1. Introduction

The rising global population, coupled with environmental degradation and growing pressure on agricultural systems, has significantly increased the demand for sustainable protein sources [

1,

2,

3]. Conventional livestock production, while an essential source of dietary protein, remains resource-intensive—requiring extensive land, water, and feed inputs [

4,

5]. Moreover, livestock farming contributes substantially to greenhouse gas emissions and ecosystem degradation [

6,

7,

8]. In response, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and several researchers have identified edible insects, particularly crickets, as a promising alternative source of high-quality protein. Crickets (

Acheta domesticus) are increasingly recognized for their favorable nutritional profile, including protein content comparable to that of traditional meat and fish, along with balanced amino acids, vitamins, and minerals [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Additionally, they require significantly less land, water, and feed than conventional livestock, making them a highly efficient and environmentally sustainable protein option [

14,

15]. As a result, insect farming is gaining global momentum, particularly in developing regions where access to conventional protein sources may be limited [

16]. In Thailand, where cricket farming is well-established, it serves as a critical livelihood and food security strategy [

17,

18].

However, a major limitation to the scalability and economic sustainability of cricket farming is the high cost of feed, which often accounts for more than 50% of total production expenses [

18,

19]. While commercial cricket feed is nutritionally adequate, it is relatively expensive [

20,

21], prompting small-scale farmers to experiment with alternative feed sources such as fresh plant materials. Yet, fresh plant feed presents notable challenges, including high moisture content, inconsistent nutritional composition, rapid spoilage, and increased risk of waste generation and ammonia emissions [

22,

23,

24]. These issues reduce feed efficiency and increase labor and maintenance costs, undermining long-term viability [

25].

To address these challenges, researchers have explored the use of insect-based ingredients—particularly black soldier fly larvae (BSFL,

Hermetia illucens)—in animal diets. BSFL offer a sustainable, high-protein alternative capable of converting organic waste into biomass, with reported crude protein and fat contents of approximately 42–45% and 35%, respectively [

26,

27,

28]. Their inclusion in poultry and aquaculture feeds has demonstrated promising results in terms of growth performance, environmental sustainability, and cost-effectiveness [

29,

30,

31]. Importantly, BSFL can be produced locally, reducing dependency on imported feed ingredients such as fishmeal and soybean meal [

32].

While several studies have explored BSFL use in poultry and aquaculture feed, relatively few have evaluated their integration into cricket feed formulations—particularly using economically optimized recipes tailored for smallholder conditions in Southeast Asia. In particular, there remains limited research on the optimal blending ratios of BSFL with locally available ingredients that balance nutritional adequacy, feed conversion efficiency, and cost reduction in cricket farming systems. Furthermore, the lack of standardized feed formulation approaches, such as the Pearson’s square method, contributes to variation in feed quality and economic performance across farms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ingredient Materials

This study focused on the development of cost-effective cricket feed using locally sourced ingredients as substitutes for expensive commercial feeds. To ensure economic feasibility and nutritional adequacy, selected ingredients were required to be nutrient-rich, affordable, readily available, and suitable for long-term use by small-scale farmers. The feed ingredients included BSFL, soybean meal, corn meal, rice meal, and fermented cassava pulp. Cereal-based components such as corn and rice bran were procured from a local animal feed supplier, while fresh BSFL were obtained from a regional Thai producer. Upon delivery, BSFL were inspected for vitality and size uniformity, ensuring that only live and active larvae were used, following the guidelines of [

27,

32].

To reduce microbial load and preserve nutritional integrity, the larvae were sieved to remove residual feces and debris, then briefly boiled for 10–15 seconds, as recommended by Surendra [

33]. Following boiling, the larvae were cooled on trays and stored at 4 °C to maintain freshness prior to processing.

The initial moisture content of the BSFL was determined using the oven-drying method (ISO 1442:1973), wherein approximately 5 g of BSFL biomass was dried at 105 °C for 72 hours in triplicate. The average moisture content was 64.83 ± 2% (wet basis), consistent with prior reports [

18]. The larvae were then further dried in a hot-air oven at 60 °C until reaching a final moisture content of approximately 10% w.b., following protocols adapted from Ref. [

14] and [

33].

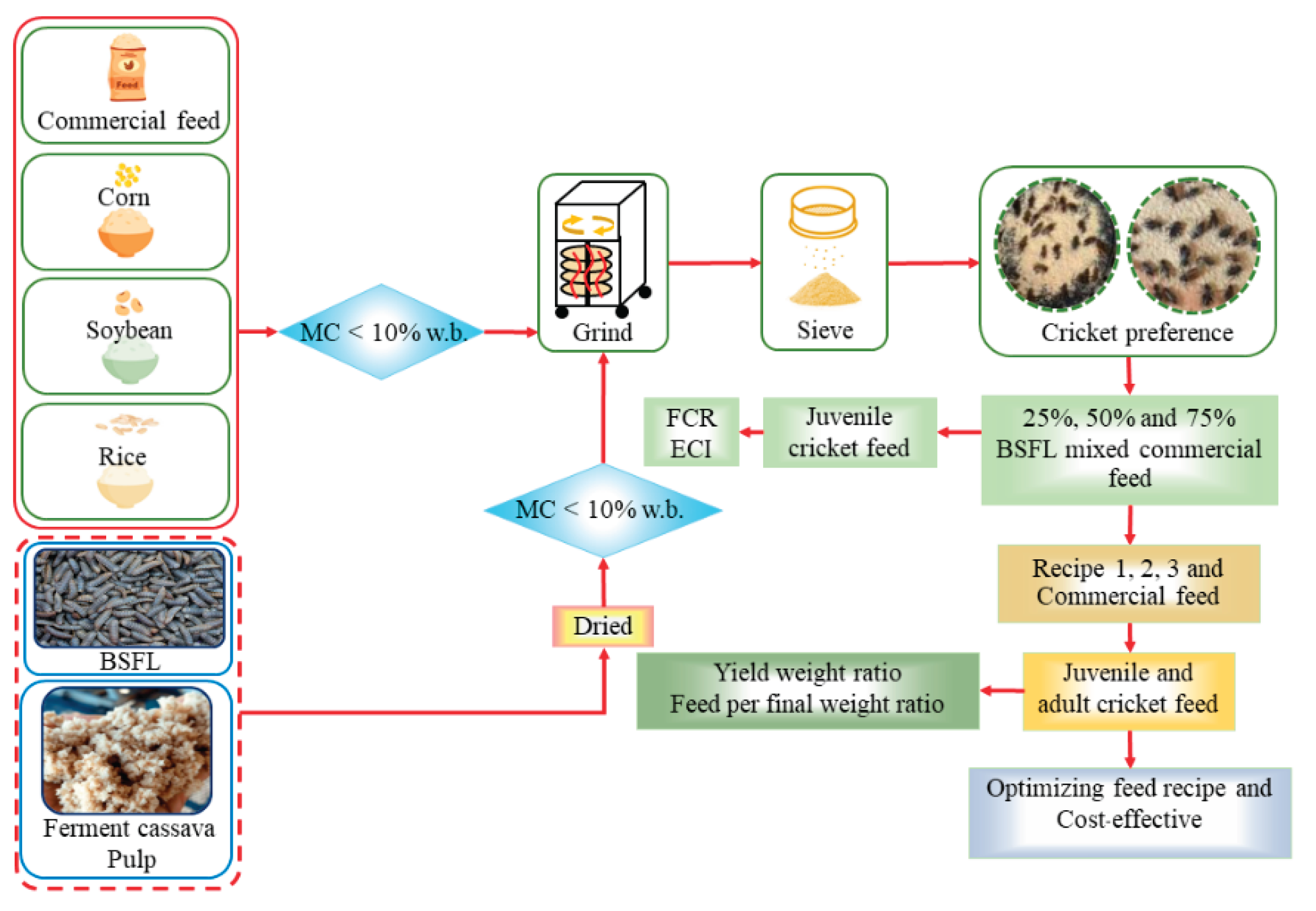

All feed ingredients (

Figure 1) were ground into fine powders using a standard laboratory grinder and passed through a No. 40 mesh sieve to ensure uniform particle size, facilitating consistent mixing and improved feed intake, as recommended by Miech [

34].

The data in

Table 1 highlight the nutritional diversity among ingredients, particularly in protein content, which ranged from 8% to 45%, and fat content, from 0.86% to 6.6%. Cricket feed formulations typically aim for a protein content of at least 21%, matching commercial feed benchmarks to support rapid growth due to the crickets’ short life cycle. However, excessive protein increases cost, and previous studies suggest that 15% protein may be sufficient for optimal growth [

38]. Thus, strategically blending local ingredients can offer a nutritionally balanced and cost-efficient alternative for smallholder cricket production.

2.2. Cricket Farming Setup and Feeding

Cricket farming experiments were conducted in custom-built enclosures constructed from gypsum board, each measuring 1.2 m in width, 0.8 m in length, and 0.6 m in height. The tops of the enclosures were covered with nylon mesh netting to prevent cricket escape and to protect against common predators such as birds, lizards, and geckos. Internally, egg tray paper was used to provide vertical surface area and shelter, facilitating molting and reducing cannibalism—a behavior known to occur during vulnerable molting stages [

39].

Each production unit had the capacity to yield approximately 10–15 kg of crickets per cycle, with the cycle duration ranging from 40 to 45 days, depending on variables such as cricket species, initial stocking density, feed regime, and environmental conditions. Environmental factors, particularly temperature and humidity, were recognized as critical parameters influencing cricket growth, molting frequency, and feed conversion [

14].

Crickets were fed commercial feed twice daily, with feed quantities adjusted according to developmental stage and population density to reduce excess waste. Maintaining a clean rearing environment and tailoring feed volume to age-specific metabolic demands are essential to preventing ammonia buildup and supporting colony health [

24,

34]. In the late developmental phase, fresh plant material was occasionally provided to supplement the diet and maintain feed engagement, particularly when appetite declined near maturity. Water was supplied ad libitum using shallow plastic containers placed inside the enclosures. Ensuring consistent hydration is especially important during molting periods, when crickets are physiologically vulnerable to dehydration stress [

39].

2.2.1. Feed Testing Procedures

Crickets (

Acheta domesticus) were sampled by weight to minimize handling stress and ensure uniformity. Feed testing was conducted through a three-stage experimental framework (

Figure 1):

1) Feed Preference Assessment

The first phase involved a full-scale pond trial to evaluate crickets’ preference for different individual ingredients (see

Section 2.3). The test followed established palatability protocols for insect feed evaluation [

40], with residual feed mass used to assess acceptability.

2) BSFL-to-Commercial Feed Ratio Trials

The second phase used a scaled-down pond (1 m² area) representing approximately one-third the size of a standard farmer’s unit to test various mixing ratios of BSFL and commercial feed (see

Section 2.4). This step replicated real-world farming conditions in a controlled environment to determine optimal inclusion rates of BSFL [

14].

3) Pearson’s Square-Based Feed Formulation

In the third phase, experimental feed recipes were formulated using the Pearson’s square method, aiming for a minimum crude protein content of 21%, equivalent to the commercial control feed [

27]. This stage focused on mixing BSFL with soybean meal, corn meal, and rice bran to generate nutritionally balanced, cost-effective feeds tailored for smallholder cricket farmers (see

Section 2.5).

2.3. Cricket Feed Preference Testing

Prior to formulating optimized feed mixtures, a feed preference assessment was conducted to evaluate the palatability of individual feed ingredients. The goal was to identify components that were readily consumed by crickets, thereby minimizing feed residue, which can degrade and release ammonia gas—posing health risks and increasing maintenance burdens [

34]. Such preference evaluations are critical in insect feed formulation studies to enhance feed efficiency and reduce waste [

40]. The selected ingredients—BSFL, soybean meal, corn meal, rice meal, and fermented cassava pulp—were ground into fine powders using a household blender and passed through a mesh sieve to ensure consistent particle size. This grinding process is essential for improving feed texture and facilitating ingestion [

27].

For each ingredient, 50 g of the powdered sample was placed in separate containers, each housing 21-day-old juvenile crickets (

Acheta domesticus), a stage selected for its responsiveness to dietary evaluation [

34]. Two replicates per ingredient were used.The crickets were allowed to feed for 120 minutes, a duration chosen based on prior studies evaluating insect feed preferences. After the feeding period, residual feed was collected and weighed to calculate the percentage of uneaten material. Ingredients with the lowest residuals were deemed most acceptable and prioritized for inclusion in the subsequent experimental feed formulations. Ingredients with high residuals were excluded due to their potential to contribute to waste accumulation and suboptimal pond hygiene [

39].

2.4. BSFL and Commercial Feed Ratio Testing

To determine the optimal incorporation level of BSFL into a commercial diet, four weight-to-weight (w/w) blending ratios were tested: 25:75, 50:50, 75:25, and 0:100 (commercial feed only). This experimental design was informed by previous studies examining the dietary inclusion of BSFL in insect production systems [

14,

27]. The BSFL powder was prepared using a standardized drying and grinding protocol to ensure consistency. Each diet was tested using 500 g of 21-day-old crickets, reared in gypsum board ponds of 1 m²—a dimension representative of scaled-down farmer rearing units. The feeding regime mimicked practical farming conditions, with rations provided twice daily (morning and evening). Feed waste was monitored closely to prevent accumulation, which could otherwise result in ammonia buildup and increased mortality [

34]. Feed consumption was measured throughout the 14-day experimental period, after which the crickets were harvested and weighed. Each treatment group was replicated five times to ensure statistical validity. The results provided insights into the feed conversion performance and growth responses across different BSFL inclusion levels.

2.5. Practical Cricket Feed Recipe Development

Following ingredient evaluation and BSFL ratio testing, three cost-effective feed recipes were formulated using the Pearson’s square method [

27], ensuring each blend met the minimum 21% crude protein requirement observed in commercial feeds (see

Table 3). The formulations incorporated BSFL along with soybean meal, corn meal, rice meal, and commercial feed in varying proportions. To assess feed performance across life stages, two groups of crickets were selected: 900 g of reproductive-stage crickets (3 weeks old) and 500 g of mature adult crickets. The sample sizes reflected differences in average individual weight and ensured proportional stocking across test ponds of 1 m² each. Reproductive-stage crickets were expected to have higher feed intake to support growth and reproductive development, while adult crickets generally require reduced protein inputs and may be supplemented with low-cost plant material.

All feed trials were conducted under controlled conditions designed to simulate real-world cricket farming environments [

39]. To ensure repeatability, each recipe was tested

three times, and performance was benchmarked against a commercial control diet. Key performance indicators included feed conversion ratio (

FCR) and growth yield, which were monitored until harvest. This comparative analysis aimed to identify the most efficient, affordable, and practical feed formulation for continuous cricket farming operations [

34].

2.6. Performance Indicators

Cricket production involves large-scale rearing, during which crickets undergo multiple molts. The molting process renders them physiologically vulnerable, often leading to temporary weight loss and increased susceptibility to cannibalism [

39]. Consequently, final body weight may increase, decrease, or remain unchanged relative to initial body weight, even though overall size typically increases during development.

To assess the nutritional performance of each feed treatment, this study employed three key quantitative indicators:

Feed Conversion Ratio (

FCR) measures the efficiency with which crickets convert feed into body mass. It is defined as the amount of feed consumed per unit of weight gained during the experimental period:

In essence,

FCR is the mathematical relationship between the input (feed) and the weight gain of the cricket population. This metric is commonly used in insect farming to assess feed efficiency [

14].

Efficiency of Conversion of Ingested Food (ECI) quantifies the proportion of ingested feed that is successfully converted into body mass, expressed as a percentage:

This indicator reflects nutrient assimilation efficiency, which is critical in evaluating alternative feeds like BSFL [

34]. High ECI values indicate better conversion of feed nutrients into cricket biomass.

Yield Weight (Wy) represents the final weight of crickets as a percentage of their initial weight, capturing net growth relative to initial biomass:

where Wy is yield weight (%), Wf is final weight of the cricket population (g), and Wi is initial weight of the cricket population (g). This indicator was particularly useful for comparing feed efficiency across juvenile and adult cricket stages.

2.7. Data Analysis

Experimental results from feed preference tests, feed ratio trials, and practical recipe evaluations were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to detect statistically significant differences among treatment means. When significant differences were found (p < 0.05), Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was applied for post hoc multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0.2.0 (Released 2023, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

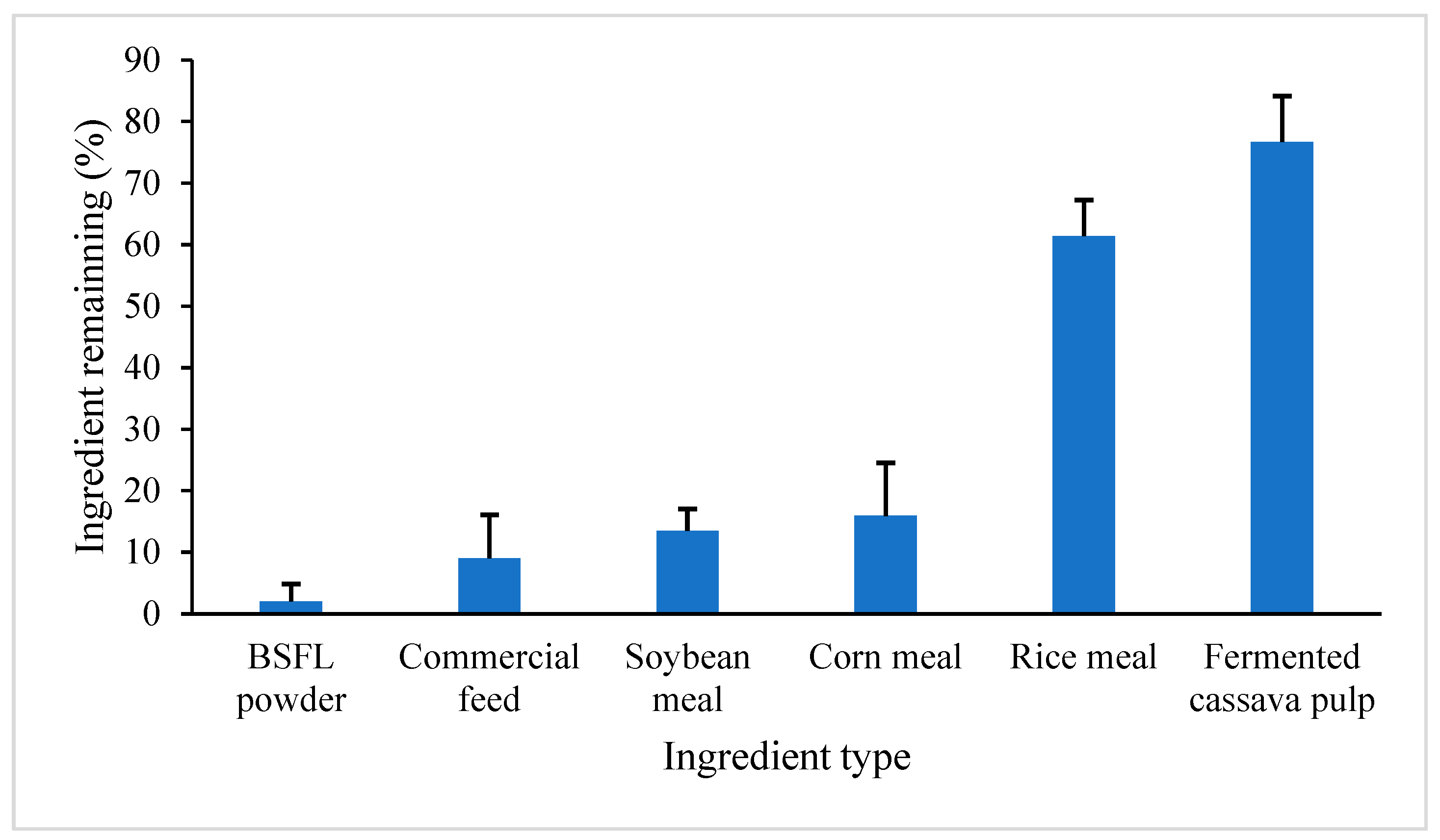

3.1. Ingredient Feed Preference

The feeding behavior of

Acheta domesticus was monitored over a 120-minute period to assess their preference for individual feed ingredients. Feed consumption was visually observed, and the residual quantity of each feed type was measured at the end of the test to quantify palatability. The results (

Figure 2) demonstrated that BSFL were the most preferred ingredient, exhibiting the lowest residual amount at 2%. This finding aligns with previous research highlighting the high palatability of BSFL due to their elevated protein (up to 45%) and lipid content, which enhance feed attractiveness and nutritional quality [

27,

31]. Commercial feed was the second most consumed, leaving a 9% residual, indicating good acceptability among the crickets.

Studies have emphasized that palatability plays a critical role in feed selection, with ingredients high in essential amino acids, digestible protein, and favorable odor profiles being preferred by omnivorous insects [

42,

43]. The preference for BSFL is further supported by its balanced amino acid profile and favorable texture post-processing, which improves intake among juvenile and adult stages. These results underscore the importance of ingredient selection in feed formulation, particularly when aiming to reduce waste and optimize feeding efficiency in mass-rearing systems. Moderate preferences were observed for soybean meal and corn meal, which resulted in residuals of 13.46% and 15.90%, respectively. In contrast, rice meal showed a high residual value of 61.41%, and fermented cassava pulp exhibited the highest residual at 76.71%. These elevated residuals suggest that crickets were less inclined to consume these ingredients, likely due to their coarse texture, high fiber content, and lack of attractive odor, as similarly reported by Rumpold and Schlüter [

40]. Previous studies have shown that fiber-rich and poorly digestible feed components negatively affect feed palatability and intake behavior in crickets and other insects [

34,

44]. Furthermore, cassava pulp’s low protein density and possible fermentation by-products may deter feeding, especially in juvenile stages that require energy-dense and protein-rich diets [

45].

Based on these findings, rice meal and fermented cassava were excluded from subsequent feed formulations to prevent waste accumulation and degradation, which can negatively affect pond hygiene and ammonia levels. In contrast, BSFL, commercial feed, soybean meal, and corn meal were identified as the most suitable components for inclusion in cost-effective cricket feed formulations, balancing nutritional value with feed acceptability.

3.2. BSFL and Commercial Feed Combination

To evaluate the effectiveness of incorporating BSFL into commercial cricket feed, feeding trials were conducted on 2-week-old

Acheta domesticus over a 15-day period. Each trial started with 500 grams of live crickets per sample (

Table 2), with feed portions adjusted daily based on observed consumption behavior. Crickets often reduce intake when feed is oversupplied, a phenomenon linked to their selective feeding and preference for novel food sources [

39]. Efficient feed intake regulation is critical in minimizing waste and optimizing nutrient absorption [

34,

42].

The results demonstrated significant differences in

FCR and

ECI across feed formulations. The

FCR for 100% commercial feed was 4.78, indicating that 4.78 g of feed were needed for a 1 g weight gain. In contrast, mixtures containing 25% and 50% BSFL yielded lower

FCR values of 3.66 and 2.25, respectively, signifying improved feed efficiency [

27]. The inclusion of BSFL at moderate levels enhances feed digestibility and provides a richer protein-lipid profile [

43,

44]. However, when BSFL content increased to 75%, cricket yields declined, and weight loss occurred, rendering

FCR and

ECI calculations not computable ("n.c.") due to final weights being lower than initial weights. This observation aligns with previous findings that excessive BSFL inclusion can disrupt nutrient balance and lead to metabolic inefficiencies [

14,

31].

ECI results followed a similar trend. The highest ECI was observed at 50% BSFL inclusion (44.38%), indicating optimal conversion of feed to body mass. In contrast, commercial feed alone resulted in an

ECI of 32.21%, reaffirming the efficiency of BSFL-enhanced diets. These findings underscore BSFL’s potential as a sustainable and effective feed ingredient, provided inclusion levels are optimized to maintain nutrient balance, cost efficiency, and growth performance [

45].

3.3. Ingredient Ratio Recipes

Feed formulation using the Pearson’s Square method resulted in three experimental recipes based on BSFL, soybean meal, corn meal, and rice meal (

Table 3). The formulation targeted a minimum protein content of 21%, consistent with commercial feed standards, while reducing cost by utilizing readily available local ingredients [

27]. BSFL inclusion levels were 15.80%, 20.61%, and 22.63% in Recipes 1, 2, and 3, respectively, with Recipe 3 formulated entirely without commercial feed.

Maintaining feed quality during storage was a key consideration, with all recipes demonstrating moisture contents well below the 13% wet basis (w.b.) threshold recommended for preventing mold and spoilage [

14]. Moisture levels were 10.14%, 8.25%, and 8.18% w.b. for Recipes 1–3, respectively, ensuring long-term stability. This aligns with findings from insect feed stability research, where excessive moisture is linked to microbial contamination risks [

46]. In terms of cost-effectiveness, the results showed clear advantages over the commercial control (Recipe 4), which currently retails at 21 THB/kg. Cost savings were estimated at 36.58%, 33.25%, and 40.71% for Recipes 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The incorporation of BSFL and regionally sourced components significantly reduced dependency on commercial inputs without compromising nutritional quality—a trend also reported in recent evaluations of insect-based feeds [

44,

47].

Table 3.

Ingredient ratios for cricket feed recipes (100 kg total weight basis).

Table 3.

Ingredient ratios for cricket feed recipes (100 kg total weight basis).

| Feed ratio (%) |

Recipe

1 |

Recipe

2 |

Recipe

3 |

Recipe

4* |

| BSFL powder |

15.80 |

20.61 |

22.63 |

|

| Soybean meal |

19.98 |

14.56 |

15.99 |

|

| Corn meal |

31.61 |

29.12 |

31.97 |

|

| Rice meal |

21.74 |

17.86 |

29.41 |

|

| Commercial feed |

10.87 |

17.86 |

- |

100.00 |

| Total weight (kg) |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

| Moisture content (%w.b.) |

10.14 |

8.25 |

8.18 |

7.41 |

| Reduce cost (%) |

36.58 |

33.25 |

40.71 |

- |

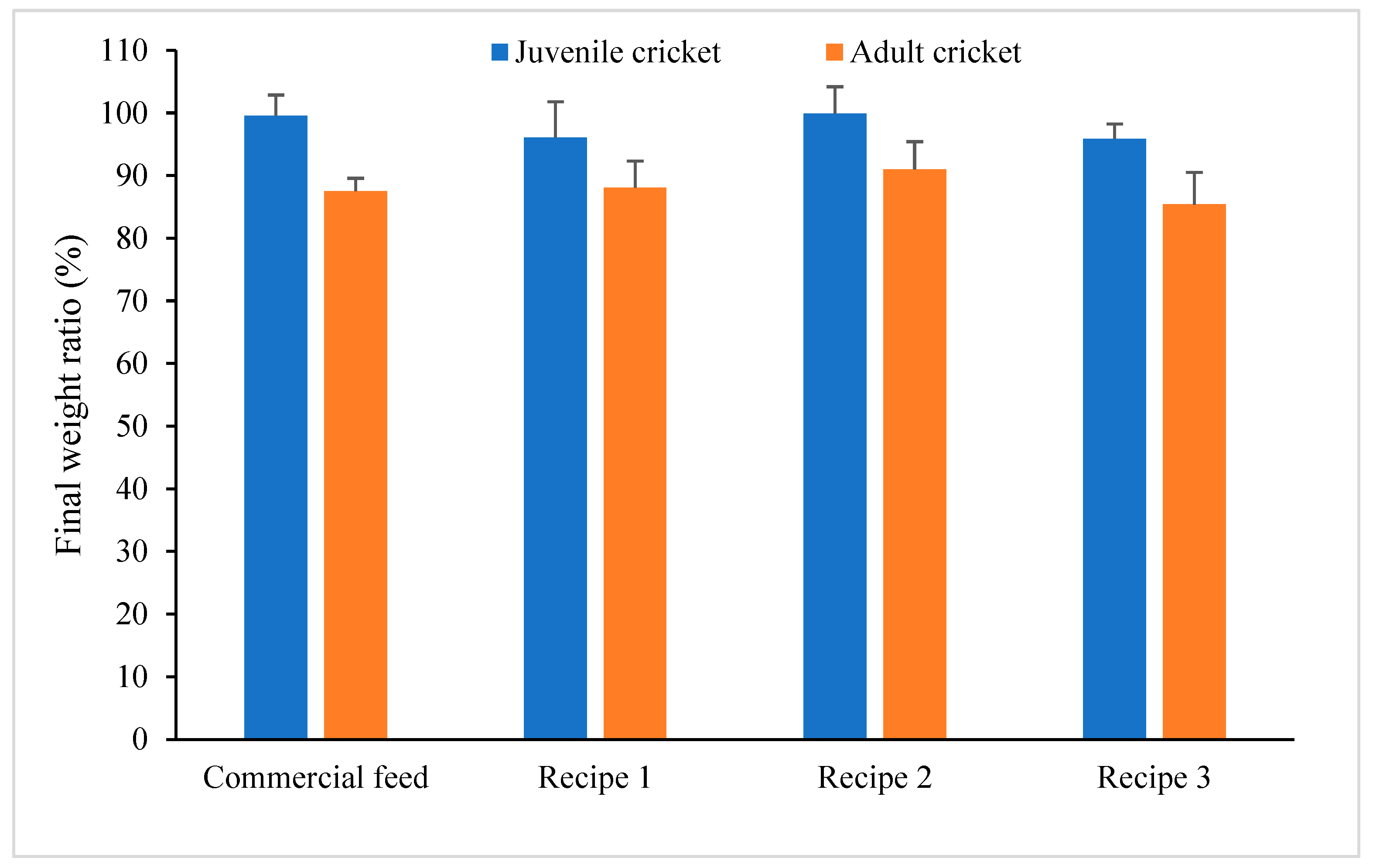

3.4. Performance of Crickets Fed Different Recipes

Figure 3 presents the results of feeding trials comparing the growth performance of juvenile and adult

Acheta domesticus reared on three experimental feed recipes against a commercial feed (Recipe 4). Juvenile crickets fed Recipe 2 achieved the highest yield at 99.89% of their initial weight, marginally surpassing the yield from commercial feed (99.56%). This performance is attributed to Recipe 2’s optimal nutrient profile, which included 24.9% crude protein and 8.3% fat, levels that support rapid juvenile growth and development [

31,

42]. Recipes 1 and 3 resulted in slightly lower yields of 96.11% and 95.89%, respectively.

For adult crickets, yields were generally lower due to reduced feed intake and elevated ambient temperatures (35–40°C) during the trial period, which are known to suppress feeding activity and growth in ectothermic insects [

48]. Nevertheless, Recipe 2 again outperformed the other formulations, achieving a yield of 91.0% compared to 87.53% from the commercial control. The consistent superior performance of Recipe 2 across both age groups highlights its balanced nutrient profile, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for practical farm applications [

47].

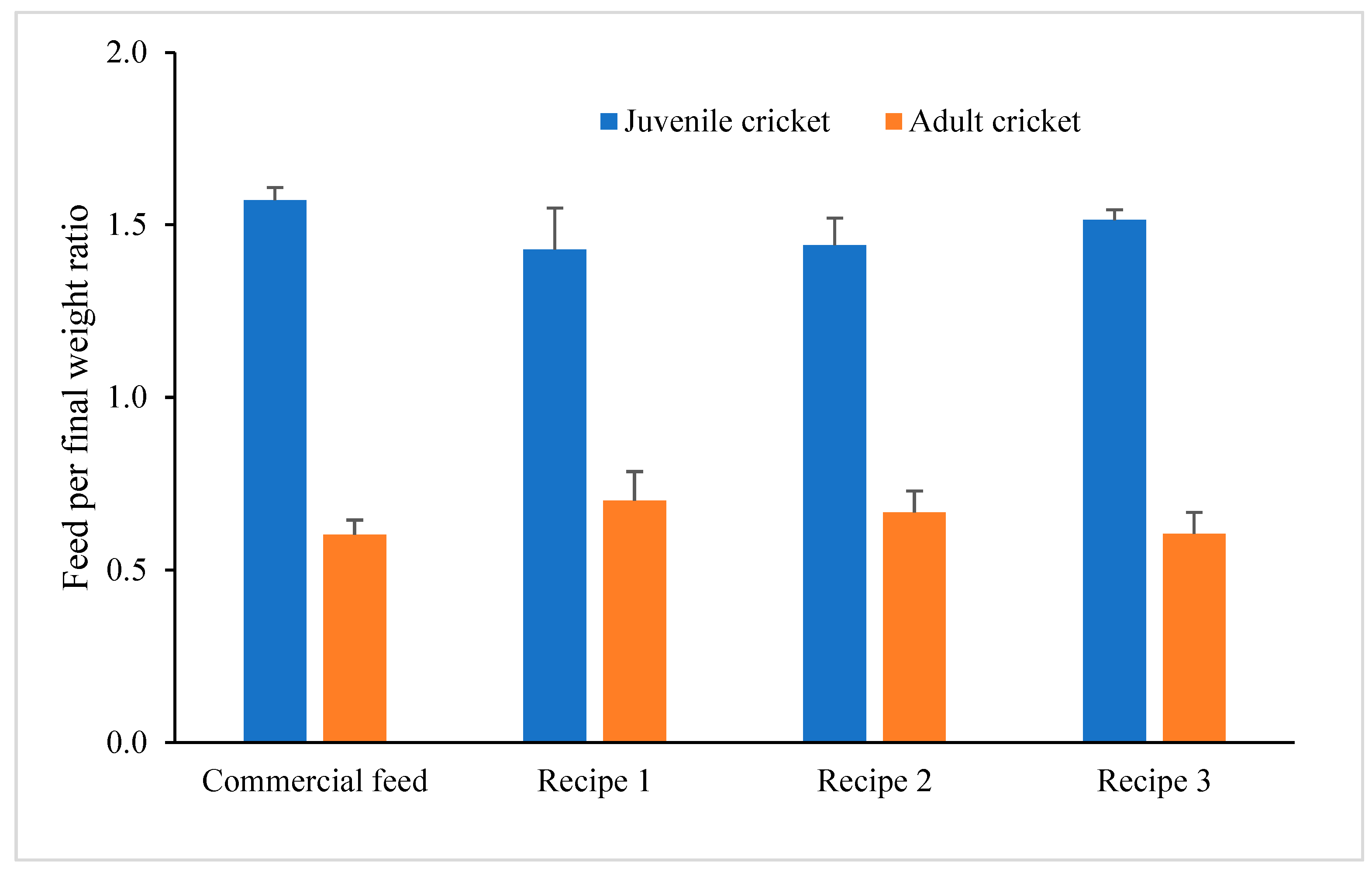

Figure 4 illustrates the feed-to-weight gain ratios for each recipe. Juvenile crickets exhibited higher feed consumption relative to their body weight, ranging from 1.43 to 1.57 g of feed per gram of body weight gained, reflecting their intense anabolic phase. In contrast, adult crickets consumed only 0.60 to 0.70 g/g, as their metabolic rate and growth slow after maturity [

10]. Notably, Recipe 2 again proved the most efficient, requiring only 1.44 g of feed per gram of juvenile weight gain, versus 1.57 g for commercial feed. This reflects improved feed conversion efficiency, an essential parameter for sustainable insect production [

44].

These findings corroborate prior studies, including Miech et al.[

34], who reported suboptimal growth in crickets fed high-fiber, poorly digestible diets. Halloran et al. [

39] similarly emphasized the need for well-balanced insect diets to avoid metabolic inefficiencies and growth suppression. Therefore, Recipe 2 emerges as a nutritionally and economically viable alternative to commercial cricket feed, especially for small- to medium-scale insect farming operations in tropical climates.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the economic viability and biological performance of locally formulated cricket feed, emphasizing BSFL as a sustainable and cost-effective protein source. The findings highlight several critical insights regarding feed preference, feed conversion efficiency, and growth performance in

Acheta domesticus. Cricket feed preference testing revealed that BSFL powder was the most palatable among tested ingredients, followed by commercial feed and soybean meal. These findings align with Newton et al. [

27], who reported that BSFL possess high levels of digestible protein and lipid content, enhancing palatability and growth response in insect larvae [

27,

28].

Ingredients such as fermented cassava and rice meal, which had significantly higher residual levels, were deemed unsuitable due to their low preference and risk of promoting feed spoilage and ammonia accumulation. This supports similar observations in tropical insect farming where substrate choice impacts both feeding behavior and hygienic rearing conditions [

24,

34]. The feed ratio experiments demonstrated that partial substitution of commercial feed with BSFL significantly improved

FCR and

ECI. Specifically, a 50% inclusion of BSFL reduced the

FCR from 4.78 to 2.25 and increased the

ECI from 32.21% to 44.38%. These results suggest improved feed assimilation, likely due to the high bioavailability of BSFL nutrients [

14,

40,

44]. However, a 75% inclusion of BSFL led to reduced final weight, consistent with prior studies warning that high-fat insect meals may result in nutritional imbalances or impaired gut physiology [

39,

42].

When evaluating full feed recipes formulated using the Pearson’s square method, Recipe 2, which included 20.61% BSFL and 17.86% commercial feed, emerged as the most promising formulation. It supported the highest yield in both juvenile (99.89%) and adult crickets (91.00%) while also offering a 33.25% cost reduction compared to commercial feed. The nutritional profile of Recipe 2, particularly its elevated protein (24.9%) and fat (8.3%) content, appears well-aligned with crickets’ metabolic demands during growth and reproduction [

41,

43]. These findings validate the use of BSFL as a cost-saving and performance-enhancing component in insect feed. Age-dependent feeding behavior was also evident. Juvenile crickets consumed more feed per unit weight gain than adults, reflecting their higher anabolic demand for tissue growth. Similar trends were observed by Halloran et al. [

39] and Kipkoech et al. [

20], who noted that feed efficiency typically peaks in younger crickets and declines post-maturity. Importantly, environmental conditions—specifically high ambient temperatures during the trial (35–40°C)—likely impacted growth, particularly in adult crickets. Elevated temperatures can induce heat stress, reduce feeding behavior, and increase mortality rates [

10,

34], which may explain the near-zero or negative net weight gains in certain trials.

Overall, this research contributes to the growing body of literature on sustainable insect farming by demonstrating that locally formulated feeds incorporating BSFL can achieve comparable or superior performance to commercial feeds while significantly reducing production costs. These findings have important implications for smallholder farmers and agripreneurs in resource-limited settings, particularly in tropical regions such as Southeast Asia.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility of formulating cost-effective and nutritionally balanced cricket feed using locally available ingredients, particularly Black Soldier Fly Larvae (BSFL), as a substitute for expensive commercial feed. The feed preference trials confirmed BSFL as the most palatable ingredient, while performance evaluations showed that a 50% inclusion of BSFL significantly improved feed conversion ratio (FCR) and efficiency of conversion of ingested food (ECI), without compromising cricket yield. Among the tested formulations, Recipe 2—containing 20.61% BSFL and 17.86% commercial feed—emerged as the most efficient and economical, achieving the highest growth yields for both juvenile and adult crickets. This formulation not only met the nutritional needs of Acheta domesticus but also reduced feed costs by over 33%, highlighting its practical utility for small-scale and semi-industrial cricket farming.

The findings reinforce the potential of BSFL-based feeds as a sustainable alternative in insect farming systems and provide a valuable reference for developing localized feed solutions that enhance economic viability while maintaining or improving production outcomes. Future research should further explore seasonal variability, reproductive performance under optimized diets, and the integration of additional agro-industrial by-products to maximize sustainability and resilience in cricket farming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition: Sopa Cansee; formal analysis, Writing – review & editing: Siripuk Suraporn; writing—original draft preparation, methodology, investigation: Nuntawat Butwong.

Funding

This research project was financially supported by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, we used ChatGPT-4o (OpenAI, 2025) to assist in reviewing related research literature. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited the content generated, and take full responsibility for the final content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wu, G.; Fanzo, J.; Miller, D.D.; Pingali, P.; Post, M.; Steiner, J.L.; Thalacker-Mercer, A.E. Production and supply of high-quality food protein for human consumption: Sustainability, challenges, and innovations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1321, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henchion, M.; Hayes, M.; Mullen, A.M.; Fenelon, M.; Tiwari, B. Future protein supply and demand: Strategies and factors influencing a sustainable equilibrium. Foods 2017, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salter, A.M.; Lopez-Viso, C. Role of novel protein sources in sustainably meeting future global requirements. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chartres, C.J.; Noble, A. Sustainable intensification: Overcoming land and water constraints on food production. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdawe, M.M. Contribution, prospects and trends of livestock production in sub-Saharan Africa: A review. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2247776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, T. Livestock-related greenhouse gas emissions: Impacts and options for policy makers. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; Global Forum for food and agriculture (GFFA). Food Systems for Our Future: Joining Forces for a Zero Hunger World, Berlin, Germany, 17-20/01/2024; FAO regional office for Europe and Central Asia: Budapest, Hungary, 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Sakadevan, K.; Nguyen, M.L. Livestock production and its impact on nutrient pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Adv. Agron. 2017, 141, 147–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, S.; Moruzzo, R.; Riccioli, F.; Paci, G. European consumers' readiness to adopt insects as food: A review. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarianos, M.; Fricke, A.; Altuntaş, H.; Baldermann, S.; Schreiner, M.; Schlüter, O.K. Potential of house crickets Acheta domesticus L. (Orthoptera: Gryllidae) as a novel food source for integration in a co-cultivation system. Future Foods 2024, 9, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Cassi, X.; Supeanu, A.; Vaga, M.; Jansson, A.; Boqvist, S.; Vagsholm, I. The house cricket (Acheta domesticus) as a novel food: A risk profile. J. Insects Food Feed 2019, 5, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magara, H.J.; Niassy, S.; Ayieko, M.A.; Mukundamago, M.; Egonyu, J.P.; Tanga, C.M.; Ekesi, S. Edible crickets (Orthoptera) around the world: Distribution, nutritional value, and other benefits—A review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 7, 537915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril, S.; Pinzón, M.; Hernández-Carrión, M.; Sanchez-Camargo, A.D.P. Edible insects in Latin America: A sustainable alternative for our food security. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 904812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Huis, A.; Van Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantomme, P. Edible Insects: Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security; FAO Forestry Paper No. 171; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gahukar, R.T. Edible insects farming: Efficiency and impact on family livelihood, food security, and environment compared with livestock and crops. In Insects as Sustainable Food Ingredients; Dossey, A.T., Morales-Ramos, J.A., Rojas, M.G., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 85–111. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran, A.; Megido, R.C.; Oloo, J.; Weigel, T.; Nsevolo, P.; Francis, F. Comparative aspects of cricket farming in Thailand, Cambodia, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Kenya. J. Insects Food Feed 2018, 4, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanboonsong, Y.; Jamjanya, T.; Durst, P.B. Six-Legged Livestock: Edible Insect Farming, Collection, and Marketing in Thailand; FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran, A.; Roos, N.; Hanboonsong, Y. Cricket farming as a livelihood strategy in Thailand. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadawong, C. Strategic Planning of the Business Cricket Farm: A Case Study of a Home Cricket Farm Nong Phai Center Nong Phai Center, Muang District, Nong Bua Lamphu Province. Master’s Thesis, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kipkoech, C.; Kinyuru, J.N.; Imathiu, S.; Roos, N. Use of house cricket to address food security in Kenya: Nutrient and chitin composition of farmed crickets as influenced by age. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 12, 3189–3197. [Google Scholar]

- Reverberi, M. Edible insects: Cricket farming and processing as an emerging market. J. Insects Food Feed 2020, 6, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A. Insects as food and feed, a new emerging agricultural sector: A review. J. Insects Food Feed 2020, 6, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafir, M.; Abbas, M.; Irfan, M.; Zia-Ur-Rehman, M. Greenhouse gases emission from edible insect species. In Advances and Technology Development in Greenhouse Gases: Emission, Capture and Conversion; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 205–225. [Google Scholar]

- Cansee, S.; Suraporn, S.; Pattiya, A.; Saenkham, S. The effects of temperature, moisture content, and cricket frass on gas emissions and survival rates in cricket farming at Honghee Village, Kalasin Province, Thailand. Eng. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 51, 588–596. [Google Scholar]

- Van Huis, A. Potential of insects as food and feed in assuring food security. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2012, 58, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, S.; Zurbrügg, C.; Gutiérrez, F.R.; Nguyen, D.H.; Morel, A.; Koottatep, T.; Tockner, K. Black soldier fly larvae for organic waste treatment—prospects and constraints. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Waste Management, Khulna, Bangladesh, 13–15 February 2011; Proc. Waste Safe 2011, 2, 13–15.

- Newton, L.; Sheppard, D.C.; Watson, D.W.; Burtle, G.; Dove, R. Using the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens, as a value-added tool for the management of swine manure. J. Anim. Poultry Waste Manag. 2005, 11, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Muros, M.J.; Barroso, F.G.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Insect meal as renewable source of food for animal feeding: a review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.R.; Popa, R. Enhanced ammonia content in compost leachate processed by black soldier fly larvae. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 166, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalová, M.; Borkovcová, M. Voracious larvae Hermetia illucens and treatment of selected types of biodegradable waste. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendelianae Brun. 2013, 61, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmawati, R.; Buchori, D.; Hidayat, P.; Hem, S.; Fahmi, M.R. Development and nutritional content of Hermetia illucens larvae on palm kernel meal. J. Entomol. Indones. 2010, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.C.; Newton, G.L.; Thompson, S.A.; Savage, S. A value-added manure management system using the black soldier fly. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 85, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendra, K.C.; Olivier, R.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Jha, R.; Khanal, S.K. Bioconversion of organic wastes into biodiesel and animal feed via insect farming. Renew. Energy 2016, 98, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miech, P.; Berggren, Å.; Lindberg, J.E.; Chhay, T. Growth and survival of house crickets (Acheta domesticus) fed weeds, organic waste, and commercial feedstuffs in Cambodia. Insects 2020, 11, 626. [Google Scholar]

- Ravzanaadii, N.; Kim, S.-H.; Choi, W.H.; Hong, S.-J.; Kim, N.J. Nutritional value of mealworm, Tenebrio molitor as food source. Int. J. Ind. Entomol. 2012, 25, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaemkong, S.; Jaipong, P.; Gothom, P.; Sreela-or, C.; Tharungsri, P.; Mesangsin, P.; Bang-Iam, N. The effect of different commercial diets on plant nutrient contents in feces of Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus) cricket. Khon Kaen Agric. J. (In Thai). 2022, Suppl. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sommai, S.; Ampapon, T.; Mapato, C.; Totakul, P.; Viennasay, B.; Matra, M.; Wanapat, M. Replacing soybean meal with yeast-fermented cassava pulp on feed intake, nutrient digestibilities, rumen microorganism, fermentation, and N-balance in Thai native beef cattle. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 2035–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamjanya, T.; Thavornanukulkit, C. Cultivation of crickets for human food. In Proceedings of the 3rd Symposium on Genetic Conservation Plants Due to His Majesty’s Initiative: Thai Resources All Things Are Intertwined, (In Thai). Sikhio District, Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand; 2005; pp. 428–432. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran, A.; Roos, N.; Eilenberg, J.; Cerutti, A.; Bruun, S. Life cycle assessment of edible insects for food protein: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpold, B.A.; Schlüter, O.K. Potential and challenges of insects as an innovative source for food and feed production. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkusz, A. Edible insects versus meat—nutritional comparison: knowledge of their composition is the key to good health. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, G.; Veenenbos, M.E.; Van Zanten, H.H.E.; Meijer, N.P.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; van Loon, J.J.A. Efficiency of organic stream conversion by black soldier fly larvae: a review of the scientific literature. J. Insects Food Feed 2018, 4 (Suppl. 1), S44–S44. [Google Scholar]

- Köhler, R.; Kariuki, L.; Lambert, C.; Biesalski, H.K. Protein, amino acid and mineral composition of some edible insects from Thailand. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2019, 22, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, T.; Van Duinkerken, G.; van Huis, A.; Lakemond, C.M.M.; Ottevanger, E.; Bosch, G.; Van Boekel, T. Insects as a sustainable feed ingredient in pig and poultry diets: a feasibility study. Wageningen UR Livest. Res. 2012; Report 638. [Google Scholar]

- Salomone, R.; Saija, G.; Mondello, G.; Giannetto, A.; Fasulo, S.; Savastano, D. Environmental impact of food waste bioconversion by insects: application of life cycle assessment to process using Hermetia illucens. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonincx, D.G.; de Boer, I.J. Environmental impact of the production of mealworms as a protein source for humans—a life cycle assessment. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Rajan, D.K.; Muralisankar, T.; Ganesan, A.R.; Sathishkumar, P.; Revathi, N. Use of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) larvae meal in aquafeeds for a sustainable aquaculture industry: a review of past and future needs. Aquaculture 2022, 553, 738095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonincx, D.G.; van Itterbeeck, J.; Heetkamp, M.J.; van den Brand, H.; van Loon, J.J.; van Huis, A. An exploration on greenhouse gas and ammonia production by insect species suitable for animal or human consumption. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).