1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver malignancy, arising predominantly from hepatocytes, the liver’s main functional cells. HCC ranks as the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, following lung and stomach cancers [

1]. It carries a particularly poor prognosis due to its aggressive nature, late-stage detection, and limited therapeutic options in advanced disease. The development of HCC is closely linked to chronic liver diseases, including chronic hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV) infections, cirrhosis, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Chronic inflammation and persistent hepatocellular injury caused by these conditions result in fibrosis and cirrhosis, forming the biological substrate for hepatocarcinogenesis. HCC is especially prevalent in regions with high rates of viral hepatitis, such as East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa [

2].

While HCC incidence is declining in high-endemic areas due to improved antiviral therapies, it is paradoxically rising in other parts of the world, including India, Europe, the United States, and Oceania. This trend is largely driven by the increasing global burden of metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obesity, which predispose individuals to NAFLD, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and eventually HCC [

3]. This epidemiological shift underscores the need for preventive and adjunctive therapies that can mitigate the rising morbidity and mortality associated with HCC in non-viral populations.

Emerging evidence suggests that aspirin, a widely used anti-inflammatory and antiplatelet agent, may play a protective role in liver disease progression and HCC development. This protective effect is believed to involve multiple biological mechanisms, including inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), attenuation of liver fibrosis, suppression of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators, reduction in platelet-derived growth factor signaling, and modulation of immune and platelet activity [

4,

5]. In preclinical models, aspirin has been shown to inhibit hepatic stellate cell activation and reduce fibrogenesis, key processes in the development of cirrhosis and HCC. Several observational studies have further demonstrated a duration-dependent association between low-dose aspirin use and reduced incidence of HCC in patients with chronic liver disease [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Notably, these benefits have been more pronounced in patients with viral hepatitis, although emerging data also support a role in non-viral etiologies.

While many studies have focused on the chemo preventive effects of aspirin in reducing HCC incidence, fewer have evaluated its impact on clinical outcomes among patients already diagnosed with HCC. Of these, a limited number have reported that aspirin use is associated with reduced all-cause mortality in patients with HCC [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, these studies were either limited to cirrhotic patients, did not account for use of other chemo preventive medications (including statins and metformin), or lacked control for non-aspirin NSAID use [

13]. Moreover, many did not adjust for unmeasured confounders or assess healthcare utilization outcomes. Given the potential role of aspirin as an inexpensive, accessible adjunct to current therapeutic strategies, its impact on outcomes beyond incidence prevention warrants further investigation. The use of aspirin as an additional therapy in the treatment of HCC is gaining increasing attention, particularly in the context of its antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory properties.

The present study assessed the effect of aspirin use on in-hospital mortality, morbidity-related complications, healthcare resource utilization, and total hospitalization costs among patients admitted with HCC at the national level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

We conducted a retrospective analysis using data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) for the years 2016 to 2022. The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient healthcare database in the United States. It provides nationally representative data from approximately 20% of hospital discharges, allowing for weighted estimates of inpatient healthcare utilization, cost, demographics, insurance coverage, and clinical outcomes. The NIS is maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The database captures a wide range of diagnoses and procedures using standardized ICD-10-CM codes, facilitating large-scale epidemiologic and outcome-based studies across a diverse patient population. Each year’s dataset contains roughly 7 million unweighted hospitalizations, which can be weighted to generate national estimates exceeding 35 million discharges annually.

2.2. Study Population and Variables

Adult hospitalizations (age ≥18 years) with a primary or secondary diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes. These admissions were then stratified based on documented aspirin use. Patients were included regardless of the indication for aspirin but were excluded if they were concurrently using non-aspirin NSAIDs to minimize confounding from other anti-inflammatory agents.

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included hospital resource utilization (length of stay and total hospital charges), as well as HCC-related complications such as acute liver failure, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, portal vein thrombosis, and obstructive jaundice. These complications were identified using validated ICD-10 codes. Patients with missing demographic or mortality data were excluded from the final analytic sample to ensure robustness in statistical modeling and outcome assessment. Demographic variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, income quartile by ZIP code, insurance status, and hospital region.

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted multiple sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the observed associations. E-values were calculated to estimate the minimum strength of unmeasured confounding that would be required to explain away the observed effects of aspirin on each clinical outcome. For instance, the observed association between aspirin use and in-hospital mortality (OR: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.50–0.68) had an E-value of 2.83, suggesting that substantial unmeasured confounding would be needed to nullify this effect. Similar robustness was observed across other key outcomes, including acute liver failure (E-value: 2.44), hepatic encephalopathy (E-value: 2.80), and others. These results support the conclusion that the observed associations are unlikely to be fully explained by residual confounding.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

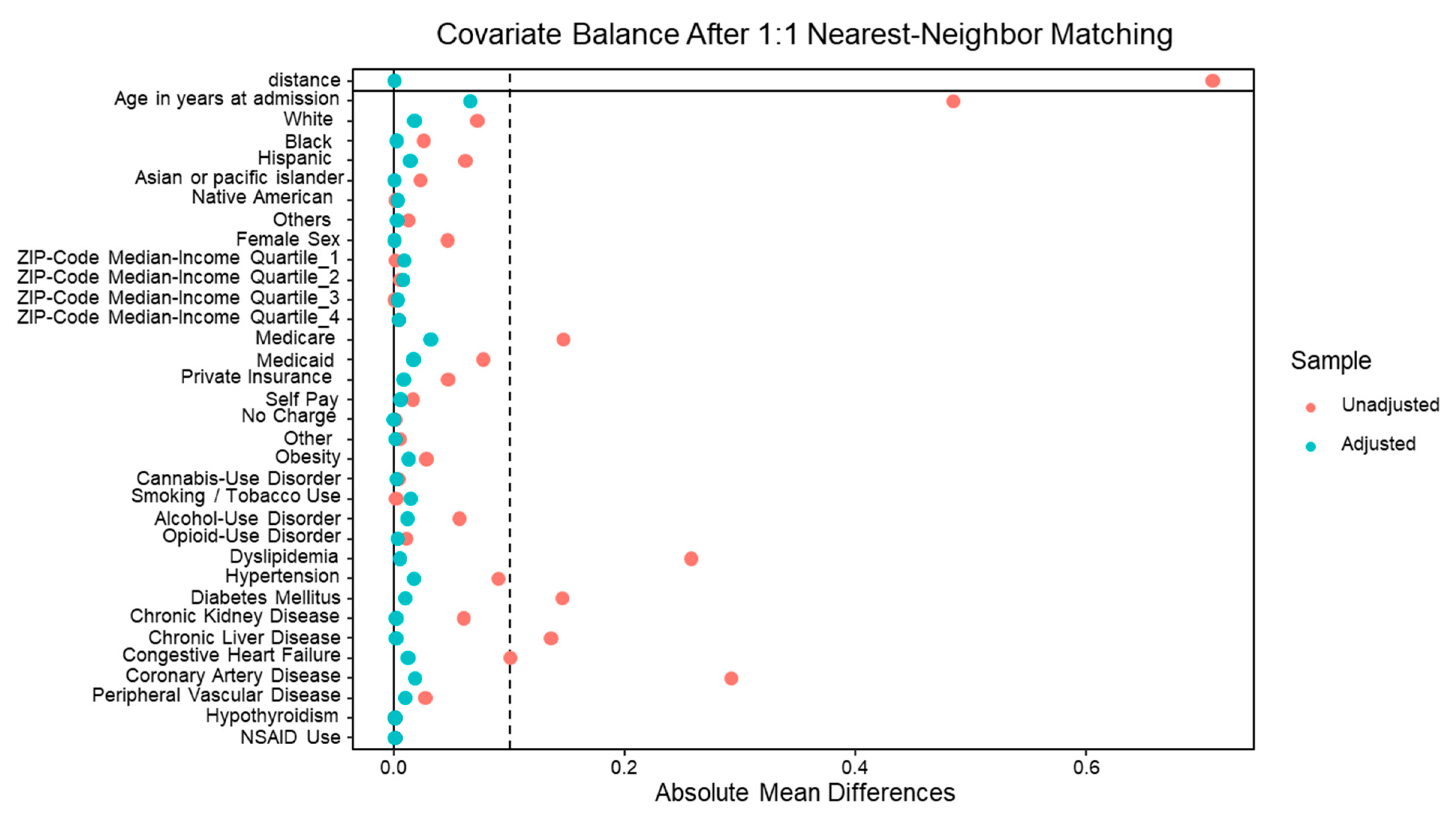

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient and hospital characteristics. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared using the t-test. To reduce confounding bias, we employed 1:1 nearest-neighbor propensity score matching (PSM) with a caliper of 0.2 standard deviations to ensure close matches between aspirin and non-aspirin users. Propensity scores were generated using logistic regression models based on clinically relevant demographic and clinical covariates.

In addition to matching, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was applied to account for residual differences in baseline characteristics. The covariates used for propensity scoring and weighting included obesity, substance use (cannabis, alcohol, opioids, smoking), dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, liver disease severity, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, NSAID use, and key hospital characteristics (bed size, teaching status, urban vs. rural location, and geographic region).

Covariate balance after matching and weighting was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMD), with all covariates demonstrating adequate balance (SMD <0.1). The final matched cohort included 7,910 patients.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for the association between aspirin use and the specified outcomes in the matched cohort, adjusting for all potential confounders. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA/MP version 17.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Hospital Characteristics

A total of 337,730 hospitalizations with a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were included in the final analysis. Of these, 8.79% involved patients with documented aspirin use, while most hospitalizations 91.20% did not report aspirin use. The mean age of patients differed slightly between the two groups, with aspirin users being older on average (69.84 years) compared to non-users (65.30 years); however, this difference was not statistically significant.

Sex distribution showed a statistically significant difference between groups (p < 0.001). A higher proportion of males was observed among aspirin users (78.70%) compared to non-users (74.07%). Racial distribution also differed significantly across the two cohorts (p < 0.001). Aspirin users were more likely to be White (62.07% vs. 54.89%), while Hispanic patients (12.23% vs. 18.42%) and other races (8.28% vs. 11.89%) were more commonly represented among non-users. Black patients made up a similar, though slightly higher, proportion of aspirin users (17.42%) compared to non-users (14.80%).

Socioeconomic status, as assessed by the quartile distribution of median household income based on zip code, did not show any significant differences between the two groups (p = 0.892). The distribution across income quartiles was relatively uniform, with no apparent socioeconomic gradient in aspirin use among hospitalized HCC patients.

Significant disparities were observed in terms of insurance coverage (p < 0.001). Medicare was the predominant primary payer for aspirin users (68.28%) compared to non-users (53.62%), which may reflect the older average age in the aspirin group. Conversely, Medicaid coverage (11.21% vs. 19.07%) and private insurance (15.74% vs. 20.34%) were more prevalent among non-users, possibly indicating a younger and more economically diverse patient population.

Hospital-level characteristics revealed additional significant differences. A slightly higher proportion of aspirin users were admitted to urban teaching hospitals (84.10%) compared to non-users (82.56%), with a p-value of 0.004. This may suggest a trend toward more complex or academic care settings among aspirin users, though the absolute difference was modest. Hospital size did not significantly differ between groups (p = 0.464), with most patients in both cohorts admitted to large hospitals.

Regional distribution of hospitalizations showed a statistically significant variation (p < 0.001). Aspirin users were more frequently hospitalized in the Midwest (24.42% vs. 17.79%), while a higher proportion of non-users were admitted in the West (24.88% vs. 20.18%) and South (37.95% vs. 36.72%). The Northeast had comparable representation in both groups (18.68% among aspirin users vs. 19.39% in non-users).

Table 1.

Socio-demographics and hospital characteristics of HCC hospitalizations with and without aspirin use.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics and hospital characteristics of HCC hospitalizations with and without aspirin use.

| Baseline characteristics |

HCC hospitalizations with aspirin use (%) |

HCC hospitalizations without aspirin use (%) |

P value |

| Age (in years) |

69.84 |

65.30 |

- |

| Sex |

Male |

78.70 |

74.07 |

<0.001 |

| Female |

21.30 |

25.93 |

| Race |

White |

62.07 |

54.89 |

<0.001 |

| Black |

17.42 |

14.80 |

| Hispanic |

12.23 |

18.42 |

| Others |

8.28 |

11.89 |

|

Quartile of median household income for zip code

|

0−25 th

|

32.31 |

32.23 |

0.892 |

|

26th−50th

|

24.87 |

25.24 |

|

51st−75th

|

23.03 |

23.09 |

|

76th−100th

|

19.79 |

19.43 |

|

Primary payer

|

Medicare |

68.28 |

53.62 |

<0.001 |

| Medicaid |

11.21 |

19.07 |

| Private |

15.74 |

20.34 |

| Others |

4.76 |

6.97 |

|

Hospital teaching status and location

|

Rural |

3.90 |

3.78 |

0.004 |

| Urban non-teaching |

12 |

13.66 |

| Urban teaching |

84.10 |

82.56 |

| Hospital bed-size |

Small |

15.70 |

15.08 |

0.464 |

| Medium |

24.55 |

24.38 |

| Large |

59.74 |

60.54 |

| Hospital region |

North-east |

18.68 |

19.39 |

<0.001 |

| Mid-west |

24.42 |

17.79 |

| South |

36.72 |

37.95 |

| West |

20.18 |

24.88 |

3.2. In Hospital Mortality and Morbidity Outcomes

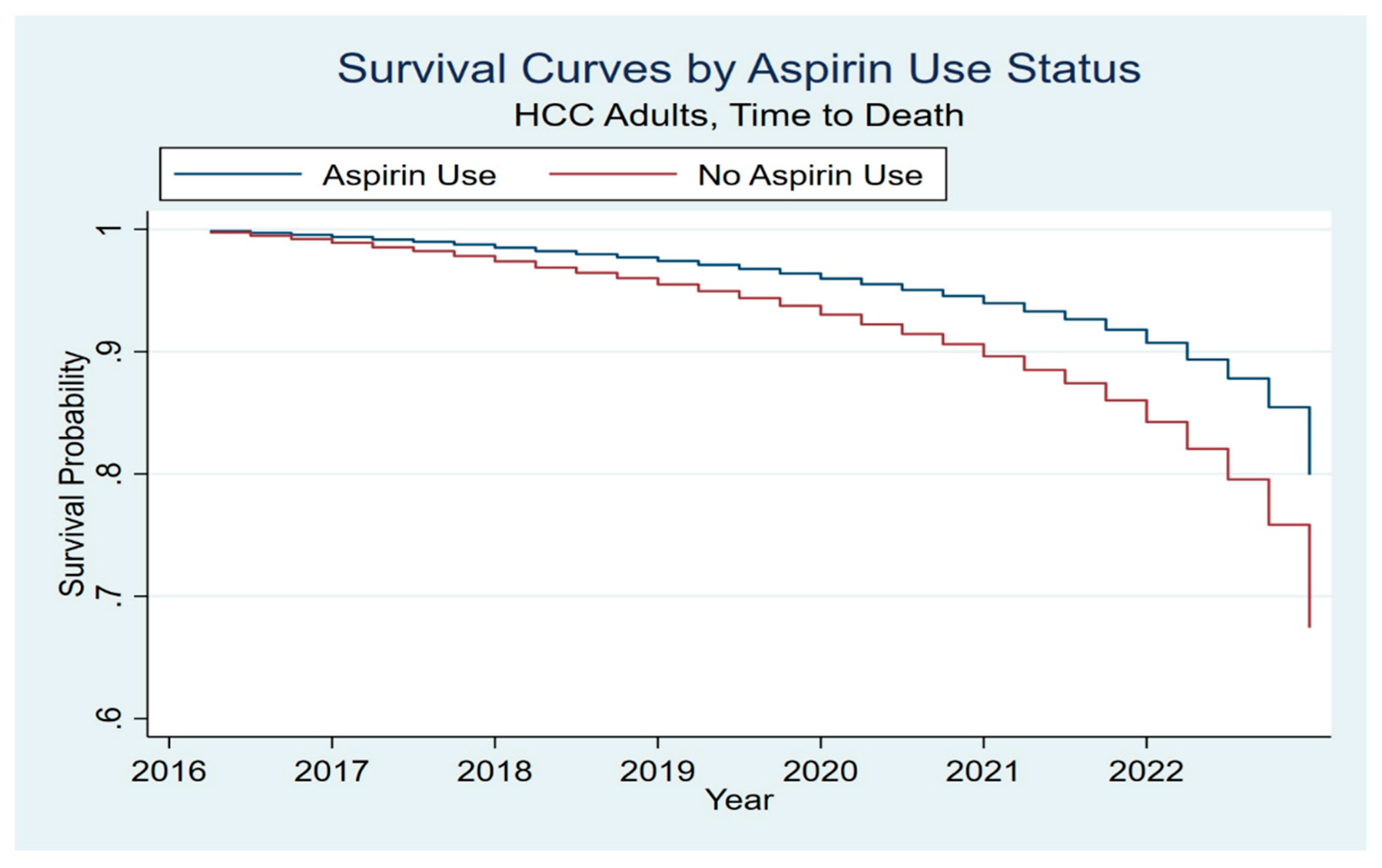

Among hospitalizations with HCC, aspirin use was associated with significantly improved clinical outcomes. Specifically, patients with documented aspirin use had a lower in-hospital mortality rate of 5.2%, compared to 10.09% among those who did not use aspirin. After adjusting for potential confounding variables through multivariate logistic regression and propensity score matching, aspirin use remained independently associated with reduced mortality, with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 0.58 (95% CI: 0.50–0.68, p < 0.001). Kaplan–Meier survival curves further illustrated a significant survival benefit in aspirin users, suggesting a consistent association between aspirin use and favorable in-hospital survival in the HCC population (

Figure 1).

In addition to lower mortality, aspirin use was also associated with reduced healthcare resource utilization. Patients who used aspirin had a shorter mean length of hospital stay (5.42 days vs. 6.39 days; β coefficient = -0.83, 95% CI: -0.98 to -0.68; p < 0.001) and incurred lower total hospital charges ($80,310 vs. $95,098; β coefficient = -$6,330, 95% CI: -$9,797 to -$2,863; p < 0.001).

Patients with aspirin use also had a significantly lower incidence of morbidity complications of HCC, such as acute liver failure (4.0%) compared to non-users (7.39%), with an aOR of 0.65 [0.55–0.78, p < 0.001]. Similarly, the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was lower among aspirin users (1.17%) than in non-users (2.61%), with an aOR of 0.59 [0.43–0.80, p = 0.003]. Aspirin use was also associated with a notable reduction in the incidence of ascites, 28.0% with aspirin use vs 42.87% without aspirin use (aOR = 0.68, p < 0.001), as well as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, which had an aOR of 0.58 [0.47–0.71, p < 0.001].

Additional favorable outcomes were observed in systemic complications. Rates of sepsis were significantly reduced among aspirin users (9.39% vs. 14.09%; aOR = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.62–0.79, p < 0.001). ICU admission rates were also lower in this group (3.55% vs. 6.45%; aOR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.52–0.75, p < 0.001), as were occurrences of acute kidney injury (27.46% vs. 31.75%; aOR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.74–0.88, p < 0.001), indicating a broader systemic benefit associated with aspirin use during hospitalization.

We also observed a decrease in the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding among aspirin users (3.46%) compared to non-users (2.59%). While this result was statistically significant in the multivariate logistic regression, with an aOR 1.09 (CI 1.01-1.19, p = 0.045), the significance was lost in our propensity matched model. [adjusted OR of 1.04 (0.84–1.24, p = 0.569)].

Similarly, no statistically significant difference was observed in the incidence of variceal bleeding (OR = 0.82, p = 0.075), obstructive jaundice, (OR = 1.09, p = 0.468) and portal vein thrombosis (OR of 0.89, p = 0.066) among HCC hospitalizations with and without aspirin use.

Overall, these findings suggest that aspirin use is associated with reduced mortality, lower healthcare utilization, and a decreased risk of multiple complications in patients hospitalized with HCC, and the associations were statistically significant [

Table 2 and

Table 3].

4. Discussion

The effect of aspirin use on reducing the incidence of HCC has been established through prior retrospective analyses, particularly among patients with chronic liver disease [

5]. In this nationwide population analysis, we examined hospitalizations for HCC to assess the outcomes associated with aspirin use. Our findings showed that aspirin use was associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality, reduced healthcare resource utilization, including shorter hospital stays, and lower total hospitalization costs for HCC patients. These findings align with recent meta-analytic evidence suggesting that aspirin use is associated with a reduced risk of both HCC incidence and mortality. For instance, a systematic review and meta-analysis reported a pooled hazard ratio (HR) of 0.72 (95% CI 0.60–0.87) for HCC mortality among aspirin users [

10]. Additionally, a retrospective cohort study from Sweden found that low-dose aspirin use was associated with a 31% reduction in the risk of HCC (adjusted HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.62–0.76) [

5]. Similarly, a recent prospective study by Aktan et al. demonstrated that aspirin use was independently associated with improved overall survival in patients with HCC, reinforcing its potential prognostic benefit beyond the inpatient setting [

16].

In addition to mortality and cost outcomes, we also investigated the effect of aspirin on various morbidity-related complications associated with HCC. Aspirin use was found to be associated with a reduced risk of multiple complications, including acute liver failure, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, portal vein thrombosis, and ascites. To our knowledge, direct studies specifically linking aspirin use to a reduction in these individual complications are limited, particularly in hospitalized populations. However, our findings support the hypothesis that aspirin’s anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic properties may confer broader hepatic protective effects beyond tumor suppression alone.

Our study also revealed that aspirin use among HCC hospitalizations was associated with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, although this difference did not reach statistical significance in the propensity-matched model. This finding is notable because aspirin, as an antiplatelet agent, is often expected to increase the risk of GI bleeding. However, several observational studies have demonstrated no significant increase in bleeding among chronic liver disease patients using aspirin. For instance, a large Swedish nationwide cohort study found no significant difference in the 10-year cumulative incidence of GI bleeding between aspirin users and nonusers (7.8% vs. 6.9%; difference, 0.9 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.6 to 2.4) [

5]. Similarly, Lee et al. reported no statistically significant increase in GI bleeding in aspirin users with chronic hepatitis B (adjusted sub hazard ratio [sHR], 1.11; 95% CI, 0.87–1.42; P = 0.391) [

8].

Conversely, other studies have reported a modest increase in GI bleeding risk with aspirin. A meta-analysis by Li et al. found an elevated but statistically non-significant risk of major bleeding in HCC patients on aspirin (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.99–1.31) [

11]. Nonetheless, the overall balance of evidence suggests that in appropriately selected patients, especially those without active varices or coagulopathy, the benefits of aspirin might outweigh its bleeding risks. Our findings reinforce this perspective and support careful patient stratification for aspirin therapy.

Aspirin’s role in reducing liver-related complications and slowing disease progression is increasingly understood to stem from its diverse mechanisms of action. Primarily, aspirin inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), an enzyme highly expressed in inflammatory cells and tumor tissues in the liver [

10,

17,

18,

19,

20]. COX-2 facilitates angiogenesis and tumor progression and is associated with poorer prognosis in patients with HCC [

21]. By suppressing COX-2 and related prostaglandin pathways, aspirin can hinder tumor vascularization and limit growth. Additionally, aspirin’s inhibition of platelet activation and thromboxane A2 production further contributes to reducing systemic and hepatic inflammation and fibrosis—processes central to hepatocarcinogenesis, particularly in HBV-related liver disease [

10,

22,

23].

Moreover, aspirin may reduce the incidence and severity of cirrhosis-related complications by targeting the hypercoagulable state seen in chronic liver disease. Despite traditionally being associated with coagulopathy, cirrhosis is now recognized to involve complex imbalances that can predispose to thrombosis. Increased thrombin generation, platelet activation (evidenced by elevated 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2, p-selectin expression, and von Willebrand factor interaction), and microvascular thrombosis contribute to portal hypertension and variceal bleeding [

12,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. By inhibiting these pathways, aspirin may mitigate portal vein thrombosis and other vascular complications, ultimately contributing to improved prognosis and reduced decompensation in HCC patients [

30].

Overall, aspirin’s combination of anti-inflammatory, anti-platelet, and anti-fibrotic effects provides significant protective action in the prevention and progression of HCC, particularly in patients with chronic liver diseases like HBV infection and cirrhosis [

10,

17,

30].

The findings of this study suggest that aspirin use may offer significant clinical benefits for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, including reduced in-hospital mortality, fewer hepatic complications, and lower healthcare resource utilization. These results highlight the potential of aspirin as an adjunctive treatment in the management of HCC, particularly in patients with co-existing cardiovascular conditions, where aspirin is already commonly prescribed. Given the relatively low cost and wide availability of aspirin, it may provide a feasible and accessible intervention to improve patient outcomes, especially in resource-limited settings. However, further prospective, randomized controlled trials are necessary to confirm these results and determine the optimal dosing regimen, duration of use, and specific patient populations that may benefit the most. If proven effective, aspirin could become a valuable component of HCC treatment regimens, potentially enhancing survival rates and quality of life in this high-risk group. Moving forward, prospective trials are necessary to establish whether aspirin use independently improves outcomes in HCC hospitalizations. Such trials would provide more conclusive evidence and help guide clinical practices more effectively.

5. Conclusions

Aspirin use in patients hospitalized with hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with reduced in-hospital mortality, fewer liver-related complications, and lower healthcare burden. These findings highlight its potential role as an adjunctive therapy in HCC management. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these associations and guide clinical decision-making regarding aspirin use in this population.

6. Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. The retrospective nature of our study, conducted using the NIS coding database, limits the availability of detailed data such as medication usage and laboratory results, which could influence the outcomes studied. As a result, it was not feasible to assess the severity of the HCC outcomes. Additionally, because the NIS database primarily includes data from hospitalized patients, it may not fully represent the entire HCC patient population, as many cases are managed in outpatient settings unless hospitalization is required due to complications. Consequently, generalizing our findings to the broader population may be challenging. Furthermore, as aspirin is not prescribed specifically for the indication of HCC, its use in these patients is usually secondary to primary or secondary prevention for cardiovascular comorbidities. Although we adjusted for these confounders, this could still affect the study results. Another limitation is that we did not distinguish the dose of aspirin used among these hospitalizations and were unable to completely capture over-the-counter use or adherence of aspirin. Despite these limitations, our study’s robust findings raise significant questions regarding the chemoprotective effect of aspirin on mortality and morbidity outcomes in HCC hospitalizations.

Author Contributions

Manasa Ginjupalli and Jayalekshmi Jayakumar led the development and writing of the manuscript. Anuj Raj Sharma led the data analysis and contributed significantly to the writing. Arnold Forlemu and Praneeth Bandaru conducted thorough reviews and provided critical revisions to enhance the manuscript’s quality. Raissa Nana Sede Mbakop Forlemu and Ali Wakil contributed to data collection and organization. Madhavi Reddy served as the principal investigator, overseeing the conceptualization, project administration, and supervision of the work. All authors participated in manuscript discussions, reviewed the final draft, and approved it for submission.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Brooklyn Hospital (IRB ID – 2340568-1 and date of approval – 06/27/25).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because this study utilized fully de-identified data from the National Inpatient Sample database, which does not contain any identifiable patient information. Therefore, informed consent was not required.

Data Availability Statement

The findings of these studies are backed by data available from the Healthcare Cost Utilization Project (HCUP). This data is accessible to all researchers who follow a standard application process and sign a data use agreement. The authors affirm they did not have any special access to the HCUP data used in this study (covering the years 2007–2020). They paid a fee to obtain the NIS data, according to the fee schedule provided by the HCUP Central Distributor, which handles applications for purchasing HCUP databases and manages data use agreements (DUAs) for all users (

https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/centdist.jsp). Researchers interested in acquiring and using HCUP databases must complete the online HCUP DUA (

https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/dua.jsp) and read and sign the agreement. Additional details on how to apply for purchasing HCUP databases can be found at (

https://www.distributor.hcup-us.ahrq.gov).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the healthcare professionals and researchers who have contributed to the understanding association between GIST and hypoglycemia. Special thanks to the staff at The Brooklyn Hospital Centre for their unwavering support in our research efforts. We also acknowledge the contributions of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for making the National Inpatient Sample database available, which was instrumental in conducting this study. Additionally, we extend our appreciation to our families for their understanding and encouragement throughout this research journey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HCC |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HBV |

Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV |

Hepatitis C virus |

| NAFLD |

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NASH |

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| COX-2 |

Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| ICD-10-CM |

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification |

| IPTW |

Inverse probability of treatment weighting |

| NIS |

National Inpatient Sample |

| aOR |

Adjusted odds ratio |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

| sHR |

Subhazard ratio |

| AHRQ |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| HCUP |

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project |

| SMD |

Standardized mean difference |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Propensity matching of the demographics and comorbidities in HCC hospitalizations with and without aspirin use.

Figure A1.

Propensity matching of the demographics and comorbidities in HCC hospitalizations with and without aspirin use.

References

- Ferenci, P.; Fried, M.; Labrecque, D.; Bruix, J.; Sherman, M.; Omata, M.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): A global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010, 44, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozakyol, A. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC epidemiology). J Gastrointest Cancer. 2017, 48, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrick, J.L.; McGlynn, K.A. The changing epidemiology of primary liver cancer. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2019, 6, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.L.; Sidhu-Brar, S.; Woodman, R.; et al. Regular aspirin use is associated with a reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in chronic liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2023, 54, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, T.G.; Duberg, A.S.; Aleman, S.; Chung, R.T.; Chan, A.T.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Association of aspirin with hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 1018–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memel, Z.N.; et al. Aspirin use is associated with a reduced incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol Commun. 2021, 5, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Shi, J.; Dang, S. Aspirin use and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022, 56, e293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Hsu, Y.; Tseng, H.; et al. Association of daily aspirin therapy with risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B. JAMA Intern Med. 2019, 179, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Association of aspirin with incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 764854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Qu, G.; Sun, C.; et al. Does aspirin reduce the incidence, recurrence, and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma? A GRADE-assessed systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, L. Influence of aspirin use on clinical outcomes of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021, 45, 101545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Hsu, C.Y.; Yen, T.H.; et al. Daily aspirin reduced the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and overall mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Cancers 2023, 15, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, A.; Sohal, A.; Bains, K.; Chaudhry, H.; Singh, I.; Kalra, E.; Arora, K.; Dukovic, D.; Boiles, A.R. Impact of aspirin use on outcomes in patients with hepatocellular cancer: A nationwide analysis. World J Oncol. 2023, 14, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.H.; Chau, G.Y.; Lee, I.C.; Yeh, Y.C.; Chao, Y.; Huo, T.I.; Su, C.W.; Lin, H.C.; Hou, M.C.; Lee, M.H.; Huang, Y.H. Aspirin is associated with low recurrent risk in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma patients after curative resection. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020, 119, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.H.; Hsu, R.J.; Wang, T.H.; Wu, C.T.; Huang, S.Y.; Hsu, C.Y.; Su, Y.C.; Hsu, W.L.; Liu, D.W. Aspirin decreases hepatocellular carcinoma risk in hepatitis C virus carriers: A nationwide cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktan, H.; Ozdemir, A.A.; Karaoğullarindan, Ü. Effect of aspirin use on survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, 35, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Chung, G.E.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Antiplatelet therapy and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients on antiviral treatment. Hepatology. 2017, 66, 1556–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cai, W.; Chu, E.S.H.; et al. Hepatic cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression induced spontaneous hepatocellular carcinoma formation in mice. Oncogene. 2017, 36, 4415–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.A.; Schubert, D.; Sahi, D.; et al. Proapoptotic and antiproliferative potential of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in human liver tumor cells. Hepatology. 2002, 36, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foderà, D.; D’Alessandro, N.; Cusimano, A.; et al. Induction of apoptosis and inhibition of cell growth in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by COX-2 inhibitors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004, 1028, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Prognostic significance of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci. 2016, 12, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannacone, M.; Sitia, G.; Isogawa, M.; et al. Platelets mediate cytotoxic T lymphocyte-induced liver damage. Nat Med. 2005, 11, 1167–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goubran, H.A.; Burnouf, T.; Stakiw, J.; et al. Platelet microparticle: A sensitive physiological “fine tuning” balancing factor in health and disease. Transfus Apher Sci. 2015, 52, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, A.; Mannucci, P.M. The coagulopathy of chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2011, 365, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, A.; Salerno, F.; Chantarangkul, V.; et al. Evidence of normal thrombin generation in cirrhosis despite abnormal conventional coagulation tests. Hepatology. 2005, 41, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatt, A.; Riddell, A.; Calvaruso, V.; et al. Enhanced thrombin generation in patients with cirrhosis-induced coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2010, 8, 1994–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferro, D.; Basili, S.; Iuliano, L.; et al. Increased thromboxane metabolites excretion in liver cirrhosis. Thromb Haemost. 1998, 79, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasiuk, A.; Prokopowicz, D.; Zak, J.; et al. Activation of blood platelets in chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis: P-selectin expression on blood platelets and secretory activity of beta-thromboglobulin and platelet factor-4. Hepatogastroenterology 2001, 48, 818–822. [Google Scholar]

- Lisman, T.; Bongers, T.N.; Adelmeijer, J.; et al. Elevated levels of von Willebrand factor in cirrhosis support platelet adhesion despite reduced functional capacity. Hepatology. 2006, 44, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Shibata, M.; Oe, S.; et al. Antiplatelet therapy improves the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).