Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

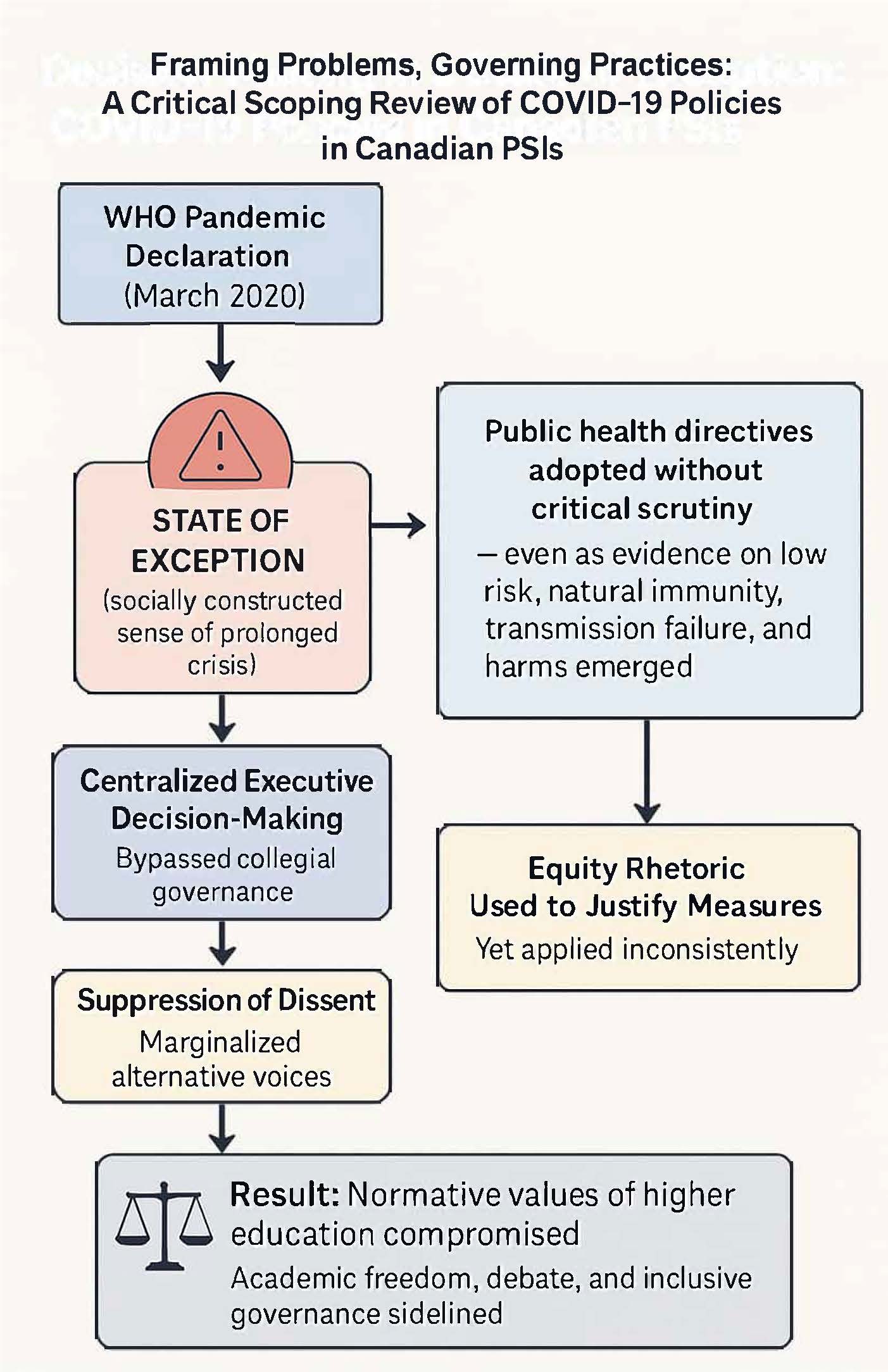

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Goal of the Review and Review Questions

- a)

- Problem representation and related issues – What was/is the problem represented to be in the COVID-19 policy response in Canadian PSIs? What evidence supported this problem representation? What was the alignment of institutional policies with policies implemented by public health authorities? What was left unproblematic in this problem representation?

- b)

- Decision-making process and related issues – What institutional or individual social actors were responsible for making decisions concerning the perceived problem and what processes of consultation, if any, were carried out to arrive at a given decision? What were the external influences, if any, in the decision-making process?

- c)

- Equity, diversity, inclusivity, and bioethical principles – What equity, diversity, inclusivity, and bioethical criteria were (or not) considered?

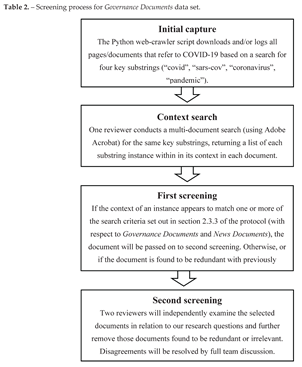

2.3. Data Type, Selection, and Charting

| Category | Data description | Data source | Document count | URLs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal documents | Documents containing information on legal decisions affecting Canadian postsecondary institutions. |

Canadian Legal Information Institute: Non-profit database of legal documents with information on legal decisions affecting Canadian postsecondary institutions. |

Total: 22 | https://www.canlii.org/en |

| Association documents | Publicly available communications from faculty, staff, and student associations. |

Main websites of faculty, staff, and student associations (e.g., University of Toronto Faculty Association) | Total: 127 37 UBC 30 UofT 28 McMaster 27 UofA 4 CUPE 1 Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance |

https://www.utfa.org/ |

| Governance documents |

Publicly available agendas, minutes, reports, and motion records of meetings of decision-making academic bodies. |

Websites of five universities from across Canada, selected for strategic reasons (scientific leadership; policy influence; contrasting geographical location; diverse ideological orientation; policy choices): 1) University of Toronto; 2) McMaster University; 3) Redeemer University; 4) University of Alberta; 5) University of British Columbia |

Total: 395 168 UofT 103 UofA 87 McMaster 32 UBC 5 Redeemer |

https://www.utoronto.ca/ https://www.mcmaster.ca/ https://www.redeemer.ca/ https://www.ualberta.ca/index.html https://www.ubc.ca/ |

2.4. Statement on Reflexivity

3. Findings

3.1. Problem Representation and Related Issues

3.2. Decision-Making Process and Related Issues

3.3. Equity, Diversity, Inclusivity, and Bioethical Principles

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

CRediT Author Statement

Ethics

Conflicts of Interests

Funding

Acknowledgements

References

- Abou-Rabia, M. , Harris, S., Hurley, A., Oladejo, E., Sriharan, B., & Quinn, E. (2021). Policy Paper: Responding to COVID-19, /: Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance. https, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, G. (with Dani, V.). (2021). Where Are We Now? The Epidemic as Politics. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Alwan, N. A., Burgess, R. A., Ashworth, S., Beale, R., Bhadelia, N., Bogaert, D., Dowd, J., Eckerle, I., Goldman, L. R., Greenhalgh, T., Gurdasani, D., Hamdy, A., Hanage, W. P., Hodcroft, E. B., Hyde, Z., Kellam, P., Kelly-Irving, M., Krammer, F., Lipsitch, M., … Ziauddeen, h. (2020). Scientific consensus on the COVID-19 pandemic: We need to act now. The Lancet, 396(10260), e71–e72. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N., Stowe, J., Kirsebom, F., Toffa, S., Rickeard, T., Gallagher, E., Gower, C., Kall, M., Groves, N., O’Connell, A.-M., Simons, D., Blomquist, P. B., Zaidi, A., Nash, S., Iwani Binti Abdul Aziz, N., Thelwall, S., Dabrera, G., Myers, R., Amirthalingam, G., … Lopez Bernal, J. (2022). Covid-19 Vaccine Effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) Variant. The New England Journal of Medicine, NEJMoa2119451. [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H. , & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. [CrossRef]

- Association of Academic Staff University of Alberta. (2021, August 20). Update on COVID-19 measures and member rights. Association of Academic Staff University of Alberta. Available online: https://aasua.ca/Web/Web/Communications/President-s-Message-Articles/Update-on-COVID-19-measures-and-member-rights.aspx.

- Association of Academic Staff University of Alberta. (2022a, January 20). Remote teaching extended, bargaining and students. Association of Academic Staff University of Alberta. Available online: https://aasua.ca/Web/Web/Communications/President-s-Message-Articles/Remote-teaching-extended-bargaining-and-students.aspx.

- Association of Academic Staff University of Alberta. (2022b, November 21). AASUA requests mask mandate. Association of Academic Staff University of Alberta. Available online: https://aasua.ca/Web/Communications/President-s-Message-Articles/AASUA-requests-mask-mandate.aspx.

- Association of Administrative and Professional Staff at UBC. (2021a). On-going Remote Work Arrangement Conversations for AAPS Members. Association of Administrative and Professional Staff at UBC. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210925185232/https://aaps.ubc.ca/member/news/going-remote-work-arrangement-conversations-aaps-members.

- Association of Administrative and Professional Staff at UBC. (2021b, August 9). AAPS Memo to Members: UBC Reopening. Association of Administrative and Professional Staff at UBC. Available online: https://aaps.ubc.ca/member/news/aaps-memo-members-ubc-reopening.

- Association of Administrative and Professional Staff at UBC. (2021c, August 20). AAPS Memo to Members: Follow-up to our UBCreopening memo and an opportunity to share your concerns, /: Administrative and Professional Staff at UBC. https://web.archive.org/web/20210820223658/https, 20 August 2021.

- Bacchi, C. (2012). Why Study Problematizations? Making Politics Visible. Open Journal of Political Science, Vol.02No.01, 8. [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, C. (2016). Questioning How “Problems” Are Constituted in Policies. SAGE Open, 6(2), 2158244016653986. [CrossRef]

- Bardosh, K., Figueiredo, A. de, Gur-Arie, R., Jamrozik, E., Doidge, J., Lemmens, T., Keshavjee, S., Graham, J., & Baral, S. (2022). The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: Why mandates, passports, and segregated lockdowns may cause more harm than good. BMJ Global Health, 7(5), e008684.

- Battacharya, J., Gupta, S., & Kulldorff, M. (2020, November 25). Focused Protection. Great Barrington Declaration.

- Bavli, I., Sutton, B., & Galea, S. (2020). Harms of public health interventions against covid-19 must not be ignored. BMJ, 371, m4074. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 137–152. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G. A. (2009a). Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G. A. (2009b). Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Buchan, S. A., Seo, C. Y., Johnson, C., Alley, S., Kwong, J. C., Nasreen, S., Calzavara, A., Lu, D., Harris, T. M., Yu, K., & Wilson, S. E. (2022). Epidemiology of Myocarditis and Pericarditis Following mRNA Vaccination by Vaccine Product, Schedule, and Interdose Interval Among Adolescents and Adults in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Network Open, 5(6), e2218505. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J., & Pedersen, O. K. (2013). Coding In-depth Semistructured Interviews: Problems of Unitization and Intercoder Reliability and Agreement. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(3), 294–320. [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2020, August 8). Government of Canada funds 49 additional COVID-19 research projects – Details of the funded projects. Government of Canada. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/institutes-health-research/news/2020/03/government-of-canada-funds-49-additional-covid-19-research-projects-details-of-the-funded-projects.html.

- Canadian Union of Public Employees. (2019, January 29). The corporatization of post-secondary education. Canadian Union of Public Employees. Available online: https://cupe.ca/corporatization-post-secondary-education.

- Cao, S., Gan, Y., Wang, C., Bachmann, M., Wei, S., Gong, J., Huang, Y., Wang, T., Li, L., Lu, K., Jiang, H., Gong, Y., Xu, H., Shen, X., Tian, Q., Lv, C., Song, F., Yin, X., & Lu, Z. (2020). Post-lockdown SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid screening in nearly ten million residents of Wuhan, China. Nature Communications, 11(1), 5917. [CrossRef]

- CBC News. (2022, 11). Ontario removes more than 400 deaths from official COVID-19 count. CBC. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/covid19-ontario-march-11-1.6381330.

- CDC. (2024, April 4). Clinical Guidance for COVID-19 Vaccination | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/interim-considerations-us.html.

- CDC COVID-19 Vaccine Breakthrough Case Investigations Team. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine Breakthrough Infections Reported to CDC — United States, January 1–April 30, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 70. [CrossRef]

- Chao, M. J., Menon, C., & Elgendi, M. (2022). Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on the menstrual cycle. Frontiers in Medicine, 9, 1065421.

- Chaufan, C. (2023). Is Covid-19 “vaccine uptake” in postsecondary education a “problem”? A critical policy inquiry. Health, 13634593231204169. [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C., & Hemsing, N. (2023). In the name of health and illness: An inquiry into Covid-19 vaccination policy in postsecondary education in Canada. Journal of Research and Applied Medicine, 1(6), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C., Manwell, L., Gabbay, B., Heredia, C., & Daniels, C. (2023). Appraising the decision-making process concerning COVID-19 policy in postsecondary education in Canada: A critical scoping review protocol. AIMS Public Health, 10(4), Article publichealth-10-04-059. [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C., Manwell, L., Heredia, C., & McDonald, J. (2025). COVID-19 Vaccination and Autoimmune Disorders: A Scoping Review (2025060831). [CrossRef]

- Chemaitelly, H., Ayoub, H. H., AlMukdad, S., Coyle, P., Tang, P., Yassine, H. M., Al-Khatib, H. A., Smatti, M. K., Hasan, M. R., Al-Kanaani, Z., Al-Kuwari, E., Jeremijenko, A., Kaleeckal, A. H., Latif, A. N., Shaik, R. M., Abdul-Rahim, H. F., Nasrallah, G. K., Al-Kuwari, M. G., Butt, A. A., … Abu-Raddad, L. J. (2022). Protection from previous natural infection compared with mRNA vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 in Qatar: A retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Microbe, 3(12), e944–e955. [CrossRef]

- Chemaitelly, H., Nagelkerke, N., Ayoub, H. H., Coyle, P., Tang, P., Yassine, H. M., Al-Khatib, H. A., Smatti, M. K., Hasan, M. R., Al-Kanaani, Z., Al-Kuwari, E., Jeremijenko, A., Kaleeckal, A. H., Latif, A. N., Shaik, R. M., Abdul-Rahim, H. F., Nasrallah, G. K., Al-Kuwari, M. G., Butt, A. A., … Abu-Raddad, L. J. (2022). Duration of immune protection of SARS-CoV-2 natural infection against reinfection. Journal of Travel Medicine, 29(8), taac109. [CrossRef]

- Childs, J., & Taylor, Z. W. (2024). Returning at Any Cost? How Black College Students Feel Toward COVID Vaccines and Institutional Mandates. Journal of Black Studies, 55(5), 400–417. [CrossRef]

- CityNews Kitchener Staff. (2022, March 25). Nearly 50 people fired for not complying with UW’s vaccine mandate. CityNews. Available online: https://kitchener.citynews.ca/2022/03/25/nearly-50-people-fired-for-not-complying-with-uws-vaccine-mandate-5197789/.

- Columbia University School of Professional Studies. (2024, January 2). The Real Impact of Fake News: The Rise of Political Misinformation—and How We Can Combat Its Influence. Available online: https://sps.columbia.edu/news/real-impact-fake-news-rise-political-misinformation-and-how-we-can-combat-its-influence.

- Confederation of Alberta Faculty Associations. (2021, August 17). Alberta’s Faculty Call for Safe, Scientifically Based, Return to Campus Plans. Available online: https://cafa-ab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/PressReleaseCampusReopenings.pdf.

- Confederation of University Faculty Associations of British Columbia. (2021, August 5). CUFA BC Calls for Institutional Autonomy Over Safe Campus Decisions. CUFA BC; Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210805205326/https://cufa.bc.ca/cufa-bc-letter-to-aest-minister-over-institutional-autonomy-and-safe-campus-decisions/.

- Costa, Love, Badowich and Mandekic v. Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology, 2022 ONSC 5111 (September 12, 2022). Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2022/2022onsc5111/2022onsc5111.pdf.

- Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. (nd). Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. CMEC.

- Council of Ontario Medical Officers of Health. (2021a, August 24). Vaccine Policies at Ontario Universities and Colleges. COMOH. Available online: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.alphaweb.org/resource/collection/D927A028-023E-4413-B438-86101BEFB7B7/COMOH_Vaccine_Policies_at_Ontario_Universities_and_Colleges_240821.pdf.

- . Council of Ontario Medical Officers of Health. (2021b, August 26). Vaccine Policies at Ontario Universities and Colleges (Updated August 26). COMOH. Available online: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.alphaweb.org/resource/collection/D927A028-023E-4413-B438-86101BEFB7B7/COMOH_Vaccine_Policies_at_Ontario_Universities_and_Colleges_260821.pdf.

- Council of Ontario Universities. (2022, March 11). COU Statement: COVID-19 Vaccination and Masking Policies. Ontario’s Universities. Available online: https://ontariosuniversities.ca/news/cou-statement-covid-19-vaccination-and-masking-policies/.

- Council of Ontario Universities. (n.d.). Home—The Council of Ontario Universities. Council of Ontario Universities; Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20250503060125/https://cou.ca/.

- COVID-19 Forecasting Team. (2022). Variation in the COVID-19 infection–fatality ratio by age, time, and geography during the pre-vaccine era: A systematic analysis. The Lancet, 399(10334), 1469–1488. [CrossRef]

- Crljen, J. (2023, December 6). Medicine by Design and CCRM announce strategic alliance to bolster Canada’s globally-leading position in regenerative medicine [University of Toronto]. Medicine by Design. Available online: https://mbd.utoronto.ca/news/med-by-design-ccrm-alliance/.

- CUPE 3261. (2021, August 30). U of T Vaccine Policy & Your Rights. CUPE 3261. Available online: https://3261.cupe.ca/2021/08/30/u-of-t-vaccine-policy-your-rights/.

- CUPE 3902. (2021a). COVID-19: Updates & Resources. CUPE 3902. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230927193118/https://www.cupe3902.org/covid-19-updates-resources/.

- CUPE 3902. (2021b, October 8). Vaccine Policies FAQ. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20211015202517/https://cupe3902.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Vaccine-Policies-FAQ.pdf.

- CUPE 3902. (2023, January 29). DEFY EXPECTATIONS: A Fair and Safe U of T in 2022. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230129010144/https://www.cupe3902.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Joint-Letter-Defy-Expectations-in-2022.pdf.

- CUPE 3906. (2021, September 29). COVID back-to-work questions. CUPE 3906. Available online: https://cupe3906.org/2021/09/29/covid-back-to-work-questions/.

- Da-Ré, G. (2021). MSU President Transition Report. McMaster Students Union. Available online: https://msumcmaster.ca/app/uploads/2021/06/MSU-President-TR-Denver-For-Distribution.docx.

- Department of Homeland Security. (2019). Combatting Targeted Disinformation Campaigns; A whole-of-society issue (p. 28). DHS. Available online: https://www.hsdl.org/c/view?docid=845040.

- Derwand, R., Scholz, M., & Zelenko, V. (2020). COVID-19 outpatients: Early risk-stratified treatment with zinc plus low-dose hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: a retrospective case series study. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 56(6), 106214. [CrossRef]

- Dewan, G. (2021, November 22). Shown the door for not taking a shot; Western University student expelled. CBC News. Available online: https://www.ctvnews.ca/london/article/shown-the-door-for-not-taking-a-shot-western-university-student-expelled/.

- Do, L. (2020, March 20). “Early and bold interventions are best”: U of T researcher on simulating a pandemic response. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/early-and-bold-interventions-are-best-u-t-researcher-simulating-pandemic-response.

- Donovan, M. (2023, January 20). New inhaled COVID-19 vaccine receives more than $8M for next stage of human trials. Brighter World - McMaster University. Available online: https://brighterworld.mcmaster.ca/articles/new-inhaled-covid-19-vaccine-receives-more-than-8m-for-next-stage-of-human-trials/.

- Doshi, P. (2020). Will covid-19 vaccines save lives? Current trials aren’t designed to tell us. BMJ, m4037. [CrossRef]

- Drisko, J. W. (2025). Transferability and Generalization in Qualitative Research. Research on Social Work Practice, 35(1), 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Edwardson, L. (2021, October 4). 11 Mount Royal University students deregistered for not declaring vaccination status. CBC News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/mru-students-deregistered-vaccination-status-1.6199073.

- Evans, C., & Bhangu, E. (2021, July 23). Open Letter to UBC on student concerns about returning to campus. Available online: https://www.ams.ubc.ca/student-life/stories/open-letter-to-ubc-on-student-concerns-about-returning-to-campus/.

- Faksova, K., Walsh, D., Jiang, Y., Griffin, J., Phillips, A., Gentile, A., Kwong, J. C., Macartney, K., Naus, M., Grange, Z., Escolano, S., Sepulveda, G., Shetty, A., Pillsbury, A., Sullivan, C., Naveed, Z., Janjua, N. Z., Giglio, N., Perälä, J., … Hviid, A. (2024). COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine. [CrossRef]

- Farrar, D., & Tighe, S. (2022a, March 25). McMaster to pause vaccine and mask requirements from May 1: A letter from the President and Provost. Daily News. Available online: https://dailynews.mcmaster.ca/articles/mcmaster-to-pause-vaccine-and-mask-requirements-from-may-1-a-letter-from-the-president-and-provost/.

- Farrar, D., & Tighe, S. (2022b, August 24). Message from the President and Provost regarding the fall 2022 term. Daily News. Available online: https://dailynews.mcmaster.ca/articles/message-from-the-president-and-provost-regarding-the-fall-2022-term/.

- Fiorentino, D. (2024, March 5). McMaster and Celesta partner to accelerate deep tech innovation and commercialization [McMaster University]. Brighter World - Research Focused on the Health and Wellbeing of All. Available online: https://brighterworld.mcmaster.ca/articles/mcmaster-celesta-partnership-for-deep-tech-innovation-commercialization/.

- Flanagan, B. (2021, August 6). Your Safety is Our Top Priority: A Message from President Flanagan. The Quad. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/the-quad/2021/08/your-safety-is-our-top-priority.html.

- Flanagan, B. (2022a, February 10). From the President’s Desk: Returning safely to campus on February 28. The Quad. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/the-quad/2022/02/from-the-presidents-desk-returning-safely-to-campus-on-february-28.html.

- Flanagan, B. (2022b, February 17). From the President’s Desk: Suspending the Vaccination Directive and CampusReady program. The Quad. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/the-quad/2022/02/from-the-presidents-desk-suspending-the-vaccination-directive-and-campusready-program.html.

- Fletcher, T. (2021a, August 23). Announcement of BC Vaccine Card for specific activities. UBC News. Available online: https://news.ubc.ca/2021/08/announcement-of-bc-vaccine-card-for-specific-activities/.

- Fletcher, T. (2021b, August 26). UBC implements vaccine declaration and rapid testing for COVID-19. UBC News. Available online: https://news.ubc.ca/2021/08/ubc-implements-vaccine-declaration-and-rapid-testing-for-covid-19/.

- Foster, A. (2021, March 22). Dual Delivery Maintains Relational Learning. Resound. Available online: https://www.redeemer.ca/resound/dual-delivery-maintains-relational-learning/.

- Fraiman, J., Erviti, J., Jones, M., Greenland, S., Whelan, P., Kaplan, R. M., & Doshi, P. (2022). Serious adverse events of special interest following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in randomized trials in adults. Vaccine, 40(40), 5798–5805. [CrossRef]

- Gazit, S., Shlezinger, R., Perez, G., Lotan, R., Peretz, A., Ben-Tov, A., Herzel, E., Alapi, H., Cohen, D., Muhsen, K., Chodick, G., & Patalon, T. (2022). Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Naturally Acquired Immunity versus Vaccine-induced Immunity, Reinfections versus Breakthrough Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 75(1), e545–e551. [CrossRef]

- GDI. (n.d.). The Global Disinformation Index. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- Georgian College v. Ontario Public Service Employees’ Union, Local 349, 2021 CanLII 150911 (ON LA) (May 16, 2021).

- Giroux, D., Karmis, D., & Rouillard, C. (2015). Between the Managerial and the Democratic University: Governance Structure and Academic Freedom as Sites of Political Struggle. Studies in Social Justice, 9(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Glover, R. E., van Schalkwyk, M. C. I., Akl, E. A., Kristjannson, E., Lotfi, T., Petkovic, J., Petticrew, M. P., Pottie, K., Tugwell, P., & Welch, V. (2020). A framework for identifying and mitigating the equity harms of COVID-19 policy interventions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 128, 35–48. [CrossRef]

- Goedegebuure, L., & Hayden, M. (2007). Overview: Governance in higher education—concepts and issues. Higher Education Research & Development, 26(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Goudreault, Z. (2024, April 26). Le controversé professeur Patrick Provost conteste son congédiement de l’Université Laval. Le Devoir. Available online: https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/education/811751/controverse-professeur-patrick-provost-conteste-congediement-universite-laval.

- Government of British Columbia. (2022, March 10). B.C. takes next step in balanced plan to lift COVID-19 restrictions. BC Gov News. Available online: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022HLTH0081-000324.

- Government of Ontario. (2021, September 2). Instructions issued by the Office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health. Ministry of Health. Available online: https://ontariosuniversities.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/CMOH-Instructions-EN.pdf.

- Graduate Student Society of UBC Vancouver. (2022, January 21). A Joint Letter Addressing Student Safety as Omicron Surges. Graduate Student Society of UBC Vancouver. Available online: https://gss.ubc.ca/joint-letter-student-safety-omicron/.

- Hawke v. Western University, 2022 ONSC 5243 (CanLII) (September 23, 2022). Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2022/2022onsc5243/2022onsc5243.pdf.

- Jabakhanji, S. (2020, March 13). Toronto universities, colleges suspend all on-campus classes amid COVID-19 pandemic. CBC News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-universities-covid-19-1.5497047.

- Jones, G. A., Shanahan, T., & Goyan, P. (2001). University governance in Canadian higher education. Tertiary Education and Management, 7(2), 135–148. [CrossRef]

- Kalvapalle, R. (2020a, March 31). Nine U of T researchers receive federal grants for COVID-19 projects. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/nine-u-t-researchers-receive-federal-grants-covid-19-projects.

- Kalvapalle, R. (2020b, July 7). New U of T measure calls for non-medical masks or face coverings in indoor public spaces. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/new-u-t-measure-calls-non-medical-masks-or-face-coverings-indoor-public-spaces.

- Kalvapalle, R. (2020c, July 23). How U of T plans to keep everyone safe on campus this fall. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/how-u-t-plans-keep-everyone-safe-campus-fall.

- Kalvapalle, R. (2020d, August 31). U of T implements protocols to respond to COVID-19 cases on campus this fall. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-implements-protocols-respond-covid-19-cases-campus-fall.

- Kalvapalle, R. (2021a, June 8). U of T to require COVID-19 vaccinations for students living in residence. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-require-covid-19-vaccinations-students-living-residence.

- Kalvapalle, R. (2021b, July 29). U of T to require vaccination for high-risk activities, self-declaration of vaccination status. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-require-vaccination-high-risk-activities-self-declaration-vaccination-status.

- Kalvapalle, R. (2021c, December 15). U of T cancels in-person exams, delays in-person classes due to Omicron variant. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-cancels-person-exams-delays-person-classes-due-omicron-variant.

- Kalvapalle, R. (2022, January 19). U of T to increase in-person learning and activities in February. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-increase-person-learning-and-activities-february.

- Karlstad, Ø., Hovi, P., Husby, A., Härkänen, T., Selmer, R. M., Pihlström, N., Hansen, J. V., Nohynek, H., Gunnes, N., Sundström, A., Wohlfahrt, J., Nieminen, T. A., Grünewald, M., Gulseth, H. L., Hviid, A., & Ljung, R. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Myocarditis in a Nordic Cohort Study of 23 Million Residents. JAMA Cardiology. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, L., Cadegiani, F. A., Baldi, F., Lobo, R. B., Assagra, W. L. O., Proença, F. C., Kory, P., Hibberd, J. A., Chamie-Quintero, J. J., Kerr, L., Cadegiani, F. A., Baldi, F., Lobo, R., Sr, W. L. A., Sr, F. C. P., Kory, P., Hibberd, J. A., & Chamie-Quintero, J. J. (2022). Ivermectin Prophylaxis Used for COVID-19: A Citywide, Prospective, Observational Study of 223,128 Subjects Using Propensity Score Matching. Cureus, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Kompaniyets, L. (2021). Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020–March 2021. Preventing Chronic Disease, 20 March. [CrossRef]

- Kory, P., Meduri, G. U., Varon, J., Iglesias, J., & Marik, P. E. (2021). Review of the Emerging Evidence Demonstrating the Efficacy of Ivermectin in the Prophylaxis and Treatment of COVID-19. American Journal of Therapeutics, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kriebel, D., Tickner, J., Epstein, P., Lemons, J., Levins, R., Loechler, E. L., Quinn, M., Rudel, R., Schettler, T., & Stoto, M. (2001). The precautionary principle in environmental science. Environmental Health Perspectives, 109(9), 871–876. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1240435/.

- Kulldorff, M. , Gupta, S., & Bhattacharya, J. (2020). Great Barrington Declaration and Petition. Great Barrington Declaration.

- Lenton, R. (2020, July 31). Community Update #6—Toronto in Stage 3 – What it means for York. Better Together.

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science: IS, 5, 69. [CrossRef]

- Loh, L. C. (2021, July 1). Re: Vaccination of University of Toronto Students for the 2021-2022 Academic Year. Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210702164639.

- Ludvigsson, J. F., Engerström, L., Nordenhäll, C., & Larsson, E. (2021). Open Schools, Covid-19, and Child and Teacher Morbidity in Sweden. The New England Journal of Medicine, NEJMc2026670. [CrossRef]

- Lupton, A. (2021, September 8). Western-affiliated ethics prof says she faces “imminent dismissal” for refusing COVID-19 vaccine. CBC News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/western-affiliated-ethics-prof-says-she-faces-imminent-dismissal-for-refusing-covid-19-vaccine-1.6168094.

- Macintosh, M. (2021, May 26). May 2021: Steinbach school issues gag order to teachers. Winnipeg Free Press. Available online: https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/breakingnews/2021/05/26/steinbach-school-issues-gag-order-to-teachers.

- Malterud, K. (2001a). Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. The Lancet, 358(9280), 483–488. [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K. (2001b). Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. The Lancet, 358(9280), 483–488. [CrossRef]

- Mandavilli, A. (2020, March 31). Infected but Feeling Fine: The Unwitting Coronavirus Spreaders. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/31/health/coronavirus-asymptomatic-transmission.html.

- Mansanguan, S., Charunwatthana, P., Piyaphanee, W., Dechkhajorn, W., Poolcharoen, A., & Mansanguan, C. (2022). Cardiovascular Manifestation of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine in Adolescents. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 7(8), Article 8. [CrossRef]

- McBride, S. (2021, May 26). Looking Forward to Fall 2021. Resound. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20221130042058/https://www.redeemer.ca/resound/looking-forward-to-fall-2021/.

- McCreary, M. (2020, July 30). Wearing Masks on Our Campuses: What You Need to Know. The Quad. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/the-quad/2020/07/wearing-masks-on-campus-what-you-need-to-know.html.

- McCullough, P. A., Kelly, R. J., Ruocco, G., Lerma, E., Tumlin, J., Wheelan, K. R., Katz, N., Lepor, N. E., Vijay, K., Carter, H., Singh, B., McCullough, S. P., Bhambi, B. K., Palazzuoli, A., De Ferrari, G. M., Milligan, G. P., Safder, T., Tecson, K. M., Wang, D. D., … Risch, H. A. (2021). Pathophysiological Basis and Rationale for Early Outpatient Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Infection. The American Journal of Medicine, 134(1), 16–22. [CrossRef]

- McMaster University. (2020a, March 11). Senate Minutes, Wednesday, March 11, 2020 at 3:30 p.m. McMaster University. Available online: https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/MIN-SENATE-OPEN-2020-March-11.pdf.

- McMaster University. (2020b, March 19). New today: Updates on virtual classrooms, research and campus operations. COVID-19 Back to Mac. Available online: https://covid19.mcmaster.ca/covid-19-update-march-19-2020/.

- McMaster University. (2020c, April 8). Senate Minutes, Wednesday, April 8, 2020 at 3:30 PM. McMaster University; Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20240130155637/https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/PKG-Senate-Open-Session-2019-8-Apr.pdf.

- McMaster University. (2020d, May 1). Face Coverings and Mask Usage – COVID-19. McMaster University. Available online: https://hr.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/2020/05/Face-Coverings-and-Mask-Usage-COVID-19.pdf.

- McMaster University. (2020e, July 10). Masks or face coverings to be required on campus; David Braley Clinic reopening. Daily News COVID-19 (Coronavirus). Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200715235947/https://covid19.mcmaster.ca/masks-or-face-coverings-to-be-required-on-campus-david-braley-clinic-reopening/.

- McMaster University. (2021a). Agenda, Board of Governors, 9:00 AM, Thursday, December 9, 2021. Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231030001018/https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/Board-of-Governors-09-Dec-2021-Open-Agenda-1-Pdf.pdf Reference class.

- McMaster University. (2021b). Agenda, Senate, Wednesday, October 20, 2021 at 3:30 PM (pp. 1–67). McMaster University; Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231029231415/https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/PKG-SENATE-Open-Session-20-Oct-2021.pdf.

- McMaster University. (2021c). Agenda, Undergraduate Council, Tuesday, September 28, 2021 at 2:30 p.m. (pp. 1–55). McMaster University; Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20240130160028/https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/Undergraduate-Council-28-Sep-2021-Agenda-Pdf.pdf/.

- McMaster University. (2021d, April 14). Senate Minutes, Wednesday, April 14, 2021 at 3:30 p.m. McMaster University. Available online: https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/MIN-SENATE-OPEN-2021-April-14.pdf.

- McMaster University. (2021e, June 10). Agenda, Board of Governors, 8:30 AM, Thursday, June 10, 2021. McMaster University.

- McMaster University. (2021f, July 21). McMaster student residences will require COVID vaccinations. COVID-19 BacktoMac. Available online: https://covid19.mcmaster.ca/mcmaster-student-residences-will-require-covid-vaccinations/.

- McMaster University. (2021g, July 31). McMaster Housing: Future Residents Fall 2021. Housing & Conference Services. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210731110456/https://housing.mcmaster.ca/future-residents/fall-2021/.

- McMaster University. (2021h, September 8). Senate Minutes, Wednesday, September 8, 2021 at 3:30 p.m. McMaster University. Available online: https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/MIN-SENATE-OPEN-2021-September-8.pdf.

- McMaster University. (2021i, September 8). Vaccination Policy: COVID-19 Requirements for Employees and Students. McMaster University. Available online: https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/Vaccination-Policy-COVID-19-Requirements-for-Employees-and-Students.pdf.

- McMaster University. (2021j, September 28). Undergraduate Council Minutes, Tuesday, September 28, 2021 at 2:30 p.m. McMaster University. Available online: https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/Minutes-September-28th-2021.pdf.

- McMaster University. (2022a, June 8). Senate Minutes, Wednesday, June 8, 2022 at 3:30 p.m. McMaster University. Available online: https://secretariat.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/MIN-SENATE-OPEN-2022-June-8.pdf.

- McMaster University. (2022b, August 25). Back to Mac: Employee guide to fall 2022. Daily News. Available online: https://dailynews.mcmaster.ca/articles/back-to-mac-employee-guide-to-fall-2022/.

- McMaster University. (2023, March 2). McMaster, University of Ottawa join forces to prepare Canada for future pandemics. Brighter World - McMaster University. Available online: https://brighterworld.mcmaster.ca/articles/mcmaster-university-of-ottawa-join-forces-to-prepare-canada-for-future-pandemics/.

- McMaster University Faculty Association. (2020a, March 13). COVID-19: The fast-moving crisis and response at McMaster. COVID-19: The Fast-Moving Crisis and Response at McMaster. Available online: https://macfaculty.mcmaster.ca/covid-19-the-fast-moving-crisis-and-response-at-mcmaster/.

- McMaster University Faculty Association. (2020b, April 15). COVID-19 Resources for Faculty Members. COVID-19 Resources for Faculty Members. Available online: https://macfaculty.mcmaster.ca/covid-19-resources-for-faculty-members/.

- McMaster University Faculty Association. (2020c, May 1). McMaster University Faculty Association Newlsetter, May 2020. MUFA Newsletter, 1–15. Available online: https://macfaculty.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/2021/01/202005Newsletter.pdf.

- McMaster University Faculty Association. (2021, September 1). McMaster University Faculty Association Newlsetter, September 2021. MUFA Newsletter, 1–13. Available online: https://macfaculty.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/2021/09/202109Newsletter.pdf Reference class.

- McMaster University Faculty Association. (2022, May 1). McMaster University Faculty Association Newlsetter, May 2022. MUFA Newsletter, 1–14. Available online: https://macfaculty.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/2022/05/202205Newsletter.pdf.

- Mema, S. (2021, September 20). Letter from Interior Health Medical Health Officer. Available online: https://bog3.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2021/09/1.8_2021.09_Letter-from-Interior-Health-Medical-Health-Officer.pdf.

- Michalski v. McMaster University, 2022 ONSC 2625 (CanLII) (April 29, 2022). Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onscdc/doc/2022/2022onsc2625/2022onsc2625.pdf.

- Mingers, J. (2000). What is it to be Critical?: Teaching a Critical Approach to Management Undergraduates. Management Learning, 31(2), 219–237. [CrossRef]

- Moore, K. M. (2022, March 1). Re: Revocation of Instructions issued by the Office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health. Office of Chief Medical Officer of Health, Public Health.

- Moore, M. (2022, February 10). Memorial University has 15 staff members on unpaid leave due to vaccination status. CBC News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/mun-faculty-staff-unpaid-leave-covid-vaccine-1.6344733.

- Munn, Z., Stern, C., Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., & Jordan, Z. (2018). What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 5. [CrossRef]

- Naveed, Z., Li, J., Spencer, M., Wilton, J., Naus, M., García, H. A. V., Otterstatter, M., & Janjua, N. Z. (2022). Observed versus expected rates of myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A population-based cohort study. CMAJ, 194(45), E1529–E1536. [CrossRef]

- Non-Academic Staff Association University of Alberta. (2021, August 10). NASA statement on a safe return to campus. NASA (Non-Academic Staff Association of University of Alberta). Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230922150440/https://www.nasa.ualberta.ca/nasa-statement-safe-return-campus.

- Office of the Premier. (2020, March 12). Statement from Premier Ford, Minister Elliott, and Minister Lecce on the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). Ontario Newsroom.

- Ontario Newsroom. (2021, March 22). Ontario Supports Colleges and Universities Impacted by COVID-19. Ontario Newsroom. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/en/backgrounder/60812/ontario-supports-colleges-and-universities-impacted-by-covid-19.

- Oromoni, A. (2022, May 9). McMaster University wins judicial review over removal of students for refusing COVID-19 vaccine. Law Times. Available online: https://www.lawtimesnews.com/practice-areas/litigation/mcmaster-university-wins-judicial-review-over-removal-of-students-for-refusing-covid-19-vaccine/366479.

- Ortiz v. University of Toronto, 2022 HRTO 1288 (CanLII) (October 28, 2022). Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onhrt/doc/2022/2022hrto1288/2022hrto1288.pdf.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, n71. [CrossRef]

- Pezzullo, A. M., Axfors, C., Contopoulos-Ioannidis, D. G., Apostolatos, A., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2023). Age-stratified infection fatality rate of COVID-19 in the non-elderly population. Environmental Research, 216, 114655. [CrossRef]

- Pfizer. (2022). Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 BNT162b2 Vaccine Effectiveness Study—Kaiser Permanente Southern California (Clinical Trial Registration NCT04848584). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04848584.

- Pluye, P., & Hong, Q. N. (2014). Combining the Power of Stories and the Power of Numbers: Mixed Methods Research and Mixed Studies Reviews. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 29–45. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2024, March 20). Updated guidance on the use of protein subunit COVID-19 vaccine (Novavax Nuvaxovid). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/vaccines-immunization/national-advisory-committee-immunization-updated-guidance-use-protein-subunit-covid-19-vaccine-novavax-nuvaxovid.html.

- Redeemer University. (2020a). A Safe Return to Campus. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210610185130/https://www.Redeemer.ca/covid-19/safe-return/.

- Redeemer University. (2020b, July 1). Redeemer Framework for Fall 2020. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210510044644/https://www.Redeemer.ca/covid-19/Redeemer-framework-for-fall-2020/.

- Redeemer University. (2021, May 13). COVID-19: Updates. Redeemer University. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210607183234/https://www.redeemer.ca/covid-19/updates/.

- Redeemer University. (2024, September 27). Response from Redeemer University, September 27, 2024. Redeemer University.

- Regehr, C., & Hannah-Moffat, K. (2022, July 28). Monitoring COVID-19 Conditions. University of Toronto.

- Return to McMaster Oversight Committee. (2021). Return to McMaster Oversight Committee Report (pp. 1–17). McMaster University. Available online: https://covid19.mcmaster.ca/app/uploads/2021/05/Return-to-McMaster-Oversight-Committee-Report-May-2021.pdf.

- Richardson, A. (2021a, April 27). Message from UBCFA President: Merit/Returning to Campus. University of British Columbia Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.facultyassociation.ubc.ca/member_notice/message-president-returning/.

- Richardson, A. (2021b, July 26). Message from the President – Return to Campus. University of British Columbia Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.facultyassociation.ubc.ca/member_notice/message-president-return/.

- Richardson, A. (2021c, August 9). Message from the President – Update on Return to Campus. University of British Columbia Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.facultyassociation.ubc.ca/member_notice/message-president-update/.

- Richardson, A. (2021d, August 9). Re: Return to campus, August 9, 2021. Available online: https://ubcfa.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/LT-Ono-McKenzie-9-Aug21-re-Return-to-Campus.pdf.

- Richardson, A. (2021e, August 24). Re: Return to campus, response letter, August 24, 2021. Available online: https://ubcfa.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/LT-Ono-McKenzie-24-Aug21-re-Return-to-Campus.pdf.

- Richardson, A. (2021f, December 16). Message from the President: Omicron and Safety Concerns. University of British Columbia Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.facultyassociation.ubc.ca/member_notice/message-president-concerns/.

- Risch, H. A. (2020). Early Outpatient Treatment of Symptomatic, High-Risk COVID-19 Patients That Should Be Ramped Up Immediately as Key to the Pandemic Crisis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 189(11), 1218–1226. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Quejada, L., Toro Wills, M. F., Martínez-Ávila, M. C., & Patiño-Aldana, A. F. (2022). Menstrual cycle disturbances after COVID-19 vaccination. Women’s Health, 18, 17455057221109375. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M. N. K., & Rojon, C. (2011). On the attributes of a critical literature review. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 4(2), 156–162. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, M. (2022, March 24). CDC coding error led to overcount of 72,000 Covid deaths. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/24/cdc-coding-error-overcount-covid-deaths Reference class.

- S.C.S. v. The University of Winnipeg Faculty Association, Collegiate Division, 2022 CanLII 131218 (MB LB) (July 27, 2022). Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/mb/mblb/doc/2022/2022canlii131218/2022canlii131218.pdf.

- Sharman, A. (2020, June 11). COVID-19 Response Update: U of A Phase 2 Starting in July. The Quad. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/the-quad/2020/06/covid-19-response-update-u-of-a-phase-2-starting-in-july.html Reference class.

- Shrestha, N. K., Burke, P. C., Nowacki, A. S., Simon, J. F., Hagen, A., & Gordon, S. M. (2023). Effectiveness of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Bivalent Vaccine. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 10(6), ofad209. [CrossRef]

- Shuster, E. (1997). Fifty Years Later: The Significance of the Nuremberg Code. New England Journal of Medicine, 337(20), 1436–1440. [CrossRef]

- Sprout, B. (2020, March 16). Notice from the President re: Coronavirus. University of British Columbia Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.facultyassociation.ubc.ca/member_notice/notice-president-coronavirus/.

- Stobbe, M. (2020, April 2). More evidence emerges that coronavirus infections can spread by people with no clear symptoms. CBC News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/covid-19-singapore-symptoms-1.5518772.

- Subramanian, S. V., & Kumar, A. (2021). Increases in COVID-19 are unrelated to levels of vaccination across 68 countries and 2947 counties in the United States. European Journal of Epidemiology, 36(12), 1237–1240. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Z. W., & Charran, C. (2023). Measuring College Students’ with Disabilities Attitudes Toward Taking COVID-19 Vaccines. Interchange (Toronto, Ont. : 1984), 54(1), 39–47. [CrossRef]

- Teotonio, I. (2022, March 25). One professor fired, others face discipline as universities enforce soon-to-expire vaccine mandates. The Toronto Star.

- The University of British Columbia. (2021, May 25). UBC experts on COVID-19. UBC News. Available online: https://news.ubc.ca/advisory/ubc-experts-on-covid-19-2/.

- The University of Toronto Students’ Union Executive Committee. (2021, August 14). Open Letter RE: University of Toronto’s Return to Campus Plan for Fall 2021. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1OfNvyRtskiftNp-GWEBdTK_TvigzFHJX/view.

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. [CrossRef]

- @TO Public Health. (2020, June 24). @peteevans66 Individuals who have died with COVID-19, but not as a result of COVID-19 are included in the case counts for COVID-19 deaths in Toronto. Available online: https://twitter.com/TOPublicHealth/status/1275888390060285967.

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Trosow, S. E., & Lowe, J. (2021, September 10). Canadian colleges and universities can mandate COVID-19 vaccination without violating Charter rights. University Affairs. Available online: https://www.universityaffairs.ca/opinion/in-my-opinion/canadian-colleges-and-universities-can-mandate-covid-19-vaccination-without-violating-charter-rights/.

- U of T News Team. (2021, August 11). ‘The public health evidence is clear’: Salvatore Spadafora on U of T’s vaccine requirement. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/public-health-evidence-clear-salvatore-spadafora-u-t-s-vaccine-requirement.

- UNESCO. (2005). Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/ethics-science-technology/bioethics-and-human-rights.

- University of Alberta. (2020a). Campus 2020-2021: A Framework for the University of Alberta. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200719054211/https://www.ualberta.ca/covid-19/about/campus-2020-21.html.

- University of Alberta. (2020b, June 12). Draft Open Session Minutes, General Faculties Council, Council on Student Affairs, Friday, June 12, 2020. University of Alberta. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/governance/media-library/documents/member-zone/gfc-standing-committees/cosa-minutes/2020-06-12-cosa-minutes.pdf.

- University of Alberta. (2020c, June 22). Open Session Agenda, General Faculties Council, Monday, June 22, 2020. University of Alberta. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/governance/media-library/documents/member-zone/gfc/agenda-and-docs/2020-06-22-gfc-agenda-documents.pdf.

- University of Alberta. (2020d, October 26). Non-Medical Masks on Campus. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20201025092644/https://www.ualberta.ca/covid-19/campus-safety/safety-measures-general-directives/masks.html.

- University of Alberta. (2021a). Public Health Response Team (PHRT). Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210427233703/https://www.ualberta.ca/facilities-operations/portfolio/emergency-management-office/what-does-the-university-do/respond-university/crisis-management-team/phrt.html.

- University of Alberta. (2021b, February 22). Open Session Agenda, General Faculties Council, Monday, February 22, 2021. University of Alberta. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/governance/media-library/documents/member-zone/gfc/agenda-and-docs/2021-02-22-gfc-agenda-documents.pdf.

- University of Alberta. (2021c, August 17). New Measures for Fall Return to Campus. University of Alberta News. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/news/2021/08/new-measures-for-fall-return-to-campus.html.

- University of Alberta. (2021d, September 13). Enhancing vaccination protocols for campus safety. University of Alberta News. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/news/2021/09/enhancing-vaccination-protocols-for-campus-safety.html.

- University of Alberta. (2021e, September 26). Safety Directives Exemption – University of Alberta. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210926120642/https://www.ualberta.ca/current-students/academic-success-centre/accessibility-resources/arrange/safety-directives-exemption.html.

- University of Alberta. (2021f, October 6). Vaccination Directive – University of Alberta. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20211006095449/https://www.ualberta.ca/covid-19/vaccinations-testing/vaccination-directive.html.

- University of Alberta. (2022a, January 31). Open Session Agenda, General Faculties Council, Monday, January 31, 2022. University of Alberta. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/governance/media-library/documents/member-zone/gfc/agenda-and-docs/2022-01-31-gfc-agenda-documents.pdf.

- University of Alberta. (2022b, March 11). Updates for the U of A community, week ending March 11. University of Alberta. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/covid-19/updates/2022/03/2022-03-11-updates-for-week-ending-march-11.html.

- University of Alberta COVID-19 Vaccination Working Group. (2021). Vaccination Working Group Report 2021 – University of Alberta. University of Alberta. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/en/campus-operations-services/media-library/documents/vaccination-working-group-report-2021.pdf.

- University of Alberta Students Union. (2021, December 22). UASU responds to Omicron wave and temporary remote learning. University of Alberta Students Union. Available online: https://www2.su.ualberta.ca/about/news/entry/373/uasu-responds-to-omicron-wave-and-temporary-remote-learning/.

- University of Alberta Students Union. (2022, January 14). Students brace for delayed return to campus. University of Alberta Students Union. Available online: https://www2.su.ualberta.ca/about/news/entry/374/students-brace-for-delayed-return-to-campus/.

- University of British Columbia. (2020a, July 15). UBC COVID-19 Safety Planning Framework. University of British Columbia. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200715183708/https://srs.ubc.ca/files/2020/07/UBC-COVID-19-Safety-Planning-Framework.pdf.

- University of British Columbia. (2020b, September 11). COVID-19—Required use of non-medical masks at UBC, effective Sep 16. UBC Broadcast. Available online: https://broadcastemail.ubc.ca/2020/09/11/covid-19-required-use-of-non-medical-masks-at-ubc-effective-sep-16/.

- University of British Columbia. (2020c, September 16). UBC COVID-19 Safety Rules—September 16, 2020—Version 2. University of British Columbia; Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20201122190205/https://srs.ubc.ca/files/2020/06/4.-COVID-19-Campus-Rules.pdf.

- University of British Columbia. (2021, December 15). Vancouver Senate Materials – December 15, 2021. University of British Columbia. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20211214182724/https://senate.ubc.ca/sites/senate.ubc.ca/files/downloads/20211215%20Vancouver%20Senate%20Materials.pdf.

- University of British Columbia. (2022a). UBC 2021/22 Institutional Accountability Plan and Report (pp. 1–135). University of British Columbia. Available online: https://bog3.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2022/06/4_2022.06_UBC-Annual-Report-2021-2022-and-Institutional-Accountability-Plan-Report.pdf.

- University of British Columbia. (2022b, January 25). UBC COVID-19 Campus Rules—January 25, 2022—Version 14. University of British Columbia. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20220201211241/https://riskmanagement.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2021/09/COVID19-Campus-Rules.pdf.

- University of British Columbia Board of Governors. (2022, January 25). Minutes, Board of Governors, Tuesday, January 25, 2022. University of British Columbia. Available online: https://bog3.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2022/09/MIN-BG-2022.01.pdf.

- Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onipc/doc/2022/2022canlii25559/2022canlii25559.pdf.

- University of Toronto. (2020a). COVID-19 Response and Adaptation Committee. Division of the Vice-President & Provost - University of Toronto. Available online: https://www.provost.utoronto.ca/committees/covid-19-response-and-adaptation-committee/.

- University of Toronto. (2020b). UTogether2020: A Roadmap for the University of Toronto. University of Toronto; Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200521211047/https://www.provost.utoronto.ca/planning-policy/utogether2020-a-roadmap-for-the-university-of-toronto/.

- University of Toronto. (2020c, April 2). Report: Governing Council - April 2, 2020. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/governing-council/reports/apr-02-2020.

- University of Toronto. (2020d, August 10). Report of the COVID-19 Special Committee. University of Toronto. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/sites/default/files/agenda-items/20200909_GC_4b.pdf.

- University of Toronto. (2020e, October 6). Policy on Non-Medical Masks or Face Coverings—Business Board, September 2, 2020 for October 6, 2020. University of Toronto. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/sites/default/files/agenda-items/20201006_BB_02bii.pdf.

- University of Toronto. (2020f, October 8). Report: Academic Board - October 08, 2020. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/academic-board/reports/oct-08-2020.

- University of Toronto. (2020g, November 18). Report: Academic Board - November 18, 2020. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/academic-board/reports/nov-18-2020.

- University of Toronto. (2021a). Council of Ontario Universities – Academic Colleague Report, May 2020 – April 2021 (pp. 1–3). Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/system/files/agenda-items/20210527_AB_11a.pdf.

- University of Toronto. (2021b). Joint Provostial and Human Resources Guideline on Vaccination (pp. 1–3). University of Toronto. Available online: https://www.provost.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/U-of-T-Vaccine-Guideline-Sep.3.2021.pdf.

- University of Toronto. (2021c, February 25). Report: Governing Council - February 25, 2021. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/governing-council/reports/feb-25-2021.

- University of Toronto. (2021d, May 4). Report: Executive Committee - May 04, 2021. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/executive-committee/reports/may-04-2021.

- University of Toronto. (2021e, September 9). Report: Governing Council - September 09, 2021. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/governing-council/reports/sep-09-2021.

- University of Toronto. (2021f, October 28). Report: Governing Council - October 28, 2021. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/governing-council/reports/oct-28-2021.

- University of Toronto. (2021g, December 7). Report: Executive Committee - December 07, 2021. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/executive-committee/reports/dec-07-2021.

- University of Toronto. (2021h, December 16). Report: Governing Council - December 16, 2021. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/governing-council/reports/dec-16-2021.

- University of Toronto. (2022a, January 25). Report: UTM Campus Council - January 25, 2022. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/utm-campus-council/reports/jan-25-2022.

- University of Toronto. (2022b, March 31). Report: Governing Council - March 31, 2022. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/governing-council/reports/mar-31-2022.

- University of Toronto. (2022c, April 3). UTogether FAQs – University of Toronto. University of Toronto; Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20220403083741/http://www.utoronto.ca/utogether/faqs.

- University of Toronto. (2022d, April 26). Report: Business Board - April 26, 2022. University of Toronto | Secretariat. Available online: https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/page/governance-bodies/business-board/reports/apr-26-2022.

- University of Toronto. (2023, July 14). COVID-19 General Workplace Guideline (GWG). University of Toronto. Available online: https://ehs.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/MERGED-COVID-19-20220923.pdf.

- University of Toronto Faculty Association. (2020a, March 17). Update: COVID-19 crisis at U of T. University of Toronto Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.utfa.org/content/update-covid-19-crisis-u-t.

- University of Toronto Faculty Association. (2020b, May 15). Fall Teaching: Faculty Need Choice and Support. University of Toronto Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.utfa.org/content/fall-teaching-faculty-need-choice-and-support.

- University of Toronto Faculty Association. (2020c, July 28). U of T’s Reopening Plan is NOT Safe Enough. We Need to Take Fall 2020 Online. University of Toronto Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.utfa.org/content/u-t-s-reopening-plan-not-safe-enough-we-need-take-fall-2020-online.

- University of Toronto Faculty Association. (2021a, July 21). Coalition of Toronto-area university staff call on Administrations to commit to transparency to accelerate a safe return to in-person learning. University of Toronto Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.utfa.org/content/coalition-toronto-area-university-staff-call-administrations-commit-transparency-accelerate.

- University of Toronto Faculty Association. (2021b, August 31). Open Letter to President Gertler on COU Lobbying on Occupancy Limits. University of Toronto Faculty Association. Available online: https://www.utfa.org/content/open-letter-president-gertler-cou-lobbying-occupancy-limits.

- University of Toronto, Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Office. (2023). Access decision re: COVID-19 vaccination mandate exemptions (Request #23-0036). University of Toronto.

- University of Toronto Graduate Students Union. (2020, March 27). COVID-19 Convocation Cancelation Statement. University of Toronto Graduate Students Union. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1aJSBHw_BbGfpdpUPsrdAKbFCPlliduMw/view?usp=drive_open&usp=embed_facebook.

- University of Toronto Students Union. (2020, September 12). UTSU CityNews Interview Regarding Campus Closures and COVID-19. University of Toronto Students Union. Available online: https://www.utsu.ca/utsu-president-on-citynews-speaking-out-about-the-u-of-t-reopening-plans-and-lack-of-student-consultation/.

- University of Toronto Students Union. (2021, August 21). University of Toronto’s Return to Campus Plan for Fall 2021. Google Doc. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1OfNvyRtskiftNp-GWEBdTK_TvigzFHJX/view?usp=drive_link&usp=embed_facebook.

- University of Toronto Students’ Union. (2021, September 1). We still need your support to create a safer campus! University of Toronto Students’ Union. Available online: https://www.utsu.ca/we-still-need-your-support-to-create-a-safer-campus/.

- University of Waterloo. (2021, October 18). University of Waterloo Senate, Minutes of the Monday 18 October 2021 Meeting. University of Waterloo. Available online: https://uwaterloo.ca/secretariat/sites/default/files/uploads/files/20211115oagsen_package_2_0.pdf.

- Vendeville, G. (2020, January 31). U of T takes steps to protect and inform community members during coronavirus outbreak. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-takes-steps-protect-and-inform-community-members-during-coronavirus-outbreak.

- Vendeville, G. (2021a, August 26). U of T to require proof of vaccination for all community members coming to campus. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-require-proof-vaccination-all-community-members-coming-campus.

- Vendeville, G. (2021b, October 1). U of T community members upload proof of vaccination status. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-community-members-upload-proof-vaccination-status.

- Vinita Dubey. (2021, July 1). Re: Optimizing COVID-19 vaccination rates in Post-Secondary Institutions. Wayback Machine. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210702164656/https://www.viceprovoststudents.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/Toronto-Public-Health-Letter.pdf.

- Walt, G. (1994). Health Policy: An Introduction to Process and Power. Zed Books.

- WHO. (2019). Non-pharmaceutical public health measures for mitigating the risk and impact of epidemic and pandemic influenza. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/non-pharmaceutical-public-health-measuresfor-mitigating-the-risk-and-impact-of-epidemic-and-pandemic-influenza.

- Wilfred Laurier University v. United Food and Commercial Workers Union, 2022 CanLII 69168 (ON LA) (July 22, 2022). Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onla/doc/2022/2022canlii69168/2022canlii69168.pdf.

- Wilfrid Laurier University v. United Food and Commercial Workers Union, 2022 CanLII 120371 (ON LA) (December 16, 2022). Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onla/doc/2022/2022canlii120371/2022canlii120371.pdf.

- York University. (2023). Working in Partnership—York University Office of the President. 2023 President’s Annual Report. Available online: https://presidentsreport2023.yorku.ca/our-priorities/working-in-partnership/.

- Yousefi, N. S., Dara R, Mubareka S, Papadopoulos A, & Sharif S. (2021). An Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccine Sentiments and Opinions on Twitter. International Journal of Infectious Diseases : IJID : Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, 108, 256–262. O. [CrossRef]

- Zou, B. (2023, March 2). U of T home to new hub that will strengthen Canada’s pandemic preparedness and increase biomanufacturing capacity. U of T News. Available online: https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-home-new-hub-will-strengthen-canada-s-pandemic-preparedness-and-increase-biomanufacturing.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).