Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Patients

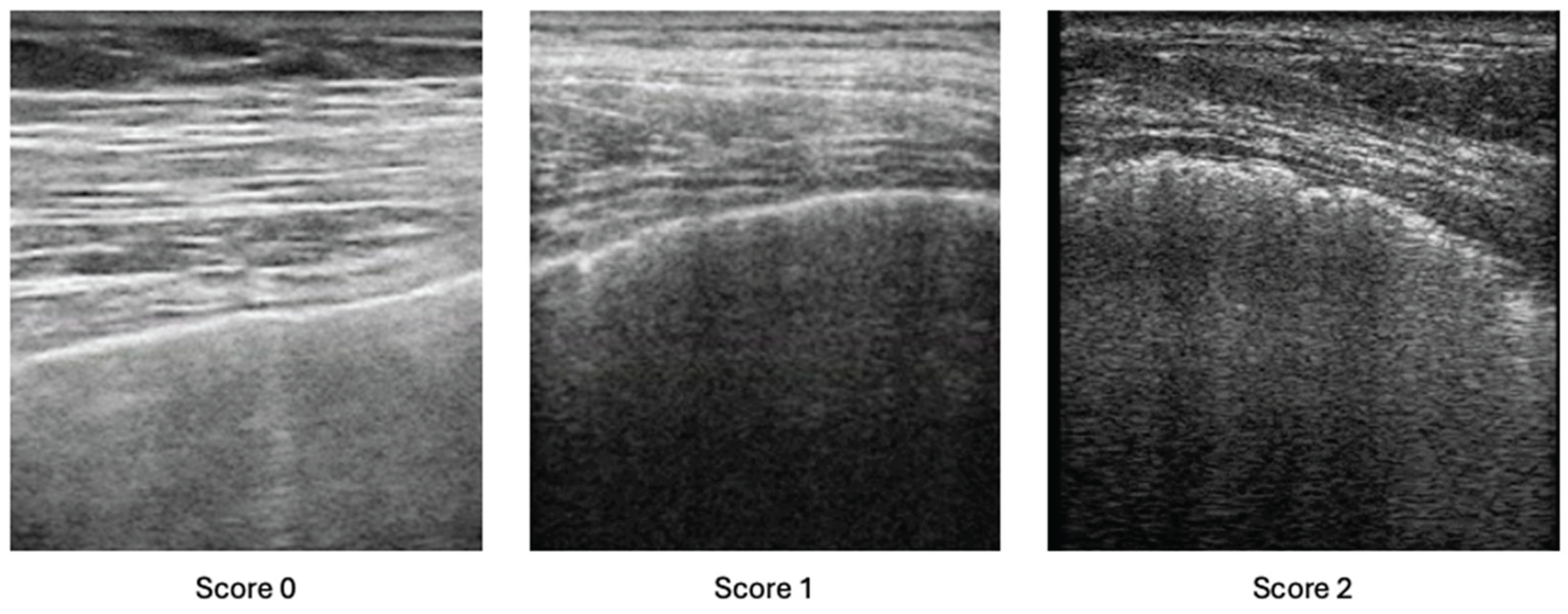

Lung Ultrasound Assessment

Statistical Analysis

Results

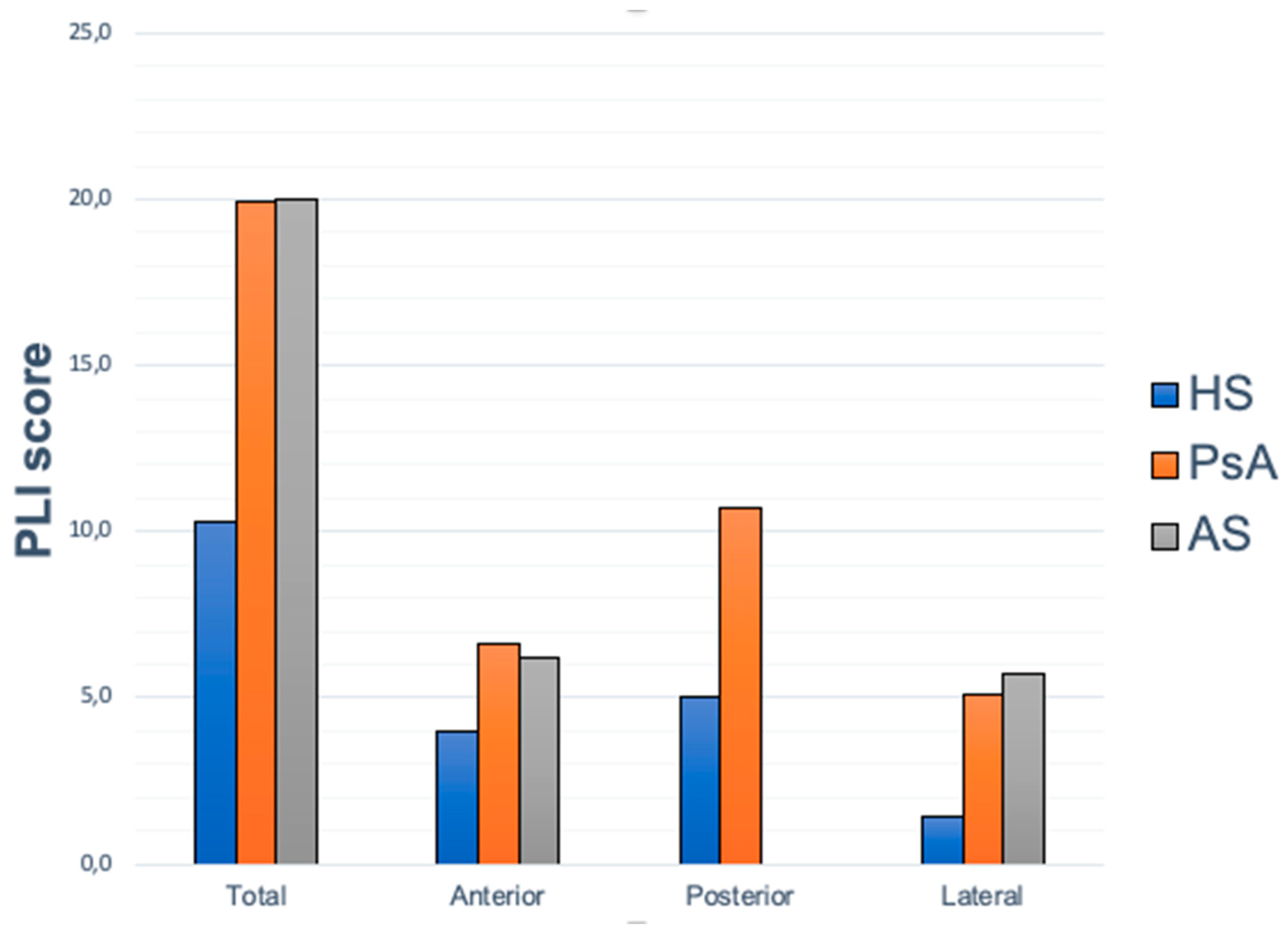

Ultrasound Results

PLI Score Correlation with Demographic Data and PROs

PLI Score Correlation with Clinical Data

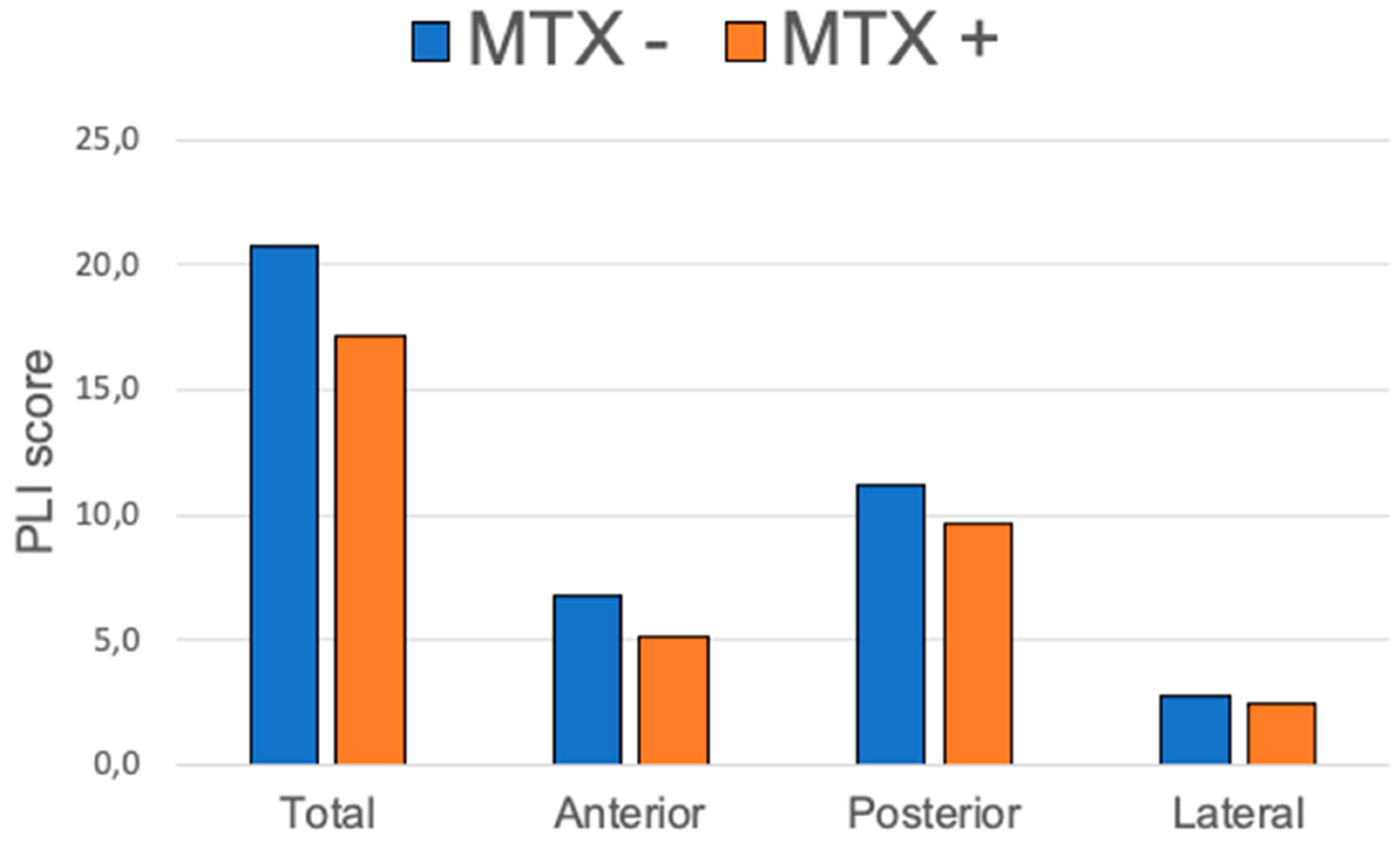

PLI Score Correlation with Treatments

4. Discussion

Future Research Directions

Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

References

- Joy GM, Arbiv OA, Wong CK, et al. Prevalence, imaging patterns and risk factors of interstitial lung disease in connective tissue disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32:220210. [CrossRef]

- Manfredi A, Sambataro G, Rai A, et al. Prevalence of Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Disease in Patients with Primary Sjogren Syndrome. J Pers Med. 2024;14(7):708. [CrossRef]

- Wittram C, Mark EJ, McLoud TC. CT-histologic correlation of the ATS/ERS 2002 classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Radiographics. 2003;23:1057-71. [CrossRef]

- Dai Y, Wang W, Yu Y, Hu S. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: an overview of epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(4):1211-1220.

- Sampaio-Barros PD, Cerqueira EM, Rezende SM, et al. Pulmonary involvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:225-30. [CrossRef]

- El Maghraoui A, Dehhaoui M. Prevalence and Characteristics of Lung Involvement on High Resolution Computed Tomography in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Systematic Review. Pulm Med 2012; 2012: 965956. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Kong L, Li F, et al. Association between Psoriasis and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PloS One 2015;10:e0145221. [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto H, Hara H, Minagawa S, et al. Interstitial Pneumonia in Psoriasis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2018;2:370-377.

- Ishikawa G, Dua S, Mathur A, et al. Concomitant Interstitial Lung Disease with Psoriasis. Can Respir J 2019;Aug 25;2019:5919304. [CrossRef]

- Peluso R, Iervolino S, Vitiello M, Bruner V, Lupoli G, Di Minno MND. Extra-articular manifestations in psoriatic arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol 2015;34:745–53. [CrossRef]

- Yue L, Yan Y, Zhao S. A bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study to evaluate the relationship between psoriasis and interstitial lung diseases. BMC Pulm Med 2024;24:330. [CrossRef]

- Bargagli E, Bellisai F, Mazzei MA, et al. Interstitial lung disease associated with psoriatic arthritis: a new disease entity? Intern Emerg Med 2021;16:229–31.

- Schäfer VS, Winter L, Skowasch D, et al. Exploring pulmonary involvement in newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriatic arthritis: a single center study. Rheumatol Int 2024;44:1975-1986. [CrossRef]

- Provan SA, Ljung L, Kristianslund EK, et al. Interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis patients initiating biologics, and controls - data from five Nordic registries. J Rheumatol 2024 Sep 1:jrheum.2024-0252.

- Moazedi-Fuerst FC, Kielhauser S, Brickmann K, et al. Sonographic assessment of interstitial lung disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33:S87-91.

- Gargani L, Romei C, Bruni C, et al. Lung ultrasound B-lines in systemic sclerosis: cut-off values and methodological indications for interstitial lung disease screening. Rheumatol Oxf Engl 2022;61:SI56–64. [CrossRef]

- Foeldvari I, Klotsche J, Hinrichs B, et al. Underdetection of Interstitial Lung Disease in Juvenile Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res 2022;74:364–70. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi A, Oshnoei S, Ghasemi-rad M. Comparison of a new, modified lung ultrasonography technique with high-resolution CT in the diagnosis of the alveolo-interstitial syndrome of systemic scleroderma. Med Ultrason 2014;16:27–31.

- Barskova T, Gargani L, Guiducci S, et al. Lung ultrasound for the screening of interstitial lung disease in very early systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:390–5. [CrossRef]

- Gargani L, Doveri M, D’Errico L, et al. Ultrasound lung comets in systemic sclerosis: a chest sonography hallmark of pulmonary interstitial fibrosis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl 2009;48:1382–7. [CrossRef]

- Moazedi-Fuerst FC, Kielhauser SM, Scheidl S, et al. Ultrasound screening for interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32:199–203.

- Moazedi-Fuerst FC, Zechner PM, Tripolt NJ, et al. Pulmonary echography in systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol 2012; 31:1621–5. [CrossRef]

- Sperandeo M, De Cata A, Molinaro F, et al. Ultrasound signs of pulmonary fibrosis in systemic sclerosis as timely indicators for chest computed tomography. Scand J Rheumatol 2015;44:389–98. [CrossRef]

- Pinal-Fernandez I, Pallisa-Nuñez E, Selva-O’Callaghan A, et al. Pleural irregularity, a new ultrasound sign for the study of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis and antisynthetase syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33:S136-141.

- Sferrazza Papa GF, Pellegrino GM, Volpicelli G, et al. Lung Ultrasound B Lines: Etiologies and Evolution with Age. Respir Int Rev Thorac Dis 2017;94:313–4. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez M, Soto-Fajardo C, Pineda C, et al. Ultrasound in the Assessment of Interstitial Lung Disease in Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Literature Review by the OMERACT Ultrasound Group. J Rheumatol 2020;47:991–1000. [CrossRef]

- Delle Sedie A, Terslev L, Bruyn G.A.W., Cazenave T, Chrysidis S, Diaz M et al. Standardization of Interstitial Lung Disease Assessment by Ultrasound: Results from a Delphi Process and Web-reliability exercise by the OMERACT Ultrasound Working Group. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2024;65:152406.

- Tardella M, Gutierrez M, Salaffi F, Carotti M, Ariani A, Bertolazzi C, et al. Ultrasound in the assessment of pulmonary fibrosis in connective tissue disorders: correlation with high-resolution computed tomography. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1641-7. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez M, Salaffi F, Carotti M, Tardella M, Pineda C, Bertolazzi C, et al. Utility of a simplified ultrasound assessment to assess interstitial pulmonary fibrosis in connective tissue disorders--preliminary results. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R134. [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo M, Tardella M, Filippucci E, Carotti M, Salaffi F. Lung ultrasound in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: definition of significant interstitial lung disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;40:495-500. [CrossRef]

- Buda N, Piskunowicz M, Porzezińska M, Kosiak W, Zdrojewski Z. Lung ultrasonography in the evaluation of interstitial lung disease in systemic connective tissue diseases: criteria and severity of pulmonary fibrosis – analysis of 52 patients. Ultraschall Med. 2016;37:379–85. [CrossRef]

- Gigante A, Rossi Fanelli F, Lucci S, Barilaro G, Quarta S, Barbano B, et al. Lung ultrasound in systemic sclerosis: correlation with high-resolution computed tomography, pulmonary function tests and clinical variables of disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11:213–17. [CrossRef]

- Delle Sedie A, Doveri M, Frassi F, Gargani L, D’Errico G, Pepe P, et al. Ultrasound lung comets in systemic sclerosis: a useful tool to detect lung interstitial fibrosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:S54.

- Gutierrez J, Gutierrez M, Almaguer K, Gonzalez F, Camargo K, Soto C, et al. Ultrasound diagnostic and predictive value of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Diagnostic and predictive value of ultrasound in the assessment of interstitial lung disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:121. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Rabaneda EF, Bong DA, Busquets-Pérez N, Möller I. Ultrasound evaluation of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune diseases. Eur J Rheumatol. 2022 Aug 9. [CrossRef]

- Pinal Fernández I, Pallisa Núñez E, Selva-O'Callaghan A, Castella-Fierro E, Martínez-Gómez X, Vilardell-Tarrés M. Correlation of ultrasound B-lines with high-resolution computed tomography in antisynthetase syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:404-7.

- Buda N, Masiak A, Zdrojewski Z. Utility of lung ultrasound in ANCA-associated vasculitis with lung involvement. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0222189. [CrossRef]

- Buda N, Wojteczek A, Masiak A, Piskunowicz M, Batko W, Zdrojewski Z. Lung Ultrasound in the Screening of Pulmonary Interstitial Involvement Secondary to Systemic Connective Tissue Disease: A Prospective Pilot Study Involving 180 Patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4114. [CrossRef]

- Gasperini ML, Gigante A, Iacolare A, Pellicano C, Lucci S, Rosato E. The predictive role of lung ultrasound in progression of scleroderma interstitial lung disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:119-123. [CrossRef]

- Gargani L, Bruni C, Romei C, Frumento P, Moreo A, Agoston G, et al. Prognostic Value of Lung Ultrasound B-Lines in Systemic Sclerosis. Chest. 2020;158:1515-1525. [CrossRef]

- Tardella M, Di Carlo M, Carotti M, Filippucci E, Grassi W, Salaffi F. Ultrasound B-lines in the evaluation of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: Cut-off point definition for the presence of significant pulmonary fibrosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0566. [CrossRef]

- Hassan RI, Lubertino LI, Barth MA, Quaglia MF, Montoya SF, Kerzberg E, et al. Lung Ultrasound as a Screening Method for Interstitial Lung Disease in Patients With Systemic Sclerosis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:304-307. [CrossRef]

- Bruni C, Mattolini L, Tofani L, Gargani L, Landini N, Roma N, et al. Lung Ultrasound B-Lines in the Evaluation of the Extent of Interstitial Lung Disease in Systemic Sclerosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:1696. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Liu T, Huang S, Qiu L, Luo F, Yin G, et al. Screening value of lung ultrasound in connective tissue disease related interstitial lung disease. Heart Lung. 2023;57:110-116. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Long S, Gutierrez M, Clavijo-Cornejo D, Alfaro-Rodríguez A, González-Sámano K, Cortes-Altamirano JL, et al. Subclinical Interstitial Lung Disease in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. A Pilot Study on the Role of Ultrasound. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2021;17:144-149. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Chen S, Lin J, Xie X, Hu S, Lin Q, et al. Lung ultrasound B-lines and serum KL-6 correlate with the severity of idiopathic inflammatory myositis-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:2024-2029. [CrossRef]

- Buda N, Piskunowicz M, Porzezińska M, Kosiak W, Zdrojewski Z. Lung Ultrasonography in the Evaluation of Interstitial Lung Disease in Systemic Connective Tissue Diseases: Criteria and Severity of Pulmonary Fibrosis – Analysis of 52 Patients Lungensonografie zur Bewertung von interstitiellen Lungenerkrankungenbei. Ultraschall der Medizin. 2016;37:379–85.

- Reissig A, Kroegel C. Transthoracic sonography of diffuse parenchymal lung disease: the role of comet tail artifacts. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:173–80.

- Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–83. [CrossRef]

- Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54: 2665–73. [CrossRef]

- Ward N. The Leicester Cough Questionnaire. J Physiother. 2016;62:53. [CrossRef]

- Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85 Suppl B:25–31; discussion 33-37.

- Mahler DA, Wells CK. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest. 1988;93: 580–6. [CrossRef]

- Shrout P.E., Fleiss J.L. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86: 420-8.

- Fragoulis GE, Nikiphorou E, Larsen J, Korsten P, Conway R. Methotrexate-Associated Pneumonitis and Rheumatoid Arthritis-Interstitial Lung Disease: Current Concepts for the Diagnosis and Treatment. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6:238. [CrossRef]

- Feng Y, Dai L, Zhang Y, et al. Buyang Huanwu Decoction alleviates blood stasis, platelet activation, and inflammation and regulates the HMGB1/NF-κB pathway in rats with pulmonary fibrosis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;319:117088.

- Amira G, Akram D, Fadoua M, et al. Imbalance of TH17/TREG cells in Tunisian patients with systemic sclerosis. Presse Med. 2024;53:104221.

- Park SJ, Hahn HJ, Oh SR, Lee HJ. Theophylline Attenuates BLM-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis by Inhibiting Th17 Differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:1019. [CrossRef]

- Kim JW, Chung SW, Pyo JY, et al. Methotrexate, leflunomide and tacrolimus use and the progression of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62:2377-2385. [CrossRef]

- Kim K, Woo A, Park Y, et al. Protective effect of methotrexate on lung function and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis-related interstitial lung disease: a retrospective cohort study. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2022;16:17534666221135314. [CrossRef]

- Dawson JK, Quah E, Earnshaw B, Amoasii C, Mudawi T, Spencer LG. Does methotrexate cause progressive fibrotic interstitial lung disease? A systematic review. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:1055-1064. [CrossRef]

- Kelly CA, Nisar M, Arthanari S, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis related interstitial lung disease - improving outcomes over 25 years: a large multicentre UK study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:1882-1890. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco Cubero C, Chamizo Carmona E, Vela Casasempere P. Systematic review of the impact of drugs on diffuse interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2021;17:504-513.

- Margaritopoulos GA, Vasarmidi E, Jacob J, Wells AU, Antoniou KM. Smoking and interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24:428–35.

| PsA+AS (n=73) | HS (n=56) | PsA (n=46) | AS (n=27) | |

| M | 38 (52.1%) | 30 | 25 (54.4%) | 14 (51.9%) |

| F | 35 (47.9%) | 26 | 21 (45.6%) | 13 (48.1%) |

| Age (±SD) | 57.8 (11.9) | 56 (15.6) | 58.8 (12.3) | 56.1 (11.4) |

| BMI (±SD) | 26.2 (4) | 24.4 (2.8) | 26.8 (4.1) | 24.7 (3.5) |

| Smoke habits (%) | 26 (35.6%) | 20 (35.7%) | 15 (32.6%) | 11 (40.7%) |

| Disease duration, yrs (±SD) | 15.5 (11.5) | ------- | 14.9 (10.6) | 16.4 (13.5) |

| ASDAS (±SD) | ------- | ------- | ------- | 2.2 (1.4) |

| DAPSA (±SD) | ------- | ------- | 14.1 (10.5) | ------- |

| Psoriasis | 42 | ------- | 42 | 0 |

| TNFa inhibitors, N (%) | 10 (13.7) | ------- | 23 (50) | 22 (81.5) |

| Other bDMARDs, N (%) | 10 (13.7) | ------- | 9 (19.6) | 1 (3.7%) |

| csDMARDs (all), N (%) | 30 (41.1) | ------- | 23 (50) | 7 (25.9) |

| csDMARDs (MTX), N (% csDMARDs) | 18 (60) | ------- | 14 (60.1) | 4 (57.1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).