1. Introduction

With the rapid increase in global population and technological advancements, the demand for geological resources has notably increased [

1]. Among them, the demand for lithium usage increased significantly over the last years. The trend is expected to continue in the future due to the primary reasons that lithium is helping to promote renewable energy technology, which aims to achieve a carbon-neutral society. Additionally, to date, no battery storage system has been invented that performs better than lithium batteries, and lithium has various uses beyond battery storage systems [

2]. Lithium is a silver metal, also called “white petroleum” [

3], only able to be found in the form of mineral compounds, usually in igneous rocks, brine deposits underground, lithium-rich clay minerals and seawater [

4]. The extraction of lithium from the above sources involves various stages, and with the expansion of the industry, parallel issues such as waste generation, energy requirements, environmental risks, and health risks are also becoming increasingly prominent. The implementation of sustainable solutions for mining-related issues and challenges is a necessary course of action. Currently, the reusing and recycling of mining waste is a widely studied topic in worldwide [

5]. Lithium slag (LS), a by-product generated during lithium carbonate production via the sulphuric acid roasting and water leaching of spodumene ore [

6,

7]. Over the past few years, the LS generation has increased, accompanied by an increase in challenges associated with it, such as land resource occupation and environmental pollution, highlighting the need for a sustainable solution [

8]. For each ton of lithium carbonate produced, an estimated 9 to 10 tons of LS are generated, leading to substantial waste accumulation, particularly in lithium-rich countries such as Australia [

6,

7]. The numbers demonstrate how important recycling or reuse of the lithium slag is for sustainability. However, studies have revealed that around 90% of LS treatment procedures dispose of the LS to the ground, wasting the reusable material and leading to environmental pollution. Further, previous studies identified the LS as high pozzolanic material [

9]. The chemical composition of LS—comprising high levels of SiO₂, Al₂O₃, and CaO—resembles that of traditional SCMs such as fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag [

6,

7].

Concrete is the most widely used construction material globally; Portland cement is the primary component of concrete. The strength, workability and durability of concrete mainly depend on the cementitious binding material used. However, cement production is associated with considerable environmental concerns. Notably, the cement manufacturing process contributes approximately 8% of global anthropogenic CO₂ emissions, primarily due to calcination and high energy consumption [

10]. Results of that, researchers actively exploring substitute materials for cement and, accordingly, supplementary cementitious material (SCM) have gained widespread attention [

11]. The previous studies confirm that using different types of SCMs tends to enhance the fresh and mechanical properties, as well as the durability of the structure [

12]. The pozzolanic activity of SCM can react with calcium hydrate in cement and produce extra C-S-H, which reduces porosity, making the structure less permeable and enhancing the durability of the structure [

13]. Currently, fly ash is the most commonly used SCM worldwide, which is a by-product of burning coal-fired power plants. However, coal-fired power plants are being phased out, which causes a decline in the availability of fly ash, and the situation has encouraged researchers to find alternative SCM [

14,

15]. Most of the identified SCMs are by-products of different industries. Among those substitutes, LS emerged as a promising material, although the performance levels are still under investigation. Emerging studies have highlighted the role of LS in hydration reactions, demonstrating its various benefits [

16]. Recent investigations have demonstrated that LS can enhance the performance of cementitious systems by accelerating early hydration, improving compressive strength, and improving durability parameters, such as reducing porosity and increasing resistance to chloride ion penetration [

6]. Furthermore, the utilisation of LS contributes to lowering both the embodied carbon footprint and raw material costs, given its availability as a low-value industrial waste. However, concerns persist regarding the elevated SO₃ content in LS, which may trigger sulphate-induced expansion if not properly managed through careful mix design [

6].

In response to the dual challenges—carbon emissions from cement production and the environmental impact of Lithium slag—circular economy approaches have gained significant interest. Among these, the valorisation of industrial by-products as supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) represents a promising strategy for promoting sustainable construction practices [

17,

18]. Such approaches not only divert waste from landfills but also reduce reliance on energy-intensive clinker production. This dual functionality positions SCMs as essential contributors to both emissions’ mitigation and resource efficiency goals.

1.1. Objective of the Study

This review provides a comprehensive examination of the mechanical, microstructural, and durability performance of LS-incorporated concrete. It further evaluates the environmental and economic implications based on life cycle and techno-economic assessments. In addition, this study discusses key implementation barriers, including the lack of long-term validation, standardization, and regulatory guidance. By consolidating current research findings, the review aims to advance the technical understanding and practical adoption of LS as a sustainable SCM aligned with circular construction principles [

6,

7].

In nations such as Australia, where infrastructure growth is projected to accelerate in line with national commitments to achieving net-zero emissions, there is a growing demand for sustainable construction solutions that align with both domestic climate policies and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [

10]. This study addresses these critical imperatives by exploring lithium slag (LS), a by-product of spodumene-based lithium extraction in regions such as Greenbushes and Kwinana, Western Australia, as a viable supplementary cementitious material (SCM) for concrete. Currently underutilised, LS is often stockpiled or landfilled, posing environmental risks such as heavy metal leaching and land degradation [

19,

20]. However, its high content of reactive silica and alumina indicates a strong pozzolanic potential, making it a promising candidate for partial replacement of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) in concrete formulations [

7,

21].

1.2. Methodology of the Study

1.2.1. Literature Search and Study Selection

The study adopts a structured literature review methodology to evaluate the mechanical and durability performance of lithium slag (LS)-modified concrete. The review synthesises findings from a diverse range of empirical studies to assess LS’s viability as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) and derive performance indicators across varied research contexts. Relevant literature was identified through comprehensive searches of Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, encompassing publications available from 2017 up to 2025. The search utilised specific keywords and Boolean operators to locate studies related to LS in cementitious systems. Terms such as “lithium slag concrete”, “mining waste SCM”, “LS compressive strength”, “LS durability”, and “pozzolanic reactivity of lithium slag” were used. Filters were applied by publication type (research articles), language (English), and date range to ensure academic relevance and rigour.

Studies were included based on criteria ensuring methodological consistency and relevance. Eligible studies reported empirical or field-based evaluations involving LS as a cement replacement or additive. In particular, studies were required to include quantitative data on compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, or flexural strength. Durability performance under aggressive exposures, such as sulphate attack, acid exposure, chloride ingress, shrinkage, or freeze–thaw cycling, was a necessary inclusion. Where available, microstructural analyses using material characterisation techniques were also considered.

Key experimental parameters were systematically extracted from each selected study to enable consistent comparison and synthesis. These parameters included the lithium slag (LS) cement replacement levels (e.g., 10%, 15% ,20%, 30%), the type of concrete used (e.g., normal-strength concrete, high-performance concrete, or recycled aggregate concrete), and the curing durations assessed (typically 7, 28, 56, and 90 days). Additionally, outcomes related to fresh properties, mechanical strength, and durability performance were compiled.

1.2.2. Review Methodology

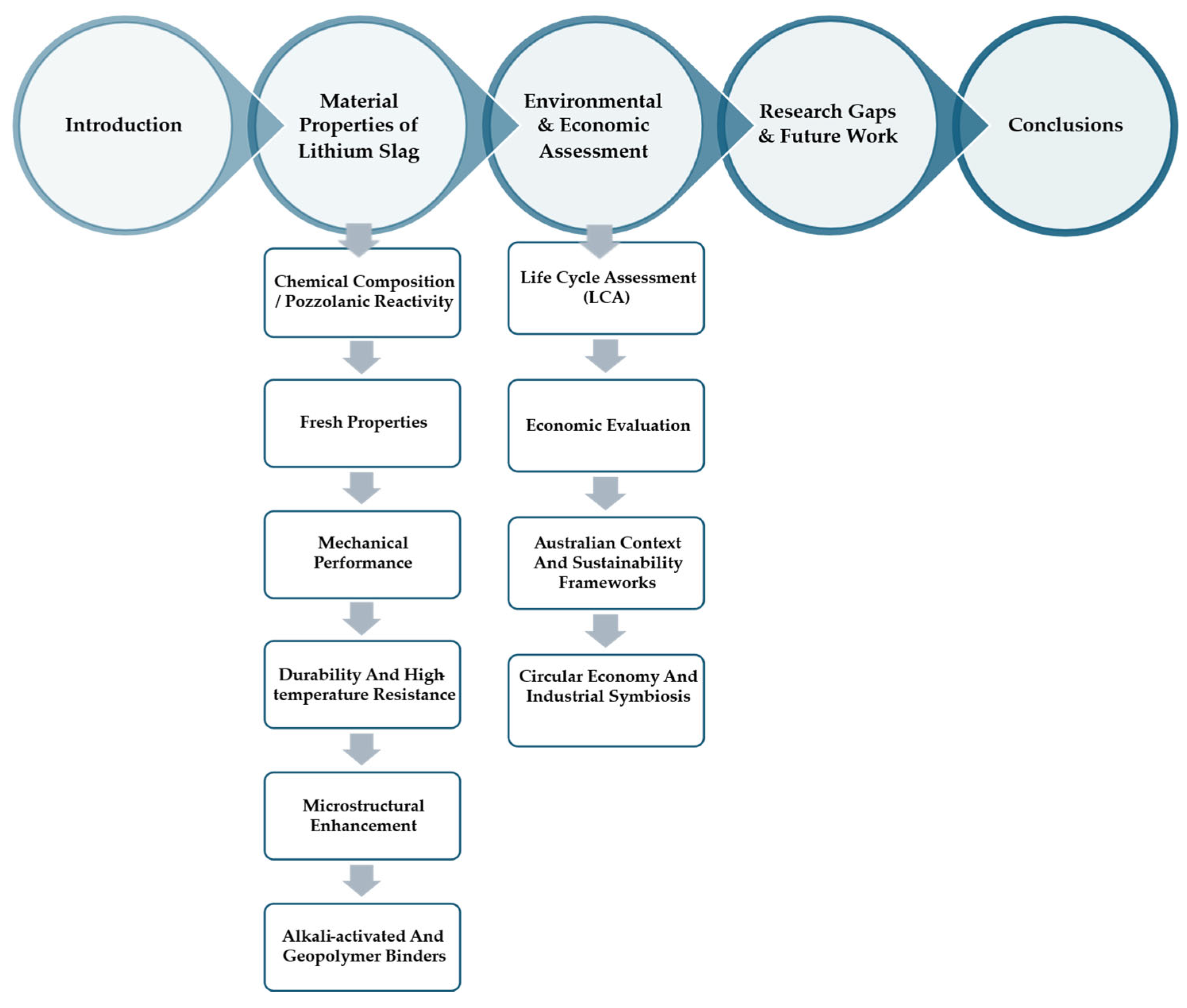

As shown in

Figure 1, the review begins by reviewing the material properties of the lithium slag. Under this, the study first reviews the chemical composition and pozzolanic reactivity of the LS, highlighting why it qualifies as a sustainable high-performance SCM. The study then reviews the fresh properties of LS-blended concrete, including workability, setting times, and air content, to ensure compliance with placement and performance standards. It then evaluates mechanical performance through measurements of compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths at 7, 28, and 90 days to establish structural reliability. Durability analyses are carefully conducted using the details of previous studies done under aggressive environmental conditions such as sulphate exposure, acid immersion, freeze–thaw cycles, and elevated temperatures to predict long-term performance. The discussion then transition to the microstructural development of LS-blended concrete is investigated based on previously published data of scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), and backscattered electron (BSE) imaging, with a focus on hydration products, pore structure, and the interfacial transition zone (ITZ). Following this section, the study focuses on environmental and economic assessment. A comprehensive review was conducted in life cycle assessment (LCA) which need to be conducted in accordance with ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 protocols, utilising data from Ecoinvent and GaBi to quantify key environmental impacts such as global warming potential and embodied energy. An economic feasibility analysis is also carried out, comparing LS to conventional SCMs like fly ash and slag by considering material sourcing, processing, transport, and projected service life costs.

Finally, the study explores the synergistic integration of LS with other industrial by-products, including copper slag, iron ore tailings, recycled aggregates, and phosphorus slag. It also evaluates the applicability of LS in alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete systems to expand its utilisation in advanced sustainable cement technologies [

18,

23,

36].

Collectively, these objectives are designed to generate robust, interdisciplinary evidence supporting the validation and large-scale adoption of LS as a low-carbon SCM. This effort aligns with Australia's broader ambitions for circular construction and the realisation of sustainable infrastructure systems.

1.3. Significance of the Study

The significance of this study lies in several interrelated dimensions. Replacing OPC with LS lowers clinker demand and reduces the carbon intensity of concrete. Life cycle as-sessment (LCA) studies indicate that LS-based concrete mixes can achieve CO₂ emission reductions of 20–30% per cubic meter, supporting Australia’s low-carbon infrastructure targets [

6,

22]. Regarding waste valorisation and the circular economy, the incorporation of LS into concrete exemplifies circular economy principles by converting high-volume mining waste into a valuable construction input. This transformation fosters industrial symbiosis between the mining and construction sectors, conserves natural resources, and reduces reliance on landfilling [

21,

23].

Technically, LS-blended concrete has demonstrated the ability to match or even exceed the mechanical and durability performance of traditional OPC mixes. Enhanced resistance to sulphate attack, acid corrosion, and elevated temperatures makes LS-concrete particularly suitable for aggressive environmental conditions and long-service-life infra-structure [

24,

25,

26]. On the regulatory front, this study contributes essential data that may support the future integration of LS into Australian structural design standards such as AS 3600, as well as sustainability frameworks like Green Star. Such regulatory recognition would likely accelerate the adoption of LS-based concrete across the industry [

27,

28].

Economically, LS represents a promising alternative to coal fly ash, whose availability is declining due to the progressive decommissioning of coal-fired power stations. As a regionally abundant by-product, LS offers potential cost advantages in sourcing and processing. Additionally, its improved durability may lower long-term maintenance expenditures and extend the lifespan of concrete infrastructure [

23,

29].

2. Material Properties of Lithium Slag

2.1. Chemical Composition and Pozzolanic Reactivity

Lithium slag (LS) is a finely powdered industrial residue that results from the processing of spodumene ore during lithium carbonate production. It has been characterised by high concentrations of reactive silica (SiO₂) and alumina (Al₂O₃), along with a relatively low calcium oxide (CaO) content, rendering it chemically comparable to Class F fly ash [

6]. Slags derived from spodumene and lepidolite—and indicated that residual lithium and sulphate contents significantly influence reactivity and environmental performance.

The study conducted by [

20] reported that LS consists of approximately 77% combined SiO₂, Al₂O₃, and Fe₂O₃, with around 31.6% amorphous content and a loss on ignition of 7–8%. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis revealed crystalline phases such as quartz, albite, anorthite, bassanite (CaSO₄·0.5H₂O), and β-spodumene. Bassanite, in particular, reacts rapidly with calcium and aluminium ions to form ettringite (AFt), contributing to early-age strength. X-ray diffraction (XRD) detects decreased CH and increased hydration products, while thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) reveals higher bound water and CH depletion, reflecting enhanced hydration kinetics [

19,

25]. The chemical composition of Lithium slag can vary depending on the material source and technology used in production. The investigation undertaken by [

30] in China (Jiangxi, China), the LS sample revealed that lithium slag primarily comprises 50.25% SiO2, 22.75% of Al2O3 and 11.27% of Na2O.

Further,[

20] conducted the Ion dissolution tests, which demonstrated that LS releases reactive species up to 4.8 times faster than Class F fly ash, supporting its accelerated early-stage reactivity and classification as a viable supplementary cementitious material (SCM) under ASTM C618 [

20,

31].

According to the study [

32], the Backscattered Electron (BSE) of SEM revealed that LS comprises 39.78-42.65% of amorphous aluminosilicate, providing evidence of the pozzolanic reactivity of LS. LS’s high pozzolanic reactivity qualifies it as a sustainable, high-performance SCM due to its ability to consume calcium hydroxide and generate durable hydrates such as C–S–H and AFt.

Table 1 compares the oxide compositions and performance indices of LS, Class F fly ash, and ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) to contextualize its re-activity profile.

Table 1.

Comparison of Oxide Composition and Reactivity Indices of Lithium Slag (LS), Class F Fly Ash, and GGBFS [

6,

7,

8,

20,

21,

29,

31]

Table 1.

Comparison of Oxide Composition and Reactivity Indices of Lithium Slag (LS), Class F Fly Ash, and GGBFS [

6,

7,

8,

20,

21,

29,

31]

| Parameter |

Lithium Slag (LS) |

Class F Fly Ash |

GGBFS |

| SiO₂ (%) |

40–55 |

45–60 |

30–38 |

| Al₂O₃ (%) |

10–20 |

15–30 |

10–18 |

| CaO (%) |

5–18 |

<10 |

35–45 |

| Fe₂O₃ (%) |

4–10 |

5–10 |

<2 |

| SO₃ (%) |

2–6 (variable) |

<3 |

<3 |

| Amorphous Content (%) |

~30–35 |

40–60 |

85–95 |

| Strength Activity Index |

85–95% at 28 days |

70–90% |

>100% |

| Ion Dissolution Rate |

Up to 4.8× > Fly Ash |

Moderate |

High |

| Pozzolanic Reactivity |

Moderate to High |

Moderate |

High (Latent Hydraulic) |

| Primary Hydration Products |

C–S–H, AFt, AFm |

C–S–H |

C–S–H, C–A–S–H |

To further validate the LS’s reactivity, multiple standardised tests have been used in various studies. According to [

28], the Strength Activity Index (SAI) shows that 40% LS replacement achieves 93% of the control mix's compressive strength at 28 days . Frattini tests confirmed significant calcium hydroxide (CH) consumption, and R3 isothermal calorimetry showed moderate to high heat evolution indicative of active pozzolanic reactions [

21]. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) highlights a denser interfacial transition zone (ITZ) and refined pore structure in LS-blended systems, contributing to improved durability. In the unsaturated lime test, EDTA titration was used to quantify calcium consumption by LS [

20], applying Equation (1). These complementary methods provide a robust assessment of both chemical reactivity and mechanical performance potential, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of LS as a pozzolanic material. Collectively, they capture short-term kinetic responses and long-term mineralogical transformations essential to SCM classification.

where:

M₁ is the molarity of the EDTA solution (mol·L⁻¹),

V₁ is the volume of EDTA used in the titration (mL),

f₁ is the dilution factor (dimensionless),

V₂ is the total volume of the test solution (mL), and

56.08 is the molar mass of CaO (g·mol⁻¹).

The decline in residual CaO confirms that LS's aluminosilicate phases react effectively with CH, accelerating secondary hydrate formation. Mechanistically, LS’s amorphous SiO₂ and Al₂O₃ react with portlandite to form C–S–H, AFt, and later Alumino Ferrite monosulfate (AFm) phases. Cement pastes with 10–30% LS showed reduced CH content over time, affirming sustained pozzolanic activity [

26,

31].

Mechanical activation techniques, including grinding, enhance LS reactivity by in-creasing the release of Si, Al, and lithium ions [

6]. While thermal and alkali activation are under investigation, untreated LS already performs optimally at 20–40% replacement, balancing strength, hydration rate, and workability [

26].

Accordingly, standardised tests such as SAI, Frattini, XRD, TGA, R3 calorimetry, and EDTA titration confirm LS’s moderate to high pozzolanic reactivity, and

Table 2 illustrates the key findings of the performance insights. These findings collectively confirm that LS exhibits high pozzolanic reactivity, enabling its use as a partial cement replacement in both OPC and geopolymer binder systems. The synergy between chemical composition and physical fineness allows LS to accelerate early hydration while also contributing to long-term strength development and durability.

2.2. Fresh Properties of LS concrete

This section discusses the influence of lithium slag (LS) on the fresh-state properties of concrete, including workability, setting time, and air content. These parameters are essential for ensuring satisfactory placement, compaction, and early-age performance of LS-blended concrete mixtures.

2.2.1. Workability

Incorporating lithium slag into concrete affects the workability of fresh mixtures due to its physical characteristics and chemical reactivity. LS typically exhibits a finer particle size distribution, and a higher specific surface area compared to fly ash, along with a more angular particle morphology resulting from the grinding of slag particles [

6]. These attributes generally increase water demand and reduce flowability, particularly at higher replacement levels. Increasing LS content reduces slump and shortens setting time [

20]. This decline in workability is primarily attributed to the material’s fineness and the presence of soluble salts, which accelerate the early stages of cement hydration.

However, the effect of LS on workability is system dependent. In alkali-activated binder systems, LS addition has been shown to decrease yield stress and enhance initial flowability, suggesting improved dispersion in high-pH environments [

27]. In ordinary Portland cement (OPC) systems, moderate replacement levels of LS—typically up to 30%—can maintain acceptable workability without major mix modifications. Concrete mixtures designed with 20–60% LS replacement and targeting a slump of 125 ± 25 mm were able to achieve this range, indicating the feasibility of LS incorporation in practical applications [

20]. Only minor increases in water content were required to match the slump of equivalent fly ash mixtures.

At higher LS dosages (above 30%), slight reductions in slump and flow have been observed, consistent with the behaviour of other finely ground mineral additives. For instance, while 10–20% LS had negligible impact on fresh concrete workability, a 30% re-placement level resulted in a modest slump reduction—still within workable limits [

26]. The application of superplasticisers proved effective in mitigating this reduction, restoring flow and ensuring consistency.

In addition to its influence on slump, LS contributes positively to the cohesion of the mix. Its fine particles act as micro-fillers, enhancing particle packing density and reducing segregation potential [

20]. The improved cohesion also aids in stabilising the air void system, with entrapped air contents reported by around 2 ± 0.5%, comparable to that of control mixes. Moreover, LS particles serve as nucleation sites in the fresh paste, promoting early structure formation and contributing to pore refinement from the earliest hydration stages [

7,

20].

2.2.2. Setting Time

Lithium slag (LS) accelerates the setting time of cementitious systems due to its gypsum and sulphate content. The early formation of ettringite, driven by the availability of sulphate from bassanite or anhydrite in LS, can lead to rapid water consumption and faster paste stiffening. Partial replacement of cement with LS consistently shortened both initial and final setting times compared to ordinary Portland cement (OPC) controls [

6,

20]. This acceleration can be advantageous for early demolishing, particularly under low-temperature conditions.

However, at high replacement levels, the risk of flash setting may increase if the system is not properly managed. Despite this, most studies involving up to 30% LS report set times well within the acceptable range. For example, initial and final setting times for concrete mixes containing 0–30% LS differed from the control by no more than one hour [

33]. The study [

34], investigated the effect of LS and limestone powder on the properties of the concrete and the findings revealed that the added cementitious material reduced the setting time and study also showed that the optimal content should not exceed 30%. These results suggest that moderate LS contents align with standard setting profiles and offer practical benefits in early-strength applications or where formwork removal is time-sensitive.

2.2.3. Fresh Density and Air Content

LS’s lower specific gravity (~2.5) slightly reduces concrete density, though values re-main within normal weight range (~2350 kg/m³) [

20]. This minimal change is attributed to the moderate replacement levels used and the maintenance of a constant total binder content. Comparisons between LS- and fly ash-based concretes showed unit weight differences of less than 1%, confirming the negligible effect of LS on density [

20].

Regarding air content, LS does not significantly influence the amount of entrained or entrapped air. Although LS contains fine chenarticles that can aid in stabilising microscopic air voids, measured air contents across various mixes consistently average around 2%, comparable to both OPC and fly ash reference mixes [

20]. This stability suggests that LS does not introduce problematic levels of entrapped air.

Overall, LS can be incorporated into concrete without adverse effects on fresh properties. With minor adjustments to water content or superplasticiser dosage at higher re-placement levels, workability, density, and air content remain within acceptable limits. Even high-volume LS concrete (50–60%) maintains adequate plasticity when properly dosed with admixtures [

20]. These outcomes indicate that LS-modified concrete can be mixed, placed, and finished using standard practices similar to conventional or fly ash-based concretes. The summary of the fresh-state performance characteristics of LS-modified concrete is provided in Table 3, based on a comparative review of recent studies.

Table 3.

Summary of Fresh Properties of Lithium Slag (LS)-Modified Concrete at Varying Replacement Levels [

6,

19,

20,

26].

Table 3.

Summary of Fresh Properties of Lithium Slag (LS)-Modified Concrete at Varying Replacement Levels [

6,

19,

20,

26].

| LS Replacement Level (% by mass) |

Slump (mm) |

Initial Setting Time (min) |

Final Setting Time (min) |

Unit Weight (kg/m³) |

Air Content (%) |

| 0 (Control) |

135 ± 5 |

150–165 |

210–225 |

2350 |

2 |

| 10% |

130 ± 5 |

140–155 |

200–215 |

2340 |

2 |

| 20% |

125 ± 10 |

130–150 |

195–210 |

2330 |

2 |

| 30% |

120 ± 10 |

125–145 |

190–205 |

2320 |

2.1 |

| 40% |

110 ± 15 |

110–135 |

180–200 |

2310 |

2.2 |

Overall, LS can be effectively incorporated into concrete at replacement levels up to 30% without adversely affecting fresh-state performance. With appropriate mix design adjustments, including superplasticiser optimisation, LS-modified concrete maintains acceptable workability, stable air content, and reliable setting times—demonstrating its suitability for conventional and sustainable construction applications.

2.3. Mechanical Performance

The incorporation of lithium slag (LS) as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) has consistently demonstrated notable enhancements in the mechanical properties of concrete. Studies show that LS improves strength, stiffness, shrinkage, and creep resistance. These parameters are critical in assessing structural integrity, serviceability, and long-term durability in concrete applications.

Among the evaluated parameters, compressive strength remains the most comprehensively studied. Partial replacement of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) with LS—typically between 15% and 30%—has been shown to significantly enhance compressive strength, attributable to increased pozzolanic activity, pore refinement, and matrix densification [

20,

26,

33]. The formation of secondary calcium-silicate-hydrate (C–S–H) and ettringite (AFt) further contributes to a denser and more cohesive microstructure, improving load-bearing capacity under sustained and cyclic conditions.

In addition to compressive strength, LS contributes positively to splitting tensile and flexural strength, as well as stiffness (elastic modulus), by mitigating microcracking, enhancing particle packing, and refining pore structure [

24,

29]. The porous morphology of LS particles supports internal curing by retaining water, which facilitates sustained hydration and reduces early-age cracking.

2.3.1. Compressive Strength

Numerous studies have identified 20% lithium slag (LS) replacement as the optimal dosage for enhancing the compressive strength of concrete. The studies [

33] and [

26] tested LS at 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% cement replacement levels, reporting that 20% LS consistently yielded the highest compressive strength from 28 to 90 days. Specifically, the 20% LS mix outperformed both the control and other replacement levels, achieving 5–10% higher strength at 90 days. These improvements were attributed to continued pozzolanic activity, pore structure refinement, and secondary hydration, as confirmed via mercury intrusion porosimetry [

33].

The authors of [

20] investigated a broader dosage spectrum, evaluating lithium slag (LS) replacements up to 60% and comparing performance with that of equivalent fly ash (FA) mixes. At 28 days, the 20% LS mix achieved a peak compressive strength of 49.3 MPa, slightly outperforming both the control and 20% FA mix. Strength gains continued over time, with the 40% LS mix reaching 58.6 MPa by day 90, approximately 65% higher than its FA counterpart. These results highlight LS’s superior long-term pozzolanic reactivity and confirm its technical viability up to 40% substitution.

In the context of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC), lithium slag exhibited similar benefits. The investigation [

29] reported that incorporating 20% LS into a UHPC mixture—containing steel fibres and a low water-to-binder ratio—resulted in a 28-day compressive strength of 134.5 MPa, marginally exceeding that of the control mix without LS. This enhancement was attributed to internal curing effects and the nucleation potential of LS for calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) formation, highlighting its efficacy as a high-reactivity ultrafine pozzolanic material. The study [

35] investigated the mechanical properties of the LS as SCM substitute while varying the particle size. The authors revealed that the particle size of 11.71 μm of LS achieves a high compressive strength of 28 days, which is 107% higher compared to OPC.

The investigation [

26] and [

24] further validated the 20–30% LS replacement range for normal-strength concrete. Authors of [

20] found that 20% LS led to an ~8% improvement over the control at 28 days, while 10% and 30% yielded slightly lower results. Further, the study [

24] demonstrated that 20% LS compensated for the strength loss typically associated with recycled aggregates. Their 20% LS + recycled aggregate mix reached a compressive strength equal to or exceeding the control made with natural aggregates. However, strength again declined at 40% LS, aligning with previous findings on the limits of high-volume substitution.

The previous study [

36] explored a binary system combining LS with iron ore tailings (IOTs) and found that a 20% LS mix achieved 52 MPa, an increase of 15% over the control. This enhancement was linked to improved interfacial transition zones (ITZ) due to reduced calcium hydroxide and increased C–S–H formation. The previous investigation[

22] reported that 20–40% LS replacement consistently achieved compressive strengths around 50 MPa, with improvements of 10–20% over the control. They noted that beyond 20%, strength gains began to plateau, indicating diminishing returns with higher LS content. The study [

37] revealed that 40% cement replacement of LS was able to show 18.34% higher compressive strength at 180 days compared to the control mix. Further, they observed that beyond the 60% replacement of LS led to a decline in the concrete properties.

Collectively, these findings reinforce that LS, particularly at 20–30% replacement levels, enhances compressive strength across a variety of concrete systems. This is primarily due to its active pozzolanic reactivity, pore refinement capability, and ability to promote long-term strength development via sustained C–S–H generation. These results establish LS as a technically robust SCM with consistent performance advantages over conventional fly ash or high OPC content systems. As detailed in

Table 4, compressive strength consistently improved with LS substitution, particularly around 20–30%.

The compressive strength data summarised in

Table 4 adhere to technical standards to ensure reliability and comparability across studies. Testing was conducted following ASTM C39/C39M and AS 1012.9 procedures for compressive strength measurement of cylindrical specimens under controlled curing conditions (20 ± 2 °C). Mixes complied with AS 1379 and EN 206-1 for water-to-binder ratios (0.30–0.50) and compaction methods, while LS replacement levels (10–40%) were calculated by mass as partial OPC substitution under ASTM C618 SCM classification. Loading rates of 0.25 ± 0.05 MPa/s were applied per ASTM C39 to capture accurate peak loads without shock loading. UHPC mixtures followed ASTM C1856 protocols, with microstructural validation via mercury intrusion porosimetry and SEM confirming hydration and pore structure development. These standards collectively ensure that the

Table 4 data is technically robust, supporting accurate LS dosage optimisation for performance enhancement.

Table 3.

Compressive strength performance of concrete with 10–40% LS replacement, highlighting peak strength at 20–30% substitution [

20,

22,

24,

26,

29,

33,

36,

37].

Table 3.

Compressive strength performance of concrete with 10–40% LS replacement, highlighting peak strength at 20–30% substitution [

20,

22,

24,

26,

29,

33,

36,

37].

| Study |

Best LS % (Age) |

Compressive Strength |

Compared to Control |

Key Findings |

| [22] |

20–40% (28 d) |

~50 MPa |

+10–20% |

↓ Permeability; no strength gain >20% |

| [24] |

20% (28 d) |

~48 MPa |

~ +5% |

Offset RA loss; >40% LS ↓ strength |

| [33] |

20% (90 d) |

~48 MPa |

+5 – 10% |

Higher modulus; lowest creep & shrinkage |

| [26] |

20% (28 d) |

~45 MPa |

+8% |

Highest flexural (+13%); boost at 100 °C |

| [20] |

40% (90 d) |

58.6 MPa |

+5% vs Ctrl; +65% vs FA |

Better tensile & modulus than FA; >40% LS ↓ strength |

| [29] |

20% (28 d, UHPC) |

134.5 MPa |

+2% |

Denser matrix; internal curing benefits |

| [36] |

20% (28 d, w/ IOTs) |

52 MPa |

15% |

Better ITZ; ↓ CH; ↑ C–S–H |

| [37] |

40%(90-180d) |

~60 MPa |

+18% |

↓ Porosity, VPV, Sorptivity |

Table 4 consolidates compressive strength outcomes reported across several key studies on lithium slag (LS) concrete. In nearly all cases, LS replacement within the 20–30% range proved most effective for enhancing compressive strength at 28 to 90 days. Strength improvements, ranging from 5% to 20% over control mixes—are consistently attributed to LS’s pozzolanic reactivity, microstructural densification, and the promotion of extended hydration kinetics. These strength gains are often accompanied by reduced porosity and improved pore size distribution, which enhance both early and long-term structural integrity. Additionally, LS’s reactive silica contributes to the formation of secondary C–S–H gels, which improve the paste–aggregate bond and delay strength regression at later ages. The uniform dispersion of fine LS particles also contributes to particle packing and filler effects, further strengthening the hardened matrix. Such multifaceted mechanisms reflect LS’s dual role as both a reactive binder and a micro-filler, particularly when used at optimized replacement levels.

Notably, a 40% LS replacement level not only outperformed the control mix but also surpassed the compressive strength of equivalent fly ash blends, underscoring LS’s potential for superior long-term performance [

20]. In the context of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC), the incorporation of 20% LS was shown to enhance internal curing and promote advanced hydration kinetics, resulting in exceptional mechanical properties [

29]. Similarly, LS has demonstrated its capacity to mitigate strength limitations in recycled aggregate concrete [

24] and ternary SCM systems incorporating iron ore tailings and phosphate slag [

36].

However, most studies also observed that LS replacement levels exceeding 40% tend to reduce strength performance, likely due to the dilution of cementitious components and a lower availability of reactive calcium silicates. Collectively, these findings affirm the mechanical viability of LS as a sustainable supplementary cementitious material, provided that the replacement dosage is optimised to balance pozzolanic activity, binder efficiency, and long-term performance.

2.3.2. Tensile and Flexural Strength

The tensile splitting and flexural strengths of lithium slag (LS) concrete generally exhibit trends parallel to those of compressive strength. When compressive strength is maintained or enhanced through LS incorporation, corresponding improvements in tensile and flexural strength are typically observed. For example, Rahman et al. [

20] reported a 90-day splitting tensile strength of 4.10 MPa for a concrete mix containing 40% LS, compared to 3.0 MPa for a similar mix incorporating 40% fly ash (FA). This tensile strength corresponded to approximately 10% of the mix’s compressive strength—an expected ratio for well-designed concrete—indicating that LS substitution does not compromise tensile performance or increase brittleness. Another study was conducted [

38] to explore the stress-strain behaviour of concrete combined with steel fiber (SF) and LS, and observed the LS improve the tensile performance of the concrete better than that of steel fiber along. Increased tensile strength is particularly important in controlling crack initiation and propagation under service loads. Flexural testing has shown that LS contributes to improved load distribution and reduced stress concentrations at critical points. These enhancements are beneficial in applications such as pavements, slabs, and structural elements where flexural and tensile demands are prominent.

Table 5 illustrates the summary of tensile strength performance of LS blended concrete.

Optimal LS replacements (~20%) typically yield a 5–10% increase in splitting tensile strength while preserving the tensile-to-compressive strength ratio (~10%) expected in quality concrete. Excessive LS (>30%) may lead to plateau or slight reductions, confirming ~20% as optimal for enhancing crack resistance and microstructural densification.

When considering the previous studies, the flexural strength performance as illustrated in

Table 6 shows a similar trend. An 8.33% increase in flexural strength was observed at 20% LS replacement under ambient curing conditions [

26]. Additionally, LS-blended concrete exhibited superior residual flexural strength following high-temperature exposure. For instance, a mix containing 10% LS retained approximately 24% more flexural strength than the control after thermal loading [

39]. Further, research was conducted by [

40] to investigate the relationship of stress-strain of LS with rubber concrete, revealing that 20% of LS enhanced the compressive strength by 21.57%, elastic modulus by 6.92% and peak strain by 17.26% the properties directly combined with an increase of flexural capacity of the concrete.

LS at ~20% generally increases flexural strength by 5–10% over control mixes, enhancing performance under thermal loading and in modified aggregate systems while supporting microstructural integrity.

These findings highlight LS’s role not only in enhancing baseline flexural performance but also in contributing to improved thermal resistance and long-term durability. Such enhancements are attributed to refined microstructure, increased C–S–H gel formation, and improved interfacial bonding at the paste–aggregate transition zone. Moreover, LS-modified mixes demonstrate reduced crack width and enhanced post-peak toughness, particularly under flexural stress. These mechanical benefits, when combined with improved thermal stability, position LS as a multifunctional SCM suitable for high-performance and resilient infrastructure applications. To consolidate the findings,

Table 7 summarises tensile and flexural strength trends of LS-blended concrete relatives to control mixes.

The summary indicates that ~20% LS replacement consistently provides the best tensile and flexural gains, with higher dosages leading to plateau or slight declines due to binder dilution while maintaining balanced mechanical property ratios.

Furthermore, the static elastic modulus increased with LS content up to 20%, with the 20% LS mix exhibiting the highest stiffness among all tested specimens [

33]. This improvement is linked to microstructural densification driven by sustained pozzolanic activity, which reduces internal porosity and mitigates microcrack propagation under load. Overall, moderate LS incorporation significantly enhances tensile and flexural performance, as well as elastic stiffness, thereby reinforcing its potential as a multifunctional supplementary cementitious material (SCM) for durable and high-performance concrete applications.

2.3.3. Creep and Shrinkage

Lithium slag (LS) reduces creep and shrinkage, thereby improving the long-term dimensional stability of concrete. A 20% LS replacement was found to yield the lowest drying shrinkage and specific creep strain at 90 days, outperforming ordinary Portland cement (OPC) mixes in deformation control [

33]. These improvements are attributed to reduced porosity and enhanced matrix density, as discussed in

Section 2.4.1 on permeability. The denser microstructure also promotes uniform internal stress distribution, which minimises strain concentration and microcrack development under sustained loads.

Table 8 summarises the effects of LS on drying shrinkage and creep performance in concrete systems. The investigation [

36] reported that the lower calcium hydroxide (CH) content in LS-blended systems may reduce internal microcracking, a primary contributor to creep deformation. This is consistent with findings that pozzolanic reaction-driven microstructural densification limits time-dependent strain under sustained loading [

33]

The study [

20] observed that 40% LS concrete exceeded the 28-day compressive strength predicted by standard models such as ACI and AS 3600, suggesting that current design codes may overestimate creep in LS concretes due to unaccounted stiffness gains and pozzolanic activity. Although explicit creep coefficients were not provided, the authors of [

33] documented a 20–30% reduction in creep strain in concrete with 20% LS, reinforcing its benefit in minimizing delayed deformation.

An LS replacement of ~20% significantly reduces shrinkage and creep (by 10–30%), improving dimensional stability and long-term durability in sustainable concrete.

At optimal replacement levels (typically 20% for early strength and up to 30–40% for long-term performance), LS enhances structural stability while maintaining mechanical integrity. Unlike many Class F fly ashes that compromise early-age strength, LS improves both early and late-age compressive, tensile, and flexural properties [

20,

26].

However, at high LS contents (>50%), dilution of cementitious phases outweighs pozzolanic benefits, leading to an observed 15–20% drop in compressive strength compared to control mixes [

20]. Thus, mix designs must balance sustainability with performance to ensure optimal mechanical behavior. This trade-off underscores the importance of identifying the threshold beyond which LS addition becomes detrimental to mechanical and durability performance.

2.4. Durability and High-Temperature Resistance

Lithium slag (LS) significantly enhances concrete durability by improving impermeability, resistance to aggressive environments, and dimensional stability. These effects are linked to LS’s pozzolanic reactivity, which reduces calcium hydroxide (CH), densifies the matrix, and promotes stable hydrate formation such as C–S–H and AFt. In particular, the synergistic interaction between LS and other SCMs or mineral additives can further amplify these durability gains.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that LS-blended concrete exhibits reduced transport properties, improved chemical resistance, and enhanced long-term performance under aggressive environmental exposures. These durability benefits are primarily attributed to LS’s high amorphous silica content, fine particle size, and its ability to consume calcium hydroxide while promoting the formation of additional binding phases. As shown in

Table 9, these durability improvements have been consistently observed across a range of experimental conditions and LS replacement levels.

2.4.1. Permeability and Water Absorption

Lithium slag (LS) improves the durability of concrete by refining its pore structure and significantly reducing overall permeability. Studies by [

6,

19] reported notably lower water absorption rates and reduced sensitivity to moisture ingress in LS-blended concrete compared to ordinary Portland cement (OPC) controls. These enhancements are primarily attributed to the formation of additional calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gels and the substantial reduction in capillary pore connectivity, resulting in a denser and more impermeable matrix. The presence of reactive silica in LS accelerates secondary C–S–H gel growth, which effectively fills micro voids and disrupts capillary continuity. Such microstructural refinement plays a crucial role in enhancing the material’s resistance to long-term durability threats, including carbonation, chloride ingress, and freeze–thaw cycles. The study [

41], investigated the performance of LS as SCM in reducing chloride penetration, which can enhance the corrosion of reinforcement in marine environments. The researchers used 20-60% of LS as a substitute for cement and the results revealed that the penetration decreased by 76-78% compared with the normal concrete, confirming the effectiveness of the LS character as SCM. Furthermore, the finding of [

42] indicates that the volume of permeable voids (VPV) decreased by 30% as cement was replaced by 20% of lithium slag. The VPV decreased due to the form of C-S-H gels due to the pozzolanic reaction of LS, which filled the pores of the concrete making it less porous.

The research [

26] observed up to a 28% reduction in water absorption with 20% LS replacement, while [

25] reported significant decreases in chloride diffusion coefficients, indicating stronger resistance to the ingress of aggressive agents such as chloride ions. This improved impermeability makes LS-enhanced concrete particularly suitable for marine and deicing environments.

Further evidence from the study [

43] demonstrated that as LS content increased from 10% to 40%, the internal pore structure of lightweight aggregate (LWA) concrete transformed. Specifically, the volume of smaller pores (<600 μm) was significantly reduced, while larger pores (>1000 μm) became more dominant. This shift led to an overall refinement in pore continuity, reducing permeability and enhancing durability. The improvement was directly linked to increased C–S–H formation and the disruption of interconnected pore networks.

A summary of key experimental studies on the permeability and absorption performance of LS-modified concrete is presented in

Table 10.

Table 10 highlights the consistent findings across multiple studies that LS incorporation leads to a denser, more impermeable concrete matrix. These benefits make LS an effective material for improving the permeability resistance of concrete in aggressive environments. Such improvements are especially valuable for infrastructure exposed to marine, coastal, or deicing conditions, where chloride and moisture ingress are critical concerns. Furthermore, the refined pore structure contributes not only to impermeability but also to durability metrics such as freeze–thaw resistance and carbonation depth.

2.4.2. Alkali–Silica Reaction (ASR)

Lithium slag (LS) mitigates alkali–silica reaction (ASR) through a combination of chemical and microstructural mechanisms, including low alkali content and pore refinement. Concretes incorporating LS have shown improved interfacial transition zones (ITZ), which enhance matrix–aggregate bonding and reduce crack initiation points typically associated with ASR [

36]. Guo and Wang suggested that LS may stabilise reactive aggregates by modifying the pore solution chemistry and reducing alkali ion mobility, though they emphasised the need for more targeted ASR-specific testing to validate these effects [

27].

The chemical composition of LS further supports its potential as an ASR mitigation agent. Its high alumina content can bind free alkalis through secondary hydration reactions, thereby lowering the concentration of sodium (Na⁺) and potassium (K⁺) ions responsible for expansive silica gel formation. Furthermore, the pozzolanic activity of LS reduces calcium hydroxide (CH) content and lowers the pH of the pore solution, both of which decrease the solubility of reactive silica in aggregates and suppress the development of deleterious ASR expansion [

11].

A theoretical advantage also stems from the possibility that residual lithium compounds in LS could actively inhibit ASR. Lithium salts are well-established in the literature as effective ASR suppressants, and if present in soluble form within LS, they may directly disrupt expansive gel formation. However, this hypothesis remains speculative and requires chemical and durability testing to be dedicated to confirm it.

To date, no published LS-concrete study has reported ASR-induced cracking or significant expansion. The study [

36] observed that LS-modified mixes showed refined ITZ microstructure, reduced permeability, and limited microcrack development—factors known to reduce ASR susceptibility. While these findings are largely qualitative, they align with the performance of other SCMs like fly ash and slag, which are widely accepted as ASR-mitigating agents.

In summary, although quantitative ASR expansion testing on LS-incorporated concrete is limited, the combined benefits of lower alkali content, CH reduction, refined pore structure, and the potential presence of lithium residues suggest that LS is likely to reduce ASR risk. Further controlled experiments are encouraged to validate these promising indications and to define LS’s role in ASR mitigation strategies.

2.4.3. Sulphate and Acid Resistance

Lithium slag (LS) enhances concrete resistance to sulphate and acid attack by refining the matrix, reducing calcium hydroxide (CH), and stabilising hydration phases. Acid resistance tests conducted under simulated acid rain exposure (pH ≈ 3) demonstrated that a 40% LS replacement provided the greatest performance enhancement, with substantially reduced surface degradation and improved mass retention [

26,

36]. These improvements were attributed to the reduction in portlandite content and the formation of chemically stable hydration products, which slowed deterioration in acidic environments [

26].

Sulphate resistance is likewise improved in LS-blended concrete. This is primarily due to the reduced tri-calcium aluminate (C₃A) content and the transformation of reactive hydration products into more stable and less expansive compounds. Concrete mixes incorporating LS exhibited reduced cracking and expansion under sulphate exposure when compared to OPC controls [

27]. These enhancements were linked to the pozzolanic reduction of CH and the binding of sulphate ions into non-expansive AFm or ettringite phases, mirroring benefits observed in sulphate-rich road base applications. A study [

44] was conducted to examine the polypropylene fiber lithium slag concrete behaviour under sulphate erosion and external loading. The study revealed that the concrete with lithium slag showed significant resistance to sulphate attack compared to normal concrete. The LS tend to improve the denser microstructure, which reduces the penetration of sulphate into concrete.

Under prolonged sulphuric acid exposure, LS-modified concrete outperforms conventional OPC mixes. The reference [

20] reported that concrete containing 40% LS retained up to 85% of its original compressive strength after 90 days in acidic conditions, whereas OPC-based controls declined to approximately 60%. Further evidence was provided by [

21], who found that in LS–lime systems, a substantial portion of the initially formed ettringite was converted to monocarboaluminate after 56 days of curing . This phase transition contributes to sulphate resistance by stabilising hydration products and reducing the likelihood of expansive reactions. While standardised sulphate expansion test data (e.g., ASTM C1012) for LS concrete remain limited, the underlying chemistry strongly supports its classification as a sulphate-resistant material.

These improvements are closely associated with reduced permeability, refined pore structure, and the capacity of LS to immobilise aggressive ions through secondary reactions. Acid rain corrosion tests involving sulphate and nitrate ions also showed that LS-modified concretes deteriorated more slowly than OPC controls, even at high replacement levels [

26]. Collectively, the evidence suggests that LS provides sulphate and acid resistance performance comparable to well-established SCMs such as Class F fly ash, due to its pore-filling effect, pozzolanic activity, and formation of durable AFm phases.

2.4.4. Freeze–Thaw Resistance

In cold climates, concrete structures must withstand repeated freeze and thaw cycles, which directly impose internal stresses on the concrete. The damage due to freez-thaw disturb the outside appearance and gradually declines the strength and durability of the structure. The repairing cost of damage caused due to freeze-thaw is markedly more expensive [

45]. Incorporating LS enhances freeze–thaw durability by densifying the pore structure and limiting moisture retention in the hardened matrix. A 10% LS replacement level was found to improve freeze–thaw resistance by decreasing pore connectivity and reducing the volume of large capillary pores [

7]. These microstructural modifications led to lower mass loss and a smaller reduction in dynamic modulus during freeze–thaw cycling, indicating enhanced structural integrity under repeated thermal stress [

7].

The underlying mechanism is linked to LS’s ability to densify both the bulk cement paste and the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), thereby limiting water ingress and mitigating internal frost expansion. However, the same study cautioned that higher LS dosages (>30%) may inadvertently increase the proportion of fine pores, which could retain moisture if air entrainment is not properly controlled. This retained water may contribute to internal pressure build-up during freezing, potentially compromising durability under severe freeze–thaw conditions [

7].

Accordingly, it was recommended that LS content be limited to approximately 10% for concretes exposed to harsh freeze–thaw environments, unless appropriate air-entraining admixtures are incorporated [

7]. Notably, no reviewed study reported frost-induced deterioration in LS concrete. On the contrary, most experimental results indicated that LS-modified concretes performed as well as, or better than, control mixes in terms of freeze–thaw durability.

In summary, lithium slag can enhance freeze–thaw performance at moderate replacement levels by reducing permeability and refining the internal pore network. However, to ensure optimal resistance in cold climates, LS dosage should be conservatively managed or used in conjunction with air-entraining agents to prevent moisture entrapment and internal cracking.

2.4.5. High-Temperature Resistance

Lithium slag (LS) significantly improves the thermal stability of concrete, particularly at elevated temperatures up to 700 °C. Residual strengths after exposure to 100, 300, 500, and 700 °C for concretes containing 0–30% LS were evaluated in a recent study [

26]. They found that at 100 °C, LS concretes even exhibited a slight strength gain compared to room temperature—likely due to accelerated hydration and pore drying—whereas beyond 300 °C, all concretes incurred strength loss as expected [

26]. Crucially, the LS-containing specimens retained more strength than the plain concrete at each high-temperature threshold. Chen et al. [

24] reported that concrete with 20% LS retained over 75% of its compressive strength after exposure to 600 °C, compared to only 60% for OPC controls. This is due to the formation of calcium–alumino–silicate hydrate (C–A–S–H) phases, reduced portlandite content, and internal curing effects provided by LS’s fine particle structure and latent reactivity. Furthermore, LS contributes to improved thermal compatibility between the cement paste and aggregates, reducing differential expansion and crack formation [

25]. In particular, 20% LS was optimal: after exposure to 300 °C, the 20% LS concrete’s compressive strength was about 8% higher than the controls, and 10% LS was ~3% higher [

26]. At 500–700 °C, damage was severe for all mixes, but LS concretes still showed marginally better residual strength and lower mass loss. The mass loss after high-temperature exposure was lowest for the 20% LS mix, indicating less dehydration and cracking events [

26]. The authors concluded that an appropriate LS content (20%) improved high-temperature performance by refining the internal structure and possibly by lithium compounds stabilising certain hydration phases at elevated temperatures [

26]. Additionally, LS releases hydration water more gradually—some from AFt/AFm phases—which may provide internal curing and delay crack formation during heating.

The study [

46], evaluated the behaviour of LS under temperatures ranging from 0 to 1100 °C, and the authors revealed that the early and long-term compressive strength of 600-700°C thermal-activated LS blended cement mortar significantly improved. The thermally treated LS showed high pozzolanic activity, which accelerates the formation of C-S-H. The researchers [

39] extended the application of lithium slag (LS) to recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) and reported even more pronounced benefits under elevated temperature conditions. In their study, 100% RAC mixes incorporating 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% LS were subjected to thermal exposure ranging from 200 °C to 600 °C. The inclusion of LS significantly mitigated strength degradation. Specifically, at 600 °C, the residual compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths of the RAC mix containing 20% LS were 34–37% higher than those of the LS-free control mix. The enhanced strength retention prompted the derivation of empirical models that identified LS content as a statistically significant variable contributing to residual strength performance. This improvement in thermal stability was attributed to multiple factors: the reduced presence of calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂), which undergoes endothermic decomposition around 400 °C; refinement of pore structure, which diminishes internal vapor pressure and the risk of explosive spalling; and the formation of calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) phases with higher aluminium content, known to confer improved thermal resistance [

39].

These results indicate that LS concrete can better withstand fire or high-temperature exposure, making it an advantageous material for structural, pavement, and infrastructure applications where thermal resistance is a critical consideration. This enhanced thermal performance is primarily attributed to the formation of thermally stable phases and reduced microcracking under elevated temperatures, as observed in LS-blended systems.

2.4.6. Carbonation

It was identified that the carbonation of concrete happens when CO₂ in the natural air enters through the pores in the concrete and reacts with Ca (OH)₂ and produce CaCO

3 and water. Over time, the reaction can lower the PH value of concrete and lead to steel corrosion [

47]. While direct investigations into the carbonation resistance of lithium slag (LS)-blended concrete are limited, existing studies and insights from analogous supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) suggest that LS may exhibit a slightly higher carbonation rate than ordinary Portland cement (OPC) concrete due to its lower portlandite (Ca(OH)₂) content [

11,

48]. The pozzolanic reaction of LS consumes CH, which serves as a buffer against carbonation. Consequently, LS concretes may have reduced alkaline reserves, allowing CO₂ to penetrate more readily in the absence of compensating factors.

However, LS concretes typically develop a refined and densified pore structure, which can significantly slow the ingress of CO₂ [

23,

27]. Guo and Wang [

27], He et al. [

49], and Khair et al. [

23] reported that the microstructural densification resulting from LS incorporation offsets the reduction in CH, thereby maintaining carbonation resistance at a level comparable to that of fly ash-blended concrete. This microstructural refinement is typically enhanced under adequate curing regimes, which promote secondary C–S–H formation and reduce pore connectivity. These findings are consistent with broader SCM behaviour, in which reduced porosity and permeability are more influential in limiting carbonation depth than CH content alone [

26].The study [

50] was conducted to investigate the properties of steel slag and lithium slag cement under carbonation curing conditions. The authors revealed that LS was not carbonated, but facilitated the carbonation of steel slag, which can produce CaCO

3 crystals, which can fill the cementitious pores and slow down CO₂ penetration.

No abnormal carbonation behaviour or surface degradation has been reported in LS-containing concrete to date. Nonetheless, long-term performance under aggressive CO₂ exposure (e.g., in urban or industrial environments) requires further validation. Studies [

27] and [

23] support the view that LS-modified concretes perform similarly to fly ash concrete when carbonation resistance is assessed in relation to compressive strength and permeability class.

In summary, although reduced portlandite may theoretically increase carbonation susceptibility, the densified matrix produced by LS hydration reactions appears to compensate effectively. Based on current evidence, the carbonation resistance of LS concrete is considered comparable to that of other SCM-based systems of equivalent mix quality and curing conditions.

2.4.7. Heavy Metal Leaching

A unique consideration for lithium slag (LS) is its potential to release trace heavy metals, which may originate from the spodumene ore or chemical refining processes. Environmental concerns have been raised regarding the use of raw LS in unbound applications such as road base materials, where leaching into surrounding soils or groundwater could pose a risk [

27,

29]. However, when LS is incorporated into cementitious systems, this risk is significantly mitigated.

Studies have demonstrated that the hydration products formed in LS-blended concretes—particularly calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) and calcium aluminate phases (AFm)—are capable of immobilising heavy metal cations through both chemical binding and physical encapsulation. Leaching tests conducted on LS–cement and LS–geopolymer systems confirmed that concentrations of leached heavy metals remained well within regulatory safety thresholds [

22,

23]. This containment capability is attributed to the dense microstructure and high alkalinity of the cementitious matrix, which suppresses ion mobility. Specifically, [

22] examined the use of LS stabilised with magnesium slag for road subbase applications and demonstrated effective immobilisation of lead, cadmium, and arsenic through the formation of hydrated double salts and pozzolanic binding phases. These results highlight LS’s dual role as both a binder and an environmental stabiliser in infrastructure contexts. From both a durability and environmental standpoint, LS concrete offers a dual benefit: it repurposes an industrial by-product while securely immobilising hazardous components within a chemically stable matrix. This transformation of LS into a safe and sustainable construction material reinforces its value within circular economy frameworks.

Table 11 synthesises durability and thermal performance data from key studies on lithium slag (LS) concrete. Across multiple metrics—such as shrinkage, permeability, freeze–thaw resistance, acid/sulphate durability, and thermal stability—LS consistently enhances long-term concrete performance when used at optimal replacement levels, typically ranging between 20% and 30%.

The pozzolanic reaction between LS and calcium hydroxide (CH) produces dense calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) gels, effectively refining the pore structure. This microstructural densification results in reduced permeability and improved resistance to chloride ingress, carbonation, and chemical attack [

22,

26]. In addition, LS contributes to reductions in drying shrinkage and creep [

33], thereby lowering the risk of cracking and enhancing dimensional stability. These improvements are particularly notable in recycled aggregate concrete (RAC), where LS compensates for the inherent weaknesses of the parent material [

24,

39].

Regarding high-temperature performance, LS concretes have demonstrated superior residual strength and lower mass loss under thermal exposure. For example, Liang et al. reported an 8% compressive strength increase at 300 °C and minimal performance degradation up to 700 °C for concrete with 20% LS [

26]. In RAC systems, the inclusion of 20% LS resulted in up to 36% greater residual tensile strength after exposure to 600 °C compared to control mixes [

39].

Crucially, no significant durability trade-offs were observed. Although reduced portlandite content theoretically increases carbonation susceptibility, this effect was counteracted by the densified matrix, leading to comparable or improved carbonation resistance [

23,

27]. Additionally, environmental concerns regarding potential leaching of lithium or trace heavy metals were addressed by studies confirming their effective immobilisation within the hydrated cement matrix [

23,

27].

In summary, LS not only improves mechanical strength but also significantly enhances resistance to physical and chemical deterioration, ultimately extending service life and reducing maintenance requirements. These combined benefits align strongly with sustainable infrastructure targets and affirm LS’s viability as a durable, high-performance supplementary cementitious material.

2.5. Microstructural Enhancement in Lithium Slag–Blended Concrete

The microstructural evolution of lithium slag (LS)-blended concrete is a key factor underpinning its enhanced mechanical strength and long-term durability. Comprehensive characterisation using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), backscattered electron imaging (BSE), energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), and mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) has shown that LS substantially modifies the hydration process and pore structure at both the bulk matrix and interfacial transition zone (ITZ) levels [

6,

19,

31,

51].

LS accelerates cement hydration and promotes the formation of secondary calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) and calcium–alumino–silicate–hydrate (C–A–S–H) phases, while simultaneously reducing calcium hydroxide (CH) content through its pozzolanic activity. These reactions result in a denser and more refined microstructure, characterised by a finer pore network, fewer unreacted cement grains, and improved matrix compactness. The resulting structural enhancements directly lead to reduced porosity, lower permeability, and superior mechanical performance [

6,

29].

2.5.1. Bulk Matrix and Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) Densification

The incorporation of lithium slag (LS) significantly enhances the density and microstructural integrity of cementitious matrices by reducing calcium hydroxide (CH) content and increasing chemically bound water, as confirmed through X-ray diffraction (XRD) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) [

19,

31]. The authors of [

31], using inductively coupled plasma (ICP) and XRD, reported that replacing 10–30% of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) with LS reduces CH content by 28 days while simultaneously promoting ettringite formation and accelerating the development of calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) gel.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed that LS-modified pastes possess a more homogeneous and compact microstructure. Rod-like ettringite crystals and finely distributed C–S–H effectively fill interstitial voids, in contrast to the coarse CH accumulations observed in OPC control samples [

6,

51]. This matrix densification contributes directly to enhanced mechanical strength and long-term durability.

Within the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), LS plays a crucial role in improving aggregate–paste interactions. Backscattered electron (BSE) imaging and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping have shown that LS addition reduces porosity, improves particle packing, and promotes the formation of a continuous C–S–H layer enveloping aggregate surfaces [

20,

36]. These enhancements strengthen the interfacial bond and inhibit the initiation and propagation of microcracks. The study of [

51] it can be observed that LS accelerates the transformation of early-formed ettringite into more stable AFm phases and C–S–H within both the bulk matrix and ITZ during the first 28 days of hydration. These phase transitions—confirmed by multiple analytical techniques—highlight the role of LS in refining matrix composition and enhancing pore structure distribution.

In ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC), LS also exhibits superior reactivity. Findings of [

29], reported that LS-enhanced UHPC promotes the formation of calcium–alumino–silicate–hydrate (C–A–S–H) gels characterized by lower Ca/Si and higher Al/Si ratios, indicating greater aluminosilicate integration. In mixes with 20% LS, only 4% CH remained after 28 days, demonstrating high pozzolanic reactivity. The resulting compact, foil-like microstructure significantly improves mechanical performance and long-term durability.

2.5.2. Nano-Scale Observations and Reaction Rim Formation

Advanced microstructural analyses using high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) combined with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) have confirmed the nanoscale pozzolanic reactivity of lithium slag (LS) in cementitious systems. Rahman et al. [

20] identified a distinctive core–rim morphology in hydrated LS particles, where the silica- and alumina-rich inner core—containing trace lithium and potassium—remained largely unreacted. In contrast, the outer rim, enriched in calcium, sulphur, and aluminium, revealed the formation of calcium–aluminosulfohydrate (C–A–S–H), ettringite, and AFm phases along the LS–cement interface.

These reaction rims, primarily composed of fibrous calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) and secondary AFm-type hydrates, provide direct nanoscale evidence of sustained pozzolanic activity. Their progressive formation densifies the matrix and reduces pore connectivity, thereby enhancing long-term durability [

20]. This nanoscale transformation correlates with the macro-scale improvements observed in mechanical strength and durability performance.

Backscattered electron (BSE) imaging of concrete mixtures with 0–60% LS replacement, examined at 7 and 90 days, further supports these findings. The micrographs revealed co-existing partially hydrated cement (PHC), partially reacted LS (PRLS), and unhydrated LS (ALS), particularly in high LS-content mixes. As hydration progressed, reaction rims thickened and voids within the matrix were progressively filled, resulting in a denser microstructure and improved interfacial bonding.

By 56 days, many rim phases had evolved into more stable hydrates such as monocarboaluminate and secondary C–S–H, confirming the ongoing pozzolanic reaction of LS and its positive impact on the microstructural integrity and durability of concrete [

20,

26].

2.5.3. Pore Structure Refinement

The pore structure of cementitious composites plays a critical role in determining mechanical performance, permeability, and long-term durability. Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) analyses have consistently shown that the incorporation of lithium slag (LS) significantly refines the pore network. LS reduces total porosity and shifts the pore size distribution toward finer gel pores (<10 nm), enhancing matrix densification and limiting fluid ingress [

33].

Amongst various replacement levels, mixes containing 20% LS exhibit the most optimized pore structure, with a pronounced reduction in capillary pores larger than 100 nm. This refinement is attributed to improved particle packing and the suppression of permeable pathways, leading to enhanced compressive strength and durability.

Zhang et al. [

36] confirmed that although the total porosity of LS-blended concrete may be similar to that of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) systems, the gel pore fraction is more refined, with fewer interconnected voids. This microstructure is particularly advantageous for resisting water penetration, chloride ion diffusion, and freeze–thaw damage.

Gou et al. [

6] attributed LS’s pore-refining capacity to three primary mechanisms:

Physical Filler Effect: Finely ground LS particles occupy voids and enhance early matrix compaction.

Pozzolanic Reactivity: LS reacts with calcium hydroxide (CH), forming additional secondary C–S–H that reinforces the matrix.

Nucleation Effect: LS promotes the precipitation of hydration products, accelerating gel growth and further refining capillary pores.

Collectively, these mechanisms contribute to improved microstructural uniformity, reduced permeability, and enhanced long-term performance [

6,

48].

2.5.4. Evolution of Hydration Products

The evolution of hydration products in LS-blended systems reflects the ongoing pozzolanic activity and phase stabilization over time. Techniques such as SEM, EDS, and XRD have been widely applied to monitor these transformations. The study [

20] reported that ettringite (AFt) predominates during early curing (1–3 days), due to elevated sulphate and aluminate levels in LS. While AFt phases are still observable at 7 days, they progressively diminish by 56 days, giving way to more stable products such as monosulfoaluminate and calcium–alumino–silicate–hydrate (C–A–S–H) gels.

TGA results from [

25] revealed two major mass loss stages in LS-modified systems: dehydration below 170 °C and dehydroxylation/decarbonation between 400–750 °C. These mass losses correspond to the breakdown of hydroxylated and carbonate-bound phases, further confirming the presence of secondary hydration products and LS's contribution to long-term binder stability [

6].

Elemental mapping across the ITZ confirmed a temporal decline in sulphur (S) and aluminium (Al) concentrations—indicative of AFt consumption—accompanied by increased calcium (Ca) and silicon (Si), consistent with the formation of C–S–H and AFm phases [

20] . These compositional shifts demonstrate LS’s continued pozzolanic reactivity and its role in developing a more stable and durable hydration matrix.

The investigations [

48] and [

27] further corroborated that the conversion of expansive AFt to stable AFm phases not only reduces volumetric instability but also enhances homogeneity and mechanical resilience. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) confirms these transitions, showing increased bound water content and improved thermal stability in LS-modified systems. These findings affirm LS’s long-term contribution to phase transformation, microstructural stability, and durability enhancement.

2.5.5. ITZ improvement in Recycled Aggregate Concrete (RAC)

Recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) is often plagued by weak interfacial transition zones (ITZs), due to residual mortar on aggregates, high porosity, and poor bonding—leading to diminished mechanical properties. However, LS has demonstrated the capacity to mitigate these issues by refining ITZ microstructure and enhancing local reactivity.

The authors of [

24] observed that LS particles tend to concentrate near adhered mortar on recycled aggregates, where they participate in localized pozzolanic reactions. These reactions generate secondary C–S–H gels that fill microcracks and voids within the ITZ. This microstructural “healing” significantly improves packing density, initiates secondary hydration, and enhances ITZ cohesion.

The resulting densified ITZ facilitates stronger aggregate–paste bonding and more efficient stress transfer, thereby overcoming one of the key weaknesses of RAC. The results of [

23] confirmed that RAC containing LS achieved compressive strengths comparable to concrete with natural aggregates, validating LS as a viable SCM for recycled systems.

2.5.6. Microstructural–Sustainability Nexus