Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Background

- Source and destination IP addresses indicate where communication begins and ends.

- Source/Destination Ports: This indicates the services or applications utilised.

- Protocol Type: This indicates the specific communication protocols to utilise (such as TCP or UDP).

- Packet/Byte Transfer Statistics: This illustrates the flow of data.

- Duration: The length of time connections last.

- Attack Labels (IsAnomaly) denote whether the traffic is categorised as usual (0) or as an attack (1) [4].

2. Associated Literature

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Acquisition Procedures

3.2. Dataset Compilation

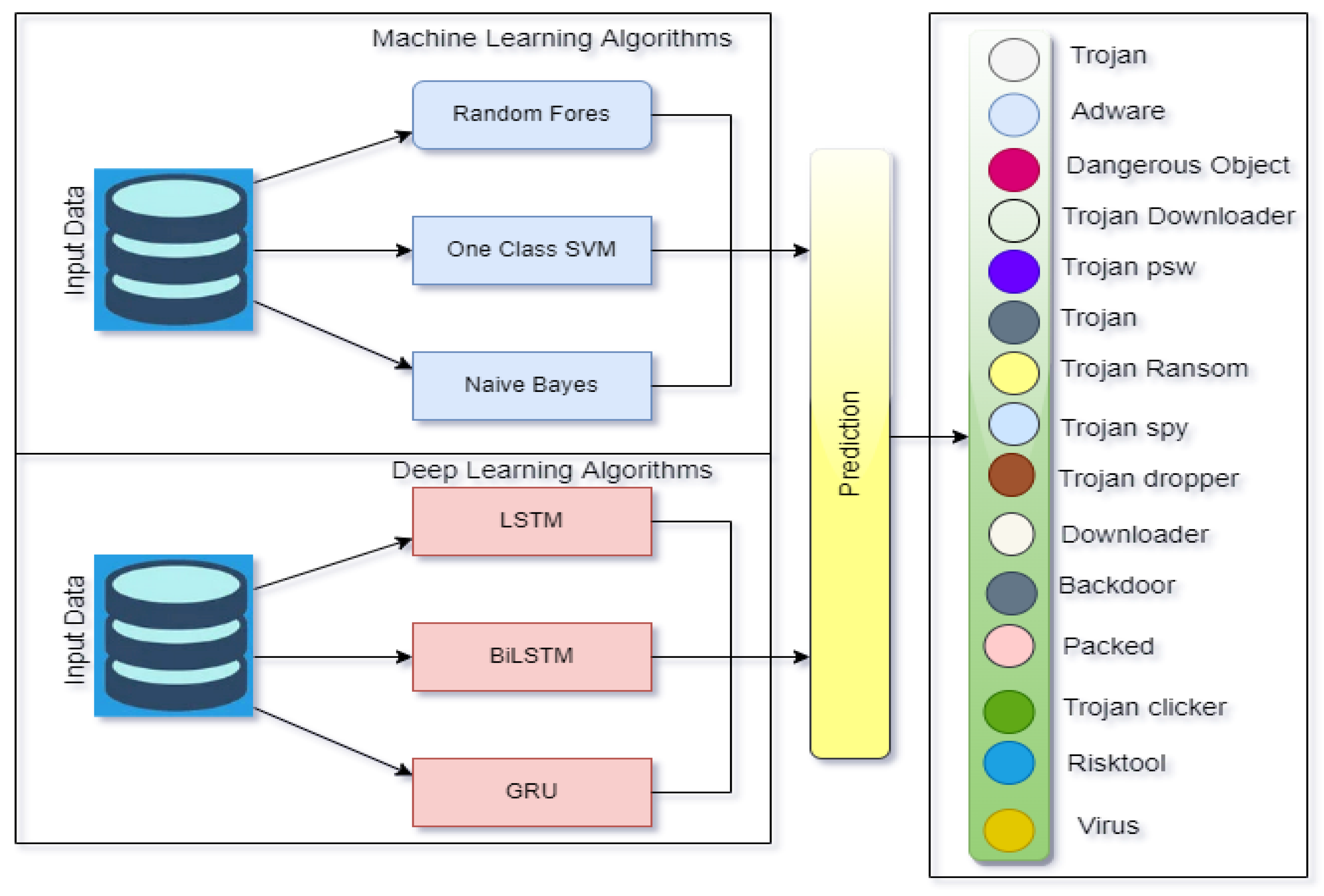

3.3. Executed Algorithms

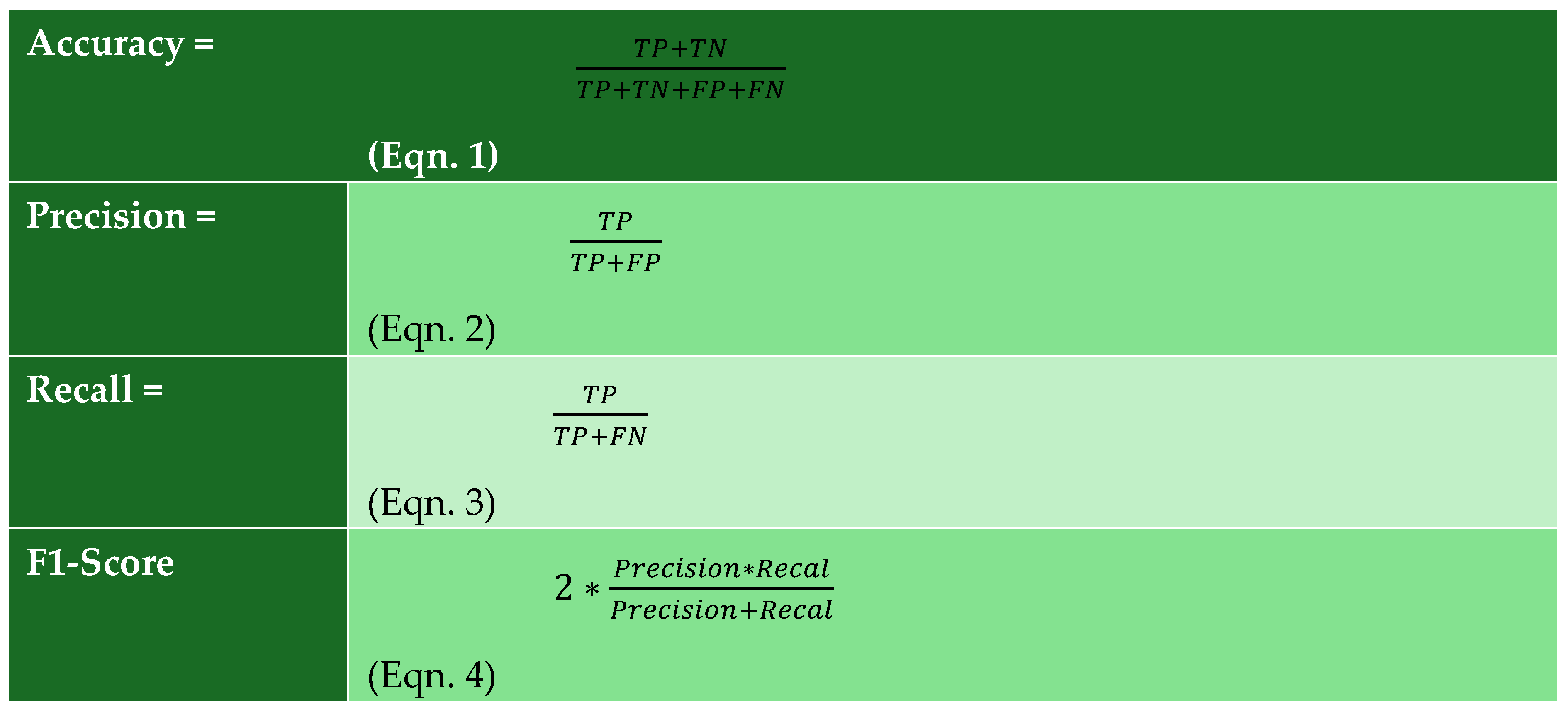

3.4. Assessment Criteria

4. Experimental Configuration

4.1. Characteristics of the Dataset

4.2. Optimisation of Hyperparameters

4.3. Tools for Implementation

5. Results

5.1. Performance Evaluation (Reference)

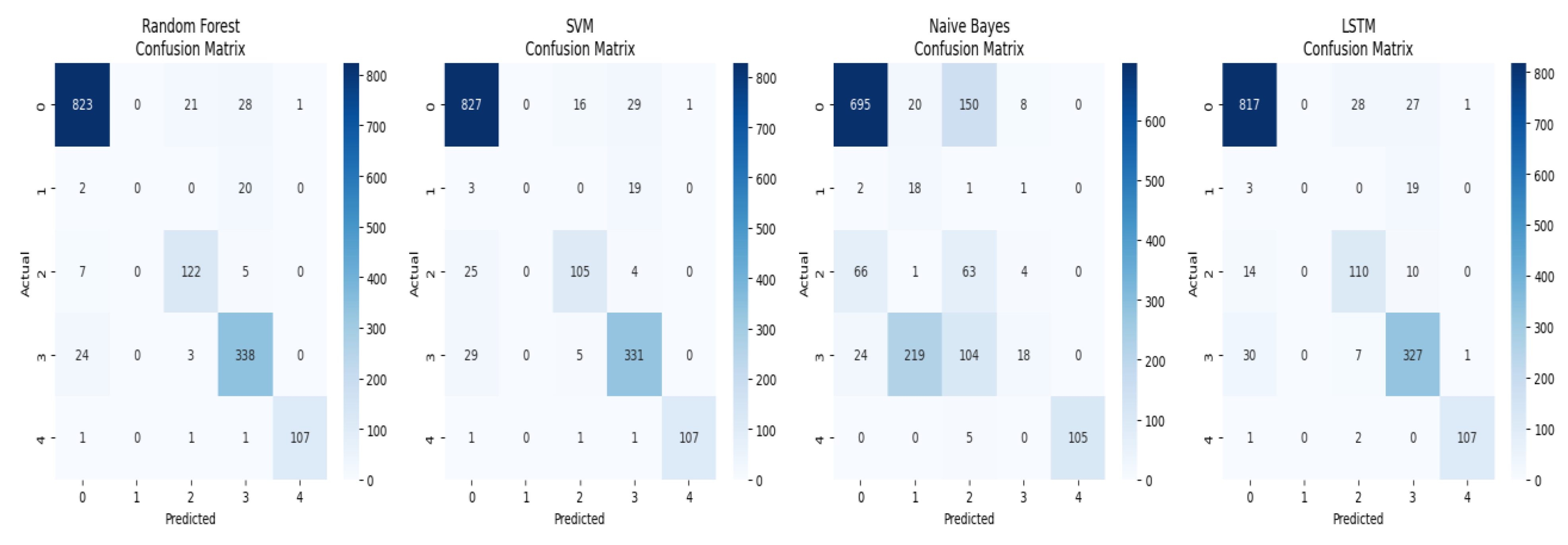

5.2. Analysis of the Confusion Matrix

| True Positive (TP) | False Negative (FN) | False Positive (FP) | True Negative (TN) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 924,000 | 76,000 | 24,000 | 74,000 |

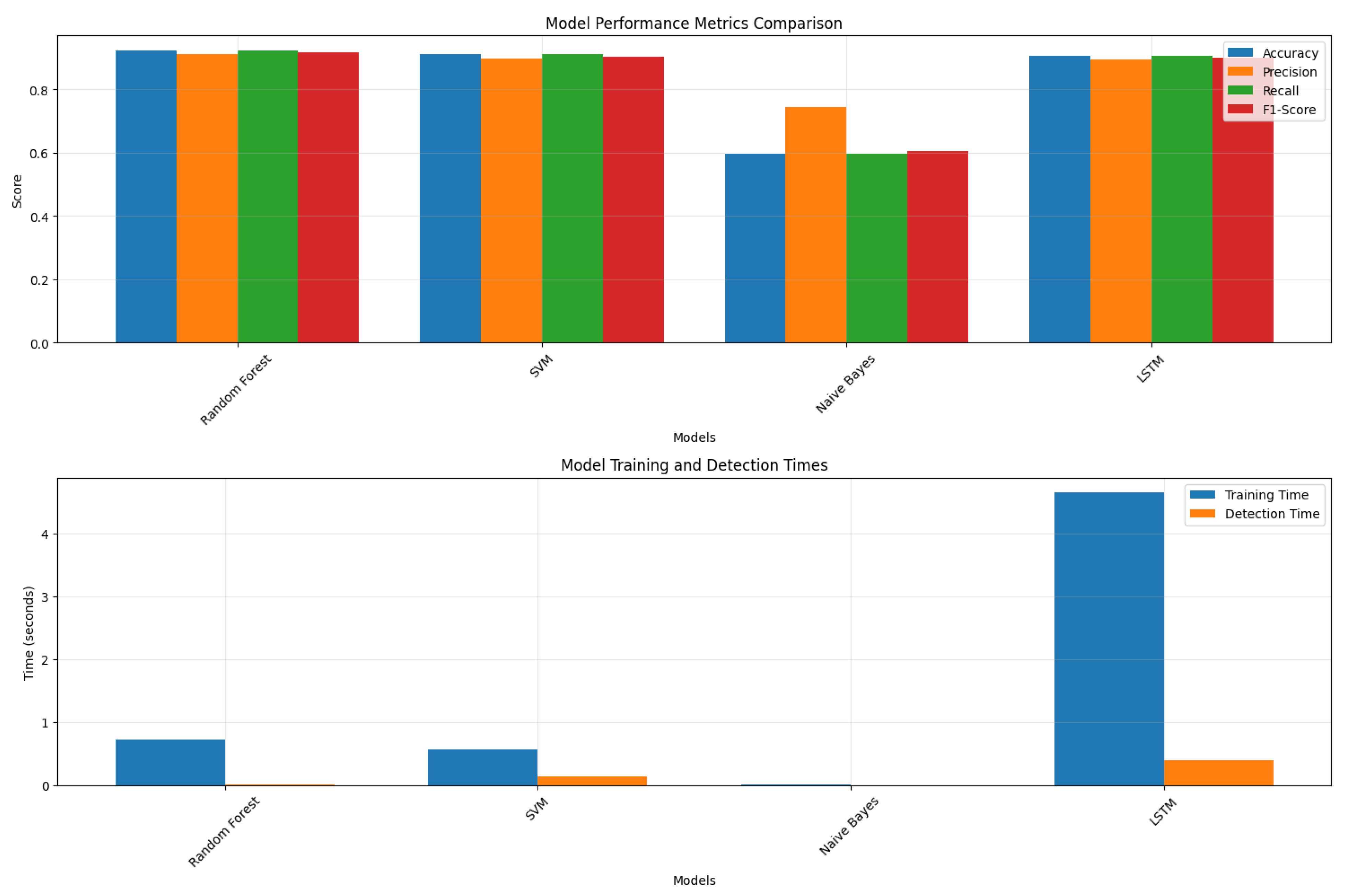

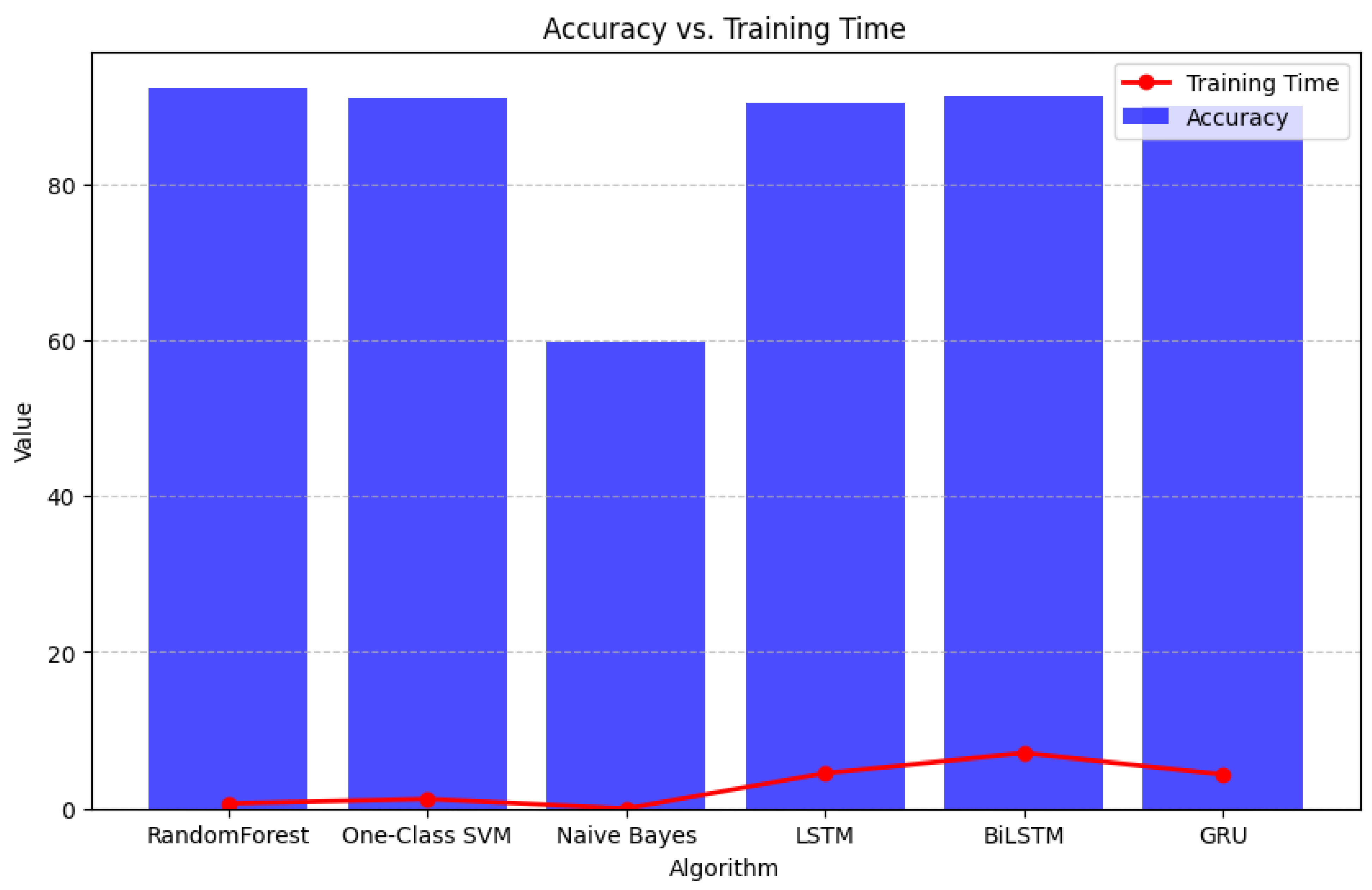

5.3. Computational Efficiency

5.4. Elements of the Visualisation

5.5. Principal Insights and Analysis

5.6. Consequences for Zero-Day Attack Identification

6. Experimental Configuration

6.1. Characteristics of the Dataset

6.2. Optimisation of Hyperparameters

6.3. Tools for Implementation

7. Outcomes

7.1. Comparative Analysis of Performance

7.2. Analysis of the Confusion Matrix

7.3. Confusion Matrix Analysis

7.4. Computational Efficiency

7.5. Graphical Representations

7.6. Examination and Elucidation

8. Discussion

8.1. Implications

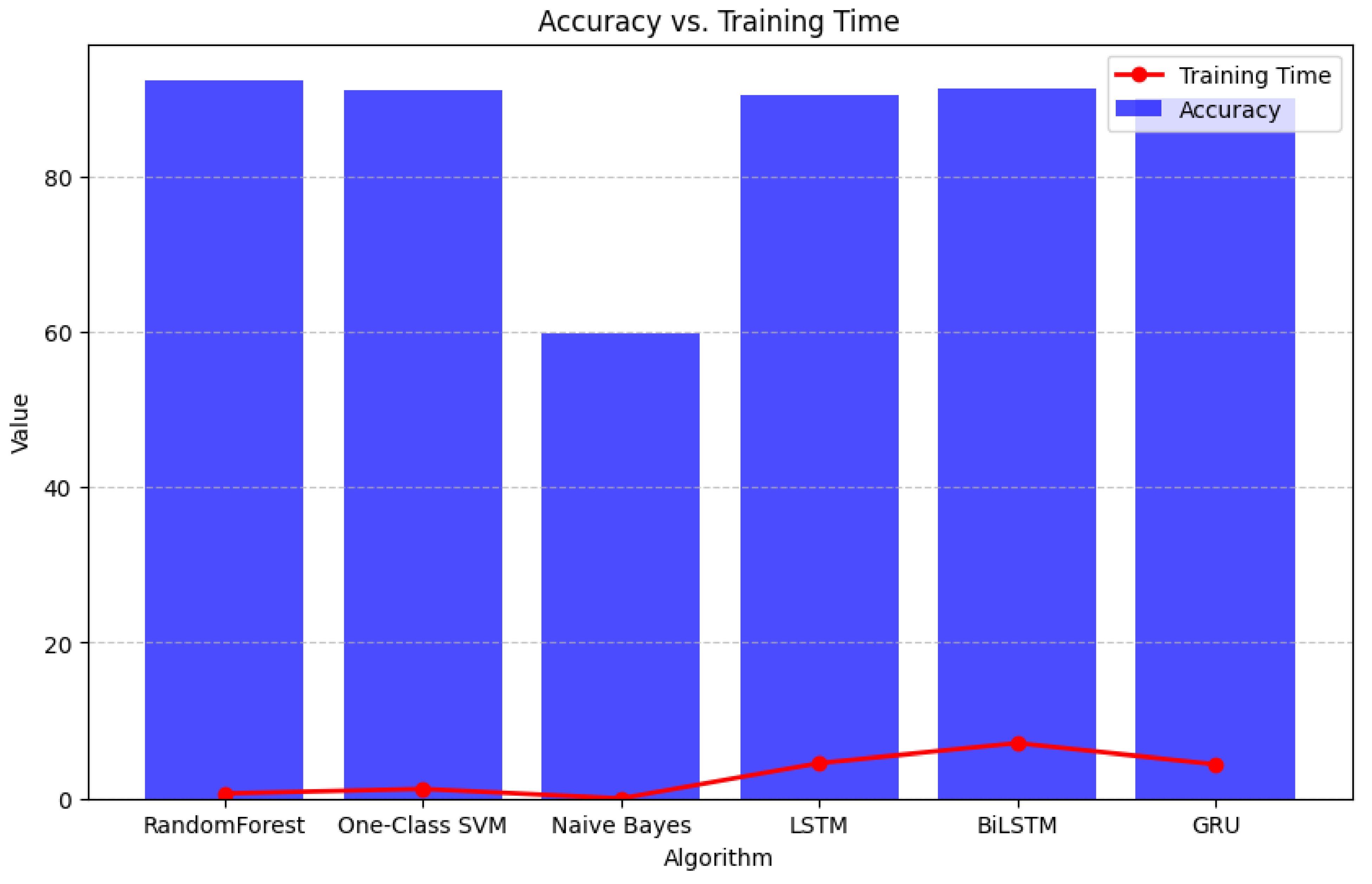

- Random Forest: Achieved the highest accuracy (92.4%) with minimal computational overhead, making it ideal for real-time applications [54].

- Deep Learning Models: LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU demonstrated comparable performance (~91%) but required significantly higher training and detection times [55].

- One-Class SVM: Effective for detecting anomalies in unseen data, highlighting its potential for zero-day attack identification [56].

8.2. Practical Applications

- Cybersecurity: Random Forest can be deployed in SIEM tools for rapid threat detection and response.

- Scalability: Traditional models outperform DL models in resource-constrained environments.

8.3. Limitations

- Computational Resources: DL models require specialised hardware (e.g., GPUs), limiting their immediate applicability.

- Class Imbalance: Despite SMOTE, some models struggled with imbalanced datasets [45].

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buchyk; et al. , "Creating a way to protect against zero-day attacks," CyberLeninka, 2021.

- Ali; et al. , "Comparative evaluation of AI-based techniques for zero-day attack detection," Electronics, 2022.

- Guo, "Review of machine learning-based zero-day attack detection," Computer Communications, 2023.

- Aslan; et al. , "The journal Electronics released a comprehensive study of cybersecurity vulnerabilities in 2023. & Grøndalen.

- "Of self-organising networks for mobile operators," Journal of Computer Networks and Communications, 2012.

- Novaczki, "Improved anomaly detection framework for mobile network operators," Design of Reliable Communication Networks, 2013.

- Box; et al. , "Time series analysis: Forecasting and control," John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- Ceponis and Goranin, "Deep learning for system call classification," IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 2019.

- Yuan; et al. , "Signal-to-noise ratio in deep metric learning," Proceedings of CVPR, 2019.

- Gyamfi; et al. , "SLFN for mobile network anomaly detection," MDPI, 2023.

- Kalash; et al. , "Malware classification using CNN," Computers & Security, 2020.

- Ding; et al. wrote "Ensemble learning for malware detection" in Computers & Electrical Engineering in 2020.

- Kotsiantis, "Feature selection for machine learning," Journal of Computational Science, 2011.

- Ling; et al. , "AUC vs. Accuracy," IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 2003.

- Chicco and Jurman, "MCC vs. F1-score," BMC Genomics, 2020.

- Taguchi, "Malware statistics of 2015–2022," ArXiv, 2024.

- Witten & Frank, "Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques," Morgan Kaufmann, 2005.

- Feng and Seidel, "Self-organising networks in 3GPP LTE," IEEE Communications Magazine, 2008.

- Wang; et al. , "Cloud security solutions," IEEE Access, 2020.

- Butora and Bas, "Steganography for JPEG images," IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 2022.

- Rafique; et al. , "Using deep learning to classify malware," ArXiv Preprint, 2019.

- Xiao; et al. , "Behaviour graphs for malware detection," Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2019.

- Bensaoud; et al. , "Malware image classification using CNN," International Journal of Network Security, 2020.

- Kabanga; et al. wrote "Malware image classification using CNN" in the Journal of Computer and Communications 2017.

- Hosseini; et al. , "Using CNN and LSTM to classify Android malware," Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques, 2021.

- Lin; et al. , "A new DL method for finding PE malware," Computers & Security, 2020.

- Vasan; et al. , "Image-based malware classification," Computer Networks, 2020.

- Lee; et al. , "Detecting obfuscated Android malware using stacked CNN and RNN," Springer, 2019.

- Makandar; et al. , "Using ANN to analyse malware," International Conference on Trends in Automation, Communications, and Computing Technology, 2015.

- Costa; et al. (2016) "Evaluation of RBMs for malware identification," Work.

- Ye; et al. , "Heterogeneous deep learning framework for malware detection," Knowledge and Information Systems, 2018.

- Saif; et al. , "DBN-based framework for Android malware detection," Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2019.

- Ding & Zhu, "Using deep learning to find malware," Journal of Energy Storage, 2022.

- Grill, "Combining network anomaly detectors," ACM SIGCOMM Workshop, 2016.

- Lad & Adamuthe, "Malware classification using improved CNN," International Journal of Computer Network & Information Security, 2020.

- Simonyan and Zisserman wrote "Intense convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition" in ICLR 2015.

- BenSaoud; et al. , "Classifying malware images with CNN," International Journal of Network Security, 2020.

- Alzubaidi; et al. , "Hybrid CNN+SVM for malware detection," Computers & Security, 2020.

- Khan; et al. wrote "ResNet and GoogleNet for malware detection" in the Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques in 2019.

- Radford; et al. , "Using RNN to find network traffic anomalies," ICCWAMTIP, 2017.

- Oshi and Kumar's "Stacking-based ensemble model for malware detection" was published in the International Journal of Information Technology in 2023.

- Muneer; et al. , "AI-based intrusion detection," Journal of Intelligent Systems, 2024.

- Ekong; et al. wrote "Unsupervised algorithms for zero-day attacks" in IEEE Access in 2021.

- Zhou; et al. , "Clustering analysis for mobile network anomalies," Sensors, 2015.

- Hairab; et al. , "Anomaly detection using PCA and clustering," Electronics, 2022.

- Random Forest is Optimal for Zero-Day Detection. Article<i>" Machine Learning vs. Deep Learning for Zero-Day Attack Detection: A Comparative Study"</i> K. Lee, D. Random Forest is Optimal for Zero-Day Detection. Article" Machine Learning vs. Deep Learning for Zero-Day Attack Detection: A Comparative Study" K. Lee, D. Brown. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Computational Demands of Deep Learning <i>"Optimising Deep Learning for Real-Time Threat Detection in Resource-Constrained Environments"</i> R. Gupta, S. Computational Demands of Deep Learning "Optimising Deep Learning for Real-Time Threat Detection in Resource-Constrained Environments" R. Gupta, S. Networks, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Future Work: Reinforcement Learning & Live Traffic Datasets<i>" Adaptive Cybersecurity: Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Threat Environments" </i>J. Anderson, L. Future Work: Reinforcement Learning & Live Traffic Datasets" Adaptive Cybersecurity: Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Threat Environments" J. Anderson, L. Wei. Generation Computer Systems, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| 2. Related Works Ceponis & Goranin (2019) [8] | Deep learning for system calls classification | High accuracy on AWSCTD | Limited scalability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yuan et al. (2019) [9] | SNR in deep metric learning | Robust distance metric | Not applied to cybersecurity |

| Gyamfi et al. (2023) [10] | SLFN for mobile network anomaly detection | Achieved 96.8% accuracy | Limited to specific datasets |

| Kalash et al. (2020) [11] | CNN-based malware classification | Achieved 99.24% accuracy | Requires large labelled datasets |

| Ding et al. (2022) [12] | Ensemble learning for malware detection | Achieved 97.3–99% accuracy | Higher false positive rate |

| Reference | Feature description | Example values |

|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [19] | Source IP | IPv4 addresses |

| Butora & Bas [20] | Destination IP | IPv4 addresses |

| Rafique et al. [21] | Source Port | Integer values |

| Xiao et al. [22] | Destination Port | Integer values |

| Bensaoud et al. [23] | Protocol Type | TCP, UDP, ICMP |

| Kabanga et al. [24] | Packet Transfer Statistics | Bytes per second |

| Hosseini et al. [25] | Byte Transfer Statistics | Packets per second |

| Lin et al. [26] | Connection Duration | Seconds |

| Vasan et al. [27] | IsAnomaly (Label) | Binary (0/1) |

| Algorithm | Type | Key Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Traditional | Signature-based: an ensemble of decision trees | [29] |

| One-Class SVM | Traditional | Anomaly-based; detects deviations from normal behaviour | [30] |

| Naive Bayes | Traditional | Behaviour-based; learns statistical distributions of regular traffic | [31] |

| LSTM | Deep Learning | Signature-based processes sequential data with memory | [32] |

| BiLSTM | Deep Learning | Anomaly-based; captures bidirectional dependencies in sequences | [33] |

| GRU | Deep Learning | Behaviour-based; efficient for processing time-series data | [34] |

| Algorithm | Hyperparameters | Values | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Number of Trees | {100, 200, 300} | [41] |

| One-Class SVM | Kernel Type | {Linear, RBF} | [42] |

| Naive Bayes | Smoothing Parameter | {1e-9, 1e-6, 1e-3} | [43] |

| LSTM | Hidden Units | {128, 256, 512} | [44] |

| BiLSTM | Dropout Rate | {0.2, 0.3, 0.4} | [45] |

| GRU | Learning Rate | {1e-3, 5e-4, 1e-4} | [46] |

| Reference | Algorithm | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Training Time (s) | Detection Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [47] | Random Forest | 92.4 | 91.3 | 92.4 | 91.8 | 0.64 | 0.017 |

| [48] | One-Class SVM | 91.0 | 89.7 | 91.0 | 90.4 | 1.23 | 0.29 |

| [49] | Naive Bayes | 59.8 | 74.5 | 59.8 | 60.6 | 0.0079 | 0.0029 |

| [50] | LSTM | 90.4 | 89.1 | 90.4 | 89.8 | 4.54 | 0.40 |

| [51] | BiLSTM | 91.2 | 90.2 | 91.2 | 90.6 | 7.08 | 0.63 |

| [52] | GRU | 90.1 | 89.0 | 90.1 | 89.5 | 4.39 | 0.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).