Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Methology

2.2. Reagents

2.3. Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Pretreatment of CPH and HMC-CPH

2.4. Acquisition of 1H NMR Spectra

2.5. Response Surface Analysis, Box Behnken Design

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. 1H NMR Spectra Elucidation

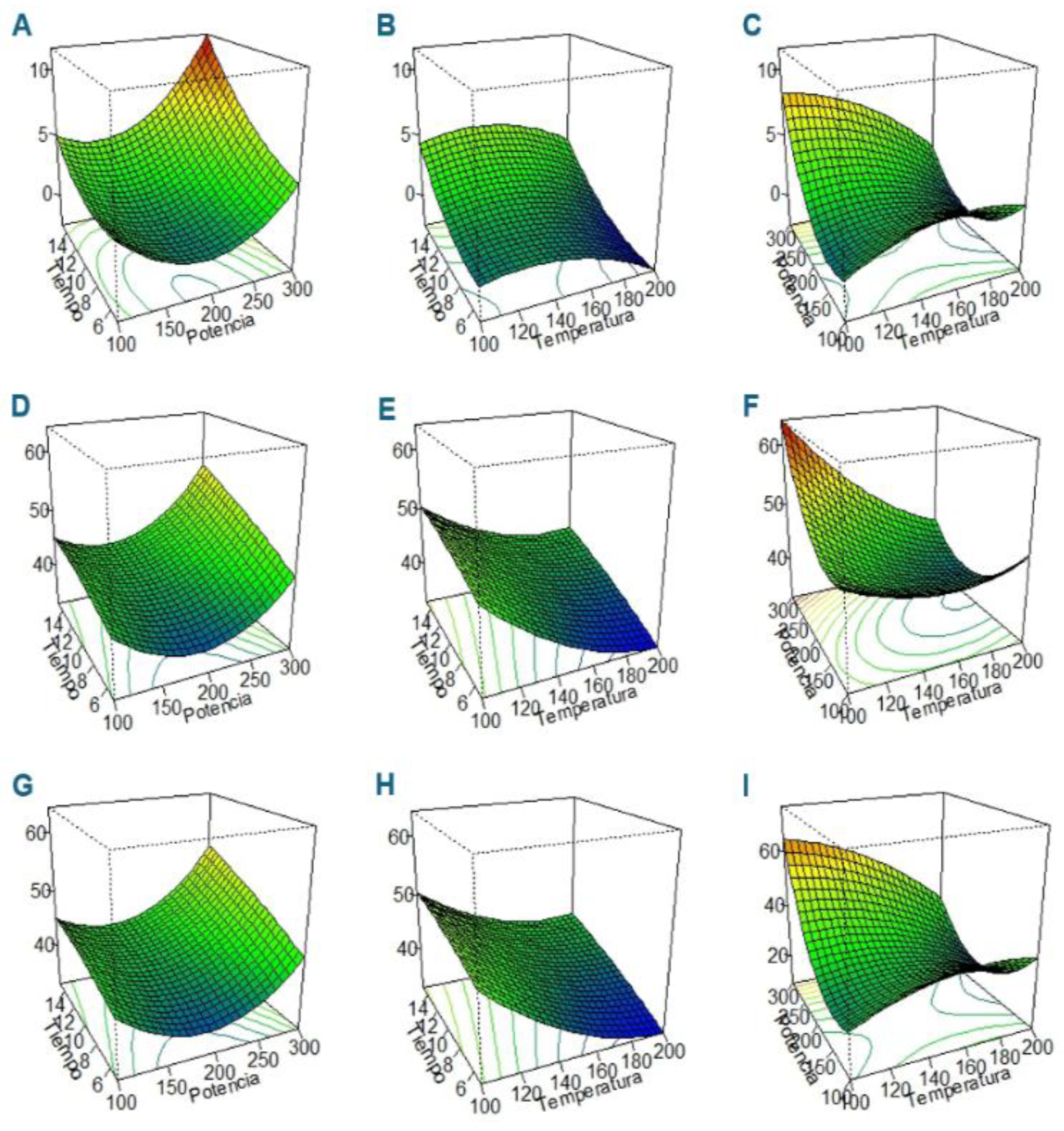

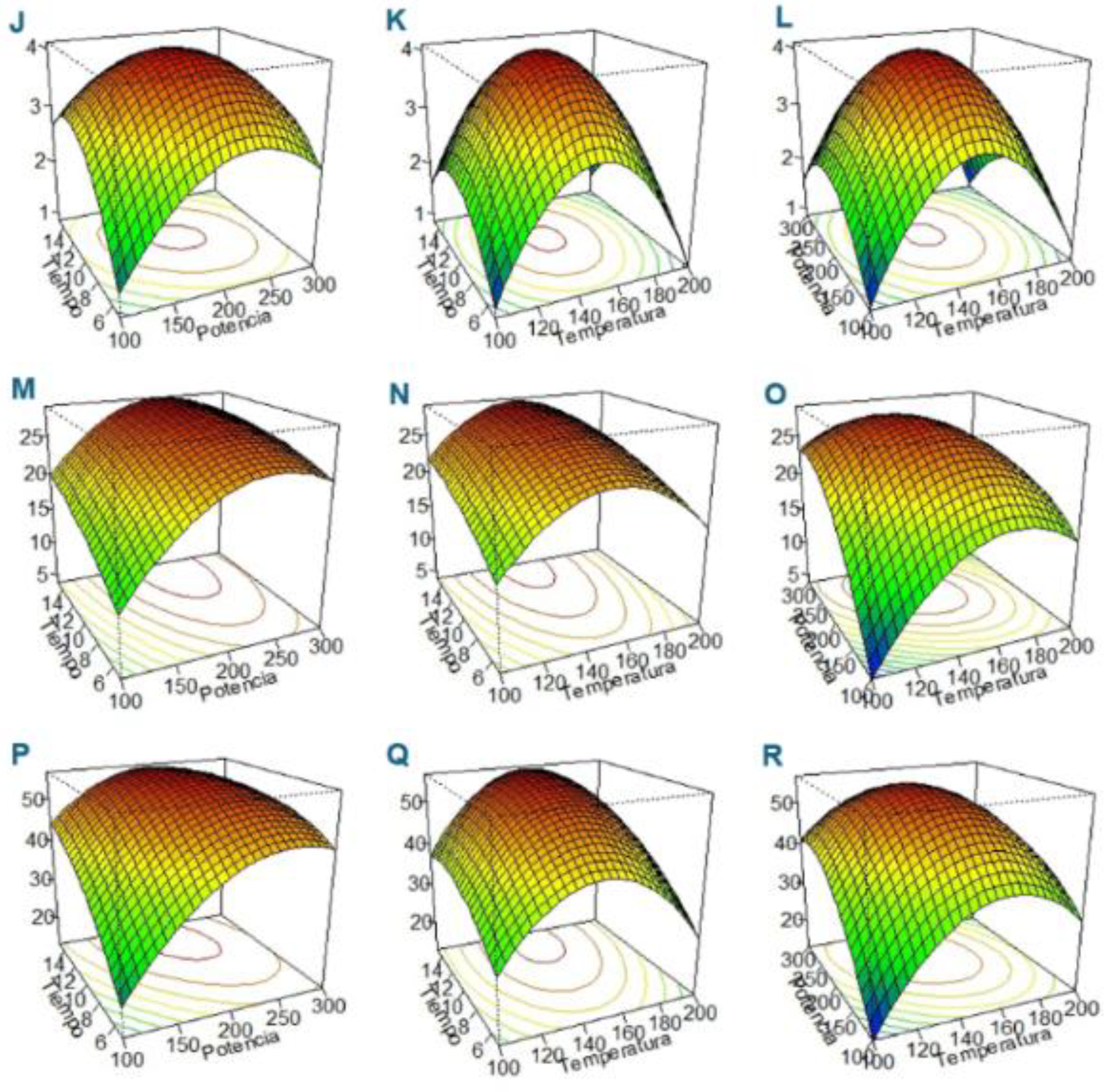

3.2. Optimization of CPH and HMC-CPH MA-HTP Conditions Through RSA-BBD

3.3. RSA—BBD ANOVA

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPH | Cocoa pod husk |

| MA-HTP | microwave-assisted hydrothermal pretreatment |

| HMC-CPH | hemicellulose Cocoa pod husk |

| RSA | Response surface analysis |

| BBD | Box Behnken design |

| 1H NMR Qu | proton nuclear magnetic resonance identification and quantification |

| 1H NMR | proton nuclear magnetic resonance |

| µM | Micro molar |

| NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| pH | Hydrogen potential |

References

- Ramos-Escudero, F.; Casimiro-Gonzales, S.; Cádiz-Gurrea, M. de la L.; Cancino Chávez, K.; Basilio-Atencio, J.; Ordoñez, E. S.; Muñoz, A. M.; Segura-Carretero, A. Optimizing Vacuum Drying Process of Polyphenols, Flavanols and DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay in Pod Husk and Bean Shell Cocoa. Scientific Reports 2023 13:1 2023, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrín-Chacón, J. P.; Núñez-Pérez, J.; Espín-Valladares, R. del C.; Manosalvas-Quiroz, L. A.; Rodríguez-Cabrera, H. M.; Pais-Chanfrau, J. M. Pectin Extraction from Residues of the Cocoa Fruit (Theobroma Cacao L.) by Different Organic Acids: A Comparative Study. Foods 2023, Vol. 12, Page 590 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Rodriguez-Garcia, J.; Van Damme, I.; Westwood, N. J.; Shaw, L.; Robinson, J. S.; Warren, G.; Chatzifragkou, A.; McQueen Mason, S.; Gomez, L.; Faas, L.; Balcombe, K.; Srinivasan, C.; Picchioni, F.; Hadley, P.; Charalampopoulos, D. Valorisation Strategies for Cocoa Pod Husk and Its Fractions. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem 2018, 14, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, Z. S.; de Carvalho Neto, D. P.; Pereira, G. V. M.; Vandenberghe, L. P. S.; de Oliveira, P. Z.; Tiburcio, P. B.; Rogez, H. L. G.; Góes Neto, A.; Soccol, C. R. Biotechnological Approaches for Cocoa Waste Management: A Review. Waste Management 2019, 90, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiceno-Suarez, A.; Cadena-Chamorro, E. M.; Ciro-Velásquez, H. J.; Arango-Tobón, J. C. By-Products of the Cocoa Agribusiness: High Valueadded Materials Based on Their Bromatological and Chemical Characterization. Rev Fac Nac Agron Medellin 2024, 77, 10585–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyangini, F.; Walde, S. G.; Chidambaram, R. Extraction Optimization of Pectin from Cocoa Pod Husks (Theobroma Cacao L.) with Ascorbic Acid Using Response Surface Methodology. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 202, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, T. F.; Oliveira, M. B. P. P. Cocoa By-Products: Characterization of Bioactive Compounds and Beneficial Health Effects. Molecules 2022, Vol. 27, Page 1625 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perwitasari, U.; Agustina, N. T.; Pangestu, R.; Amanah, S.; Saputra, H.; Andriani, A.; Fahrurrozi; Juanssilfero, A. B.; Thontowi, A.; Widyaningsih, T. D.; Eris, D. D.; Amaniyah, M.; Yopi; Habibi, M. S. Cacao Pod Husk for Citric Acid Production under Solid State Fermentation Using Response Surface Method. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2023, 13, 7165–7173.

- Muñoz-Almagro, N.; Valadez-Carmona, L.; Mendiola, J. A.; Ibáñez, E.; Villamiel, M. Structural Characterisation of Pectin Obtained from Cacao Pod Husk. Comparison of Conventional and Subcritical Water Extraction. Carbohydr Polym 2019, 217, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kley Valladares-Diestra, K.; Porto de Souza Vandenberghe, L.; Ricardo Soccol, C. A Biorefinery Approach for Pectin Extraction and Second-Generation Bioethanol Production from Cocoa Pod Husk. Bioresour Technol 2022, 346, 126635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoski, W.; Pereira, G. N.; Cesca, K.; de Oliveira, D.; de Andrade, C. J. An Overview on Pretreatments for the Production of Cassava Peels-Based Xyloligosaccharides: State of Art And Challenges. Waste Biomass Valorization 2023, 14, 2115–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Ren, M.; Zhou, C.; Kong, F.; Hua, C.; Fakayode, O. A.; Okonkwo, C. E.; Li, H.; Liang, J.; Wang, X. Total Utilization of Lignocellulosic Biomass with Xylooligosaccharides Production Priority: A Review. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 181, 107038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M. A. R.; Lee, S. H.; Mardawati, E.; Rahimah, S.; Antov, P.; Andoyo, R.; Kristak, L.; Nurhadi, B. Biomass Conversion and Sustainable Biorefinery. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muharja, M.; Fitria Darmayanti, R.; Palupi, B.; Rahmawati, I.; Arief Fachri, B.; Arie Setiawan, F.; Wika Amini, H.; Fitri Rizkiana, M.; Rahmawati, A.; Susanti, A.; Kharisma Yolanda Putri, D.; Muharja, M.; Darmayanti, R.; Palupi, B.; Rahmawati, I.; Fachri, B.; Setiawan, F.; Amini, H.; Rizkiana, M.; Rahmawati, A.; Susanti, A.; Putri, D. Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Alkali Pretreatment for Enhancement of Delignification Process of Cocoa Pod Husk. Bulletin of Chemical Reaction Engineering & Catalysis 2021, 16, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestu, R.; Amanah, S.; Juanssilfero, A. B.; Yopi; Perwitasari, U. Response Surface Methodology for Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Pectin from Cocoa Pod Husk (Theobroma Cacao) Mediated by Oxalic Acid. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2020, 14, 2126–2133. [CrossRef]

- Saelee, M.; Sivamaruthi, B. S.; Tansrisook, C.; Duangsri, S.; Chaiyasut, K.; Kesika, P.; Peerajan, S.; Chaiyasut, C. Response Surface Methodological Approach for Optimizing Theobroma Cacao L. Oil Extraction. Applied Sciences 2022, Vol. 12, Page 5482 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessey-Ramos, L.; Murillo-Arango, W.; Vasco-Correa, J.; Astudillo, I. C. P. Enzymatic Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Cocoa Pod Husks (Theobroma Cacao L.) Using Celluclast® 1. 5 L. Molecules 2021, Vol. 26, Page 1473 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S. L. C.; Bruns, R. E.; Ferreira, H. S.; Matos, G. D.; David, J. M.; Brandão, G. C.; da Silva, E. G. P.; Portugal, L. A.; dos Reis, P. S.; Souza, A. S.; dos Santos, W. N. L. Box-Behnken Design: An Alternative for the Optimization of Analytical Methods. Anal Chim Acta 2007, 597, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycan Dümenci, N.; Aydın Temel, F.; Turan, N. G. Role of Different Natural Materials in Reducing Nitrogen Loss during Industrial Sludge Composting: Modelling and Optimization. Bioresour Technol 2023, 385, 129464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassef, H. M.; Al-Hazmi, G. A. A. M.; Alayyafi, A. A. A.; El-Desouky, M. G.; El-Bindary, A. A. Synthesis and Characterization of New Composite Sponge Combining of Metal-Organic Framework and Chitosan for the Elimination of Pb(II), Cu(II) and Cd(II) Ions from Aqueous Solutions: Batch Adsorption and Optimization Using Box-Behnken Design. J Mol Liq 2024, 394, 123741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. H.; Yusoff, R.; Ngoh, G. C. Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Extraction Based on Absorbed Microwave Power and Energy. Chem Eng Sci 2014, 111, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, G.; Zuriarrain, J.; Zuriarrain, A.; Berregi, I. Quantitative Determination of Carboxylic Acids, Amino Acids, Carbohydrates, Ethanol and Hydroxymethylfurfural in Honey by 1H NMR. Food Chem 2016, 196, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharti, S. K.; Roy, R. Quantitative 1H NMR Spectroscopy. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2012, 35, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schievano, E.; Tonoli, M.; Rastrelli, F. NMR Quantification of Carbohydrates in Complex Mixtures. A Challenge on Honey. Anal Chem 2017, 89, 13405–13414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; She, D. Isolation, Structural Characterization, and Potential Applications of Hemicelluloses from Bamboo: A Review. Carbohydr Polym 2014, 112, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Bolio, G. I.; Fagundo-Mollineda, A.; Caamal-Fuentes, E. E.; Robledo, D.; Freile-Pelegrin, Y.; Hernández-Núñez, E. NMR Metabolic Profiling of Sargassum Species Under Different Stabilization/Extraction Processes. J Phycol 2021, 57, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Liang, X.; Du, L.; Su, F.; Su, W. Quantitative Determination and Validation of Avermectin B1a in Commercial Products Using Quantitative Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 2014, 52, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mekhlafi, N. A.; Mediani, A.; Ismail, N. H.; Abas, F.; Dymerski, T.; Lubinska-Szczygeł, M.; Vearasilp, S.; Gorinstein, S. Metabolomic and Antioxidant Properties of Different Varieties and Origins of Dragon Fruit. Microchemical Journal 2021, 160, 105687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, M.; Jamin, E.; Thomas, F.; Rebours, A.; Lees, M.; Rogers, K. M.; Rutledge, D. N. Fast and Global Authenticity Screening of Honey Using 1H-NMR Profiling. Food Chem 2015, 189, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, L. Y.; Kouassi, E. K. A.; Soro, D.; Yao, K. B.; Fanou, G. D.; Drogui, A. P.; Tyagi, D. R. Optimization of Thermochemical Hydrolysis of Potassium Hydroxide-Delignified Cocoa (Theobroma Cacao L) Pod Husks under Low Combined Severity Factors (CSF) Conditions. Sci Afr 2023, 22, e01908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| D-Fructose, Sucrose, and D-Glucose Standards | CPH and HMC-CPH MA-HTP Extracts | ||||

| Assignment | Chemical shifts used for identity check | Chemical shift | |||

| δ (ppm) | Multiplicity |

Identity check δ (ppm) |

Quantity δ (ppm) |

Multiplicity | |

| Fructose | 4.11 | d | 4.11 | d | |

| Fructose | 4.01 | t | 4.01 | t | |

| Fructose | 3.89 | dd | 3.90 | m | |

| Sucrose | 5.40 | d | 5.40 | d | |

| Sucrose | 4.21 | d | 4.20 | d | |

| Sucrose | 4.05 | t | 4.05 | t | |

| Sucrose | 3.76 | t | 3.76 | t | |

| Sucrose | 3.67 | s | 3.67 | s | |

| Sucrose | 3.55 | dd | n/d | n/d | |

| Sucrose | 3.47 | t | 3.47 | t | |

| Glucose | 5.24 | d | 5.24 | d | |

| Glucose | 4.65 | d | 4.65 | d | |

| Glucose | 3.89 | dd | n/d | n/d | |

| Glucose | 3.53 | dd | 3.53 | dd | |

| Glucose | 3.25 | t | 3.25 | t | |

| Independent variables | Dependent variable Y | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coded -1,0,1 [Uncoded] | Concentration CPH |

Concentration HMC-CPH |

||||||

| A (°C) |

B (W) |

C (min) |

Glucose (%) | Sucrose (%) | Fructose (%) | Glucose (%) | Sucrose (%) | Fructose (%) |

| -1 [100] | -1 [100] | 0 [10] | 1.0 | 51.10 | 29.90 | 1.2 | 7.70 | 16.91 |

| 1 [200] | -1 [100] | 0 [10] | 1.0 | 43.17 | 27.80 | 0.4 | 12.00 | 25.16 |

| -1 [100] | 1 [300] | 0 [10] | 9.4 | 68.02 | 70.26 | 2.2 | 26.23 | 44.78 |

| 1 [200] | 1 [300] | 0 [10] | 1.0 | 39.20 | 27.07 | 0.6 | 8.67 | 23.87 |

| -1 [100] | 0 [200] | -1 [5] | 1.2 | 50.39 | 29.56 | 0.5 | 8.15 | 20.20 |

| 1 [200] | 0 [200] | -1 [5] | 0.8 | 43.38 | 26.87 | 1.3 | 17.19 | 27.49 |

| -1 [100] | 0 [200] | 1 [15] | 0.7 | 39.41 | 23.51 | 1.1 | 20.90 | 35.43 |

| 1 [200] | 0 [200] | 1 [15] | 1.1 | 37.91 | 28.08 | 1.7 | 26.92 | 49.61 |

| 0 [150] | -1 [100] | -1 [5] | 0.5 | 34.63 | 20.94 | 1.4 | 13.98 | 21.58 |

| 0 [150] | 1 [300] | -1 [5] | 1.1 | 36.78 | 29.23 | 2.3 | 25.76 | 47.07 |

| 0 [150] | -1 [100] | 1 [15] | 7.5 | 52.79 | 57.48 | 2.8 | 16.42 | 41.23 |

| 0 [150] | 1 [300] | 1 [15] | 14.0 | 61.78 | 88.57 | 1.8 | 22.96 | 44.31 |

| 0 [150] | 0 [200] | 0 [10] | 1.0 | 42.15 | 27.91 | 7.8 | 35.80 | 75.56 |

| 0 [150] | 0 [200] | 0 [10] | 0.8 | 35.13 | 23.10 | 2.3 | 28.57 | 51.86 |

| 0 [150] | 0 [200] | 0 [10] | 1.4 | 43.38 | 31.83 | 2.1 | 17.45 | 34.10 |

| Source | Carbohydrate | Threshold (0.01) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) |

Power (Watt) |

Time (min) |

||

| CPH | Glucose | 135.4 | 180.6 | 5.8 |

| CPH | Sacarose | 154.3 | 256.3 | 20.2 |

| CPH | Fructose | 129.5 | 173.8 | 5.2 |

| HMC-CPH | Glucose | 142.2 | 204.4 | 10.5 |

| HMC-CPH | Sacarose | 148.8 | 215.6 | 14.3 |

| HMC-CPH | Fructose | 151.6 | 231.6 | 13.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).