Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Experimental Design

- Hunting Perches plots had one T-shaped wooden perch (2.2 m tall, 0.4 m long crossbar) that was positioned at a distance of 5.65 m from the south side of the plot, allowing the raptors a place to stand (Figure 1). Each perch was situated at least 100 meters to the nearest neighboring plot, which is large enough to reduce visibility for both raptor [58] and vole home ranges [59]. There were also no natural or other manmade structures that raptors could use for perches within the areas.

- 1080 (Rodenticide) plots received a treatment of 30g of 0.05% Sodium fluoroacetate (mixed into a wheat bait) (known as Rosh80 or 1080). 1080 rodenticide was uniformly dispersed across the plots during two applications. The 1st application was made after data collection in session 1, and 2nd application was added ten days later. 1080 is the only rodenticide legally permitted for use in open agriculture in Israel and has been used with the same bait for 28 years [60]. It is highly toxic to wildlife and humans, and no known antidote exists. [60,61].

- Control plots had no treatment applied.

2.3. Treatments Plot Selection

2.3.1. Imaging of Fields

2.3.2. Pre-Processing

2.3.3. Calculating Vegetation Indices

2.3.4. Rodent Burrow Count

2.3.5. Selection of Potential Plots and Statistical Analysis

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Imaging of Plots

| Vegetation Index | Equation | Description | Source |

| NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) | Measures the presence and health of vegetation in an area. | [65] | |

| PRI (Photochemical Reflectance Index) | Measures sensitive to changes in carotenoid pigments in live foliage, which are indicative of photosynthetic efficiency. Drops indicate increased canopy stress. | [66] | |

| SIPI (Structure Insensitive Pigment Index) | Measures leaf pigment concentrations normalized for variations in overall canopy structure and foliage content. Increases in SIPI indicate increased canopy stress. | [67] |

2.4.2. Rodent Burrow Count and Alfalfa cover Estimation

2.4.3. Video Cameras

2.5. Processing Video Camera Footage

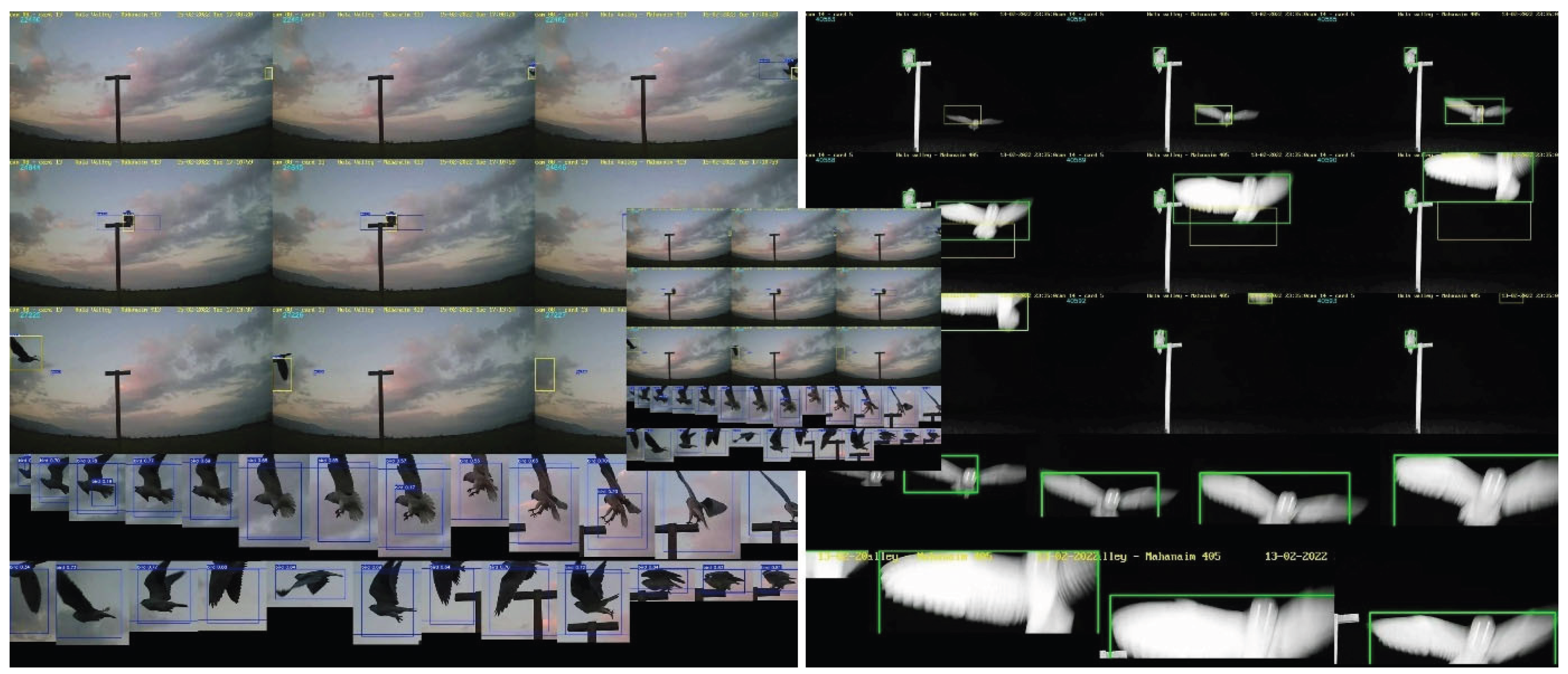

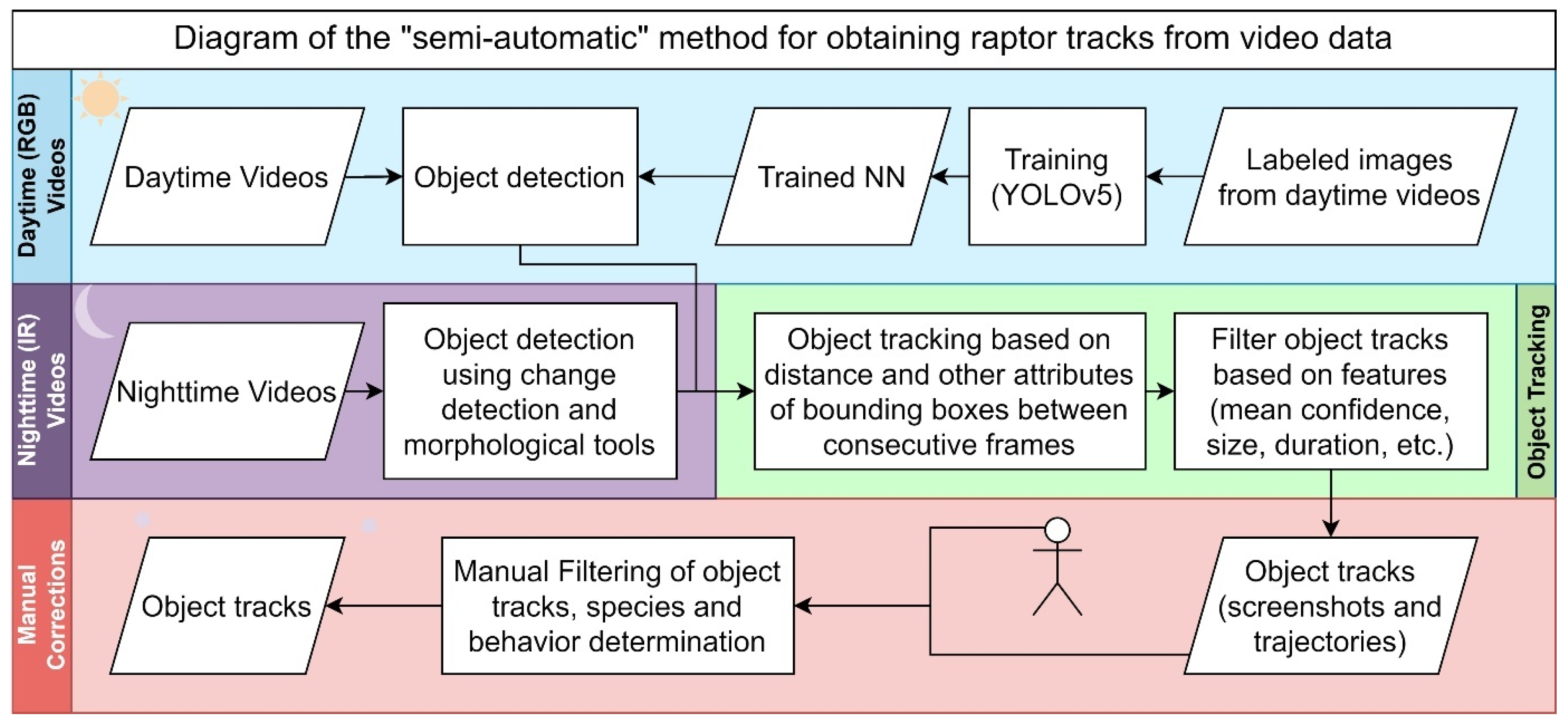

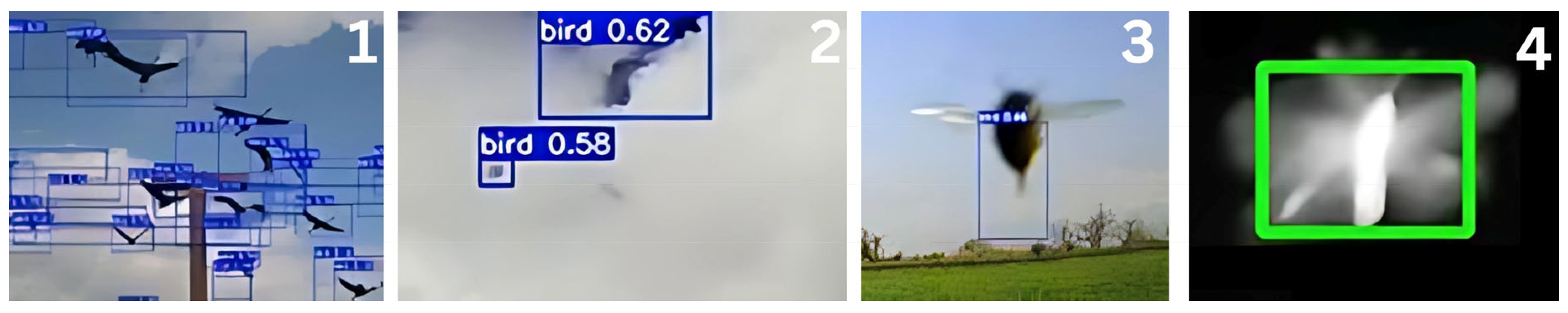

2.5.1. Step 1: Detection of Birds per Frame

2.5.2. Step 2: Object Tracking

2.5.3. Step 3: Manual Review

2.5.4. Step 4 Validation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

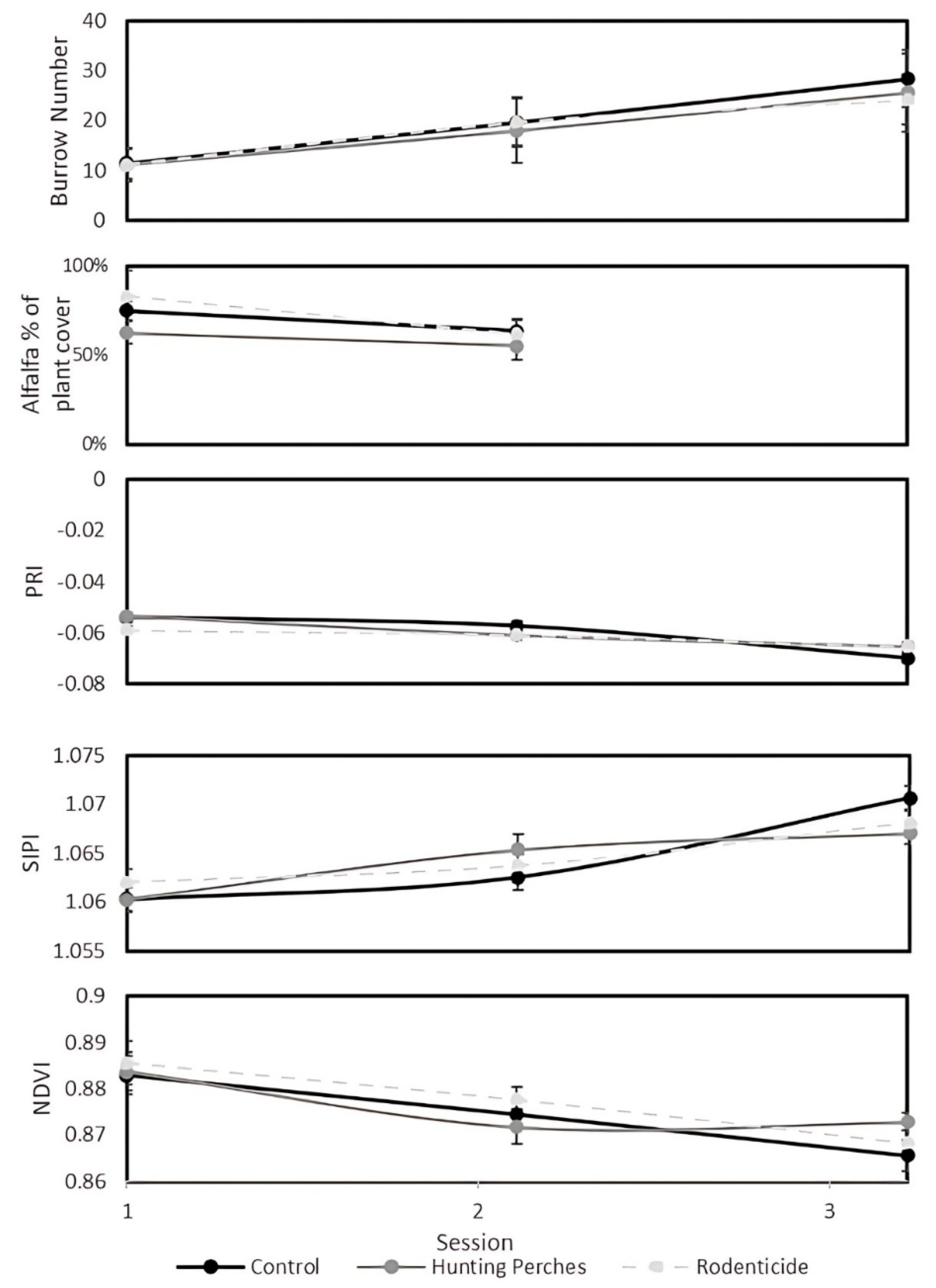

3.1. Treatments' Effect on Vole Activity and Alfalfa Health

3.2. Perch Use

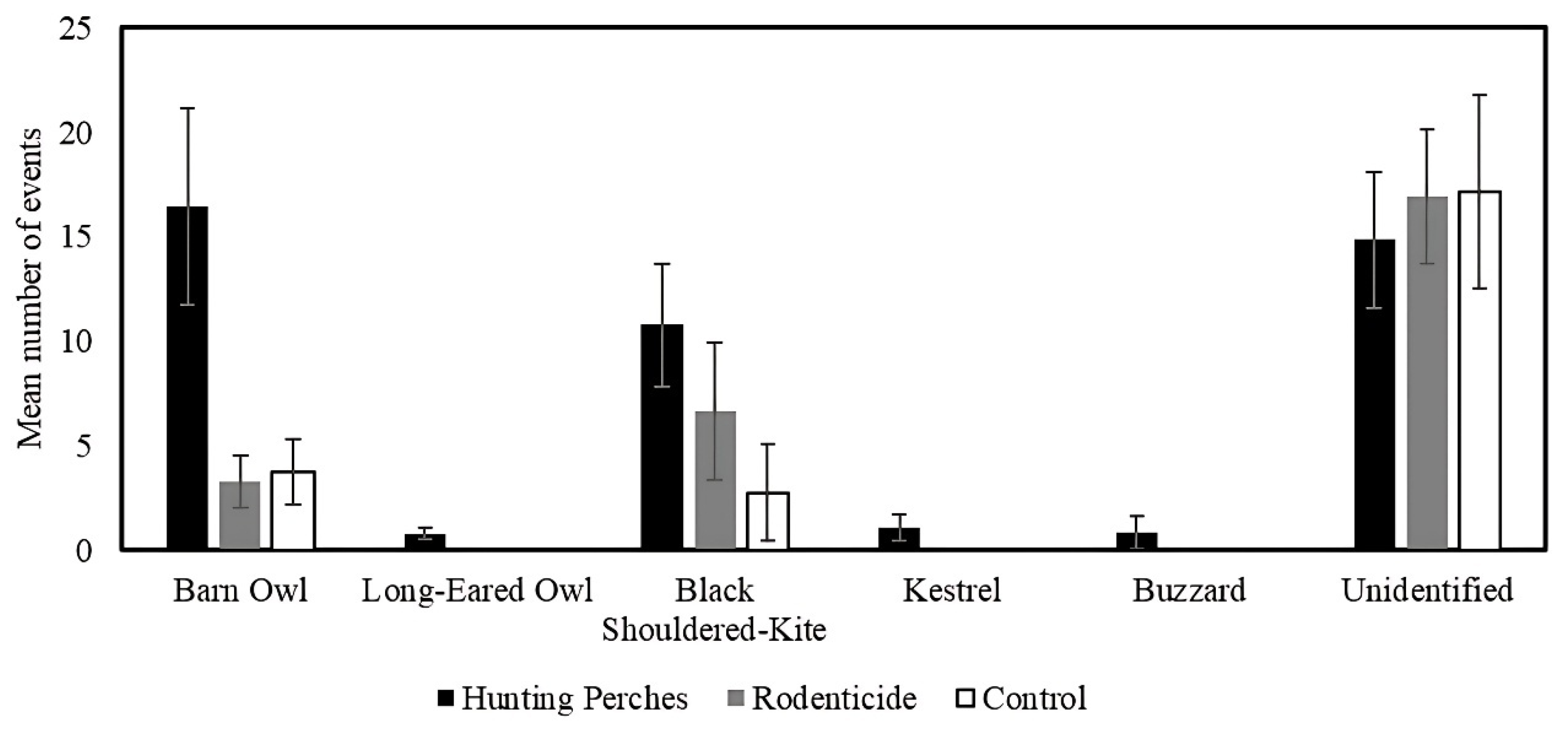

3.3. Comparison of the Number of Perching Events Between the Treatments

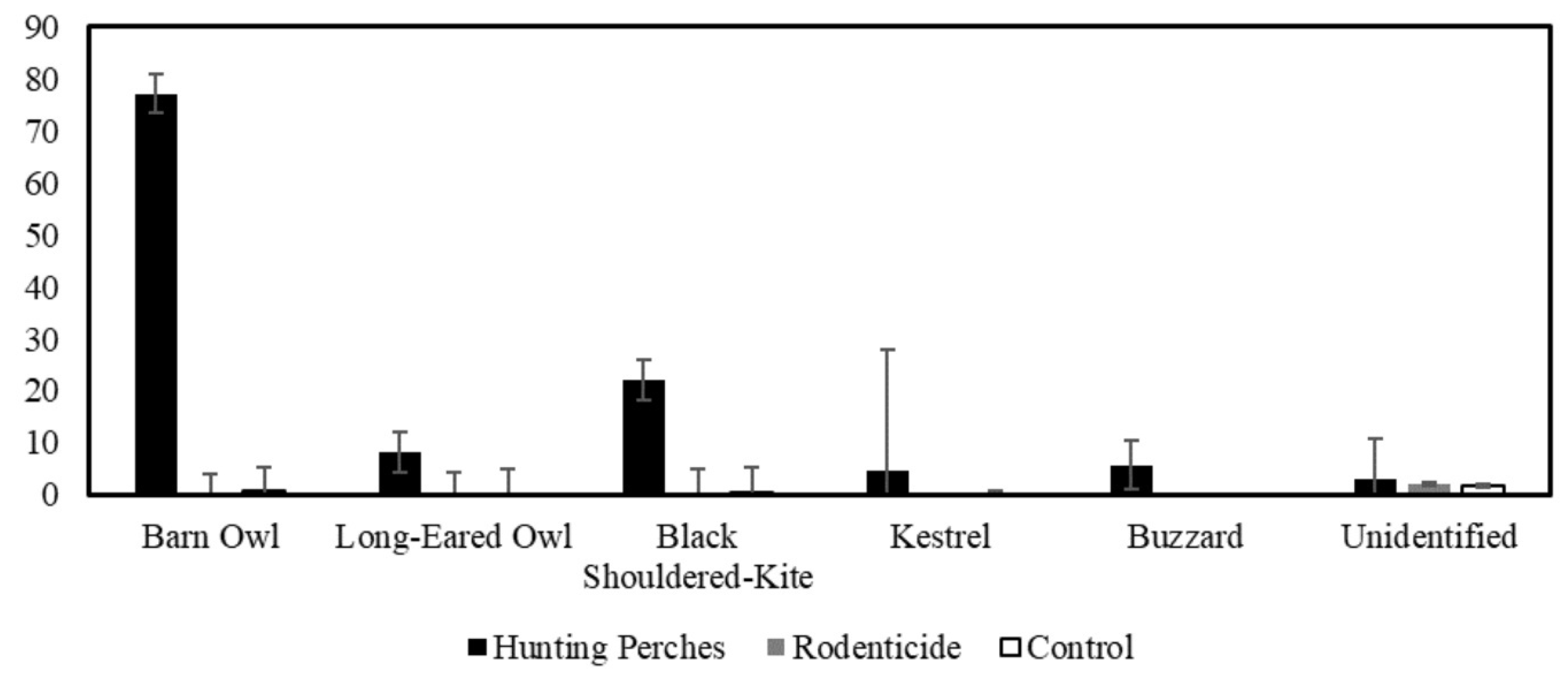

3.4. Comparison of the Time Spent Between the Treatments

3.5. Comparison Between Hunting Strategies in the Treatment Plots

3.6. The Relationship Between Rodent Burrows and the Duration Raptors Spent

4. Discussion

4.1. Treatment Effects on Raptor Activity and Vole Activity in Alfalfa Fields

4.2. The Use of Hunting Perches

4.3. Numerical and Functional Response

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McLaughlin, D.W. Land, Food, and Biodiversity: Land, Food, and Biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 1117–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, C.D.; Karp, D.S.; Meyer, C.F.J.; Hadly, E.A.; Daily, G.C. Predicting biodiversity change and averting collapse in agricultural landscapes. Nature 2014, 509, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, T.; Hudson, L.N.; Hill, S.L.L.; Contu, S.; Lysenko, I.; Senior, R.A.; Börger, L.; Bennett, D.J.; Choimes, A.; Collen, B.; et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 2015, 520, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raven, P.H.; Wagner, D.L. Agricultural intensification and climate change are rapidly decreasing insect biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buick, R. Precision agriculture: an integration of information technologies with farming. Proc. New Zealand Plant Prot. Conf. 1997, 50, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Han, L.; Su, D. Comparison of Water Distribution Characteristics for Two Kinds of Sprinklers Used for Center Pivot Irrigation Systems. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Su, D. Alfalfa Water Use and Yield under Different Sprinkler Irrigation Regimes in North Arid Regions of China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heroldová, M.; Tkadlec, E. Harvesting behaviour of three central European rodents: Identifying the rodent pest in cereals. Crop. Prot. 2011, 30, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makundi, R.H.; Oguge, O.; Mwanjabe, P.S. Rodent Pest Management in East Africa - An Ecological Approach. In Proceedings of the Ecologically-based management of rodent pests; Singleton, G.R., Hinds, L.A., Leirs, H., Eds.; ACIAR: Canberra, Australia, 1999; pp. 460–476. [Google Scholar]

- Stenseth, N.C.; Leirs, H.; Skonhoft, A.; Davis, S.A.; Pech, R.P.; Andreassen, H.P.; Singleton, G.R.; Lima, M.; Machang'U, R.S.; Makundi, R.H.; et al. Mice, Rats, and People: The Bio-Economics of Agricultural Rodent Pests. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003, 1, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.A.; Salmon, T.P.; Schmidt, R.H.; Timm, R.M. Perceived damage and areas of needed research for wildlife pests of California agriculture. Integr. Zoöl. 2013, 9, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, T.P.; Lawrence, S.J. Anticoagulant Resistance in Meadow Voles (Microtus Californicus). In Proceedings of the 22nd Vertebrate Pest Conference; University of California: Davis, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, W.A.; Urban, D.J. Potential Risks of Nine Rodenticides to Birds and Nontarget Mammals: A Comparative Approach; US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances: Washington, DC, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rattner, B.A.; Lazarus, R.S.; Elliott, J.E.; Shore, R.F.; Brink, N.v.D. Adverse Outcome Pathway and Risks of Anticoagulant Rodenticides to Predatory Wildlife. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 8433–8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Perea, J.J.; Mateo, R. Secondary Exposure to Anticoagulant Rodenticides and Effects on Predators. In Emerging Topics in Ecotoxicology; van den Brink, N., Elliott, J., Shore, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG, 2018; Vol. 5, pp. 159–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; de Groot, R.; Lomas, P.L.; Montes, C. The history of ecosystem services in economic theory and practice: From early notions to markets and payment schemes. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, A.; Messina, F. Attitudes towards organic foods and risk/benefit perception associated with pesticides. Food Qual. Prefer. 2003, 14, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekercioglu, Ç.H.; Wenny, D.G.; Whelan, C.J. Why Birds Matter: Avian Ecological Function and Ecosystem Services; University of Chicago Press, 2016; ISBN 978-0-226-38277-7. [Google Scholar]

- Meyrom, K.; Motro, Y.; Leshem, Y.; Aviel, S.; Izhaki, I.; Argyle, F.; Charter, M. Nest-Box use by the Barn OwlTyto albain a Biological Pest Control Program in the Beit She'an Valley, Israel. Ardea 2009, 97, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O.; Nir, S.; Leshem, Y.; Meyrom, K.; Aviel, S.; Charter, M.; Roulin, A.; Izhak, I. Three Decades of Satisfied Israeli Farmers: Barn Owls (Tyto alba) as Biological Pest Control of Rodents. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; Van Vuren, D.; Ingels, C. Are barn owls a biological control for gophers? Evaluating effectiveness in vineyards and orchards. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 1998, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. Are Barn Owls (Tyto Alba) Biological Controllers of Rodents in the Everglades Agricultural Area? MSc thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kross, S.M.; Bourbour, R.P.; Martinico, B.L. Agricultural land use, barn owl diet, and vertebrate pest control implications. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 223, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raid, R. Use of Barn Owls for Sustainable Rodent Control in Agricultural Areas. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 2012, 366–369. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, C.A.; Johnson, M.D. Multi-scale analysis of barn owl nest box selection on Napa Valley vineyards. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 247, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Carlino, J.E.; Chavez, S.D.; Wang, R.; Cortez, C.; Montenegro, L.M.E.; Duncan, D.; Ralph, B. Balancing model specificity and transferability: Barn owl nest box selection. J. Wildl. Manag. 2024, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontzorlos, V.; Cain, S.; Leshem, Y.; Spiegel, O.; Motro, Y.; Bloch, I.; Cherkaoui, S.I.; Aviel, S.; Apostolidou, M.; Christou, A.; et al. Barn Owls as a Nature-Based Solution for Pest Control: A Multinational Initiative Around the Mediterranean and Other Regions. Conservation 2024, 4, 627–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, A.; Jareño, D.; Arroyo, L.; Viñuela, J.; Arroyo, B.; Mougeot, F.; Luque-Larena, J.J.; Fargallo, J.A. Avian predators as a biological control system of common vole (Microtus arvalis) populations in north-western Spain: experimental set-up and preliminary results. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 69, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M.; Izhaki, I.; Bouskila, A.; Leshem, Y.; Penteriani, V. The Effect of Different Nest Types on the Breeding Success of Eurasian Kestrels (Falco tinnunculus) in a Rural Ecosystem. J. Raptor Res. 2007, 41, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M.; Izhaki, I.; Leshem, Y. Predation or facilitation? An experimental assessment of whether generalist predators affect the breeding success of passerines. J. Ornithol. 2010, 152, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M.; Izhaki, I.; Leshem, Y. Does Nest Basket Size Affect Breeding Performance of Long-eared Owls and Eurasian Kestrels? J. Raptor Res. 2010, 44, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shave, M.E.; Shwiff, S.A.; Elser, J.L.; Lindell, C.A.; Siriwardena, G. Falcons using orchard nest boxes reduce fruit-eating bird abundances and provide economic benefits for a fruit-growing region. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 2451–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.C.; Baldwin, R.A.; Johnson, M.D. Are Barn Owls a Cost-Effective Alternative to Lethal Trapping? Implications for Rodent Pest Management. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference; 2024; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A.; Johnson, M. Evaluating the Use of Barn Owl Nest Boxes for Rodent Pest Control in Winegrape Vineyards in Napa Valley. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 2022, 30, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Askham, L.R. Effect of Artificial Perches and Nests in Attracting Raptors to Orchards. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fourteenth Vertebrate Pest Conference 1990.

- Clucas, B.; Smith, T.N.; Carlino, J.; Daniel, S.; Davis, A.; Douglas, L.; Gulak, M.M.; Livingstone, S.L.K.; Lopez, S.; Kerr, K.J.; et al. A novel method using camera traps to record effectiveness of artificial perches for raptors. Calif. Fish Wildl. J. 2020, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-Y.; Lin, H.-S.; Huang, Z.-L.; Choi, W.-S.; Wang, W.-I.; Sun, Y.-H. Perch-Mounted Camera Traps Record Predatory Birds in Farmland. J. Raptor Res. 2022, 56, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, B.; Twigg, L.; Korn, T.; Nicol, H. The use of artifical perches to increase predation on house mice (mus domesticus) by raptors. Wildl. Res. 1994, 21, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, L.M.; Crait, J.R.; Edge, W.D.; Wang, G. Response of American kestrels and gray-tailed voles to vegetation height and supplemental perches. Can. J. Zoöl. 2001, 79, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O Wolff, J.; Fox, T.; Skillen, R.R.; Wang, G. The effects of supplemental perch sites on avian predation and demography of vole populations. Can. J. Zoöl. 1999, 77, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.L.; Kross, S.M. Effects of Perch Location on Wintering Raptor Use of Artificial Perches in a California Vineyard. J. Raptor Res. 2018, 52, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olenec, Z.D.D.; Ovak, D.A.K.I.N. Winter Prey of the Long-Eared Owl (Asio Otus ) in Northern Croatia. Nat. Croat. Period. Musei Hist. Nat. Croat. 2010, 19, 1998–2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zagorski, M.E.; Swihart, R.K. Killing time in cover crops? Artificial perches promote field use by raptors. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2020, 177, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteagudo, N.; Benayas, J.M.R.; Meltzer, J.; Rebollo, S. Assessing the influence of raptors on grape-eating birds in a Mediterranean vineyard. Crop. Prot. 2023, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumstein, D.T. Flight-Initiation Distance in Birds Is Dependent on Intruder Starting Distance. J. Wildl. Manag. 2003, 67, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teel, T.L.; Manfredo, M.J. Understanding the Diversity of Public Interests in Wildlife Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machar, I.; Harmacek, J.; Vrublova, K.; Filippovova, J.; Brus, J. Biocontrol of Common Vole Populations by Avian Predators Versus Rodenticide Application. Pol. J. Ecol. 2017, 65, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, K.S.; Gilbert, S.L.; Brown, C.L.; Hatfield, M.; Hanson, L. Unmanned aircraft systems in wildlife research: current and future applications of a transformative technology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishodia, R.P.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, S.K. Applications of Remote Sensing in Precision Agriculture: A Review. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.; Borralho, N.; Cabral, P.; Caetano, M. Recent Advances in Forest Insect Pests and Diseases Monitoring Using UAV-Based Data: A Systematic Review. Forests 2022, 13, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aszkowski, P.; Kraft, M.; Drapikowski, P.; Pieczyński, D. Estimation of corn crop damage caused by wildlife in UAV images. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 2505–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshet, D.; Brook, A.; Malkinson, D.; Izhaki, I.; Charter, M. The Use of Drones to Determine Rodent Location and Damage in Agricultural Crops. Drones 2022, 6, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Du, J.; Zhu, X.; Gao, X. Research on Grassland Rodent Infestation Monitoring Methods Based on Dense Residual Networks and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2023, 89, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzy, H.; Charter, M.; Bonfante, A.; Brook, A. How the Small Object Detection via Machine Learning and UAS-Based Remote-Sensing Imagery Can Support the Achievement of SDG2: A Case Study of Vole Burrows. Remote. Sens. 2021, 13, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M.; Rozman, G. The Importance of Nest Box Placement for Barn Owls (Tyto alba). Animals 2022, 12, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ramady, H.; Abdalla, N.; Kovacs, S.; Domokos-Szabolcsy, É.; Bákonyi, N.; Fari, M.; Geilfus, C.-M. Alfalfa Growth under Changing Environments: An Overview. Environ. Biodivers. Soil Secur. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovic, J.; Sokolovic, D.; Markovic, J. Alfalfa-most important perennial forage legume in animal husbandry. 2009, 25, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Wallander, J.; Isaksson, D. Predator perches: a visual search perspective. Funct. Ecol. 2009, 23, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briner, T.; Nentwig, W.; Airoldi, J.-P. Habitat quality of wildflower strips for common voles (Microtus arvalis) and its relevance for agriculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 105, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, S. Reducing sodium fluoroacetate and fluoroacetamide concentrations in field rodent baits. Phytoparasitica 1995, 23, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, S.; Keidar, H. Checklist of vertebrate damage to agriculture in Israel. Crop. Prot. 1993, 12, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinova, M.; Jarmer, T.; Brook, A. Spectral data source effect on crop state estimation by vegetation indices. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, A. Renewal of burrows by the common vole as the indicator of its numbers. Mammal Res. 1974, 19, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, M.A.; Greenfield, R.; Tesfamichael, S. Wetland Assessment Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Photogrammetry. In Proceedings of the International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences - ISPRS Archives; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, P.J. Canopy reflectance, photosynthesis and transpiration. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 1985, 6, 1335–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J.A.; Serrano, L.; Surfus, J.S. The photochemical reflectance index: an optical indicator of photosynthetic radiation use efficiency across species, functional types, and nutrient levels. Oecologia 1997, 112, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuelas, J.; Baret, F.; Filella, I. Semi-Empirical Indices to Assess Carotenoids/Chlorophyll a Ratio from Leaf Spectral Reflectance. Photosynthetica 1995, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Nagari, M.; Charter, M. Comparing Insect Predation by Birds and Insects in an Apple Orchard and Neighboring Unmanaged Habitat: Implications for Ecosystem Services. Animals 2023, 13, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, J.; Sánchez, N.; García-Ariza, C.; Pérez-Sánchez, R.; Charfolé, F.; Caminero-Saldaña, C. Classification of airborne multispectral imagery to quantify common vole impacts on an agricultural field. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 2316–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, W.; Li, M.; Liu, B.; Zhao, S.; Hu, M.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Shi, Y.; Sun, H.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the nutritional value and contaminants of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in China. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1539462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, S.; Keidar, H. Assessment of Toxic Bait Efficacy in Field Trials by Counts of Burrow Openings. Proc. Vertebr. Pest Conf. 1994, 16, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, S. Toxicity of sodium fluoroacetate and zinc phosphide wheat grain baits to Microtus guentheri and Meriones tristrami. EPPO Bull. 1991, 21, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.A.; Abbo, B.G.; Goldade, D.A. Comparison of mixing methods and associated residual levels of zinc phosphide on cabbage bait for rodent management. Crop. Prot. 2018, 105, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Baldwin, R.; Halbritter, H.; Meinerz, R.; Snell, L.K.; Orloff, S.B. Efficacy and nontarget impact of zinc phosphide-coated cabbage as a ground squirrel management tool. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.; Meinerz, R.; Shiels, A. Efficacy of Goodnature A24 self-resetting traps and diphacinone bait for controlling black rats (Rattus rattus) in citrus orchards. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2022, 13, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witmer, G.W.; Moulton, R.S.; Baldwin, R.A. An efficacy test of cholecalciferol plus diphacinone rodenticide baits for California voles (Microtus californicusPeale) to replace ineffective chlorophacinone baits. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2014, 60, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M.; Izhaki, I.; Meyrom, K.; Motro, Y.; Leshem, Y. Diets of Barn Owls Differ in the Same Agricultural Region. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2009, 121, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corl, A.; Charter, M.; Rozman, G.; Toledo, S.; Turjeman, S.; Kamath, P.L.; Getz, W.M.; Nathan, R.; Bowie, R.C. Movement ecology and sex are linked to barn owl microbial community composition. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 1358–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M.; Izhaki, I.; Leshem, Y.; Meyrom, K.; Roulin, A. Relationship between diet and reproductive success in the Israeli barn owl. J. Arid. Environ. 2015, 122, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M.; Izhaki, I.; Roulin, A. The relationship between intra–guild diet overlap and breeding in owls in Israel. Popul. Ecol. 2018, 60, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shlagman, L.; Hellwing, S.; Yom-Tov, Y. The Biology of the Levant Vole, Microtus Guentheri in Israel II. The Reproduction and Growth in Captivity. Zeit. Zaugeteirkd. 1984, 49, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Shlagman, L.; Yom-Tov, Y.; Hellwing, S. The Biology of the Levant Vole Microtus Guentheri in Israel. I. Population Dynamics in the Field. Zeit. Zaugetierkd. 1984, 49, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, L. Diel Activity Rhythms in the Levant Vole, Microtus Guentheri. Isr. J. Zool. 1988, 35, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, G.; Izhaki, I.; Roulin, A.; Charter, M. Movement ecology, breeding, diet, and roosting behavior of barn owls (Tyto alba) in a transboundary conflict region. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Castañeda, X.; E Huysman, A.; Johnson, M.D. Barn Owls select uncultivated habitats for hunting in a winegrape growing region of California. Condor 2021, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilk, O.; Orchan, Y.; Charter, M.; Ganot, N.; Toledo, S.; Nathan, R.; Assaf, M. Ergodicity Breaking in Area-Restricted Search of Avian Predators. Phys. Rev. X 2022, 12, 031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, S.; Orchan, Y.; Shohami, D.; Charter, M.; Nathan, R. Physical-Layer Protocols for Lightweight Wildlife Tags with Internet-of-Things Transceivers. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 19th International Symposium on “A World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks” (WoWMoM), Chania, Greece, 12–15 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.S.; Laundré, J.W.; Gurung, M. The Ecology of Fear: Optimal Foraging, Game Theory, and Trophic Interactions. J. Mammal. 1999, 80, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, K.M.; Cherry, M.J.; Gilbert, S.L.; Kohl, M.T.; Larson, C.L.; Newsome, T.M.; Prugh, L.R.; Suraci, J.P.; Young, J.K.; Smith, J.A. An applied ecology of fear framework: linking theory to conservation practice. Anim. Conserv. 2020, 24, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.E. The Natural Control of Animal Populations. J. Anim. Ecol. 1949, 18, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Some Characteristics of Simple Types of Predation and Parasitism. Can. Èntomol. 1959, 91, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Erlinge, S. Influence of Predation on Rodent Populations. Oikos 1977, 29, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, C.; de Roos, A.M. Effects of vole fluctuations on the population dynamics of the barn owl Tyto alba. Acta Biotheor. 2007, 55, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | Burrows | NDVI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | |

| Hunting Perches (n=15) | 11.1 | 12.6 | 0.884 | 0.017 |

| Rodenticide (n=15) | 11.1 | 11.8 | 0.886 | 0.017 |

| Control (n=15) | 11.4 | 17.0 | 0.883 | 0.015 |

| Kruskal-Wallis | H = 0.54, df = 2, P = 0.76 | H = 0.15, df = 2, P = 0.93 | ||

| Time | Behavior | TP | FP | FN | Recall | Precision |

| Day | Flying | 11 | 4 | 2 | 0.85 | 0.73 |

| Hovering | 14 | 2 | 2 | 0.88 | 0.88 | |

| Perching | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Night | Flying | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.75 |

| Perching | 41 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Number of visits | Perching | Hovering | Flying |

| Hunting Perches (n=13) | 24.46 ± 4.64 | 2.69 ± 1.74 | 17.54 ± 4.12 |

| Rodenticide (n=11) | 0.00 ± 0.17 | 1.64 ± 0.59 | 24.82 ± 4.92 |

| Control (n=8) | 0.00 ± 0.17 | 1.13 ± 0.72 | 21.75 ± 5.23 |

| Duration | |||

| Hunting Perches (n=13) | 116.96 ± 25.97 | 0.99 ± 0.67 | 2.93 ± 1.05 |

| Rodenticide (n=11) | 0.00 ± 0.17 | 0.44 ± 0.17 | 2.19 ± 0.41 |

| Control (n=8) | 0.00 ± 0.17 | 0.28 ± 0.21 | 2.67 ± 1.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).