1. Introduction

The volume of peer-reviewed literature and other technical documentation over the previous two-to-three decades proposing various quality metrics for data testifies to the elusiveness of convergence towards an all-embracing data-quality (DQ) solution. Not only do the different domains of business, environment, health, big data, etc. approach data quality with a different set of perspectives but data can be described on a wide spectrum from atomic data elements to very large, distributed databases. Moreover, the needs of different data applications using the same sets of data may widely differ in terms of the importance of specific quality dimensions.

Whereas convergence has generally been achieved for structured data on the more intrinsic DQ dimensions [

1,

2], agreement on an overall DQ framework has been more problematic. Two comprehensive and relatively recent reviews [

3,

4] acknowledged the difficulty of finding an over-arching solution and categorise the commonly used frameworks to help researchers identify the most suitable one for their particular data needs. Cichy and Rass [

3] illustrated on a quality wheel the 20 quality dimensions they found common to more than one of the DQ frameworks they reviewed. Haug [

4] noted that data quality is a multidimensional concept that can be considered as a set of DQ dimensions each describing a particular characteristic of data quality, sometimes grouped under DQ categories. Haug presented his analysis in terms of DQ classifications.

1.1. Major Issues Encountered in the DQ Frameworks Reviewed

Although the reviews had different points of focus and different aims, their findings are closely aligned in relation to the major issues encountered in the DQ frameworks analysed, namely:

Data quality is a multidimensional concept but there is little agreement on the DQ dimensions it should comprise. Most DQ classifications are ad hoc and incomplete;

DQ dimensions are in general highly context dependent and vary with the type of categorisation under consideration (such as access to data or data interpretability). In addition, DQ dimensions are dependent upon the nature of the data entity (e.g. data item, data field, data record, dataset, database, database collection, etc.) for which a DQ dimension such as completeness may be specified in different terms;

DQ frameworks differ widely in the number of DQ dimensions they define (ranging from two to thirty). For structured data, commonly agreed DQ dimensions are completeness, accuracy, and timeliness, followed by consistency and accessibility. The relevance of all these dimensions and the exact meaning are however dependent on the nature of the data entity. Moreover, structured data and unstructured data may require quite different DQ dimensions (interpretability and conciseness, for example, are more relevant for unstructured data);

DQ dimensions can have objective and subjective measures or a mix of both. Both measures have their uses; some dimensions are either difficult to score quantitatively or can only be done so in specific data-application terms (in particular for relevance- or presentational-type dimensions). The rigour of a measure (fitness-for-use) is also data-application specific;

Whereas DQ frameworks represent different areas of application, widely different frameworks can be used within the same application area;

DQ dimensions often overlap and do not have consistent interpretations resulting in lack of clarity of how to map or measure quality dimensions in practical implementations. Moreover, the processes for assessing data quality differ significantly depending on the mix of subjective/objective measures, the level of data granularity, and the nature of the data (whether primary or derived);

Ensuring orthogonality of selected dimensions is important to avoid these overlapping meanings and to ensure distinguishability.

1.2. The DQ Frameworks Reviewed

The frameworks reviewed by Cichy and Rass [

3] included: AIM quality (AIMQ) [

5], comprehensive methodology for data quality management (CDQ) [

6], cost-effect of low data quality (COLDQ) [

7], data quality assessment (DQA) [

8], data quality assessment framework (DQAF) [

9], a data quality practical approach [

10], data quality methodology for heterogeneous data (HDQM) [

11], hybrid information quality management (HIQM) [

12], observe-orient-decide-act methodology for data quality (OODA DQ) [

13], task-based data quality method (TBDQ) [

14], total data quality management (TDQM) [

15], and total information quality management (TIQM) [

16]. Three of these (TDQM, DQA, and AIMQ) were also reviewed by Haug [

4] as well as a number of other schema including novel combinations of DQ dimensions.

In developing new DQ frameworks, Haug made several recommendations that included clarifying the focus of application; establishing the relevant DQ dimensions within distinguishable categories; specifying the evaluation perspectives; making explicit the data entities and data structure; and clearly defining the dimensions, especially with consideration to existing definitions.

A review of DQ frameworks related specifically to health data for secondary use [

17] corroborated the agreement on the commonly agreed dimensions but extended the list to include uniqueness, representativeness, and contextualisation whilst underlining the lack of consensus on the specific terminology and definitions of the terms. The authors recommended that future research should shift its focus toward defining and developing specific DQ requirements tailored to each use case rather than pursuing an elusive quest for a rigid framework defined by a fixed number of dimensions and precise definitions. They highlighted the need to complete the collection of aspects within each quality dimension and elaborated a full set of assessment methods.

A further review compared different data quality frameworks underpinned by regulatory, statutory, or governmental standards and regulations in various domains [

18]. The frameworks reviewed included: TDQM [

15], ISO 8000 [

19], ISO 25012 [

2], fair information practice principles (FIPPS) [

20], quality assurance framework of the European statistical system (ESS QAF) [

21], the UK government data quality framework [

22], data management body of knowledge (DAMA DMBoK) [

23]. IMF data quality assessment framework (DQAF) [

24], Basel Committee on banking supervision standard (BCBS 239) [

25], ALCOA+ principles [

26], and WHO data quality assurance (DQA) framework [

27]. This review also highlighted the prominence given to the quality dimensions of accuracy, completeness, consistency, and timeliness but noted the evolution of their meanings across different domains. The authors emphasised the need for newer and more modern quality dimensions to be recognised and integrated into all-purpose DQ frameworks to keep apace with the needs of emerging technologies, such as AI systems based on large language models.

1.3. Generic DQ Model

A generic DQ model has been proposed to encapsulate the different aspects and points of focus of any DQ framework [

28]. The model builds on the ISO 25012 data quality model for software product quality requirements and evaluation (SquaRE) standard [

2] and underlines the need to classify different quality dimensions under separate conceptual categories. The authors illustrate the quality dimensions on a quality wheel, similarly to Cichy and Rass [

3], but categorise them in a hierarchy of three levels, the top two levels of which are described in

Table 1. The third level contains some 240 other terms, incorporating all the terms identified in the other reviews.

The authors consider the categories as context-specific since they include both inherent and system-dependent characteristics. This is an important insight that serves to avoid the attenuation of DQ indices that occurs by combining quality dimensions not directly relevant to each other. For instance, since the DQ dimension “accessibility” has little relevance to “completeness”, it is classified under a different top-level category.

1.4. DQ-Centric View of Data Versus Data-Centric View of Data Quality

In addressing data quality, one can take a primarily data-quality centric view of data, which is the one behind most DQ frameworks (we term these DQ-centric frameworks), or a predominantly data-centric view of data quality in which quality is ascertained from a holistic description of the data.

Arguably, the most fundamental requirement for ascertaining data quality is to understand the suitability of using the data for a specific purpose, whether it be for use in a particular application or in the fusion or comparison with other data. Whereas the needs of an application might eventually have an influence on the quality of the data themselves, the actual quality of the data are independent of these needs and should ideally be measured separately from them. Taking a purely DQ-centric view tends to blur the distinction between the intrinsic quality of the data themselves and the data quality needs of the data application. It is one of the reasons why many DQ-centric frameworks introduce quality dimensions related to concepts such as understandability, usefulness, interpretability, and relevance, which are essentially subjective measures of the data user from an application point of view.

In contrast, a data-centric view is less concerned about capturing the data-application needs as it is in sufficiently describing actual data – it is the data (rather than quality) that are considered as the fundamental concept. All that is known about the data can be described with contextual metadata. Such a methodology implies that most of the DQ dimensions captured in the quality wheel of Miller at al [

28], can be attributed to the data’s general contextual elements. Since the context is applied at the data level, this approach automatically leads to a solution scalable to the type/level of data and is precisely the philosophy behind the FAIR data model [

29].

1.5. FAIR Data Principles

FAIR is an acronym describing the four foundational principles of data relating to findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability. DQ-centric frameworks treat these terms as individual quality dimensions at various category hierarchical levels. In the model of [

28], “findability” is classified as a subdivision of the category “accessibility”, and “interoperability” and “reusability” are classified together under the category “usefulness”. In contrast, the FAIR data principles consider data quality as a function of all of the principles rather than their being mere individual quality dimensions per se. Moreover, although the principles do not explicitly prescribe how quality should be measured, they view quality primarily as a data application concern that can be addressed from the complementarity of the data’s metadata for determining the suitability of the data for the required needs [

30]. The FAIR data principles therefore remove the focus of data quality from the requirements of any particular data application. Consequently, a set of quality labels need only be attributed once to the data rather than many times for different types of data application. The latter need only be matched with the DQ labels of the data to understand the suitability of the data for the required purpose. This has the further advantage of allowing the data application to specify their own specific minimal information standards (such as minimum information for biological and biomedical investigations – MIBBI, or minimum information about a microarray experiment – MIAME, for biological and biomedical investigations) without their necessarily being an explicit part of the DQ model itself [

30]. Conformance to such specific information standards can be assessed from the general contextual content of the data source.

1.6. Rationale for the Data-Centric Approach

Following this principle and acting on the recommendation of Bian et al [

31] to report data quality into the FAIR data principles, we propose an alternative approach to describe and ascertain data quality. Our motivation for doing this is driven by a practical use-case for determining a quality index of diabetes-related health indicators. Notwithstanding the specific reference to diabetes, the use-case is pertinent to all types of indicators and serves to illustrate the limitations of existing DQ solutions.

The way in which an indicator is derived generally follows an inter-linked chain of data-capture and data-processing steps that together play a critical role in the interpretation and usability of the final indicator. Without knowing the assumptions, limitations, and bias introduced at each stage throughout the data chain, the indicator cannot be used with any degree of certainty. This prompts the need to record such information. Generally, this chaining process will involve most of the individual data entity types referred to by Haug’s data level focus [

4] (c.f. point 2 of the enumerated list provided earlier in the Introduction). Ideally, a DQ paradigm is needed that works across all these data entity types without having to draw on different frameworks. None of the existing individual DQ frameworks support this concept.

2. Materials and Methods

To provide an implementable means of realising the data-centric approach to data quality, we consider the data-contextualisation framework SOLICIT (semantic ontology-labelled indicator contextualisation integrative taxonomy) [

32], which we developed previously for contextualising indicators but which can in fact be used to contextualise any type of data.

2.1. The SOLICIT Data-Contextualisation Framework

SOLICIT is a generic ontology framework based on the common core ontologies (CCO) [

33] and the ISO/IEC 11179 metadata registry standard [

34]. It therefore provides common standard constructs and relationships that can be extended at the domain level at which it is implemented. SOLICIT uses the terminology of ISO/IEC 11179 for a data element, described as a “unit of data that is considered in context to be indivisible”, where context is defined as “the circumstance, purpose and perspective under which an object is defined or used”). Such a definition allows a data element to take many different forms dependent upon the context in which it is used. It therefore equates to the term “data entity” used elsewhere in the text.

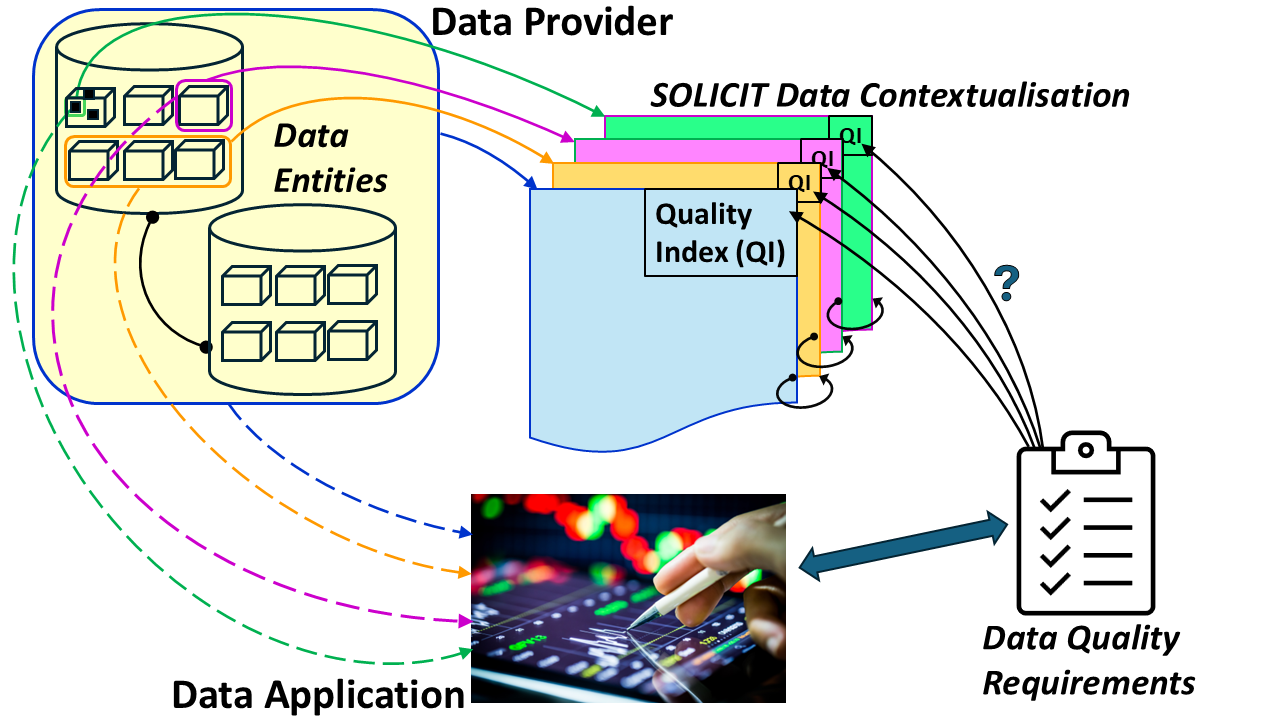

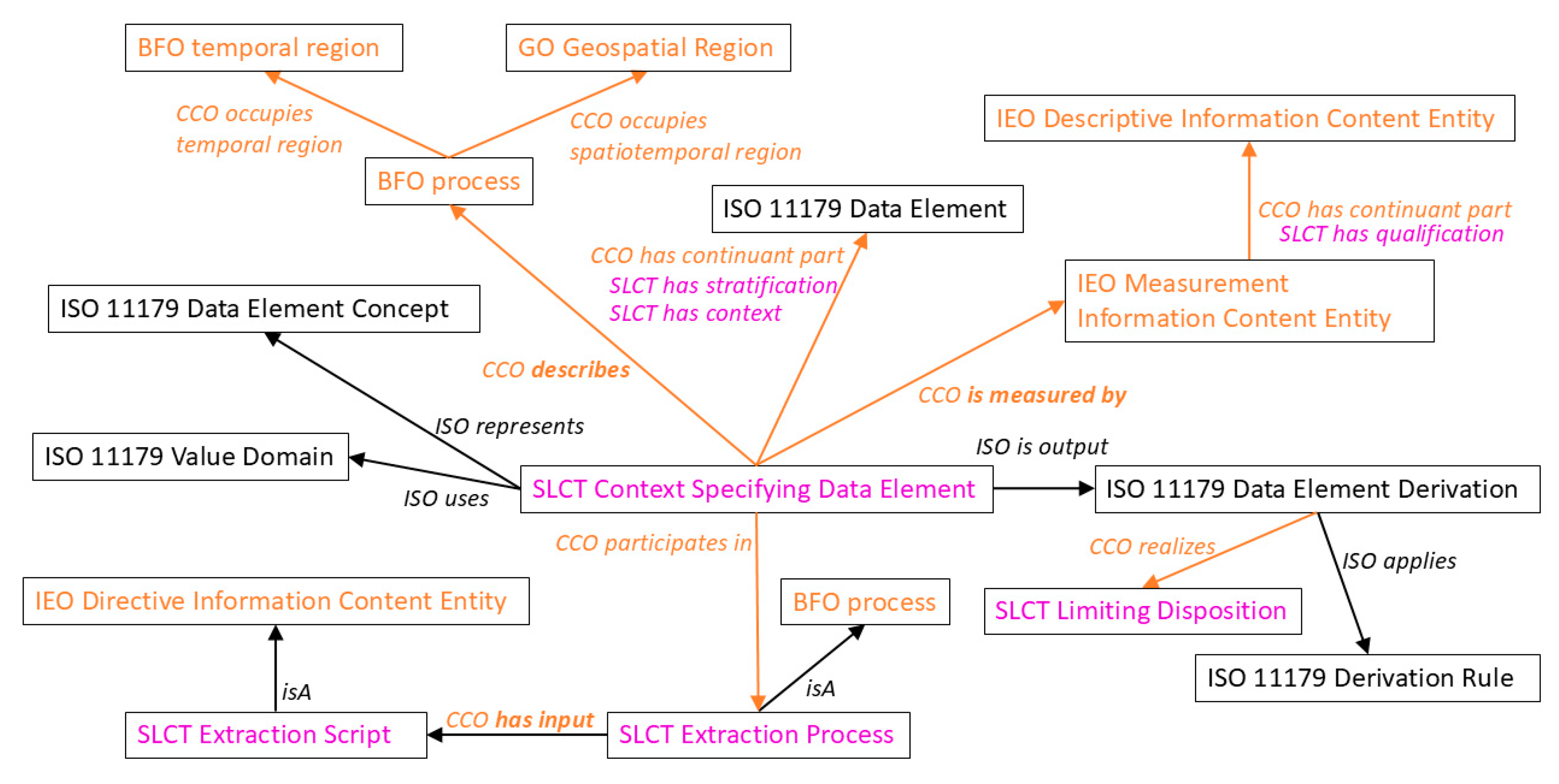

Figure 1 shows how contextualisation can be added to a data element within the SOLICIT framework. SOLICIT provides the contextualisation components using the concepts of the ISO/IEC 11179 metadata model and complements them with the semantic relations and ontology classes of CCO. These classes and relations are then further extended with specific ontology classes defined within SOLICIT. The FAIR data principles are thereby treated inherently within the framework. Findability of a data element, for example, is achieved over a federated search within a hierarchy of SOLICIT ontologies implemented in any given data domain. Once the relevant data element has been found, accessibility is granted where authorised via the SOLICIT “extraction process” class which provides the retrieval instructions or scripts. Interoperability is facilitated by the full complement of the contextual semantic relations that can provide mapping to standard terminologies via simple knowledge organization system (SKOS) relations [

35]. Finally, full contextual descriptions regarding the capture and meaning of the data, the assumptions, and biases, as well as any intermediate processing steps, which all form part of the SOLICIT framework, provide the means for enhancing reusability. The fact that SOLICIT builds on ISO/IEC 11179 and base-level and intermediate-level ontologies (Basic Formal Ontology – BFO [

36] and CCO respectively) ensures that the contextual information can be added following a limited and stable set of constructs and relationships.

Further contexts can be introduced into this framework using the SOLICIT sub relation “has context” of the CCO relation “has continuant part”. These contexts take the form of ISO/IEC 11179 data elements that are described in terms of object class, property, and value domain according to the metadata registry model. Moreover, in SOLICIT, the data element has a CCO relation “continuant part of” with the CCO class “descriptive information content entity” (c.f.

Figure 2). The latter can then, if required, use the associated set of CCO relations to extend the description of the context further.

2.2. Quality Dimensions in a General Data Contextualisation Schema

Many of the categories of the quality dimensions comprehensively identified by Miller et al [

28] (especially those related to each of the four top-level FAIR data principles and their 15 sub levels) form an inherent part of the formal contextual description of the data (as further elaborated under the FAIR data principle sub levels: F2, A2, I1, I3, and R1). These are addressed in SOLICIT’s standard constructs for contextualising indicators [

32]. Other dimensions such as understandability, usefulness, and efficiency are arguably the concern of the data application but can be determined from the general contextual elements; for example, understandability results from contextual aspects such as: the purpose of why the data were collected, the subjects of the data, the assumptions and limitations of the data collection processes, the data structure, and the codes/measurement units of the associated data variables, etc.

The category traceability contains both application-specific dimensions (quality of methodology, translatability) and data-specific dimensions (outliers, noise, spatial and temporal resolution, etc.). Separating these concerns of objectiveness (data-intrinsic quality dimensions) and subjectiveness (data application quality dimensions) allows a decoupling of the metrics defining the quality of the data from those related to the requirements on the data from a specific data application point of view.

2.3. Refactoring the Quality Dimensions in SOLICIT

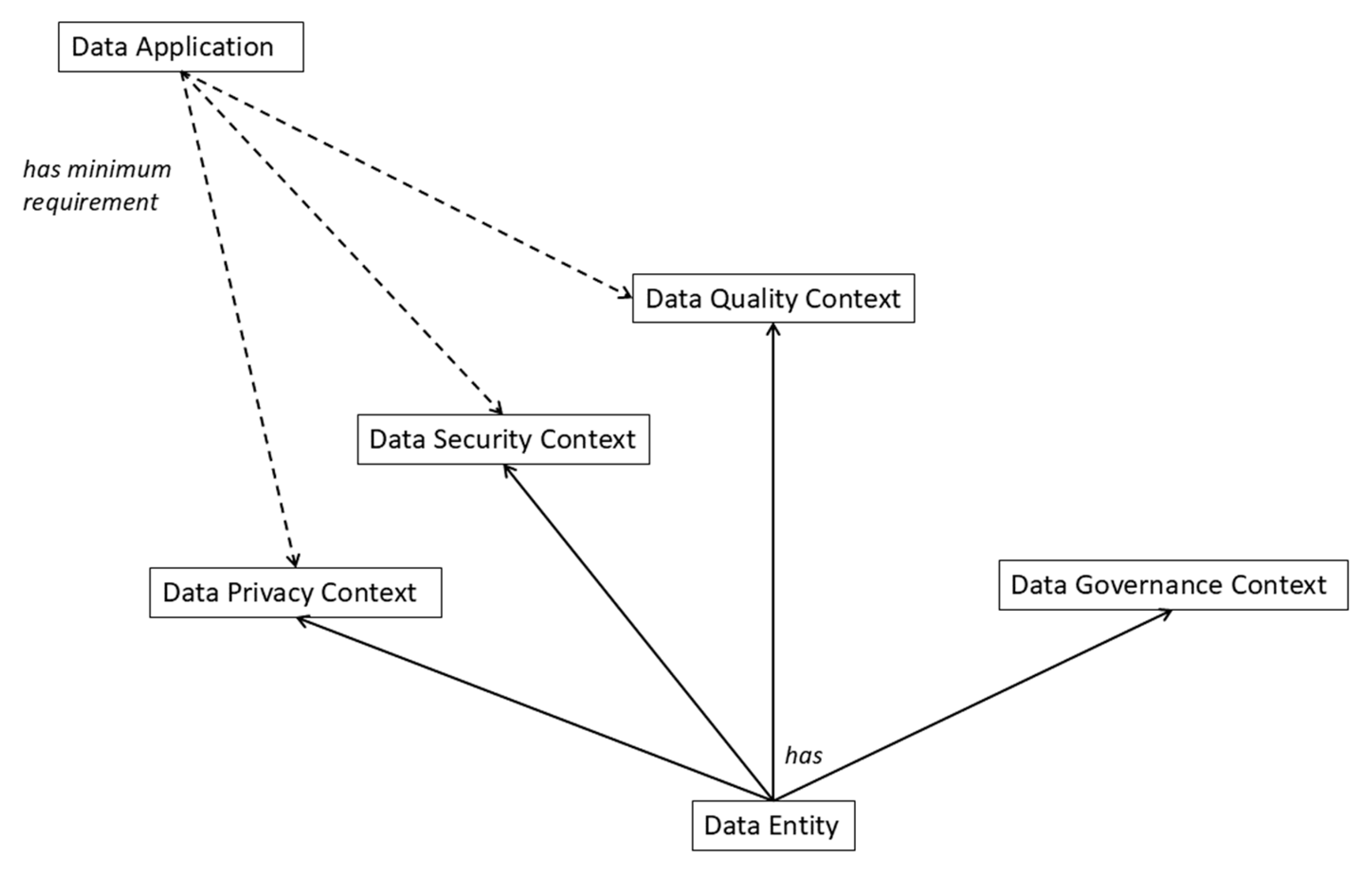

The categories of quality dimensions that remain unaddressed from Miller’s model include: credibility, completeness, consistency, and accuracy from the inherent top-level category; recoverability and portability from the system-dependent top-level category; and confidentiality, governance, compliance, and precision from the contextual top-level category. These dimensions can be managed in the data-centric model by introducing four dedicated contextual spaces, namely: data quality, data privacy, data security, and data governance. Included in the data governance context space are the recoverability and portability dimensions (which were defined under the system-dependent category), and precision can be added as a sub dimension of accuracy.

Table 2 shows the reclassification of the second and third-level categories of the DQ-centric model into the four specific data context spaces and the general data context. Regarding the latter, the data-specific dimensions of the “traceability” category can be handled via the general data description contexts (for spatial and temporal resolution), and via the “has qualification” relationships associated with the “Context Specifying Data Element” class (for “outliers”), and within the “credibility” dimension of the DQ context (for “verifiability” and “quality of methodology”).

Figure 3 illustrates the contextual spaces and shows the separation of concerns between the data entity under consideration and the data application. The more general data contextualisation information (including that addressing the FAIR principles) is not shown in this figure to retain clarity.

3. Results

The general contextualisation elements can be implemented using the standard classes and relations defined within the SOLICIT framework, most of which draw from CCO and ISO/IEC 11179.

Figure 1 illustrates some of these attributes that are described more fully in [

32]. The data entity to be described is instanced from the “context specifying data element” class. Since this class inherits from the ISO/IEC 11179 data element class, the data entity can be described with the ISO/IEC 11179 composite metadata structure of data element concept (consisting of object class and property) and value domain. The data element concept can be used to describe the type of data entity which could, for example, be a primary or processed data set in some domain, or a variable or common data element within the data set, or an indicator of some specific type. The data element concept together with textual descriptions of the data can all be used to search for data within a given domain to support the findability principle. Instructions for accessing the data or downloading them (where data protection laws allow) can be provided via the “extraction process” class/class-instance to support the accessibility principle along with the value domain metadata element describing the values the data can take and the associated units of measurement if relevant.

The “is output” relation points to a class or class instance describing the derivation of the data entity and the associated derivation rule and any causes of bias. The input to the derivation class is an ISO/IEC 11179 data element class (c.f.

Figure 2), which allows chaining of the data entity to an upstream process providing the inputs for the derivation process. The “has context” relation points also to an ISO/IEC 11179 data element class, allowing any number of contextual structured metadata classes/class-instances to be associated with the data entity and could be used for associating the contextual data spaces of

Figure 3 (c.f.

Section 3.1). The “describes” relation points to a BFO process class that can provide further description relating to the scope of the data entity and to its special and temporal coverage through the dedicated CCO relations attached to a BFO process.

Furthermore, it is important to note that since an ISO/IEC 11179 data element and its constituent metadata parts (object class, property, and value domain) are classifiable items according to the ISO standard, they can be classified and linked to external terminology systems and standard dictionaries, thereby avoiding the need to duplicate existing standard descriptions.

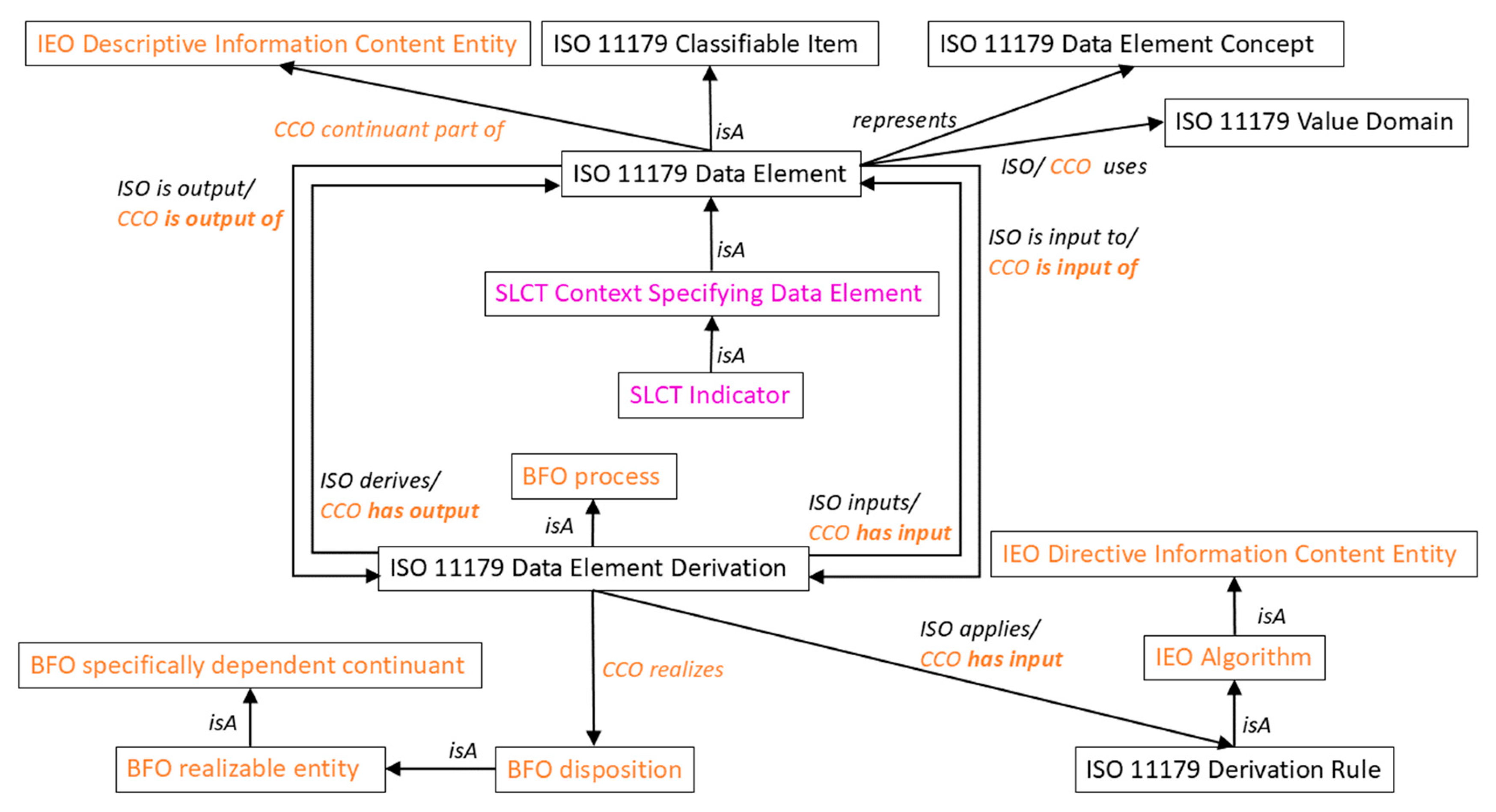

3.1. Contextual Data Spaces

Whereas the standard data contextual constructs of SOLICIT provide a rich means of supporting the four principles of FAIR, they can be extended to include the four contextual spaces of

Figure 3. A contextual space can be described by a relevant subclass of the “context specifying data element” class and linked to the data entity via the “has context” relation (c.f.

Figure 1). In order to illustrate this, we consider the data quality contextual space in

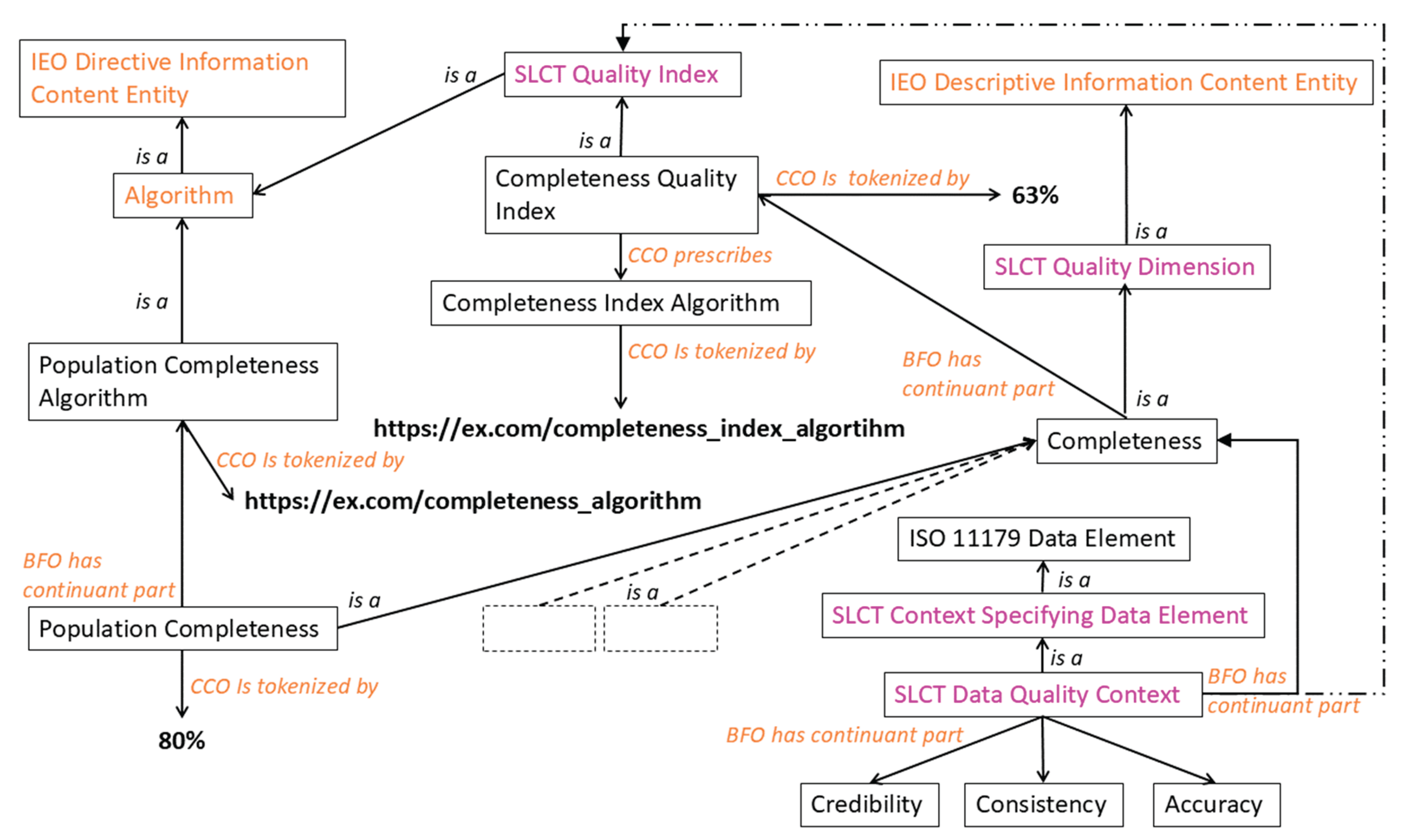

Figure 4. We create the “data quality context” class as a subclass of the “context specifying data element” class and use the CCO “has continuant part” relationship to point to the individual dimensions of the space. For the sake of argument, we retain four of the inherent quality dimensions (completeness, accuracy, consistency, and credibility) that Miller et al [

28] included in their model although we are free to define different dimensions. The quality dimension of currentness is dealt with in the general contextualisation elements (via the BFO temporal region class and “has qualification” sub relation of the CCO general relation “has continuant part”). These four quality dimensions can be described by relevant subclasses of the “descriptive information content entity” class defined in the CCO Information Entity Ontology, as illustrated in

Figure 4 for the “completeness” quality dimension.

The context space has been elaborated further for the “completeness” dimension by creating the sub dimension “population completeness”, which provides a quantitative measure of the population covered in the target population. Other sub dimensions can likewise be subclassed from the parent dimensions. In the example given, the value of “population completeness” is referenced by the CCO “is tokenized by” annotation property. The method or algorithm for calculating the value can be provided using the CCO relation “has continuant part” to a CCO “directive information content entity” or, by consequence, to one of its subclasses (in this case a subclass of the CCO “algorithm”). The calculation method in the example provided points to a URL, which might be a standard method for calculating population completeness. There is in essence no limit to how deep the subclassing may go, which permits considerable flexibility in realising more specific definitions of the quality dimension in cases where such granularity is required.

Given that other sub dimensions of the data quality context may contribute to an overall metric for the completeness dimension, one might envisage a composite value or index for completeness. In the figure, a “completeness quality index” has been associated with the completeness quality dimension via the CCO “has continuant part” relationship. This index is indirectly subclassed from a CCO algorithm class and therefore can be associated with a calculation method that is described here by a further URL. The same type of indexing could be applied to the data quality context itself.

Figure 4 includes a further attribute of the CCO “has continuant part” (dotted-dashed line) pointing to the “quality index” class to illustrate this possibility.

3.2. Othogonality of Top-Level Quality Dimensions

From the point of view of devising metrics for the four dimensions of the data quality context, it is important to ensure these top-level quality dimensions are orthogonal (independent) to avoid cross-interference and allow the calculation of an independent quality label on each of the four dimensions (c.f. point 7 of the enumerated list provided in the Introduction). This requirement need not necessarily apply to the sub dimensions since they can be given proportional weightings with respect to their contribution to each of the top-level orthogonal dimensions into which they feed. To achieve orthogonality in practice may not be easy given the different and overlapping interpretations of DQ dimensions. Certain measures can be taken however to ensure delineation of terms through clear and explicit definitions of what the dimensions include (and what they do not include in cases of ambiguity). Whereas three of the four inherent DQ dimensions have good separation, there could potentially be crosstalk between credibility and the other dimensions. The definition of credibility needs therefore to be steered in meaning towards retaining independence from the other dimensions. Thus, for example, a data entity may be deemed accurate since it can be verified that a value is correct (accuracy dimension); however, the means of verifying the value may not be optimal and thus the credibility dimension will capture this fact.

3.3. Dereferencing the DQ Context

A process similar to that followed for the data quality context can be applied to all the other contexts to build up a comprehensive contextual description of the data. Dereferencing the information is a relatively straightforward task that only involves a recursive search on the data entity to find the elements of interest. This could be implemented using SPARQL queries. The operation could also be automatically performed using AI tools to understand the applicability of the data entity to a given data application. In this respect, inferencing is greatly aided by use of the ISO/IEC 11179 metadata constructs, in which the object class and property together define the data element concept that is free to associate with any form of measurement unit (value domain), thereby providing a useful way of dealing with unstructured data (the data element concept, here relating to inherent data quality, need not be changed but be incorporated with the different value domain to provide a different data element description). The composite metadata structure of ISO/IEC 11179 also provides a convenient means of searching across data entities for commonalities and for determining any mappings between metadata elements or to standard terminologies.

3.3. Addressing the Issues Raised in the DQ-Framework Reviews

The process of contextualising data quality illustrated in

Figure 4 addresses several important principles highlighted in the reviews of DQ frameworks, in particular:

The relevance of particular quality dimensions to the data entity being described. For example, completeness is relevant only for certain data entities; it does not carry any meaning for an atomic data type. Moreover, completeness can be distinguished between population completeness and record completeness. Since the contextual information is described for a particular data entity in the data-centric model, the semantic relations are free to change with the type of data entity and therefore not all quality dimensions need be provided where they are not relevant;

The means of showing how a given quality dimension is calculated. SOLICIT provides the functionality to link a procedure, rule, or algorithm to the calculation of any given dimension, also at a composite level. This could be a standard algorithm, for instance specified at the ontology class level, or a variation of the standard method specified at the individual level;

A data entity is free to associate with any number of data DQ spaces. The latter are described by ISO/IEC 11179 data element metadata constructs and can therefore provide metrics to any number of quality metric value domains. Mapping between different value domains is also foreseen in the ISO/IEC 11179 standard;

The data-centric model is not prescriptive but only provides a generic framework that can be applied to the specificities of the type of data entity and data structure. It can therefore support structured and unstructured data, objective and subjective quality metrics, as well as describing data entity types from an atomic level to dataset level.

3.4. Application to the Indicator Derivation Process

A further strength of the data-centric model realised in a framework such as SOLICIT is that it allows contextualised data elements to point to the upstream data elements in a data-processing chain, providing to the data user the whole DQ provenance trail. Access to the data pathway is of particular importance for indicators used in supra national comparisons, where assumptions have to be made and compromises taken to align the DQ indices derived from different data collection modalities and data-variable availability.

In general, the indicator derivation process consists of several steps that include (c.f. [

37] for cancer incidence indicators):

Agreement of common data elements (CDEs) used as the basis for deriving the indicator;

Collection of data from primary data sources;

Verification and cleaning of data at local node;

Compilation of a record of CDEs for each data subject;

Validation of CDE datasets (either centrally or locally) using standardised rules and tools;

Stratification of the validated CDE datasets into aggregations of variables to provide an appropriate degree of anonymisation;

Agreement of the resulting anonymised datasets with the local nodes;

Analysis of the anonymised datasets and compilation of indicators for a specific purpose.

Given the multi-stage process, it is not only important for verification purposes to ensure a trace is available but also to provide the means of establishing a type of compound DQ trace across the whole pathway (with resolution into individual DQ indices for each process step). In the SOLICIT framework all contextualisation is associated with a given data entity and therefore all the data entities associated with the enumerated steps above can be contextualised individually and linked to the previous data entity in the process after the manner described in [

32].

In such an indicator derivation process, the data entities would constitute: (a) the primary data sources providing the data variables (steps 2 and 3) used for constructing a CDE; (b) a CDE record for a given data subject (steps 4); (c) a processed set of CDEs (step 5); (d) an aggregated dataset of CDE records (step 6); and (e) a standardised indicator set (step 8).

4. Discussion

We were unable to find a satisfactory DQ framework to describe the whole data-processing pathway influencing the integrated quality context of an indicator, nor did we wish to have to use a different framework for different stages of the process chain. The current set of DQ frameworks address data quality within specific domains for specific issues and are unable to provide a one-size-fits-all solution [

3,

4].

In contrast to taking a DQ-centric view of data, many difficulties can be resolved by taking a data-centric view of data quality and this is precisely the approach taken by the FAIR-data guiding principles. In the FAIR data model, quality is considered primarily as a concern for the data application to determine on the basis of the data’s metadata addressing the four foundational principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability. Whereas data quality, and more importantly how to measure it and then improve it, are questions of fundamental importance, arguably the more consequential issue concerns (re)use of data, which is essentially the main driver behind ensuring an appropriate level of data quality in the first place. What constitutes an “appropriate level” is itself a key question and very much related to the intended purpose of the data.

4.1. FAIR’s Emphasis on Data Contextualisation

The FAIR data approach therefore takes the focus off data quality and places it on the data contextualisation. The onus then becomes one of describing the data in a sufficient and standard way for data users to ascertain the usefulness of the data for their particular needs. Such an approach provides a two-fold decoupling of concepts that are tightly integrated into most DQ-centric frameworks. The first occurs in the separation of concerns between the data and the data-application. The DQ requirements of the latter can be expressed without reference to any particular data – they can be specified as a type of contract that data must fulfil to be used by the application. Decoupling at this level allows the data to be described without recourse to any data application thereby allowing a more objective description of the data that does not have to be repeated for different data applications.

The second level of decoupling relates to the quality dimensions themselves that can then be attributed either to the data contextualisation or the data-application requirements. Miller et al [

28] captured more than 240 individual quality dimensions referenced in different DQ studies and categorised them under 19 higher-level dimensions (c.f.

Table 1). Most of these dimensions can be attributed either to the general data context (e.g. accessibility, confidentiality, governance, recoverability, etc.) or to the data application requirements (e.g. understandability, usefulness, efficiency, semantics, availability, etc.). After performing this two-stage decoupling, the remaining dimensions are essentially those describing the intrinsic quality of the data. Although the FAIR data principles treat quality as a data-application concern, we believe that these intrinsic dimensions should be considered explicitly as part of the metadata and we therefore provide them with their own dedicated contextual space. This data quality context space, although illustrated in our example for structured data, would be applicable to unstructured data with the associated relevant dimensions [

38]. Other context spaces can also be created to provide further structure outside the general context fields.

4.2. The Need for a Data-Contextualisation Framework

Having elaborated the advantages of a data-centric model over a DQ-centric one, the major issue is to find an appropriate data-contextualisation framework. In the general absence of such frameworks, we used SOLICIT which we had developed earlier for the purpose of contextualising indicators. Since SOLICIT integrates the concepts of the ISO/IEC 11179 metadata registry standard with the base- and mid-level ontologies of BFO and CCO respectively, it uses a well-established and standard set of constructs and relations, which is of considerable importance for interoperability and scalability. We have shown how SOLICIT might be used to provide contextual information to describe the inherent quality dimensions specific to any particular data type. SOLICIT provides the possibility via its ISO/IEC 11179 constructs to access data elements across a data-process chain, allowing users to understand the evolution of any quality index and to see how it was calculated at each individual stage.

The framework is also able to address further limitations relating to DQ frameworks in general, including:

The anchoring of domain knowledge, which is central to data quality according to Karr [

39], who noted that “data can be useless for one purpose but adequate for others and domain knowledge is necessary to distinguish these situations”. Karr also observed that a pervasive DQ problem is the failure of documentation to distinguish clearly between ‘original data’ attributes and derived attributes calculated from original data;

The inconsistent definitions of quality dimensions and the need to handle both subjective and objective quality measures (even to the degree of elaborating a full set of assessment methods within a single quality dimension) as observed by Declerck [

17]. SOLICIT does not prescribe any definition or measure but allows them to be defined as a domain or sub domain decision to any degree of granularity of the quality dimensions. SOLICIT provides the means for comprehensively describing the definitions and measures or of linking them to standard definitions and for mapping between them where appropriate. Moreover, these definitions can be applied to the three hyperdimensions distilled by Karr out of DQ literature of data, process, use – of which Chen [

40] observed inadequate attention had been given to the process and use hyperdimensions.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Whereas we have tried to be specific in showing how a data-centric model could be implemented to satisfy the needs of describing data quality, for reasons of space, we could not be comprehensive. We have only skirted the discussion on the exact description of quality dimensions and have not considered any of the possible metrics for measuring them since this was out of our immediate scope. The framework we have introduced is agnostic of such issues and is free to reference any particular methodology and even to map between different ones. One of the strengths of SOLICIT is that it is extendible at a federated domain and sub domain level and can consequently be tailored to domain-specific needs without strict constraint to any prescribed formulation. We will however address these more pragmatic concerns when contextualising a real-world indicator as a following step.

The work we have undertaken here highlights the general lack of data-contextualisation frameworks without which the possibility of realising fully FAIR data is limited. Whereas SOLICIT goes someway to fulfilling this need, it is not an easy framework to use and requires knowledge of concepts that are not straightforward to assimilate especially in the integration of CCO and ISO/IEC 11179. It does, however, furnish a general purpose data-contextualisation framework allowing for standardisation of quality aspects according to a philosophy grounded on the four foundational principles of FAIR data.

One further consideration relates to the laboriousness of contextualising data and the balance that has to be struck between too much and too little. In a framework such as SOLICIT, there is a considerable overhead in agreeing and defining the various metadata components according to the metadata model of ISO/IEC 11179. However once accomplished, the components can be reused and recombined without necessarily have to define new ones. Moreover, since SOLICIT is an extendible framework, metadata reuse is facilitated through the provision of a hierarchical tree of metadata components pitched at the relevant degree of abstraction. The metadata components can also be linked to standard dictionaries and terminology servers, avoiding the need to redefine terms. Nevertheless, a certain amount of contextualisation is unavoidable if the data are to be widely useful. It is even more important given the current lack of overall agreement on definitive metrics for measuring the various quality dimensions. A framework such as SOLICIT is able to provide the data user with comprehensive information on the data processes involved and on how the quality has been assessed at each step.

5. Conclusions

The growing importance of interconnected data requires a means of adequately describing the veracity of the underlying data components. Existing DQ frameworks are generally highly context and data-entity dependent. They also disagree on the quality dimensions that should be included, apart from the widely accepted five or six intrinsic ones for structured data.

The lack of convergence to a single DQ framework motivates the quest for an alternative approach. We have attempted to show from the foregoing arguments that many of the contentions between different DQ frameworks can be resolved by decoupling the associated dependencies and dealing with them at an appropriate level of abstraction. A critical step in this regard is to switch the focus from a model that views everything about data as a quality issue (which we have referred to as a DQ-centric approach) to a more holistic data-centric approach that addresses the chief motivation of data reusability from the point of view of the FAIR data principles and allows the quality to be assessed from comprehensive contextual information provided as metadata.

A framework developed along these lines allows a separation between data-application requirements and a description of the actual data, which avoids the need to describe the quality of data according to different frameworks dependent on the data application. Another advantage of the data-centric approach is that the contextualisation is automatically framed in relation to the type of data thereby removing a further difficulty encountered in DQ-centric frameworks. It also results in a simpler model since most of the quality dimensions considered in DQ-centric frameworks can be resolved into general data contextualisation components.

We have shown an example of how DQ dimensions can be described within the SOLICIT data-contextualisation framework and linked to an overall quality index both at a quality dimension level and at overall composite quality level. Moreover, since SOLICIT can support data-chaining across a set of data processes, the quality indices can be dereferenced at every stage to show how any eventual quality label has been calculated. This is a particularly useful feature in the case of indicators, which generally result from a number of data-processing stages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N. and I.S.; methodology, N.N., R.N.C. and I.S.; software, N.N.; validation, R.N.C.; formal analysis, N.N.; data curation, N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N., R.N.C. and I.S.; writing—review and editing, R.N.C. and I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted using Protégé.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BFO |

Basic formal ontology |

| CCO |

Common core ontologies |

| CDE |

Common data element |

| DQ |

Data-quality |

| SKOS |

Simple knowledge organization system |

References

- DAMA UK. The six primary dimensions for data quality assessment - defining data quality dimensions. Available online: https://www.dama-uk.org/resources/the-six-primary-dimensions-for-data-quality-assessment (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- ISO/IEC 25012:2008. Software engineering — Software product Quality Requirements and Evaluation (SQuaRE) — Data quality model. International Organization for Standardization. Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Cichy, C.; Rass, S. An Overview of Data Quality Frameworks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 24634-24648. [CrossRef]

- Haug, A. Understanding the differences across data quality classifications: a literature review and guidelines for future research. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2021, 121, 12, 2651-2671. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.W.; Diane M. Strong, D.M.; Kahn, B.K.; Wang, R.Y. AIMQ: a methodology for information quality assessment. Information & Management 2002, 40, 2, 133-146. [CrossRef]

- Batini, C.; Cabitza, F.; Cappiello, C.; Francalanci, C. A comprehensive data quality methodology for web and structured data. International Journal of Innovative Computing and Applications 2008, 1, 3, 205-218. [CrossRef]

- Loshin, D. Economic framework of data quality and the value proposition. In Enterprise Knowledge Management: The Data Quality Approach; Publisher: Morgan Kaufmann, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001, pp. 73-99. [CrossRef]

- Pipino, L.L.; Lee, Y.W.; Wang, R.Y. Data quality assessment. Commun. ACM. 2002 45, 4, 211–218. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian-Coleman, L. Measuring Data Quality for Ongoing Improvement; Publisher: Morgan Kaufmann, Waltham, MA, USA, 2013.

- Del Pilar Angeles, M.; García-Ugalde, F. A data quality practical approach. Int. J. Adv. Softw. 2009, 2, 2, 259–274.

- Batini, C.; Barone, D.; Cabitza, F.; Grega, S. A data quality methodology for heterogeneous data. Int. J. Database Manage. Syst. 2011, 3, 11, 60–79. https://hdl.handle.net/10281/43608.

- Cappiello, C.; Ficiaro, P.; Pernici, B., HIQM: A methodology for information quality monitoring, measurement, and improvement. In Advances in Conceptual Modeling-Theory and Practice: ER 2006 Workshops BP-UML, CoMoGIS, COSS, ECDM, OIS, QoIS, SemWAT, Tucson, AZ, USA, November 6-9, 2006. Proceedings 25; Publisher: Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 339-351.

- Sundararaman, A.; Venkatesan, S.K, Data Quality Improvement Through OODA Methodology. In Proc. MIT ICIQ, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017.

- Vaziri, R.; Mohsenzadeh, M.; Habibi, J. TBDQ: A Pragmatic Task-Based Method to Data Quality Assessment and Improvement. PLoS ONE 2016 11, 5. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y. A product perspective on total data quality management. Communications of the ACM. 1998, 41, 2, 58-65. [CrossRef]

- English, L.P. Improving data warehouse and business information quality: methods for reducing costs and increasing profits; Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, United States, 1999.

- Declerck, J.; Kalra, D.; Vander Stichele, R.; Coorevits, P. Frameworks, Dimensions, Definitions of Aspects, and Assessment Methods for the Appraisal of Quality of Health Data for Secondary Use: Comprehensive Overview of Reviews. JMIR Med. Inform. 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Chan, S.H.M.; Whelan, H.; Gregório, J. A Comparison of Data Quality Frameworks: A Review. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 93. [CrossRef]

- ISO 8000-8:2015; Data Quality—Part 8: Information and Data Quality: Concepts and Measuring; Publisher: ISO, Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Federal Privacy Council. Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPS), 2024. Available online: https://www.fpc.gov/resources/fipps/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- European Commission. Quality Assurance Framework of the European Statistical System v2.0. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/64157/4392716/ESS-QAF-V2.0-final.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Government Data Quality Hub. The Government Data Quality Framework, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-government-data-quality-framework (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- DAMA International. DAMA-DMBOK Data Management Body of Knowledge, 2nd ed.; Publisher: Technics Publications: Sedona, AZ, USA, 2017; Available online: https://technicspub.com/dmbok/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. Data Quality Assessment Framework (DQAF), 2003. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/np/sta/dsbb/2003/eng/dqaf.htm (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Principles for Effective Risk Data Aggregation and Risk Reporting; Technical Report; Publisher: Bank for International Settlements: Basel, Switzerland, 2013. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs239.htm (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Choudhary, A. ALCOA and ALCOA Plus Principles for Data Integrity, 2024. Available online: https://www.pharmaguideline.com/2018/12/alcoa-to-alcoa-plus-for-data-integrity.html (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. Data Quality Assurance: Module 1: Framework and Metrics; Publisher: World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; p. vi, 30p. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240047365 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Miller, R.; Whelan, H.; Chrubasik, M.; Whittaker, D.; Duncan, P.; Gregório, J. A Framework for Current and New Data Quality Dimensions: An Overview. Data 2024, 9, 151. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [CrossRef]

- GO FAIR. R1.3: (Meta)data meet domain-relevant community standards. Available online: https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/r1-3-metadata-meet-domain-relevant-community-standards/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Bian, J.; Lyu, T.; Loiacono, A.; Viramontes, T.M.; Lipori, G.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Prosperi, M.; George, T.J.; Harle, C.A.; Shenkman, E.A.; Hogan, W. Assessing the practice of data quality evaluation in a national clinical data research network through a systematic scoping review in the era of real-world data. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020, 9, 27(12), 1999-2010. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, N.; Štotl, I. A generic framework for the semantic contextualization of indicators. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 6, 1463989. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. G.; De Colle Kindya, S.; More, C.; Cox, A. P.; Beverley, J. The common core ontologies. arXiv 2024, 2404.17758. [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 11179:2015. Information Technology—Metadata Registries (MDR)—Part 1: Framework. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso-iec:11179:-1:ed-3:v1:en (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- W3C and Semantic Web (1997). SKOS Simple Knowledge Organization System. Available online: https://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Basic Formal Ontology (2020). Basic Formal Ontology. Available online: https://basic-formal-ontology.org (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Giusti, F.; Martos, C.; Carvalho, R.N.; Zadnik, V.; Visser, O.; Bettio, M.; Van Eycken, L. Facing further challenges in cancer data quality and harmonisation. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14:1438805. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, A.; Chowdhury, S. Big Data Quality Dimensions: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Karr, A.F.; Sanil, A.P.; Banks, D.L. Data quality: A statistical perspective. Statistical Methodology 2006, 3, 2, 137-173. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hailey, D.; Wang, N.; Yu, P. A review of data quality assessment methods for public health information systems. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014, 11, 5, 5170-207. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).