Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Housing and Diets

2.2. Ingredients and Feed Chemical Analyses

2.3. Plasma Biochemistry

2.4. Sample Collection and Characteristics Measurements

2.5. Assessment of Meat Quality

2.6. Fatty Acid (FA) Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

3.2. Blood Parameters

3.3. Quality of Longissimus Dorsi Muscle (LD)

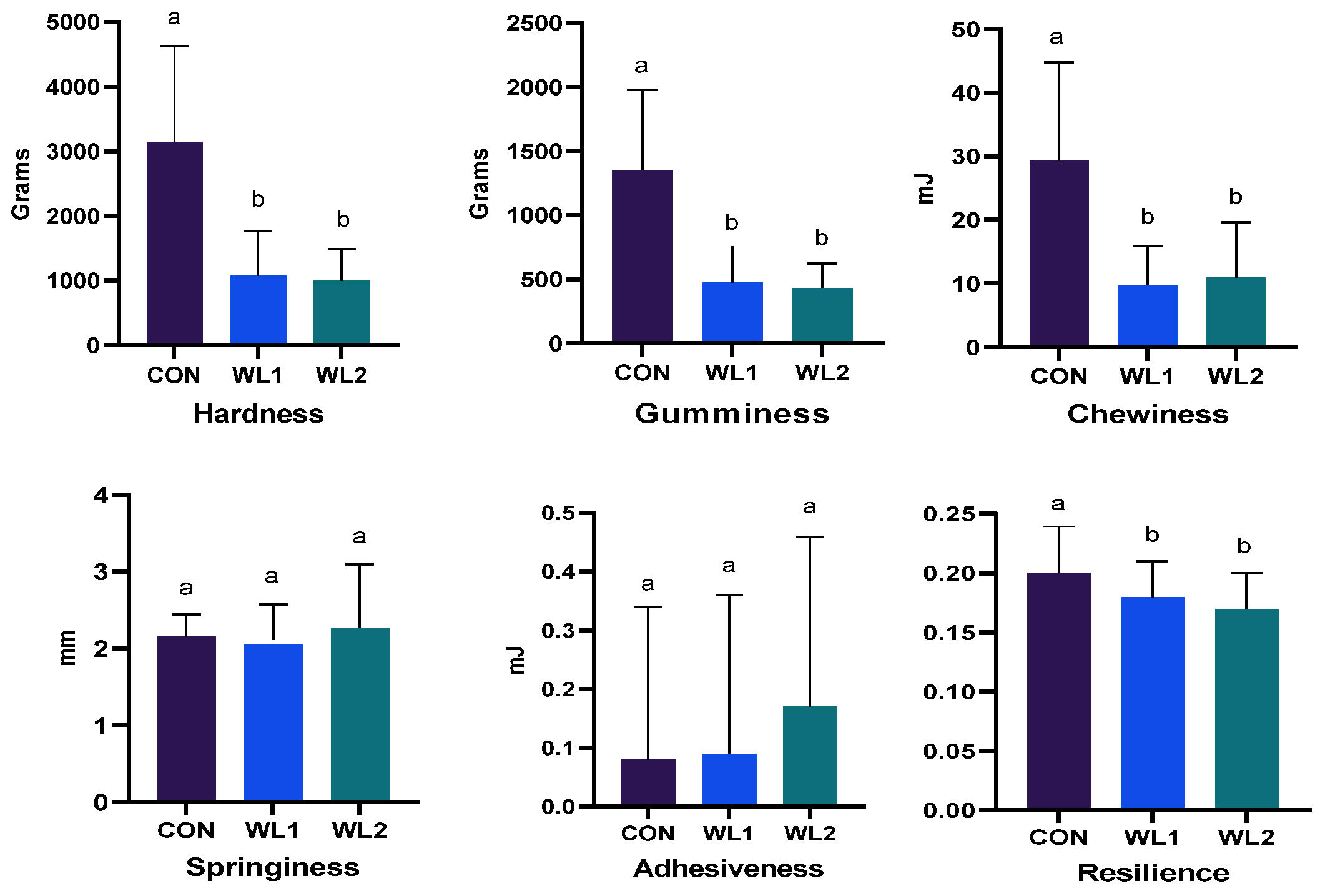

3.4. Fatty Acid Profile, and Lipid Nutritional Indices of LD Muscle

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ciurescu, G.; Vasilachi, A.; Ropotă, M. Effect of dietary cowpea (Vigna unguiculata [L] Walp) and chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) seeds on growth performance, blood parameters and breast meat fatty acids in broiler chickens. Italian J Anim Sci. 2022, 21, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiofalo, B.; Lo Presti, V.; Chiofalo, V.; Gresta, F. The productive traits, fatty acid profile and nutritional indices of three lupin (Lupinus spp.) species cultivated in a Mediterranean environment for the livestock. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 171, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresta, F.; Wink, M.; Prins, U.; Abberton, M.; Capraro, J.; Scarafoni, A.; Hill, G. Lupins in European cropping systems. In Legumes in cropping systems. CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2017, 88–108. ISBN 9781780644981.

- Bolland, M.D.A.; Brennan, R.F. Comparing the phosphorus requirements of wheat, lupine, and canola. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 59, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, P.; Comolli, R.; Ferre, C.; Ghiani, A.; Gentili, R.; Citterio, S. The rotation of white lupin (Lupinus albus L.) with metal-accumulating plant crops: A strategy to increase the benefits of soil phytoremediation. J. Environ. Manag 2014, 145, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Vidal-Valverde, C. Functional lupin seeds (Lupinus albus L. and Lupinus luteus L.) after extraction of α-galactosides. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, S.; Cutrignelli, M.I.; Lo Presti, V.; Tudisco, R.; Chiofalo, V.; Grossi, M.; Infacelli, F.; Chiofalo, B. Characterization and effect of year of harvest on the nutritional properties of three varieties of white lupine (Lupinus albus L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 3127–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresta, F.; Oteri, M.; Scordia, D.; Costale, A.; Armone, R.; Meineri, G.; Chiofalo, B. White lupin (Lupinus albus L.), an alternative legume for animal feeding in the Mediterranean area. Agricult. 2023, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschin, G.; D’Agostina, A.; Annicchiarico, P.; Arnoldi, A. The fatty acid composition of the oil from Lupinus albus cv. Luxe affected by environmental and agricultural factors. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2007, 225, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapletal, D.; Suchy, P.; Strakova, E.; Karel, K.; Kubiska, Z.; Machacek, M.; Vopalensky, J.; Sedlakova, K. Quality of lupin seeds of free varieties of white lupin grown in the Czech Republic. In Capraro, J.; Duranti, M., Magni, Ch., Scarafoni, A., Eds.; editors. 14th International Lupin Conference, Book of Proceedings, Milano (Italy): International Lupin Association, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mierlita, D.; Simeanu, D.; Pop, I.M.; Criste, F.; Pop, C.; Simeanu, C.; Lup, F. Chemical composition and nutritional evaluation of the lupine seeds (Lupinus albus L.) from low-alkaloid varieties. Rev. Chim. 2018, 69, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranilla, L.G.; Genovese, M.I.; Lajolo, F.M. Isoflavones and antioxidant capacity of Peruvian and Brazilian lupin cultivars. J Food Compos. Anal. 2009, 22, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siger, A.; Czubinski, J.; Kachlicki, P.; Dwiecki, K.; Lampart-Szczapa, E.; Nogala-Kałucka, M. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content in three lupin species. J Food Compos Anal. 2012, 25, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellal, K.; Mediani, A.; Ismail, I.S.; Tan, C.P.; Abas, F. 1H NMR-based metabolomics and UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS for the investigation of bioactive compounds from Lupinus albus fractions. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.; Karnpanit, W.; Nasar-Abbas, S.M.; Huma, Z.E. , Jayasena, V. Phytochemical composition and bioactivities of lupin: A review. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2015, 50, 2004–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoldi, A.; Boschin, G.; Zanoni, C.; Lammi, C. The health benefits of sweet lupin seed flours and isolated proteins. J. Funct. Foods. 2015, 18, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andor, B.; Danciu, C.; Alexa, E.; Zupko, I.; Hogea, E.; Cioca, A.; Coricovac, D., Pinzaru, I.; Pătrașcu, J.M.; Mioc ,M.; Cristina, R.T.; Soica, C.; Dehelean, C. Germinated and ungerminated seeds extract from two Lupinus species: Biological compounds characterization and in vitro and in vivo evaluations. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2016, 1-9. 7638542. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Ramos, F.; Sanches Silva, A. Lupin (Lupinus albus L.) seeds: balancing the good and the bad and addressing future challenges. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.M.; Riottot, M.; de Abreu, M.C.; Viegas-Crespo, A.M.; Lanca, M.J.; Almeida, J.A.; Freire, J.B.; Bento, O.P. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary blue lupin (Lupinus angustifolius L.) in intact and ileorectal anastomosed pigs. J. Lipid Res. 2005, 46, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viveros, A.; Centeno, C.; Arija, I.; Brenes, A. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary lupin (Lupinus albus var. Multolupa) in chicken diets. Poult. Sci. 2007, 86, 2631–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettl, A.; Lettner, F.; Wetscherek, W. Use of white sweet lupine seed (Lupinus albus var. Amiga) in a diet for pig fattening. Bodenkultur, 1995, 46, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nevel, C.; Seynaeve, M.; Van De Voorde, G.; De Smet, S.; Van Driessche, E.; de Wilde, R. Effects of increasing amounts of Lupinus albus seeds without or with whole egg powder in the diet of growing pigs on performance. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2000, 83, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.L.; Mullan, B.P.; Kim, J.C.; Dunshea, F.R. The effect of Lupinus albus and calcium chloride on growth performance, body composition, plasma biochemistry and meat quality of male pigs immunized against gonadotrophin releasing factor. Animals 2016, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.L.; Mullan, B.P.; Kim, J.C.; Dunshea, F. The effect of Lupinus albus on growth performance, body composition and satiety hormones of male pigs immunized against gonadotrophin releasing factor. Animals 2017, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zralý, Z.; Písaříková, B.; Trčková, M.; Doleža, M.; Thiemel, J.; Simeonovová, J.; Jůzl, M. Replacement of soya in pig diets with white lupine cv. Butan. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 53, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.M. de C.C.; Vicente, A.F. dos R.B. Meat nutritional composition and nutritive role in the human diet. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NRC. National Research Council. The Nutrient Requirements of Swine; Eighth Revised Edition; National Academy Press: Washington, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Regulation (EC) No 152/2009 of 27 January 2009 laying down the methods of sampling and analysis for the official control of feed. OJEU, 2009, 54, 1–130, Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32009R0152. [Google Scholar]

- Ciurescu, G.; Toncea, I; Ropota, M. ; Hăbeanu, M. Seeds composition and their nutrients quality of some pea (Pisum sativum L.) and lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) cultivars. Rom. Agricult. Res. 2018, 35, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Honikel, K.O. Reference methods for the assessment of physical characteristics of meat. Meat Sci. 1998, 49, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurescu, G.; Idriceau, L.; Gheorghe, A.; Ropotă, M.; Drăghici, R. Meat quality in broiler chickens fed on cowpea (Vigna unguiculata [L.] Walp) seeds. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, T.L.V.; Southgate, D.A.T. Coronary heart disease seven dietary factors. Lancet. 1991, 338, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Tang, W.; Diao, H.; Liu, J. Dietary soybean oligosaccharides addition increases growth performance and reduces lipid deposition by altering fecal short-chain fatty acids composition in growing pigs. Animals, 2023, 13, 3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yang, L.; Zhe, L.; Jlali, M.; Zhuo, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhuo, Y.; Jiang, X.; Huang, L.; Wu, F.; Zhang, R.; Xu, S.; Lin, Y.; Che, L.; Feng, B.; Wu, D.; Preynat, A.; Fang, Z. Supplementation of a multi-carbohydrase and phytase complex in diets regardless of nutritional levels, improved nutrients digestibility, growth performance, and bone mineralization of growing–finishing pigs. Animals 2023, 13, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struti, D.I.; Mierlita, D.; Pop, I.M.; Ladosi, D.; Papuc, T. Evaluation of the chemical composition and nutritional quality of dehulled lupin seed meal (Lupinus spp. L.) and its use for monogastrics animal nutrition: a review. Sci. Papers Ser. D, Anim. Sci. 2020, 63, 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.D.; Cheeke, P.R.; Patton, N.M. Evaluation of lupin (Lupinus albus) seed as a feedstuff for swine and rabbits. J. App. Rabbit Res. 1990, 13, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Van Barneveld, R.J. Understanding the nutritional chemistry of lupin (Lupinus spp.) seed to improve livestock production efficiency. Nutr. Res. Rev. 1999, 12, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, R.J.; Dunshea, F.R.; Morrish, L.; Eason, P.J.; van Barneveld, R.J.; Mullan, B.P.; Campbell, R.G. The energy value of Lupinus angustifolius and Lupinus albus for growing pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2000, 83, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunshea, F.R.; Gannon, N.J.; van Barneveld, R.J.; Mullan BP, Campbell, R. G.; King, R.H. Dietary lupins (Lupinus angustifolius and Lupinus albus) can increase digesta retention in the gastrointestinal tract of pigs. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2001, 52, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandini, A.; Morlacchini, M.; Moschini, M.; Fusconi, G.; Masoero, F.; Pivam, G. Raw and extruded pea (Pisum sativum) and lupin (Lupinus albus var. Multitalia) seeds as protein sources in weaned piglets’ diets: Effect on growth rate and blood parameters. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 4, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zralý, Z.; Pisarikova, B.; Trckova, M.; Herzig, I.; Juzl, M.; Simeonovova, J. The effect of white lupine on the performance, health, carcass characteristics and meat quality of market pigs. Veterinarni Medicina, 2007, 52, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, W.; Fiedorowicz-Szatkowska, E. The effect of replacing genetically modified soybean meal with 00-rapeseed meal, faba bean and yellow lupine in grower-finisher diets on nutrient digestibility, nitrogen retention, selected blood biochemical parameters and fattening performance of pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leikus, R.; Triukas, K.; Svirmickas, G.; Juskiene, V. The influence of various leguminous seed diets on carcass and meat quality of fattening pigs. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 49, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gudiño, J.; López-Parra, M.; Hernández-García, F.I.; Barraso, C.; Izquierdo, M.; Lozano, M.J.; Matías, J. Use of Lupinus albus as a local protein source in the production of high-quality iberian pig products. Animals 2024, 14, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A., Tejerina, D., García-Torres, S., González, E., Morcillo, J. F., & Mayoral, A. I. (2021). Effect of animal age at slaughter on the muscle fibres of Longissimus thoracis and meat quality of fresh loin from Iberian× Duroc crossbred pig under two production systems. Animals, 11, 2143.

- Wiseman, J.; Redshaw, M.S.; Jagger, S.; Nute, G.R.; Wood, J.D. Influence of type and dietary rate of inclusion of oil on meat quality of finishing pigs. Anim. Sci. 2000, 70, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebulska, A.; Jankowiak, H.; Weisbauerová, E.; Nevrkla, P. Influence of an increased content of pea and yellow lupin protein in the diet of pigs on meat quality. PHM, 2021, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Composition (%) | Grower Period | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CON | WL1 | WL2 | |

| Corn | 684.5 | 620.9 | 610.8 |

| Rice bran | 20.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Soybean meal, 45.6% CP | 125.0 | 90.0 | 60.0 |

| Sunflower meal, 34% CP | 100.0 | 70.0 | 60.0 |

| White lupin | - | 50.0 | 100.0 |

| Corn gluten meal, 60% CP | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Vegetable oil | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| DL-Methionine, 99% Met | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| L-Lysine HCl, 78% Lys | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 |

| Carbonate calcium | 16.5 | 17.5 | 17.3 |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 10.6 | 7.9 | 8.0 |

| Salt | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Premix Choline, 50% | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Vitamin-mineral premix*, no antibiotic | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Calculated nutritional value (%) | |||

| ME, MJ/kg** | 13.07 | 13.02 | 13.05 |

| Crude protein | 16.87 | 16.83 | 16.85 |

| Lysine | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| Methionine + cystine | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Calcium | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Total Phosphorus | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.65 |

| Analyzed nutritional value (%) | |||

| Dry matter | 89.32 | 89.55 | 89.23 |

| Crude protein | 17.95 | 17.90 | 17.93 |

| Ether extract | 3.90 | 4.15 | 4.30 |

| Crude fibre | 4.94 | 4.96 | 5.22 |

| Crude ash | 6.03 | 5.74 | 5.95 |

| Composition (%) | Finisher Period | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CON | WL1 | WL2 | |

| Corn | 569.9 | 549.6 | 586.3 |

| Wheat | 167.0 | 177.0 | 120.0 |

| Soybean meal, 45.6% CP | 160.0 | 110.0 | 60.0 |

| Sunflower meal, 34% CP | 60.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| White lupin | - | 70.0 | 140.0 |

| DL-Methionine, 99% Met | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| L-Lysine HCl, 78% Lys | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

| Carbonate calcium | 14.4 | 14.2 | 13.9 |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 9.3 | 9.3 | 9.5 |

| Salt | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Premix Choline, 50% | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Vitamin-mineral premix*, no antibiotic | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Calculated nutritional value (%) | |||

| ME, MJ/kg** | 13.00 | 13.00 | 12.98 |

| Crude protein | 15.87 | 15.85 | 15.87 |

| Lysine | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Methionine + cystine | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| Calcium | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Total Phosphorus | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.59 |

| Analysed nutritional value (%) | |||

| Dry matter | 89.33 | 89.27 | 89.05 |

| Crude protein | 15.98 | 15.93 | 15.85 |

| Ether extract | 3.58 | 3.77 | 4.06 |

| Crude fibre | 4.50 | 4.70 | 5.30 |

| Crude ash | 5.20 | 5.41 | 5.46 |

| Item (%) |

Lupinus albus L., Mihai Variety |

|---|---|

| Dry matter | 89.77 |

| Crude protein | 36.19 |

| Ether extract | 8.08 |

| Crude fibre | 14.64 |

| Ash | 3.47 |

| NFE | 26.39 |

| NDF | 22.76 |

| ADF | 15.97 |

| ADL | 3.77 |

| Cellulose | 12.20 |

| Hemicelluloses | 6.79 |

| Calcium | 0.32 |

| Phosphorus | 0.49 |

| Antinutrients | |

| Phytic acid, mg/100 g | 0.64 |

| Free Phosphorous, g/100 g | 0.12 |

| Fatty acids (g FAME/100 g total FAME) | |

| Lauric (C12:0) | 0.09 |

| Myristic (C14:0) | 0.29 |

| Palmitic (C16:0) | 10.52 |

| Stearic (C18:0) | 2.49 |

| Heneicosanoic (C21:0) | 0.74 |

| Total SFA | 14.13 |

| Pentadecanoic (C15:1) | 0.15 |

| Palmitoleic (C16:1) | 0.64 |

| Oleic (C18:1n-9) | 51.74 |

| Total MUFA | 52.53 |

| Linoleic (C18:2n-6) | 18.81 |

| α-linolenic (C18:3n-3) | 11.34 |

| Octadecatetraenoic (C18:3n-3) | 3.11 |

| Eicosadienoic (C18:3n-3) | 0.08 |

| Total PUFA | 33.34 |

| PUFA n-3 | 14.53 |

| Item | Dietary Treatments | SEM | P-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | WL1 | WL2 | |||||

| Grower period (30-60 kg) | |||||||

| IBW, kg | 30.30 | 30.32 | 30.35 | 0.10 | 0.981 | ||

| Final BW, kg | 61.17 | 59.50 | 59.42 | 0.30 | 0.090T | ||

| ADG, kg | 0.882 | 0.834 | 0.831 | 0.05 | 0.065 T | ||

| ADFI, kg | 2.06 | 1.93 | 1.84 | 0.05 | 0.151 | ||

| FCR, kg/kg | 2.34 | 2.30 | 2.22 | 0.09 | 0.747 | ||

| Finisher period (61-110 kg) | |||||||

| Final BW, kg | 106.62a | 99.10b | 94.65c | 1.14 | 0.039 | ||

| ADG, kg/day | 0.947a | 0.825b | 0.734b | 0.05 | 0.0001 | ||

| ADFI, kg | 3.18a | 3.07ab | 2.76b | 0.06 | 0.004 | ||

| FCR, kg/kg | 3.36b | 3.72a | 3.76a | 0.07 | 0.025 | ||

| Overall | |||||||

| ADG, kg | 0.920a | 0.829ab | 0.776bc | 0.04 | 0.051 | ||

| ADFI, kg/day | 2.71a | 2.59ab | 2.37b | 0.04 | 0.007 | ||

| FCR, kg/kg | 2.95 | 3.10 | 3.05 | 0.05 | 0.437 | ||

| Carcass yield, % | 72.56 | 71.73 | 71.47 | 0.56 | 0.096 | ||

| Item | Parameters | Dietary Treatments | SEM | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | WL1 | WL2 | ||||

|

Energy profile |

GLU, mg/ dL | 110.17 | 109.00 | 112.25 | 0.14 | 0.124 |

| TG, mg/ dL | 59.50 | 56.50 | 55.00 | 2.19 | 0.116 | |

| TCH, mg/ dL | 99.00 | 90.00 | 101.25 | 1.22 | 0.168 | |

| HDL-C, mg/ dL | 59.00 | 61.00 | 63.00 | 1.12 | 0.434 | |

| LDL-C, mg/ dL | 58.87 | 58.57 | 58.54 | 1.10 | 0.352 | |

|

Protein profile |

TP, g/ dL | 4.27 | 4.55 | 4.10 | 0.11 | 0.668 |

| ALB, g/ dL | 2.30 | 2.50 | 2.73 | 0.04 | 0.168 | |

| BIL, mg/ dL | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.239 | |

| BUN, mg/ dL | 11.50 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 0.32 | 0.421 | |

| UA, mg/ dL | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.232 | |

| CRE, mg/ dL | 1.27 | 1.25 | 1.45 | 0.05 | 0.158 | |

|

Mineral profile |

Ca, mg/ dL | 11.23 | 11.25 | 11.58 | 0.24 | 0.121 |

| Mg, mg/ dL | 1.77 | 1.80 | 1.75 | 0.07 | 0.178 | |

| IP, mg/ dL | 8.27 | 7.30 | 7.38 | 0.16 | 0.230 | |

|

Enzymatic profile |

ALT, U/L | 47.50 | 45.00 | 44.50 | 2.10 | 0.322 |

| AST, U/L | 31.83 | 29.50 | 28.95 | 2.22 | 0.449 | |

| ALP, U/L | 133.51 | 130.12 | 129.10 | 1.55 | 0.202 | |

| CK, UI/L | 325.00 | 328.00 | 326.01 | 2.20 | 0.429 | |

| LDH, UI/L | 520.10 | 527.33 | 524.00 | 3.05 | 0.115 | |

| GGT, UI/L | 39.50 | 40.30 | 38.55 | 1.22 | 0.658 | |

| Parameters | Dietary Treatments | SEM | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | WL1 | WL2 | |||

| Physical traits | |||||

| Color components in the CIE scale: | |||||

| L* | 61.35 | 59.82 | 59.61 | 0.61 | 0.462 |

| a* | 10.48c | 12.29b | 13.23a | 0.20 | 0.0001 |

| b* | 7.67 | 7.42 | 7.53 | 0.13 | 0.563 |

| pH24 | 5.64 | 5.65 | 5.62 | 0.07 | 0.659 |

| Drip loss, % | 3.96 | 3.87 | 3.84 | 0.12 | 0.092 |

| Chemical composition | |||||

| Moisture, % | 74.52 | 72.93 | 73.03 | 0.12 | 0.0001 |

| Protein, % | 22.03 | 22.33 | 21.79 | 0.14 | 0.292 |

| Fat, % | 2.60 | 3.99 | 4.66 | 0.19 | 0.001 |

| Collagen, % | 0.83c | 0.92b | 0.97a | 0.01 | 0.0001 |

| Fatty Acid (g/100 g Total FAME) |

Formula | Dietary Treatments | SEM | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | WL1 | WL2 | ||||

| Myristic | C14:0 | 1.32a | 1.00b | 1.44c | 0.07 | 0.008 |

| Palmitic | C16:0 | 23.72 | 23.41 | 24.72 | 0.27 | 0.103 |

| Palmitoleic | C16:1 | 2.81 | 3.26 | 3.24 | 0.10 | 0.131 |

| Stearic | C18:0 | 13.24 | 12.31 | 12.66 | 0.22 | 0.222 |

| Oleic | C18:1n-9 | 41.76a | 41.12b | 38.71c | 0.52 | 0.008 |

| Linoleic | C18:2n-6 | 9.98 | 10.73 | 11.12 | 0.25 | 0.170 |

| Linoleic conjugate | C18:2 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.627 |

| α-Linolenic | C18:3n-3 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.490 |

| Eicosadienoic | C20:2n-6 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.257 |

| Eicosatetraenoic | C20:4n-6 | 1.66 | 2.01 | 1.67 | 0.13 | 0.507 |

| Eicosapentaenoic | C20:5n-3 | 0.02a | 0.05ab | 0.10c | 0.01 | 0.014 |

| Nervonic | C24:1n-9 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.263 |

| Docosadienoic | C22:2n-6 | 0.06a | 0.06ab | 0.14c | 0.01 | 0.004 |

| Docosatetraenoic | C22:4n-6 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.279 |

| Docosahexaenoic | C22:6n-3 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.287 |

| Other FA | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.150 | |

| SFA | 39.11 | 37.93 | 39.97 | 0.44 | 0.163 | |

| MUFA | 45.58a | 45.68ab | 43.38c | 0.44 | 0.018 | |

| PUFA | 14.41 | 15.74 | 16.03 | 0.42 | 0.278 | |

| PUFA/ SFA ratio | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.401 | |

| n-6 PUFA | 14.16 | 15.49 | 15.76 | 0.42 | 0.277 | |

| n-3 PUFA | 1.56b | 1.71a | 1.76a | 0.08 | 0.045 | |

| n-6/ n-3 PUFA ratio | 9.14 | 9.13 | 9.08 | 0.24 | 0.595 | |

| AI | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.172 | |

| TI | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.001 | 0.196 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).