Introduction

Cognitive workload defined as the mental effort required to process information and execute tasks, plays a critical role in performance, safety, and well-being across a range of high-stakes environments including aviation, healthcare, transportation, and human-computer interaction [

1]. Understanding and accurately assessing cognitive workload is essential for optimizing task efficiency, preventing mental fatigue, and designing adaptive systems that respond intelligently to human limitations. In mixed-initiative systems, where humans and artificial agents collaborate dynamically, it is especially important that the artificial agents are cognitively aware that is, capable of recognizing the mental demands placed on their human counterparts. In such settings, intelligent systems should avoid imposing unnecessary cognitive strain, such as through excessive alerts, irrelevant information delivery, or poorly timed verbal interactions. Designing such adaptive systems requires reliable, real-time measures of cognitive load. In this study, we explore the application of Functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) as a neuroimaging tool to monitor and assess human cognitive workload in a multi-modal driving simulation environment [

2,

3]. fNIRS offers a non-invasive means of measuring cortical hemodynamic responses, particularly within the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with executive functions such as attention, working memory, and decision-making.

Researchers have made significant efforts to develop mental load classification models using various physiological signals, including Electroencephalogram EEG [

4], eye-tracking [

5], and, more recently, fNIRS [

6], particularly within the domain of cognitive load assessment. Numerous machine learning models, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), and Random Forests [2,7-9], as well as deep learning architectures like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [

10,

11], have been employed for this purpose. These models offer distinct advantages in detecting and interpreting cognitive states: they leverage advanced pattern recognition capabilities through optimized function fitting methods, enabling the identification of complex, non-obvious relationships in the data that traditional statistical techniques might overlook [

12,

13]. Furthermore, cross-validation strategies provide a systematic mechanism to verify that cognitive states can be reliably induced and measured across different participants. However, despite these advancements, several limitations remain. The cognitive workload states induced by benchmark tasks may not accurately replicate the natural cognitive demands experienced during real-world activities, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings. Additionally, many studies have relied on proprietary experimental designs, making it difficult to establish standard benchmarks or compare results across different investigations. It also remains uncertain whether methodologies developed for other brain imaging modalities, such as EEG or Functional magnetic resonance imaging fMRI, are directly applicable or optimal for fNIRS data, given its distinct spatial and temporal characteristics.

To investigate varying levels of cognitive workload, we developed a dual-task experimental paradigm in which participants were required to perform a primary driving task concurrently with a secondary cognitive task a modified version of the n-back task delivered through the auditory modality. This setup was designed to replicate the cognitive demands encountered in real-world multitasking situations, such as managing complex navigation while processing verbal information. The n-back task was implemented at three distinct levels of difficulty: 0-back (representing low cognitive workload), 1-back (moderate workload), and 2-back (high workload). By varying the task difficulty, we aimed to elicit clearly differentiated cognitive states that could be measured through physiological responses during the driving simulation. This approach allows us to evaluate the sensitivity and effectiveness of fNIRS in detecting subtle changes in cognitive load under realistic conditions. While previous studies have primarily focused on two-level workload comparisons (e.g., low vs. high), our three-tiered workload design introduces a more granular framework for understanding how cognitive demand span across multiple task intensities. In addition to the experimental design, we employed the EEGNet deep learning architecture to analyze the recorded fNIRS signals. EEGNet, originally developed for EEG data classification, has been adapted in our study to process and classify hemodynamic responses captured by fNIRS, enabling automated workload detection. Importantly, we explored the model’s performance using both overlapping and non-overlapping window segments of the fNIRS signal, an aspect that has been rarely addressed in existing literature. By incorporating these two segmentation strategies, we provide a comparative evaluation of how temporal segmentation influences classification accuracy and model generalizability.

Materials and Methods

Thirty-eight drivers participated in the study. Inclusion criteria required a valid driver’s license and the absence of mental health disorders, neurological conditions, or physical impairments that could affect cognitive function. This ensured consistent cognitive performance across participants, improving the reliability and comparability of the results.

Apparatus

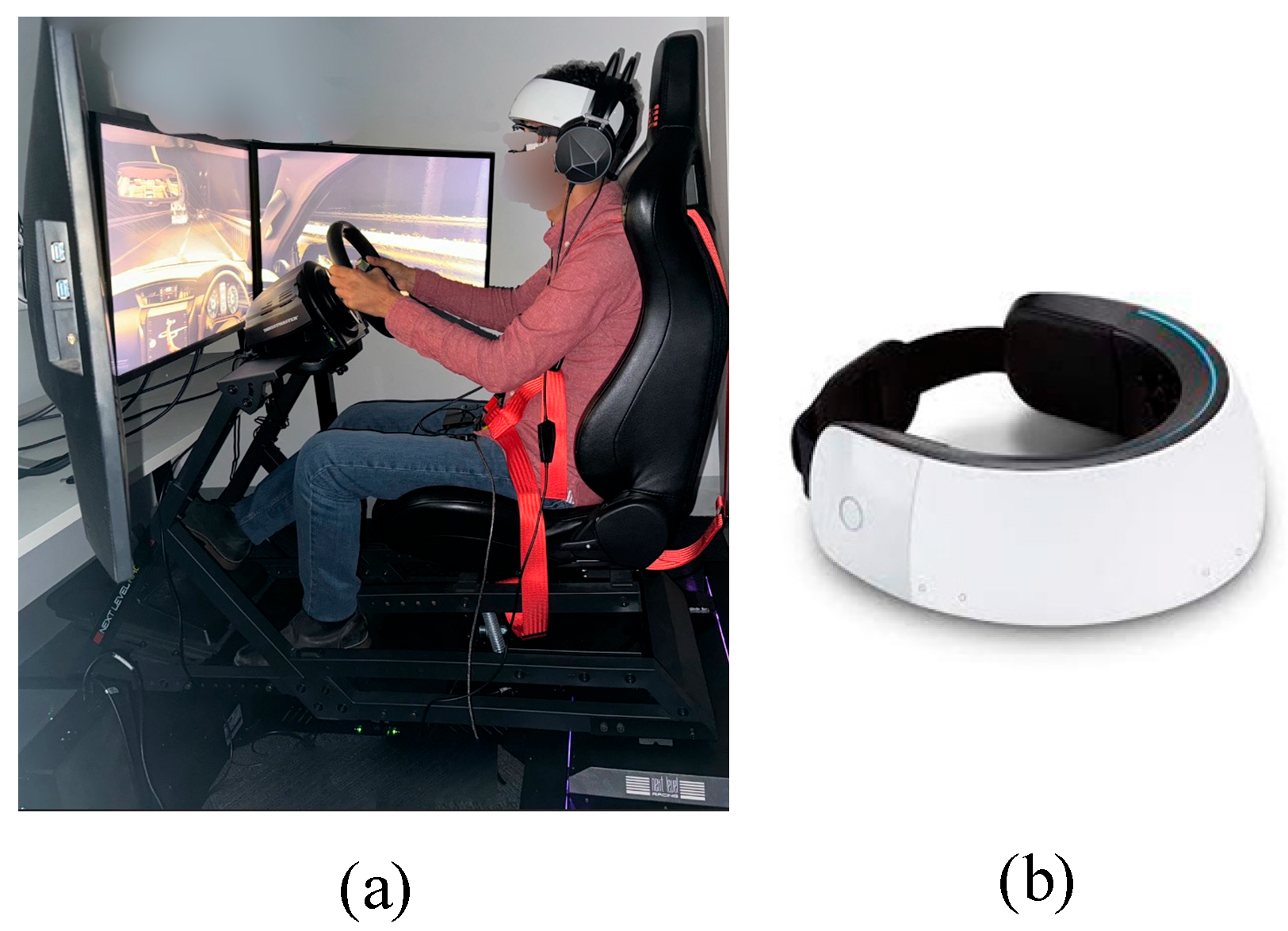

For this study, we employed a high-fidelity driving simulator specifically designed to deliver an immersive and realistic driving experience. Central to the system was the Next Level Racing Motion Platform V3, mounted securely on the Traction Plus Platform. This configuration was selected to maximize the simulation of real-world vehicle dynamics by providing physical feedback for acceleration, braking, road surface texture, and lateral forces. Such detailed motion feedback is critical for enhancing the ecological validity of the simulated driving environment, allowing participants to respond more naturally to vehicle behavior. The visual interface consisted of three 32-inch Samsung monitors arranged in a panoramic setup to create an expansive field of view, closely simulating the peripheral vision critical for real-world driving tasks. This multi-monitor arrangement aimed to enhance situational awareness, depth perception, and hazard anticipation among participants. To further increase realism, the simulator’s control system was calibrated to emulate the driving dynamics and interior cabin layout of a Toyota Fortuner SUV. This ensured consistency across participants in terms of vehicle handling expectations, control ergonomics, and spatial orientation within the virtual environment. The driving scenarios were developed and implemented using Euro Truck Simulator 2 (ETS2), a simulation platform widely recognized for its accurate driving physics and flexible environmental settings. ETS2 enabled the replication of challenging driving conditions, including nighttime driving and heavy rainfall, to systematically induce cognitive workload.

To monitor brain activity during the experiments, we utilized the NIRSIT (OBELAB Inc., South Korea), a high-density, wearable fNIRS device. The NIRSIT system incorporates 24 laser diode light sources and 32 photodetectors, operating at two near-infrared wavelengths (780 nm and 850 nm), optimized for detecting cerebral hemodynamic responses. The overall experimental setup, including the driving simulator and fNIRS device configuration, is illustrated in

Figure 1. a and

Figure 1. b respectively.

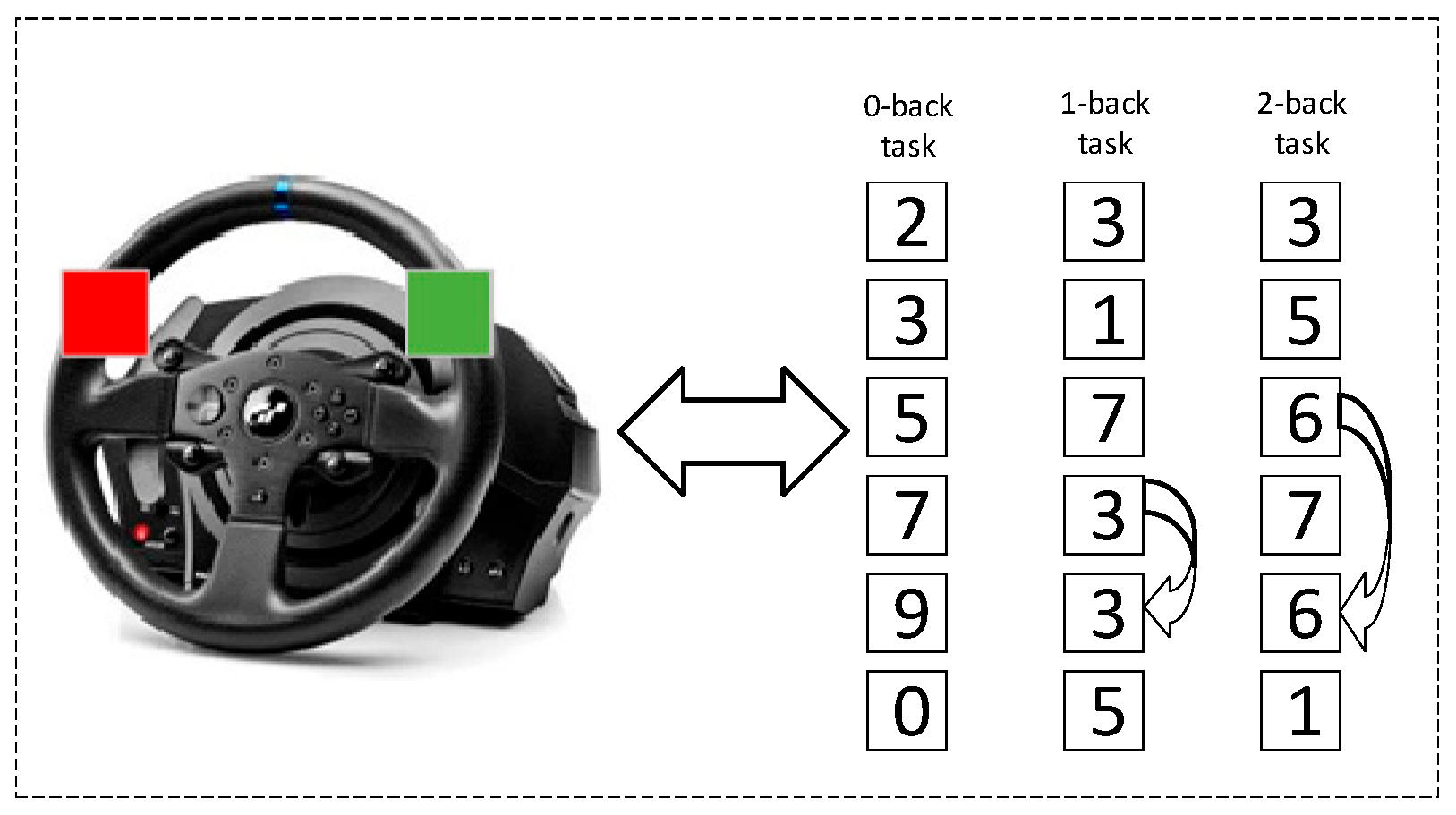

Secondary Task

To simulate realistic multitasking and increase cognitive load during dual-task driving, an auditory-modified n-back task was used. This task targeted working memory and executive function as participants drove in a dynamic scenario. It combined elements of the n-back and digit-span tasks, creating three difficulty levels: 0-back (baseline, minimal effort), 1-back, and 2-back (increasing memory load). Participants responded to spoken digits (0–9) delivered via the simulator’s speakers, using red and green buttons mounted on the steering wheel as shown in

Figure 2. A green button indicated a match with the target digit; a red button indicated a non-match, minimizing physical distraction.

The auditory n-back tasks were developed using PsychoPy [

14], which also recorded button responses. PsychoPy operated in parallel with the driving simulator to maintain an immersive, ecologically valid dual-task environment.

Experimental Procedure

The study will begin with the collection of written informed consent from all participants, ensuring they understand their rights and the voluntary nature of their involvement. Following consent, participants will attend a comprehensive briefing session, where they will receive both verbal and written instructions outlining the study’s objectives, the structure of the experimental tasks, and all relevant safety procedures. After the briefing, participants will undergo a sensor fitting session. They will be equipped with the necessary physiological monitoring devices, including a high-density fNIRS system to continuously record cerebral hemodynamic responses. Once fitted, participants will complete a simulator familiarization phase, allowing them to practice basic driving maneuvers and become comfortable with the controls and environment before testing begins. The experimental phase will involve a series of structured driving tasks performed under challenging simulated conditions, including nighttime driving at approximately 1:00 AM and heavy rainfall, both intended to increase visual and attentional demands. While navigating this environment, participants will simultaneously perform the auditory-modified n-back task at varying levels of difficulty (0-back, 1-back, and 2-back), using red and green buttons mounted on the steering wheel to register their responses. This dual-task setup is designed to elicit working memory and attention, providing a realistic measure of cognitive workload under multitasking conditions. Throughout the session, fNIRS data will be collected to monitor changes in prefrontal cortex oxygenation, capturing neural responses to variations in task difficulty and environmental complexity.

Research Methodology

fNIRS data were acquired at a sampling frequency of 8.138 Hz, providing continuous, high-resolution monitoring of cortical oxygenation dynamics during task performance. The raw optical density signals collected by the fNIRS device were subjected to an initial preprocessing stage using OBELAB’s integrated Digital Signal Processing (DSP) toolkit. This preprocessing pipeline included several critical steps: noise reduction to minimize ambient and physiological interference, motion artifact correction to address signal distortions caused by participant movement, and baseline drift removal to correct for slow fluctuations unrelated to task activity, thereby enhancing the overall quality and interpretability of the signals. Following preprocessing, the concentrations of HbO2 and HbR were computed using the Modified Beer–Lambert Law [

15]. This standard analytical technique translates changes in optical density into quantitative measures of hemodynamic activity, offering insights into underlying neural processes.

Data Pre-Processing

In this study, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to reduce the dimensionality of the full set of 204 fNIRS channel features and to extract the most informative patterns associated with cognitive load during simulated driving scenarios. The primary goal of using PCA was to transform the original high-dimensional dataset into a lower-dimensional space while retaining the most critical information relevant to variance in the data. PCA works by identifying a new set of orthogonal axes, known as principal components, which are derived as linear combinations of the original features. These components are ordered in such a way that the first principal component accounts for the maximum variance in the dataset. The second principal component captures the maximum amount of remaining variance while being orthogonal to the first, and each subsequent component follows this principle of orthogonality and decreasing variance. By projecting the fNIRS signals onto these principal components, we aimed to highlight the dominant patterns in brain activity that correspond to changes in cognitive workload. This transformation not only improves the interpretability of the data but also enhances the efficiency and performance of downstream machine learning models by removing redundancy and noise.

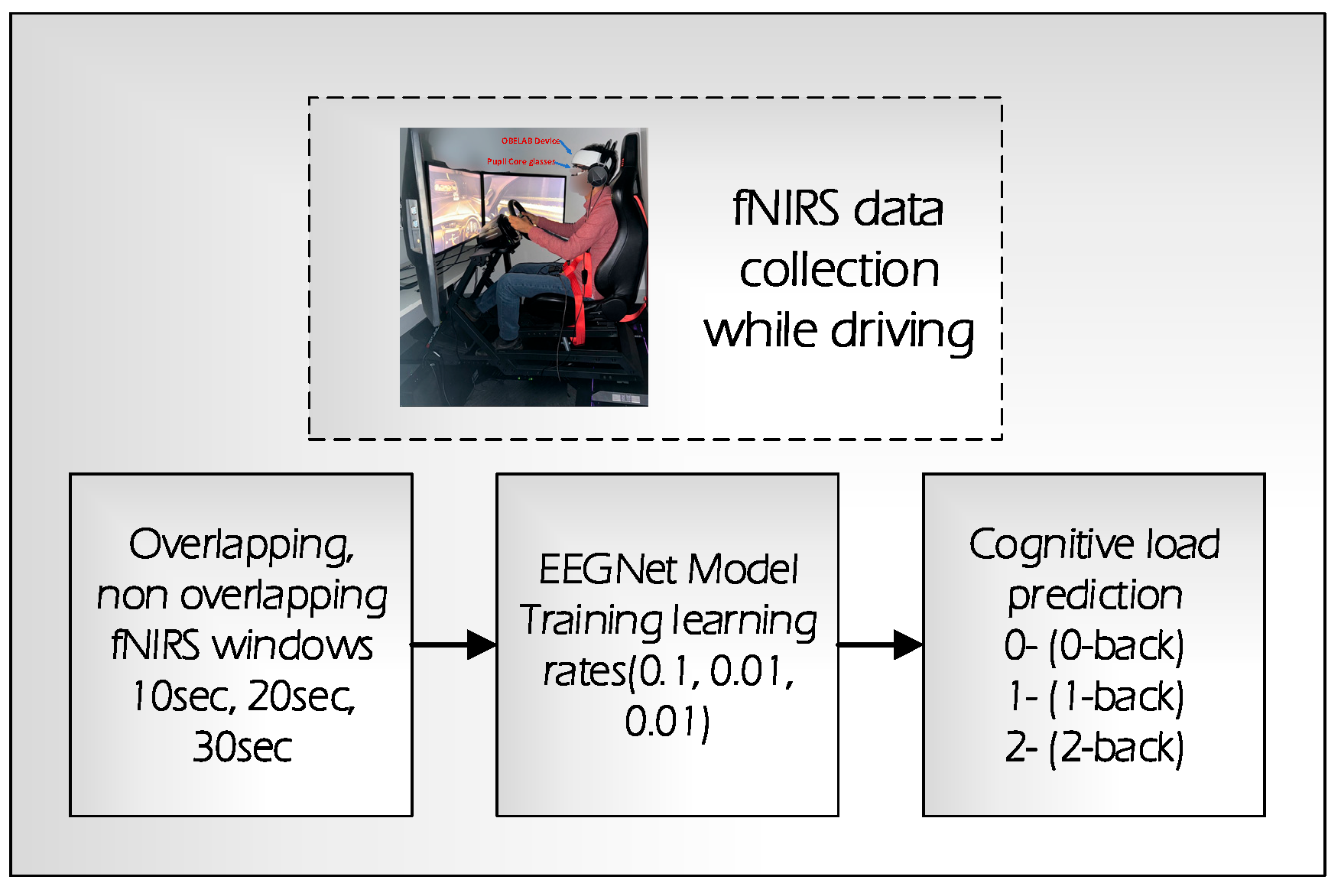

Following PCA, the selected hemodynamic features were segmented into temporal windows of 10, 20, and 30 seconds, using both overlapping and non-overlapping strategies. This segmentation step was designed to systematically assess the impact of varying temporal resolutions and windowing methods on classification performance. The segmented datasets were subsequently used as input to EEGNet, a lightweight convolutional neural network initially developed for EEG signal classification. For this study, EEGNet was adapted to analyze fNIRS-derived hemodynamic patterns, aiming to classify varying levels of cognitive workload. An overview of the full data processing and classification workflow including fNIRS signal acquisition, preprocessing, windowing methodology, and EEGNet-based classification is presented in

Figure 3.

EEGNet Model

To classify cognitive load across three distinct levels—namely, 0-back, 1-back, and 2-back from the fNIRS signals, this study utilized the EEGNet architecture, originally proposed by Lawhern et al. (2018) [

16]. The structure and configuration details of the EEGNet model employed in this study are summarized in

Table 1. The EEGNet model was selected due to its lightweight, compact design, which is particularly well-suited for learning from relatively small physiological datasets while effectively capturing spatiotemporal dependencies in neural signals. For optimization, the model was trained using the Adam optimizer, an adaptive learning rate method known for its robust convergence behavior. The EEGNet architecture is composed of three sequential convolutional blocks, each carefully designed to extract and integrate increasingly abstract spatial and temporal features from the fNIRS time-series data.

The model architecture begins with an input layer followed by two key convolutional operations. Initially, a 2D convolution is applied to capture low-level features across both the temporal and channel dimensions. This is followed by a depthwise convolution, where each channel is processed independently with its own filter. Unlike conventional convolutions, this method substantially reduces the number of trainable parameters while preserving the ability to learn meaningful spatial patterns. Batch normalization is applied after each convolution to standardize feature distributions and promote stable learning. The use of depthwise convolution notably enhances training efficiency and reduces the risk of overfitting, which is particularly important when working with smaller neuroimaging datasets.

Building on this, the next stage incorporates a separable convolution to independently model temporal and spatial information. A depthwise convolution first extracts temporal dynamics within each feature map, followed by a pointwise (1×1) convolution that fuses information across channels, capturing cross-channel dependencies. This two-step process not only reduces computational complexity but also ensures that the model effectively captures distributed brain activity patterns across time and space. By explicitly decoupling spatial and temporal processing, the model becomes more sensitive to subtle shifts in cognitive workload. Finally, the high-level features extracted through these operations are flattened into a one-dimensional vector, making them suitable for classification. This vector is passed through a dense layer projecting the features onto three output nodes, each representing a cognitive load level (0-back, 1-back, or 2-back). A SoftMax activation function generates a probability distribution across these classes, allowing the model to express its confidence in each prediction. The training process relies on the categorical cross-entropy loss function, which measures how well the predicted probabilities match the true labels.

Results and Discussions

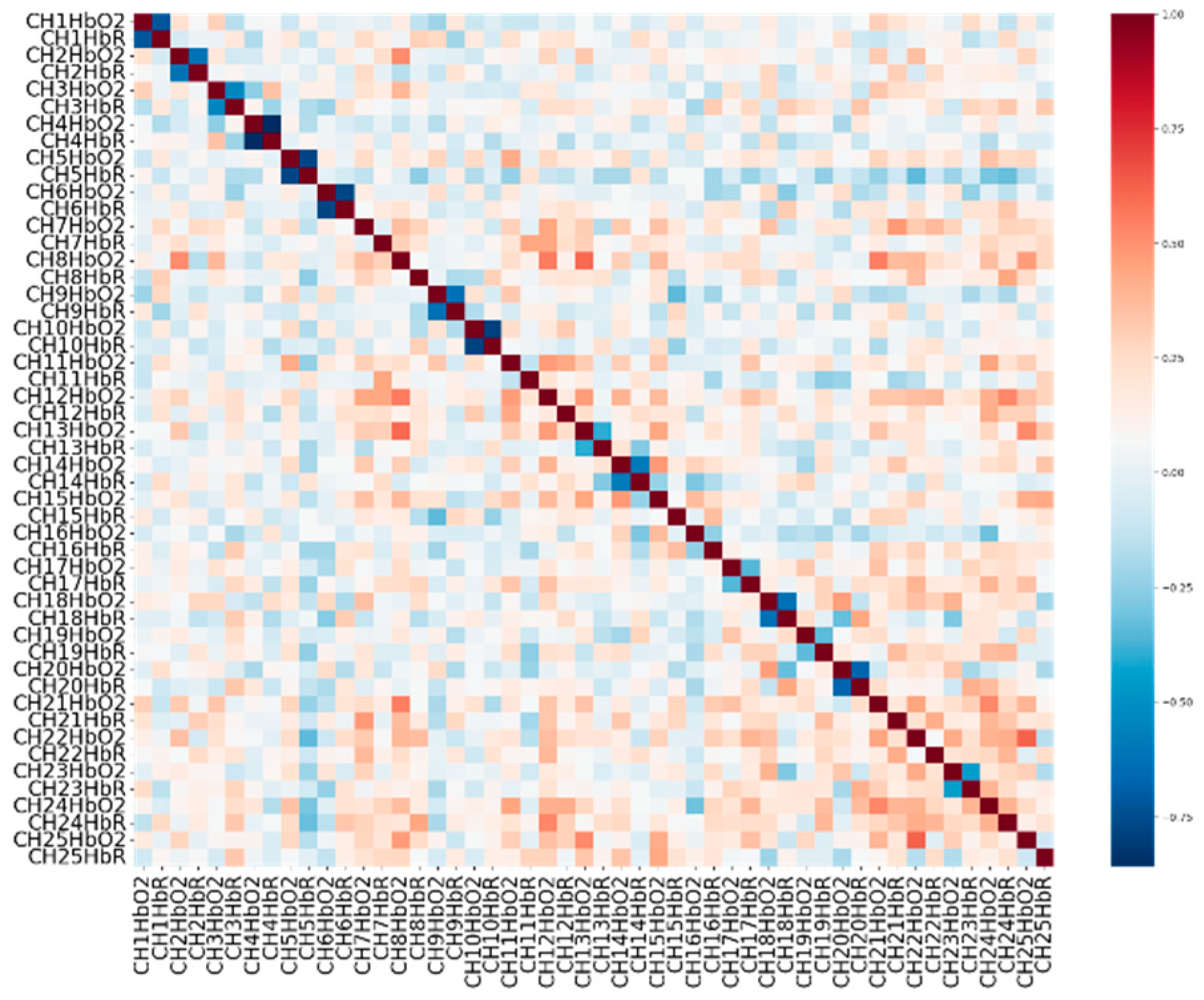

Given the high dimensionality of the dataset, which contains signals from 204 fNIRS channels, a feature selection step was essential to reduce computational complexity and isolate the most informative signals associated with cognitive load during simulated driving. PCA was employed to select the top 50 features that retained the highest variance, thereby preserving the most critical information relevant to differentiating cognitive states.

Figure 4. illustrates the correlation matrix of these top 50 features. The matrix indicates a low level of inter-feature correlation, suggesting that the selected features are largely independent and thus contribute unique information to the predictive model. Notably, the selected features include an equal representation of HbO2 and HbR signals. This balanced distribution highlights the complementary roles of both chromophores in capturing hemodynamic responses related to varying levels of cognitive load.

Previous research has consistently shown that HbO2 signals demonstrate greater sensitivity to task-related neural activation, especially in regions such as the prefrontal cortex, which is heavily involved in executive functions and decision-making. This high sensitivity has led many studies to prioritize HbO2 signals when analyzing cognitive workload. However, our findings suggest a more balanced contribution from both HbO2 and HbR signals in predicting cognitive load during simulated driving. This indicates that while HbO₂ may be more prominent in some contexts, the inclusion of HbR provides complementary information that enhances the overall sensitivity and robustness of cognitive state detection in dynamic, real-world-like environments.

To train and evaluate the EEGNet model, we employed a k-fold cross-validation approach, specifically using a 5-fold cross-validation strategy, to ensure robust and generalizable performance across different subsets of the data. For model optimization, we employed the Adam optimizer due to its adaptive learning capabilities and proven effectiveness in training deep neural networks. To investigate the impact of learning rate on model convergence and classification accuracy, we experimented with three different learning rates: 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001. The model was trained for 200 epochs using a batch size of 64, providing a sufficient number of iterations for learning while maintaining computational efficiency.

To further explore the temporal sensitivity of cognitive load classification, we segmented the fNIRS time-series data into both overlapping and non-overlapping windows of 10 seconds, 20 seconds, and 30 seconds. This segmentation allowed us to evaluate how different temporal resolutions affect the model’s ability to detect cognitive states. The classification results for overlapping window segmentation are summarized in

Table 2., whereas the outcomes for non-overlapping segmentation are reported in

Table 3.

The evaluation results using overlapping window segments demonstrate that a 30-second window, paired with a learning rate of 0.001, produces the best classification performance achieving a perfect accuracy of 100%. This finding suggests that longer, overlapping temporal segments enable the EEGNet model to more effectively capture stable and nuanced patterns of hemodynamic activity linked to varying levels of cognitive workload in fNIRS signals. The overlapping strategy ensures continuity across samples, allowing the model to learn from richer and more contextually informed representations of neural dynamics.

In contrast, the non-overlapping window segmentation reveals a different trend. The highest accuracy achieved in this setting is 97.22%, also with a learning rate of 0.001, but notably with a much shorter window length of 10 seconds. This indicates that in the absence of overlapping segments which inherently provide more data redundancy and temporal context shorter windows may help preserve temporal specificity and prevent dilution of task-related signals. Interestingly, increasing the window size in the non-overlapping configuration does not lead to improved accuracy and, in fact, results in a gradual decline in performance. This divergence highlights the critical role of segmentation strategy in shaping model sensitivity and suggests that the choice between overlapping and non-overlapping windows should be guided by both tasks demands and desired temporal resolution in cognitive state classification.

While the results of this study demonstrate the promise of using fNIRS and deep learning to classify cognitive load in a simulated driving environment, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the participant pool was relatively small, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Second, although the driving simulator offered a safe and controlled environment for data collection, it cannot fully replicate the dynamic and unpredictable nature of real-world driving scenarios. Additionally, the cognitive load was induced through structured n-back tasks, which, while effective for experimental control, may not reflect the full spectrum of mental demands encountered during naturalistic driving. Another limitation is the use of a single physiological modality (fNIRS); multimodal approaches could provide a more relistic assessment of driver states. Moreover, the black-box nature of deep learning models such as EEGNet presents challenges in interpretability, limiting insights into the neurophysiological underpinnings of model predictions.

Future work should focus on validating the findings in real-world driving settings using wearable fNIRS systems. Incorporating additional physiological signals like EEG, ECG, or eye-tracking could improve model robustness and allow for cross-modal verification of cognitive load. Expanding the participant pool to include more varied demographics would enhance the external validity of the model. There is also a need to develop explainable AI approaches to improve transparency and interpretability of model outputs. Finally, real-time implementation of such cognitive load monitoring systems in Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADAS) could help adapt vehicle behavior based on driver state, thereby enhancing safety and driving experience.

Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive approach to assessing cognitive workload during simulated driving using fNIRS and advanced deep learning techniques. By integrating a dual-task paradigm involving a realistic driving scenario with an auditory n-back task at three workload levels (0-back, 1-back, and 2-back), we successfully created a multi-modal experimental framework that reflects real-world multitasking demands encountered by drivers. Our findings demonstrate that fNIRS is a highly effective tool for monitoring cognitive states in dynamic environments, owing to its non-invasiveness, ease of use, and robustness against motion artifacts. Importantly, this study goes beyond prior work by employing three levels of cognitive load, thereby offering a deeper understanding of how workload fluctuates during complex task execution. We further employed the EEGNet deep learning model, adapted for fNIRS data, and evaluated its performance using both overlapping and non-overlapping segmentation windows an area rarely explored in current literature. Additionally, we incorporated a PCA-based feature selection method to reduce computational complexity and focus on the most informative signals from the fNIRS data. This technique proved effective in isolating relevant features and improving the model's ability to classify cognitive states. Our results revealed that a learning rate of 0.001 consistently yielded the best classification performance. Specifically, a 30-second overlapping window achieved 100% accuracy, while 10-second non-overlapping segments yielded 97% accuracy, indicating that segment length and segmentation strategy can influence performance, depending on the workload context.

This research demonstrates the potential of combining neuroimaging techniques and deep learning models to enable real-time and accurate detection of mental workload in naturalistic settings. The outcomes not only contribute to the growing body of literature on cognitive state monitoring but also hold practical implications for the development of adaptive driver-assistance systems and human-aware AI agents in mixed-initiative environments. Future work may focus on validating this framework in real-world driving conditions and expanding it to include multimodal physiological data fusion for even greater precision and generalizability.

References

- Lapierre, A.; Arbour, C.; Maheu-Cadotte, M.-A.; Vinette, B.; Fontaine, G.; Lavoie, P. Association between clinical simulation design features and novice healthcare professionals’ cognitive load: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Simul. Gaming 2022, 53, 538–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Chen, J.; Ding, X.; Zhang, D. Exploring cognitive load through neuropsychological features: an analysis using fNIRS-eye tracking. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2025, 63, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ücrak, F.; Izzetoglu, K.; Polat, M.D.; Gür, Ü.; Şahin, T.; Yöner, S.I.; İnan, N.G.; Aksoy, M.E.; Öztürk, C. The Impact of Minimally Invasive Surgical Modality and Task Complexity on Cognitive Workload: An fNIRS Study. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriaki, K.; Koukopoulos, D.; Fidas, C.A. A comprehensive survey of EEG preprocessing methods for cognitive load assessment. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 23466–23489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, M.; Kosa, M.; Chukoskie, L.; Moghaddam, M.; Harteveld, C. Exploring Eye Tracking to Detect Cognitive Load in Complex Virtual Reality Training. Proceedings of 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct); pp. 51–54.

- Khan, M.A.; Asadi, H.; Zhang, L.; Qazani, M.R.C.; Oladazimi, S.; Kiong, L.C.; Lim, C.P.; Nahavandi, S. Application of artificial intelligence in cognitive load analysis using functional near-infrared spectroscopy: A systematic review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 123717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Asadi, H.; Hoang, T.; Lim, C.P.; Nahavandi, S. Measuring Cognitive Load: Leveraging fNIRS and Machine Learning for Classification of Workload Levels. Proceedings of International Conference on Neural Information Processing; pp. 313–325.

- Benerradi, J. ; Marinescu, A.; Clos, J.; L. Wilson, M. Exploring machine learning approaches for classifying mental workload using fNIRS data from HCI tasks. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the Halfway to the Future Symposium 2019; Clos, J.

- Ho, T.K.K.; Gwak, J.; Park, C.M.; Song, J.-I. Discrimination of mental workload levels from multi-channel fNIRS using deep leaning-based approaches. Ieee Access 2019, 7, 24392–24403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Asadi, H.; Qazani, M.R.C.; Lim, C.P.; Nahavandi, S. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and Eye tracking for Cognitive Load classification in a Driving Simulator Using Deep Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.06349, arXiv:2408.06349 2024.

- Wang, J.; Grant, T.; Velipasalar, S.; Geng, B.; Hirshfield, L. Taking a Deeper Look at the Brain: Predicting Visual Perceptual and Working Memory Load From High-Density fNIRS Data. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 26, 2308–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastmond, C.; Subedi, A.; De, S.; Intes, X. Deep learning in fNIRS: a review. Neurophotonics 2022, 9, 041411–041411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez Rojas, R.; Joseph, C.; Bargshady, G.; Ou, K.-L. Empirical comparison of deep learning models for fNIRS pain decoding. Front Neuroinform 2024, 18, 1320189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peirce, J.; Gray, J.R.; Simpson, S.; MacAskill, M.; Höchenberger, R.; Sogo, H.; Kastman, E.; Lindeløv, J.K. PsychoPy2: Experiments in behavior made easy. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, W.B.; Parthasarathy, A.B.; Busch, D.R.; Mesquita, R.C.; Greenberg, J.H.; Yodh, A. Modified Beer-Lambert law for blood flow. Biomed. Opt. Express 2014, 5, 4053–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 15, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).