1. Introduction

Synthetic agrochemicals started to be largely used after World War II to increase crop productivity and overcome human malnutrition (Gill et al., 2018). Among all herbicides, glyphosate (N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine) remains one of the most widely used to control unwanted weeds and algae (Duke, 2018). It is a non-selective, post-emergent, and systemic herbicide that was first commercialized by Monsanto in 1974 (Richmond, 2018). It is commonly sold as salt and mixed with surfactants such as polyoxymethylene amine (POEA), as in the popular commercial product RoundUp®, to increase uptake and translocation into the growing parts of the plants (Gill et al., 2018). Besides the controversy around the risk of glyphosate and its surfactants being environmental and health hazards, in 2023 the European Commission renewed for 10 more years the authorization of its use, with some restrictions (EFSA, 2015; IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans, 2017; Torretta et al., 2018; Madani and Carpenter, 2022; Walsh et al., 2023; Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/2660 of 28 November 2023). In Portugal, Decree-Law No. 35/2017 of March 24 prohibits the application of herbicides in some urban areas, such as gardens and parks, schools and hospitals. Nonetheless, glyphosate-based herbicides are extensively used in orange and olive groves and greenhouse cultivation in southern Portugal. Although no public information is available regarding the amount of glyphosate used by the agricultural sector in the EU, Antier et al., (2020) found that, in 2017, more than 50% of the total herbicide formulations sold in Portugal contained glyphosate.

Glyphosate acts through the inhibition of the chloroplastic enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS), which is an intermediate of the aromatic amino acid synthesis in the shikimate pathway (Duke et al., 2008; Gill et al., 2018). Consequently, it causes a decline in protein synthesis and blocks plant growth, which is usually followed by chlorosis and necrosis within two to four days after application of the herbicide (Solomon and Thompson, 2003). Once glyphosate reaches the soil, it normally gets immobilized by absorption or binds to soil particles. Still, some free molecules can be transformed into aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) and CO2 by microbial metabolization (reviewed by Vereecken, 2005). Furthermore, episodes of runoff may transport this herbicide to groundwater, surface water and aquatic environments (Sanchís et al., 2012; Battaglin et al., 2014; Ruiz-Toledo et al., 2014; Maqueda et al., 2017; Rendón-von Osten and Dzul-Caamal, 2017; Carretta et al., 2022), and potentially end up in seawater (Skeff et al., 2015). While the presence of glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA in European freshwater environments has been extensively reported (Pesce et al., 2008; Villeneuve et al., 2011; Coupe et al., 2012; Daouk et al., 2013; Skeff et al., 2015; Pupke et al., 2016; Poiger et al., 2017; Huntscha et al., 2018), only a few studies measured the presence of glyphosate in the marine environment, ranging from 0.42 ng L-1 to 1.2 μg L-1 in European seawaters (Burgeot et al., 2008; Wirth et al., 2021; Feltracco et al.; 2022). Glyphosate was reported to be persistent in seawater for 47 to 315 days (Mercurio et al., 2014).

The proximity of agricultural land to coastal regions can facilitate the influx of nutrients and herbicides into aquatic environments, thereby generating water contamination in the adjacent coastal systems. The Ria Formosa is a barrier lagoon located in southern Portugal, extending to approximately 55 km in length and 6 km in width (Newton and Mudge, 2003). The lagoon hosts 99 % of total seagrass meadows of the Algarve region (Ito et al., 2025). Owing to its seagrass meadows, which provide a plethora of ecosystem services and high-value economic benefits (de los Santos et al., 2020), the lagoon plays a pivotal role in the region’s ecosystem, serving as a vital habitat, breeding ground, and nursery for numerous species (Andrade, 1985; Newton et al., 2018; Aníbal et al., 2019; Erzini et al., 2022), which justifies its status as a National Park, Natural Reserve, Natura 2000 and Ramsar site. Seagrasses are endangered worldwide (Waycott et al., 2009; Dunic et al., 2021) and their protection is a priority in marine ecosystem conservation. Among the three seagrass species of Ria Formosa, the ubiquitous Zostera marina, classified as a Vulnerable species in the Red List of the Vascular Flora of Continental Portugal (Carapeto et al., 2020), is one of the most endangered, with reported decreases since 2010 (Cunha et al., 2013; Ito et al., 2025). The lagoon is subjected to various anthropogenic pressures, including urbanization, livestock husbandry, and intensive agriculture and aquaculture (Newton et al., 2003; Guimarães et al., 2012; Casal-Porras et al., 2022). These activities introduce a variety of sources of pollution, including sewage discharge, aquaculture effluents and agricultural runoff (Newton et al., 2003; Cravo et al., 2015; Newton et al., 2020; Cravo et al., 2022) that may be a threat to seagrass meadows. Due to the limited hydrodynamic exchange with the Atlantic Ocean, only 50 to 70% of the lagoon’s water is renewed daily (Tett et al., 2003), consequently enhancing the potential for contaminant accumulation.

A review of the literature on macroalgae’s exposure to glyphosate reveals several effects, including alterations in growth and biomass, gene expression, photosystem II (PSII) function, reductions in pigment levels, increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) content and oxidative stress (Romero et al., 2011; Choi et al., 2012; Pang et al., 2012; Kittle and McDermid, 2016; Falace et al., 2018; Iummato et al., 2019; Felline et al., 2019; Gerdol et al., 2020; de Campos Oliveira et al., 2021; Cruz de Carvalho et al., 2022; Qu et al., 2022). Among the few studies on seagrasses, it was reported that exposure to glyphosate concentrations higher than a few mg L-1 induces similar adverse effects with enhanced consequences as concentration increases (Ralph, 2000; Nielsen and Dahllof, 2007; Castro et al., 2015; Kittle and McDermid, 2016; van Wyk et al., 2022; Silvera et al., 2024; Fox et al., 2024). Nonetheless, Ralph (2000) observed no direct effect of glyphosate on the photosynthetic efficiency of Halophila ovalis, even at high concentrations (up to 100 mg L-1), which suggests species-dependent responses to glyphosate exposure. Given the fundamental ecological importance of seagrass ecosystems as coastal engineers and biodiversity hotspots (Denny et al., 2021; Erzini et al., 2022), any adverse effects can have far-reaching consequences. The potential harm to seagrasses may disrupt the ecological equilibrium of these habitats, with repercussions that extend throughout the associated biota. Such disturbances can result in shifts in species composition, which in turn can impact the abundance and distribution of species within these habitats.

In this study, we investigated the impact of three different concentrations of a commonly sold glyphosate formulation on growth, photosynthetic activity, photosynthetic pigments content and adenylate compounds content of Z. marina in a controlled, closed-system, mesocosm experiment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

Z. marina individuals with at least three shoots were collected in Ria Formosa coastal lagoon near Culatra island (South Portugal, 37°N, 7°49’W) on March 7th, 2019. Following collection, plants were cleaned from epiphytes and transported in dark containers filled with local water collected near Ramalhete Field Station (CCMAR, University of Algarve). On the following day, seagrasses were distributed and planted in 20 tanks (26 shoots per tank), each filled with 20 liters of artificial seawater treated by reverse osmosis to remove potential glyphosate residues (reverse osmosis water with added Coral Pro Salt, Red Sea, to reach a salinity of 35 ppt). Plants were acclimated for 6 days at 13.76 ± 0.28°C, 8.35 ± 0.03 pH, with a light intensity of 59.55 ± 1.28 μmol photons m-2 s-1 and a photoperiod of 12-12 light-dark cycle.

Subsequently, five aquaria were randomly assigned to each of the four treatments (control and three herbicide concentrations). Three different concentrations of glyphosate were obtained by diluting a commonly sold herbicide (active substance: glyphosate potassium salt 35.5%, 360 g glyphosate L-1): (i) 0.165 mg L-1, corresponding to the highest concentration of glyphosate found in streams and rivers in France in 2003-2004 (Villeneuve et al., 2011); (ii) 51 mg L-1, an intermediate concentration and (iii) 5100 mg L-1, which was, by the time this work was done, one of the lowest concentrations freely sold in the market for direct application (i.e., without dilution). The control aquaria contained only artificial seawater (0 mg glyphosate L-1). All aquaria were maintained in a closed circuit with aeration. At the end of the experiment, seawater contaminated with herbicide was disposed of as chemical waste through the appropriate laboratory channels.

2.2. Water Physical-Chemical Parameters

During the entire experiment, both in the acclimation and the experimental periods, water physical-chemical conditions were measured daily using an Orion StarTM A221 pH Portable Meter (Thermo ScientificTM) for pH and temperature and an STX-3 refractometer (VEE GEE Scientific) for salinity.

2.3. Sampling Procedures

During the mesocosm experiment, samples from each treatment (n=5) were collected on different days because of the sudden and visible effect of the herbicide at the higher concentration: one day after exposure for the higher concentration, 4 days for the intermediate and lower concentrations, and 5 days for control condition. Leaves were cleaned from epiphytes, rinsed in distilled water, blotted dry, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until analysis.

2.4. Growth Rate

The growth of the plants was evaluated using the punching method, as described by Worm and Reusch (2000). One day before the introduction of glyphosate into the water, the plants were identified by marking a specific spot on the lower outer leaf sheath using a syringe needle. The growth of each leaf was quantified by measuring the distance from the mark on the oldest leaf, designated as the reference point, to one of the younger leaves. Subsequently, the total growth of each plant was divided by the number of days of treatment (5 for the control, 4 for the intermediate and lower concentration) to obtain the growth rate (cm day-1). The growth calculation for plants exposed to the higher glyphosate concentration was omitted due to their mortality within a single day of exposure.

2.5. Photosynthetic Efficiency

A Diving-PAM (Underwater Chlorophyll Fluorometer Pulse-Amplitude-Modulated (PAM), Walz, Germany) was employed to assess photosynthetic efficiency, to measure the effective photosynthetic efficiency of PSII in the light (effective quantum yield, ΔF/Fm’) and the potential photosynthetic efficiency following a 30 min dark-acclimation period (maximum quantum yield, Fv/Fm). All fluorescence measurements were conducted on the second or third leaves in the middle of the adaxial surface. Dark-acclimation leaf clips were used to ensure a constant distance between the optic fiber tip and the leaf sample. The effective quantum yield was determined using the same methodology but omitting the dark acclimation period. Fluorescence measurements were conducted daily throughout the experiment. The same two plants per aquarium, previously marked and identified, were used for all measurements.

2.6. Photosynthesis-Irradiance (P-I) Curves

Photosynthesis-irradiance (P-I) curves were made on the same days the tissue samples for biochemical analysis were collected. Segments of the 2nd or 3rd youngest leaf of a shoot taken from each tank were incubated in chambers with 0.07 L of the same water in which plants were growing. Incubation water was continuously homogenized by a magnetic stirrer, and the temperature was maintained at 14 °C (approx. water temperature in the aquaria) by a thermostatic circulator (Julabo F10) (Silva et al., 2013). The light was provided by a system of LED lamps (LEXMAN, 20W-2452 Lumens). Each chamber was exposed to 10 increasing light intensities (7 ± 0.71; 19.4 ± 1.52; 35 ± 2.55; 69 ± 2.55; 119.8 ± 9.47; 223.6 ± 7.09; 310.6 ± 11.06; 450.6 ± 10.24; 936.2 ± 20.73; 1325.4 ± 39.18 μmol quanta m-2 s-1) by using a series of neutral density filters of variable transmittance. Each light intensity was maintained between 5 and 10 min, depending on the plants’ oxygen production rate. Oxygen concentration was read at the beginning and the end of each light intensity exposure using a Microx 4 optical sensor (PreSens, Germany). Dark respiration was measured in the same leaf segments at the beginning and the end of each P-I curve after a dark period of ~30 minutes. It was not possible to do P-I curves on plants exposed to the higher herbicide concentration (5100 mg L-1) because of the 100% mortality after 24 hours of exposure.

After photosynthesis (P) and dark-respiration (DR) measurements, each leaf segment was dried at 60 °C for 48h for dry weight measurement.

Photosynthetic/dark-respiration rates were calculated as follows:

where: P/DR – Photosynthetic/dark-respiration rate (μmolO2 gDW-1 h-1); [O2]f – final oxygen concentration (µmol/L); [O2]i initial oxygen concentration (µmol L-1); t – incubation time (min); v – volume of water (L); DW – sample dry weight (g).

P-I curves were fitted with the Jassby and Platt (1976) equation model using SigmaPlot (Copyright© 2008 Systat Software, Inc. Germany, Sigmaplot for Windows Version 11.0) to derive Pmax (maximal photosynthetic rate) and α (photosynthetic quantum efficiency) parameters. The standard error was estimated, and the saturation irradiance (Ik) was calculated as the ratio between Pmax and α for each treatment, incorporating error propagation.

2.7. Photosynthetic Pigments

Following sample collection, leaf tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until analysis. Chlorophylls and carotenoids were quantified in approximately 200 mg (fresh weight) leaf tissue. Leaf tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen with sodium ascorbate (C6H7NaO6) and immediately extracted in 5 mL of 100% acetone neutralized with calcium carbonate (CaCO3) (Abadía and Abadía, 1993); the extract (5 mL) was then sequentially filtered through 0.45 μL and 0.22 μL PTFE/nylon filters. Chlorophylls a and b were quantified spectrophotometrically after reading the extracts at 644.8 nm (A644.8) and 661.6 nm (A661.6) (Beckman-Coulter DU 650 spectrophotometer, Brea CA, USA).

Quantification was performed using the equations of Lichtenthaler and Buschmann (2001):

Chlorophyll a: Chl a (μg mL-1) = 11.24 A661.6 - 2.04 A644.8

Chlorophyll b: Chl b (μg mL-1) = 20.13 A644.8 – 4.19 A661.6

Carotenoids (antheraxanthin, β-carotene, lutein, lutein epoxide, neoxanthin, violaxanthin, and zeaxanthin) were separated and quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (de las Rivas et al., 1989; Larbi et al., 2004; Silva et al. 2013). HPLC analysis was performed in an Alliance Waters 2695 separation module (Milford MA, USA), with a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector and a Phenomenex Synergi™ 4 µm Hydro-RP 80 Å, LC Column 150 x 4.6 mm, Ea. During the process, extracts were maintained at 5°C, while the column was kept at 25°C. Separation was performed by combining eluents in Isocratic mode, sequentially eluted by eluent R1 (acetonitrile, methanol and triethylamine, TEA) and R2 (acetonitrile, methanol, Milli-Q water, acetate ethyl and TEA), previously filtered and sonicated. Injection volume was set to 20 μL, and peak areas were monitored at 450 nm. Pigment concentrations were calculated through calibration curves of standards at known concentrations (pure pigments obtained from CaroteneNature, Lupsingen, Switzerland). The xanthophyll cycle epoxidation state was calculated as described by Silva et al. (2013).

2.8. Adenylate Compounds (ATP, ADP and AMP) and Energy Charge (AEC)

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and adenosine monophosphate (AMP) were extracted and quantified following a protocol adapted from Coolen et al. (2008) and Liu et al. (2006). Approximately 500 mg (fresh weight) of leaf tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen. Adenosine phosphates were extracted in 10 mL of 0.6 M perchloric acid (HClO4). The extract was homogenized and then placed in a water bath at 100 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, the extracts were cooled in ice for 1 min and centrifuged at 4600xg at 4 °C for 30 min (Thermo Scientific, Heraeus Megafuge 16 Centrifuge). Extracts’ pH was adjusted to 6.5 - 6.8 with potassium hydroxide (KOH) 1 M, and the final volume was quantified. The extracts were then allowed to stand for 30 min in an ice bath to enable potassium perchlorate precipitation. The supernatants were filtered through 0.45 μm and 0.22 μm nylon filters and transferred to micro vials. Different concentrations of AMP, ADP and ATP (Sigma Aldrich) were used as standard to calibrate the HPLC. Adenylate compounds were quantified by isocratic HPLC analysis (Coolen et al. 2008) in an Alliance Waters 2695 separation module (Milford MA, USA), with a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector and a Phenomenex Kinetex® 2.6 µm HILIC 100 Å, LC Column 30 x 2.1 mm, Ea. Extracted ATPs were eluted in potassium phosphate buffer, and peaks were detected at 254 nm.

Adenylate energy charge (AEC) was calculated according to Atkinson and Walton (1967) using the following equation:

2.9. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were made using Sigmaplot (Copyright© 2008 Systat Software, Inc. Germany, Sigmaplot for Windows Version 11.0) and R Studio (R Studio for Windows Version 4.3.3, R Core Team, 2014). Shapiro-Wilk and Brown-Forsythe tests were performed to confirm normality distribution and equal variance, respectively. One-way ANOVAs were conducted to test the significant effects of the different treatments. Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc tests were used to reveal significant differences among treatments. In the case of heteroscedasticity, a Kruskal-Wallis test (ANOVA on ranks) was performed, followed by a Dunn-Bonferroni test to reveal differences among treatments. The significance level was set at p<0.05 for all statistical tests.

3. Results

3.1. Water Physical-Chemical Parameters

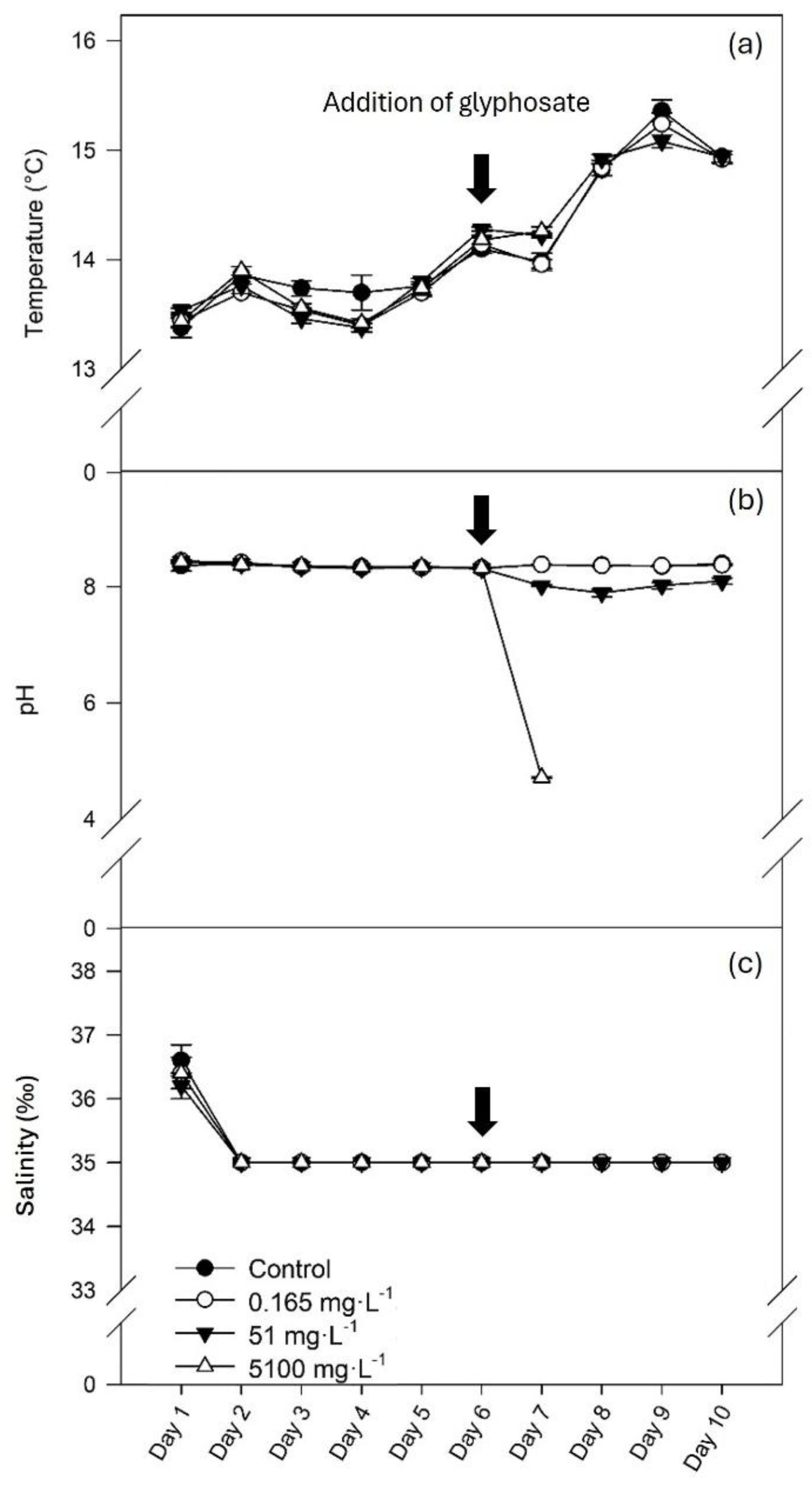

The temperature in the aquaria ranged between 13.38 and 15.36 °C (

Figure 1, a). During the acclimation period (days 1 to 6), pH was stable at 8.35 ± 0.003. Following glyphosate addition (day 6), the pH of water with the intermediate and the higher concentrations of glyphosate decreased to 8.01 ± 0.04 and 4.72 ± 0.02, respectively (

Figure 1, b). Salinity was 36.40 ± 0.08 ‰ during the first day of acclimation due to water preparation and adjustments and then stabilized at 35 ‰ during the rest of the experiment (

Figure 1, c).

3.2. Photosynthetic Performance

The maximum quantum yield (F

v/F

m) showed similar values in all aquaria during the acclimation period (0.80 ± 0.001;

Figure 2, a). After adding glyphosate, control plants and plants exposed to the lower herbicide concentration continued to show values around 0.8, while those exposed to the higher concentration (5100 mg L

-1) faced a rapid decrease and reached zero after one day.

Z. marina plants treated with the intermediate concentration of glyphosate (51 mg L

-1) displayed a continuous decrease of F

v/F

m until reaching 0.20 ± 0.1 after 4 days (

Figure 2, a). The effective quantum yield (ΔF/F

m’) was also stable throughout the acclimation period, averaging 0.74 ± 0.01 (

Figure 2, b) and, as for F

v/F

m, the control plants and the plants exposed to the lower concentration of herbicide showed stable values during the experimental period. In plants exposed to the intermediate and higher concentrations of glyphosate (51 and 5100 mg L

-1), ΔF/F

m’ decreased to 0.35 ± 0.09 and 0 one day after adding glyphosate, respectively.

3.3. Growth Rate

The foliar growth rate of

Z. marina exposed to 51 mg L

-1 of glyphosate was significantly lower than that of control plants and plants exposed to the lower concentration of glyphosate (

Figure 3).

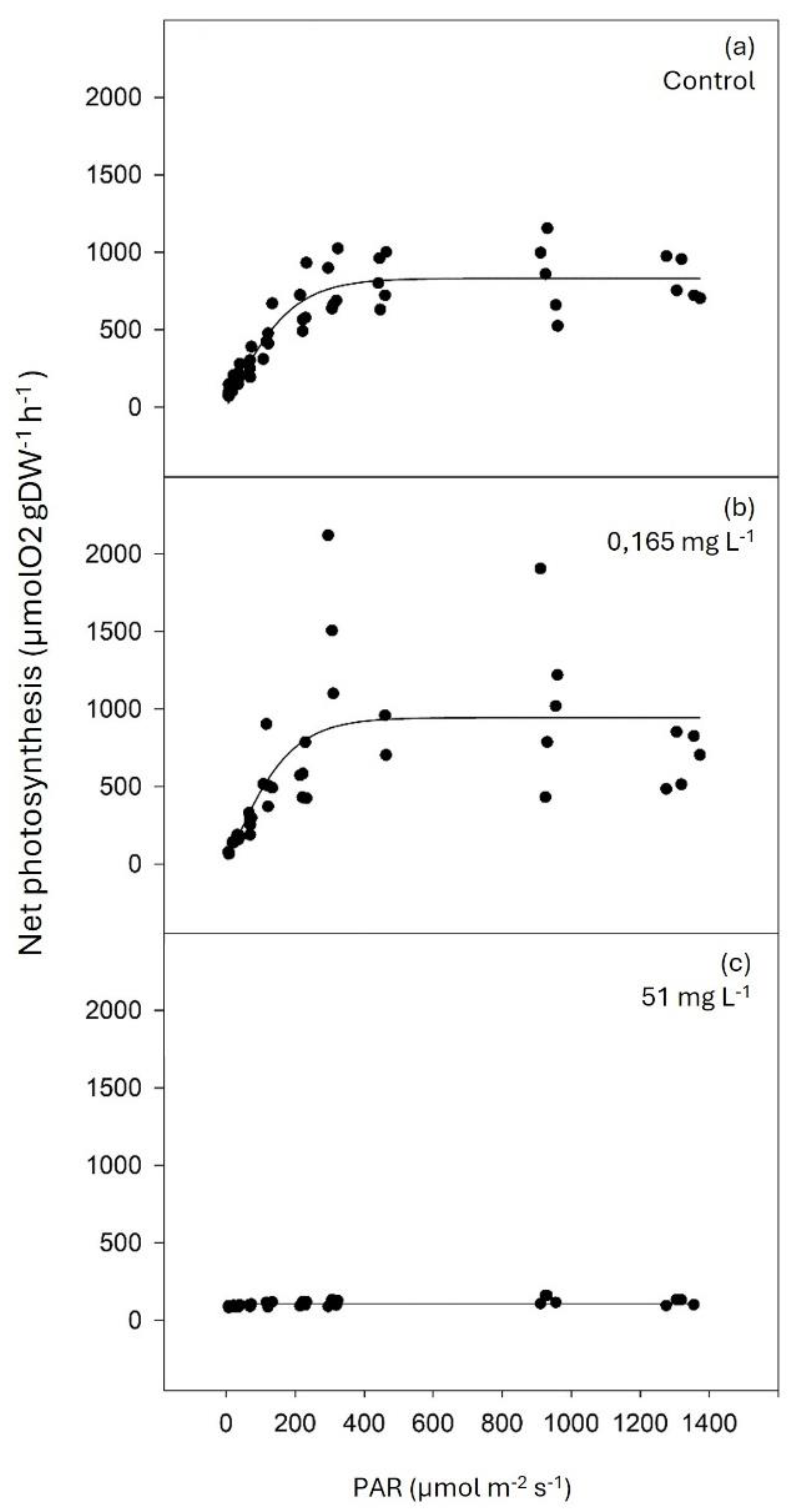

3.4. Photosynthetic Activity

There was a tendency for dark respiration to increase with glyphosate concentration (

Table 1). The maximum photosynthetic rate (P

max) and minimum-saturation irradiance (I

k) were significantly lower in plants exposed to 51 mg L

-1 of glyphosate compared to control and plants exposed to the lower glyphosate concentration. In contrast, the photosynthetic quantum efficiency (α) showed the opposite trend (

Figure 4 and

Table 1). It was not possible to obtain a photosynthesis-irradiance (P-I) curve for the plants exposed to the higher concentration of glyphosate (5100 mg L

-1) as all individuals died in less than 24 hours of exposure.

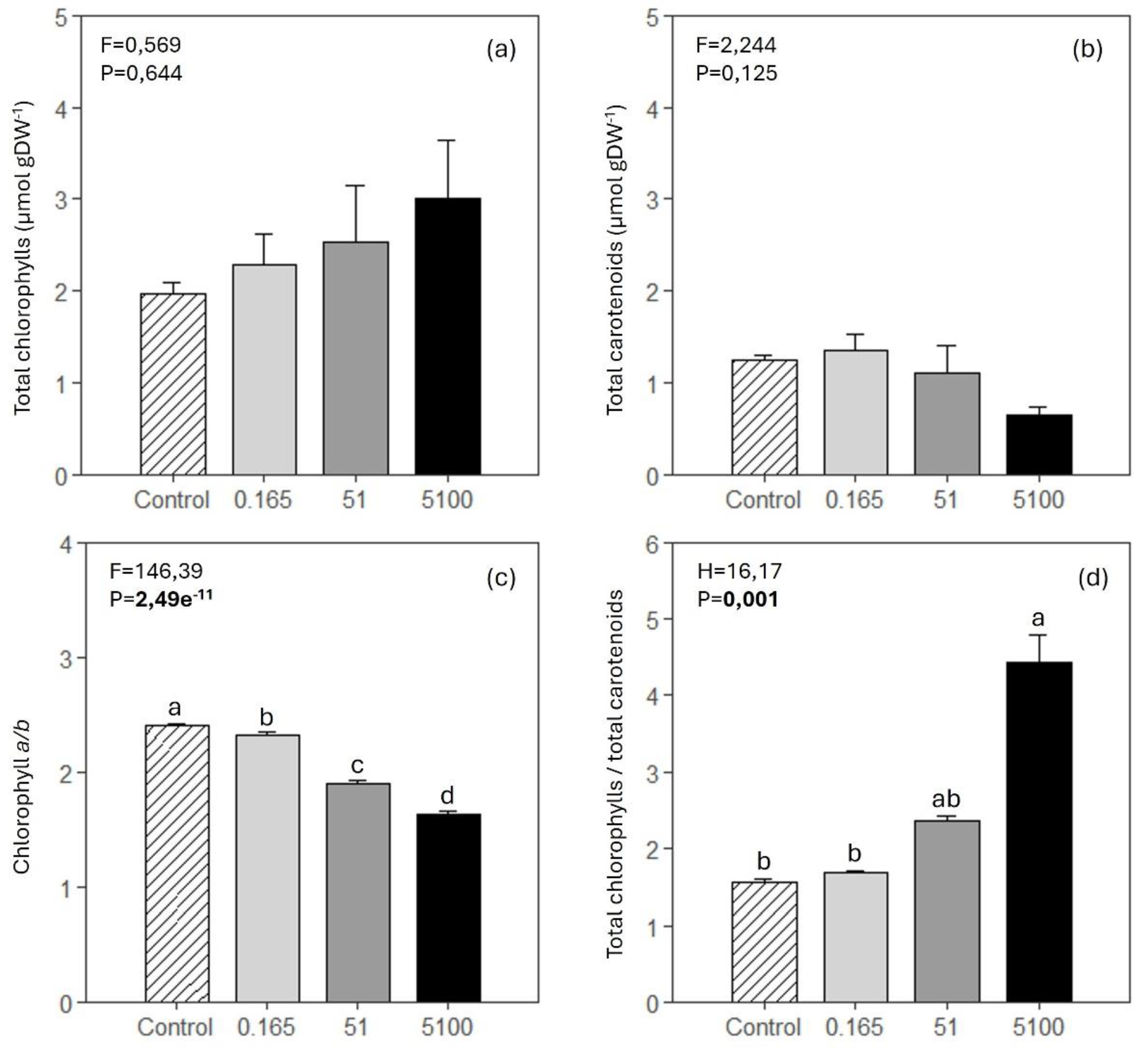

3.5. Photosynthetic Pigments

Total chlorophylls and total carotenoids did not show significant variations among treatments (

Figure 5, a and b). The chlorophyll

a/

b ratio decreased significantly with herbicide concentration (

Figure 5, c). The total chlorophylls to total carotenoids ratio was significantly higher in

Z. marina exposed to the higher glyphosate concentration than control plants and plants exposed to the lower glyphosate concentration (

Figure 5, d).

Most pigment concentrations did not vary among treatments. β-carotene and violaxanthin showed a significant reduction in plants exposed to the higher concentration of glyphosate compared to all the other treatments (

Table 2). The sum of the xanthophylls violaxanthin (V), antheraxanthin (A), and zeaxanthin (Z) was significantly lower in plants exposed to the higher concentration of glyphosate compared to all the other treatments. The de-epoxidation state (DES) index was not affected by the two lower glyphosate concentrations, but it was significantly higher in plants exposed to the higher glyphosate concentration. (V+A+Z)/Chl a+b decreased significantly in plants exposed to a glyphosate concentration of at least 51 mg L

-1.

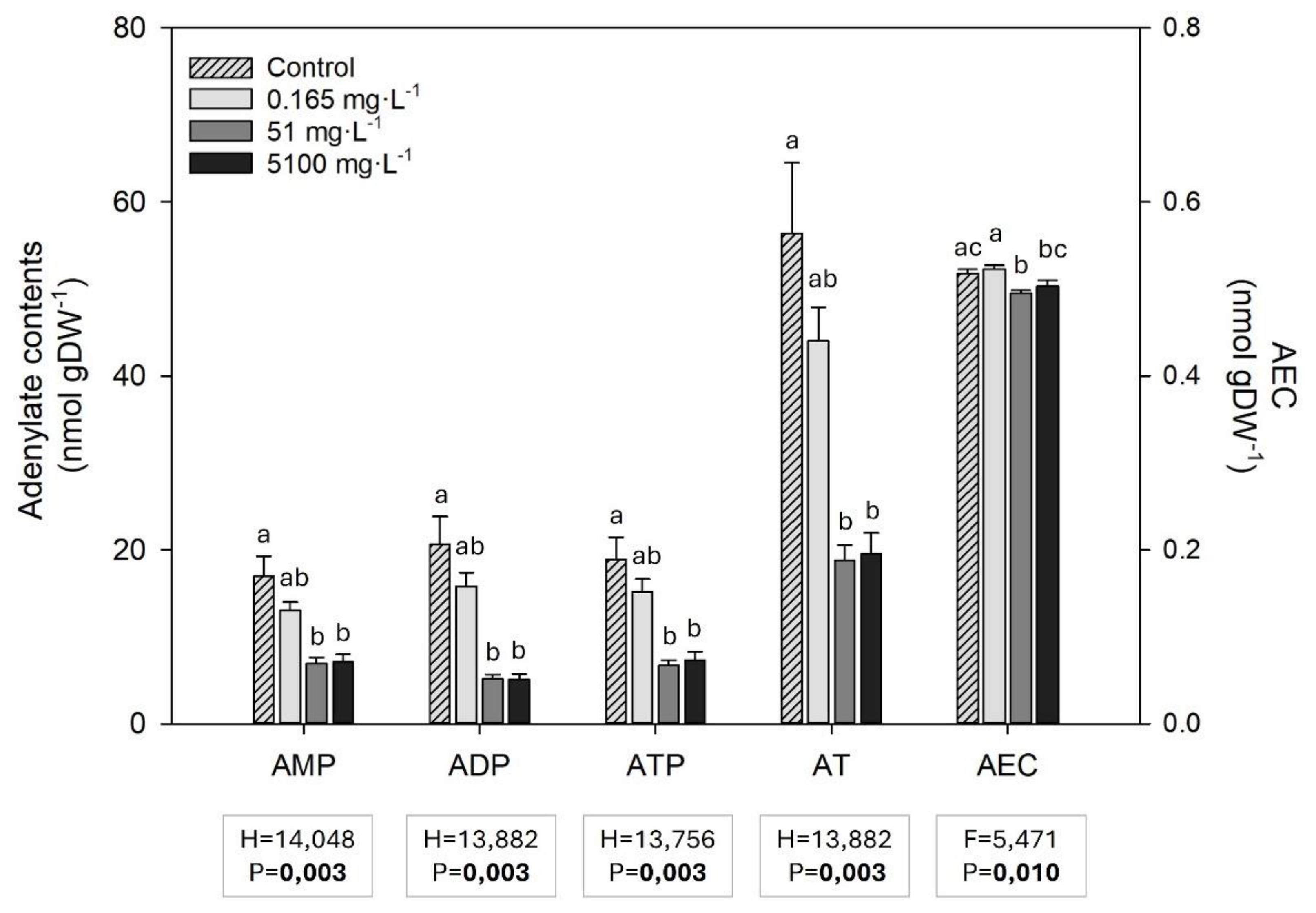

3.6. Adenylate Compounds (ATP, ADP and AMP) and Energy Charge (AEC)

Adenosine monophosphate (AMP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and, consequently, the total adenylates (AT) contents were lower in

Z. marina exposed to all glyphosate concentrations, especially 51 and 5100 mg L

-1 (

Figure 6). Although some differences in the adenylate energy charge (AEC) were observed between treatments, no concentration-dependent tendency was observed (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that exposure to high concentrations of a glyphosate-based herbicide (GBH) is lethal for Z. marina. Short-term sublethal effects were also observed at intermediate concentrations, with Z. marina showing a certain short-term tolerance to lower concentrations of GBH.

The application of the highest glyphosate concentration tested (5100 mg L-1) caused pH to drop rapidly in the water (8.35 to 4.72 in 1 day), subsequently leading to 100% mortality of Z. marina within 24 hours. Exposure to the intermediate concentration of glyphosate (51 mg L-1) also caused a pH drop (of about 0.3 in 1 day, stable for the duration of the experiment) and had severe consequences on the plant’s physiology. Even though Z. marina survived during the whole experiment, the intermediate concentration tested severely hampered photosynthetic activity, leaf growth and adenylate compounds content. Nevertheless, exposure to the lower concentration of glyphosate (0.165 mg L-1), a realistic concentration to be found in the environment, did not significantly impact the plant’s physiology for the duration of the experiment. Sudden seawater acidification, caused by the addition of the herbicide, could have impacted seagrass physiology through various mechanisms, namely increasing susceptibility to stress (Martin et al., 2020), disrupting ionic homeostasis within the plants (Bassil and Blumwald, 2014), interfering with symbiotic microbial communities (Banister et al., 2022) and altering nutrient uptake coupled with root and rhizome damage due to sediment chemistry changes (Brodersen et al., 2018). Although the adenylate energy charge (AEC) did not change according to a clear pattern, the foliar concentration of adenylate compounds decreased in plants exposed to all glyphosate concentrations tested, reflecting a decrease in the availability of metabolic energy (Atkinson, 1986).

The GBH tested in this study interfered with the photosynthetic apparatus of Z. marina at the photosystem II (PSII)’s level, as previously observed in other seagrasses and in macroalgae (Pang et al., 2012; Kittle and McDermid, 2016; Falace et al., 2018; Felline et al., 2019; Cruz de Carvalho et al., 2022). Both Fv/Fm and ΔF/Fm’ were negatively affected by glyphosate concentrations of 51 mg L-1 and above, evidencing a general decrease in the photosynthetic performance. Plants exposed to the lethal concentration of 5100 mg L-1 had both Fv/Fm and ΔF/Fm’ rapidly inhibited and dropping to 0 in less than 1 day. Such observations can be attributed to the glyphosate-induced alterations of PSII, inactivation of its reaction centers and oxidative damage (Choi et al., 2012; Smedbol et al., 2017; Gomes et al., 2017). Glyphosate is known to induce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Gomes and Juneau, 2016), whose accumulation leads to oxidative modification of PSII proteins (Pospíšil and Yamamoto, 2017) and lipid peroxidation of the thylakoid membranes (Halliwell, 1987). Damaged thylakoid membranes can compromise the energy transfer towards the reaction centers and the electron transport chain. Previous studies showed that the PSII’s integrity in marine macrophytes is negatively affected by glyphosate concentrations as low as 0.176 mg L-1 (Felline et al., 2019) and after a few minutes of exposure at higher concentrations (a few g L-1, Pang et al., 2012). The observed decreases in ΔF/Fm’, Pmax, and Ik in plants exposed to 51 mg L-1 of glyphosate reveal the decreased ability of PSII to deliver electrons to the electron transport chain (ETC), resulting in lower electron transport rate and diminished photosynthetic performance. The lower availability of ATP and NADPH, related to the lower efficiency of the ETC, has consequences for the Calvin cycle and the overall result of photosynthesis, i.e. triose phosphate synthesis and RuBP (Ribulose 1,5 Biphosphate) regeneration. The sugars produced in the Calvin cycle are the building blocks for the synthesis of molecules such as adenosine, the nucleoside constituting ATP, AMP and ADP (adenosine tri-, mono-, or diphosphate). Therefore, a decrease in sugar synthesis is likely to reduce the availability of the three adenylate compounds (ATP, AMP and ADP). Furthermore, part of the ATP generated in the chloroplast is needed for N assimilation (Ljones, 1979); this may again link to the availability of the adenylate nitrogenous compounds.

While some studies suggested the existence of a possible low-dose stimulatory growth response in the first few days of exposure to glyphosate in R. maritima (Castro et al., 2015) and Z. marina (Nielsen and Dahllöf, 2007), that was not observed in this study. Instead, the foliar growth rate was severely hampered under the intermediate concentration of GBH, meaning that the plant’s carbon metabolism was impaired, which has been reported to be an effect of the inhibition of the enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) (Orcaray et al., 2012; Gomes et al., 2014). Thus, the general reduction of energy availability in plants exposed to the intermediate concentration of GBH resulted in the decrease of the syntheses essential to plant growth, nutrient absorption, and hormonal signals disruption, slowing down all cellular energy functions and provoking a drastic reduction of foliar growth rate (Plaxton and Podestá, 2006). There was a tendency for respiration to increase with glyphosate concentration, indicating the rise of metabolic activity in response to stress caused by the inhibition of the shikimate pathway (Cedergreen and Olesen, 2010). Despite increased respiration being a stress response to maintaining energy balance, all ATP, ADP and AMP levels decreased with glyphosate concentration, especially in plants exposed to the two higher concentrations tested (51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate). Although the decrease in adenylate compounds was not statistically significant at 0.165 mg L-1 of glyphosate, given the short duration of the experiment (4 days of exposure to the GBH), we can consider that there was a strong tendency for adenylates to decrease. Moreover, we assume that exposure to lower concentrations of glyphosate may be harmful to the plants under an extended exposition time. Several causes could explain this: disruption of the Krebs cycle due to the lack of aromatic amino acids (Swanson et al., 2016), mobilization of energy resources to activate defense and repair pathways (Fuchs et al., 2021), or mitochondrial dysfunction (Gomes and Juneau, 2016; Strilbyska et al., 2022), all causing an energetic disruption that contributes to the weakening and death of the plant. Changes in energy balance as a stress response to GBH exposure have also been observed in other organisms (Menéndez-Helman et al., 2015).

There was a tendency for chlorophyll content to increase with glyphosate concentration. In contrast, some studies showed that concentrations of GBH lower than those tested in our research provoked a reduction of chlorophyll synthesis and content in many terrestrial and aquatic plants, including seagrasses (Reddy et al., 2004; Zobiole et al., 2012; Castro et al., 2015; Kittle and McDermid, 2016; Sikorski et al., 2019; Fox et al., 2024). A higher chlorophyll content might reflect the onset of a compensation mechanism in response to the lower efficiency of the reaction centers and diminished photosynthetic performance. As the herbicide concentration increased, the chlorophyll a/b ratio decreased, meaning that the proportion of chlorophyll b increased relatively to that of chlorophyll a. This is commonly related to a higher investment in light-harvesting in comparison to the capacity to input electrons in the ETC (Costa et al., 2021). A decreased chlorophyll a/b ratio can suggest changes in photosystem composition (Biswal et al., 2012), a stress response to low light (Costa et al., 2021), nutrient deficiency (e.g., nitrogen deficiency) (Cruz et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2024) and/or oxidative stress (Kasajima, 2017), as chlorophyll a may degrade faster than chlorophyll b under certain stress conditions, especially at low pH (Koca et al., 2007). On the other hand, the total chlorophylls/total carotenoids ratio increased with glyphosate concentration, indicating that the carotenoid content decreased relative to chlorophylls. This can be a consequence of the inhibition of the shikimate pathway by glyphosate, leading to the reduction of plastoquinone synthesis, which directly affects carotenoid production (Gomes et al., 2017) since plastoquinone is a co-factor of the enzymes involved in the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway (Sandmann et al., 2006). The possible decrease of plastoquinone (the PSII to cytochrome b6/f electron carrier) synthesis could have also impaired the photosynthetic ETC (Caffarri et al., 2014). Carotenoids act as antioxidants (Young and Lowe, 2001), and hence the increase in total chlorophylls/total carotenoids ratio in plants exposed to 5100 mg L-1 could indicate a lower protection against stress-induced ROS. In our experiment, plants were exposed to very low light intensity; thus, the de-epoxidation state (DES) index was always very low. Nonetheless, the decrease in violaxanthin content in Z. marina’s leaves exposed to glyphosate concentrations of 51 and 5100 mg L-1, with high significance at 5100 mg L-1, suggests the enhanced de-epoxidation of violaxanthin, supported by the increase of DES. This can be interpreted as a response mechanism to protect the photosynthetic apparatus from chemical toxicity or other factors inducing oxidative stress (Bilger and Björkman, 1990; Scarlett et al., 1999; Latowski et al., 2011).

Plants exposed to the higher concentration of glyphosate also showed a significant decrease in β-carotene. β-carotene is the precursor of zeaxanthin, a key component of the xanthophyll cycle (Bouvier et al., 1996). Lower β-carotene availability may lead to a reduced photoprotection capacity. Moreover, the impairment of the electron transport due to PSII’s malfunction decreases the acidification of the thylakoid lumen, therefore impeding the induction of the xanthophyll cycle (Gilmore, 1997), decreasing non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) and increasing the damages caused to the PSII, starting a vicious circle of cumulative negative effects (Gomes et al., 2016).

In the literature, a large discrepancy in the responses of seagrasses to GBHs can be found. Castro et al. (2015) observed a high mortality of R. maritima exposed to 50 mg L-1 of GBH after 7 days. No significant adverse impacts were observed on H. wrightii and R. maritima at a glyphosate concentration of 1 mg L-1 (Fox et al., 2024), but mortality was observed at 100 and 1000 mg L-1. Van Wyk et al. (2022) observed that Z. capensis responded to the exposure to a 0.25-2.20 mg L-1 glyphosate formulation by decreasing leaf area and above-ground biomass after 3 weeks, whereas no variation in photosynthetic pigment concentration was observed. However, in some of those studies, the herbicide’s origin and mixture composition are not disclosed, making comparisons difficult. In a study targeting Z. marina, Nielsen and Dahllöf (2007) observed that the exposure to glyphosate up to 100 μM (equivalent to 16.9 mg L-1) did not affect the relative growth rate neither the chlorophyll a/b ratio after 3 days; only at 1.69 mg L−1 a stimulation of the relative growth rate in weight was observed. Ralph (2000) observed that the exposure of H. ovalis to glyphosate (1, 10 and 100 mg L-1) did not affect fluorescence signals. Additionally, H. ovalis exposed to lower glyphosate concentrations showed lower chlorophyll content, lower chlorophyll/carotenoid ratio and higher chlorophyll a/b ratio with increasing glyphosate concentration, which is in opposition with our observations on Z. marina. Silvera et al. (2024), who is, to our knowledge, the only study reporting long-term effects, tested the effect of a GBH on H. ovalis and H. wrightii and found that 3.74 mg L-1 of sprayed GBH did not affect shoot density over a 53-days experiment. However, when exposed to a concentration of 125 mg L-1, plants’ density started to decline after 5 and 15 days, respectively. This suggests a high variability in the response of seagrasses to GBHs, which could be attributed to differences in species, experimental set-up (glyphosate concentration tested, duration of the experiment) and the form of herbicide used (glyphosate as a pure salt vs. as formulations with surfactants and adjuvants). For example, Ralph (2000) used a liquid glyphosate salt solution, which does not contain the surfactants present in many commercial formulations (1 to 10% of surfactants). Numerous studies previously showed that the synergistic effect of glyphosate with its surfactant in commercial formulations (etheralkilamine ethoxylate, also known as polyethoxylated tallow amine, POEA) or its metabolite (aminomethylphosphonic acid, AMPA) increases toxicity to aquatic organisms (e.g. Folmar et al., 1979; Mann and Bidwell, 1999; Tsui & Chu, 2003; Relyea, 2005; Lipok et al., 2010; Pérez et al., 2011; de Campos Oliveira et al., 2016; Gandhi et al., 2021; Mendes et al., 2021; Qu et al., 2022). In the commercial formulation we used in our experiment, we cannot assess whether glyphosate, POEA or the combination of both are responsible for the observed deleterious effects on Z. marina. According to previous studies, however, we can suggest that POEA might be responsible for enhancing the toxicity of glyphosate-based herbicides in seagrasses. Nielsen and Dahllöf (2007) showed the negative synergistic effect of low-concentration herbicide mixtures (glyphosate, bentazone and 4-chloro-2-methylphenoxyacetic acid, MCPA) relative to exposure to glyphosate only, suggesting that the damages on seagrass physiology and fitness may be enhanced if several herbicides are present in the environment. Other indirect effects of GBHs and associated water pH change on seagrass fitness could include impacts on the microorganisms of the sediment (microbiome), such as shifts in species composition (Newman et al., 2016). In the medium-long term, these changes can lead to negative consequences at the ecosystem level (van Bruggen et al., 2021; Ruuskanen et al., 2023).

Although no data concerning herbicide concentration in Ria Formosa coastal lagoon is currently available, it is more likely that the actual presence of glyphosate approximates the lowest concentration tested in this study (0.165 mg L-1), according to the concentrations found in other aquatic environments. If such is the case, Z. marina might not be at immediate risk in a 4-day experiment, but prolonged exposure may have harmful consequences. Further investigation is required to better understand the effects of long-term exposure and mixture toxicity and make ecologically realistic risk assessments (Bester, 2000; Diepens et al., 2017). Investigating a wider range of lower glyphosate concentrations is also required to assess this species’ minimum adverse and lethal concentrations. Care must be taken when comparing different studies, as some mention the concentration of GBH used (including water and surfactants), whereas others mention the actual glyphosate concentration. Lastly, monitoring herbicide contamination in coastal waters is crucial to understand and prevent the deterioration of water quality and potential consequences on both seagrass beds and related ecosystems.

Authors contribution statement: Conceptualization, João Silva and Isabel Barrote; Formal analysis, Alizé Deguette, Katia Pes, Bernard Costa Vasconcelos and Monya Costa; Funding acquisition, João Silva; Investigation, Katia Pes, Bernard Costa Vasconcelos and Monya Costa; Project administration, João Silva; Supervision, João Silva and Isabel Barrote; Visualization, Alizé Deguette and Katia Pes; Writing – original draft, Alizé Deguette and Katia Pes; Writing – review & editing, Bernard Costa Vasconcelos, Monya Costa, João Silva and Isabel Barrote. Alizé Deguette and Katia Pes contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This work was supported by Portuguese national funds from FCT – Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology through projects UIDB/04326/2020 (DOI:10.54499/UIDB/04326/2020) and LA/P/0101/2020 (DOI:10.54499/LA/P/0101/2020).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.D.

References

- Abadía, J.; Abadía, A. Iron and Plant Pigments. In Iron Chelation in Plants and Soil Microorganisms; Barton, L.L., Hemming, B., Eds.; Academic Press: 1993; pp. 327–343. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J. P. Aspectos Geomorfológicos, Ecológicos e Socioeconómicos da Ria Formosa, 91 (Faro: Universidade do Algarve, 1985).

- Aníbal, J. , Gomes, A., Mendes, I. & Moura, D. (eds) (2019). Ria Formosa: Challenges of a Coastal Lagoon in a Changing Environment, 1st Edn. University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal. ISBN 978-989-8859-72-3.

- Antier, C.; Kudsk, P.; Reboud, X.; Ulber, L.; Baret, P.V.; Messéan, A. Glyphosate Use in the European Agricultural Sector and a Framework for Its Further Monitoring. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, D.E.; Walton, G.M. Adenosine Triphosphate Conservation in Metabolic Regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1967, 242, 3239–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, D.E. Energy charge of the adenylate pool as a regulatory parameter. Interaction with feedback modifiers. Biochemistry 1968, 7, 4030–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, R.B.; Schwarz, M.T.; Fine, M.; Ritchie, K.B.; Muller, E.M. Instability and Stasis Among the Microbiome of Seagrass Leaves, Roots and Rhizomes, and Nearby Sediments Within a Natural pH Gradient. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 84, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassil, E.; Blumwald, E. The ins and outs of intracellular ion homeostasis: NHX-type cation/H + transporters. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglin, W.A.; Meyer, M.T.; Kuivila, K.M.; Dietze, J.E. Glyphosate and Its Degradation Product AMPA Occur Frequently and Widely in U.S. Soils, Surface Water, Groundwater, and Precipitation. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2014, 50, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, K. Effects of pesticides on seagrass beds. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2000, 54, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilger, W.; Björkman, O. Role of the xanthophyll cycle in photoprotection elucidated by measurements of light-induced absorbance changes, fluorescence and photosynthesis in leaves of Hedera canariensis. Photosynth. Res. 1990, 25, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, A.K.; Pattanayak, G.K.; Pandey, S.S.; Leelavathi, S.; Reddy, V.S.; Govindjee; Tripathy, B. C. Light Intensity-Dependent Modulation of Chlorophyll b Biosynthesis and Photosynthesis by Overexpression of Chlorophyllide a Oxygenase in Tobacco. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvier, F.; D'Harlingue, A.; Hugueney, P.; Marin, E.; Marion-Poll, A.; Camara, B. Xanthophyll Biosynthesis. Cloning, expression, functional reconstitution, and regulation of beta -cyclohexenyl carotenoid epoxidase from pepper (Capsicum annuum). J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 28861–28867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, K.E.; Kühl, M.; Nielsen, D.A.; Pedersen, O.; Larkum, A.W.D. Rhizome, root/sediment interactions, aerenchyma and internal pressure changes in seagrasses. Seagrasses of Australia: Structure, Ecology and Conservation 2018, 393-418. [CrossRef]

- Burgeot, T.; et al. (2008). Oyster summer mortality risks associated with environmental stress. In Summer Mortality of Pacific Oyster Crassostrea Gigas. The Morest Project. Samain, J. F. & McCombie, H. (eds). Editions Quæ: Versailles, France, 107-151. ISBN 2759215334.

- Caffarri, S.; Tibiletti, T.; Jennings, R.; Santabarbara, S. A Comparison Between Plant Photosystem I and Photosystem II Architecture and Functioning. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2014, 15, 296–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carapeto, A. , Francisco, A., Pereira, P. & Porto, M. (2020). Lista vermelha da flora vascular de Portugal Continental. ISBN 978-972-27-2876-8.

- Carretta, L.; Masin, R.; Zanin, G. Review of studies analysing glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) occurrence in groundwater. Environ. Rev. 2022, 30, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal-Porras, I.; Santos, C.B.d.L.; Martins, M.; Santos, R.; Pérez-Lloréns, J.L.; Brun, F.G. Sedimentary organic carbon and nitrogen stocks of intertidal seagrass meadows in a dynamic and impacted wetland: Effects of coastal infrastructure constructions and meadow establishment time. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 115841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, A.d.J.V.; Colares, I.G.; Franco, T.C.R.d.S.; Cutrim, M.V.J.; Luvizotto-Santos, R. Using a toxicity test with Ruppia maritima (Linnaeus) to assess the effects of Roundup. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 91, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedergreen, N.; Olesen, C.F. Can glyphosate stimulate photosynthesis? Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2010, 96, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-H.; Xu, M.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, L.-T. Effects of Nitrogen Deficiency on the Photosynthesis, Chlorophyll a Fluorescence, Antioxidant System, and Sulfur Compounds in Oryza sativa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.J.; Berges, J.A.; Young, E.B. Rapid effects of diverse toxic water pollutants on chlorophyll a fluorescence: Variable responses among freshwater microalgae. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2615–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolen, E.J.; Arts, I.C.; Swennen, E.L.; Bast, A.; Stuart, M.A.C.; Dagnelie, P.C. Simultaneous determination of adenosine triphosphate and its metabolites in human whole blood by RP-HPLC and UV-detection. J. Chromatogr. B 2008, 864, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.M.; Silva, J.; Barrote, I.; Santos, R. Heatwave Effects on the Photosynthesis and Antioxidant Activity of the Seagrass Cymodocea nodosa under Contrasting Light Regimes. Oceans 2021, 2, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupe, R.H.; Kalkhoff, S.J.; Capel, P.D.; Gregoire, C. Fate and transport of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid in surface waters of agricultural basins. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravo, A.; Barbosa, A.; Correia, C.; Matos, A.; Caetano, S.; Lima, M.; Jacob, J. Unravelling the effects of treated wastewater discharges on the water quality in a coastal lagoon system (Ria Formosa, South Portugal): Relevance of hydrodynamic conditions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 174, 113296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cravo, A.; Fernandes, D.; Damião, T.; Pereira, C.; Reis, M.P. Determining the footprint of sewage discharges in a coastal lagoon in South-Western Europe. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 96, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, R.C.; Feijão, E.; Matos, A.R.; Cabrita, M.T.; Utkin, A.B.; Novais, S.C.; Lemos, M.F.L.; Caçador, I.; Marques, J.C.; Reis-Santos, P.; et al. Effects of Glyphosate-Based Herbicide on Primary Production and Physiological Fitness of the Macroalgae Ulva lactuca. Toxics 2022, 10, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, J.; Mosquim, P.; Pelacani, C.; Araújo, W.; DaMatta, F. Photosynthesis impairment in cassava leaves in response to nitrogen deficiency. Plant Soil 2003, 257, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A.H.; Assis, J.F.; Serrão, E.A. Seagrasses in Portugal: A most endangered marine habitat. Aquat. Bot. 2013, 104, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daouk, S.; Copin, P.-J.; Rossi, L.; Chèvre, N.; Pfeifer, H.-R. Dynamics and environmental risk assessment of the herbicide glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA in a small vineyard river of the Lake Geneva catchment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.d.C.; Boas, L.K.V.; Branco, C.C.Z. Assessment of the potential toxicity of glyphosate-based herbicides on the photosynthesis ofNitella microcarpavar. wrightii(Charophyceae). Phycologia 2016, 55, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.d.C.; Boas, L.K.V.; Branco, C.C.Z. Effect of herbicides based on glyphosate on the photosynthesis of green macroalgae in tropical lotic environments. Fundam. Appl. Limnol. 2021, 195, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, J.d.L.; Abadía, A.; Abadía, J. A New Reversed Phase-HPLC Method Resolving All Major Higher Plant Photosynthetic Pigments. Plant Physiol. 1989, 91, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de los Santos, C. B.; et al. (2020). Seagrass ecosystem services: Assessment and scale of benefits. Out of the Blue: The Value of Seagrasses to the Environment and to People. United Nations Environment Programme & GRID-Arendal (eds), 19-21. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/32636.

- Denny, M. Wave-Energy Dissipation: Seaweeds and Marine Plants Are Ecosystem Engineers. Fluids 2021, 6, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diepens, N.J.; Buffan-Dubau, E.; Budzinski, H.; Kallerhoff, J.; Merlina, G.; Silvestre, J.; Auby, I.; Tapie, N.; Elger, A. Toxicity effects of an environmental realistic herbicide mixture on the seagrass Zostera noltei. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 222, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, S.O. The history and current status of glyphosate. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, S.; Powles, S.B. Glyphosate: a once-in-a-century herbicide. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunic, J.C.; Brown, C.J.; Connolly, R.M.; Turschwell, M.P.; Côté, I.M. Long-term declines and recovery of meadow area across the world’s seagrass bioregions. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 4096–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erzini, K.; Parreira, F.; Sadat, Z.; Castro, M.; Bentes, L.; Coelho, R.; Gonçalves, J.M.; Lino, P.G.; Martinez-Crego, B.; Monteiro, P.; et al. Influence of seagrass meadows on nursery and fish provisioning ecosystem services delivered by Ria Formosa, a coastal lagoon in Portugal. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 58, 101490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance glyphosate: Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance glyphosate. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falace, A.; Tamburello, L.; Guarnieri, G.; Kaleb, S.; Papa, L.; Fraschetti, S. Effects of a glyphosate-based herbicide on Fucus virsoides (Fucales, Ochrophyta) photosynthetic efficiency. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felline, S.; Del Coco, L.; Kaleb, S.; Guarnieri, G.; Fraschetti, S.; Terlizzi, A.; Fanizzi, F.; Falace, A. The response of the algae Fucus virsoides (Fucales, Ochrophyta) to Roundup® solution exposure: A metabolomics approach. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 112977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltracco, M.; Barbaro, E.; Morabito, E.; Zangrando, R.; Piazza, R.; Barbante, C.; Gambaro, A. Assessing glyphosate in water, marine particulate matter, and sediments in the Lagoon of Venice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 16383–16391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmar, L.C.; Sanders, H.O.; Julin, A.M. Toxicity of the herbicide glyphosate and several of its formulations to fish and aquatic invertebrates. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1979, 8, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.; Leonard, H.; Springer, E.; Provoncha, T. Glyphosate Herbicide Impacts on the Seagrasses Halodule wrightii and Ruppia maritima from a Subtropical Florida Estuary. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, B.; Saikkonen, K.; Helander, M. Glyphosate-Modulated Biosynthesis Driving Plant Defense and Species Interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, K.; Khan, S.; Patrikar, M.; Markad, A.; Kumar, N.; Choudhari, A.; Sagar, P.; Indurkar, S. Exposure risk and environmental impacts of glyphosate: Highlights on the toxicity of herbicide co-formulants. Environ. Challenges 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdol, M.; Visintin, A.; Kaleb, S.; Spazzali, F.; Pallavicini, A.; Falace, A. Gene expression response of the alga Fucus virsoides (Fucales, Ochrophyta) to glyphosate solution exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.P.K.; Sethi, N.; Mohan, A.; Datta, S.; Girdhar, M. Glyphosate toxicity for animals. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A.M. Mechanistic aspects of xanthophyll cycle-dependent photoprotection in higher plant chloroplasts and leaves. Physiol. Plant. 1997, 99, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.P.; Juneau, P. Oxidative stress in duckweed (Lemna minor L.) induced by glyphosate: Is the mitochondrial electron transport chain a target of this herbicide? Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.P.; Le Manac’h, S.G.; Hénault-Ethier, L.; Labrecque, M.; Lucotte, M.; Juneau, P. Glyphosate-Dependent Inhibition of Photosynthesis in Willow. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.P.; Le Manac'H, S.G.; Maccario, S.; Labrecque, M.; Lucotte, M.; Juneau, P. Differential effects of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) on photosynthesis and chlorophyll metabolism in willow plants. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 130, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.P.; Smedbol, E.; Chalifour, A.; Hénault-Ethier, L.; Labrecque, M.; Lepage, L.; Lucotte, M.; Juneau, P. Alteration of plant physiology by glyphosate and its by-product aminomethylphosphonic acid: an overview. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4691–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, M.H.M.; Cunha, A.H.; Nzinga, R.L.; Marques, J.F. The distribution of seagrass (Zostera noltii) in the Ria Formosa lagoon system and the implications of clam farming on its conservation. J. Nat. Conserv. 2012, 20, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Oxidative damage, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant protection in chloroplasts. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1987, 44, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntscha, S.; Stravs, M.A.; Bühlmann, A.; Ahrens, C.H.; Frey, J.E.; Pomati, F.; Hollender, J.; Buerge, I.J.; Balmer, M.E.; Poiger, T. Seasonal Dynamics of Glyphosate and AMPA in Lake Greifensee: Rapid Microbial Degradation in the Epilimnion During Summer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 4641–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2017). Some organophosphate insecticides and herbicides. ISBN 978-92-832-0178-6.

- Ito, P.; Martins, M.; Gotha, S.v.S.-C.U.; Santos, R.; Santos, C.B.d.L. Seagrasses in coastal wetlands of the Algarve region (southern Portugal): Past and present distribution and extent. J. Sea Res. 2025, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iummato, M.M.; Fassiano, A.; Graziano, M.; Afonso, M.d.S.; Molina, M.d.C.R.d.; Juárez, Á.B. Effect of glyphosate on the growth, morphology, ultrastructure and metabolism of Scenedesmus vacuolatus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 172, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jassby, A.D.; Platt, T. Mathematical formulation of the relationship between photosynthesis and light for phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1976, 21, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasajima, I. Difference in oxidative stress tolerance between rice cultivars estimated with chlorophyll fluorescence analysis. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittle, R.P.; McDermid, K.J. Glyphosate herbicide toxicity to native Hawaiian macroalgal and seagrass species. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 2597–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, N.; Karadeniz, F.; Burdurlu, H.S. Effect of pH on chlorophyll degradation and colour loss in blanched green peas. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larbi, A.; Abadía, A.; Morales, F.; Abadía, J. Fe Resupply to Fe-deficient Sugar Beet Plants Leads to Rapid Changes in the Violaxanthin Cycle and other Photosynthetic Characteristics without Significant de novo Chlorophyll Synthesis. Photosynth. Res. 2004, 79, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latowski, D.; Kuczyńska, P.; Strzałka, K. Xanthophyll cycle – a mechanism protecting plants against oxidative stress. Redox Rep. 2011, 16, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Measurement and Characterization by UV-VIS Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, F4.3–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipok, J.; Studnik, H.; Gruyaert, S. The toxicity of Roundup® 360 SL formulation and its main constituents: Glyphosate and isopropylamine towards non-target water photoautotrophs. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2010, 73, 1681–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. , Jiang, Y., Luo, Y. & Jiang, W. (2006). A simple and rapid determination of ATP, ADP and AMP concentrations in pericarp tissue of litchi fruit by high performance liquid chromatography. Food Technology & Biotechnology, 44(4). ISBN 1330-9862.

- Ljones, T. Nitrogen fixation and bioenergetics: the role of ATP in nitrogenase catalysis. FEBS Lett. 1979, 98, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, N.A.; Carpenter, D.O. Effects of glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides like Roundup™ on the mammalian nervous system: A review. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, R.M.; Bidwell, J.R. The Toxicity of Glyphosate and Several Glyphosate Formulations to Four Species of Southwestern Australian Frogs. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1999, 36, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqueda, C.; Undabeytia, T.; Villaverde, J.; Morillo, E. Behaviour of glyphosate in a reservoir and the surrounding agricultural soils. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 593-594, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.C.; Alarcon, M.S.; Gleeson, D.; A Middleton, J.; Fraser, M.W.; Ryan, M.H.; Holmer, M.; A Kendrick, G.; Kilminster, K. Root microbiomes as indicators of seagrass health. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiz201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, E.J.; Malage, L.; Rocha, D.C.; Kitamura, R.S.A.; Gomes, S.M.A.; Navarro-Silva, M.A.; Gomes, M.P. Isolated and combined effects of glyphosate and its by-product aminomethylphosphonic acid on the physiology and water remediation capacity of Salvinia molesta. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 125694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Helman, R.J.; Miranda, L.A.; Afonso, M.d.S.; Salibián, A. Subcellular energy balance of Odontesthes bonariensis exposed to a glyphosate-based herbicide. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 114, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, P.; Flores, F.; Mueller, J.F.; Carter, S.; Negri, A.P. Glyphosate persistence in seawater. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 85, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M.M.; Hoilett, N.; Lorenz, N.; Dick, R.P.; Liles, M.R.; Ramsier, C.; Kloepper, J.W. Glyphosate effects on soil rhizosphere-associated bacterial communities. Sci. Total. Environ. 2016, 543, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, A.; Mudge, S.M. Temperature and salinity regimes in a shallow, mesotidal lagoon, the Ria Formosa, Portugal. Estuarine, Coast. Shelf Sci. 2003, 57, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Brito, A.C.; Icely, J.D.; Derolez, V.; Clara, I.; Angus, S.; Schernewski, G.; Inácio, M.; Lillebø, A.I.; Sousa, A.I.; et al. Assessing, quantifying and valuing the ecosystem services of coastal lagoons. J. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 44, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Icely, J.; Falcao, M.; Nobre, A.; Nunes, J.; Ferreira, J.; Vale, C. Evaluation of eutrophication in the Ria Formosa coastal lagoon, Portugal. Cont. Shelf Res. 2003, 23, 1945–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Icely, J.; Cristina, S.; Perillo, G.M.E.; Turner, R.E.; Ashan, D.; Cragg, S.; Luo, Y.; Tu, C.; Li, Y.; et al. Anthropogenic, Direct Pressures on Coastal Wetlands. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.W.; Dahllöf, I. Direct and indirect effects of the herbicides Glyphosate, Bentazone and MCPA on eelgrass (Zostera marina). Aquat. Toxicol. 2007, 82, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcaray, L.; Zulet, A.; Zabalza, A.; Royuela, M. Impairment of carbon metabolism induced by the herbicide glyphosate. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Lin, W. Impacts of glyphosate on photosynthetic behaviors in Kappaphycus alvarezii and Neosiphonia savatieri detected by JIP-test. J. Appl. Phycol. 2012, 24, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G. L. , Vera, M. S. & Miranda, L. A. (2011). Effects of herbicide glyphosate and glyphosate-based formulations on aquatic ecosystems. Herbicides and environment, 16, 343-368. ISBN 9533074760.

- Pesce, S.; Fajon, C.; Bardot, C.; Bonnemoy, F.; Portelli, C.; Bohatier, J. Longitudinal changes in microbial planktonic communities of a French river in relation to pesticide and nutrient inputs. Aquat. Toxicol. 2008, 86, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaxton, W.C.; Podestá, F.E. The Functional Organization and Control of Plant Respiration. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2006, 25, 159–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiger, T.; Buerge, I.J.; Bächli, A.; Müller, M.D.; Balmer, M.E. Occurrence of the herbicide glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA in surface waters in Switzerland determined with on-line solid phase extraction LC-MS/MS. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 1588–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, P.; Yamamoto, Y. Damage to photosystem II by lipid peroxidation products. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupke, D. , Daniel, L. & Proefrock, D. (2016). Optimization of an enrichment and LC-MS/MS method for the analysis of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) in saline natural water samples without derivatization. J. Chromatogr. Sep. Tech, 7(5). [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Wang, L.; Xu, Q.; An, J.; Mei, Y.; Liu, G. Influence of glyphosate and its metabolite aminomethylphosphonic acid on aquatic plants in different ecological niches. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 246, 114155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Ralph, P.J. Herbicide toxicity of Halophila ovalis assessed by chlorophyll a fluorescence. Aquat. Bot. 2000, 66, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.N.; Rimando, A.M.; Duke, S.O. Aminomethylphosphonic Acid, a Metabolite of Glyphosate, Causes Injury in Glyphosate-Treated, Glyphosate-Resistant Soybean. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 5139–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relyea, R.A. The lethal impact of Roundup on aquatic and terrestrial amphibians. Ecol. Appl. 2005, 15, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón-von Osten, J.; Dzul-Caamal, R. Glyphosate Residues in Groundwater, Drinking Water and Urine of Subsistence Farmers from Intensive Agriculture Localities: A Survey in Hopelchén, Campeche, Mexico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, M.E. Glyphosate: A review of its global use, environmental impact, and potential health effects on humans and other species. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2018, 8, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.M.; de Molina, M.C.R.; Juárez, Á.B. Oxidative stress induced by a commercial glyphosate formulation in a tolerant strain of Chlorella kessleri. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2011, 74, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Toledo, J.; Castro, R.; Rivero-Pérez, N.; Bello-Mendoza, R.; Sánchez, D. Occurrence of Glyphosate in Water Bodies Derived from Intensive Agriculture in a Tropical Region of Southern Mexico. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 93, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruuskanen, S.; Fuchs, B.; Nissinen, R.; Puigbò, P.; Rainio, M.; Saikkonen, K.; Helander, M. Ecosystem consequences of herbicides: the role of microbiome. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2022, 38, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchís, J.; Kantiani, L.; Llorca, M.; Rubio, F.; Ginebreda, A.; Fraile, J.; Garrido, T.; Farré, M. Determination of glyphosate in groundwater samples using an ultrasensitive immunoassay and confirmation by on-line solid-phase extraction followed by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 2335–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandmann, G.; Römer, S.; Fraser, P.D. Understanding carotenoid metabolism as a necessity for genetic engineering of crop plants. Metab. Eng. 2006, 8, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, A.; Donkin, P.; Fileman, T.; Evans, S.; Donkin, M. Risk posed by the antifouling agent Irgarol 1051 to the seagrass, Zostera marina. Aquat. Toxicol. 1999, 45, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, Ł.; Baciak, M.; Bęś, A.; Adomas, B. The effects of glyphosate-based herbicide formulations on Lemna minor, a non-target species. Aquat. Toxicol. 2019, 209, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Barrote, I.; Costa, M.M.; Albano, S.; Santos, R.; Campbell, D.A. Physiological Responses of Zostera marina and Cymodocea nodosa to Light-Limitation Stress. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e81058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvera, O.; Harris, R.J.; Arrington, D.A. Measuring herbicide (73.3 % glyphosate) exposure response in Halophila ovalis (previously johnsonii) and Halodule wrightii seagrass. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeff, W.; Neumann, C.; Schulz-Bull, D.E. Glyphosate and AMPA in the estuaries of the Baltic Sea method optimization and field study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedbol, É.; Lucotte, M.; Labrecque, M.; Lepage, L.; Juneau, P. Phytoplankton growth and PSII efficiency sensitivity to a glyphosate-based herbicide (Factor 540®). Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 192, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, K.; Thompson, D. Ecological Risk Assessment for Aquatic Organisms from Over-Water Uses of Glyphosate. J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. Part B 2003, 6, 289–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strilbyska, O.M.; Tsiumpala, S.A.; Kozachyshyn, I.I.; Strutynska, T.; Burdyliuk, N.; Lushchak, V.I.; Lushchak, O. The effects of low-toxic herbicide Roundup and glyphosate on mitochondria. EXCLI journal. 2022, 21, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, N. L. , Hoy, J. & Seneff, S. (2016). Evidence that glyphosate is a causative agent in chronic sub-clinical metabolic acidosis and mitochondrial dysfunction. International Journal of Human Nutrition and Functional Medicine, 4(9).

- Tett, P.; Gilpin, L.; Svendsen, H.; Erlandsson, C.P.; Larsson, U.; Kratzer, S.; Fouilland, E.; Janzen, C.; Lee, J.-Y.; Grenz, C.; et al. Eutrophication and some European waters of restricted exchange. Cont. Shelf Res. 2003, 23, 1635–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torretta, V.; Katsoyiannis, I.A.; Viotti, P.; Rada, E.C. Critical Review of the Effects of Glyphosate Exposure to the Environment and Humans through the Food Supply Chain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, M.T.; Chu, L. Aquatic toxicity of glyphosate-based formulations: comparison between different organisms and the effects of environmental factors. Chemosphere 2003, 52, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bruggen, A.H.C.; Finckh, M.R.; He, M.; Ritsema, C.J.; Harkes, P.; Knuth, D.; Geissen, V. Indirect Effects of the Herbicide Glyphosate on Plant, Animal and Human Health Through its Effects on Microbial Communities. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 763917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, J.W.; Adams, J.B.; von der Heyden, S. Conservation implications of herbicides on seagrasses: sublethal glyphosate exposure decreases fitness in the endangered Zostera capensis. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vereecken, H. Mobility and leaching of glyphosate: a review. Pest Manag. Sci. 2005, 61, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, A. , Larroudé, S. & Humbert, J. F. (2011). Herbicide contamination of freshwater ecosystems: impact on microbial communities. Pesticides–Formulations, Effects, Fate. –InTech (Open Access Publisher), Reyeka (Croatia), 285-312. ISBN: 9533075325.

- Walsh, L.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. Impact of glyphosate (Roundup TM ) on the composition and functionality of the gut microbiome. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2263935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waycott, M.; Duarte, C.M.; Carruthers, T.J.B.; Orth, R.J.; Dennison, W.C.; Olyarnik, S.; Calladine, A.; Fourqurean, J.W.; Heck, K.L., Jr.; Hughes, A.R.; et al. Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 12377–12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, M.A.; Schulz-Bull, D.E.; Kanwischer, M. The challenge of detecting the herbicide glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA in seawater – Method development and application in the Baltic Sea. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 128327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worm, B. & Reusch, T. B. (2000). Do nutrient availability and plant density limit seagrass colonization in the Baltic Sea? Marine Ecology Progress Series, 200, 159-166. [CrossRef]

- Young, A.J.; Lowe, G.M. Antioxidant and Prooxidant Properties of Carotenoids. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 385, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zobiole, L.H.S.; Kremer, R.J.; Jr. , R.S.d.O.; Constantin, J. Glyphosate effects on photosynthesis, nutrient accumulation, and nodulation in glyphosate-resistant soybean. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2012, 175, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Water temperature (a), pH (b) and salinity (c) (mean ± SE, n=5) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and with 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate.

Figure 1.

Water temperature (a), pH (b) and salinity (c) (mean ± SE, n=5) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and with 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate.

Figure 2.

Maximum (Fv/Fm; a) and effective (ΔF/Fm’; b) quantum yield of Z. marina’s photosystem II (mean ± SE, n=10) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and with addition of 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate.

Figure 2.

Maximum (Fv/Fm; a) and effective (ΔF/Fm’; b) quantum yield of Z. marina’s photosystem II (mean ± SE, n=10) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and with addition of 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate.

Figure 3.

Foliar growth rate of Z. marina (mean ± SE, n=5) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and in plants exposed to 0.165 and 51 mg L-1 of glyphosate. Results from the one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments (F = test-statistic; P = p-value) are shown. The p-value in bold accounts for significant differences among treatments. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Foliar growth rate of Z. marina (mean ± SE, n=5) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and in plants exposed to 0.165 and 51 mg L-1 of glyphosate. Results from the one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments (F = test-statistic; P = p-value) are shown. The p-value in bold accounts for significant differences among treatments. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Photosynthesis-irradiance (P-I) curves of Z. marina’s leaves in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate; a) and after a four-day exposure to 0.165 mg L-1 (b) and 51 mg L-1 (c) of glyphosate after adjustment with the equation model of Jassby and Platt (1976).

Figure 4.

Photosynthesis-irradiance (P-I) curves of Z. marina’s leaves in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate; a) and after a four-day exposure to 0.165 mg L-1 (b) and 51 mg L-1 (c) of glyphosate after adjustment with the equation model of Jassby and Platt (1976).

Figure 5.

Z. marina’s foliar total chlorophylls (a), total carotenoids (b), chlorophyll a/b ratio (c) and total chlorophylls to total carotenoids ratio (d) (mean ± SE, 4 ≤ n ≤ 5) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and in plants exposed to 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate. Results from one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments (F and H = test-statistic; P = p-value) are shown. The p-values in bold account for significant differences among treatments (p<0.05). In (d), a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed instead of ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments.

Figure 5.

Z. marina’s foliar total chlorophylls (a), total carotenoids (b), chlorophyll a/b ratio (c) and total chlorophylls to total carotenoids ratio (d) (mean ± SE, 4 ≤ n ≤ 5) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and in plants exposed to 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate. Results from one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments (F and H = test-statistic; P = p-value) are shown. The p-values in bold account for significant differences among treatments (p<0.05). In (d), a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed instead of ANOVA. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments.

Figure 6.

AMP, ADP, ATP, total adenylates content (AT) and adenylate energy charge (AEC) (mean ± SE) in Z. marina leaves in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and after exposure to 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate (4 ≤ n ≤ 5). Results from Kruskal-Wallis and one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments are shown (F and H = test-statistic; P = p-value). The p-values in bold account for significant differences among treatments (p<0.05). Different letters indicate statistical differences among treatments (p<0.05).

Figure 6.

AMP, ADP, ATP, total adenylates content (AT) and adenylate energy charge (AEC) (mean ± SE) in Z. marina leaves in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and after exposure to 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate (4 ≤ n ≤ 5). Results from Kruskal-Wallis and one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments are shown (F and H = test-statistic; P = p-value). The p-values in bold account for significant differences among treatments (p<0.05). Different letters indicate statistical differences among treatments (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Dark respiration and photosynthetic parameters of Z. marina’s leaves (mean ± SE, n≥4) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and after a four-day exposure to 0.165 and 51 mg L-1 of glyphosate. Photosynthetic parameters were obtained after Jassby and Platt (1976) adjustment to the observed photosynthesis-irradiance data of Z. marina’s leaves. Dark respiration (μmolO2 gDW-1 h-1); Pmax, maximum photosynthetic rate (μmolO2 gDW-1 h-1); α, photosynthetic quantum efficiency; and Ik, minimum-saturation irradiance (μmol photons m-2 s-1). Results from one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments (F = test-statistic; P = p-value) are shown. The p-values in bold account for significant differences among treatments. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Dark respiration and photosynthetic parameters of Z. marina’s leaves (mean ± SE, n≥4) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and after a four-day exposure to 0.165 and 51 mg L-1 of glyphosate. Photosynthetic parameters were obtained after Jassby and Platt (1976) adjustment to the observed photosynthesis-irradiance data of Z. marina’s leaves. Dark respiration (μmolO2 gDW-1 h-1); Pmax, maximum photosynthetic rate (μmolO2 gDW-1 h-1); α, photosynthetic quantum efficiency; and Ik, minimum-saturation irradiance (μmol photons m-2 s-1). Results from one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments (F = test-statistic; P = p-value) are shown. The p-values in bold account for significant differences among treatments. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p<0.05).

Treatments

(Glyphosate) |

Dark Respiration

(μmolO2 gDW-1 h-1) |

Pmax

(μmolO2 gDW-1 h-1) |

α |

Ik

(μmol Photons m-2 s-1) |

| Control |

-3.448 ± 0.807 |

832.704 ± 32.927a

|

4.409 ± 0.450b

|

188.869 ± 20.661a

|

| 0.165 mg L-1

|

-17.336 ± 6.752 |

945.414 ± 89.636a

|

5.149 ± 1.168b

|

183.615 ± 45.154a

|

| 51 mg L-1

|

-22.893 ± 4.750 |

108.436 ± 3.512b

|

17.361 ± 4.237a

|

6.246 ± 1.538b

|

| F |

3.493 |

53.421 |

10.111 |

51.621 |

| P |

0.067 |

<0.001 |

0.003 |

<0.001 |

Table 2.

Photosynthetic pigments content in Z. marina leaves (mean ± SE) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and after exposure to 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate. Values are expressed in μmol gDW-1 (4 ≤ n ≤ 5). Results from one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments (F = test-statistic; P = p-value) are shown. The p-values in bold account for significant differences among treatments (p<0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments.

Table 2.

Photosynthetic pigments content in Z. marina leaves (mean ± SE) in control conditions (0 mg L-1 of glyphosate) and after exposure to 0.165, 51 and 5100 mg L-1 of glyphosate. Values are expressed in μmol gDW-1 (4 ≤ n ≤ 5). Results from one-way ANOVA testing for differences between treatments (F = test-statistic; P = p-value) are shown. The p-values in bold account for significant differences among treatments (p<0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments.

Pigments

(μmol gDW-1) |

Control |

0.165 mg L-1

|

51 mg L-1

|

5100 mg L-1

|

F |

P |

| Chl a

|

1,396 ± 0,081 |

1,604 ± 0,230 |

1,651 ± 0,396 |

1,850 ± 0,386 |

0,257 |

0,855 |

| Chl b

|

0,580 ± 0,036 |

0,690 ± 0,095 |

0,879 ± 0,216 |

1,152 ± 0,256 |

1,434 |

0,272 |

|

β-Carotene |

0,392 ± 0,015a

|

0,426 ± 0,053a

|

0,288 ± 0,077a

|

0,105 ± 0,014b

|

6,684 |

0,004 |

| Lutein |

0,362 ± 0,013 |

0,393 ± 0,057 |

0,467 ± 0,119 |

0,419 ± 0,082 |

0,226 |

0,877 |

| Lutein epoxide |

0,008 ± 0,001 |

0,006 ± 0,001 |

0,008 ± 0,002 |

0,005 ± 0,001 |

0,630 |

0,607 |

| Neoxanthin |

0,148 ± 0,005 |

0,167 ± 0,026 |

0,111 ± 0,034 |

0,087 ± 0,025 |

1,427 |

0,277 |

| Violaxanthin (V) |

0,332 ± 0,012a

|

0,346 ± 0,039a

|

0,227 ± 0,059a

|

0,053 ± 0,09b

|

8,256 |

0,002 |

| Antheraxanthin (A) |

0,006 ± 0,002 |

0,004 ± 0,001 |

0,003 ± 0,001 |

0,004 ± 0,001 |

0,949 |

0,442 |

| Zeaxanthin (Z) |

0,010 ± 0,001 |

0,007 ± 0,001 |

0,010 ± 0,002 |

0,007 ± 0,002 |

0,998 |

0,421 |

| V+A+Z |

0,346 ± 0,012a

|

0,357 ± 0,041a

|

0,240 ± 0,062a

|

0,064 ± 0,011b

|

7,550 |

0,003 |

| DES = (A+Z)/(V+A+Z) |

0,040 ± 0,008bc

|

0,030 ± 0,004c

|

0,056 ± 0,003b

|

0,160 ± 0,009a

|

73,875 |

7,998e-09 |

| (V+A+Z)/Chl a+b

|

0,176 ± 0,006a

|

0,160 ± 0,008a