrogenase levels on the response to stress and the synthesis of secondary metabolites in grapevine leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Anik, T.R.; Rahman, M.M.; Keya, S.S.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.A.; Sultana, S.; Ghosh, P.K.; Khan, S.; Ahamed, T. Ethanol treatment enhances physiological and biochemical responses to mitigate saline toxicity in soybean. Plants 2022, 11, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Sako, K.; Matsui, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Mostofa, M.G.; Ha, C.V.; Tanaka, M.; Tran, L.-S.P.; Habu, Y.; Seki, M. Ethanol enhances high-salinity stress tolerance by detoxifying reactive oxygen species in Arabidopsis thaliana and rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, L.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Song, H.; Rong, X.; Han, Y. Low concentration of exogenous ethanol promoted biomass and nutrient accumulation in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). Plant Signal Behav. 2019, 14, 1681114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Mostofa, M.G.; Das, A.K.; Anik, T.R.; Keya, S.S.; Ahsan, S.M.; Khan, M.A.R.; Ahmed, M.; Rahman, M.A.; Hossain, M.M.; Tran, L.S.P. Ethanol positively modulates photosynthetic traits, antioxidant defense and osmoprotectant levels to enhance drought acclimatization in soybean. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, M.; Prasad, R. Effect of plant growth regulators based on long chain aliphatic alcohols on seed and straw yield of lentil. Lens Newsl. 1990, 17, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, R.; Bhowmik, P.; Karczmarczyck, S. Influence of methanol on plant growth. PGRSA Q. 1994, 22, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, R.; Farr, D.; Richards, B. Effects of foliar and root applications of methanol or ethanol on the growth of tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. ). N.Z. J. Crop. Hort. Sci. 1994, 22, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, A.; Karkkainen, J.; Peltonen, J.; Peltonen-Sainio, P. Foliar applications of alcohols failed to enhance growth and yield of C3 crops. Ind. Crops Prod. 1998, 7, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iersel, M.; Heitholt, J.; Wells, R.; Oosterhuis, M. Foliar methanol applications to cotton in the southeastern United States: leaf physiology, growth, and yield components. Agron. J. 1995, 87, 1157–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satler, S.; Thimann, K. The influence of aliphatic alcohols on leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 1980, 66, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltveit, M. Effect of alcohols and their interaction with ethylene on the ripening of epidermal pericarp discs of tomato fruit. Plant Physiol. 1989, 90, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossins, E.A. The utilization of carbon-1-compounds by plants. Can. J. Bot. 1964, 42, 1793–1802. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, G.D.; Sharkey, T.D. Stomatal conductance and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1982, 33, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGiffen, M.E.; Manthey, J.A. The role of methanol in promoting plant growth: A current evaluation. HortScience. 1996, 31, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esensee, V.; Leskovar, D.; Boales, A. Inefficacy of methanol as a growth promoter in selected vegetable crops. HortTechnology. 1995, 5, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feibert, E.; James, S.; Rykbost, K.; Mitchell, A.; Shock, A. Potato yield and quality not changed by foliar-applied methanol. HortScience. 1995, 30, 494–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonomura, A.M.; Benson, A.A. The path of carbon in photosynthesis: Methanol and light. In Research in photosynthesis; Murata, N., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1992b; pp. 911–914. [Google Scholar]

- Hartz, T.K.; Mayberry, K.S.; McGiffen, M.E., Jr.; LeStrange, M.; Miyao, G.; Baameur, A. Foliar methanol application ineffective in tomato and melon. HortScience, 1994, 22, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauney, J.R.; Gerik, T.J. Evaluating methanol usage in cotton. In: Proc. Beltwide Cotton Conf., San Diego, Calif., vol. 1. Natl. Cotton Council of Amer., Memphis, Tenn, 1994; pp. 39–40.

- McGiffen, M.E.; Green, R.L.; Manthey, J.A.; Faber, B.A.; Downer, A.J.; Sakovich, N.J.; Aguiar, J. Field tests of methanol as a crop yield enhancer. HortScience 1995, 30, 1225–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Douglas, C.L., Jr.; Klepper, E.L.; Rasmussen, P.E.; Rickman, R.W.; Smiley, R.W.; Wilkins, D.E.; Wysocki, D.J. Effects of foliar methanol applications on crop yield. Crop Sci. 1995, 35, 1642–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonomura, A.M.; Nishio, J.N.; Benson, A.A. Stimulated growth and correction of Fe deficiency with trunk- and foliar-applied methanol- soluble nutrient amendments. In: Iron nutrition in soils and plants. J. Abadia (ed.). Kluwer Academic Publisher, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1995; pp. 329–333.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).