Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

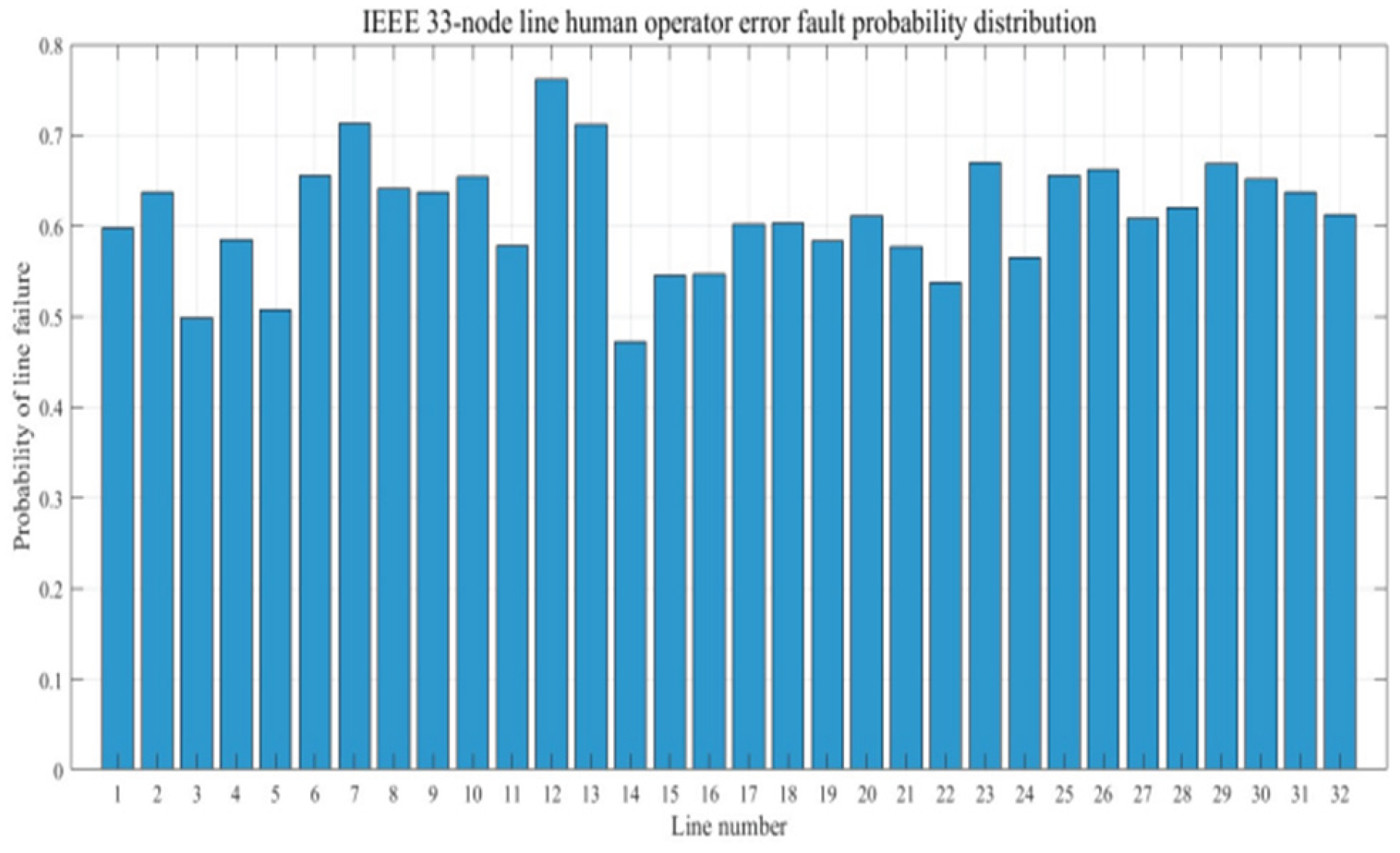

2. Probability of Human Error in Operation Failure

2.1. Classification of Human Operation Errors

2.2. Comprehensive Probability Model

3. The Indicators for Evaluating Self Healing Control of Human Errors

3.1. Core Evaluation Indicators

3.1.1. Self-Healing Recovery Rate

3.1.2. Self-Healing Speed

3.1.3. The Complexity of Self-Healing Operations

3.2. Comprehensive Evaluation Indicators

4. Power Model of Distributed Sources

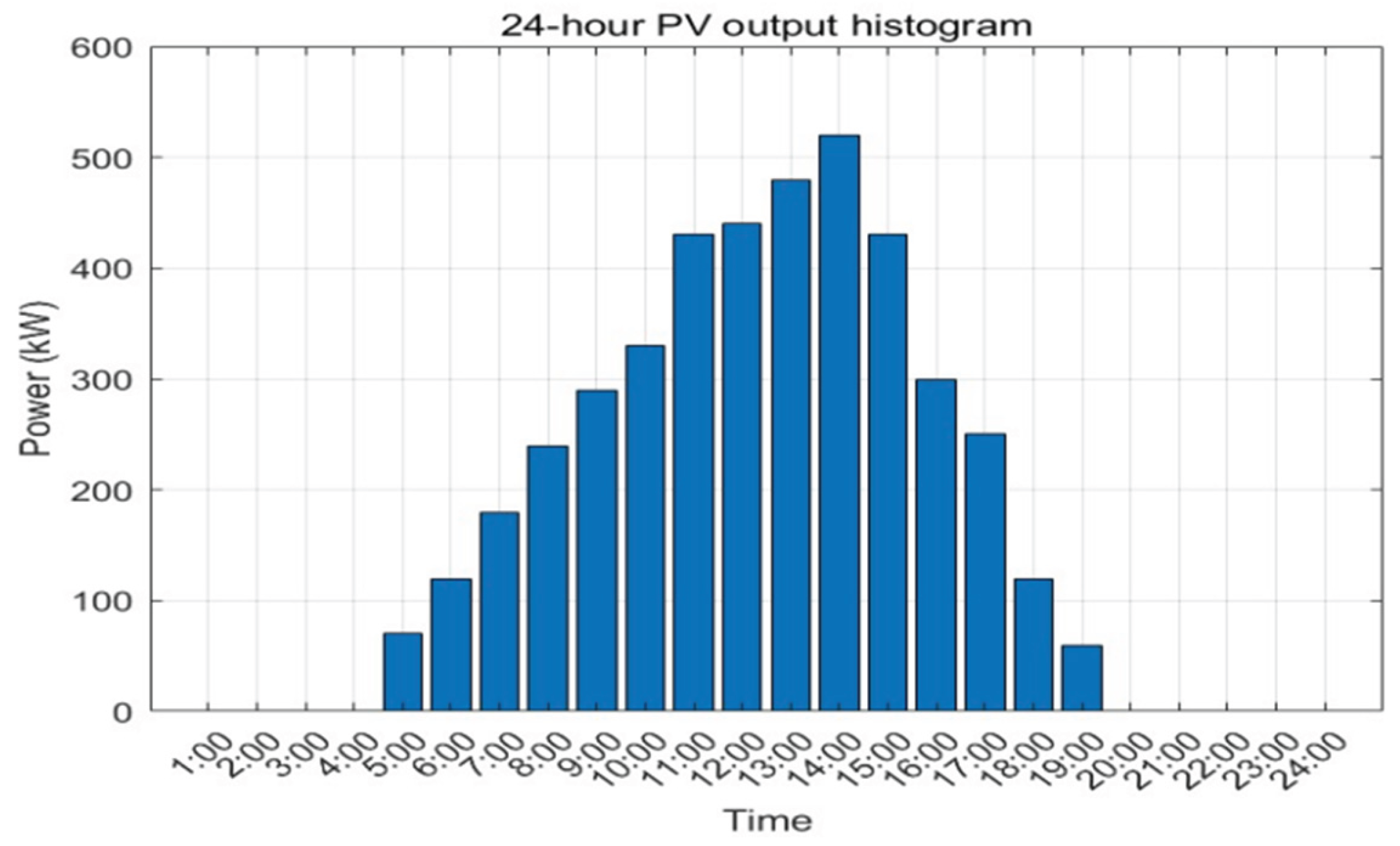

4.1. Probability Model for Photovoltaic Power Generation

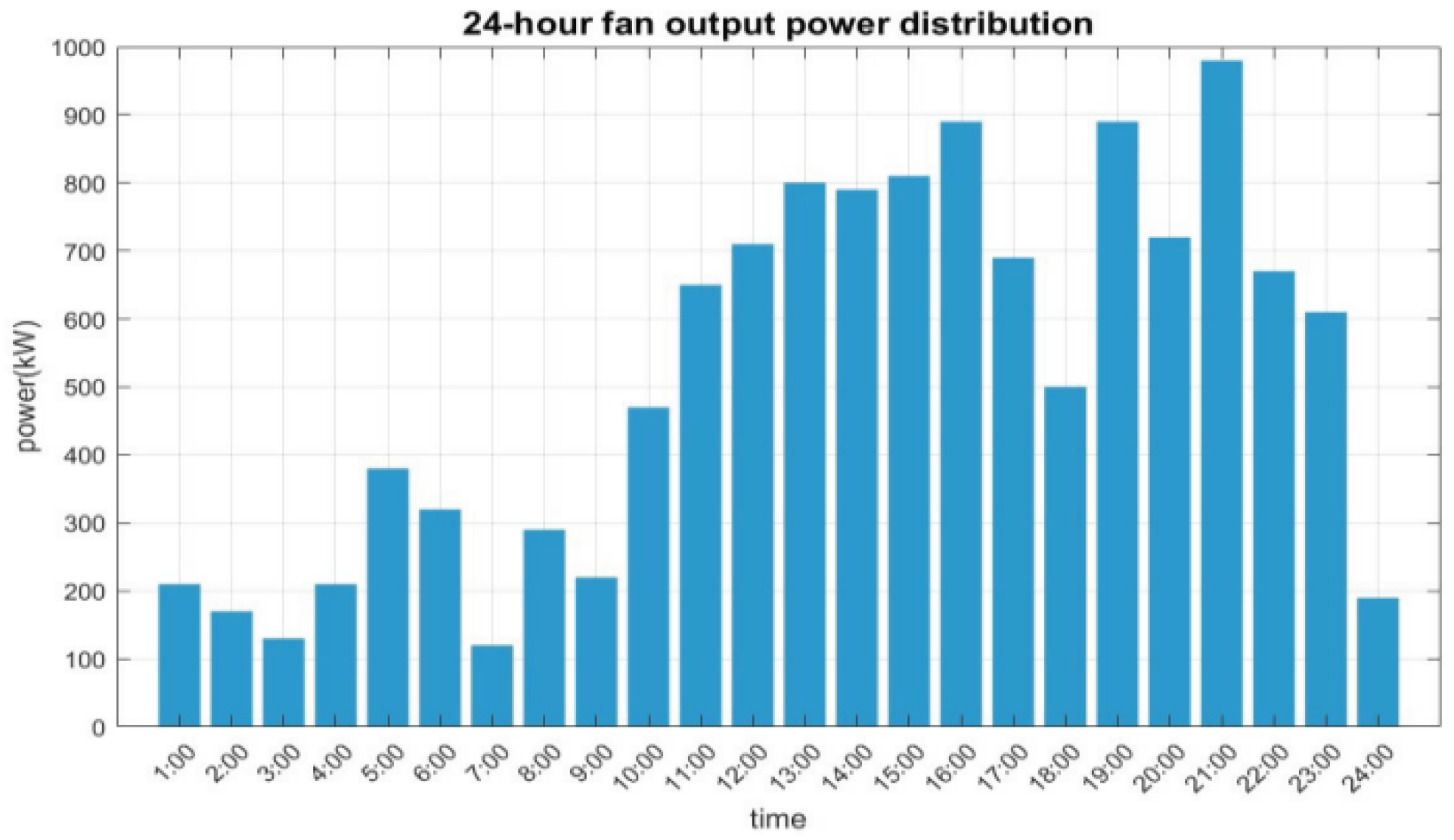

4.2. Probability Model for Wind Power Generation

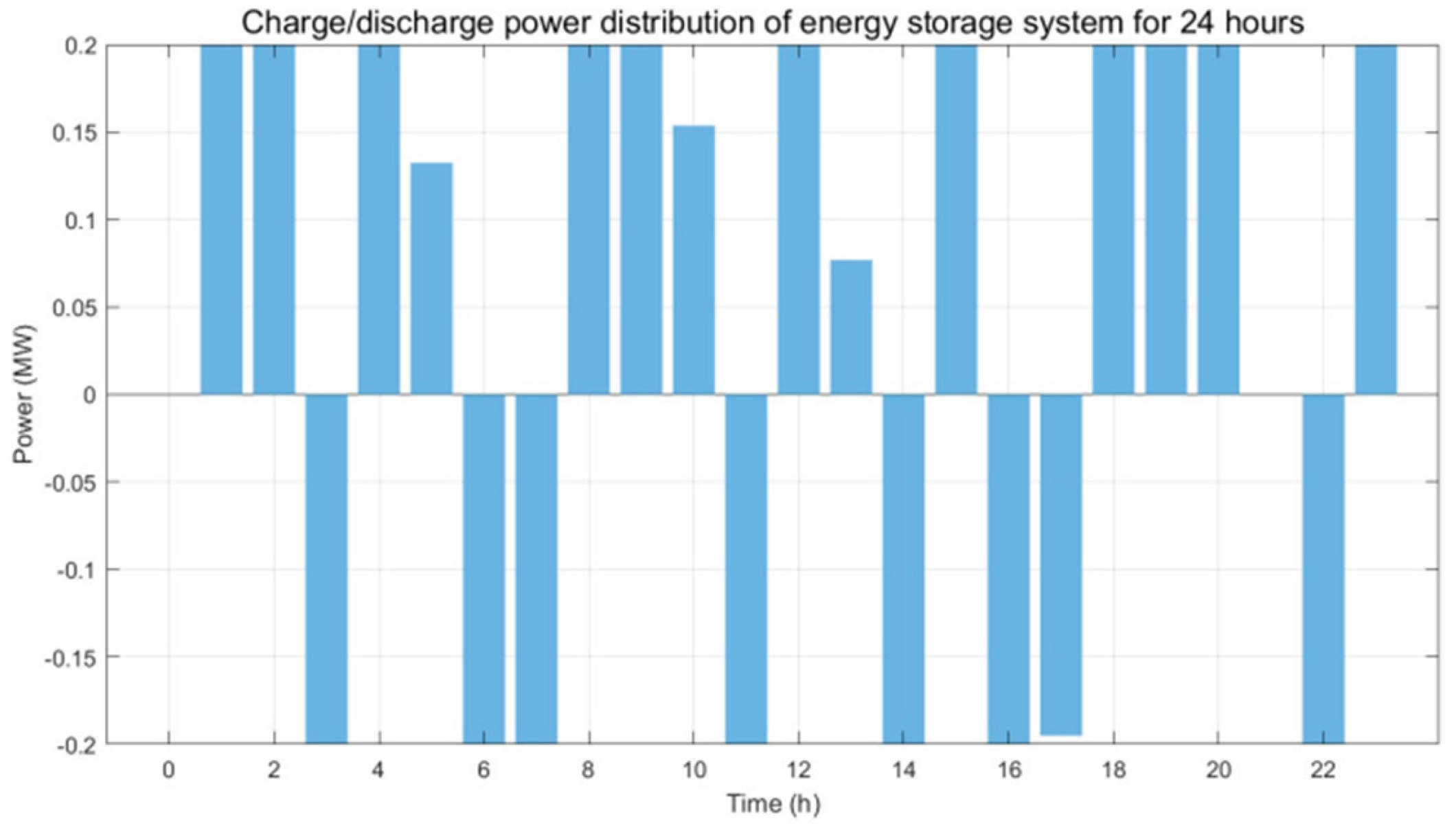

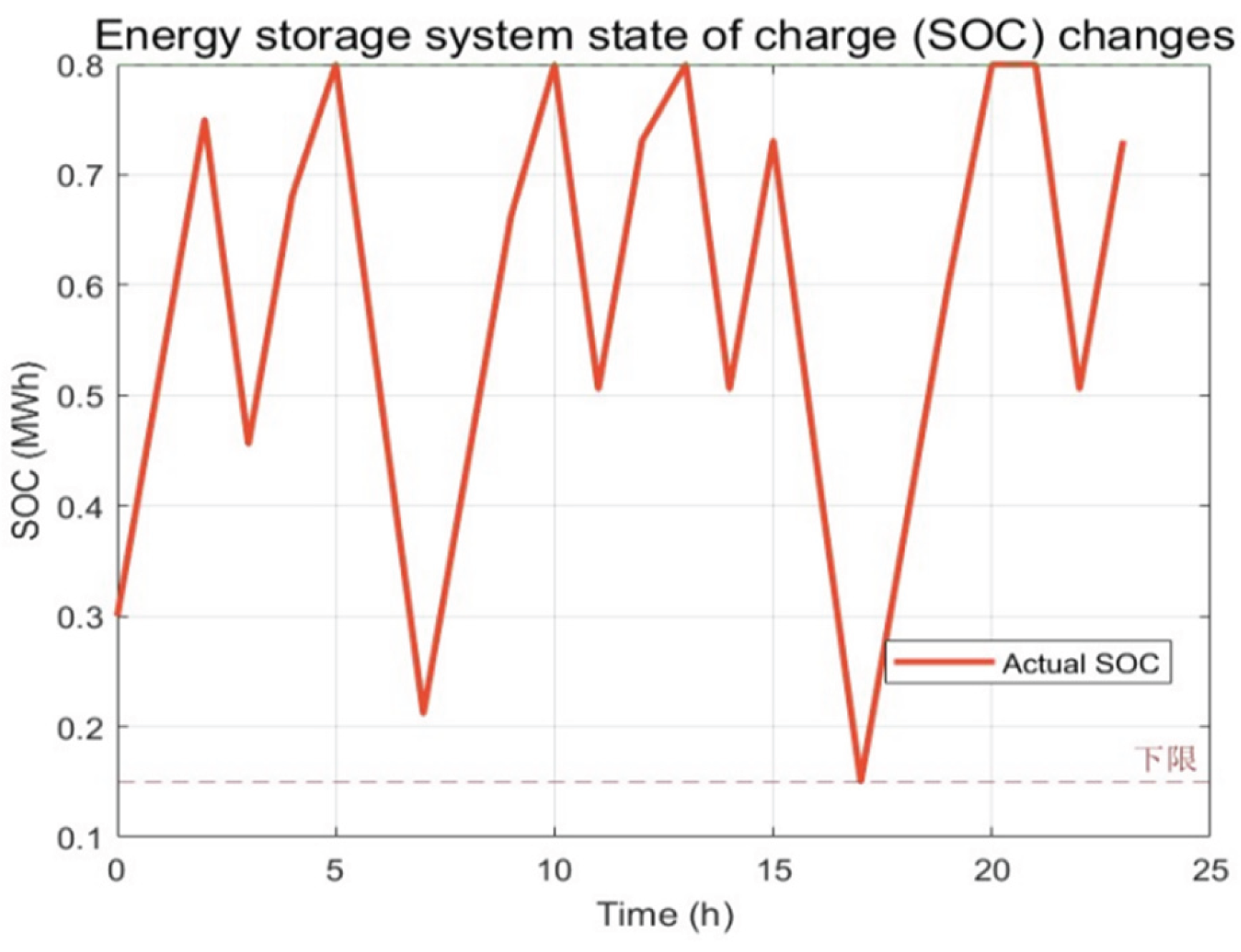

4.3. State of Charge Function of Battery

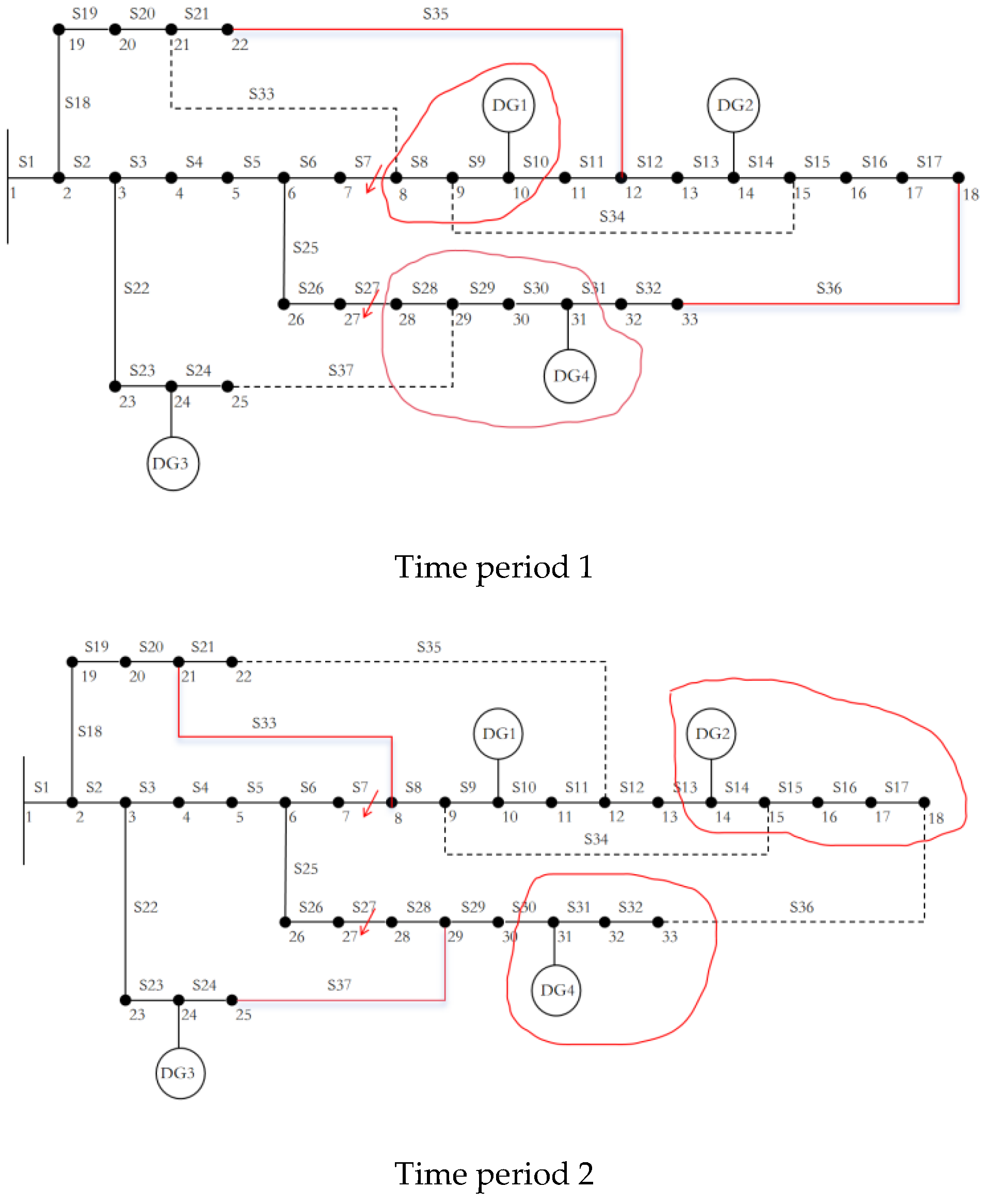

5. Island Partitioning Method

5.1. The Objective Function for Island Partitioning

5.2. The Constraints

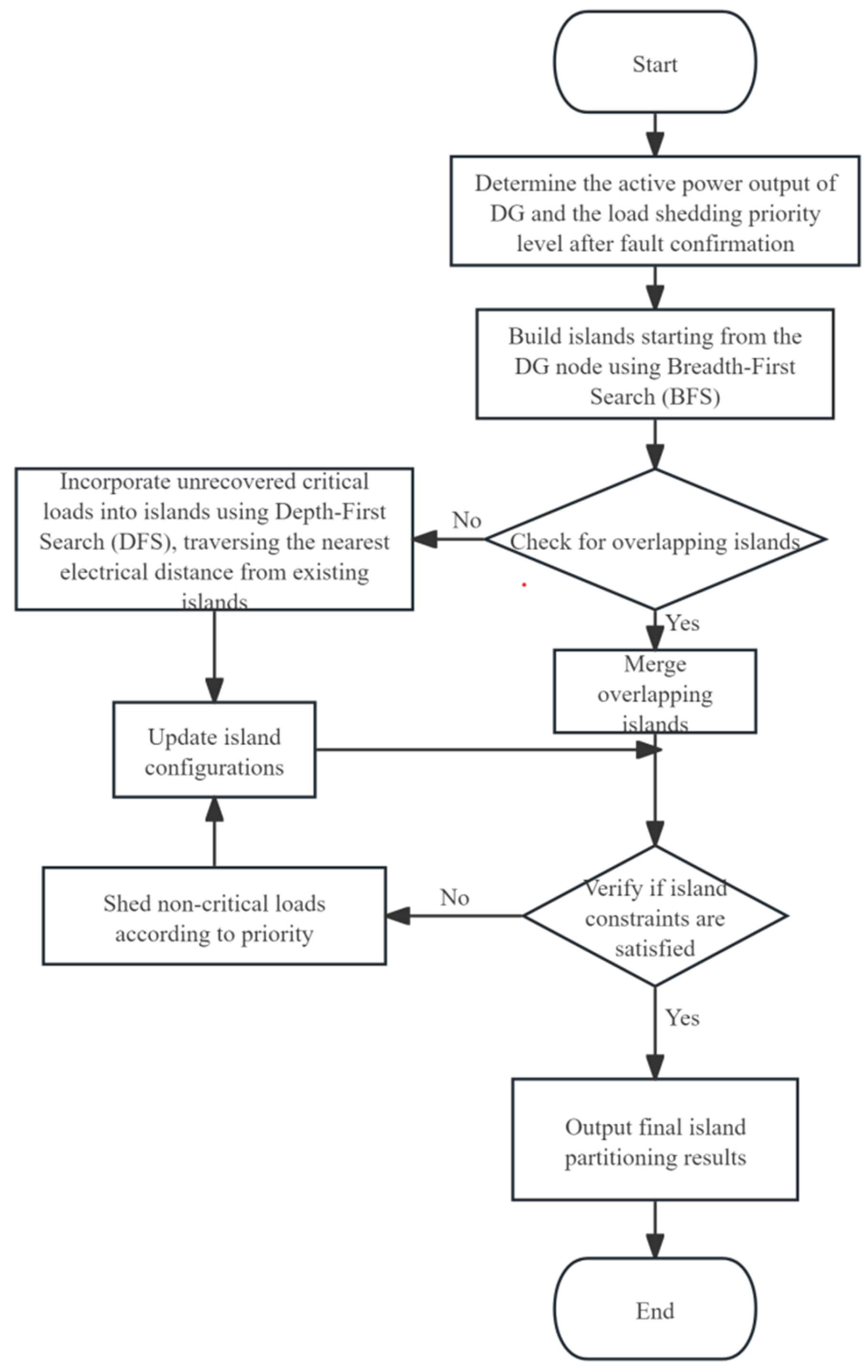

5.3. Steps for Island Partitioning

6. “Source-Storage” Resource Coordination Support Model

6.1. The Objective Function

6.2. The Constraints

6.3. The Solving Method and Steps

7. Simulation and Result Analysis

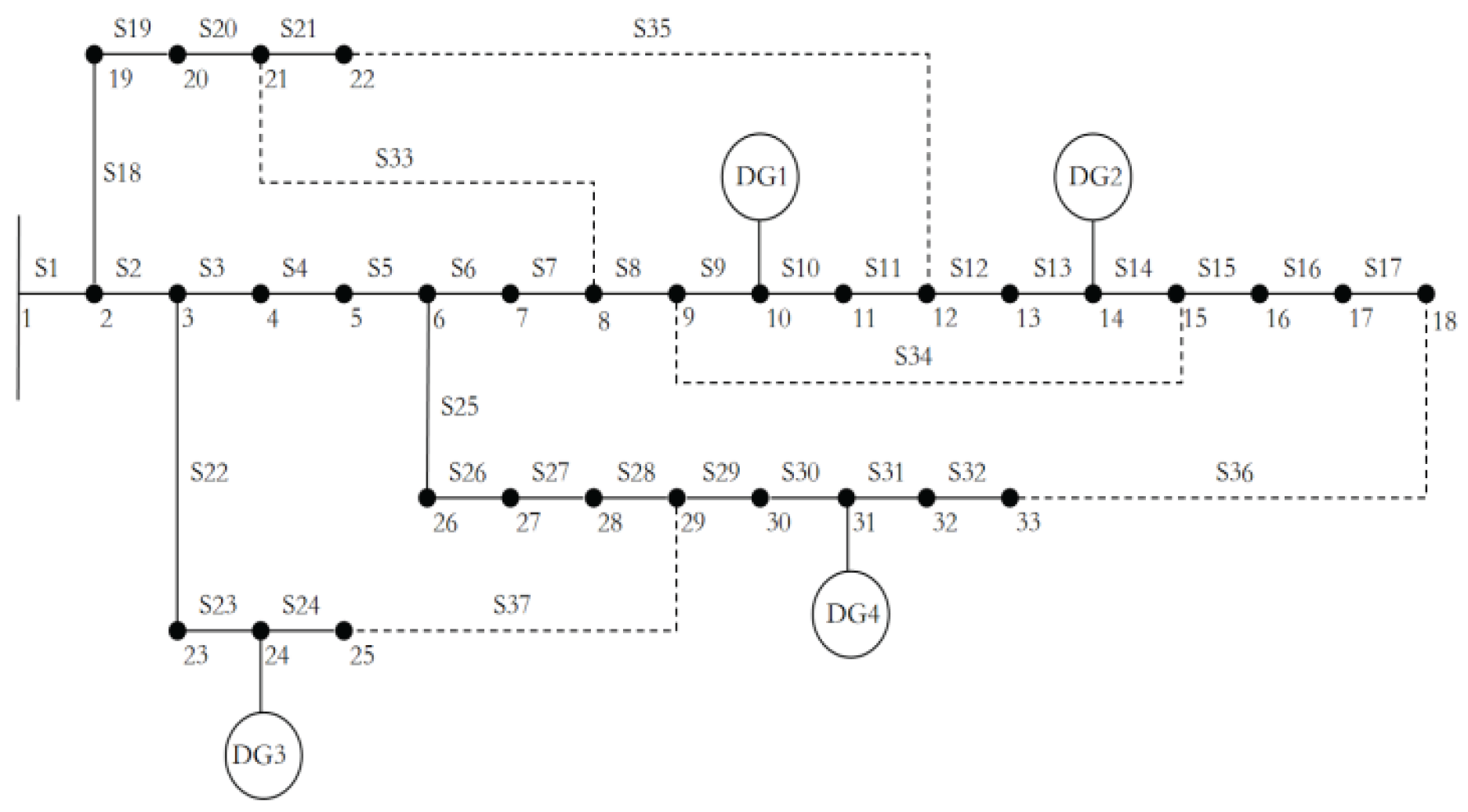

7.1. Data Sources and Parameter Settings

7.2. The Case Analysis

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Zou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, J. Aggregator-Network Coordinated Peer-to-Peer Multi-Energy Trading via Adaptive Robust Stochastic Optimization. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, T.; Li, X. Two-stage robust operation of electricity-gas-heat integrated multi-energy microgrids considering heterogeneous uncertainties. Appl. Energy 2024, 371, 123690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Meng, Q.; et al. A cooperative game-based strategy for the optimal operation of ELectricity-thermal-gas synergy in integrated energy systems. J. Sol. Energy 2022, 43, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Kang, C. Challenges and prospects of constructing new power systems with carbon neutral goals. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 2806–2819. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Chen, H. Estimating the impacts of a new power system on electricity prices under dual carbon targets. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 438, 140583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, M.; Ye, L.; Luo, Y.; et al. Inertia estimation method for new energy power systems considering spatiotemporal correlation of frequency response. Power Syst. Autom. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Si, J.; Wu, X.; Guo, Q.; et al. Wind farm group joint shared energy storage two-stage collaborative grid-connection optimization. Power Grid Technol. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, L.; Sun, F.; Hao, Y.; Du, X.; Mei, S. Share or not share, the analysis of energy storage interaction of multiple renewable energy stations based on the evolution game. Renew. Energy 2023, 208, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Meng, J.; Lin, G.; Cai, Y.; Gao, C.; Chen, T.; Xu, H. Applications of shared economy in smart grids: Shared energy storage and transactive energy. Electr. J. 2022, 35, 107128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Chen, Y. Review of shared energy storage business model and pricing mechanism. Power Syst. Autom. 2022, 46, 178–191. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, W.; Zhou, S.; Yang, Y.; Lv, X.; Lv, T.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Application Prospect, Development Status and Key Technologies of Shared Energy Storage toward Renewable Energy Accommodation Scenario in the Context of China. Energies 2023, 16, 731–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yao, X.; Qi, X.; Han, Y. Low-carbon economy configuration strategy of electro-thermal hybrid shared energy storage in multiple multi-energy microgrids considering power to gas and carbon capture system. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.W.; Yang, Y.B.; Cui, S.; Wang, Y.W. Cooperative online schedule of interconnected data center microgrids with shared energy storage. Energy 2023, 285, 129522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Yang, J.; Liu, P. Relaying-Assisted Communications for Demand Response in Smart Grid: Cost Modeling, Game Strategies, and Algorithms. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2020, 38, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Yu, Y.; Yang, B.; Yang, J. Demand-Side Energy Management Considering Price Oscillations for Residential Building Heating and Ventilation Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 4742–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kuang, R.; Li, W.; Cui, K.; Fu, D.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Huang, H.; Yu, M.; Shen, Y. Numerical study on efficiency and robustness of wave energy converter-power take-off system for compressed air energy storage. Renew. Energy 2024, 232, 121080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, Y.; Han, Y.; Chen, W. Seasonal hydrogen energy storage sizing: Two-stage economic-safety optimization for integrated energy systems in northwest China. iScience 2024, 27, 110691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhu, D.; Hu, J.; Zou, X.; Kang, Y.; Guerrero, J.M. Inertial PLL of Grid-connected Converter for Fast Frequency Support. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Tong, X.; Hussain, S.; Luo, F.; Zhou, F.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; Jin, X.; Li, B. Revolutionizing photovoltaic consumption and electric vehicle charging: A novel approach for residentialmdistribution systems. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 2822–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Hu, J.; Qiu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Ghosh, B.K. A Distributed Economic Dispatch Strategy for Power–Water Networks. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2022, 9, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Lan, X. Optimized configuration and operation model and economic analysis of shared energy storage based on master-slave game considering load characteristics of PV communities. J. Energy Storage 2024, 76, 109841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Li, X.; Hao, Y.; Chen, L. Sizing of centralized shared energy storage for resilience microgrids with controllable load: A bi-level optimization approach. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 954833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Peng, K.; Yang, X.; Liu, K. Coordinated design of multi-stakeholder community energy systems and shared energy storage under uncertain supply and demand: A game theoretical approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 100, 105028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z. Dynamic game optimization control for shared energy storage in multiple application scenarios considering energy storage economy. Appl. Energy 2023, 350, 121801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, F.; Zhang, G.; et al. Optimization configuration of energy storage power stations in wind power gathering areas considering cycle life and operational strategies. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2023, 51, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R. Distributed Three-Phase Power Flow for AC/DC Hybrid Networked Microgrids Considering Converter Limiting Constraints. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 1691–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirkhani, M.; Tavoosi, J.; Danyali, S.; Sarvenoee, A.K.; Abdali, A.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Zhang, C. A review on microgrid decentralized energy/voltage control structures and methods. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.Q.; Zhao, L.; Fu, H.L.; Yeatman, E.; Ding, H.; Chen, L.Q. Ocean wave energy harvesting with high energy density and self-powered monitoring system. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Lin, Z.; Li, X.; Shang, C.; Shen, Q. Multi-objective robust optimisation model for MDVRPLS in refined oil distribution. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 6772–6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhu, D.; Hu, J.; Liu, R.; Zou, X.; Kang, Y. Optimized Design of Demagnetization Control for DFIG-Based Wind Turbines to Enhance Transient Stability During Weak Grid Faults. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liao, H.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, X.; Yin, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Lv, G. Optimal capacity planning and operation of shared energy storage system for large-scale photovoltaic integrated 5G base stations. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 147, 108816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Charkhgard, H.; Rigterink, F. A robust biobjective optimization approach for operating a shared energy storage under price uncertainty. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 29, 1627–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinrui, S. Collaborative optimal scheduling of shared energy storage station and building user groups considering demand response and conditional value-at-risk. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 224, 109769. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Qi, X.; Liu, H.; Song, J. Deep belief network based k-means cluster approach for short-term wind power forecasting. Energy 2018, 16, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, Y. Collaborative allocation model and balanced interaction strategy of multi flexible resources in the new power system based on Stackelberg game theory. Renew. Energy 2024, 220, 119714. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Hou, H.; Deng, M.; Si, L.; Wang, X.; Hu, E.; Zhou, R. Stackelberg game theory based model to guide users’ energy use behavior, with the consideration of flexible resources and consumer psychology, for an integrated energy system. Energy 2024, 288, 129806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, U.N.; Uzair, M.; Allauddin, U. An optical-energy model for optimizing the geometrical layout of solar photovoltaic arrays in a constrained field. Renew. Energy 2020, 14, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fang, Z.; Li, F.; et al. Game optimization scheduling of distribution network with multi-microgrid rental shared energy storage. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 6611–6625. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Xie, P.; et al. A two-stage optimization operation strategy for leasing and sharing energy storage in wind farm clusters. Power Grid Technol. 2024, 48, 1146–1165. [Google Scholar]

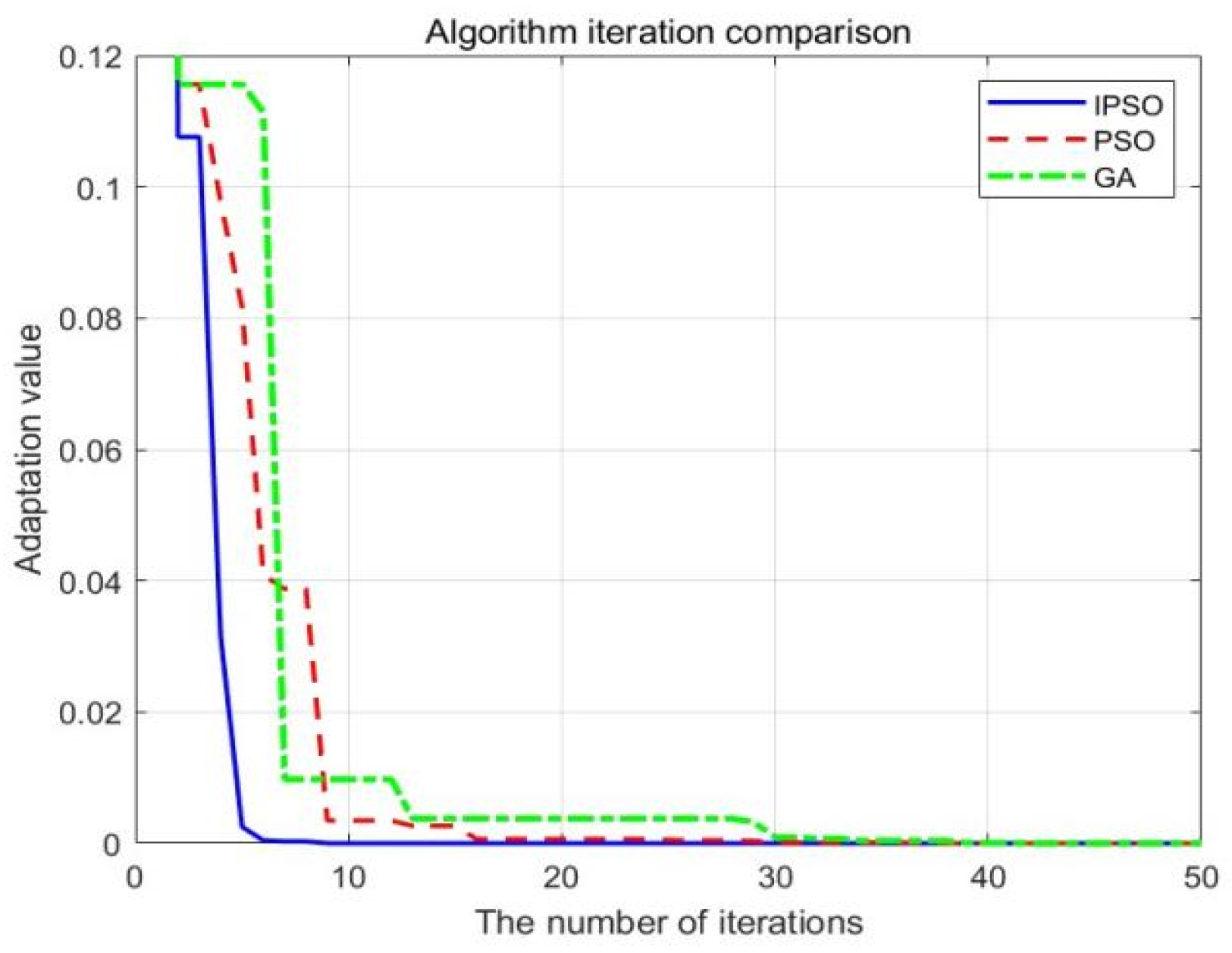

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, F. Collaborative Optimization of Active Distribution Network Fault Reconstruction by Ring-broken Based on Particle Swarm Optimization. Power Information and Communication Technology 2021, 19, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Tang, T.; Chen, R.; Li, Z.; Deng, Q.; Jiang, Y. Research on optimal configuration of distributed generation based on multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm. Journal of Shaoyang University (Natural Science Edition) 2021, 18, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; et al. Distribution Network Fault Recovery Strategy Based on Quantum Firefly Algorithm. Electric Power 2023, 56, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, H.; Yan, Y. Study on fault recovery of distribution network based on improved particle swarm algorithm. Journal of Shaanxi University of Science and Technology 2023, 41, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Ma, T. Fault Recovery Method for Active Distribution Network Based on Hybrid Reinforcement Learning. Proceedings of the Chinese Society for Electrical Engineering - Power System and Automation 2024, 36, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Qiu, S.; Cheng, Z.; Li, Y. A New Method for Active Distribution Network Island Fault Recovery and Reconstruction Considering Distributed Generation. Rural Electrification 2023, 2, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, X.; Pan, C.; Li, Y. A Bi-level Fault Recovery Strategy for Distribution Networks Considering Islandingand Reconfiguration. Jilin Electric Power 2022, 50, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, T.; Yang, H.; Zhao, M.; Jia, H.; Zhang, S. Application of Quantum Particle Swarm Optimization (QPSO)in the restoration and reconstruction of power distribution network. Journal of Chongqing University of Technology (Natural Science) 2022, 36, 200–207. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yan. ; Chen, Jiayue.; Ma, Tianxiang. Fault Recovery Method for Active Distribution Network Based on Hybrid Reinforcement Learning. Power System Automation 2021, 45, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. Research on Fault Location and Self-Healing Strategy of Distribution Network Based on Genetic Algorithm. Power Equipment Management 2024, 20, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Zhao, R.; Guo, W.; et al. Uniform design-based self-healing evaluation for active distribution network. Electric Power Systems Research 2024, 235, 110863–110863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Yao, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Sun Yongwen. Research on distribution network service restoration based on entropy weight and adaptive load coding strategy. Wireless Interconnection Technology 2024, 21, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, X. Research on Self-healing Control Strategy of Microgrid. Hubei Minzu University, 2021.

- Research on Dynamic Reconstruction of Distribution Networks with Distributed Generation. Lanzhou Jiaotong University, Lanzhou, 2024.

| DG number | DG type | Node number | Output power during time period 1/kW | Output power during time period 2/kW |

| DG1 | WTG | 10 | 710 | 500 |

| DG2 | battery | 14 | 730 | 375 |

| DG3 | battery | 24 | 730 | 375 |

| DG4 | PVG | 31 | 430 | 120 |

| Load level | Node number | Load weight |

| Level 1 | 4、10、11、13、14、20、31、32 | 100 |

| Level 2 | 2、5、6、7、12、17、18、19、28、29、30、33 | 10 |

| Level 3 | 1、3、8、9、15、16、21、22、23、24、25、26、27 | 1 |

| Fault period | Strategy | Restore load/kW | Number of switch operation | Power loss/kW |

| Time period 1 12:00-13:00 |

Scheme 1 SchemeScheme 2 |

1768.19 1535.81 |

2 0 |

90.25 110.34 |

| Time period 1 18:00-19:00 |

Scheme 1 SchemeScheme 2 |

1768.57 995 |

2 0 |

108.25 127.12 |

| Strategy | Self-healing recovery rate | Self-healing speed/min | Self-healing omplexity |

| Scheme 1 | 92.43% | 8.3 | 2 |

| Scheme 2 | 85.23% | 14.5 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).