Submitted:

23 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and methods

miRNA selection from the microRNA Cancer Association Database

Sample preparation

miRNA quantification using polyadenylation RT-PCR

miRNA quantification using stem-loop RT-PCR

Statistical analysis

Results

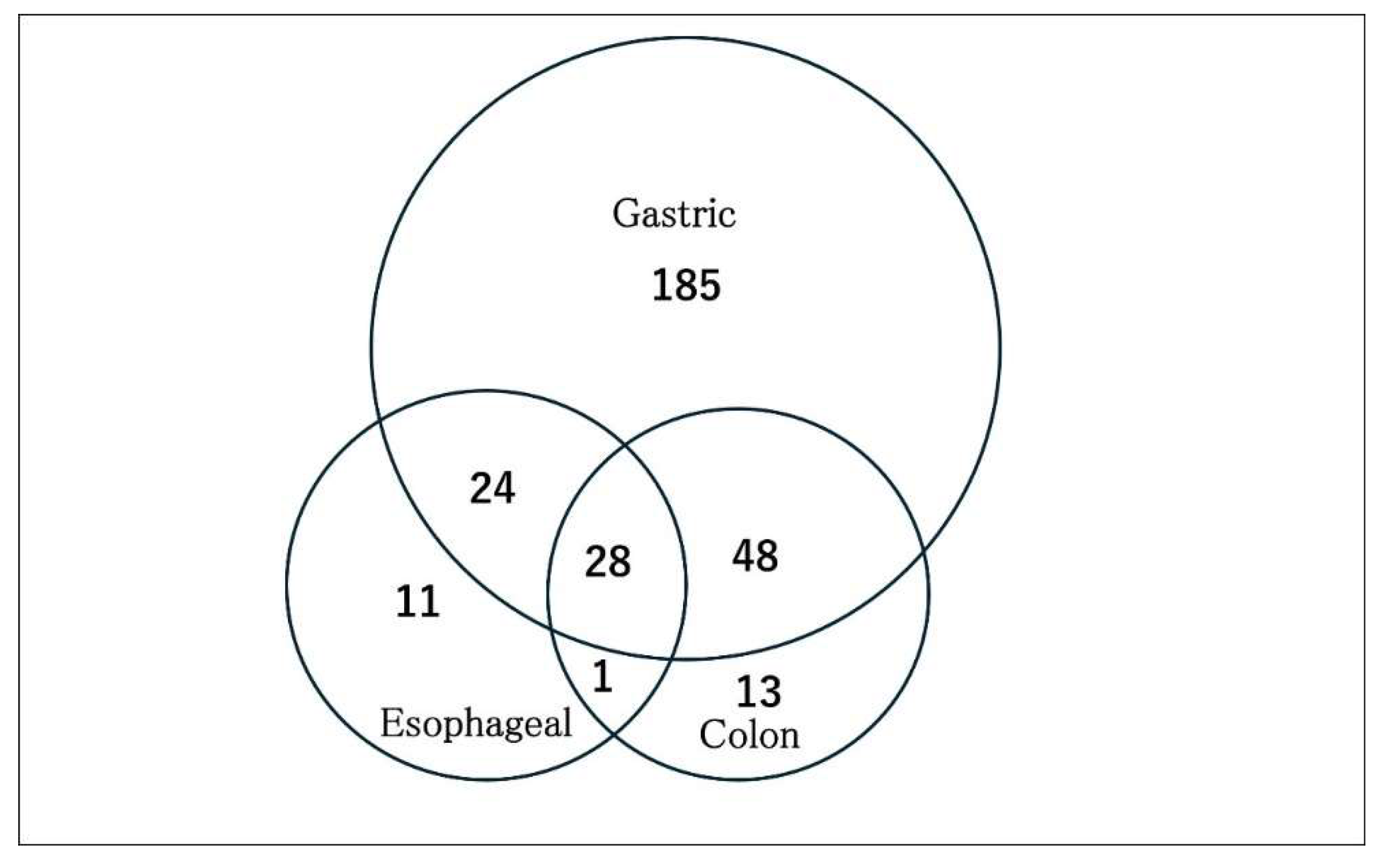

Search for potential plasma miRNA biomarkers for GC using a web application

Comparison of variability between polyadenylation and stem-loop RT-PCR for miRNA quantification

Higher plasma mir-222 expression is noted in patients with advanced tumor characteristics and a lower nutritional status

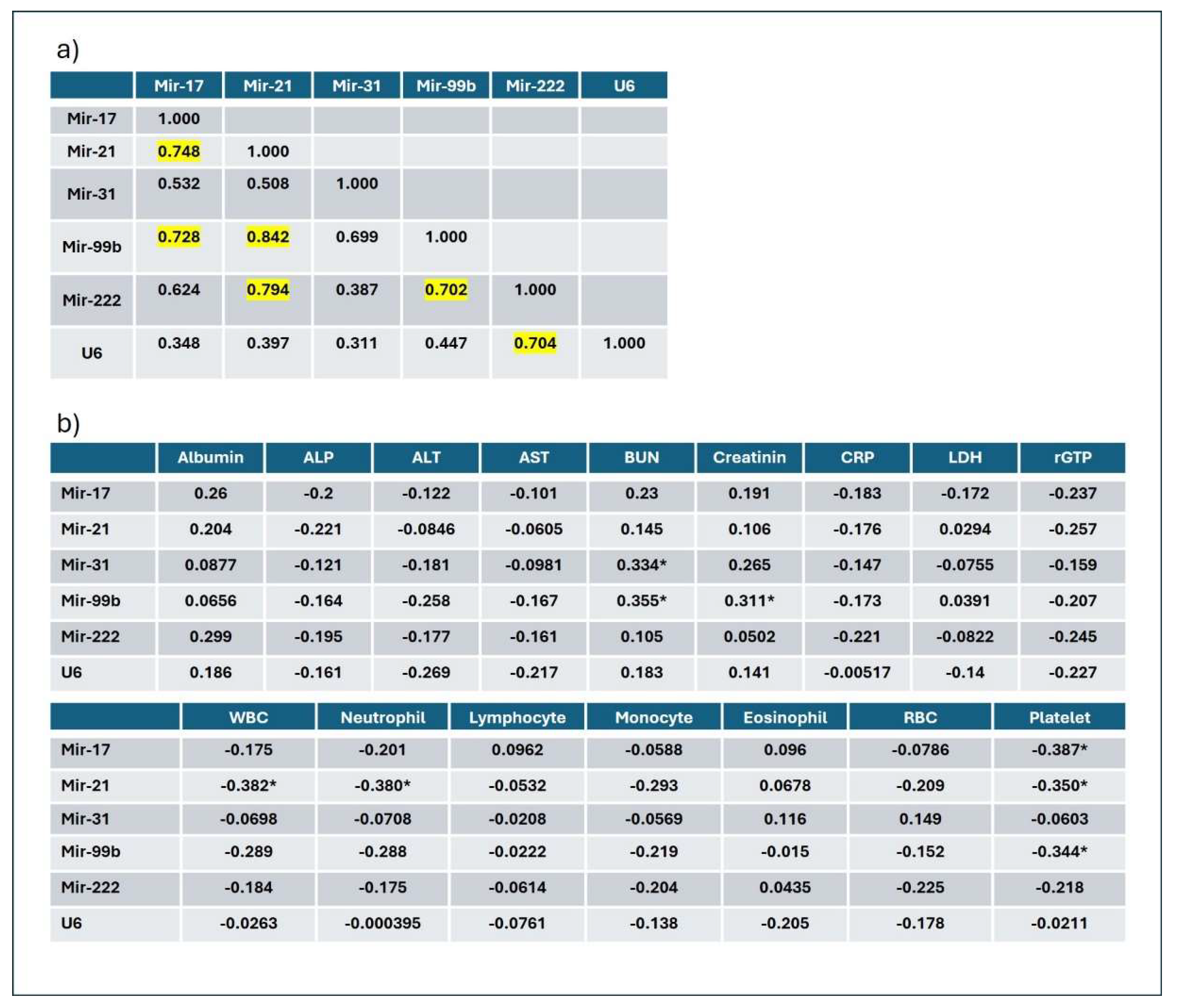

Plasma miRNA correlation analysis

Discussion

Human rights and statement and informed consent

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel R, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 caners in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar]

- Higashi T, Kurokawa. Incidence, mortality, survival and treatment statics of cancers in digestive organs-Japanese cancer statistics 2024. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2024, 00, 1–8.

- Alsina M, Arrazubi V, Diez M, Tabernero J. Current development in gastric cancer from molecular profiling to treat strategy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, 20, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan H, Lu H, Wang X, Jin H. Micro RNA as potential biomarkers in cancer: opportunities and challenges. BioMed Res Int. 2015, 2015, 125094. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003, 425, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediated the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 3011–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki S, Kobayashi M, Yoda M, Sakaguchi Y, Katsuma S, Suzuki T, et al. Hsc70/Hsp90 chaperon machinery mediates ATP-dependent RISC loading of small RNA duplexes. Mol Cell. 2010, 39, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata T, Tomari Y, Making RISC. Making RISC. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010, 35, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen CYA, Shyu AB. Mechanism of deadenylating-dependent decay. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2011, 2, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui B, Beyett TS, Chen Z, Li X, La Rocca GL, Gazlay WM, et al. Oncogenic K-Ras Suppresses global miRNA function. Mol Cell. 2023, 83, 2509–2523.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005, 435, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi A, Matsuzaki J, Yamamoto Y, Yoneoka Y, Takahashi K, Shimizu H, et al. Integrated extracellular microRNA profiling for ovarian cancer screening. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano N, Matsuzaki J, Ichikawa M, Kawauchi J, Takizawa S, Aoki Y, et al. A serum microRNA classifier for the diagnosis of sarcomas of various histological subtypes. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi T, Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, Tsujiura M, Takeshita H, Hirajima S, et al. Circulating microRNAs: a next-generation clinical biomarker for digestive system cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2016, 17, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki J, Kato K, Oono K, Tsuchiya N, Sudo K, Shimomura A, et al. Prediction of tissue-of-origin of early-stage cancers using serum miRNomes. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023; 7.

- Chen Y, Gelfond JAL, McManus LM, Shireman PK. Reproducibility of quantitative RT-PCR array in miRNA expression profiling and comparison with maicroarray analysis. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10, 407. [Google Scholar]

- Parervand S, Weber J, Lemoine F, Consales F, Paillusson A, Dupasquir M, et al. Concordance among digital gene expression, microarray, and qPCR when measuring different expression of microRNAs. Bio Tech. 2010, 48, 219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen SG, Lamy P, Rasmussen MH, Ostenfeld MS, Dyrskjøt L, Orntoft TF, et al. Evaluation of the commercial global miRNA expression profiling platforms for detection of less abundant miRNAs. BMC Genomics. 2011, 12, 435. [Google Scholar]

- Dellett M, Simpson DA. Considerations for optimization of microRNA PCR assays for molecular diagnosis. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2016, 16, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou G, Wang K, Xu D, Zhou G. Evaluation of three RT-qPCR-based miRNA detection methods using seven rise miRNA. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013, 77, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie B, Ding Q, Han H, Wu D. miRCancer: a microRNA-cancer association database constructed by text mining on literature. Bioinformatics. 2013, 29, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang QX, Zhu YQ, Zhang H, Xiao J. Altered MiRNA expression in gastric cancer: a systemic review and meta analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015, 35, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 3rd English ed. 2011, 14, 101–112.

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-DeltaDelta C(T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed M, Nguyen H, Lai T, Kim DR. miRCancerdb: a database for correlation analysis between microRNA and gene expression in cancer. BMC Res Notes. 2018, 11, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Wang QX, Zhu YQ, Zhang H, Xiao J. Altered MiRNA Expression in Gastric Cancer: a systemic Review and Meta Analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015, 35, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou G, Wang K, Xu D, Zhou G. Evaluation of three RT-qPCR-based miRNA detection methods using seven rice miRNAs. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013, 77, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang M, Zeng Y, Yang R, Xu H, Chen Z, Zhong J, et al. U6 is not a suitable endogenous control for the quantification of circulating microRNAs. Biochem Biophys Resl Commun. 214, 210–214.

- Emami SS, Nekouian R, Akbari A, Faraji A, Abbasi V, Agah S. Evaluation of circulating miR-21 andmiR-222 as diagnostic biomarkers for gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2019, 15, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu Z, Qian F, Yang X, Jiang H, Chen Y, Liu S. Circulating miR-222 in plasma and its potential diagnostic and prognostic value in gastric cancer. Med Oncol. 2014, 31, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Song N, Yao H, Zhao L, Liu H, Li G. miR-221 and mir-222 simultaneously target RECK and regulate growth and invasion of gastric cancer cells. Med Sci Monit. 2015, 21, 2718–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng Y, Wang C, Shi T, Liu W, Liu H, Zhu B, et al. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 exerts functions in gastric cancer development via modulating microRNA-222-3p methylation and WEE1 expression. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2022, 100, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan X, Tang H, Bi J, Li N, Jia Y. MicroRNA-222-3p associated with Helicobacter pylori targets HIPK2 to promote cell proliferation, invasion, and inhibits apoptosis in gastric cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 5153–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li N, Yu N, Wang J, Xi H, Lu W, Xu H, et al. miR-222/VGLL4/YAP-TEAD1 regulatory loop promotes proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Chun-zhi Z, Lei H, An-Ling Z, Yan-Chao F, Xiao Y, Guang-Xiu W, et al. MicroRNA-221 and microRNA-222 regulate gastric carcinoma cell proliferation and radioresistance by targeting PTEN. BMC Cancer. 2010, 10, 367. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Wang X. miRDB: an online database for prediction of functional microRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48, D127–D131.

- Adam JM, Warren DG, Salim SH, Yi ANK, Sheena T, Kim R, et al. Platelets confound the measurement of extracellular miRNA in achieved plasma. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Myklebust MP, Rosenlund B, Gjengstø P, Bercea BS, Karlsdottir Á, Brydøy M, et al. Quantitative PCR measurement of miR-371a-3p and miR-372-p is influenced by hemolysis. Front Genet. 2019, 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkerova M, Belickova M, Bruchova H. Differential expression of microRNA in hematopoietic cell lineages. Eur J Haematol. 2008, 81, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garley M, Nowak K, Jabłońska E. Neutrophil microRNAs. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2024, 99, 864–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim RY, Sunkara KP, Bracke KR, Jarnicki AG, Donovan C, Hsu AC, et al. A microRNA21-mediated SATB1/S100A9/NF-kB axis promotes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease pathogenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2021, 13, eaav7223. [CrossRef]

- Kim RY, Horvat JC, Pinkerton JW, Starkey MR, Essilfie AT, Mayall JR, et al. MicroRNA-21 drives severe, steroid- insensitive experimental asthma by amplifying phosphoinositide 3 kinase mediated suppression of histone deacetylase 2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017, 139, 519–532.

- Bahareh FF, Kimia V, Mobina F, Shirin Y, Mohammed B, Reza M. NJ Life Sci. 2023, 316, 121340.

| Polyadenylation RT-PCR | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n=13 | Ct | SD | CV |

| mir-99b | 24.3 | 10.8 | 0.44 |

| U6 | 15 | 6.11 | 0.41 |

| Mean | 19.6 | 8.45 | 0.42 |

| Stem-loop RT-PCR | |||

| n=43 | Ct | SD | CV |

| mir-99b | 28.3 | 3.03 | 0.11 |

| U6 | 30.1 | 2.96 | 0.09 |

| Mean | 29.2 | 2.99 | 0.10 |

| GC (n=26) | CN (n=17) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro RNAs | |||

| Cta | |||

| mir-17 | 22.8±3.93 | 22.7±3.95 | 0.92 |

| mir-21 | 22.1±2.91 | 23.3±3.72 | 0.21 |

| mir-31 | 33.7±1.75 | 34.1±2.13 | 0.46 |

| mir-99b | 28.0±3.03 | 28.8±3.06 | 0.38 |

| mir-222 | 23.6±2.92 | 25.8±3.37 | 0.02* |

| U6 | 29.4±2.30 | 31.1±3.57 | 0.05 |

| Relative expression | |||

| mir-17 | 34.2 [7.17–125] | 40 [0.93–146] | 0.82 |

| mir-21 | 45.5 [23.5–10] | 23.9 [0.86–112] | 0.36 |

| mir-31 | 0.01 [0.003–0.017] | 0.008 [0.002–0.011] | 0.39 |

| mir-99b | 1.02 [0.20–2.25] | 0.30 [0.055–0.668] | 0.26 |

| mir-222 | 15.4 [7.79–45.0] | 5.27 [0.22–9.15] | <0.01** |

| U6 | 0.19 [0.084–0.454] | 0.085 [0.0066–0.182] | 0.04* |

| Tumor characteristicsc | |||

| Pathology | |||

| Poorly differentiated | 5 (19.2%) | 4 (23.5%) | |

| Signet cell-type | 4 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Tubular | 17 (65.4%) | 13 (76.5%) | 0.23 |

| Tumor thickness | |||

| T1 | 0 (0%) | 7 (41.2%) | |

| T2 | 0 (0%) | 3 (17.6%) | |

| T3 | 14 (53.8%) | 5 (29.4%) | |

| T4 | 12 (46.2%) | 2 (11/8%) | <0.01** |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| N0 | 14 (53.8%) | 7 (41.2%) | |

| N1 | 0 (0%) | 2 (11.8%) | |

| N2 | 2 (7.7%) | 6 (35.3%) | |

| N3 | 10 (38.5%) | 2 (11.8%) | 0.02* |

| Distant metastasis | |||

| M0 | 5 (19.2%) | 15 (88.2%) | |

| M1 | 21 (80.8%) | 2 (11.8%) | <0.01** |

| Tumor location | |||

| EGJ | 12 (46.2%) | 5 (29.4%) | |

| U | 2 (7.7%) | 1 (5.9%) | |

| M | 7 (26.9%) | 1 (5.9%) | |

| L | 5 (19.2%) | 10 (58.8%) | 0.04* |

| GC (n=26) | CN (n=17) | P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.3 [3.1–3.7] | 3.8 [3.6–3.8] | <0.01** |

| ALP (U/L) | 86.5 [70.5–129] | 80 [70–88] | 0.48 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 22 [13.5–39] | 13 [12.0–21] | 0.25 |

| AST (IU/L) | 31.5 [17.2–41.2] | 20 [15–30] | 0.06 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 15.1 [13.3–18.0] | 16.9 [15.1–17.7] | 0.54 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.77 [0.65–0.83] | 0.69 [0.55–0.81] | 0.12 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.095 [0.03–0.33] | 0.05 [0.02–0.59] | 0.63 |

| LDH (U/L) | 186 [152–213] | 177 [170–194] | 0.81 |

| γGTP (IU/L) | 23.5 [15.2–77] | 29.0 [16–31] | 0.58 |

| Blood cells | |||

| WBCs (/μL) | 4235 [3577–5937] | 5180 [3900–5660] | 0.42 |

| Neutrophils (/μL) | 2812 [2166–4086] | 2159 [1883–3615] | 0.21 |

| Lymphocytes (/μL) | 970 [816–1243] | 1871 [1367–2262] | <0.01** |

| Monocytes (/μL) | 334 [248–394] | 308 [249–331] | 0.63 |

| Eosinophils (/μL) | 145 [105–236] | 129 [89–180] | 0.34 |

| RBCs (/μL) | 355 [341–371] | 0.18 | |

| Platelets (/μL) | 24.1 [13.1–28.3] | 31.9 [17.2–33.6] | 0.03* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).