Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Different Types of Fluorophores Used to Detect H2O2

2.1. Tetraphenylamine (TPA) & Tetraphenylethylene (TPE) Based Probes

2.2. Quinoline & Quinolinium Based Probes

2.3. Pinocol Based Fluorescent Probes

2.4. Aldehyde Based Fluorescent Probes

2.5. Hemicyanine Based Fluorescent Probes

2.6. Isophorone Based Fluorescent Probes

2.7. Indole Based Fluorescent Probes

2.8. Chromene Based Fluorescent Probes

2.9. Benzothiazole Based Fluorescent Probes

| Probe | Derivative | Detection method | Analyte | LOD | Animal tissues/ Food samples | Cell imaging | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TPA | F | H2O2 | 0.141 μmol/L | Living normal tissues and tumor | HeLa | [50] |

| 2 | TPA | F | H2O2 | 0.25 mM | - | HeLa | [51] |

| 3 | TPA | C/F | H2O2 | 62 nM | Acute epilepsy & Chronic epilepsy mice | PC12 | [52] |

| 4 | TPA | F | H2O2 | 0.34 μmol/L | Inflammation and ferroptosis mice | HepG2 | [53] |

| 5 | TPA | F | H2O2 | 2.84 µM | Zebrafish | HepG2 | [54] |

| 6 | TPE | F | H2O2 | - | Tobacco leaves | Orin apple calli cells | [55] |

| 7 | TPE | C/F | H2O2 | 3.52 μM | Sugar | MCF-7 | [56] |

| 8 | Quinoline | C/F | H2O2 | 44.6 nM | Zebrafish | HepG2 | [57] |

| 9 | Quinoline | C/F | H2O2 | 23.08 nM | Potato tissues, Milk and Chicken wing | - | [58] |

| 10 | Quinoline | C/F | H2O2 | 0.87 μM | - | HeLa | [59] |

| 11 | Quinolinium | F | H2O2 | 0.17 μM | Diabetic mice | HeLa, HCT116 and 4T1 cells | [60] |

| 12 | Quinolinium | F | H2O2 | 210 nM | RA mice | HeLa | [61] |

| 13 | Quinolinium | C/F | H2O2 | 0.17 μM | Mice | SH-SY5Y | [62] |

| 14 | Quinolinium | F | H2O2 | 13 nM | CIRI rat | SH-SY5Y | [63] |

| 15 | Pinacol | C/F | H2O2 | 40.2 nM | Zebrafish | Raw 264.7 | [64] |

| 16 | Pinacol | F | H2O2 | 0.003 μmol/L | - | HeLa | [65] |

| 17 | Pinacol | F | H2O2 | - | Tumor-bearing mice | A375 cells | [66] |

| 18 | Pinacol | F | H2O2 | 49.74 nM | - | A549 cells | [67] |

| 19 | Pinacol | C/F | H2O2 | 386 nM & 16.8 nM | - | HeLa | [68] |

| 20 | Cinnamaldehyde | F | H2O2 | - | - | HepG2 | [69] |

| 21 | Hydroxybenzaldehyde | C/F | H2O2 | 1.02 mM | Zebrafish, mice and white wine, sugar samples | - | [70] |

| 22 | Carbaldehyde | C/F | H2O2 | - | Cystitis mice | - | [71] |

| 23 | Benzaldehyde | F | H2O2 | 0.14 & 0.37 μm | Mice | HeLa | [72] |

| 24 | Carboxaldehyde | F | H2O2 | 112.6 nM | 4T1 bearing tumor mice | 4T1 | [73] |

| 25 | Hydroxybenzaldehyde | F | H2O2 | - | - | L-02 cells and HeLa, CT26 cells | [74] |

| 26 | Cinnamaldehyde | F | H2O2 | 0.36 μM | Tumor cell pyroptosis | 4T1 | [75] |

| 27 | Hemicyanine | F | H2O2 | 0.53 μM | HIRI and NAFL mice model | - | [76] |

| 28 | Hemicyanine | F | H2O2 | 0.38 μM | Mice tumor tissue | HeLa & A549 cells | [77] |

| 29 | Hemicyanine | C/F | H2O2 | 0.07 μM | Tomato leaves, stems, and roots | - | [78] |

| 30 | Hemicyanine | F | H2O2 | 0.14 µM | 4T1 tumor-bearing mouse | 4T1 | [79] |

| 31 | Hemicyanine | C/F | H2O2 | 0.16 µM | PD-mice | SH-SY5Y | [80] |

| 32 | Hemicyanine | C/F | H2O2 | 0.361 mM | ApoE−/−/HF & ApoE−/−/HF/setanaxib group mice | LOX-1 & IL-1b | [81] |

| 33 | Dicyanoisophorone | F | H2O2 | 76 nM | Zebrafish | HepG2 | [82] |

| 34(i) (ii) | Dicyanoisophorone | F | H2O2 | 4.525 μM | Zebrafish | HeLa | [83] |

| 35 (i) (ii) | Dicyanomethylene | F | H2O2 | - | DU-145 tumor-bearing mice | MCF-10A, MCF-7, and DU-145 cells | [84] |

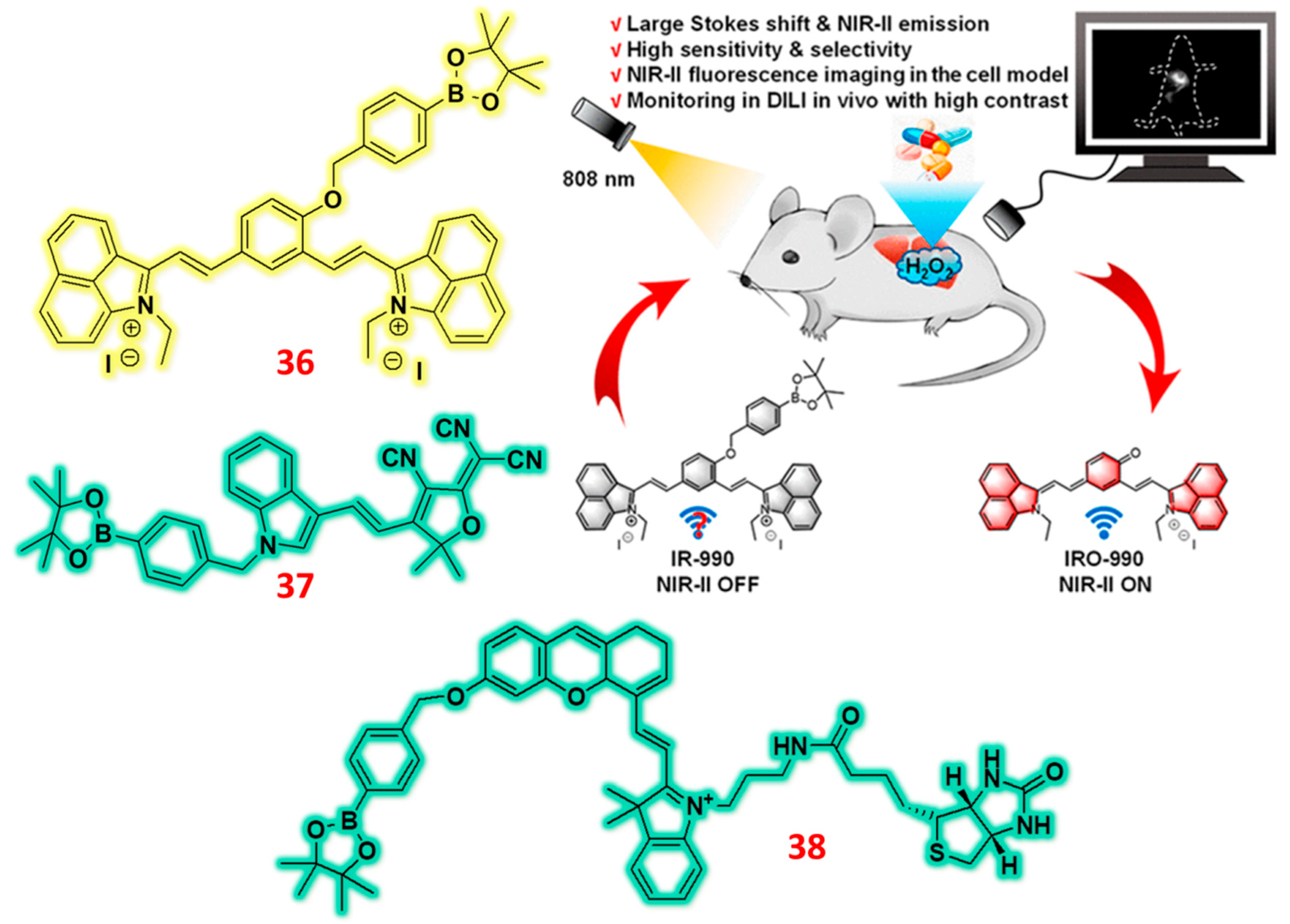

| 36 | Indolium | C/F | H2O2 | 0.59 μM | APAP-induced liver injury mouse | HeLa | [85] |

| 37 | Indole | F | H2O2 | 25.2 nM | Zebrafish | A459 cells | [86] |

| 38 | Trimethylindole | C/F | H2O2 | 1.82 × 10− 7 M | 4T1 mice model | 4T1 cells | [87] |

| 39 | Chromene | C/F | H2O2 | 2.157 μM | Liquor, Red wine, Sugar and Biscuit samples | MCF-7 cells | [88] |

| 40 | Chromene | C/F | H2O2 | 64 nM | Wounded mouse models | HeLa, HACAT | [89] |

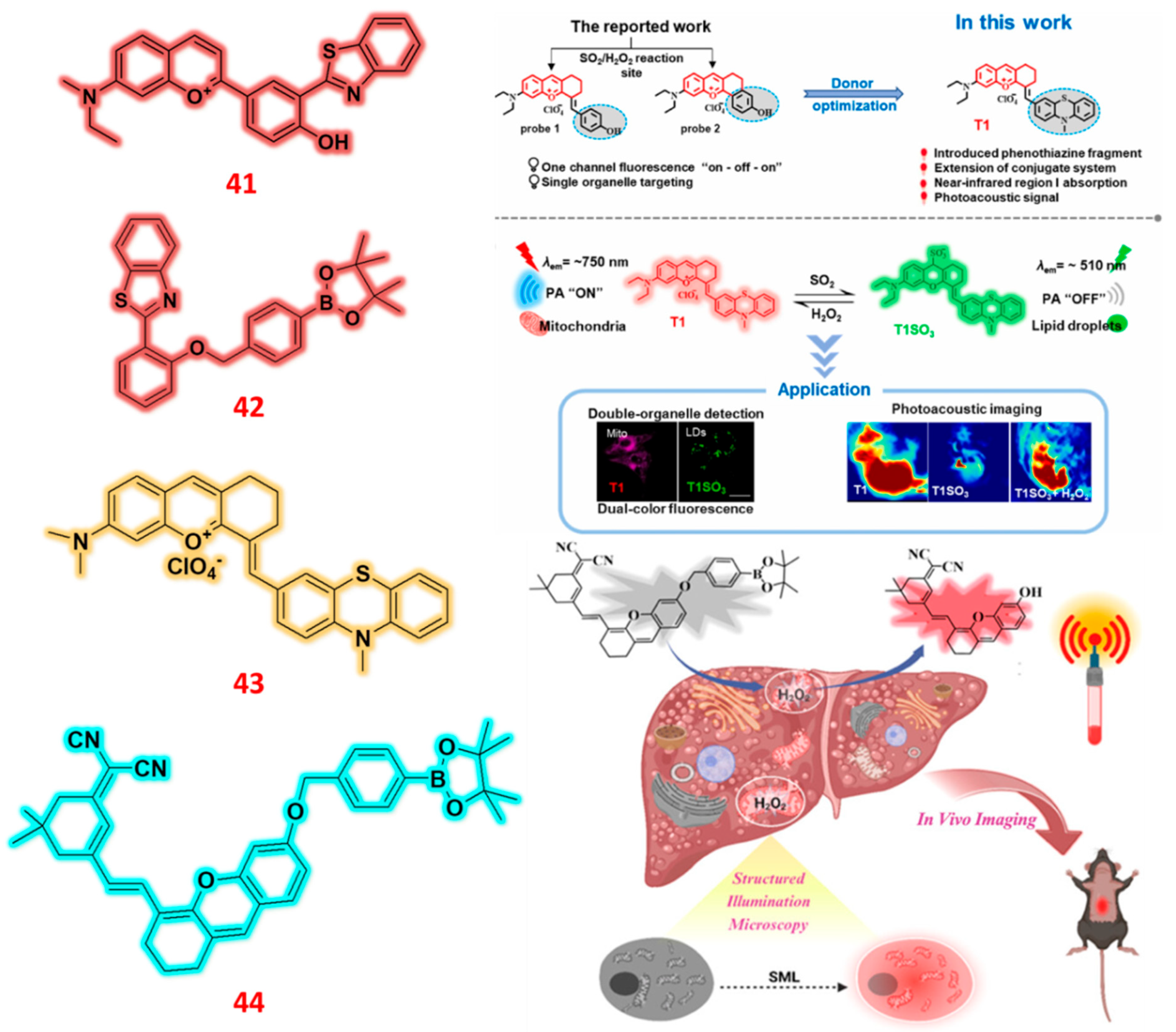

| 41 | Benzothiazole | C/F | H2O2 | 0.152 μM | - | MCF-7 cells | [90] |

| 42 | Benzothiazole | F | H2O2 | 0.93 μM | - | A549 & Hep G2 cells | [91] |

| 43 | Benzopyrylium | C/F | H2O2 | 9.76 × 10− 7 M | Tumor-bearing mice | Hep G2 cells | [92] |

| 44 | Benzopyranonitrile | F | H2O2 | 17 nM | Liver injury mice | L02 and HeLa cells | [93] |

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yin, J.; Huang, L.; Wu, L.; Li, J.; James, T.D.; Lin, W. Small molecule based fluorescent chemosensors for imaging the microenvironment within specific cellular regions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 12098–12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Feng, S.; Gong, S.; Feng, G. Golgi-targetable fluorescent probe for ratiometric imaging of CO in cells and zebrafish. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2021, 347, 130631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Xia, S.; Wan, S.; Steenwinkel, T.E.; Medford, J.; Durocher, E.; Luck, R.L.; Werner, T.; Liu, H. Cell Membrane-Specific Fluorescent Probe Featuring Dual and Aggregation-Induced Emissions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 20172–20179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Pan, S.; Yuan, B.; Wang, N.; Shao, L.; Chen, Z.E.; Zhang, H.; Huang, W.Z. Recent Research Progress of Benzothiazole Derivative Based Fluorescent Probes for Reactive Oxygen (H2O2 HClO) and Sulfide (H2S) Recognition. J. Fluoresc. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Huang, C.; Jia, N. A new mitochondria-targeting fluorescent probe for ratiometric detection of H2O2 in live cells. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1097, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, C.; Jia, L. Recent Progress in Organic Small-Molecule Fluorescent Probe Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 15267–15274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Bai, S.; He, N.; Wang, R.; Xing, Y.; Lv, C.; Yu, F. Real-Time Evaluation of Hydrogen Peroxide Injuries in Pulmonary Fibrosis Mice Models with a Mitochondria-Targeted Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe. ACS Sensors 2021, 6, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Bian, C.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, M. Unveiling Cellular Microenvironments with a Near-Infrared Fluorescent Sensor: A Dual-Edge Tool for Cancer Detection and Drug Screening. Anal. Chem. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Huang, H.; Kang, X.; Yang, L.; Xi, Z.; Sun, H.; Pluth, M.D.; Yi, L. NBD-based synthetic probes for sensing small molecules and proteins: design, sensing mechanisms and biological applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 7436–7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Shi, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Meng, C.; Jiao, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; He, Z.; et al. Emerging prodrug and nano-drug delivery strategies for the detection and elimination of senescent tumor cells. Biomaterials 2025, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnendu, M.R.; Singh, S. Reactive oxygen species: Advanced detection methods and coordination with nanozymes. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, V.; Kumari, R.; Sharma, P.; Pati, A.K. Diverse Fluorescent Probe Concepts for Detection and Monitoring of Reactive Oxygen Species. Chem. - An Asian J. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Ye, C.; Lin, Z.; Huang, L.; Li, D. Recent progress of near-infrared fluorescent probes in the determination of reactive oxygen species for disease diagnosis. Talanta 2024, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, K.; Zhao, Y.; Mu, J.; Chen, X. In vivo optical imaging of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-related non-cancerous diseases. TrAC - Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Li, X.; Gao, C.; Tao, J.; Li, W.; Seidu, M.A.; Zhou, H. Oxidative cleavage of alkene: A new strategy to construct a mitochondria-targeted fluorescent probe for hydrogen peroxide imaging in vitro and in vivo. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2023, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Sun, J.; Tang, F.; Xie, R.; Wang, H.; Ding, A.; Pan, S.; Li, L. Mitochondria-Targeting BODIPY Probes for Imaging of Reactive Oxygen Species. Adv. Sens. Res. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Hu, J.J.; Yang, D. Tandem Payne/Dakin Reaction: A New Strategy for Hydrogen Peroxide Detection and Molecular Imaging. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10173–10177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.R.; Cotter, T.G. Hydrogen peroxide: A Jekyll and Hyde signalling molecule. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C. Reconciling the chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.G. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science (80-. ). 2006, 312, 1882–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, M.; Yu, Z.-X.; Ferrans, V.J.; Irani, K.; Finkel, T. Requirement for Generation of H 2 O 2 for Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Signal Transduction. Science (80-. ). 1995, 270, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikun, D.; Albersa, A.E.; Chang, C.J. A dendrimer-based platform for simultaneous dual fluorescence imaging of hydrogen peroxide and pH gradients produced in living cells. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisanti, M.P.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Lin, Z.; Pavlides, S.; Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Pestell, R.G.; Howell, A.; Sotgia, F. Hydrogen peroxide fuels aging, inflammation, cancer metabolism and metastasis: The seed and soil also needs “fertilizer. ” Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2440–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.W.; Tulyanthan, O.; Isacoff, E.Y.; Chang, C.J. Molecular imaging of hydrogen peroxide produced for cell signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezende, F.; Brandes, R.P.; Schröder, K. Detection of hydrogen peroxide with fluorescent dyes. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ma, H. Design principles of spectroscopic probes for biological applications. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 6309–6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, X.; Shi, W.; Ma, H. Design strategies for water-soluble small molecular chromogenic and fluorogenic probes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 590–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, K.P.; Young, A.M.; Palmer, A.E. Fluorescent sensors for measuring metal ions in living systems. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4564–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shao, A.; Zhu, S.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, W. A novel colorimetric and ratiometric NIR fluorescent sensor for glutathione based on dicyanomethylene-4H-pyran in living cells. Sci. China Chem. 2016, 59, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, Y.; Urano, Y.; Hanaoka, K.; Piao, W.; Kusakabe, M.; Saito, N.; Terai, T.; Okabe, T.; Nagano, T. Development of NIR fluorescent dyes based on Si-rhodamine for in vivo imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5029–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Shi, C.; Tong, R.; Qian, W.; Zhau, H.E.; Wang, R.; Zhu, G.; Cheng, J.; Yang, V.W.; Cheng, T.; et al. Near Infrared Heptamethine Cyanine Dye-Mediated Cancer Imaging. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.Y.; Yao, S.; Wang, X.; Belfield, K.D. Near-infrared-emitting squaraine dyes with high 2PA cross-sections for multiphoton fluorescence imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2847–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xia, J.; Tian, R.; Wang, J.; Fan, J.; Du, J.; Long, S.; Song, X.; Foley, J.W.; Peng, X. Near-Infrared Light-Initiated Molecular Superoxide Radical Generator: Rejuvenating Photodynamic Therapy against Hypoxic Tumors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14851–14859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Chen, L.; Xu, Q.; Chen, X.; Yoon, J. Design principles, sensing mechanisms, and applications of highly specific fluorescent probes for HOCl/OCl-. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2158–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabakaran, G.; Xiong, H. Unravelling the recent advancement in fluorescent probes for detection against reactive sulfur species (RSS) in foodstuffs and cell imaging. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabakaran, G.; David, C.I.; Nandhakumar, R. A review on pyrene based chemosensors for the specific detection on d-transition metal ions and their various applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immanuel David, C.; Prabakaran, G.; Nandhakumar, R. Recent approaches of 2HN derived fluorophores on recognition of Al3+ ions: A review for future outlook. Microchem. J. 2021, 169, 106590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Lin, W.; Zheng, K.; Zhu, S. FRET-based small-molecule fluorescent probes: Rational design and bioimaging applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Li, P.; Han, K. Redox-responsive fluorescent probes with different design strategies. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna de Silva, A. *; H. Q. Nimal Gunaratne; Thorfinnur Gunnlaugsson; Allen J. M. Huxley; Colin P. McCoy; Jude T. Rademacher, and; Rice, T.E. Signaling Recognition Events with Fluorescent Sensors and Switches. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1515–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeur, B.; Leray, I. Design principles of fluorescent molecular sensors for cation recognition. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 205, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, G.; Velmurugan, K.; David, C.I.; Nandhakumar, R. Role of Förster Resonance Energy Transfer in Graphene-Based Nanomaterials for Sensing. Appl. Sci. 2022, Vol. 12, Page 6844 2022, 12, 6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, M.H.; Hui, B.Y.K.; Chin, K.L.O.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, X.; Xu, J. Recent advances in aggregation-induced emission (AIE)-based chemosensors for the detection of organic small molecules. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 5561–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Li, M.; Fan, J.; Peng, X. Activity-Based Sensing and Theranostic Probes Based on Photoinduced Electron Transfer. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2818–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, C.; Qi, Q.; Qiao, Q.; Tan, T.M.; Xiong, K.; Liu, X.; Kang, K.; et al. A General Descriptor Δ e Enables the Quantitative Development of Luminescent Materials Based on Photoinduced Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6777–6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Kim, J.S.; Sessler, J.L. Small molecule-based ratiometric fluorescence probes for cations, anions, and biomolecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4185–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.L.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Zhu, T.; Zou, Z.X.; Shan, Q.F.; Huang, Q.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y. Construction of ICT-based fluorescence probes for the imaging of biothios. Microchem. J. 2025, 210, 112968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavadai, R.; Pavadai, N.; Palanisamy, R.; Amalraj, A.; Arivazhagan, M.; Honnu, G.; Kityakarn, S.; Thongmee, S.; Khumphon, J.; Khamboonrueang, D.; et al. Recent Trends and Future Challenges of Metal-Organic Framework-Based optical and electro-chemical sensing platforms for the Ultra-sensitive detection of biomarkers and environmental Contaminants: A review (Year − 2023 & 2024). Microchem. J. 2025, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udhayakumari, D. Mechanistic Innovations in Fluorescent Chemosensors for Detecting Toxic Ions: PET, ICT, ESIPT, FRET and AIE Approaches. J. Fluoresc. 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zan, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Shuang, S.; Dong, C. A Mitochondria-Specific Orange/Near-Infrared-Emissive Fluorescent Probe for Dual-Imaging of Viscosity and H2O2 in Inflammation and Tumor Models. Chinese J. Chem. 2021, 39, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Tang, B.Z. Hydrogen peroxide-responsive AIE probe for imaging-guided organelle targeting and photodynamic cancer cell ablation. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 3489–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, P.; Ye, M.; Yang, K.; Cheng, D.; Mao, Z.; He, L.; Liu, Z. Cysteine-Activatable Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe for Dual-Channel Tracking Lipid Droplets and Mitochondria in Epilepsy. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 5133–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Cheng, J.; Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Yu, M. A NIR Dual-Channel Fluorescent Probe for Fluctuations of Intracellular Polarity and H2O2 and Its Applications for the Visualization of Inflammation and Ferroptosis. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 2024, 2, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Kang, X.; Liu, N.; Zhang, A.; Li, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Deng, Y.; Peng, C.; et al. A robust H2O2-responsive AIEgen with multiple-task performance: Achieving food analysis, visualization of dual organelles and diagnosis of liver injury. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 276, 117276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.F.; Gao, W.; Zhang, S.; You, C. Simple Phenotypic Sensor for Visibly Tracking H2O2Fluctuation to Detect Plant Health Status. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 10058–10064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhong, K.; Tang, L. An AIE mechanism-based fluorescent probe for relay recognition of HSO3−/H2O2 and its application in food detection and bioimaging. Talanta 2023, 258, 124412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, X.; Shi, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H. A novel H2O2 activated NIR fluorescent probe for accurately visualizing H2S fluctuation during oxidative stress. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1202, 339670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; He, D.; Shentu, J.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, K.; Qian, J.; Long, L. Smartphone-assisted colorimetric and near-infrared ratiometric fluorescent sensor for on-spot detection of H2O2 in food samples. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.P.; Jiang, P.F.; Miao, J.Y.; Zhao, B.X.; Lin, Z.M. A near-infrared fluorescent probe based FRET for ratiometric sensing of H2O2 and viscosity in live cells. Talanta 2024, 275, 126135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Wang, W.X.; Jiang, W.L.; Mao, G.J.; Tan, M.; Fei, J.; Li, Y. Monitoring the fluctuation of hydrogen peroxide in diabetes and its complications with a novel near-infrared fluorescent probe. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 3301–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Huang, S.; Feng, B.; Luo, T.; Chu, F.; Zheng, F.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, F.; Zeng, W. An ESIPT-based AIE fluorescent probe to visualize mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide and its application in living cells and rheumatoid arthritis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 5063–5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Iyaswamy, A.; Xu, D.; Krishnamoorthi, S.; Sreenivasmurthy, S.G.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, M.; Li, H.W.; et al. Real-Time Detection and Visualization of Amyloid-β Aggregates Induced by Hydrogen Peroxide in Cell and Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Deng, Q.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, X.; Liu, F.; Yin, P.; Liu, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Fluorescent Probe for Investigating the Mitochondrial Viscosity and Hydrogen Peroxide Changes in Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 3436–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Liang, Z.; Zeng, G.; Wang, Y.; Mai, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, G.; Chen, T. An ESIPT-based NIR-emitting ratiometric fluorescent probe for monitoring hydrogen peroxide in living cells and zebrafish. Dye. Pigment. 2022, 198, 109995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.; Pang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, N. A novel near-infrared fluorescent probe for visualization of intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1025723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wang, T.; Li, G.; Huang, J.; Yuan, Q. Dual-Locked Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probes for Precise Detection of Melanoma via Hydrogen Peroxide–Tyrosinase Cascade Activation. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 1070–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tao, J.; Sun, B.; Song, C.; Qi, M.; Yang, F.; Zhao, M.; Jiang, J. Design, Synthesis of Hydrogen Peroxide Response AIE Fluorescence Probes Based on Imidazo [1,2-a] Pyridine. Molecules 2024, 29, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zang, S.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, B.; Song, X. A bifunctional fluorescent probe for dual-channel detection of H2O2 and HOCl in living cells. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 328, 125464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.; Liu, H.; Gao, X.; Xu, K.; Tang, B. A Mitochondrial-Targeting Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe for Revealing the Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide and Heavy Metal Ions on Viscosity. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 9244–9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, D.; Chi, H.; Jia, H.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, R. A reversible near-infrared fluorescence probe for the monitoring of HSO3−/H2O2-regulated cycles in vivo. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 19011–19018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; He, H.; Wang, S.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, F. ROS/RNS and Base Dual Activatable Merocyanine-Based NIR-II Fluorescent Molecular Probe for in vivo Biosensing. Angew. Chemie 2021, 133, 26541–26545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.X.; Chao, J.J.; Wang, Z.Q.; Liu, T.; Mao, G.J.; Yang, B.; Li, C.Y. Dual Key-Activated Nir-I/II Fluorescence Probe for Monitoring Photodynamic and Photothermal Synergistic Therapy Efficacy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2301230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Cui, M.; Chu, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, P. A novel AIE fluorescent probe for the detection and imaging of hydrogen peroxide in living tumor cells and in vivo. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 150, 107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, L.; Aodeng, G.; Ga, L.; Ai, J. Put one make three: Multifunctional near-infrared fluorescent probe for simultaneous detection of viscosity, polarity, SO2/H2O2. Microchem. J. 2025, 208, 112535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Wang, P.; Zhai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, D.; He, L.; Li, S. A Triple-Responsive and Dual-NIR Emissive Fluorescence Probe for Precise Cancer Imaging and Therapy by Activating Pyroptosis Pathway. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 2998–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, Q.; Zhao, K.; Li, R.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, G.; Dong, C.; Shuang, S.; Fan, L. Mitochondria-Targetable Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe for Visualization of Hydrogen Peroxide in Lung Injury, Liver Injury, and Tumor Models. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 10488–10495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, N.; Wang, Y.; Qin, G.; Wang, M.; Tang, J.; Yao, X.; Xu, Q.; Yoon, J. A mitochondria-targeted fluorescent probe for revealing H2O2 elevation modulated by basal HClO in HeLa and A549 cells. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2024, 419, 136419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Song, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Niu, N.; Chen, L. Development of a near-infrared fluorescent probe for in situ monitoring of hydrogen peroxide in plants. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 339, 126267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Wang, Y.; Hao, Q.; Liu, H. A Hydrogen Peroxide Responsive Biotin-Guided Near-Infrared Hemicyanine-Based Fluorescent Probe for Early Cancer Diagnosis. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, X.; Xie, S.; Su, B.; Yang, N.; Wang, B.; Ma, S.; Li, L.; Yan, L.; Zhang, B.; et al. Double-locked probe for NIRF/PA imaging mitochondrial H2O2 and viscosity in Parkinson’s disease. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2025, 426, 137104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, J.; Xiu, T.; Tang, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Tang, B. H2O2 accumulation promoting internalization of ox-LDL in early atherosclerosis revealed via a synergistic dual-functional NIR fluorescence probe. Chem. Sci. 2024, 16, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunpo, G.; Yan, Y.; Pengfei, T.; Hu, S.; Yibo, J.; Yuyang, S.; Yun, Y.; Feng, R. A NIR fluorescent probe for the in vitro and in vivo selective detection of hydrogen peroxide. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2022, 350, 130831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jing, F.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Fan, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Hou, S. A near-infrared fluorescent probe for tracking endogenous and exogenous H2O2 in cells and zebrafish. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 302, 123158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Deng, X.; Xu, B.; Xie, B.; Zou, W.; Zhou, H.; Dong, C. Development of Highly Efficient Estrogen Receptor β-Targeted Near-Infrared Fluorescence Probes Triggered by Endogenous Hydrogen Peroxide for Diagnostic Imaging of Prostate Cancer. Molecules 2023, 28, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, S.; Cao, W.; Wu, P.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, H. H2O2-Activated NIR-II Fluorescent Probe with a Large Stokes Shift for High-Contrast Imaging in Drug-Induced Liver Injury Mice. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 11321–11328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Sonawane, P.M.; Roychaudhury, A.; Park, S.J.; An, J.; Kim, C.H.; Nimse, S.B.; Churchill, D.G. An indole–based near–infrared fluorescent “Turn–On” probe for H2O2: Selective detection and ultrasensitive imaging of zebrafish gallbladder. Talanta 2024, 269, 125459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, M.; Liu, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, W. H2O2-activated NIR fluorescent probe with tumor targeting for cell imaging and fluorescent-guided surgery. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2024, 418, 136249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Sun, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhong, K.; Li, S.; Yan, X.; Tang, L. Reversible colorimetric and NIR fluorescent probe for sensing SO2/H2O2 in living cells and food samples. Food Chem. 2023, 407, 135031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, W.; Dou, K.; Wang, R.; Yu, F. Near-Infrared Fluorescence Probe for Indication of the Pathological Stages of Wound Healing Process and Its Clinical Application. ACS Sensors 2024, 9, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Tang, L.; Yan, X. A novel “AIE+ESIPT” mechanism-based fluorescent probe for visual alternating recognition of HSO3−/H2O2 and its HSO3− detection in food samples. Dye. Pigment. 2024, 222, 111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Yang, Y.; Tong, L.; Zhang, L.; Yang, F.; Tao, J.; Zhao, M. A Novel Benzothiazole-Based Fluorescent AIE Probe for the Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide in Living Cells. Molecules 2024, 29, 5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ni, Y.; Rao, Q.; Zhu, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, H. A multifunctionally reversible detector: Photoacoustic and dual-channel fluorescence sensing for SO2/H2O2. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1263, 341181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Peng, W.; Liu, M.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Xing, J.; Shi, P.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L. Super-Resolution Mitochondrial Fluorescent Probe for Accurate Monitoring of Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Anal. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Biographies

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).