1. Introduction

1.1. GeoAI

Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI) represents a subfield of spatial data science and artificial intelligence (AI), focusing on methods, systems, and services that leverage geographic knowledge. Being an interdisciplinary field, it integrates machine learning, deep learning, and knowledge graph technologies with high-performance computing and big data mining, enhancing our understanding of geographic phenomena and human-environment interactions and helping solve geographic problems [

1,

2,

3]. Lately, there is a new perspective that GeoAI is more than mere application in the geosciences field. It not only provides AI to derive insights from geographic data but also provides the spatio-temporal perspective to AI, especially when knowledge, behavior and intelligence are concerned [

4]. In other words, it is not simply the application of AI to geospatial data, but rather the development of spatially explicit AI models that incorporate spatial thinking and reasoning [

5,

6]. These models consider unique geospatial characteristics, such as spatial autocorrelation, heterogeneity, and dependency, which are often overlooked in traditional AI approaches. GeoAI is gradually changing how topographic data is collected, processed, interpreted, and used [

7,

8]. National Mapping and Agencies (NMAs) are uniquely positioned to benefit from GeoAI to enhance efficiency, improve data quality, and respond more agilely to increasing pressure to deliver faster, smarter, and more cost-efficient services amid resource constraints, global societal and environmental challenges [

9]. At its core, GeoAI enables automation in feature detection [

3,

10], change intelligence [

11], 3D data processing [

12,

13,

14], and map generalization [

15,

16]. These are processes traditionally reliant on human interpretation and manual updates. Advancements in the above mentioned areas promise considerable gains in the speed, consistency, and scalability of map production [

17].

1.2. Global Trends in Topographic Mapping

Topographic mapping is evolving due to the convergence of technological advancements, user demands, and global pressures on government institutions. According to the future trends report published by the United Nations committee of experts on Global Geospatial Information Management, the next five to ten years will see five major driving forces shaping the geospatial information management landscape [

18] namely

Technological advancements: Innovations like machine learning, deep learning, and high-resolution imagery are transforming data collection, processing, and interpretation. Big data processing and digital infrastructure will further empower geospatial workflows that are pivotal in topographic mapping.

Digital Transformation and Real-Time Information: The push toward real-time data integration and digital platforms enables dynamic map updates and on-demand analytics, moving away from static datasets toward continuously refreshed information systems requiring mapping agencies to transform and rethink strategies.

Rise of New Data Sources and Analytical Methods: New opportunities for data gathering, like drones and sensors enrich the topographic mapping process. The proliferation of data cubes and integration platforms enhances analytical depth and interoperability.

Legislative Pressures and Governance Needs: Increasing emphasis on digital ethics, privacy, and responsible AI frameworks guides how GeoAI can be safely implemented. Pressures on public institutions to be transparent and efficient will add urgency to AI governance.

Changing User Expectations: There is a growing demand for user-centric services, personalized and interactive visualizations, and responsive infrastructure. This shift requires agencies to rethink map production and delivery as a two-way engagement rather than one-way provision.

1.3. Topographic Mapping at the Dutch Kadaster

Topographic mapping involves data collection on the elevation, shape, and features of the land, as well as documenting the locations of natural and man-made objects such as mountains, rivers, roads, and buildings. Cartography, the art of map making, focuses on designing, creating, and interpreting both analog and digital maps to visually and comprehensibly represent topographical and geographical information. At Kadaster, key register topography (BRT) is produced annually. It is a collection of topographic maps produced at different scales , the most important being the TOP10NL, which is produced at a 1:10,000 scale [

19]. Rather than starting from scratch each year, essential changes are captured, and the maps are revised and updated based on these changes. The production process involves collecting new features or triggers for change detection, updating the map based on these triggers, followed by map design, which includes generalization and quality checks. Current workflows are producer-centric, but a paradigm shift is underway where users take center stage. There is a growing demand for real-time data, user-friendly data/map visualizations, and interactive products.

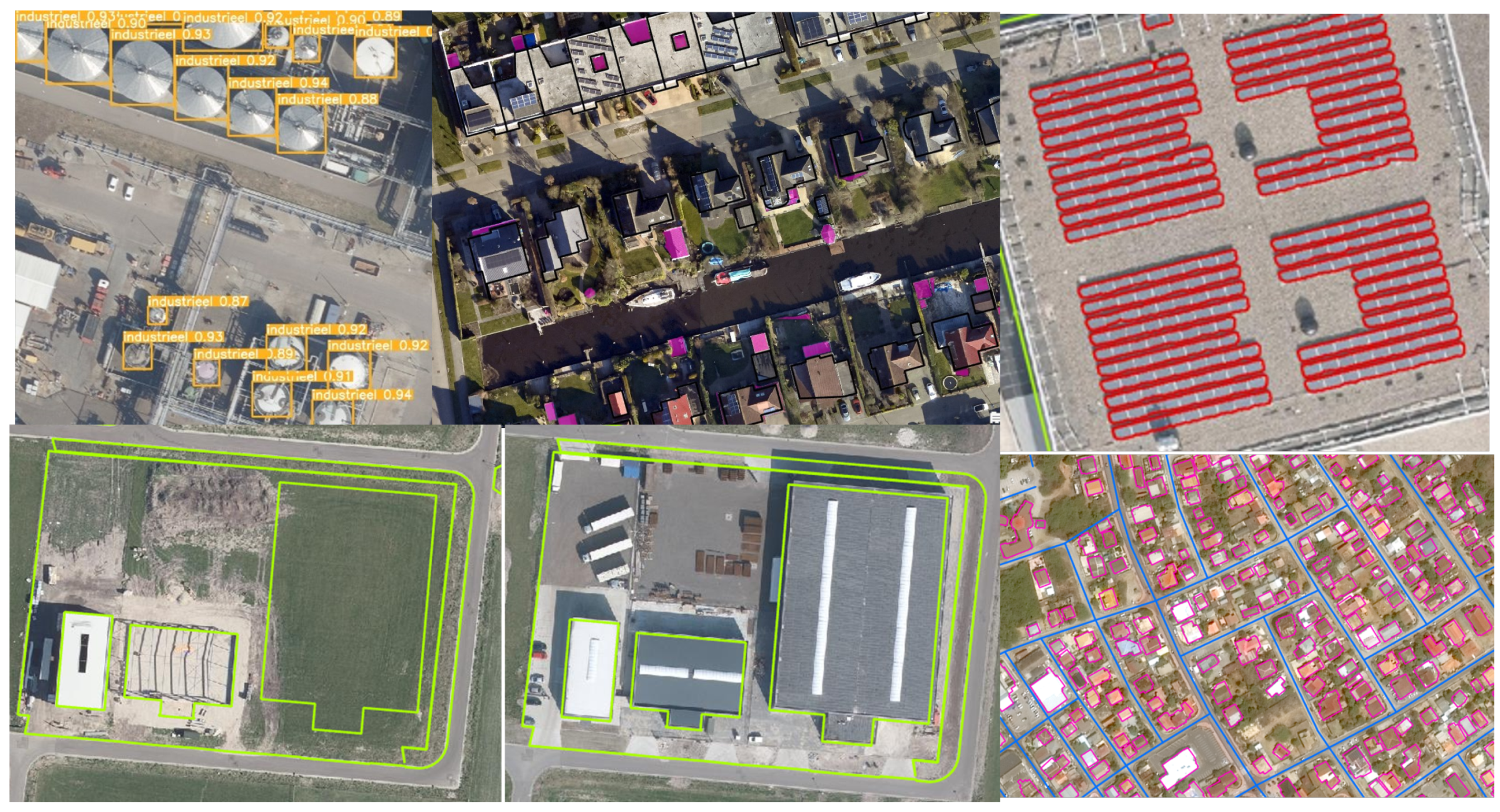

Within Kadaster, GeoAI applications are being developed and deployed not only for use in topographic mapping but also for supporting questions from different internal and external stakeholders. Use of object detection models for identifying storage tanks , solar panels [

20], forest trails, building and road detections for helping operators with data collection for the Multi-national Geospatial Co-production Program, detection of parking garages from streetview images, change detection and quality analysis of existing registers have been explored and a few are already in production (see

Figure 1). National Mapping Agencies (NMAs) within Europe also are actively piloting and operationalizing use cases such as automated roof and building detection, land cover classification, and road feature extraction using deep learning models trained on satellite imagery, LiDAR point clouds, and aerial data [

21]. However, adoption of AI within NMAs is not without challenges.

1.4. Charting the path: the future of topography

The increasing availability of geospatial data and the rise of AI technologies have given birth to GeoAI; a powerful intersection of spatial science and machine learning. In the context of topographic mapping, application of AI techniques is particularly of use in data collection, analysis and interpretation. With the advent of generative AI, large language-vision models are also being employed for data collection and interpretation purposes [

22,

23,

24]. For NMAs such as Kadaster, it is essential to understand not only the benefits but also the risks of implementing these technologies. Moreover, the use of this technology should be able to tackle the challenges created by global trends like fewer subject matter experts and the competetive labour market, austerity measures and legacy systems. In addition, GeoAI comes with its own challenges calling for significant upfront investments, the need for specialized expertise to manage and interpret complex models, legal issues, and the difficulties in operationalization of pilot projects. Furthermore, establishing the necessary infrastructure while ensuring compliance with policy, governance, and the unique responsibilities of NMAs remains a critical concern.

To understand, evaluate and provide solutions for a sustainable topographic map production and geoinformation at the Kadaster, a research agenda was created. One of the major topics within this research was GeoAI and the opportunities it offers to the future of topography [

25]. By examining global examples and trends and synthesizing insights from current applications and theoretical frameworks, this paper presents a multi-perspective analysis of the opportunities and risks associated with GeoAI in topographic domain, focusing on a short-term outlook of the next three to five years, and outlines strategic insights for investments and effective adoption.

2. Interdependencies in GeoAI Implementation

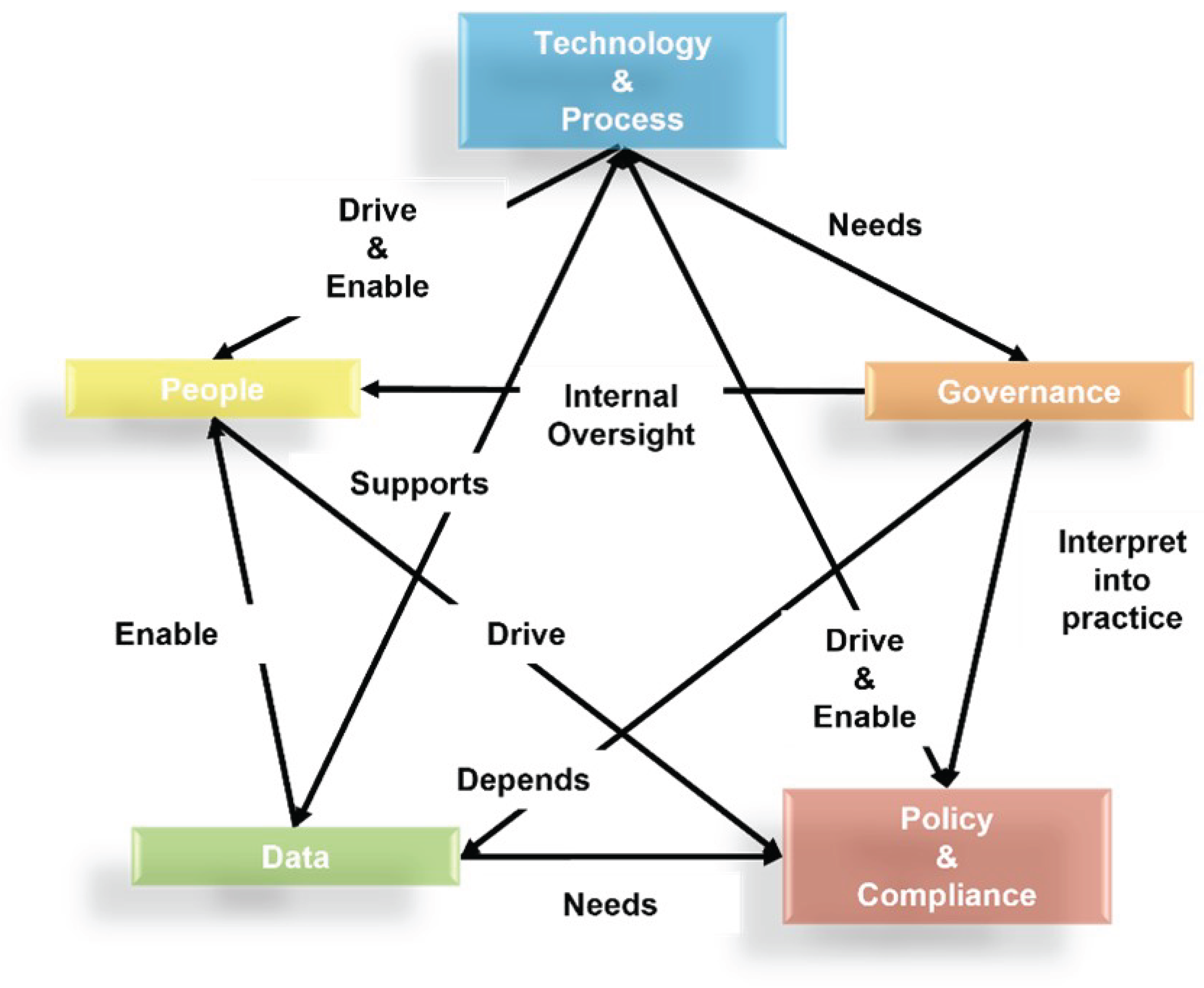

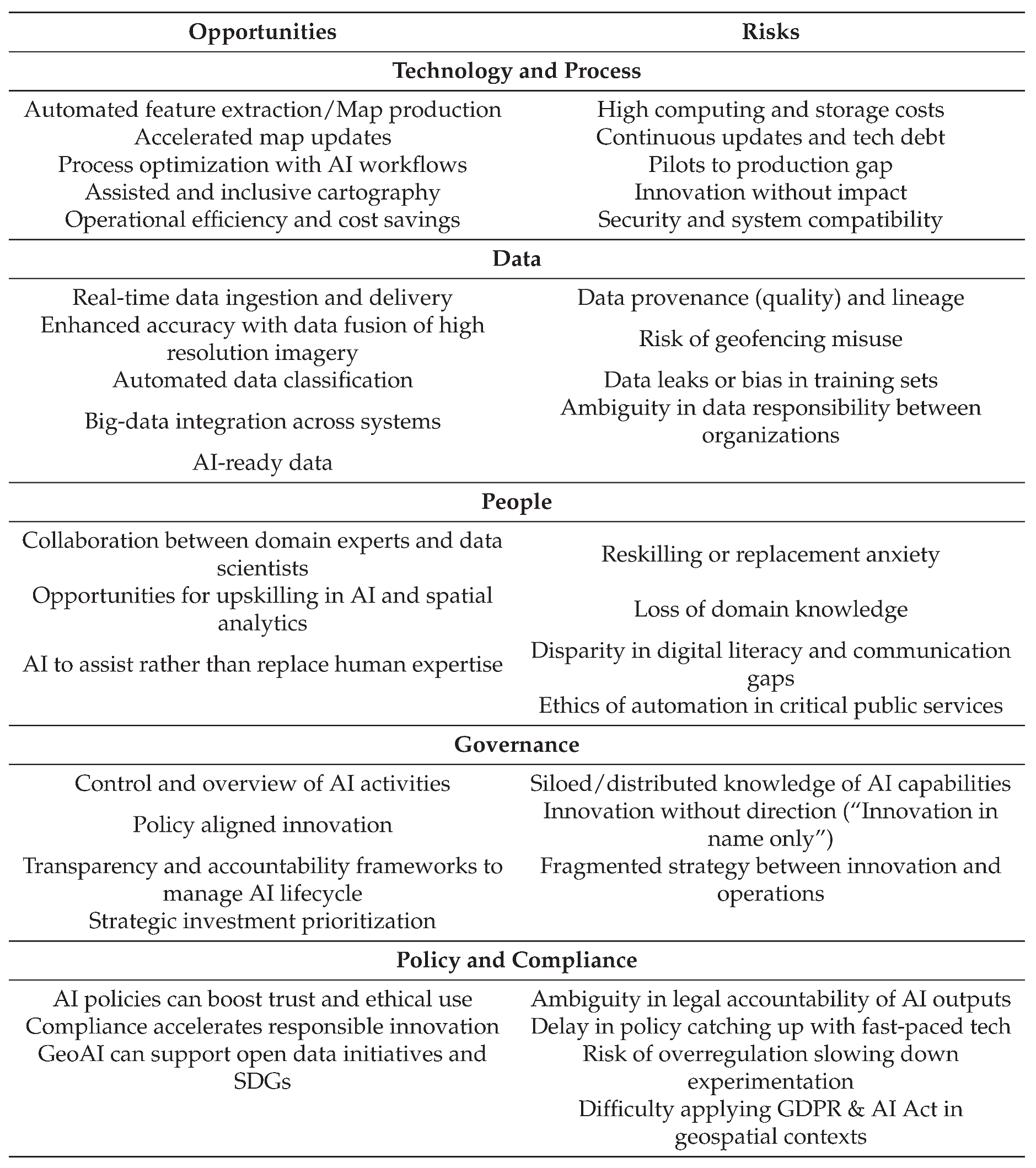

This research used a multi-perspective approach to analyze the opportunities and risks of GeoAI for topographic mapping within Kadaster. Kadaster strives for responsible innovation, transparency and accountability and upholding trust towards the citizens. Therefore, the interaction between technical, organizational and societal factors is central to ensure no crucial dimension is overlooked. Five dimensions which reflect these factors have been chosen to define and analyze the opportunities and risks. Technology and process, data, governance, people, and policy; these parameters do no operate in isolation (see

Figure 2), instead they are interdependent and therefore valuable to study for a balanced assessment, that aligns with the organization’s strategic goals and principles. These factors, are often used to measure an organizations ability to deliver in an technological era [

26]. In addition, the challenges mentioned earlier are driven by these dimensions. Therefore, evaluations based on these parameters prepares the organization to adapt to the complexity and inter-dependencies of real-world implementation of GeoAI. Successful adoption of GeoAI lies in the understanding how these domains influence each other and how well it can be integrated into the existing frameworks. Discussed below is a synthesis of how these domains connect, why they are important and where the critical points lie.

The

technology and process perspective examines the core AI methods, tools, and production flows involved in map-making. Infrastructure, automation and optimization are the key pillars. The

data perspective addresses the input quality, structure, and integrity of geospatial data that fuels the AI systems, in short the accuracy, access and risk. The

governance perspective explores internal oversight, accountability, trustworthiness, ethical implementation, and cross-institutional coordination. The

people perspective focuses on the changing roles, expertise needs, and organizational culture impacted by GeoAI adoption. Finally, the

policy and compliance perspective situates GeoAI within current and emerging regulatory frameworks, privacy laws, and institutional mandates. Each perspective highlights both opportunities and potential risks, helping to shape a strategic and sustainable path forward. We can also observe the relationship and inter-dependencies of these perspectives from the opportunities and challenges Geo-AI applications bring as presented in

Table 1. Although, most of the opportunities have been analysed from Kadaster’s perspective, they are generically applicable to most NMAs.

3. Synthesis of the Inter-dependencies

The following elaborations help understand the intricate yet strong interconnections between the dimensions and support the opportunities and risks that have been described.

Technology & Process — People: AI capabilities are only as effective as the people who design, deploy, and monitor them. While GeoAI enables assisted cartography, feature detection, and process optimization, it still relies heavily on domain-specific context for accurate interpretation. Loss of domain knowledge, due to over-reliance on automation or staff attrition, leads to the "black box problem", where AI makes decisions no one can fully explain or validate. Use of generative AI for mapping purposes can pose various risks especially when the outputs are not evaluated. The accuracy of the outputs is questioned or outputs are completely rejected leading to loss of trust. The missing link points to this particular relation and human-in-the-loop systems with explainability could be a future proofing strategy.

Data — Governance: AI models thrive on large, high-quality datasets, but who owns, curates, and governs these datasets becomes critical. In the absence of governance, poor data quality or synthetic data misuse can damage both performance and public trust. When this link is overlooked, one risk scenario could be a model failing during production creating an impact on costs for rework and reputational damage .

Governance — Policy: Governance ensures internal oversight, but without alignment with external regulatory frameworks, it is ineffective. Compliance needs governance mechanisms to translate laws into operational practice. If a tool violates regulation, there might be legal actions and operations might be halted. Early involvement of legal and compliance teams and processes where policy is translated to internal regulations helps overcome risks associated with this interdependency.

Technology & Process — Data: Even the most sophisticated AI model is only as good as the data feeding it. GeoAI-based map updates, real-time change detection, and inclusive visualizations require clean, current, and context-rich datasets. Mismatches between data, technology and process could lead to inconsistencies between model expectations and data structures. This in turn leads to errors, and the high cost of processing large datasets limits experimentation. Since NMAs deal with privacy sensitive data, decisions over open source vs proprietary models and infrastructure solutions is largely discussed and is a major source for stalled innovations. Focusing on scalable infrastructure planning and cloud optimization (private, public or hybrid) strategies can help overcome this risk scenario.

People — Governance — Policy: People drive ethical behavior. Even with laws in place, without organizational culture and staff understanding of compliance, policies are just checklists. This could be problematic for several reasons. Policies are designed to manage risks, but if employees don’t understand why they exist, compliance becomes mechanical. A checklist mindset often discourages proactive and adaptable behavior. For example, if new AI tools are introduced, but because they aren’t yet reflected in formal policy, staff may avoid using them or could misuse them without proper controls. Another example of ethical decision making beyond policy compliance is if an employee sees a privacy breach that technically isn’t covered by existing policy, they might ignore it instead of reporting it. This could be because they’re not empowered by a culture that values responsible data stewardship. Similarly, staff concerns about AI replacing jobs can lead to resistance. Lack of transparency in how AI affects employment, or failure to communicate safeguards, may erode employee trust and result in low adoption.

4. Towards Strategic GeoAI

While the previous section outlined individual opportunities and risks across five key perspectives: technology and process, data, people, governance, and policy and compliance, it is at the intersection of these dimensions where the most critical challenges often emerge. For example: Loss of domain knowledge or experts has internal and external drivers (think about organizational culture, austerity measures, technological developments, competitive labor market). Failures are rarely due to a single weak point but instead result from misaligned dependencies or gaps in coordination. Considering and evaluating the interconnected dimensions carefully, can lead to successful implementation or scaling of GeoAI. This section also draws inspiration from NMAs with best practices or

4.1. Integrated Strategic Vision

For successful GeoAI adoption in topographic mapping, a clear and organized strategy is key. With evolving technology, it’s impact and changing user needs, how to keep up and stay relevant? Serving trustworthy data is one side but how to do that efficiently and in time? In an era dominated by Google maps and instant geospatial content, topographic maps; an essential information source for navigational and spatial understanding are often overlooked or misunderstood by this generation. Many users are unaware of the accuracy, purpose and value that topographic mapping represents. To remain relevant and future-oriented, transforming public perception of mapping institutions is as important as investing in technological capabilities. SwissTopo, sets a good example of this with their SwissTopo mobile app, catering to the needs of the younger generation, engaging digitally native audience with interactive and useful products[

27]. Long term vision considering the influencing factors helps integrating the changing landscapes into existing workflows. Ordnance Survey Great Britain’s vision and work towards a MasterMap is definitely worth acknowledging [

28]. A strategic vision balances top-down implementation with feedback and innovations from bottom-up initiatives.

4.2. Principles for GeoAI adoption

The success or failure of technology is reliant on organizational principles. Especially with disruptive technologies like AI, reliance on technology alone does not guarantee success. Frameworks for sustainable and responsible AI deployment are recommended for transparency and explainability not only towards customers but also internally. We identified a few key organizational principles that play a key role in integrating GeoAI, instead of viewing it purely from a techno-centric perspective, which ensures to retain trust in mapping organizations.

Purpose over Technology: GeoAI adoption must begin with clarity of purpose, not merely because it is cutting edge and an appealing innovation. Rather than use deep learning because it is state of the art, NMAs should ask: how does this enhance data quality, accessibility, or public trust? It is not just about speeding up processes and technical efficiency but does it also have a broader purpose.

Human - centric by design: AI should be incorporated to assist and not to replace humans. At least in the topographic domain, it is to hard replicate the domain expertise completely and automatically without human intervention. Using AI to support cartographers in repetitive tasks helps retain human judgment in ambiguous or high-risk contexts. Co-designing and implementation with experts from various backgrounds ensures data relevance and usability. Human in the loop also accounts for oversight and maintaining documentation to preserve institutional knowledge and avoid over reliance on models to overcome fake geography [

29] as not all art and science can be fully automated.

Open and transparent systems: Trustworthy AI systems depend on transparency and explainability, especially in public-sector institutes like the NMAs. Prioritizing open data standards and clear documentation of process steps and model logic, making the outputs interpretable to technical and non-technical stakeholders and building feedback loops or traceability in decision making supports sustainable adoption. The users should be aware of which outputs were generated using AI, the quality of these outputs and the extent of autonomy of the models. Algorithm registers are a way of accomplishing this and in the Netherlands, public-sector organizations are obliged to register impactful and high-risk algorithms used within the organizations [

30] and soon this could be a norm in many countries [

31].

-

Ethical foundations: While ethics is a core consideration in AI, this paper does not fully unpack its complexity. Ethics spans a wide range of domains. One could start from the foundational ethical questions around what constitutes "good" vs "bad" use of AI. Then one could argue about fairness, justice and truth which vary by cultural and legal contexts. One could also discuss data ethics which concerns bias in training data, misuse of sensitive geospatial information and consent. Then there is another huge topic around environmental ethics, raising sustainability concerns. The institutionalization of ethical principles in governement agencies particularly within NMAs is complex due to varying roles and responsibilities of these institutions. It calls for not just policies but also monitoring mechanisms and leadership commitment [

32,

33].

Although ethics is acknowledged as central, a detailed ethical framework for GeoAI in topographic mapping is beyond the scope of this paper and could be developed as a follow-up agenda with multidisciplinary inputs.

4.3. Leveraging Strengths

GeoAI adoption does not require starting from scratch. The success of it lies in amplifying what already works well. Most of the organizations already have robust mapping workflows and the necessary domain expertise. The critical point is the AI transformational journey. Instead of scraping existing processes, the focus should be to embed AI where it enhances value, not where it introduces unnecessary complexity and risk. Initiatives should focus on identifying quick wins and tipping points for the biggest impact, that is focusing on low-risk, high-impact opportunities especially when faced with monetary constraints. Areas where there is already a clear business case, good quality data for training and where domain experts can guide the outputs effectively are low hanging fruits for quick wins. For example automated feature extraction in well known or small areas of interest. Embedding AI tools into existing operational workflows minimizes disruption or the need to redesign the whole process around AI. Change detection or feature updates can be integrated within current map maintenance or update cycles. The cartographic department of Cantabria, Spain is an example of how one could leverage strengths in spite of being a small team to create space for innovation without compromising what already delivers public value [

34].

4.4. Governance Models

For successful GeoAI adoption governance is vital. Important questions to consider are where should innovations related to GeoAI be organized? Who should steer these? How to operationalize successful innovations? When there is a problem who is the point of contact? How to encourage experimentation while managing risks? In the context of topographic mapping, data sources span multiple administrative levels and policies are set nationally or internationally. Alignment across various domains is needed to produce topographic information that is reliable. Governance determines where innovation is housed, how it is monitored and how risks are managed. Many organizations including Kadaster are now focusing on this aspect to take GeoAI from being a hopeful experiment to a sustainable operation. Another important aspect of governance is the room for co-creation and collaboration. When key strengths are missing in-house, reliance on other organizations, peers, research or industry to learn and co-create could really boost Geo-AI adoption. Recently, a Nordic initiative for research and innovation on responsible and ethical use of AI has been started [

35]. Such initiatives help in sharing and learning from experiences of other organizations, co-creation or reusing models which is not only efficient but also tackles the issue of energy consumption while training models.

4.5. Organizational readiness

Even with a compelling vision, cutting-edge technologies, guiding principles, and sound governance, the adoption of GeoAI will fall short without institutional readiness. GeoAI introduces new ways of working that require continuous learning and upskilling. GIS experts would need AI skills to interpret model outcomes or retrain models to get the required outputs. Topographic data operators would have to understand how to effectively integrate outputs from GeoAI to assist them in their work. Thus, AI literacy across roles, from operators to management, can lead to the required pragmatic outlook for AI deployments. In addition, technical expertise in siloed units must be distributed across the organization. Cross-functional teams break these isolated units and foster collaborative innovation that is easier to put in production. As part of this shift, institutions may require new roles that reflect governance strategies and ethical principles. AI ethics officers, data stewards or AI strategy leads can help in aligning innovation with production thereby reducing the current gap. These roles could also act as a bridge between technical developments and strategic oversight. Most crucially, organizations must foster a culture that is open to AI experimentation but grounded in trust and accountability.

5. Outlook

Adoption of AI in the topographic domain is complex and requires organization wide transformation. From change in our perspective towards technological advancements to process, organizational and behavioral change. These changes do not occur overnight but might take years or even decades. GeoAI presents a transformative opportunity for national mapping and cadastral agencies. Its potential depends on how well we integrate it into our work processes. Successful implementation of GeoAI requires a holistic approach; balancing innovation with governance, and automation with accountability. In addition to technology and data, people, governance and policy play a central role in the successful adoption of GeoAI. To harness GeoAI in topographic mapping processes and contribute effectively to the society with regard to the sustainable development goals, it is recommended that NMAs embrace collaboration, transparency, and adaptability. The authors foresee a strong focus on developing AI data standards and frameworks ensuring data lineage and quality. Collaboration across public, private and academic sectors will also be on the forefront as NMAs strive for digital sovereignty.

Author Contributions

B.K and V.A conceptualized and set the scope for the research. B.K conducted the formal analysis and implemented the research. Original draft, writing and editing was conducted by B.K. V.A reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge colleagues who have given feedback during the analysis phase and help in understanding the many complex perspectives and those who have reviewed the manuscript. Special thanks to peers from other NMAs, whose insightful discussions were instrumental in validating the research findings. The authors are also thankful to Izabela Karsznia, for providing valuable input for this research on map generalization using AI. “During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-4) for grammatical corrections and for resolving document compilation errors. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, W. GeoAI: Where machine learning and big data converge in GIScience. Journal of Spatial Information Science, pp. 71–77. Number: 20. 2020; 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.C.; Çöltekin, A.; Griffin, A.L.; Ledermann, F. Cartography in GeoAI: Emerging Themes and Research Challenges. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on AI for Geographic Knowledge Discovery, Hamburg Germany, nov 2023. [CrossRef]

- Usery, E.L.; Arundel, S.T.; Shavers, E.; Stanislawski, L.; Thiem, P.; Varanka, D. GeoAI in the US Geological Survey for topographic mapping. Transactions in GIS 2022, 26, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheider, S.; Richter, K.F.; Janowicz, K. GeoAI and Beyond: Interview with Krzysztof Janowicz. KI - Künstliche Intelligenz 2023, 37, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI). In Geography; Oxford University Press, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Janowicz, K.; Gao, S.; McKenzie, G.; Hu, Y.; Bhaduri, B. GeoAI: spatially explicit artificial intelligence techniques for geographic knowledge discovery and beyond. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2020, 34, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, M.; Biljecki, F.; Hu, T.; Fu, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; et al. Mapping the landscape and roadmap of geospatial artificial intelligence (GeoAI) in quantitative human geography: An extensive systematic review. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2024, 128, 103734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, G.; Xie, Y.; Jia, X.; Lao, N.; Rao, J.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Chiang, Y.Y.; Jiao, J. Towards the next generation of Geospatial Artificial Intelligence. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2025, 136, 104368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Kalacska, M.; Gašparović, M.; Yao, J.; Najibi, N. Advances in geocomputation and geospatial artificial intelligence (GeoAI) for mapping. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2023, 120, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.; Heitzler, M.; Hurni, L. A fast and effective deep learning approach for road extraction from historical maps by automatically generating training data with symbol reconstruction. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2022, 113, 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hsu, C.Y. GeoAI for Large-Scale Image Analysis and Machine Vision: Recent Progress of Artificial Intelligence in Geography. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2022, 11, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierdicca, R.; Paolanti, M. GeoAI: a review of artificial intelligence approaches for the interpretation of complex geomatics data. Geoscientific Instrumentation, Methods and Data Systems 2022, 11, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, O.; Avcı, M.; Çiğdem, S.; Özdemir, O.; Nar, F.; Kudinov, D. Integrating SAM and LoRA for DSM-Based Planar Region Extraction in Building Footprints. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anciukevičius, T.; Xu, Z.; Fisher, M.; Henderson, P.; Bilen, H.; Mitra, N.J.; Guerrero, P. RenderDiffusion: Image Diffusion for 3D Reconstruction, Inpainting and Generation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, jun 2023; pp. 12608–12618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sester, M.; Feng, Y.; Thiemann, F. BUILDING GENERALIZATION USING DEEP LEARNING. ISPRS - International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, -4. [CrossRef]

- Karsznia, I.; Przychodzeń, M.; Sielicka, K. Methodology of the automatic generalization of buildings, road networks, forests and surface waters: a case study based on the Topographic Objects Database in Poland. Geocarto International 2020, 35, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Raninen, J.; Hattula, E.; Kettunen, P.; Koski, C.; Jussila, A.; Oksanen, J. Artificial intelligence improves the National Land Survey’s topographic data accuracy, 2023.

- Walter, C. Future trends in geospatial information management: the five to ten year vision. Technical report, United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management, 2020.

- Basisregistratie Topografie (BRT) - Kadaster.nl zakelijk. https://www.kadaster.nl/zakelijk/registraties/basisregistraties/brt. Accessed: 09-06-2025.

- Kausika, B.B.; Nijmeijer, D.; Reimerink, I.; Brouwer, P.; Liem, V. GeoAI for detection of solar photovoltaic installations in the Netherlands. Energy and AI 2021, 6, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, L.; Spanjersberg, I.; Ryden, A.; Rijsdijk, M. AI in Core Business Processes of NMCAs. Workshop report, EuroSDR, 2025.

- Xie, Y.; Wang, Z.; Mai, G.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.; Gao, S.; Wang, S. Geo-Foundation Models: Reality, Gaps and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Hamburg Germany, nov 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kuckreja, K.; Danish, M.S.; Naseer, M.; Das, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S. GeoChat: Grounded Large Vision-Language Model for Remote Sensing, 2023. arXiv:cs.CV/2311.15826].

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, L.; Ke, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yan, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W. Towards Vision-Language Geo-Foundation Model: A Survey, 2024. 1: Version Number; 1. [CrossRef]

- Van Altena, V. Op weg naar een onderzoeksagenda voor kartografie, topografie en geo-informatie (2023-2028). Technical report, Dienst voor het Kadaster en de Openbare Registers: Directie Data, Governance & Vernieuwing – Onderzoek, Apeldoorn, 2023.

- Wong, B.; Sharp, A.; Bordiya, H. Assess Your AI Maturity. https://www.infotech.com/research/ss/assess-your-ai-maturity. Accessed : 25-11-2024.

- Wigley, M.; Pippig, K.; Forte, O.; Denier, S.; Geisthövel, R. A New Swiss Map Generation for Mobile Use. Abstracts of the ICA 2023, 6, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About OS MasterMap Topography Layer | Blog |, OS. https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/blog/all-about-os-mastermap-topography-layer, 2020. Accessed: 09-06-2025.

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, S.; Xu, C.; Sun, Y.; Deng, C. Deep fake geography? When geospatial data encounter Artificial Intelligence. Cartography and Geographic Information Science 2021, 48, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Algorithm Register of the Dutch government. https://algoritmes.overheid.nl/en. Accessed : 09-06-2025.

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act) (Text with EEA relevance). http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj/eng, 2024. Legislative Body: CONSIL, EP. 13 June.

- Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Coeckelbergh, M.; López de Prado, M.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Connecting the dots in trustworthy Artificial Intelligence: From AI principles, ethics, and key requirements to responsible AI systems and regulation. Information Fusion 2023, 99, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M. Employee Engagement: The Last Mile of Compliance & Ethics. https://grc2020.com/2024/11/13/employee-engagement-the-last-mile-of-compliance-ethics/, 2024. Accessed: 04-06-2025.

- Detalle - Gobierno - cantabria.es. https://www.cantabria.es/detalle/-/journal_content/56_INSTANCE_DETALLE/16413/48828895. Accessed: 10-06-2025.

- A Nordic initiative for research and innovation on responsible and ethical use of Artificial Intelligence. https://www.nordforsk.org/2024/nordic-initiative-research-and-innovation-responsible-and-ethical-use-artificial-intelligence, 2024. Accessed: 09-06-2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).