1. Introduction

In recent years, with the widespread application of robots in industrial, medical, and other fields, traditional position control methods have struggled to meet the demands of dynamic tasks requiring compliance and environmental adaptability. Consequently, safely transferring humans’ natural and autonomous skills to robots has become a critical research focus. Imitation learning, also referred to as learning from demonstration, has advanced rapidly in recent years and emerged as an effective approach for robots to acquire and master human operational skills. Compared to conventional methods, imitation learning offers intuitive and straightforward teaching, eliminating the need for manual programming tailored to specific scenarios or tasks. Moreover, it enables rapid generalization to other task scenarios to accommodate diverse requirements. However, learning human skills—particularly those involving multimodal information (e.g., position, stiffness)—remains a challenge in human-to-robot skill transfer.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the human body can adaptively modulate limb impedance properties in response to varying environments and demands, owing to the central nervous system [

1,

2]. Therefore, developing an imitation learning framework to transfer this human impedance modulation mechanism to robots would enhance their adaptability across diverse task scenarios. Many researchers have analyzed the impedance characteristics of the human upper limb, employing mechanical perturbation methods to estimate impedance parameters (mass, damping, and stiffness) at the limb’s endpoint in both 2D and 3D spaces [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, mechanical perturbation methods face significant limitations in real-time estimation of upper-limb impedance, particularly for dynamic tasks. Consequently, some researchers have turned to surface electromyography (sEMG) signals for impedance estimation, achieving promising results [

9,

10,

11]. The sEMG signals of the human upper limb contain muscle activation information, enabling the characterization and estimation of impedance variations during motion or task execution. Thus, sEMG signals offer a more direct means of transferring human limb stiffness to robots, replicating human adaptability and flexibility.

The process of human-to-robot skill transfer via imitation learning primarily consists of three steps: demonstration, representation, and learning. Current demonstration methods predominantly employ kinesthetic teaching [

12], though alternative control interfaces such as joysticks [

13], infrared sensors [

14], wearable devices [

15], and vision systems [

16] have also been utilized. Kinesthetic teaching is intuitive and yields highly accurate data, making it a common choice for imitation learning systems. However, it requires robots to possess compliant motion capabilities and involves direct physical contact between the demonstrator and the robot. For representation and learning, widely adopted approaches include Dynamic Movement Primitives (DMPs) [

17], Probabilistic Movement Primitives (ProMPs) [

18,

19], Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) [

20], Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) [

21,

22,

23], and Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL) [

24,

25]. Among these, DMPs enable skill acquisition from a single demonstration and allow generalization to new scenarios by modifying start/end points and time constants. Consequently, DMPs enhance robotic flexibility and adaptability, facilitating rapid adjustments to dynamic task demands and improving autonomy and robustness in complex environments. To date, DMPs have been applied to diverse skill-learning tasks, including avoiding obstacles [

26], lifting [

27], agricultural activities [

28], and drawing [

29]. Nevertheless, existing research has focused primarily on motion trajectories, leaving the challenge of enabling robots to learn human-like skills involving impedance modulation largely unresolved.

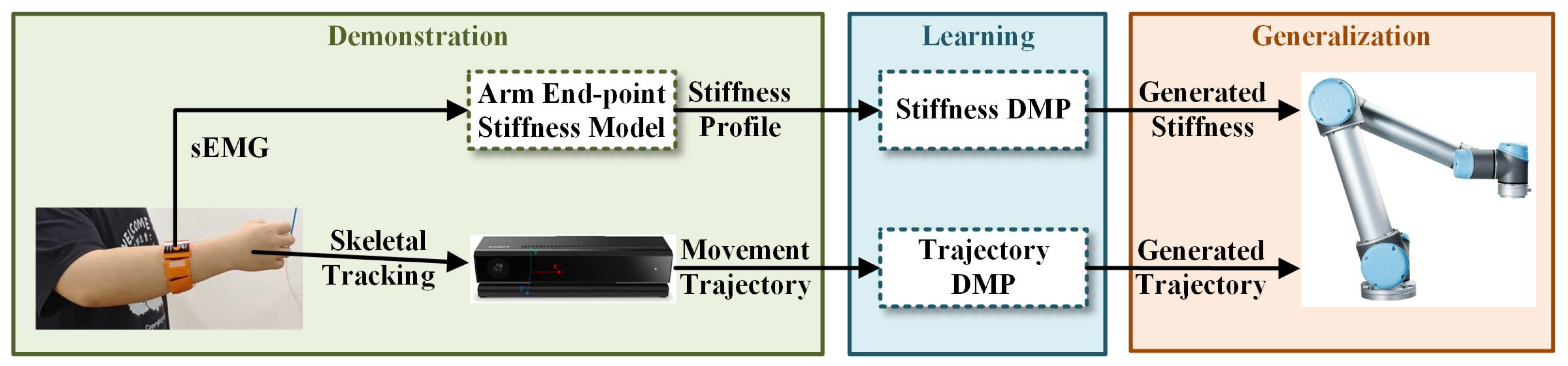

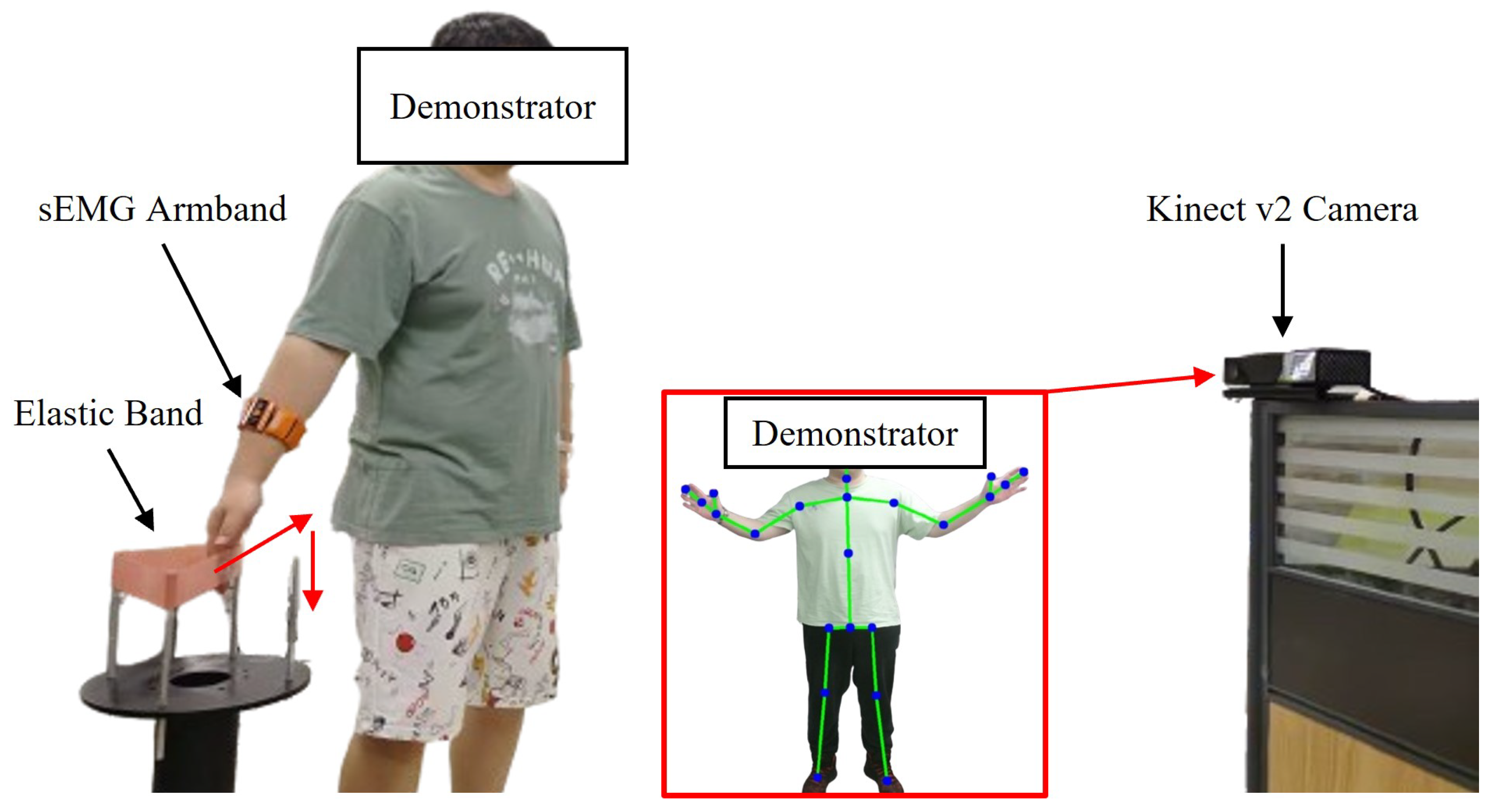

In this paper, we propose a framework enabling robots to learn variable impedance skills from humans and perform contact-rich tasks. In our work, the gForcePro+ sEMG armband is employed to extract surface electromyography (sEMG) signals from the human upper limb and estimate time-varying endpoint stiffness. The motion trajectory of the human demonstrator is captured via a Kinect v2 camera using skeletal tracking. A Dynamic Movement Primitive (DMP)-based imitation learning framework is developed to simultaneously learn both motion trajectories and stiffness profiles. The framework’s efficacy is validated through an elastic bandaging experiment conducted on a UR5 robotic manipulator. The proposed framework is represented in

Figure 1.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section II introduces the DMP model and the methodology for estimating endpoint impedance of the human upper limb. Section III presents impedance estimation experiments and implements the proposed framework on the robot. Section IV concludes the study.

The key contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

This study proposes an sEMG-based method for estimating human upper limb endpoint stiffness to extract impedance characteristics from demonstrations. A novel smoothed stochastic perturbation function significantly mitigates robot oscillations during experiments. Integrated with a vision system to enable indirect teaching —offering non-contact operation and enhanced safety—the estimated stiffness is transferred to the robot, improving task performance while ensuring operational safety.

The DMP framework unifies the learning of motion trajectories and stiffness profiles, enabling skill transfer encompassing both aspects. The framework’s effectiveness is validated through a contact-rich task with variable force dynamics—the elastic bandaging experiment.

2. Methods

2.1. Dynamic Movement Primitives

Dynamic Movement Primitives (DMPs) were initially proposed by Ijspeert et al. [

30] as essentially a spring-damper system governed by a canonical system, and were subsequently refined by Stefan Schaal et al. [

31] in 2008. The one-dimensional discrete DMP model is defined as follows:

where

represents the position and velocity of a certain point in the system.

denotes the initial and goal position of the system. The constant

indicates the spring and damping parameters.

represents the temporal scaling factor.

f is a real-valued nonlinear forcing term that modifies the shape of the motion trajectory.

represents the phase variable that reparameterizes time

, enabling

f to be independent of time

t, and is governed by the canonical system:

where

determines the exponential decay rate of the canonical system. The canonical system is initialized to

, with the phase variable

s monotonically decreasing from 1 to 0, where its convergence rate is positively correlated with parameters

and

.

The nonlinear function f is expressed in terms of basis functions:

where

represents the Gaussian basis function with center

, bandwidth

and weight

, and

N indicates the number of Gaussian basis functions.

Given a demonstration trajectory with position, velocity, and acceleration denoted as

respectively, where

, and

T represents the duration of the demonstration trajectory. The target nonlinear function

can be obtained as:

where

.

Consequently, the learning problem of the demonstration trajectory is transformed into an approximation problem for the target nonlinear function . Locally Weighted Regression (LWR) is employed to determine an optimal set of weights that minimizes the difference between and . The selection of LWR is primarily based on the following considerations: (1) the method exhibits superior computational efficiency, meeting the real-time requirements of one-shot imitation learning; (2) the learning processes of individual model components in LWR are mutually independent, facilitating parallelization of the algorithm.

2.2. sEMG-Based Stiffness Estimation

The end-point impedance of the human upper limb in Cartesian space is typically characterized by coupled mass, damping, and stiffness matrices [

32]:

where

represent the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively, of the upper limb endpoint in Cartesian space;

denotes the external force exerted when the endpoint deviates from its equilibrium position;

indicates the initial equilibrium position of the endpoint; and

represent the current position, velocity, and acceleration of the endpoint.

However, modeling the endpoint impedance of the human upper limb using coupled impedance matrices requires numerous parameters, thus necessitating longer measurement periods to obtain sufficient data variation for ensuring the determinacy of regression results. Prolonged measurement, however, is undesirable as it may incorporate voluntary motion components compensating for perturbations, thereby failing to accurately reflect the impedance level corresponding to pre-perturbation unconscious passive responses. When the duration of the coupled model is reduced to 100-200 ms, the uncertainty increases significantly, rendering the acquisition of physically meaningful impedance values nearly impossible. These challenges may explain why coupling effects have been neglected in several studies [

3]. Building upon this existing research, the present study consequently models the endpoint impedance of the human upper limb as three mutually decoupled mass-damper-spring systems along principal directions:

where

represent the mass, damping, and stiffness parameters, respectively;

denotes the endpoint acceleration;

is the endpoint velocity;

indicates the endpoint position;

corresponds to the target position (i.e., initial equilibrium position) of the upper limb endpoint;

represents the external force acting on the endpoint.

However, extensive experimental trials revealed that obtaining physically meaningful values for the mass parameter

M was nearly impossible, while the damping parameter

B and stiffness parameter

K remained relatively stable. Consequently, Equation

6 was simplified to a damper-spring system:

Based on the decoupled impedance model in three orthogonal directions, this paper derives the following mapping equation between sEMG signals and endpoint stiffness of the human upper limb:

where

represents the endpoint stiffness of the human upper limb;

denote the muscle co-contraction gain and inherent stiffness gain of the arm, respectively; and

S represents the preprocessed sEMG signal.

2.3. Admittance Control

Since the robot outputs position while the environment responds with force - where the robot exhibits admittance characteristics and the environment demonstrates impedance properties - this study employs admittance control:

where

,

and

are the desired mass, damping and stiffness matrices, respectively, with

being either a preset value or the dynamic stiffness during human demonstration;

,

and

x represent the actual acceleration, velocity, and displacement;

,

and

denote the desired acceleration, velocity, and displacement; and

is the interaction force between the robot end-effector and the environment.

Given that the mass matrix

has minimal influence in human-robot collaboration systems and obtaining accurate robot acceleration signals proves challenging in practical applications, the admittance control model is simplified as follows:

3. Experiment

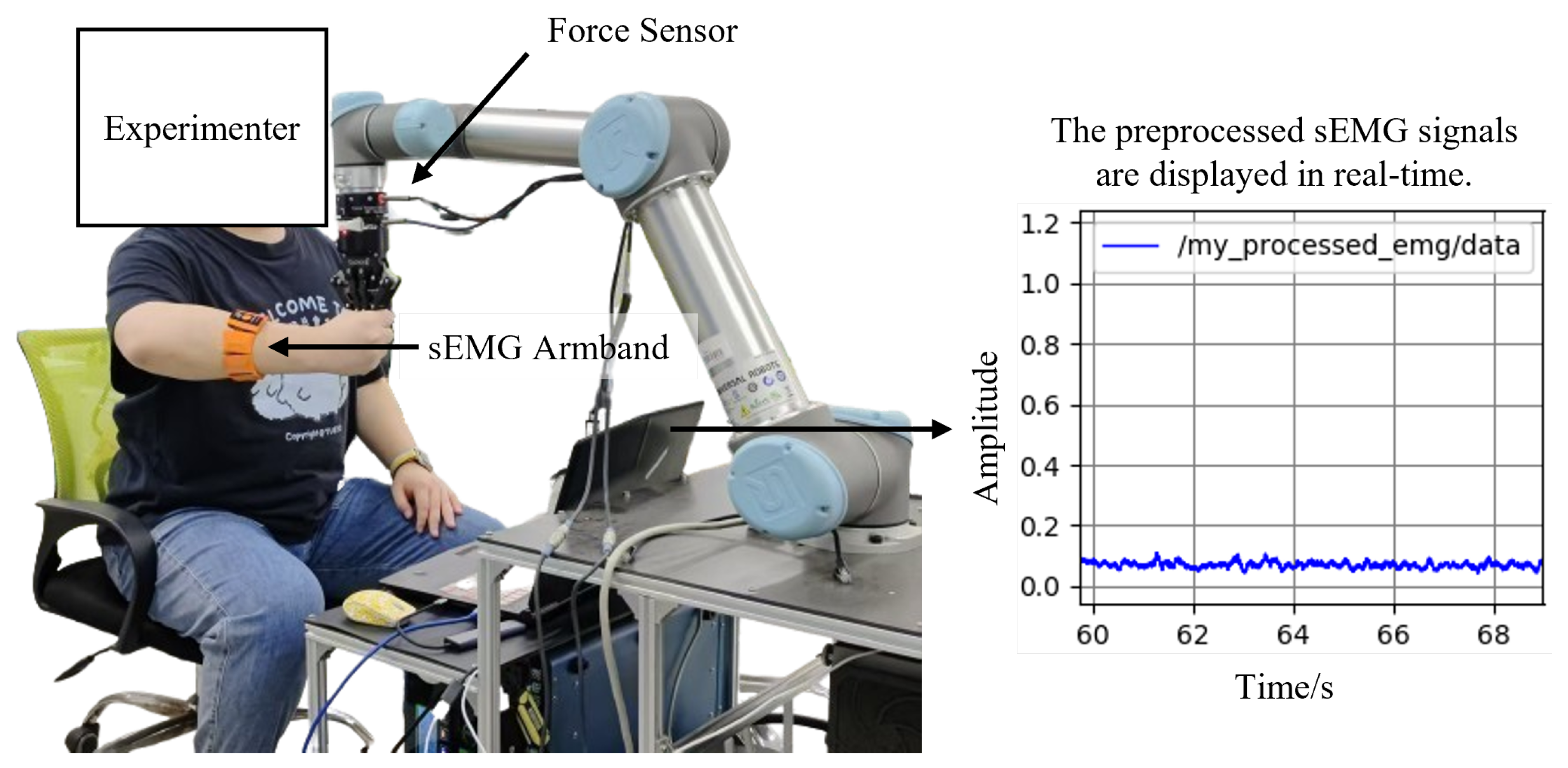

A 6-DOF collaborative robot (UR5) was employed to establish the experimental platform. The gForcePro+ sEMG armband was used to estimate endpoint stiffness from raw sEMG signals of the human demonstrator’s upper limb. A Kinect v2 camera captured motion trajectories of the demonstrator’s right palm through skeletal tracking. The Robot Operating System (ROS) coordinated sensor data transmission and robot control.

3.1. Human Upper Limb Endpoint Impedance Estimation Experiment

Similar to most mechanical perturbation methods, we applied position perturbations in random directions to the human upper limb endpoint. The interaction forces between the human hand and the robot end-effector were measured using a Robotiq Force Torque Sensor FT 300 (6-axis F/T sensor). The endpoint displacement of the human hand was computed from the robot’s joint angles, while sEMG signals were acquired via the gForcePro+ sEMG armband. The setup is shown in

Figure 2.

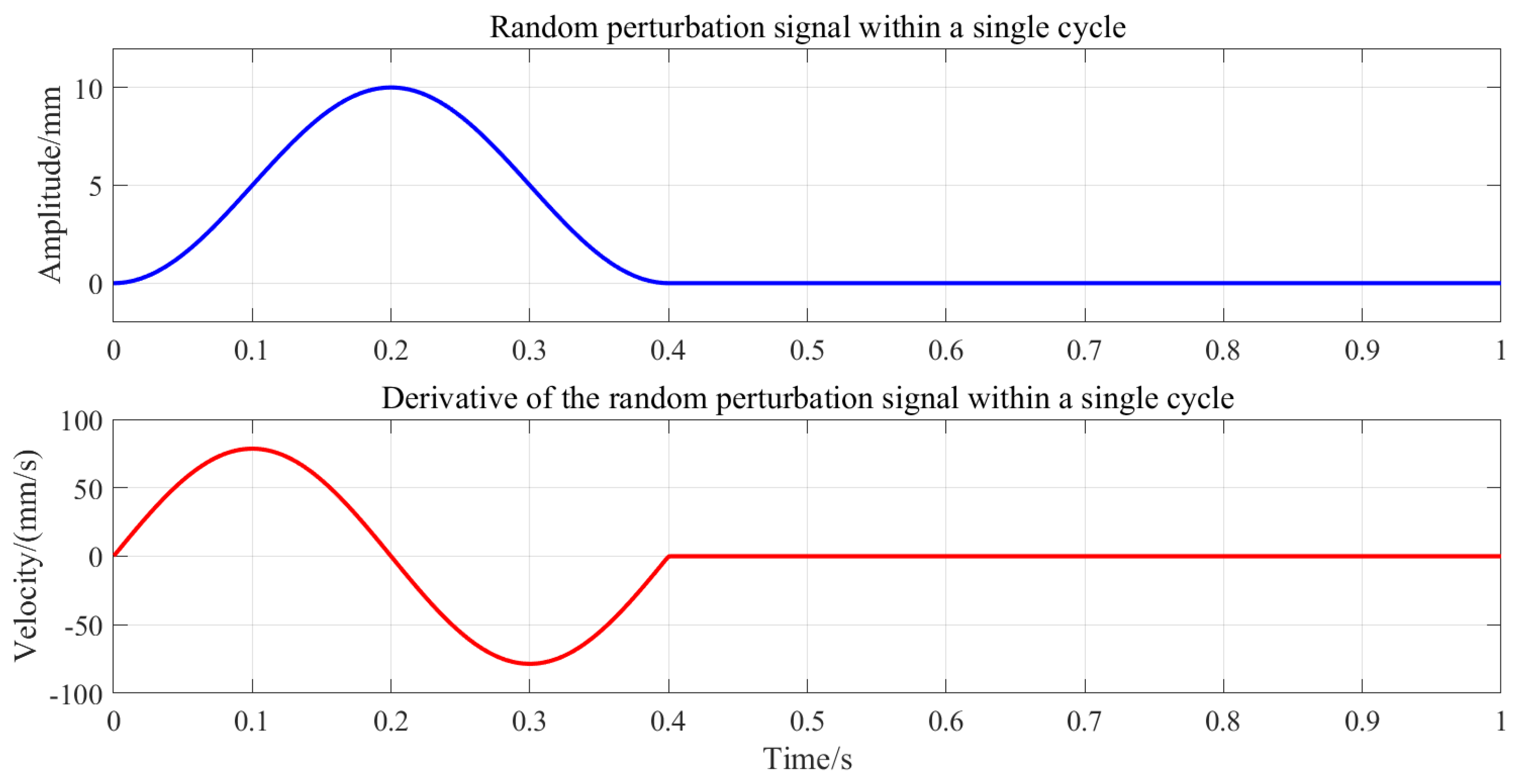

The UR5 robot, operating in position control mode, delivered random perturbations to the upper limb endpoint with the following characteristics:

Perturbation period: 1 s;

Peak-to-peak amplitude: 20 mm;

Smooth perturbation phase: 0-0.4 s (ramp-up/down);

Constant position phase: 0.4-1 s (to avoid interference between consecutive perturbation cycles).

In position control mode, moving the robot end-effector to a specified Cartesian coordinate requires first converting the coordinate into six target joint angles through inverse kinematics calculations. These joint angles are then transmitted to the robot controller to execute the movement. However, if only the start and end points are provided, allowing the robot controller to autonomously plan the trajectory, the resulting motion approximates uniform velocity (constant angular velocity), which fails to account for velocity’s influence on damping parameters. Moreover, when the end-effector reaches the target and reverses direction, abrupt velocity changes occur, inducing robot oscillations.

To address these issues, this experiment employs a smooth symmetric function to generate random perturbation signals with a peak amplitude of ±10 mm. The sampled signal is then used for trajectory planning as follows:

where

is the initial offset,

is the perturbation amplitude, and

T is the perturbation period.

The function employs a squared-sinusoidal form to ensure smoothness and symmetry of the perturbation signal, eliminating abrupt transitions or spikes. This design achieves stable and controllable periodic perturbations during experiments, effectively preventing robot oscillations caused by sudden velocity changes. Moreover, the incorporated nonlinear variations enable better characterization of velocity

v effects on the system, overcoming the difficulty of distinguishing contributions between damping

B and stiffness

K parameters under near-constant velocity conditions. The perturbation amplitude

A and period

T can be adjusted flexibly to meet experimental requirements.

Figure 3 illustrates a single-cycle random perturbation signal and its time derivative:

The velocity plot confirms zero-speed conditions at both initial and target positions, eliminating oscillation risks from velocity discontinuities.

Prior to the experiment, the subject’s right hand grasped the robot arm’s end-effector while maintaining arm muscle activation at prescribed levels (10%, 30%, 50%). During trials, 30-second random perturbations were applied to the robotic arm in ±X, ±Y, and ±Z directions, inducing corresponding arm movements. The first 5 seconds of data were discarded to eliminate initial adaptation effects.

Three random perturbation trials were conducted at each muscle activation level, totaling 9 trials. The sEMG preprocessing pipeline comprises 6 steps: eight-channel averaging, linear denoising, full-wave rectification, bandpass filtering (using a 4th-order Butterworth filter with 30-100 Hz cutoff frequencies), moving average, and normalization (scaling sEMG signals to

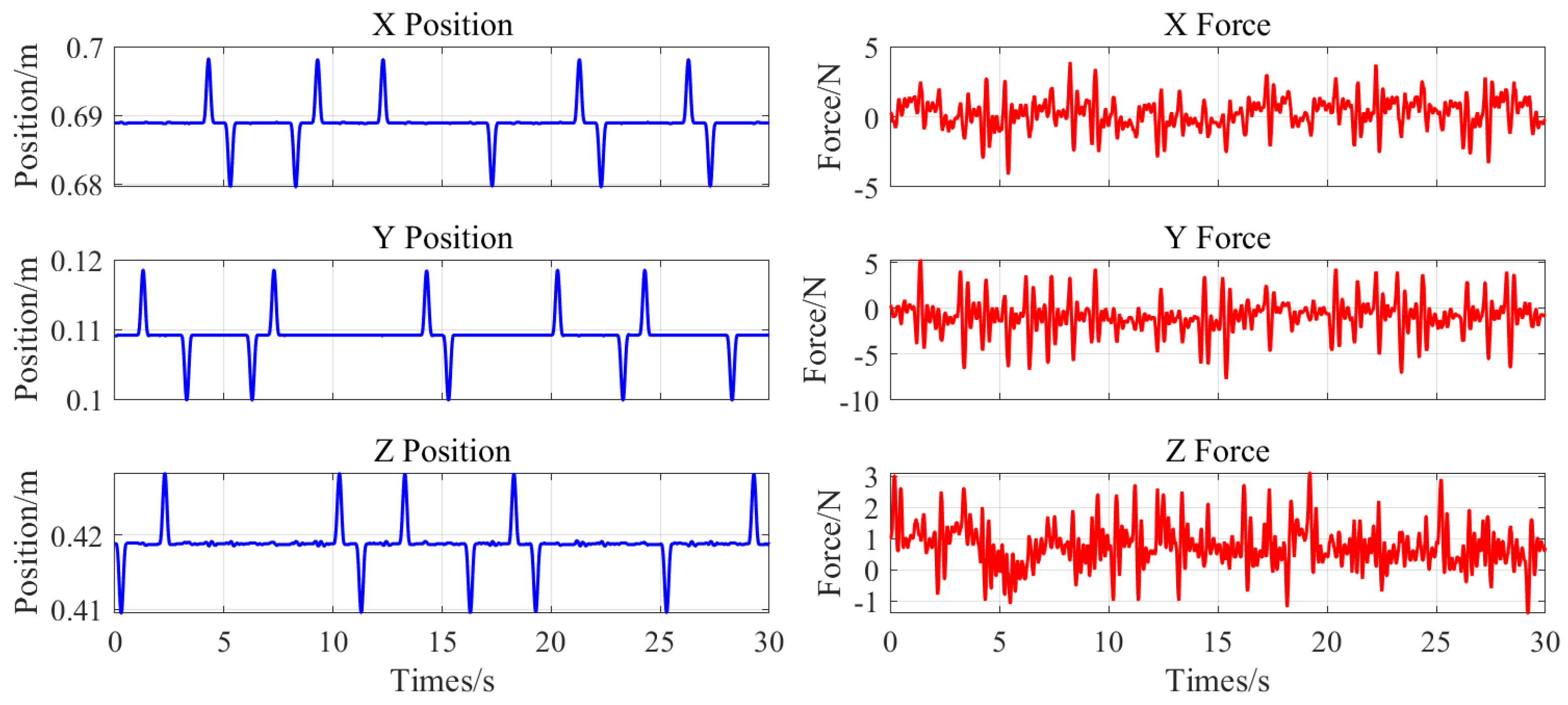

).

Figure 4 demonstrates an example of preprocessed sEMG signals. Force and position data were smoothed using moving average filtering, followed by velocity and acceleration calculations derived from the position data. Only the first 200 ms of each perturbation cycle were analyzed to ensure physically meaningful results [

3]. Portions of the collected force and position data are shown in the Figure. The least squares method was applied to averaged sEMG signals. After excluding non-physical outcomes, mean impedance parameters were computed across activation levels to establish the sEMG-to-stiffness mapping relationship.

3.2. Human-Robot Skill Transfer Experiment

The elastic bandaging experiment was designed to validate the proposed human-robot skill transfer system, comprising demonstration and reproduction phases. During demonstration, the human demonstrator faced the Kinect v2 camera while wearing an sEMG armband on the right forearm. The Kinect captured the right palm’s motion trajectory through skeletal tracking, while the armband recorded raw sEMG signals. In the reproduction phase, the robot replicated the demonstrated skill and generalized it to different scenarios.

The elastic bandaging experimental setup is shown in the

Figure 6, where red arrows indicate the motion trajectory of the human demonstrator’s right hand. A 10-pound elastic band was mounted on an iron column for this experiment. The core objective was to teach the robot to stretch and place the elastic band onto the column. During initial contact with the band, the human demonstrator maintained relaxed arm muscles, resulting in low-level sEMG signals. Due to the spring-like properties of the elastic band, the interaction force increased as the band was stretched. Consequently, the demonstrator applied greater force to complete the task, with muscle activation levels progressively rising as the band approached the column’s top - reflected in corresponding sEMG amplitude increases. In the demonstration phase, both motion trajectories and stiffness modulation were taught: maintaining compliance when unnecessary (non-stretching phases) and adopting high stiffness when required (band-stretching phases). The 10-pound elastic band was selected for its ease of stretching. The robot controller’s stiffness was set to twice that of the human arm’s endpoint stiffness to fully utilize the robot’s control capabilities.

During the reproduction phase, the robot was tasked with executing both reproduction and generalization tasks. The experimental results were evaluated based on whether the elastic band was successfully positioned outside the metal pole (success) or not (failure). For the reproduction task, a 10-pound elastic band was used, requiring the robot to independently perform the learned band-stretching skill. The desired motion trajectory matched the human demonstrator’s trajectory from the teaching phase, while the target stiffness corresponded to the originally estimated endpoint stiffness of the human upper limb.

One advantage of this framework is its capability to flexibly adjust parameters of learned skills, such as modifying trajectory endpoints and stiffness profiles, to accommodate new task requirements. For the generalization tasks, two different scenarios were designed to evaluate and extend the robot’s learned skills:

Subtask 1: The DMP generated the original motion trajectory and stiffness profile, using a 20-pound elastic band.

Subtask 2: The DMP generated the original motion trajectory but with generalized stiffness, using a 20-pound elastic band.

4. Result and Discussion

This section presents the experimental results of upper-limb endpoint impedance estimation and the human-robot skill transfer experiment - the elastic bandaging task.

4.1. Human Upper Limb Endpoint Impedance Estimation Experiment

After performing least squares calculations according to the Equation

7 and removal of invalid data, the endpoint impedance parameters of the upper limb were obtained for three different muscle activation levels, as shown in the

Table 1. Both damping and stiffness values were positive and exhibited systematic variations with muscle activation levels, thereby validating the rationality of the simplified upper limb impedance model employed in this study. The stiffness and damping values differed among the X, Y, and Z directions because the projection lengths of the human upper limb’s endpoint stiffness ellipsoid vary along these three axes. The impedance parameters in the X and Y directions were similar in magnitude and greater than those in the Z direction, indicating higher robustness of the human upper limb in the XOY plane and its capacity to exert greater forces in these directions.

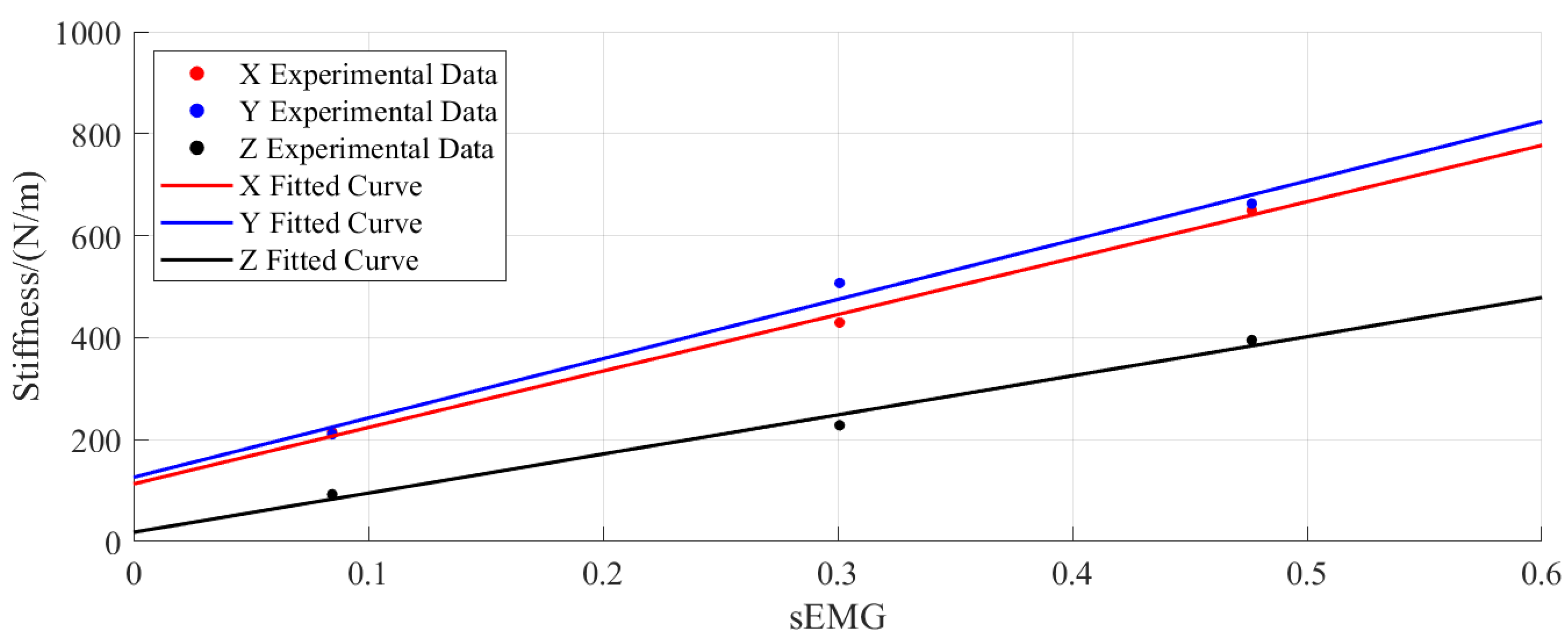

The impedance parameters obtained from calculations and the proposed formula were used to derive the mapping parameters between sEMG signals and endpoint stiffness of the human upper limb through least squares method, as presented in the

Table 2. The fitted curves for the mapping parameters from sEMG signals to endpoint stiffness of the human upper limb are shown in

Figure 7. The plots demonstrate that the sEMG-estimated endpoint stiffness exhibits similar variation trends in all three Cartesian directions (X, Y, Z), with approximately linear relationships observed between sEMG signals and directional stiffness values. These results demonstrate that the mapping relationship established in Equation

8 effectively captures the variation characteristics of endpoint stiffness, thereby validating the rationality of this mapping model.

4.2. Human-Robot Skill Transfer Experiment

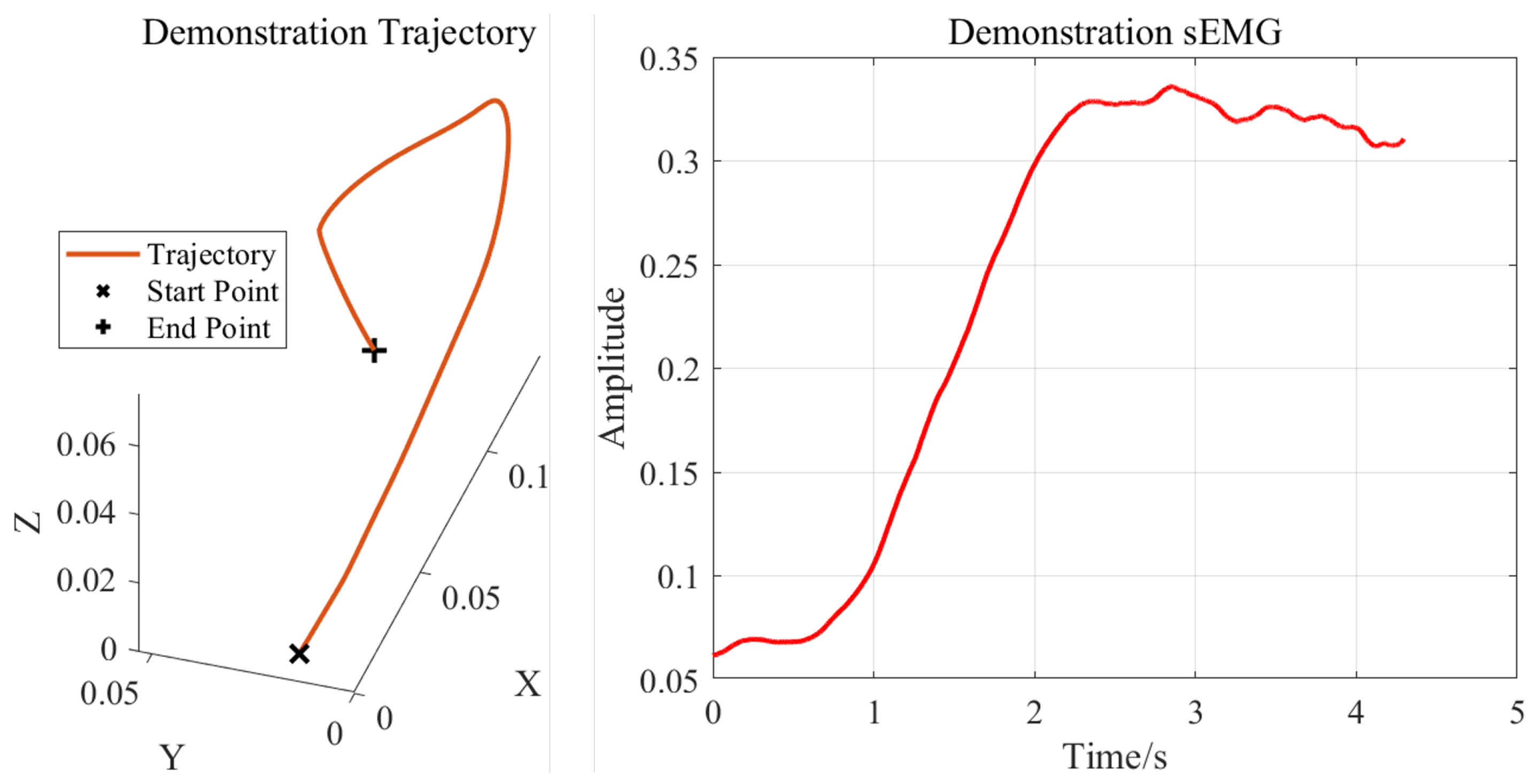

After establishing the mapping relationship from sEMG to endpoint stiffness, we can transfer the human demonstrator’s teaching information (including both stiffness and motion trajectories) to the robot. The smoothed motion trajectory of the right palm and the upper-limb sEMG signals obtained during the demonstration phase are shown in the

Figure 8. Benefiting from the one-shot learning capability of the DMP model, the human demonstrator only needs to perform a single demonstration.

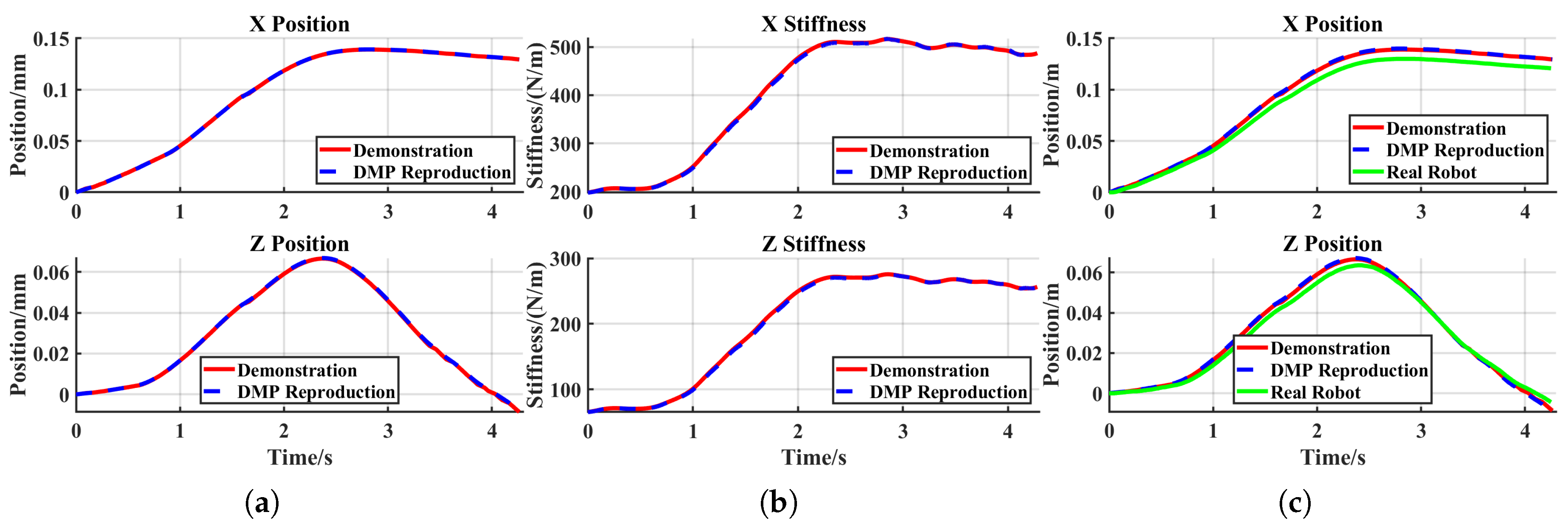

4.2.1. Reproduction Task

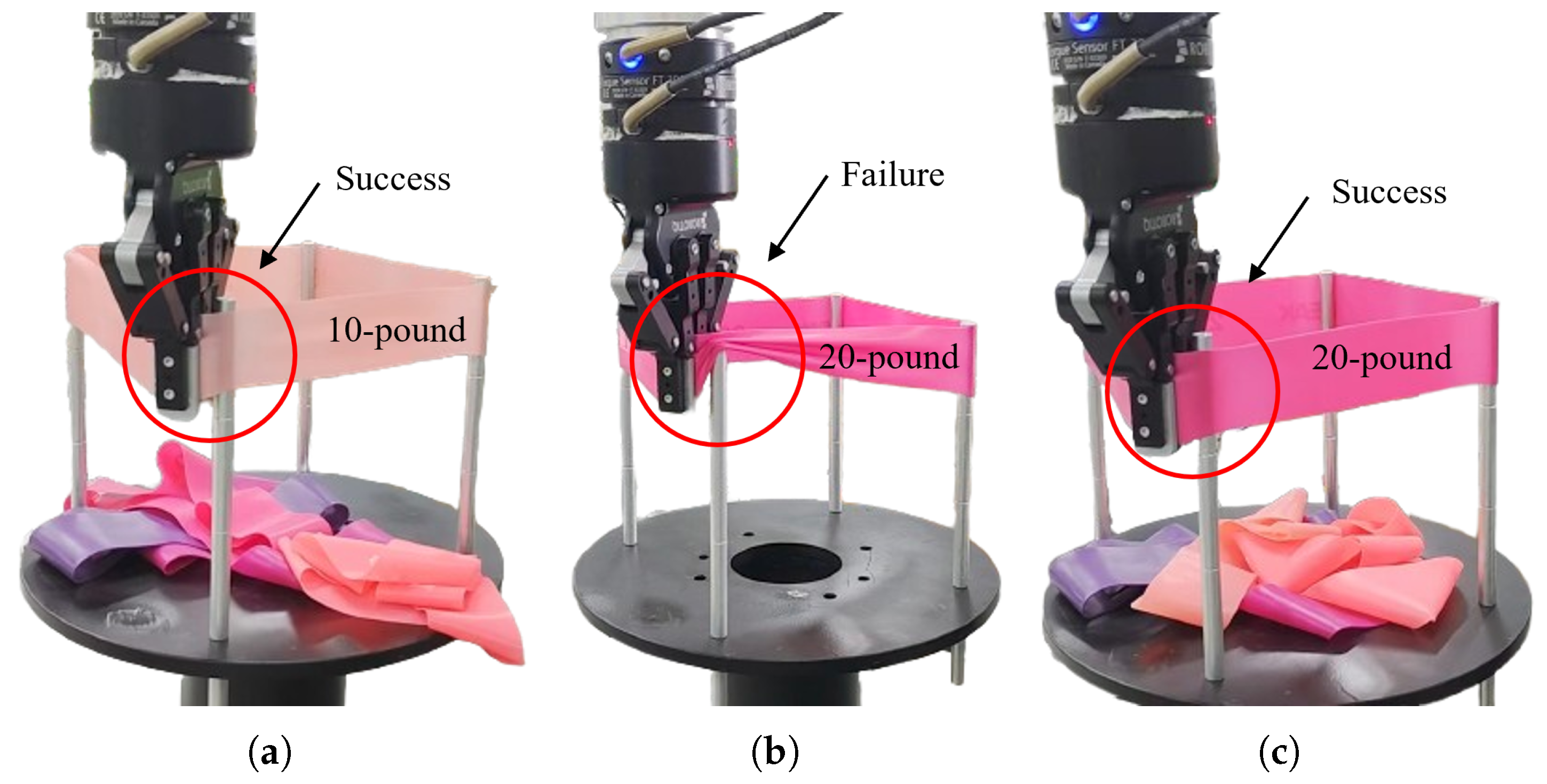

In the reproduction task, the robot successfully stretched the elastic band outside the metal pole, demonstrating effective acquisition of the original skill, as shown in the

Figure 9 (

a). Since the displacement in this task primarily occurs along the X and Z axes, only the data for these two axes are presented, as shown in the

Figure 10.

The

Figure 10 reveals that admittance control inevitably introduces tracking errors when external forces are applied, with stiffness regulating the magnitude of these errors. During the robot’s reproduction task, the generated tracking errors remained sufficiently small, thereby ensuring experimental success.

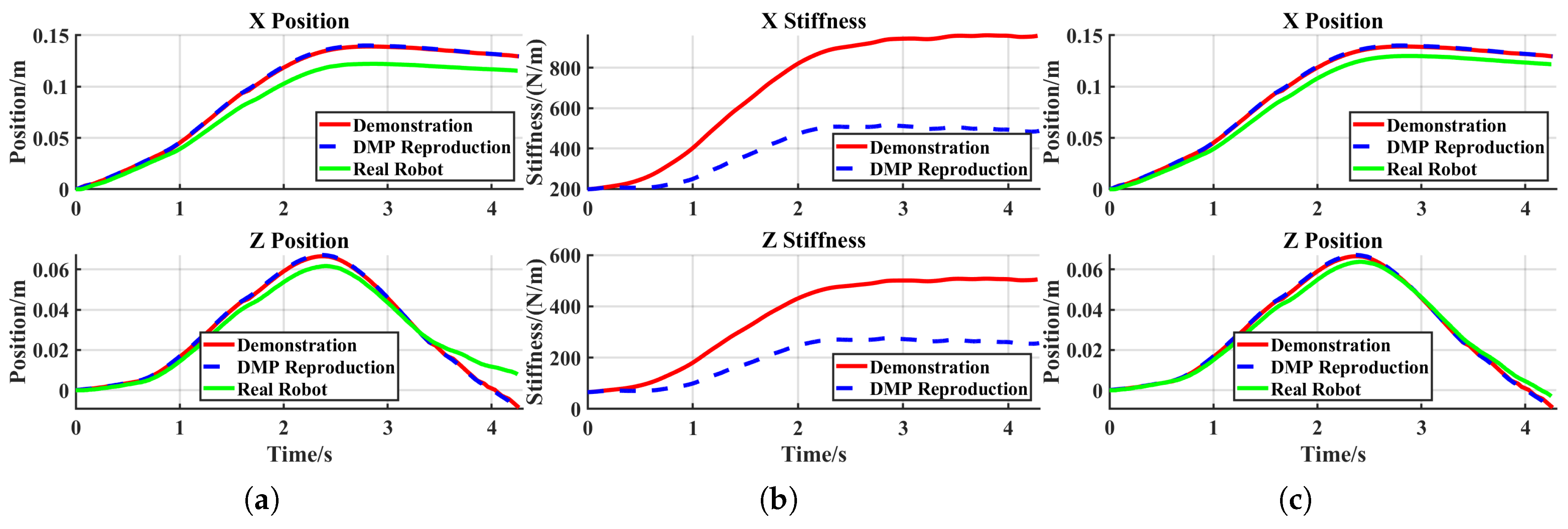

4.2.2. Generalization Task

Generally, elastic bands with higher pounds require greater stretching forces and are more difficult to elongate. As clearly shown in the

Figure 9 (

b), subtask 1 failed under these conditions. A comparison between

Figure 10 (

c) and

Figure 11 (

a) reveals a significant increase in the robot’s tracking error. To enable successful band stretching despite increased resistance, the robot must maintain smaller tracking errors when subjected to larger external forces. This necessitates higher stiffness, achieved by doubling the target stiffness in the stiffness DMP relative to the demonstration values (

Figure 11 (

b)). As shown in

Figure 11 (

c), the robot in subtask 2 maintained satisfactory trajectory tracking despite experiencing greater external forces, ultimately achieving successful task completion (

Figure 9 (

c)).

5. Discussion

Collaborative robots operating solely on pre-defined motion trajectories face significant limitations in executing complex manipulation skills, particularly during environmental contact. Such trajectory-centric control is inherently vulnerable to disturbances and can lead to dangerously high contact forces under position control, posing risks to both the robot and nearby humans. To bridge this gap and achieve safe, adaptable, and skillful contact-rich manipulation, robots must dynamically modulate their physical interaction behaviour through impedance adaptation. The core principle is task-dependent: maintaining high endpoint stiffness when precise positioning or force exertion is critical, while exhibiting high compliance to absorb impacts and conform to surfaces during uncertain contact scenarios. This dual capability is essential; maximizing compliance enhances safety for humans and the environment by limiting interaction forces, whereas persistently high stiffness not only risks damage but also increases the likelihood of abrupt stops and instability due to unintended high output torques triggered by minor perturbations or model inaccuracies.

Our core contribution lies in providing a principled framework that transcends simple trajectory replication. We address the critical challenge of transferring not just the kinematic motion, but crucially, the impedance strategy exhibited by human demonstrators during contact-rich tasks. Humans intuitively modulate their limb impedance based on task phase and contact expectations. Our method captures this nuanced skill through sEMG-based stiffness estimation, which enables direct mapping of human muscular activation patterns to robotic impedance parameters. Crucially, the framework is designed for generalizability. By incorporating the key task parameter - execution stiffness - as input, the learned impedance behaviour can be effectively adapted to novel but related task requirements through straightforward parameter adjustments, significantly expanding the operational envelope beyond the initial demonstrations.

Looking forward, our work opens avenues for further sophistication in physical human-robot collaboration (pHRC). Future research will focus on expanding the scope of impedance adaptation, particularly by integrating real-time estimation of human-applied forces/torques to enable more responsive and intuitive co-manipulation. Furthermore, enhancing generalization convenience is paramount. We plan to integrate more sophisticated task parameterization and context-awareness methods to allow robots to autonomously infer suitable impedance parameters for a wider range of unseen tasks, moving closer to truly versatile and safe collaborative manipulation.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we present a DMP-based imitation learning framework for transferring human-demonstrated skills to robots, enabling the acquisition and generalization of human operational skills incorporating both trajectory and stiffness information. The framework aims to enhance both performance and safety during robotic contact tasks. Our approach integrates the advantages of DMP models with sEMG-based variable admittance control. Experimental validation was conducted on a physical 6-DOF robotic platform. The elastic bandaging task demonstrates the framework’s effectiveness in executing contact-rich manipulations.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.Z.; software, H.Z.; validation, H.Z. and F.P.; formal anal-ysis, H.Z.; writing-original draft preparation, H.Z.; writing-review and editing, H.Z., F.P. and M.C.; supervision, F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding: This research was funded by the Social Public Welfare and Basic Research Project of Zhongshan City (Grant 2023B2011).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ludvig, D.; Whitmore, M.W.; Perreault, E.J. Leveraging joint mechanics simplifies the neural control of movement. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 2022, 16, 802608. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavian, R.S.; Sadeghi, M.; Bazzi, S.; Nayeem, R.; Sternad, D. Body mechanics, optimality, and sensory feedback in the human control of complex objects. Neural computation 2023, 35, 853–895. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erden, M.S.; Billard, A. End-point impedance measurements across dominant and nondominant hands and robotic assistance with directional damping. IEEE transactions on cybernetics 2014, 45, 1146–1157. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z.; Jiang, G.; Zhao, F.; Wu, Y.; Yue, Y.; Mei, X. Dynamic skill learning from human demonstration based on the human arm stiffness estimation model and Riemannian DMP. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2022, 28, 1149–1160. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, T.T.; Rahman, M.M.; Khan, M.R.; Rashid, F.; Sarker, M.R.I. Mapping of human arm impedance characteristics in spatial movements. Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics 2022, 11, 498–509. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Chen, Y. Variable admittance time-delay control of an upper limb rehabilitation robot based on human stiffness estimation. Mechatronics 2023, 90, 102935. [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Li, Z.; Huang, M.; Li, X.; Han, J. Patient’s healthy-limb motion characteristic-based assist-as-needed control strategy for upper-limb rehabilitation robots. Sensors 2024, 24, 2082. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, K.; Si, W.; Li, J.; Yang, C. Neuroadaptive Admittance Control for Human–Robot Interaction With Human Motion Intention Estimation and Output Error Constraint. IEEE transactions on cybernetics 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrante, L.; Sridharan, M.; Zito, C.; Farina, D. Toward a framework for adaptive impedance control of an upper-limb prosthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.04937 2022. arXiv:2209.04937.

- Zhang, L.; Long, J.; Zhao, R.; Cao, H.; Zhang, K. Estimation of the continuous pronation–supination movement by using multichannel EMG signal features and Kalman filter: Application to control an exoskeleton. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2022, 9, 771255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, G.; Ding, Z.; Guo, H.; Song, M.; Jiang, F. Estimation of Lower Limb Joint Angles Using sEMG Signals and RGB-D Camera. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1026. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Zhong, J.; Hu, Y. Augmented Kinesthetic Teaching: Enhancing Task Execution Efficiency through Intuitive Human Instructions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00262 2023. arXiv:2312.00262.

- Mehta, S.A.; Parekh, S.; Losey, D.P. Learning latent actions without human demonstrations. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 7437–7443.

- Ablett, T.; Limoyo, O.; Sigal, A.; Jilani, A.; Kelly, J.; Siddiqi, K.; Hogan, F.; Dudek, G. Multimodal and force-matched imitation learning with a see-through visuotactile sensor. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Xu, H. A wearable robotic hand for hand-over-hand imitation learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 18113–18119.

- Jonnavittula, A.; Parekh, S.; P Losey, D. View: Visual imitation learning with waypoints. Autonomous Robots 2025, 49, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Hielscher, T.; Bulling, A.; Arras, K.O. Interactive Expressive Motion Generation Using Dynamic Movement Primitives. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.06735 2025. arXiv:2504.06735.

- Yue, C.; Gao, T.; Lu, L.; Lin, T.; Wu, Y. Probabilistic movement primitives based multi-task learning framework. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2024, 191, 110144.

- Li, J.; Han, H.; Hu, J.; Lin, J.; Li, P. Robot Learning Method for Human-like Arm Skills Based on the Hybrid Primitive Framework. Sensors 2024, 24, 3964. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nematollahi, I.; Yankov, K.; Burgard, W.; Welschehold, T. Robot Skill Generalization via Keypoint Integrated Soft Actor-Critic Gaussian Mixture Models. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Experimental Robotics. Springer, 2023, pp. 168–180.

- Xu, Y.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Hsu, D. On the Effective Horizon of Inverse Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.06541 2023. arXiv:2307.06541.

- Ren, J.; Swamy, G.; Wu, Z.S.; Bagnell, J.A.; Choudhury, S. Hybrid inverse reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.08848 2024. arXiv:2402.08848.

- Beliaev, M.; Pedarsani, R. Inverse Reinforcement Learning by Estimating Expertise of Demonstrators. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2025, Vol. 39, pp. 15532–15540.

- Tsurumine, Y.; Matsubara, T. Goal-aware generative adversarial imitation learning from imperfect demonstration for robotic cloth manipulation. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2022, 158, 104264. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wan, W.; Wang, H. Learning category-level generalizable object manipulation policy via generative adversarial self-imitation learning from demonstrations. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7, 11166–11173. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, H.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y. An Enhanced DMP Approach for Robotic Manipulator Autonomous Obstacle Avoidance Using Dynamic Potential Function. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Robotics and Applications. Springer, 2024, pp. 365–380.

- Coelho, L.; Cerqueira, S.M.; Martins, V.; André, J.; Santos, C.P. A DMPs-based approach for human-like robotic movements. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Autonomous Robot Systems and Competitions (ICARSC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 201–206.

- Lauretti, C.; Tamantini, C.; Zollo, L. A new dmp scaling method for robot learning by demonstration and application to the agricultural domain. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 7661–7673. [CrossRef]

- Boas, A.V.; André, J.; Cerqueira, S.M.; Santos, C.P. A dmps-based approach for human-robot collaboration task quality management. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Autonomous Robot Systems and Competitions (ICARSC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 226–231.

- Ijspeert, A.J.; Nakanishi, J.; Schaal, S. Movement imitation with nonlinear dynamical systems in humanoid robots. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No. 02CH37292). IEEE, 2002, Vol. 2, pp. 1398–1403.

- Park, D.H.; Hoffmann, H.; Pastor, P.; Schaal, S. Movement reproduction and obstacle avoidance with dynamic movement primitives and potential fields. In Proceedings of the Humanoids 2008-8th IEEE-RAS international conference on humanoid robots. IEEE, 2008, pp. 91–98.

- Perreault, E.J.; Kirsch, R.F.; Crago, P.E. Voluntary control of static endpoint stiffness during force regulation tasks. Journal of neurophysiology 2002, 87, 2808–2816. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).