Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background Information

2.1. Graph Theory Notation

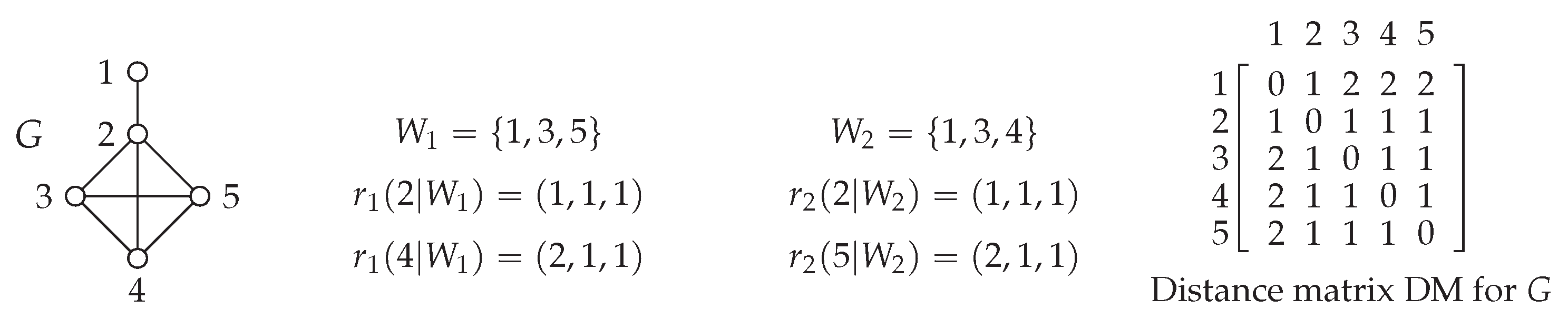

2.2. Distance Matrix and Common Neighbor Matrix

2.3. Average Graphs

2.4. Durfee Square

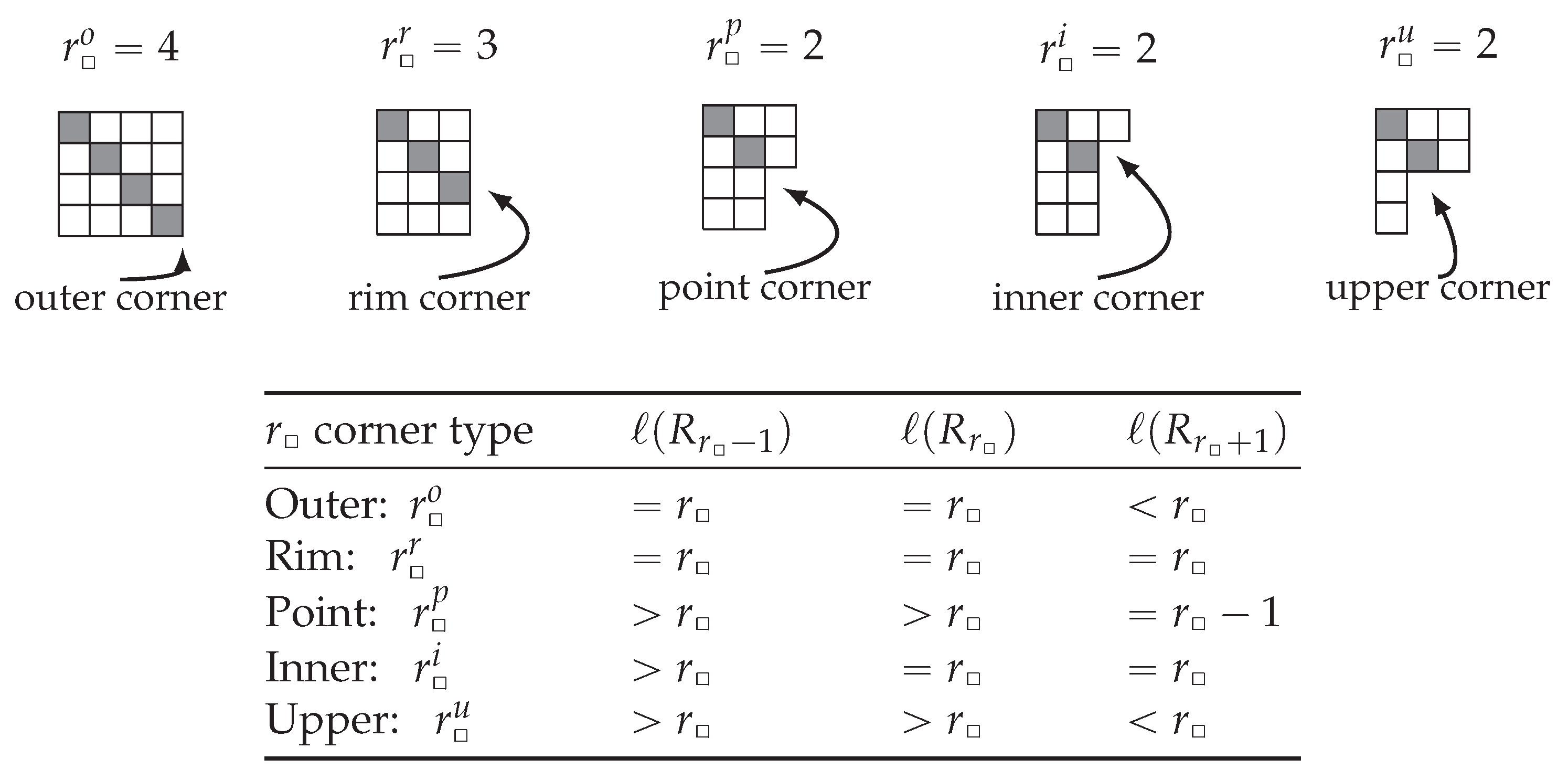

with a maximal partition integer as the top row and each subsequent row below the top row representing a partition integer less than or equal to its predecessor row partition integer.

with a maximal partition integer as the top row and each subsequent row below the top row representing a partition integer less than or equal to its predecessor row partition integer. is referred to as an inner corner of the Young diagram while a

is referred to as an inner corner of the Young diagram while a  corner is called an outer corner. Figure 1 displays five types of corners associated with , each of which relays different information regarding the large degree structure of a graph. Let indicate the lowest (from the top) degree diagram row that includes , and let denote the length of this row. The row above is row and the row below is row . The table at the bottom of Figure 1 reflects the relationship of each corner type with respect to the degree diagram rows , and .

corner is called an outer corner. Figure 1 displays five types of corners associated with , each of which relays different information regarding the large degree structure of a graph. Let indicate the lowest (from the top) degree diagram row that includes , and let denote the length of this row. The row above is row and the row below is row . The table at the bottom of Figure 1 reflects the relationship of each corner type with respect to the degree diagram rows , and .2.5. Metric Dimension

2.5.1. Known Metric Dimensions

2.5.2. Distance Matrix and Metric Dimension

2.5.3. Diameter and Metric Dimension

2.5.4. Degree and Metric Dimension

2.5.5. Twin Vertices and Metric Dimension

2.6. Social Network Background

3. Data Collection Methods and Approach

3.1. Data Collection Methods

- Total student enrollment is between 25,000 and 30,000 with a primary campus that includes a medical school and hospital. Primary campus is defined as containing at least 70% of the student population.

- The basic structure of all three discipline departments is fundamentally the same; so each department has an applied faculty who work on medically related mathematics along with general research areas for that discipline.

3.2. Data Approach - Representative Papers

3.3. Collaboration Group Size

4. People, Papers and Graphs

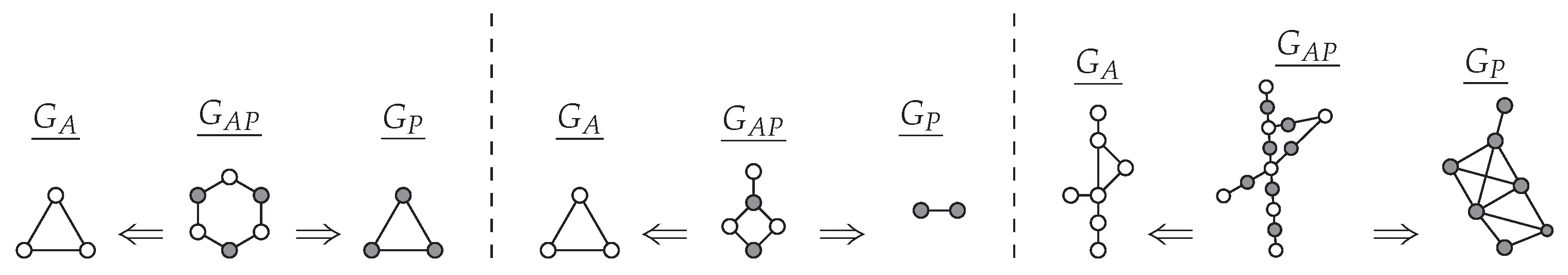

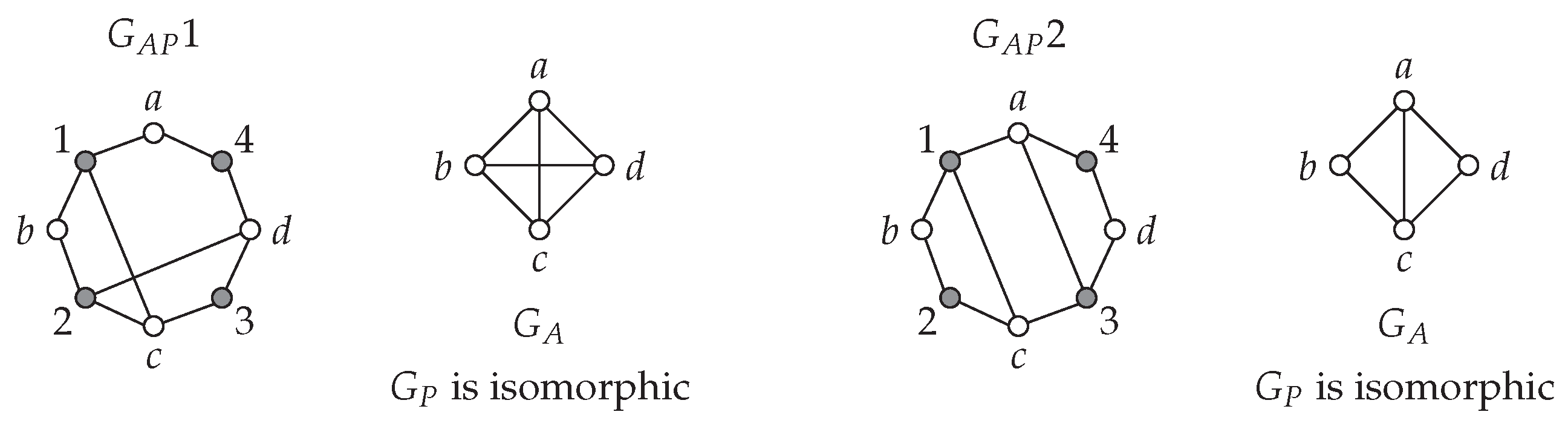

4.1. Projection Graphs

4.2. Construction of Projection Graphs from CNM

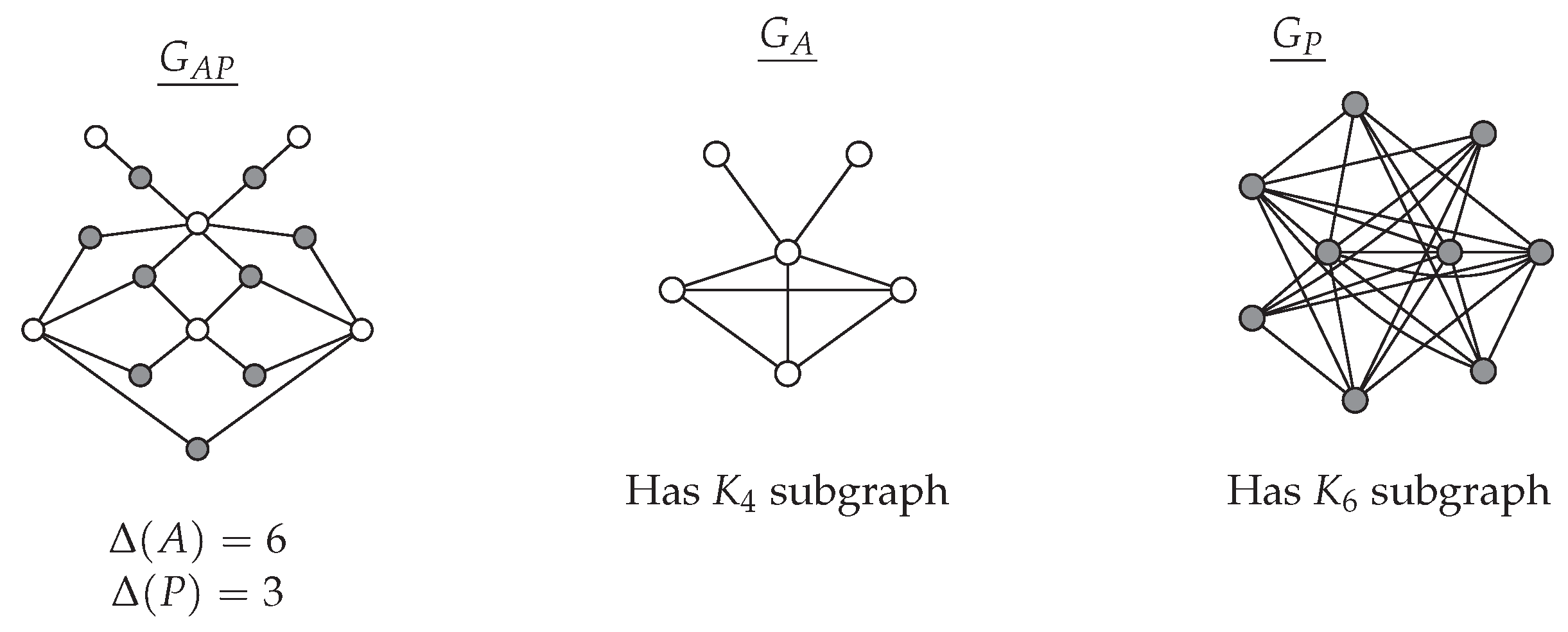

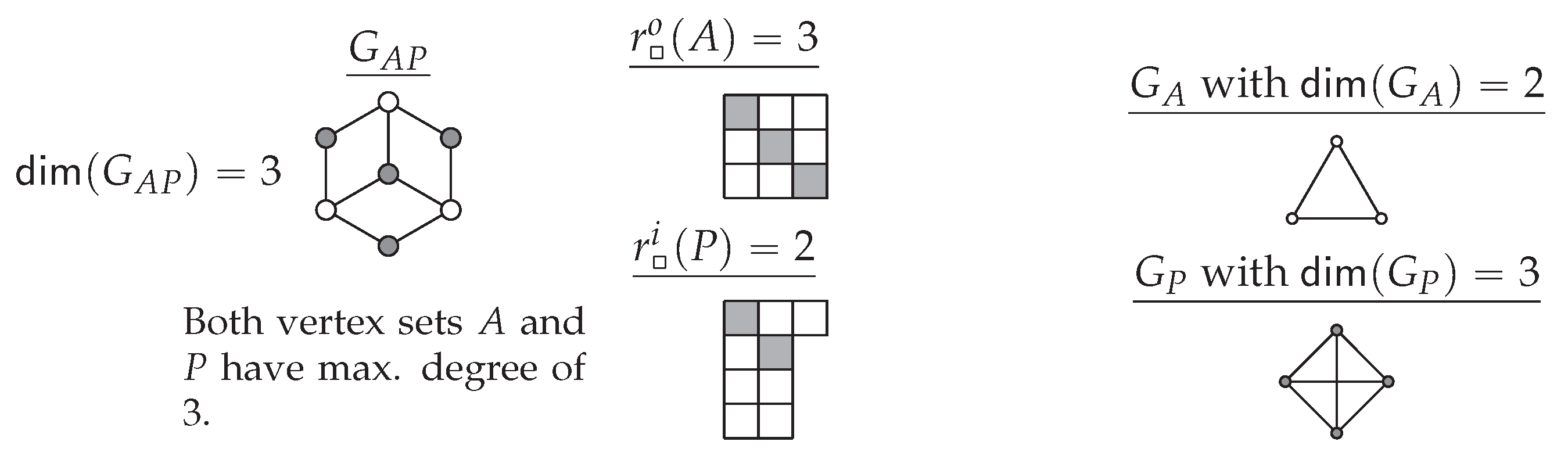

5. Structural Specifics of the Authors with Papers Graph

5.1. Pendants, Degrees and Neighborhoods

- 1.

-

Pendant vertices and pendant chains:

- (a)

- In any , only authors can be a pendant vertex.

- (b)

- Any pendant author in a is also pendant in its .

- (c)

- Any pendant chain in a includes at least one author and one paper.

- (d)

- Any pendant paper in a is not pendant in the related .

- (e)

- Any pendant vertex in a must be in a pendant chain with minimum length of 3 in the related .

- 2.

-

Degree and Durfee rank: Since only authors can be pendant vertices in a , the minimum possible degree for authors is 1 while that of papers is 2.

- (a)

- For the set of paper vertices in a , .

- (b)

- For author vertices in a , .

- (c)

- can be greater than either or .

- (d)

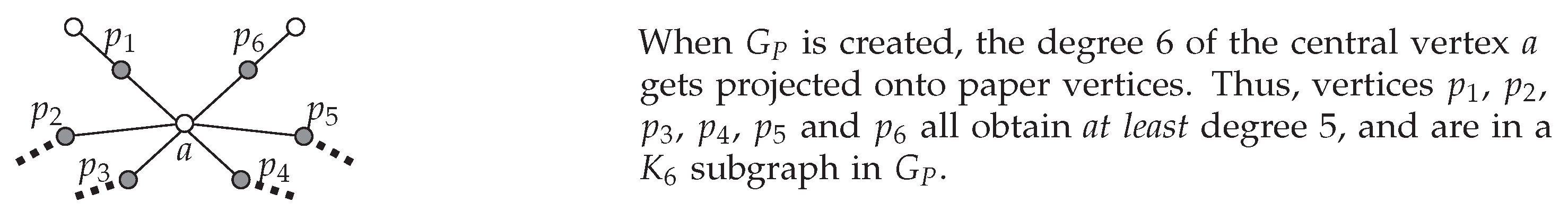

- In a , vertex always projects to a that has at least one neighbor in the .

- (e)

- Vertex p can project to an a vertex that has no other neighbor (i.e. a is pendant).

- 3.

-

Neighborhoods: Each paper is a representative paper resulting in unique neighborhoods for all papers in any .

- (a)

- No paper vertex can be a twin of another paper vertex in a .

- (b)

- Author vertices can be in more than one twin pair.

- (c)

- All bipartite are planar due to the distinct neighborhoods of all p vertices.

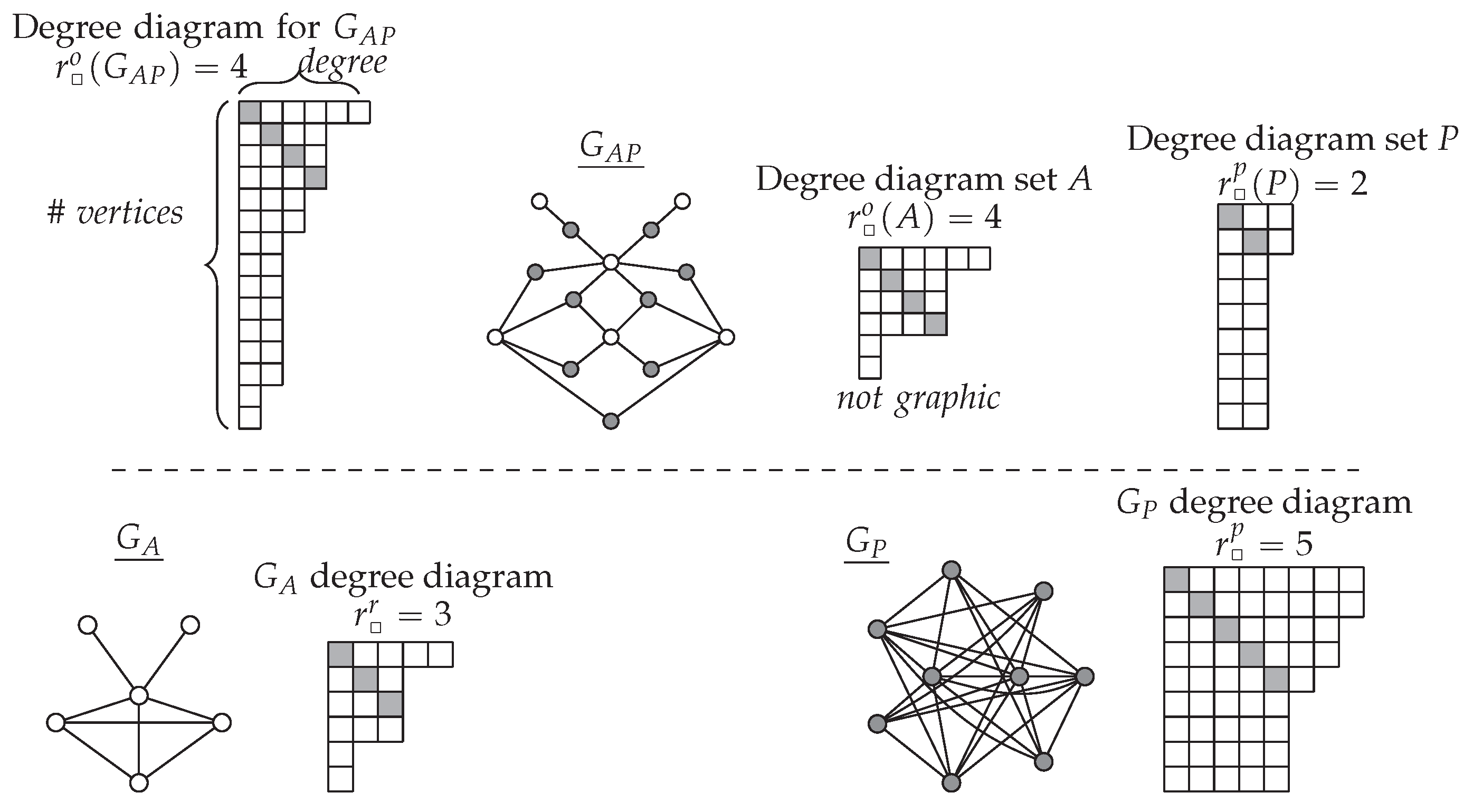

5.2. Degree Projection

6. Social Aspects of the Data Collected

6.1. Analysis of University Data

6.2. Analysis of Discipline Data: Hubs Analysis

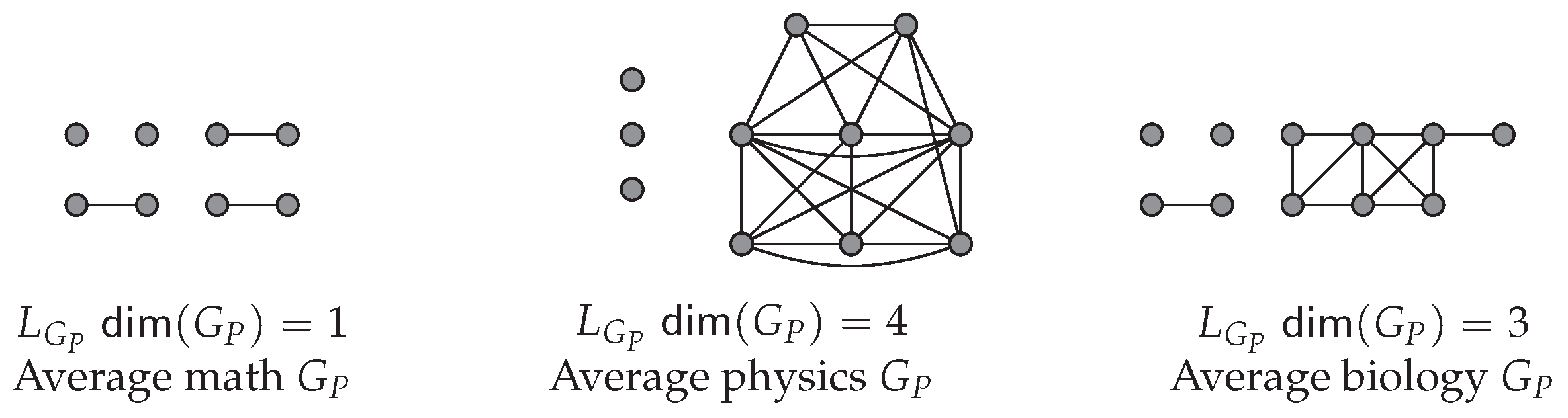

7. The Nine Average Graphs

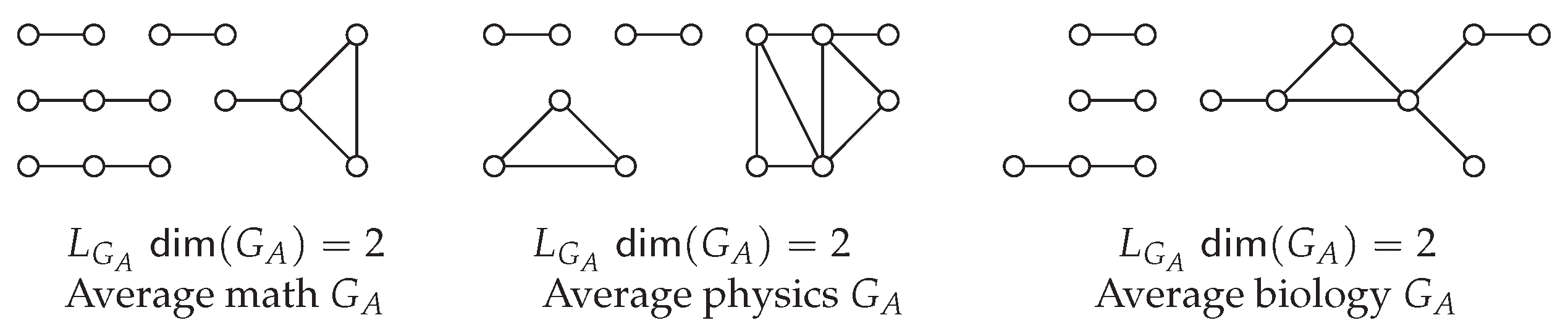

7.1. Authors Only Average Graphs and Analysis

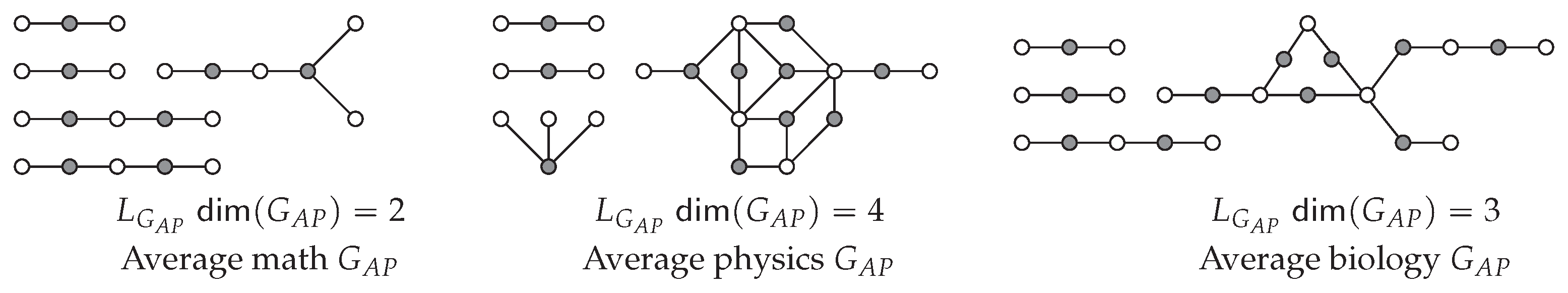

7.2. Authors with Papers Average Graphs and Analysis

7.3. Papers Only Average Graphs and Analysis

8. The Degree Diagram and the Durfee Rank

9. The Metric Dimension of the Authors with Papers Graph

9.1. Changes Between the Three Data Derived Average Graphs

9.1.1. Metric Dimension in Average Mathematics Graphs:

9.1.2. Metric Dimension in Average Physics Graphs:

9.1.3. Metric Dimension in Average Biology Graphs:

9.2. Double Distance and Diameter

9.3. Using the DM for Any Graph’s Metric Dimension

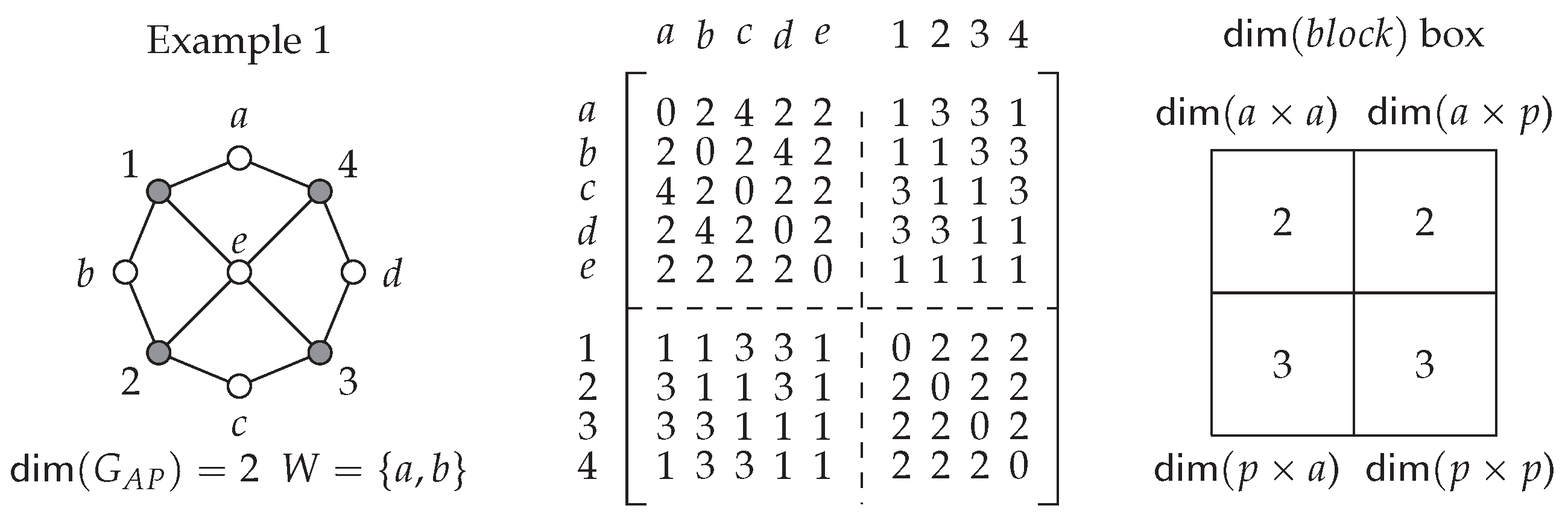

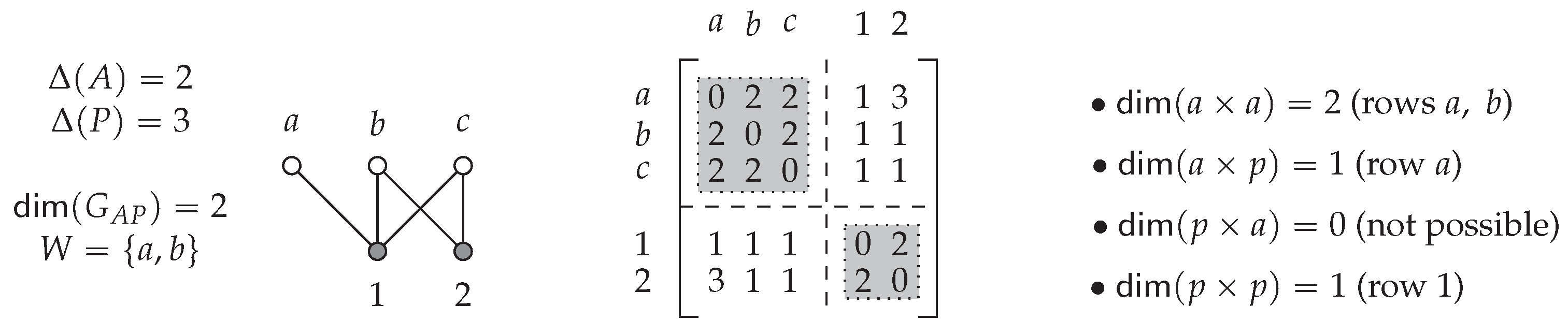

9.4. DM Block Resolving

9.5. DM Block Characteristics

9.5.1. Even Blocks:

9.5.2. Odd Blocks

9.6. DM Block Resolving Examples

9.6.1. Example 1:

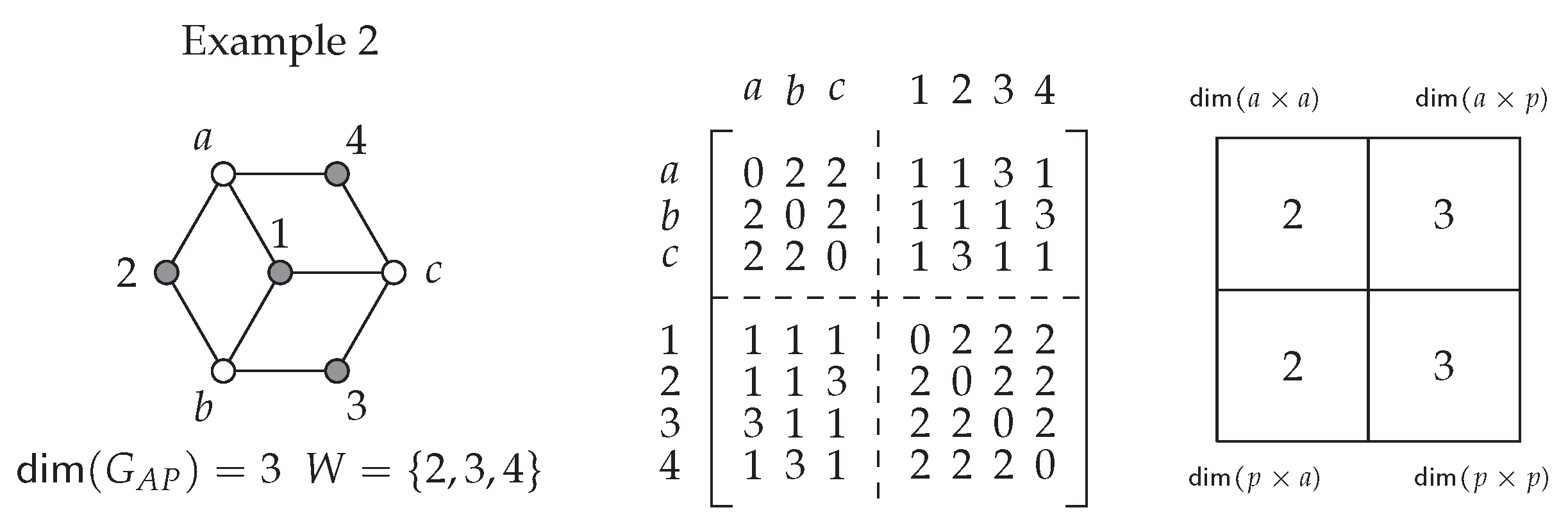

9.6.2. Example 2:

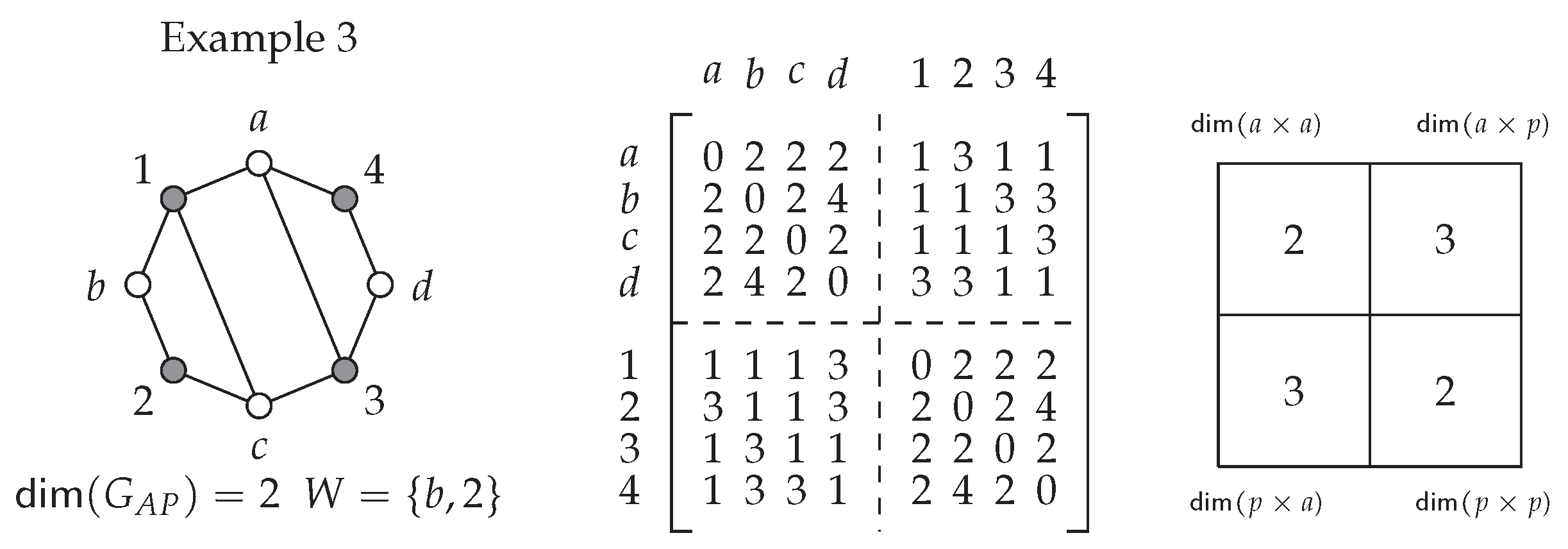

9.6.3. Example 3:

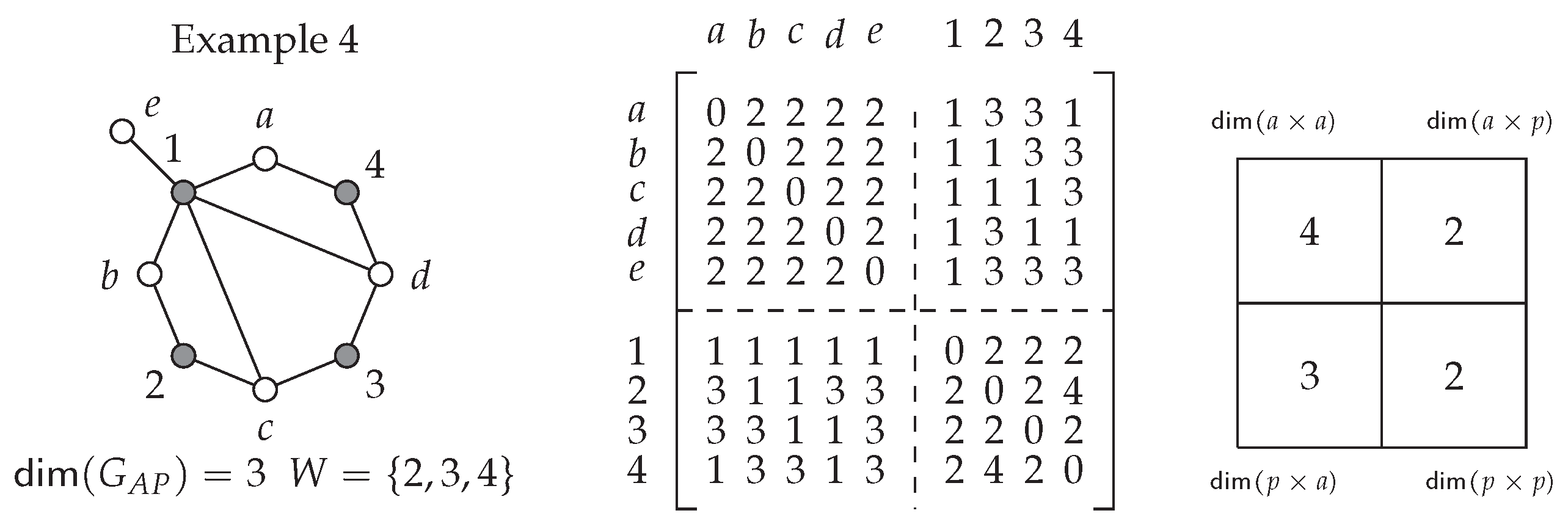

9.6.4. Example 4:

9.7. Relation of the DM Blocks to the Projection Graphs

9.8. Complete Graph Double Subblocks

9.9. Existence of Twin Pairs

10. Conclusions

10.1. Conclusions Regarding Social Aspects

10.2. Conclusions Regarding Network Analysis

References

- Anderson TR, Hankin RKS, Killworth PD (2008) Beyond the Durfee square: Enhancing the h-index to score total publication output. Scientometrics 76(3):577-588. [CrossRef]

- Andrews GE, Eriksson K (2004) Integer Partitions. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

- Anuradha A, Amutha B A study on metric dimension of some families of graphs. AIP Conference Proceedings 2019 2112(1):1-5. [CrossRef]

- Baca M, Baskoro ET, Salman ANM, Saputro SW, Suprijanto D (2011) The metric dimension of regular bipartite graphs. Bulletin mathématiques de la Société des sciences mathématiques de Roumanie 54(102):15-28. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard CG, Becker JV, Bristow AR (1979) Attitudes of Southern Women: Selected Group Comparisons. Psychology of Women Quarterly 1(2):160-171. [CrossRef]

- MCarey MR, Johnson DS (1979) Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. W. H. Freeman & Co., New York, NY.

- Cartwright D, Harary F (1956) Structural balance: a generalization of Heider’s Theory. The Psychological Review 63(5):277-293. [CrossRef]

- Chartrand G, Ehoh L, Johnson MA, Oellermann OR (2000) Resolvability in graphs and the metric dimension of a graph. Discrete Applied Mathematics 105:99-113. [CrossRef]

- Chartrand G, Lesniak L, Zhang P (2016) Graphs & Digraphs, 6th Ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Cummins CJ, King RC (1987) Young diagrams, supercharacters of OSp(M/N) and modification rules. Journal of Physics, A: Mathematical and General 20:3103-3120. [CrossRef]

- Diaz J, Pottohen O, Serna M, van Leeuwen EJ (2017) Complexity of metric dimension on planar graphs. Journal of Computer and System Sciences. 83:132-158. [CrossRef]

- Diestel R (2017) Graph Theory, 5th Ed. Springer: Graduate Texts in Mathematics series, Berlin.

- Harary F, Norman RZ (1953) Graph theory as a mathematical model in social science. Bulletin de l’Institut de recherches économiques et sociales 26(8). [CrossRef]

- Harary F, Melter RA (1976). On the metric dimension of a graph. Ars Combinatoria 2:191–195.

- Hartung S, Nichterlein A On the parameterized and approximation hardness of metric dimension. 2013 IEEE Conference on Computational Complexity Stanford University. Palo Alto, CA. 266–276. [CrossRef]

- Heinz T, Shapira P, Rogers JD, Senker JM(2009) Organizational and institutional influences on creativity in scientific research. Research Policy 38:610-623. [CrossRef]

- Janežič D, Miličević A, Nikolić S, Trinajstić N (2015) Graph-Theoretical Matrices in Chemistry, 2nd Ed. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL.

- Kyvik S, Reyert I (2017) Research collaboration in groups and networks: differences across academic fields. Scientometrics 113:951-967. [CrossRef]

- Lovász L (2010) Graphs and Geometry. American Mathematical Society. Volume 65. Providence, RI.

- Merris R (2003) Combinatorics, 2nd Ed. Wiley Interscience, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, NJ.

- Merris R (2001) Graph Theory. Wiley Interscience, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, NJ.

- Merton RK (1968) The Matthew effect in science. Science. 159(3810):56-63. [CrossRef]

- Milgram S (1967) The small-world problem. Psychology Today 1(1, May):61-67. [CrossRef]

- Newman M (2001) The structure of scientific collaborations networks. PNAS 98(2):404-409. [CrossRef]

- Girvan M, Newman MEJ (2002) Community structure in social and biological networks. PNAS-06 99(12):7821-7826. [CrossRef]

- Newman M (2004) Coauthorship networks and patterns of scientific collaboration. PNAS 101(1):5200-5205. [CrossRef]

- Newman MEJ (2005) Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf’s law. Contemporary Physics. 46(5):323–351. [CrossRef]

- Newman M (2018) Networks, 2nd Ed. Oxford Press. Oxford, England.

- Prabhu S, Jeba SR, Stephen S (2025) Metric dimension of a star fan graph. Scientific Reports 15(102). 102-108. [CrossRef]

- de Solla Price DJ (1965) Networks of scientific papers: the pattern of bibliographic references indicates the nature of the scientific front. Science 149(3683):510-515. [CrossRef]

- Ruscio J, Seaman F, D’Oriano C, Stremlo E, Mahalchik K (2012) Measuring scholarly impact using modern citation-based indices. Measurement 10:123-146. [CrossRef]

- Schriba I, Farrugia S (2011) On the spectrum of threshold graphs. ISRN Discrete Mathematics 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Slater PJ (1975). Leaves of trees (Proc. 6th Southeastern Conference on Combinatorics, Graph Theory, and Computing, Florida Atlantic Univ., Boca Raton, FL) Congressus Numerantium 14:549–559.

- Tillquist RC, Frongillo RM, Lladser ME (2023) Getting the lay of the land in discrete space: a survey of metric dimension and its applications. SIAM Review 65(4):919-962. [CrossRef]

- Trinajstić N (1992) Chemical Graph Theory. Taylor and Francis, LLC; Boca Raton, FL.

- van Rijnsoever FJ, Hessels LK, Vandeberg RIJ (2008) A resource-based view on the interactions of university researchers. Research Policy 37:1255-1266. [CrossRef]

- Tapendra BC, Dueck S (2025) The metric dimension of circulant graphs. Opuscula Mathematica 45(1):39-51. [CrossRef]

- Wagner CS, Leydesdorff L (2005) Network structure, self-organization, and the growth of international collaboration in science. Research Policy 34:1608-1618. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Tian F, Liu Y, Pang J, Miao L (2023) On graphs of order n with metric dimension n-4. Graphs and Combinatorics 39(29):1-18. [CrossRef]

- Watts DJ (2003) Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age. W.W. Norton & Co., New York, NY.

- Watts DJ, Strogatz SH (1998) Collective dynamics of the ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 3393:440-442. [CrossRef]

| Discipline | Mean # faculty | Mean # and (%) collaborate |

|---|---|---|

| Math | 29 | 14 (48%) |

| Physics | 26 | 13 (50%) |

| Biology | 27 | 14 (52%) |

| Discipline | Total | chair | - | Total | chair |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # hubs | as hub | - | # hub | as hub | |

| Math | 9 | 1 | - | 11 | 2 |

| Physics | 5 | 1 | - | 9 | 0 |

| Biology | 8 | 1 | - | 8 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).