Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Identify the countries and authors with the highest focus on artificial intelligence in the AEC industry in the last 10 years,

- Identify the most cited published works and sources on artificial intelligence in the AEC industry in the last 10 years,

- Map out research focus on artificial intelligence in the AEC industry in the last 10 years; and

- Identify the research trends in artificial intelligence in the AEC industry.

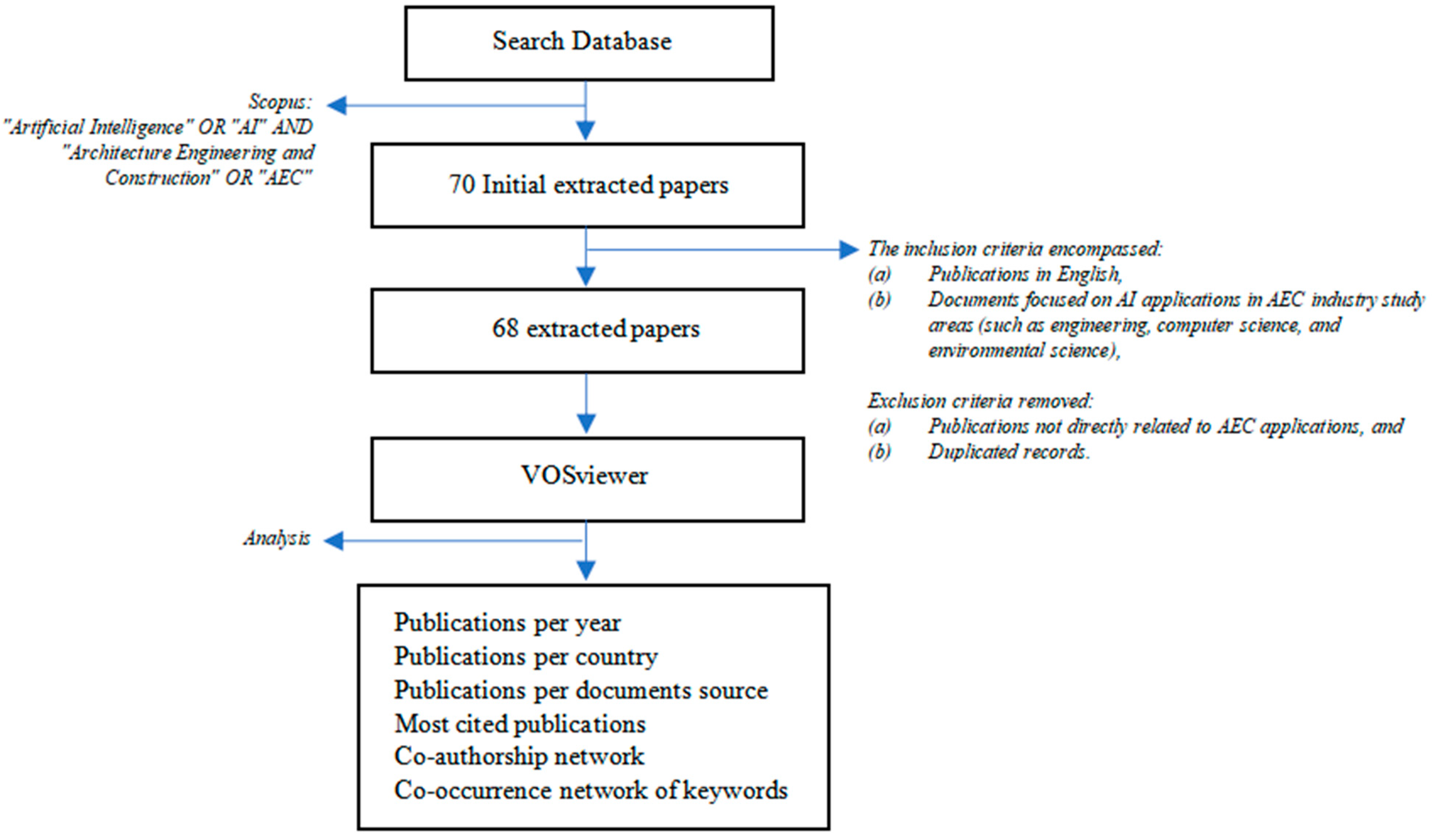

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Types of Analyses Performed

- Publication Trends Analysis: Examining the temporal distribution of publications to identify research growth patterns over the past 10 years, including analysis by country or region.

- Source Analysis: Evaluating the distribution of publications across different journals and conference proceedings to identify key venues for AI in AEC research.

- Citation Analysis: Examining citation patterns to identify influential publications and authors, including both document citation analysis and author citation analysis [25].

- Authorship and Co-authorship Analysis: Investigating collaboration patterns between authors to identify key research clusters and collaborative networks [26].

- Keyword Co-occurrence Analysis: Analyzing relationships between keywords to identify major research themes and their evolution over time, effectively mapping the conceptual structure of the research field [27].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Publication Trends Analysis

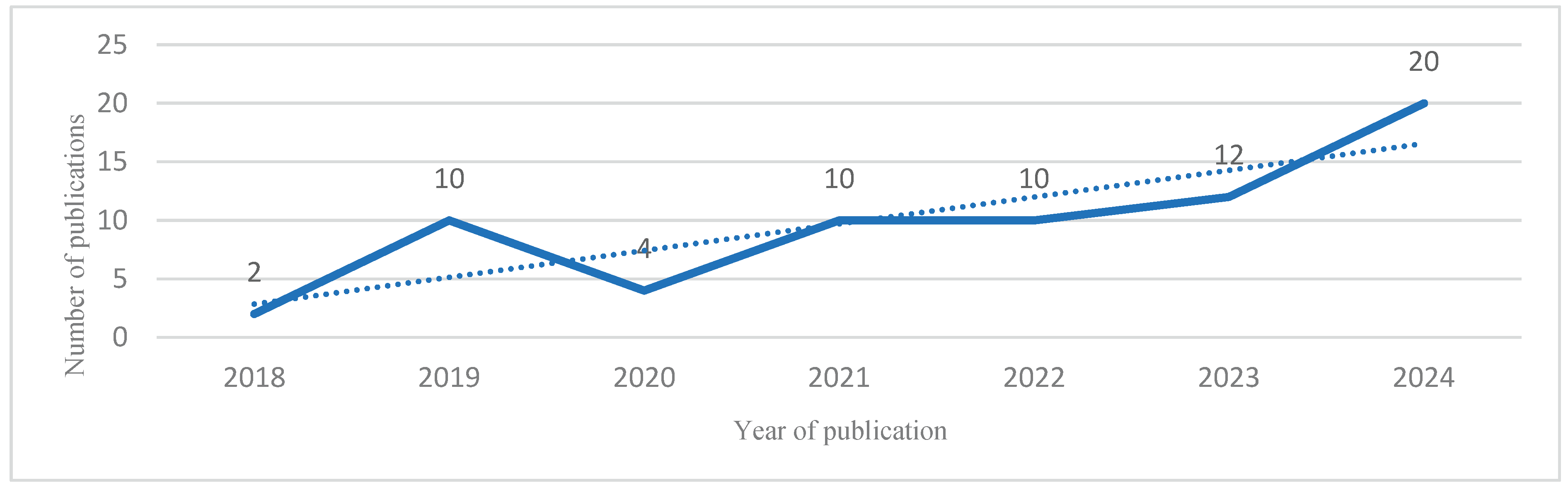

3.1.1. Publications per Year

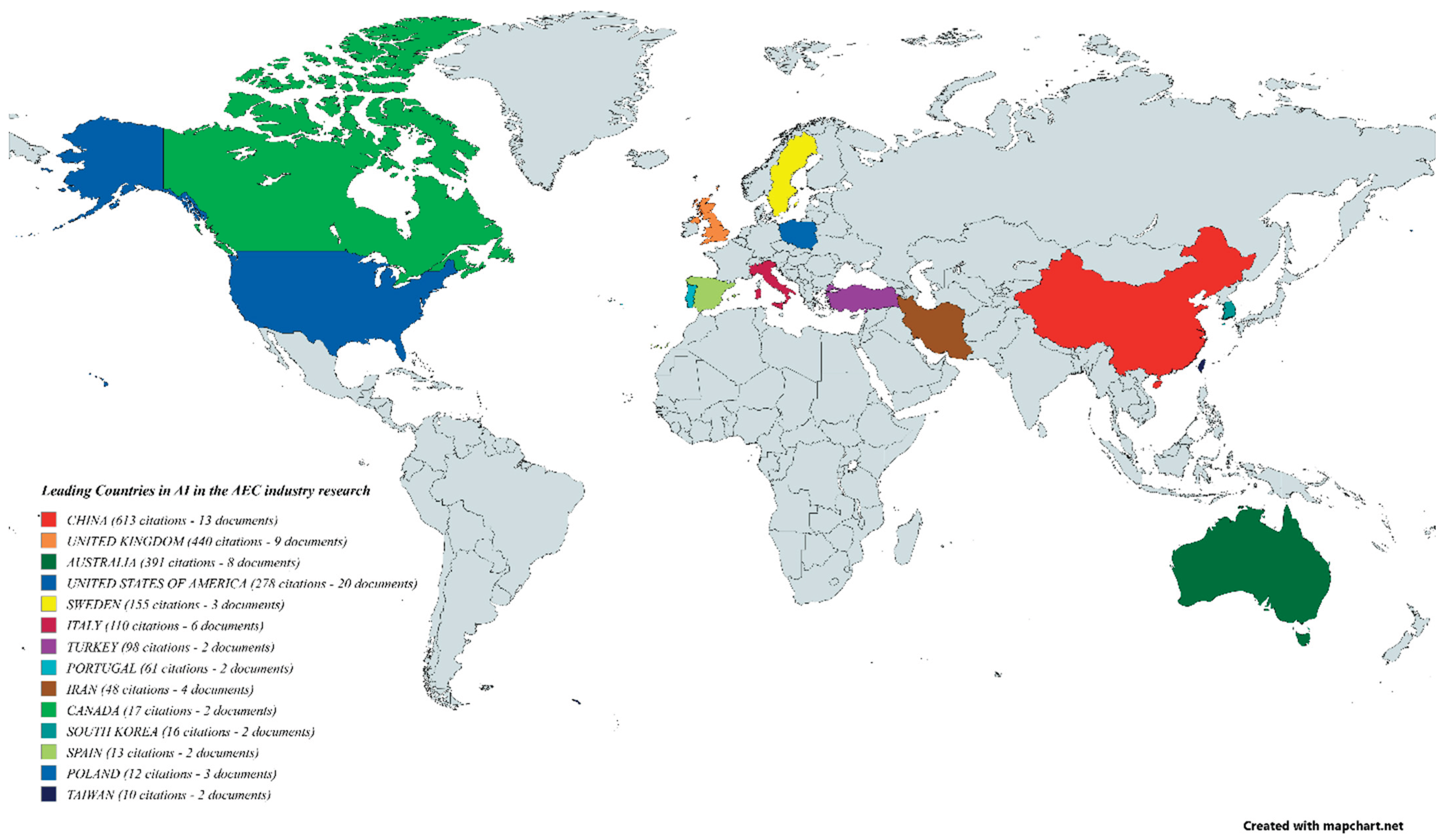

3.1.2. Publications per Country

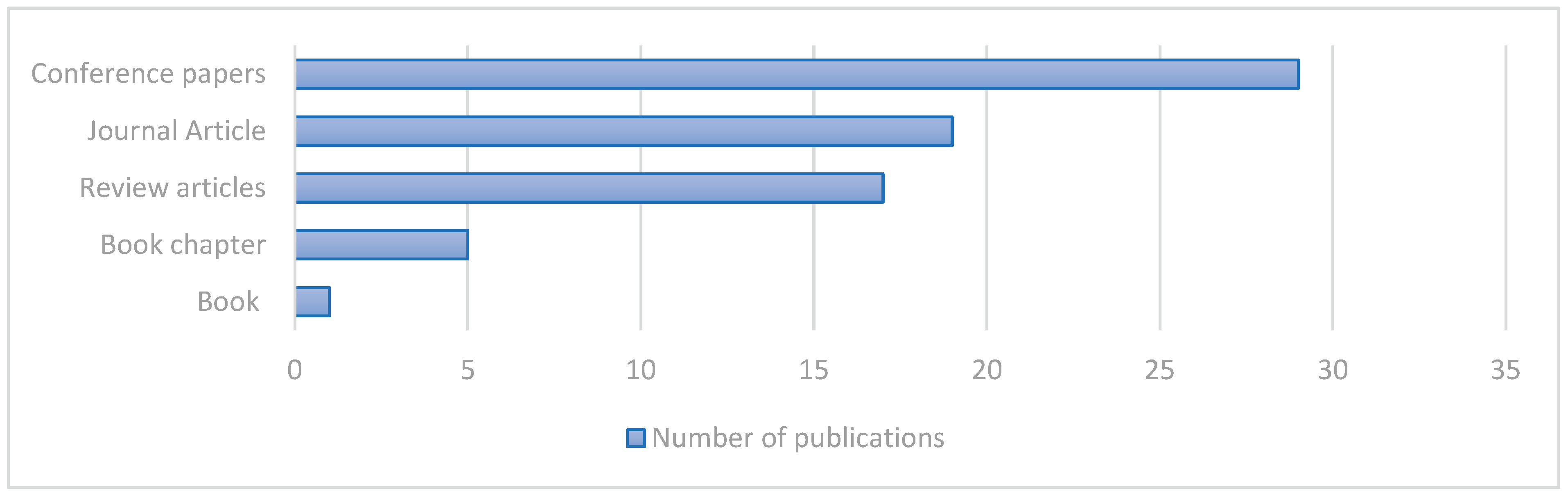

3.2. Source Analysis

3.3. Citation Analysis

3.4. Authorship and Co-Authorship Analysis

3.5. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

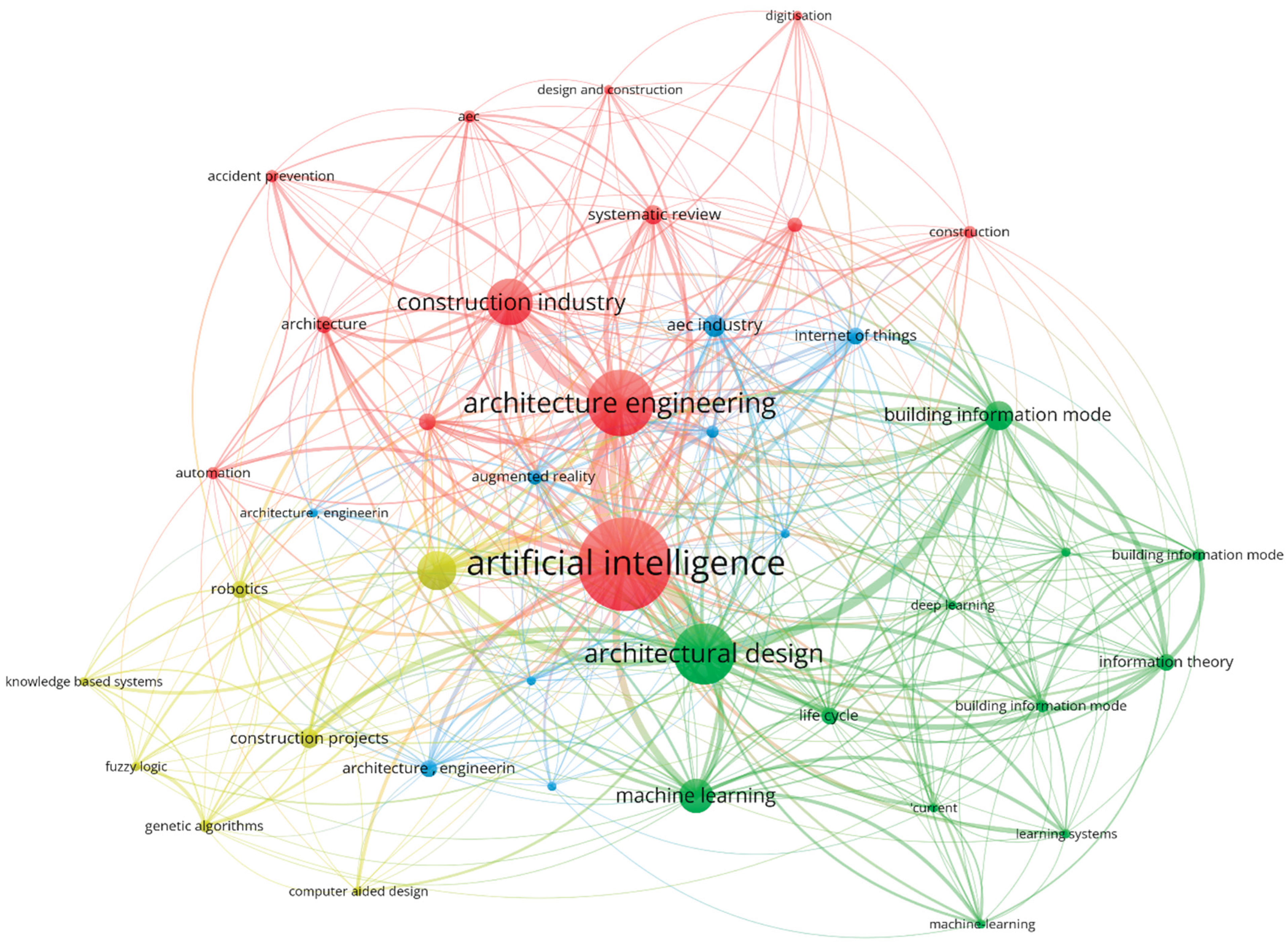

3.5.1. Research Focus Based on Co-Occurring Keywords

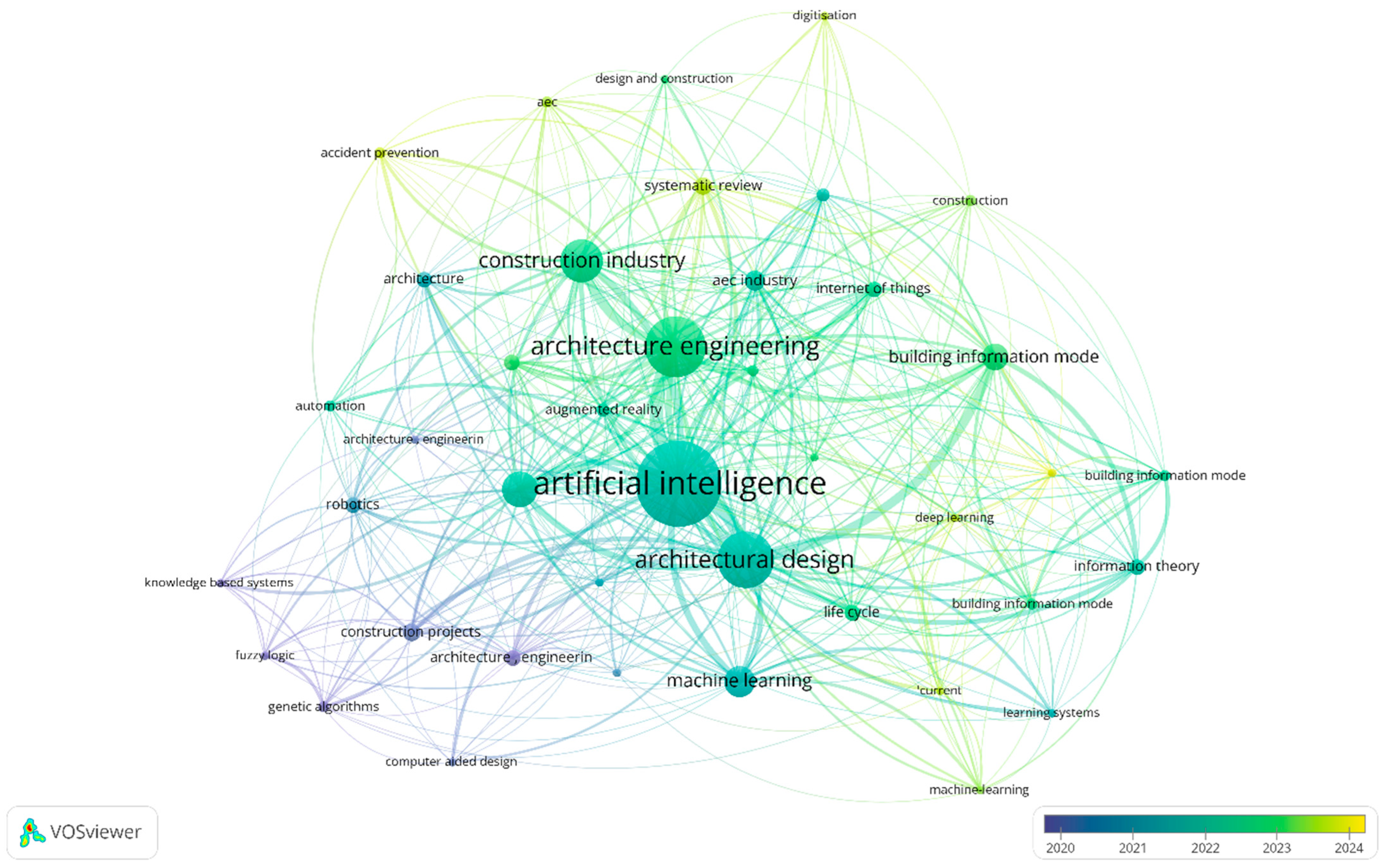

3.5.2. Research Focus Based on the Year of Publication

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

- Standardization Initiatives: There is a pressing need for the development of standardized frameworks for AI implementation in AEC. Future research should focus on creating industry-wide standards for data collection, AI model development, and implementation protocols to facilitate broader adoption.

- Cross-Regional Collaboration: Efforts should be made to promote research collaboration between established and emerging regions in AI-AEC research. This could help address the current geographical disparities and ensure AI solutions are applicable across diverse construction contexts.

- Integration of Ethics and Safety: As AI applications become more sophisticated, future research should prioritize the development of ethical guidelines and safety protocols specific to AI use in construction. This includes addressing issues of data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the responsible implementation of AI in safety-critical construction applications.

- Education and Training: The industry should invest in developing comprehensive education and training programs to prepare the workforce for AI integration. This includes both technical skills development and fostering an understanding of AI's capabilities and limitations in construction contexts.

- Interdisciplinary Approach: Future research should emphasize interdisciplinary collaboration, particularly between construction professionals, computer scientists, and ethicists, to ensure AI solutions are both technically sound and responsibly implemented.

- Validation and Verification: There is a need for more research on methods to validate and verify AI systems in construction applications, ensuring their reliability and safety in real-world settings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adewale, B. A.; Onyedikachi, V. E.; Ogunbayo, B. F.; Aigbavboa, C. O. A Systematic Review of the Applications of AI in a Sustainable Building’s Lifecycle. Buildings 2024, 14, 2137. [CrossRef]

- Haenlein, M.; Kaplan, A. A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence: On the Past, Present, and Future of Artificial Intelligence. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 5–14. [CrossRef]

- Aghimien, D. O.; Aigbavboa, C. O.; Oke, A. E. Digitalisation for Effective Construction Project Delivery in South Africa. In Proceedings of the Contemporary Construction Conference: Dynamic and Innovative Built Environment (CCC2018), Coventry, United Kingdom, 5–6 July 2018; pp. 3–10.

- Statista. Revenues from the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Software Market Worldwide from 2018 to 2025. Statista Research Department. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/607716/worldwide-artificial-intelligence-market-revenues/ (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Oesterreich, T. D.; Teuteberg, F. Understanding the Implications of Digitisation and Automation in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Triangulation Approach and Elements of a Research Agenda for the Construction Industry. Comput. Ind. 2016, 83, 121–139. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, L. Roles of Artificial Intelligence in Construction Engineering and Management: A Critical Review and Future Trends. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103517. [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A. P.; Adabre, M. A.; Edwards, D. J.; Hosseini, M. R.; Ameyaw, E. E. Artificial Intelligence in the AEC Industry: Scientometric Analysis and Visualization of Research Activities. Autom. Constr. 2020, 112, 103081. [CrossRef]

- Sholanke, A. B.; Opoko, A. P.; Onakoya, A. O.; Adigun, T. F. Awareness Level and Adoption of Modular Construction for Affordable Housing in Nigeria: Architects’ Perspective. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 251–257. [CrossRef]

- Suleman, T. A.; Ezema, I. C.; Aderonmu, P. A. Exploring the Opportunities in Circular Design as an Affordable Housing Solution in Nigeria. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1369, 012037. [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.; Ibem, E. O.; Ezema, I. C. Implementation of Lean Practices in the Construction Industry: A Systematic Review. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 34–43. [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.; Ibem, E. O.; Ezema, I. C. Lean Construction: An Approach to Achieving Sustainable Built Environment in Nigeria. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1299, 012007. [CrossRef]

- Aghimien, D. O.; Aigbavboa, C. O.; Oke, A. E.; Thwala, W. D. Mapping Out Research Focus for Robotics and Automation Research in Construction-Related Studies. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2019, 18, 1063–1079. [CrossRef]

- Abioye, S. O.; Oyedele, L. O.; Akanbi, L.; Ajayi, A.; Delgado, J. M. D.; Bilal, M.; Ahmed, A. Artificial Intelligence in the Construction Industry: A Review of Present Status, Opportunities, and Future Challenges. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103299. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M. R.; Martek, I.; Zavadskas, E. K.; Aibinu, A. A.; Arashpour, M.; Chileshe, N. Critical Evaluation of Off-Site Construction Research: A Scientometric Analysis. Autom. Constr. 2018, 87, 235–247. [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Costa, A. A.; Grilo, A. Bibliometric Analysis and Review of Building Information Modelling Literature Published Between 2005 and 2015. Autom. Constr. 2017, 80, 118–136. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, P.; Shen, G. Q.; Wang, X.; Teng, Y. Mapping the Knowledge Domains of Building Information Modeling (BIM): A Bibliometric Approach. Autom. Constr. 2017, 84, 195–206. [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A. Statistical Bibliography or Bibliometrics. J. Doc. 1969, 25, 348–349.

- Guz, A. N.; Rushchitsky, J. J. Scopus: A System for the Evaluation of Scientific Journals. Int. Appl. Mech. 2009, 45, 351–362. [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The Journal Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A Comparative Analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Strotmann, A. Analysis and Visualization of Citation Networks. Synth. Lect. Inf. Concepts Retr. Serv. 2015, 7, 1–207. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Chan, D. W.; Chan, A. P.; Yeung, J. F. Critical Analysis of Partnering Research Trend in Construction Journals. J. Manag. Eng. 2012, 28, 82–95. [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Oliván, J. A.; Marco-Cuenca, G.; Arquero-Avilés, R. Errors in Search Strategies Used in Systematic Reviews and Their Effects on Information Retrieval. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2019, 107. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538.

- Perianes-Rodriguez, A.; Waltman, L.; van Eck, N. J. Constructing Bibliometric Networks: A Comparison Between Full and Fractional Counting. J. Informetr. 2016, 10, 1178–1195. [CrossRef]

- Small, H. Co-Citation in the Scientific Literature: A New Measure of the Relationship Between Two Documents. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1973, 24, 265–269. [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ibekwe-SanJuan, F.; Hou, J. The Structure and Dynamics of Cocitation Clusters: A Multiple-Perspective Cocitation Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 61, 1386–1409. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Waltman, L. Large-Scale Analysis of the Accuracy of the Journal Classification Systems of Web of Science and Scopus. J. Informetr. 2016, 10, 347–364. [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. J.; López-Herrera, A. G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Science Mapping Software Tools: Review, Analysis, and Cooperative Study Among Tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 1382–1402. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, L. Integrating BIM and AI for Smart Construction Management: Current Status and Future Directions. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 30, 1081–1110. [CrossRef]

- Leontie, V.; Maha, L.; Stoian, I. C. COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Effects on the Usage of Information Technologies in the Construction Industry: The Case of Romania. Buildings 2022, 12, 166. [CrossRef]

- Mardiani, N. E.; Iswahyudi, M. S. Mapping the Landscape of Artificial Intelligence Research: A Bibliometric Approach. West Sci. Interdiscip. Stud. 2023, 1, 587–599. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, H.; Burgueño, R. Emerging Artificial Intelligence Methods in Structural Engineering. Eng. Struct. 2018, 171, 170–189. [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Zou, P. X.; Piroozfar, P.; Wood, H.; Yang, Y.; Yan, L.; Han, Y. A Science Mapping Approach-Based Review of Construction Safety Research. Saf. Sci. 2018, 113, 285–297. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Mishra, S.; Brynjolfsson, E.; Etchemendy, J.; Ganguli, D.; Grosz, B.; Lyons, T.; Manyika, J.; Niebles, J.C.; Sellitto, M.; Shoham, Y.; Clark, J.; Perrault, R. The AI Index 2021 Annual Report. AI Index Steering Committee, Human-Centered AI Institute, Stanford University, 2021.

- Pan, Y. Heading Toward Artificial Intelligence 2.0. Eng. 2016, 2, 409–413. [CrossRef]

- Dutton, T. An Overview of National AI Strategies. Politics + AI. Available online: https://medium.com/politics-ai/an-overview-of-national-ai-strategies-59dfa8f2d47a (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Saka, A.B.; Chan, D.W.M. A Scientometric Review and Metasynthesis of Building Information Modelling (BIM) Research in Africa. Buildings 2019, 9, 85. [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, J. J. Impact of Scientific, Economic, Geopolitical, and Cultural Factors on International Research Collaboration. J. Informetr. 2021, 15, 101194. [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Linner, T.; Pan, W.; Cheng, H.; Bock, T. A Framework of Indicators for Assessing Construction Automation and Robotics in the Sustainability Context. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 82–95. [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A. P.; Huo, X.; Owusu-Manu, D. A Scientometric Analysis and Visualization of Global Green Building Research. Build. Environ. 2018, 149, 501–511. [CrossRef]

- Almatared, M.; Liu, H.; Tang, S.; Sulaiman, M.; Lei, Z.; Li, H. X. Digital Twin in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction Industry: A Bibliometric Review. In Construction Research Congress 2022; pp. 670–678.

- He, Q.; Wang, G.; Luo, L.; Shi, Q.; Xie, J.; Meng, X. Mapping the Managerial Areas of Building Information Modeling (BIM) Using Scientometric Analysis. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 35, 670–685. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Lim, Y.; Sengoku, S.; Guo, X.; Kodama, K. Exploring the Shift in International Trends in Mobile Health Research from 2000 to 2020: Bibliometric Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e31097. [CrossRef]

- Yitmen, I.; Alizadehsalehi, S.; Akıner, İ.; Akıner, M. E. An Adapted Model of Cognitive Digital Twins for Building Lifecycle Management. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4276. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yuan, Y.; Tang, Y.; Tian, B. Application of Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) in the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) Industry. Sensors 2022, 22, 265. [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Sijtsema, P.; Claeson-Jonsson, C.; Johansson, M.; Roupe, M. The Hype Factor of Digital Technologies in AEC. Constr. Innov. 2021, 21, 899–916. [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, F.; Filippucci, M.; Buffi, A. Automated Design and Modeling for Mass-Customized Housing: A Web-Based Design Space Catalog for Timber Structures. Autom. Constr. 2019, 103, 13–25. [CrossRef]

- Emaminejad, N.; Akhavian, R. Trustworthy AI and Robotics: Implications for the AEC Industry. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104298. [CrossRef]

- Rafsanjani, H. N.; Nabizadeh, A. H. Towards Digital Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) Industry Through Virtual Design and Construction (VDC) and Digital Twin. Energy Built Environ. 2023, 4, 169–178. [CrossRef]

- Saka, A. B.; Oyedele, L. O.; Akanbi, L. A.; Ganiyu, S. A.; Chan, D. W.; Bello, S. A. Conversational Artificial Intelligence in the AEC Industry: A Review of Present Status, Challenges and Opportunities. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 55, 101869. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, K. G.; Noorzai, E.; Hosseini, M. R. Assessing the Capabilities of Computing Features in Addressing the Most Common Issues in the AEC Industry. Constr. Innov. 2021, 1, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, S.; Flammini, A.; Pasetti, M.; Tagliabue, L. C.; Ciribini, A. C.; Zanoni, S. Metrological Issues in the Integration of Heterogeneous IoT Devices for Energy Efficiency in Cognitive Buildings. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Houston, TX, USA, May 2018; pp. 1–6.

- Cotella, V. A. From 3D Point Clouds to HBIM: Application of Artificial Intelligence in Cultural Heritage. Autom. Constr. 2023, 152, 104936. [CrossRef]

- Zabin, A.; González, V. A.; Zou, Y.; Amor, R. Applications of Machine Learning to BIM: A Systematic Literature Review. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 51, 101474. [CrossRef]

- Opoku, D. G. J.; Perera, S.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Rashidi, M. Digital Twin Application in the Construction Industry: A Literature Review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 40, 102726. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Van Nederveen, S.; Hertogh, M. Understanding Effects of BIM on Collaborative Design and Construction: An Empirical Study in China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 35, 686–698. [CrossRef]

- Rafsanjani, H. N.; Nabizadeh, A. H. Towards Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) Industry. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2023, 11, 100319. [CrossRef]

- Jadidi, M.; Karimi, F.; Lietz, H.; Wagner, C. Gender Disparities in Science? Dropout, Productivity, Collaborations and Success of Male and Female Computer Scientists. Adv. Complex Syst. 2018, 21, 1750011. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Hou, J.; Ge, M. Research Progress and Trend Analysis of Concrete 3D Printing Technology Based on CiteSpace. Buildings 2024, 14, 989. [CrossRef]

- Forcael, E.; Ferrari, I.; Opazo-Vega, A.; Pulido-Arcas, J. A. Construction 4.0: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9755.

- Zhang, L.; Yao, H.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y. Comparing Subjective and Objective Measurements of Contract Complexity in Influencing Construction Project Performance: Survey versus Machine Learning. J. Manag. Eng. 2023, 39. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Girolami, M.; Brilakis, I. Building Information Modelling, Artificial Intelligence and Construction Tech. Dev. Built Environ. 2020, 4, 100011. [CrossRef]

- Pena, M. L. C.; Carballal, A.; Rodríguez-Fernández, N.; Santos, I.; Romero, J. Artificial Intelligence Applied to Conceptual Design: A Review of Its Use in Architecture. Autom. Constr. 2021, 124, 103550. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yi, W.; Chi, H. L.; Wang, X.; Chan, A. P. A Critical Review of Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/AR) Applications in Construction Safety. Autom. Constr. 2018, 86, 150–162. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, P.; Wang, J.; Chi, H. L.; Wang, X. A Critical Review of the Use of Virtual Reality in Construction Engineering Education and Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2018, 15, 1204. [CrossRef]

- Dave, B.; Buda, A.; Nurminen, A.; Främling, K. A Framework for Integrating BIM and IoT Through Open Standards. Autom. Constr. 2018, 95, 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Boje, C.; Guerriero, A.; Kubicki, S.; Rezgui, Y. Towards a Semantic Construction Digital Twin: Directions for Future Research. Autom. Constr. 2020, 114, 103179. [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Menassa, C. C.; Kamat, V. R. From BIM to Digital Twins: A Systematic Review of the Evolution of Intelligent Building Representations in the AEC-FM Industry. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26.

- Allcoat, D.; Hatchard, T.; Azmat, F.; Stansfield, K.; Watson, D.; Von Mühlenen, A. Education in the Digital Age: Learning Experience in Virtual and Mixed Realities. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2021, 59, 795–816. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Eastman, C.; Lee, G.; Teicholz, P. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Designers, Engineers, Contractors, and Facility Managers; 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018.

- Wang, M.; Deng, Y.; Won, J.; Cheng, J. C. An Integrated Underground Utility Management and Decision Support Based on BIM and GIS. Autom. Constr. 2019, 107, 102931. [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, H.; Henno, J.; Makela, J.; Thalheim, B. Artificial Intelligence Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. In Proceedings of the 42nd International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthi, S.; Raphael, B. A Review of Methodologies for Performance Evaluation of Automated Construction Processes. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2022, 12, 719–737. [CrossRef]

- Bock, T.; Linner, T. Construction Robots: Elementary Technologies and Single-Task Construction Robots; Vol. 3; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016.

- Delgado, J. M. D.; Oyedele, L.; Ajayi, A.; Akanbi, L.; Akinade, O.; Bilal, M.; Owolabi, H. Robotics and Automated Systems in Construction: Understanding Industry-Specific Challenges for Adoption. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26, 100868. [CrossRef]

- Maskuriy, R.; Selamat, A.; Ali, K. N.; Maresova, P.; Krejcar, O. Industry 4.0 for the Construction Industry—How Ready Is the Industry? Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2819.

- Elghaish, F.; Matarneh, S.; Talebi, S.; Kagioglou, M.; Hosseini, M. R.; Abrishami, S. Toward Digitalization in the Construction Industry with Immersive and Drones Technologies: A Critical Literature Review. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2020, 10, 345–363. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Shelden, D. R.; Eastman, C. M.; Pishdad-Bozorgi, P.; Gao, X. A Review of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and the Internet of Things (IoT) Devices Integration: Present Status and Future Trends. Autom. Constr. 2019, 101, 127–139. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, J.; Shou, W.; Ngo, T.; Sadick, A. M.; Wang, X. Computer Vision Techniques in Construction: A Critical Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 3383–3397. [CrossRef]

- Kor, M.; Yitmen, I.; Alizadehsalehi, S. An Investigation for Integration of Deep Learning and Digital Twins Towards Construction 4.0. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2022, 12, 461–487. [CrossRef]

| Source | Documents | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Automation in Construction | 6 | 495 |

| Applied Sciences (Switzerland) | 2 | 106 |

| Construction Innovation | 2 | 91 |

| Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering | 4 | 31 |

| Buildings | 4 | 11 |

| Engineering, Construction, and Architectural Management | 4 | 10 |

| Source | Title | Citations | Method | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | Artificial intelligence in the AEC industry: Scientometric analysis and visualization of research activities | 341 | Scientometric analysis, Visualization techniques | Comprehensive review of AI applications in AEC, Research trend analysis |

| [30] | Integrating BIM and AI for Smart Construction Management: Current Status and Future Directions | 108 | Literature review, Integration framework analysis | Building Information Modeling (BIM), AI integration, Construction management |

| [45] | An adapted model of cognitive digital twins for building lifecycle management | 90 | Model development, Conceptual framework | Cognitive digital twins, Building lifecycle management |

| [46] | Application of terrestrial laser scanning (Tls) in the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry | 69 | Technology application analysis | Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), AEC applications |

| [47] | The hype factor of digital technologies in AEC | 65 | Critical analysis | Digital technology hype, Impact assessment in AEC |

| [48] | Automated design and modeling for mass-customized housing. A web-based design space catalog for timber structures | 64 | Web-based modeling, Automated design | Mass-customized housing, Timber structures |

| [49] | Trustworthy AI and robotics: Implications for the AEC industry | 47 | Implications analysis | Trustworthy AI, Robotics in AEC |

| [50] | Towards digital architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry through virtual design and construction (VDC) and digital twin | 47 | Conceptual analysis | Virtual Design and Construction (VDC), Digital twin technology |

| [51] | Conversational artificial intelligence in the AEC industry: A review of present status, challenges and opportunities | 42 | Literature review | Conversational AI, Current status, and challenges |

| [52] | Assessing the capabilities of computing features in addressing the most common issues in the AEC industry | 26 | Capability assessment | Computing features, Common AEC industry issues |

| [53] | Metrological Issues in the Integration of Heterogeneous IoT Devices for Energy Efficiency in Cognitive Buildings | 23 | Metrological analysis | IoT device integration, Energy efficiency in cognitive buildings |

| [54] | From 3D point clouds to HBIM: Application of Artificial Intelligence in Cultural Heritage | 23 | AI application analysis, 3D point cloud processing | Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM), Cultural heritage preservation |

| Author | Affiliation | Documents | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hosseini, M. Reza | School of Architecture and Built Environment, Deakin University, Geelong, 3220, Australia | 2 | 367 |

| Darko, Amos | Department of Building and Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong | 2 | 341 |

| Nabizadeh, Amir Hossein | Medical Informatics Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran, INESC-ID, Lisbon, 1000-029, Portugal | 2 | 61 |

| Akhavian, Reza | Department of Civil, Construction, Environmental Engineering, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Dr., San Diego, 92182, CA, United States | 3 | 56 |

| Emaminejad, Newsha | Dept. of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering, San Diego State Univ., San Diego, 92182, CA, United States | 3 | 56 |

| Zhang, Cheng | Dept. of Construction Science and Organizational Leadership, Purdue Univ. Northwest, Hammond, IN, United States | 2 | 23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).