1. Introduction

Sir Isaac Newton(1833)

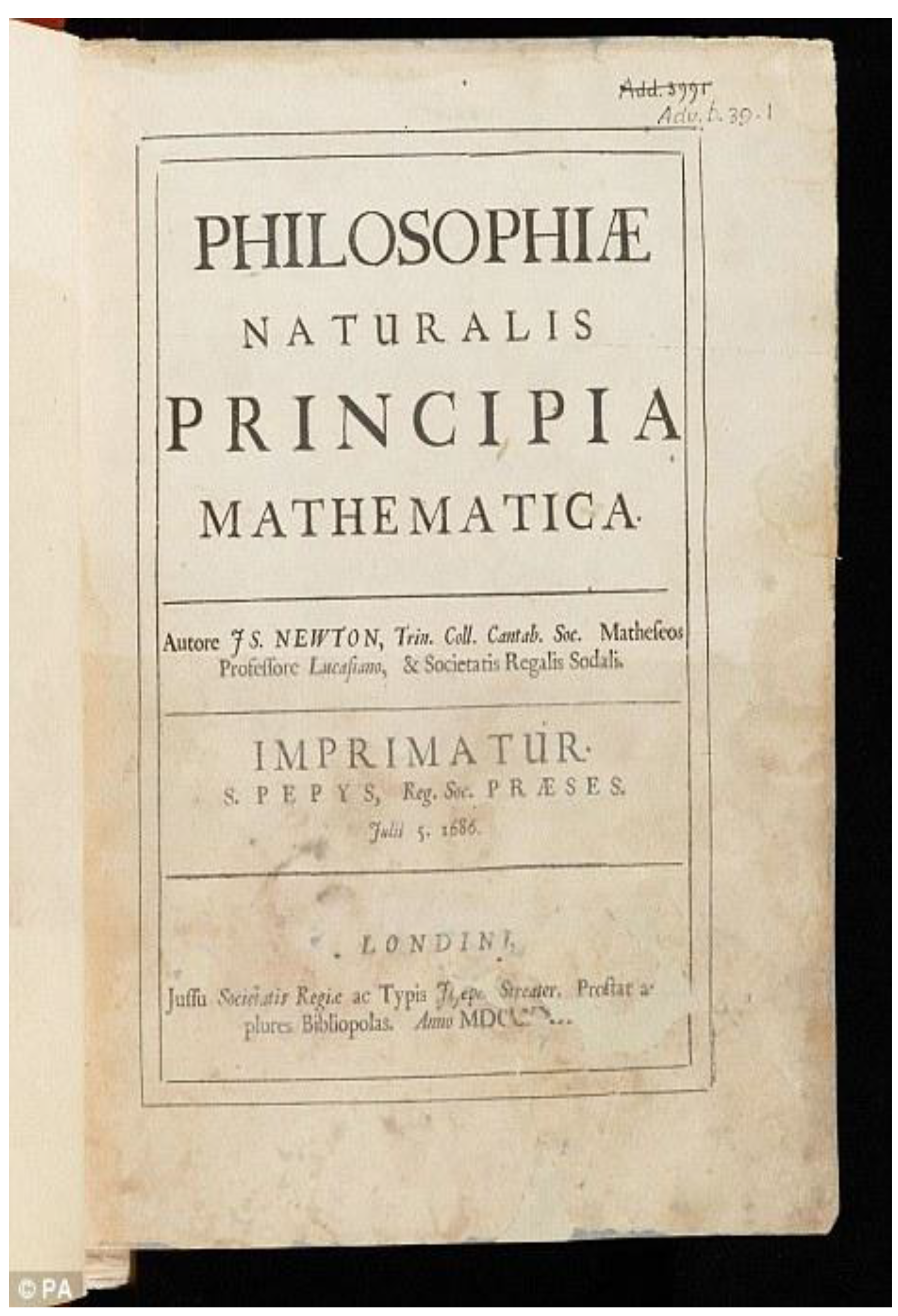

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica is widely recognized as one of the most important books in the history of science, see

Figure 1.

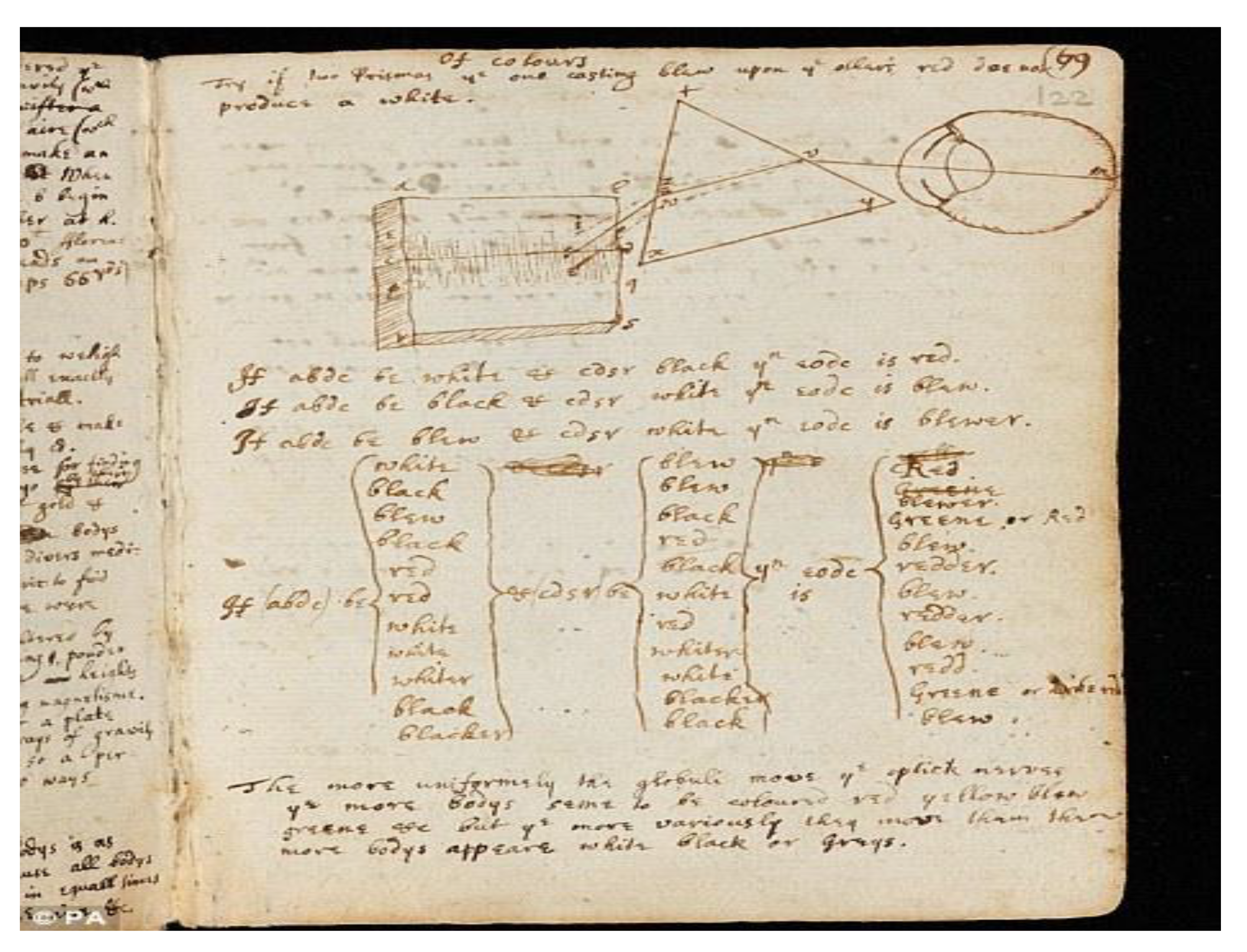

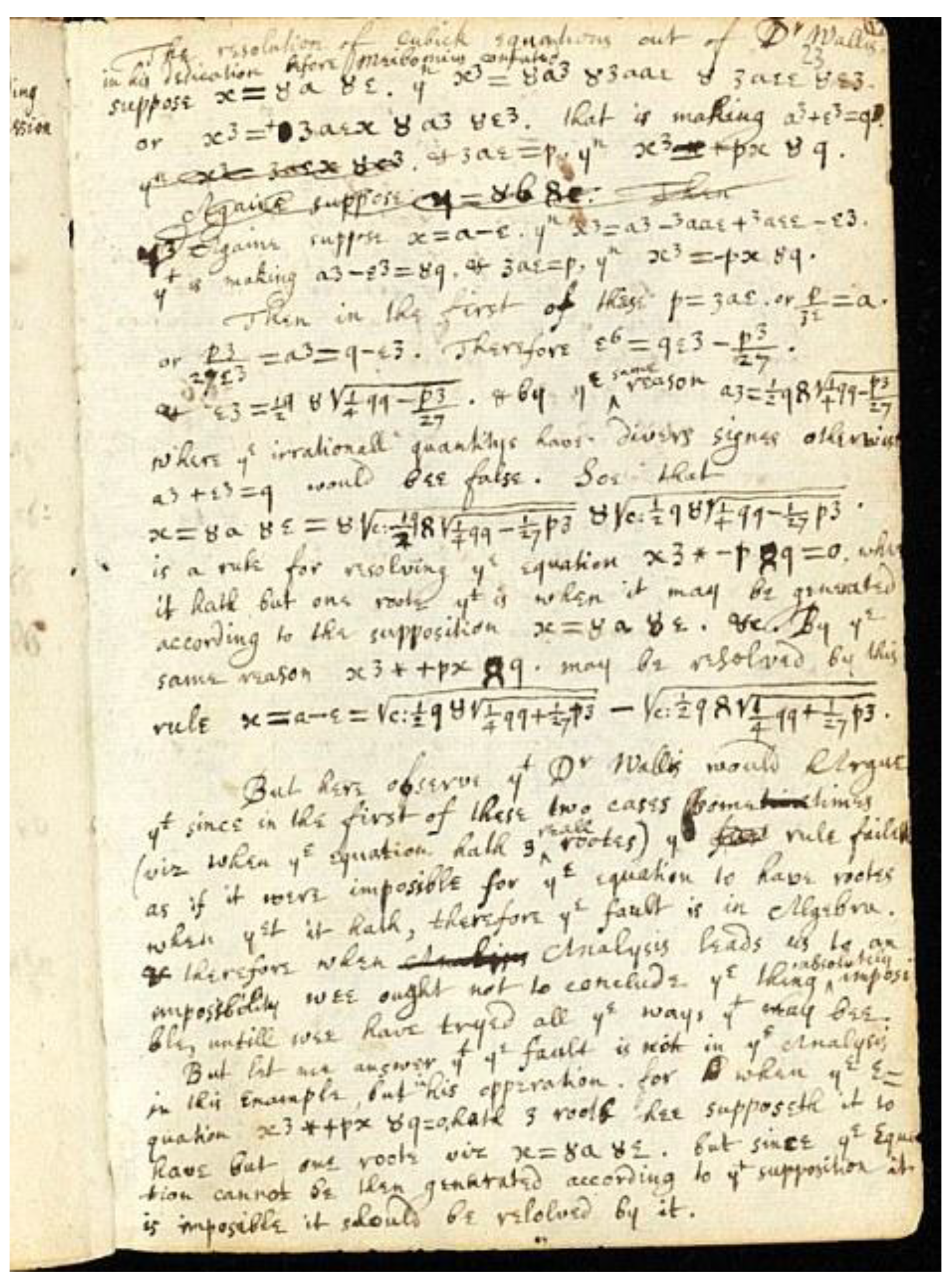

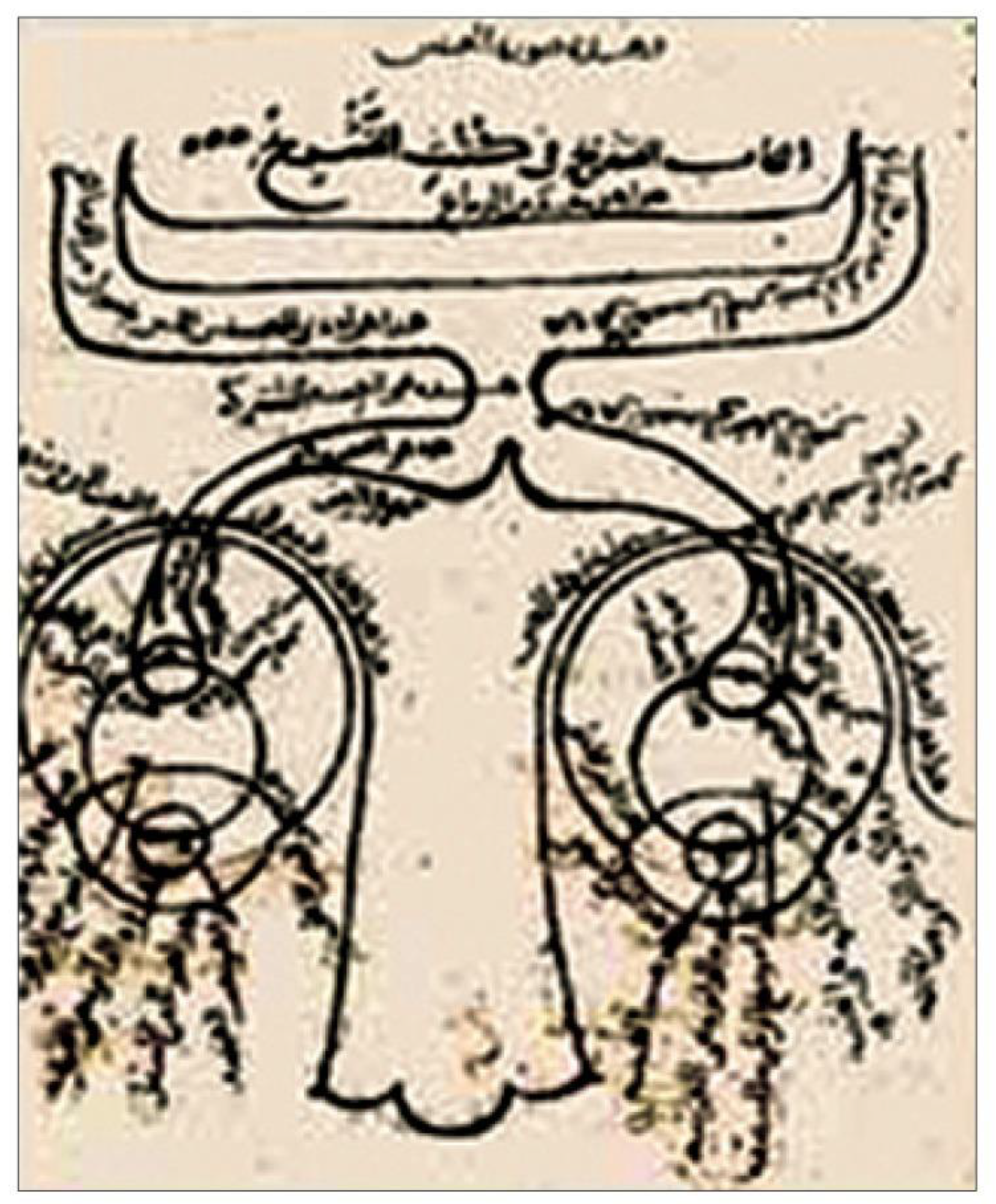

Combining terrestrial and celestial mechanics under a single, logical framework, it presented the mathematical laws of motion and universal gravitation(Mageed, 2025a; Mageed, 2025b). Newton, struck by a descending apple, imagining gravity in a flash of brilliance, is a potent cultural narrative (Shioyama, 2021). Building on the work of his immediate European forebears—Copernicus, Kepler, and, most directly, Galileo Galilei—Newton is at the height of a thought revolution. The accepted historical narrative so posits Newton. This line points to a self-contained European intellectual revival, awakening from the 'dark ages' of medieval scholasticism. A dramatic reinterpretation of this story is, nevertheless, required by a growing body of knowledge in the history of science. It claims that a thriving scientific legacy that flourished in the Arabic-speaking world for more than 700 years shaped—and partially solved—the very questions Newton addressed. Historians like Iqbal (2018) and (Starface, 2020) contend that failing to recognize this era is to misinterpret the very essence of scientific development. This article argues that the fundamental Newtonian physics ideas—especially Newton's First Law, the law of inertia, and Newton's Second Law, the connection between force and acceleration—have their direct predecessors in the criticisms of Aristotelian physics created by Islamic academics. Amazingly, see Figures 2,3& 4(c.f., CUDL, 2025).

Early numerical and conceptual investigations of gravity in the Islamic world, moreover, offered an essential stepping stone toward Newton's universal law. Therefore, revisiting the history of physics and mathematics is not an action of reducing Newton's genius but rather of correcting a more precise, continuous, and multicultural record of scientific advancement. Morgan (2020) suggests that Newton was positioned on the shoulders of "giants" who were more numerous and diverse than commonly believed.

2. The Aristotelian Impasse: A Physics in Need of Correction

The correct assessment of the Aristotelian physics that underwent changes in Islam necessitates familiarity with it. Western and Middle Eastern philosophy was mostly shaped by Aristotle's cosmos and mechanics for almost two thousand years. Aristotle posited a basic split between heavenly and terrestrial motion. Objects had a 'natural motion' on Earth—heavy bodies went toward the centre of the Earth and light bodies (like air) moved away from it. All other motion was "violent motion" need continuous, external mover to be sustained (Eamon, 2020). Explaining projectile motion was difficult with this framework. After departing the bowstring, what sustains an arrow in flight? Aristotle's response was complex: the air displaced by the arrow rushes around to its rear and keeps pushing it forward, theory known as antiperistasis (Marrone, 2020). Later scientists found clearly faulty this justification, which also served as a significant source of disagreement. Aristotle's theory for acceleration in falling bodies, that an item accelerates as it nears its "natural place," lacked a strong causal mechanism. It was a teleological, descriptive physics rather than a mathematical, predictive one. This was the intellectual legacy Islamic thinkers had, against which their most significant breakthroughs were accomplished.

3. The Islamic Crucible: Forging the Tools of a New Mechanics

From the 8th century, the House of Wisdom-based translation movement was active and not passively conserved. Scholars of Islam rigorously interacted with, tested, and attempted to fix the Greek texts they inherited (Gutas, 2023). This critical attitude helped to create ideas that directly confronted the Aristotelian model and set the stage for classical mechanics.

3.1. From Mayl to Impetus: The Birth of Inertia

The most important intellectual step was the creation of a theory of impetus, a straightforward precursor to the contemporary idea of inertia. A major player in this evolution was the Persian polymath Ibn Sina (Avicenna, c. 980–1037). Ibn Sina presented a scathing attack on Aristotle's idea of projectile motion in his Book of Healing.

He maintained it was illogical for the air, which opposes motion, to also generate it. Rather, he suggested that the mover—the hand or bowstring—gives the projectile a characteristic he termed mayl (inclination or impetus), an internal, non-corporeal force sustaining the object's movement (Desaguliers, 1723;Walley, 2018) wrote Ibn Sina:&"Most appropriate hypothesis is the one that the shifted object inherits from the mover an inclination (mayl). "It is this mayl that is the cause of the object's continued motion" (Arabi, 2023).

This was a brilliant concept. An internal characteristic given to the body, rather than an external support, kept motion going. He also claimed this mayl would exist permanently in a vacuum, just being dissipated by outside forces like air. Centuries before Galileo and Newton, this is an almost perfect expression of the theory of inertia.

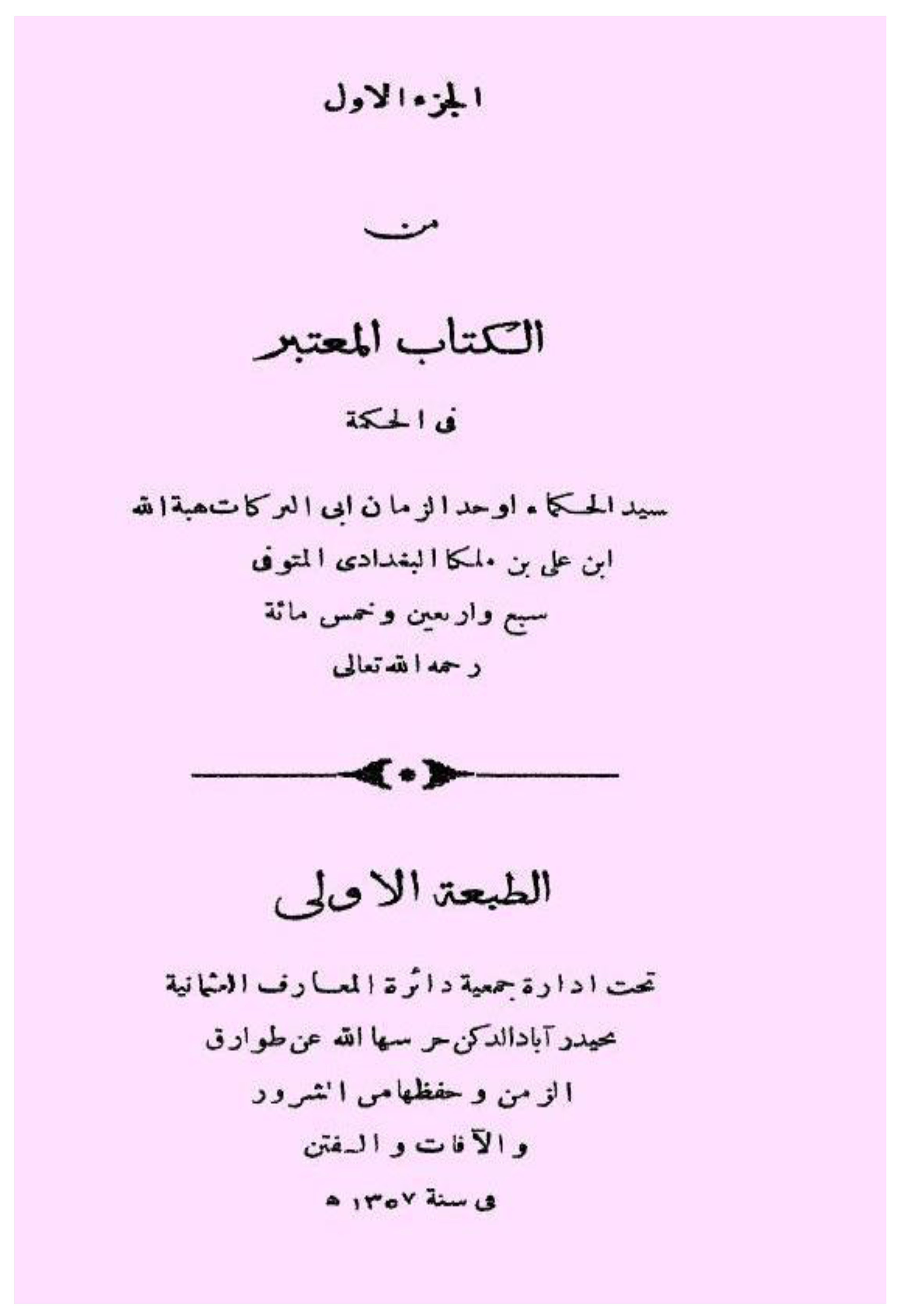

Later academics improved on this hypothesis. Abu'l-Barakat al-Baghdaadi (c. 1080–1165) in his Kitab al-Mu'tabar contended that this gave strength (mayl qasri or violent inclination) is only overcome by resistance, therefore is not self-expending.

More critically, he linked this force to acceleration, speculating that as a falling object drops, it progressively gains mayl from the 'natural heaviness' of the body, therefore accelerating (Marcotte, 2020).

A conceptual building block for Newton's Second Law, this directly connects an innate force with a change in velocity. The work of academics like Ibn Bajjah (Avempace) also helped to disprove Aristotle's erroneous theories on movement (Drake, 2023). Famed as (Awhad Ul Zaman), Al-Baghdadi's concept of acceleration( in his book, Al-Kitāb al-Mu'tabar) was an early predecessor of Isaac Newton's second law of motion, which is commonly expressed as and asserts that force () is equal to mass (m) multiplied by acceleration (a)( Encyclopedia Britannica, 2023).

Al-Baghdadi also claimed that motion is relative)( Encyclopedia Britannica, 2023). Another essential principle of modern physics is the notion that an object's motion is correctly described as a change in its position relative to a stationary object or location, see

Figure 5(c.f., Nizamoglu, 2019)

3.2. Early Conceptions of Gravity and the Quantification of Mechanics

Despite lacking a universal gravitational law, Islamic philosophers moved towards attraction instead of rejecting Aristotle's teleological "natural place. Explicitly asserting that objects fall to Earth not because of their "natural place", but rather "because of the force of attraction of the Earth," the great polymath Al-Biruni (973–1048) stated (Abrahamov, 2022). A crucial conceptual change was this rethinking of gravity as an attracting power instead of an inherent characteristic. Abd al-Rahman al-Khazini in the twelfth century further refined this. For his era, his magnum opus,

The Book of the Balance of Wisdom was a mechanic and hydrostatics study of unsurpassed accuracy. Al-Khazini created very precise balances after careful testing of gravity. A remarkable instinct that foreshadows the inverse-square law (Christie, 2020), he speculated that the gravity of an object varies with its distance from the centre of the Earth. He rightly claimed that air has weight and that an object's weight is less in air than in a vacuum. Though his theory was geocentric, his insistence on exact measurement and his view of gravity as a primary, distance-dependent force were ground-breaking developments.

3.3. The Mathematical and Methodological Framework

Deep developments in mathematics and scientific method underpinned these physical theories. Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850) created a new language for abstract and general problem-solving via algebra's development (Setiawan, 2022). Mathematics beyond its traditional boundaries was pushed by the geometric works of Thabit ibn Qurra and Omar Khayyam, together with the solution of cubic equations (Rashed, 2019).

Most importantly, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, c. 965–1040) first used the modern scientific approach. In his groundbreaking Book of Optics, see

Figure 6(Tbakhi and Amr, 2007) he demanded for a technique starting with a challenge, examined via observation and experiment, and whose results were presented in the language of mathematics and subjected to thorough proof (Raynaud, 2016).

He made it clear that truth is pursued for its own sake and that a scientist must doubt and criticise his own work. From a philosophical activity to an empirical one, this methodical revolution set the intellectual backdrop in which mathematical physics could be born. Raynaud (2016) pointed out, the Optics was more about how to perform science itself than about just eyesight. Newtonian mechanics' eventual evolution depended on this approach.

4. The Channel of Transmission: From Arabic to Latin

These original ideas did not remain limited to the Muslim world. From the 12th century on, a large body of Arabic scientific and philosophical literature was translated into Latin by the busy translation centers in Spain (Toledo) and Sicily, therefore starting an intellectual reawakening in Europe (Bakalla, 2023). Standard university textbooks were the writings of Ibn Sina, Ibn al-Haytham, and others. The theory of impetus provides the clearest line of transmission. Often credited in Eurocentric histories as the originator of impetus theory, 14th-century Parisian philosopher Jean Buridan straight embraced and expanded Ibn Sina's concepts. The connection between Buridan's formulation and Ibn Sina's is so clear (Pascucci, 2024 ; Sinclair, 1923). Buridan's motivation is theoretically equivalent to Ibn Sina's mayl. He used it to explain projectile motion and, crucially, the eternal motion of the Celestial Spheres, arguing that God had imparted an initial impetus to them at creation which, in the absence of resistance, would last forever (Dear, 2018). Buridan's student, Nicole Oresme, went even further, using graphical methods to represent the relationship between time and speed for a uniformly accelerating body—a direct ancestor of the mathematical formalisms used by Galileo (Sissa, 2021). Hence, the knowledge chain is evident: Ibn Sina and al-Baghdaadi start the Aristotle criticism; it travels to Europe and is absorbed by Buridan and Oresme; their ideas spread for two centuries and provide the intellectual context for the work of Galileo Galilei, who mathematically formalised the inertia and acceleration principles (Drake, 2003).

5. Galileo and Newton: The Final Synthesis

This new historical view does not undermine the accomplishments of Newton or Galileo. Galileo's genius was in his methodical use of experiment (e. g. , inclined planes) and mathematics to clearly depict his results, such as his law of falling bodies (). He really fixed inertia as the basic tenet of a fresh physics. Newton brought together an astounding range and might. Taking the notion of inertia, improved by Galileo from its impetus beginnings, he made it universal as his First Law. Giving force, mass, and acceleration their final, elegant mathematical form—F=ma (Second Law). Through his one, universal law of gravitation (Gleick, 2025), he linked Kepler's work on planetary motion with Galileo's terrestrial mechanics. Calculus (or fluxions) gave him the mathematical instrument strong enough to manage the ongoing change innate in his system (Sharma, 2021). Newton's brilliance lay in mathematical formulation, universalisation, and synthesis. Still, his creations were not inertia, force acting as a source of acceleration, and gravity as a key attractive force—the raw conceptual elements he was dealing with. They were the result of centuries of discussion, sophistication, and exploration, in which Islamic intellectuals were highly influential and leading. Newton was likely referring to Descartes, Galileo, and Kepler when he famously said, "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants" (Long, 2022). The historical record reveals the base of that pyramid of giants was constructed in Córdoba, Cairo, and Baghdad.

5.1. A Final Synthesis? Re-evaluating the Bridge from Galileo to Newton

The classic narrative of the Scientific Revolution portrays Isaac Newton's work as the "final synthesis," the culmination of a century of scientific advancement pioneered by innovators such as Galileo Galilei. Newton, who was born the year Galileo died, is frequently regarded as having built immediately on the foundations left by his predecessor. Newton appears to have raised Galileo's terrestrial physics—his studies of falling bodies and projectile motion—and his theory of inertia into a universal framework, describing both earthly and celestial mechanics using a single set of principles. Newton's laws of motion and universal gravitation, according to Monteiro (2022), are the logical extension and mathematical formalisation of Galileo's pioneering, but incomplete, ideas.

However, this "synthesis" isn't as simple as it seems. Historians and philosophers of science have criticised this unified narrative as oversimplifying a more challenging intellectual leap. For example, Galileo's definition of inertia differed from Newton's; Galileo's was a terrestrial, perhaps circular property, whereas Newton's was global, rectilinear (Finocchiaro and Finocchiaro, 2021). According to the argument, Newton did more than just complete Galileo's work; he radically reimagined it. Scholars such as John Worrall suggest that such transitions in science are frequently more revolutionary than cumulative, with large conceptual splits rather than smooth integration (Agostini et al., 2021).

Furthermore, evidence of Newton's direct contact with Galileo's complete writings is less broad than the synthesis narrative suggests, implying a more indirect and transformative influence. While Galileo was a giant, Newton did more than just stand on his shoulders; he created a new edifice of mind (Medawar, 2021).

Conclusion: Rewriting History as an Act of Restoration

Thus, were the laws of mechanics created by "Newtonian" or "Arabic" inventions? The query sets up a false dichotomy. They are not an "Arabic invention" in the sense that one can locate the Principia hinted at in a tenth-century manuscript. Newton's crowning mathematical synthesis and universalization were utterly original. But to refer to them merely as "Newtonian" is to perpetuate a Eurocentric myth that forgets the profound roots of his ideas. Central accomplishments of the Islamic Golden Age were the fundamental criticism of the physics Newton supplanted and the evolution of the main ideas he would later formalise. The immediate parent of inertia is the concept of impetus, conceived by Ibn Sina. Al-Baghdaadi looked at the relationship between force and acceleration. Al-Biruni and al-Khazini postulated that gravity acts as an appealing force. Ibn al-Haytham supported the empirical, mathematical approach this field demanded. Rather than being lost and found, these concepts were immediately sent into the core of mediaeval Europe and served as the foundation for the following phase of scientific growth. Hence, "re-writing the genuine history of mathematics" and mechanics is not about replacing Newton but about situating him inside a richer, more precise, and more sincere worldwide scientific context. It means recognizing that scientific advancement is a cross-cultural cumulate relay rather than a series of separate sprints. Newton finished a revolution that started not in the 16th century but in the 9th, not in Pisa but in Baghdad.

References

- Abrahamov, B. (2022). Islamic theology: traditionalism and rationalism. In Islamic Theology. Edinburgh University Press.

- Agostini, C. D. S., Silveira, I. P. D., & Polla, C. C. (2021). Scientific Evolution of Philosophical Concepts of the Origins of Universe and Life. Revista Archai, (31), e03116.

- Arabi, I. (2023). Les illuminations de la Mecque (pp. 45-58). Éditions i.

- Bakalla, M. H. (2023). Arabic culture: through its language and literature. Taylor & Francis.

- Cambridge Digital Library (CUDL).(2025). Online available at: http://cudl.lib.cam.ac.

- Christie, J. R. (2020). The development of the historiography of science. In Companion to the history of modern science (pp. 5-22). Routledge.

- Dear, P. (2018). Revolutionizing the sciences: European knowledge in transition, 1500-1700. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Desaguliers, J. T. (1723). II. Animadversions upon some experiments relating to the force of moving bodies; with two new experiments on the same subject. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 32(376), 285-290.

- Drake, S. (2003). Galileo at work: His scientific biography. Courier Corporation.

- Drake, S. (2023). Galileo. In Cosmology (pp. 235-238). CRC Press.

- Eamon, W. (2020). Science and the secrets of nature: Books of secrets in medieval and early modern culture.

- Finocchiaro, M. A., & Finocchiaro, M. A. (2021). Koyré’s Études galiléennes: Critical Reasoning vs. A Priori Rationalism. Science, Method, and Argument in Galileo: Philosophical, Historical, and Historiographical Essays, 369-388.

- Gleick, J. (2025). Isaac Newton: Un destin fabuleux. Dunod.

- Gutas, D. (2023). Hellenic Philosophy, Arabic and Syriac reception of. In Oxford Classical Dictionary.

- Encyclopedia Britannica. (2023, June 8). Abu’l-Barakat al-Baghdadi. Online at:.

- Available online: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abul-Barakat-al-Baghdadi.

- Iqbal, M. (2018). Islam and science. Routledge.

- Kalin, I. (2003). Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Ábbasid Society (Second–Fourth/Eighth–Tenth Centuries).

- Long, D. P. (2022). John Henry Newman, Doctrinal Development, and the Canonical Status of the Theologian in the Church. The Catholic University of America.

- Medawar, P. B. (2021). The art of the soluble. Routledge.

- Mageed, I. A. (2025a). Does Infinity Exist? Crossroads Between Mathematics, Physics, and Philosophy. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025b). The Islamization of Mathematics: A Philosophical and Pedagogical Inquiry. MDPI Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Marcotte, R. D. (2020). Abū L-Barakāt al-Baġdādī. In Encyclopedia of Medieval Philosophy: Philosophy between 500 and 1500 (pp. 31-38). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Marrone, S. (2022). The Light of Thy Countenance: Science and Knowledge of God in the Thirteenth Century: Volume Two (Vol. 98). Brill.

- Monteiro, I. (2022). On Hooke’s Rule of Nature. History of science and technology, 12(2), 249-261.

- Morgan, D. L. (2022). Robert Merton and the history of focus groups: Standing on the shoulders of a giant?. The American Sociologist, 53(3), 364-373.

- Nizamoglu, C. (2019, October 18). Abu ‘l-Barakat al-Baghdadi: Outline of a non-aristotelian natural philosophy. Muslim Heritage.

- Available online: https://muslimheritage.com/abu-l-barakat-al-baghdadi-aristotelian-philosophy/.

- Newton, I. (1833). Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (Vol. 1). G. Brookman.

- Pascucci, A. (2024). Probability Theory I.

- Rashed, R. (2019). Encyclopedia of the history of Arabic science. Routledge.

- Raynaud, D. (2016). Critical Edition of Ibn Al-Haytham's On the Shape of the Eclipse. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Setiawan, A. R. (2022). Six Rhetoric Quadratic: the Six Types of Quadratic Equations Presented by Abū Ja’far Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī in al-Kitāb al-Mukhtaṣor fī Ḥisāb al-Jabr wa al-Muqōbala.

- Sharma, P. (2021). THE MIND: A WAY TOWARDS THE PERFECTION OF POWERS OF OUR MIND AND LIFE WITH A 13 YEAR OLD. Preyas Sharma.

- Shioyama, T. (2021). Newton. Faraday. Einstein: From Classical Physics To Modern Physics. World Scientific.

- Sinclair, M. (1923). The Nature of the Evidence. Fortnightly, 113(677), 871-879.

- Sissa, G. (2021). Mille facesse iocos!. Mètis. Anthropologie des mondes grecs anciens, 147-165.

- Straface, A. (2020). Abū Bakr al-Rāzī, Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyāʾ (Rhazes). In Encyclopedia of Medieval Philosophy: Philosophy between 500 and 1500 (pp. 18-22). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Tbakhi, A., & Amr, S. S. (2007). Ibn Al-Haytham: father of modern optics. Annals of Saudi medicine, 27(6), 464-467.

- Walley, S. M. (2018). Aristotle, projectiles and guns. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.00716. arXiv:1804.00716.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).