Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Carbonate Adsorption Data

2.2. Goethite Surface Protonation Behavior and CD-MUSIC Modeling in NaCl

2.3. Carbonate Adsorption Description Using the CD-MUSIC Model

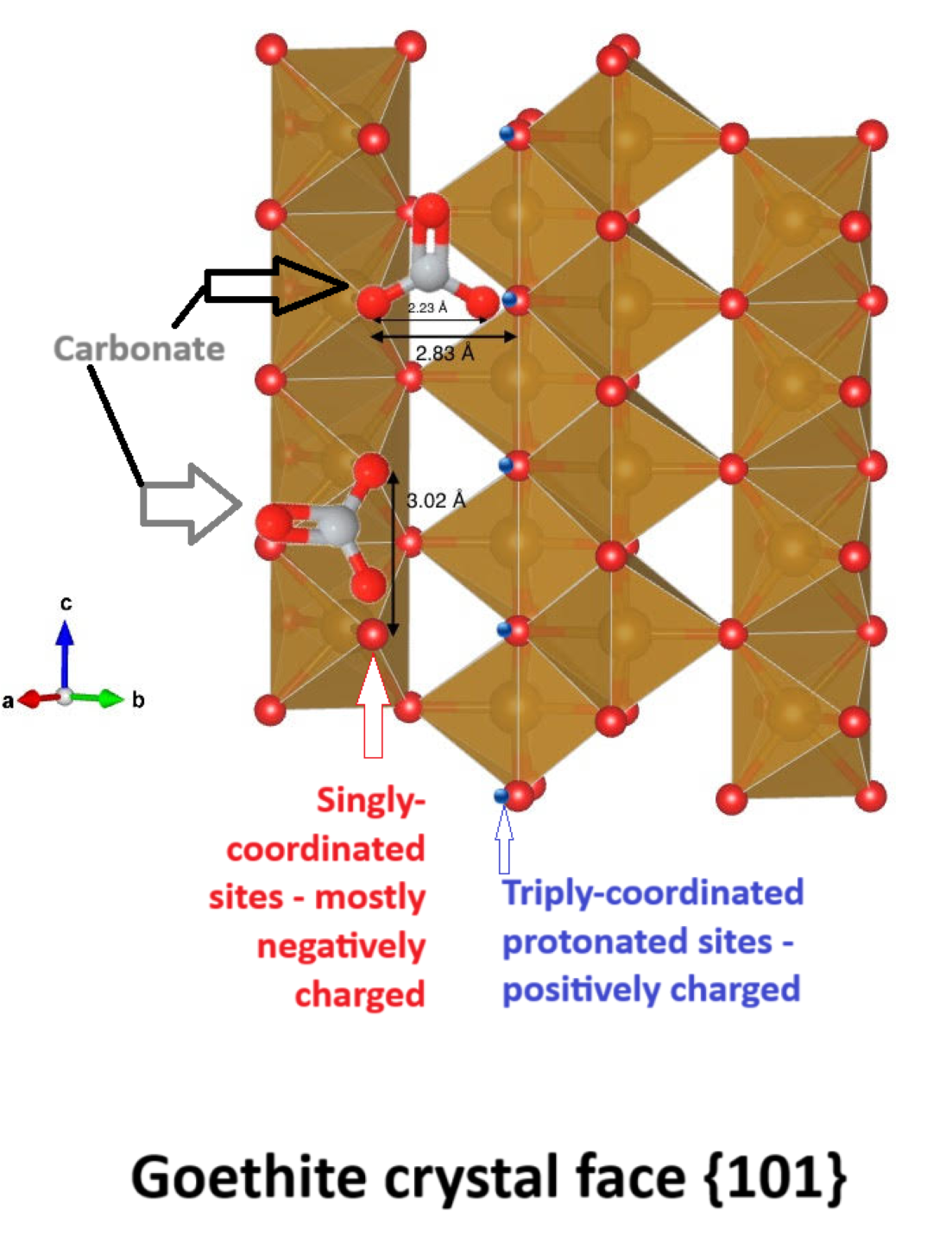

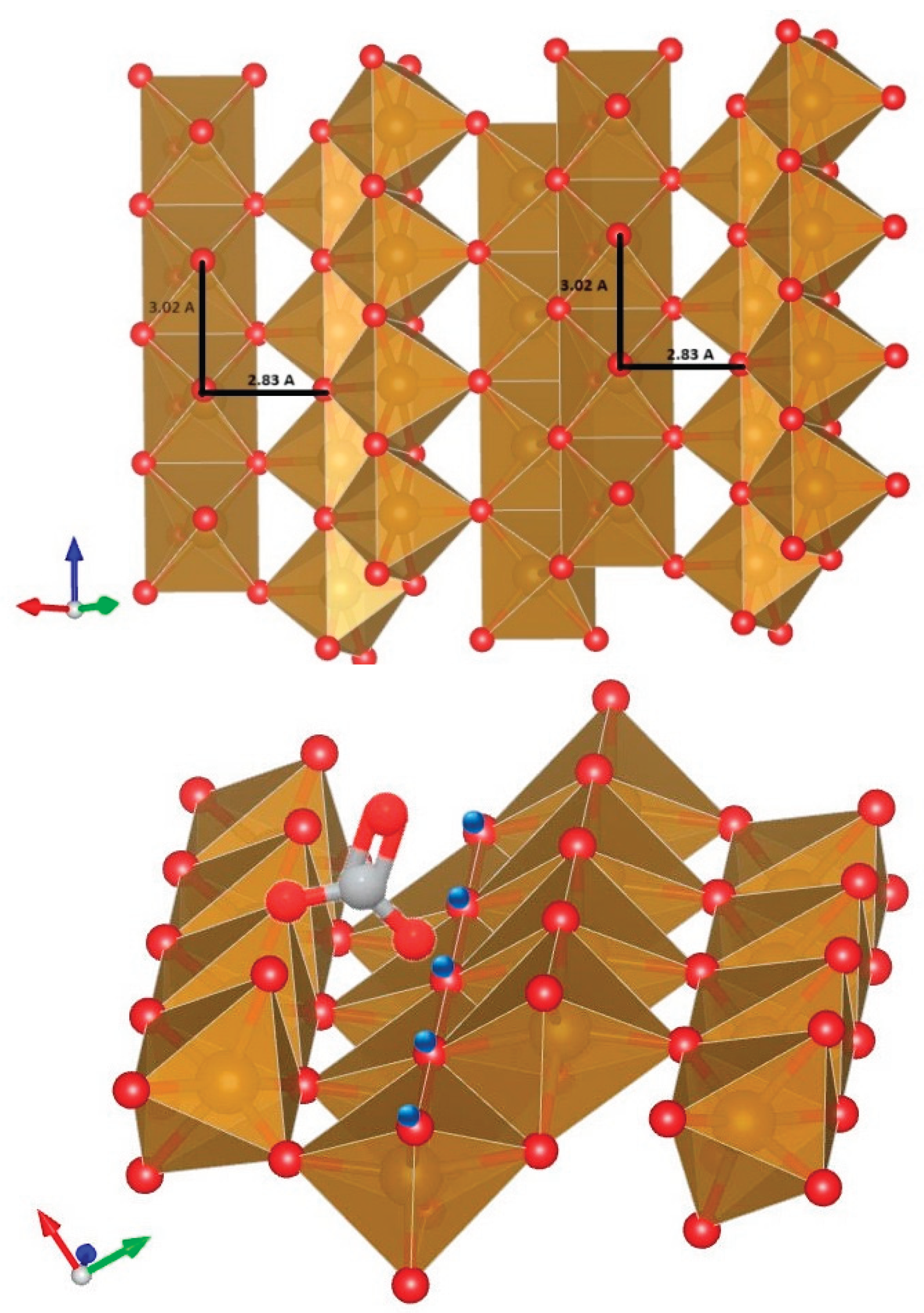

2.3.1. Configuration of the Adsorbed Carbonate Complex

2.3.2. Infrared Evidence

2.3.3. CD-MUSIC Model Fitting Procedure

3. Results

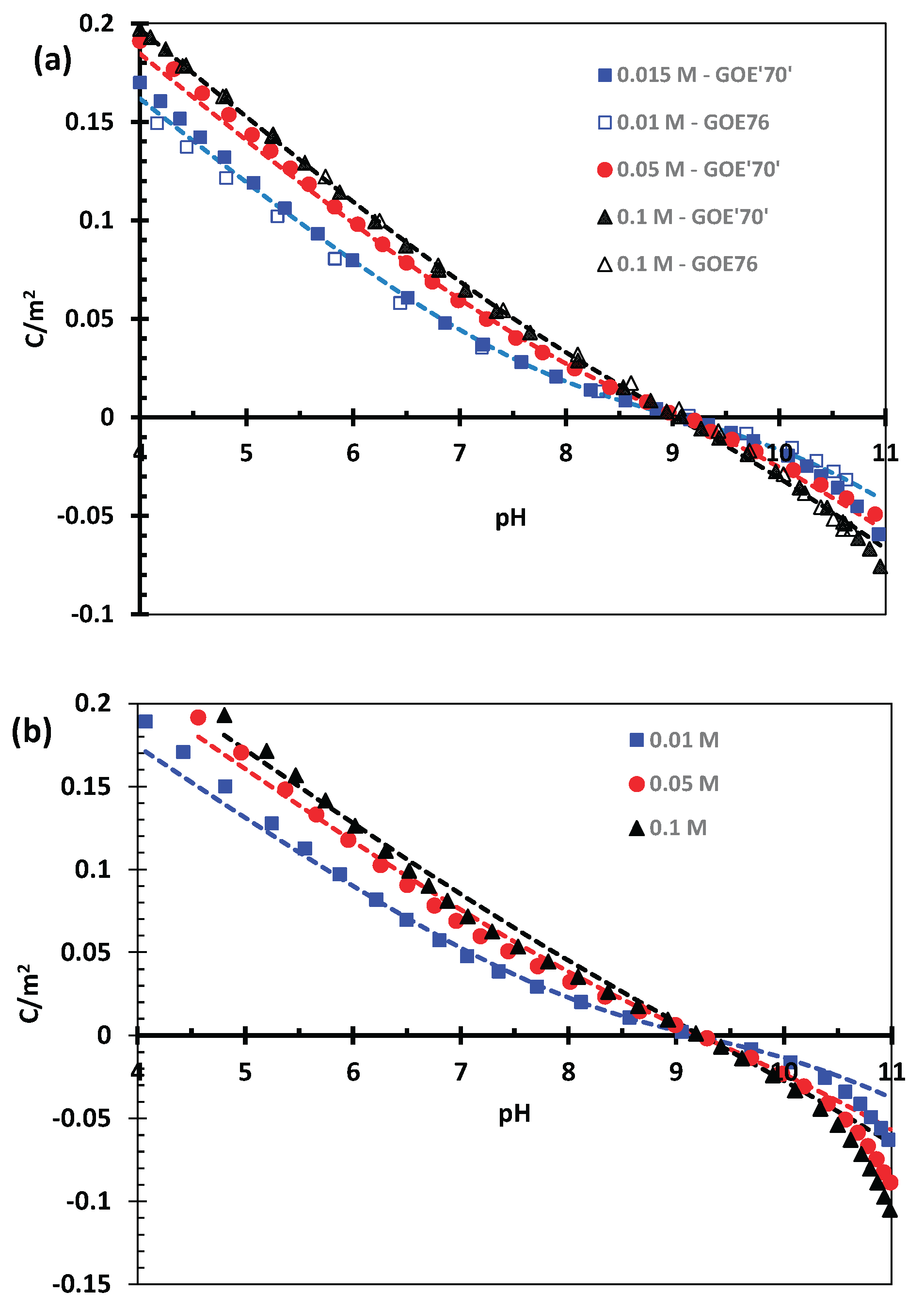

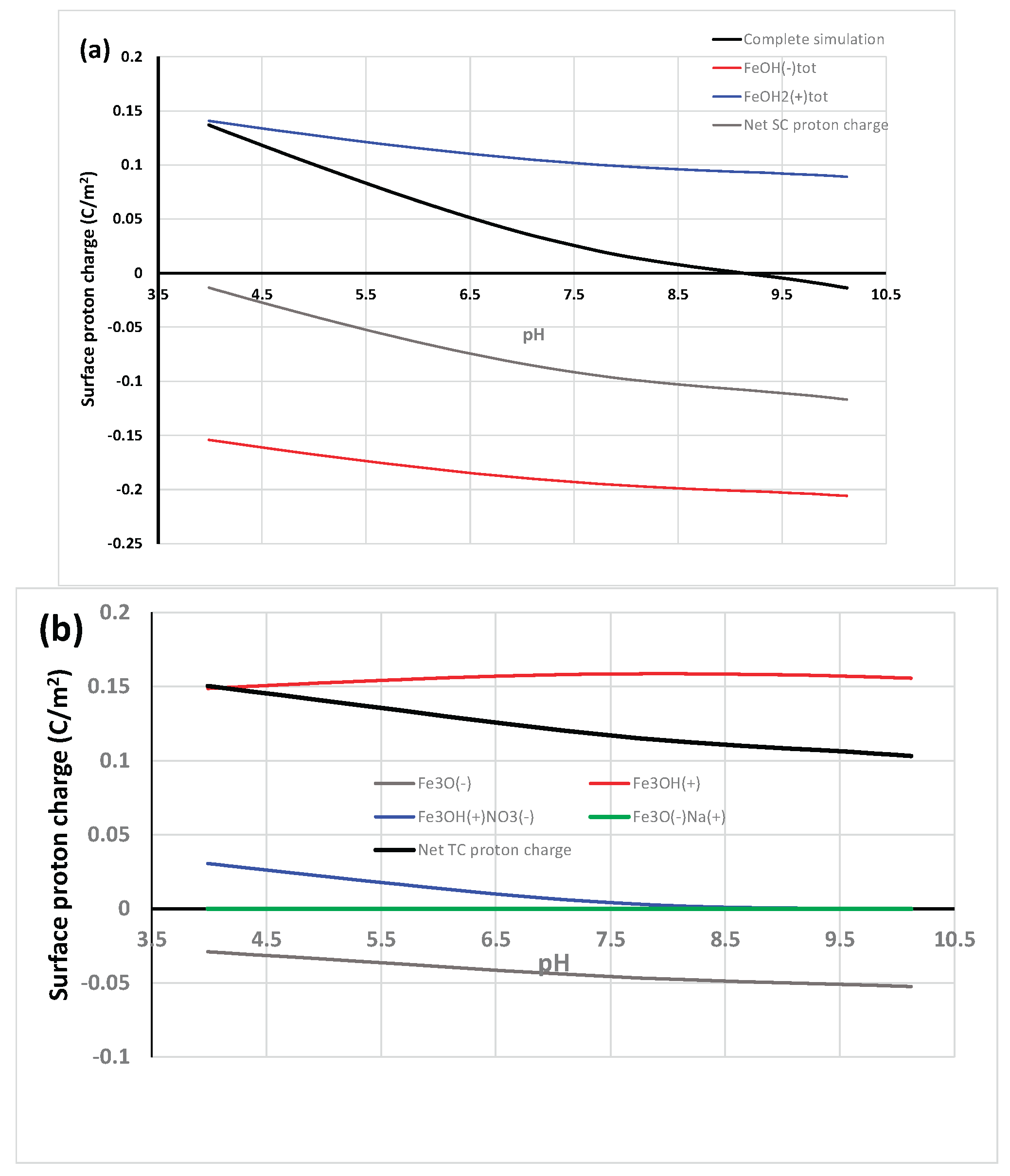

3.1. Goethite Surface Proton Charging in NaCl

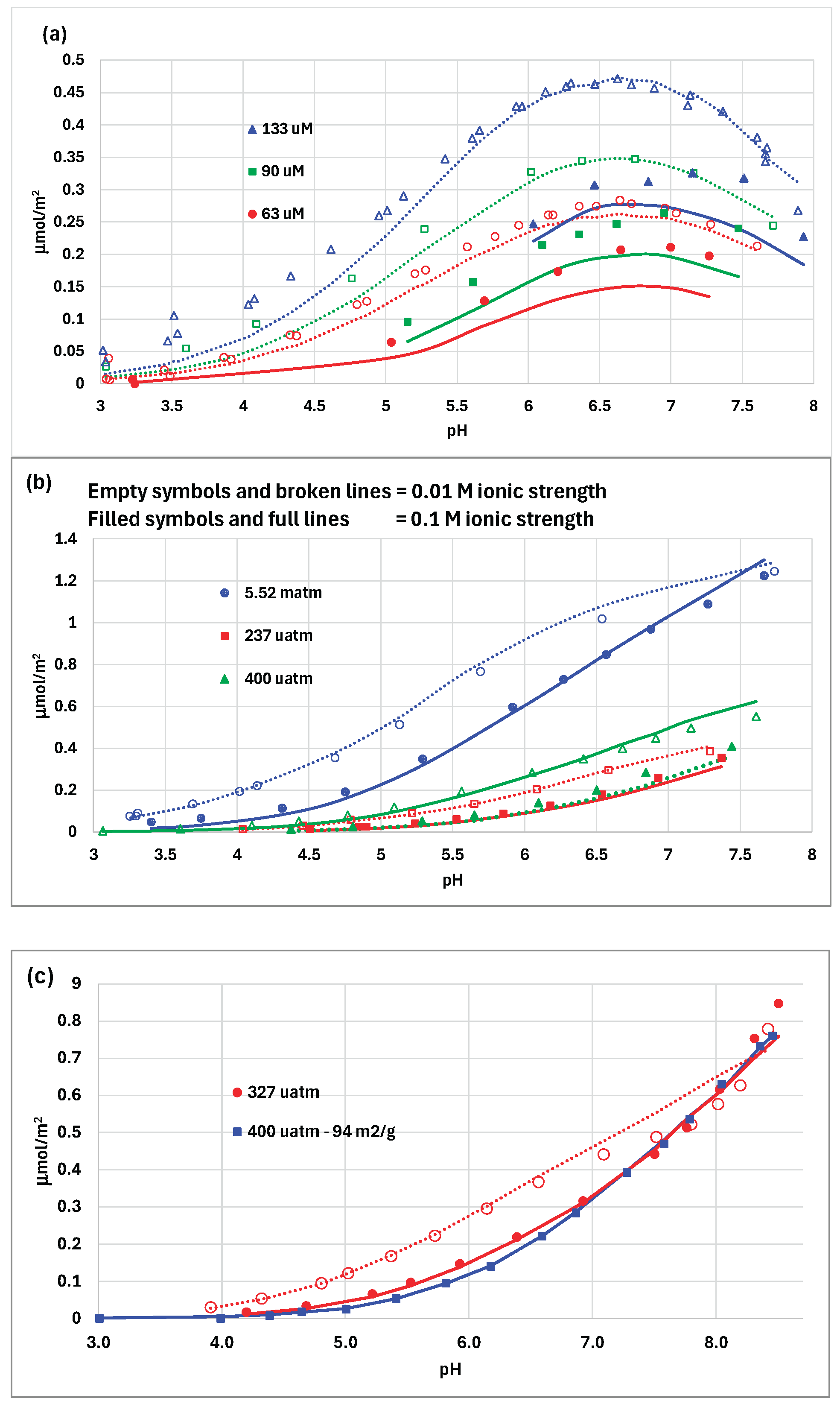

3.2. Carbonate Adsorption Modeling

4. Discussion

4.1. Goethite Specific Surface Area and Surface Proton Charging in NaCl

4.2. Carbonate Adsorption

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD-MUSIC. | Charge-Distribution MultiSite Ion Complexation |

| SC | singly-coordinated |

| TC | triply-coordinated |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

| PZNPC | point of zero net proton charge |

| MO/DFT | Molecular Orbitals/Density Functional Theory |

References

- Cornell, R.M.; Schwertmann, U. The Iron Oxides. Structure, Properties, Reactions, Occurrences and Uses, 2nd ed.; WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003; pp. 253-296, 441-447. [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos, M.; Leckie, J.O. Carbonate adsorption on goethite under closed and open CO2 conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2000, 64, 3787–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, M.; Leckie, J.O. Surface complexation modeling and FTIR study of carbonate adsorption to goethite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001, 235, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiemstra, T.; Rahnemaie, R.; van Riemsdijk, W.H. Surface complexation of carbonate on goethite: IR spectroscopy, structure and charge distribution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 278, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, T.; van Riemsdijk, W.H. A surface structural approach to ion adsorption: the charge distribution (CD) model. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1996, 179, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R.J.; Villalobos, M.; Loredo-Jasso, A.U.; Cruz-Valladares, A.X.; Mendoza- Flores, A.; Salazar-Rivera, H.; Cruz-Romero, D. Towards building a unified adsorption model for goethite based on variable crystal face contributions: I. Acidity behavior and As(V) adsorption. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2023, 354, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, M.; Cruz-Valladares, A.X.; Loredo-Jasso, A.U.; Villa-Nava, P.; López-Castilla, F.; Huerta-Hernández, L.F. Towards building a unified adsorption model for goethite based on variable crystal face contributions: II. Pb(II), Zn(II) and phosphate adsorption. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2025, 396, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livi, K.J.T.; Villalobos, M.; Leary, R.; Varela, M.; Barnard, J.; Villacís-García, M.; Zanella, R.; Goodridge, A.; Midgley, P. Crystal face distributions and surface site densities of two synthetic goethites: Implications for adsorption capacities as a function of particle size. Langmuir 2017, 33, 8924–8932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livi, K.J.T.; Villalobos, M.; Ramasse, Q.; Brydson, R.; Salazar-Rivera, H.S. Surface site density of synthetic goethites and its relationship to atomic surface roughness and crystal size. Langmuir 2023, 39, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, M.; Trotz, M.A.; Leckie, J.O. Surface complexation modeling of carbonate effects on the adsorption of Cr(VI), Pb(II) and U(VI) on goethite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 3849–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslen, E.N.; Streltsov, V.A.; Streltsova, N.R. X-ray study of the electron density in calcite, CaCO3. Acta Crystallog. Sect. B-Struct. Sci. 1993, 49, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusek, M.; Chapuis, G.; Meyer, M.; Petricek, V. Sodium carbonate revisited. Acta Crystallog. Sect. B-Struct. Sci. 2003, 59, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazemann, J.; Berar, J.; Manceau, A. Rietveld studies of the aluminium-iron substitution in synthetic goethite. Mater. Sci. Forum 1991, 79, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicki, J. D.; Kwon, K.D.; Paul, K.W.; Sparks, D.L. Surface complex structures modelled with quantum chemical calculations: carbonate, phosphate, sulphate, arsenate and arsenite. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargar, J.R. Kubicki, J.D. Reitmeyer, R.; Davis, J.A. ATR-FTIR spectroscopic characterization of coexisting carbonate surface complexes on haematite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 2005; 69, 1527–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Jolivet, J.P.; Thomas, Y.; Taravel, B.; Lorenzelli, V.; Busca, G. Infrared spectra of Ce and Th pentacarbonate complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 1982, 79, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatehouse, B.M.; Livingstone, S. E.; Nyholm, R. S. The infrared spectra of some simple and complex carbonates. J. Chem. Soc. London, 3137. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, J.; Martell, A.E.; Nakamoto, K. Infrared spectra of metal chelate compounds. VIII. Infrared spectra of Co (III) carbonato complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 1962; 36, 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Mosset, A.; Bonnet, J.J.; Galy, J. Structure cristalline de la chalconatronite synthetique: Na2Cu(CO3)2*3H2O. Z. Kristallogr., 1978, 148, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeltner, W.A.; Anderson, M.A. Surface charge development at the goethite/aqueous solution interface: effects of CO2 adsorption. Langmuir 1988, 4, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargar, J.R.; Reitmeyer, R.; Davis, J.A. Spectroscopic confirmation of uranium(VI)-carbonato adsorption complexes on hematite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 2481–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostergren, J.D.; Trainor, T.P.; Bargar, J.R.; Brown Jr., G. E.; Parks, G.A. Inorganic ligand effects on Pb(II) sorption to goethite (α-FeOOH) I. Carbonate. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 225, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E.; Baltanás. M.A.; Bonivardi, A.L. Infrared spectroscopic study of the carbon dioxide adsorption on the surface of Ga2O3 polymorphs. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 5498–5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachowicz, M.; Hiemstra, T.; van Riemsdijk, W.H. Surface speciation of As(III) and As(V) in relation to charge distribution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 302, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahnemaie, R.; Hiemstra, T.; van Riemsdijk, W.H. Geometry, charge distribution, and surface speciation of phosphate on goethite. Langmuir 2007, 23, 3680–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahnemaie, R.; Hiemstra, T.; van Riemsdijk, W.H. Carbonate adsorption on goethite in competition with phosphate. J.Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 315, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Goethite(SSA-m2/g) | Total crystal faces |

Separate reactive SC site density sites /nm2 |

Separate reactive TC site density sites /nm2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOE42 | {101} 64% {210} 36% |

1.94 2.70 |

1.94 0 |

| GOE53 | {101} 68% {210} 32% |

2.06 2.40 |

2.06 0 |

| GOE76 | {101} 73% {210} 27% |

2.21 2.03 |

2.21 0 |

| GOE82-GOE101 | {101} 84 {210} 16% |

2.55 1.20 |

2.55 0 |

| Reaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 9.05 (-0.60)b | |||

| 9.55 (-0.1)b | |||

| -0.96 | |||

| 8.22 (-0.60)b | |||

| 8.72 (-0.1)b | |||

| -0.40 | |||

| 9.65 | |||

| 8.82 | |||

| Capacitance 2 (C2) | |||

| Capacitance 1 (C1) | |||

| GOE42 | GOE55 | GOE76 | GOE82+ |

| 1.05 | 1.04 | 0.93 | 0.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).