1. Introduction

Breast cancer screening is essential for detecting early-stage disease and significantly improving patient survival rates [

1,

2]. especially as breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women in 157 out of 185 countries [

3]. Screening guidelines serve as valuable tools for clinical decision-making, offering evidence-based recommendations. it underscores the significance of investigating and observing medical imaging devices for effective early diagnosis [

4]. While many developed countries have established screening pathways, there is variation in guidelines regarding screening age, methods, and intervals due to differences in institutional evidence and development processes [

5]. Many countries utilize a triage method for breast cancer screening [

6], emphasizing the importance of early detection in increasing survival rates [

7]. Studies have found that cancer care heavily relies on imaging techniques, particularly through screening processes [

4]. Before formal screening begins, individuals may either perform a breast self-examination (BSE) and, if they notice any concerns, consult their general practitioner, or they may be invited to attend a Clinical Breast Examination (CBE).

1.1. First Stage-Clinical Breast Examination

The first stage of screening is a clinical breast examination, (CBE). It’s a low-risk, cost-effective method for early detection [

8],It is recommended following a self-breast exam if any abnormalities are detected. Studies have found that CBE can be an important complement to mammography (MAM) in the earlier detection of breast cancer [

9], as well as detecting cancers missed by MAM [

10,

11]. However, there is insufficient evidence regarding the effectiveness of CBE in reducing mortality as a screening tool for breast cancer [

11]. Conflicting recommendations and unclear guidelines contribute to the controversy surrounding its usefulness [

9,

12]. However, evidence suggests that when a comprehensive and well-executed CBE is performed, particularly by physicians, it may achieve mortality outcomes comparable to MAM, despite CBE’s generally lower sensitivity [

12]. This discrepancy could be due to factors such as inadequate training in CBE techniques or discomfort in performing these examinations [

9].

1.2. Second Stage-Medical Imaging

1.2.1. Mammography

The second stage of screening involves medical imaging, with MAM being the initial choice as it is widely regarded as the gold standard [

13,

14], due to its established effectiveness [

15] and its decreased mortality rates [

16] by 22% worldwide [

17], reduced treatment morbidity and reduced years of life lost by 30% [

18,

19]. The recommended age for starting MAM screening is 45 in the United States and China, while in India, it is 40 to optimize breast cancer management [

20,

21,

22]. MAM-based screening facilitates the earlier identification of breast cancer [

18] andhas demonstrated effectiveness and proven beneficial for women aged 50-74 years [

14,

23].

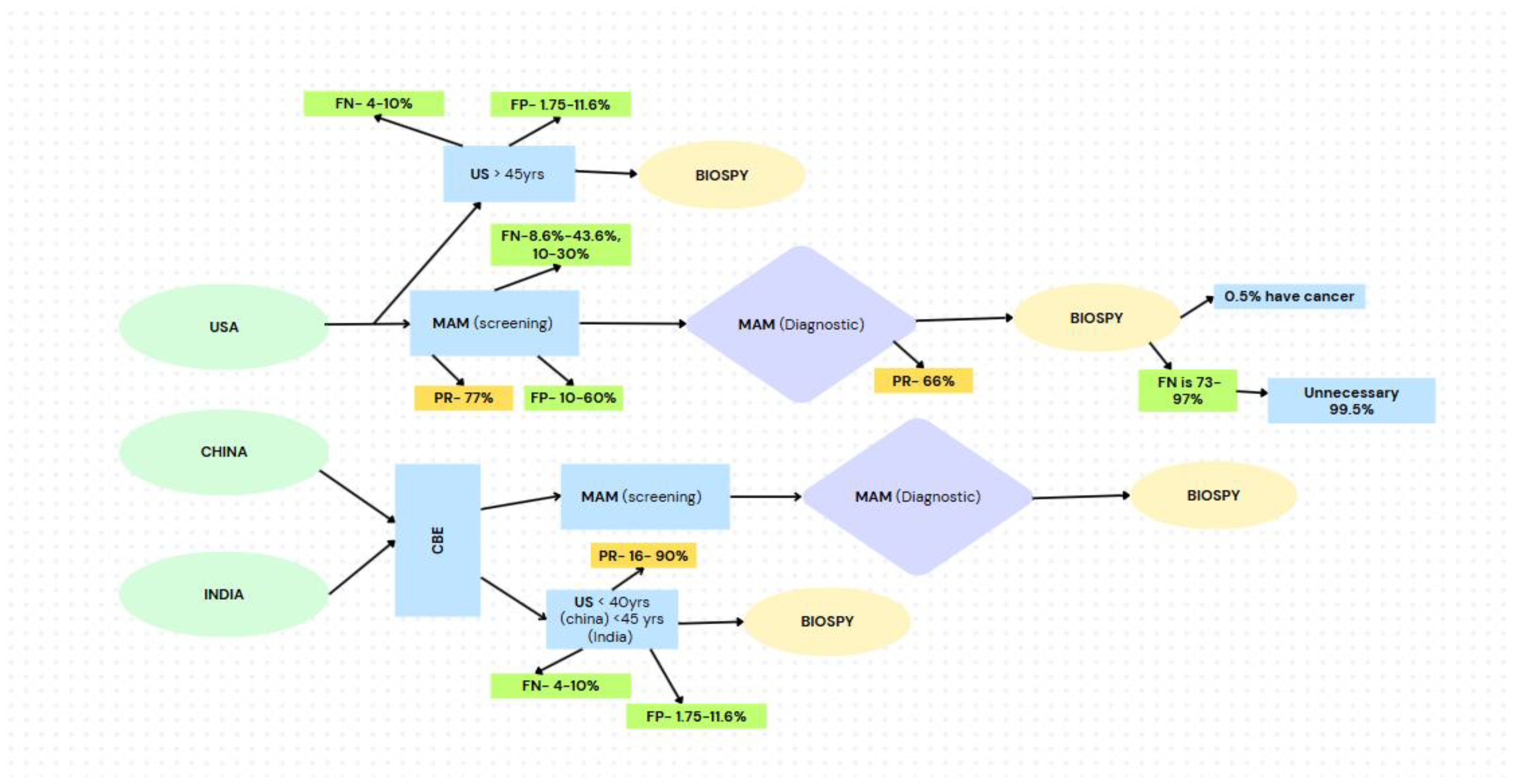

However, limitations arise with MAM, especially in cases involving dense breasts or breast implants, including silicone [

24], which can complicate visual interpretation and lead to errors of omission, potentially resulting in the oversight of certain cancers [

25] as shown in

Figure 1. Despite technological advancements, high rates of false negatives and false positives have remained prevalent [

26], contributing to overdiagnosis, patient anxiety, and the potential for radiation-induced harm [

27]. False-negative rates for MAM have been reported to range widely, from 8.6% to as high as 43.6%, and between 10% to 30% in various studies [

28], highlighting a critical limitation of this modality [

28,

29].

A false-negative MAM is particularly concerning, as it may falsely reassure patients and delay both diagnosis and timely initiation of treatment, potentially compromising outcomes. Nevertheless, the considerable diagnostic benefits of advanced imaging techniques outweigh these concerns [

30].

When abnormalities are detected in MAM, further investigation with ultrasound (US) is crucial, particularly for imaging dense breast tissue [

31,

32]. Given the complexity and risks associated with breast cancer, relying solely on MAM is increasingly insufficient. Integrating additional methods like MRI, US and emerging technologies such as tactile imaging (TI) offers a more comprehensive strategy for early detection [

33].

1.2.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is often used for high-risk patients due to its high sensitivity, especially in detecting cancers that may be missed by MAM [

35]. The American College of Radiology recommends annual MRI screenings for women with a 20% or greater lifetime risk of developing breast cancer, as well as other high-risk populations [

36].

Despite its diagnostic advantages, access to MRI remains limited, especially in low- and middle-income countries, due to its high cost and dependence on medical insurance coverage, placing a substantial financial burden on many women [

37].

While MRI outperforms MAM, particularly in high-risk breast cancer screening and in women with dense, its use in average-risk women is constrained by relatively low specificity constrained by relatively low specificity leading to FP rates of 8–17% and FN rates of approximately 0.4% [

38,

39]. These limitations often result in unnecessary biopsies, increased anxiety, and higher healthcare expenditures. Moreover, MRI is not optimal for detecting microcalcifications, a key early indicator of certain breast cancers, further restricting its utility as a standalone modality [

35].

In countries such as India, where access to MRI is limited and cost-prohibitive, US is frequently employed as a viable alternative for high-risk screening. US is especially valuable for women who are not suitable candidates for MRI due to contraindications or limited healthcare access [

40]. Its widespread availability, affordability, and efficacy in imaging dense breast tissue have made US the preferred modality in many high-risk screening protocols across resource-limited settings [

41]. This strategic use of US, particularly when MRI is inaccessible, enhances the inclusivity of screening programs and underscores the need for adaptable, resource-sensitive diagnostic pathways in global breast cancer care.

1.2.3. Ultrasound

Ultrasound plays a significant role in breast cancer detection and is increasingly recognized as a valuable adjunctive screening modality due to its widespread availability, relatively low cost, and high patient tolerance [

42,

43]. As a non-invasive technique free from ionizing radiation, US offers real-time imaging with high spatial resolution, enabling detailed visualization of breast tissue architecture [

44,

45]. US is particularly effective in imaging palpable abnormalities, distinguishing cystic from solid masses, and identifying suspicious features that may necessitate biopsy [

1,

2,

3]. Moreover, it is highly effective in dense breast tissue, where mammography often underperforms, detecting cancers that might otherwise be missed [

49,

50]. Its ability to guide biopsies further enhances its clinical utility [

1,

2,

3].

In terms of diagnostic performance, US exhibits variability across different healthcare settings. In the United States, false-negative rates have been reported as low as 1.75%, while false-positive rates range from 4% to 10% [

51,

52], underscoring a generally favourable balance between sensitivity and specificity. In contrast, data from China show slightly higher false-positive rates, reported at 10.4% and 11.6% across different screening cohorts [

53,

54], likely reflecting differences in implementation protocols, operator training, and population characteristics. Participation in ultrasound screening programs in China has also varied widely, from 16% to 90%, reflecting both regional disparities and growing acceptance of US as a screening tool [

55].

Despite these advantages, US does have limitations. Its reliance on cross-sectional imaging restricts the field of view, and interpretation is highly operator-dependent, introducing potential variability in diagnostic accuracy [

56]. In low-resource settings such as India and China, US and clinical breast examination (CBE) are often employed as primary screening tools due to the limited availability and high cost of mammography [

57]. In rural areas, these constraints contribute to delayed diagnoses and an increasing burden of disease [

58,

59].

Furthermore, the earlier onset of breast cancer in Indian women compared to Western populations strengthens the rationale for adopting US as a frontline modality in younger age groups [

60]. Given its portability, affordability, and diagnostic versatility, breast ultrasound holds significant promise not only as a complement to mammography in high-resource settings, but also as a frontline screening tool in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where its implementation could substantially enhance early detection and reduce breast cancer mortality [

61].

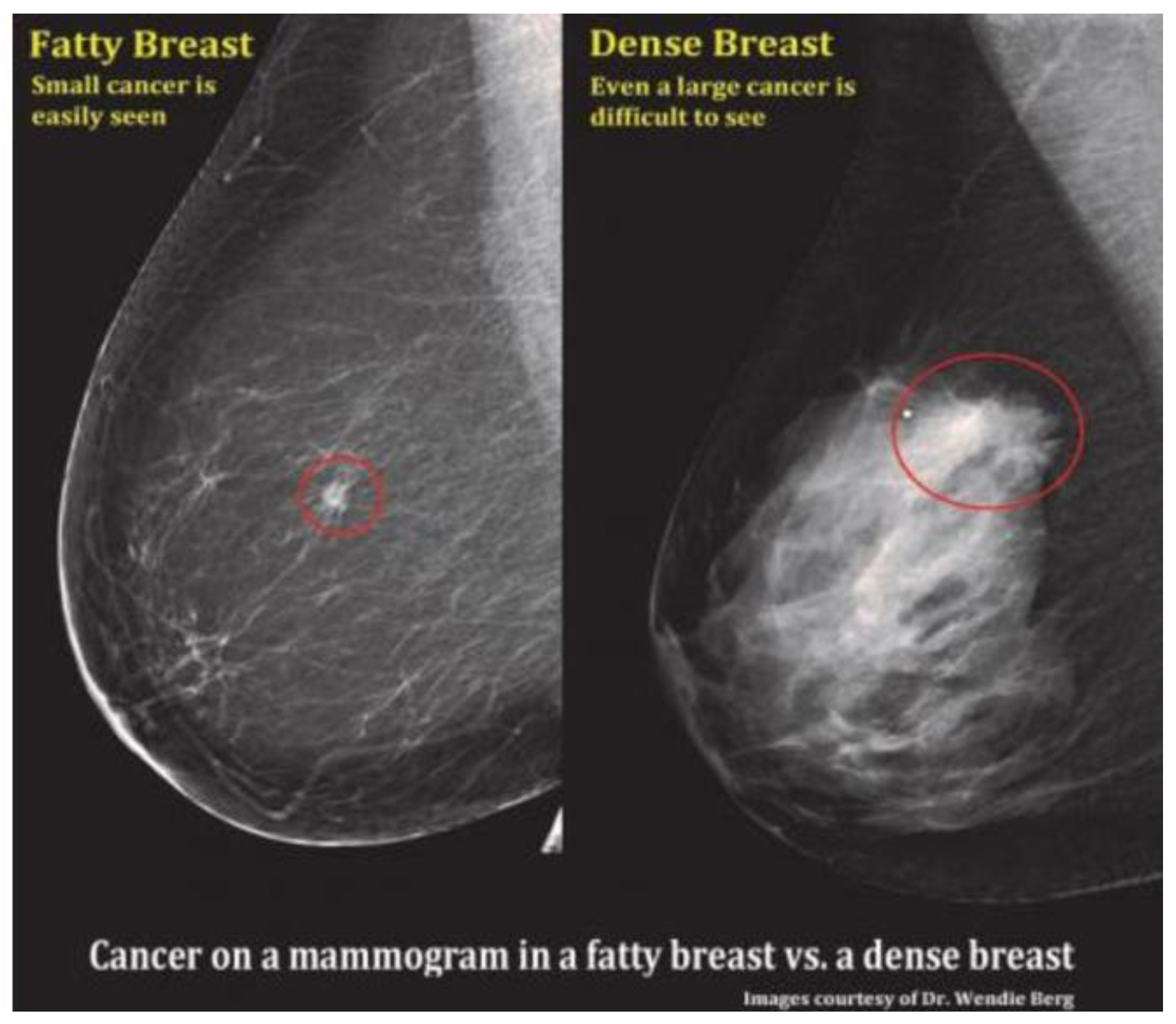

Figure 2 presents a cross-country comparison of breast cancer incidence and mortality rates in the USA, China, and India (per 100,000 population). The USA records the highest incidence at 86.4 new cases per 100,000, while China and India report significantly lower rates at 25 and 13.7 per 100,000, respectively. However, these lower figures should not be interpreted as evidence of a lower disease burden. Instead, they likely reflect systemic challenges in cancer detection and reporting. In both China and India, limited access to screening, underdiagnosis, and insufficient healthcare infrastructure particularly in rural and underserved areas contribute to underreporting of breast cancer cases [

68,

69]. Furthermore, national cancer registries in these countries remain incomplete or in early development stages, and many cases go unrecorded or are diagnosed only at advanced stages [

70]. In India especially, the lack of centralized, up-to-date data makes it difficult to obtain accurate national estimates. Cultural factors such as stigma, low health literacy, and fear of diagnosis also discourage women from seeking early screening or medical advice, further masking the true prevalence of the disease [

71].

1.3. Third Stage-Biopsy

Biopsy is considered the third stage in the process of characterizing breast lesion, typically following initial screening and imaging. Once the second stage of screening is complete, patients often undergo mammography and breast ultrasound to further assess any detected abnormalities. If suspicious features persist, a biopsy is conducted to obtain tissue samples for histopathological analysis, using techniques such as core needle biopsy, vacuum-assisted biopsy, fine needle aspiration, or punch biopsy [

72]. These procedures help confirm malignancy and guide treatment decisions, but many biopsies ultimately prove to be unnecessary. This is especially true in women with dense breast tissue, where false-positive findings range from 73% to 97% [

73,

74,

75].

It is estimated that over 970,000 breast biopsies performed annually in the United States are unwarranted [

76]. These high rates of benign outcomes up to 66.8% in some studies not only increase healthcare costs but also cause significant anxiety, physical discomfort, and reduced willingness to attend future screenings [

73,

77,

78]. Research shows that ultrasound can accurately distinguish between benign and malignant lesions, reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies by 34% to 60% [

79,

80].

2. Problem Statement

Despite advancements in awareness and screening technologies, persistent disparities in early detection, particularly in rural and underserved regions, remain a major barrier to improving outcomes. Conventional methods like mammography, although effective, are often unaffordable, unavailable, or impractical in low-resource settings. Ultrasound, a more accessible alternative, is limited by operator dependence and diagnostic variability. Similarly, clinical breast examinations, though widely promoted in low-income areas, suffer from low sensitivity and inconsistent application.

These challenges underscore the urgent need for cost-effective, portable, and operator-independent screening solutions tailored to diverse healthcare environments. Tactile imaging, a non-invasive technique that quantifies tissue elasticity, shows considerable promise when integrated with ultrasound in a hybrid diagnostic system. This combined approach leverages the strengths of both modalities, TI for objective lesion detection and ultrasound for structural characterization enhancing diagnostic accuracy while reducing false positives and minimizing dependence on specialist interpretation.

Importantly, hybrid systems can offer critical diagnostic parameters often missing in current imaging models, including absolute elasticity of the lesion, precise location within the breast, surrounding tissue characterization, lesion acutance (edge sharpness), and quantification of lesion mobility. This review explores the potential of tactile imaging, particularly in combination with ultrasound, to address these diagnostic gaps. By evaluating its relevance across high-incidence, high-burden countries like the USA, China, and India, this paper highlights how hybrid technologies can support equitable, early detection and ultimately improve global breast cancer outcomes.

3. Introduction of Tactile Imaging

Tactile Imaging (TI) is an evolving medical imaging modality that has shown significant promise in both academic research and clinical applications, particularly in the diagnosis of breast and prostate cancers [

81]. By utilizing arrays of capacitive pressure sensors, TI captures variations in contact stress across soft tissues, enabling the detection and evaluation of abnormal tissue stiffness an established indicator of malignancy [

82,

83]. In breast cancer screening, TI functions by generating real-time, high-resolution maps of mechanical properties such as elasticity, size, and shape, allowing clinicians to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions [

84,

85].Beyond identifying new masses, TI also facilitates longitudinal monitoring of known lesions, providing valuable information on structural changes over time. Its capacity to perform quantitative soft tissue differentiation makes it a compelling, radiation-free alternative or adjunct to traditional imaging methods [

85].

Breast cancer screening practices vary significantly across the United States, China, and India countries with the highest global incidence and mortality rates. Differences in healthcare infrastructure, rural outreach, workforce capacity, and cultural acceptance shape how and when women engage with screening services.

Table 1 presents a comparative summary of these disparities and contextualizes the potential for hybrid TI-US systems to address persistent challenges in access, detection, and diagnostic consistency.

Although Tactile Imaging (TI) is a relatively new entrant in the field of breast cancer diagnostics, emerging clinical evidence has demonstrated its effectiveness in differentiating benign from malignant tissue based on mechanical properties [

86].

3.1. TI VS Other Imaging Modalities

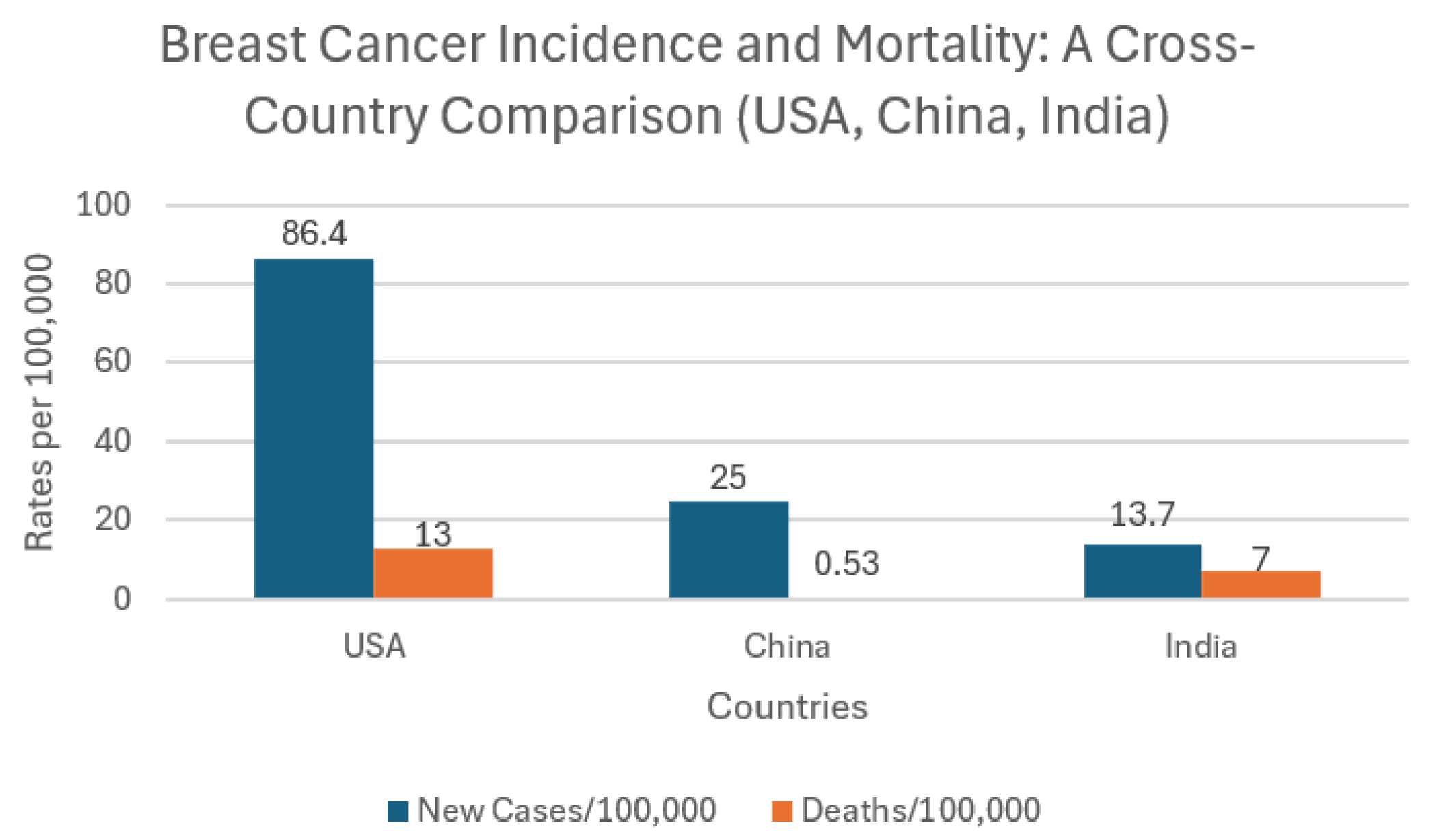

To contextualize TI’s diagnostic value alongside established techniques,

Figure 3 presents a comparative sensitivity versus specificity plot for CBE, MAM, US, MRI, and TI. This visual comparison highlights how TI performs within a similar diagnostic range as current gold-standard technologies. For instance, MAM demonstrates sensitivity values ranging from 64% to 98% [

87,

88] with specificity between 46% and 93% [

60,

89]. depending on factors such as breast density and screening context. MRI offers high sensitivity ranging from 75.2% to 93% [

90,

91] and specificity between 72% and 97% [

90,

91] particularly benefiting high-risk populations. While CBE shows high specificity (93%–98.6%) [

92,

93] its sensitivity remains notably lower (6%–58.8%) [

92,

94] limiting its effectiveness for early detection. TI in contrast, exhibits sensitivity levels between 83% and 91.4% [

95,

96] and specificity ranging from 86% to 94% in most reported studies [

95,

97] positioning it comparably with established imaging methods. Although one study reported a lower specificity of 35% [

96], this appears to be an isolated finding and may reflect variation in protocol, device generation, or operator experience. Importantly, such limitations can be mitigated through multimodal approaches for example, combining TI with ultrasound has the potential to enhance both sensitivity and specificity, compensating for individual weaknesses and improving overall diagnostic accuracy. Given these strengths and its additional advantages such as portability, affordability, and radiation-free operation, TI holds considerable promise as a clinically viable screening tool, particularly in settings with limited access to advanced imaging modalities like MRI and MAM.

3.2. Sensor Technology

While the clinical potential of Tactile Imaging has been increasingly recognized, it is important to note that multiple interpretations and implementations of TI exist [

98,

99,

100]. Though these approaches vary in design and sensor configuration, they all share the fundamental objective of differentiating soft tissues based on mechanical response to applied stress, producing a visual or quantitative ‘hardness map.’ The effectiveness of TI largely depends on the sensing technology used, which governs spatial resolution, sensitivity, and clinical applicability.

Table 2 summarizes the various sensor types currently integrated into TI systems, highlighting their sensitivity, specificity, advantages, and limitations in the context of breast tissue characterization.

Considering the comparative advantages and limitations of the different tactile imaging sensor types, the capacitive sensor emerges as the most practical choice for breast cancer screening applications, particularly in primary care settings. Despite challenges such as lower spatial resolution and longer scanning durations, its favorable balance of diagnostic performance, independence from breast density, and operational simplicity make it well-suited for scalable, primary care deployment. Therefore, this paper will focus on the use of capacitive sensor technology for further analysis and application development in breast cancer screening.

3.2. Current Work

Tactile imaging (capacitive sensor) has shown considerable promise in breast cancer diagnostics by differentiating benign from malignant lesions based on mechanical properties. As a non-invasive, radiation-free, and cost-effective modality, TI offers an appealing alternative to traditional imaging techniques. Recent research using breast phantoms has compared TI with US, demonstrating that while US achieves higher accuracy in lesion sizing, TI provides a faster and more intuitive screening experience with broader field-of-view coverage [

109].

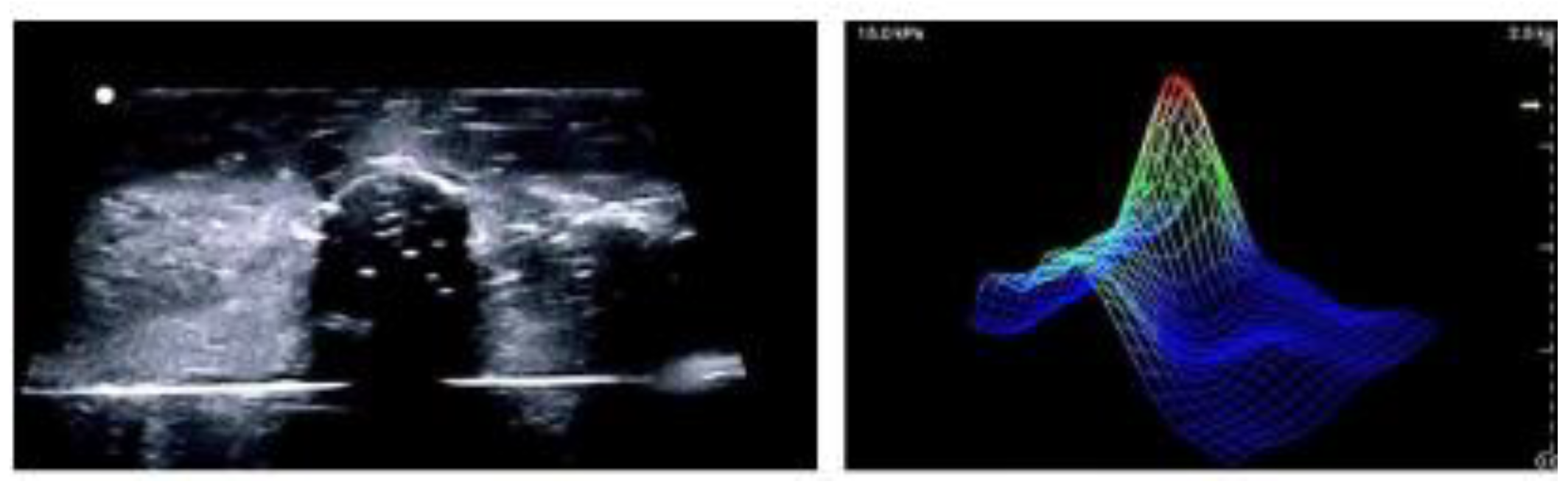

Figure 6 is a visual representation of how ultrasound and tactile imaging provide complementary information with ultrasound showing anatomical structure and tactile imaging representing tissue stiffness or elasticity. Ongoing clinical trials are assessing TI against clinical breast examinations to evaluate its diagnostic utility in real-world symptomatic populations [

59].

Beyond breast applications, TI has been successfully implemented in prostate cancer screening. The Prostate Mechanical Imaging system allows clinicians to detect nodules and structural irregularities using mechanical feedback, enhancing the sensitivity of digital rectal exams [

110].

In pelvic floor diagnostics, TI has progressed significantly with the development of hybrid tactile–ultrasound fusion systems. A notable integrated 96 tactile and 192 ultrasound transducers to simultaneously capture surface pressure distributions and sub-surface anatomical structures. This system enables the generation of real-time stress–strain maps during various functional maneuvers, including valsalva, voluntary muscle contraction, and relaxation. The fusion of tactile and ultrasound modalities allows clinicians to correlate mechanical responses with anatomical landmarks, improving localization of functional deficits and enabling objective pre- and post-treatment comparisons. Additionally, this hybrid approach minimizes inter-observer variability and supports quantitative tracking of biomechanical changes over time, which is particularly useful for monitoring rehabilitation or surgical outcomes [

111].

Building on this concept, this current research applies a similar fusion strategy to the breast. By integrating tactile imaging with ultrasonography, the aim is to simultaneously capture mechanical and anatomical data mirroring the functional assessment framework used in pelvic floor imaging. This hybrid approach is designed to enhance lesion detection and enable differentiation between benign and malignant masses, while also supporting longitudinal monitoring of breast tissue abnormalities.

3.3. Future Work

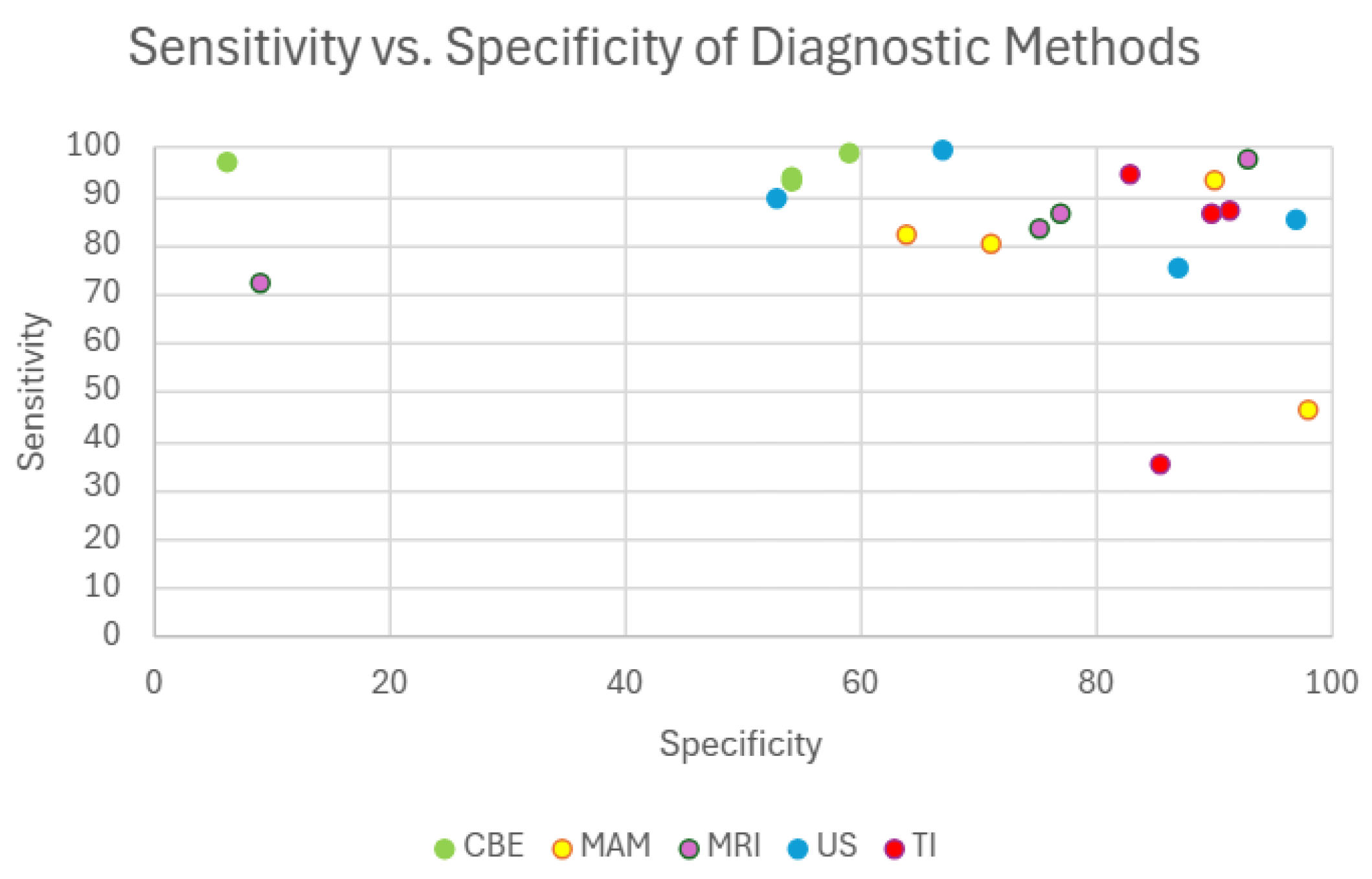

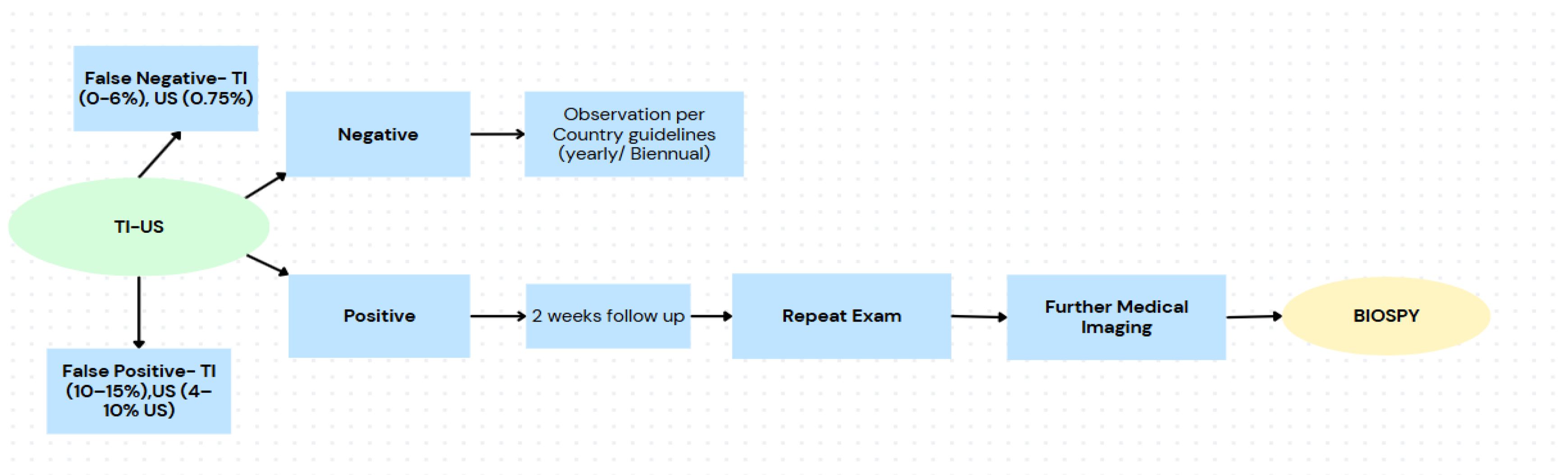

Current breast cancer diagnostic workflows typically beginning with CBE followed by screening MAM are prone to significant inefficiencies. Screening MAM alone can yield FN rates as high as 43.6% [

28], and FP rates ranging from 10% to 60% [

28,

29] leading to delayed diagnoses, overuse of diagnostic resources, and unnecessary biopsies [

30]. Participation in diagnostic follow-up imaging is variable, and in many cases, over 99% of biopsies yield benign results [

90], with only 0.5% confirming malignancy.

Figure 4.

Flowchart illustrating current breast cancer screening pathways in the USA, China, and India, highlighting challenges with participation rates, false positive and negative rates, and the high rates of unnecessary biopsy referrals.

Figure 4.

Flowchart illustrating current breast cancer screening pathways in the USA, China, and India, highlighting challenges with participation rates, false positive and negative rates, and the high rates of unnecessary biopsy referrals.

To address these issues, we propose a restructured diagnostic pathway incorporating TI and US at the primary care level. This model enables objective, real-time mechanical and anatomical assessments at the first point of contact. When combined, TI and US have demonstrated the ability to reduce FN rates to as low as 0–6% [

112], and FP rates by 10–15%, offering immediate diagnostic confidence [

113]. Notably, TI alone has shown a 23% reduction in benign biopsy rates with no missed cancers, and up to 50% reduction with only a 4.6% miss rate [

85]. Furthermore, TI has achieved 91.4% sensitivity and 86.8% specificity for binary lesion classification [

97], metrics that are further enhanced when combined with machine learning algorithms trained on large, patient-specific datasets pushing diagnostic performance toward 98% sensitivity and 97% specificity [

114,

115,

116,

117].

This hybrid model not only streamlines triage and improves diagnostic accuracy but also reduces pressure on specialized radiology services by allowing primary care providers to rule out benign cases and monitor equivocal findings under country-specific guidelines. A repeat exam within two weeks can serve as a safety net for borderline cases, further improving patient management without increasing risk. As illustrated in

Figure 5, this shift represents a transformative approach to early breast cancer detection particularly in low-resource or high-volume settings where timely access and accuracy are critical.

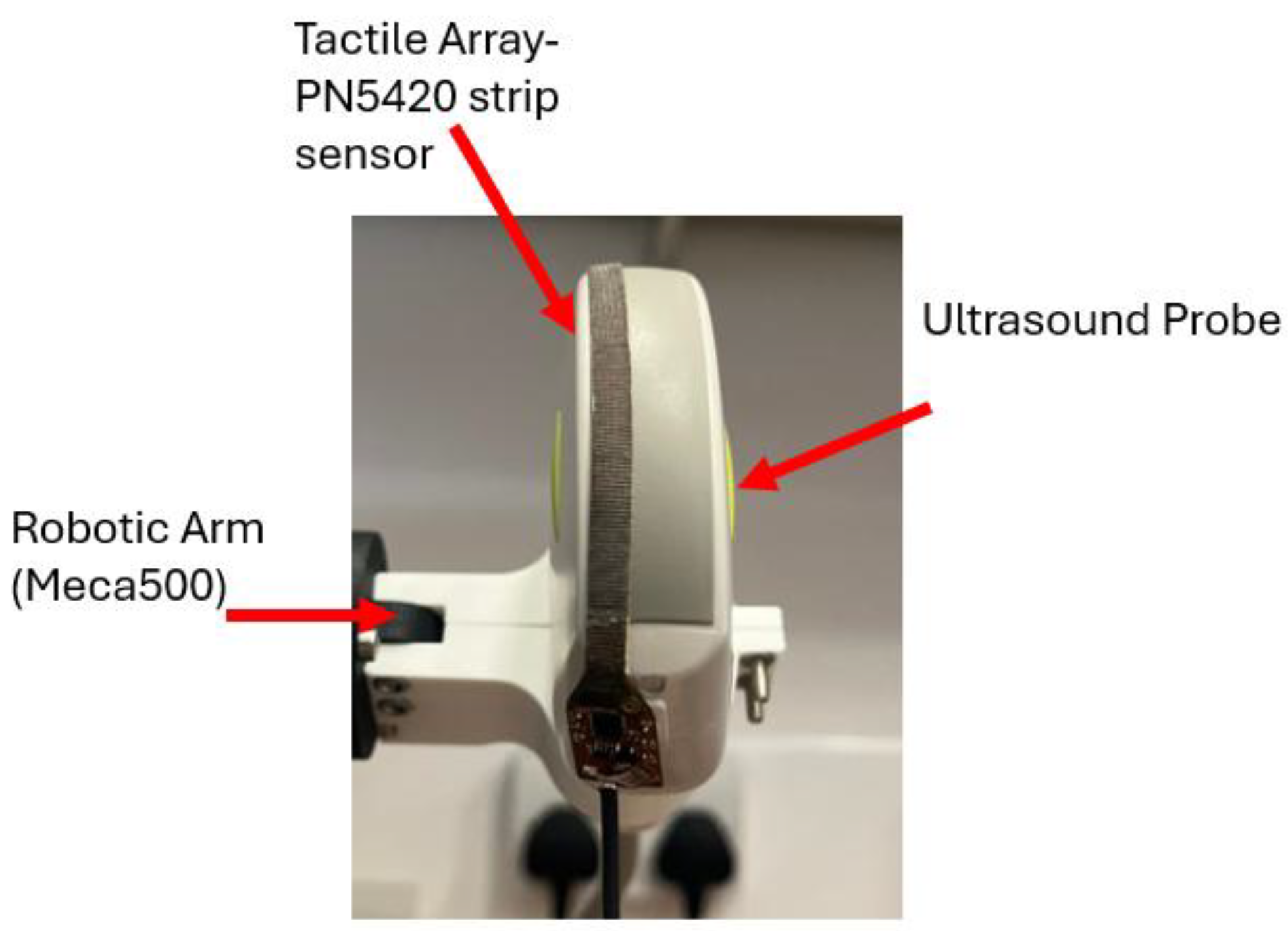

Current experimental efforts are focused on developing a novel hybrid system that combines a capacitive tactile imaging array with an ultrasound probe for enhanced breast cancer screening. This approach is designed to integrate the biomechanical advantages of TI such as tissue elasticity mapping with the anatomical detail provided by ultrasound.

By merging data from both modalities, the system enables comprehensive lesion characterization through 3D ultrasound imaging enhanced with color-coded elasticity maps derived from tactile input. The current prototype is illustrated in

Figure 7, showing the integration of a PN5420 tactile strip sensor onto the surface of a standard ultrasound probe. The system is mounted on a Meca500 robotic arm to maintain consistency across experimental trials.

This dual-modality framework addresses key limitations of each standalone technique, ultrasound’s lack of stress data, and TI’s limited anatomical depth. The findings from this ongoing study demonstrate the feasibility of a fully integrated hybrid device, offering a potential design model for scalable, low-cost, and operator-independent breast cancer screening.

4. Patients’ Outcome

When considering breast cancer screening methods, the patient’s experience is a critical factor especially in primary care settings where comfort, accessibility, and safety drive participation.

Table 3 compares five common screening modalities CBE, MAM, MRI, ultrasound, and tactile imaging, including the hybrid TI–US approach based on attributes that matter most to patients: procedure time, discomfort, risk of overdiagnosis, safety during pregnancy, and wait times for results. While MAM and MRI offer strong clinical accuracy, their high cost, physical discomfort, and limited suitability for younger or pregnant women can discourage participation. In contrast, TI and the TI–US hybrid model offers a more patient-centered approach, with shorter procedures, minimal discomfort, and immediate results supporting more equitable access to early detection, particularly in underserved communities [

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124,

125].

5. Optimizing Screening with TI-US

5.1. Screening Inequities and Accessibility Gaps

In the USA, mammography remains the primary screening tool, with participation rates of up to 75% among insured women aged 50–74 [

5]. However, uninsured or underinsured populations remain underserved due to cost barriers, with supplementary modalities like ultrasound and MRI largely reserved for high-risk groups [

127]. In contrast, China and India face a rural-urban divide where advanced modalities like MAM and US are concentrated in urban areas, while rural populations rely heavily on SBE and CBE, both of which suffer from low sensitivity and operator variability [

113].

Hybrid solution:

TI -US imaging offers a low-cost, portable, and user-friendly alternative to traditional imaging, making it particularly suitable for use in primary care or mobile settings. When paired with ultrasound, this hybrid approach enables both lesion detection (via TI’s measurement of tissue elasticity) and characterization (via US imaging). Together, they can reduce dependence on costly infrastructure and highly trained personnel making early detection more equitable and scalable in underserved areas [

128].

5.2. Operator Dependency and Diagnostic Inconsistencies

Across all three countries, CBE’s subjectivity and low reproducibility limit its utility as a primary screening method [

9,

12]. Ultrasound is a more effective diagnostic tool than clinical breast examination, but its accuracy is highly dependent on operator expertise, posing a significant barrier in settings with limited access to trained professionals. This issue is especially acute in countries like China and India, where widespread shortages of radiologists and sonographers undermine the reliability and consistency of ultrasound-based diagnoses [

129,

130,

131].

Hybrid solution:

TI quantifies tissue stiffness objectively, minimizing the variability seen with manual palpation or image interpretation. Its use of pressure-sensor-based imaging allows repeatable, quantitative assessment of lesions. When integrated with ultrasound, this system offsets user dependency and enhances diagnostic accuracy [

128]. Clinical trials have demonstrated that TI can be nearly three times as accurate as CBE or standalone US in measuring lesion dimensions and identifying malignancies [

132].

5.3. False Positives and Overburdened Follow-up Systems

Mammography in the U.S. has a false-positive rate of 10%, rising even higher in women with dense breast tissue [

6]. MRI, while more sensitive, produces up to 20% false positives [

3]. In China and India, especially in rural areas, limited access to follow-up diagnostics results in both false positives and missed diagnoses, placing additional strain on already stretched healthcare systems [

133].

Hybrid solution:

Tactile imaging has false negative rate of 0-6% [

112], been shown to reduce false-positive rates by 10–15% by distinguishing between soft benign and firm malignant lesions [

113]. This precision is crucial in settings where over-referral is not only expensive but also impractical due to capacity constraints. When combined with US, the hybrid system enhances specificity, helping to avoid unnecessary biopsies and anxiety, while still maintaining high sensitivity [

132].

5.4. Infrastructure and Cost Limitations

Establishing mammography facilities is cost-prohibitive in many regions, and MRI remains out of reach for most low- and middle-income settings [

113]. Even in developed nations like the U.S., the cost of repeated imaging and follow-ups is burdensome without robust insurance coverage [

127].

Hybrid solution:

Both TI and handheld US are portable, relatively low-cost, and suited for deployment in non-traditional clinical settings, including mobile clinics and primary care offices. This combination aligns well with public health strategies aimed at decentralizing care and reaching populations that conventional systems fail to serve. Devices like Baxa a tactile imaging device, demonstrates the feasibility of real-time, office-based screening with immediate results making mass screening more feasible and impactful [

134].

6. Conclusions

Breast cancer continues to pose a significant public health challenge in the USA, China, and India, three countries with the highest global incidence rates. Despite advancements in screening and medical technology, substantial disparities in access to early detection and treatment persist, especially in rural and underserved areas. These gaps are driven by multiple factors, including inadequate healthcare infrastructure, shortages of trained personnel, delayed diagnosis, cultural stigma, and the high cost of care. As a result, many individuals are diagnosed at later stages, when treatment is less effective and survival rates are lower.

This review underscores the pressing need for screening solutions that are not only clinically effective but also accessible, affordable, and scalable. Hybrid diagnostic technologies, specifically the integration of ultrasound and tactile imaging, offer a compelling approach to addressing these challenges. This device is non-invasive, radiation-free, portable, and relatively easy to operate, making it highly suitable for low-resource and remote settings. Tactile imaging complements ultrasound by capturing variations in tissue elasticity and pressure response, allowing for more accurate identification of suspicious lesions.

In countries like China and India, where ultrasound is already widely used as a cost-effective alternative to mammography which remains too expensive and inaccessible for large segments of the population the addition of tactile imaging can significantly elevate diagnostic performance. By enhancing the capabilities of an already accepted and deployed modality, this hybrid approach strengthens the accuracy and reach of breast cancer screening, especially in settings where traditional infrastructure is lacking.

By minimizing dependence on highly specialized equipment and expert radiologists, hybrid devices can streamline the diagnostic pathway, reduce the time between symptom presentation and diagnosis, and increase the efficiency of primary care screening. Their real-time output and ease of use also reduce unnecessary referrals, lower recall rates, and improve the quality of care delivered at the point of first contact.

Incorporating tactile imaging into the initial stage of breast cancer screening, particularly within primary care settings, presents a transformative opportunity. It eliminates the need for immediate referral to advanced imaging centers, which not only reduces healthcare costs but also lessens patient anxiety associated with delayed follow-up. This approach enables health systems to better prioritize resources toward patients who require more intensive evaluation and care.

For high-burden countries like the USA, China, and India, the adoption of hybrid screening tools could significantly improve early detection rates and treatment outcomes. In rural areas, where traditional imaging options are scarce and logistical barriers are high, US and TI provide a comfortable and culturally acceptable alternative that may increase participation in screening programs. Ultimately, widespread implementation of such technology has the potential to reduce incidence-related disparities, save lives, and create a more equitable and effective model for breast cancer care.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBE |

Clinical Breast Exam |

| MAM |

Mammography |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| US |

Ultrasound |

| TI |

Tactile Imaging |

| FN |

False Negative |

| FP |

False Positive |

| PR |

Participation rates |

References

- S. M. Moss, C. Wale, R. Smith, A. Evans, H. Cuckle, and S. W. Duffy, ‘Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality in the UK Age trial at 17 years’ follow-up: a randomised controlled trial’, Lancet Oncol., vol. 16, no. 9, pp. 1123–1132, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. D. Nelson, R. Fu, A. Cantor, M. Pappas, M. Daeges, and L. Humphrey, ‘Effectiveness of Breast Cancer Screening: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis to Update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation’, Ann. Intern. Med., vol. 164, no. 4, p. 244, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- WHO, ‘Breast cancer- World Health Organization’, Mar. 2024. Accessed: Apr. 25, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer.

- Z. Safarpour Lima, M. R. Ebadi, G. Amjad, and L. Younesi, ‘Application of Imaging Technologies in Breast Cancer Detection: A Review Article’, Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 838–848, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Cardoso et al., ‘Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up’, Ann. Oncol., vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 1194–1220, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Verburg et al., ‘Computer-Aided Diagnosis in Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Screening of Women With Extremely Dense Breasts to Reduce False-Positive Diagnoses’, Invest. Radiol., vol. 55, no. 7, pp. 438–444, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Iranmakani et al., ‘A review of various modalities in breast imaging: technical aspects and clinical outcomes’, Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med., vol. 51, no. 1, p. 57, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Huang, L. Chen, J. He, and Q. D. Nguyen, ‘The Efficacy of Clinical Breast Exams and Breast Self-Exams in Detecting Malignancy or Positive Ultrasound Findings’, Cureus, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. McDonald, D. Saslow, and M. H. Alciati, ‘Performance and Reporting of Clinical Breast Examination: A Review of the Literature’, CA. Cancer J. Clin., vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 345–361, Nov. 2004. [CrossRef]

- T. Bryan and E. Snyder, ‘The Clinical Breast Exam: A Skill that Should Not Be Abandoned’, J. Gen. Intern. Med., vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 719–722, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. B. Green and S. H. Taplin, ‘Breast Cancer Screening Controversies’, J. Am. Board Fam. Med., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 233–241, May 2003. [CrossRef]

- T. T. Ngan, N. T. Q. Nguyen, H. Van Minh, M. Donnelly, and C. O’Neill, ‘Effectiveness of clinical breast examination as a “stand-alone” screening modality: an overview of systematic reviews’, BMC Cancer, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 1070, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Karellas and S. Vedantham, ‘Breast cancer imaging: A perspective for the next decade’, Med. Phys., vol. 35, no. 11, pp. 4878–4897, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- P. Zubor et al., ‘Why the Gold Standard Approach by Mammography Demands Extension by Multiomics? Application of Liquid Biopsy miRNA Profiles to Breast Cancer Disease Management’, Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 20, no. 12, p. 2878, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Miller, ‘Breast cancer screening: Can we talk?’, J. Gen. Intern. Med., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 206–207, Mar. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Chetlen, J. Mack, and T. Chan, ‘Breast cancer screening controversies: who, when, why, and how?’, Clin. Imaging, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 279–282, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Abel et al., ‘Detecting Abnormal Axillary Lymph Nodes on Mammograms Using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network’, Diagnostics, vol. 12, no. 6, p. 1347, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. De Jesus et al., ‘The Benefits of Screening Mammography’, Curr. Breast Cancer Rep., vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 103–107, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dibden, J. Offman, S. W. Duffy, and R. Gabe, ‘Worldwide Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies Measuring the Effect of Mammography Screening Programmes on Incidence-Based Breast Cancer Mortality’, Cancers, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 976, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Ma et al., ‘The American Cancer Society 2035 challenge goal on cancer mortality reduction’, CA. Cancer J. Clin., vol. 69, no. 5, pp. 351–362, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. He et al., ‘[China guideline for the screening and early detection of female breast cancer(2021, Beijing)]’, Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 357–382, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P. Tripathi, A. Sahu, and J. Daftary, ‘Breast screening revisited’, J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care, vol. 3, no. 4, p. 340, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Pérez-Solis, G. Maya-Nuñez, P. Casas-González, A. Olivares, and A. Aguilar-Rojas, ‘Effects of the lifestyle habits in breast cancer transcriptional regulation’, Cancer Cell Int., vol. 16, no. 1, p. 7, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Handel, ‘The Effect of Silicone Implants on the Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment of Breast Cancer’:, Plast. Reconstr. Surg., vol. 120, no. Supplement 1, pp. 81S-93S, Dec. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Smilg, ‘Are you dense? The implications and imaging of the dense breast’, South Afr. J. Radiol., vol. 22, no. 2, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. U. Ekpo, M. Alakhras, and P. Brennan, ‘Errors in Mammography Cannot be Solved Through Technology Alone’, Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev., vol. 19, no. 2, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Grimm, C. S. Avery, E. Hendrick, and J. A. Baker, ‘Benefits and Risks of Mammography Screening in Women Ages 40 to 49 Years’, J. Prim. Care Community Health, vol. 13, p. 215013272110583, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Majid, E. S. De Paredes, R. D. Doherty, N. R. Sharma, and X. Salvador, ‘Missed Breast Carcinoma: Pitfalls and Pearls’, RadioGraphics, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 881–895, Jul. 2003. [CrossRef]

- R. Given-Wilson, G. Layer, M. Warren, and J.-C. Gazette, ‘False negative mammography: causes and consequences’, The Breast, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 361–366, Dec. 1997. [CrossRef]

- L. Warren, D. Dance, and K. Young, ‘Radiation risk with digital mammography in breast screening’, GOV.UK. Accessed: Jan. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/breast-screening-radiation-risk-with-digital-mammography/radiation-risk-with-digital-mammography-in-breast-screening.

- R. F. Brem, M. J. Lenihan, J. Lieberman, and J. Torrente, ‘Screening Breast Ultrasound: Past, Present, and Future’, Am. J. Roentgenol., vol. 204, no. 2, pp. 234–240, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Geisel, M. Raghu, and R. Hooley, ‘The Role of Ultrasound in Breast Cancer Screening: The Case for and Against Ultrasound’, Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 25–34, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Houser, D. Barreto, A. Mehta, and R. F. Brem, ‘Current and Future Directions of Breast MRI’, J. Clin. Med., vol. 10, no. 23, p. 5668, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Suneetha Rani, S. J Soujanya, and P. Anjaiah, ‘Breast Cancer Detection Using Combination of Feature Extraction Models’, Int. J. Eng. Technol., vol. 7, no. 3.12, p. 848, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Radhakrishna et al., ‘Role of magnetic resonance imaging in breast cancer management’, South Asian J. Cancer, vol. 07, no. 02, pp. 069–071, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Houser, D. Barreto, A. Mehta, and R. F. Brem, ‘Current and Future Directions of Breast MRI’, J. Clin. Med., vol. 10, no. 23, p. 5668, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I.-W. Pan, K. C. Oeffinger, and Y.-C. T. Shih, ‘Cost-Sharing and Out-of-Pocket Cost for Women Who Received MRI for Breast Cancer Screening’, JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst., vol. 114, no. 2, pp. 254–262, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Saslow et al., ‘American Cancer Society Guidelines for Breast Screening with MRI as an Adjunct to Mammography’, CA. Cancer J. Clin., vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 75–89, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- E. Cha, E. T. Oluyemi, E. B. Ambinder, and K. S. Myers, ‘Clinical Outcomes of Benign Concordant MRI-Guided Breast Biopsies’, Clin. Breast Cancer, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 597–603, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Chakrabarthi et al., ‘Best Practice Guidelines for Breast Imaging, Breast Imaging Society, India: Part-1’, Ann. Natl. Acad. Med. Sci. India, vol. 58, pp. 60–68, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Chakrabarthi et al., ‘Quality Assurance Guidelines for Breast Imaging – Breast Imaging Society, India’, Indian J. Breast Imaging, vol. 1, pp. 48–71, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Guo, G. Lu, B. Qin, and B. Fei, ‘Ultrasound Imaging Technologies for Breast Cancer Detection and Management: A Review’, Ultrasound Med. Biol., vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 37–70, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Buchberger, S. Geiger-Gritsch, R. Knapp, K. Gautsch, and W. Oberaigner, ‘Combined screening with mammography and ultrasound in a population-based screening program’, Eur. J. Radiol., vol. 101, pp. 24–29, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Santos, A. R. Ribeiro, and D. Marques, ‘Ultrasound as a Method for Early Diagnosis of Breast Pathology’, J. Pers. Med., vol. 13, no. 7, p. 1156, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Jacobson et al., ‘Ultrasonography of Superficial Soft-Tissue Masses: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement’, Radiology, vol. 304, no. 1, pp. 18–30, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Shetty, ‘Screening and Diagnosis of Breast Cancer in Low-Resource Countries: What Is State of the Art?’, Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 300–305, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- C.-H. Yip et al., ‘Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: Early detection resource allocation’, Cancer, vol. 113, no. S8, pp. 2244–2256, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, A. Tardivon, L. Ollivier, F. Thibault, C. El Khoury, and S. Neuenschwander, ‘How to optimize breast ultrasound’, Eur. J. Radiol., vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 6–13, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Bae et al., ‘Breast Cancer Detected with Screening US: Reasons for Nondetection at Mammography’, Radiology, vol. 270, no. 2, pp. 369–377, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Nothacker et al., ‘Early detection of breast cancer: benefits and risks of supplemental breast ultrasound in asymptomatic women with mammographically dense breast tissue. A systematic review’, BMC Cancer, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 335, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. M and P. Moorthy, ‘False negativity rate of ultrasonography with mammography in women with palpable breast lumps’, Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci., vol. 11, no. (SPL 4), pp. 1800–1804, Dec. 2020.

- W. A. Berg and A. Vourtsis, ‘Screening Breast Ultrasound Using Handheld or Automated Technique in Women with Dense Breasts’, J. Breast Imaging, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 283–296, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang et al., ‘Evaluating the Accuracy of Breast Cancer and Molecular Subtype Diagnosis by Ultrasound Image Deep Learning Model’, Front. Oncol., vol. 11, p. 623506, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Dang et al., ‘Automated Breast Ultrasound With Remote Reading for Primary Breast Cancer Screening: A Prospective Study Involving 46 Community Health Centers in China’, Am. J. Roentgenol., vol. 224, no. 1, p. e2431830, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang et al., ‘Evaluation of Different Breast Cancer Screening Strategies for High-Risk Women in Beijing, China: A Real-World Population-Based Study’, Front. Oncol., vol. 11, p. 776848, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Catalano et al., ‘Recent Advances in Ultrasound Breast Imaging: From Industry to Clinical Practice’, Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 5, p. 980, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wu, Y. Liu, X. Li, B. Song, C. Ni, and F. Lin, ‘Factors associated with breast cancer screening participation among women in mainland China: a systematic review’, BMJ Open, vol. 9, no. 8, p. e028705, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Bhattacharya, N. Sharma, and A. Singh, ‘Designing culturally acceptable screening for breast cancer through artificial intelligence-two case studies’, J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 760, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Bhattacharya, S. Varshney, P. Heidler, and S. K. Tripathi, ‘Expanding the horizon for breast cancer screening in India through artificial intelligent technologies -A mini-review’, Front. Digit. Health, vol. 4, p. 1082884, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Mehrotra and K. Yadav, ‘Breast cancer in India: Present scenario and the challenges ahead’, World J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 209–218, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Sood et al., ‘Ultrasound for Breast Cancer Detection Globally: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’, J. Glob. Oncol., no. 5, pp. 1–17, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- ‘US population by year, race, age, ethnicity, & more’, USAFacts. Accessed: May 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://usafacts.org/data/topics/people-society/population-and-demographics/our-changing-population/.

- N. Giaquinto et al., ‘Breast Cancer Statistics, 2022’, CA. Cancer J. Clin., vol. 72, no. 6, pp. 524–541, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- ‘STATISTICAL COMMUNIQUÉ OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA ON THE 2022 NATIONAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT’. Accessed: May 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202302/t20230227_1918979.html.

- K. Sun et al., ‘Incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years of female breast cancer in China, 2022’, Chin. Med. J. (Engl.), vol. 137, no. 20, pp. 2429–2436, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ‘India Population 1950-2025 | MacroTrends’. Accessed: May 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/IND/india/population.

- H. Sung et al., ‘Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries’, CA. Cancer J. Clin., vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 209–249, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Sathishkumar, M. Chaturvedi, P. Das, S. Stephen, and P. Mathur, ‘Cancer incidence estimates for 2022 & projection for 2025: Result from National Cancer Registry Programme, India’, Indian J. Med. Res., vol. 156, no. 4 & 5, pp. 598–607, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q.-K. Song et al., ‘Breast Cancer Challenges and Screening in China: Lessons From Current Registry Data and Population Screening Studies’, The Oncologist, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 773–779, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Sathishkumar, M. Chaturvedi, P. Das, S. Stephen, and P. Mathur, ‘Cancer incidence estimates for 2022 & projection for 2025: Result from National Cancer Registry Programme, India’, Indian J. Med. Res., vol. 156, no. 4 & 5, pp. 598–607, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Sathishkumar et al., ‘Trends in breast and cervical cancer in India under National Cancer Registry Programme: An Age-Period-Cohort analysis’, Cancer Epidemiol., vol. 74, p. 101982, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- ‘Overview | Early and locally advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE’. Accessed: May 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng101.

- D. L. Weaver et al., ‘Pathologic findings from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: Population-based outcomes in women undergoing biopsy after screening mammography’, Cancer, vol. 106, no. 4, pp. 732–742, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- E. S. McDonald, A. M. McCarthy, A. L. Akhtar, M. B. Synnestvedt, M. Schnall, and E. F. Conant, ‘Baseline Screening Mammography: Performance of Full-Field Digital Mammography Versus Digital Breast Tomosynthesis’, Am. J. Roentgenol., vol. 205, no. 5, pp. 1143–1148, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Gilbert et al., ‘Accuracy of Digital Breast Tomosynthesis for Depicting Breast Cancer Subgroups in a UK Retrospective Reading Study (TOMMY Trial)’, Radiology, vol. 277, no. 3, pp. 697–706, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Brentnall, J. Cuzick, D. S. M. Buist, and E. J. A. Bowles, ‘Long-term Accuracy of Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Combining Classic Risk Factors and Breast Density’, JAMA Oncol., vol. 4, no. 9, p. e180174, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Zappa, G. Spagnolo, S. Ciatto, D. Giorgi, E. Paci, and M. R. Del Turco, ‘Measurement of the Costs in Two Mammographic Screening Programmes in the Province of Florence, Italy’, J. Med. Screen., vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 191–194, Dec. 1995. [CrossRef]

- N. T. Brewer, T. Salz, and S. E. Lillie, ‘Systematic Review: The Long-Term Effects of False-Positive Mammograms’, Ann. Intern. Med., vol. 146, no. 7, pp. 502–510, Apr. 2007. [CrossRef]

- E. Tohno, T. Umemoto, K. Sasaki, I. Morishima, and E. Ueno, ‘Effect of adding screening ultrasonography to screening mammography on patient recall and cancer detection rates: A retrospective study in Japan’, Eur. J. Radiol., vol. 82, no. 8, pp. 1227–1230, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. Stavros, D. Thickman, C. L. Rapp, M. A. Dennis, S. H. Parker, and G. A. Sisney, ‘Solid breast nodules: use of sonography to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions.’, Radiology, vol. 196, no. 1, pp. 123–134, Jul. 1995. [CrossRef]

- R. Hampson, G. West, and G. Dobie, ‘Tactile, Orientation, and Optical Sensor Fusion for Tactile Breast Image Mosaicking’, IEEE Sens. J., vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 5315–5324, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Yang, Y. Xu, Y. Zhao, J. Yin, Z. Chen, and P. Huang, ‘The role of tissue elasticity in the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant breast lesions using shear wave elastography’, BMC Cancer, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 930, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Guray and A. A. Sahin, ‘Benign Breast Diseases: Classification, Diagnosis, and Management’, The Oncologist, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 435–449, May 2006. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Wellman, ‘Tactile Imaging of Breast Masses: First Clinical Report’, Arch. Surg., vol. 136, no. 2, p. 204, Feb. 2001. [CrossRef]

- V. Egorov et al., ‘Differentiation of benign and malignant breast lesions by mechanical imaging’, Breast Cancer Res. Treat., vol. 118, no. 1, pp. 67–80, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. Hampson, R. G. Anderson, and G. Dobie, Tactile imaging : the requirements to transition from screening to diagnosis of breast cancer - a concise review of current capabilities and strategic direction. University of Strathclyde, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. L. Humphrey, M. Helfand, B. K. S. Chan, and S. H. Woolf, ‘Breast Cancer Screening: A Summary of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’, Ann. Intern. Med., vol. 137, no. 5_Part_1, pp. 347–360, Sep. 2002. [CrossRef]

- N. Aristokli, I. Polycarpou, S. C. Themistocleous, D. Sophocleous, and I. Mamais, ‘Comparison of the diagnostic performance of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), ultrasound and mammography for detection of breast cancer based on tumor type, breast density and patient’s history: A review’, Radiography, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 848–856, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Fitzjohn, C. Zhou, and J. G. Chase, ‘Critical Assessment of Mammography Accuracy’, IFAC-Pap., vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 5620–5625, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Comstock et al., ‘Comparison of Abbreviated Breast MRI vs Digital Breast Tomosynthesis for Breast Cancer Detection Among Women With Dense Breasts Undergoing Screening’, JAMA, vol. 323, no. 8, p. 746, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Mann, C. K. Kuhl, and L. Moy, ‘Contrast-enhanced MRI for breast cancer screening’, J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 377–390, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mandrik et al., ‘Systematic reviews as a “lens of evidence”: Determinants of benefits and harms of breast cancer screening’, Int. J. Cancer, vol. 145, no. 4, pp. 994–1006, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. C. Wishart, J. Warwick, V. Pitsinis, S. Duffy, and P. D. Britton, ‘Measuring performance in clinical breast examination’, Br. J. Surg., vol. 97, no. 8, pp. 1246–1252, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. Hamashima et al., ‘The Japanese Guidelines for Breast Cancer Screening’, Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 46, no. 5, pp. 482–492, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Kearney, S. Airapetian, and A. Sarvazyan, ‘Tactile breast imaging to increase the sensitivity of breast examination’, J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 22, no. 14_suppl, pp. 1037–1037, Jul. 2004. [CrossRef]

- M.-K. Tasoulis, K. E. Zacharioudakis, N. G. Dimopoulos, and D. J. Hadjiminas, ‘Diagnostic accuracy of tactile imaging in selecting patients with palpable breast abnormalities: a prospective comparative study’, Breast Cancer Res. Treat., vol. 147, no. 3, pp. 589–598, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. Egorov et al., ‘Differentiation of benign and malignant breast lesions by mechanical imaging’, Breast Cancer Res. Treat., vol. 118, no. 1, pp. 67–80, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Sahu et al., ‘Characterization of Mammary Tumors Using Noninvasive Tactile and Hyperspectral Sensors’, IEEE Sens. J., vol. 14, no. 10, pp. 3337–3344, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. W. Sanderson et al., ‘Camera-based optical palpation’, Sci. Rep., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 15951, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C.-H. Won, J.-H. Lee, and F. Saleheen, ‘Tactile Sensing Systems for Tumor Characterization: A Review’, IEEE Sens. J., vol. 21, no. 11, pp. 12578–12588, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Aboughaleb, M. H. Aref, and Y. H. El-Sharkawy, ‘Hyperspectral imaging for diagnosis and detection of ex-vivo breast cancer’, Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther., vol. 31, p. 101922, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Wellman, ‘Tactile Imaging of Breast Masses: First Clinical Report’, Arch. Surg., vol. 136, no. 2, p. 204, Feb. 2001. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Wellman and R. D. Howe, ‘Extracting Features from Tactile Maps’, in Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI’99, vol. 1679, C. Taylor and A. Colchester, Eds., in Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 1679. , Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1999, pp. 1133–1142. [CrossRef]

- F. Bhimani et al., ‘Can the Clinical Utility of iBreastExam, a Novel Device, Aid in Optimizing Breast Cancer Diagnosis? A Systematic Review’, JCO Glob. Oncol., no. 9, p. e2300149, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, Y. Chung, A. D. Brooks, W.-H. Shih, and W. Y. Shih, ‘Development of array piezoelectric fingers towards in vivo breast tumor detection’, Rev. Sci. Instrum., vol. 87, no. 12, p. 124301, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Ayyildiz, B. Guclu, M. Zahid Yildiz, and C. Basdogan, ‘An Optoelectromechanical Tactile Sensor for Detection of Breast Lumps’, IEEE Trans. Haptics, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 145–155, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, C. Gifford-Hollingsworth, R. Sensenig, W.-H. Shih, W. Y. Shih, and A. D. Brooks, ‘Breast Tumor Detection Using Piezoelectric Fingers: First Clinical Report’, J. Am. Coll. Surg., vol. 216, no. 6, pp. 1168–1173, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, C. Gifford-Hollingsworth, R. Sensenig, W.-H. Shih, W. Y. Shih, and A. D. Brooks, ‘Breast Tumor Detection Using Piezoelectric Fingers: First Clinical Report’, J. Am. Coll. Surg., vol. 216, no. 6, pp. 1168–1173, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- N. Salhi, ‘Direct Comparison of Ultrasound and Tactile Imaging in Measuring Lesion Diameter in Breast Phantoms’, presented at the 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC, Orlando, FL: IEEE, 2024.

- ‘A new 3D imaging technique for prostate examination’, Nat. Clin. Pract. Urol., vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 291–292, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

- V. Egorov, H. van Raalte, and S. A. Shobeiri, ‘Tactile and Ultrasound Image Fusion for Functional Assessment of the Female Pelvic Floor’, Open J. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 11, no. 06, pp. 674–688, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Medical Tactile Inc, ‘Frequently Asked Questions- Suretouch Breast Exam’. [Online]. Available: https://suretouch.squarespace.com/s/SureTouch_FAQ.pdf.

- Monica and R. Mishra, ‘An epidemiological study of cervical and breast screening in India: district-level analysis’, BMC Womens Health, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 225, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Akay, ‘Support vector machines combined with feature selection for breast cancer diagnosis’, Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 3240–3247, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj and A. Tiwari, ‘Breast cancer diagnosis using Genetically Optimized Neural Network model’, Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 42, no. 10, pp. 4611–4620, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Verma, P. McLeod, and A. Klevansky, ‘Classification of benign and malignant patterns in digital mammograms for the diagnosis of breast cancer’, Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 3344–3351, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S. W. Yoon, and S. S. Lam, ‘Breast cancer diagnosis based on feature extraction using a hybrid of K-means and support vector machine algorithms’, Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 1476–1482, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Canelo-Aybar et al., ‘Benefits and harms of annual, biennial, or triennial breast cancer mammography screening for women at average risk of breast cancer: a systematic review for the European Commission Initiative on Breast Cancer (ECIBC)’, Br. J. Cancer, vol. 126, no. 4, pp. 673–688, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Huang, L. Chen, J. He, and Q. D. Nguyen, ‘The Efficacy of Clinical Breast Exams and Breast Self-Exams in Detecting Malignancy or Positive Ultrasound Findings’, Cureus, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- ‘Getting a Mammogram’, Susan G. Komen®. Accessed: Jun. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.komen.org/breast-cancer/screening/mammography/getting-a-mammogram/.

- R. Vashi, R. Hooley, R. Butler, J. Geisel, and L. Philpotts, ‘Breast Imaging of the Pregnant and Lactating Patient: Imaging Modalities and Pregnancy-Associated Breast Cancer’, Am. J. Roentgenol., vol. 200, no. 2, pp. 321–328, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Sardanelli, V. Magni, G. Rossini, F. Kilburn-Toppin, N. A. Healy, and F. J. Gilbert, ‘The paradox of MRI for breast cancer screening: high-risk and dense breasts—available evidence and current practice’, Insights Imaging, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 96, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. W. Webb, H. S. Thomsen, S. K. Morcos, and Members of Contrast Media Safety Committee of European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR), ‘The use of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media during pregnancy and lactation’, Eur. Radiol., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 1234–1240, Jun. 2005. [CrossRef]

- G. Gardos and J. O. Cole, ‘Maintenance antipsychotic therapy: is the cure worse than the disease?’, Am. J. Psychiatry, vol. 133, no. 1, pp. 32–36, Jan. 1976. [CrossRef]

- H. Madjar, ‘Role of Breast Ultrasound for the Detection and Differentiation of Breast Lesions’, Breast Care Basel Switz., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 109–114, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Sure, ‘Bexa | Our technology’, Bexa. Accessed: Mar. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.mybexa.com/en/technology/.

- N. Amornsiripanitch, S. Ameri, and R. Goldberg, ‘Primary Care Providers Underutilize Breast Screening MRI for High-Risk Women’, Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol., vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 489–494, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Salhi, R. Hampson, A. Lawley, and G. Dobie, ‘Direct Comparison of Ultrasound and Tactile Imaging in Measuring Lesion Diameter in Breast Phantoms’, in 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA: IEEE, Jul. 2024, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri and F. Marmé, ‘Current and emerging treatment approaches for hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer’, Cancer Treat. Rev., vol. 123, p. 102670, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Mao et al., ‘Breast Cancer Incidence After a False-Positive Mammography Result’, JAMA Oncol., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 63, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Xia et al., ‘Cancer screening in China: a steep road from evidence to implementation’, Lancet Public Health, vol. 8, no. 12, pp. e996–e1005, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Wellman, R. D. Howe, N. Dewagan, M. A. Cundari, E. Dalton, and K. A. Kern, ‘Tactile imaging: a method for documenting breast masses’, in Proceedings of the First Joint BMES/EMBS Conference. 1999 IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 21st Annual Conference and the 1999 Annual Fall Meeting of the Biomedical Engineering Society (Cat. No.99CH37015), Atlanta, GA, USA: IEEE, 1999, p. 1131. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Gopika, P. R. Prabhu, and J. V. Thulaseedharan, ‘Status of cancer screening in India: An alarm signal from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5)’, J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care, vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 7303–7307, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sarvazyan and V. Egorov, ‘Mechanical Imaging - a Technology for 3-D Visualization and Characterization of Soft Tissue Abnormalities. A Review’, Curr. Med. Imaging Rev., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 64–73, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Mammographic comparison of dense vs. fatty breast tissue highlighting how increased density can mask potential cancers. In such cases, ultrasound may aid in detection [

34].

Figure 1.

Mammographic comparison of dense vs. fatty breast tissue highlighting how increased density can mask potential cancers. In such cases, ultrasound may aid in detection [

34].

Figure 2.

Breast cancer incidence and mortality rates per 100,000 population for women and men in the USA (333 million) [

62,

63], China (1.426 billion) [

64,

65], and India (1.4 billion) [

66,

67] in 2022.

Figure 2.

Breast cancer incidence and mortality rates per 100,000 population for women and men in the USA (333 million) [

62,

63], China (1.426 billion) [

64,

65], and India (1.4 billion) [

66,

67] in 2022.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity vs. Specificity of CBE, MAM, US, MRI, and TI. TI performs comparably to standard methods and offers a low-cost, radiation-free alternative.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity vs. Specificity of CBE, MAM, US, MRI, and TI. TI performs comparably to standard methods and offers a low-cost, radiation-free alternative.

Figure 6.

Ultrasound image (left) and Tactile Imaging output (right) of a breast phantom, illustrating complementary structure and biomechanical data[

109].

Figure 6.

Ultrasound image (left) and Tactile Imaging output (right) of a breast phantom, illustrating complementary structure and biomechanical data[

109].

Figure 5.

Proposed screening pathway using hybrid TI–US, showing false negative and false positive rates, follow-up steps for positive findings, and observation guidelines for negative findings, leading to biopsy only when necessary.

Figure 5.

Proposed screening pathway using hybrid TI–US, showing false negative and false positive rates, follow-up steps for positive findings, and observation guidelines for negative findings, leading to biopsy only when necessary.

Figure 7.

A hybrid diagnostic device integrating ultrasound and tactile imaging, mounted on a robotic arm for precise, operator-independent breast examination.

Figure 7.

A hybrid diagnostic device integrating ultrasound and tactile imaging, mounted on a robotic arm for precise, operator-independent breast examination.

Table 1.

Comparison of breast cancer screening modalities, participation, and system-level challenges across the USA, China, and India. Highlights disparities in access, detection, and workforce availability. Also outlines the potential of TI + US hybrid technology.

Table 1.

Comparison of breast cancer screening modalities, participation, and system-level challenges across the USA, China, and India. Highlights disparities in access, detection, and workforce availability. Also outlines the potential of TI + US hybrid technology.

| Category |

USA |

China |

India |

| Primary Screening |

MAM, US, MRI, CBE |

SBE, CBE (rural); MAM, US (urban) |

SBE, CBE (rural); MAM, US (urban) |

| Participation |

MAM 75% (50–74y), US 12%, MRI 8% |

Urban MAM/US 70%; Rural SBE 65%, MAM/US 30% |

Urban MAM/US 60%; Rural SBE/CBE 25% |

| Referral post-CBE |

15–20% |

Urban 15%, Rural 10% |

Urban 15–20%, Rural 8% |

| Detection Rate |

MAM 60%, US +0.25%, MRI ~1% |

CBE: 0.4% malignant (urban) |

Like China; lower rural detection |

| False Positives |

MAM 10%, US 8%, MRI 20% |

MAM 12%, US 8%, CBE 5% |

Like China; rural underdiagnosis |

| Access Challenges |

Lower access for uninsured |

Rural infrastructure gaps |

Rural-urban access divide |

| Personnel Shortage |

Moderate; rural gaps |

Severe in rural areas |

High shortage, esp. rural |

| Hybrid TI-US |

Improves detection, lowers FP 0–15% |

Useful for mobile rural outreach |

Expands rural screening, lowers FP |

Table 2.

Comparison of tactile imaging sensor types for breast cancer screening. Includes technology features, diagnostic accuracy, end users, and application domains. Highlights trade-offs in performance, usability, and suitability for low-resource settings.

Table 2.

Comparison of tactile imaging sensor types for breast cancer screening. Includes technology features, diagnostic accuracy, end users, and application domains. Highlights trade-offs in performance, usability, and suitability for low-resource settings.

| Sensor Type |

System Details |

Sens |

Spec |

Manufacturers/Developers |

Application Domains |

Disadvantages |

Advantages |

| Hyperspectral TIS [101] |

Hyperspectral imaging detects tissue properties via reflected light spectra. |

95%[101] |

96%[101] |

Emerging startups; academic research labs |

Wound healing, dermatology, breast tissue characterization |

Data-intensive; needs advanced processing. |

Non-invasive, rich data for AI analysis |

| Piezo-resistive Sensor [102] |

16×26 grid (416 sensors) measures surface deformation and stiffness. |

Not data |

Not data |

Assurance Medical Corp. (Hopkinton, MA, USA)[102] |

Breast screening (shape and size) |

Limited data; prototype-stage testing. |

Accuracy reported twice as high as US and CBE [103]. |

| Capacitive sensor [104] |

16×12 (192) sensors cover 40×30 mm area. |

34.3% to 86% [104] |

59% to 94% [104] |

SureTouch (Medical Tactile Inc., USA); iBE (Siemens Medical Solutions, USA). |

Breast cancer screening, elastic modulus mapping |

Ccontact sensitivity; limited resolution for small/deep lesions. [105]. |

Density-independent; portable, low-cost, user-friendly. [105]. |

| Opto-Electro Mechanical Sensor [106] |

10×10 array: ccombines optical and electro-mechanical feedback to detect surface and subsurface stiffness variations. |

90.8% |

89.8% |

Prototype systems under development- Research |

Surface and subsurface tissue analysis for breast |

Low detection of intermediate lesions; limited 2.8 mm spatial resolution (pin spacing). |

High sensitivity |

| Piezoelectric finger PEF |

PEF 4×1 array: Piezoelectric PZT sensors on steel measure tissue elastic modulus. [107] |

87%-100% [108] |

59% to 94% [104] |

Prototype systems under development- Research |

Breast cancer screening, elastic modulus mapping |

Long scanning time (30 min/quadrant); low spatial resolution [107]. |

Radiation- free, portable, low-cost, user-friendly[105]. |

Table 3.

Comparison of breast cancer screening modalities across key clinical and practical parameters, including procedure time, discomfort, overdiagnosis risk, and patient suitability. Hybrid TI-US offers a favorable balance of speed, comfort, and safety, making it ideal for use in primary care and low-resource settings.

Table 3.

Comparison of breast cancer screening modalities across key clinical and practical parameters, including procedure time, discomfort, overdiagnosis risk, and patient suitability. Hybrid TI-US offers a favorable balance of speed, comfort, and safety, making it ideal for use in primary care and low-resource settings.

| Metric |

CBE |

MAM |

MRI |

US |

TI [126] |

TI and US |

| Procedure Duration |

15 mins |

30 minutes |

20-60 minutes |

15-30 mins |

15 mins |

30 minutes |

| Discomfort Level / Pain Score |

Low |

High (due to breast compression) |

Moderate (contrast injection + long lying time) |

Low |

Low |

low |

| Risk of Overdiagnosis / Overtreatment |

lack of research |

17-23% [118] |

Up to 30% [122] |

Follow up diagnostic tool [125] |

0-6% [112], |

0-6% [112], 10–15% [113] |

| Patient Compliance / Participation Rate |

High |

Variable, lower in younger women |

Lower due to cost and complexity |

High, especially in dense breasts |

Extensive trials are needed |

High, especially in LMICs |

| Suitability During Pregnancy / for Younger Women |

Suitable |

Sensitivity is reduced [121] |

Based on risk/benefit [124] Not recommended [123] |

Safe in pregnancy and for younger women |

Suitable for Dense breast |

Highly Suitable (no radiation, safe for all ages) |

| Results |

Referral often needed post-exam. [119]. |

2 weeks [120] |

2 weeks |

1 week |

Immediate |

Immediate |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).