1. Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) comprises ~ 15% of all newly diagnosed leukemias in adults. The Bcr-Abl1 fusion gene encoding a tyrosine kinase that typifies CML, leads to an uncontrolled proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis in progenitor cells within the bone marrow. This chimeric protein is a part of the newly formed Philadelphia chromosome, expressed as a fusion between the Abelson (

Abl) tyrosine kinase gene at chromosome 9 and the break point cluster (

Bcr) gene at chromosome 22. The resulting chimeric oncogene is a constitutively active Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase [

1].

Oxidative stress is among the downstream signalling pathways promoted by BCR-ABL1 [

2].

Imatinib mesylate (IM), the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved for CML, blocks the activity of the BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase by hindering its ATP-binding site and consequently induces apoptosis of CML cells [

3]. Cells exposed to IM undergo rapid apoptosis, which in most patients manifests as a complete hematologic response. However, numerous leukemic cells from the hematopoietic stem cell population are resistant to IM therapy and their survival does not seem to be dependent solely on BCR-ABL1 activity [

4]. Recent studies point to multiple factors that can contribute to the development of resistance to TKIs including IM [

5]. IM resistance may stem from over expression or amplification of the Bcr-Abl gene and point mutations within the Bcr-Abl kinase domain that interfere with imatinib binding. Additionally, alterations in drug influx and efflux or activation of Bcr-Abl independent pathways may lead to IM resistance [

5].

Oxidative stress has been linked to CML in several levels. BCR-ABL1 induces the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in hematopoietic cells leading to oxidative stress which is involved in its anti-apoptotic effects. On the other hand, oxidative stress damages DNA and interferes with DNA repair, leading to genomic instability which may promote apoptosis [

6,

7,

8]. The status of oxidative stress in CML was also linked to the resistance of the neoplastic cells to IM and its derivatives [

9].

Secreted by practically all cell types, extracellular vesicles (EVs) differ in their biogenesis, release pathways, size, content, and function. The three main subtypes of EVs are apoptotic bodies, microvesicles, and exosomes. Originated from early endosomes and processed into multivesicular bodies, exosomes are 30–150 nm in diameter. During the development of leukemia, leukemic cell-derived exosomes are implicated in the transformation of the normal hematopoietic niche toward a malignant tumor-supportive microenvironment which contributes to the progression of the malignancy as well as the drug resistance [

10]. A number of recent studies have revealed that exosomes or EVs are secreted by CML cells and demonstrated their capability to induce the formation of new vessels, suggesting their role in angiogenesis in the bone marrow of patients with CML [

11,

12]. These include micro RNA such as miR-214, miR29a, miR01, miR126, and miR-320; long noncoding RNA including MALAT1, MANTIS and proteins such as NFkB and STAT3 [

13].

We have planned the described study in light of the need to deepen our understanding about development of resistance to IM in patients with CML and the increasing knowledge about exosomes and their contribution to drug resistance. For this purpose, we have studied the CML model cell line, K-562, in our study. We aimed at deciphering the putative role of EVs in conferring IM resistance to CML, in the presence of oxidative stress using a CML cell line model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

CML cell line, s-K562, sensitive to IM, was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (biological industries) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel). Cells were grown in a 37oC incubator in the presence of 5% CO2 and 90% humidity for 72 hours. CML human cell line, r-K562, resistant to IM, was purchased from the ATCC (ATCC CRL-3344) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (biological industries) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) and 1-2μM IM.

2.2. EVs Isolation

2-4x108 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% EVs free FBS, 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel). 24-72 hours later the growth media was collected and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 1,000g to remove contaminating cells. Then the supernatant was further centrifuged for 10 minutes at 2,000g to pellet more cell debris. The supernatant was then centrifuged once more for 30 minutes at 10,000g at 4oC. Afterwards, the supernatant was filtered by a 0.22μm filter and then ultracentrifuged for 2 hours at 110,000g at 4oC. Subsequently, the supernatant was removed and the pellets were washed with PBS by ultracentrifugation for 2 hours at 110,000g at 4oC. The upper liquid phase was removed and the pellets were immersed in 700μl PBS and kept at -80oC. To prepare EVs free FBS, FBS was centrifuged at the ultracentrifugation at 100,000g, 4oC for 18 hours and the supernatant was collected.

2.3. Characterization of EVs s

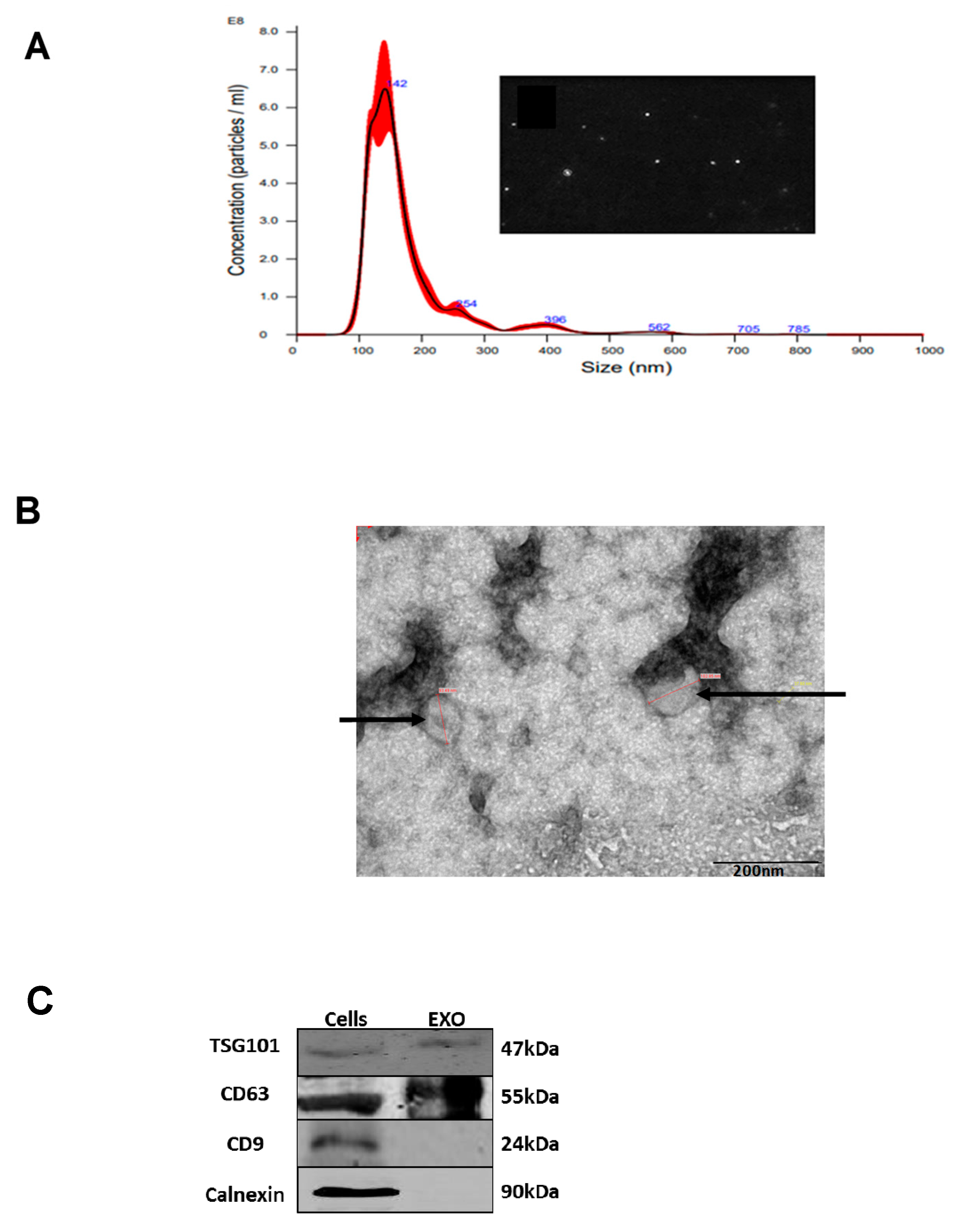

EVs were characterized by using Nano-Sight Tracking Analysis (NTA) and electron microscopy.

2.4. Nano-Sight Tracking Analysis (NTA)

EVs were quantified by NTA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Malvren Panalytical, Cambridge UK). Briefly, samples were diluted 1:100 in particle-free PBS (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) and analyzed under constant flow conditions at 25oC. Camera level was set to 13, number of repeats: 5X60sec and dilution of samples was usually 1:100.

2.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

We loaded 3μL of EVs extract on a glow discharged lacey grids (EmiTech K100 labtech, Sussex, UK) that were blotted and plunged into liquid ethane using a Gatan CP3 automated plunger. The grids were subsequently stored in liquid nitrogen until use. Frozen specimens (samples with EVs embedded in vitreous ice) were transferred to Gatan 914 cryo-holder and maintained at temperatures below −176°C inside the microscope. We inspected the samples with a Tecnai G2 microscope (Thermo Fisher, MA, USA). This instrument has an acceleration voltage of 120 kV and is equipped with a cryobox decontaminator. Images were taken using Digital Micrograph with a Mulitiscan Camera model 794 (Gatan, CA, USA).

2.6. Western Immunoblotting Analysis

Characterization of the presence of exosomal markers on the isolated EVs was determined by Western blotting using antibodies against well-characterized EV protein markers: TSG101, CD63, CD9, and calnexin. Protein concentration of the isolated EVs was determined by using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). 50μg of protein was subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then hybridized for 16h at 4°C with antibodies against CD63, CD9 (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-TSG101 and calnexin (1:500, Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA). On the following day, the membrane was subjected to fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies. Visualization was performed using the Odyssey analysis software 6.0 (Odyssey IR imaging system; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA).

2.7. Proliferation Assay

Proliferation was assessed by the Trypan blue exclusion staining (Biological Industries). Trypan blue was mixed in 1:10 ratio with treated suspended cells and counted by using Countess (automated cell counter, Invitrogen, USA). Live cells stayed unstained while dead cells assimilated the dye (total cell count was deduced from the live and dead cells). Each time 100-200 cells were counted twice and the results were plotted accordingly. The relatively small standard error means reflect the accuracy of the method.

2.8. RNA Extraction

RNA extraction from cells was performed by using the EZ-RNA II Isolation Kit reagent (Biological Industries Beit Haemek, Israel) according to provided manual instructions. Briefly, the membrane of the cells was lysed with guanidine thiocyanate detergent solution, followed by organic extraction of phenol-chloroform and alcohol precipitation of the RNA.

2.9. RNA Quantification

RNA concentrations were quantified by using the Nano-Drop spectrophotometer with the ND-1000 software and by the Qubit-2 device (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA & Canada).

2.10. Cell Viability

Assessment of cell viability was done by the WST-1 Cell Proliferation Reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Cells were seeded in a 96 well plate and incubated with the WST-1 reagent for 0.5 - 4 hours. The activity of mitochondrial enzymes reflecting cells viability was followed by a colorimetric assay based on the enzymatic ability to cleave a formazan dye. The levels of the obtained color were quantified by using a scanning multi-well spectrophotometer 405 nm (“Sunrise” ELISA, Tecan Group AG, Salzburg, Austria) and the results were calculated relative to the control results.

2.11. Exposure of Cells to Proliferative Stresses

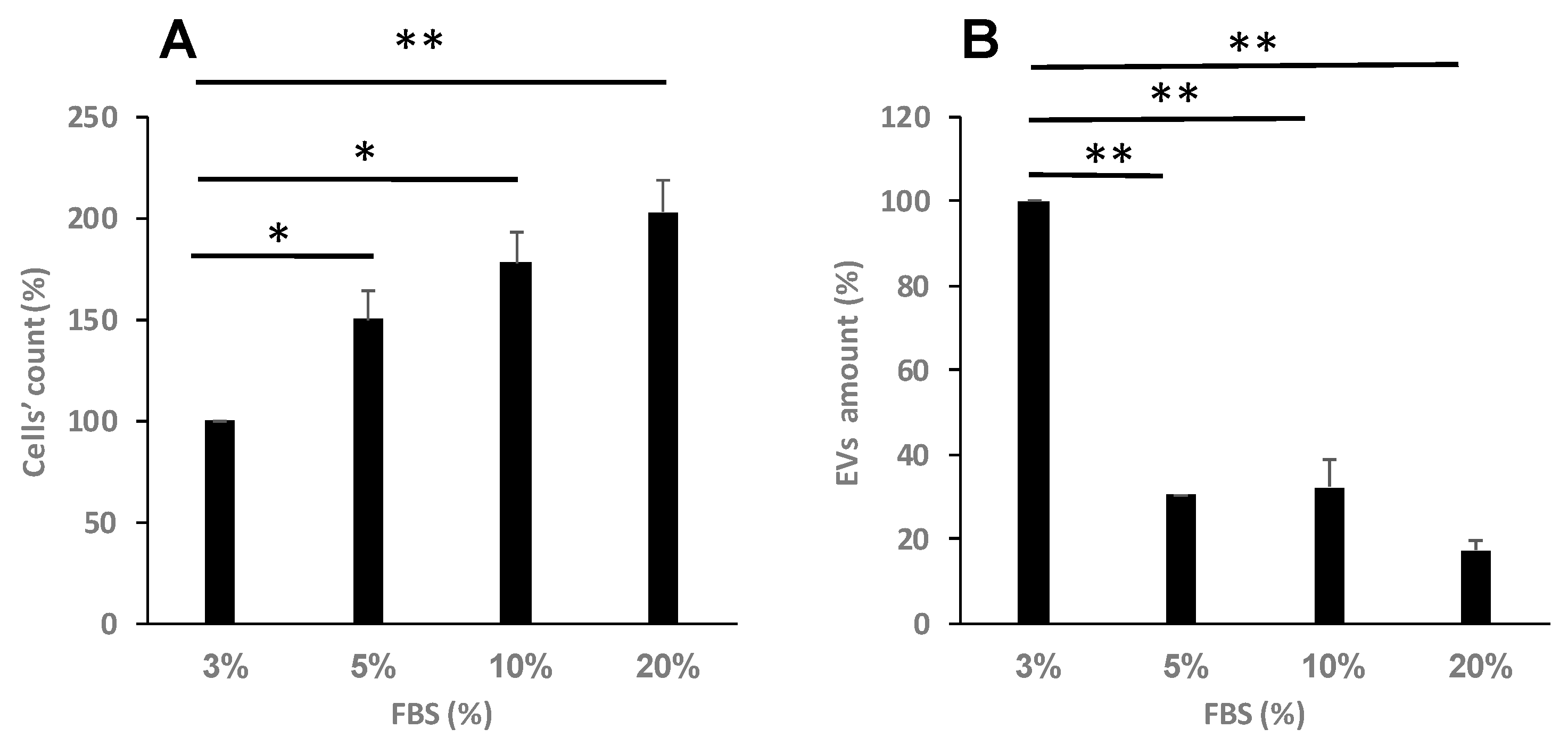

The presence of various FBS concentrations in the cells’ growth medium affects their growth rate. To mimic a higher growth rate, we exposed the cells to various FBS concentrations (2.5-20%) and assess their growth rate by the above-mentioned methods.

2.12. Exposure of the cells to oxidative stress

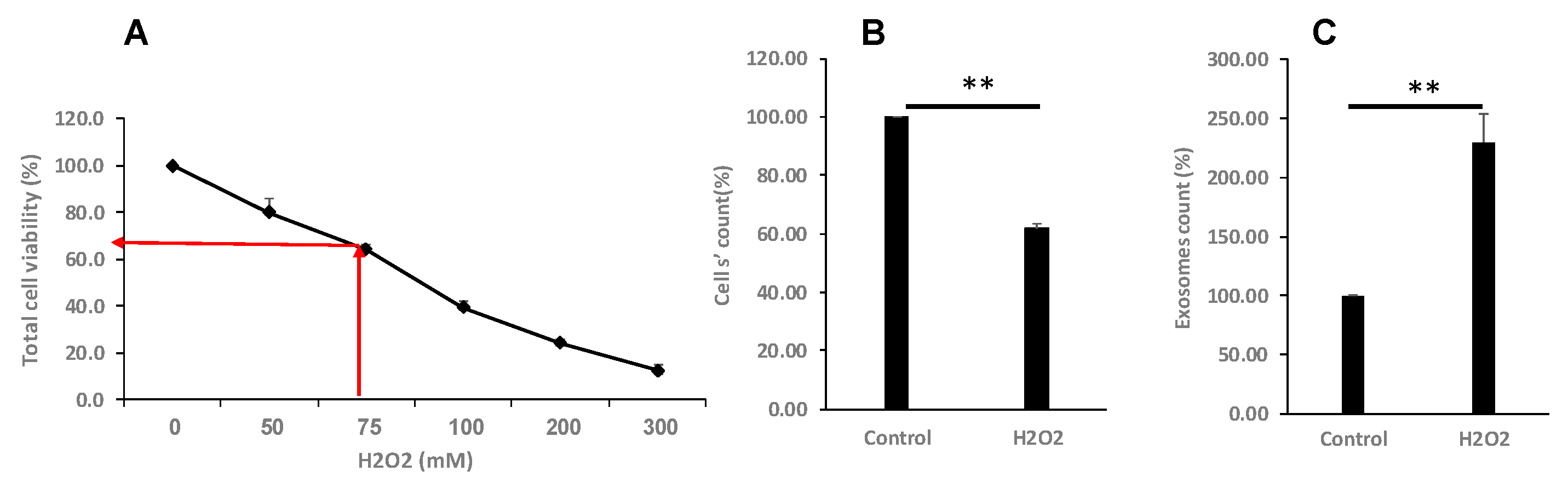

Exposure to hydrogen peroxide was used to apply an oxidative damage/stress on the cells. We exposed our cells to various concentrations of H2O2 and selected the concentration that eliminated about 50% of the cells.

2.13. Evaluation of EVs s Uptake

In order to follow EVs uptake by K562 cells, 1×106 cells/ml per well were plated in 24-well culture plate, resuspended in EVs depleted RPMI media and incubated with FM 1-43- labeled EVs in different concentrations and time periods. The FM-1-34 manufacturer’s protocol was performed as follows: 700μL of exosomes were incubated with 100μg of ready to use FM-1-43 dye for 10 minutes in the dark. Than the mixture was washed with PBS by using ultracentrifugation for two hours at 110,000 RCF. The pellet was resuspended in 700mL of PBS and kept until used under light protection conditions.

K562 cells without EVs served as control. To determine the efficiency of the EVs uptake by cells 24 hours post EVs exposure, the cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Validation that the dye remains stably associated with our EVs throughout the extended experimental timeframe was executed up to 96 hours. The percentage of K562 cells that have taken up the EVs and were FM-1-43 labeled was evaluated by following the FL-2 channel. Potential artifacts from dye transfer to cellular membranes independent of EV internalization was monitored by analyzing a control sample with cells that were not exposed to EVs but only to the dye itself. To exclude nonviable cells from the analysis of flow cytometry, 7-AAD (7-Aminoactinomycin D) nucleic acid dye was used (Tonbo Bioscience, California, USA).

2.14. cDNA Formation

Total RNA that was extracted from cells and EVs was reverse transcribed by using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystem, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1000 ng of template RNA was added to 10μL reaction mixture containing dNTP’s, random primers, RNase inhibitor, reaction buffer and a reverse transcriptase (RT). The incubation steps included 10 minutes at 25oC followed by 120 minutes at 37oC and terminated by a heating step at 85oC for 5 minutes.

2.15. Quantitative Real Time PCR (Q-RT-PCR:

Q-RT-PCR was performed to measure the expression of the NRF2 gene. Reactions were carried out by using the PCRbio Fast Blue Mix (PCR Biosystems, London, UK), FAM labelled primers were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA USA) and the reaction conditions were: 950C for 2min followed by 40 cycles of 95oC for 5sec and 600C for 20sec. Reactions were run and analyzed in the StepOne device (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

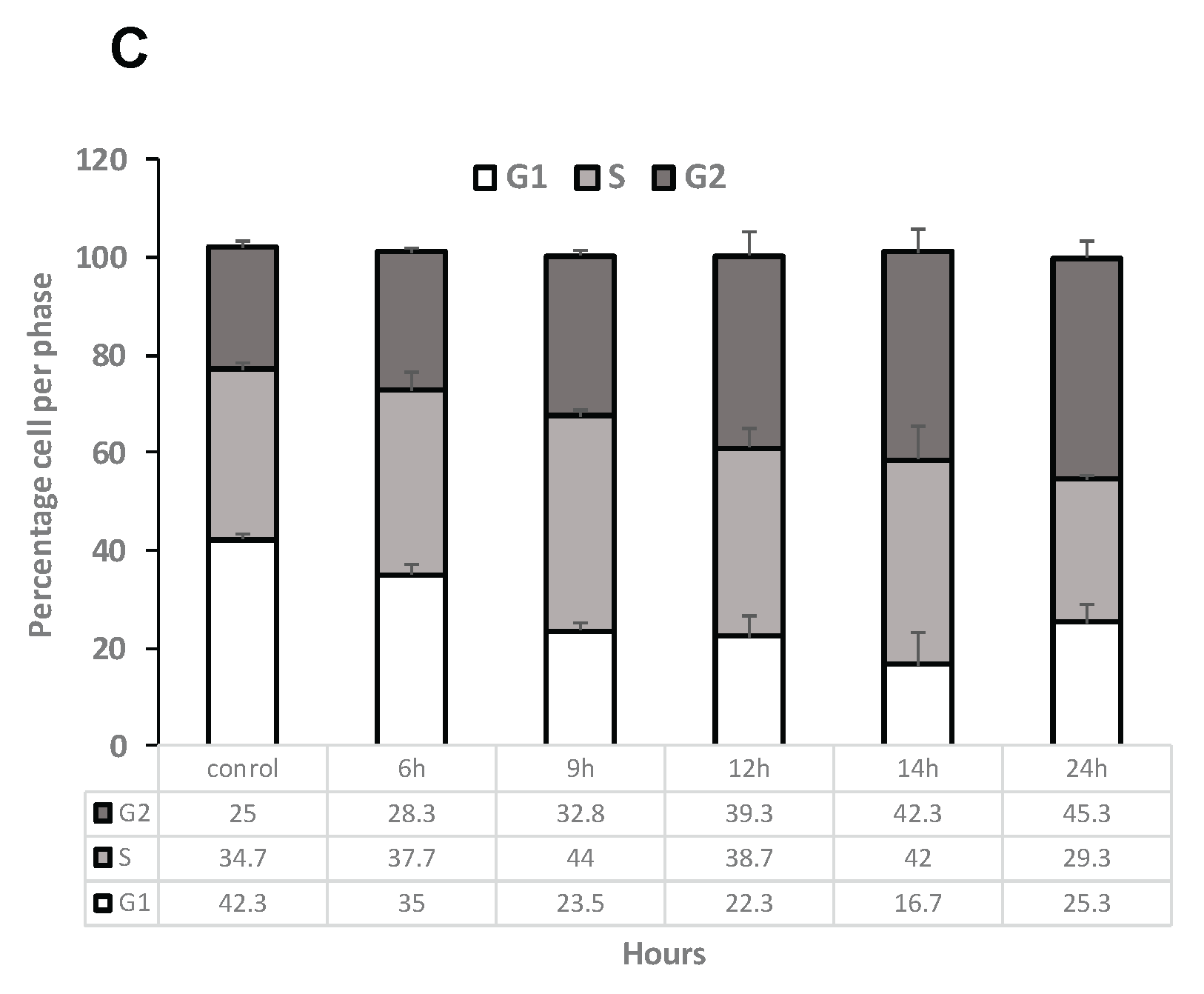

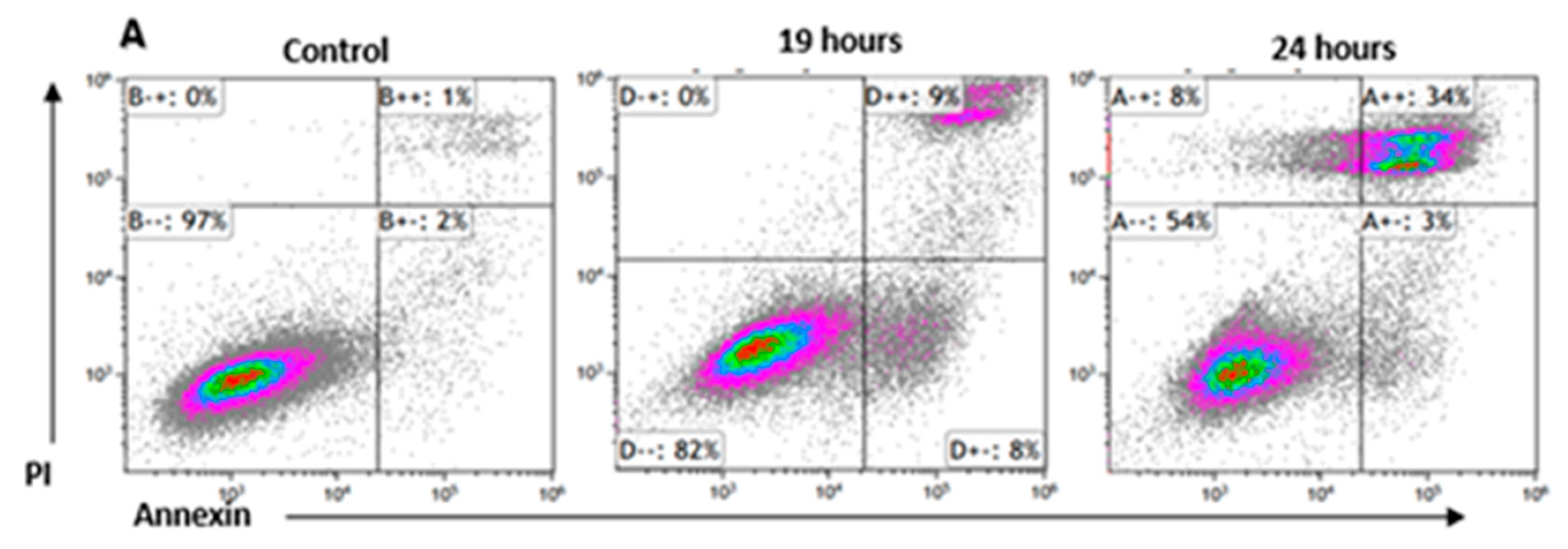

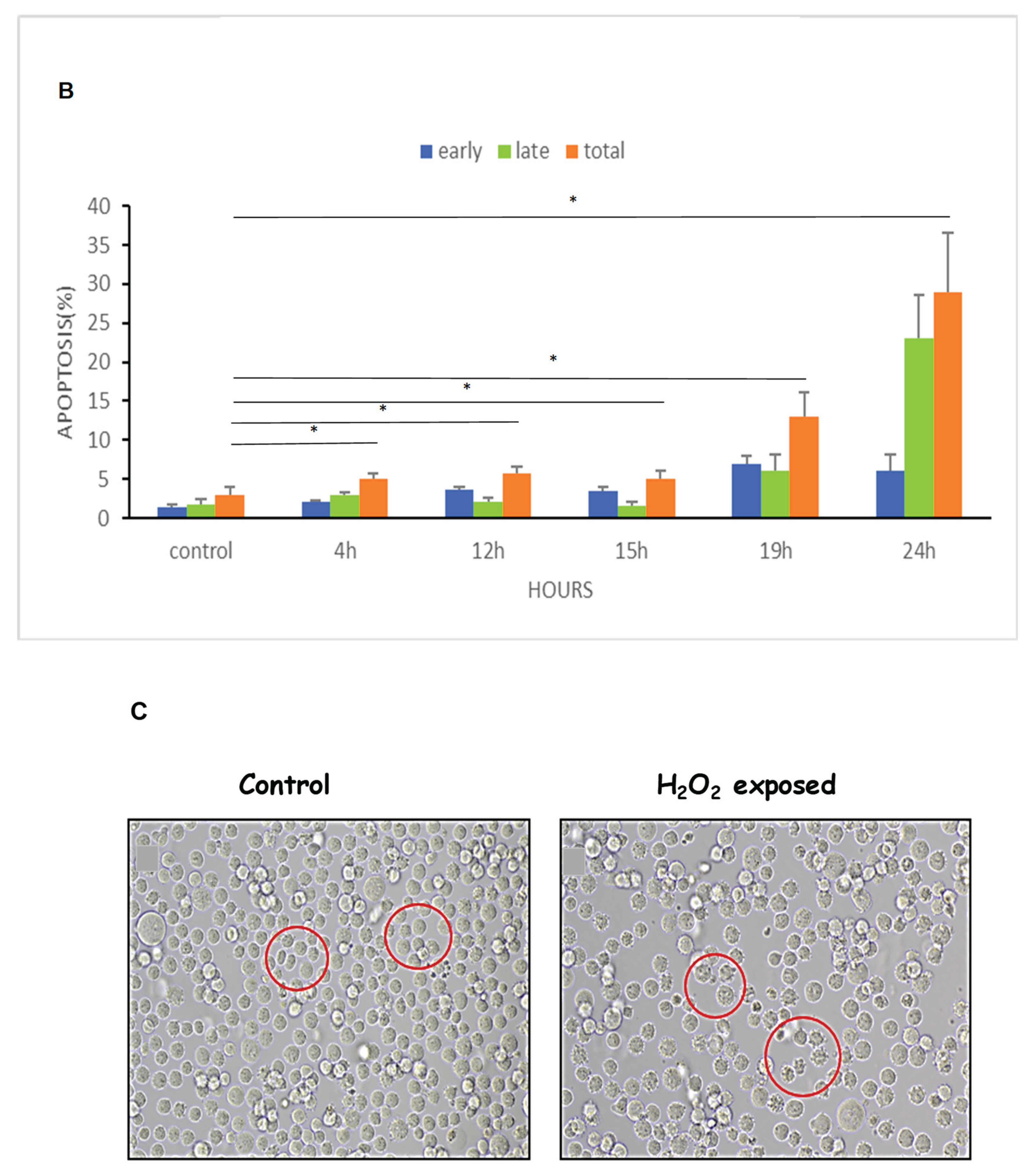

2.16. Apoptotic Cell Death Assay

Apoptotic cell death of CML cells that were exposed to H2O2 for different times periods (0,6,9,12,14 and 24 hours), was evaluated by Annexin V and PI staining by using the MEBCYTO® Apoptosis Kit (MBL, Nagoya, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Briefly, K562 cells in 6-well plates were cultured with H2O2 for 24 hours and collected by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min and resuspended with 90μL BB buffer (Binding Buffer), then cells were incubated with 10 µl Annexin V-FITC and 5µl PI (Propidium Iodide) for 15 min at RT in dark. Fluorescent cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and the data were analyzed using Kaluza Acquisition Software.

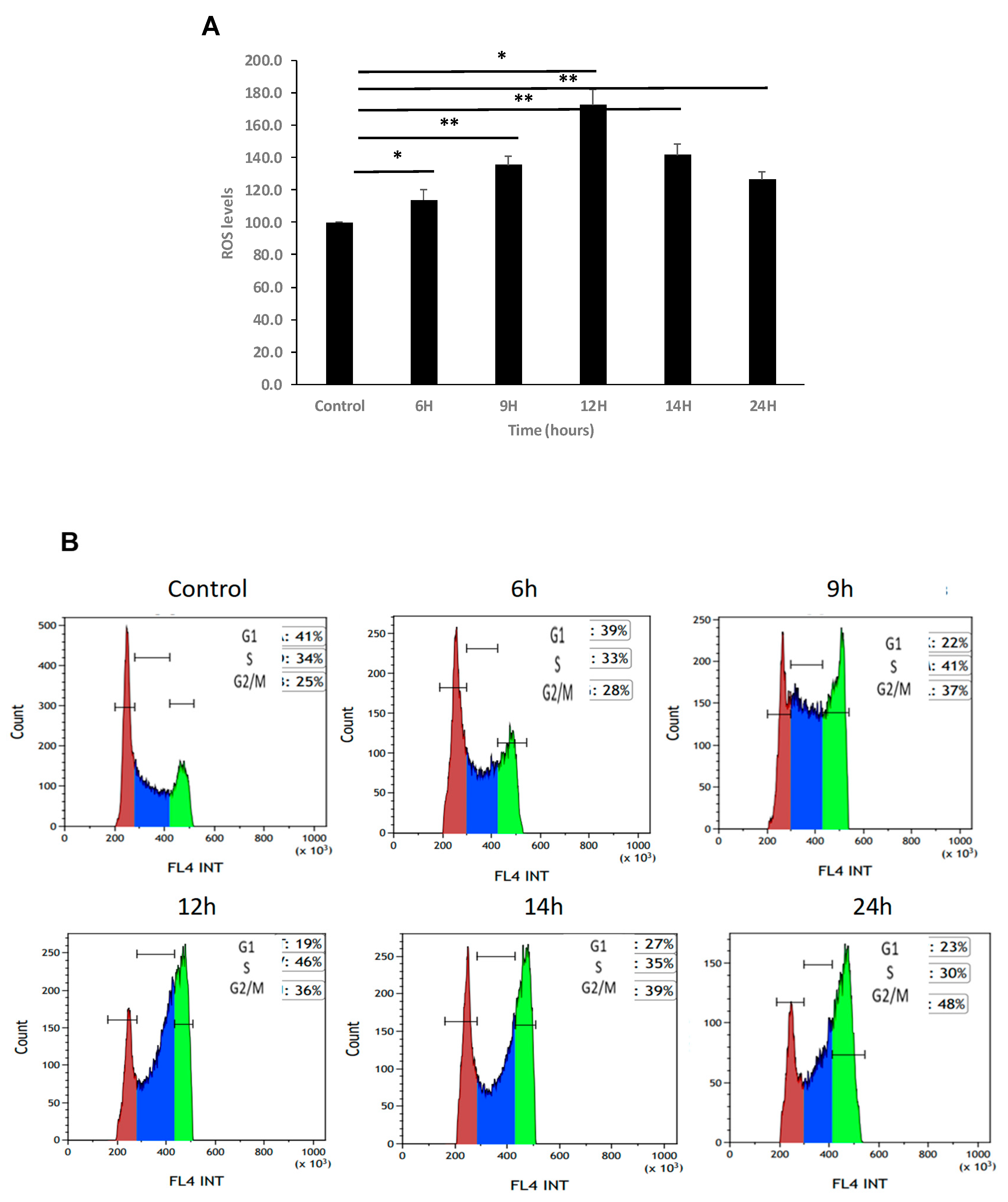

2.17. Cell Cycle Analysis by Flow Cytometry

The cell cycle status of the various samples was analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were processed by standard methods using propidium iodide staining of the DNA. Briefly, after cells were cultured in 6-well culture plate and exposed to H2O2 for various times periods (0,6,9,12,14 and 24 hours), the cells were washed by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min at 4oC, resuspended in 5ml cold PBS and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 min at 4oC. Cells were subsequently pelleted and fixed by adding 4.5ml 70% cold ethanol dropwise to 0.5ml cold PBS, with gentle vortexing. The cells were then incubated for >2 hours at -20oC. Cells were then washed by PBS and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes 4oC. Staining with propidium iodide (P4170, Sigma Aldrich) was conducted just prior to flow cytometry. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 0.5 ml PBS containing 0.025 ml of PI (50μg/ml) in PBS and 5μl of 100 mg/ml DNase-free RNase (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Cells were then incubated at 37oC for 15 minutes. Samples were analyzed on a Beckman-Coulter Epics XL-MCL apparatus. The parameters were adjusted for the measurement of single cells using the forward and side scatter plots. Data analysis was performed using Kaluza Acquisition Software (Beckman Coulter International SA, Switzerland).

2.18. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) by Flow Cytometry

ROS content of K562 cells were determined by using the 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate assay (D6883-SIGMA). After 0, 6, 9, 12, 14 and 24 hours of cells cultured with H2O2, cells were diluted with 10 μM DCFH-DA and incubated for 30 min at 37oC in the dark. Then the cells were collected and washed twice with PBS and resuspended in 1 mL of PBS. ROS was detected by flow cytometry (FACS Calibur, BD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.19. EVs and Cell Co-Cultivation

The K562 cells were co-cultured with either r-K562-derived or K562- EVs for 24 hours in a 96-well plate at 37oC, and then treated with IM (1, 2µM) for 24 and 48 hours. Cell viability was measured using the WST-1 assay as described previously. As negative controls we used cells without EVs and IM treatment.

2.20. Statistical Analysis

Data is presented as average + standard error for all experiments. Statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS 29 software version.

4. Discussion

Although the treatment and prognosis of CML have markedly improved since the development of TKIs, not all patients with CML respond well. During the progression of leukemia, exosomes or EVs secreted by the neoplastic cells may increase the aggressiveness of the disease by upregulating the proliferation of the leukemic cells, promoting angiogenesis and inhibiting hematopoiesis. Additionally, EVs are involved in providing resistance to drugs in general and to anti- cancer drugs in particular [

21,

22,

23,

24].

In light of the need to clarify the mechanisms contributing to development of resistance to TKI’s on the one hand and the altered metabolism of oxidative stress imposed by IM on the other hand, we designed our study focusing on the putative role of oxidative stress in conferring resistant to the drug through EVs shuttling. EVs shuttling was chosen based on several studies showing their role in cellular response to oxidative stress [

25,

26,

27].

As expected, our study demonstrated that ROS (imposed by H

2O

2) may exerted significant inhibition of cell proliferation in a dose- and a time-dependent manner. Interestingly, the surviving cells released more EVs per cell. Similarly, proliferative stress induced by decreasing the concentrations of FBS in the growth media of the cells also induced decreased cellular proliferation and increased the number of EVs secretion per cell. These cellular responses are in line with previous studies showing that the quality and quantity of extracellular vesicles vary depending on the physiological status of the mother cells [

26], which stems from environmental stresses such as oxidative stress and heat [

27,

28,

29].

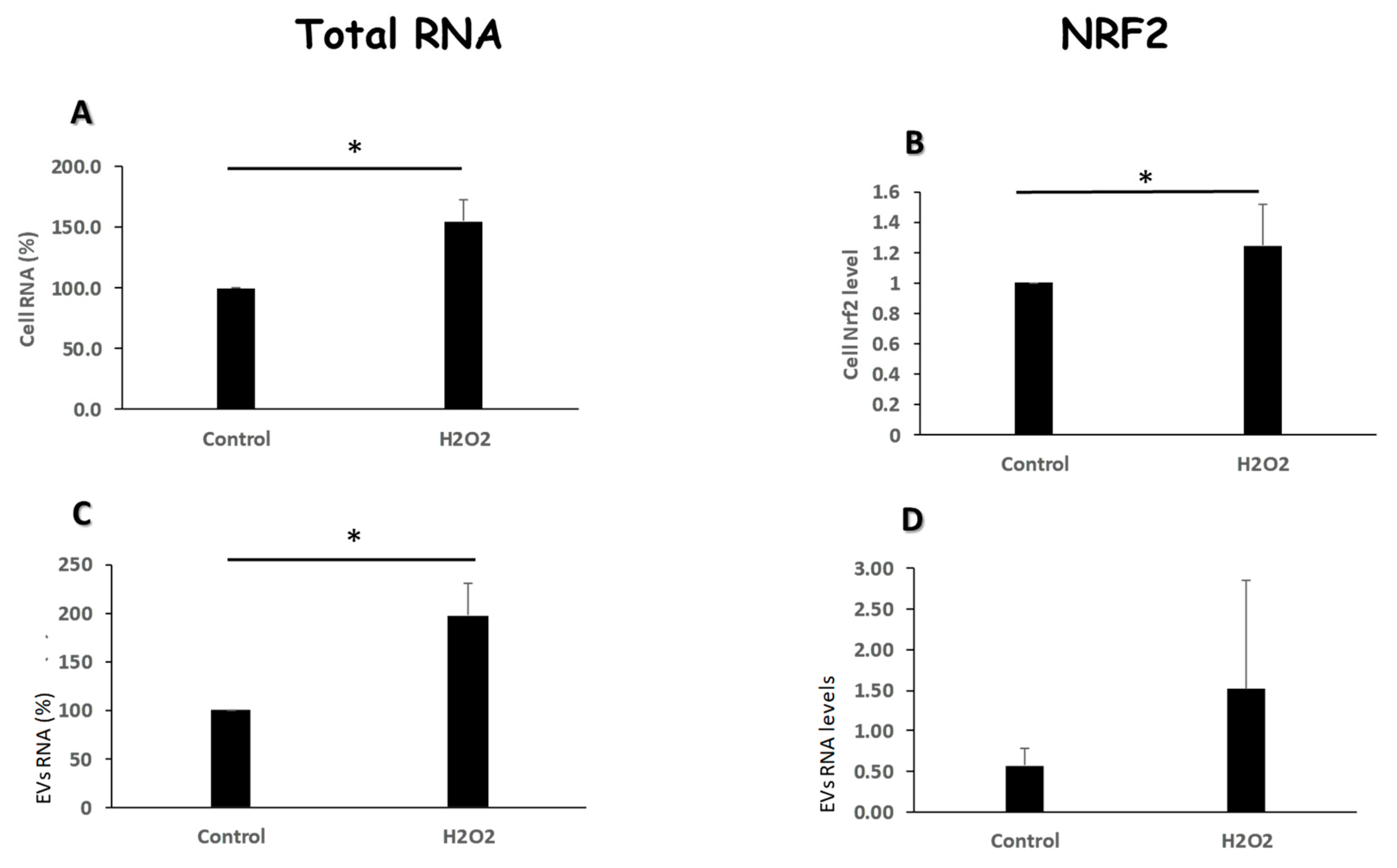

Interestingly, EVs released under stress conditions differed in their RNA levels compared to those released from cells growing under normal conditions. Oxidative stress induced the engulfment of bigger amount of RNA in the exposed cells’ EVs. Differential protein and RNA content in EVs released from cells exposed to stress conditions has previously been reported [

30].

The

Nrf2 gene product is implicated in protecting cells from oxidative stress [

31]. Whereas the exposed cells increased the levels of the

Nrf2 gene expression in response to oxidative insult, their secreted EVs did not demonstrate a similar increase. This difference serves as an example for the active engulfment of molecules into EVs, in this case, the presence of the gene transcripts in the cells but not in their cognate EVs. Our results suggest that at least on the transcriptional level,

Nrf2 is probably not involved in conferring any protection from oxidative stress to other K562 cells in our setting. This result contrasts with other studies [

31], demonstrating an increase of the expression of the

Nrf2 gene in response to oxidative insult in cells and their released EVs. As the mechanism of molecular packaging into EVs is far from being elucidated, it may also vary among different cellular contexts.

Oxidative exposure promoted morphological changes typical of apoptotic cell death of our cells, as previously reported [

32,

33]. Apoptosis was shown to be the result of the accumulation of ROS which damaged DNA, lipids and proteins. In agreement with this, our data showed that under environmental stress, ROS levels increased markedly, probably causing damage to cell structure and finally inducing apoptosis. Moreover, we detected a dose dependent arrest in the G2 phase of K562 cell cycle by H

2O

2. The result of this analysis suggests that inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest may be a key mechanism by which H

2O

2 inhibits s-K562 cell proliferation.

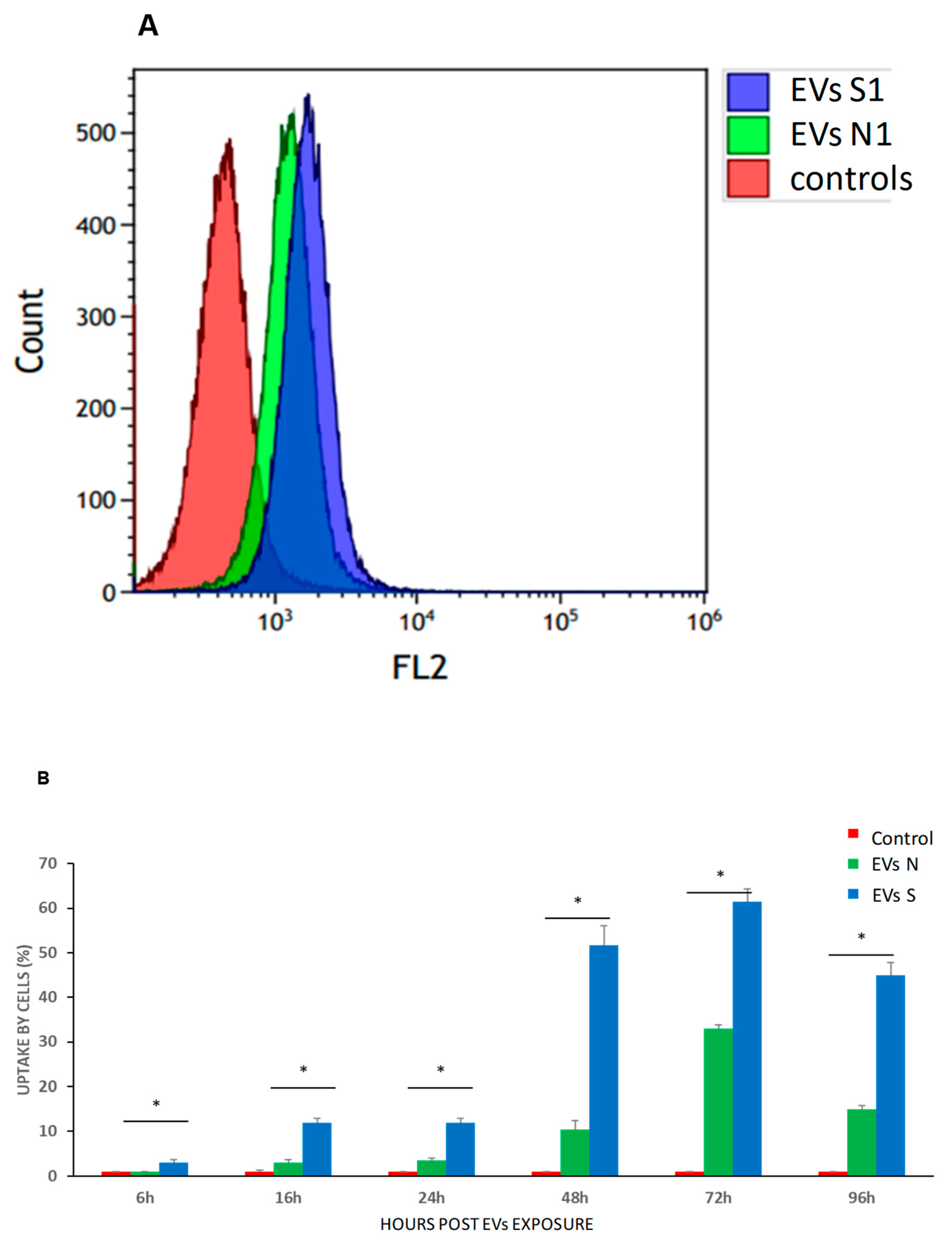

Another effect of oxidative stress was observed while assessing EVs uptake by intact K562 cells. s-K562-derived EVs growing under oxidative stress (EVs-S) were taken up rapidly and preferentially compared to EVs secreted from the control cells growing under normal conditions (EVs-N). Along these lines, Mutschelknaus et al. reported that radiation increases EVs release and uptake in head and neck squamous carcinoma cells, although the underlying process remained unclear [

34]. Another study showed that the uptake of EVs by hepatocellular carcinoma cells was much more efficient than the uptake of the same EVs by normal liver cells [

35].

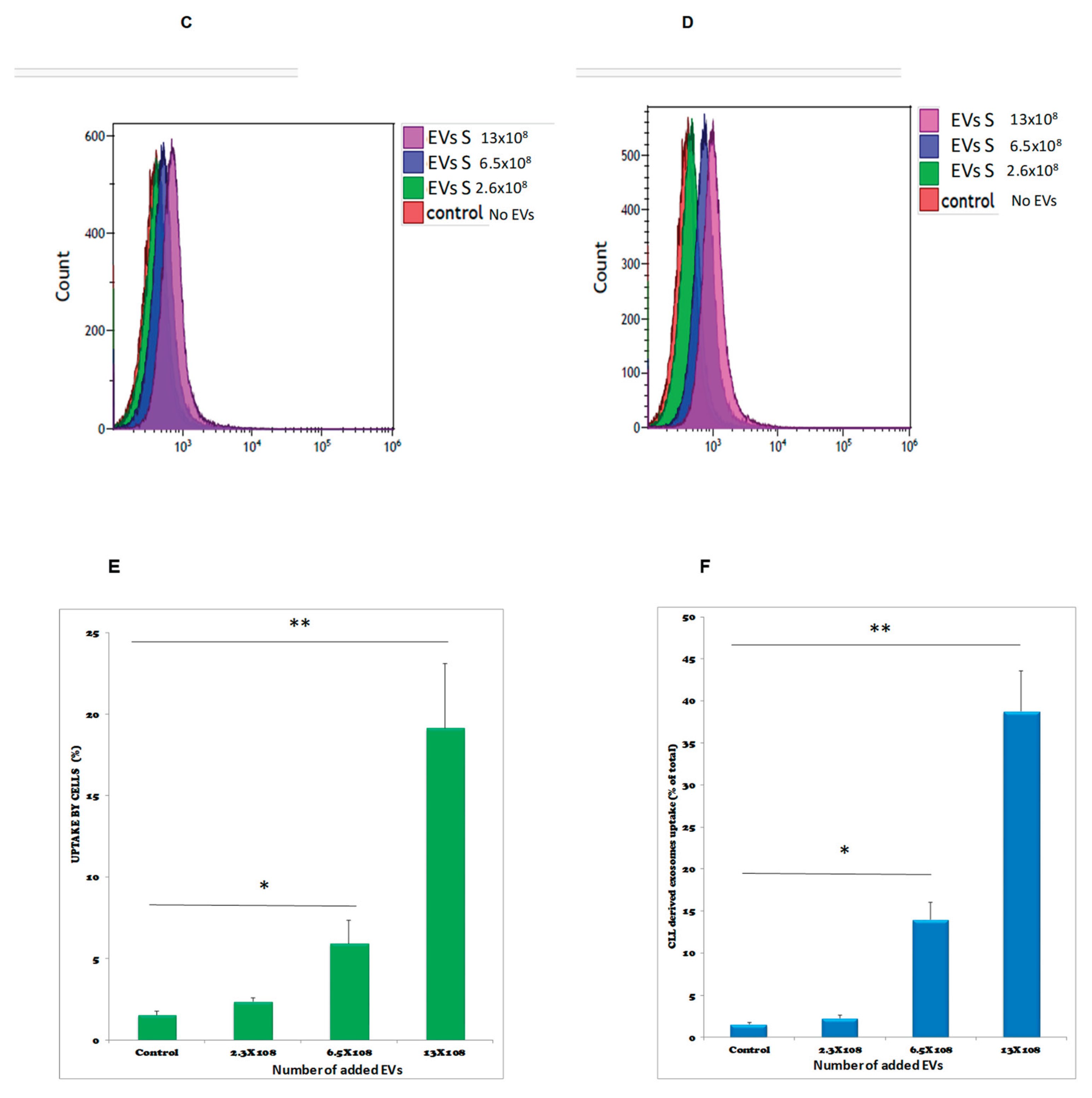

To elucidate the putative protective effects of our EVs on oxidative stress exposed cells we have measured the proliferation of these cells in our setting under these conditions. We provide evidence that s-K562-derived EVs exposed to oxidative stress increased the proliferation of intact s-K562 cells, however when the intact recipient K562 cells were exposed to oxidative stress this effect was not obtained. Previous studies have reported that CML EVs trigger an anti-apoptotic phenotype in the recipient cells. These studies suggested that the secretion of EVs by CML cells could have potentially contributed to the progression of leukemia through triggering of an autocrine loop, thus representing a possible target for new therapies [

36,

37,

38]. Our results may add another feature regarding the role of EVs-S in CML progression.

IM, the first TKI treatment for CML, is implicated in changes of the neoplastic cells’ oxidative environment, which may impose resistance to the treated cells [

39]. Assessing the effects of H

2O

2 derived EVs on the response to IM- exposed, both sensitive and resistant cells, revealed several interesting findings.

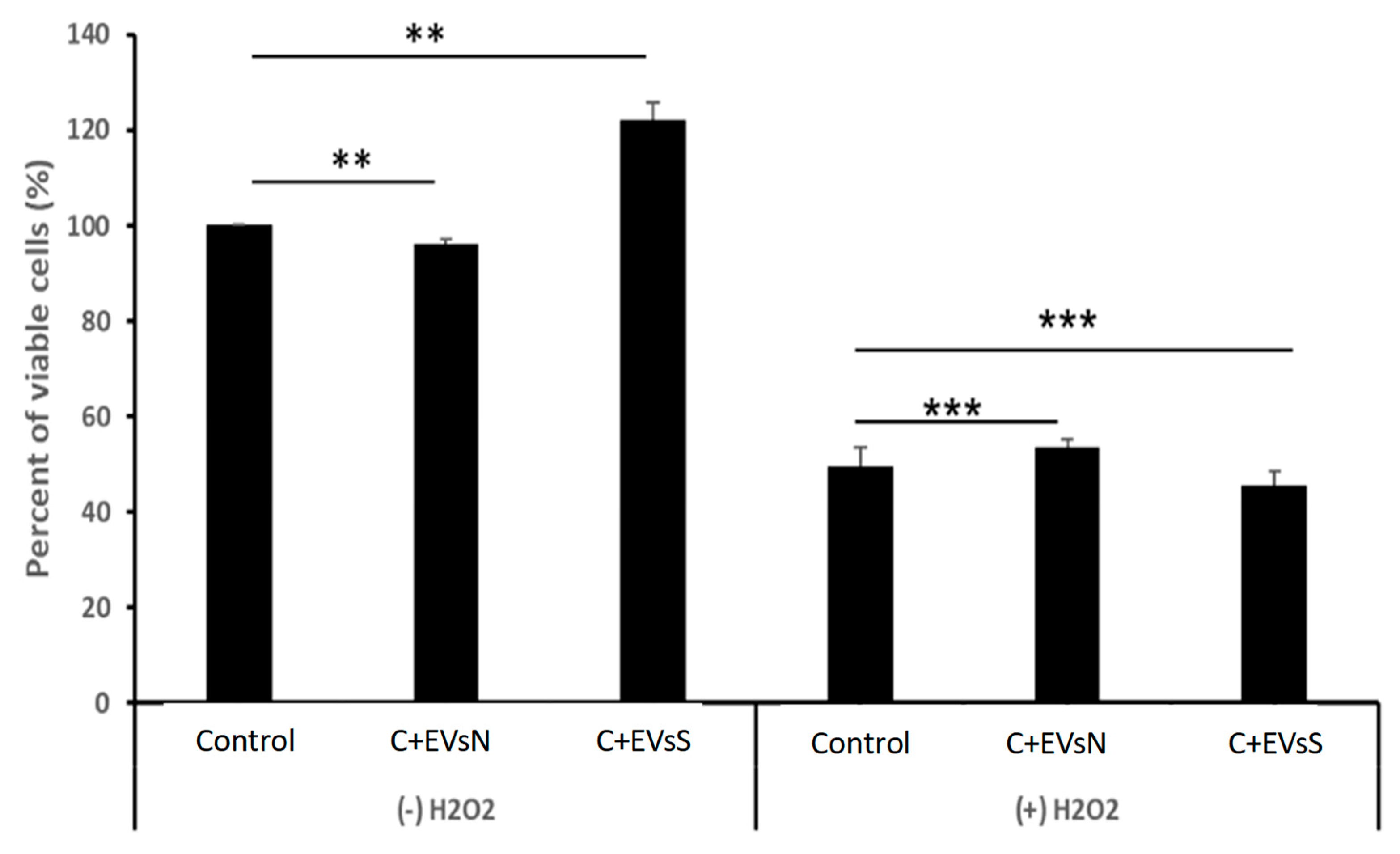

Apart from the differential sensitivity to IM, the number of EVs secreted by these cells presented a major difference between the two cell types, (s-K562 and r-K562,). r-K562 cells secreted twice as many EVs compared to those secreted by s-K562 cells, as reported also in a recently published study [

29].

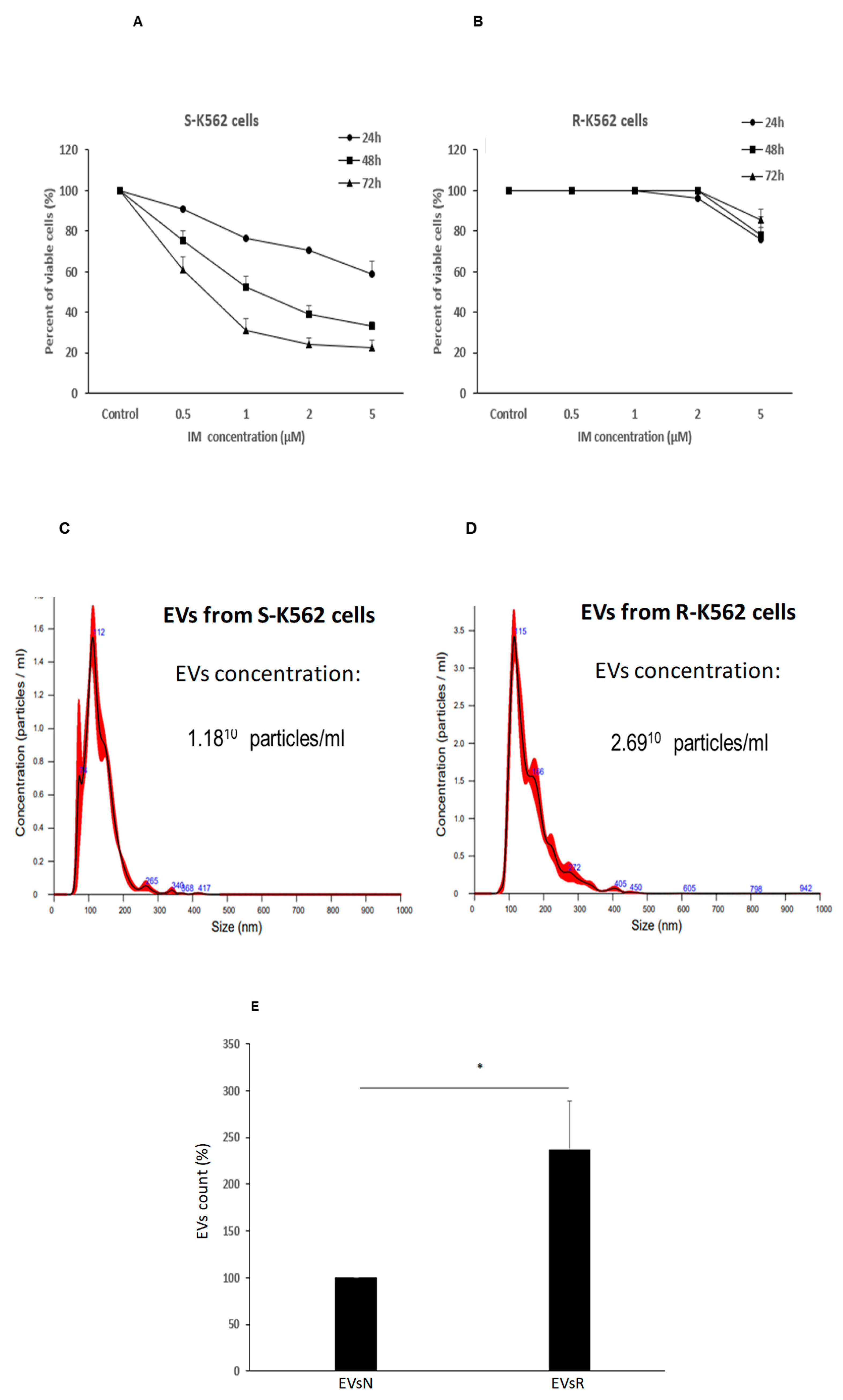

s-K562 cells derived EVs did not confer a drug resistance phenotype to the s-K562 cells, as incubation of these cells with EVs originating either from r-K562 or s-K562 prior to IM did not provide any protection from the drug and even decreased s-K562 cells’ proliferation in response to 48 hours incubation with IM.

In contrast, EVs originating from r-K562 cells (EVs-R) increased the resistance of r-K562 cells to IM compared to those secreted from s-K562 cells (EVs-N), indicating that they may provide IM resistance at least in our setting.

Numerous studies demonstrated that exposure to IM increased the level of DNA damage in susceptible K562 cells compared to that of resistant K562 cells. While undergoing this process, IM susceptible cells accumulated additional DNA damage which, in turn, was one of the factors contributing to rapid cell death [

15,

40].

Previous studies have also reported that CML cells can release EVs, and that they can be transferred between CML cells. Upon engulfment and subsequent release of their cargo, they exert phenotypic changes in the recipient cells [

11,

12,

36,

41].

EVs derived from r-K562 cells had no measurable effects on the survival rate of s-K562 cells in the presence of IM. Interestingly, exosomes from imatinib-resistant CML cells can differentially affect sensitive cells due to variations in their molecular cargo, release mechanisms and interactions with the tumor microenvironment. Key explanations supported by research include 1. Protein and miRNA cargo differences: specific exosomal proteins (e.g., IFITM3, CD146, CD36) and miRNAs (e.g., miR-365) may be transferred to sensitive cells, enhancing survival and reducing apoptosis [

21,

23,

24]. RPL13 and RPL14, both are upregulated in plasma exosomes from imatinib-resistant patients are linked to ribosomal protein synthesis, which may counteract drug effects [

48]. Other recent studies showed that exosomes derived from drug resistant cancer cells transmit chemoresistance by the transfer of extracellular vesicles containing miRNAs in breast cancer cells [

42]. 2. The effect of autophagy-dependent exosome release: Imatinib-resistant cells exhibit increased autophagy activity, promoting exosome release. Drugs like dasatinib reduce exosomal secretion by downregulating autophagy proteins (e.g., beclin-1, Vps34), indirectly influencing recipient cell responses [

49]. 3. Stromal Cell-Derived Exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells MSCs or macrophages can paradoxically promote drug resistance in vivo by delivering miRNAs (e.g., miR-21) or activating pathways like NOTCH3, even if they inhibit proliferation in vitro [

50]. 4. Microenvironmental context: in vivo, exosomes interact with stromal cells, endothelial cells, or immune cells in the bone marrow, creating a protective niche that enhances resistance. This contrasts with simpler in vitro models, where such interactions are absent [

51]. 5. Engineered exosome Therapies studies revealed that modifying exosomal content can reverse resistance, highlighting the importance of cargo specificity [

52].

The discrepancy between these reports and our results may stem from different EVs treatments administered in each study. Although we did increase the number of EVs applied to the cells, we may have missed the optimal EVs amount that might have provided cellular protection from IM. Another possible explanation may be related to differential roles of EVs -mediated survival among patients with CML. In this regard, the mechanism and characteristics of IM resistance may vary among patients and cell lines, thus explaining discrepancies between our study and the above-mentioned ones. IM resistance may manifest with different phenotypes, cellular proliferation rates and other cellular properties, including EVs content and the rate of EVs shedding.

Interestingly, EVs originating from s-K562 cells grown with no oxidative stress (EVs-N) decreased cell viability of r-K562 cells in the presence or absence of IM. Further studies should determine whether this phenomenon will be important in the context of the development of resistance to the drug in patients with CML.

We demonstrated that after incubation with EVs derived from s-K562, decrease of the survival of the r-K562 cells in both conditions with toxic doses of 1 µM IM occurred. With normal condition, on the other hand, EVs derived from r-K562 further increased the proliferation of the r-K562 cells. Although we do not have an explanation for this phenomenon, two recent studies may clarify this point [

43,

44]. Wuxiao et al. reported that exosomal micro-RNA 145, secreted from K562 cells, decreased the proliferation of intact K562 cells exposed to adriamycin by inhibiting ATP-binding cassette sub-family E member 1 (ABCE1). These findings demonstrate that the overexpression of miR 145 promoted leukemic cell apoptosis and enhances the sensitivity of K562/ADM cells to ADM by inhibiting ABCE143, [

44]. The results of our study showed that the protection from oxidative stress provided by K-562 cells- derived EVs exposed to oxidative stress is only partial. However, these EVs can provide intact K-562 cells with some resistance to IM treatment. This result suggests that the resistance to IM may be developed and expand to other cells by EVs that are secreted from already resistant cells, similarly to a horizontal transfer of resistance provided by plasmids in bacteria [

45].

Our study suffers from several limitations. Firstly, the lack of specific techniques such as protease treatment to definitively distinguish between EVs that may have attached the K-562 cell membrane and those EVs that were internalized into the recipient cells. The scientific literature presents conflicting approaches to this challenge. While some researchers advocate for protease treatment (ref. #46), others argue that such enzymatic treatment can disrupt natural uptake mechanisms, cause cellular membrane damage and create experimental artifacts (e.g., ref #47). Importantly, the vast majority of studies do not use any protease inhibitor prior to the analysis of EV’s uptake. In our study however, we observed clear functional effects within the cells, which are unlikely to result from mere surface binding but point to EV’s internalization. These include the differential effects of EVs derived from K562 cells grown under normal (EVs-N) or oxidative stress (EVs-S) conditions on cellular proliferation (

Figure 8,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). However, having said that, we cannot rule out effects of non-vesicular components or surface-bound EVs that may have been present during EVs isolation, triggering signaling in our setting.

Other drawbacks will be addressed in a subsequent following study conduct these days in our laboratory. These include the following: 1. No molecular analyses of our EVs’ content was performed; 2. We haven’t analyzes the effect of EVs isolated from CML patients in our setting; 3. No experiment of blocking the secretion of EVs was conducted as a negative control; 4. We did not study the presence of receptors on K562 membrane that can selectively take up stressed EVs versus normal EVs; 5. The EVs effects on third generations of TKIs such as dasatinib, nilotinib or ponatinib was not tested.; 6. We do not know yet how stable is the resistant phenotype overtime but as mentioned above this point will be checked by us; 7. No experiment with antioxidants or activators of nrf2 were conducted as another type of controls; 8. Dose response relationship between EVs concentration and the magnitude of imatinib resistance was executed; 9. We did not study the possible differences between genomic or mitochondrial DNA in exosomes derived from either imatinib resistant or sensitive ones that may have contributed to horizontal gene transfer into the recipient cells; 10. Analyses of the molecular cargo of the various EVs in our setting including proteome and gene expression was not conducted in the current study.

The clinical significance of our reported findings should await for the results of the above-described expanded future studies and may also include an interference of EVs secretion in patients with CML.

Figure 1.

K-562 derived EVs. (A) K-562 cells were grown in EVs depleted medium for 72 hour and EVs were isolated by ultracentrifugation. Shown is an example of a nanoparticle tracking analysis with highest concentration of particles ranging in size between 100 to 200 nm. (B) Transition electron microscopy image of K-562 derived EVs depicted by the arrowheads. (C) Western immunoblotting analysis of K562 cells and their cognate EVs, showing the presence of two exosomal markers: TSG101, CD63 and the absence of a non-exosomal marker, calnexin. Each experiment was conducted at least three times with biological replicates and technical replicates in each biological one.

Figure 1.

K-562 derived EVs. (A) K-562 cells were grown in EVs depleted medium for 72 hour and EVs were isolated by ultracentrifugation. Shown is an example of a nanoparticle tracking analysis with highest concentration of particles ranging in size between 100 to 200 nm. (B) Transition electron microscopy image of K-562 derived EVs depicted by the arrowheads. (C) Western immunoblotting analysis of K562 cells and their cognate EVs, showing the presence of two exosomal markers: TSG101, CD63 and the absence of a non-exosomal marker, calnexin. Each experiment was conducted at least three times with biological replicates and technical replicates in each biological one.

Figure 2.

Oxidative stress differentially affects cell proliferation and EVs secretion. (A, B). K-562 cells were grown in the presence of various H2O2 concentrations and cells’ viability was assessed by the Trypan Blue exclusion assay. The arrows depict the chosen concentration of H2O2 to which the cells were exposed to 75 μM. (C). Number of EVs released from cells grown in the presence of 75μM H2O2, relative to EVs released from control intact cells. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three experiments. Each experiment was conducted three times with biological replicates and technical replicates in each one. ** P< 0.01, statistical significance as calculated by student t- Test.

Figure 2.

Oxidative stress differentially affects cell proliferation and EVs secretion. (A, B). K-562 cells were grown in the presence of various H2O2 concentrations and cells’ viability was assessed by the Trypan Blue exclusion assay. The arrows depict the chosen concentration of H2O2 to which the cells were exposed to 75 μM. (C). Number of EVs released from cells grown in the presence of 75μM H2O2, relative to EVs released from control intact cells. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three experiments. Each experiment was conducted three times with biological replicates and technical replicates in each one. ** P< 0.01, statistical significance as calculated by student t- Test.

Figure 3.

Proliferative stress differentially affects cell viability and secretion of EVs. K-562 cells were grown in the presence of increasing concentrations of FCS. (A). Cells’ viability was assessed by the Trypan Blue exclusion assay. (B). Number of EVs released from cells grown in these conditions, relative to EVs released from control intact cells. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three experiments. Each experiment was conducted three times with biological replicates and technical replicates in each one. * P<0.05, ** P< 0.01 , student’s T-test.

Figure 3.

Proliferative stress differentially affects cell viability and secretion of EVs. K-562 cells were grown in the presence of increasing concentrations of FCS. (A). Cells’ viability was assessed by the Trypan Blue exclusion assay. (B). Number of EVs released from cells grown in these conditions, relative to EVs released from control intact cells. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three experiments. Each experiment was conducted three times with biological replicates and technical replicates in each one. * P<0.05, ** P< 0.01 , student’s T-test.

Figure 4.

Oxidative stress modulates the amount of RNA content and Nrf2 levels of EVs. K-562 cells were grown in the presence of 75μM H2O2 and total RNA was extracted from cells and their cognate EVs. (A, C). Total RNA was extracted from cells and EVs and measured by the Qubit 2 device. Shown are the normalized values of RNA per number of cells and EVs, respectively. (B, D). The expression levels of the NRF2 gene transcript was measured by Q-RT- PCR. Shown are the normalized values of RNA per number of cells and EVs, respectively. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three independent biologically replicates experiments . * P<0.05, student’s T-test.

Figure 4.

Oxidative stress modulates the amount of RNA content and Nrf2 levels of EVs. K-562 cells were grown in the presence of 75μM H2O2 and total RNA was extracted from cells and their cognate EVs. (A, C). Total RNA was extracted from cells and EVs and measured by the Qubit 2 device. Shown are the normalized values of RNA per number of cells and EVs, respectively. (B, D). The expression levels of the NRF2 gene transcript was measured by Q-RT- PCR. Shown are the normalized values of RNA per number of cells and EVs, respectively. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three independent biologically replicates experiments . * P<0.05, student’s T-test.

Figure 5.

Increase in ROS levels arrest K562 cells in G2 phase of the cell cycle. (A). K-562 cells were grown in the presence of 75 μM H2O2 for several time periods. Intracellular levels of ROS were measured using DC-FHDA by flow cytometry. Each column represents mean ± standard error of three independent experiments. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, student’s T-test. (B) a representative example. Time of exposure is indicated above each graph. Cells in G1, S, G2/M are colored in colored in brown, blue and green, respectively. (C) Summary of cell cycle analysis of K-562 cells exposed to 75 μM H2O2 for 24 hours. Cells were processed after PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three independent biologically derived replicates experiments.

Figure 5.

Increase in ROS levels arrest K562 cells in G2 phase of the cell cycle. (A). K-562 cells were grown in the presence of 75 μM H2O2 for several time periods. Intracellular levels of ROS were measured using DC-FHDA by flow cytometry. Each column represents mean ± standard error of three independent experiments. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, student’s T-test. (B) a representative example. Time of exposure is indicated above each graph. Cells in G1, S, G2/M are colored in colored in brown, blue and green, respectively. (C) Summary of cell cycle analysis of K-562 cells exposed to 75 μM H2O2 for 24 hours. Cells were processed after PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three independent biologically derived replicates experiments.

Figure 6.

ROS increased Apoptosis and shrinkage of K562 cells. Cells were cultured for 24 hours in the presence of 75μM H2O2. Thereafter the cells were stained with annexin/PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A). an example of flow cytometry analysis, (B). Quantification of three independent experiments; (C). Microscope inspection of the cells post H2O2 exposure. The circles indicate normal cells in the control group and apoptotic cells in the H2O2 exposed cells. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments. * P<0.05, student’s T-test.

Figure 6.

ROS increased Apoptosis and shrinkage of K562 cells. Cells were cultured for 24 hours in the presence of 75μM H2O2. Thereafter the cells were stained with annexin/PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A). an example of flow cytometry analysis, (B). Quantification of three independent experiments; (C). Microscope inspection of the cells post H2O2 exposure. The circles indicate normal cells in the control group and apoptotic cells in the H2O2 exposed cells. Each column represents mean ± standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments. * P<0.05, student’s T-test.

Figure 7.

Kinetics (time and dose) of EVs uptake by sensitive K562 (s-K562) cells. Cells were subjected to the stained EVs and the uptake was followed during 96 hours by flow cytometry. (A). An example of flow cytometry results, analyzing fluorescent FM-1-34 stained EVs by FL-2 channel. (B). Graphic quantitation of three independent experiments. * P<0.05, student’s T-test. Cells were exposed to increasing amounts of stained EVs and uptake was measured by flow cytometry. (C). a typical flow cytometry analysis of cells exposed to EVs s collected from the growth media of cells grown in normal conditions (EVs-N) (D). a typical flow cytometry analysis of cells exposed to EVs collected from the growth media of cells grown under oxidative stress conditions (75μM of H2O2), exo S. (E, F). Quantitation of three biologically independent experiments of C, D. Numbers in C-F refer to the numbers of EVs to which the cells were exposed. Shown are mean ± standard error mean.

Figure 7.

Kinetics (time and dose) of EVs uptake by sensitive K562 (s-K562) cells. Cells were subjected to the stained EVs and the uptake was followed during 96 hours by flow cytometry. (A). An example of flow cytometry results, analyzing fluorescent FM-1-34 stained EVs by FL-2 channel. (B). Graphic quantitation of three independent experiments. * P<0.05, student’s T-test. Cells were exposed to increasing amounts of stained EVs and uptake was measured by flow cytometry. (C). a typical flow cytometry analysis of cells exposed to EVs s collected from the growth media of cells grown in normal conditions (EVs-N) (D). a typical flow cytometry analysis of cells exposed to EVs collected from the growth media of cells grown under oxidative stress conditions (75μM of H2O2), exo S. (E, F). Quantitation of three biologically independent experiments of C, D. Numbers in C-F refer to the numbers of EVs to which the cells were exposed. Shown are mean ± standard error mean.

Figure 8.

Differential effects of K562 derived EVs derived from cells grown under normal (EVs-N) or oxidative stress (EVs-S) conditions on the proliferation of K562 cells. Cells were exposed to EVs-N or EVs-S and proliferation was assessed by the Trypan Blue exclusion assay in response to H2O2. Left panel: Proliferation of cells with no added H2O2; Right panel: proliferation of cells grown under 75μM of H2O2. Each bar represent mean and standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments. ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, student’s T-test.

Figure 8.

Differential effects of K562 derived EVs derived from cells grown under normal (EVs-N) or oxidative stress (EVs-S) conditions on the proliferation of K562 cells. Cells were exposed to EVs-N or EVs-S and proliferation was assessed by the Trypan Blue exclusion assay in response to H2O2. Left panel: Proliferation of cells with no added H2O2; Right panel: proliferation of cells grown under 75μM of H2O2. Each bar represent mean and standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments. ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, student’s T-test.

Figure 9.

IM differentially affects the viability and number of secreted EVs of IM sensitive vs. IM resistant K562 cells. Cells were grown in the presence of the indicated IM concentrations for 24h, 48h and 72 h and their viability was assessed by the WST-1 assay. (A). IM sensitive K562 (S-K562) (B). IM resistant K-562 cells (R-K562). (C, D). Nano-Sight Tracking Analysis (NTA) of EVs isolated from IM S-K-562 or IM R-K-562 (C, D respectively) cells. (E). R-K-562 secrete more EVs/cells compared to S-K-562 cells. Similar number of both cell types were grown for 48 hours, EVs were isolated and analyzed by the NTA. Shown is mean and standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments. * P<0.05 , student’s T-test.

Figure 9.

IM differentially affects the viability and number of secreted EVs of IM sensitive vs. IM resistant K562 cells. Cells were grown in the presence of the indicated IM concentrations for 24h, 48h and 72 h and their viability was assessed by the WST-1 assay. (A). IM sensitive K562 (S-K562) (B). IM resistant K-562 cells (R-K562). (C, D). Nano-Sight Tracking Analysis (NTA) of EVs isolated from IM S-K-562 or IM R-K-562 (C, D respectively) cells. (E). R-K-562 secrete more EVs/cells compared to S-K-562 cells. Similar number of both cell types were grown for 48 hours, EVs were isolated and analyzed by the NTA. Shown is mean and standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments. * P<0.05 , student’s T-test.

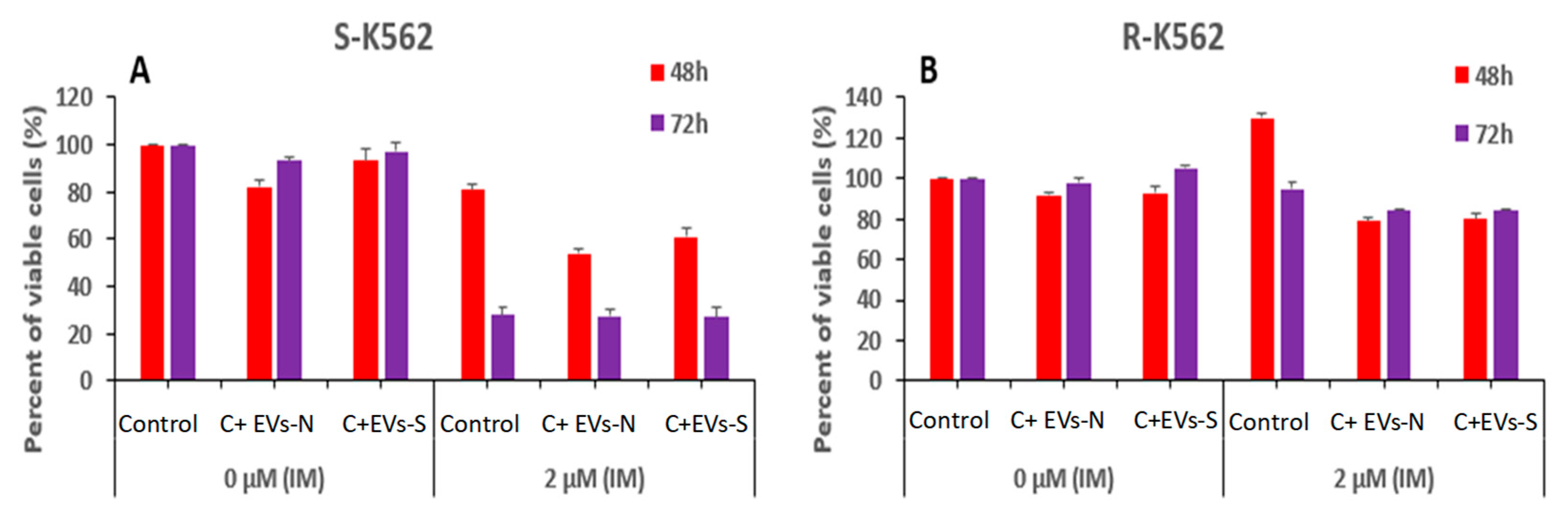

Figure 10.

IM and oxidative stress derived- EVs differentially affect the viability of K562 cells. (A) S-K-562 and (B) R-K562 cells were grown with no EVs (control) or after treatment with EVs derived from either cells grown in normal (EVs-N) conditions or those that derived from cells grown under oxidative stress conditions (EVs-S) for 48h and 72 h. At the end of cells incubation with EVs, 2 µM IM was added for additional 24 hours and cell viability was assessed by the WST-1 assay. Shown is mean and standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments.

Figure 10.

IM and oxidative stress derived- EVs differentially affect the viability of K562 cells. (A) S-K-562 and (B) R-K562 cells were grown with no EVs (control) or after treatment with EVs derived from either cells grown in normal (EVs-N) conditions or those that derived from cells grown under oxidative stress conditions (EVs-S) for 48h and 72 h. At the end of cells incubation with EVs, 2 µM IM was added for additional 24 hours and cell viability was assessed by the WST-1 assay. Shown is mean and standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments.

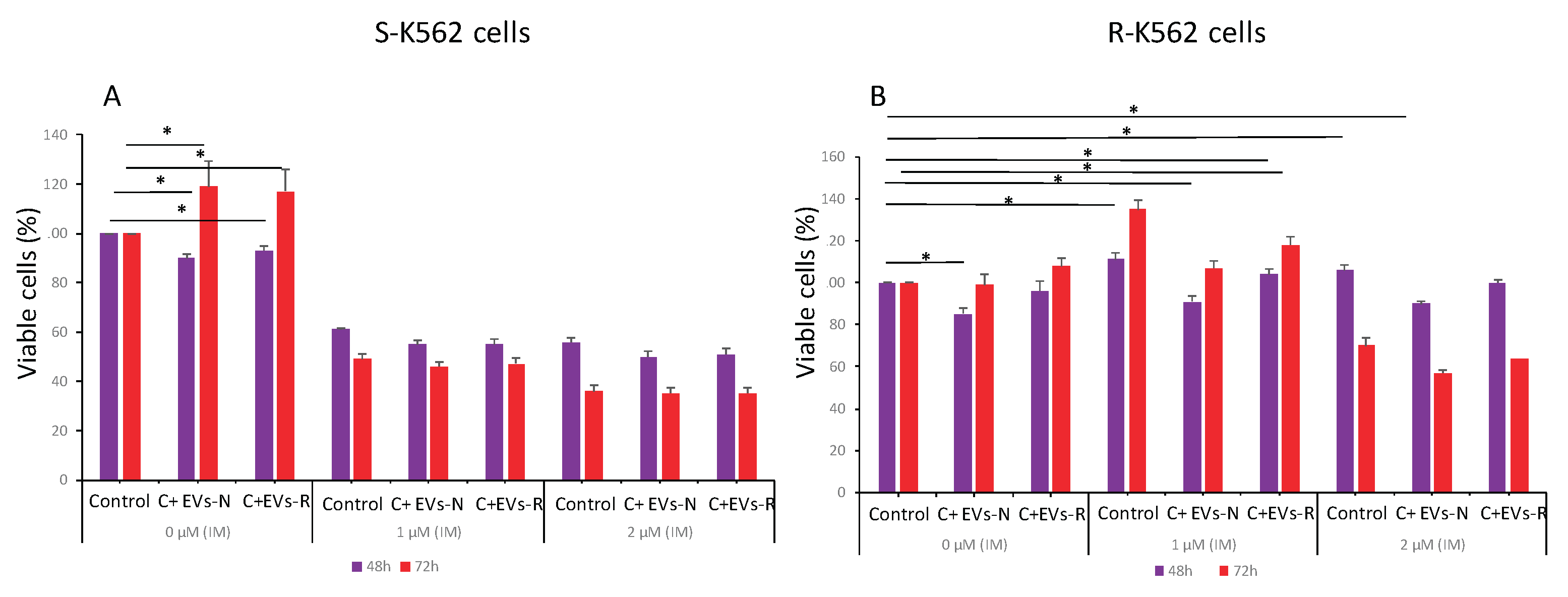

Figure 11.

IM and EVs derived from IM sensitive or resistant cells differentially affect the viability of K562 cells. (A) S-K-562 and (B) R-K562 cells were grown with no EVs (control) or after treatment with EVs derived from either sensitive (S-K-562, EVs-N) cells or from IM-resistant (R-K-562, EVs-R) cells for 48h and 72 h. At the end of cells incubation with EVs, IM was added for additional 24 hours and cell viability was assessed by the WST-1 assay. Shown is the mean and standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments.

Figure 11.

IM and EVs derived from IM sensitive or resistant cells differentially affect the viability of K562 cells. (A) S-K-562 and (B) R-K562 cells were grown with no EVs (control) or after treatment with EVs derived from either sensitive (S-K-562, EVs-N) cells or from IM-resistant (R-K-562, EVs-R) cells for 48h and 72 h. At the end of cells incubation with EVs, IM was added for additional 24 hours and cell viability was assessed by the WST-1 assay. Shown is the mean and standard error mean of three biologically independent experiments.