Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

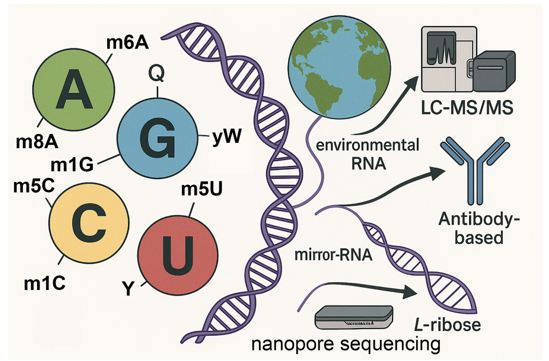

1. Introduction

- RNA export: m⁵C can play a role in transporting mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm.

- Translation: Both m⁵C and Ψ can influence the rate and fidelity of protein synthesis, potentially even leading to alternative protein products.

- mRNA stability: Ψ, for example, can enhance mRNA stability by affecting its structure and protecting it from degradation.

- Development and disease: Alterations in these modifications are linked to various physiological and pathological processes, including embryonic development and tumor formation.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Ranking of mRNA Modifications by PubMed Prevalence

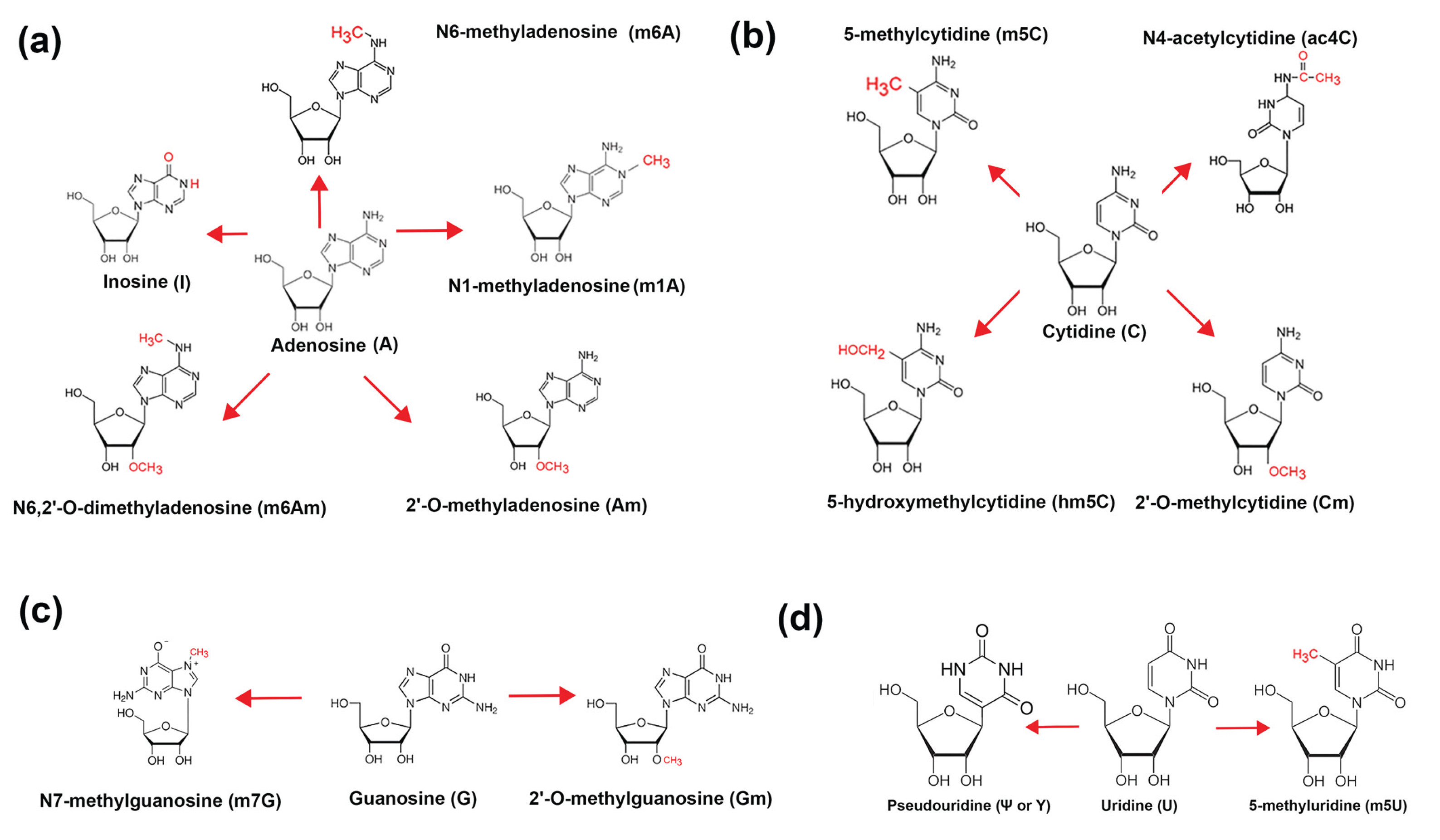

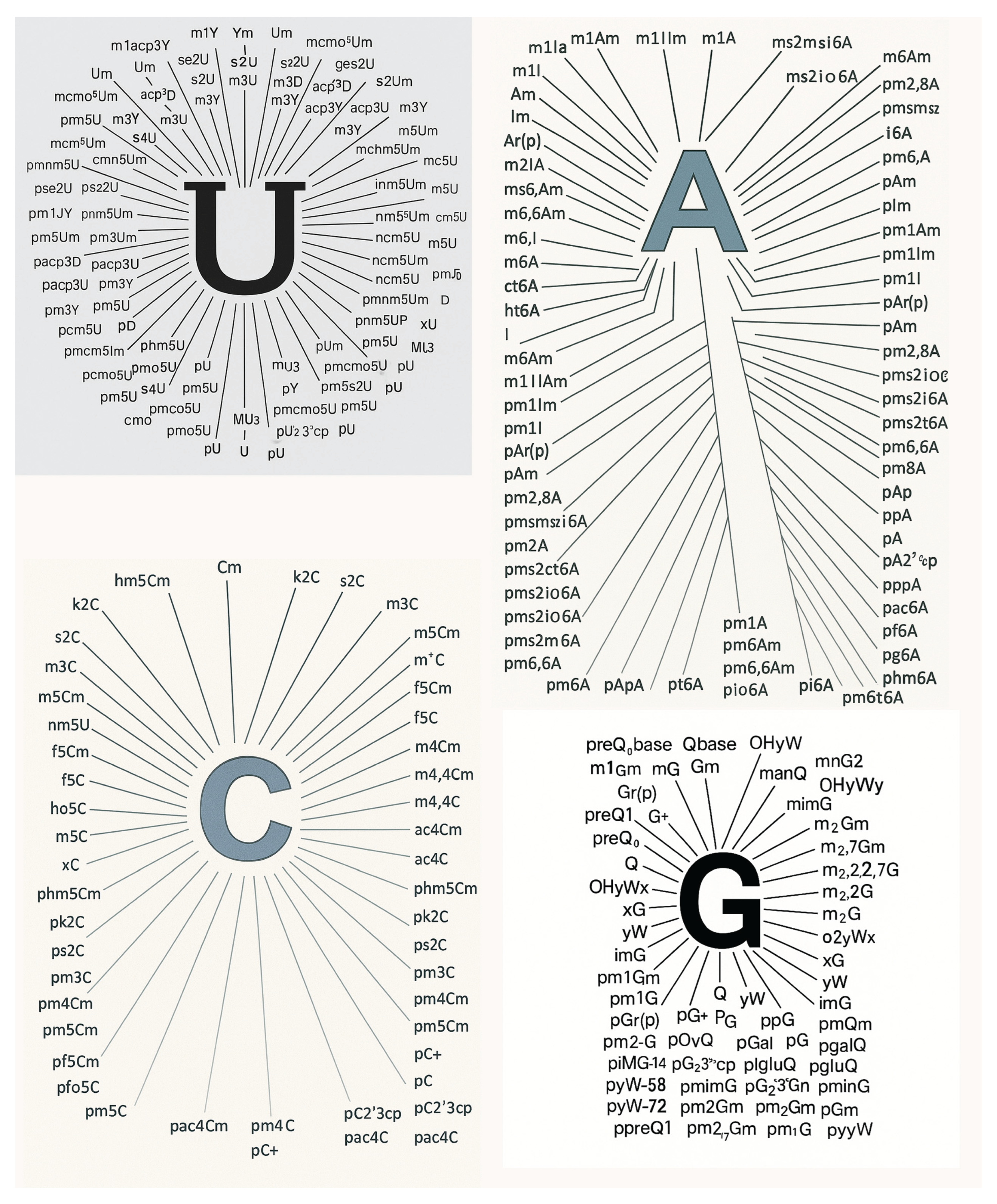

- N6-methyladenosine (m6A) ranked first with over 7,000 citations. This modification is extensively studied due to its widespread presence in mRNAs and its central roles in splicing, export, translation efficiency, and decay. Its regulation by “writers” (METTL3/14) (m6A methyltransferase 3/14), “erasers” (FTO, ALKBH5) (Fatso alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase, AlkB homolog 5), and “readers” has defined the emerging field of epitranscriptomics (reviewed in [25,26]).

- Pseudouridine (Ψ) was second, with ~1,000 citations. Once thought to be restricted to non-coding RNAs, Ψ is now recognized as a key player in mRNA stability, stress response, and synthetic mRNA vaccine design. Enzymes like PUS1 and PUS7 catalyze site-specific isomerization [27].

- 5-methylcytidine (m5C), with ~800 citations, modulates mRNA stability and nuclear export. It is written by NSUN2 (NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 2) and DNMT2 (DNA/RNA Nucleotide Methyltransferase 2) and may act in conjunction with binding proteins such as ALYREF (Aly/REF Export Factor) to regulate cytoplasmic localization [28,29,30].

- N1-methyladenosine (m1A), with ~400 publications, affects translation initiation and mRNA secondary structure. Though less abundant, its functional impact can be significant in mitochondrial and stress-induced contexts [33].

- 5’ Cap modifications (Cap0, Cap1, Cap2) had ~300 citations combined. These modifications, installed by RNGTT (RNA Guanylyltransferase And 5’-Phosphatase), RNMT (RNA guanine-7 methyltransferase), CMTR1/2 (Cap MethylTRansferase), help evade innate immune detection and regulate cap-dependent translation [36,37].

- 5-methyluridine (m5U) and 2’-O-methyladenosine (Am) each had <100 citations, reflecting their recent or understudied roles in mRNA, although both are common in tRNA. TRMT2A/B (TRNA Methyltransferase 2 Homolog A) and FTSJ1 (FtsJ RNA 2’-O-Methyltransferase 1) are the main associated enzymes, respectively [38,39].

- N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) (<50 citations) is a stress-responsive modification installed by NAT10 (N-acetyltransferase 10), linked to increased translation and mRNA stability [40].

- N7-methylguanosine (m7G) (<50 citations) forms part of the 5’ cap structure but has also been detected internally in some mRNAs. It plays roles in nuclear export and translation. Recent studies have suggested that mRNA internal m7G and its writer protein METTL1 (Methyltransferase 1, tRNA Methylguanosine) are closely related to cell metabolism and cancer regulation. The IGF2BP (Insulin Growth Factor 2 Binding Protein) family proteins IGF2BP1-3 can preferentially bind internal mRNA m7G and regulate mRNA stability [41].

- 2’-O-methylguanosine (Gm) and 2’-O-methylcytidine (Cm) each had <30 citations. These modifications occur both in cap-adjacent and internal positions, potentially contributing to mRNA longevity and translation efficiency [42].

- 5-hydroxymethylcytidine (hm5C) (<20 citations) has a poorly defined role in RNA, though its presence suggests possible epigenetic-like regulation analogous to its role in DNA (reviewed in [28]).

- Finally, co-modified m6A/Ψ sites had <10 citations, indicating a nascent field exploring combinatorial regulation of RNA structure and function at dual-modified loci. Long read nanopore sequencing is especially adept at discovering co-modified mRNAs [8].

3.2. Interpretation of Modification Ranking

3.3. Disease Relevance of Top RNA Modifications

| Rank | Modification | Abbreviation | Enzyme(s) | Role | Estimated PubMed Citations | Reference(s) |

| 1 | N6-methyladenosine | m6A | METTL3, METTL14, FTO, ALKBH5 | Splicing, translation, decay, export | >7000 | [61,62,63] |

| 2 | Pseudouridine | Ψ | PUS1, PUS7 | Stability, decoding, stress response | ~1000 | [64,65] |

| 3 | 5-methylcytidine | m5C | NSUN2, DNMT2 | Export, stability | ~800 | [66,67] |

| 4 | Inosine | I | ADAR1, ADAR2 | A-to-I editing, recoding | ~750 | [68] |

| 5 | N1-methyladenosine | m1A | TRMT6/TRMT61A | Translation initiation, structure | ~400 | [69,70] |

| 6 | N6,2’-O-dimethyladenosine | m6Am | PCIF1 | Cap-proximal stability | ~200 | [71] |

| 7 | 5’ cap modifications | Cap0, Cap1, Cap2 | RNGTT, RNMT, CMTR1, CMTR2 | Immune evasion, translation | ~150–300 | [72,73] |

| 8 | 5-methyluridine | m5U | TRMT2A/B | tRNA-like stability role in mRNA | <100 | [74] |

| 9 | 2’-O-methyladenosine | Am | FTSJ1, CMTR1 | Cap stability and processing | <100 | [73,75] |

| 10 | N4-acetylcytidine | ac4C | NAT10 | Translation, stress response | <50 | [76] |

| 11 | N7-methylguanosine | m7G | RNGTT, RNMT, METTL1 | 5’ cap structure, nuclear export | <50 | [72,77] |

| 12 | 2’-O-methylguanosine | Gm | CMTR2 | Cap and internal stability | <30 | [72,73] |

| 13 | 2’-O-methylcytidine | Cm | FTSJ1 | Stability, cap modification | <30 | [39] |

| 14 | 5-hydroxymethylcytidine | hm5C | TET2 | Epigenetic-like regulation | <20 | [78] |

| 15 | m6A:Ψ co-modified sites | m6A/Ψ | Multiple | Dynamic regulation, RNA structure | <10 | [78] |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| POLET | Preprokaryotic Organismal Lifeforms Existing Today |

| m6A | N6-methyladenosine |

| Ψ | Pseudouridine |

| m5C | 5-methylcytidine |

| I | Inosine |

| m1A | N1-methyladenosine |

| m6Am | N6,2’-O-dimethyladenosine |

| Cap0, Cap1, Cap2 | 5’ cap modifications using m7G |

| m5U | 5-methyluridine |

| Am | 2’-O-methyladenosine |

| ac4C | N4-acetylcytidine |

| m7G | N7-methylguanosine |

| Gm | 2’-O-methylguanosine |

| Cm | 2’-O-methylcytidine |

| hm5C | 5-hydroxymethylcytidine |

| m6A/Ψ | m6A:Ψ co-modified sites |

References

- Alasar, A.A., et al., Genomewide m(6)A Mapping Uncovers Dynamic Changes in the m(6)A Epitranscriptome of Cisplatin-Treated Apoptotic HeLa Cells. Cells, 2022. 11(23). [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.D. and S.R. Jaffrey, The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2014. 15(5): p. 313-26. [CrossRef]

- Pilala, K.M., et al., Exploring the methyl-verse: Dynamic interplay of epigenome and m6A epitranscriptome. Mol Ther, 2025. 33(2): p. 447-464. [CrossRef]

- Cappannini, A., et al., MODOMICS: a database of RNA modifications and related information. 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res, 2024. 52(D1): p. D239-D244. [CrossRef]

- Dominissini, D., et al., Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature, 2012. 485(7397): p. 201-6. [CrossRef]

- Tegowski, M., et al., Single-cell m(6)A profiling in the mouse brain uncovers cell type-specific RNA methylomes and age-dependent differential methylation. Nat Neurosci, 2024. 27(12): p. 2512-2520. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., et al., Defining context-dependent m(6)A RNA methylomes in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell, 2024. 59(20): p. 2772-2786 e3. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., A.C. Wylder, and T. Pan, Simultaneous nanopore profiling of mRNA m(6)A and pseudouridine reveals translation coordination. Nat Biotechnol, 2024. 42(12): p. 1831-1835. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., et al., Quantitative RNA pseudouridine maps reveal multilayered translation control through plant rRNA, tRNA and mRNA pseudouridylation. Nat Plants, 2025. 11(2): p. 234-247. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G., et al., Advances in mRNA 5-methylcytosine modifications: Detection, effectors, biological functions, and clinical relevance. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids, 2021. 26: p. 575-593. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., et al., The Quiet Giant: Identification, Effectors, Molecular Mechanism, Physiological and Pathological Function in mRNA 5-methylcytosine Modification. Int J Biol Sci, 2024. 20(15): p. 6241-6254. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., J. Meng, and Y. Zhang, Quantitative profiling N1-methyladenosine (m1A) RNA methylation from Oxford nanopore direct RNA sequencing data. Methods, 2024. 228: p. 30-37. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al., Research progress of N1-methyladenosine RNA modification in cancer. Cell Commun Signal, 2024. 22(1): p. 79. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, H.G. and P.A. Beal, Structural and functional effects of inosine modification in mRNA. RNA, 2024. 30(5): p. 512-520. [CrossRef]

- Poyau, A., et al., Identification and relative quantification of adenosine to inosine editing in serotonin 2c receptor mRNA by CE. Electrophoresis, 2007. 28(16): p. 2843-52. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L. and P. Yin, Upregulated m7G methyltransferase METTL1 is a potential biomarker and tumor promoter in skin cutaneous melanoma. Front Immunol, 2025. 16: p. 1575219. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., et al., The m(7)G methylation modification: An emerging player of cardiovascular diseases. Int J Biol Macromol, 2025. 309(Pt 3): p. 142940. [CrossRef]

- Akichika, S. and T. Suzuki, Cap-specific m(6)Am modification: A transcriptional anti-terminator by sequestering PCF11 with implications for neuroblastoma therapy. Mol Cell, 2024. 84(21): p. 4051-4052. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F., CROWN-seq reveals m(6)Am landscapes and transcription start site diversity. Nat Rev Genet, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dohnalkova, M., et al., Essential roles of RNA cap-proximal ribose methylation in mammalian embryonic development and fertility. Cell Rep, 2023. 42(7): p. 112786. [CrossRef]

- Kishore, U. and T.A. Kufer, Editorial: Updates on RIG-I-like receptor-mediated innate immune responses. Front Immunol, 2023. 14: p. 1153410. [CrossRef]

- Kouwaki, T., et al., RIG-I-Like Receptor-Mediated Recognition of Viral Genomic RNA of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 and Viral Escape From the Host Innate Immune Responses. Front Immunol, 2021. 12: p. 700926. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al., MeRIP-PF: an easy-to-use pipeline for high-resolution peak-finding in MeRIP-Seq data. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics, 2013. 11(1): p. 72-5. [CrossRef]

- Hawley, B.R. and S.R. Jaffrey, Transcriptome-Wide Mapping of m(6) A and m(6) Am at Single-Nucleotide Resolution Using miCLIP. Curr Protoc Mol Biol, 2019. 126(1): p. e88.

- Dong, Q., et al., N6-Methyladenosine Modification of the Three Components “Writers”, “Erasers”, and “Readers” in Relation to Osteogenesis. Int J Mol Sci, 2025. 26(12).

- Wang, S., et al., New Targets for Immune Inflammatory Response in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Focus on the Potential Significance of N6-Methyladenosine, Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis. J Inflamm Res, 2025. 18: p. 8085-8106. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.S., et al., BID-seq for transcriptome-wide quantitative sequencing of mRNA pseudouridine at base resolution. Nat Protoc, 2024. 19(2): p. 517-538. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., et al., 5-methylcytosine RNA methyltransferases and their potential roles in cancer. J Transl Med, 2022. 20(1): p. 214. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X., et al., Pan-cancer analysis of RNA 5-methylcytosine reader (ALYREF). Oncol Res, 2024. 32(3): p. 503-515. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., et al., 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export - NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m(5)C reader. Cell Res, 2017. 27(5): p. 606-625. [CrossRef]

- Roth, S.H., E.Y. Levanon, and E. Eisenberg, Genome-wide quantification of ADAR adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing activity. Nat Methods, 2019. 16(11): p. 1131-1138. [CrossRef]

- Yuting, K., D. Ding, and H. Iizasa, Adenosine-to-Inosine RNA Editing Enzyme ADAR and microRNAs. Methods Mol Biol, 2021. 2181: p. 83-95.

- Deng, Y., et al., N1-methyladenosine RNA methylation patterns are associated with an increased risk to biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer and serve as a potential novel biomarker for patient stratification. Int Immunopharmacol, 2024. 143(Pt 2): p. 113404. [CrossRef]

- Mauer, J., et al., Reversible methylation of m(6)A(m) in the 5’ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature, 2017. 541(7637): p. 371-375. [CrossRef]

- Sugita, A., et al., Cap-Specific m(6)Am Methyltransferase PCIF1/CAPAM Regulates mRNA Stability of RAB23 and CNOT6 through the m(6)A Methyltransferase Activity. Cells, 2024. 13(20).

- Chen, P., et al., Capping Enzyme mRNA-cap/RNGTT Regulates Hedgehog Pathway Activity by Antagonizing Protein Kinase A. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 2891. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, L.A., et al., Characterisation of RNA guanine-7 methyltransferase (RNMT) using a small molecule approach. Biochem J, 2025. 482(4). [CrossRef]

- Witzenberger, M., et al., Human TRMT2A methylates tRNA and contributes to translation fidelity. Nucleic Acids Res, 2023. 51(16): p. 8691-8710. [CrossRef]

- Freude, K., et al., Mutations in the FTSJ1 gene coding for a novel S-adenosylmethionine-binding protein cause nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet, 2004. 75(2): p. 305-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.C., et al., Inhibition of tumor-intrinsic NAT10 enhances antitumor immunity by triggering type I interferon response via MYC/CDK2/DNMT1 pathway. Nat Commun, 2025. 16(1): p. 5154.

- Liu, C., et al., IGF2BP3 promotes mRNA degradation through internal m(7)G modification. Nat Commun, 2024. 15(1): p. 7421. [CrossRef]

- Tardu, M., et al., Identification and Quantification of Modified Nucleosides in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNAs. ACS Chem Biol, 2019. 14(7): p. 1403-1409. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., et al., Machine learning-augmented m6A-Seq analysis without a reference genome. Brief Bioinform, 2025. 26(3). [CrossRef]

- Carlile, T.M., M.F. Rojas-Duran, and W.V. Gilbert, Pseudo-Seq: Genome-Wide Detection of Pseudouridine Modifications in RNA. Methods Enzymol, 2015. 560: p. 219-45.

- Suzuki, T., et al., Transcriptome-wide identification of adenosine-to-inosine editing using the ICE-seq method. Nat Protoc, 2015. 10(5): p. 715-32. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q. and Q. Zhang, Translating the m(6)A epitranscriptome for prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Feng, B., et al., Transcriptomic Analysis of the m6A Reader YTHDF2 in the Maintenance and Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Widagdo, J. and V. Anggono, The m6A-epitranscriptomic signature in neurobiology: from neurodevelopment to brain plasticity. J Neurochem, 2018. 147(2): p. 137-152. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., et al., METTL3/YTDHF1 Stabilizes MTCH2 mRNA to Regulate Ferroptosis in Glioma Cells. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed), 2025. 30(2): p. 25718.

- Liu, X., et al., Novel Associations Between METTL3 Gene Polymorphisms and Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Five-Center Case-Control Study. Front Oncol, 2021. 11: p. 635251.

- Wang, S., et al., M6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes glucose metabolism hub gene expression and induces metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). BMC Genomics, 2025. 26(1): p. 188. [CrossRef]

- Morais, P., H. Adachi, and Y.T. Yu, The Critical Contribution of Pseudouridine to mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021. 9: p. 789427. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Moheb, L., et al., Mutations in NSUN2 cause autosomal-recessive intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet, 2012. 90(5): p. 847-55. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., et al., A novel variant in NSUN2 causes intellectual disability in a Chinese family. BMC Med Genomics, 2024. 17(1): p. 95. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., FOXA1-dependent NSUN2 facilitates the advancement of prostate cancer by preserving TRIM28 mRNA stability in a m5C-dependent manner. NPJ Precis Oncol, 2025. 9(1): p. 127. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., S. Okada, and M. Sakurai, Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing in neurological development and disease. RNA Biol, 2021. 18(7): p. 999-1013. [CrossRef]

- Cui, N., et al., Extracellular Inosine Induces Anergy in B Cells to Alleviate Autoimmune Hepatitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2025: p. 101539. [CrossRef]

- Alriquet, M., et al., The protective role of m1A during stress-induced granulation. J Mol Cell Biol, 2021. 12(11): p. 870-880. [CrossRef]

- Ren, M., et al., Exploration and validation of a combined Hypoxia and m6A/m5C/m1A regulated gene signature for prognosis prediction of liver cancer. BMC Genomics, 2023. 24(1): p. 776. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., et al., NAT10 inhibition alleviates astrocyte autophagy by impeding ac4C acetylation of Timp1 mRNA in ischemic stroke. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2025. 15(5): p. 2575-2592. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., et al., A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol, 2014. 10(2): p. 93-5. [CrossRef]

- Jia, G., et al., N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol, 2011. 7(12): p. 885-7. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G., et al., ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell, 2013. 49(1): p. 18-29. [CrossRef]

- Patton, J.R., et al., Mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA): missense mutation in the pseudouridine synthase 1 (PUS1) gene is associated with the loss of tRNA pseudouridylation. J Biol Chem, 2005. 280(20): p. 19823-8.

- de Brouwer, A.P.M., et al., Variants in PUS7 Cause Intellectual Disability with Speech Delay, Microcephaly, Short Stature, and Aggressive Behavior. Am J Hum Genet, 2018. 103(6): p. 1045-1052.

- Moon, H.J. and K.L. Redman, Trm4 and Nsun2 RNA:m5C methyltransferases form metabolite-dependent, covalent adducts with previously methylated RNA. Biochemistry, 2014. 53(45): p. 7132-44.

- Schaefer, M., et al., Azacytidine inhibits RNA methylation at DNMT2 target sites in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res, 2009. 69(20): p. 8127-32. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, A., et al., Tad1p, a yeast tRNA-specific adenosine deaminase, is related to the mammalian pre-mRNA editing enzymes ADAR1 and ADAR2. EMBO J, 1998. 17(16): p. 4780-9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., et al., RNA m1A Methyltransferase TRMT6 Predicts Poorer Prognosis and Promotes Malignant Behavior in Glioma. Front Mol Biosci, 2021. 8: p. 692130. [CrossRef]

- Chujo, T. and T. Suzuki, Trmt61B is a methyltransferase responsible for 1-methyladenosine at position 58 of human mitochondrial tRNAs. RNA, 2012. 18(12): p. 2269-76. [CrossRef]

- Akichika, S., et al., Cap-specific terminal N (6)-methylation of RNA by an RNA polymerase II-associated methyltransferase. Science, 2019. 363(6423).

- Pillutla, R.C., et al., Human mRNA capping enzyme (RNGTT) and cap methyltransferase (RNMT) map to 6q16 and 18p11.22-p11.23, respectively. Genomics, 1998. 54(2): p. 351-3. [CrossRef]

- Belanger, F., et al., Characterization of hMTr1, a human Cap1 2’-O-ribose methyltransferase. J Biol Chem, 2010. 285(43): p. 33037-33044.

- Carter, J.M., et al., FICC-Seq: a method for enzyme-specified profiling of methyl-5-uridine in cellular RNA. Nucleic Acids Res, 2019. 47(19): p. e113. [CrossRef]

- Guy, M.P., et al., Yeast Trm7 interacts with distinct proteins for critical modifications of the tRNAPhe anticodon loop. RNA, 2012. 18(10): p. 1921-33. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., et al., DNA damage induces N-acetyltransferase NAT10 gene expression through transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biochem, 2007. 300(1-2): p. 249-58. [CrossRef]

- Bahr, A., et al., Molecular analysis of METTL1, a novel human methyltransferase-like gene with a high degree of phylogenetic conservation. Genomics, 1999. 57(3): p. 424-8. [CrossRef]

- Fan, W., et al., Tet2 modulates M2 macrophage polarization via mRNA 5-methylcytosine in allergic rhinitis. Int Immunopharmacol, 2024. 143(Pt 3): p. 113495. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.D., et al., Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell, 2012. 149(7): p. 1635-46. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., et al., Evolutionary Origins and Adaptive Significance of A-to-I RNA Editing in Animals and Fungi. Bioessays, 2025. 47(5): p. e202400220. [CrossRef]

- Potuznik, J.F. and H. Cahova, If the 5’ cap fits (wear it) - Non-canonical RNA capping. RNA Biol, 2024. 21(1): p. 1-13.

- Pajdzik, K., et al., Chemical manipulation of m(1)A mediates its detection in human tRNA. RNA, 2024. 30(5): p. 548-559. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G., et al., Disease Activity-Associated Alteration of mRNA m(5) C Methylation in CD4(+) T Cells of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2020. 8: p. 430. [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K., M. Mizugaki, and N. Ishida, Detection of elevated amounts of urinary pseudouridine in cancer patients by use of a monoclonal antibody. Clin Chim Acta, 1989. 181(3): p. 305-15. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. and M. Sinha, Targeting intracellular mRNA m(6)A-modifiers in advancing immunotherapeutics. J Adv Res, 2025.

- Ranga, S., et al., Modifications of RNA in cancer: a comprehensive review. Mol Biol Rep, 2025. 52(1): p. 321. [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J., et al., The RMaP challenge of predicting RNA modifications by nanopore sequencing. Commun Chem, 2025. 8(1): p. 115.

- Xu, Y. and T.F. Zhu, Mirror-image T7 transcription of chirally inverted ribosomal and functional RNAs. Science, 2022. 378(6618): p. 405-412. [CrossRef]

- Service, R.F., A big step toward mirror-image ribosomes. Science, 2022. 378(6618): p. 345-346. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Y. Dantsu, and W. Zhang, Construction of a Mirror-Image RNA Nanostructure for Enhanced Biostability and Drug Delivery Efficiency. ACS Biomater Sci Eng, 2025. 11(4): p. 2408-2421. [CrossRef]

- Adamala, K.P., et al., Confronting risks of mirror life. Science, 2024. 386(6728): p. 1351-1353. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).