Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1. Methods

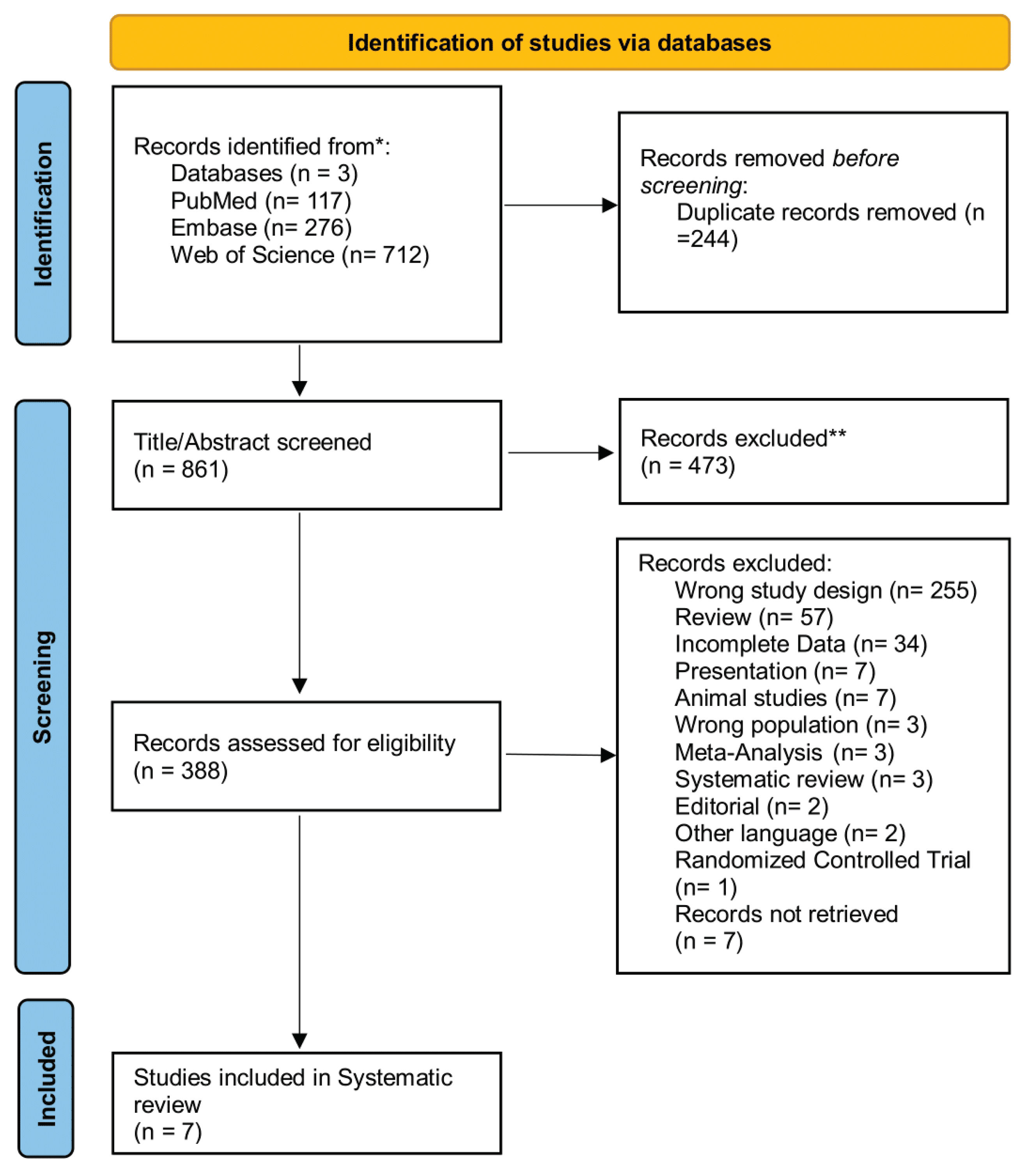

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Quality Assessment and Critical Appraisal

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

| aUC | Active Ulcerative Colitis |

| iUC | Inactive Ulcerative Colitis |

| HC | Healthy Controls |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| qPCR / qRT-PCR | Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| NOS | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| UCDAI | Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome |

| PSC | Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B cells |

| DSS | Dextran Sulfate Sodium |

| PI3K/Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog |

| IKKα | IκB Kinase α |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

References

- Feuerstein, J.D.; Moss, A.C.; Farraye, F.A. Ulcerative Colitis. Mayo Clin Proc 2019, 94, 1357–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gros, B.; Kaplan, G.G. Ulcerative Colitis in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbord, M.; Eliakim, R.; Bettenworth, D.; Karmiris, K.; Katsanos, K.; Kopylov, U.; Kucharzik, T.; Molnár, T.; Raine, T.; Sebastian, S.; et al. Third European Evidence-Based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 2: Current Management. J Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornbluth, A.; Sachar, D.B. Ulcerative Colitis Practice Guidelines in Adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2010, 105, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.T.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Siegel, C.A.; Sauer, B.G.; Long, M.D. ACG Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2019, 114, 384–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, M.; Loganathan, P.; Jimenez, G.; Catinella, A.P.; Ng, N.; Umapathy, C.; Ziade, N.; Hashash, J.G. A Comprehensive Review and Update on Ulcerative Colitis, Disease-a-Month 2019, 65, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, D.; Dhoble, P. Rapidly Changing Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Time to Gear up for the Challenge before It Is Too Late. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology 2024, 43, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorospe, J.; Windsor, J.; Hracs, L.; Coward, S.; Buie, M.; Quan, J.; Caplan, L.; Markovinovic, A.; Cummings, M.; Goddard, Q.; et al. TRENDS IN INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE ACROSS EPIDEMIOLOGIC STAGES: A GLOBAL SYSTEMATIC REVIEW WITH META-ANALYSIS. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2024, 30, S00–S00. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasvol, T.J.; Horsfall, L.; Bloom, S.; Segal, A.W.; Sabin, C.; Field, N.; Rait, G. Incidence and Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in UK Primary Care: A Population-Based Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, M.; Chung, H.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, H. Trends in the Prevalence and Incidence of Ulcerative Colitis in Japan and the US. Int J Colorectal Dis 2023, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, M.; Rosa, A. De; Serao, R.; Picone, I.; Vietri, M.T. Laboratory Markers in Ulcerative Colitis: Current Insights and Future Advances. http://www.wjgnet.com/ 2015, 6, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condrat, C.E.; Thompson, D.C.; Barbu, M.G.; Bugnar, O.L.; Boboc, A.; Cretoiu, D.; Suciu, N.; Cretoiu, S.M.; Voinea, S.C. MiRNAs as Biomarkers in Disease: Latest Findings Regarding Their Role in Diagnosis and Prognosis. Cells 2020, Vol. 9, Page 276 2020, 9, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruq, O.; Vecchione, A. MicroRNA: Diagnostic Perspective. Front Med (Lausanne) 2015, 2, 154087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, H.N.; Ciorba, M.A. Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Practices and Recent Advances. Translational Research 2012, 159, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 388354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bofill-De Ros, X.; Vang Ørom, U.A. Recent Progress in MiRNA Biogenesis and Decay. RNA Biol 2024, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchetti, M.; Ferraro, M.G.; Ricciardiello, F.; Ottaiano, A.; Luce, A.; Cossu, A.M.; Scrima, M.; Leung, W.Y.; Abate, M.; Stiuso, P.; et al. The Role of MicroRNAs in Development of Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, Vol. 22, Page 3967 2021, 22, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacon-Millan, P.; Lama, S.; Del Gaudio, N.; Gravina, A.G.; Federico, A.; Pellegrino, R.; Luce, A.; Altucci, L.; Facchiano, A.; Caraglia, M.; et al. A Combination of Microarray-Based Profiling and Biocomputational Analysis Identified MiR331-3p and Hsa-Let-7d-5p as Potential Biomarkers of Ulcerative Colitis Progression to Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Feng, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, Z.; Bei, B.; Zhang, L.; Han, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, N. Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation in Colitis Associated Cancer. Front Genet 2019, 10, 452964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Shi, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, N.; Zhang, P.; Wang, F.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Overexpression of MiR-21 in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis Impairs Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function through Targeting the Rho GTPase RhoB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013, 434, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado-Bedmar, M.; Roy, M.; Berthet, L.; Hugot, J.P.; Yang, C.; Manceau, H.; Peoc’h, K.; Chassaing, B.; Merlin, D.; Viennois, E. Fecal Let-7b and MiR-21 Directly Modulate the Intestinal Microbiota, Driving Chronic Inflammation. Gut Microbes 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, M.; Bjerrum, J.T.; Seidelin, J.B.; Troelsen, J.T.; Olsen, J.; Nielsen, O.H. MiR-20b, MiR-98, MiR-125b-1*, and Let-7e* as New Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers in Ulcerative Colitis. http://www.wjgnet.com/ 2013, 19, 4289–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yu, Y.; Tan, S. The Role of the MiR-21-5p-Mediated Inflammatory Pathway in Ulcerative Colitis. Exp Ther Med 2019, 19, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorlacius-Ussing, G.; Schnack Nielsen, B.; Andersen, V.; Holmstrøm, K.; Pedersen, A.E. Expression and Localization of MiR-21 and MiR-126 in Mucosal Tissue from Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017, 23, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, Q.; Song, J.; Wang, L.; Li, G. MiR-125b Inhibits Goblet Cell Differentiation in Allergic Airway Inflammation by Targeting SPDEF. Eur J Pharmacol 2016, 782, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmiki, S.; Ahuja, V.; Puri, N.; Paul, J. MiR-125b and MiR-223 Contribute to Inflammation by Targeting the Key Molecules of NFκB Pathway. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 6, 494658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, F.; Li, H.; Fan, H.; Wu, H.; Dong, Y.; Chu, S.; Tan, C.; Wang, Q.; He, H.; et al. MiR-155 Contributes to Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in DSS-Induced Mice Colitis via Targeting HIF-1α/TFF-3 Axis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 14966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Goten, J.; Vanhove, W.; Lemaire, K.; Van Lommel, L.; Machiels, K.; Wollants, W.J.; De Preter, V.; De Hertogh, G.; Ferrante, M.; Van Assche, G.; et al. Integrated MiRNA and MRNA Expression Profiling in Inflamed Colon of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e116117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Deng, S.; Yang, J.; Shou, Z.; Wei, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, F.; Gao, F.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Antagomir of MiR-31-5p Modulates Macrophage Polarization via the AMPK/SIRT1/NLRP3 Signaling Pathway to Protect against DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice. Aging 2024, 16, 5336–5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Tabuchi, T.; Minami, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Itoh, T.; Nakamura, M. Expression of Let-7i Is Associated with Toll-like Receptor 4 Signal in Coronary Artery Disease: Effect of Statins on Let-7i and Toll-like Receptor 4 Signal. Immunobiology 2012, 217, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suojalehto, H.; Toskala, E.; Kilpeläinen, M.; Majuri, M.L.; Mitts, C.; Lindström, I.; Puustinen, A.; Plosila, T.; Sipilä, J.; Wolff, H.; et al. MicroRNA Profiles in Nasal Mucosa of Patients with Allergic and Nonallergic Rhinitis and Asthma. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2013, 3, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, G.; Crucitta, S.; Bertani, L.; Ruglioni, M.; Svizzero, G.B.; Ceccarelli, L.; Del Re, M.; Danesi, R.; Costa, F.; Fogli, S. Expression of Circulating Let-7e and MiR-126 May Predict Clinical Remission in Patients With Crohn’s Disease Treated With Anti-TNF-α Biologics. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2024, 30, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.G.; He, Q.; Guo, S.Q.; Shi, Z.Z. Reduced Serum MIR-98 Predicts Unfavorable Clinical Outcome of Colorectal Cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23, 8345–8353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.Y.; Huang, Z.C.; Zhang, H.L.; Xiao, Z.G.; Liu, Q. Rs13293512 Polymorphism Located in the Promoter Region of Let-7 Is Associated with Increased Risk of Radiation Enteritis in Colorectal Cancer. J Cell Biochem 2018, 119, 6535–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.H.; Jiang, X.G.; Lu, W.H. Inhibition of MiR-155 Alleviates Sepsis-Induced Inflammation and Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction by Inactivating NF-ΚB Signaling. Int Immunopharmacol 2021, 90, 107218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zuo, D.; Liu, X.; Fan, H.; Chen, Q.; Deng, S.; Shou, Z.; Tang, Q.; Yang, J.; Nan, Z.; et al. MiR-155 Contributes to Th17 Cells Differentiation in Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS)-Induced Colitis Mice via Jarid2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 488, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, N.; Niu, M. Faecal MicroRNA as a Biomarker of the Activity and Prognosis of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 503, 2443–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Tian, D.; Wei, J.; Yan, C.; Hu, P.; Wu, X.; Yang, W.; Zhu, Z. MiR-199a-5p Exacerbated Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction through Inhibiting Surfactant Protein D and Activating NF-ΚB Pathway in Sepsis. Mediators Inflamm 2020, 2020, 8275026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shen, L.; Peng, S.; Tian, M.; Li, X.; Luo, H. Suppression of MiR-199a-5p Alleviates Ulcerative Colitis by Upregulating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Component XBP1. bioRxiv 2021, 2021.02.05.430002. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Kwon, H.Y.; Ha Thi, H.T.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, G. Il; Hahm, K.B.; Hong, S. MicroRNA-132 and MicroRNA-223 Control Positive Feedback Circuit by Regulating FOXO3a in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016, 31, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, Q.; Chao, K.; Zhou, G.; Qiu, Y.; Feng, R.; Huang, S.; He, Y.; et al. Circulating MicroRNA146b-5p Is Superior to C-Reactive Protein as a Novel Biomarker for Monitoring Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019, 49, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sabbagh, E.; Shaker, O.; Kassem, A.M.; Khairy, A. Role of Circulating MicroRNA146b-5p and MicroRNA-106a in Diagnosing and Predicting the Severity of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Egypt J Chem 2023, 66, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Keywords | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ("microRNA" OR "miRNA" OR "mir" OR "microRNAs" OR "miRNAs") | 222,472 |

| ("biomarker" OR "biomarkers" OR "diagnostic marker" OR "molecular marker") | 927,326 | |

| ("ulcerative colitis" OR "active ulcerative colitis" OR "inactive ulcerative colitis" OR "remission ulcerative colitis" OR "flare ulcerative colitis" OR "quiescent ulcerative colitis") | 66,276 | |

| #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 117 | |

| Web of Science | microRNA OR miRNA OR mir OR microRNAs OR miRNAs AND biomarker OR biomarkers OR diagnostic marker OR molecular marker AND ulcerative colitis OR active ulcerative colitis OR inactive ulcerative colitis OR remission ulcerative colitis OR flare ulcerative colitis OR quiescent ulcerative colitis | 712 |

| Embase | microRNA OR miRNA OR mir OR microRNAs OR miRNAs AND biomarker OR biomarkers OR diagnostic marker OR molecular marker AND ulcerative colitis OR active ulcerative colitis OR inactive ulcerative colitis OR remission ulcerative colitis OR flare ulcerative colitis OR quiescent ulcerative colitis | 276 |

| Parameters | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult Individuals with a Confirmed Diagnosis of Ulcerative Colitis and Differentiation based on Disease State | Studies about adult Individuals with non-UC conditions (e.g., Crohn's disease, general IBD, etc.). |

| Intervention | miRNAs as Diagnostic Tool to Assess UC Disease State | Studies that use any other biomolecules as biomarkers. |

| Comparison | N/A | N/A |

| Outcome | miRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarker for Differentiating Active and Inactive UC | No Significant change in miRNA expression level capable of differentiating Active UC from Inactive UC |

| Author, Year | Study Design | NOS Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | Comparability | Outcome/Exposure | ||

| Feng et all., 2012 | Case-Control | ✩✩✩✩ | ✩✩ | |

| Coskun et al., 2013 | Cohort | ✩✩✩✩ | ✩ | |

| Van der Goten et all., 2014 | Case-Control | ✩✩✩✩ | ✩ | ✩✩ |

| Schönauen et all., 2017 | Cohort | ✩✩✩✩ | ✩ | |

| Yahong et all., 2018 | Case-Control | ✩✩✩✩ | ✩✩ | |

| Peng et all., 2019 | Cohort | ✩✩✩✩ | ✩ | ✩✩ |

| El Sabbagh et.al., 2023 | Case-Control | ✩✩✩✩ | ✩✩ | |

| Author and Year | Study Design | Sample Type | Sample Size (aUC/iUC/HC) | Gender (M/F) | miRNA Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feng et al., 2012 | Case-control | Pinch biopsies | 12/10/15 | 5/7, 4/6, 7/8 | qRT-PCR |

| Coskun et al., 2013 | Cohort | Pinch biopsies | 20/19/20 | 9/11, 6/13, 10/10 | miRNA microarray, qPCR |

| Van der Goten et al., 2014 | Case-control | Colonic mucosal biopsies | 10/7/10 | 6/4, 4/3, 5/5 | miRNA microarray, qRT-PCR |

| Schönauen et al., 2017 | Cohort | Serum and Fecal Samples | 10/8/35 | 4/6, 4/4, 14/21 | qPCR |

| Yahong et al., 2018 | Case Control | Fecal Samples | 41/25/66 | NR | miRNA microarray, qPCR |

| Peng et al., 2019 | Cohort | Serum Samples | 55/45/41 | NR | qRT-PCR |

| El Sabbagh et al., 2023 | Case Control | Blood Samples | 33/2/30 | NR | qPCR |

| Author (Year) | miRNAs Studied | Disease Duration (yrs) mean (range) | Disease Activity Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feng et al. (2012) | miR-21, miR-126, miR-375 | 1.8 (0.5–4) aUC, 4 (2–6) iUC | UCDAI: 0.9 (0-2) iUC, 8.91 (8-10) aUC | miR-126 (↑18-fold, P < 0.05) in aUC vs HC. miR-21 (↑14.7-fold, P < 0.05) in aUC vs HC. No significant changes in iUC vs HC. |

| Coskun et al. (2013) | miR-20b, -99a, -203, -26b, -98, -125b-1, let-7e | 15/5 aUC, 8/11 iUC | Mayo: 0 (0-1) iUC, 6 (2-12) aUC | miR-20b (↑ P < 0.05) in aUC vs HC. let-7e (↑ P < 0.05) in iUC vs HC. miR-98 (↑ P < 0.05) in iUC vs aUC and HC. miR-125b-1 (↑ P < 0.01) in aUC vs HC. |

| Van der Goten et al. (2014) | miR-21-5p, miR-31-5p, miR-146a-5p, miR-155-5p, miR-650, miR-196b-5p, miR-200c-3p, miR-375, miR-200b-3p, miR-422a | 7.1 (0.6–20.1) aUC, 6.6 (4.0–14.4) iUC | Mayo: 0 (±0.5) iUC, 8 (±1.5) aUC | miR-21-5p, miR-31-5p, miR-146a-5p, miR-155-5p, miR-650, miR-375 (↑) in aUC vs HC. miR-196b-5p, miR-196b-3p, miR-200c-3p (↓) in aUC vs HC. |

| Schönauen et al. (2017) | miR-16, miR-21, miR-155, miR-223 | NR | Mayo: ≤5.27 iUC, >5.27 aUC | miR-21, miR-223 (↑) in iUC vs HC serum. miR-21, miR-155 (↓) in aUC vs iUC serum. miR-16, miR-155, miR-223 (↓) in aUC vs HC feces. miR-155 (↓) in aUC & iUC vs HC feces. |

| Yahong et al. (2018) | miR-199a, miR-223-3p, miR-1226, miR-548ab, miR-515-5p | 6.5 aUC, 11.5 iUC | Modified Mayo: ≤2 iUC, >2 aUC | miR-515, miR-548ab, miR-1226 (↓) in aUC vs HC and iUC vs HC. miR-199a-5p, miR-223-3p (↑) in aUC vs HC and iUC. |

| Peng et al. (2019) | miR-197-5p, miR-603, miR-145-3p, miR-574-3p, miR-34a-5p, miR-323a-3p, miR-141-3p, miR-146b-5p, miR-193b-3p, miR-31-5p, miR-27a, miR-27b, miR-944, miR-204-3p, miR-206, miR-24-1-5p, miR-135b-5p | NR | Mayo: ≤2 iUC, >2 aUC | miR-146b-5p (↑) in aUC vs iUC and HC. |

| El Sabbagh et al. (2023) | miR-106a, miR-146b | NR | Mayo: No specific cut values | No significant change between aUC and iUC. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).