1. Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecologic malignancy in developed countries, with over 417,000 new cases and nearly 100,000 deaths reported worldwide in 2020 [

1]. Its incidence continues to rise, driven by aging populations and the increasing prevalence of obesity and metabolic disorders [

2,

3]. While early-stage EC has a favorable prognosis, advanced disease remains a major therapeutic challenge, with a five-year survival rate below 20% [

4].

The molecular classification proposed by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) divides EC into four prognostically relevant subtypes: POLE ultramutated (POLEmut), mismatch repair deficient (MMRd), p53 abnormal (p53abn), and no specific molecular profile (NSMP) [

5]. These categories, translated into clinical practice through the Proactive Molecular Risk Classifier for Endometrial Cancer (ProMisE), now incorporated into international guidelines, including those from the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology/European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology/European Society of Pathology (ESGO/ESTRO/ESP, 2021), the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO, 2023) [

6,

7].A growing subset of ECs demonstrates features of more than one molecular subtype. These so-called

multiple-classifier tumors (e.g., MMRd–p53abn, POLEmut–p53abn) raise questions about risk classification and prognosis, particularly when conflicting prognostic signals coexist [

8,

9]. The MMRd–p53abn subgroup, in particular, remains under-investigated and lacks clear recommendations regarding risk assignment and clinical behavior.

Moreover, molecular EC studies are still limited in Central and Eastern Europe, despite growing efforts to standardize molecular diagnostics. To address this gap, we conducted a multicenter study across four Polish oncology centers to evaluate the prevalence and clinicopathological features of multiple-classifier ECs, with a particular focus on MMRd–p53abn tumors. The findings aim to support future refinements in risk stratification and clinical decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This multicenter retrospective study included 1075 patients with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer (EC) who underwent surgical treatment between April 2022 and March 2025 in four Polish gynecologic oncology centers (Silesian, Lesser Poland, Subcarpathian, and Lublin Voivodeships). Histotype and tumor grade were assigned according to the 2020 WHO classification [

10]. Lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) was classified as absent (no vessels), focal (1–4 vessels), or substantial (≥5 vessels). Histopathological assessment was conducted independently at each center according to WHO criteria, without central pathology review.

Lymph node status was evaluated in 794 of 1075 patients (73.9%). Among these, 552 (69.5%) underwent sentinel lymph node mapping and 242 (30.5%) underwent systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy. In the remaining 281 patients (26.1%), lymph node evaluation was omitted based on low-risk criteria or clinical judgment.

High-intermediate risk (HIR) and high-risk (HR) groups were defined per ESGO/ESTRO/ESP 2021 guidelines, based exclusively on clinicopathological parameters (e.g., FIGO stage, histotype, grade, LVSI, lymph node involvement), independent of molecular classification to avoid bias from multiple-classifier overlap [

7].

2.2. Molecular Classification and Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tumor tissue was subjected to immunohistochemical evaluation of mismatch repair (MMR) proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) and p53 using the Ventana BenchMark Ultra platform (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Standardized staining protocols were applied across institutions. MMR deficiency (MMRd) was defined as the loss of at least one MMR protein. Abnormal p53 expression (p53abn) included diffuse overexpression (>80% of tumor cells), complete absence, or subclonal staining, according to ProMisE criteria [

11].

2.3. DNA Extraction and POLE Mutation Analysis

DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue using either the QIAamp DSP DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) or Maxwell RSC DNA FFPE Kit (Promega). POLE exon 9, 11, 13, and 14 sequencing was performed using Sanger sequencing (BigDye Terminator v3.1, Applied Biosystems). In selected cases with discordant or inconclusive findings, next-generation sequencing (NGS) was conducted on the IonTorrent platform using AmpliSeq panels covering POLE, TP53, and MMR genes. Only pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (per ClinVar, OncoKB, Varsome) were included in molecular classification.[

12,

13,

14] The same molecular testing protocols and variant interpretation standards were previously applied in a national analysis of EC classification practices in Poland [

15].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test (for expected cell counts <5) or chi-square test (for ≥5). Continuous variables were assessed using Student’s t-test. Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for binary outcomes. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, Krakow Branch (Approval No. 6/2025), and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data collection complied with EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) standards.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Multiple-Classifier Tumors

Among 1075 patients, multiple-classifier endometrial cancers (ECs) accounted for 6.9% (74/1075), including MMRd-p53abn (3.9%, 42/1075), POLEmut-p53abn (0.4%, 4/1075), POLEmut-MMRd (1.7%, 18/1075), and POLEmut-MMRd-p53abn (0.9%, 10/1075).

3.2. MMRd, p53abn, and MMRd-p53abn Comparison

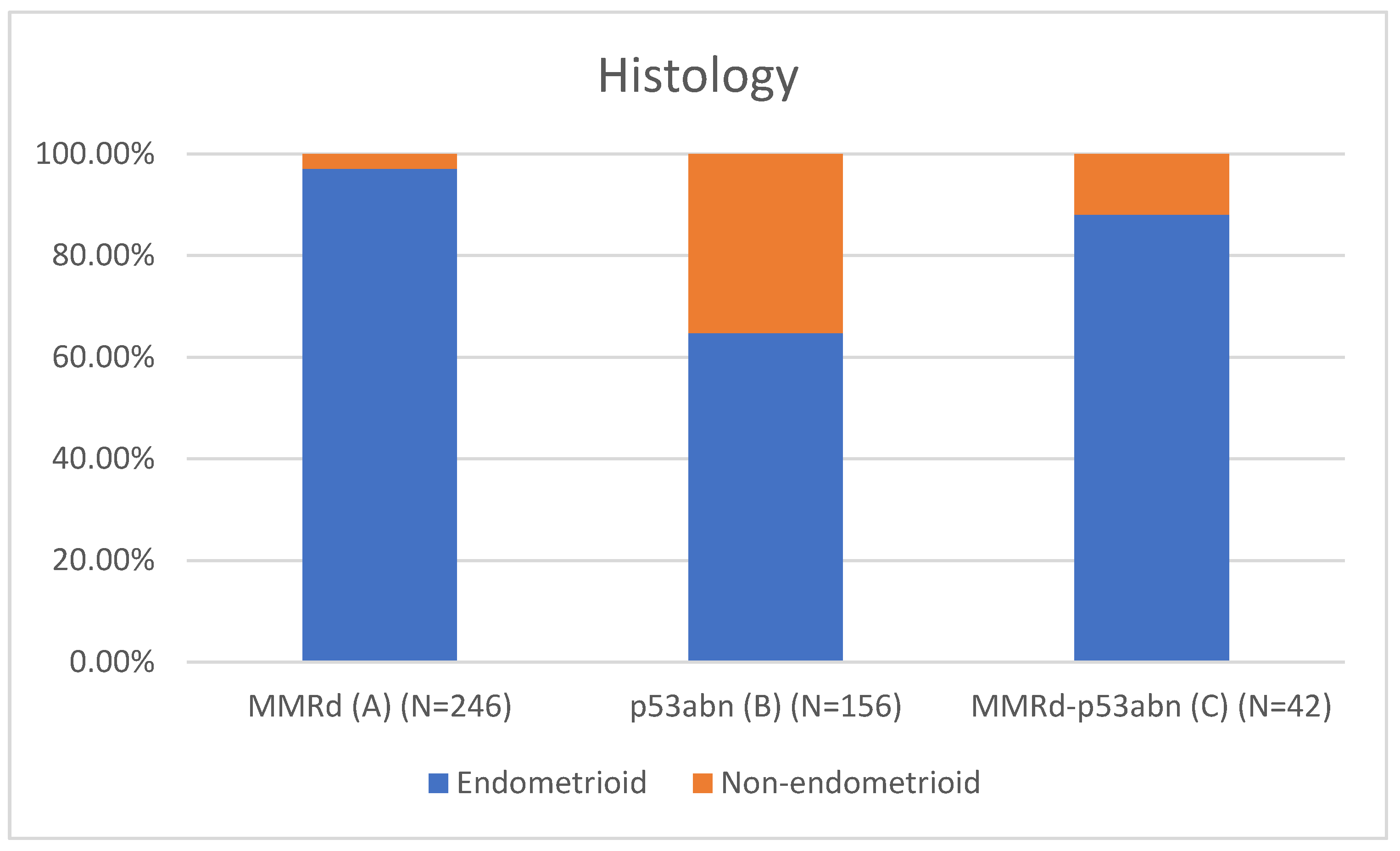

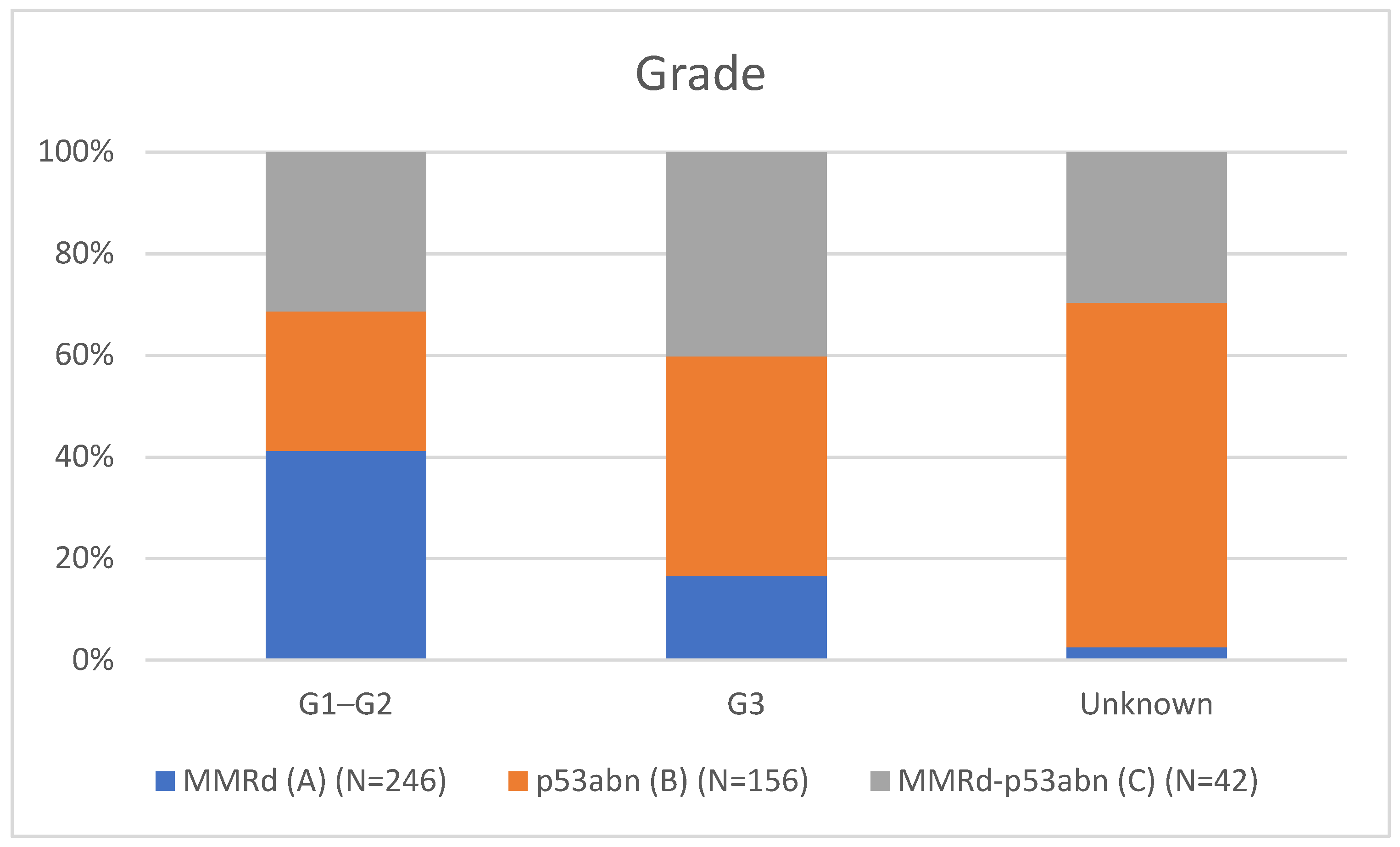

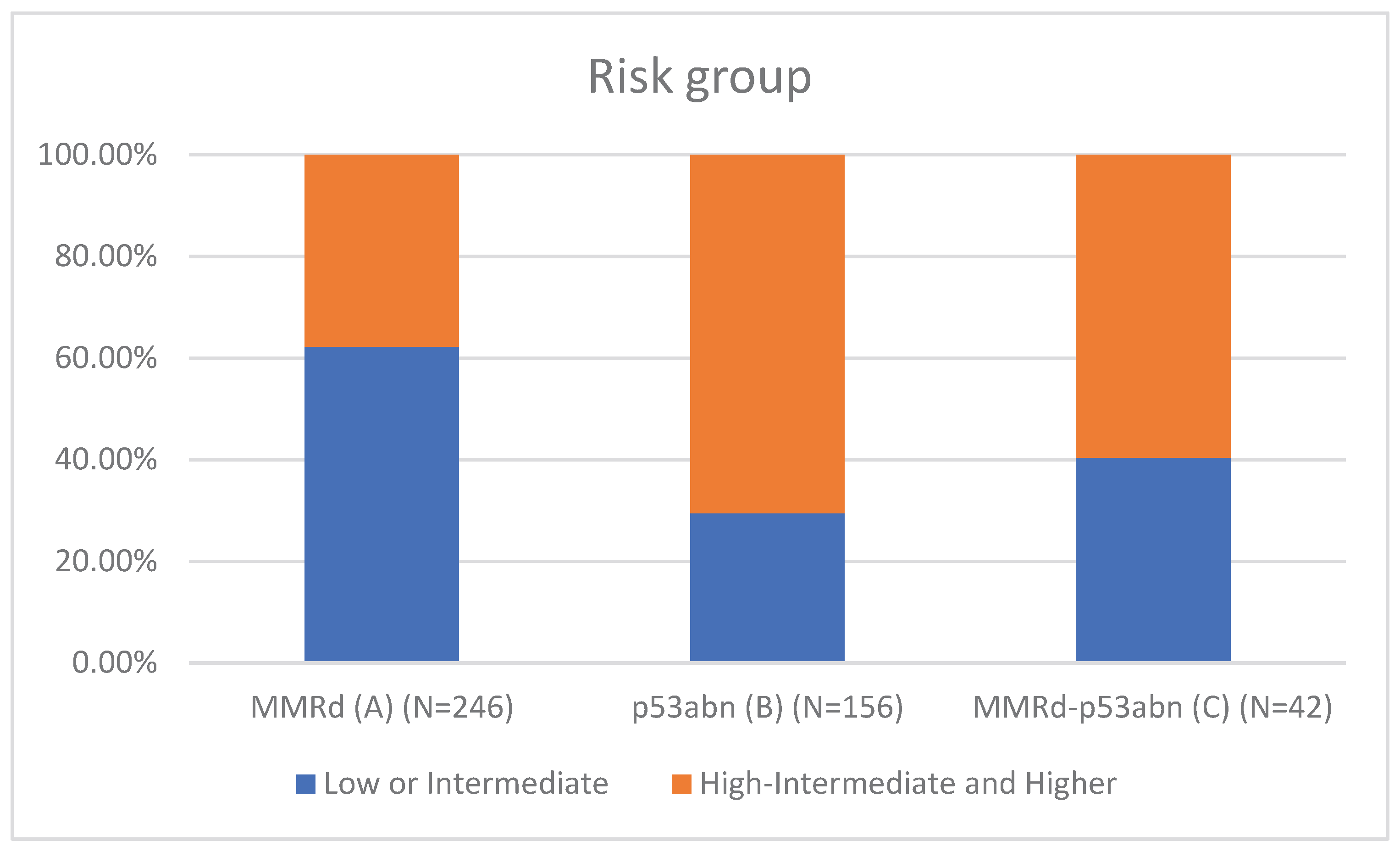

Table 1 presents the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with endometrial cancer by molecular subtype. Compared to classical MMRd tumors (N = 246), MMRd-p53abn tumors (N = 42) had higher rates of non-endometrioid histology (11.90% vs 2.85%, p = 0.018; OR = 3.78, 95% CI: 1.19–12.02), more frequent high-grade (G3) tumors (28.57% vs 11.79%, p = 0.002; OR = 3.26, 95% CI: 1.55–6.86), and a greater proportion assigned to high-intermediate/high-risk (HIR/HR) groups (59.52% vs 37.80%, p = 0.001; OR = 2.81, 95% CI: 1.50–5.25). These comparisons are visually represented in

Figure 1 (Histotype comparison),

Figure 2 (Grade comparison), and

Figure 3 (Risk group comparison).

Compared to p53abn tumors (N = 156), MMRd-p53abn tumors had a lower proportion of non-endometrioid histology (11.90% vs 35.26%, p = 0.001). MMRd-p53abn tumors also trended toward more frequent advanced FIGO III–IV stages (23.81% vs 13.82%, p = 0.192), although this did not reach statistical significance.

3.3. POLEmut and Multiple-Classifier POLEmut Comparison

Table 2 presents the clinicopathological comparison of classical POLEmut tumors with multiple-classifier subgroups involving POLE mutations. Compared to classical POLEmut tumors (N=30), the POLEmut–p53abn subgroup (N=4) demonstrated significantly higher rates of G3 tumors (75.0% vs 6.7%, p=0.005; OR = 42.00, 95% CI: 2.87–614.8), lymph node metastases (50.0% vs 3.3%, p=0.013; OR = 29.00, 95% CI: 1.77–475.3), and FIGO stage III–IV disease (75.0% vs 6.7%, p=0.005; OR = 42.00, 95% CI: 2.87–614.8). However, interpretation is limited by the small sample size and absence of outcome data.

The POLEmut–MMRd subgroup (N=18) also showed higher, though not statistically significant, rates of G3 tumors (16.7% vs 6.7%, p=0.198; OR = 2.80, 95% CI: 0.47–16.62), lymph node metastases (5.6% vs 3.3%, p=1.000; OR = 1.71, 95% CI: 0.11–27.48), and advanced FIGO stages (11.1% vs 6.7%, p=1.000; OR = 1.75, 95% CI: 0.23–13.26) relative to classical POLEmut.

Lastly, POLEmut–MMRd–p53abn tumors (N=10) exhibited more adverse features, including higher rates of G3 tumors (20.0% vs 6.7%, p=0.247; OR = 3.50, 95% CI: 0.46–26.46), lymph node involvement (30.0% vs 3.3%, p=0.192; OR = 12.44, 95% CI: 1.05–147.88), and FIGO III–IV stage (40.0% vs 6.7%, p=0.033; OR = 9.33, 95% CI: 1.23–70.66).

Although these trends suggest a deviation from the favorable prognosis associated with classical POLEmut tumors, the small numbers and lack of survival data preclude definitive conclusions.

4. Discussion

This is the first multicenter study from Central-Eastern Europe analyzing multiple-classifier endometrial cancers (ECs), with a 6.9% prevalence, consistent with the 3–11% range reported globally [

8,

9,

16]. Our higher rate compared to De Vitis et al. (4.8%) [

9] may reflect the large cohort size (N=1075), regional genetic variations, or differences in molecular testing protocols, underscoring the need for standardized diagnostics.

In contrast to León-Castillo et al. [

8], who suggested that MMRd-p53abn ECs behave similarly to MMRd-only tumors (recurrence-free survival: 92.2% vs. 70.8% for p53abn; p = 0.024), our MMRd-p53abn cases (3.9%, N=42)exhibited more aggressive features. These included higher rates of:

Non-endometrioid histology: 11.9% vs. 2.85% in MMRd (OR = 3.78; p = 0.018),

Grade 3 tumors: 28.6% vs. 11.8% (OR = 3.26; p = 0.002),

High-intermediate/high-risk status per ESGO/ESTRO/ESP: 59.5% vs. 37.8% (OR = 2.81; p = 0.001).

These findings suggest that MMRd-p53abn tumors may be biologically closer to p53abn than to MMRd, challenging current ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines [

7] that classify them as MMRd.

Compared to p53abn tumors, MMRd-p53abn ECs showed fewer non-endometrioid types (11.9% vs. 35.3%; p = 0.001), suggesting a distinct molecular profile. Bogani et al. [

17] similarly reported an increased recurrence risk in MMRd-p53abn tumors, further supporting the need for reevaluation of this subgroup.

Similarly, both POLEmut-p53abn (N=4) and POLEmut-MMRd-p53abn (N=10) tumors demonstrated aggressive features, particularly regarding advanced stage:

FIGO III–IV in 75% (POLEmut-p53abn) and 40% (POLEmut-MMRd-p53abn), compared to 6.7% in classical POLEmut ECs [

18],

Grade 3 tumors in 75% vs. 6.7% (OR = 42.00; p = 0.005),

Lymph node metastases in 50% vs. 3.3% (OR = 29.00; p = 0.013).

These data raise concern that coexisting p53 abnormalities may negate the typically favorable prognosis of POLEmut tumors. This is consistent with Jamieson et al. [

19], who reported 14% nodal involvement in POLEmut ECs, aligning with our findings.

The aggressive features observed in MMRd-p53abn tumors also have potential implications for immunotherapy. Owing to their MMRd status, these tumors may respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors such as dostarlimab, as demonstrated by Mirza et al. in the GARNET trial [

20]. However, the coexistent p53abn component may compromise efficacy, emphasizing the need for prospective trials tailored to multiple-classifier ECs.

Importantly, additional evidence supports the notion that p53 abnormalities may exert a dominant negative prognostic influence even within MMRd tumors. Kato et al. [

18] reported that in non-Lynch MMRd tumors, the presence of p53abn was associated with significantly worse 5-year OS (53.6% vs. 93.9%; p = 0.0016). Michalova et al. [

21] similarly observed that among five MMRd/TP53mut patients with follow-up, three developed metastases, and one patient died, supporting the notion of biological aggressiveness. De Vitis et al. [

9] also noted a trend toward higher recurrence in MMRd-p53abn tumors, although the finding did not reach statistical significance.

Taken together, these observations underscore that multiple-classifier ECs, especially those involving p53 abnormalities, may not fit neatly into existing risk stratification schemes. Future studies with larger patient cohorts and long-term survival data are essential to refine classification and optimize individualized treatment strategies.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the absence of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) data precludes direct prognostic evaluation of multiple-classifier endometrial cancers (ECs). Second, the relatively small size of some molecular subgroups—particularly POLEmut–p53abn and POLEmut–MMRd–p53abn—limits statistical power and the generalizability of their clinicopathological features. Third, the lack of central pathology review may have introduced interobserver variability in histotype, grade, and LVSI assessment, although standardized WHO 2020 criteria were applied at all sites. Fourth, detailed characterization of MMR protein loss (e.g., isolated vs. paired MLH1/PMS2 or MSH2/MSH6 loss) was not performed, which may limit interpretation of MMRd subtypes. Molecular testing was performed using harmonized protocols, but variation in the use of NGS (only in selected cases) may have impacted the detection of rare multiple-classifier combinations.

6. Conclusions

Multiple-classifier ECs, particularly MMRd-p53abn, POLEmut-p53abn, and POLEmut-MMRd-p53abn, appear to exhibit distinct clinicopathological features compared to single-classifier tumors. The presence of p53 abnormalities—even in tumors harboring POLEmut or MMRd—may be associated with more aggressive phenotypes, including high-grade histology, advanced FIGO stage, and lymph node metastases. These observations underscore the complexity of interpreting co-existing molecular alterations and suggest that multiple-classifier tumors may not be adequately captured by current risk stratification schemes. Although our study does not allow for prognostic conclusions, the observed patterns support further investigation into whether these tumors warrant distinct consideration in future classification and treatment frameworks.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, W.Sz. M.N-J., P.B. ; methodology, W.Sz, T.K., P.B.; software,W.Sz, M.N.-J.; validation, W.Sz. P.B. formal analysis W.Sz. M.N.-J. P.B.; investigation W.Sz.,T.K.,R.P-M. J.J. M.Ś. M.C.-S, M.N-J., I.W. J.T., P.B.; resources W.Sz, M.C-S.;J.J.;R.P-M.; M.Ś, I.W. J.T.; data curation W.Sz.,T.K..,M.Ś. R.P-M,;J.J.M.C.-S, M.N-J., I.W. J.T., P.B, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation W.Sz. M.N-J, P.B.R.P-M; writing—review and editing W.Sz. M.N-J, P.B.;.; visualization, W.Sz. M.N-J, P.B..; supervision,P.B.; project administration, W.Sz, M.N-J..; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approved by Maria Skłodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, Krakow Branch (Approval No. 6/2025, 9 January 2025). Conducted per Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent obtained.

Informed Consent Statement

At the start of the treatment, written consent was obtained from all 1075 subjects involved in the study for the purpose of retrospective analysis of their medical data.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

Wiktor Szatkowski (lecture fees: AstraZeneca); Małgorzata Nowak-Jastrząb (lecture fees, travel: AstraZeneca, MSD); Tomasz Kluz (lecture fees for, travel grants: AstraZeneca, GSK); Aleksandra Kmieć (no conflict); Małgorzata Cieślak-Steć (lecture fees for: AstraZeneca, GSK; clinical trials: AstraZeneca, MSD, PSI, Medpace, Roche, Syneos); Magdalena Śliwińska (no conflict); Izabela Winkler (no conflict); Jacek Tomaszewski (lecture fees: GSK, Gedeon Richter); Jerzy Jakubowicz (no conflict); Renata Pacholczak-Madej (travel grants: Accord, BMS, MSD; lecture fees: AstraZeneca, BMS, GSK, Novartis, Roche); Paweł Blecharz (lecture fees, travel grants, advisory boards: AstraZeneca, GSK, Merck, AbbVie).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EC |

Endometrial cancer |

| POLEmut |

POLE ultramutated |

| MMRd |

Mismatch repair deficient |

| p53abn |

p53 abnormal |

| NSMP |

No specific molecular profile |

| HIR/HR |

High-intermediate/high-risk |

| G3 |

High-grade |

| TCGA |

To Cancer Genome Atlas |

| LVSI |

Lymphovascular space invasion |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry for |

| NGS |

Next-generation sequencing |

| VUS |

Variants of unknown significance |

| OS |

Overall survival rate |

| PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| ESGO/ESTRO/ESP |

European Society of Gynaecological Oncology/European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology/Europe Society of Pathology |

| FIGO |

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

| ProMISE |

Proactive Molecular Risk Classifier for Endometrial Cancer |

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71(3):209–49. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2023. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2023;73(1):17–48. [CrossRef]

- Oaknin A, Bosse T, Creutzberg CL, Giornelli G, Harter P, Joly F, et al. Endometrial Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Annals of Oncology. 2022;33(9):860–77. [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2022. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2022.html (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Levine DA, Getz G, Gabriel SB, Cibulskis K, Lander E, Sivachenko A, et al. Integrated Genomic Characterization of Endometrial Carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67–73. [CrossRef]

- Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, Yang W, Lum A, Senz J, et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: A Simple, Genomics-Based Clinical Classifier for Endometrial Cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(5):802–13. [CrossRef]

- Concin N, Matias-Guiu X, Vergote I, Cibula D, Mirza MR, Marnitz S, et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Endometrial Carcinoma. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2021;31(1):12–39.

- León-Castillo A, de Boer SM, Powell ME, Mileshkin L, Mackay HJ, Leary A, et al. Clinicopathological Characterisation of Multiple-Classifier Endometrial Carcinomas: A Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study. The Journal of Pathology. 2020;250(3):312–22. [CrossRef]

- De Vitis LA, Schilling A, Kort J, Feltmate CM, Muto MG, Berkowitz RS, et al. Clinicopathological Characteristics of Multiple-Classifier Endometrial Cancers: A Retrospective Multi-Institutional Study. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2024;34(2):229–38.

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Female Genital Tumours. 5th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020.

- Kommoss S, McConechy MK, Kommoss F, Leung S, Bunz AK, Magrill J, et al. ProMisE: A Simple and Reproducible Prognostic Molecular Classifier for Endometrial Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2018;24(15):3912–21.

- ClinVar. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- OncoKB. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Available online: https://www.oncokb.org/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Varsome. The Human Genomics Community. Available online: https://www.varsome.com/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Szatkowski W, Popieluch J, Blecharz P, Łuczyński K, Kojs Z, Basta A, et al. Analysis of Endometrial Cancer Classification in Poland: A Multi-Center Retrospective Study. Cancers. 2025;17(2):213. [CrossRef]

- Vermij L, Smit V, Horeweg N, Bosse T. Molecular Classification in Endometrial Cancer: Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2021;74(6):345–52. [CrossRef]

- Bogani G, Murgia F, Ditto A, Raspagliesi F. Outcomes of Multiple-Classifier Endometrial Cancer: A Retrospective Study. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2024;50(1):107269. [CrossRef]

- Kato M, Maeda K, Tanikawa M, Kohno T, Nakamura K, Kiyono T, et al. Clinical Features and Impact of p53 Status in Uterine Cancer. Cancer Science. 2024;115(5):1646–55. [CrossRef]

- Jamieson A, Huvila J, Chiu D, Thompson EF, Gilks CB, Talhouk A, et al. Endometrial Carcinoma Molecular Subtype Correlates with the Presence of Lymph Node Metastases. Gynecologic Oncology. 2022;165(2):376–84. [CrossRef]

- Mirza MR, Chase DM, Slomovitz BM, dePont Christensen R, Novák Z, Black D, et al. Dostarlimab for Primary Advanced or Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2023;388(23):2145–58.

- Michalova K, Lukas J, Drozenova J, Scheinost O, Hruska F, Spacek J, et al. Next-Generation Sequencing in Endometrial Carcinoma Classification. Virchows Archiv. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).