1. Introduction

“The Plastic Within and Without You” means plastic is in the environment (water, fish, plants, soil animals, birds) and in the body (feces, GI tissue, liver, blood, brain, placenta, testes). Humans now ingest tens of thousands of micro- and nanoplastic particles (MNPs) annually [

1]. Given its industrial success and widespread adoption, the pollution and environmental accumulation of plastics globally poses a significant risk to long-term human health. Several excellent reviews have shown that the MNP exposure results in a dysbiosis of the gut microbiome accompanied by inflammation, leaky gut and contributes to other illnesses ([

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]). MNPs cause oxidative stress, leading to cellular damage and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in various tissues (ref needed). These contributions to the inflammatory response are of broad potential health concern given their role in the development of several diseases including inflammatory bowel disease [

9], [

10,

11] and colorectal cancer [

12]. MNPs are moreover a suspected obesogen [

1]. No review articles have focused on the effects of nanoplastics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio, elevations in which correlate with obesity in some but not all studies [

13]. Recent primary studies (2020–2025) investigated how nanoplastics influence the gut microbiome’s F/B ratio across various organisms [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] and other researchers have commented on F/B shifts [

19,

20,

21]. F/B by itself, however, is a crude measure, as both phyla have important members that increase short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production. SCFA concentrations negatively correlate with obesity and dietary supplementation has been suggested as a potential intervention [

13]. The focus of this review is to document the status of research on the mechanisms of action by which MNP cause dysbiosis in the intestinal microbiome.

2. Materials and Methods

A comparative review of the literature is difficult because there are no studies that include side-by-side comparison of different plastics in the same species, using the same analysis of dysbiosis, bacteria and gut health. As of mid-2025, . ChatGPT 4.5 – assisted scoping review of the literature found an estimated ~7,300 unique publications focused on microplastic or nanoplastic research since 2020, after accounting for cross-listed papers (the search queries and sources are listed in the Supplemental Information). Of these, only about 82 MNP studies focused on the intersection of gut health and the microbiome, illustrating that this specific research area is still quite niche. ChatGPT 4.5 – assisted scoping review of the literature from 2020 through mid-2025 for review articles on MNPs effects on the gut microbiome and gut health, and primary literature exclusive of those reviews. A total of nine reviews fit the criteria (

Table 1). Primary literature with a similar focus that were not included in the reviews was exhaustively searched (130 searches in 52 sources). All content was reviewed and verified by the authors for accuracy and integrity.

3. The Intestinal Microbiome

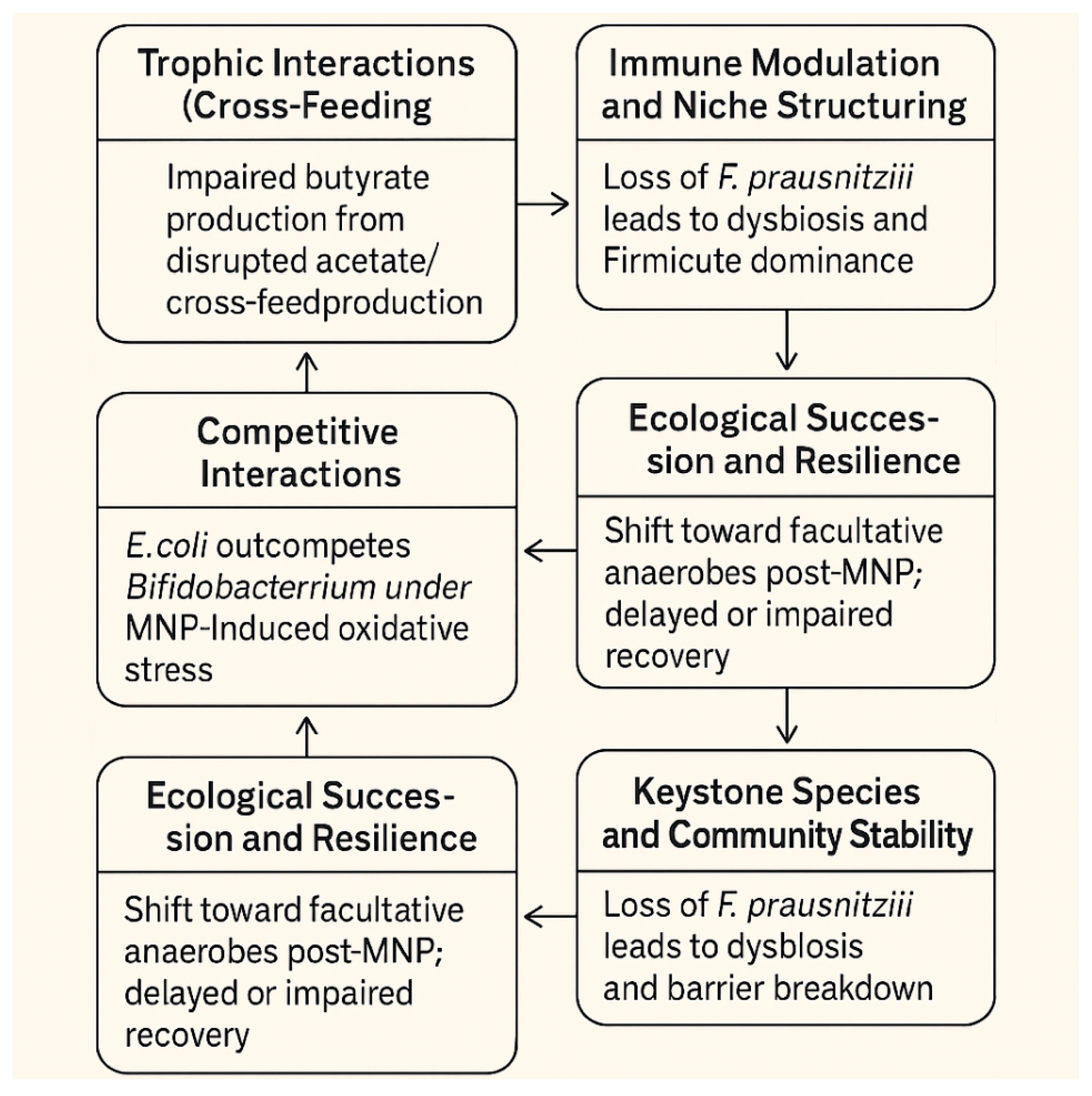

The intestinal microbiome is a highly dynamic and interconnected ecosystem composed of trillions of microorganisms, primarily bacteria. There are many ways in which

these bacteria can interact leading to numerous cascading consequences. Before discussing how

MNP effects on bacteria can impact gut health, we must understand how this inter-relatedness can impact the microbiome. The following four topics are summarized: Microbiome bacteria inter-relatedness, Niche Structuring, Keystone Species & Community Stability, and Ecological Succession & Resilience (

Figure 1).

3.1. Microbiome Bacteria Inter-Relatedness

The inter-relatedness of these bacteria is shaped by ecological interactions, metabolic dependencies, competition, and cooperation—all of which help maintain gut homeostasis and influence host health.

3.1.1. Trophic Interactions (Cross-Feeding)

Primary degrading bacteria break down complex carbohydrates (like dietary fiber) into simpler compounds. Secondary fermenters consume these byproducts (e.g., lactate, succinate) to produce SCFAs like butyrate, propionate, and acetate, which are vital for host colonocyte health and immune modulation. Bacteroidetes species degrade polysaccharides and produce acetate, which can be utilized by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii to produce butyrate.

3.1.2. Competitive Interactions

Bacteria compete for nutrients (e.g. iron, nitrogen sources, and simple sugars) within the mucosal layer or the lumen. They produce bacteriocins or short-chain fatty acids that inhibit rivals. Lactobacillus species can acidify their environment to outcompete pH-sensitive pathogens.

3.1.3. Cooperative Interactions

Some microbes co-aggregate or form biofilms for mutual benefit. Quorum sensing molecules mediate cooperation and communication across species. Akkermansia muciniphila degrades mucin and releases oligosaccharides, supporting the growth of other mucin-adapted microbes.

3.1.4. Immune Modulation and Niche Structuring

Some microbes help train the host immune system, creating niches that favor certain microbial groups. Immune responses also feedback into microbiome structure by limiting or promoting specific taxa. One well-studied example involves Bacteroides fragilis, a common gut commensal that actively shapes both the host immune response and microbial community structure. B. fragilis produces a molecule called polysaccharide A (PSA), which has profound effects on the host’s immune system. PSA promotes regulatory T cell (Treg) development, which helps maintain immune tolerance and reduce inflammation. This dampening of inflammatory responses can prevent the overgrowth of pro-inflammatory bacteria and protect against diseases like colitis.

3.2. Niche Structuring

By calming immune responses, B. fragilis creates a less hostile mucosal environment and allows for colonization by other commensals that are sensitive to inflammation. This helps structure a stable, low-inflammation microbial niche that favors beneficial anaerobes over opportunistic pathogens. In contrast, inflammation (e.g., from infections or poor diet) favors facultative anaerobes like Enterobacteriaceae, which thrive in oxygen-rich, inflamed environments. Thus, immune modulation by commensals like B. fragilis indirectly prevents this pathogenic shift, helping maintain microbial balance. This example illustrates how specific microbes do not merely live in the gut but actively shape the ecological and immunological landscape, influencing which other microbes can survive and thrive.

3.3. Keystone Species and Community Stability

Keystone species (e.g., butyrate-producers like F. prausnitzii) have disproportionate effects on microbial community structure and function. Loss of these bacteria can disrupt the entire network, leading to dysbiosis and susceptibility to disease. Here are examples of keystone species and their role in community stability within the intestinal microbiome.

3.3.1. F. prausnitzii Is a Major Butyrate-Producing Firmicute, Which Maintains Gut Barrier Integrity, and Reduces Inflammation

Its presence supports anaerobic, anti-inflammatory conditions that favor other beneficial obligate anaerobes. Loss of F. prausnitzii is associated with dysbiosis in diseases like Crohn’s.

3.3.2. A. muciniphila Is a Mucin Degrader Living in the Gut Mucus Layer

It helps maintain mucus layer homeostasis and stimulates mucin production. This action supports host-microbe mutualism which creates niche conditions that promote other mucin-adapted commensals while deterring pathogens.

3.3.3. Bacteroides the Taiotaomicron Is a Polysaccharide Specialist with a Large Glycan-Degrading Arsenal

It initiates complex carbohydrate digestion, releasing simpler metabolites for use by other microbes. This promotes metabolic diversity and resilience to dietary shifts. Removal can disrupt trophic chains and alter community structure. Without keystone species, opportunistic pathogens like Clostridioides difficile can dominate, leading to dysbiosis. Metabolic shifts such as reduced SCFA production, increased oxidative stress, and mucosal damage can occur. And the microbiome becomes less capable of recovering from perturbations (e.g., antibiotics, dietary changes).

3.4. Ecological Succession & Resilience

The microbiome evolves over time (e.g., infancy to adulthood) through stages of colonization, often dictated by pioneer species. Communities exhibit resilience by reestablishing structure after disruptions (e.g., antibiotic use), largely due to microbial interdependence.

3.4.1. Early Life Microbiome Development (Succession)

At birth, infants are colonized by facultative anaerobes like Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Escherichia coli), especially in C-section births. As oxygen levels in the gut drop, obligate anaerobes like Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, and Clostridia take over. By age 2–3 years, the microbiome becomes more diverse and functionally mature, resembling an adult-like state.

3.4.2. Antibiotic-Induced Disturbance (Resilience)

Broad-spectrum antibiotics can drastically reduce microbial diversity and disrupt functional groups (e.g., butyrate producers). Opportunistic pathogens like C. difficile may bloom in the disrupted environment. In many cases, the microbiome gradually returns to a stable state within weeks to months, especially with dietary support or probiotics. However, some individuals may require interventions like fecal microbiota transplantation for full recovery.

3.4.3. Dietary Shifts & Microbiome Plasticity

A high-fiber diet supports SCFA-producing species like Roseburia and Faecalibacterium. Switching to a high-fat, low-fiber diet rapidly favors Bilophila wadsworthia and Bacteroides species. The microbiome can often revert back to its original composition and function with reintroduction of fiber, showing ecological resilience.

3.4.4. In Summary, Succession Refers to Predictable, Staged Development or Turnover of Microbial Communities (e.g., During Early Life or After a Major Perturbation)

And resilience reflects the microbiome’s ability to bounce back to a stable, functional state after disturbances like antibiotics, infection, or diet change. The intestinal microbiome is a finely balanced web of microbial life where cooperation, competition, and cross-feeding underpin stability and function. Understanding these relationships is crucial for manipulating the microbiome for health benefits, such as through diet, probiotics, or microbiota transplantation.

4. Interaction of MNP and Bacteria

The encounter of MNPs with bacteria entails their binding to the cell wall, the damaged caused by gaining entry, and the resulting oxidative stress. These three areas of interaction are discussed in the next sections.

4.1. Binding of MNPs Can Physically Damage the Cell Membrane and Result in Membrane Permeability

MNPs can directly interact with bacterial cell envelopes, often through physical adsorption to the cell surface. This attachment can impose mechanical stress on membranes: micrometer-sized plastic beads (1–10 μm) binding to lipid bilayers cause significant membrane stretching even without any chemical or oxidative reactions [

31]. Irregularly shaped microplastics (MPs) with sharp edges and high curvature can physically damage cell membranes upon contact [

32]. Such mechanical perturbation increases membrane tension and can create nano-scale pores, elevating permeability without immediately lysing the cell [

33]. For instance, 60 nm polystyrene beads (both unmodified and with amino or carboxyl surface groups) were shown to induce membrane permeabilization (ion leakage and altered membrane potential) while maintaining overall bilayer integrity [

34]. These findings align with model membrane studies in which plastic particles increase membrane tension and reduce cell membrane stability/lifetime [

31].

4.2. Another Key Mechanism is Electrostatic Interaction Between Charged Plastics and the Bacterial Surface

Bacterial cell walls (especially Gram-positive peptidoglycan and Gram-negative lipopolysaccharide, LPS) are generally negatively charged; accordingly, positively charged nanoplastics tend to bind more avidly. In one study, amino-functionalized (cationic) 30 nm polystyrene nanoparticles attached strongly to bacterial cells, elevating intracellular oxidative stress, whereas neutral 30 nm PS caused a combination of oxidative damage and physical membrane disruption [

33]. Conversely, negatively charged (e.g. carboxylated) nanoparticles can still adsorb via hydrophobic and van der Waals forces, altering the surface charge of bacteria [

33]. Zeta potential measurements confirm that even 100 nm polystyrene (PS) beads (which carry slight negative charge) will coat both Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative Klebsiella pneumoniae cells, shielding surface charges and making the cell’s net charge less negative without outright killing the bacteria. Thus, MNP attachment alone can modify cell envelope properties (like charge and surface potential) and possibly membrane protein function, even when immediate cell death or lysis is not observed.

4.3. Particle Size Plays a Critical Role In The Depth of Interaction

Smaller nanoplastics (<100 nm) have higher surface-area-to-volume ratios and can interact more intimately with cell membranes. They exhibit enhanced Brownian motion and often penetrate closer to or even into cell envelopes [

35]. Indeed, 30 nm polystyrene (PS) nanoparticles were suggested to penetrate bacterial membranes and possibly enter cells, disrupting membrane proteins [

33]. Such nano-scale plastics (NPs) can lodge within the cell wall or periplasm of Gram-negative bacteria, compromising envelope integrity. Wamng et al. also noted that generally “interactions between bacterial cells and nanoplastics result in membrane rupture” along with downstream effects like loss of hydrolase enzyme activity and changes in surface charge [

35]. In other words, prolonged or high-concentration NP exposure can physically breach the cell envelope. By contrast, larger microplastics (several microns) usually remain external but can still cause abrasions and micro-tears in the cell wall upon contact [

32], or induce the cell to stretch around the particle [

31]. Notably, shape and surface topology influence this: irregular or fiber-shaped plastics (e.g. fragmented PET fibers) can pierce or insert into bacterial cell walls more readily than smooth spheres [

32].

4.4. Besides Mechanical Interactions, Chemical and Redox Processes Contribute to Cell Wall Damage

Broader research outlines oxidative stress pathways as a common response mechanism to nanoparticle exposure across microbes—highlighting excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation as a key toxicity pathway [

36]. Many studies report that MNPs elicit elevated ROS in bacteria, which in turn damage membrane lipids and proteins [

35]. Oxidative stress can peroxidize the lipid components of the cell membrane, increasing permeability. Studies on MNP polystyrene particles reports that they were internalized by E. coli and Bacillus sp., triggering ROS production in both bacterial types [

37,

38]. Antioxidant defenses in bacteria (e.g. superoxide dismutase, catalase) are often upregulated upon microplastic exposure as a response to ROS-induced damage. In one experiment, exposing a tilapia gut Bacillus (Firmicutes) to PS microplastics provoked a spike in intracellular ROS, forcing the bacteria to increase SOD and catalase levels [

39]. If ROS overwhelm defenses, they can compromise the cell wall: lipid peroxidation makes the membrane leaky and can trigger autolytic pathways. Thus, ROS-mediated oxidative damage is a common mechanism by which plastics harm bacterial membranes, often acting in tandem with direct contact effects.

4.5. Finally, Micro/Nanoplastics Can Impact Bacterial Biofilm Formation and Structure, Indirectly Affecting Cell Wall Integrity

When MNPs are present, bacteria may alter exopolysaccharide (EPS) production – either increasing biofilm matrix to sequester and immobilize the foreign particles or experiencing disrupted biofilm cohesion. Some studies show enhanced biofilm formation: for instance, Pseudomonas aeruginosa exposed to sub-lethal PS nanoplastics produced more EPS and formed thicker biofilms, a response linked to nanoparticle-induced ROS signaling [

40]. Similarly, gut-derived Bacillus tropicus responded to PS microplastics by overproducing EPS and actively colonizing the plastic surfaces. Scanning electron microscopy images confirmed Bacillus cells densely adhered to irregular PS fragments, encased in biofilm, which likely protects the cells’ walls from direct contact damage levels [

39]. On the other hand, plastics can also disrupt existing biofilms by adsorbing bacteria and disturbing their normal attachment to gut mucosa or other surfaces. A 2022 in vitro digestion study found that PET microplastics introduced into human gut microbial communities became coated with bacteria, suggesting microbes were pulling off from their usual niches to cling to the plastic particles [

41]. The authors hypothesize this could alter biofilm architecture and microbial spatial organization in the gut. In summary, MNPs can trigger bacteria to modify their cell wall environment – either by excess matrix production as a defense or by inadvertently causing biofilm destabilization – both of which reflect an impact on the integrity and function of bacterial cell walls.

5. Mechanisms of MNP Decreasing the F/B Ratio

The mechanisms by which nanoplastic decreases the F/B ratio are addressed in the following sections: 6.1 In Vitro Evidence in Firmicutes vs. Bacteroidetes and 6.2 In Vivo Studies and Observations.

5.1. In Vitro Evidence in Firmicutes vs. Bacteroidetes

5.1.1. Bacteroidetes (Gram-Negative)

While direct studies on Bacteroidetes species are limited, Gram-negative models provide insight into how these plastics affect their cell envelopes. Gram-negatives have an outer membrane (with LPS) and a thinner peptidoglycan layer, which can make them susceptible to nano-sized particles breaching the outer barrier. In E. coli (Proteobacteria, but also Gram-negative), co-exposure to 50 nm PS nanoplastics was shown to penetrate the outer membrane and lodge in the periplasm, causing membrane depolarization and growth inhibition. Ning et al. observed that small PS particles adhered to E. coli (Pseudomonadota/ Proteobacteria, Gram negative) surfaces and induced significant ROS; notably, 30 nm particles caused physical membrane damage visible by electron microscopy, whereas larger 200 nm particles were less invasive [

42]. This suggests Bacteroidetes of similar size might likewise experience membrane penetration by nanoplastics. Gram-negative gut bacteria also show functional signs of cell envelope stress: one soil study reported carboxylated nanoplastics decreased Gram-negative bacterial enzyme activities and altered their surface hydrophobicity, consistent with membrane perturbation [

43]. Bacteroidetes in the gut often produce mucus-degrading enzymes and form biofilms in the colon. Microplastics may interfere with these interactions. For example, Alistipes (a Bacteroidetes genus) was significantly decreased in relative abundance when mice were exposed to 150 µm polystyrene microplastics for one week. This drop suggests PS either selectively harmed Alistipes or created conditions (e.g. oxidative environment) unfavorable to it. On the other hand, in the same study, other Bacteroidetes were less affected or even increased with different plastic types [

44]. These results imply species-specific effects: some Bacteroidetes might be relatively hardy biofilm-formers that attach to plastics, while others are sensitive to the membrane stress or dysbiosis caused by plastics. Importantly, Gram-negative cell walls contain porins and lipid A – potential binding sites for plastics. There is evidence that nanoplastics can bind LPS and even cross the outer membrane via transient pores [

45,

46]. No significant cell wall thickening or repair response has been documented in Bacteroidetes upon plastic contact (in contrast to some Gram-positives that increase peptidoglycan cross-linking as a stress response, see below), suggesting that once their outer membrane is disrupted, Gram-negatives may be less able to physically reinforce their wall. Instead, their strategy seems to rely on EPS secretion or detoxifying enzymes.

5.1.2. Firmicutes (Gram-Positive)

Firmicutes have a thick peptidoglycan cell wall lacking an outer membrane, which can influence how plastics interact. Several studies have examined Firmicutes representatives: for example, Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus spp. are common models. In the S. aureus/K. pneumoniae nanoparticle study mentioned earlier [

44], the Gram-positive S. aureus showed a bit more resistance to nanoparticle attachment at low concentrations.

5.1.3. Significant Zeta Potential Shifts (Signifying Particle Binding) Only Occurred at Concentrations of PS ≥20 µg/mL for S. Aureus, Whereas Klebsiella (Gram-Negative) Showed Surface Charge Changes Even at 2–20 µg/mL [33]

The authors attributed this to the thicker peptidoglycan layer of Gram-positive cells, which may initially limit nanoparticle access. Nonetheless, at higher doses (100 µg/mL), S. aureus did bind many PS particles, resulting in an even greater increase in net negative surface charge (due to blocking of positively-charged sites). AFM images showed PS beads decorating the S. aureus surface, but again no obvious cell wall breakage. This suggests that Gram-positive cell walls can accommodate a fair amount of adsorbed plastic without immediate rupture. However, subtle damage can occur with positively charged nanoparticles creating ion-selective pores in the membrane could dissipate the proton motive force of Gram-positives. Such pore formation in Firmicutes would increase cell wall permeability (to ions and small molecules) and could be detected by uptake of viability dyes (e.g., propidium iodide) even if the cell isn’t lysed. A recent in vivo study found that Lachnospiraceae, a family in Firmicutes readily take up 100 nm PS particles in the gut [

14]. Confocal imaging confirmed nanoplastic accumulation inside fecal bacteria shortly after exposure. Although specific cell wall damage in those bacteria wasn’t microscopically detailed, the internalization implies that the plastic either traversed or seriously compromised the cell envelope. Positively charged (cationic) nanoplastics are known to bind avidly to negatively charged gram-positive bacterial surfaces (e.g. B. subtilis) and often cause significant membrane damage [

46,

47], whereas neutral or negatively charged particles typically show far less membrane perturbation. For example, neutral/negative 100 nm PS particles adhered to the cell membranes of S. aureus, did not compromise the membrane integrity, but did inhibit bacterial growth at 50 mg/mL [

33]. Kim et al. reported that 100 mg/L 60 nm negatively charged PS attached to cell surfaces of Gram-positive gut-related genera like Bacillus and Lactobacillus, entered cells and caused growth inhibition [

37]. Zhao et al. showed that another gram positive bacteria (Lactobacillus) took up PP, PE, PVC [

48]. Neutral or negatively charged nanoplastic also generated ROS and caused oxidative damage on bacillus [

35,

37], altered membrane properties and enzyme activities [

49] and even modulate bacterial growth and gene expression, thus reinforce that even without a positive charge, nanoplastics can impact Gram-positive microbes in the gut environment. Some Firmicutes like Ruminococcaceae interacted with NPs to a lesser extent, and some (e.g. certain butyrate producers) might be inhibited if their cell envelope is disturbed. Overall, in vitro experiments illustrate that Gram-positive gut bacteria can adsorb or even internalize micro/nanoplastics while surviving, often by mounting stress responses (antioxidant production, biofilm formation). Yet prolonged exposure can skew the Firmicute community, likely by impairing more sensitive members’ membrane functions or by favoring species that capitalize on plastic surfaces (the so-called “plastisphere” colonizers).

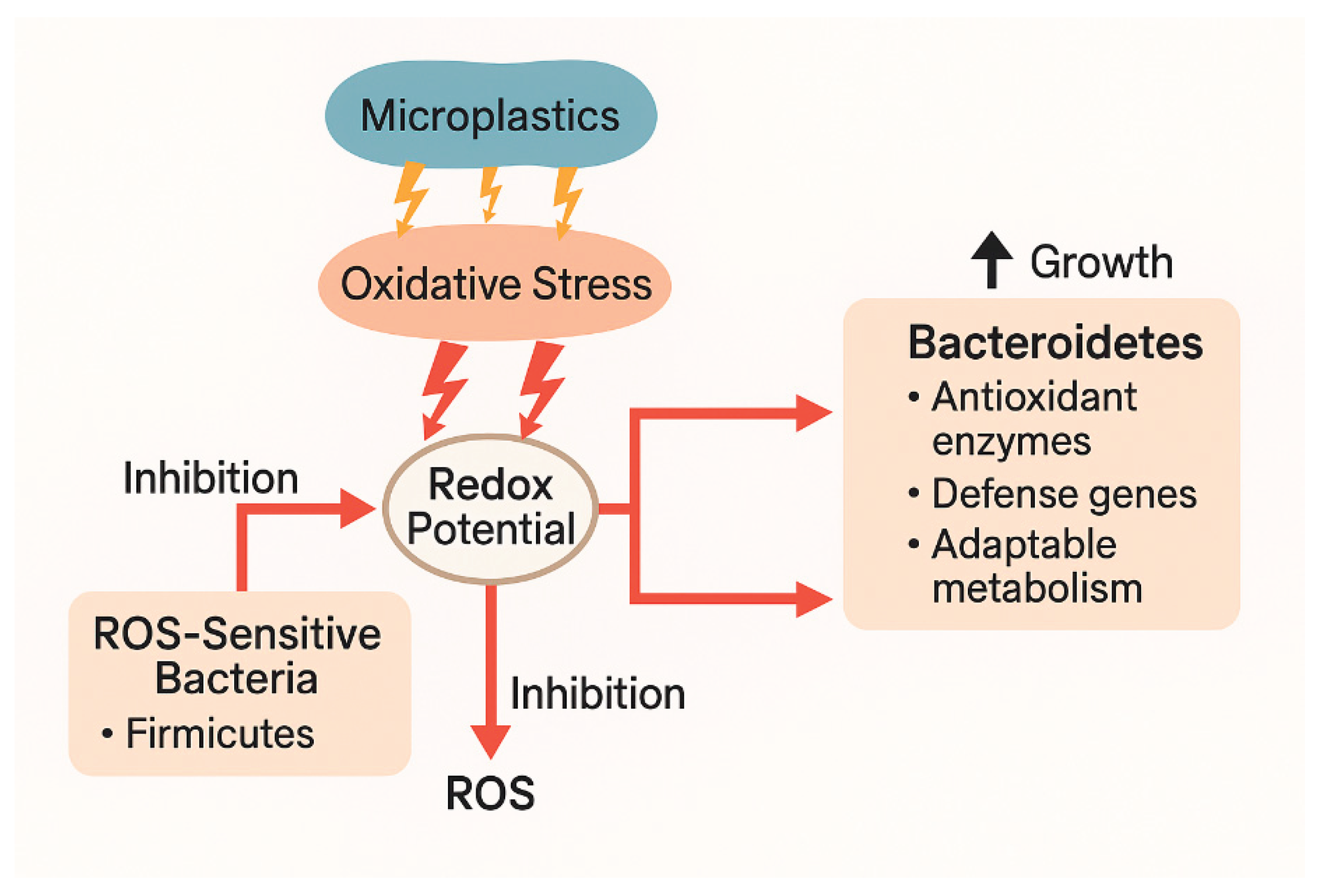

5.1.4. Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress from microplastics can alter the intestinal redox environment, creating conditions that favor the growth of certain gut bacterial groups like Bacteroidetes (which includes Bacteroides spp.). Nanoplastics can elevate ROS and inflammation in the gut, disrupting redox balance and damaging the epithelial barrier. This creates an oxidizing environment that selectively disadvantages ROS-sensitive strict anaerobes (e.g., many Firmicutes) while enabling more ROS-tolerant bacteria like Bacteroides to thrive. The observed phylum-level shifts consistently mirror this mechanistic pathway.

5.2. In Vivo Studies and Observations

5.2.1. Some Firmicutes Appear to be Adept at Interacting with or Even Internalizing Nanoplastics

Lachnospiraceae, a Gram-positive family abundant in the gut, was recently identified as a primary nanoplastic-consuming bacterium. Hsu et al. showed via flow cytometry and 16S sequencing that Lachnospiraceae cells were the dominant carriers of 100 nm PS particles in mouse intestines – 42% of NP-positive bacteria belonged to Lachnospiraceae [

14]. These bacteria apparently took up or strongly bound the nanoparticles. Remarkably, having particles inside did not immediately inhibit their growth in vitro. However, there were consequences: Lachnospiraceae that internalized PS went on to release extracellular vesicles that could disrupt host mucus production. This indicates that although the Firmicute cell wall can accommodate nanoplastics (perhaps by engulfing them into the thick wall matrix or cytoplasm), it alters their physiology. It’s possible that NP uptake occurs via a “tunneling” mechanism or endocytosis-like process (some Gram-positives can take up nanoparticles into vesicles). In any case, the ability of Lachnospiraceae to harbor plastics suggests a tolerance mechanism – potentially related to their robust cell wall. Chronic exposure to 100 nm nanoplastics in vivo has been associated with declines in certain Firmicutes. In a 12-week mouse study, Lachnospiraceae (Firmicutes) was significantly enriched with carboxylated PS, indicating active uptake or surface binding in nanoplastic-exposed mice [

14]. This implies that some Firmicutes (especially mucosa-associated ones like lactobacilli) may be sensitive to the inflammatory or membrane-targeting effects of nanoplastics over time. Perhaps their cell walls become compromised by continuous oxidative stress, or they are outcompeted by hardier microbes.

5.2.2. Animal Models Have Provided Evidence That Ingested Micro/Nanoplastics Cause Both Gut Microbial Shifts and Direct Structural Impacts on Bacteria

Short-term exposure studies in mice showed that even without overt toxicity to the host, plastics can disturb the gut microbiota. In studies where 100 nm carboxylated polystyrene nanobeads (PS-NPs) were administered via oral gavage at for 28 days, following induction of chronic colitis in mice, significantly exacerbated intestinal inflammation [

14]. Elevated oxidative stress confirmed heightened ROS damage after 28 days of oral gavage of 100 nm PS at 1, 5, or 25 mg/kg/day; no microbiome sequencing was included in this study [

50]. More direct evidence of bacterial cell wall interaction in vivo comes from Hsu et al. [

14], who administered fluorescent 100 nm polystyrene to mice at 1 mg/kg/day and tracked bacteria-particle interactions. At this low chronic dose of PS, there was no evidence that the F/B decreased. Lachnospiraceae with internalized NP were implicated in downstream effects – these NP-loaded bacteria released membranous vesicles that interfered with the host’s mucus gene expression. This implied the bacteria’s own cell envelope was altered enough by NP uptake to change how they communicated with the host (via vesicles). The same study found that chronic nanoplastic exposure increased Ruminococcaceae (Firmicutes) in the gut, and the authors suggested this is partly due to NP-induced vesicles promoting those bacteria’s growth. From a cell wall perspective, the in vivo data showed that some gut bacteria physically incorporate nanoplastics into their cells (or tightly attached to their walls) and survive, whereas others are less competitive or suffer declines, likely because their cell walls cannot cope with the combined physical and chemical stress.

5.2.3. Human-Relevant Studies Are Mostly Ex Vivo, But a Few Clues Emerge

A simulated human gastrointestinal digestion of PET microplastics found that by the colon phase, gut microbes had attached to and pitted the surface of the plastic particles, suggesting bacterial enzymatic or mechanical action on the polymer [

41]. This hints that certain gut bacteria (possibly some Firmicutes known to degrade complex substrates) can even begin to biodegrade plastics, which would entail close contact and likely secretion of cell-wall-associated enzymes. However, the same simulation warned that microplastics can alter the microbiome’s function, potentially by affecting those cell-wall enzymes and transporters [

41]. In patients, it has been reported that individuals with inflammatory bowel disease have higher levels of microplastics in their gut, which correlates with differences in gut microbiota composition (though causality is unclear) [

9]. If microplastics exacerbate gut inflammation, that can indirectly harm bacterial cell walls by exposing bacteria to reactive radicals and antimicrobial peptides.

5.2.4. In Summary, In Vivo Evidence Confirms That Micro/Nanoplastics Can Cause Measurable Changes in Intestinal Bacteria Consistent with Cell Wall Stress or Damage

We see shifts favoring bacteria that either withstand or even utilize the plastics (e.g. some Firmicutes forming biofilms on them), while more sensitive groups decline. We also see molecular evidence like increased membrane permeability (uptake of particles by bacteria) and functional evidence such as altered membrane-derived vesicle activity. Combined with imaging and molecular assays from in vitro studies (e.g. SEM of bacteria on plastic, membrane potential assays, ROS measurements), the consensus is that plastic particles can injure bacterial cell walls through mechanical contact and ROS generation, leading to increased permeability and sometimes cell death, although many gut bacteria invoke protective strategies (antioxidants, biofilms) to cope. These interactions differ between phyla: Bacteroidetes (Gram–) may be more prone to acute membrane penetration and lysis by small NPs, whereas Firmicutes (Gram+) often resist immediate lysis but can internalize particles and experience sub-lethal envelope stress. Both outcomes – physical membrane disruption and oxidative damage – can alter the gut microbial balance and are active areas of research for understanding environmental nanoplastic impacts on health [

35].

6. Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress alters host and microbial redox balance. When microplastics enter the gut, they can generate ROS directly on their surfaces or through leached additives (e.g., phthalates, heavy metals). They can also trigger immune responses and epithelial stress in the host, leading to further ROS production. And they can impair host antioxidant defenses (e.g., catalase, glutathione systems), leading to a more oxidized intestinal environment. This elevated oxidative stress leads to a shift in the gut’s redox potential, often from highly reduced (anaerobic) conditions toward more oxidizing conditions. This can selectively inhibit anaerobes sensitive to oxidative stress—like many Firmicutes. Meanwhile, some facultative anaerobes and aerotolerant strict anaerobes, including many Bacteroides, are more resilient to redox stress [

2,

44,

51].

6.1. Bacteroides' Adaptation to Oxidative Environments

Bacteroides spp. possess several mechanisms that allow survival in moderately oxidizing conditions. They produce enzymes like SOD, catalase, and peroxidases, which help detoxify ROS. Some strains can upregulate antioxidant defense genes under oxidative stress, maintaining metabolic function. They can shift metabolic strategies (e.g., using alternative electron acceptors) that allow persistence when redox conditions fluctuate. Thus, in a gut under oxidative stress (e.g., due to nanoplastics), Bacteroides may face less competition from ROS-sensitive taxa (e.g., Clostridia/Firmicutes), outgrowing other microbes, increasing their relative abundance. [

52,

53],

6.2. Microplastic-Linked Microbiota Shifts

Experimental studies in animals (e.g., mice, fish, rabbits) exposed to microplastics consistently show shifts in the microbiome. Papp et al. reported that at higher PVC levels, an altered the gut microbiota composition

, with increased Bacteroidetes and decreased Firmicutes [

54]. Galecka and coworkers reported a decrease in Firmicutes (often strict anaerobes sensitive to oxidative conditions), and a relative increase in Bacteroidetes, including Bacteroides spp [

55]. Bacteroides species—especially B. thetaiotaomicron—can adapt metabolically to reduce ROS internally. Thus, under oxidative pressure, Bacteroidetes are more likely to dominate due to enhanced survival and flexibility [

56]. This pattern may support the idea that oxidative pressure favors Bacteroidetes by weakening redox-sensitive competitors and selecting for metabolically flexible, ROS-tolerant bacteria

Figure 2.

7. Primary Literature

Of the primary literature from 2020-2025 not cited in reviews and focused on MNPs effects on the gut microbiome and gut health, most studies with nanoplastic strongly linked the gut effects with clear microbiome disruption [

40,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61] whereas a few studies with microplastic or a mixture of MNP suggested that gut/immune changes can occur without significant microbiome shifts [

62,

63,

64]. Huang et al. found that PS induced microbiome shifts (↑ endotoxin producers) caused systemic inflammation (↑LPS), suggesting microbiota-mediated barrier dysfunction and systemic effects [

61]. Su and coworkers reported that in mice, PS reduced tight junction expression correlated directly with microbial dysbiosis (↑Prevotellaceae), supporting dysbiosis-driven gut barrier impairment [

60]. Huang and coworkers reported that severe gut lesions (edema, villus erosion) caused by PS in zebrafish were tightly correlated with significant microbiome shifts (additive effects with diet), suggesting that the microbiota disruption significantly exacerbates epithelial damage [

40]. Sun and coworkers reported a mucin reduction and gut inflammation coincided with clear microbiome alterations, implied microbiota disruption contributed to observed gut dysfunction after chronic dosing of PE in mice (size and length of study not disclosed) [

59,

65]. The evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that large microplastic causes a different kind of dysbiosis; one where the F/B ratio is increased. And when the exposure is a mix of micro- and nanoplastic, the results are also mixed – often resulting in no significant increase or decrease in F/B ratio. Djouina et al. observed only modest microbiome shifts alongside mild epithelial marker changes after 100 µg/g 36 µm PE fed to mice in the diet for 6 weeks [

66]. The gut damage appeared at least partially driven by the large particle size and MP chemical properties independent of microbiome, indicating a mixed relationship. Harusato et al. fed irregular fragments of micron-sized PET (1-5 µm) to mice in the diet for eight weeks at 100 µg/day/mouse. They demonstrated significant gut immune gene expression changes without major microbiome dysbiosis or inflammation. Only minor microbiome shifts occurred, yet notable immune modulation was seen—suggesting MP effects on gut immunity independent of significant dysbiosis [

62]. However, this may be because the exposure to MP was so low (i.e. below the threshold that causes major intestinal and microbiome effects) or that at this low level of exposure, a longer treatment period is necessary to show the relationship. Li and coworkers noted microbiome dysbiosis alongside inflammation after feeding 2 µm and 80 nm PE to mice for up to 5 weeks at 600 mg/day. The decreased F/B ratio was accompanied with tight junction disruption and an increase in tissue ROS levels. [

67]. Others have reported that feeding chickens <100 µm PS at 200 mg/kg/day for 6 weeks affected gut growth performance with significant dysbiosis (decrease F/B), inflammation and oxidative stress [

64].

8. Experimental Gaps in the Research

So far, no study has reported both carefully assessed gut microbiome changes using sequencing or community-level metrics and reported typical epithelial damage (e.g., barrier disruption, ROS increase, apoptosis) while finding no microbiome effects following exposure to nanoplastic. The following proposed studies are expected to further clarify and define the impact of MNPs on intestinal health.

8.1. Controlled Animal Models with Comprehensive Microbiome Analysis

The intent of these studies would be to clearly determine whether intestinal epithelial effects (e.g., barrier dysfunction, ROS, inflammation) occur without microbiome dysbiosis. Rodent models (mice/rats), chronic low-dose oral exposure to MNPs (multiple plastic types, sizes) would be paired with microbiome assessments (16S rRNA, metagenomics, functional metabolomics), and rigorous epithelial assays (histology, barrier integrity, ROS). If found, then by gradually increasing exposure levels, the point at which the dysbiosis and ill gut health effects could be delineated. And by fecal transplantation of animals with dysbiosis into gnotobiotic or germ-free animals, might determine if the dysbiosis causes the ill gut health effects.

8.2. Longitudinal, Multi-Omics Human Cohort Studies

These studies could assess realistic exposure scenarios and their clinical significance, directly correlating gut barrier markers and microbial communities over time. Consisting of human cohort studies assessing dietary exposure to MNPs, collecting stool, blood samples for microbiome, inflammatory markers, ROS biomarkers, and gut permeability assays over months-to-years, with dietary tracking and exposure modeling, would speak to the human relevance and long-term data currently lacking, improving risk assessment.

8.3. Mechanistic Cellular and Organoid Models

These studies could directly clarify cellular mechanisms independent of microbiome involvement. They would consist of human intestinal organoids or primary epithelial cultures exposed to defined MNPs, with cellular endpoints (ROS, apoptosis, tight junction expression, immune signaling), comparing gnotobiotic vs. microbe co-cultured conditions. And would help to clarify direct epithelial/MNP interaction, free of microbial confounding.

8.4. Studies Evaluating Immune–Microbial Cross-talk

These studies could determine how minor microbiome changes might modulate or exacerbate epithelial or immune changes due to MNP exposure. Using gnotobiotic mouse models, colonized with defined microbiomes, exposed to various MNP types and sizes, with extensive immune cell profiling and cytokine analyses, could clarify subtle microbial-immune interactions possibly missed by standard microbiome analyses.

8.5. Environmental Mixtures and Real-world Exposures

Since most studies to date use commercial sources of MNP , these studies would examine realistic environmental scenarios involving mixtures of plastics, contaminants, dietary factors, and their combined gut/microbiome effects. These studies (rodents, zebrafish) would examine types and sizes of MNP and include extensive gut and microbiome assessments.

8.6. Bioinformatics and Predictive Modeling

The objective of these studies would be to develop robust predictive models linking MNP exposure, microbiome shifts, and gut epithelial outcomes. By Integrating multi-omics datasets from existing and new studies, together with machine learning for identifying key taxa, metabolites, or biomarkers predictive of barrier dysfunction and ROS, these studies could inform targeted future experimental design, enhances regulatory relevance.

9. Conclusions

The impact of the gut microbiome dysbiosis on intestinal health and then indirectly on numerous maladies has been well established. The cause of the decrease in the F/B ratio is not always known. However, the potential roles of MNP on this decrease has been delineated in this review. The differential physical interaction of nanoplastic with the cell wall and their effects on Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes suggests how the F/B ratio decreases. Future studies will have to confirm this hypothesis and perhaps provide a means to lessen the detrimental impact of MNP on intestinal health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.S. and R.H. methodology, S.S.; validation, S.S.; formal analysis, S.S. and R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and R.H.; visualization, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 4.5 and ChatGPT 4.o for the purposes of identifying potential studies for inclusion in this review. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EPS |

exopolysaccharide |

| F/B |

Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes |

| GI |

gastrointestinal |

| LPS |

lipopolysaccharide |

| MNP |

Micro- and nano-plastic |

| NP |

nanoparticle |

| PET |

polyethylene terephthalate |

| PP |

polypropylene |

| PS |

polystyrene |

| PVC |

Polyvinyl chloride |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCFA |

short-chain fatty acid |

| SOD |

superoxide dismutase |

References

- Kannan, K. and K. Vimalkumar. "A review of human exposure to microplastics and insights into microplastics as obesogens." Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 12 (2021): 724989. [CrossRef]

- Bora, S. S., R. Gogoi, M. R. Sharma, Anshu, M. P. Borah, P. Deka, J. Bora, R. S. Naorem, J. Das and A. B. Teli. "Microplastics and human health: Unveiling the gut microbiome disruption and chronic disease risks." Front Cell Infect Microbiol 14 (2024): 1492759. [CrossRef]

- Covello, C., F. Di Vincenzo, G. Cammarota and M. Pizzoferrato. "Micro(nano)plastics and their potential impact on human gut health: A narrative review." Curr Issues Mol Biol 46 (2024): 2658-77. [CrossRef]

- Eichinger, J., M. Tretola, J. Seifert and D. Brugger. "Interactions between microplastics and the gastrointestinal microbiome.". Italian Journal of Animal Science 2024, 23, 1044–56. [CrossRef]

- Hirt, N. and M. Body-Malapel. "Immunotoxicity and intestinal effects of nano- and microplastics: A review of the literature." Part Fibre Toxicol 17 (2020): 57. [CrossRef]

- de Souza-Silva, T. G., I. A. Oliveira, G. G. da Silva, F. C. V. Giusti, R. D. Novaes and H. A. de Almeida Paula. "Impact of microplastics on the intestinal microbiota: A systematic review of preclinical evidence." Life Sciences 294 (2022): 120366. [CrossRef]

- Procopio, A. C., A. Soggiu, A. Urbani and P. Roncada. "Interactions between microplastics and microbiota in a one health perspective." One Health (2025): 101002. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., K. Deng, P. Zhang, Q. Chen, J. T. Magnuson, W. Qiu and Y. Zhou. "Microplastic-mediated new mechanism of liver damage: From the perspective of the gut-liver axis." Sci Total Environ 919 (2024): 170962. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z., Y. Liu, T. Zhang, F. Zhang, H. Ren and Y. Zhang. "Analysis of microplastics in human feces reveals a correlation between fecal microplastics and inflammatory bowel disease status." Environ Sci Technol 56 (2022): 414-21. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., S. Liu and H. Xu. "Effects of microplastic and engineered nanomaterials on inflammatory bowel disease: A review." Chemosphere 326 (2023): 138486. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M., A. Vianello, M. Picker, L. Simon-Sánchez, R. Chen, M. M. Estevinho, K. Weinstein, J. Lykkemark, T. Jess, I. Peter, et al. "Micro- and nano-plastics, intestinal inflammation, and inflammatory bowel disease: A review of the literature." Sci Total Environ 953 (2024): 176228. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A., M. Dovizio, C. Milillo, E. Aruffo, M. Pesce, M. Gatta, P. Chiacchiaretta, P. Di Carlo and P. Ballerini. "Orally ingested micro- and nano-plastics: A hidden driver of inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer." Cancers (Basel) 16 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hills, R. D., Jr. A. Pontefract, H. R. Mishcon, C. A. Black, S. C. Sutton and C. R. Theberge. "Gut microbiome: Profound implications for diet and disease." Nutrients 11 (2019): 1613. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.-H., Y. -Z. Chen, Y.-T. Chiang, Y.-T. Chang, Y.-W. Wang, K.-T. Hsu, Y.-Y. Hsu, P.-T. Wu and B.-H. Lee. "Polystyrene nanoplastics disrupt the intestinal microenvironment by altering bacteria-host interactions through extracellular vesicle-delivered micrornas." Nature Communications 16 (2025): 5026. 10.1038/s41467-025-59884-y. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A., T. Habumugisha, F. Huang, Z. Zhang, C. Kiki, M. A. Al, C. Yan, U. Shaheen and X. Zhang. "Impacts of polystyrene nanoplastics on zebrafish gut microbiota and mechanistic insights." Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 299 (2025): 118332-32. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Arroyo, C., A. Tamargo, N. Molinero and M. V. Moreno-Arribas. "The gut microbiota, a key to understanding the health implications of micro(nano)plastics and their biodegradation." Microb Biotechnol 16 (2023): 34-53. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., M. Xu, L. Wang, W. Gu, X. Li, Z. Han, X. Fu, X. Wang, X. Li and Z. Su. "Continuous oral exposure to micro- and nanoplastics induced gut microbiota dysbiosis, intestinal barrier and immune dysfunction in adult mice." Environment International 182 (2023): 108353. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z., C. Wang, J. Zhou, M. Shen, X. Wang, Z. Fu and Y. Jin. "Effects of polystyrene microplastics on the composition of the microbiome and metabolism in larval zebrafish." Chemosphere 217 (2019): 646-58. [CrossRef]

- Souza-Silva, T. G. d., I. A. Oliveira, G. G. d. Silva, F. C. V. Giusti, R. D. Novaes and H. A. d. A. Paula. "Impact of microplastics on the intestinal microbiota: A systematic review of preclinical evidence." Life Sciences 294 (2022): 120366. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., L. Chen, N. Zhou, Y. Chen, Z. Ling and P. Xiang. "Microplastics in the human body: A comprehensive review of exposure, distribution, migration mechanisms, and toxicity." Science of The Total Environment 946 (2024): 174215. [CrossRef]

- Li, P. and J. Liu. "Micro(nano)plastics in the human body: Sources, occurrences, fates, and health risks." Environ Sci Technol 58 (2024): 3065-78. [CrossRef]

- Smith. "Immunotoxicity & intestinal effects of nano-/microplastics." Particle and fibre toxicology (2020):.

- Chen. "Impact of microplastics on the intestinal microbiota." ScienceDirect Review (2022):.

- Li. "Interactions between microplastics and the gastrointestinal microbiome." Taylor & Francis Review (2024):.

- Zhao. "Micro(nano)plastics and their potential impact on human gut health." MDPI Review (2024):.

- Wang. "Microplastics & human health: Unveiling the gut microbiome." Frontiers (2024):.

- Tanaka. "Microplastics and microbiota: Unraveling the hidden environmental challenge." World J Gastroenterol (2024):.

- Liu. "Recent progress in intestinal toxicity of microplastics and nanoplastics." MDPI (2024):.

- Ahmed. "Comprehensive human-focused review on mps & microbiome." Science of The Total Environment (2024):.

- Patel. "Systematic review on toxicokinetics and gut microbiota." Critical reviews in food science and nutrition (2025):.

- Fleury, J. B. and V. A. Baulin. "Microplastics destabilize lipid membranes by mechanical stretching." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118 (2021): e2104610118. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., Y. Yang, L. Bai and J. Cui. "Microplastics: An often-overlooked issue in the transition from chronic inflammation to cancer." J Transl Med 22 (2024): 959. [CrossRef]

- Zajac, M., J. Kotynska, G. Zambrowski, J. Breczko, P. Deptula, M. Ciesluk, M. Zambrzycka, I. Swiecicka, R. Bucki and M. Naumowicz. "Exposure to polystyrene nanoparticles leads to changes in the zeta potential of bacterial cells." Sci Rep 13 (2023): 9552. [CrossRef]

- Perini, D. A., E. Parra-Ortiz, I. Varó, M. Queralt-Martín, M. Malmsten and A. Alcaraz. "Surface-functionalized polystyrene nanoparticles alter the transmembrane potential via ion-selective pores maintaining global bilayer integrity." Langmuir 38 (2022): 14837-49. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., X. Li, J. Li, W. Dai and Y. Luan. "Bacterial interactions with nanoplastics and the environmental effects they cause." Fermentation 9 (2023): 939. [CrossRef]

- Manke, A., L. Wang and Y. Rojanasakul. "Mechanisms of nanoparticle-induced oxidative stress and toxicity." Biomed Res Int 2013 (2013): 942916. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y., Y. J. Kim, S. W. Lee and E. H. Lee. "Interactions between bacteria and nano (micro)-sized polystyrene particles by bacterial responses and microscopy." Chemosphere 306 (2022): 135584. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y., S. Woo, S. W. Lee, E. M. Jung and E. H. Lee. "Dose-dependent responses of escherichia coli and acinetobacter sp. To micron-sized polystyrene microplastics." J Microbiol Biotechnol 35 (2025): e2410023. [CrossRef]

- Athulya, P. A., N. Chandrasekaran and J. Thomas. "Polystyrene microplastics interaction and influence on the growth kinetics and metabolism of tilapia gut probiotic bacillus tropicus acs1." Environ Sci Process Impacts 26 (2024): 221-32. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., L. Wang, J. Zhang, Y. Liu, X. Li and Y. Zhao. "Combined effects of polystyrene microplastics and high-fat diet on gut health and microbiota in zebrafish." Journal of Fish Biology 104 (2024): 93-105. [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, A., N. Molinero, J. J. Reinosa, V. Alcolea-Rodriguez, R. Portela, M. A. Banares, J. F. Fernandez and M. V. Moreno-Arribas. "Pet microplastics affect human gut microbiota communities during simulated gastrointestinal digestion, first evidence of plausible polymer biodegradation during human digestion." Sci Rep 12 (2022): 528. [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y., Q. Li, M. Wang, X. Yan and D. Wang. "Surface charges of polystyrene nanoplastics determine the adhesion and toxicity to bacteria." Journal of Hazardous Materials 429 (2022): 128276. [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y., S. Huang, H. Zhang, Y. Tong, D. Wen, X. Xia, H. Wang, Y. Luo and D. Barcelo. "Response of soil enzyme activities and bacterial communities to the accumulation of microplastics in an acid cropped soil." Sci Total Environ 707 (2020): 135634. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L., T. Chen, J. Liu, Y. Hou, Q. Tan, X. Zhang, Z. Li, T. H. Farooq, W. Yan and Y. Li. "Intestinal flora variation reflects the short-term damage of microplastic to the intestinal tract in mice." Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 246 (2022): 114194. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, K. H., I. L. Gunsolus, T. R. Kuech, J. M. Troiano, E. S. Melby, S. E. Lohse, D. Hu, W. B. Chrisler, C. J. Murphy, G. Orr, et al. "Lipopolysaccharide density and structure govern the extent and distance of nanoparticle interaction with actual and model bacterial outer membranes." Environ Sci Technol 49 (2015): 10642-50. [CrossRef]

- Dai, S., R. Ye, J. Huang, B. Wang, Z. Xie, X. Ou, N. Yu, C. Huang, Y. Hua, R. Zhou, et al. "Distinct lipid membrane interaction and uptake of differentially charged nanoplastics in bacteria." J Nanobiotechnology 20 (2022): 191. [CrossRef]

- Perez, F., N. M. O. Andoy, U. T. T. Hua, K. Yoshioka and R. M. A. Sullan. "Adaptive responses of bacillus subtilis underlie differential nanoplastic toxicity with implications for root colonization." Environmental Science: Nano 12 (2025): 1477-86. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Q. Dou, S. Chen, Y. Wang, Q. Yang, W. Chen, H. Zhang, Y. Du and M. Xie. "Adsorption abilities and mechanisms of lactobacillus on various nanoplastics." Chemosphere 320 (2023): 138038. [CrossRef]

- Yi, X., W. Li, Y. Liu, K. Yang, M. Wu and H. Zhou. "Effect of polystyrene microplastics of different sizes to escherichia coli and bacillus cereus." Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 107 (2021): 626-32. 10.1007/s00128-021-03215-6. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Y. Wan, L. Song, L. Wang, H. Wang, Y. Li and D. Huang. "Polystyrene nanobeads exacerbate chronic colitis in mice involving in oxidative stress and hepatic lipid metabolism." Part Fibre Toxicol 20 (2023): 49. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., X. Chen, D. Lin, L. Wang, W. Xu, Y. Huang, H. Xia, H. Jin, J. Liu and Z. Cai. "Oral exposure to polystyrene microplastics induces gut microbiota dysbiosis and intestinal inflammation in mice." Journal of Hazardous Materials 430 (2022): 128400. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. and et al. "Differential responses of gut microbiota and intestinal barrier to polystyrene microplastics in male and female mice. Science of The Total Environment. [CrossRef]

- Semenova, Y. A. and et al. "Chronic low-dose polystyrene microplastic exposure alters intestinal epithelial homeostasis without significant microbiota disruption. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology. [CrossRef]

- Papp, P. P., O. I. Hoffmann, B. Libisch, T. Kereszteny, A. Gerocs, K. Posta, L. Hiripi, A. Hegyi, E. Gocza, Z. Szoke, et al. "Effects of polyvinyl chloride (pvc) microplastic particles on gut microbiota composition and health status in rabbit livestock." Int J Mol Sci 25 (2024): 12646. [CrossRef]

- Galecka, I., A. Rychlik and J. Calka. "Influence of selected dosages of plastic microparticles on the porcine fecal microbiome." Sci Rep 15 (2025): 1269. [CrossRef]

- Xie, S., J. Ma and Z. Lu. "Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron enhances oxidative stress tolerance through rhamnose-dependent mechanisms." Front Microbiol 15 (2024): 1505218. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. and et al. "Gut-toxic effects and microbiome alterations induced by virgin vs. Uv-weathered polypropylene microplastics in adult zebrafish. Journal of Hazardous Materials. [CrossRef]

- Santonen, T., S. P. Porras, B. Bocca, R. Bousoumah, R. C. Duca, K. S. Galea, L. Godderis, T. Goen, E. Hardy, I. Iavicoli, et al. "Hbm4eu chromates study - overall results and recommendations for the biomonitoring of occupational exposure to hexavalent chromium." Environ Res 204 (2022): 111984. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., B. Chen, Q. Li, N. Liu, B. Xia and L. Zhu. "Toxic effects caused by polystyrene microplastics exposure in drinking water on intestinal barrier and gut microbiota in mice." Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 209 (2021): 111829. [CrossRef]

- Su, R., Y. Li, H. Wang, T. Zhao and X. Zhang. "Effects of polystyrene microplastics on intestinal structure, barrier function, and gut microbiota in mice: A sex-based difference." PLoS ONE 19 (2024): e0289184. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., C. Wang, M. Zhang, Y. Zhou, J. Zhang and H. Chen. "Polystyrene microplastics induce gut microbiota dysbiosis and hepatic lipid metabolism disorder in mice." Science of The Total Environment 755 (2022): 142570. [CrossRef]

- Harusato, A., M. Zhang, S. Nishimoto and et al. "Chronic exposure to environmentally relevant microplastics modifies immune homeostasis without overt inflammation in the murine colon." iScience 26 (2023): 106115. [CrossRef]

- Li, B., Y. Zhong, Y. Huang, X. Lin, J. Liu, L. Lin, M. Hu, J. Jiang, M. Dai and B. Wang. "Polystyrene microplastics induce gut microbiota dysbiosis and hepatic lipid metabolism disorder in mice." Chemosphere 255 (2020): 126060. [CrossRef]

- Zou, W., S. Lu, J. Wang, Y. Xu, M. A. Shahid, M. U. Saleem, K. Mehmood and K. Li. "Environmental microplastic exposure changes gut microbiota in chickens." Animals 13 (2023): 2503. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Y. Zhuang, Y. Wang, Z. Zhang, L. An and Q. Xu. "Polyethylene terephthalate microplastics affect gut microbiota distribution and intestinal damage in mice." Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 294 (2025): 118119. [CrossRef]

- Djouina, M., A. Khadraoui, N. Benamor, D. Ghemati and et al. "Dietary exposure to environmentally relevant polyethylene microplastics alters gut morphology and microbial composition in mice." Environmental Research 204 (2022): 111984. [CrossRef]

- Li, B., Y. Zhong, Y. Huang, X. Lin, J. Liu, L. Lin, M. Hu, J. Jiang, M. Dai and B. Wang. "Underestimated health risks: Polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics jointly induce intestinal barrier dysfunction by ros-mediated epithelial cell apoptosis." Particle and fibre toxicology 18 (2021): 20. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).