1. Introduction

Anxiety disorders and depression (also known as internalising disorders) are at peak prevalence and onset during adolescence. Concerningly, adolescents with internalising disorders are 1.54 times more likely to suicide (Kessler et al., 2007), and suicide is the fourth leading cause of death among adolescents worldwide (World Health Organization, 2021). As such, preventing suicide is considered a global health imperative (World Health Organization, 2014). Beyond the devastating loss of life, many more adolescents experience suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020). Yet despite the distress of these adolescents, research has found that the majority of these adolescents (approximately 50% to 60%) do not seek professional help (Fortune et al., 2008; Hallford et al., 2023). Rather, adolescents with mental disorders are more likely to seek support from informal sources, and in particular, their parents (Jorm et al., 2007; Yap et al., 2013).

Parents present as opportune partners in adolescent suicide prevention for several reasons. First, a systematic review identified parental factors such as warmth, autonomy granting, and behaviour control are negatively associated with adolescent suicidality and internalising disorders (Gorostiaga et al., 2019). Second, adolescents at risk of suicide are typically cared for at home (Czyz et al., 2018). Therefore, parents play an important logistical role in restricting adolescents’ means of suicide, risk monitoring, and providing emotional support (Czyz et al., 2018). Third, parents are intrinsically motivated to support their children (Yap et al., 2017). Lastly, parenting factors and behaviours associated with adolescent suicidality are more amenable to change in comparison to other risk and protective factors (e.g., familial history of psychopathology or heritability; Wasserman et al., 2021; Yap et al., 2017). Prior research also highlights the importance of parental self-efficacy (to engage with adolescent suicide prevention strategies), showing that higher parental self-efficacy is associated with fewer adolescent suicide-related emergency department admissions at a four-month follow-up (Czyz et al., 2018).

Yet, despite the critical role of parents, most parents caring for a suicidal adolescent report feeling overwhelmed and ill-equipped to support their adolescent experiencing suicidality (Greene-Palmer et al., 2015; Rheinberger, Shand, et al., 2023). Consistently, parents report that there are limited parental resources available and express disappointment in the lack of support from healthcare systems following their adolescent’s suicidal crises (Rheinberger, Shand, et al., 2023; Weissinger et al., 2023). In line with parents’ reports, there is currently no digital parenting intervention that is available to support parents who are caring for a suicidal adolescent. Given that most parents prefer receiving general parenting information through online platforms as opposed to the more traditional face-to-face approach, the lack of digital parenting interventions for adolescent suicidality is particularly concerning (Baker et al., 2017; Metzler et al., 2012). In particular, digital interventions have the potential to help overcome logistical barriers that parents commonly report facing, including scheduling conflicts, transportation, and other accessibility issues (Finan et al., 2018).

While the literature consistently highlights calls for greater parental support, specifically for parents of suicidal adolescents (Calear et al., 2016; Lantto et al., 2023; Rheinberger, Shand, et al., 2023), very little is known about parents’ support needs when caring for a suicidal adolescent. Only one study, to date, has considered parents' support needs in the context of developing an online parenting intervention for parents of suicidal adolescents (Cao et al., 2025). Notably, a key finding of this study was that parents caring for suicidal adolescents needed to feel empowered (Cao et al., 2025). Parent empowerment was conceptualised as the belief that they have a valuable role in preventing their adolescent’s suicide and undertaking the behaviours to do so (Cao et al., 2025). In line with such findings, the field of human-computer interaction has highlighted empowerment as a key factor in designing effective interventions (Schneider et al., 2018). Yet, despite research calling for digital interventions to ‘empower’ its end users, the term ‘empowerment’ remains elusive and challenging to characterise and quantify (Schneider et al., 2018). Further, the concept of ‘empowerment’ may be considered different to differing groups of end users. To date, little is known about how a technological system could be designed to promote parent empowerment in the context of caring for a suicidal adolescent.

Co-design presents as an ideal method to consider how a technological system could be designed to better meet the needs of these parents. Co-design is a participatory research method that aims to engage its intended users and key stakeholders in the planning, design, and evaluation process, thus facilitating a better understanding and meeting the needs of its end users (Blomkamp, 2018; Slattery et al., 2020). Given the overlap in parental factors associated with adolescent internalising disorders and suicidality, a parenting intervention that addresses both appears as a promising path forward. Currently, there is no purely digital parenting intervention that exists for parents of suicidal adolescents, although a digital intervention does exist for parents of adolescents with internalising disorders that has pre-established acceptability, feasibility, and usefulness (Fulgoni et al., 2019; Khor et al., 2022). Thus, leveraging an existing parenting program with pre-established acceptability, feasibility, and usefulness for the parent and their adolescent may expedite the development process.

One such parenting intervention is the Partners in Parenting (PiP) program, which aims to reduce the risk and impact of adolescent depression and anxiety disorders by equipping parents with evidence-based parenting strategies. The Partners in Parenting program is a multi-level, individually tailored, web-based parenting intervention, spanning universal prevention (Level 1) to early intervention of existing clinical-level internalising problems (Level 4). The highest level (Level 4; henceforth referred to as PiP+) combines the online self-directed program with regular one-on-one coaching sessions via video conference (Fulgoni et al., 2019). The coaching component of PiP+ (Level 4) was originally developed to provide higher-intensity support to parents of adolescents with clinical levels of anxiety or depression, who may require additional support to implement recommended strategies from PiP. Parents who complete the PiP+ program receive: 1. evidence-based parenting guidelines (Parenting Strategies Program, 2013), 2. a self-assessment tool (Cardamone-Breen et al., 2017) with individualised feedback on their parenting strengths and areas for further development (Cardamone-Breen et al., 2018), 3. up to nine interactive online modules covering different domains of evidence-based parenting (Fulgoni et al., 2019), and 4. up to 13 video-conferencing sessions with their therapist-coach, occurring weekly or fortnightly (Fulgoni et al., 2019). Although PiP+ targets parenting behaviours with adolescent internalising disorders (e.g., parenting risk and protective factors), some of which are also associated with reducing adolescent suicide risk, PiP+ is not designed for parents of suicidal adolescents.

To best understand how parents can be empowered in their role of caring for a suicidal adolescent requires recognising the broader context in which these experiences unfold. As such, a digital intervention that aims to empower parents should consider the lived experience of these parents through a multifaceted lens, encompassing the viewpoints of the parent, adolescent, and healthcare systems supporting the adolescent’s mental health (Killackey, 2023). It has been argued that recognising the diversity of perspectives from different key stakeholders can increase the likelihood that interventions will have more meaningful outcomes (Killackey, 2023).

The study aims to co-design how PiP+ could be adapted to empower parents in caring for a suicidal adolescent, based on the perspectives of parents, young people, and professional experts. The findings will explore how empowerment could be embedded in the technological system (i.e., PiP+, which incorporates both computer and human elements)—that is, how parent empowerment could be embedded in both the online modules and digitally-mediated coaching sessions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

Prior to commencing recruitment and any engagement with participants, ethical approval was sought and granted by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (ID #28055). As the study was open for young people who were under the age of 18 to participate, both the parent and the young person were asked to review the explanatory statement written for young people under the age of 18. If both agree, the parent must provide informed consent. Therefore, prior to participation, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Recruitment and Participants

Three groups of participants were invited to co-design workshops that is, parents, young people, and experts in youth mental health/suicide prevention. The following groups were chosen as they were considered the key stakeholders in adolescent suicide prevention, parent-adolescent relationships, and the adolescent’s recovery.

We recruited participants by sharing flyers with professional networks, online community noticeboards, and social media sites. We also invited parents, young people, and experts who participated in a previous research study on understanding the lived experience of parenting a suicidal adolescent (Cao et al., 2025) and who provided consent to be contacted for future research.

All participants needed to live in Australia, speak English and have stable internet access. Parent participants must have lived experience of parenting an adolescent (aged 12-18) who experienced suicidal thoughts or behaviours. Young people (aged 15-25) were eligible if they had lived experience of suicidal thoughts or behaviours when they were adolescents (aged 12-18). Lastly, professionals were eligible if they had over 3 years of experience working in the field of youth mental health and suicide prevention in either clinical or research roles (henceforth referred to as experts). Each participant was reimbursed

$40 AUD per hour. While young people under the age of 18 were eligible to participate, no participants under the age of 18 expressed interest. Therefore, parental consent was not required.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants. Notably, to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, no stakeholders held additional relationships with one another.

2.3. Data Collection

The research team developed co-design workshops and respective activities specific to each participant group. The co-design workshops focused on how parents could be empowered to prevent their adolescent’s suicide, and moreover, how the findings could be translated to creative technological solutions in a digital parenting intervention to address the topic of adolescent suicide prevention. The researchers decided to develop and run co-design workshops separately for each stakeholder group. This decision was made to ensure participants felt safe to provide their views freely and to prevent any perceived power imbalances between stakeholder groups unduly biasing or limiting the information shared. Consequently, four sets of co-design workshops were developed as described below. Workshops were held in November and December 2021, each lasted 1 to 2.5 hours, were conducted using Zoom videoconferencing software, and used screen share to show participants a Google Slides deck. The facilitator used text boxes to annotate the slides with participant insights in real time.

2.3.1. First Co-Design Workshop with Parents: Enablers and Barriers to Parental Empowerment

Two workshops were conducted – one group workshop with three parents, and an individual workshop due to logistical constraints. This first set of co-design workshops aimed to understand how an intervention could be designed to enable empowerment at different stages of supporting a suicidal adolescent, exploring potential enablers and barriers to empowerment. As parents with lived experience of supporting a suicidal adolescent commonly report feeling helplessness, guilt, and self-blame (Greene-Palmer et al., 2015), we intentionally focused the workshop on a vignette of a parent who was seeking the parent participants’ lived experience advice to support their suicidal adolescent. Vignettes can encourage parents to afford themselves the same kindness they would to a friend and provide a third-party perspective, which is often less self-critical (Germer & Neff, 2013).

The co-design activity asked parents to create a “magic machine” that would empower their hypothetical friend who was caring for a suicidal adolescent (see

Figure 1), thus exploring the enablers of parent empowerment. The magic machine activity encourages participants to be imaginative and limitless in their design suggestions (Almohamed et al., 2020; Andersen & Wakkary, 2019). Ultimately, this approach aimed to help parents draw from a position of empowerment to problem-solve rather than a position of helplessness, guilt, and distress. These workshops also explored emotional enablers and barriers to parental empowerment by asking parents to indicate what emotions they thought their hypothetical friend would be feeling at different stages of supporting their suicidal adolescent (see

Figure 1).

2.3.2. Co-Design Workshop with Young People: The Acceptability of Parent Empowerment in the Context of Suicide Prevention

After the initial parent workshops, four separate individual co-design workshops with adolescent stakeholders were conducted. These workshops were conducted separately as all young people but one indicated that their preference was to engage individually. The focus of these workshops was to explore what would be the most helpful and acceptable ways for parents to support their adolescents experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviours.

Similar to the parent workshops described in Section 2.4.1 we wanted young people to draw their lived experience from a place of empowerment, as opposed to distress and helplessness. Thus, we provided young people with a vignette and asked them to imagine being a radio host who had overcome their mental health challenges and were now providing advice to an imaginary parent experiencing difficulties in supporting their adolescent facing suicidality. We asked young people to provide advice on how parents could build a communicative relationship with their adolescents while monitoring for signs of suicidality in ways that would be deemed acceptable.

2.3.3. Co-Design Workshop with Experts: Feasibility of a Therapist-Assisted Online Parenting Program to Support Parent Empowerment

Following workshops with young people, a group co-design workshop was conducted with four experts who were all clinicians and researchers in youth mental health or suicide prevention. The focus of this workshop was to explore how digital, therapist-assisted parenting interventions could be adapted to empower parents while considering systemic factors (e.g., how parents can be supported to navigate the healthcare systems, school systems, and broader family dynamics, including siblings). Experts were considered well-placed to provide suggestions on navigating the aforementioned systems in ways that would empower parents.

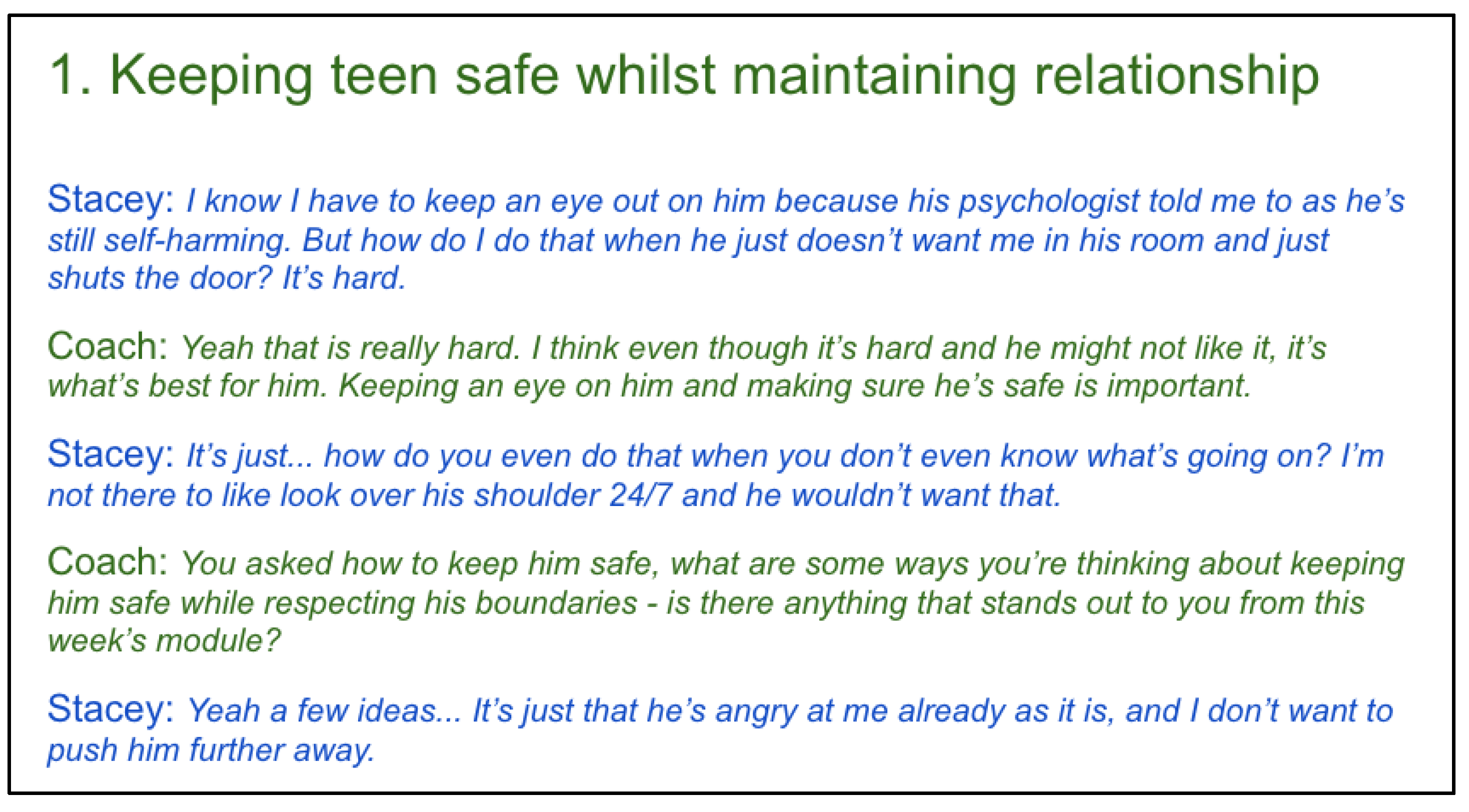

As such, experts were provided with the context of the PiP+ program which described what components parents would receive (i.e., online modules and coaching sessions). Experts were then presented with four vignettes of coaching sessions transcriptions between a parent and coach, and were asked how they would supervise the PiP+ coach whose aim is to empower parents of suicidal adolescents when facing these systemic barriers (see

Figure 2). Such systemic barriers focused on how parents can monitor their adolescent’s safety while maintaining the relationship with the adolescent, supporting parents to find their own mental health supports, if and how parents should communicate with the adolescent’s care team (e.g. psychologists, teachers), and how to navigate changes in the family dynamic with siblings when one adolescent is experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviours. Consequently, the facilitator asked experts questions such as "what constructive feedback would you give the PiP+ coach to support this dilemma?" and "How would you have dealt with this scenario instead?".

2.3.4. Final Co-Design Workshop with Parents: Sense-Checking Themes of Parental Empowerment

We invited all four parents from the first set of parent co-design workshops to participate in the final parent workshop; three participants agreed to participate. The final participants of this group co-design workshop were mothers aged 39 to 52 (M = 47.00, SD = 5.72).

The final co-design workshop aimed to sense-check the identified sub-themes triangulated from all sets of workshops conducted previously. We wanted to check with parents and explore whether the identified sub-themes were reflective of parents’ lived experiences and if they were considered important to parent empowerment when caring for a suicidal adolescent. In addition to sense-checking the sub-themes identified (data analysis procedure described in Section 2.5), the research team had extrapolated digital design solutions that may address the needs identified by themes developed from parents, young people, and experts in the prior workshops. These identified sub-themes and extrapolated features in a digital, therapist-assisted, parenting intervention are presented in

Table 2. For example, the identified sub-theme of ‘self-efficacy’ was conceptualised as a digital feature of a personalised plan that parents can use to prevent their adolescent’s suicide.

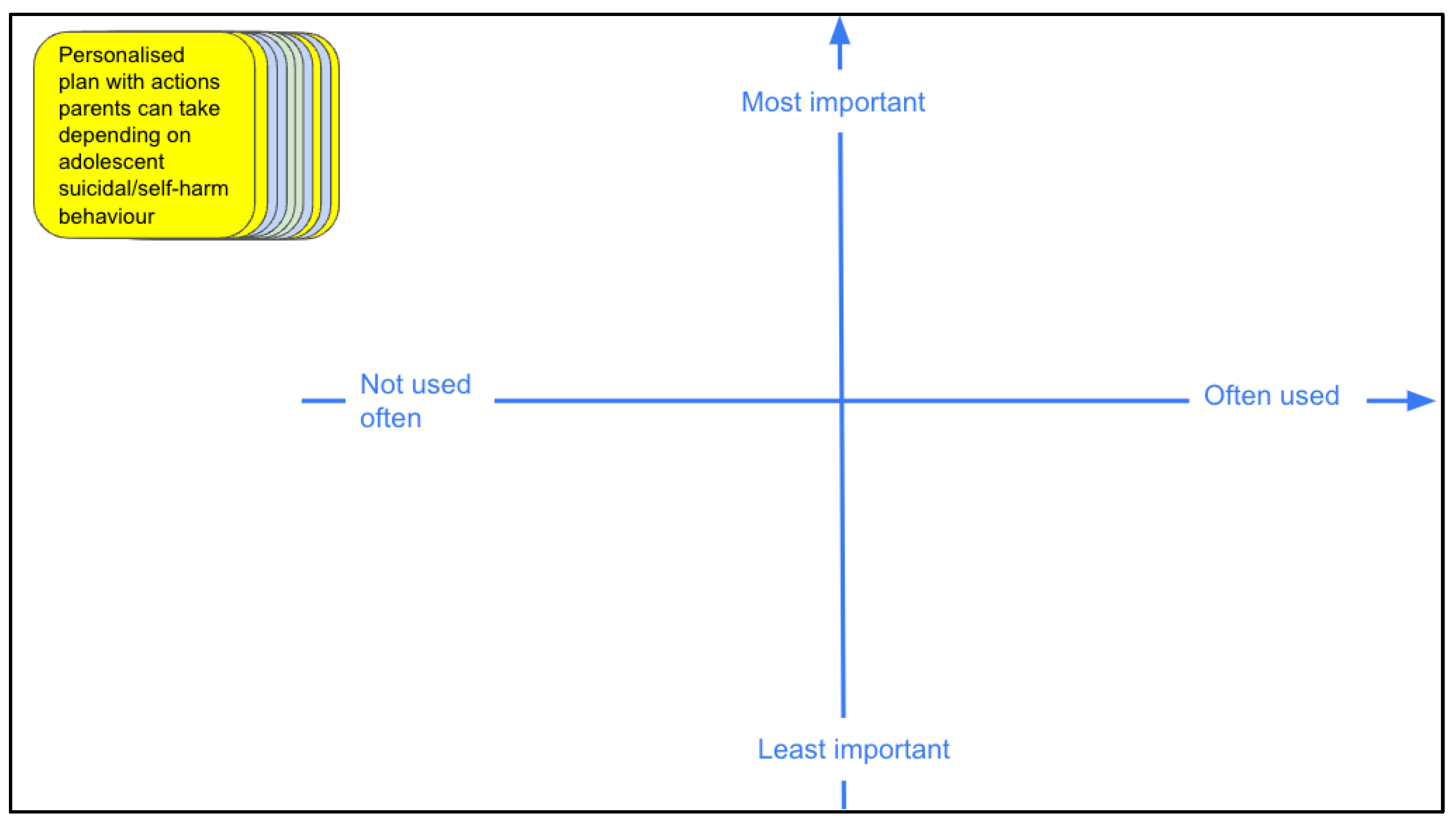

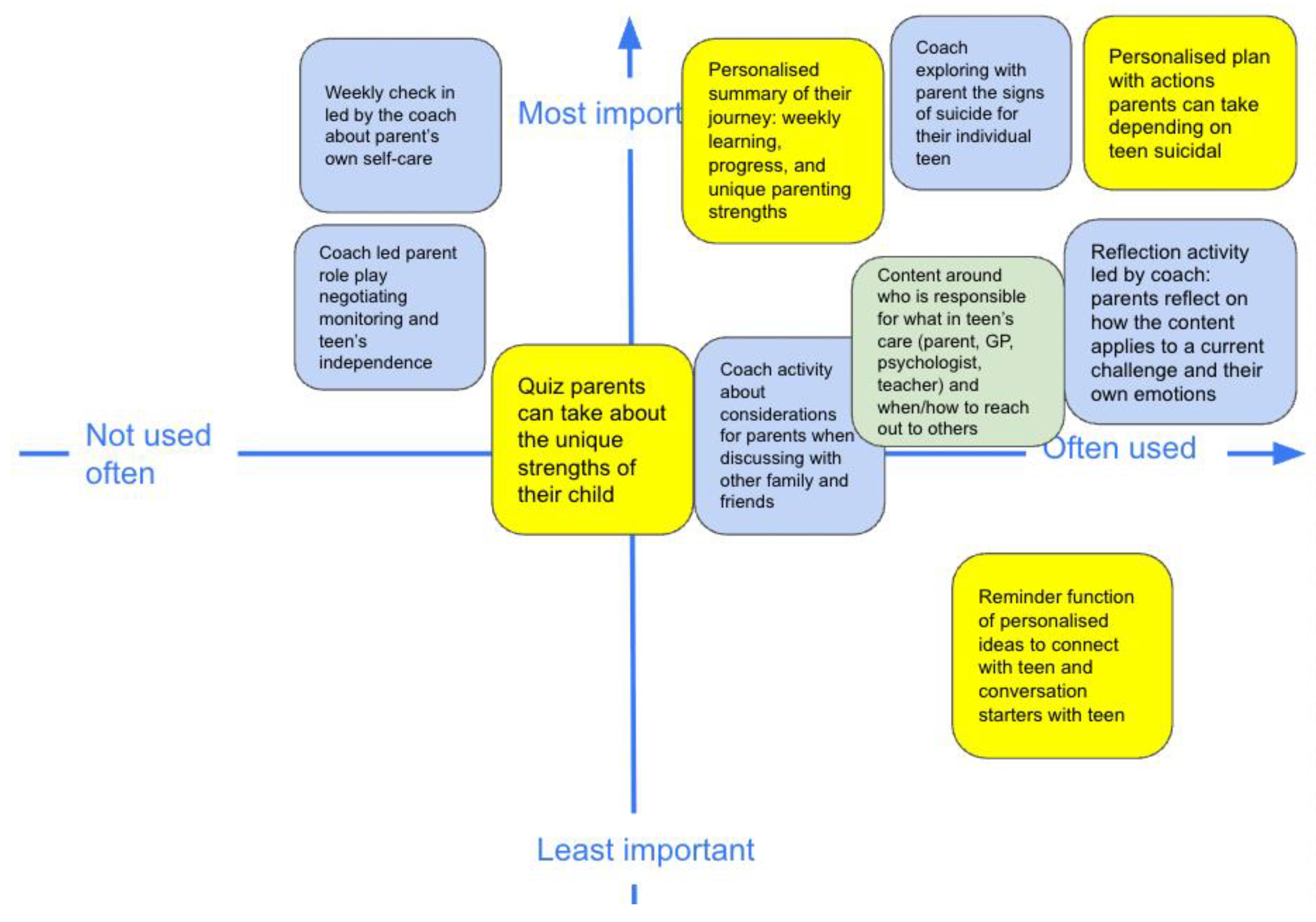

We listed each feature on a virtual "post-it" note, presented in

Figure 3. Parents were asked to sort the features based on importance and usability by placing the notes on a two-dimensional axis (axis 1: most important to least important, axis 2: most usable to least usable). During the workshop, we asked parents if and how the feature mapped onto the identified theme (e.g., "what does this feature mean for a parent’s feelings of self-efficacy?"). Additionally, we asked specific follow-up questions to consider how each feature could be implemented (e.g., "how would this feature work best?").

2.4. Data Analysis

All interviews were initially transcribed by a trusted third-party Artificial Intelligence software program, Descript version 7.0.4 for Mac (Descript, San Francisco, CA; see

https://www.descript.com/). A.C. manually corrected the interviews for accurate verbatim transcription. The first author AC and author GB familiarised and read through the transcripts, integrating data across all workshops to identify themes for empowering parents in supporting a suicidal adolescent in acceptable and feasible ways. AC and GB used affinity mapping to display the data of each stakeholder group and arrange the data into sub-themes. For each participant group, key sub-themes were developed and integrated into an overall thematic map with three overarching themes triangulating the perspectives of the three stakeholder groups. All themes and sub-themes were presented to the research team with key quotes and iteratively discussed until the final themes were agreed upon.

3. Results

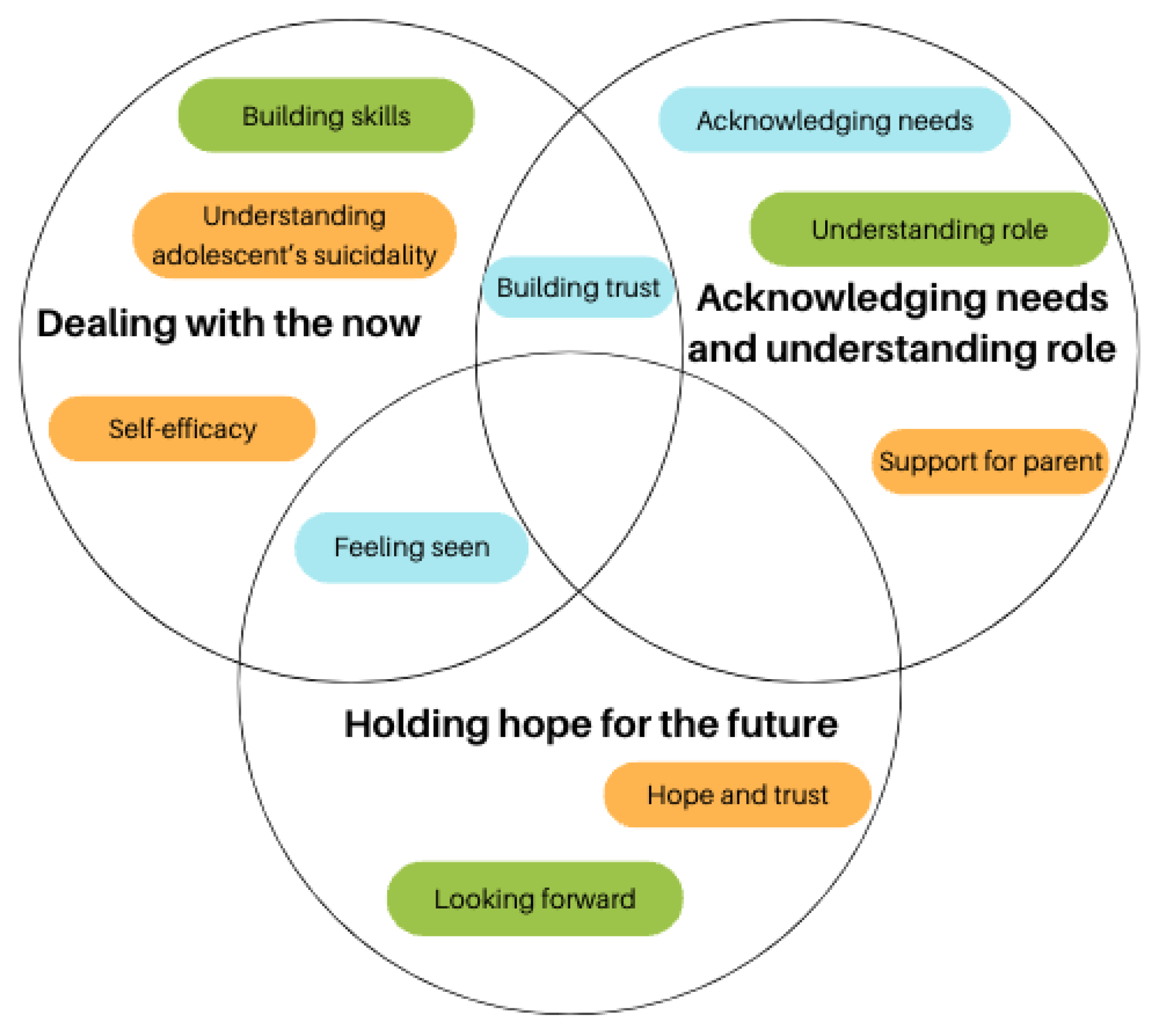

Three overarching themes were developed upon triangulating perspectives of parents, young people and experts: 1. Dealing with the now, 2. Acknowledging needs and understanding their role, and 3. Holding hope for the future. These overarching themes represent the commonalities across all stakeholder groups. Additionally, there were 10 sub-themes identified, which reflect unique insights specific to each stakeholder group. Some sub-themes intersect and overlap with other themes, reflecting the interconnected nature of the findings.

Figure 4 presents a thematic map to visually represent the relationship between the themes and sub-themes.

3.1. Dealing with the Now

For parents to feel empowered, stakeholders identified that parents need to acquire and draw upon specific skills and knowledge during a suicidal crisis (i.e., the acute state which precedes a suicide attempt; Rheinberger, Baffsky, et al., 2023). Five sub-themes were identified in the overarching ‘dealing with the now’ theme and are described with illustrative quotes below. These sub-themes include skills, knowledge, or beliefs that empower parents to support their suicidal adolescent in the moment of a crisis.

3.1.1. Self-Efficacy

For parents to be able to acquire and draw upon specific skills and knowledge while their adolescent is suicidal, parents described that it was important for them to have a sense of confidence that they can support their adolescent. Parents described that without such confidence, it would be challenging for them to be able to draw upon specific suicide prevention skills and knowledge. As one parent described,

[The magic machine] would give Stacy [the parent in the vignette] the confidence to just broach the subject with Trevor [the adolescent in the vignette]. It would give her all the vocabulary to use when she's having discussions with him… it'd give her confidence to implement what she's learned (Parent 4).

3.1.2. Understanding Their Adolescent’s Suicidality

Further, parents described that for them to be able to engage in skills and knowledge related to adolescent suicide prevention when their adolescent is experiencing a suicidal crisis, they need to understand why their adolescent is suicidal, and what are the signs of escalating suicidal thoughts and behaviours specific to their own adolescent.

(I’d like to) understand what’s underlying that behaviour. So, if they’re staying in their room what’s underlying that, is it because they’re feeling terrible about themselves and don’t want to talk to anyone and going down a spiral of negative thinking or are they just enjoying their time. (Parent 1)

3.1.3. Building Skills

Experts described that for parents to be able to support their adolescent during a suicidal crisis, they need to be supported to develop skills to respond in line with evidence-based best-practice suicide prevention strategies.

It should be quite clear that this is the goal of our work. This is not psychotherapy. This is coaching, which is focused on developing [the parents’] skills (Expert 2)

3.1.4. Building Trust

Young people described that for parents to be able to successfully implement suicide prevention strategies, there first needs to be a sense of trust between the parent and adolescent. They highlighted the importance that parents can be understanding of what their adolescent is experiencing, noting that without this sense of being understood, they were less likely to trust their parent’s advice, even when well-intentioned. As such, building trust in their parent’s emotional insights is essential for young people to be more receptive of accepting help during their suicidal crises.

I don’t think I trusted her to know really what was going on. And so then I did not trust any of her advice. If you don’t have a relationship where like, you’re both like trusting each other, then it’s really hard to then trust things you’re telling me to do. (Young person 3)

3.1.5. Feeling Seen

Young people described that for parents to be able to successfully implement suicide prevention strategies, and for their adolescents to be more receptive to such strategies, parents need to understand their adolescents’ difficulties in the context of who they are and their current experiences. Young people indicated that they would be less open to seeking help and receiving support from their parents if they considered that their parents viewed them as being ‘broken’ or in need of ‘fixing’.

(Parents should be) seeing (their adolescent) like a person and, and like understanding they have feelings. . . it can’t just be like, ’I want to fix my broken son’. . . (the adolescents) are going to like be like, ‘oh, so you think there’s like something wrong with me. Great. Like, wow, news flash, there is something wrong with me’. . . But if the intention is like, “oh, you know, I really want to support you through this so I understand what you’re going through”. Um, they’ll feel that too. (Young Person 2)

3.2. Acknowledging Needs and Understanding Role

All three stakeholder groups identified the need for parents to acknowledge their needs and roles to foster parental empowerment. Young people and experts emphasised the importance of parents acknowledging their unique role within the adolescent’s care team (e.g., that parents must coordinate the care for their adolescents but are not their health professionals) and prioritising self-care. Parents acknowledged the value of engaging in self-care, having adequate personal support (e.g., from friends and family), and having access to professional support systems.

3.2.1. Support for Parent

Parents described that to feel empowered to care for a suicidal adolescent, they need to be able to draw upon professional and personal support for themselves. Parents discussed such needs for support given that their consistent caretaking role can take a toll on their well-being.

They’re still a child that needs us to be strong, which we can’t do all the time. And so we also need to have our own support and friends to help us when we’re struggling with all of that ourselves. (Parent 1)

3.2.2. Understanding Role

Experts described how parents need to be supported and to understand their role in caring for their adolescents to help them feel empowered. They discussed that at times, parents can feel that they are solely responsible for their adolescent’s health, education, and well-being. Therefore, parents need to understand that they are part of a team and can leverage the appropriate expertise of the adolescent’s care team (e.g., health professionals) to provide support.

Their role is around support and being there rather than taking the control completely... For the parents to feel like. . . it’s not just them. It’s who else? Who else can the young person talk to? Who else can they get support from? So, it’s more of a shared team approach. (Expert 1)

3.2.3. Acknowledging Needs

Young people described the importance of parents reflecting and acting upon their own needs as a form of parent empowerment when caring for a suicidal adolescent. Further, young people described that when parents acknowledge their own needs and self-care, they also in turn model this skill to their adolescent.

[I’d like her to] like self-care, like, ‘Oh, Mum's actually taking care of herself. That's cool. Maybe I should do a little bit myself or something’... Even modelling that behaviour is so important. (Young person 2)

3.2.4. Building Trust

Young people described how parents must trust the young person’s care team to uphold their duty of care in order to feel empowered in their role of supporting their adolescent.

I was already connected with other supports that I was like, well, I’m already talking to all these people and I already am trying to work on all these things. You don’t have to be breathing down my neck to like work out what’s wrong or like work out if something has changed. Like someone else will work that out, you don’t need to work that out. (Young person 3)

3.3. Holding Hope for the Future

Lastly, all three stakeholder groups identified that to foster empowerment within parents, there must be hope that the adolescent’s suicidal thoughts and behaviours can be overcome. If parents can hold hope for their adolescent’s recovery, stakeholders believe that parents are more likely to be empowered in their role of caring for their suicidal adolescent.

3.3.1. Hope and Trust

Parents described that to feel a sense of empowerment when engaging in a parenting intervention, parents need to hold hope that with time their adolescent will eventually recover and have trust that the parenting strategies they learn will support their recovery.

[Parents need to] understand that it’s not necessarily going to change overnight… but you still have to keep trying and you still have to keep giving that support… you have to sort of remain hopeful. (Parent 4)

3.3.2. Feeling Seen and Looking Forward

Young individuals described the importance of parents recognising the current state and difficulties faced by adolescents (i.e., feeling seen). Yet, they equally emphasised that parents should maintain hope that recovery is possible although it may require time and continued effort (i.e., looking forward).

It’s like having enough faith that you’ll make it to the end but being realistic with where you’re at. . . Of course, like what [the adolescent] is going through is tough and is really, really like worrying. I’d be really worried. But this is, this is the long haul. And then also helping to understand that after you’re able to have a. . . having opened up, that’s not the end. Like there’s more to it. (Young Person 2)

Echoing young people’s descriptions, experts discussed that for parents to feel empowered, they need to believe that their adolescent’s suicidal thoughts and behaviours can be overcome by the parent supporting the adolescent holistically (i.e., not only focusing on suicidality).

So I think, yeah, I think there’s something here around who is, this is still your child. This is still, this person is going through a difficult time with all these things going on. So how do we keep seeing them and how do we keep hearing and holding out for who they are and the hope for the future and not get too fixated on the safety on its own. (Expert 1).

3.4. Results of Sense-Checking Activity

The final workshop aimed to validate sub-themes generated across all prior parent, young people, and expert workshops and to elicit feedback on the preliminary design features mapped to those themes (see Section 2.5 for and

Table 2 for the digital features).

The proposed digital features (see

Table 2) were mapped onto a virtual two-axis board (see

Figure 5 for results of the activity). The features rated as both important and highly usable included a personalised safety planning tool (mapped to self-efficacy sub-theme), the coach exploring with parent the signs of suicide for their adolescent (understanding adolescent’s suicidality sub-theme), and reflection activity led by coach: parents reflect on how the content applies to a current challenge and their own emotions (mapped to building skills sub-theme). Notably, no features were described by parents as ones that will not be used often and are not important, thus affirming the relevance of the co-designed sub-themes and features.

4. Discussion

This study illustrated the barriers and facilitators to parental empowerment in the context of caring for a suicidal adolescent by triangulating the perspectives of parents, young people, and experts. Following these findings, features which could be integrated to adapt a digital, therapist-assisted, parenting intervention were extrapolated. Our co-design workshops revealed that to empower parents of adolescents at risk of suicide, the design of an intervention should address three key themes: (1) "Dealing with the now," (2) "Acknowledging needs and understanding their role," and (3) "Holding hope for the future". To operationalise these themes, we propose specific design adaptations to an existing parenting program (PiP+) by leveraging technology-mediated support (i.e., parent-to-coach and parent-to-parenting program interactions), see

Table 2 for list of specific adaptations.

Through the ‘dealing with the now’ theme, it was emphasised that for parents to feel empowered, they needed to acquire and draw upon specific skills and knowledge during a suicidal crisis. Yet to do so, they must first understand their adolescent’s suicidality, develop specific skills, have the confidence to use these skills, and approach their adolescent with an open and trusting attitude. Further, it was emphasised that to ‘deal with the now’, the skills and knowledge parents acquire must be tailored to the unique circumstances of their adolescent. PiP+ would therefore need technological adaptations which would support parents to develop suicide prevention-specific skills. Such adaptations could involve supporting parents to personalise for themselves a digital action plan that they can refer to when their adolescent is suicidal; provide digital module content to understand the signs of adolescent suicidality, or adapt coaching sessions to focus on a parent’s emotional distress associated with caring for a suicidal adolescent and how this can be managed. As such, to ‘deal with the now’, there is a need for highly personalised support which lends itself well to an intervention such as PiP+ given that it combines the online self-directed program presenting evidence-based, actionable strategies with regular coaching sessions via video conference. Following from our findings, it seems unlikely that an untailored parenting intervention without coaches (i.e., a fully self-guided online intervention) would adequately meet the needs of this parent group. The digital features we suggest require a human element (i.e., a coach) to support parents with the tailoring of knowledge and skill implementation.

The ‘acknowledging needs and understanding role’ theme highlighted that to empower parents, they should not feel alone in the care of their adolescent and that parents should reflect upon their unique role within the context of the adolescent’s care team. Prior research has demonstrated that parents often engage with their children in multiple roles and need to shift their role depending on their child's ever-changing needs; thus, technology should support this process (Sadka et al., 2018). Indeed, some guidelines has even been developed to support parents caring for children in the context of their child experiencing trauma to switch between the role of peer, supporter, and carer in technological interventions (Ahmadpour et al., 2023). However, our findings challenge these principles, continual role-switching can lead to feelings of isolation, overwhelm, and helplessness for parents caring for suicidal adolescents. While acknowledging the need for parents to assume diverse roles, we suggest that digital features in PiP+ should be developed to support parents to recognise and reflect upon their unique role and reach out to other supports as required (e.g., clinicians, mental health professionals). As such, to adapt PiP+ there should be psycho-education content in the online modules about the role of each individual in the adolescent’s care team and content or activities to ensure the parent’s self-care to prevent feelings of helplessness and overwhelm. Further, the program may also benefit from including a guided check-in between the coach and the parent about their self-care.

Lastly, the ‘holding hope for the future’ theme emphasises that to empower parents of suicidal adolescents with a digital intervention, there must be a belief that the adolescent will eventually recover and that the recommended parenting strategies will support their recovery. Consequently, PiP+ should be adapted to include digital features that emphasise parents’ progress across time and provide reflective mechanisms for parents to self-actualise their “gains” from engaging in the program. PiP+ could benefit from including a digital feature that allows parents to record and visualise their weekly learnings, progress, and strengths to foster greater parental empowerment. Such a record could be used collaboratively between parent and coach, as coaches can guide parents’ discoveries in ways to emphasise that recovery is possible. The findings of including self-narrative reflection are in line with educational research, which suggests that when students are asked to write a narrative where they can reflect upon themselves, their experiences, and learnings, this can support them to reframe what was previously perceived as difficult experiences (Coughlan & Lister, 2022). When students engage in self-narrative reflection, they no longer view perceived failures as setbacks, but rather opportunities for learning and growth (Coughlan & Lister, 2022).

The current study's findings should be considered within the context of certain limitations. First, as the primary objective was to capture the breadth of perspectives about how parents can be more empowered when caring for a suicidal adolescent, we engaged with multiple stakeholder groups. A compromise, however, had to be made in terms of the smaller sample sizes within each stakeholder group, due to resource constraints. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to the experiences and perspectives of all parents, young people, and experts. Second, the research team extrapolated the design features for the intervention by interpreting and extrapolating themes identified from prior workshops. Although these features were reviewed (i.e., sense-checked) by parents to confirm they align with the original themes, this approach carries a risk of confirmation bias - namely that the researcher’s interpretations of the participants’ responses may have shaped some of these features. Further, another limitation of this study is the potential for selection bias due to the recruitment of participants who had previously taken part in a related study (Cao et al., 2025) and had consented to future contact. These individuals may have had particularly strong motivations for participation, a higher level of engagement with research, or more positive or negative experiences that made them more likely to contribute again. As a result, the perspectives captured may not fully represent the broader population of parents, young people, or experts who have experience with adolescent suicidality but have not engaged in research. Future research should aim to build on such findings by engaging larger and more diverse groups to validate these proposed intervention features. Further, co-design methods could allow stakeholders to be able to generate multiple technological solutions as opposed to responding to the researcher-derived solutions.

5. Conclusions

In sum, our findings explored how a digital intervention (PiP+) can be adapted to empower parents of adolescents experiencing suicidality from co-designed digital features. Our co-designed findings suggest that to empower parents of suicidal adolescents, there must be considerations of how to support parents to build suicide prevention skills and knowledge within their own parenting context, to have hope for the future, and to understand their role and their own needs. We also provided specific technological features that would foster such themes. To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no parenting intervention that has been co-designed to empower parents caring for adolescents experiencing suicidality. As such, these findings provide a preliminary step in considering how digital interventions and what features could be developed to better support parents who are caring for an adolescent experiencing suicidality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., L.W., G.M., M.C.B., G.B., J.S., C.S., T.B., R.M., P.O. and M.B.H.Y.; Formal analysis, A.C. and G.B.; Funding acquisition, M.B.H.Y.; Methodology, A.C., L.W., G.M., G.B., J.S., C.S., J.X., P.O. and M.B.H.Y.; Project administration, A.C., G.B., C.S. and J.X.; Supervision, L.W., G.M., M.C.B., J.S., P.O. and M.B.H.Y.; Visualization, D.B.; Writing – original draft, A.C. and L.W.; Writing – review & editing, L.W., G.M., M.C.B., G.B., J.S., C.S., J.X., D.B., T.B., R.M., P.O. and M.B.H.Y.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge that this research was funded by Suicide Prevention Australia Limited for a Suicide Prevention Australia Innovation Grant. Alice Cao is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship for their candidature in the Doctor of Psychology (Clinical Psychology) at Monash University. The contents of the published material are the responsibility of the relevant authors and have not been approved or endorsed by Suicide Prevention Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number #28055, approval date 15/06/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

A summary of the data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, M.B.H.Y. The data are not publicly available owing to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants in this study and thank them for sharing their expertise and perspectives.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PiP |

Partners in Parenting |

| PiP+ |

The highest level of the Partners in Parenting program which combines the online self-directed program with regular one-on-one coaching sessions via video conference |

| PiP-SP+ |

Partners in Parenting - Suicide Prevention |

References

- Ahmadpour, N., Loke, L., Gray, C., Cao, Y., Macdonald, C., & Hart, R. (2023). Understanding how technology can support social-emotional learning of children: A dyadic trauma-informed participatory design with proxies. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Almohamed, A., Zhang, J., & Vyas, D. (2020). Magic Machines for Refugees. Proceedings of the 3rd ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies, 76–86. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K., & Wakkary, R. (2019). The Magic Machine Workshops: Making Personal Design Knowledge. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Baker, S., Sanders, M. R., & Morawska, A. (2017). Who uses online parenting support? A cross-sectional survey exploring Australian parents’ internet use for parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(3), 916–927. [CrossRef]

- Blomkamp, E. (2018). The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(4), 729–743. [CrossRef]

- Calear, A. L., Christensen, H., Freeman, A., Fenton, K., Busby Grant, J., van Spijker, B., & Donker, T. (2016). A systematic review of psychosocial suicide prevention interventions for youth. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(5), 467–482. [CrossRef]

- Cao, A., Melvin, G. A., Wu, L., Cardamone-Breen, M. C., Salvaris, C. A., Olivier, P., Jorm, A. F., & Yap, M. B. H. (2025). Understanding the lived experience and support needs of parents of suicidal adolescents to inform an online parenting programme: Qualitative study. BJPsych Open, 11(2), e61. [CrossRef]

- Cardamone-Breen, M. C., Jorm, A. F., Lawrence, K. A., Mackinnon, A. J., & Yap, M. B. H. (2017). The Parenting to Reduce Adolescent Depression and Anxiety Scale: Assessing parental concordance with parenting guidelines for the prevention of adolescent depression and anxiety disorders. PeerJ, 5, e3825. [CrossRef]

- Cardamone-Breen, M. C., Jorm, A. F., Lawrence, K. A., Rapee, R. M., Mackinnon, A. J., & Yap, M. B. H. (2018). A Single-Session, Web-Based Parenting Intervention to Prevent Adolescent Depression and Anxiety Disorders: Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(4), e148. [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, T., & Lister, K. (2022). Creating Stories of Learning, for Learning: Exploring the Potential of Self-Narrative in Education with ‘Our Journey.’ Proceedings of the 14th Conference on Creativity and Cognition, 526–531. [CrossRef]

- Czyz, E. K., Horwitz, A. G., Yeguez, C. E., Ewell Foster, C. J., & King, C. A. (2018). Parental self-efficacy to support teens during a suicidal crisis and future adolescent emergency department visits and suicide attempts. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(sup1), S384–S396. [CrossRef]

- Finan, S. J., Swierzbiolek, B., Priest, N., Warren, N., & Yap, M. (2018). Parental engagement in preventive parenting programs for child mental health: A systematic review of predictors and strategies to increase engagement. PeerJ, 6, e4676. [CrossRef]

- Fortune, S., Sinclair, J., & Hawton, K. (2008). Help-seeking before and after episodes of self-harm: A descriptive study in school pupils in England. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 369. [CrossRef]

- Fulgoni, C. M. F., Melvin, G. A., Jorm, A. F., Lawrence, K. A., & Yap, M. B. H. (2019). The Therapist-assisted Online Parenting Strategies (TOPS) program for parents of adolescents with clinical anxiety or depression: Development and feasibility pilot. Internet Interventions, 18, 100285. [CrossRef]

- Germer, C. K., & Neff, K. D. (2013). Self-Compassion in Clinical Practice: Self-Compassion. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(8), 856–867. [CrossRef]

- Gorostiaga, A., Aliri, J., Balluerka, N., & Lameirinhas, J. (2019). Parenting styles and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3192. [CrossRef]

- Greene-Palmer, F. N., Wagner, B. M., Neely, L. L., Cox, D. W., Kochanski, K. M., Perera, K. U., & Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M. (2015). How parental reactions change in response to adolescent suicide attempt. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(4), 414–421. [CrossRef]

- Hallford, D. J., Rusanov, D., Winestone, B., Kaplan, R., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., & Melvin, G. (2023). Disclosure of suicidal ideation and behaviours: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Clinical Psychology Review, 101, 102272. [CrossRef]

- Ivey-Stephenson, A. Z., Demissie, Z., Crosby, A. E., Stone, D. M., Gaylor, E., Wilkins, N., Lowry, R., & Brown, M. (2020). Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A. F., Wright, A., & Morgan, A. J. (2007). Where to seek help for a mental disorder? Medical Journal of Australia, 187(10), 556–560. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J. C., Graaf, R. D., Gasquet, I., Girolamo, G. D., Gluzman, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Kawakami, N., Karam, A., Levinson, D., Medina, M. E., Browne, M. A. O., Posada-Villa, J., Stein, D. J., Tsang, C. H. A., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., … Üstün, T. B. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry, 6(3), 168–176.

- Khor, S. P. H., Fulgoni, C. M., Lewis, D., Melvin, G. A., Jorm, A. F., Lawrence, K., Bei, B., & Yap, M. B. H. (2022). Short-term outcomes of the Therapist-assisted Online Parenting Strategies intervention for parents of adolescents treated for anxiety and/or depression: A single-arm double-baseline trial. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 56(6), 695–708. [CrossRef]

- Killackey, E. (2023). Lived, loved, laboured, and learned: Experience in youth mental health research. The Lancet Psychiatry, 10(12), 916–918. [CrossRef]

- Lantto, R., Lindkvist, R.-M., Jungert, T., Westling, S., & Landgren, K. (2023). Receiving a gift and feeling robbed: A phenomenological study on parents’ experiences of Brief Admissions for teenagers who self-harm at risk for suicide. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17(1), 127. [CrossRef]

- Marraccini, M. E., Pittleman, C., Griffard, M., Tow, A. C., Vanderburg, J. L., & Cruz, C. M. (2022). Adolescent, parent, and provider perspectives on school-related influences of mental health in adolescents with suicide-related thoughts and behaviors. Journal of School Psychology, 93, 98–118. [CrossRef]

- Metzler, C. W., Sanders, M. R., Rusby, J. C., & Crowley, R. N. (2012). Using consumer preference information to increase the reach and impact of media-based parenting interventions in a public health approach to parenting support. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 257–270. [CrossRef]

- Parenting Strategies Program. (2013). How to prevent depression and clinical anxiety in your teenager: Strategies for parents. beyondblue.

- Rheinberger, D., Baffsky, R., McGillivray, L., Zbukvic, I., Dadich, A., Larsen, M. E., Lin, P.-I., Gan, D. Z. Q., Kaplun, C., Wilcox, H. C., Eapen, V., Middleton, P. M., & Torok, M. (2023). Examining the feasibility of implementing digital mental health innovations Into hospitals to support youth in suicide crisis: Interview study with young people and health professionals. JMIR Formative Research, 7, e51398. [CrossRef]

- Rheinberger, D., Shand, F., Mcgillivray, L., Mccallum, S., & Boydell, K. (2023). Parents of adolescents who experience suicidal phenomena—A scoping review of their experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6227. [CrossRef]

- Sadka, O., Erel, H., Grishko, A., & Zuckerman, O. (2018). Tangible interaction in parent-child collaboration: Encouraging awareness and reflection. Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 157–169. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, H., Eiband, M., Ullrich, D., & Butz, A. (2018). Empowerment in HCI - A Survey and Framework. Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Slattery, P., Saeri, A. K., & Bragge, P. (2020). Research co-design in health: A rapid overview of reviews. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, D., Carli, V., Iosue, M., Javed, A., & Herrman, H. (2021). Suicide prevention in childhood and adolescence: A narrative review of current knowledge on risk and protective factors and effectiveness of interventions. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 13(3), e12452. [CrossRef]

- Weissinger, G. M., Evans, L., Catherine, Winston-Lindeboom, P., Ruan-Iu, L., & Rivers, A. S. (2023). Parent experiences during and after adolescent suicide crisis: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 32(3), 917–928. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/131056.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Mental health of adolescents. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

- Yap, M. B. H., Lawrence, K. A., Rapee, R. M., Cardamone-Breen, M. C., Green, J., & Jorm, A. F. (2017). Partners in Parenting: A multi-level web-based approach to support parents in prevention and early intervention for adolescent depression and anxiety. JMIR Mental Health, 4(4), e59. [CrossRef]

- Yap, M. B. H., Reavley, N., & Jorm, A. F. (2013). Where would young people seek help for mental disorders and what stops them? Findings from an Australian national survey. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1–3), 255–261. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).