Submitted:

05 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Intelligence System in Schools

2.1. Knowledge-Based ES and Other Intelligent Systems

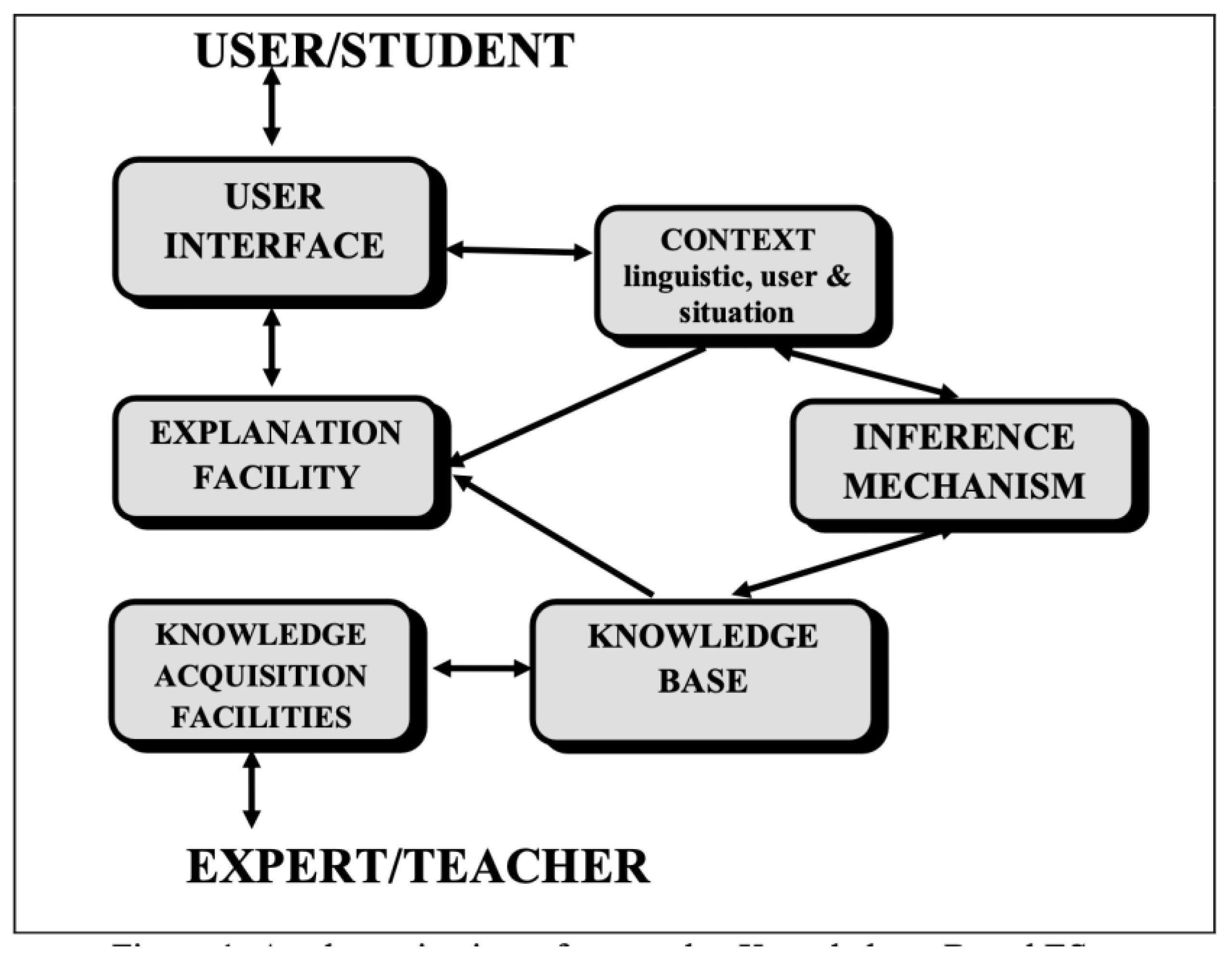

- Of the behavior of the problem domain,

- Context, in all three areas in Linguistic context and natural language processing (NLP, in users’ context, which considers users’ data as past interest or behavior, allowing personalized experiences, and in situation context, which could be a personal assistant, etc. Context is crucial for the effectiveness of AI systems and their responses to complex inquiries.

- Inference Mechanism (heuristic), which monitors program execution by utilizing the knowledge-base to modify Context in all three areas, generating a workspace for the problem established by the Inference Mechanism using the user-provided information and the knowledge-base or from the ML algorithm.

- User Interface;

- Explanation Facility;

- Knowledge-Acquisition Module, as schematically shown in Figure 1.

3. Results

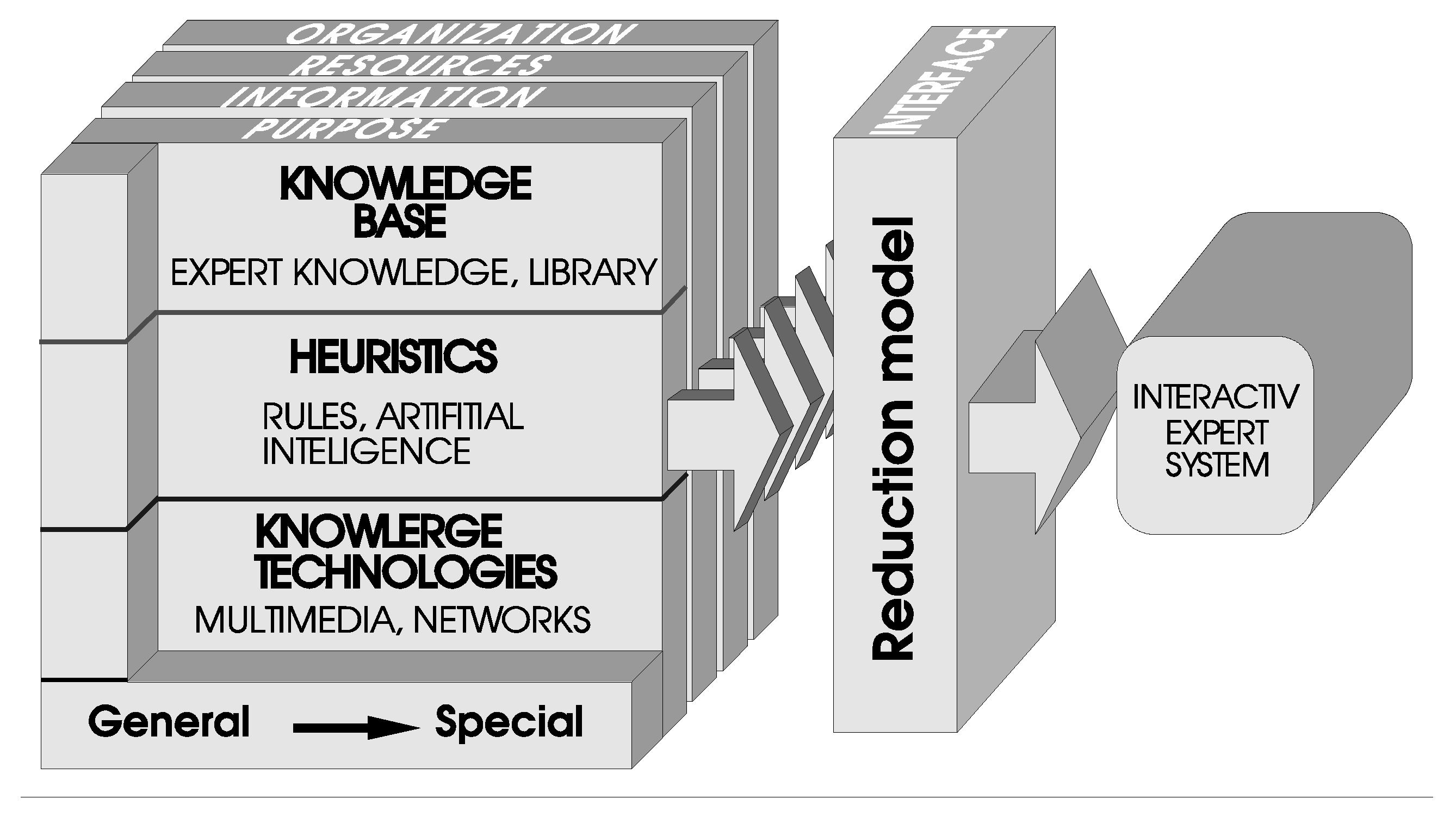

- differentiating between dependent and independent parameters,

- gearing model construction,

- an iterative process to determine the optimal design, with successive model analysis.

- A small, random initial population is chosen.

- Using genetic operators and taking into account the selected local criteria, the convergence of the population is affected.

- The new population is determined by integrating the most successful members of the old population, while the remaining members are randomly selected.

- If the global convergence criterion is fulfilled, the process is terminated, or

- We go back to point 2.

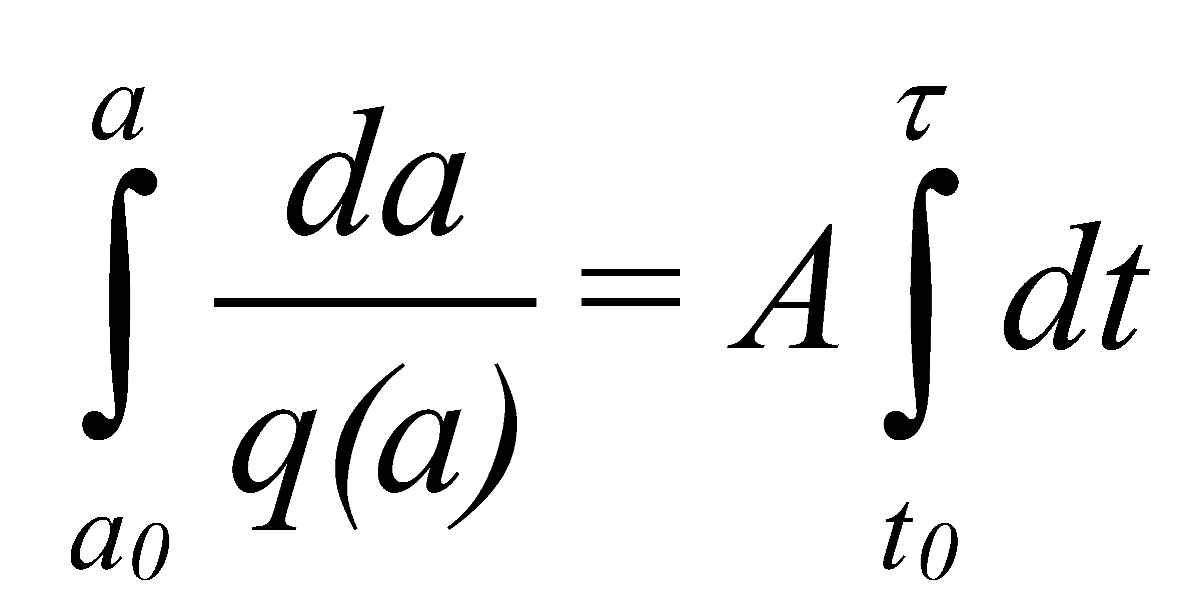

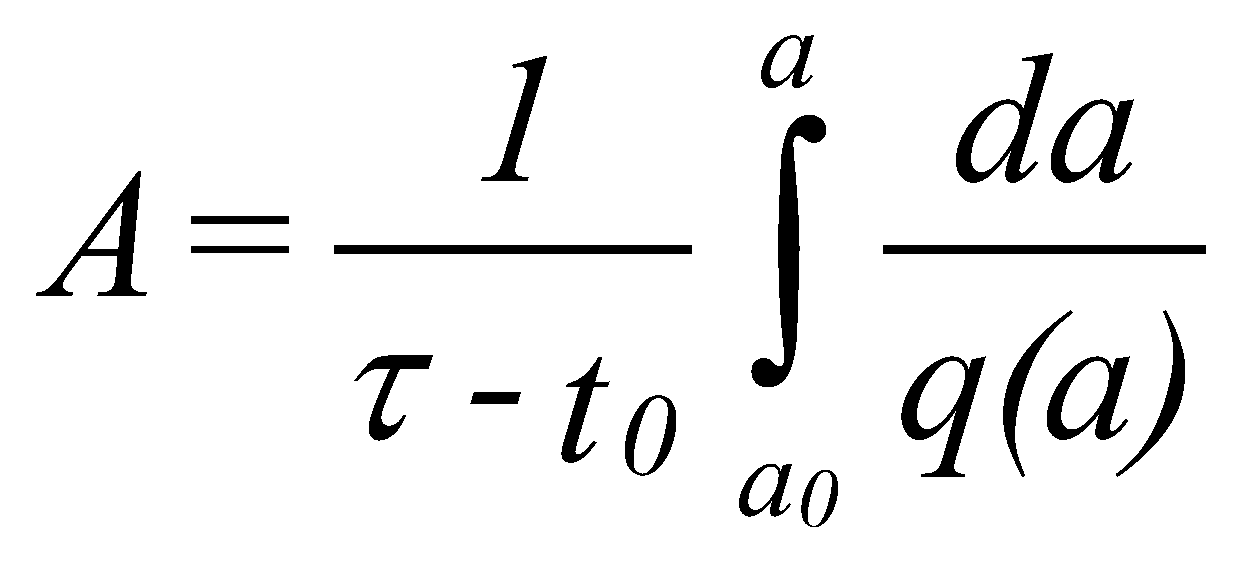

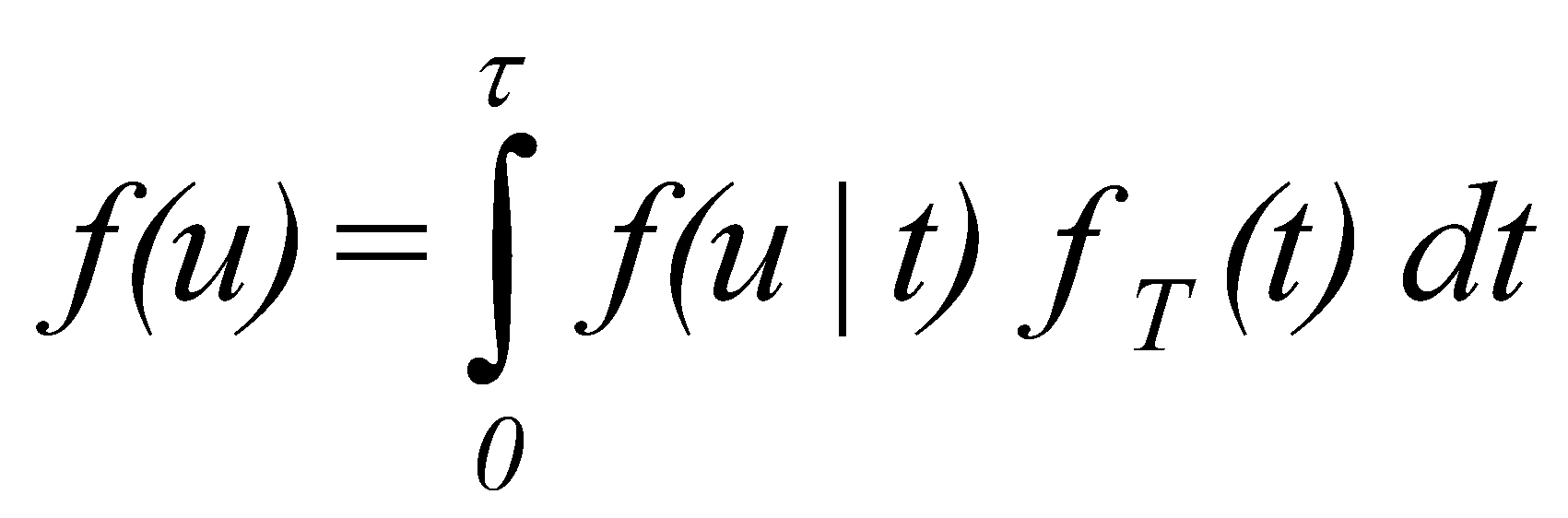

3.1. Calculating Service Life

3.1.1. Crack Without a Crack – Crack Incubation

3.1.2 Potential Crack Nucleation Sites

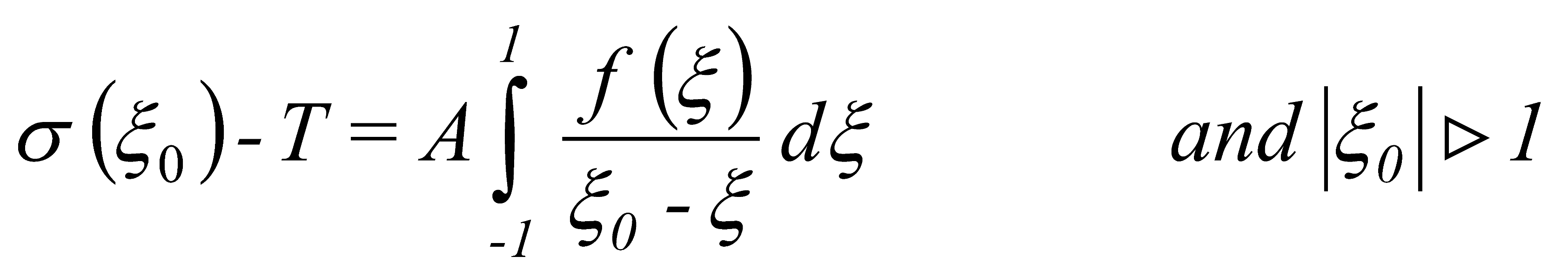

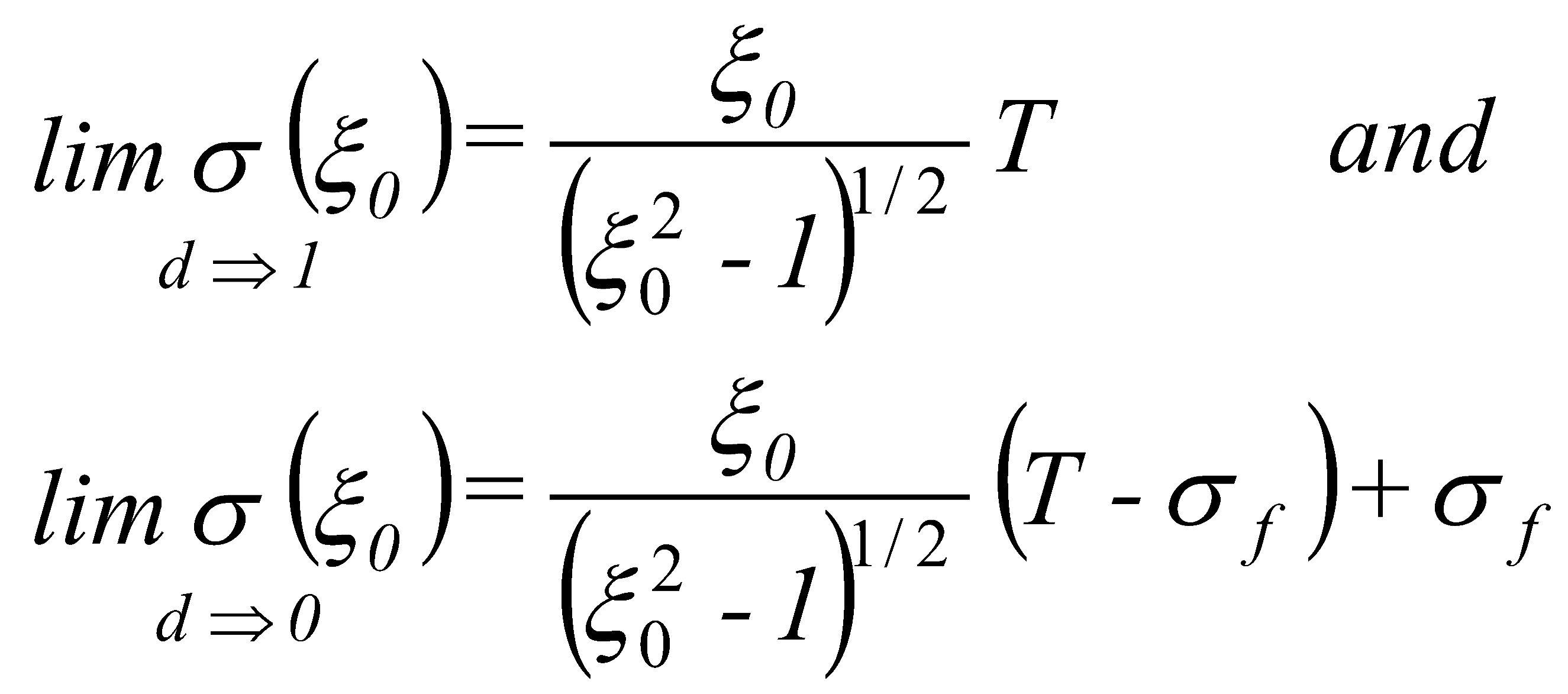

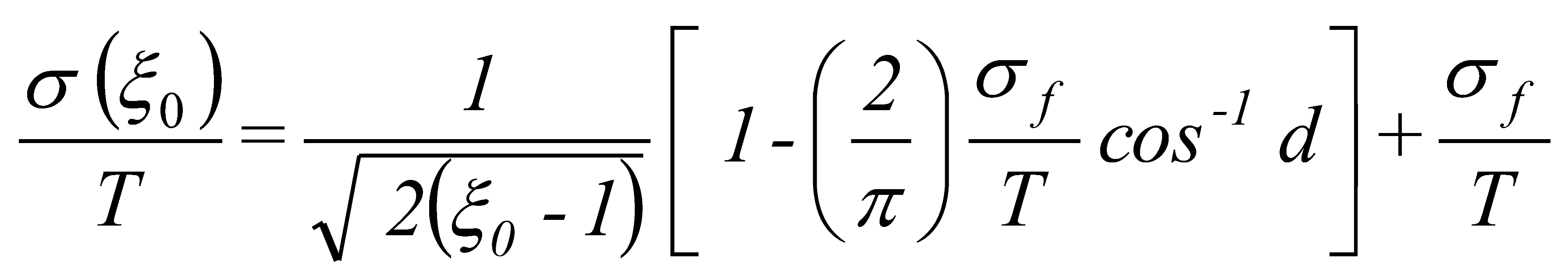

3.2. Model of Crack Initiation

(20)

(20) (21)

(21) (22)

(22) (23)

(23) (24)

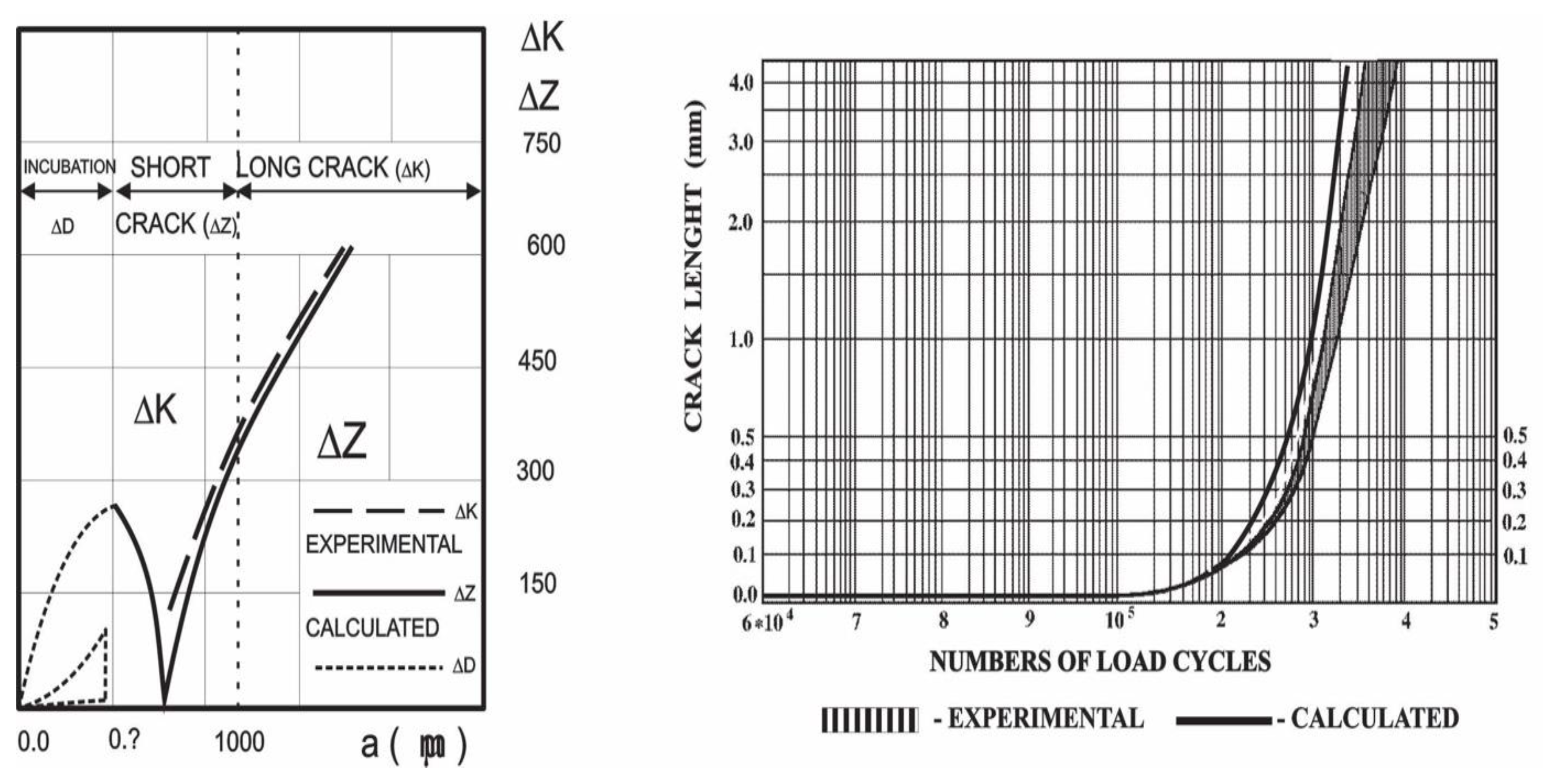

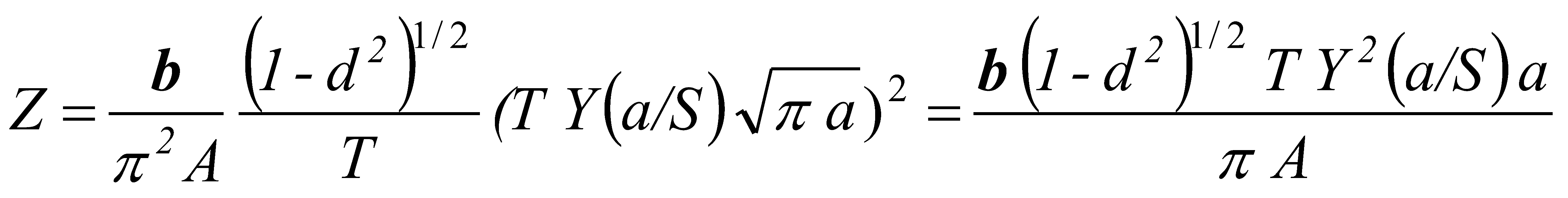

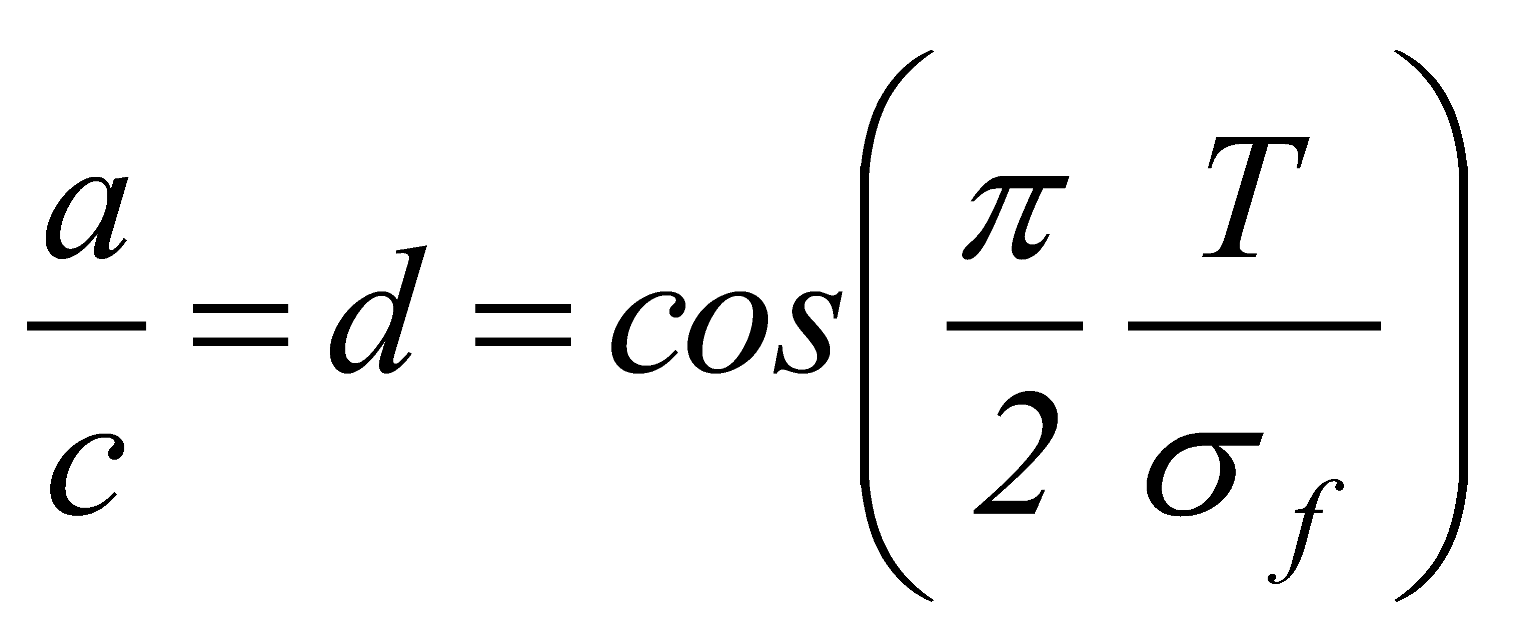

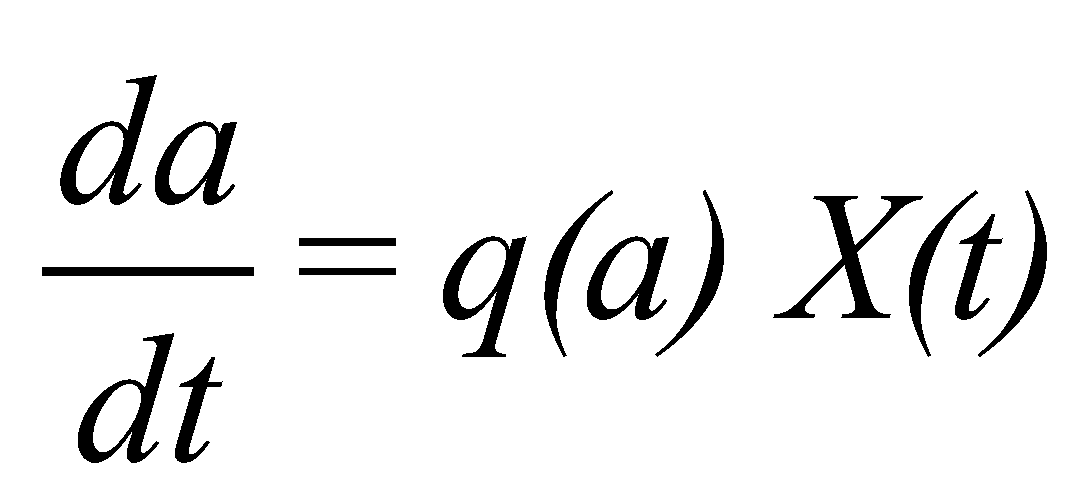

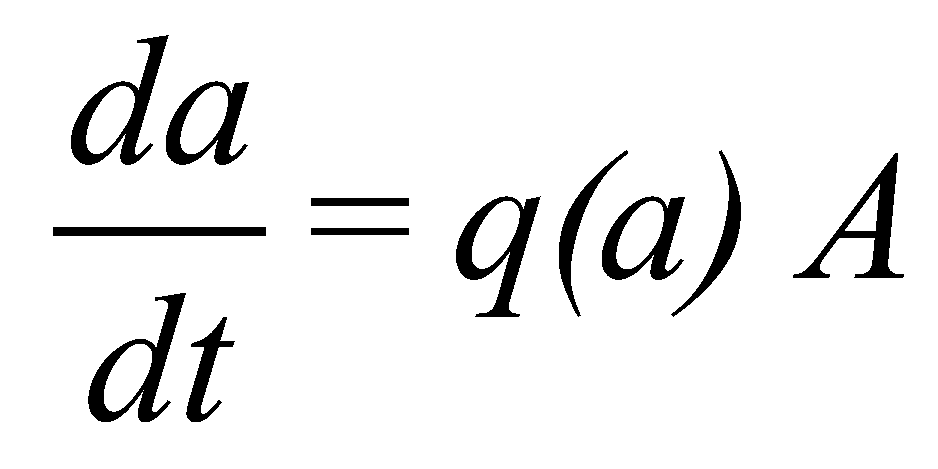

(24)3.3. Model of Crack Propagation

(26)

(26) (27)

(27) (28)

(28) (29)

(29) (30)

(30) (31)

(31) (32)

(32)3.4. Experimental Verification of Incubation/Initiation Period

3.4.1. Crack Incubation and Initiation

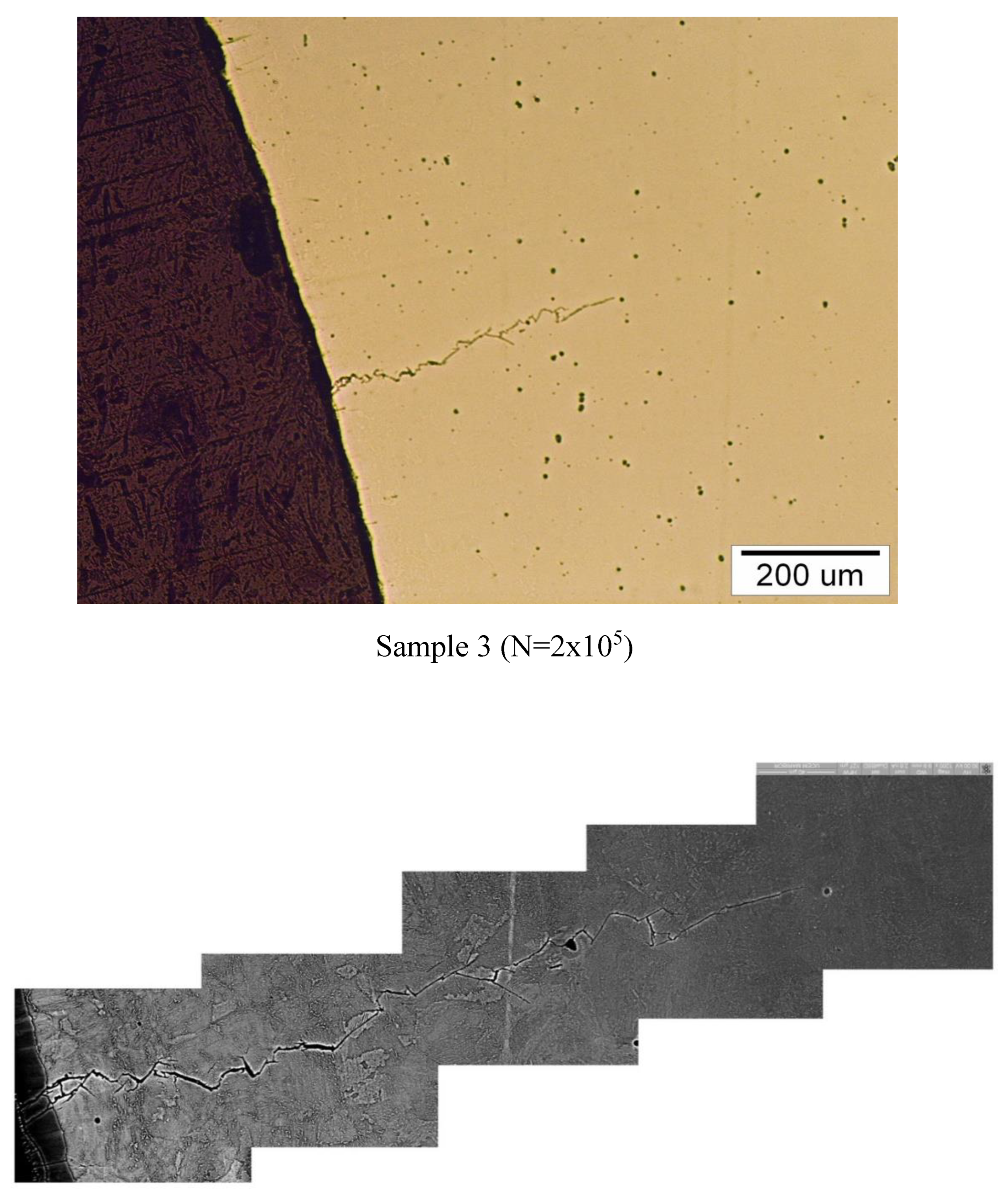

- 5 x 104

- 105 and

- 2x105 cycles

3.4.2. Fractography

4.1. Indirect Confirmation for Initiation and Incubation of Cracks

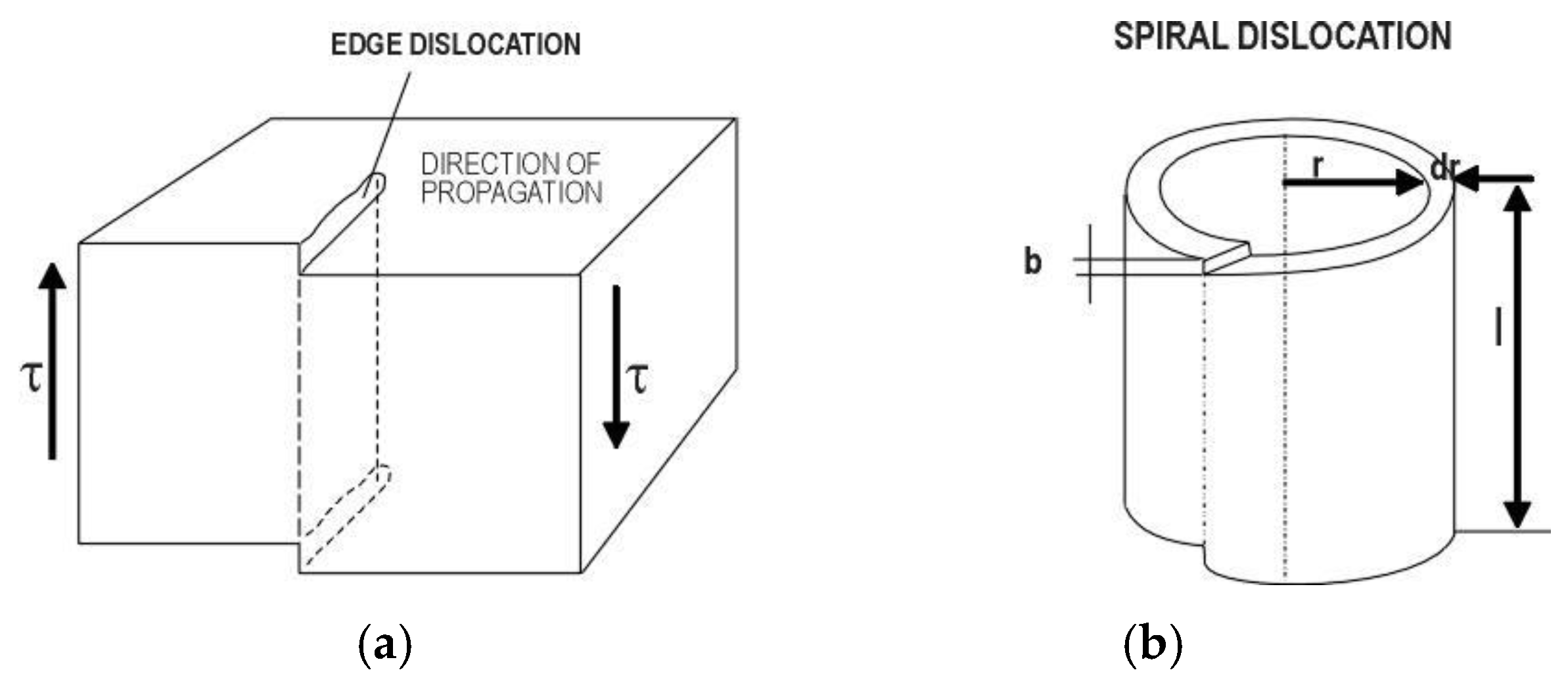

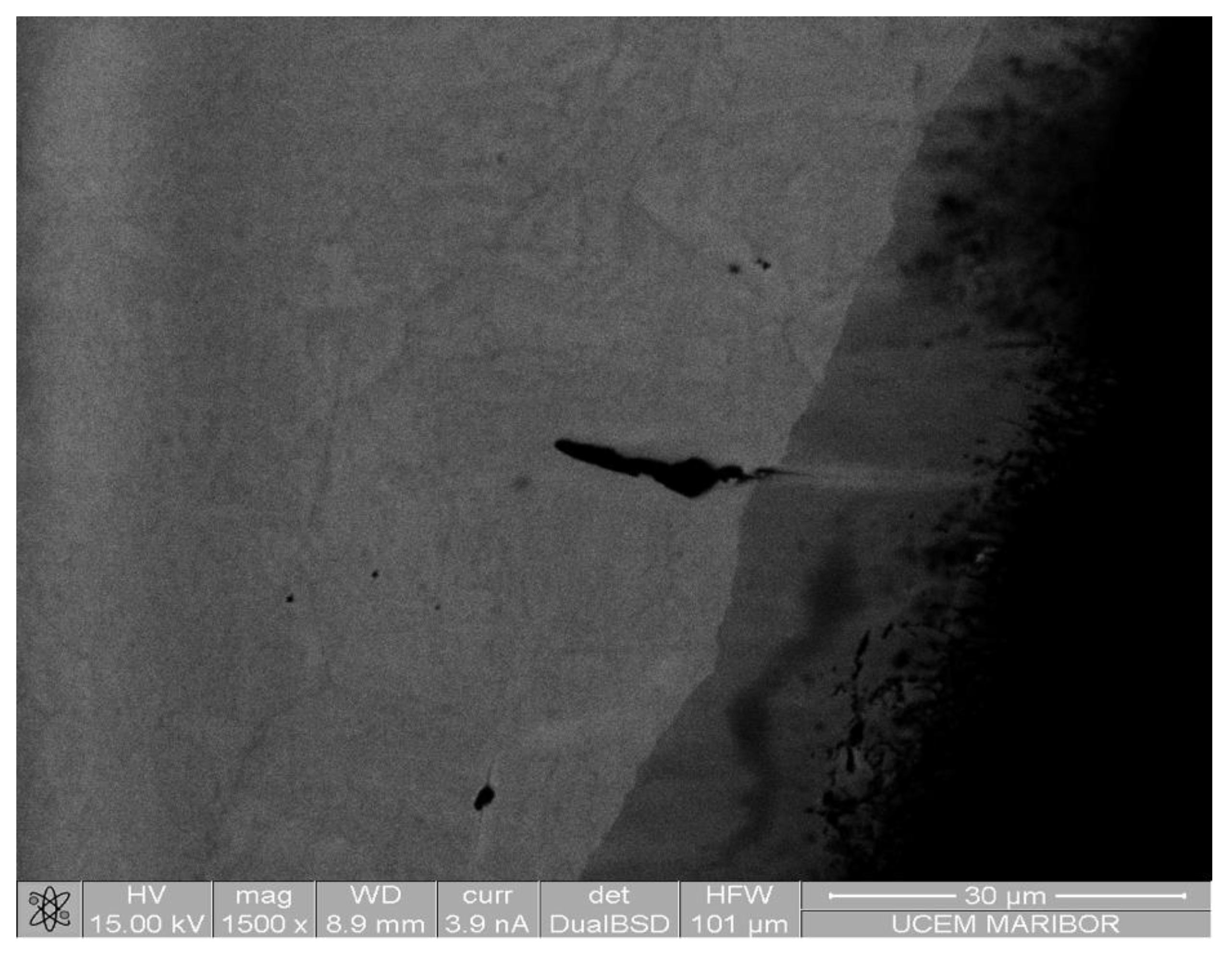

- The results of the first fractographic examination of 5 x 104 cycles are shown in Figure 5, where the formation of the initial and the grouping of defects around the initials and dislocations, probably in the form of micro lunkers or similar defects, can be observed.

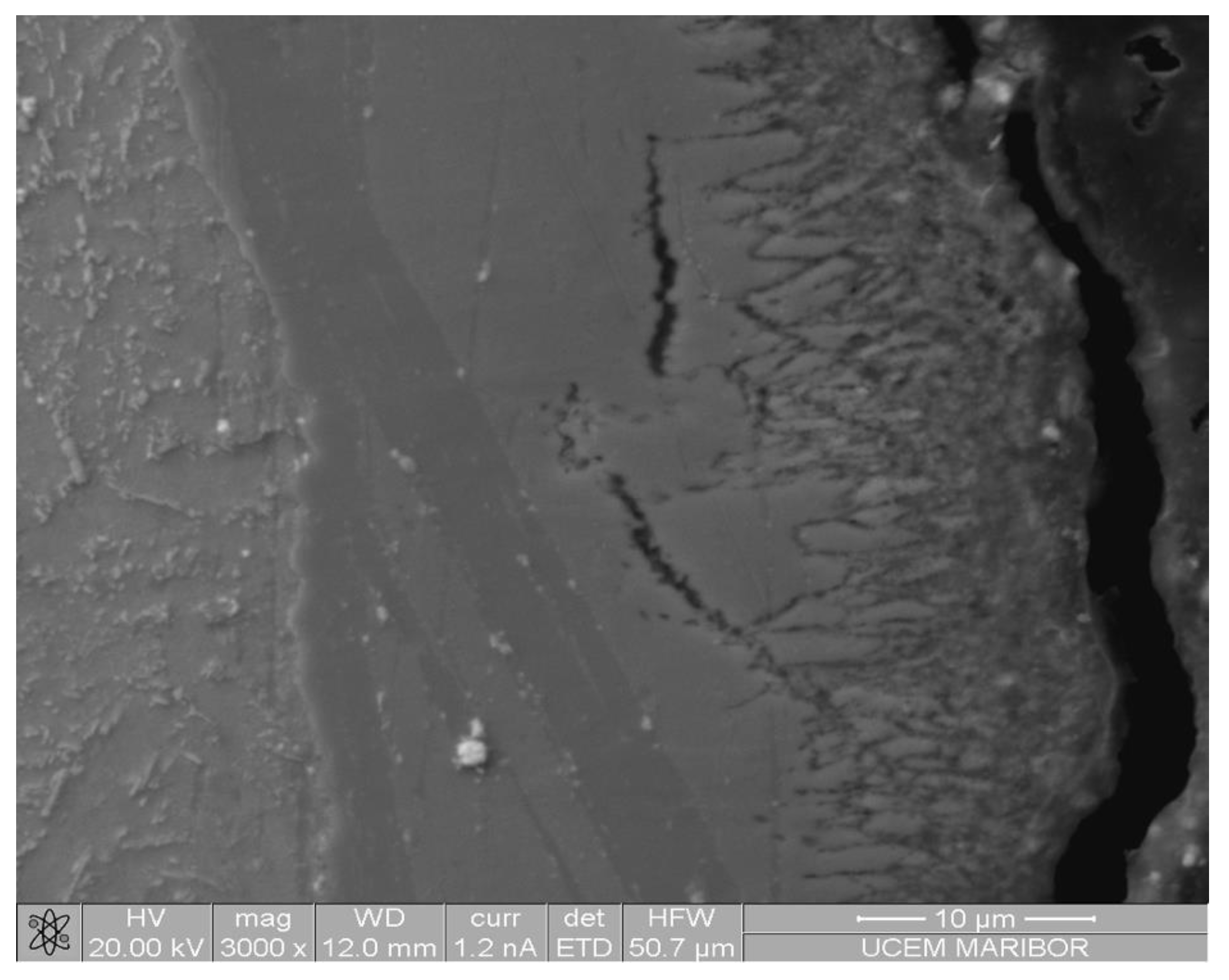

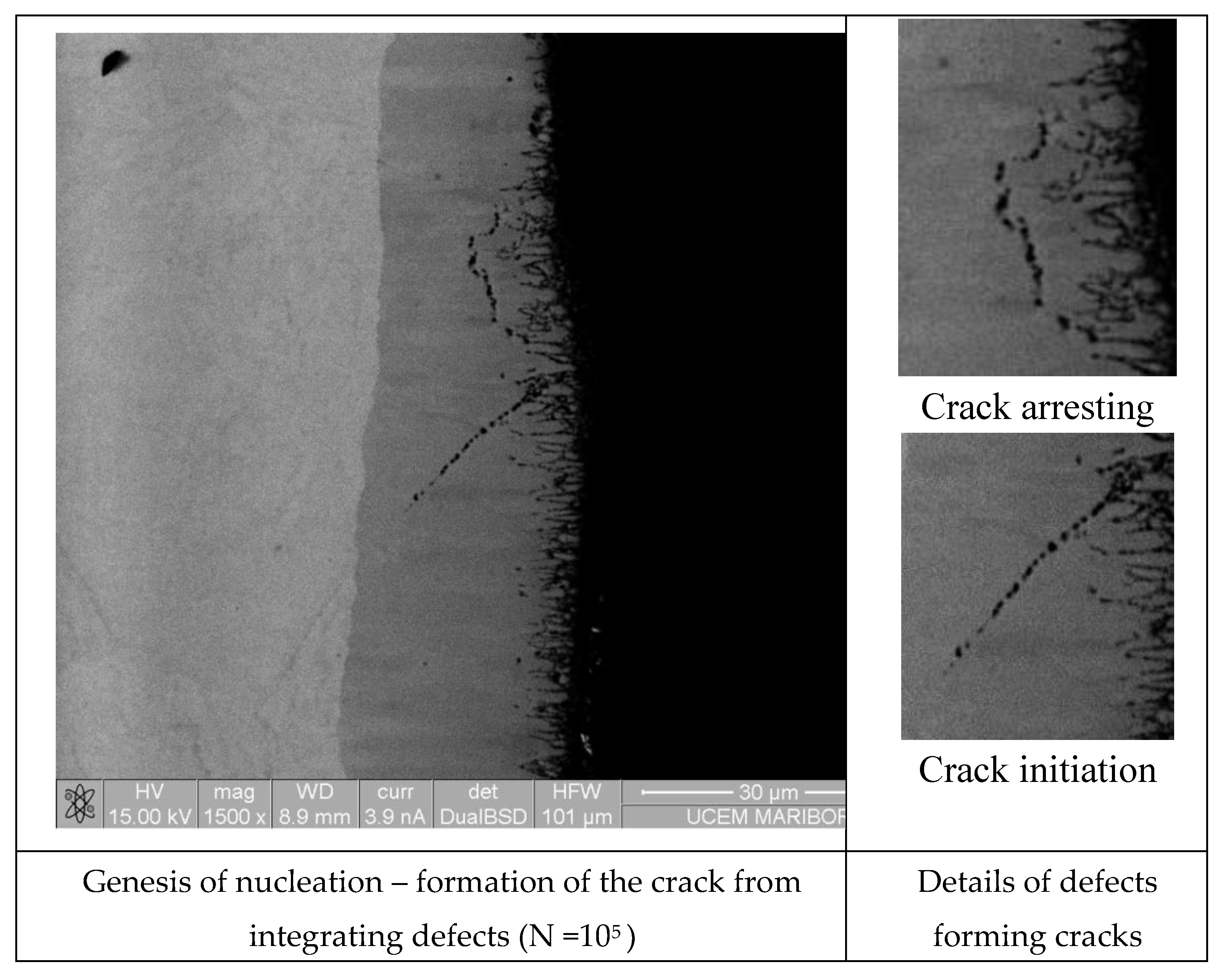

- Figure 6 and Figure 7 present the results of the second fractographic study after 105 load cycles, and indicate the grouping of different defects, especially in the form of dislocations, and the potential formation of initials for the formation of cracks. Figure 7 thus shows two principles of creating potential cracks: initials that do not expand (crack arrest) and can lead to pitting on the gears, and initials that can lead to the initiation of potential cracks.

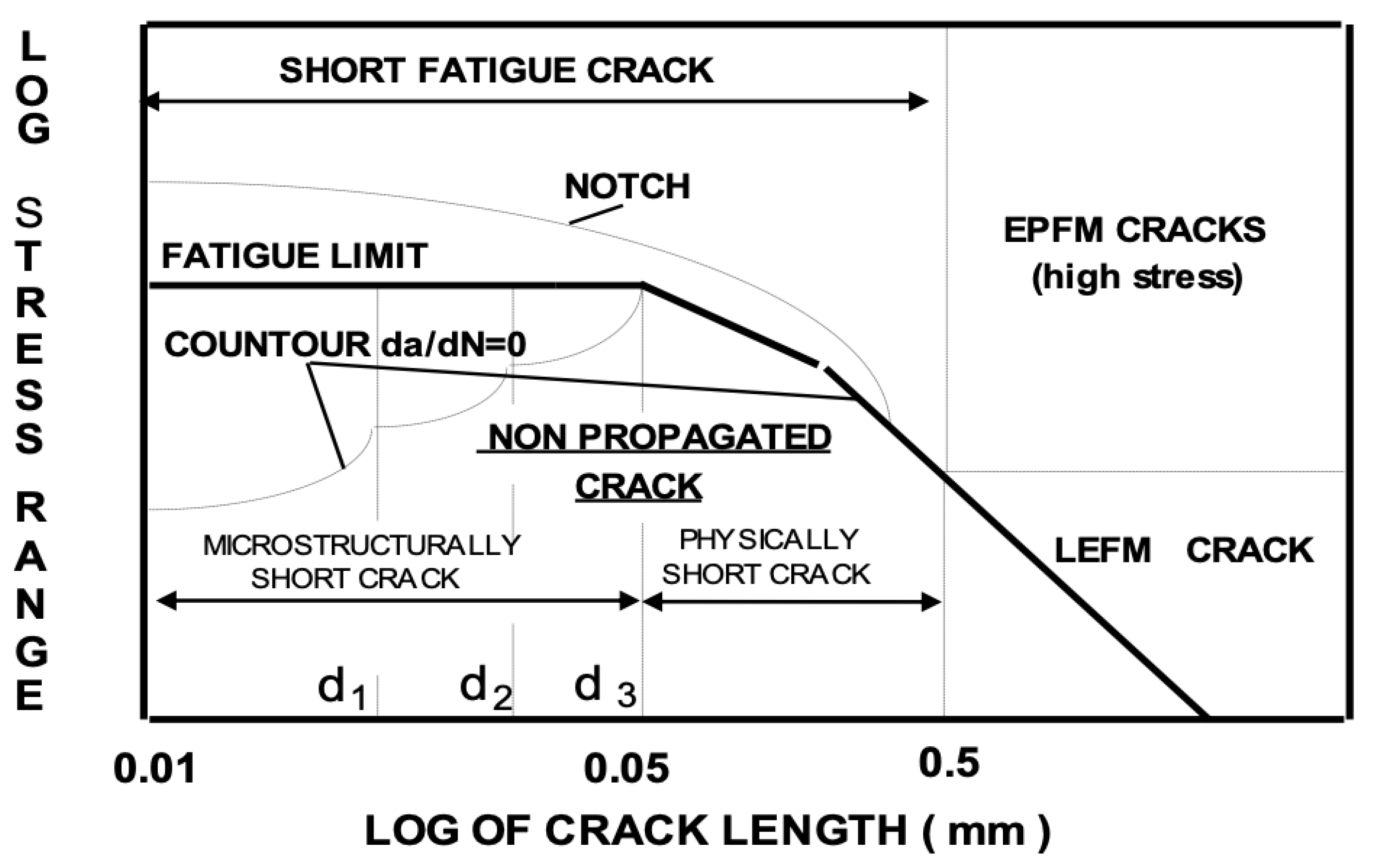

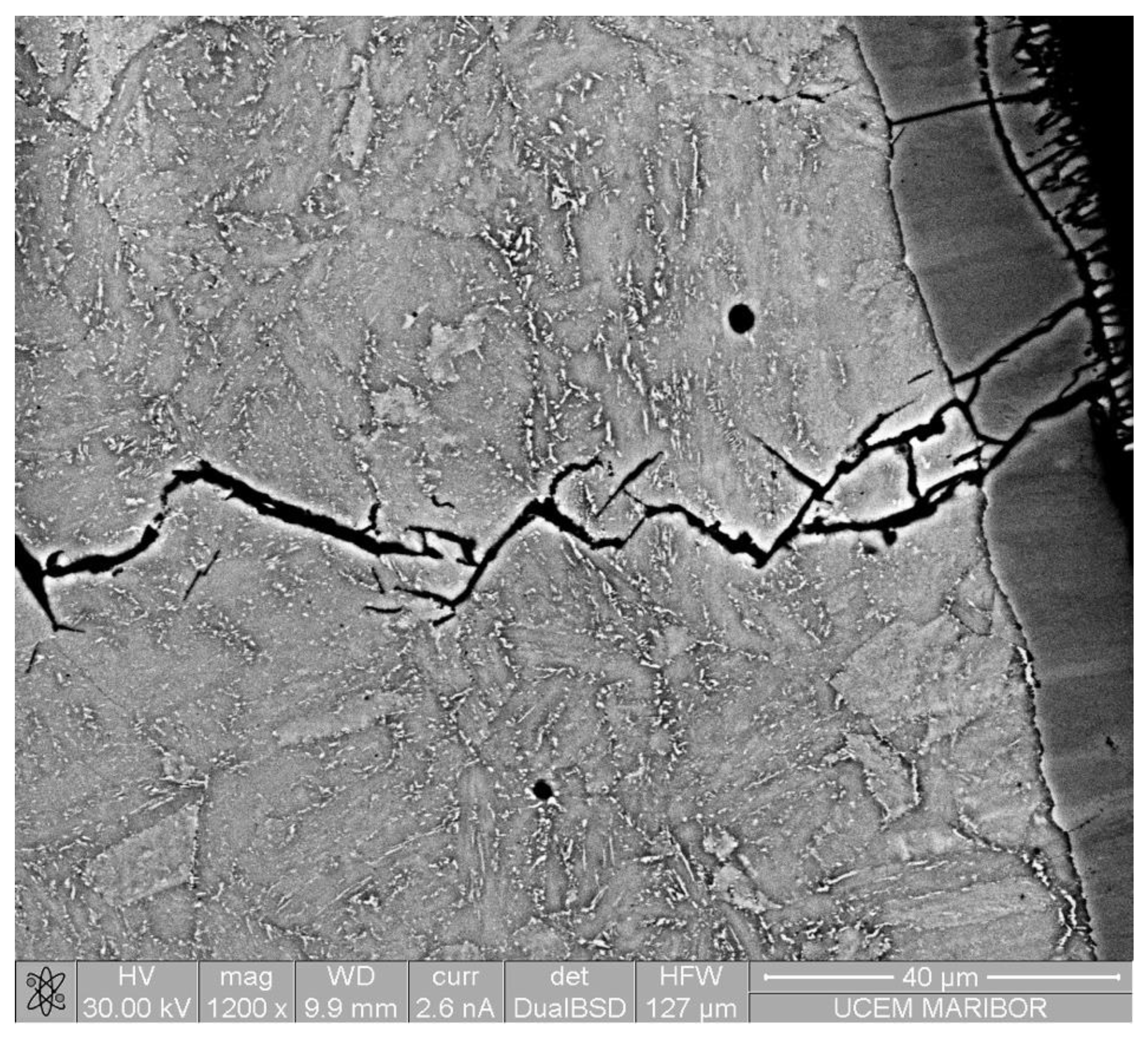

- The results of the third fractographic study after 2x105 load cycles are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. Thus, Figure 8 shows the start of the spread of microstructural short cracks, from which it can be observed that the main model of crack propagation is along the boundaries of crystals. Figure 9 shows the entire course of the spread of microstructural and physical short cracks (see Kitagawa-Takahashi diagram - Figure 3), where the crack length is at the limit of detection, and when cracks can be detected by various non-destructive detection methods that have been used in previous studies.

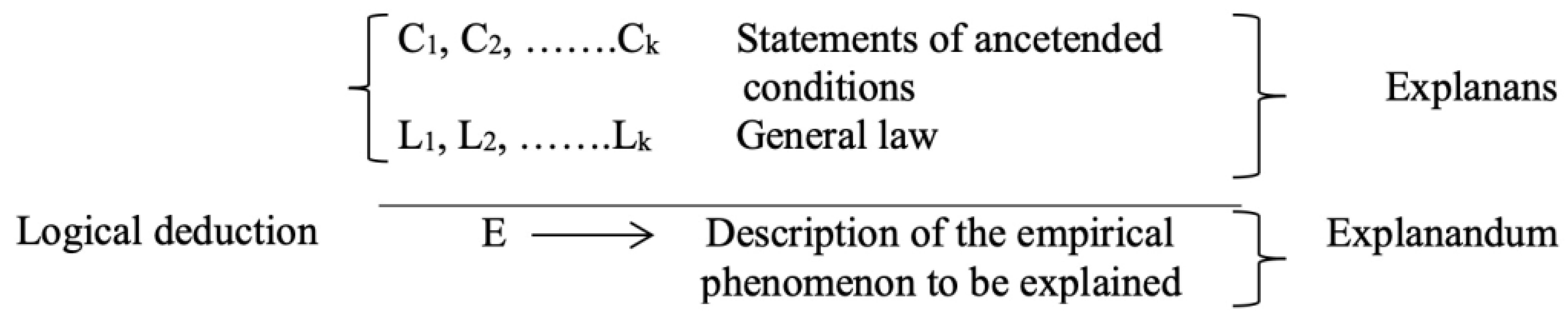

4. Discussion

- the explanandum must logically follow from the explanans;

- the explanans must refer to general laws, and these must be genuinely necessary for deriving the explanandum, and

- explanans must be supported by empirical content;

4.2. Crack Propagation

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aberšek, B.; Flašker, J. How gears break, WIT Press: UK, 2004.

- Aberšek, B.; Flašker, J. Numerical methods for evaluation of service life of gear, International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering,1995; Vol. 38, 2531-2545.

- B. Aberšek, J. Flašker, J.; Glodež, S. Review of mathematical and experimental models for determination of service life of gears. Eng. fract. mech. 2004, vol. 71, iss. 4/6, 439-453.

- Buehler, M.J. , et al., The Computational materials Design Facility (CMDF): A powerful framework for multiparadigm multi-scale simulations. Mat. Res. Soc. Proceedings, 2006. 894: p. LL3.

- Flogie, A.; Aberšek, B. Artificial intelligence in education. IN: LUTSENKO, Olena (ur.). Active learning - theory and practice. London: IntechOpen, 2022, 97-117. [CrossRef]

- Aberšek, B.; Flašker, J. Experimental Analysis of Propagation of Fatigue Crack on Gears, Experimental Mechanics, 1998, Vol. 38, No. 3, 226-230.

- J. W. Provan, W. Probabilistic Fracture Mechanics and Reliability, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Dordrecht, Boston, Lancaster, 1987.

- Spergel, D.N. , Turok, N.G., Textures and cosmic structure, Sci. Am., 1996. 266: p 52-59.

- Zurek, W.H. Cosmological experiments in condensed matter. Phys. Rep., 1984. 276 : p 177-221.

- Bradač, Z. , Kralj, S., Žumer, S., Early stage domain coarsening of the isotropic-nematic phase transition, J.Chem.Phys., 2011. 135 : p 024506-024516.

- Imry, Y.; Ma, S. , Random-Field Instability of the Ordered State of Continuous Symmetry, Phys. Rev. Lett., 1975. 35 : p 1399-1402.

- Aharony, A.; Pytte, E. , Infinite Susceptibility Phase in Random Uniaxial Anisotropy Magnets, Phys. Rev. Lett., 1980. 45: 1583-1587.

- Bellini, T.; et al. Nematics with quenched disorder: What is left when long range is disrupted? Phys. Rev. Lett., 2000. 31: 1008-1011.

- Mermin, N.D. , The topological theory of defects in ordered media, Rev. Mod. Phys., 1976. 51: 591-648.

- Lubensky, T.C.; Renn, S.R. , Twist-grain-boundary phases near the nematic–smectic-A–smectic-C point in liquid crystals, Phys. Rev.. A, 1990. 41. p: 4392–4401.

- Abrikosov, A.A. On the Magnetic Properties of Superconductors of the Second Group, Soviet Physics JETP, 1957. 5: 1174-1182.

- De Gennes, P.G. , Prost, The Physics of Liquid Crystals (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1993.

- Taylor, D. ; J. F. Knott, J.F. Fatigue crack propagation behaviour of short crack; the effect of microstructure, Fatigue Engn. Mater. Struct., 1981 4, 147 - 155.

- Hempel, C.G. Aspects of Scientific Explanation and Other Essays in the Philosophy of Science. New York: The Free Press, 1965.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).