1. Introduction

In the face of climate change and growing environmental challenges, corporate sustainability and responsible financial decision-making have become central to business strategy. Sustainability reporting, especially under standards like Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)-G4, provides a structured way for firms to communicate their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) efforts (Bocken et al., 2015; Lee & Raschke, 2020). While ESG disclosure reflects a broader commitment to transparency, sustainability reporting serves as a key operational tool. Across global markets, ESG disclosures and sustainability reporting are increasingly used not just for compliance, but as strategic tools to manage climate risk, strengthen resilience, and build long-term stakeholder value (Greenwood & Warren, 2022; K. Wang et al., 2023; N. Wang et al., 2024).

Over the past three decades, sustainability reporting has shifted from a voluntary initiative to a formalized requirement in many jurisdictions, driven by regulatory reforms, investor expectations, and social pressures (Alsahali & Malagueño, 2022; Wakibi et al., 2024). This transition is especially evident in ASEAN economies, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore, where governments and capital markets increasingly demand transparent reporting aligned with ESG principles (Handoyo & Anas, 2024; Rudyanto & Siregar, 2018).

Firms disclose sustainability-related information to demonstrate accountability, enhance reputational capital, and attract long-term investors (Negera et al., 2025). Empirical studies have shown that comprehensive reporting can positively influence firm performance—particularly in indicators like Return on Assets (ROA) and Tobin’s Q—by improving transparency and strategic positioning (Bansal et al., 2021; Dincer et al., 2023; Hongming et al., 2020). However, the relationship between sustainability reporting and profitability metrics such as Net Profit Margin (NPM) remains inconsistent (Handoyo & Anas, 2024; Yilmaz, 2021), suggesting a need for deeper analysis into the financial implications of sustainability practices.

Behavioral dynamics such as herding behavior further complicate this relationship. Firms often mimic the financial strategies and disclosure practices of industry peers, especially under regulatory uncertainty or market pressure (Bikhchandani & Sharma, 2000; Brendea & Pop, 2019). While this imitation may expedite the adoption of sustainability initiatives, it also risks fostering symbolic compliance rather than substantive change (Gavrilakis & Floros, 2023; Q. Wang, 2023). Industry leaders tend to shape disclosure norms and benefit disproportionately from reputational and financial gains, whereas follower firms may merely replicate practices without achieving a similar impact (Liu et al., 2023; Misani, 2010; Saeed et al., 2024).

Despite increasing attention to ESG and sustainability reporting practices, few studies explore how herding behavior influences sustainability reporting and capital structure decisions, particularly within non-financial firms in emerging markets like those in ASEAN. Existing research often centers on herding in investor behavior or stock trading (Ahmad & Wu, 2022; Vieito et al., 2024), leaving a gap in understanding how such behavior operates at the firm level and affects long-term strategic outcomes (Chiang & Zheng, 2010).

Within ASEAN, diverse regulatory capacities further amplify this complexity. While some member states have adopted advanced ESG disclosure frameworks, including formal sustainability reporting standards, others face persistent governance challenges (Ang, 2024; Ramadhani, 2019). These disparities contribute to uneven adoption and may reinforce herding behavior as firms navigate unclear or evolving reporting expectations.

This study addresses these gaps by investigating the influence of herding behavior on capital structure and sustainability reporting in non-financial firms across ASEAN. It also examines how firm characteristics—specifically size and age—affect disclosure practices, and evaluates how sustainability reporting impacts financial performance using ROA, NPM, and Tobin's Q. Finally, the study explores whether herding behavior moderates the relationship between sustainability reporting and firm performance, distinguishing between industry leaders and followers.

To capture these complex relationships, the study applies Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and Multigroup Analysis (MGA), which allow for nuanced analysis of both direct and moderating effects. The findings offer theoretical insights into the intersection of behavioral finance and corporate sustainability and provide practical implications for firms and regulators navigating climate risk, strategic disclosure, and performance in the ASEAN region.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Herding Behavior in Capital Structure Decisions

Herding behavior refers to the tendency of firms to imitate the financial decisions of their peers rather than rely on firm-specific analysis (Jirasakuldech & Emekter, 2021; Vieito et al., 2024). This phenomenon is well documented across financial settings, including investment management, market trading, and corporate finance (Ahmad & Wu, 2022; Cai et al., 2019). In capital markets, investors often disregard private signals to follow collective patterns, resulting in price inefficiencies and heightened volatility (Aharon, 2021). Similarly, in corporate finance, firms may align their capital structure decisions—such as debt-to-equity ratios—with industry norms due to competitive pressure, uncertainty, or institutional mimicry (Ezeoha, 2011; Youssef, 2022).

Such imitation behavior tends to intensify during periods of market instability. Empirical studies confirm that herding increases in times of declining markets, financial stress, or high trading volume, especially in emerging economies where investor sentiment strongly influences managerial decisions (Economou et al., 2018; Ghorbel et al., 2023; Jirasakuldech & Emekter, 2021). Under these conditions, firms often replicate peers' financing strategies as a form of risk aversion or strategic signaling, even when it diverges from their optimal capital needs (Chiang & Zheng, 2010; M. U. D. Shah et al., 2017).

In corporate finance, capital structure decisions play a critical role in determining a company’s financial stability and long-term value. While firms should ideally optimize their mix of debt and equity to minimize capital costs (Fandella et al., 2023; Pais, 2017), herding behavior may lead them to replicate industry norms rather than tailoring financial strategies to their unique conditions. This imitation can result in inefficient capital structures, reducing flexibility and increasing vulnerability to market fluctuations.

To assess the presence of herding behavior in capital structure management, this study adopts the Herding Manager Index developed by Bo et al. (2016), which assigns a score of one to firms that display herd-like tendencies in financing decisions and zero otherwise. Prior research by S. S. H. Shah et al. (2019) confirms that these patterns are especially prevalent during periods of market uncertainty, when firms tend to follow the financing decisions of perceived industry leaders. However, limited research has examined how such behavior interacts with sustainability reporting practices—a gap this study seeks to address in the context of ASEAN economies.

2.2. Company Characteristics and Sustainability Reporting

Sustainability reporting functions as a key mechanism through which firms operationalize and disclose their ESG activities. By communicating their economic, environmental, and social performance, companies enhance transparency and accountability (Gallo & Christensen, 2011; Godha & Jain, 2015; Herbert & Graham, 2022). Guided by frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), sustainability reporting enables organizations to detail their impact on sustainability-related issues in a structured manner, serving as a practical implementation of ESG disclosure (Githaiga & Kosgei, 2023; GRI, 2021). While often initiated voluntarily to strengthen corporate legitimacy, this reporting practice is increasingly shaped by stakeholder expectations and regulatory developments across jurisdictions (Benameur et al., 2024; Farisyi et al., 2022).

Among the key drivers of sustainability reporting are company-specific characteristics, particularly size and age. These characteristics influence a firm’s capacity, visibility, and motivation to disclose non-financial information (Ali & Abdelfettah, 2019; L. Wang, 2023). Larger firms, due to their public exposure and stakeholder pressure, are more likely to report comprehensively on sustainability matters (Bhatia & Tuli, 2017; Desai, 2022). They also have more financial and human resources to support sustainability initiatives and reporting infrastructure (Jamil et al., 2021; Orazalin & Mahmood, 2020). While most studies indicate a positive relationship between firm size and the extent of sustainability reporting (Al-Qudah & Houcine, 2024; Gallo & Christensen, 2011), others suggest a nonlinear pattern, where medium-sized firms are the most active reporters (Agarwala et al., 2024; Haladu & Bin-Nashwan, 2022).

Company age is also positively associated with sustainability disclosure. Older firms often have more experience with reporting standards and have developed reputational capital that they aim to protect through consistent disclosures (Bhatia & Tuli, 2017; Orazalin & Mahmood, 2020). These firms are typically more institutionalized, with formalized reporting structures and long-term stakeholder engagement strategies (Herbert & Graham, 2022; Kumar et al., 2023). Studies indicate that firm age contributes to the quality and comprehensiveness of sustainability reports (Correa-Garcia et al., 2020; Prashar, 2023).

2.3. Sustainability Reporting and Corporate Financial Performance

Sustainability reporting has emerged as a key mechanism for reducing information asymmetry, allowing investors to better evaluate corporate risks, long-term cash flows, and overall credibility (Al Natour et al., 2022; Upaa & Iorlaha, 2023). A growing body of empirical research supports the notion that structured sustainability disclosures contribute to improved profitability and operational performance (Al Hawaj & and Buallay, 2022; Benameur et al., 2024; Mihai & Aleca, 2023).

To fully understand the value of sustainability reporting, it is essential to examine its impact on corporate financial performance. As companies increasingly embed sustainability into their core strategies, stakeholders—particularly investors—demand evidence that such disclosures lead to measurable financial benefits (Christensen et al., 2021; Fisch, 2018). In terms of profitability, companies that provide transparent sustainability reports often record higher net profit margins, supported by operational efficiencies and strengthened stakeholder relationships (Buallay et al., 2021). Reports aligned with international standards such as the GRI reinforce corporate legitimacy, improve investor trust, and ultimately contribute to both revenue growth and cost savings (Mihai & Aleca, 2023).

Sustainability practices are also positively associated with return on assets. Firms that consistently disclose their environmental and social impacts tend to manage their resources more effectively, resulting in stronger asset utilization and financial outcomes (Alodat et al., 2024; Gavrilakis & Floros, 2023). Evidence from both developed and emerging markets—including smart cities and sustainability-oriented sectors—demonstrates the robustness of this relationship (Buallay et al., 2021; Chung et al., 2024).

Beyond profitability and efficiency, sustainability reporting also plays a critical role in shaping firm value, particularly as measured by Tobin's Q. Transparent and strategic disclosures enhance investor confidence, signaling long-term orientation and lower investment risk (Swarnapali, 2020; Younis, 2023). Companies that maintain credible and consistent sustainability reporting practices tend to attract long-term investors and benefit from favorable market valuations (Kim & Kim, 2018).

2.4. Sustainability Reporting and Corporate Financial Performance

Herding behavior refers to the tendency of companies to imitate the decisions of other firms in their industry rather than making independent strategic choices. This behavior often emerges in environments characterized by uncertainty and information asymmetry, where following industry norms is perceived as safer and more acceptable to stakeholders (Camara, 2017). Companies may engage in herding to reduce the risk of poor decision-making, gain legitimacy, or signal stability and reliability to investors (Komalasari et al., 2022). While firms are ideally expected to optimize their capital structure based on internal financial conditions, herding behavior can lead them to adopt financing decisions that mimic peer companies instead of reflecting their unique needs (Brendea & Pop, 2019). However, in some contexts, such imitation can create value. For example, He and Wang (2020) find that in China, firms that followed industry leaders in financial decisions reported improved long-term performance after regulatory reforms.

Herding is also common in the context of sustainability reporting. Firms frequently align their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure practices with those of their peers to maintain competitiveness, respond to stakeholder expectations, and meet evolving regulatory requirements (Saeed et al., 2024). This pattern is particularly evident in ASEAN countries, where companies increasingly adopt similar sustainability strategies to strengthen their standing in ESG ratings and sustainability indices. Gavrilakis and Floros (2023) observe similar trends in European markets, where ESG investment behaviors often cluster around dominant industry norms. These findings suggest that sustainability reporting can serve not only as a strategic communication tool but also as a means for companies to conform to industry-wide expectations.

The financial effects of herding behavior remain debated. Some studies suggest that companies that resist herding outperform others by making more efficient and firm-specific investment decisions (Jiang & Verardo, 2018). In contrast, other research shows that moderate herding, especially when firms follow credible industry leaders, can enhance financial outcomes such as return on assets (ROA) and market valuation (S. S. H. Shah et al., 2024). However, excessive reliance on imitation may lead to inefficient allocation of resources and ultimately weaken performance if peer strategies are not aligned with a firm's specific context.

Given this complex dynamic, it is essential to examine whether herding behavior moderates the relationship between sustainability reporting and corporate financial performance. In this study, financial performance is measured using net profit margin (NPM), ROA, and Tobin's Q. By exploring this moderating role, the research seeks to understand whether herding amplifies or diminishes the financial benefits of sustainability reporting among non-financial companies in ASEAN countries.

2.5. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Building on the prior literature, this study investigates the role of herding behavior and company characteristics in shaping sustainability reporting and its relationship with corporate financial performance. Herding behavior, as a behavioral finance construct, reflects a tendency among managers to align their decisions with those of peers rather than relying solely on firm-specific analysis. This tendency may manifest in capital structure decisions, especially during periods of economic uncertainty or regulatory shifts. Additionally, company characteristics such as size and age are established drivers of sustainability reporting, influencing firms’ capacities and incentives to disclose non-financial information. This study further explores how sustainability reporting affects corporate financial performance—measured through net profit margin (NPM), return on assets (ROA), and firm value (Tobin’s Q)—while assessing whether herding behavior moderates these relationships.

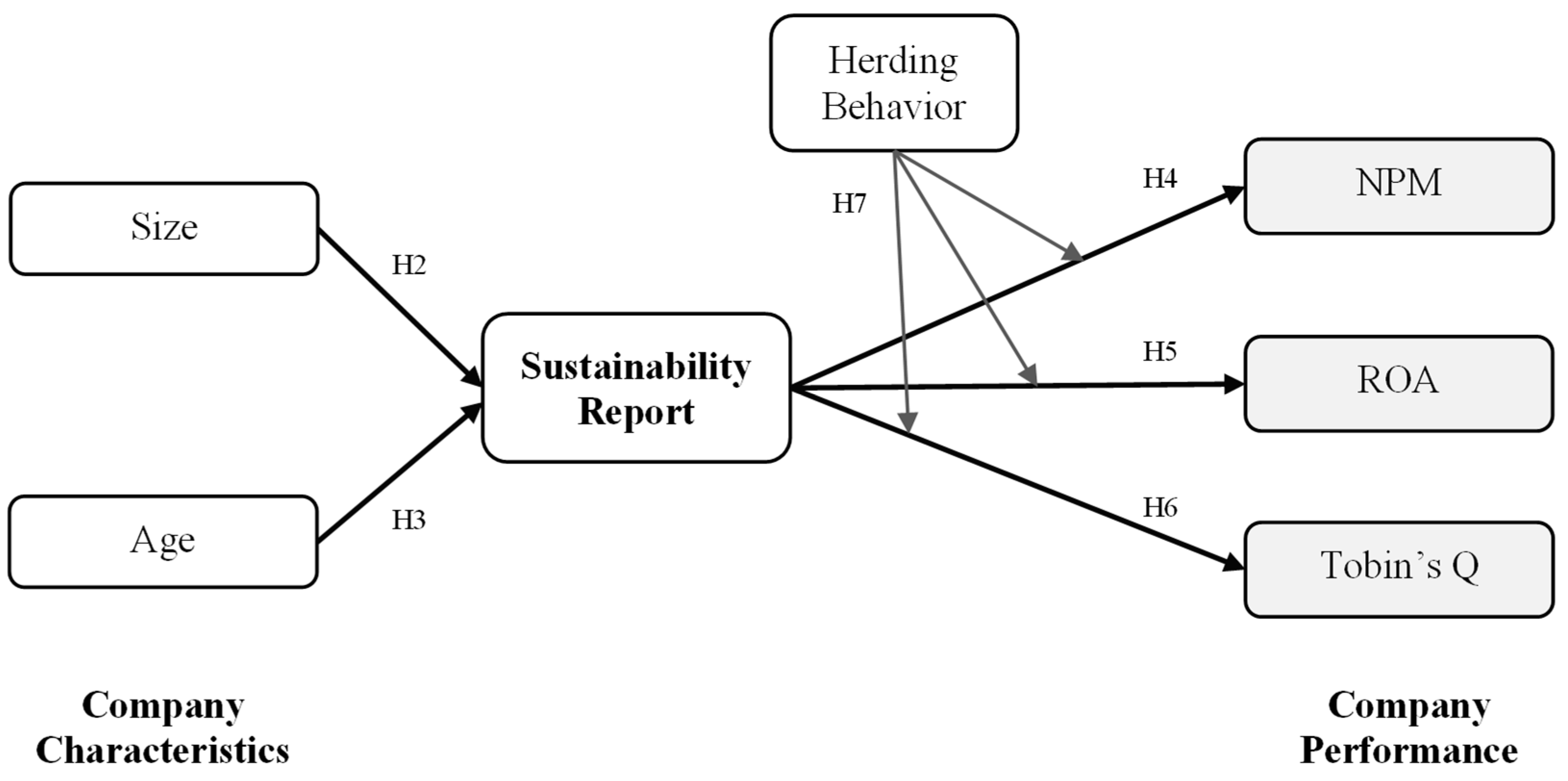

The proposed research model (

Figure 1) integrates these elements, capturing direct and moderating effects to provide a comprehensive understanding of how behavioral and structural factors intersect in the context of corporate sustainability and financial performance. The following hypotheses are developed to guide the empirical investigation:

H1. Herding behavior exists in capital structure management among non-financial companies that publish sustainability reports in five ASEAN countries;

H2. Company size positively affects sustainability reporting among non-financial companies in five ASEAN countries;

H3. Company age positively affects sustainability reporting among non-financial companies in five ASEAN countries;

H4. Sustainability reporting positively affects net profit margin (NPM) among non-financial companies in five ASEAN countries;

H5. Sustainability reporting positively affects return on assets (ROA) among non-financial companies in five ASEAN countries;

H6. Sustainability reporting positively affects Tobin's Q among non-financial companies in five ASEAN countries;

H7. Herding behavior moderates the relationship between sustainability reporting and company performance (NPM, ROA, Tobin's Q) among non-financial companies in five ASEAN countries.

3. Materials and Methods

This study examines the intersection of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure—operationalized through sustainability reporting—corporate financial performance, and herding behavior in capital structure decisions among non-financial companies in five ASEAN countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore. A quantitative approach is employed, focusing on firms listed on the respective national stock exchanges that issued sustainability reports in line with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI-G4) framework between 2018 and 2023.

To ensure analytical robustness, a purposive sampling strategy was applied with two criteria: (1) the company must be non-financial and listed on one of the five ASEAN stock exchanges; and (2) it must have published both complete audited financial statements and sustainability reports adhering to the GRI-G4 standards. Sustainability disclosure is measured using the Sustainability Report Disclosure Index (SRDI), which serves as a proxy for ESG disclosure by quantifying the extent to which firms report on environmental, social, and governance aspects based on 91 GRI-G4 indicators.

Table 1 presents the industry distribution of the sample, classified using the Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB).

The data used in this study were obtained from the Bloomberg Terminal, which provides standardized and reliable company-level financial and sustainability information. Since Bloomberg is a proprietary platform, direct access to the raw data is restricted. However, detailed variable descriptions and measurement procedures are included in

Table 2 to ensure replicability.

To identify herding behavior, the study employs the Managerial Herding Ratio (MHR), following Bo et al. (2016) and S. S. H. Shah et al. (2019). In this approach, the investment ratio—proxied by the Debt-to-Equity Ratio (DER)—is compared against the industry average. Herding is indicated when a firm's investment ratio closely mimics the industry norm. The following equation is used to calculate MHR:

where (I/K)

i,t is the investment ratio of company i at time t, and

−i,t−1 represents the average investment ratio of industry peers at t−1. A dummy variable of 1 is assigned if herding behavior is detected (i.e., deviation is minimal), and 0 otherwise.

To assess the moderating effect of herding, Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) is conducted using two classification approaches. In the MHR-based classification, companies with DER values closest to the industry average are labeled as leaders (dummy = 1), while those with significantly higher or lower DER values are classified as followers (dummy = 0). The SRDI-based classification, adapted from Leo et al. (2023) and Pais (2017), ranks companies by their SRDI scores each year. Firms in the top 50% (Q1 and Q2) are classified as leaders (dummy = 1), while those in the bottom 50% (Q3 and Q4) are labeled as followers (dummy = 0).

To test Hypothesis 1, the presence of herding behavior is analyzed using the MHR model. Hypotheses 2 through 7 are evaluated using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), conducted with WarpPLS software. This method is suitable for exploring complex path relationships, including moderation effects, particularly when data are non-normally distributed or when working with limited sample sizes. Generative artificial intelligence tools, specifically Grammarly, were used solely for language refinement and clarity enhancement. They were not involved in the design, data processing, statistical analysis, or interpretation of the study.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The first step in the analysis involves conducting a descriptive statistical assessment to summarize the distribution of each research variable. As shown in

Table 3, the results reveal substantial variation in company characteristics, sustainability reporting practices, and financial performance among the sampled firms. Differences in firm size, age, disclosure levels, and profitability measures indicate the heterogeneity of the non-financial sector across ASEAN markets during the 2018–2023 period.

4.2. Herding Behavior Analysis

To examine the existence of herding behavior, the Managerial Herding Index (MHR) was applied to five industries with sufficient firm representation (at least five firms per industry): Basic Materials, Consumer Goods, Consumer Services, Industrials, and Oil & Gas. The MHR categorizes companies annually as either engaging in herding (1) or not (0), based on the deviation of their investment ratio (proxied by DER) from the industry average.

As shown in

Table 4, herding behavior varies both across sectors and over time. In the Basic Materials industry, herding activity peaked in 2020 with 17 firms, then declined steadily in the following years. The Consumer Goods sector exhibits a relatively stable pattern, with between 4 and 7 companies exhibiting herding behavior annually. The Consumer Services sector—comprising the fewest firms—shows the lowest herding intensity, with only 2 to 3 firms engaging in herding each year.

The Industrials sector demonstrates moderate yet consistent herding, with the highest participation observed in 2018 and 2019 (14 companies), followed by a slight decline in subsequent years. In contrast, the Oil & Gas industry displays limited herding, with only 1 to 3 firms per year conforming to peer behavior.

These findings provide empirical support for Hypothesis 1, which posits the existence of herding behavior in capital structure management among non-financial firms. The results reveal that herding is more pronounced in capital-intensive and highly regulated sectors such as Basic Materials and Industrials. Conversely, Consumer Services and Oil & Gas demonstrate weaker tendencies toward herding, possibly due to more specialized strategies or less peer pressure. Moreover, the fluctuation of herding behavior across years suggests that broader economic and market conditions may influence managerial conformity in financing decisions.

4.3. Measurement Model Evaluation

This study employs Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the relationships between company characteristics, sustainability reporting, corporate financial performance, and the moderating role of herding behavior. Before assessing the structural model, the measurement model is first evaluated for validity and reliability.

Discriminant validity was assessed through latent variable correlation analysis. As shown in

Table 5, all inter-construct correlations fall below the 0.70 threshold, indicating adequate discriminant validity (MacKenzie et al., 2005). This confirms that the latent constructs are statistically distinct from one another and suitable for further analysis.

Subsequently, model fit indicators were examined to evaluate the structural model’s adequacy (

Table 6). The Average Path Coefficient (APC = 0.164, p < 0.01), Average Variance Inflation Factor (AVIF = 1.021), and Average Full Collinearity VIF (AFVIF = 1.071) all fall within acceptable thresholds, confirming acceptable model fit and the absence of multicollinearity issues. Similarly, other indices such as Simpson's Paradox Ratio (SPR), R-Squared Contribution Ratio (RSCR), and Statistical Suppression Ratio (SSR) achieved ideal values (equal to 1.000), indicating a well-specified model.

However, both the Average R-squared (ARS = 0.045, p = 0.054) and Adjusted ARS (AARS = 0.043, p = 0.058) do not meet conventional significance thresholds, implying limited explanatory power. This observation is reinforced by relatively low R-squared values for the endogenous constructs—Sustainability Reporting, NPM, ROA, and Tobin’s Q—all of which fall below 0.10, suggesting that only a small proportion of variance in these variables is explained by the model.

Despite this, the Q² predictive relevance values for all constructs are greater than zero, indicating that the model retains predictive relevance (Stone, 1974). Furthermore, the Full Collinearity VIFs for all variables are below the critical value of 3.3, confirming no multicollinearity concerns (Kock & Lynn, 2012).

Finally, the calculated effect sizes (ƒ²) indicate weak relationships between the constructs. For instance, company size and sustainability reporting exhibit a weak effect (ƒ² = 0.047), as do the links between sustainability reporting and firm performance indicators, such as ROA (ƒ² = 0.031) and Tobin’s Q (ƒ² = 0.089). Although these values meet the threshold for statistical relevance (ƒ² > 0.02), the results suggest that the relationships are modest in strength (Cohen, 1988).

Based on these evaluations, the measurement and structural models are deemed acceptable for hypothesis testing, despite the weak explanatory power. The results suggest that while the conceptual model is valid and statistically sound, other unmeasured variables may play a more substantial role in determining the variance in sustainability reporting and financial performance.

4.4. Structural Model Results

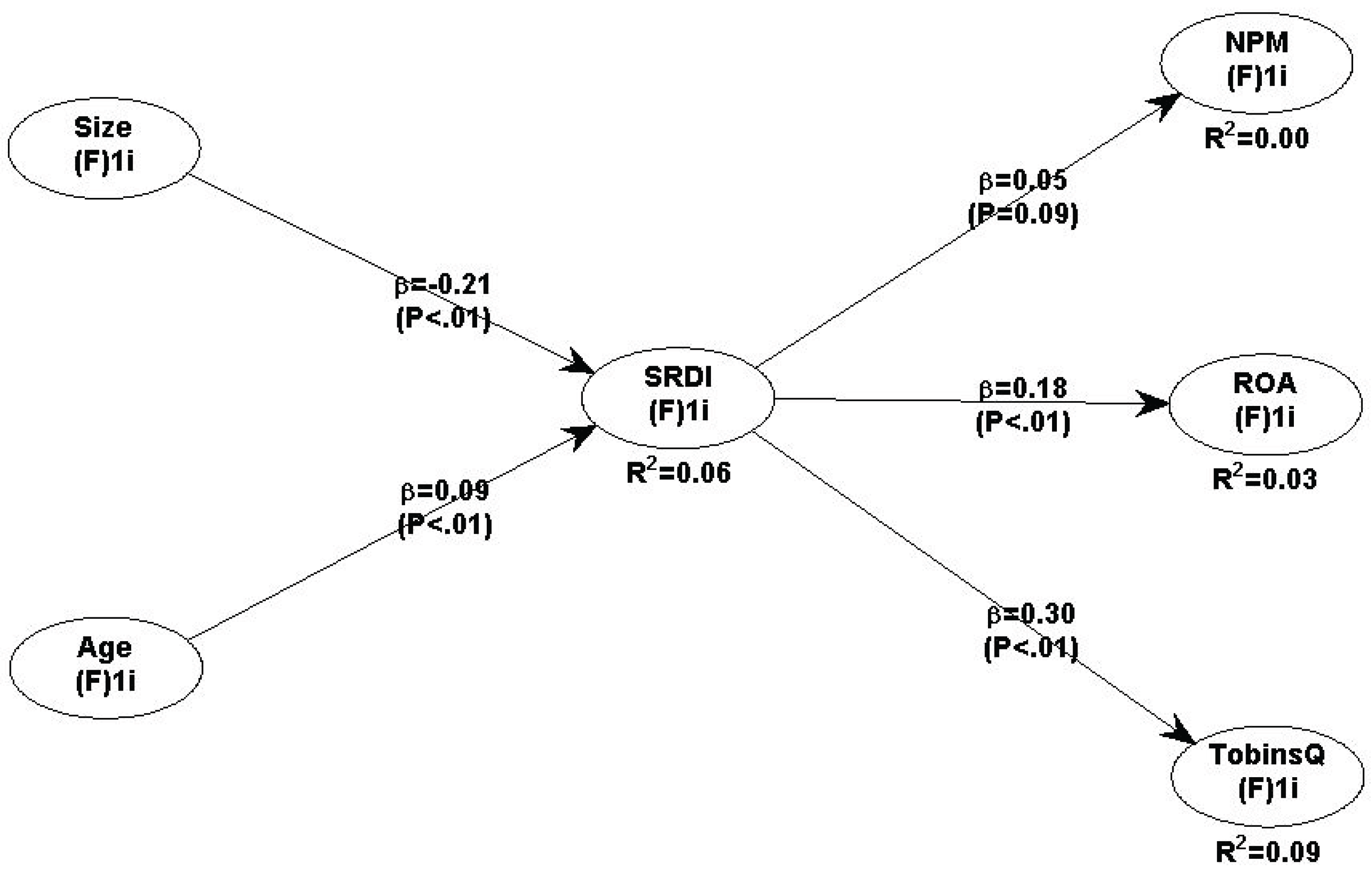

The structural model analysis evaluates the direct relationships between company characteristics, sustainability reporting, and firm performance. The results are summarized in

Figure 2 and

Table 7, providing insights into the significance and direction of each hypothesized path.

The analysis confirms support for three out of five direct effect hypotheses. Notably, Hypothesis 2 (H2) is statistically significant but yields a negative path coefficient (β = -0.210, p < 0.001), indicating that larger companies tend to disclose fewer sustainability-related indicators, which is contrary to expectations and previous literature. This unexpected finding may reflect strategic opacity among large firms or variations in reporting motivations across sectors and jurisdictions.

Hypothesis 3 (H3) is supported, with a positive and significant path coefficient (β = 0.088, p = 0.008), suggesting that older companies are more likely to engage in sustainability reporting. This result aligns with the assumption that more established firms may have developed the organizational maturity and stakeholder pressures that drive transparent ESG disclosure practices.

In contrast, Hypothesis 4 (H4) is not supported, as sustainability reporting does not show a significant relationship with net profit margin (NPM) (β = 0.049, p = 0.090). This implies that while ESG disclosure may contribute to long-term strategic positioning, it does not yield immediate profitability gains.

However, Hypothesis 5 (H5) and Hypothesis 6 (H6) are both supported, revealing that sustainability reporting positively affects return on assets (ROA) (β = 0.176, p < 0.001) and Tobin’s Q (β = 0.299, p < 0.001). These results highlight the financial and market benefits of robust ESG disclosure practices, suggesting that transparent sustainability communication can enhance investor perception and operational efficiency.

4.5. Multigroup Analysis by Country

To further explore the heterogeneity of sustainability reporting outcomes across ASEAN countries, a multigroup analysis (MGA) was conducted. This analysis assessed whether the effect of sustainability reporting on corporate financial performance differs significantly between country pairs. As shown in

Table 8, significant differences were observed in the impact of sustainability reporting on ROA and Tobin’s Q between several country pairs. The Philippines consistently showed the strongest effect, particularly in relation to ROA and Tobin’s Q, followed by Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore. Fewer differences were found for NPM, though significant variations were identified in some pairwise comparisons. These results suggest that the financial and market responses to sustainability reporting are not uniform across countries.

4.6. Moderating Effect of Herding Behavior

This study also examines the moderating role of herding behavior in the relationship between sustainability reporting and company performance through multigroup analysis (MGA). As shown in

Table 9, two models were employed to classify companies as leaders or followers. Model I uses the Sustainability Reporting Disclosure Index (SRDI) as the basis for classification, while Model II applies the Managerial Herding (MHR) index.

In Model I (SRDI-based classification), the results reveal no significant differences between leader and follower companies in the influence of sustainability reporting on performance outcomes. This suggests that the extent of sustainability disclosure alone does not differentiate the financial benefits derived from such reporting.

In contrast, Model II (MHR-based classification) shows significant moderating effects. The influence of sustainability reporting on Return on Assets (ROA) is significantly stronger among leader firms—those whose capital structure closely aligns with the industry average—compared to followers. Similarly, the effect on Tobin’s Q is notably higher for leader companies than for followers, indicating that firms demonstrating more independent capital structure decisions benefit more from sustainability disclosures in terms of market valuation. Additionally, the impact of company age on sustainability reporting differs significantly between leaders and followers in this model, suggesting that more established firms tend to integrate sustainability practices more effectively when they maintain capital structure discipline.

These findings support Hypothesis 7 (H7), affirming that herding behavior, as measured by MHR, moderates the relationship between sustainability reporting and corporate financial performance. This underscores the importance of strategic independence in capital structure decisions as a catalyst for deriving greater value from sustainability efforts.

5. Discussion

This study explores how company characteristics influence sustainability reporting and how such reporting, in turn, affects company performance—while accounting for the moderating role of herding behavior in non-financial firms across five ASEAN countries. The findings offer key insights into sustainability finance and organizational behavior, particularly within emerging economies navigating climate-related disclosure demands and stakeholder pressures.

The confirmation of herding behavior in capital structure decisions (H1) reinforces the view that companies are not purely guided by internal fundamentals but often mirror peer behavior in response to market signals or perceived norms. This aligns with earlier evidence by Camara (2017) and Aharon (2021), who argue that herding intensifies during periods of uncertainty, acting as a form of strategic conformity. Importantly, this behavioral pattern underscores a double-edged implication: while mimicking market leaders may encourage broader ESG adoption, it risks diluting the strategic authenticity of climate action if firms merely follow disclosure trends without embedding them meaningfully into operations. Thus, herding can function as both an accelerator and a constraint in advancing corporate climate resilience.

The finding that larger firms are less likely to engage in sustainability reporting (H2) challenges traditional assumptions that firm size correlates with higher transparency. While prior studies (Schreck & Raithel, 2015; Simoni et al., 2020) suggest that large firms disclose more to meet stakeholder expectations, this study finds a reverse pattern—possibly reflecting diminishing marginal incentives for firms that have already built reputational legitimacy. In contrast, company age positively influences sustainability reporting (H3), indicating that older firms are more likely to integrate ESG considerations into their disclosures, consistent with their accumulated experience and long-term orientation (Bhatia & Tuli, 2017; Farisyi et al., 2022).

Sustainability reporting significantly enhances financial and market-based performance measures—ROA and Tobin’s Q (H5 and H6)—but has no significant impact on net profit margin (H4). This indicates that while sustainability practices may boost operational efficiency and investor valuation, their financial benefits may not be immediate or visible in short-term profitability due to upfront costs or the long-term nature of climate investments (Alodat et al., 2024; Friede et al., 2015). These findings reaffirm the strategic value of sustainability as a long-term lever for competitive advantage rather than a short-term profitability driver.

This finding aligns with the broader literature on ESG investment, which underscores that sustainability initiatives often require significant upfront investments in climate-resilient infrastructure, emission reduction technologies, and enhanced transparency systems—costs that may not yield immediate returns but contribute to long-term value creation (Eccles et al., 2014; Khan et al., 2016). Moreover, ESG-aligned firms tend to prioritize stakeholder trust, regulatory preparedness, and environmental resilience over short-term profitability metrics. As noted by Clark et al. (2015), firms that embed ESG principles—particularly those addressing environmental and climate risks—are better positioned to withstand external shocks, attract long-term investors, and improve capital efficiency over time. Thus, while net profit margins may not reflect the benefits of sustainability reporting in the short run, these disclosures signal a firm's forward-looking orientation and adaptive capability in the face of climate change. In this light, sustainability reporting is not merely a compliance tool but a strategic mechanism for signaling resilience, ensuring stakeholder alignment, and strengthening long-term financial performance through climate-conscious governance.

The multigroup analysis reveals that the strength of the sustainability–performance link varies substantially across countries. The Philippines exhibits the highest performance impact, followed by Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore. These cross-country differences reflect disparities in regulatory environments, market maturity, and cultural engagement with ESG principles (Christensen et al., 2021; Ioannou & Serafeim, 2019). From the perspective of stakeholder theory and institutional theory, these differences can be interpreted as outcomes of differing levels of stakeholder salience and institutional pressure—both coercive and normative—that shape how sustainability practices are internalized and translated into performance outcomes (Frynas & Yamahaki, 2016; Marano et al., 2017).

In the case of the Philippines, the strongest relationship between sustainability reporting and company performance may stem from robust regulatory reforms—such as the enhanced disclosure requirements by the Securities and Exchange Commission—combined with cultural values that emphasize collectivism and strong societal expectations for corporate responsibility (Aruta & Paceño, 2021; Barral, 2024; Pauline et al., 2019). Malaysia also demonstrates a strong impact, likely supported by its mature regulatory infrastructure through the Bursa Malaysia Sustainability Framework and active government initiatives promoting ESG integration, which help firms align sustainability practices with performance objectives (Mohammad & Wasiuzzaman, 2021; Tang, 2023).

In contrast, Indonesia and Thailand show relatively weaker effects, possibly due to limited regulatory enforcement, emerging investor pressure, and less institutionalized stakeholder activism (Prisandani, 2022; Rahmaniati & Ekawati, 2024; Terdpaopong et al., 2025). Still, growing international scrutiny and evolving global standards may strengthen the influence of sustainability reporting in these countries over time. Singapore, despite its reputation for strong governance, records the weakest relationship—potentially reflecting a saturation point where sustainability disclosures are already expected and thus no longer generate significant performance differentials (Bansal et al., 2021; Barral, 2024; Chen, 2024).

The moderating effect of herding behavior reveals important distinctions in how firms translate sustainability reporting into performance outcomes. When herding is measured through capital structure conformity (MHR), leader firms—those whose financing decisions closely align with industry norms—demonstrate significantly stronger positive effects of sustainability reporting on ROA and Tobin’s Q than follower firms. This finding supports Hypothesis 7 and aligns with prior research (De Mendonca & Zhou, 2020; Do & Nguyen, 2020), highlighting the strategic value of financial consistency in amplifying the benefits of ESG practices. In contrast, no significant moderating effect is found when leader-follower classification is based solely on disclosure volume (SRDI), suggesting that behavioral alignment may be a more meaningful indicator of ESG integration than reporting intensity alone.

These findings align with institutional and signaling theories, which argue that organizations often adopt similar practices to gain legitimacy and reduce uncertainty (Bebbington et al., 2008; Clarkson et al., 2008; Dhaliwal et al., 2011). Firms that demonstrate financial discipline while pursuing sustainability are likely seen as more credible by investors and stakeholders, enhancing the signaling value of their ESG disclosures (Beyer et al., 2010). As Eccles et al. (2014) show, firms with integrated ESG strategies—not just high disclosure—tend to outperform peers in the long run. The observed leader firms may reflect this integration, using both financial and sustainability coherence as a competitive advantage.

Conversely, follower firms with inconsistent capital structures may engage in sustainability disclosure more reactively or mimetically, reducing the strategic depth and performance impact of their ESG efforts (Kusumawati, 2024; Zhao et al., 2025). This highlights the double-edged nature of herding: while it can accelerate ESG adoption across industries, it may also dilute its effectiveness if firms adopt sustainability practices superficially. For ESG to drive long-term value and climate resilience, firms must move beyond imitation and embed sustainability within core decision-making frameworks—a shift that regulators and investors should incentivize.

Collectively, these results underscore that sustainability reporting positively contributes to financial and market outcomes, but the magnitude and pathways vary across firm characteristics, countries, and behavioral dynamics. This highlights the need for nuanced regulatory and managerial strategies that account for contextual differences.

6. Conclusions

This study investigates how ESG disclosure—operationalized through sustainability reporting—relates to corporate financial performance and how herding behavior moderates this relationship among non-financial firms across five ASEAN countries. The results demonstrate that sustainability reporting significantly improves corporate financial performance as reflected in return on assets (ROA) and Tobin’s Q, though it does not yield a significant impact on net profit margin (NPM). Furthermore, the results also highlight that herding behavior, particularly when measured through capital structure alignment, moderates this relationship, with leader firms gaining more from sustainability efforts than followers. These outcomes emphasize the double-edged nature of herding: while it can accelerate ESG adoption, it may also dilute the strategic intent of climate action when driven by imitation. The study offers insights for advancing ESG finance as a mechanism to strengthen corporate climate resilience and long-term stakeholder value in emerging markets.

The study offers several practical implications for regulators, corporate strategists, and investors. For policymakers, the observed variations across countries suggest the need for tailored regulatory frameworks that not only enforce sustainability disclosure but also promote genuine climate-related action. In countries with weaker ESG-performance links, regulatory reform should move beyond compliance to incentivize meaningful, outcome-driven climate reporting.

For corporate leaders, the evidence underscores that sustainability reporting is most effective when embedded within a financially disciplined strategy. Firms that lead rather than follow are better positioned to convert ESG initiatives into long-term performance gains. This calls for greater integration of climate strategies into capital structure planning, risk management, and investment decisions. For investors, the findings highlight the importance of assessing not just the volume of ESG disclosure, but also the consistency of financial behavior and the authenticity of climate action, especially in emerging markets vulnerable to climate risks.

While this study provides valuable cross-country insights, several limitations should be noted. First, its focus on five ASEAN countries limits broader generalizability. Second, the data timeframe may not fully capture the delayed impacts of ESG activities, particularly regarding profitability. Third, although sustainability reporting was used as a proxy for ESG disclosure, it may not fully reflect firms’ environmental or social performance depth. Finally, while herding behavior was assessed using two models—disclosure-based (SRDI) and financial behavior-based (MHR)—the analysis was limited to leader-follower dynamics in sustainability reporting and capital structure. Future research could explore herding in climate-specific decisions, such as technology adoption or emissions-related investment behavior.

Future studies should consider expanding the geographic scope beyond ASEAN to assess whether similar dynamics between ESG disclosure, herding behavior, and corporate financial performance hold in different institutional contexts. Longitudinal designs would be beneficial to capture the long-term financial implications of sustainability initiatives, especially concerning profitability metrics like net profit margin. Broader ESG measurement frameworks—incorporating environmental performance data, governance quality, and actual climate-related actions—could provide a more holistic view of corporate sustainability. Additionally, exploring other forms of herding behavior, such as imitation in green technology adoption or responses to climate-related regulations, could deepen our understanding of behavioral influences on ESG integration. Sector-specific analyses, particularly in high-emission industries, may also offer insights into how strategic ESG alignment varies across business models and regulatory exposure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W. and J.K.W.; methodology, A.W. and A.Z.A.; software, A.Z.A.; validation, A.W., J.K.W., and A.Z.A.; formal analysis, A.W. and A.Z.A.; investigation, J.K.W.; resources, A.W.; data curation, A.Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.W. and J.K.W.; writing—review and editing, A.W. and A.Z.A.; visualization, A.Z.A.; supervision, A.W.; project administration, A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The financial and sustainability data used in this study were obtained from the Bloomberg Terminal, a subscription-based database. Due to licensing restrictions, the raw data cannot be shared publicly. However, detailed descriptions of variables, measurement approaches, and data processing methods are provided to ensure the reproducibility of results.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable insights and constructive feedback provided by academic colleagues and subject matter experts, whose thoughtful suggestions greatly contributed to the improvement of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agarwala, N.; Pareek, R.; Sahu, T. N. Do firm attributes impact CSR participation? Evidence from a developing economy. International Journal of Emerging Markets 2024, 19(12), 4526–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharon, D. Y. Uncertainty, Fear and Herding Behavior: Evidence from Size-Ranked Portfolios. Journal of Behavioral Finance 2021, 22(3), 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Wu, Q. Does herding behavior matter in investment management and perceived market efficiency? Evidence from an emerging market. Management Decision 2022, 60(8), 2148–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, A. A.; Houcine, A. Firms’ characteristics, corporate governance, and the adoption of sustainability reporting: evidence from Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 2024, 22(2), 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hawaj, A. Y.; Buallay, A. M. A worldwide sectorial analysis of sustainability reporting and its impact on firm performance. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 2022, 12(1), 62–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Natour, A. R.; Meqbel, R.; Kayed, S.; Zaidan, H. The Role of Sustainability Reporting in Reducing Information Asymmetry: The Case of Family-and Non-Family-Controlled Firms. In Sustainability; 2022; Vol. 14, Issue 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Abdelfettah, B. Financial Disclosure Information, Board of Directors, and Firm Characteristics among French CAC 40 Listed Firms. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 2019, 10(3), 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alodat, A. Y.; Salleh, Z.; Hashim, H. A.; Sulong, F. Sustainability disclosure and firms’ performance in a voluntary environment. Measuring Business Excellence 2024, 28(1), 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsahali, K. F.; Malagueño, R. An empirical study of sustainability reporting assurance: current trends and new insights. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change 2022, 18(5), 617–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, H. S. Sustainable Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) development of China and ASEAN in a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world. Global Policy 2024, 15(S6), 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, J. J. B. R.; Paceño, J. L. Social Responsibility Facilitates the Intergenerational Transmission of Attitudes Toward Green Purchasing in a Non-Western Country: Evidence from the Philippines. Ecopsychology 2021, 14(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, M.; Samad, T. A.; Bashir, H. A. The sustainability reporting-firm performance nexus: evidence from a threshold model. Journal of Global Responsibility 2021, 12(4), 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, M. A. A. The nexus between trade and investment, ESG, and SDG (No. 2024–28). PIDS Discussion Paper Series 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Larrinaga-González, C.; Moneva-Abadía, J. M. Legitimating reputation/the reputation of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 2008, 21(3), 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benameur, K. B.; Mostafa, M. M.; Hassanein, A.; Shariff, M. Z.; Al-Shattarat, W. Sustainability reporting scholarly research: a bibliometric review and a future research agenda. Management Review Quarterly 2024, 74(2), 823–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, A.; Cohen, D. A.; Lys, T. Z.; Walther, B. R. The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics 2010, 50(2), 296–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Tuli, S. Corporate attributes affecting sustainability reporting: an Indian perspective. International Journal of Law and Management 2017, 59(3), 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikhchandani, S.; Sharma, S. Herd Behavior in Financial Markets. IMF Staff Papers 2000, 47(3), 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, H.; Li, T.; Sun, Y. Board attributes and herding in corporate investment: evidence from Chinese-listed firms. The European Journal of Finance 2016, 22(4–6), 432–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N. M. P.; Rana, P.; Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering 2015, 32(1), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendea, G.; Pop, F. Herding behavior and financing decisions in Romania. Managerial Finance 2019, 45(6), 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A.; El Khoury, R.; Hamdan, A. Sustainability reporting in smart cities: A multidimensional performance measures. Cities 2021, 119, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Han, S.; Li, D.; Li, Y. Institutional herding and its price impact: Evidence from the corporate bond market. Journal of Financial Economics 2019, 131(1), 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, O. Industry herd behaviour in financing decision making. Journal of Economics and Business 2017, 94, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Market reaction to mandatory sustainability disclosures: evidence from Singapore. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 2024, 25(3), 748–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T. C.; Zheng, D. An empirical analysis of herd behavior in global stock markets. Journal of Banking and Finance 2010, 34(8), 1911–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H. B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: economic analysis and literature review. Review of Accounting Studies 2021, 26(3), 1176–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, R.; Bayne, L.; Birt, J. The impact of environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure on firm financial performance: evidence from Hong Kong. Asian Review of Accounting 2024, 32(1), 136–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G. L.; Feiner, A.; Viehs, M. From the stockholder to the stakeholder: How sustainability can drive financial outperformance. SSRN Electronic Journal 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P. M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G. D.; Vasvari, F. P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society 2008, 33(4), 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Garcia, J. A.; Garcia-Benau, M. A.; Garcia-Meca, E. Corporate governance and its implications for sustainability reporting quality in Latin American business groups. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 260, 121142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mendonca, T.; Zhou, Y. When companies improve the sustainability of the natural environment: A study of large U.S. companies. Business Strategy and the Environment 2020, 29(3), 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R. Determinants of corporate carbon disclosure: A step towards sustainability reporting. Borsa Istanbul Review 2022, 22(5), 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D. S.; Li, O. Z.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y. G. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. The Accounting Review 2011, 86(1), 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, B.; Keskin, A. İ.; Dincer, C. Nexus between Sustainability Reporting and Firm Performance: Considering Industry Groups, Accounting, and Market Measures. In Sustainability; 2023; Vol. 15, Issue 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, B.; Nguyen, N. The Links between Proactive Environmental Strategy, Competitive Advantages and Firm Performance: An Empirical Study in Vietnam. In Sustainability; 2020; Vol. 12, Issue 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R. G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Management Science 2014, 60(11), 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, F.; Hassapis, C.; Philippas, N. Investors’ fear and herding in the stock market. Applied Economics 2018, 50(34–35), 3654–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeoha, A. E. Firm versus industry financing structures in Nigeria. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 2011, 2(1), 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandella, P.; Sergi, B. S.; Sironi, E. Corporate social responsibility performance and the cost of capital in BRICS countries. The problem of selectivity using environmental, social and governance scores. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2023, 30(4), 1712–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farisyi, S.; Musadieq, M. A.; Utami, H. N.; Damayanti, C. R. A Systematic Literature Review: Determinants of Sustainability Reporting in Developing Countries. In Sustainability; 2022; Vol. 14, Issue 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, J. E. Making sustainability disclosure sustainable. Geo. LJ 2018, 107, 923–966. [Google Scholar]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 2015, 5(4), 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frynas, J. G.; Yamahaki, C. Corporate social responsibility: review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Business Ethics: A European Review 2016, 25(3), 258–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, P. J.; Christensen, L. J. Firm Size Matters: An Empirical Investigation of Organizational Size and Ownership on Sustainability-Related Behaviors. Business & Society 2011, 50(2), 315–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilakis, N.; Floros, C. ESG performance, herding behavior and stock market returns: evidence from Europe. Operational Research 2023, 23(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbel, A.; Snene, Y.; Frikha, W. Does herding behavior explain the contagion of the COVID-19 crisis? Review of Behavioral Finance 2023, 15(6), 889–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Githaiga, P. N.; Kosgei, J. K. Board characteristics and sustainability reporting: a case of listed firms in East Africa. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 2023, 23(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godha, A.; Jain, P. Sustainability Reporting Trend in Indian Companies as per GRI Framework: A Comparative Study. South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases 2015, 4(1), 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, N.; Warren, P. Climate risk disclosure and climate risk management in UK asset managers. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 2022, 14(3), 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRI. Consolidated set of GRI sustainability reporting standards 2020. 2021. Available online: www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards/resource-center/.

- Haladu, A.; Bin-Nashwan, S. A. The moderating effect of environmental agencies on firms’ sustainability reporting in Nigeria. Social Responsibility Journal 2022, 18(2), 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoyo, S.; Anas, S. The effect of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) on firm performance: the moderating role of country regulatory quality and government effectiveness in ASEAN. Cogent Business & Management 2024, 11(1), 2371071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wang, Q. The peer effect of corporate financial decisions around split share structure reform in China. Review of Financial Economics 2020, 38(3), 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, S.; Graham, M. Applying legitimacy theory to understand sustainability reporting behaviour within South African integrated reports. South African Journal of Accounting Research 2022, 36(2), 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongming, X.; Ahmed, B.; Hussain, A.; Rehman, A.; Ullah, I.; Khan, F. U. Sustainability Reporting and Firm Performance: The Demonstration of Pakistani Firms. Sage Open 2020, 10(3), 2158244020953180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate sustainability: A strategy? Harvard Business School Accounting & Management Unit Working Paper 2019, 19–065. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil, A.; Mohd Ghazali, N. A.; Puat Nelson, S. The influence of corporate governance structure on sustainability reporting in Malaysia. Social Responsibility Journal 2021, 17(8), 1251–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H. A. O.; Verardo, M. Does Herding Behavior Reveal Skill? An Analysis of Mutual Fund Performance. The Journal of Finance 2018, 73(5), 2229–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirasakuldech, B.; Emekter, R. Empirical Analysis of Investors’ Herding Behaviours during the Market Structural Changes and Crisis Events: Evidence from Thailand. Global Economic Review 2021, 50(2), 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. The Accounting Review 2016, 91(6), 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J. Corporate Sustainability Management and Its Market Benefits. In Sustainability; 2018; Vol. 10, Issue 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2012, 13(7), 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komalasari, P. T.; Asri, M.; Purwanto, B. M.; Setiyono, B. Herding behaviour in the capital market: What do we know and what is next? Review Quarterly 2022, 72(3), 745–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumari, R.; Poonia, A.; Kumar, R. Factors influencing corporate sustainability disclosure practices: empirical evidence from Indian National Stock Exchange. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 2023, 21(2), 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, N. D. Balancing Profit and Planet: How ESG Criteria Are Reshaping Capital Structure in Indonesia. Jurnal Mebis 2024, 4(2 SE-Articles), 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. T.; Raschke, R. L. Innovative sustainability and stakeholders’ shared understanding: The secret sauce to performance with a purpose. Journal of Business Research 2020, 108, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, A. Di; Sfodera, F.; Cucari, N.; Mattia, G.; Dezi, L. Sustainability reporting practices: an explorative analysis of luxury fashion brands. Management Decision 2023, 61(5), 1274–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, X.; Yu, D.; Tang, L. Peer effects and the mechanisms in corporate capital structure: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Oeconomia Copernicana 2023, 14(1), 295–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S. B.; Podsakoff, P. M.; Jarvis, C. B. The problem of measurement model misspecification in behavioral and organizational research and some recommended solutions. The Journal of Applied Psychology 2005, 90(4), 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, V.; Tashman, P.; Kostova, T. Escaping the iron cage: Liabilities of origin and CSR reporting of emerging market multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies 2017, 48(3), 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, F.; Aleca, O. E. Sustainability Reporting Based on GRI Standards within Organizations in Romania. Electronics (Switzerland) 2023, 12(3), 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misani, N. The convergence of corporate social responsibility practices. Management Research Review 2010, 33(7), 734–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, W. M. W.; Wasiuzzaman, S. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) disclosure, competitive advantage and performance of firms in Malaysia. Cleaner Environmental Systems 2021, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negera, M.; Alemu, T.; Hagos, F.; Haileslassie, A. Does financial inclusion enhance farmers’ resilience to climate change? Evidence from rural Ethiopia. Sustainable Development 2025, 33(2), 3008–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N.; Mahmood, M. Determinants of GRI-based sustainability reporting: evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 2020, 10(1), 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, M. F. Do Managers Herd when Choosing the Firm’s Capital Structure? Evidence from a Small European Economy; Universidade do Porto (Portugal), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pauline, K.; Ferrer, F. S.; Karen, G. Sustainability Initiatives of the SEC Philippines. Nomura Journal of Asian Capital Markets 2019, 4(1), 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Prashar, A. Moderating effects on sustainability reporting and firm performance relationships: a meta-analytical review. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2023, 72(4), 1154–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisandani, U. Y. Shareholder activism in Indonesia: revisiting shareholder rights implementation and future challenges. International Journal of Law and Management 2022, 64(2), 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmaniati, N. P. G.; Ekawati, E. The role of Indonesian regulators on the effectiveness of ESG implementation in improving firms’ non-financial performance. Cogent Business and Management 2024, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, D. Understanding environment, social and governance (ESG) factors as path toward ASEAN sustainable finance. APMBA (Asia Pacific Management and Business Application) 2019, 7(3), 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudyanto, A.; Siregar, S. V. The effect of stakeholder pressure and corporate governance on the sustainability report quality. International Journal of Ethics and Systems 2018, 34(2), 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Thanakijsombat, T.; Rind, A. A.; Sarang, A. A. A. Herding behavior in environmental orientation: A tale of emission, innovation and resource handling. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 444, 141251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreck, P.; Raithel, S. Corporate Social Performance, Firm Size, and Organizational Visibility: Distinct and Joint Effects on Voluntary Sustainability Reporting. Business & Society 2015, 57(4), 742–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M. U. D.; Shah, A.; Khan, S. U. Herding behavior in the Pakistan stock exchange: Some new insights. Research in International Business and Finance 2017, 42, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. S. H.; Khan, M. A.; Ahmed, M.; Meyer, D. F.; Oláh, J. A Micro-Level Evidence of how Investor and Manager Herding Behavior Influence the Firm Financial Performance. Sage Open 2024, 14(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. S. H.; Khan, M. A.; Meyer, N.; Meyer, D. F.; Oláh, J. Does herding bias drive the firm value? Evidence from the Chinese equity market. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2019, 11(20), 5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoni, L.; Bini, L.; Bellucci, M. Effects of social, environmental, and institutional factors on sustainability report assurance: evidence from European countries. Meditari Accountancy Research 2020, 28(6), 1059–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1974, 36(2), 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnapali, R. Consequences of corporate sustainability reporting: evidence from an emerging market. International Journal of Law and Management 2020, 62(3), 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K. H. D. A Review of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Regulatory Frameworks: Their Implications on Malaysia. Tropical Aquatic and Soil Pollution 2023, 3(2), 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terdpaopong, K.; Nguyen, T. T. H.; Yang, Y. Financial Determinants of ESG Disclosures: An Empirical Analysis of Thailand. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Research in Management and Technovation; Nguyen, N. T. H., Santos, J. A. C., Solanki, V. K., Mai, A. N., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore, 2025; pp. 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upaa, J.; Iorlaha, M. Sustainability Disclosure and Information Asymmetry of Listed Industrial Companies in Nigeria. International Journal of Accounting, Finance and Risk Management 2023, 8(4), 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieito, J. P.; Espinosa, C.; Wong, W.-K.; Batmunkh, M.-U.; Choijil, E.; Hussien, M. Herding behavior in integrated financial markets: the case of MILA. International Journal of Emerging Markets 2024, 19(11), 3801–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakibi, A.; Ntayi, J.; Nkote, I.; Tumwine, S.; Nsereko, I.; Ngoma, M. Self-organization, networks and sustainable innovations in microfinance institutions: Does organizational resilience matter? IIMBG Journal of Sustainable Business and Innovation 2024, 2(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yu, S.; Mei, M.; Yang, X.; Peng, G.; Lv, B. ESG Performance and Corporate Resilience: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Capital Allocation Efficiency Perspective. In Sustainability; 2023; Vol. 15, Issue 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Unlocking the link between company attributes and sustainability accounting in Shanghai: firm traits driving corporate transparency and stakeholder responsiveness. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2023, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Pan, H.; Feng, Y.; Du, S. How do ESG practices create value for businesses? Research review and prospects. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 2024, 15(5), 1155–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Herding behavior and the dynamics of ESG performance in the European banking industry. Finance Research Letters 2023, 58, 104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, I. Sustainability and financial performance relationship: international evidence. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 2021, 17(3), 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, N. M. M. Sustainability reports and their impact on firm value: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Management and Sustainability 2023, 12(2 SE-Articles), 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M. Do Oil Prices and Financial Indicators Drive the Herding Behavior in Commodity Markets? Journal of Behavioral Finance 2022, 23(1), 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Ngan, S. L.; Jamil, A. H.; Salleh, M. F.; Yusoff, W. S. Peer Effects on ESG Disclosure: Drivers and Implications for Sustainable Corporate Governance. In Sustainability; 2025; Vol. 17, Issue 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).