Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Population

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

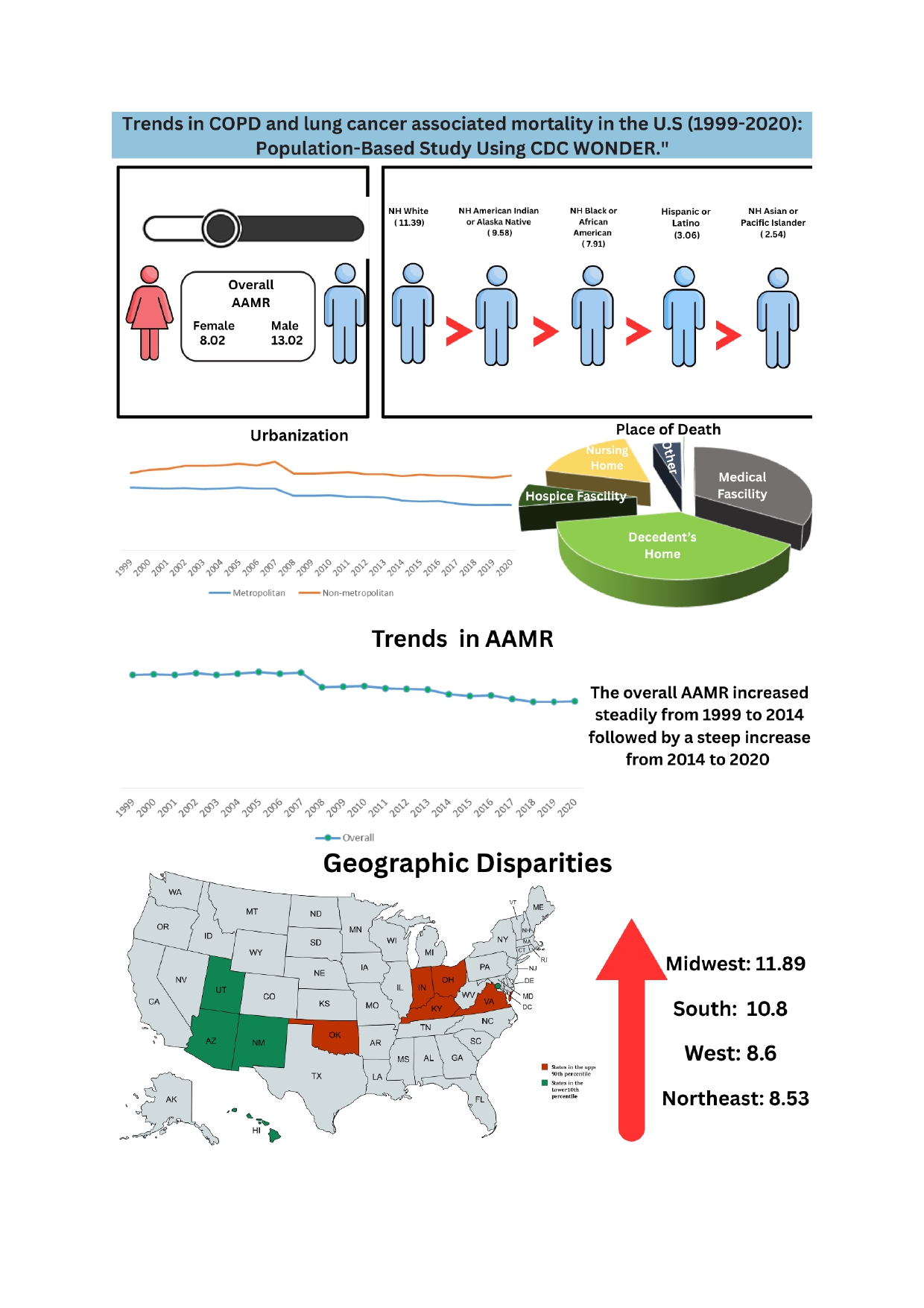

3.1. Annual Trends in COPD and Lung Cancer Related AAMR

3.2. COPD and Lung Cancer Related AAMR Stratified by Gender

3.3. COPD and Lung Cancer Related AAMRs Stratified by Race

3.4. COPD and Lung Cancer Related AAMRs Stratified by Urbanization

3.5. COPD and Lung Cancer Related AAMRs Stratified by Census Region

3.6. COPD and Lung Cancer Related AAMRs Stratified by Place of Death

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agustí, A. , Celli, B. R., Criner, G. J., Halpin, D., Anzueto, A., Barnes, P., Bourbeau, J., Han, M. K., Martinez, F. J., Montes de Oca, M., Mortimer, K., Papi, A., Pavord, I., Roche, N., Salvi, S., Sin, D. D., Singh, D., Stockley, R., López Varela, M. V., Wedzicha, J. A., … Vogelmeier, C. F. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. The European respiratory journal 2023, 61, 2300239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R. L. , Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S., & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst, R. S. , Heymach, J. V., & Lippman, S. M. Lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2008, 359, 1367–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin S, Tejada-Vera B, Bastian B. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2022.; 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr73/NVSR73-10.

- State of Lung Cancer | American Lung Association. www.lung.org. https://www.lung.

- Barnes P., J. Mechanisms of development of multimorbidity in the elderly. The European respiratory journal 2015, 45, 790–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, A. L. , & Adcock, I. M. The relationship between COPD and lung cancer. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2015, 90, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple Cause of Death Data on WONDER Online Database [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics; [cited 2025 ]. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10. 04 May.

- Equator Network. *STROBE Statement—Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology* [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 18]. Available from: [https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/](https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple Cause of Death Data on WONDER: Help Page [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics; [cited 2025 Mar 18]. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/mcd.html#HHS%20Regions.

- Aggarwal, R. , Chiu, N., Loccoh, E. C., Kazi, D. S., Yeh, R. W., & Wadhera, R. K. Rural-Urban Disparities: Diabetes, Hypertension, Heart Disease, and Stroke Mortality Among Black and White Adults, 1999-2018. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2021, 77, 1480–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D. D. , & Franco, S. J. 2013 NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. Vital and health statistics. Series 2, Data evaluation and methods research.

- Joinpoint Trend Analysis Software. Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 5.3.0 (released , 2024). Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. Accessed March 18, 2025. Available from: https://surveillance.cancer. 12 November.

- Anderson, R. N. , & Rosenberg, H. M. Age standardization of death rates: implementation of the year 2000 standard. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, 1998, 47, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, R. L. , Miller, K. D., & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2018, 68, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thun, M. J. , Lally, C. A., Flannery, J. T., Calle, E. E., Flanders, W. D., & Heath, C. W., Jr Cigarette smoking and changes in the histopathology of lung cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1997, 89, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, S. , Shen, R., Ang, D. C., Johnson, M. L., D’Angelo, S. P., Paik, P. K., Brzostowski, E. B., Riely, G. J., Kris, M. G., Zakowski, M. F., & Ladanyi, M. Molecular epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS mutations in 3,026 lung adenocarcinomas: higher susceptibility of women to smoking-related KRAS-mutant cancers. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2012, 18, 6169–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollerup, S. , Berge, G., Baera, R., Skaug, V., Hewer, A., Phillips, D. H., Stangeland, L., & Haugen, A. Sex differences in risk of lung cancer: Expression of genes in the PAH bioactivation pathway in relation to smoking and bulky DNA adducts. International journal of cancer 2006, 119, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uppstad, H. , Osnes, G. H., Cole, K. J., Phillips, D. H., Haugen, A., & Mollerup, S. Sex differences in susceptibility to PAHs is an intrinsic property of human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2011, 71, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayiner, A. , Hague, C., Ajlan, A., Leipsic, J., Wierenga, L., Krowchuk, N. M., Ceylan, N., Sayiner, A., Sin, D. D., & Coxson, H. O. Bronchiolitis in young female smokers. Respiratory medicine 2013, 107, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Torres, J. P. , Casanova, C., Montejo de Garcini, A., Aguirre-Jaime, A., & Celli, B. R. Gender and respiratory factors associated with dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory research 2007, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F. J. , Curtis, J. L., Sciurba, F., Mumford, J., Giardino, N. D., Weinmann, G., Kazerooni, E., Murray, S., Criner, G. J., Sin, D. D., Hogg, J., Ries, A. L., Han, M., Fishman, A. P., Make, B., Hoffman, E. A., Mohsenifar, Z., Wise, R., & National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group Sex differences in severe pulmonary emphysema. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2007, 176, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J. B. , Kau, T. Y., Severson, R. K., & Kalemkerian, G. P. Lung cancer in women: analysis of the national Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Chest 2005, 127, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaka, M. , Lehman, A., Chlebowski, R., Haynes, B. M., Ho, G., Patel, M., Sakoda, L. C., Schwartz, A. G., Simon, M. S., & Cote, M. L. COPD and lung cancer incidence in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study: A brief report. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2020, 141, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, D. R. , Boffetta, P., Duell, E. J., Bickeböller, H., Rosenberger, A., McCormack, V., Muscat, J. E., Yang, P., Wichmann, H. E., Brueske-Hohlfeld, I., Schwartz, A. G., Cote, M. L., Tjønneland, A., Friis, S., Le Marchand, L., Zhang, Z. F., Morgenstern, H., Szeszenia-Dabrowska, N., Lissowska, J., Zaridze, D., … Hung, R. J. Previous lung diseases and lung cancer risk: a pooled analysis from the International Lung Cancer Consortium. American journal of epidemiology 2012, 176, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, R. S. , Stover, D. E., Shi, W., & Venkatraman, E. Prevalence of COPD in women compared to men around the time of diagnosis of primary lung cancer. Chest 2006, 129, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinwong, D. , Mookmanee, N., Chongpornchai, J., & Chinwong, S. A Comparison of Gender Differences in Smoking Behaviors, Intention to Quit, and Nicotine Dependence among Thai University Students. Journal of addiction 2018, 2018, 8081670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. , Badrick, E., Mathur, R., & Hull, S. Effect of ethnicity on the prevalence, severity, and management of COPD in general practice. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 2012, 62, e76–e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatila, W. M. , Wynkoop, W. A., Vance, G., & Criner, G. J. Smoking patterns in African Americans and whites with advanced COPD. Chest 2004, 125, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes P., J. Genetics and pulmonary medicine. 9. Molecular genetics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999, 54, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A. G. , & Swanson, G. M. Lung carcinoma in African Americans and whites. A population-based study in metropolitan Detroit, Michigan. Cancer, 1997, 79, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, dP. , & Dransfield, M. T. Racial and sex differences in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease susceptibility, diagnosis, and treatment. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine 2009, 15, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C. L. , & Camargo, C. A., Jr Racial and ethnic differences in emergency care for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine 2009, 16, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. G. , Arnaoutakis, G. J., Orens, J. B., McDyer, J., Conte, J. V., Shah, A. S., & Merlo, C. A. Insurance status is an independent predictor of long-term survival after lung transplantation in the United States. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation 2011, 30, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. G. , Hayanga, J. W. A., Tuft, M., Morrell, M. R., & Sanchez, P. G. Access to Lung Transplantation in the United States: The Potential Impact of Access to a High-volume Center. Transplantation 2020, 104, e199–e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thun MJ, Henley SJ, Travis WD. Lung cancer. In: Thun MJ, Linet MS, Cerhan JR, Haiman CA, Schottenfeld D, eds. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017:665-692.

- Berrington de González A, Bouville A, Rajaraman P, Schubauer-Berigan M. Chapter 13: Ionizing Radiation. Schottenfeld and Fraumeni Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. 4 ed. O: New York, NY, 2018.

- Shreves, A. H. , Buller, I. D., Chase, E., Creutzfeldt, H., Fisher, J. A., Graubard, B. I., Hoover, R. N., Silverman, D. T., Devesa, S. S., & Jones, R. R. Geographic Patterns in U.S. Lung Cancer Mortality and Cigarette Smoking. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 2023, 32, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaway, M. S. , Berens, A. S., Puckett, M. C., & Foster, S. Understanding geographic variations of indoor radon potential for comprehensive cancer control planning. Cancer causes & control : CCC 2019, 30, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maine Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. Lung cancer screening: availability of low-dose computed tomography services in Maine. Augusta, ME: Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/population-health/ccc/documents/Availability_2017-LDCT-Services_SurveySummary.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State-Specific Smoking-Attributable Mortality and Years of Potential Life Lost --- United States, 2000–2004. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. 2009.

- Shreves, A. H. , Buller, I. D., Chase, E., Creutzfeldt, H., Fisher, J. A., Graubard, B. I., Hoover, R. N., Silverman, D. T., Devesa, S. S., & Jones, R. R. Geographic Patterns in U.S. Lung Cancer Mortality and Cigarette Smoking. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 2023, 32, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Status of Women Data. Gender differences in sectors of employment. Accessed , 2025. https://statusofwomendata. 6 May.

- Locke, S. J. , Colt, J. S., Stewart, P. A., Armenti, K. R., Baris, D., Blair, A., Cerhan, J. R., Chow, W. H., Cozen, W., Davis, F., De Roos, A. J., Hartge, P., Karagas, M. R., Johnson, A., Purdue, M. P., Rothman, N., Schwartz, K., Schwenn, M., Severson, R., Silverman, D. T., … Friesen, M. C. Identifying gender differences in reported occupational information from three US population-based case-control studies. Occupational and environmental medicine 2014, 71, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, A. , Harbin, S., Irvin, E., Johnston, H., Begum, M., Tiong, M., Apedaile, D., Koehoorn, M., & Smith, P. Differences between men and women in their risk of work injury and disability: A systematic review. American journal of industrial medicine 2022, 65, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dransfield, M. T. , Davis, J. J., Gerald, L. B., & Bailey, W. C. Racial and gender differences in susceptibility to tobacco smoke among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory medicine 2006, 100, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, F. , Voican, S. C., & Silosi, I. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha serum levels in healthy smokers and nonsmokers. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2010, 5, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacievliyagil, S. S. , Mutlu, L. C., & Temel, İ. Airway inflammatory markers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and healthy smokers. Nigerian journal of clinical practice 2013, 16, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovina, N. , Papapetropoulos, A., Kollintza, A., Michailidou, M., Simoes, D. C., Roussos, C., & Gratziou, C. Vascular endothelial growth factor: an angiogenic factor reflecting airway inflammation in healthy smokers and in patients with bronchitis type of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Respiratory research 2007, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thandra, K. C. , Barsouk, A., Saginala, K., Aluru, J. S., & Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Contemporary oncology (Poznan, Poland), 2021, 25, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet J., M. The epidemiology of lung cancer. Chest 1993, 103(1 Suppl), 20S–29S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, P. , & Munden, R. F. Lung cancer epidemiology, risk factors, and prevention. Radiologic clinics of North America 2012, 50, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Romero, C. , Arrieta, O., & Hernández-Pando, R. Tuberculosis and lung cancer. Tuberculosis y cáncer de pulmón. Salud publica de Mexico 2019, 61, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florez, N. , Kiel, L., Riano, I., Patel, S., DeCarli, K., Dhawan, N., Franco, I., Odai-Afotey, A., Meza, K., Swami, N., Patel, J., & Sequist, L. V. Lung Cancer in Women: The Past, Present, and Future. Clinical lung cancer 2024, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| YEAR | METROPOLITAN | NON-METROPOLITAN |

|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 10.92 (10.75 - 11.09) |

13.42 (13.03 - 13.81) |

| 2000 | 10.84 (10.67 - 11.01) |

13.92 (13.52 - 14.32) |

| 2001 | 10.74 (10.57 - 10.90) |

14.17 (13.77 - 14.58) |

| 2002 | 10.81 (10.65 - 10.98) |

14.68 (14.27 - 15.08) |

| 2003 | 10.61 (10.45 - 10.77) |

14.66 (14.25 - 15.06) |

| 2004 | 10.76 (10.59 - 10.92) |

14.75 (14.34 - 15.15) |

| 2005 | 10.88 (10.71 - 11.04) |

15.08 (14.67 - 15.48) |

| 2006 | 10.77 (10.61 - 10.93) |

14.76 (14.37 - 15.16) |

| 2007 | 10.76 (10.60 - 10.92) |

15.37 (14.97 - 15.78) |

| 2008 | 9.43 (9.28 - 9.57) |

13.36 (12.99 - 13.74) |

| 2009 | 9.50 (9.35 - 9.65) |

13.32 (12.95 - 13.69) |

| 2010 | 9.57 (9.42 - 9.72) |

13.38 (13.01 - 13.75) |

| 2011 | 9.25 (9.10 - 9.39) |

13.59 (13.22 - 13.96) |

| 2012 | 9.25 (9.11 - 9.39) |

13.27 (12.91 - 13.63) |

| 2013 | 9.17 (9.03 - 9.30) |

13.25 (12.89 - 13.61) |

| 2014 | 8.69 (8.56 - 8.82) |

12.90 (12.55 - 13.25) |

| 2015 | 8.46 (8.33 - 8.59) |

13.13 (12.78 - 13.48) |

| 2016 | 8.53 (8.40 - 8.66) |

12.98 (12.63 - 13.32) |

| 2017 | 8.15 (8.03 - 8.27) |

12.97 (12.62 - 13.31) |

| 2018 | 7.87 (7.75 - 7.99) |

12.78 (12.44 - 13.12) |

| 2019 | 7.88 (7.76 - 8.00) |

12.60 (12.27 - 12.93) |

| 2020 | 7.86 (7.74 - 7.98) |

12.94 (12.61 - 13.28) |

| Year | Female | Overall | Male |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 8.03 (7.86 - 8.21) |

11.37 (11.21 - 11.52) |

16.32 (16.03 - 16.62) |

| 2000 | 8.18 (8.01 - 8.36) |

11.39 (11.23 - 11.55) |

16.14 (15.85 - 16.44) |

| 2001 | 8.39 (8.22 - 8.57) |

11.35 (11.20 - 11.51) |

15.74 (15.46 - 16.03) |

| 2002 | 8.57 (8.39 - 8.75) |

11.54 (11.38 - 11.69) |

15.87 (15.59 - 16.16) |

| 2003 | 8.57 (8.40 - 8.75) |

11.34 (11.19 - 11.50) |

15.35 (15.07 - 15.62) |

| 2004 | 8.69 (8.52 - 8.87) |

11.47 (11.32 - 11.62) |

15.44 (15.16 - 15.71) |

| 2005 | 8.87 (8.69 - 9.05) |

11.66 (11.51 - 11.81) |

15.57 (15.30 - 15.85) |

| 2006 | 8.79 (8.62 - 8.97) |

11.48 (11.33 - 11.63) |

15.31 (15.04 - 15.58) |

| 2007 | 9.10 (8.92 - 9.27) |

11.59 (11.44 - 11.74) |

15.09 (14.82 - 15.35) |

| 2008 | 8.07 (7.91 - 8.24) |

10.14 (10.00 - 10.28) |

13.03 (12.78 - 13.27) |

| 2009 | 8.17 (8.01 - 8.34) |

10.18 (10.04 - 10.32) |

12.97 (12.73 - 13.21) |

| 2010 | 8.16 (8.00 - 8.33) |

10.25 (10.11 - 10.39) |

13.11 (12.87 - 13.35) |

| 2011 | 8.06 (7.90 - 8.22) |

10.00 (9.86 - 10.13) |

12.63 (12.40 - 12.86) |

| 2012 | 8.15 (7.99 - 8.31) |

9.94 (9.81 - 10.07) |

12.35 (12.13 - 12.58) |

| 2013 | 8.13 (7.97 - 8.29) |

9.88 (9.75 - 10.01) |

12.18 (11.96 - 12.40) |

| 2014 | 7.79 (7.64 - 7.94) |

9.41 (9.28 - 9.53) |

11.57 (11.36 - 11.78) |

| 2015 | 7.71 (7.56 - 7.86) |

9.26 (9.14 - 9.39) |

11.28 (11.08 - 11.49) |

| 2016 | 7.65 (7.50 - 7.80) |

9.29 (9.16 - 9.41) |

11.42 (11.22 - 11.62) |

| 2017 | 7.49 (7.34 - 7.63) |

8.97 (8.85 - 9.09) |

10.84 (10.65 - 11.04) |

| 2018 | 7.23 (7.09 - 7.37) |

8.68 (8.56 - 8.79) |

10.59 (10.40 - 10.78) |

| 2019 | 7.28 (7.14 - 7.42) |

8.68 (8.57 - 8.79) |

10.49 (10.30 - 10.68) |

| 2020 | 7.35 (7.22 - 7.49) |

8.72 (8.61 - 8.83) |

10.42 (10.23 - 10.60) |

|

Year |

NH American Indian Or Alaska Native | NH Asian Or Pacific Islander | NH Black Or African American | NH White |

Hispanic Or Latino |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 8.26 (6.29 - 10.66) |

3.47 (2.87 - 4.07) |

9.47 (8.97 - 9.97) |

12.23 (12.05 - 12.41) |

4.10 (3.65 - 4.54) |

| 2000 | 7.76 (5.83 - 10.12) |

3.40 (2.82 - 3.98) |

9.40 (8.90 - 9.89) |

12.35 (12.17 - 12.52) |

3.83 (3.40 - 4.25) |

| 2001 | 8.91 (6.92 - 11.30) |

3.61 (3.04 - 4.18) |

8.77 (8.30 - 9.24) |

12.36 (12.19 - 12.54) |

3.88 (3.46 - 4.29) |

| 2002 | 9.83 (7.72 - 12.35) |

3.73 (3.16 - 4.31) |

8.83 (8.36 - 9.30) |

12.62 (12.44 - 12.79) |

3.80 (3.41 - 4.20) |

| 2003 | 10.06 (7.98 - 12.52) |

3.07 (2.57 - 3.56) |

9.04 (8.57 - 9.51) |

12.45 (12.27 - 12.63) |

3.53 (3.16 - 3.91) |

| 2004 | 11.48 (9.15 - 13.81) |

3.42 (2.92 - 3.92) |

8.79 (8.33 - 9.25) |

12.64 (12.46 - 12.81) |

3.84 (3.47 - 4.22) |

| 2005 | 10.47 (8.36 - 12.95) |

3.49 (2.99 - 4.00) |

8.85 (8.40 - 9.31) |

12.87 (12.69 - 13.05) |

3.98 (3.61 - 4.36) |

| 2006 | 9.86 (7.86 - 12.20) |

3.45 (2.96 - 3.94) |

8.80 (8.35 - 9.25) |

12.77 (12.59 - 12.94) |

3.51 (3.16 - 3.85) |

| 2007 | 13.03 (10.68 - 15.39) |

3.55 (3.07 - 4.02) |

8.92 (8.47 - 9.36) |

12.89 (12.71 - 13.07) |

3.65 (3.31 - 3.99) |

| 2008 | 9.85 (7.90 - 12.14) |

2.79 (2.38 - 3.20) |

7.84 (7.42 - 8.25) |

11.27 (11.11 - 11.43) |

3.08 (2.78 - 3.39) |

| 2009 | 8.01 (6.34 - 9.99) |

2.61 (2.22 - 3.01) |

7.76 (7.35 - 8.17) |

11.38 (11.22 - 11.54) |

3.31 (3.00 - 3.62) |

| 2010 | 11.90 (9.70 - 14.09) |

2.62 (2.24 - 3.00) |

8.05 (7.64 - 8.46) |

11.46 (11.30 - 11.62) |

3.10 (2.80 - 3.39) |

| 2011 | 8.87 (7.07 - 10.68) |

2.46 (2.11 - 2.81) |

7.53 (7.13 - 7.92) |

11.32 (11.16 - 11.48) |

3.11 (2.83 - 3.40) |

| 2012 | 9.40 (7.57 - 11.23) |

2.31 (1.98 - 2.64) |

8.02 (7.62 - 8.42) |

11.26 (11.10 - 11.42) |

2.73 (2.47 - 2.99) |

| 2013 | 9.33 (7.60 - 11.07) |

2.32 (2.00 - 2.65) |

7.90 (7.51 - 8.29) |

11.21 (11.05 - 11.36) |

3.18 (2.91 - 3.45) |

| 2014 | 8.95 (7.29 - 10.61) |

2.33 (2.03 - 2.64) |

7.07 (6.70 - 7.43) |

10.76 (10.61 - 10.91) |

2.90 (2.64 - 3.15) |

| 2015 | 9.77 (8.11 - 11.43) |

2.28 (1.99 - 2.58) |

7.13 (6.77 - 7.48) |

10.63 (10.48 - 10.78) |

2.68 (2.44 - 2.91) |

| 2016 | 7.74 (6.31 - 9.16) |

2.05 (1.77 - 2.32) |

7.37 (7.02 - 7.73) |

10.63 (10.48 - 10.78) |

2.93 (2.69 - 3.18) |

| 2017 | 9.30 (7.73 - 10.87) |

2.11 (1.84 - 2.38) |

7.08 (6.74 - 7.43) |

10.36 (10.21 - 10.50) |

2.49 (2.28 - 2.71) |

| 2018 | 9.55 (8.01 - 11.09) |

1.91 (1.66 - 2.17) |

6.94 (6.60 - 7.27) |

10.10 (9.96 - 10.24) |

2.36 (2.16 - 2.57) |

| 2019 | 9.54 (8.04 - 11.04) |

1.89 (1.65 - 2.13) |

6.76 (6.44 - 7.09) |

10.13 (9.99 - 10.27) |

2.49 (2.29 - 2.70) |

| 2020 | 9.84 (8.34 - 11.34) |

1.92 (1.69 - 2.16) |

7.19 (6.86 - 7.51) |

10.13 (9.99 - 10.27) |

2.50 (2.30 - 2.70) |

| Variable | COPD and lung cancer Deaths | Age Adjusted Mortality Rate (AAMR) per 100,000 |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Population | 484,941 | 10.14 (10.12 - 10.17) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 269,052 | 13.02 (12.97 - 13.07) |

| Female | 215,889 | 8.02 (7.98 - 8.05) |

| US Census Region | ||

| Northeast | 78,941 | 8.53 (8.47 - 8.59) |

| Midwest | 127,180 | 11.89 (11.82 - 11.95) |

| South | 191,362 | 10.80 (10.76 - 10.85) |

| West | 87,458 | 8.60 (8.55 - 8.66) |

| Race / Ethnicity | ||

| NH American Indian or Alaska Native | 2,476 | 9.58 (9.18 - 9.97) |

| NH Asian or Pacific Islander | 4,367 | 2.54 (2.47 - 2.62) |

| NH Black or African American | 34,577 | 7.91 (7.83 - 8.00) |

| NH White | 432,331 | 11.39 (11.35 - 11.42) |

| Hispanic / Latino | 1,011 | 4.36 (4.09 - 4.64) |

| Urban/ Rural | ||

|

Urban |

369,029 (100%) |

9.41 (9.38 - 9.44) |

| Rural |

115,912 (100%) |

13.60 (13.52 - 13.68) |

| Variable | Trend Segment | Segment End points | APC (95% CI) | AAPC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Overall Population |

1 | 1999 – 2005 | 0.078(-1.19 to 1.36) | -1.40(-1.80 to -1.00) |

| 2 |

2005 – 2020 |

-1.99(-2.30 to -1.69) |

||

| Sex | ||||

|

Female |

1 | 1999 – 2005 | 1.51(0.25 to 2.78) | -1(-1 to -0) |

|

|

2 |

2005 – 2020 |

-1.37(-1.65 to -1.09) |

|

| Male | 1 | 1999 – 2006 | -0.77(-1.33 to -2.07 | -2(-3 to -2) |

| 2 | 2006 – 2009 | -5.13(-8.96 to -1.13) | ||

| 3 | 2009 – 2020 | -2.16(-2.43 to -1.88) | ||

| US Census Region | ||||

|

Northeast |

1 | 1999 – 2006 | 0.16(-1.10 to 1.44) | -1.81(-2.30 to -1.33) |

| 2 | 2006 – 2020 | -2.79(-3.24 to -2.33) | ||

| Midwest | 1 | 1999 – 2005 | 0.97(-0.55 to 2.51) | -0.95(-1.42 to -0.49) |

| 2 | 2005 – 2020 | -1.71(-2.07 to -1.36) | ||

|

South |

1 | 1999 – 2006 | 0.19(-0.51 to 0.90) | -0.87(-1.60 to -0.15) |

| 2 | 2006 – 2009 | -4.27(-9.15 to 0.87) | ||

| 3 | 2009 – 2020 | -0.60(-0.93 to -0.28) | ||

|

West |

1 | 1999 – 2005 | -0.19 (-1.68 to 1.30) | -2.50(-2.96 to -2.05) |

| 2 | 2005 – 2020 | -3.41(-3.77 to -3.05) | ||

| Race / Ethnicity a | ||||

| NH American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | 1999 – 2020 | -0.26(-1.16 to 0.64) | -0.26(-1.16 to 0.64) |

|

Hispanic / Latino |

1 | 1999 – 2020 | -2.52(-2.93 to -2.11) | -2.52(-2.93 to -2.11) |

|

NH Black or African American |

-1.55(-1.80 to -1.30) |

|||

| 1 |

1999 – 2020 |

-1.55(-1.80 to -1.30) |

||

| NH White | 1 | 1999 – 2005 | 0.46(-0.85 to 1.79) | -1.03(-1.44 to -0.63) |

| 2 |

2005 – 2020 |

-1.63(-1.94 to -1.31) |

||

|

NH Asian or Pacific Islander |

1 | 1999 – 2007 | -0.52(-2.14 to 1.13) | -2.93(-4.84 to -0.98) |

| 2 | 2007 – 2010 | -9.30(-21.32 to 4.57) | ||

| 3 | 2010 – 2020 | -2.86(-3.82 to -1.88) | ||

| Urban/Rural | ||||

| Urban | 1 |

1999 – 2005 |

-1.30(-1.35 to 1.10) |

-1.63(-2.00 to -1.25) |

| 2 | 2005 – 2020 | -2.22(-2.52 to -1.93) |

||

| Rural | 1 | 1999 – 2006 | 1.55(1.03 to 2.07) | |

| 2 | 2006 – 2009 | -4.23(-7.69 to -0.60) | -0.33(-0.86 to 0.18) |

|

| 3 | 2009 – 2020 | -0.46(-0.70 to -0.21) | ||

| States | Deaths | AAMR |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 7,784 | 10.04 (9.82 - 10.26) |

| Alaska | 701 | 10.55 (9.73 - 11.38) |

| Arizona | 5,913 | 5.76 (5.61 - 5.90) |

| Arkansas | 5,357 | 11.03 (10.74 - 11.33) |

| California | 44,340 | 8.72 (8.63 - 8.80) |

| Colorado | 6,131 | 9.32 (9.08 - 9.56) |

| Connecticut | 5,421 | 9.05 (8.80 - 9.29) |

| Delaware | 1,623 | 10.75 (10.22 - 11.27) |

| District of Columbia | 487 | 5.83 (5.31 - 6.35) |

| Florida | 32,947 | 8.70 (8.61 - 8.80) |

| Georgia | 10,481 | 8.36 (8.20 - 8.52) |

| Hawaii | 1,109 | 4.88 (4.59 - 5.17) |

| Idaho | 2,172 | 9.55 (9.15 - 9.95) |

| Illinois | 17,601 | 9.20 (9.06 - 9.33) |

| Indiana | 14,863 | 14.87 (14.63 - 15.11) |

| Iowa | 6,744 | 12.72 (12.41 - 13.02) |

| Kansas | 4,886 | 10.95 (10.64 - 11.26) |

| Kentucky | 12,451 | 18.06 (17.74 - 18.38) |

| Louisiana | 5,166 | 7.63 (7.42 - 7.84) |

| Maine | 3,003 | 12.10 (11.66 - 12.54) |

| Maryland | 8,446 | 10.00 (9.78 - 10.21) |

| Massachusetts | 7,943 | 7.33 (7.17 - 7.49) |

| Michigan | 17,995 | 11.09 (10.93 - 11.25) |

| Minnesota | 8,521 | 10.48 (10.25 - 10.70) |

| Mississippi | 5,033 | 11.10 (10.79 - 11.41) |

| Missouri | 12,499 | 12.76 (12.53 - 12.98) |

| Montana | 1,683 | 9.84 (9.37 - 10.32) |

| Nebraska | 4,017 | 13.83 (13.40 - 14.26) |

| Nevada | 2,619 | 6.92 (6.65 - 7.19) |

| New Hampshire | 2,359 | 11.06 (10.61 - 11.51) |

| New Jersey | 10,663 | 7.59 (7.44 - 7.73) |

| New Mexico | 2,133 | 6.79 (6.50 - 7.08) |

| New York | 21,391 | 6.90 (6.81 - 7.00) |

| North Carolina | 16,664 | 11.40 (11.22 - 11.57) |

| North Dakota | 1,334 | 11.67 (11.04 - 12.30) |

| Ohio | 28,571 | 14.86 (14.69 - 15.03) |

| Oklahoma | 9,670 | 16.28 (15.96 - 16.61) |

| Oregon | 7,414 | 11.73 (11.46 - 12.00) |

| Pennsylvania | 24,307 | 10.55 (10.42 - 10.68) |

| Rhode Island | 2,435 | 13.34 (12.81 - 13.88) |

| South Carolina | 8,360 | 11.17 (10.93 - 11.41) |

| South Dakota | 1,684 | 12.21 (11.63 - 12.80) |

| Tennessee | 14,590 | 14.43 (14.20 - 14.67) |

| Texas | 35,726 | 11.40 (11.28 - 11.52) |

| Utah | 1,113 | 3.76 (3.54 - 3.98) |

| Vermont | 1,419 | 13.16 (12.47 - 13.85) |

| Virginia | 10,156 | 8.78 (8.60 - 8.95) |

| Washington | 11,268 | 11.40 (11.18 - 11.61) |

| West Virginia | 6,421 | 18.52 (18.06 - 18.97) |

| Wisconsin | 8,465 | 9.17 (8.97 - 9.36) |

| Wyoming | 862 | 10.48 (9.78 - 11.19) |

| Place of Death | Deaths | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Facility | 163245 | 33.67% |

| Decedent’s home | 187,313 | 38.63% |

| Hospice facility | 31,960 | 6.59% |

| Nursing home | 79,904 | 16.48% |

| Other | 21,392 | 4.41% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).