Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

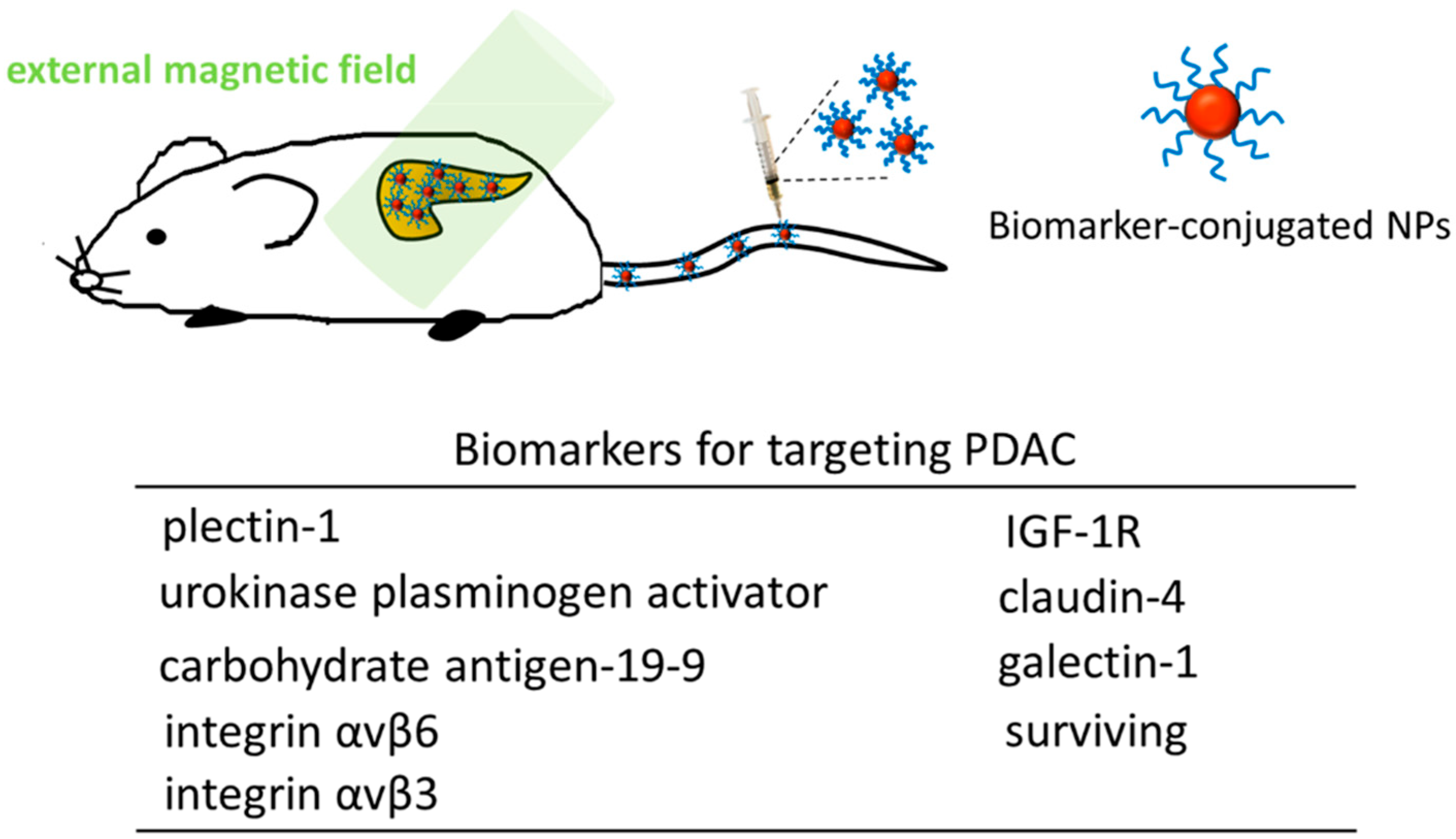

2. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (NPs) as Theranostic Agents for MR Imaging (MRI) and Pancreatic Ductal Carcinoma (PDAC) Treatment

3. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casolino, R., Braconi, C., Malleo, G., Paiella, S., Bassi, C., Milella, M., Dreyer, S.B., Froeling, F.E.M., Chang, D.K., Biankin, A.V., Golan, T. Reshaping preoperative treatment of pancreatic cancer in the era of precision medicine. Annals of Oncology. 2021, 32(2), 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D.P., Hong, T.S., Bardeesy, N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 371(11), 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, C.J., Cameron, J.L., Maher, M.M., Sauter, P.K., Zahurak, M.L. et al. A prospective randomized trial of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreatic ojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995, 222, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, A.; et al. Checkpoint inhibitors in pancreatic cancer. CancerTreat Rev. 2019, 78, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Xu, R., Wang, C., Qiu, J., Ren, B., You, L. Early screening and diagnosis strategies of pancreatic cancer: a comprehensive review. Cancer Communications. 2021, 41, 1249–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R., Zeisberg, M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006, 6, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrebaeck, C.A. Precision diagnostics: moving towards protein biomarker signatures of clinical utility in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017, 17, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R.F., Moore, T., Arumugam, T., Ramachandran, V., Amos, K.D., Rivera, A. et al. Cancer-Associated Stromal Fibroblasts Promote Pancreatic Tumor Progression. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., Qian, W., Uckun, F.M., Wang, L., Wang, Y.A., Chen, H., Kooby, D., Yu, Q., Lipowska, M., Staley, C.A., et al. IGF1 Receptor Targeted Theranostic Nanoparticles for Targeted and Image-Guided Therapy of Pancreatic Cancer. ACS Nano. 2015, 9, 7976–7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Lu, N., Zhou, Y., Xuan, S., Zhang, J., Giampieri, F. et al. Targeting pancreatic cancer cells with peptide-functionalized polymeric magnetic nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S., Song, L., Tian, Y., Zhu, L., Guo, K., Zhang, H. et al. Emodin-Conjugated PEGylation of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for FI/MRI Dual-Modal Imaging and Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021, 16, 7463–7478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

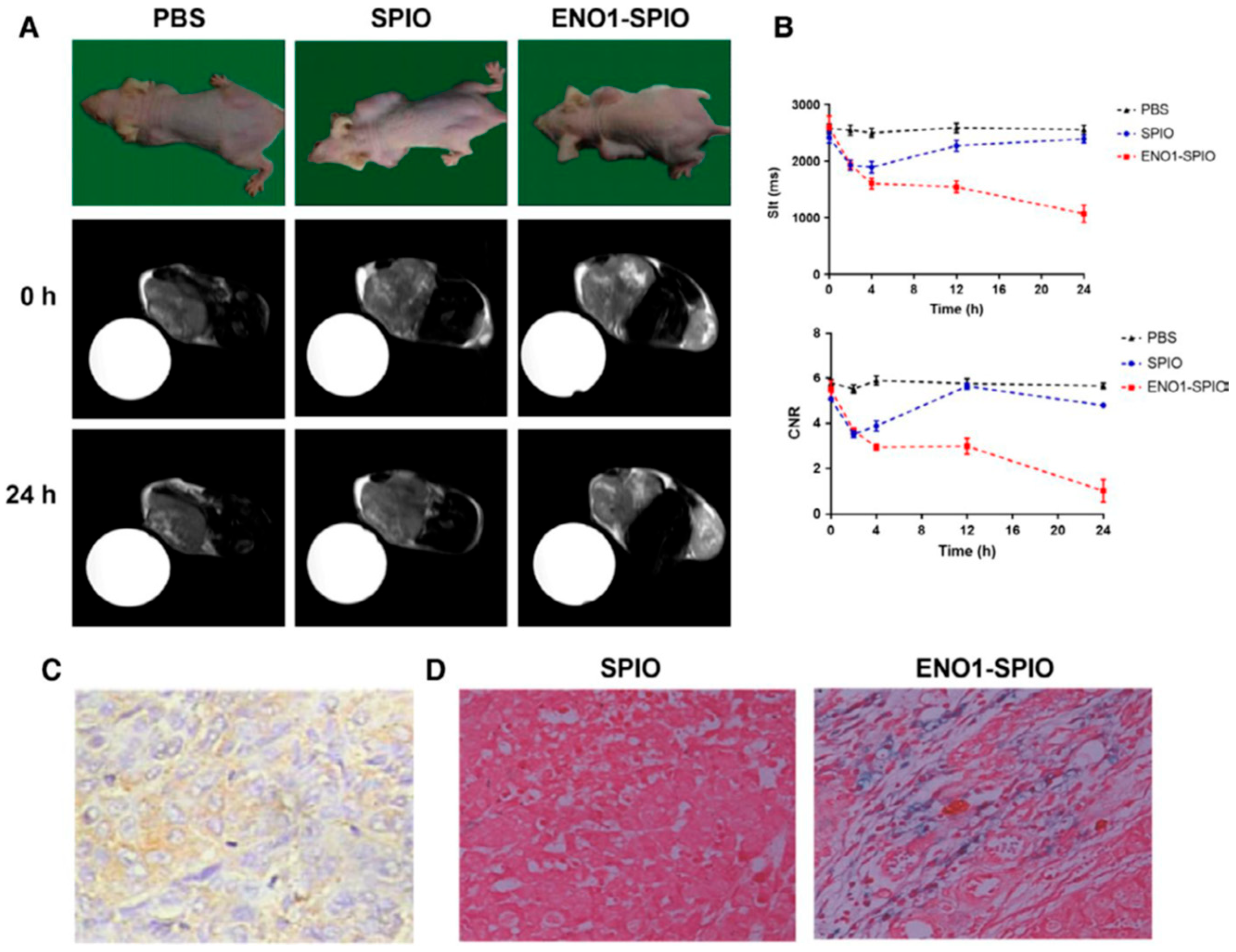

- Wang, L., Yin, H., Bi, R., Gao, G., Li, K., Liu, H.L. ENO1-targeted superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for detecting pancreatic cancer by magnetic resonance imaging. J Cell Mol Med. 2020, 24(10), 5751–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Zhou, H., Li, X., Duan, N., Hu, S., Liu, Y. et al. Plectin-1 targeted dual-modality nanoparticles for pancreatic cancer imaging. EBioMedicine 2018, 30, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affram, K., Smith, T., Helsper, S., Rosenberg, J.T., Han, B., Trevino, J. et al. Comparative study on contrast enhancement of Magnevist and Magnevist-loaded nanoparticles in pancreatic cancer PDX model monitored by MRI. Cancer Nanotechnology. 2020, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Jiang, Z., Chen, L., Pan, C., Sun, S., Liu, C., et al. PCN-Fe (III)-PTX nanoparticles for MRI guided high efficiency chemo-photodynamic therapy in pancreatic cancer through alleviating tumor hypoxia. Nano Res. 2020, 13, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S., Forge, D., Port, M., Roch, A., Robic, C., Vander Elst, L. et al. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2064–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A., Medarova, Z., Potthast, A., Dai, G. In Vivo Targeting of Underglycosylated MUC-1 Tumor Antigen Using a Multimodal Imaging Probe. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 1821–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, M., Taylor, A., Murray, P., Rosseinsky, M.J., Adams, D. J. Design considerations for the synthesis of polymer coated iron oxide nanoparticles for stem cell labelling and tracking using MRI. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6733–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zahaby, S.A., Elnaggar, Y.S.R., Abdallah, O.Y. Reviewing two decades of nanomedicine implementations in targeted treatment and diagnosis of pancreatic cancer: An emphasis on state of art. J. Control. Release. 2019, 293, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature: the key role of tumor-selective macromolecular drug targeting. Adv. Enzym. Regul. 2001, 41, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.Y., Kano, M.R. Stromal barriers to nanomedicine penetration in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 2085–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiseshaiah, P.P., Crist, R.M., Hook, S.S., McNeil, S.E. Nanomedicine strategies to overcome the pathophysiological barriers of pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 750–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H., Nel, A.E. Use of nano engineered approaches to overcome the stromal barrier in pancreatic cancer. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 130, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, P.P., Cuevas, C., Chang, A.E., Goel, V.K., Von Hoff, D.D., Hingorani, S.R. Enzymatic Targeting of the Stroma Ablates Physical Barriers to Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012, 21, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hoff, D.D., Ervin T., Arena, F.P., Chiorean, E.G., Infante, J., Moore, M., Seay, T., Tjulandin, S.A., Ma, W.W., Saleh, M.N., Harris, M., Reni, M., Dowden, S., Laheru. D., Bahary, N., Ramanathan, R.K., Tabernero, J., Hidalgo, M., Goldstein, D., Van Cutsem, E., Wei, X., Iglesias, J., Renschler, M.F. Increased Survival in Pancreatic Cancer with nab-Paclitaxel plus Gemcitabine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013, 369, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Gillam, A., Hubner, R.A., Siveke, J.T., Von Hoff, D.D., Belanger, B., de Jong F.A. NAPOLI-1 phase 3 study of liposomal irinotecan in metastatic pancreatic cancer: final overall survival analysis and characteristics of long-term survivors. Eur. J. Cancer. 2019, 108, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, W., Carey, E. T., Choi, M. Spotlight on liposomal irinotecan for metastatic pancreatic cancer: patient selection and perspectives. Oncol. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Dijke, P, Arthur, H.M. Extracellular control of TGF[beta] signalling in vascular development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, M.R., Bae, Y., Iwata, C., Morishita, Y., Yashiro, M., Oka, M., Fujii, T., Komuro, A., Kiyono, K., Kaminishi, M., Hirakawa, K., Ouchi, Y., Nishiyama, N., Kataoka, K., Miyazono, K. Improvement of cancer-targeting therapy, using nanocarriers for intractable solid tumors by inhibition of TGF-β signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007, 104, 3460–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugahara, K.N., Teesalu, T., Karmali, P.P., Kotamraju, V.R., Agemy, L., Greenwald, D.R., Ruoslahti, E. Coadministration of a Tumor-Penetrating Peptide Enhances the Efficacy of Cancer Drugs. Science 2010, 328, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvreur, P., Reddy, L.H., Mangenot, S., Poupaert, J.H., Desmaële, D., Lepêtre-Mouelhi, S. Discovery of new hexagonal supramolecular nanostructures formed by squalenoylation of an anticancer nucleoside analogue. Small 2008, 4, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Li, Y., Wang, M., Liu, K., Hoover, A.R., Li, M., Towner, R.A., Mukherjee, P., Zhou, F., Qu, J. et al. Synergistic interventional photothermal therapy and immunotherapy using an iron oxide nanoplatform for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Acta Biomater. 2022, 138, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvanou, E.A., Kolokithas-Ntoukas, A., Liolios, C., Xanthopoulos, S., Paravatou-Petsotas, M., Tsoukalas, C., Avgoustakis, K., Bouziotis, P. Preliminary Evaluation of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Radiolabeled with 68Ga and 177Lu as Potential Theranostic Agents. Nanomaterials. 2022, 12, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.M., Jung, M.H., Lee, J.S., Lee, J.S., Lim, I.C., Im, H., Kim, S.W., Kang, S.A., Cho, W.J., Park, J.K. Chelator-Free Copper-64-Incorporated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for PET/MR Imaging: Improved Radiocopper Stability and Cell Viability. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.A., Bardeesy, N., Anbazhagan, R., Gurumurthy, S., Berger, J., Alencar, H. et al. Targeted Nanoparticles for Imaging Incipient Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. PLoS Med. 2008, 15, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.L., Zeglis, B.M., Abdel-Atti, D., Aggeler, R., Sawada, R., Agnew, B.J. et al. Site-specifically labeled CA19.9-targeted immunoconjugates for the PET, NIRF, and multimodal PET/NIRF imaging of pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 15850–15855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., Mao, H., Cao, Z., Wang, Y.A., Peng, X., Wang, X., et al. Molecular imaging of pancreatic cancer in an animal model using targeted multifunctional nanoparticles. Gastroenterology. 2009, 136, 1514–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neesse, A., Hahnenkamp, A., Griesmann, H., Buchholz, M., Hahn, S.A., Maghnouj, A. et al. Claudin-4-targeted optical imaging detects pancreatic cancer and its precursor lesions. Gut 2013, 62, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, C.G., Kamkaew, A., Im, H.J., Valdovinos, H.F., Sun, H., Hernandez, R. et al. ImmunoPET imaging of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in a subcutaneous mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 1958–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, I., Strauss, A., Dobiasch, S.,Weis, C., Szanyi, S., Gil-Iceta, L. et al. Targeted diagnostic magnetic nanoparticles for medical imaging of pancreatic cancer. J. Control. Release 2015, 214, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Liu, H., Ma, T., Sun, X., Shi, J., Jia, B. et al. Integrin alphavbeta(6)-targeted SPECT imaging for pancreatic cancer detection. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovic-Arsic, M., Mohajerani, P., Sarantopoulos, A., Kalideris, E., Steiger, K., Esposito, I. et al. Multimodal molecular imaging of integrin alphavbeta3 for in vivo detection of pancreatic cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M., Xiong, F., Shi, Y. In vitro study of SPIO-labeled human pancreatic cancer cell line BxPC-3. Contrast Media Mol. 2013, 8, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, D., Thomas, S., Mino-Kenudson, M., Fernández-del, C.C., Bauer, T.W., Williams, M. et al. Plectin-1 as a novel biomarker for pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Barahona, I., Muñoz-Hernando, M., Ruiz-Cabello, J., Herranz, F., Pellico, J. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: An Alternative for Positive Contrast in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Inorganics 2020, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wen, W.; Wang, X.; Huang, D.; Cao, J.; Qi, X.; Shen, S. Ultrasmall Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Cause Significant Toxicity by Specifically Inducing Acute Oxidative Stress to Multiple Organs. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2022, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, I.; Yehye, W.A.; Etxeberria, A.E.; Alhadi, A.A.; Dezfooli, S.M.; Julkapli, N.B.M.; Basirun, W.J.; Seyfoddin, A. Nanoantioxidants: Recent Trends in Antioxidant Delivery Applications. Antioxidants 2019, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesárošová, M.; Kozics, K.; Bábelová, A.; Regendová, E.; Pastorek, M.; Vnuková, D.; Buliaková, B.; Rázga, F.; Gábelová, A. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Genotoxicity of Surface-Modified Magnetite Nanoparticles. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 226, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montet, X., Weissleder, R., Josephson, L. Imaging pancreatic cancer with a peptide− nanoparticle conjugate targeted to normal pancreas. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006, 17, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J., Chen, S., Li, Y., Zeng, L., Lian, G., Li, J. et al. Nanoparticles modified by triple single chain antibodies for MRI examination and targeted therapy in pancreatic cancer. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Chen, H., Chen, J. Emodin sensitizes human pancreatic cancer cells to egfr inhibitor through suppressing stat3 signaling pathway. Cancer Manag Res. 2019, 11, 8463–8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H., Wang, L., Liu, H. L. ENO1 overexpression in pancreatic cancer patients and its clinical and diagnostic Significance. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018, 3842198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Zheng, B., Robbins, D.H., Lewin, D.N., Mikhitarian, K., Graham, A. et al. Accurate Discrimination of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Chronic Pancreatitis Using Multimarker Expression Data and Samples Obtained by Minimally Invasive Fine Needle Aspiration. Int. J. 2007, Cancer. 120, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.Y., Qian, W.P., Wang, L., Wang, Y.A., Staley, C.A., Satpathy, M. et al. Theranostic Nanoparticles with Controlled Release of Gemcitabine for Targeted Therapy and MRI of Pancreatic Cancer. ACS Nano. 2013, 7, 2078–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabulo, S., Aires, A., Aicher, A., Heeschen, C., Cortajarena, A. L. Multifunctionalized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Selective Targeting of Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of NPs | Size | Strategy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetofluorescent nanoparticles | ~39 nm | plectin-1 targeted peptides (PTP)-conjugated magnetofluorescent nanoparticles to detect PDAC | [11] |

| Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPION) | SPION: 9-15 nm; Plectin-SPION-Cy7: 29 nm |

plectin-1 antibody-conjugated SPION to detect pancreatic cancer | [14] |

| Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONP) | BN-CLIO: 35 nm | BN peptide-nanoparticle conjugate (BN-CLIO) to target normal pancreas for imaging PDAC | [50] |

| Ultra-small superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) | CKAAKN-USPIO: 96 nm | pancreatic cancer targeting peptide (CKAAKN)-functionalized USPIO to target pancreatic cancer cells | [11] |

| Iron oxide nanoparticles | IONPs-PEG-MCC triple scAbs: 24 nm | triple scAbs-conjugated IONPs to target pancreatic cancer | [51] |

| Fe3O4 nanoparticles | Fe3O4-PEG-Cy7-EMO: 27 nm | Fe3O4-PEG-Cy7-EMO to target pancreatic cancer | [12] |

| SPION | SPION: 5-10 nm; ENO1-targeted SPION: 30 nm |

ENO1-targeted SPION for detecting pancreatic cancer | [13] |

| SPIO | SPIO: 10 nm | uPAR-targeted SPIO to target pancreatic cancer | [38] |

| IONP | IONP: 10 nm; ATF-IONP-Gem: 66 nm | uPAR-targeted nanocomposites (ATF-IONP-Gem) to target pancreatic cancer | [7] |

| Fe(III) ions | PCN-Fe(III)-PTX NPs: 317 nm | PCN-Fe(III)-PTX NPs o target pancreatic cancer | [55] |

| IONP | anti-CD47 antibody-modified IONP: 107 nm | anti-CD47 antibody-modified IONP to target pancreatic cancer | [56] |

| IONP | IONP: 10 nm IGF-1-IONP: 17 nm |

human insulin-like growth factor1 (IGF1)-conjugated IONP to target pancreatic cancer | [10] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).