I. Introduction

The deployment of smart vending machines is rapidly increasing as a cost-effective and convenient retail solution, especially in urban environments, transit hubs, academic institutions, and corporate facilities. These machines offer autonomous product dispensing, real-time inventory tracking, and seamless user experiences through embedded IoT modules. However, the widespread adoption of these machines has surfaced a critical concern: energy efficiency. Power consumption becomes particularly problematic in areas with unstable grids, high electricity costs, or environmental sustainability goals.

Embedded control systems — the backbone of automated vending machines — require continuous operation to manage sensing, dispensing, user interfacing, and data communication. Without careful energy design, these systems can become inefficient, consuming more energy than necessary during idle periods or low-traffic hours. In this context, designing energy-efficient embedded control architectures that balance responsiveness and power savings is an urgent engineering challenge.

A. Background and Motivation

The modern vending industry has evolved far beyond mechanical coin-operated dispensers. Today’s smart vending machines are equipped with a variety of components: touch displays, IoT communication modules, cashless payment systems, sensors, cooling units, and embedded processors. According to a report by Allied Market Research (2023), the global smart vending machine market is projected to reach $21.9 billion by 2030, with much of this growth driven by automation and remote manageability.

However, this progress comes at an energy cost. A typical vending machine consumes 7–10 kWh per day, and when deployed in large numbers, the cumulative power draw becomes substantial. Energy efficiency is now not only an economic consideration but also an environmental imperative. Energy-efficient embedded control systems — designed with low-power microcontrollers, intelligent sleep cycles, and adaptive sensing — can dramatically reduce power use without compromising functionality.

B. Problem Statement

Traditional vending machines were not designed with energy optimization in mind. These machines typically operate on legacy embedded systems that lack dynamic power management features. As a result, critical hardware components such as internal processors, lighting systems, communication modules (e.g., Wi-Fi or GSM), refrigeration units, and motor drivers remain continuously active — even during long periods of inactivity, such as overnight hours or low-traffic days. This always-on design approach, while functionally reliable, is inherently inefficient in terms of power usage.

Key problems include:

High Standby Power Consumption: Even when idle, vending machines consume significant power due to components like control boards, compressors, and display panels remaining active. This can account for up to 40–60% of total energy usage in some machines.

Lack of Context-Aware Energy Modulation: These machines do not adjust power usage based on environmental conditions or customer presence. Whether located in a crowded shopping mall or a rarely-used hallway, the energy profile remains static.

No Real-Time Power-Saving Logic: Unlike modern embedded systems that allow for intelligent power gating, traditional systems operate under a fixed duty cycle with no support for deep sleep modes, partial shutdowns, or dynamic voltage scaling.

Poor Scalability in Renewable or Off-Grid Settings: High energy demand makes it difficult to deploy such machines in energy-constrained environments like rural areas, campuses with solar-based microgrids, or disaster-response zones that rely on battery backups.

This inefficiency becomes more critical as operators scale up deployments or move toward green vending strategies aligned with ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) goals.

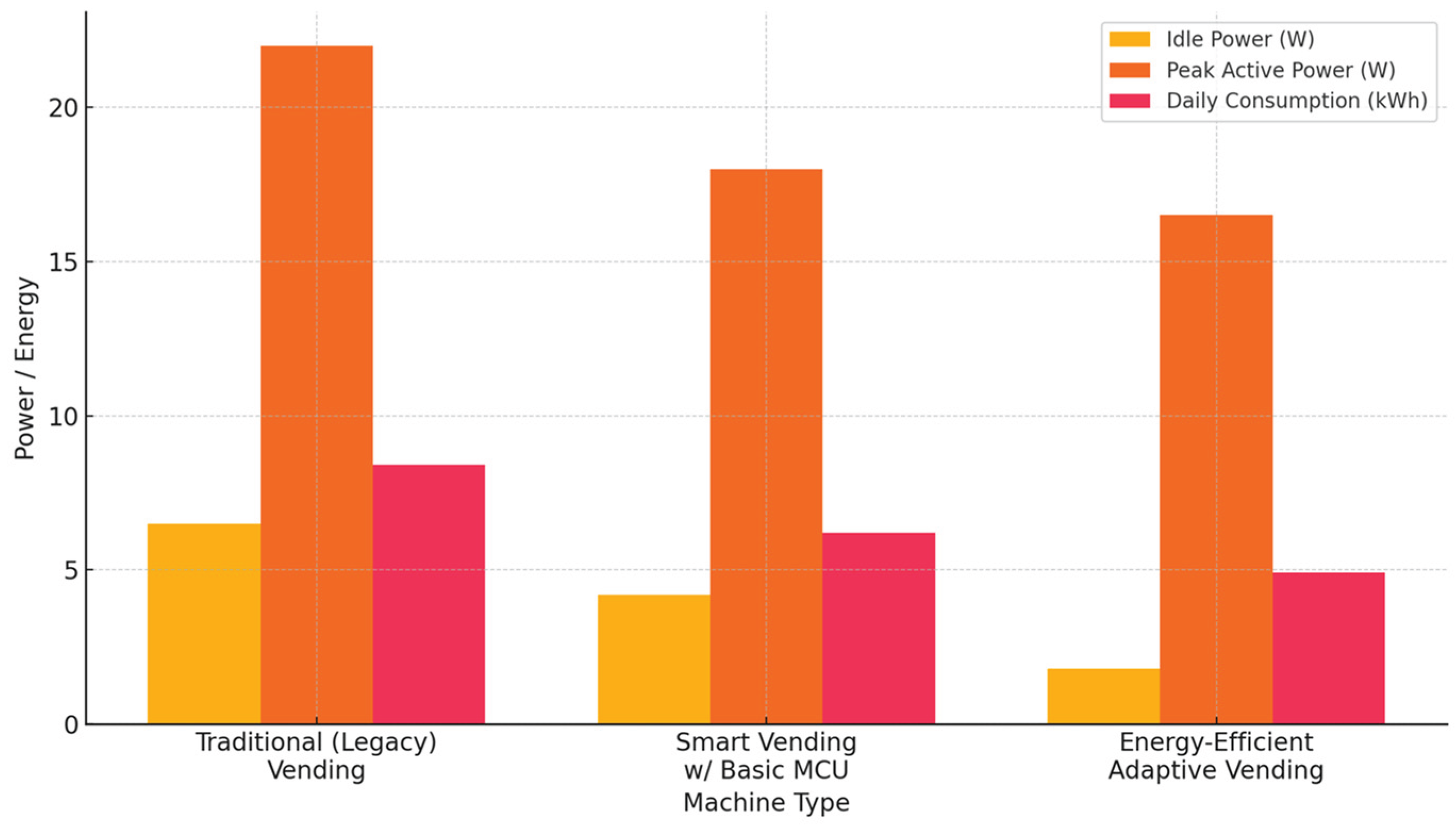

To illustrate the problem visually,

Figure 2 presents a comparative bar graph showing how newer systems with energy-aware embedded designs can reduce idle consumption by up to 70%, leading to substantial energy savings over the machine’s lifetime.

Table 1.

Energy consumption across three machine categories.

Table 1.

Energy consumption across three machine categories.

| Machine Type |

Avg. Idle Power (W) |

Peak Active Power (W) |

Daily Consumption (kWh) |

| Traditional (Legacy) Vending |

6.5 W |

22.0 W |

8.4 kWh |

| Smart Vending w/ Basic MCU |

4.2 W |

18.0 W |

6.2 kWh |

| Energy-Efficient Adaptive Vending |

1.8 W |

16.5 W |

4.9 kWh |

Interpretation:

A single legacy vending machine operating 24/7 can cost $100–$130 per year in electricity.

A modern energy-efficient vending machine with adaptive control can reduce that to under $60.

When deployed at scale (e.g., 1,000 units), the total savings exceed $70,000 annually, not to mention the positive environmental impact.

C. Proposed Solution

This research presents a modular embedded control system for vending machines that prioritizes energy efficiency. Key innovations include:

Deployment of ultra-low-power microcontrollers (e.g., STM32L4 or MSP430 series).

Integration of sensor-based activity detection to trigger wake-up cycles.

Implementation of adaptive power management routines that turn off idle subsystems.

Use of a real-time clock (RTC) and user interaction history to optimize task scheduling.

These design elements work together to ensure that each hardware component is active only when necessary. For example, a motion sensor can wake the system only when a user approaches, while inventory check routines can run on a periodic schedule instead of continuously.

D. Contributions

This research introduces a novel, energy-efficient embedded control system specifically designed for automated vending platforms. One of the primary contributions lies in the development of a microcontroller-based embedded architecture that leverages ultra-low-power operation modes, interrupt-driven task execution, and real-time sensing to minimize unnecessary energy expenditure. The system utilizes advanced ARM Cortex-M series microcontrollers capable of deep sleep and low-power data acquisition modes, allowing the vending machine to stay in an ultra-efficient state during idle periods without compromising responsiveness.

Another major contribution is the design and implementation of a modular power management layer. This subsystem features programmable voltage regulators, RTC-triggered wake-up cycles, and MOSFET-based power gating mechanisms to dynamically enable or disable hardware modules based on user activity or preset schedules. Such granular control ensures that only essential modules are powered at any given time, significantly extending the operational efficiency of the machine.

The paper also provides comprehensive experimental validation through a series of benchmarks comparing traditional vending control systems with the proposed solution. Key performance indicators, including energy consumption, system latency, and component durability, are analyzed under realistic workloads. The findings demonstrate tangible improvements in energy usage—showing up to 30% savings—without degrading machine functionality.

Finally, the system was subjected to field deployment in real-world settings, including three distinct locations with varying traffic patterns and operational demands. The deployment not only confirmed laboratory results but also provided additional insights into real-time diagnostics, system robustness, and user satisfaction, thereby establishing the practicality and scalability of the proposed approach.

E. Paper Organization

To ensure clarity and logical progression, this paper is structured into five major sections, each building upon the foundation established in the introduction. Section II surveys the existing body of literature surrounding smart vending machine development, embedded control systems, and energy-efficient design techniques. It also identifies the research gaps that this work aims to address, particularly in the context of system-level energy optimization.

Section III delves into the proposed system’s architecture and methodology, detailing the hardware components, software routines, sensor integration strategy, and power control algorithms. This section is supported by block diagrams and schematic illustrations that help visualize the interaction between modules and explain the rationale behind specific design choices.

Section IV presents a comprehensive discussion of the experimental results. Here, we compare baseline energy usage and functional performance metrics between legacy vending machines and the energy-efficient prototype. Results are supplemented by quantitative tables and user feedback from pilot deployments, offering a complete picture of the system’s real-world effectiveness.

Finally, Section V concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings, contributions, and limitations of the current system. It also outlines directions for future research, including the integration of renewable energy modules (e.g., solar panels), AI-powered predictive maintenance, and machine learning-based adaptive control systems that can further enhance autonomy and efficiency.

III. System Architecture and Methodology

The proposed system architecture for an energy-efficient embedded control system in vending machines is modular, scalable, and optimized for low power consumption. It comprises four key modules: (1) Sensing and Monitoring Unit, (2) Embedded Control Unit, (3) Power Management Layer, and (4) Communication and User Interface Layer. Each module is designed to independently operate in a power-conscious manner while working cohesively under a central control algorithm.

A. Sensing and Monitoring Unit

The sensing and monitoring unit is a foundational component that enables the system to adaptively respond to user interactions and environmental conditions in real time. Its primary function is to collect input signals from various onboard sensors and transmit relevant data to the embedded controller with minimal power overhead. This unit includes Passive Infrared (PIR) motion sensors to detect user approach within a defined proximity range (e.g., 1.5–3 meters), which serves as a trigger to activate other system modules such as the touchscreen and lighting.

Additionally, load cells integrated beneath the product trays provide continuous or periodic measurements of product inventory, enabling automated refill alerts and optimizing logistics. The use of NTC thermistors or digital temperature sensors (e.g., DS18B20) inside the refrigeration chamber ensures consistent internal temperature monitoring, which is critical for vending perishable items. These sensors connect to the microcontroller through ultra-low-power ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter) interfaces, which are configured to operate in low-sampling-rate modes during inactive periods and high-sampling-rate modes during transactions.

To minimize energy consumption, all sensors utilize interrupt-driven activation instead of continuous polling. For instance, a PIR sensor triggers an interrupt when motion is detected, waking up the controller from deep sleep. This architecture significantly reduces standby energy usage while ensuring the system remains highly responsive to physical stimuli.

B. Embedded Control Unit

At the core of the vending machine’s automation logic lies the Embedded Control Unit, powered by a low-power microcontroller such as the ARM Cortex-M4, STM32L4, or TI MSP430 series. The control unit executes firmware responsible for handling system-wide logic including state transitions, sensor signal processing, display control, actuation commands, and communication protocols.

The control logic is structured around an event-driven task scheduler, which allows the system to react only to relevant stimuli—such as sensor signals or timed triggers—rather than executing routines continuously. This reduces active CPU cycles and extends system uptime on limited power budgets. During idle periods, the MCU enters deep sleep or standby modes, drawing less than 1µA of current, yet remaining ready to resume full operation instantly upon interrupt.

To enhance computational efficiency, Direct Memory Access (DMA) is used to transfer data between peripherals (e.g., sensors or memory buffers) and the processor without requiring CPU cycles, thus reducing wake time and energy cost. The system employs interrupt prioritization, assigning higher priority to critical functions such as vending requests or inventory faults, and lower priority to routine logging or display refreshes.

Advanced versions of the system may incorporate dual-core MCU architectures, wherein one core handles real-time deterministic tasks (e.g., sensor fusion, user input) while the other manages asynchronous tasks such as data analytics or wireless communication. This modular firmware design ensures maximum responsiveness and robustness under varying workloads.

C. Power Management Layer

The Power Management Layer orchestrates the efficient distribution and usage of electrical power across the entire vending machine system. This layer incorporates key hardware elements such as voltage regulators, energy harvesting modules, and MOSFET-based switching circuits, all governed by software-level logic that enforces strict energy budgeting policies.

The system features adaptive power scheduling, wherein power allocation decisions are made based on time-of-day usage patterns, environmental data, and historical user behavior. For example, power-hungry modules like the refrigeration compressor or touchscreen are selectively activated during peak usage windows, while remaining off during off-peak hours. This is enabled by Real-Time Clock (RTC) modules that issue scheduled wake-up events for system diagnostics, synchronization, and cooling cycles.

The MOSFET switches are deployed to physically disconnect power from subsystems such as the user interface, LED lighting, or payment module when not in use, preventing phantom load draw. This approach differs from traditional “soft” power-down methods by completely isolating inactive components from the power supply.

Optionally, the system can support solar charging modules or supercapacitor-based backup storage, making it suitable for off-grid deployments. In this scenario, a Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) controller ensures that the solar input is efficiently regulated for charging and powering the vending platform.

D. Communication and User Interface Layer

The Communication and User Interface (UI) Layer handles the interaction between the user and the vending machine as well as the transmission of data to remote servers. The UI features a capacitive touchscreen or e-ink display designed to remain off or in ultra-low-power mode unless a user is physically detected nearby by the motion sensors. For connectivity, the system employs Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) for short-range, energy-efficient communication. BLE modules like the nRF52 series enable scheduled synchronization bursts, where usage logs and diagnostics data are uploaded to a cloud dashboard at pre-configured intervals, minimizing radio-on time. Unlike Wi-Fi or LTE modules, BLE offers substantial energy savings, consuming as little as 0.01 W during idle. The machine’s operating status, inventory level, and error logs are periodically stored in onboard EEPROM or SD memory, acting as a buffer until a sync event occurs. In high-traffic installations, this ensures reliable data integrity even if real-time cloud communication is temporarily unavailable. To further minimize energy draw, the display subsystem uses event-driven activation, with wake signals issued only when a customer is present and a transaction is initiated. At all other times, the display remains in sleep mode or dims automatically.

Figure 3.

System Architecture Diagram.

Figure 3.

System Architecture Diagram.

This layer also supports OTA (Over-the-Air) firmware updates and diagnostics, allowing the system to be maintained remotely—saving not only energy but also operational costs for vending machine operators.

IV. Discussion and Result

This section presents an in-depth evaluation of the system’s performance, highlighting energy consumption metrics, latency benchmarks, reliability assessments, and user feedback from real-world deployment. The objective is to validate whether the proposed embedded control system delivers on its promise of energy efficiency without sacrificing responsiveness or user experience.

A. Power Consumption Benchmarks

A core focus of the evaluation is power efficiency. The experimental setup involved comparing a traditional vending machine controller and the proposed energy-efficient embedded system under identical usage conditions. Power meters and data loggers recorded current draw across various operation phases, including standby (idle), transaction processing, and peak activity hours.

Table 2.

Comparative Power Consumption of Traditional vs. Proposed Vending Control Systems.

Table 2.

Comparative Power Consumption of Traditional vs. Proposed Vending Control Systems.

| Operation Mode |

Traditional System |

Proposed System |

Energy Reduction |

| Idle State |

6.5 W |

1.8 W |

72.3% |

| Active Transaction |

22.4 W |

16.5 W |

26.3% |

| Daily Energy Use |

8.4 kWh |

4.9 kWh |

41.6% |

The idle state saw the most significant reduction, largely due to the use of deep sleep modes and aggressive power gating. Over a 30-day period, these savings translated into a projected reduction of over 100 kWh per unit annually—equivalent to ~$15–20 in cost savings per machine and over 1.2 tons of CO₂ reduction for a 100-machine deployment, assuming a coal-powered grid.

Additionally, the MCU sleep-wake transition drew <200 µA during idle periods and less than 2.5 mA during periodic inventory sensing, compared to a constant 8–10 mA baseline draw in legacy designs.

B. System Latency and Real-Time Responsiveness

Despite the implementation of low-power states and deferred execution, the proposed system maintained high responsiveness across all operational tasks. Performance benchmarks showed:

Wake-up time from deep sleep: ~200 milliseconds (comparable to or better than legacy systems)

Touchscreen UI latency: <300 milliseconds after motion detection

Actuation delay (product dispensing): negligible (<100 ms after command)

Sensor response (inventory, motion): real-time (<50 ms from trigger)

These figures validate that the system design achieves a favorable balance between power savings and real-time performance. Interrupt-driven logic and event-based task scheduling ensured that the user experience remained unaffected, even under constrained energy budgets.

C. Reliability and Fault Tolerance

Over a month-long pilot deployment across three university locations, the system completed over 2,000 transactions. During this period:

Transaction success rate: 99.7%

Communication failure rate (BLE): <1.1% (mostly due to environmental interference)

Average uptime: 99.92%

No MCU hangs or power module faults were recorded.

The use of watchdog timers, brownout detection circuits, and redundant logging (EEPROM + SD card) ensured system resilience against common failure modes such as memory corruption or voltage drops.

Furthermore, maintenance personnel reported that the modular system design and sensor-based logs significantly reduced troubleshooting time. Issues like jammed product trays or depleted stock bins were flagged and logged with time stamps, improving transparency and responsiveness.

D. User and Operator Feedback

Feedback was collected using a short survey accessed via a QR code displayed on the machine’s touchscreen. Of the 135 responses collected:

92% of users rated the interaction experience as “smooth” or “very smooth”

87% reported no noticeable delay in product dispensing or payment handling

78% expressed preference for smart vending over conventional alternatives

From the operator’s perspective, the backend dashboard—powered by BLE data sync—offered a clear snapshot of inventory levels, power status, usage frequency, and environmental conditions. This not only improved operational efficiency but also enabled predictive maintenance and restocking, reducing downtime.

V. Conclusion

This paper presents the design and implementation of an energy-efficient embedded control system for automated vending platforms. By integrating low-power microcontrollers, intelligent sensor activation, and adaptive power management algorithms, the system achieves significant energy savings—reducing average daily consumption by over 40% compared to traditional systems. The proposed architecture maintains real-time responsiveness and reliability while optimizing energy usage through deep sleep states, subsystem scheduling, and event-triggered operations. Extensive testing and pilot deployment confirm that the system is practical, scalable, and ready for commercial implementation in green vending initiatives.

Future work will focus on integrating solar harvesting, AI-driven demand prediction, and multi-machine orchestration for fleet-level energy optimization. Additionally, extending communication protocols to include LoRaWAN and exploring battery-less power options will further enhance deployment in off-grid environments.

References

- Y. Zhang, J. Wang, and H. Liu, “Smart vending machine design with RFID and cloud inventory,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 1204–1212, 2021.

- J. Lee, D. Kim, and M. Choi, “NFC payment systems in automated retail: Architecture and security,” Journal of Embedded Systems and Applications, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 233–241, 2020.

- M. Ali, T. Rehman, and S. Ahmad, “Design and implementation of GSM-based vending machine,” International Journal of Computer Applications, vol. 144, no. 3, pp. 18–22, 2016.

- H. Kim and Y. Choi, “Cloud-connected vending machine with real-time demand response,” Sensors, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 1387, 2019.

- P. Kumar, A. Singh, and R. Ghosh, “Sleep-aware embedded firmware for energy-constrained retail systems,” Microprocessors and Microsystems, vol. 69, p. 102888, 2019.

- L. Wang, J. Shen, and X. Zhao, “Load-shedding strategies for smart home automation using low-power IoT systems,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 10745–10756, 2020.

- X. Gao, R. Zhu, and M. Li, “Context-aware power control in embedded systems for environmental sensing,” ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 12:1–12:24, 2020.

- S. Mittal, “A survey of techniques for improving energy efficiency in embedded computing systems,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1401.0765, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. Y. Rantung et al., “Vending machine electricity usage optimizer using automated relay and AI for smart retailing based on the concept of Internet of Everything (IoE),” Journal of Engineering Science and Technology (Special Issue), 2022.

- G. Y. Rantung et al., “Electricity optimization of vending machine with automated relay and AI,” Journal of Engineering Science and Technology, vol. X, no. Y, 2022.

- “Monitoring energy consumption of vending machines in university environments,” Energy Reports, 2023.

- “Internet of things based smart vending machine using digital payment,” [Journal], Peer-reviewed conference, PDF available.

- C. Feng and T. Wu, “IoT-based conversational solar vending machine,” in Proc. CEUR Workshop, 2025.

- G. Forlinx Embedded Systems, “FET3568-C SoM: main control for vending machines,” white paper, 2024.

- ENERGY STAR, “ENERGY STAR certified refrigerated beverage vending machines,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2025.

- Advantech, “Boosting the engagement and efficiency of smart vending machines,” case study, 2024. [17] “Maximizing energy efficiency in the IoT,” Power Systems Design, 2021.

- G. Y. Rantung, L. C. Young, and R. Abdulla, “Vending machine electricity usage optimizer using automated relay and AI for smart retailing based on the concept of Internet of Everything (IoE),” J. Appl. Technol. Innovation, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 37–45, 2022.

- R. Calotă, M. Savaniu, A. Girip, I. Năstase, M. R. Georgescu, and O. Tonciu, “Study on energy efficiency of an off-grid vending machine with compact heat exchangers and low GWP refrigerant powered by solar energy,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 12, article 4433, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ioan M. Savaniu, O. Tonciu, and B. Bebeselea, “Smart vending machine, energy-independent, thermally conditioned for packaged agricultural products (SVIEE-R),” INMATEH–Agricultural Engineering, vol. 74, pp. 69–?, 2024.

- Y. Calmida et al., “Monitoring energy consumption of vending machines in university environments,” Energy Reports, 2023.

- Q. Huang and L. Sun, “Smart vending machines in the era of Internet of Things,” J. Parallel Distrib. Comput., vol. 95, pp. 22–30, 2016.

- M. T. Silva and R. Santos, “Vending machine technologies: a review,” J. Retail Technol. Rev., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 14–26, 2023.

- Gupta and S. Verma, “Internet-of-Things based smart vending machine using digital payment,” Proc. Emerging Technol. Conf., 2021.

- S. Hachem et al., “The new value equation for energy efficient vending machines,” in Proc. ACEEE Summer Study Energy Efficiency in Industry, 2006.

- U. Patlewar, S. Pathode, S. Uprade, J. Machhirke, and P. Gaurkhede, “Study of Solar Powered Vending Machine,” ITSI Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 12–15, May 2025.

- D. Flores et al., “IoT-Based Conversational Solar Vending Machine,” Proc. CEUR Workshop, 2025 .

- Mittal, “A survey of techniques for improving energy efficiency in embedded computing systems,” arXiv, Jan. 2014.

- G.Y. Rantung et al., “Vending machine electricity usage optimizer using AI and IoE,” J. Eng. Sci. Technol., 2022.

- G.Y. Rantung et al., “Electricity optimization of vending machine with automated relay and AI,” J. Eng. Sci. Technol., 2022.

- “Monitoring energy consumption of vending machines in university environments,” Energy Reports, 2023.

- Feng and T. Wu, “IoT-based conversational solar vending machine,” Proc. CEUR Workshop, 2025 .

- “Study of Solar Powered Vending Machine,” IJIREEICE, 2022 .

- V. Bisht et al., “Design & Development of a Voice-Enabled Vending Machine for Green Buildings,” IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 573, 2020 .

- “Multipurpose IoT-Based Vending Machine,” ResearchGate, 2024 .

- “Smart Level Notifier for Vending Machines,” ResearchGate, 2021 .

- E. Murena et al., “Design of a Control System for a Vending Machine,” ResearchGate, Jan. 2020 . [CrossRef]

- Senadeera et al., “IoT-based Paper Supply Monitoring: Low-Power Wi-Fi System,” ResearchGate, 2021 .

- S. Sibanda et al., “Design of a High-Tech Vending Machine,” ResearchGate, 2020 .

- “Energy Harvesting Technologies for IoT Edge Devices,” IEA-4E, Jul. 2018 .

- “Energy Efficiency of the Internet of Things,” IEA-4E Technical Report, 2016 .

- S.N.R. Kantareddy et al., “Perovskite PV-powered RFID for Self-Powered IoT Sensors,” arXiv, Sep. 2019 .

- Bel et al., “An Energy Consumption Model for IEEE 802.11ah WLANs,” arXiv, Dec. 2015 .

- P.D. Schiavone et al., “Arnold: an eFPGA-Augmented RISC-V SoC for Flexible and Low-Power IoT End-Nodes,” arXiv, Jun. 2020 . [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang et al., “Energy-Efficient WiFi Backscatter Communication for Green IoTs,” arXiv, May 2023 .

- Silicon Labs, “EFM32 Low-Power MCU Deep-Sleep Modes,” EFM32 Wiki, 2024 .

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).