1. Introduction

Sorghum (

Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) is one of the primary cereal crops grown worldwide, renowned for its resistance to water stress, high productivity, and low production costs, making it a vital source of food and animal feed, particularly in regions of Latin America, Africa, and Asia [

1,

2]. Furthermore, sorghum is recognized for its nutritional composition, which is comparable to other cereals like corn, rice, and wheat. However, sorghum stands out due to its high concentration of phenolic compounds, such as tannins, anthocyanins, and flavanones, as well as vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and other bioactive compounds. These properties contribute to its health benefits, including anticancer, antidiabetic, anti-aging, and anti-inflammatory effects [

3,

4,

5].

However, sorghum contains high levels of tannins, which reduce the digestibility of proteins and the bioavailability of amino acids [

6]. As a result, techniques aimed at improving the nutritional quality of sorghum grains have been widely explored, with germination, fermentation, and enzymatic hydrolysis being some of the most promising biotechnological tools [

7]. Seed germination is a simple and cost-effective approach to modifying the physicochemical, biochemical, and sensory characteristics of grains. It enhances the bioavailability of bioactive compounds and promotes the synthesis of substances with high biological activity [

4,

8,

9]. This process involves the activation of the seed’s endogenous enzymatic system, facilitating the bioconversion of primary macronutrients such as starch, proteins, and lipids, while also contributing to the reduction of antinutritional factors (such as phytic acid and trypsin inhibitors), resulting in superior nutritional quality compared to ungerminated seeds [

10,

11].

Several studies have demonstrated the effects of germination on sorghum. For example, Singh et al. [

2] observed that germination time and temperature directly influence the nutritional and technological properties of sorghum, reducing crude protein, fat, insoluble dietary fiber, and ash content, while improving the technological characteristics of starch. Other studies, such as Abdelbost et al. [

10], indicate that germination enhances the digestibility of proteins like kafirin, the main storage protein in sorghum. D’Almeida et al. [

12] reported that germination modifies the relationship between free and bound phenolic compounds, facilitating the decomplexation of phenolic compounds within the cell matrix. This process leads to enhanced phenolic bioaccessibility and significantly improves the nutritional and bioactive properties of the grains. Additionally, Kayisoglu et al. [

13] assert that germination can reduce or eliminate antinutritional factors such as tannins, phytates, and protease inhibitors, making germinated sorghum significantly healthier compared to ungerminated sorghum.

The production of alcoholic beverages from cereals, such as beer, is a widely practiced method globally, with beer being one of the most consumed alcoholic beverages. Traditionally, beer is produced using malted barley, hops, and water, with the addition of yeast. However, the use of alternative cereals, particularly among craft breweries, has gained attention. The use of both malted and unmalted cereals not only enhances the flavor and sensory characteristics of beer but also contributes to the increase of bioactive compounds in the beerage, making it healthier. Moreover, it supports the agroindustry, family farming, food sovereignty, and sustainability [

14,

15].

Based on the above, the present study aimed to evaluate the impact of the binomial time/temperature on the germination process of sorghum grains and its implications for the physicochemical characteristics of these grains. Subsequently, the application of germinated sorghum as a raw material for gluten-free lager beer was investigated, with a focus on improving the nutritional and physicochemical quality of the beverage.

2. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

The sorghum (BRS 330) was obtained from a local farmer in the municipality of Sengés (24° 06′ 46″ S, 49° 27′ 50″ W), Paraná, Brazil. The seeds, in healthy condition, were manually selected and subsequently stored in polyethylene terephthalate packaging at room temperature (20°C), in a light-free environment, until the analyses were initiated.

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Raw Material

The sorghum seed batch was sampled by quartering, and the samples were evaluated for the following parameters: moisture (method 44-15.02), lipids (method 30-25.01), ashes (method 08-01.01), proteins (method 46-11.02, with N = 6.25 factor), and starch (method 76-11.01), according to the procedures established by the AACCI [

16].

3.3. Experimental Design

The optimal conditions for the germination process were determined using the Response Surface Methodology, applying a Central Composite Rotational Design (CCRD) with two independent variables: X1 – germination time and X2 – germination temperature, as illustrated in

Table 1. The mathematical model for the experimental design is represented in Equation 1, as proposed by Rodrigues and Iemma [

17].

where

Y is the value of the dependent variable;

b0,

bi,

bii, and

bij are the regression coefficients of constant, linear, quadratic, and interaction, respectively;

xi and

xj are the encoded values for the independent variables; and

ε is the experimental error.

3.4. Germination Process

The germination of sorghum seeds was conducted following the protocol described by Andressa et al. [

18]. In brief, 120 g of sorghum seeds were sanitized using a sodium hypochlorite solution at 200 ppm for 30 minutes, followed by washing with distilled water until complete removal of residual chlorine. The seeds were then macerated in distilled water (1:5) for 8 hours at room temperature (20°C). Next, the grains were placed in polyethylene trays (0.045 m

2), ensuring no overlap, with the top and bottom layers covered with cotton (approximately 20 g) and separated by a paper towel layer (0.044 g/m

2). Each cotton layer was moistened with 100 mL of distilled water. The trays were incubated in a BOD germination chamber (BOD TF-33A, Telga, Belo Horizonte, Brazil). To maintain the necessary humidity, a polyethylene tray (0.042 m

2) was placed with 3 L of distilled water at the bottom of the chamber, and the samples were sprayed with distilled water every 12 hours. Germination occurred in the dark, with light exposure only when the BOD chamber was opened to spray distilled water. The relative humidity was maintained between 75-80%, monitored by a psychrometric chart, considering both dry and wet bulb temperatures. After the time and temperature parameters for germination were defined according to the experimental design, the radicle length of ten random seeds was measured using a professional optical caliper (150 mm, Western, Suzhou, China). The samples were then placed in perforated trays (0.14 m

2) and dehydrated in a TE-394/1 drying oven (Tecnal, Piracicaba, Brazil) with forced air circulation (1 m/s) at 45 °C for 12 hours. After drying, the seeds were cooled to room temperature, and the radicles were manually removed. Subsequently, the sorghum was ground using a Multi Grains disc mill (Malta, Caxias do Sul, Brazil) until the particle size was less than 250 µm. The germinated sorghum flours were quantified for moisture (method 44-15.02) before being stored in biaxially oriented polypropylene packaging under refrigeration (4 °C), in the absence of light.

3.5. Sorghum Wort Preparation

The sorghum flours were subjected to mashing in a SL-150 water bath (Solab, Piracicaba, Brazil) in a 1:5 dry basis ratio (20 g of sorghum flour to 100 g of potable water). During the mashing process, the times and temperatures for each ramp were monitored as described by Nascimento et al. [

19]: 35 °C for 20 minutes, 45 °C for 10 minutes, 52 °C for 10 minutes, 62 °C for 20 minutes, 72 °C for 20 minutes, and 75 °C for 5 minutes. After mashing, the samples were filtered using a 0.88 mm mesh. The final volume was measured in a 250 mL volumetric flask with potable water. The samples were stored in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, frozen in a DFN41 freezer (Electrolux, Curitiba, Brazil) at -18 °C, in the absence of light, until analysis.

3.5.1. Analysis of Germinated Sorghum Wort

The sorghum wort was characterized for the following parameters: total reducing sugars (method 80-68.01), total solids (method 44-20.01), and soluble proteins (method 46-11.05, with N = 6.25), according to the AACCI [

16]. The analyses were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed in ºBrix for soluble solids, g of glucose per 100 mL of wort, and as percentages (w/v) for total solids and proteins. In addition, the instrumental color was determined using a CM-5 Konica colorimeter (Minolta, Chiyoda, Japan), in the

L*,

a*,

b* color space, with D65 illuminant and a 10° observer angle, as described by Nascimento et al. [

13]. Readings were made directly on 60 mm diameter Petri dishes containing 20 g of sample.

The total soluble phenolic compound content was determined by transferring 100 μL of each diluted extract to test tubes, to which 250 μL of 0.2 N Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent, 3 mL of distilled water, and 1 mL of 15% (m/v) sodium carbonate solution were added, as described by Cáceres et al. [

20]. The tubes were manually shaken and incubated in the absence of light at room temperature for 30 minutes. Absorbance was measured using a UV-M5 1 spectrophotometer (BelPhotonics, Monza, Italy) at a wavelength of 750 nm, using a standard gallic acid curve (7 points: 0 to 150 mg/L; y = 0.0037x + 0.011; r

2 = 0.9969). Readings were made in quadruplicate for the aqueous extracts of the worts and expressed in mg of gallic acid per 100 mL.

3.6. Numerical Optimization and Mathematical Models for the Germination Process

The optimization of the germination process was carried out according to the methodology proposed by Derringer and Suich [

21], optimizing the independent variables within the studied ranges. Statistically significant dependent variables were set as maximum values, and each response was assigned an importance level (where 1 and 5 represented the lowest and highest levels of importance, respectively).

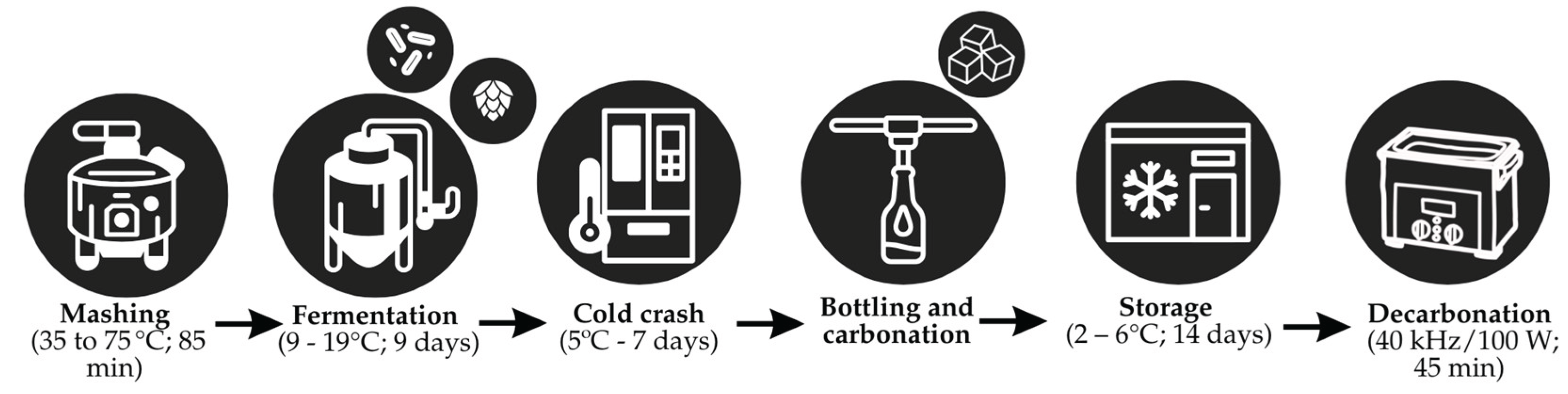

3.7. Lager Beer Production

The optimal point for the germination process was previously explored through a Central Composite Rotational Design and applied to the beer production process, following the methodology described by Venturini Filho [

22] and illustrated in

Figure 1. After cooling the wort, lyophilized yeast SalAle WB-06 (batch 1900274, Algist Bruggeman, Belgium) and Columbus hops with an alpha-acid content of 15.6% (batch I-00391-1) were added. The initial fermentation occurred at 9 °C for 4 days, followed by an increase in temperature to 13 °C for 1 day, 17 °C for 2 days, and finally to 19 °C for 2 days. After this phase, the beer was subjected to a “cold crash” at 5 °C for 7 days. The beer was then bottled in 600 mL amber glass bottles, using the priming technique for carbonation, where a small amount of sucrose was added to the fermented beer, still containing active yeast. The bottles were sealed with metal caps and kept for fermentation, producing carbon dioxide. Subsequently, the beer was refrigerated at 4 °C for 14 days. Before physicochemical analysis, the samples were degassed in a CBU/100/3LDG low-frequency ultrasonic bath (Planatec, São Paulo, Brazil) (40 kHz/100 W) for 45 minutes.

3.7.1. Physicochemical Characterization of the Beer

The beer was evaluated for soluble solids (012/IV), total protein content (037/IV), and pH (025/IV), according to the official analytical procedures described by the Adolfo Lutz Institute [

23]. Protein content was determined using the Kjeldahl method with a nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of 6.25. Additionally, total dry extract (429/IV) and total titratable acidity (016/IV) were determined [

23]. The color was determined as described for the colorimetric evaluation of the wort.

The contents of organic acids (acetic, succinic, lactic), ethanol, and glycerol in the beer samples were separated and quantified using an HPLC system (Shimadzu®) equipped with an Aminex HPX 87H column (300 × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad®) operating at 55 °C (Model CTO-30A, Shimadzu®). Detection was performed by UV-vis detector (Model SPD-10AV, Shimadzu®) set at 210 nm. Aqueous 5 mmol H2SO4 solution (0.6 mL/min) was used as the eluent in isocratic mode. Quantification was carried out using calibration curves created from standards from Sigma-Aldrich Co., LTD. for each analyzed compound.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

The normality of the data was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data obtained from the experimental design were evaluated using Response Surface Methodology to calculate regression coefficients and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a significance level of 10% and a minimum coefficient of determination of 0.75.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate Composition

The proximate composition of red sorghum, as summarized in

Table 2, is consistent with previous reports in the literature [

24,

25]. Sorghum grains typically consist of 70-80% carbohydrates, 8-18% proteins, 1-5% lipids, and approximately 2% ash, as stated by Espitia-Hernández et al. [

24]. Chao et al. [

26] found 64.4% starch, 4.8% lipids, and 15.6% proteins in their analysis, with slight variations due to genotype, environmental conditions, and cultivation methods. The moisture content indicates that the grains were stored in optimal conditions, preventing pathogenic growth while preserving seed integrity [

27].

Ash content was comparable to that in sorghum flour used for baking [

28] with another sorghum variety. The protein levels found in this study were similar to those reported by de Oliveira et al. [

29], providing significant nutritional benefits as a gluten-free option for individuals with celiac disease, despite its relatively low digestibility [

30]. Sorghum contains several types of proteins, including albumins, globulins, prolamin and glutelin, since prolamins are represented by kafirin, the main storage protein, accounting for 70% of the seed’s protein content, and are insoluble in water [

31]. Regarding dietary fiber, sorghum contains a high percentage (~90%) of insoluble fiber, as reported by Rumler et al. [

32], with soluble fiber constituting about 10%. This high fiber content contributes to the health benefits of sorghum, particularly in promoting digestive health.

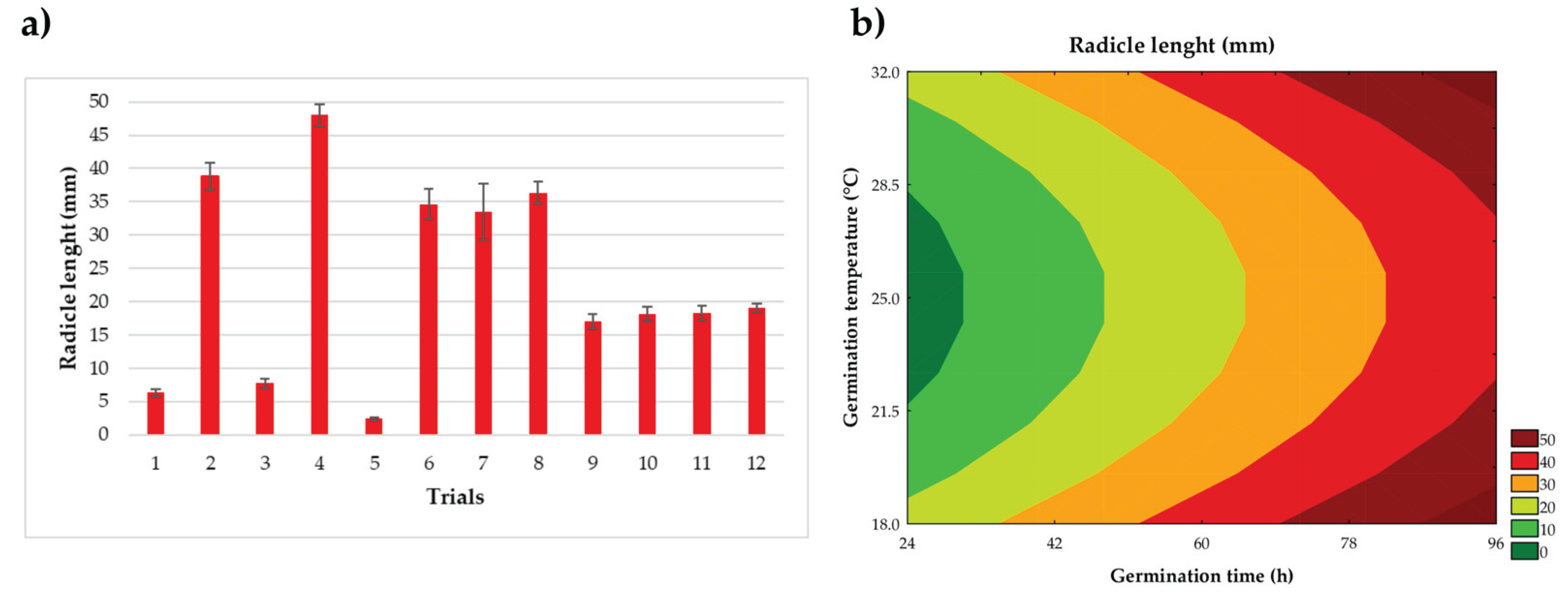

3.2. Radicle Length

Seed germination is characterized by the emergence of the radicle, with the effective germination process initiating during maceration, which breaks physiological dormancy. This stage marks the onset of enzymatic synthesis and various metabolic processes [

33]. Radicle growth is a key indicator of enzymatic activity, which in turn triggers structural, techno-functional, and quantitative modifications in seed macronutrients. In this context, time and temperature parameters are critical factors directly influencing the efficiency of this biotechnological process [

19].

The radicle length of sorghum seeds varied between 2.4 and 48.3 mm, as illustrated in

Figure 2A. The greatest impact on radicle growth was observed due to the linear effect of time (

β1 = 14.83;

P < 0.001), followed by the quadratic effect of temperature (

β22 = 8.95;

P = 0.005). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated that 92.77% of the observed variation in experimental values was explained by the predictive mathematical model (F

calc/F

tab (4; 7; 0.10) = 12.65;

P < 0.001), allowing the formulation of the mathematical model (Equation 2) and the construction of the contour curve represented in

Figure 2B.

where: x

1 and x

2 are the coded levels for germination time (h) and temperature (°C), respectively.

Based on

Table 2 and

Figure 2, the results obtained are consistent with the data reported by Andressa et al. [

34], which indicate that germination time and temperature have a positive effect on radicle growth. This physiological response is attributed to the action of endogenous enzymes present in grains, such as carbohydrases, lipases, proteases, esterases and phytases, which promote the degradation of seed reserve macronutrients, including starch, proteins, lipids, and fibers. The hydrolysis of these macronutrients results in the release of low molecular weight compounds, which are mobilized and consumed as energy sources and essential substrates for radicle growth and subsequent seedling development [

35].

3.3. Analysis of the Obtained Wort

The results obtained for the parameters of reducing sugar groups, soluble solids, total solids, soluble protein, instrumental color parameters, and total soluble phenolic compounds in the wort from germinated and non-germinated (control) sorghum are presented in

Table 3.

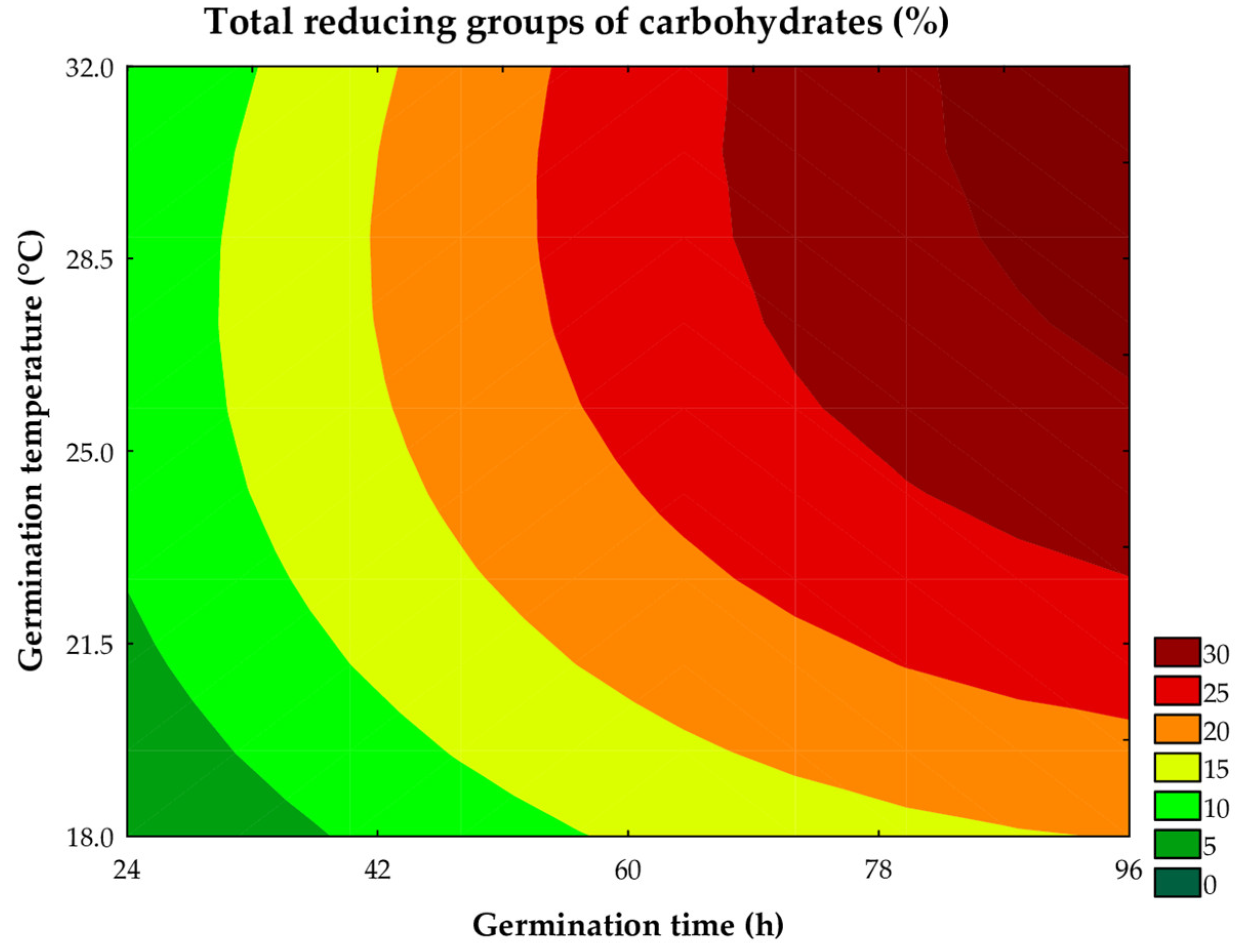

3.3.1. Reducing Sugar Group

The total reducing sugar content ranged from 1.92 to 27.57 g of glucose per 100 mL of wort across the trials, being significantly influenced by the linear terms of germination time and temperature. As illustrated in the contour curve (

Figure 3) and the mathematical model (Equation 3), the linear effect of germination time (

β1 = 7.81;

P < 0.001) had the greatest impact on this parameter, followed by germination temperature (

β2 = 4.15; P < 0.001). The interaction between time and temperature also had a significant influence (

β12 = 1.71;

P = 0.004), indicating that the combination of these variables promotes an increase in total reducing sugar groups. The predictive mathematical model explained 75.91% of the observed variability, with a F

calc/F

tab (5; 6; 0.10) ratio = 1.22 and

P < 0.068.

where: x

1 and x

2 are the coded levels for germination time (h) and temperature (°C), respectively.

The increase in total reducing sugars is directly related to the action of endogenous amylolytic enzymes synthesized during the germination process. These enzymes hydrolyze the α-1,4-D-glucosidic bonds in starch, resulting in the formation of smaller sugars such as maltodextrin, glucose, maltose, maltotriose, and maltotetrose [

10]. The results obtained corroborate the increases in solids content and radicle growth observed, as the samples with larger radicles, soluble solids, and total solids also showed higher concentrations of total reducing sugars (Trials #2, #4, #6, and #8). This finding suggests the action of endogenous amylolytic enzymes, given that sorghum is composed mainly of starch (~70%), one of the primary macronutrients responsible for providing energy to the embryo.

In addition to imparting a sweet taste to the wort, the increase in reducing sugar content is technologically relevant because these compounds are easily metabolized by yeast during fermentation, serving as rapidly assimilated substrates, which favor the fermentation process. This is particularly advantageous to produce probiotic beverages and beer.

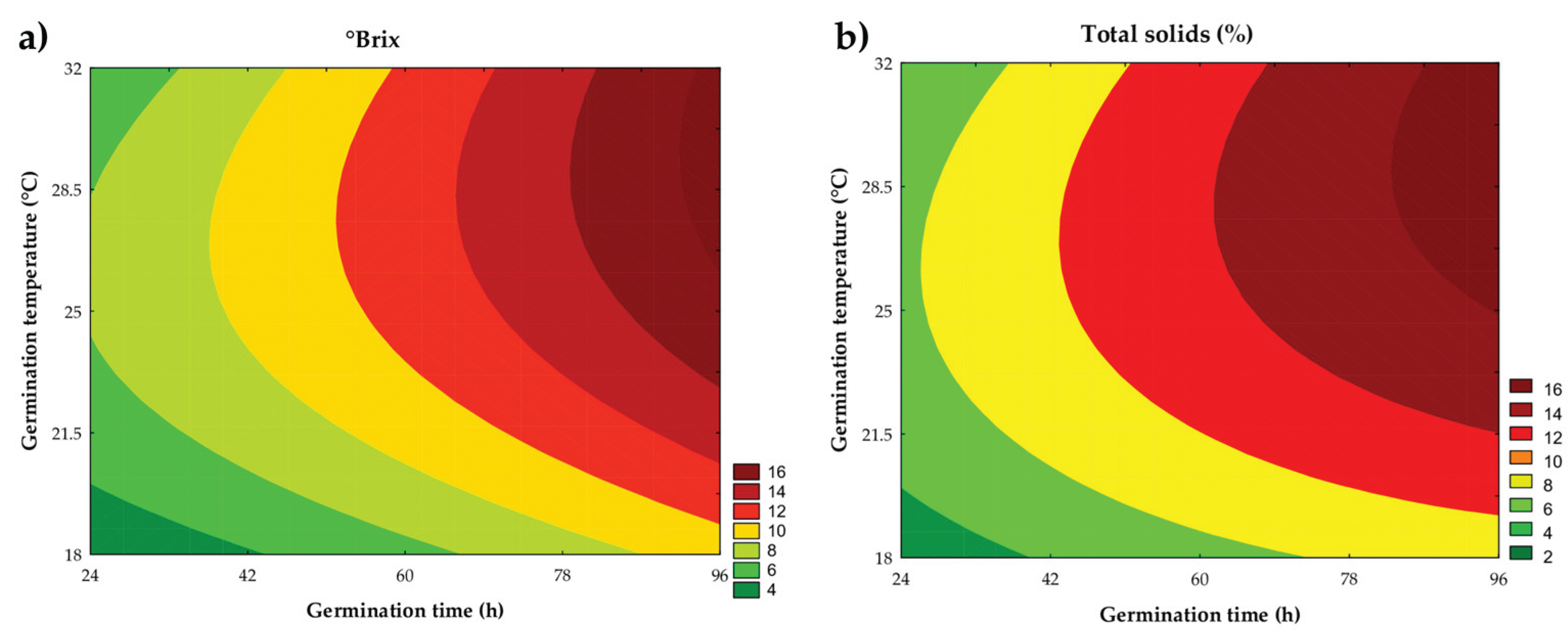

3.3.2. Total and Soluble Solids

Total and soluble solids ranged from 4.74% to 13.88% and from 2.20 °Brix to 16.20 °Brix, respectively, across the trials. Both parameters were adequately described by the fitted mathematical models, which explained 76.54% and 77.36% of the experimental variability, respectively. The Fcalc/Ftab (5; 6; 0.10) ratios were 1.53 and 1.32, with P = 0.063 and 0.058, indicating that the models are suitable for predicting the experimental data.

According to the contour plots (

Figure 4a and

Figure 4b) and the respective mathematical models (Equations 4 and 5), it was observed that the linear effects of time (

β1 = 2.27 and

β1 = 3.32;

P < 0.001) and germination temperature (

β2 = 1.31 and

β2 = 1.72;

P < 0.001) had a significant and positive influence on both parameters, showing an increase in solids content with the increment of these variables. Additionally, a significant effect of the binary interaction between time and temperature (

β12 = 0.59 and

β12 = 0.70;

P = 0.013) was identified, indicating that the combination of higher times and temperatures enhanced the accumulation of solids in the samples. In the case of soluble solids, the quadratic term of time was also significant (

β11 = 0.10;

P = 0.030), suggesting a growing trend in soluble solids content even with prolonged germination times.

where: x

1 and x

2 are the coded levels for germination time (h) and temperature (°C), respectively.

During germination, endogenous enzymes act on the hydrolysis of macronutrients such as proteins, starch, fibers, and lipids, intending to provide energy to the embryo and promote radicle development. This process results in the formation of low molecular weight compounds, which are leached into the aqueous phase of the system. The solubilization of these compounds is facilitated by residual enzymatic action throughout mashing, as temperature variations during the ramps provide ideal conditions for the activity of enzymes typical of germinated grains, such as hemicellulases (optimal temperature: 40–45 °C), exopeptidases (optimal temperature: 40–50 °C), endopeptidases (optimal temperature: 50–60 °C), dextrinases (optimal temperature: 55–60 °C), β-amylases (optimal temperature: 60–65 °C), and α-amylases (optimal temperature: 70–75 °C) [

22]. The increase in solids content is important because these solids serve as substrates for the microorganisms of interest, enhancing the efficiency of the fermentation process.

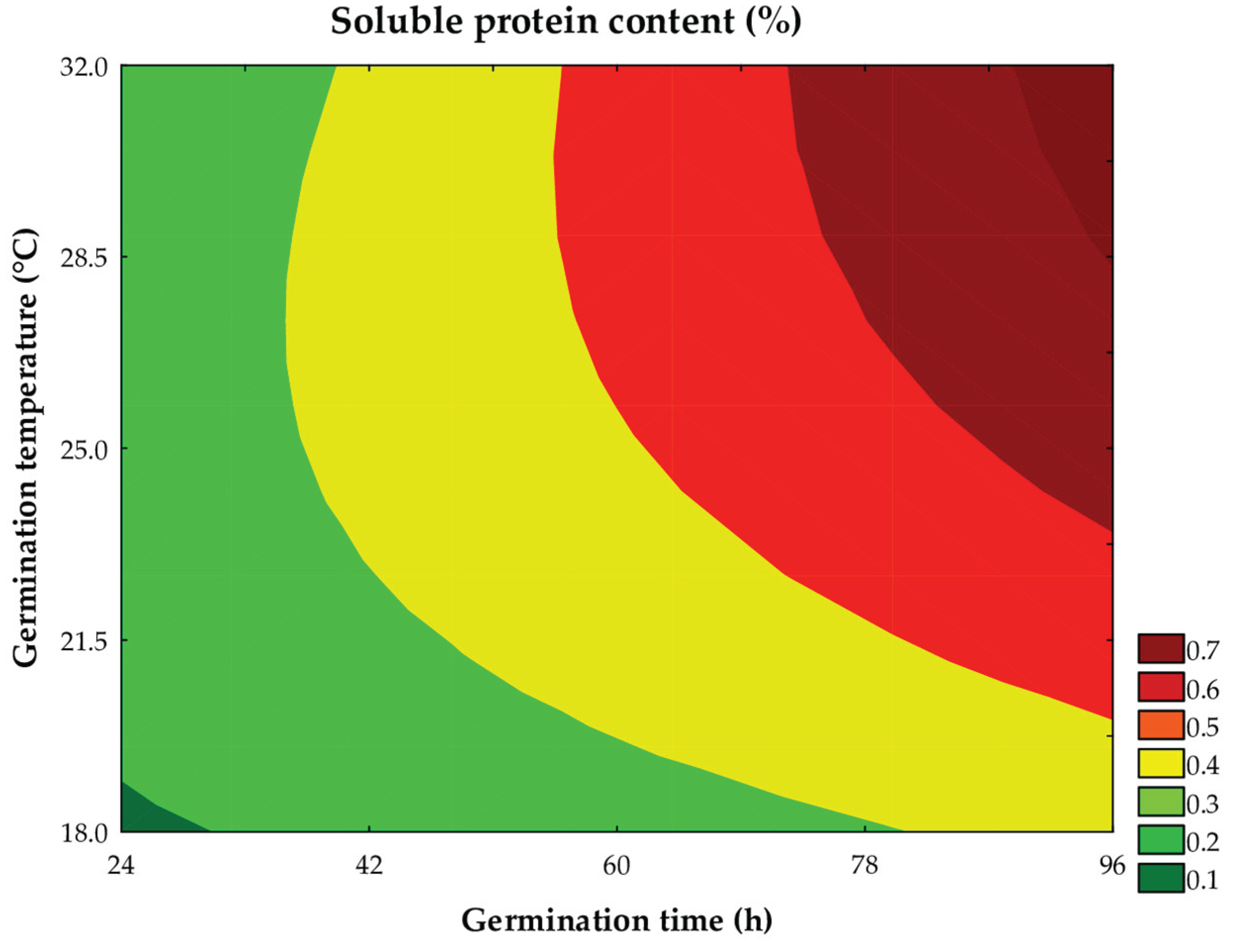

3.3.3. Soluble Proteins

As shown in

Table 3, the soluble protein content in the sorghum wort ranged from 0.30 to 0.56%. According to Equation 3, the linear terms of time (

β1 = 0.11;

P < 0.001) and temperature (

β2 = 0.05;

P < 0.001) of germination had the greatest positive impacts on soluble protein content, followed by the interaction between these variables (

β12 = 0.03;

P = 0.002). The analysis of variance (ANOVA) explained 86.63% of the variation observed in the experimental data (F

calc/F

tab (5; 6; 0.10) = 2.50;

P < 0.013), allowing the construction of the contour plot (

Figure 5) and the mathematical model (Equation 6).

where: x

1 and x

2 are the coded levels for germination time (h) and temperature (°C), respectively.

The increase in protein solubility with the increase in germination time and temperature is corroborated by the observed radicle growth. Cereal proteins generally exhibit low solubility in aqueous media, limiting protein concentration in the wort (Pacheco et al., 2024). During germination, the action of endogenous proteases promotes the hydrolysis of proteins, providing essential carbon sources for embryo development. Germination facilitates the leaching of proteins from the flour into the aqueous phase, increasing the soluble protein content of the wort [

36,

37]. In the present study, an increase of ~70% (Trial #4) in protein solubility was observed compared to the non-germinated sample. This increase was more pronounced in the trials conducted under higher germination times and temperatures, conditions that favored the degradation of storage proteins and their subsequent diffusion into the aqueous phase.

At lower temperatures, a reduction in the total soluble protein content was observed, due to the embryo catabolism not being adequately compensated by enzymatic hydrolysis [

38], which is impaired under unfavorable thermal conditions, as evidenced in Trial 7. Additionally, excessively long germination times may lead to a decrease in protein content in the extracts due to more intense protein catabolism, favoring the growth of the radicle and the seedling. In parallel, proteolysis may lead to the formation of bioactive peptides [

33] and an increase in protein digestibility [

39].

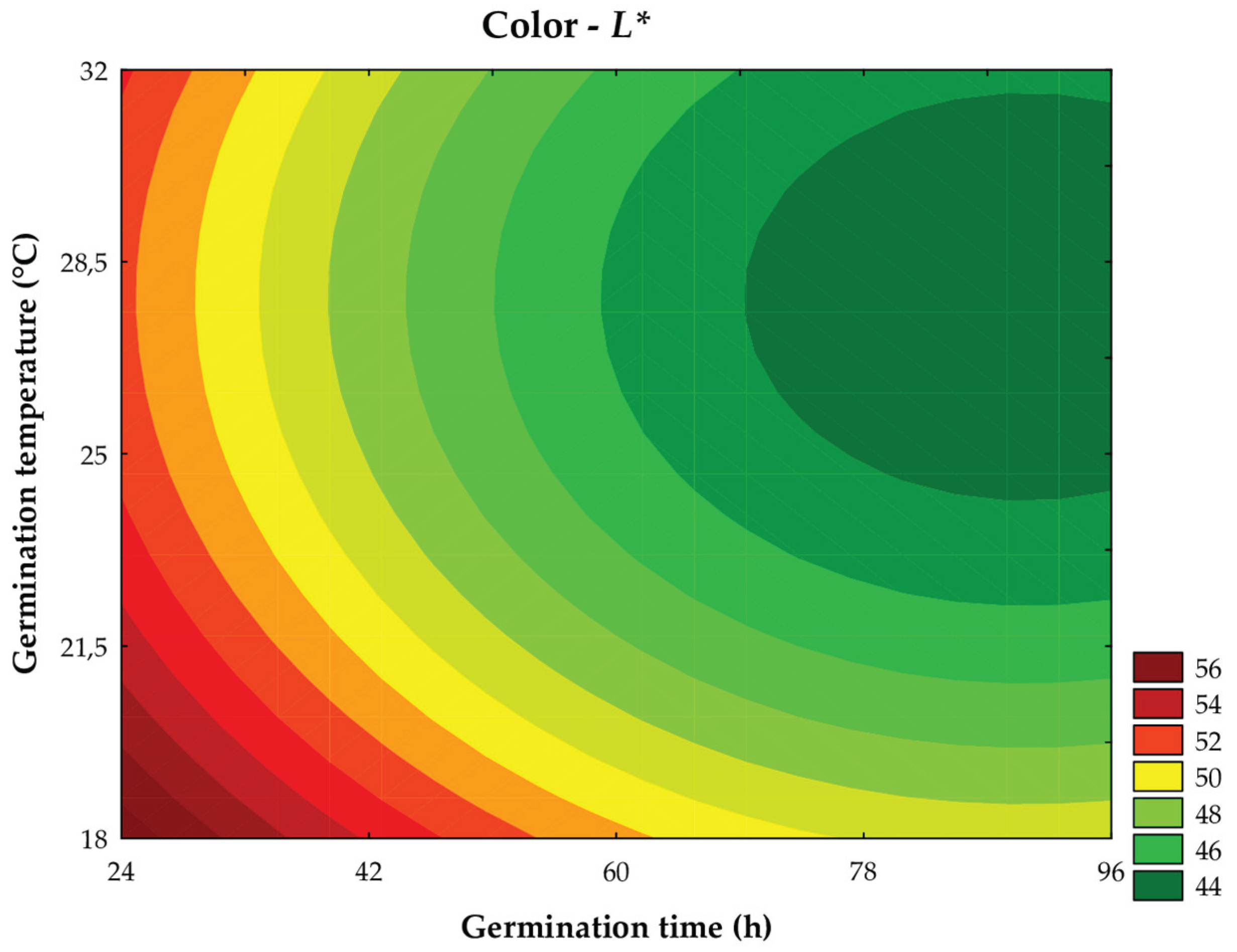

3.3.4. Instrumental Color Parameters

Regarding the instrumental color parameters of the wort obtained from germinated sorghum, the luminosity (

L*) was negatively influenced by germination time, in its linear effect (

β1 = −2.82;

P < 0.001), and positively by the quadratic effect (

β11 = 1.21;

P = 0.010), indicating an initial reduction followed by a slight increase in

L* values. Temperature showed a similar effect, with a negative linear effect (

β2 = −1.59;

P = 0.003) and a positive quadratic effect (

β22 = 1.37;

P = 0.007), suggesting variations in luminosity under the different tested conditions. These results were explained by the predictive mathematical model in 89.89% (F

calc/F

tab (5; 6; 0.10) = 4.03; P = 0.004), allowing for the formulation of the mathematical model (Equation 8) and the contour curve (

Figure 7).

where: x

1 and x

2 are the coded levels for germination time (h) and temperature (°C), respectively.

Luminosity (

L*) reflects the clarity of the sample, ranging from 0 (absolute black) to 100 (absolute white or maximum luminosity). The variation in

L* values can be attributed to the turbidity of the samples. According to Pacheco et al. [

40], the germination process, by promoting the partial hydrolysis of polysaccharides and proteins, reduces the size of molecules and alters their polarity, making some compounds more soluble, thus reducing the turbidity of the wort.

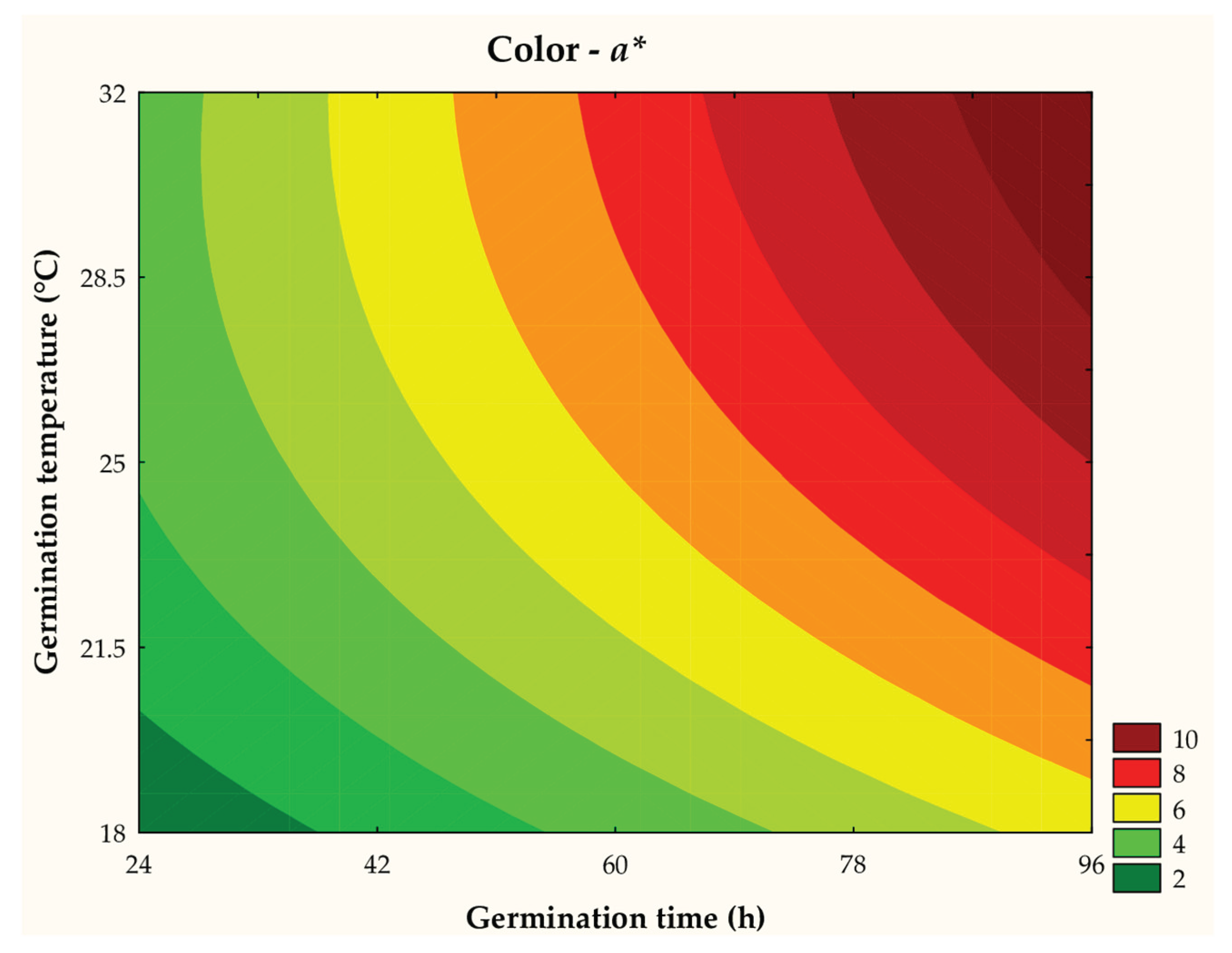

The

a* parameter ranged between 1.31 and 9.20 in the different trials. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that 83.05% of the results were explained by the predictive mathematical model, with an F

calc/F

tab (4; 7; 0.10) ratio = 2.90 and

P = 0.008. As illustrated in the contour curve (

Figure 8) and the mathematical model (Equation 9), the

a* parameter was significantly influenced by the linear effects of time (

β1 = 2.10;

P < 0.001) and germination temperature (

β2 = 1.42;

P < 0.001), increasing

a* values. Additionally, a significant linear interaction between time and temperature was observed (

β12 = 0.44;

P < 0.001), indicating that the combination of longer times and higher temperatures favored the increase in red coloration intensity, as evidenced in the samples with higher red color intensity.

where: x

1 and x

2 are the coded levels for germination time (h) and temperature (°C), respectively.

The anthocyanins, responsible for the reddish color of the red sorghum wort, are glycosylated compounds located in the pericarp fiber of the grains, with low solubility in aqueous media. Furthermore, these anthocyanins are thermolabile and sensitive to environmental conditions during the germination process, such as prolonged exposure to moisture and oxygen. Thus, the increase in red hue (+a*) in the samples can be attributed to the greater solubility of anthocyanins, resulting from endogenous enzymatic action favored by longer germination times and higher temperatures.

The b* values ranged from 5.70 to 12.65, while ΔE ranged from 3.08 to 9.08 in the trials. However, the analyzed variables did not exert a significant influence on these parameters, as indicated by the ANOVA, which revealed that the models could not adequately describe the data variability. For the b* parameter, the coefficient of determination (R2) was 73.28%, with P = 0.090, and for ΔE, the R2 was 37.92%, with P = 0.625. These results indicate the limitations of the fitted models, making it unfeasible to construct reliable mathematical equations for these variables.

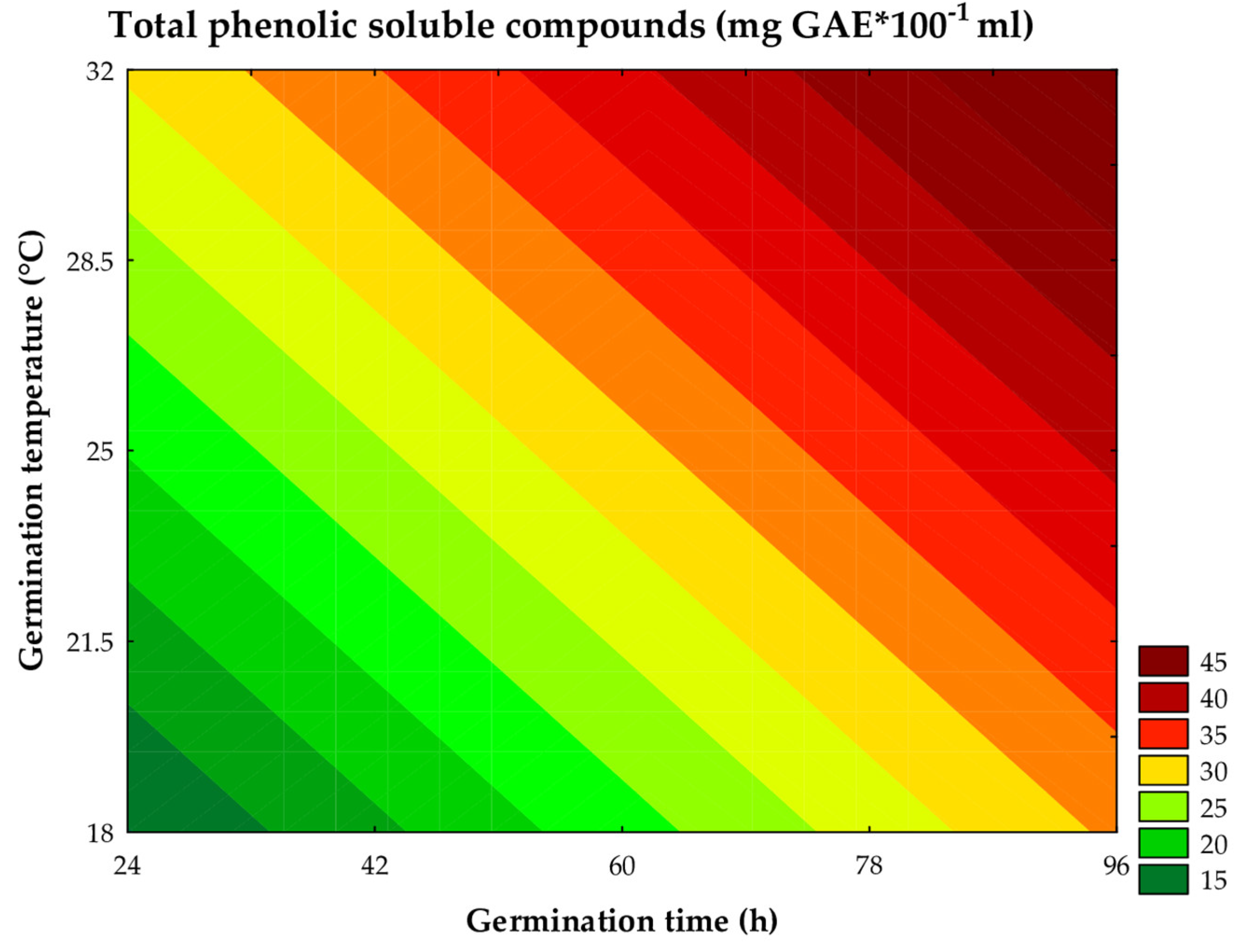

3.3.5. Total Soluble Phenolic Compounds

The total soluble phenolic compound content in the worts ranged from 16.90 to 39.16 mg of GAE per 100 mL of wort. This parameter was significantly influenced by the linear effects of germination time (

β1 = 6.41;

P < 0.001) and germination temperature (

β2 = 5.21;

P < 0.001), showing a consistent increase in these compounds with the increase of these variables. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated that the fitted model was statistically significant and predictive, explaining 79.53% of the variability in the experimental data (F

calc/F

tab (4; 7; 0.10) = 2.30;

P = 0.015). These results allowed for the construction of the contour curve (

Figure 10) and the mathematical model (Equation 11).

where: x

1 and x

2 are the coded levels for germination time (h) and temperature (°C), respectively.

During germination, the activation of endogenous enzymes, such as cellulases, esterases, and phytases, promotes the degradation of the grain’s cell wall, resulting in the phenolic decomplexation of the cellular matrix. This process increases the solubility of phenolic compounds in the aqueous phase [

12]. Sorghum germination alters the balance between free and bound phenolic compounds, with other enzymes also activating the biosynthesis pathways of phenolic compounds, such as the phenylpropanoid pathway, which may increase the concentrations of soluble polyphenols in the germinated grains [

2]. In the present study, it was observed that these enzymes were favored by the increase in germination time and temperature, as evidenced in trials #2, #4, # 6, and #8.

In the trials conducted with shorter germination times and temperatures (Trials #7 and #5), a substantial reduction in the total phenolic compound content was observed compared to the standards. This decrease can be attributed to the leaching of phenolic compounds during the maceration stage, suggesting that conditions unfavorable to enzymatic activity may lead to a reduction in the total phenolic content.

3.4. Numerical Optimization

For the optimization of the sorghum seed germination process, aimed at the preparation of the wort, the parameters of time and temperature were defined within a specific range, with an importance factor of 3. The dependent variables that showed statistical significance, with suitable predictive mathematical models (P < 0.10; F

calc/F

tab > F

tab and R

2 > 0.80), were maximized, except for luminosity, which was minimized.

Table 4 presents the importance values assigned to each dependent variable, all classified with an importance value of 5.

According to

Table 4, the optimal conditions for the germination process were determined to be 30.7 °C for 94.5 hours. The optimal temperature found falls within the ideal range for sorghum germination, although it may vary depending on the variety of sorghum used. However, temperatures above 37°C may be unfavorable to germination, as they cause a drastic reduction in the biochemical activity of reserve proteins due to partial enzymatic denaturation. This effect significantly compromises seed vigor and the synthesis of low molecular weight compounds [

1].

3.5. Gluten-Free Ale Beer Characterization

Based on the previously determined optimal germination conditions, the wort was prepared for beer production. The physicochemical properties of the beer are detailed in

Table 5.

3.5.1. Physicochemical Properties of the Gluten-Free Ale Beer

The total soluble solids content of the sorghum beer was lower than that found by Coulibaly et al. [

41], who reported values of 2.36 °Brix for sorghum tchapalo beer. The difference may be explained by variations in fermentation time, the characteristics of the sorghum variety, and the climatic conditions during its cultivation.

The total dry extract content of the beer, related to the sugar consumption by yeast during fermentation, was similar to that reported by Bayoi and Etoa [

42], who studied the traditional sorghum beer mpedli supplemented with aqueous extract of Vernonia amygdalina. The soluble protein content was low compared to the data from Akpoghelie et al. [

43], who observed a minimum value of 0.30%. The reduction in protein content during fermentation suggests the bioconversion of proteins into simpler forms for yeast growth and the formation of metabolites that contribute to the development of color and flavor [

44]. The solubility of the proteins was also enhanced by germination, increasing the bioavailability of amino acids and the digestibility of proteins [

1,

7].

The total titratable acidity of the beer was quantified at 2.50% (v/v), a considerably high value compared to industrial beers, which typically have values between 0.18 and 0.47% [

45]. This difference can be attributed to the chemical composition of the raw material (sorghum), which differs from traditional cereals such as barley, wheat, and corn.

The pH of the beer obtained after fermentation was characterized as acidic, reflecting the synthesis of organic acids as secondary metabolic products of the yeast [

46].The observed pH value agrees with the results obtained by Akpoghelie et al. [

43], who found a pH of 3.87 for sorghum beer after 192 hours of fermentation. However, these values are lower than those reported in other studies, which reported pH values between 4.60 and 4.89 for sorghum beers, with or without malting [

47]. The pH is a critical parameter because it affects the aging and stability of the beer. From a sensory perspective, pH values above 4.0 can alter the flavor, promoting “biscuity” and “toasty” notes, and if it exceeds 4.4, it may impart caustic and soapy notes [

48].

The color of the beer is an important sensory attribute related to its typology and quality. The sorghum beer exhibited a slightly dark hue, with a yellowish color but with a subtle reddish tendency, due to the tannin content present in the sorghum, which may have been hydrolyzed during malting [

49], leaching into the wort. Compared to other beers, the color of the sorghum beer resembles that of Weissbier and Altbier, particularly in the

L* and

b* parameters. These beers are characterized by a typical turbidity (

L* ~ 60) compared to Lager beers (

L* ~ 90), making them sensorially more full-bodied and intense. The

a* parameter suggests that the sorghum beer is similar to Amber beer, which has a more reddish color. However, the values of

a* and

b* should be evaluated together, as their interaction is more significant in describing the color of the beverage.

During fermentation, the yeasts produce organic acids, such as acetic, lactic, and succinic acids, which are essential for the beer’s sensory profile. Glycerol and ethanol are also produced, significantly impacting flavor and texture [

50]. In the sorghum beer, 0.145 ± 0.02 g·L

−1 of acetic acid, 0.40 ± 0.01 g·L

−1 of succinic acid, and 0.23 ± 0.02 g·L

−1 of lactic acid were found, concentrations similar to those observed in Pale Ale beers [

50]. Acetic acid, described as sharp and pungent, should not exceed 0.2 g·L

−1 to ensure sensory quality. The concentration observed in this study is within the acceptable limit. Succinic acid contributes to salty and bitter flavors, while lactic acid, resulting from the deprotonation of pyruvate by yeast, adds a mild astringency and pungency to the beer’s flavor, giving it an interesting sensory profile.

The ethanol concentration generated by fermentation depends on factors such as the amount of available sugars, fermentation temperature, and micronutrients in the medium. The sorghum beer obtained exhibited 2.56 ± 0.03% ethanol (v/v), classifying it as a light or low-alcohol beer, which traditionally contains between 2 to 4% (v/v) ethanol [

51].

4. Conclusions

The effects of germination time and temperature on the physicochemical and technological properties of sorghum grains and the resulting worts were positively demonstrated. The germination process yielded worts with elevated levels of low molecular weight carbohydrates and peptides, as indicated by the measurements of soluble solids, total solids, total reducing sugars, and soluble proteins. Additionally, germination facilitated the solubilization of phenolic compounds into the aqueous phase and contributed to increased brightness and reddish hue (+a*), which suggested a reduction in turbidity and the leaching of anthocyanins from the grain pericarp. The hydrolysis of sorghum flour components was enhanced by the activity of endogenous enzymes during germination, including hemicellulases, exopeptidases, endopeptidases, dextrinases, and amylases. Their activity was further optimized by variations in time and temperature during the mashing process. The optimal germination conditions were predicted to be 30.7 °C for 94.5 hours, with a desirability of 100%. Fermentation resulted in a significant reduction in solids (~88.6%) and soluble protein (~61%) content due to the action of yeasts. The final beer exhibited a pH of 3.87 and a titratable acidity of 2.50% (v/v), characteristic of the presence of organic acids, including acetic acid (0.145 g·L−1), succinic acid (0.40 g·L−1), and lactic acid (0.23 g·L−1), contributing to a well-balanced acidic profile, favorably accepted by consumers. Furthermore, the beer displayed an appealing color, supporting the potential of sorghum as a promising alternative raw material to produce gluten-free and lightly alcoholic beverages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Marcio Schmiele; Data curation, Hugo José Martins Carvalho, Mateus Alves Araújo, Irene Andressa, Alexandre Soares dos Santos and Nathália de Andrade Neves; Formal analysis, Hugo José Martins Carvalho, Cristiane Teles Lima, Amaury Bento Junqueira Villela, Mateus Alves Araújo, Irene Andressa and Alexandre Soares dos Santos; Funding acquisition, Marcio Schmiele; Investigation, Hugo José Martins Carvalho, Cristiane Teles Lima, Amaury Bento Junqueira Villela, Mateus Alves Araújo, Irene Andressa, Alexandre Soares dos Santos, Nathália de Andrade Neves and Marcio Schmiele; Methodology, Hugo José Martins Carvalho, Cristiane Teles Lima, Amaury Bento Junqueira Villela, Mateus Alves Araújo, Irene Andressa, Alexandre Soares dos Santos, Nathália de Andrade Neves and Marcio Schmiele; Project administration, Nathália de Andrade Neves and Marcio Schmiele; Resources, Marcio Schmiele; Software, Hugo José Martins Carvalho, Alexandre Soares dos Santos and Nathália de Andrade Neves; Supervision, Marcio Schmiele; Validation, Hugo José Martins Carvalho, Cristiane Teles Lima, Amaury Bento Junqueira Villela, Mateus Alves Araújo, Alexandre Soares dos Santos, Nathália de Andrade Neves and Marcio Schmiele; Visualization, Hugo José Martins Carvalho, Cristiane Teles Lima, Amaury Bento Junqueira Villela, Mateus Alves Araújo, Irene Andressa, Alexandre Soares dos Santos, Nathália de Andrade Neves and Marcio Schmiele; Writing – original draft, Hugo José Martins Carvalho, Irene Andressa, Alexandre Soares dos Santos and Nathália de Andrade Neves; Writing – review & editing, Marcio Schmiele.

Funding

This research was founded by the Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys and the Institute of Science and Technology through financial assistance (grant #23086.001699/2022-41), and by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) financial support (grant #001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data obtained in this study is available in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, the Institute of Science and Technology and the University of Campinas for their institutional support. The authors also express their gratitude to the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for the scholarship awarded to M. A. A. (#88887.990587/2024-00) and I. A. (#88887.677794/2022–00).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AACCI |

American Association of Cereal Chemists International |

| GAE |

Gallic Acid Equivalent (Equivalente de Ácido Gálico) |

| SP |

Soluble Protein |

| SS |

Soluble Solids |

| TGR |

Total Reducing Groups |

| TS |

Total Solids |

References

- Rodríguez-España, M.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.Y.; Figueroa-Cárdenas, J. d. D.; Rayas-Duarte, P.; Hernández-Estrada, Z.J. Effects of Germination and Lactic Acid Fermentation on Nutritional and Rheological Properties of Sorghum: A Graphical Review. Curr Res Food Sci 2022, 5, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, S.; Singh, B. Effect of Germination Time and Temperature on the Functionality and Protein Solubility of Sorghum Flour. J Cereal Sci 2017, 76, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Anunciação, P.C.; Cardoso, L. d. M.; Queiroz, V.A.V.; de Menezes, C.B.; de Carvalho, C.W.P.; Pinheiro-Sant’Ana, H.M.; Alfenas, R. d. C.G. Consumption of a Drink Containing Extruded Sorghum Reduces Glycaemic Response of the Subsequent Meal. Eur J Nutr 2018, 57, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paiva, C.L.; Netto, D.A.M.; Queiroz, V.A.V.; Gloria, M.B.A. Germinated Sorghum (Sorghum Bicolor L.) and Seedlings Show Expressive Contents of Putrescine. LWT 2022, 161, 113367. [Google Scholar]

- Awika, J.M.; Rooney, L.W. Sorghum Phytochemicals and Their Potential Impact on Human Health. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 1199–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Arouna, N.; Gabriele, M.; Pucci, L. The Impact of Germination on Sorghum Nutraceutical Properties. Foods 2020, 9, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.; Simpalo-Lopez, W.E.; Verona-Ruiz, W.D.; Lavado-Cruz, A.; Martínez-Villaluenga, A.; Peñas, C.; Frias, E.; Schmiele, J.; María Paucar-Menacho, L.; Castillo-Martínez, W.E.; et al. Performance of Thermoplastic Extrusion, Germination, Fermentation, and Hydrolysis Techniques on Phenolic Compounds in Cereals and Pseudocereals. Foods 2022, 11, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Ansi, W.; Fadhl, J.A.; Abdullah, A.B.; Al-Adeeb, A.; Mahdi, A.A.; Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Mushtaq, B.S.; Fan, M.; Li, Y.; Qian, H.; et al. Effect of Highland Barely Germination on Thermomechanical, Rheological, and Micro-Structural Properties of Wheat-Oat Composite Flour Dough. Food Biosci 2023, 53, 102521. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, S.S.; Anunciação, P.C.; Cardoso, L. d. M.; Della Lucia, C.M.; de Carvalho, C.W.P.; Queiroz, V.A.V.; Pinheiro Sant’Ana, H.M. Stability of B Vitamins, Vitamin E, Xanthophylls and Flavonoids during Germination and Maceration of Sorghum (Sorghum Bicolor L.). Food Chem 2021, 345, 128775. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelbost, L.; Bonicel, J.; Morel, M.H.; Mameri, H. Investigating Sorghum Protein Solubility and in Vitro Digestibility during Seed Germination. Food Chem 2024, 439, 138084. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Xu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Huang, X.; Zou, Y.; Yang, T. Effects of Germination on the Nutritional Properties, Phenolic Profiles, and Antioxidant Activities of Buckwheat. J Food Sci 2015, 80, H1111–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D’Almeida, C.T. dos S.; Abdelbost, L.; Mameri, H.; Ferreira, M.S.L. Tracking the Changes and Bioaccessibility of Phenolic Compounds of Sorghum Grains (Sorghum Bicolor (L.) Moench) upon Germination and Seedling Growth by UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS. Food Res. Int. 2024, 193, 114854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kayisoglu, C.; Altikardes, E.; Guzel, N.; Uzel, S. Germination: A Powerful Way to Improve the Nutritional, Functional, and Molecular Properties of White- and Red-Colored Sorghum Grains. Foods 2024, 13, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ualema, N.J.M.; dos Santos, L.N.; Bogusz, S.; Ferreira, N.R. From Conventional to Craft Beer: Perception, Source, and Production of Beer Color—A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Foods 2024, 13, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, R.; Caballero, I.; Nimubona, D.; Blanco, C.A. Brewing with Starchy Adjuncts: Its Influence on the Sensory and Nutritional Properties of Beer. Foods 2021, 10, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACCI (American Association of Cereal Chemists International). (2010). Approved Methods of Analysis. 11.ed. St. Paul.

- Rodrigues, M.I.; Iemma, A.F. Experiment Planning and Process Optimization: A Sequential Planning Strategy, 3rd ed.; Casa do Pão: Campinas, SP, Brazil, 2014; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Andressa, I.; Neves, N. d. A.; do Nascimento, G.K.S.; dos Santos, T.M.; Teotônio, D. d. O.; Rodrigues, S.M.; Costa Sobrinho, P. d. S.; Rocha, L. d. O.F.; Leite Junior, B.R. d. C.; Benassi, V.M.; et al. Production of Symbiotic Non-Dairy Beverage Fermented by Lactobacillus Sp. Using a Water-Soluble Extract from Sprouted Purple Creole Corn and Xylo-Oligosaccharides from Corncobs. J Food Sci Technol 2025, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, G.K.S. do; Silva, M.S.; Andressa, I.; Fagundes, M.B.; Vendruscolo, R.G.; Oliveira, J.R.; Barcia, M.T.; Benassi, V.M.; Neves, N. d. A.; Lima, C.T.; et al. A New Advancement in Germination Biotechnology of Purple Creole Corn: Bioactive Compounds and In Situ Enzyme Activity for Water-Soluble Extract and Pan Bread. Metabolites 2024, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, P.J.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Amigo, L.; Frias, J. Maximising the Phytochemical Content and Antioxidant Activity of Ecuadorian Brown Rice Sprouts through Optimal Germination Conditions. Food Chem 2014, 152, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Derringer, G.; Suich, R. Simultaneous Optimization of Several Response Variables. J. Qual. Technol. 1980, 12, 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bortoletto, A.M.; Alcarde, A.R.; Nascimento, E.S. (Eds.) . Alcoholic Beverages: Science and Technology. 1; Blucher: São Paulo, Brazil, 2020; Available online: https://www.blucher.com.br/bebidas-alcoolicas_9788521204923 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- IAL – Adolfo Lutz Institute. Analytical Standards of the Adolfo Lutz Institute: Chemical and Physical Methods for Food Analysis, 3rd ed.; IAL: São Paulo, Brazil, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Espitia-Hernández, P.; Chávez González, M.L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Dávila-Medina, D.; Flores-Naveda, A.; Silva, T.; Chacón, R.; Sepúlveda, L.; Espitia-Hern Andez, P.; Ch Avez Gonz Alez, L.; et al. Sorghum (Sorghum Bicolor L.) as a Potential Source of Bioactive Substances and Their Biological Properties. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 2269–2280. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, W.; Ali, A.; Arshad, M.S.; Afzal, F.; Akram, R.; Siddeeg, A.; Kousar, S.; Rahim, M.A.; Aziz, A.; Maqbool, Z.; et al. Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds of Sorghum Bicolor L. Used to Prepare Functional Foods: A Review on the Efficacy against Different Chronic Disorders. Int J Food Prop 2022, 25, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, C.; Liang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Gidley, M.J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S. New Insight into the Effects of Endogenous Protein and Lipids on the Enzymatic Digestion of Starch in Sorghum Flour. Foods 2024, 13, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komalasari, O.; Arief -, R.; Hardiansyah, M.Y.; K Amas, A.N.; Musa, Y.; Saudi, A.H.; Al-Rawi -, A.; Arief, R.; Koes, F. Influence of Seed Priming on Germination Characteristics of Sorghum (Sorghum Bicolor L. Moench). IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021, 911, 012086. [Google Scholar]

- Trappey, E.F.; Khouryieh, H.; Aramouni, F.; Herald, T. Effect of Sorghum Flour Composition and Particle Size on Quality Properties of Gluten-Free Bread. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2015, 21, 188–202. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, L. d. L.; de Oliveira, G.T.; de Alencar, E.R.; Queiroz, V.A.V.; de Alencar Figueiredo, L.F. Physical, Chemical, and Antioxidant Analysis of Sorghum Grain and Flour from Five Hybrids to Determine the Drivers of Liking of Gluten-Free Sorghum Breads. LWT 2022, 153, 112407. [Google Scholar]

- de Morais Cardoso, L.; Pinheiro, S.S.; Martino, H.S.D.; Pinheiro-Sant’Ana, H.M. Sorghum (Sorghum Bicolor L.): Nutrients, Bioactive Compounds, and Potential Impact on Human Health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017, 57, 372–390. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, H.; Li, Z.; Leng, C.; Lu, C.; Luo, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Shang, L.; Jing, H.C. Sorghum Breeding in the Genomic Era: Opportunities and Challenges. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 1899–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Rumler, R.; Bender, D.; Marti, A.; Biber, S.; Schoenlechner, R. Investigating the Impact of Sorghum Variety and Type of Flour on Chemical, Functional, Rheological and Baking Properties. J Cereal Sci 2024, 116, 103881. [Google Scholar]

- Andressa, I.; Amaral e Paiva, M.J. do; Pacheco, F.C.; Santos, F.R.; Cunha, J.S.; Pacheco, A.F.C.; Neves, N. d. A.; Vendruscolo, R.G.; Schmiele, M.; Tribst, A.A.L.; et al. Germination as a Strategy to Improve the Characteristics of Flour and Water-Soluble Extracts Obtained from Sunflower Seed. Food Biosci 2024, 61, 104763. [Google Scholar]

- Andressa, I.; Kelly, G.; Nascimento, S.; Monteiro, T.; Santos, D.; Oliveira, J.R.; Machado Benassi, V.; Schmiele, M. Physicochemical Changes Induced by the Germination Process of Purple Pericarp Corn Seeds. Braz. J. Dev. 2023, 9, 8051–8070. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, M.D.; Salinas Alcón, C.E.; Lobo, M.O.; Sammán, N. Andean Crops Germination: Changes in the Nutritional Profile, Physical and Sensory Characteristics. A Review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2024, 79, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.; Miao, S.; Xie, W. The Effect of Germination Time on Soymilk Odor: Key Odor Compounds and Formation Mechanisms. LWT 2025, 118045. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, D.B.; da Silva Júnior, S.I.; Seriani Chiarotto, A.B.; Cardoso, T.M.; Neto, J.A.; Lopes dos Reis, G.C.; Glória, M.B.A.; Tavano, O.L. The Germination of Soybeans Increases the Water-Soluble Components and Could Generate Innovations in Soy-Based Foods. LWT 2020, 117, 108599. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; He, L.; Liu, L. Effect of Different Conditions on the Germination of Coix Seed and Its Characteristics Analysis. Food Chem X 2024, 22, 101332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- do Nascimento, L.Á.; Abhilasha, A.; Singh, J.; Elias, M.C.; Colussi, R. Rice Germination and Its Impact on Technological and Nutritional Properties: A Review. Rice Sci 2022, 29, 201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, F.C.; Andressa, I.; Pacheco, A.F.C.; Santos, F.R. dos; Cunha, J.S.; Neves, N. d. A.; Vendruscolo, R.G.; Schmiele, M.; Paiva, P.H.C.; Tribst, A.A.L. Impact of Ultrasound-Assisted Intermittent Hydration during Pumpkin Seed Germination on the Structure, Nutritional, Bioactive, Physical and Techno-Functional Properties of Flours. LWT 2025, 222, 117654. [Google Scholar]

- Coulibaly, W.H.; Tohoyessou, Y.M.G.; Konan, P.A.K.; Djè, K.M. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activities of Two Industrial Beers Produced in Ivory Coast. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19168. [Google Scholar]

- Bayoï, J.R.; Etoa, F.X. Changes in Physicochemical Properties, Microbiological Quality and Safety Status of Pasteurized Traditional Sorghum “Mpedli” Beer Supplemented with Bitter Leaf (Vernonia Amygdalina) Aqueous Extract during a Month-Storage at Room Temperature. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100278. [Google Scholar]

- Akpoghelie, P.O.; Edo, G.I.; Akhayere, E. Proximate and Nutritional Composition of Beer Produced from Malted Sorghum Blended with Yellow Cassava. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 45, 102535. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Bergenståhl, B.; Nilsson, L. Interfacial Properties and Interaction between Beer Wort Protein Fractions and Iso-Humulone. Food Hydrocoll 2020, 103, 105648. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, J.; Lunkes, A.; Steinheusen, G.; Heckler, P.; Drun, B. Determination of Total Acidity in Industrial Beers. In Proceedings of the XI Seminar on Extension and Innovation; UTFPR: Guarapuava; UTFPR: Guarapuava, PR, Brazil, 2021. Available online: https://eventos.utfpr.edu.br/sei/sei2021/paper/viewFile/8890/4177 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Stewart, A.T.M.; Mysore, K.; Njoroge, T.M.; Winter, N.; Feng, R.S.; Singh, S.; James, L.D.; Singkhaimuk, P.; Sun, L.; Mohammed, A.; et al. Demonstration of RNAi Yeast Insecticide Activity in Semi-Field Larvicide and Attractive Targeted Sugar Bait Trials Conducted on Aedes and Culex Mosquitoes. Insects 2023, 14, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciocan, M.E.; Salamon, R.V.; Ambrus, Á.; Codină, G.G.; Chetrariu, A.; Dabija, A. Brewing with Unmalted and Malted Sorghum: Influence on Beer Quality. Fermentation 2023, 9, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.; Badocco, D.; Cappellin, L.; Tubiana, M.; Pastore, P. Real-Time Monitoring of the PH of White Wine and Beer with Colorimetric Sensor Arrays (CSAs). Food Chem 2024, 452, 139513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, E.V.; Santos, F.G.; Queiroz, V.A.V.; Capriles, V.D. A Decade of Evidence of Sorghum Potential in the Development of Novel Food Products: Insights from a Bibliometric Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Viana, R.; May, A.; Moreira, B.R. d. A.; Cruz, V.H.; Junior, N.A.V.; Moura da Silva, E.H.F.; Simeone, M.L.F. Addition of Glycerol to Agroindustrial Residues of Bioethanol for Fuel-Flexible Agropellets: Fundamental Fuel Properties, Combustion, and Potential Slagging and Fouling from Residual Ash. Ind Crops Prod 2023, 192, 116134. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Yin, R.; Xie, J.; Hong, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, X.; Guo, L.; Song, Y.; Zhao, D. Exploring the Key Effects of Non-Volatile Acid Compounds on the Expression of Dominant Flavor in Lager Beer Using Flavor Matrix and Molecular Docking. 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).