1. Introduction

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is the leading cause of anovulation globally, impacting up to 8 out of 10 women with this condition [

1]. It has been estimated that up to 9-18% women of reproductive age suffer from PCOS [

2]. PCOS is widely diagnosed in clinical practice based on the 2003 Rotterdam consensus criteria, with a diagnosis made if any two features out of oligo-anovulation (irregular menstrual cycles), clinical or sub-clinical/biochemical hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) on ultrasound, are present [

3]. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AEPCOS) criteria for diagnosing PCOS focuses on hyperandrogenism [

4]. A woman is diagnosed with PCOS as per AEPCOS guidelines if she exhibits clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism, plus signs of oligo-anovulation or PCOM on ultrasound. PCOS is associated with co-morbidities such as obesity, dyslipidemia, infertility, and metabolic syndrome; and long-term sequelae such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and endometrial cancer [

5,

6,

7].

At the systemic level, the pathophysiology of PCOS is orchestrated by an interplay of endocrinologic and metabolic abnormalities. These include aberrant gonadotropin secretion patterns with a shift of balance towards elevated luteinizing hormone (LH) levels, insulin resistance leading to compensatory hyperinsulinemia, both of which directly and indirectly lead to clinical or sub-clinical hyperandrogenemia. At the tissue level, PCOS is also characterized by local hyperandrogenism in the ovaries. Disturbed intra-ovarian microenvironment together with systemic impairments lead to the arrest of developing pre-antral follicles resulting in the characteristic PCO Morphology. At the ovarian level, follicles in PCOS patients also exhibit relative resistance to the stimulatory effect of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). Follicular resistance to FSH signaling in PCOS may be intrinsic to the disease, secondary to intra-ovarian hyperandrogenism, as well as consequent to elevated levels of anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) secreted by the growing cohort of pre-antral follicles [

8]. Together, these mechanisms result in impaired cyclic development and arrest of follicles in PCOS [

9].

Elevated serum LH appears to be a key factor leading to increased AMH levels in PCOS patients. Acting synergistically with elevated serum insulin, LH promotes AMH synthesis both directly, as well as indirectly by increasing androgen production from ovarian theca cells [

10,

11,

12]. At the level of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, PCOS patients have been shown to exhibit increased LH pulse amplitude as well as pulse frequency, which traces back to impairments in the hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator.

GnRH agonists have been used over the past few decades in ovarian stimulation (OS) regimens to optimize in-vitro fertilization (IVF) outcomes by controlling premature LH surges, preventing premature ovulation, and achieving predictable ovarian response. GnRH antagonists are currently preferred, especially in PCOS patients. Advantages associated with the use of GnRH antagonists include quick and reversible pituitary suppression, correction of the deranged internal hormonal milieu, and reduction in the incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Risk of OHSS is usually further minimized by using a GnRH agonist trigger for final oocyte maturation, preferably followed by elective embryo cohort cryopreservation and frozen embryo transfer (FET).

It has been conclusively demonstrated that IVF outcomes with GnRH antagonists are comparable to those with GnRH agonists, with the added advantage of significantly reduced risk of OHSS [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In addition, it has been shown that use of antagonists in OS regimens is associated with a reduction in the duration of stimulation and total dosage of gonadotropins used in IVF cycles, compared to GnRH agonists [

21,

22,

23,

24].

Numerous studies have compared IVF outcomes between patients undergoing OS using GnRH agonist versus flexible day 5/day 6 antagonist protocols. However, there is scarce data comparing use of GnRH antagonists from day 1 of IVF stimulation versus standard flexible antagonist administration from day 5/6 in PCOS patients undergoing IVF cycles, in terms of possible impact on quantitative and qualitative laboratory as well as clinical outcome parameters such as number of oocytes retrieved, fertilization rate resulting in optimal 2PN embryos, number of embryos formed, proportion of top quality embryos achieved, and pregnancy rates. Theoretically speaking, if it is assumed that GnRH antagonist mediated suppression of elevated serum LH levels in PCOS patients during OS is likely to improve the impaired internal hormonal milieu and thereby optimize IVF outcomes, it stands to reason that it may be of benefit to administer antagonists from day 1 of stimulation itself.

Indeed, differences in serum LH levels have been reported in the follicular phase of IVF stimulation between patients undergoing OS by agonist protocol, versus GnRH antagonists from day 1 of stimulation [

25]. Unfortunately, a 3-arm study comparing early antagonist use from day 1 of stimulation, versus flexible antagonist administration from day 5 or day 6, versus agonist protocols, was not designed to evaluate qualitative aspects of laboratory parameters but reported that number of oocytes obtained were similar between the three protocols; and that clinical pregnancy rates showed a higher trend in the early antagonist group, although without statistical significance [

26].

Thus, there is strong scientific rationale and need to investigate whether administration of GnRH antagonists from day 1 of IVF stimulation may result in better laboratory and clinical outcomes compared to standard flexible protocol of administering GnRH antagonists from day 5 or day 6 of OS.

We presented our experience of achieving favorable IVF outcomes using GnRH antagonists from the first day of ovarian stimulation in PCOS patients in a case series at the Annual Congress of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) [

27]. Since then, we have been employing this strategy in our routine clinical practice for OS in selected PCOS patients undergoing IVF cycles. The present retrospective cohort study was designed to compare laboratory and clinical outcomes of IVF in PCOS patients using GnRH antagonists from day 1 of stimulation versus standard protocol of flexible antagonist administration from day 5 or day 6 of OS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting, Ethics, and Informed Consent

This retrospective cohort study was carried out at a leading fertility research institute associated with an university medical college and tertiary care multi-specialty hospital, in collaboration with a leading private fertility institute. Following Institutional Ethical clearance, PCOS patients who had undergone IVF using antagonist cycles from January 2025 to June 2025 were included in the study. Informed, written consent for participation was obtained from all patients who agreed to have their IVF cycle data analyzed as part of this study. Moreover, all patients provided unlimited permission for publication of study results in all formats (print, electronic, online), as long as their identity was masked, anonymity strictly safeguarded, and personally identifiable data kept confidential.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria and Outcome Measures

Patients with history of Grade III or Grade IV endometriosis, as well as patients with concurrent male factor infertility, were excluded from the study. To ensure interpretability of results, only conventional IVF cycles were included and all cycles with Intra-cytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) were excluded from the analysis. The clinical outcome measure was cumulative clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) over a maximum of 3 embryo transfer cycles (fresh and/or frozen). The laboratory outcome measures were oocyte yield, proportion of oocytes fertilized by conventional IVF (fertilization rate), and proportion of top quality embryos obtained.

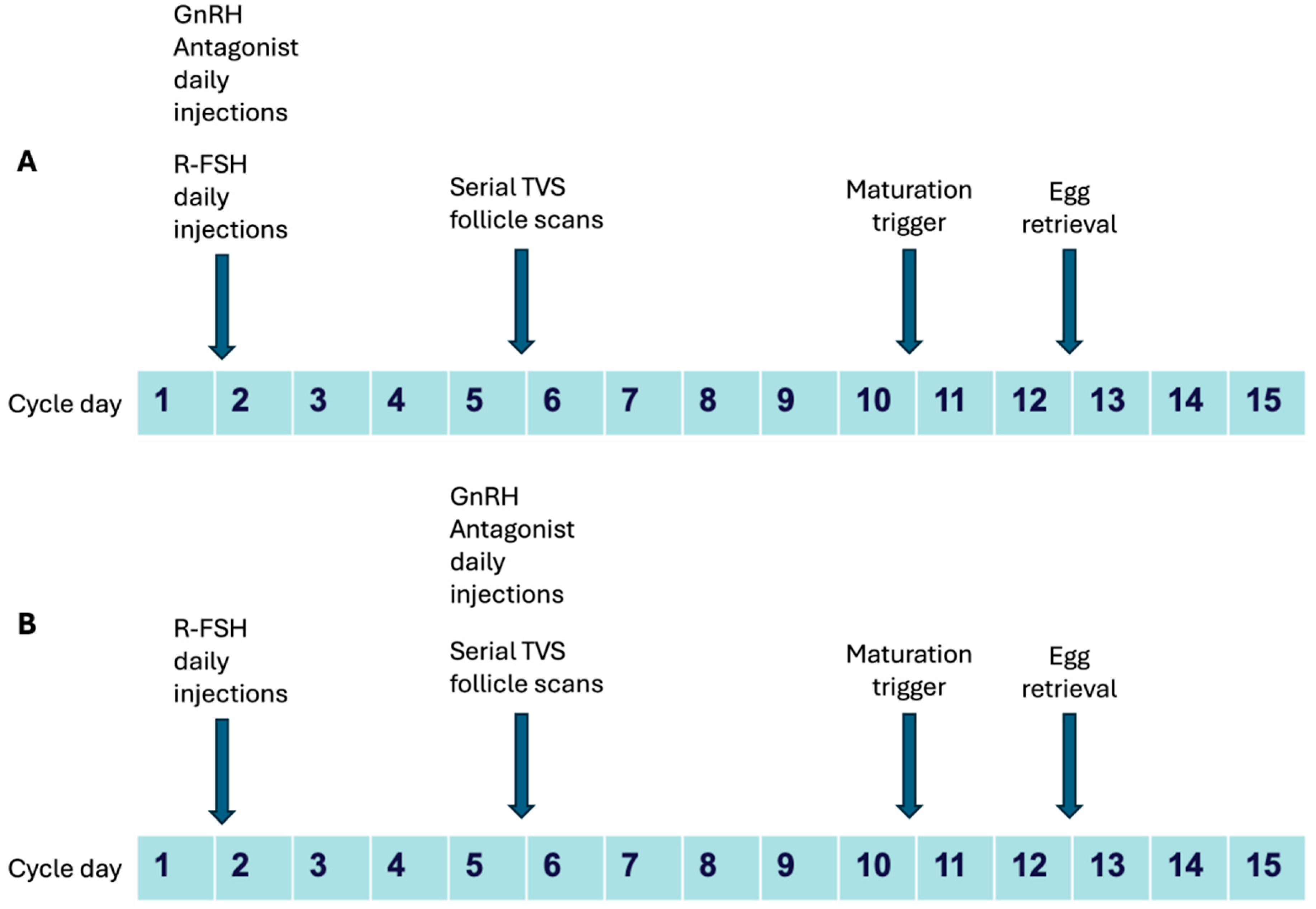

2.3. Clinical Protocol

Most patients had undergone ovarian stimulation with a starting dose of 100-200 IU of recombinant follicle stimulating hormone (r-FSH/Follitropin alpha, Folisurge, Intas Ltd.) from day 1 or day 2 of menstrual cycle (going up to 225 IU in few patients), and dose adjustment done following serial serum estradiol (E2) estimation and follicle tracking by transvaginal sonography (TVS) from day 5 or day 6 of stimulation. Patients who had been administered GnRH antagonist in the form of 0.25 mg Cetrorelix acetate daily injections (Cetrolix, Intas Pharmaceuticals) early from day 1 of stimulation were considered as Group 1 (Test cohort) and patients who had received 0.25 mg Cetrorelix acetate daily injections from Day 5 or Day 6 as per standard flexible protocol were considered as Group 2 (Control cohort). Trigger for final oocyte maturation was given with 250 mcg recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (r-hCG, Ovitrelle, Merck Ltd.) or bolus GnRH agonist administration using a total of 0.1×2 mg triptorelin (Decapeptyl, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) when at least 2-3 follicles measured 18 mm or more on TVS. Egg retrievals were performed 34-36 hours after maturation trigger by standard TVS guided protocol. Typical stimulation protocols are shown schematically in

Figure 1.

2.4. Laboratory Protocol

COCs were inseminated by conventional IVF in all patients using 15,000-20,000 sperm per COC. Fertilization was confirmed by documenting 2-PN stage 17-18 hours post insemination (hpi). Embryos were cultured under standard IVF embryo culture conditions in conventional benchtop incubators (Origio, CooperSurgical). On day 3 following fertilization, all embryos were graded by morphological analysis of still images under inverted optical microscope (Olympus, Japan), as per ESHRE-ALPHA Scientists Istanbul Consensus criteria [

28]. Following embryo grading on day 3, majority of embryos were cryopreserved across both groups for subsequent frozen-thawed transfers. However, fresh embryo transfers had been performed in certain patients based on various factors (clinical, number of oocytes/embryos, patient preference etc). Majority of transfers across both groups were blastocyst transfers, although a few patients were transferred cleavage stage embryos as well. Cryopreservation of embryos was performed by standard vitrification protocol using Cryotop vitrification kits (Kitazato, Japan).

2.5. Embryo Transfer and Cryopreservation

All embryos were transferred under abdominal ultrasound guidance using Wallace embryo transfer catheters (CooperSurgical, USA). All ETs and FETs were performed by the same clinician with an experience of over ten thousand embryo transfers since 1984. For FETs, embryo warming had been done by standard protocols using Kitazato kits and transfers done in artificially prepared cycles using hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with estradiol valerate (Progynova 4 mg-8 mg per day, Bayer-Zydus Pharma Ltd.), followed by intramuscular progesterone injections (Gestone, 50 mg per day, Ferring Pharmaceuticals), once endometrial thickness reached 7 mm or more.

Patients with both cleavage stage embryo transfers as well as those with blastocyst transfers were included when analyzing pregnancy outcomes. A maximum of 2 embryos were transferred at any single embryo transfer. Fresh transfers were only performed in cycles triggered with r-hCG.

2.6. Luteal Support and Documentation of Pregnancy

Luteal support was given as per standard protocol with 50 mg intramuscular progesterone injections for 2 weeks followed by application of 8% micronized progesterone (Crinone 8%, Merck Ltd.) vaginally till 10 weeks of gestation. Biochemical pregnancy was documented by serial serum beta-hCG estimations 48 hours apart around 2 weeks following embryo transfer; followed by confirmation of viable clinical pregnancy by transvaginal sonographic demonstration of fetal heartbeat at 5-6 weeks of gestation.

2.7. Retrospective Cohort Analysis: Embryo Grading

Oocyte yield, fertilization rate, top quality embryo rate, and pregnancy rates were analyzed for the two cohorts retrospectively. For retrospective cohort analysis of top-quality embryo rate, day 3 cleavage stage embryo images were used as embryos had been vitrified at that stage in many cases and were still in storage. Each embryo was graded independently by 3 different embryologists in blinded fashion. Embryologists who graded the embryos were not aware of the group allocation of the patient, or of the scores given by the others. Embryo grading was done as per the updated ESHRE-ALPHA scientists Istanbul consensus criteria. Any differences in grade were resolved by consensus.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Numerical data was tabulated in Microsoft Excel sheets and descriptive summary statistics performed. Statistical analysis of data was performed using Python version 3.11.13 for analytical statistics. Independent samples Student’s T test was used to estimate differences between means and Z test was used to estimate differences between proportions/rates with any difference considered to be statistically significant when p < 0.05.

2.9. Final Data Presentation

Total 100 patients’ data was analyzed. Cumulative pregnancy data was analyzed over a maximum of 3 transfer cycles- 1 fresh cycle (when performed) and up to a maximum of 2 frozen transfers. Outcomes were compared between Group 1 (Day 1 antagonist, n = 45) and Group 2 (Day 5/day 6 antagonist, n = 55). Pregnancy data is presented only for 97 patients, as 3 patients in Group 1 did not have embryo transfers. Miscarriage rates (MR) and ongoing pregnancy rates (OPR) could not be calculated because some of these patients are currently pregnant below 10 weeks of gestation

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Parameters

Baseline parameters such as age, body mass index (BMI), AMH, and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels were found to be comparable between the two groups, as shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Laboratory Outcome Measures

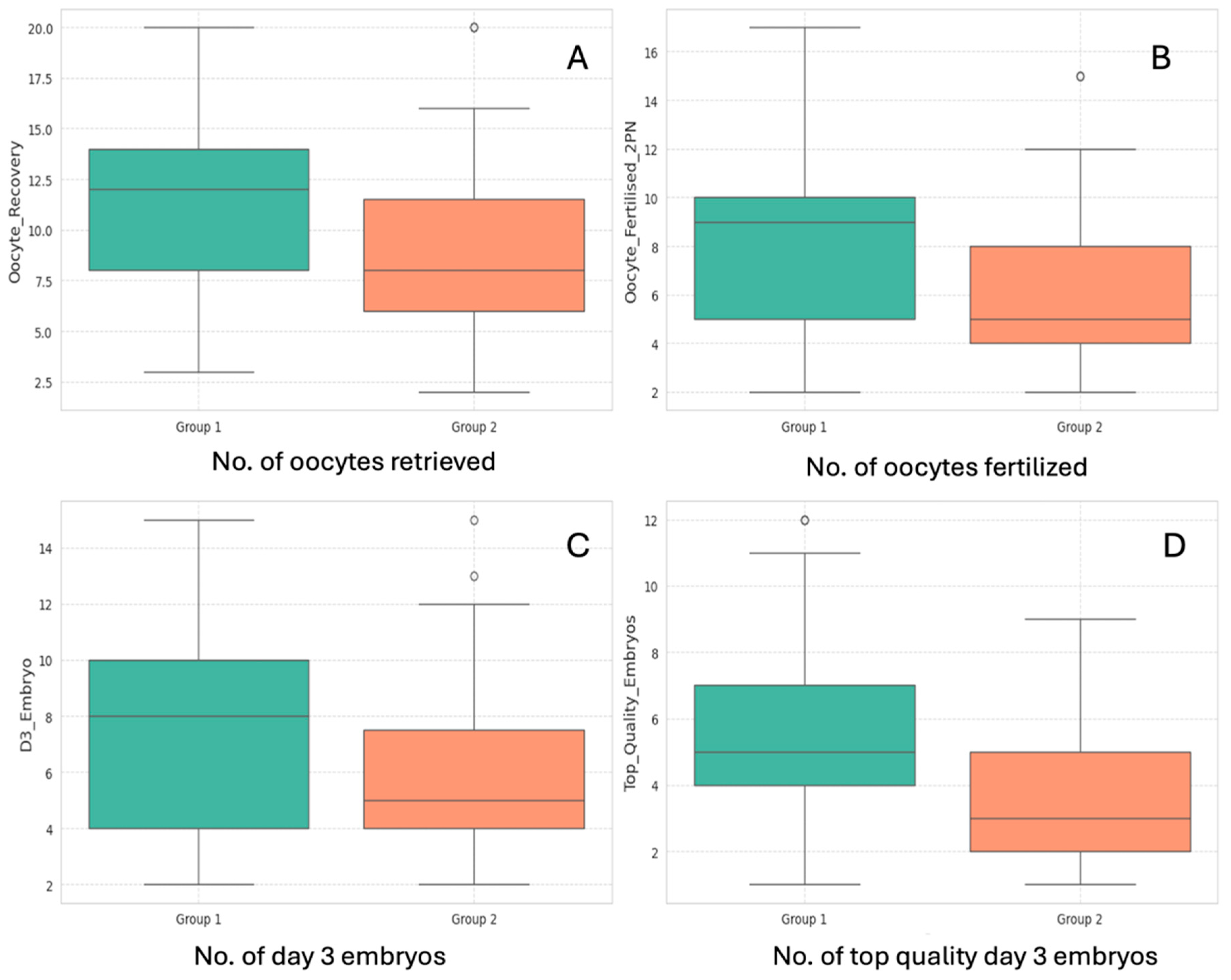

Laboratory data are summarized in

Table 2. Laboratory outcome measures such as number of oocytes/COCs retrieved, number of oocytes fertilized (2PN number), number of day 3 cleavage stage embryos formed, and number of top-quality day 3 embryos generated were all significantly higher in the Day 1 antagonist group (Group 1), as shown in

Figure 2. Data distribution for all 4 variables have been graphically represented in

Figure 3.

Table 2.

Comparison of laboratory outcome measures.

Table 2.

Comparison of laboratory outcome measures.

| Outcome Measure |

Group 1 (Day 1 Antagonist): Mean ± S.D |

Group 2 (Day 5/Day 6 Antagonist): Mean ± S.D |

t-value |

p value |

Statistical significance |

| No. of oocytes retrieved (COCs) |

11.47 ± 4.37 |

8.95 ± 3.88 |

3.05 |

<0.01 |

S ** |

| No. of oocytes fertilized (2 PN Number) |

8.13 ± 3.71 |

6.27 ± 3.20 |

2.69 |

<0.01 |

S |

| No. of Day 3 cleavage stage embryos formed |

7.40 ± 3.33 |

5.82 ± 2.96 |

2.51 |

p = 0.01 |

S |

| No. of top quality Day 3 embryos |

5.73 ± 2.63 |

3.69 ± 2.25 |

4.15 |

<0.01 |

S |

Figure 2.

Comparison between (A) number of oocytes/COCs retrieved, (B) Number of oocytes fertilized to 2PN stage, (C) number of day 3 embryos, and (D) number of top-quality embryos; between Group 1 (Day 1 Antagonist, in Green) and Group 2 (Day 5/day 6 Antagonist, in Orange).

Figure 2.

Comparison between (A) number of oocytes/COCs retrieved, (B) Number of oocytes fertilized to 2PN stage, (C) number of day 3 embryos, and (D) number of top-quality embryos; between Group 1 (Day 1 Antagonist, in Green) and Group 2 (Day 5/day 6 Antagonist, in Orange).

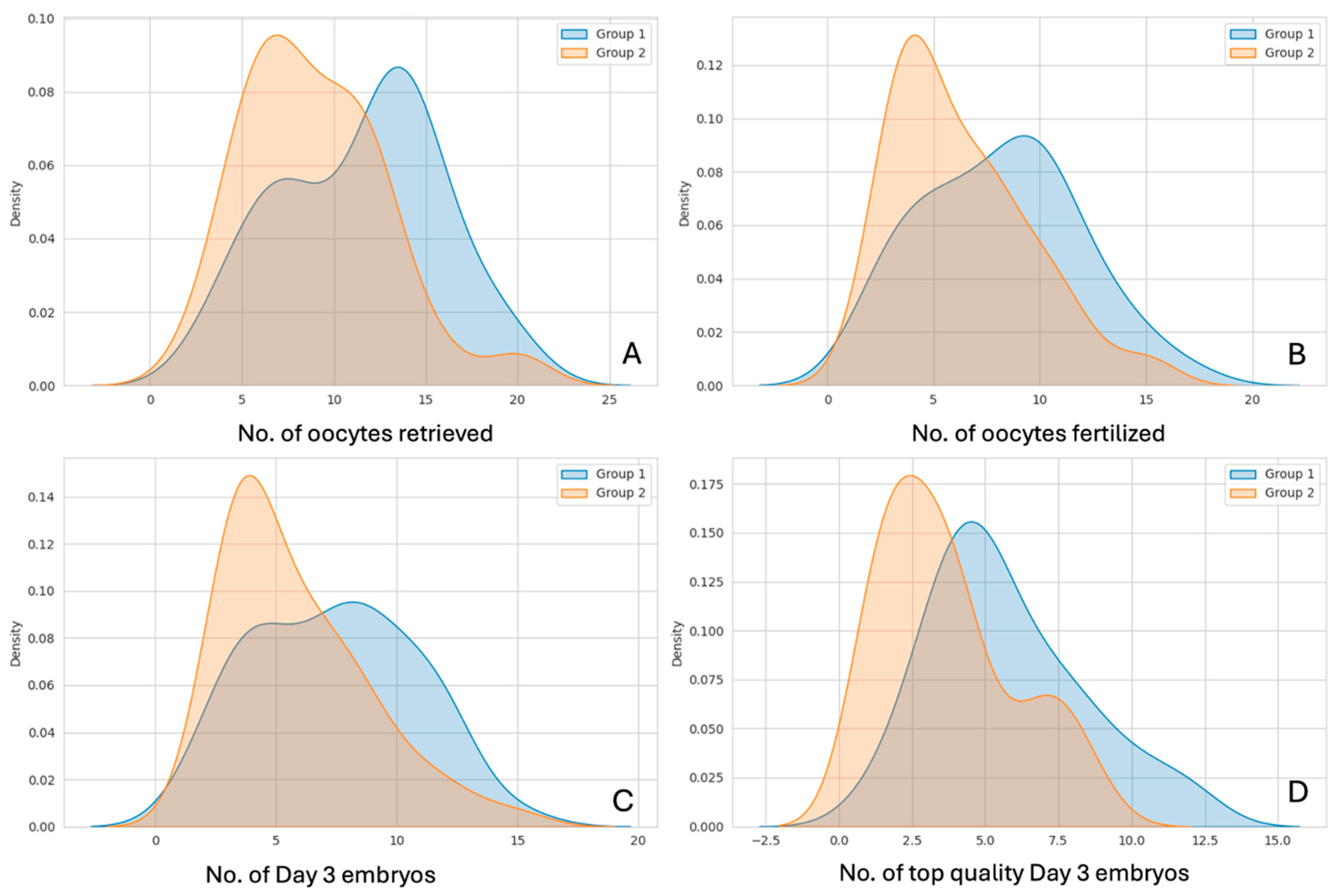

Density distributions of the above 4 parameters are shown in

Figure 3, for Group 1 (Antagonists from day 1) vs. Group 2 (Antagonists from day 5 or day 6)

Figure 3.

Density distributions of (A) number of oocytes/COCs retrieved, (B) Number of oocytes fertilized/2PN Number, (C) number of day 3 embryos formed, and (D) number of top-quality embryos formed; compared between Group 1 (Day 1 Antagonist, in Blue) and Group 2 (Day 5/day 6 Antagonist, in Red).

Figure 3.

Density distributions of (A) number of oocytes/COCs retrieved, (B) Number of oocytes fertilized/2PN Number, (C) number of day 3 embryos formed, and (D) number of top-quality embryos formed; compared between Group 1 (Day 1 Antagonist, in Blue) and Group 2 (Day 5/day 6 Antagonist, in Red).

However, it was likely that the number of fertilized oocytes (2PN number) and number of Day 3 embryos formed would be greater in Group 1 as the number of oocytes retrieved and inseminated was significantly higher in Group 1. Hence, for better interpretability we compared the proportion of oocytes fertilized, as well as the proportion of top-quality day 3 cleavage stage embryos generated (with total number of day 3 embryos formed used as denominator) between the 2 groups. This serves as a more accurate marker of any potential difference in the quality of oocytes and embryos between the two groups, as shown in

Table 3.

The results revealed that while there was no difference in the fertilization rates between the two groups, greater proportion of top-quality cleavage stage embryos were generated in patients who had received GnRH antagonist injections from day 1 of stimulation (Group 1).

3.3. Clinical Outcome Parameters

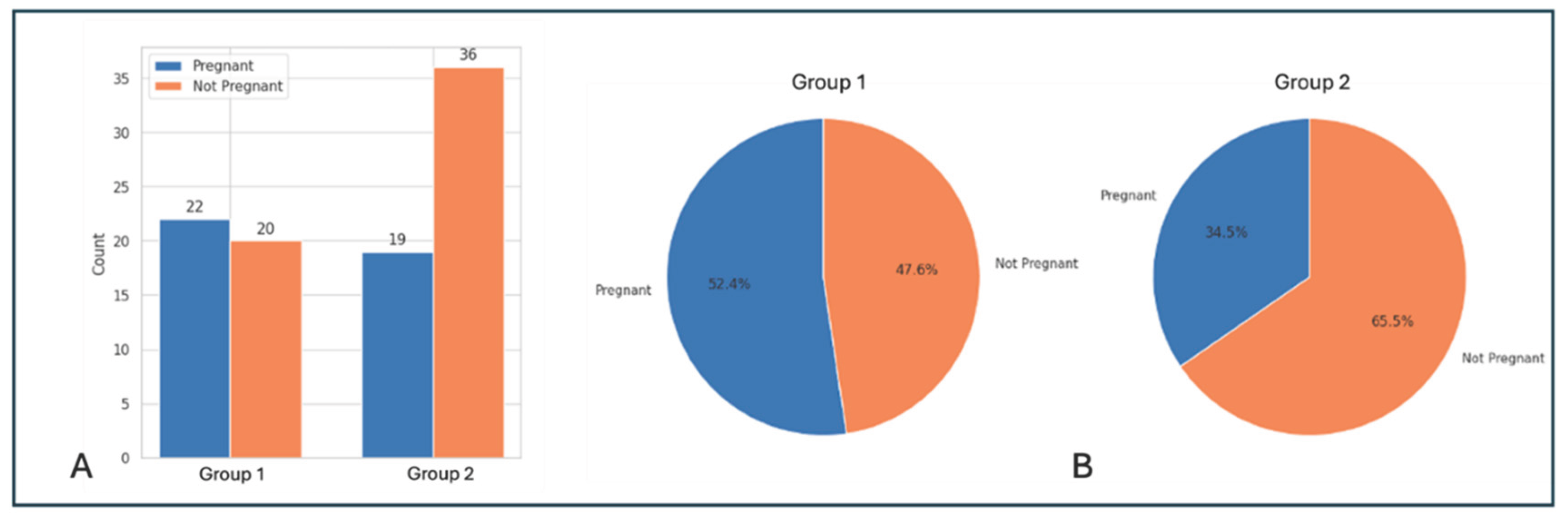

Finally, we compared cumulative pregnancy outcomes over a total of 3 transfer cycles between the 2 groups (shown in

Table 4). In Group 1 (antagonists from day 1), a total of 42 patients had a total of 50 embryo transfers over a maximum of 3 transfer cycles (maximum of 1 fresh and 2 frozen cycles), with a total of 91 embryos having been transferred (mean number of embryos transferred per patient: 2.02 ± 0.92). In Group 2 (antagonists from day 5 or day 6), 55 patients had 68 embryo transfers (maximum of 1 fresh and 2 frozen cycles) with 124 embryos having been transferred in total (mean of 2.27 ± 1.06 embryos transferred per patient). There was no significant difference between the mean number of embryos transferred between the 2 groups (p > 0.05).

Cumulative clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) per embryo transfer (Group 1 vs. Group 2: 44% vs. 27.9%), as well as CPR per initiated stimulation cycle (52.4% vs. 34.5%) were higher for Group 1, although the differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.07). However, there was a clear trend of better pregnancy outcome in the group with GnRH antagonist administration from Day 1 of IVF stimulation. Pregnancy outcomes are summarized in

Table 4 and represented graphically in

Figure 4.

Table 4.

Embryo transfer and clinical pregnancy data.

Table 4.

Embryo transfer and clinical pregnancy data.

| Study Groups |

No. of patients who had embryo transfer/s |

No. of embryo transfer (ET) events |

No. of embryos transferred |

No. of pregnancies |

Cumulative Clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) per stimulation cycle |

Clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) per ET |

| Group 1 (Day 1 antagonist) |

42 |

50 |

91 |

22 |

52.4% |

44% |

| Group 2 (Day 5/day 6 antagonist) |

55 |

68 |

124 |

19 |

34.5% |

27.9% |

| Statistical significance |

|

|

NS

p > 0.05 |

|

NS

p = 0.07 |

NS

p = 0.07 |

Figure 4.

Comparison of pregnancy outcomes between Group 1 (Day 1 Antagonist) and Group 2 (Day 5/6 Antagonist). (A) Bar graph showing number of patients who became pregnant (blue) vs. number who did not get pregnant (orange), (B) Pie chart showing proportions of patients (Clinical pregnancy rate per stimulation cycle) who became pregnant (blue) vs. those who did not (orange) in the 2 groups.

Figure 4.

Comparison of pregnancy outcomes between Group 1 (Day 1 Antagonist) and Group 2 (Day 5/6 Antagonist). (A) Bar graph showing number of patients who became pregnant (blue) vs. number who did not get pregnant (orange), (B) Pie chart showing proportions of patients (Clinical pregnancy rate per stimulation cycle) who became pregnant (blue) vs. those who did not (orange) in the 2 groups.

4. Discussion

4.1. Number of COCs Retrieved and Oocyte Fertilization Rate

Baseline parameters such as patient age, BMI, AMH and TSH levels were found to be comparable between Group 1 (Antagonist from day 1 of stimulation) and Group 2 (Antagonist from day 5 or 6 of stimulation). However, data analysis revealed that the number of oocytes (COCs) retrieved was significantly higher in the early antagonist group (Group 1 vs. Group 2: 11.47 ± 4.37 vs. 8.95 ± 3.88, p < 0.01). However, both the groups showed almost identical fertilization rates (Group 1 vs. Group 2: 70.9% vs. 70.1%, p > 0.05).

Interestingly, a recent 2024 retrospective study that was designed to solely compare oocyte yield between GnRH antagonist cycles with an added 3-day pretreatment course with GnRH antagonist in the early follicular phase (“pretreatment cycle”), with a standard flexible antagonist protocol (“standard cycle”), also reported significantly higher number of COCs retrieved in the pretreatment group [

29].

It is well documented that ovarian follicles in PCOS patients are relatively refractory to the stimulatory effect of FSH. Follicular resistance to FSH signaling may be partly caused by intra-ovarian hyperandrogenism as well as elevated AMH levels. LH is known to have a stimulatory effect both on AMH secretion as well as on androgen synthesis from ovarian theca cells, acting synergistically with insulin. Indeed, serum LH levels are characteristically raised in a subset of PCOS patients, who often demonstrate altered LH pulse amplitude as well as pulse frequency.

Thus, GnRH antagonist mediated suppression of LH overexpression in the early follicular phase of ovarian stimulation in Group 1 patients may have led to correction of AMH and androgen levels downstream in the HPO axis, ultimately resulting in improved ovarian follicular sensitivity to FSH and superior recruitment of pre-antral follicles. Unfortunately, due to the retrospective nature of this study, serum LH levels at various time points over the course of OS were not available uniformly across the 2 cohorts. This is also due to the fact that this was an unfunded study and many of our patients cannot afford repeated serum hormone measurements, if not strictly clinically required.

4.2. Proportion of Top-Quality Embryos Achieved

Our data also shows that proportion of top-quality day 3 cleavage stage embryos obtained was significantly higher in the Day 1 antagonist group compared to the flexible day 5/day 6 antagonist group (Group 1 vs. Group 2: 77.5% vs. 63.4%, p < 0.01). Since we had excluded all patients suffering from male factor infertility from this study and baseline parameters (age, BMI, AMH, TSH) were similar between the two groups, the only explanation for this finding appears to be one that implicates a difference in oocyte quality between the two groups.

It has been documented that PCOS patients have a higher risk of infertility even when ovulation is present [

30]. Moreover, it has been suggested PCOS patients have relatively poor oocyte quality which may be responsible for poorer outcomes in IVF cycles [

31]. Given that elevated serum LH levels are a characteristic feature in many PCOS patients, and the fact that the only variable intervention in our study was early administration of GnRH antagonist from day 1 of stimulation in the study group, it is worthwhile to consider the possible impact of LH on oocyte quality, in the light of our findings.

Elevated, premature serum LH levels in flexible antagonist IVF cycles have been found to have a detrimental impact on oocyte and embryo quality [

32]. This is particularly true in the case of elevated serum LH levels early in the follicular phase, which has been proposed to result in early resumption of meiosis and premature ovulation [

33]. Moreover, it has been shown that in GnRH antagonist IVF cycles in women with PCOS, patients with higher basal serum LH levels exhibit an increased incidence of early LH elevation > 10 U/L [

33]. Furthermore, in a remarkably granular analysis, this study demonstrated that proportion of top-quality embryos obtained was higher when the ratio of serum LH on day of hCG administration (h-LH) to the basal serum LH value (b-LH) was greater than 1 (h-LH/b-LH > 1).

Thus, the available evidence seems to suggest that adequate suppression of basal LH with GnRH antagonists early from day 1 in the follicular phase of ovarian stimulation likely optimizes the meiotic pathway, improves oocyte quality, and leads to the generation of a higher proportion of top quality embryos, compared to flexible initiation of GnRH antagonists from day 5 or day 6 of ovarian stimulation.

4.3. Cumulative Clinical Pregnancy Rate

Cumulative clinical pregnancy rates were analyzed over a maximum of 3 different embryo transfer cycles including one fresh transfer cycle (in cases where a fresh transfer was done), and up to 2 frozen transfer cycles. The mean number of embryos transferred was similar between the 2 groups (Group A vs. Group B: 2.02 ± 0.92 vs. 2.27 ± 1.06, p > 0.5). Cumulative clinical pregnancy rate per embryo transfer (Group A vs. Group B: 44% vs. 27.9%, p = 0.07), and cumulative clinical pregnancy rate per initiated cycle (Group A vs. Group B: 52.4% vs. 34.5%, p = 0.07), showed higher trends in the Day 1 antagonist group, but fell short of statistical significance.

This finding is similar to the results of the 3-arm study previously cited (GnRH agonist vs. standard GnRH antagonist vs. early GnRH antagonist) which was designed to assess any differences between the 3 groups in terms of the number of oocytes retrieved, incidence of OHSS, and clinical pregnancy rate. The authors reported that although the number of oocytes retrieved was similar between the 3 groups, incidence of OHSS was lower and clinical pregnancy rate was higher in the early antagonist group, although these differences did not achieve statistical significance [

26].

Higher cumulative CPR has been reported in patients with better suppression of serum LH levels on day of hCG [

33]. Recent research has also implicated the combined impact of elevated serum LH, hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance on the impairment of endometrial receptivity in PCOS patients [

34]. We can only speculate that the trend of higher cumulative CPR in our day 1 antagonist group was also secondary to earlier and more effective suppression of serum LH throughout the follicular phase of ovarian stimulation, leading to a beneficial impact on oocyte developmental potential, and endometrial receptivity.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, optimizing controlled ovarian stimulation is essential in IVF cycles to maximize oocyte yield and quality, while at the same time minimize the risk of OHSS. This is particularly important in PCOS patients. Numerous studies have shown that GnRH antagonist protocols offer the best combination of cycle flexibility and lower risk of OHSS, while offering acceptable IVF outcomes, compared with traditional long agonist protocols. However, there is little data comparing IVF outcomes with antagonist administration from day 1 of stimulation versus standard flexible antagonist.

In this paper we report significantly higher oocyte yield as well as generation of top-quality embryos with administration of antagonists from day 1 of IVF stimulation compared to standard flexible antagonists. We have also documented higher cumulative pregnancy rates with this strategy over 3 embryo transfer cycles, both fresh and frozen, although this result just failed to achieve statistical significance. In the light of old and recent research which establishes/proposes the detrimental impact of early, continued, elevated serum LH levels on both oocyte quality as well as endometrial receptivity in PCOS patients, we speculate that these may be the underlying mechanisms that explain our findings. We propose that early initiation of GnRH antagonists from day 1 of IVF stimulation for PCOS patients may help to optimize IVF outcomes.

6. Limitations and Future Work

Our study is associated with certain limitations such as relatively small sample size, retrospective design and its limitations, as well as lack of funding. Larger, randomized, prospective studies should be conducted to replicate our findings and further optimize care of PCOS patients desiring conception by IVF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.D. and B.G.D.; Methodology, B.G.D.; Software, C.C.; Formal Analysis, B.G.D., C.C.; Acquisition, Interpretation, Investigation, B.G.D., R.C.; Resources, S.G.D. and R.C.; Data Curation, B.G.D.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, B.G.D.; Writing—Review & Editing, S.G.D., B.G.D., R.C., C.C.; Visualization, B.G.D. and C.C.; Supervision, S.G.D., R.C.; Project Administration, B.G.D. All authors approved the final version for publication. All authors agree to be personally accountable for their own contributions and for ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and documented in the literature.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethics Committee) of Institute of Reproductive Medicine (project code IRM/IEC/RC-IHP-14/2024) on 07/04/2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper, including unlimited permission for publication in all formats (including print, electronic, and online), in sublicensed and reprinted versions (including translations and derived works), and in other works and products under open access license.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms Richismita Hazra for data recording, curation, and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of Interest.

Abbreviations

| GnRH |

Gonadotropin releasing hormone |

| PCOS |

Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| IVF |

in-vitro fertilization |

| FSH |

follicle stimulating hormone |

| LH |

Luteinizing hormone |

| PCOM |

Polycystic ovary morphology |

| AEPCOS |

Androgen Excess and PCOS Society |

| AMH |

anti-mullerian hormone |

| HPO |

hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian |

| OS |

ovarian stimulation |

| OHSS |

ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome |

| FET |

frozen embryo transfer |

| 2PN |

2 Pronuclear |

| ASRM |

American Society for Reproductive Medicine |

| GDIFR |

Institute for Fertility Research |

| IRM |

Institute of Reproductive Medicine |

| ICSI |

Intra-cytoplasmic Sperm Injection |

| CPR |

clinical pregnancy rate |

| COC |

cumulus-oocyte complexes |

| IU |

International units |

| E2 |

Estradiol |

| TVS |

transvaginal sonography |

| r-hCG |

recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin |

| HPI |

hours post insemination |

| ET |

Embryo transfer |

| HRT |

hormone replacement therapy |

| MR |

Miscarriage rates |

| OPR |

ongoing pregnancy rates |

| BMI |

body mass index |

| TSH |

thyroid stimulating hormone |

References

- Balen, A.H.; Morley, L.C.; Misso, M.; Franks, S.; Legro, R.S.; Wijeyaratne, C.N.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Fauser, B.C.; Norman, R.J.; Teede, H. The management of anovulatory infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: an analysis of the evidence to support the development of global WHO guidance. Human reproduction update 2016, 22, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, W.A.; Moore, V.M.; Willson, K.J.; Phillips, D.I.; Norman, R.J.; Davies, M.J. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Human reproduction 2010, 25, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Human reproduction 2004, 19, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz, R.; Carmina, E.; Dewailly, D.; Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F.; Futterweit, W.; Janssen, O.E.; Legro, R.S.; Norman, R.J.; Taylor, A.E.; Witchel, S.F.; Task Force on the Phenotype of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome of The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertility and sterility 2009, 91, 456–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmina, E.; Lobo, R.A. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): arguably the most common endocrinopathy is associated with significant morbidity in women. The journal of clinical endocrinology & metabolism 1999, 84, 1897–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peigné, M.; Dewailly, D. Long term complications of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). In Annales d’endocrinologie; Elsevier Masson, September 2014; Volume 75, No. 4; pp. 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidis, A.; Dinas, K. Long term health consequences of polycystic ovarian syndrome: a review analysis. Hippokratia 2009, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Azziz, R. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2018, 132, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, A.; Peigné, M.; Grynberg, M.; Arouche, N.; Taieb, J.; Hesters, L.; Gonzalès, J.; Picard, J.Y.; Dewailly, D.; Fanchin, R.; Catteau-Jonard, S.; di Clemente, N. Loss of LH-induced down-regulation of anti-Müllerian hormone receptor expression may contribute to anovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Human reproduction 2013, 28, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, S.; Vanky, E.; Fleming, R. Anti-Müllerian hormone concentrations in androgen-suppressed women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction 2009, 24, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, R.; Seifer, D.B.; Khanimov, M.; Malter, H.E.; Grazi, R.V.; Leader, B. Characterization of women with elevated antimüllerian hormone levels (AMH): correlation of AMH with polycystic ovarian syndrome phenotypes and assisted reproductive technology outcomes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2014, 211, 59.e1-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, J.E.; Powers, L.P.; Matt, D.W.; Steingold, K.A.; Plymate, S.R.; Rittmaster, R.S.; Clore, J.N.; Blackard, W.G. A direct effect of hyperinsulinemia on serum sex hormone-binding globulin levels in obese women with the polycystic ovary syndrome. The Journal of clinical endocrinology & metabolism 1991, 72, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, W.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Q. Is a GnRH antagonist protocol better in PCOS patients? A meta-analysis of RCTs. PloS one 2014, 9, e91796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, C.; Chang, S. Effectiveness of GnRH antagonist in the treatment of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing IVF: a systematic review and meta analysis. Gynecological Endocrinology 2013, 29, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofriescu, A.; Bors, A.; Luca, A.; Holicov, M.; Onofriescu, M.; Vulpoi, C. GnRH antagonist IVF protocol in PCOS. Current Health Sciences Journal 2013, 39, 20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tehraninejad, E.S.; Nasiri, R.; Rashidi, B.; Haghollahi, F.; Ataie, M. Comparison of GnRH antagonist with long GnRH agonist protocol after OCP pretreatment in PCOs patients. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2010, 282, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haydardedeoglu, B.; Kilicdag, E.B.; Parlakgumus, A.H.; Zeyneloglu, H.B. IVF/ICSI outcomes of the OCP plus GnRH agonist protocol versus the OCP plus GnRH antagonist fixed protocol in women with PCOS: a randomized trial. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 2012, 286, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.A.; Aleyasin, A.; Saeedi, H.; Mahdavi, A. Comparison of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists in assisted reproduction cycles of polycystic ovarian syndrome patients. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2010, 36, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkić, M.; Popović, J.; Kopitović, V.; Bjelica, A.; Živadinović, R.; Pop-Trajković, S. Flexible GnRH antagonist protocol vs. long GnRH agonist protocol in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome treated for IVF: comparison of clinical outcome and embryo quality. Ginekologia polska 2016, 87, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behery, M.A.; Hasan, E.A.; Ali, E.A.; Eltabakh, A.A. Comparative study between agonist and antagonist protocols in PCOS patients undergoing ICSI: a cross-sectional study. Middle East Fertility Society Journal 2020, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivennes, F.; Cunha-Filho, J.S.; Fanchin, R.; Bouchard, P.; Frydman, R. The use of GnRH antagonists in ovarian stimulation. Human reproduction update 2002, 8, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesinger, G.; Diedrich, K.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Kolibianakis, E.M. GnRH-antagonists in ovarian stimulation for IVF in patients with poor response to gonadotrophins, polycystic ovary syndrome, and risk of ovarian hyperstimulation: a meta-analysis. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 2006, 13, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadoura, S.; Alhalabi, M.; Nattouf, A.H. Conventional GnRH antagonist protocols versus long GnRH agonist protocol in IVF/ICSI cycles of polycystic ovary syndrome women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainas, T.G.; Sfontouris, I.A.; Zorzovilis, I.Z.; Petsas, G.K.; Lainas, G.T.; Alexopoulou, E.; Kolibianakis, E.M. Flexible GnRH antagonist protocol versus GnRH agonist long protocol in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome treated for IVF: a prospective randomised controlled trial (RCT). Human reproduction 2010, 25, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainas, T.G.; Petsas, G.K.; Zorzovilis, I.Z.; Iliadis, G.S.; Lainas, G.T.; Cazlaris, H.E.; Kolibianakis, E.M. Initiation of GnRH antagonist on Day 1 of stimulation as compared to the long agonist protocol in PCOS patients. A randomized controlled trial: effect on hormonal levels and follicular development. Human Reproduction 2007, 22, 1540–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.J.; Park, K.E.; Choi, Y.M.; Kim, H.O.; Choi, D.H.; Lee, W.S.; Cho, J.H. Early gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist protocol in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A preliminary randomized trial. Clinical and experimental reproductive medicine 2018, 45, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastidar, S.G. A novel ovarian stimulation protocol with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist and follicle stimulating hormone from cycle day 1 in IVF in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Fertility and Sterility 2008, 90, S362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpha scientists in reproductive medicine and ESHRE special interest group of embryology. The Istanbul consensus workshop on embryo assessment: proceedings of an expert meeting. Hum Reprod 2011, 26, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Guardo, F.; De Rijdt, S.; Racca, A.; Drakopoulos, P.; Mackens, S.; Strypstein, L.; Tournaye, H.; De Vos, M.; Blockeel, C. Impact of GnRH antagonist pretreatment on oocyte yield after ovarian stimulation: A retrospective analysis. Plos one 2024, 19, e0308666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomba, S. Is fertility reduced in ovulatory women with polycystic ovary syndrome? An opinion paper. Human Reproduction 2021, 36, 2421–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomba, S.; Daolio, J.; La Sala, G.B. Oocyte competence in women with polycysticovary syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab.

- Dovey, S.; McIntyre, K.; Jacobson, D.; Catov, J.; Wakim, A. Is a premature rise in luteinizing hormone in the absence of increased progesterone levels detrimental to pregnancy outcome in GnRH antagonist in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertility and sterility 2011, 96, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, J.; Qu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q. Does serum LH level influence IVF outcomes in women with PCOS undergoing GnRH-antagonist stimulation: a novel indicator. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.X.; Li, X.L. The disorders of endometrial receptivity in PCOS and its mechanisms. Reproductive Sciences 2022, 29, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).