1. Introduction

Soil color is one of the most outstanding soil morphological characteristics and is often the first property recognized or recorded by a soil scientist or a layperson [

1,

2]. Soil color is determined by many factors so in reverse, it has been used as an indicator for various soil properties. The most common application of soil color is probably to estimate soil organic carbon and soil moisture [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Soil color has also been used in the studies of soil genesis, classification, texture, structure and nutrients [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Despite the apparent connections between soil color and many important soil properties, until recently, measurement and use of soil color are largely descriptive and qualitative. There are several factors contribute to this. Physically, color is determined by light reflectance. For a real-life object, light reflectance is a mixture of lights in different wavelengths. So, color is also determined by how the light reflectance is perceived by human eyes. As such, the science of color is complex, cutting across disciplines such as physiology, psychology, physics, chemistry, and mineralogy [

1]. It has been found that human eyes have three different color-response mechanisms and therefore color spaces generally use three parameters to represent three color stimuli [

11,

12]. Popular color spaces include the RGB color systems that are widely used in electronic systems and the CIE color systems defined by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) which are often used as reference standards [

13]. In soil science, soil color is traditionally recorded in the Munsell color space which defines the color space with three parameters: Hue for the type of a color; Value for the lightness of a color; and Chroma for the saturation of a color [

14]. In practice, soil color is determined visually and subjectively by comparing a soil sample to chips in a Munsell soil color book. There are often substantial errors associated with this method and therefore, there is widespread perception that soil color cannot be measured accurately [

4,

15].

With the development of color science and spectroscopy, instrument for color measurement has evolved a lot over the past century [

16]. Modern instruments have enabled soil scientists to measure soil color more precisely and accurately but more importantly, the measurement is more objective, not relying heavily on the experience and judgement of the operator. Therefore, more and more studies have been using colorimeter sensors and spectrometers for soil color data acquisition [

4,

5,

9,

17,

18,

19]. Another method for color data acquisition is through image analysis. Early applications of image analysis on soil properties include air photos and photos taken using handheld digital cameras [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. A special case of handheld digital camera is smartphone camera. Smartphones are increasingly becoming a must-have portable device for everyone, and each smartphone has a camera. With the rapid development of camera capability and applications, smartphones are increasingly being used as a readily available, convenient yet powerful detection device by general citizens [

2]. The potential for recording and estimating various soil properties (including color) with smartphones through citizen science is tremendous.

Many studies have been conducted in the past decade to use image analysis (especially with smartphones) as an alternative to the specialized colorimeter or spectrometer for soil color measurement to further estimate other soil properties that correlate with color. For example, Gómez-Robledo et al. [

25] developed an Android application that obtains the color parameters in the Munsell and CEI color spaces. The authors found that their method had lower errors than the traditional method of visual determination of soil color from a Munsell soil color book. Aitkenhead et al. [

23] extracted color and image texture information from photos taken with an iPhone 2 and used a neural network model to estimate multiple soil properties (soil structure, soil texture, bulk density, pH and drainage category). Han et al. [

10] developed a method to use smartphone as a color sensor for soil classification. Perry et al. [

26] tested various models on using smartphone images to estimate soil organic matter and soil moisture.

Despite the success of using image analysis for color detection, camera-derived color has been reported to have high errors [

2]. Two major sources of errors are the optical characteristics of the camera and the lighting condition (illumination). Each camera has a combination of lenses and sensor which as a whole adds its unique signature to the digital color data recorded by the smartphone. Different camera settings complicate the situation even further. As a result, color parameters recorded for the same object with different cameras are not the same even all other conditions are kept the same. Gómez-Robledo et al. [

25] noted the possible impact of smartphone camera on the accuracy of the predicted soil properties. Kirillova et al. [

27] found that the color prediction results from two cameras were different and such discrepancy could not be effectively calibrated by using an external standard. Yang et al. [

28] tested five smartphones and found that the color detection from the five phones followed different patterns at different wavelength ranges. Another well known source of errors for color measurement is the photographic lighting (illumination). As such, the CIE published a series of standard illuminants and recommended four illuminating and viewing geometries [

16].

One strategy to control these errors is to standardize the camera and the light source. For example, many studies used a single camera or smartphone for all the samples [

3,

6,

23]. To control the lighting condition, a standard light source was often used, and the lighting setup was carefully designed [

25,

30]. In fact, for specialized color measuring instruments, an internal light source following these CIE standards is used [

29]. This strategy may work well for scientific research, but its technical requirements and high costs significantly restricted its use, especially for measurement in the field or by untrained citizens using smartphones. Another strategy to control these errors is to use an external color reference for calibration. The true values of color parameters for the color reference are measured with a reference method (e.g., a high-end spectrometer). The color reference is placed beside the target object when the photo is taken so that they will have the same errors. Based on the true values of the color reference, the color of the target object can then be corrected. One example of this strategy is the color checker card. It is often used with image postprocessing software in the photography world for color correction of a digital camera [

30,

31]. A less sophisticated but more common practice is to use a gray card to adjust the white balance of an image, which is believed to be able to correct the illumination difference to some degree [

3,

6]. However, it has been reported that using a single-color reference was not sufficient to correct the color [

27].

One step further, Levin et al. [

22] used plastic chips of different colors for calibration which the authors claimed can correct errors associated with both camera and lighting condition. Aitkenhead et al. [

23,

24] adopted this method but enhanced its applicability by replacing the plastic color chips by easily portable reference card with bands in different degrees of gray from white to black. However, none of these studies has validated the effectiveness of the calibration method or quantified the improvement in color detection with the calibration. Given the complicated patterns of errors for different smartphones in different ranges of wavelength as reported by Yang et al. [

28], it is likely that a handful of data points provided by these references will not be enough for the calibration for the full range the color space albeit they may be better than a single-color reference. For soil color measurement, the most sophisticated calibration so far was probably the one conducted by Kirillova et al. [

27]. The authors used a set of subsamples of the soil samples as the reference. Although this approach may be able to enhance the accuracy of the color detection significantly, preparing such a reference is difficult and time consuming. The applicability of the reference is also questionable as the range of soil color can vary a lot from region to region, from soil type to soil type and even from field to field.

Overall, there is still no validated method that can be easily applied to correct errors associated with camera and lighting condition for color measurement with image analysis. In particular, to support citizen science, the method needs to be effective, simple and inexpensive. In this study, we propose to use a color checking card (termed color plate herein) with a range of color squares, placed beside the object of interest, as the color reference to calibrate the color measurements with image analysis. The objective is to quantify the effectiveness of the proposed color calibration method for color parameters derived from different cameras under different lighting conditions on different objects including soil samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measuring Objects

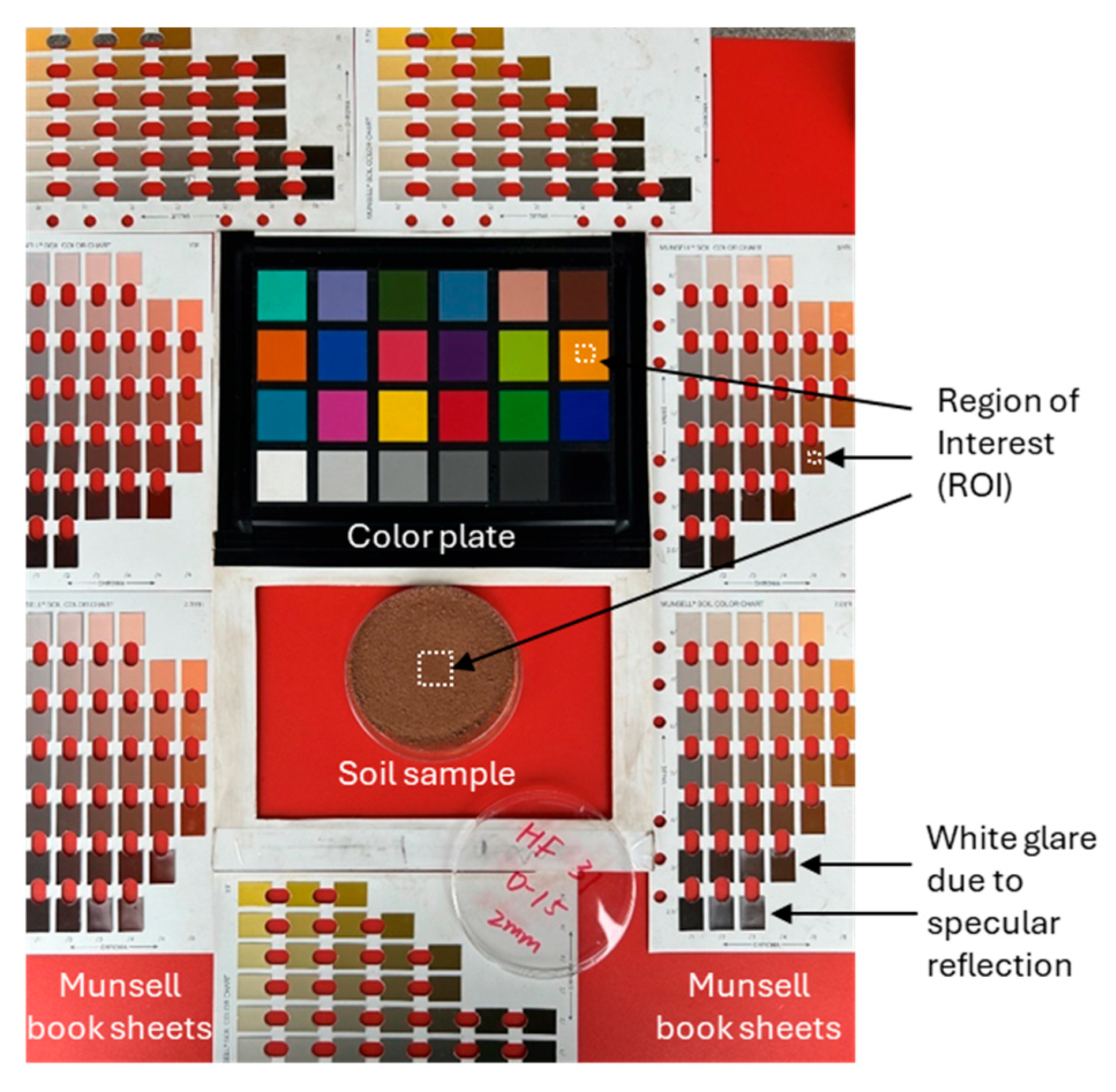

Three different types of objects were used in this study. The first was a commercially available color plate (Spyder Checkr 24 Target Color Cards, Datacolor©, Lawrenceville, NJ, USA) designed to be used together with a specialized software for postprocessing images to correct the color bias due to cameras (

Figure 1). To serve the purpose of color correction for the whole color space, the color plate has 24 color squares that are distributed evenly in the color space. Taking the advantage of such design, the color plate squares were used as the color references for calibration in this study. They also served as one type of measuring objects in this study following the leave-one-out cross-validation procedure which will be described in detail in later sections.

The second type of objects were color chips in sheets taken out from a Munsell soil color book (Pantone©), which is widely used for soil color determination in soil science. Seven sheets from the book were used, including the sheets for 10R, 2.5YR, 5YR, 7.5YR, 10YR, 2.5Y, and 5Y, covering a broad range of soil colors commonly found in Canada. It should be noted that because the surface of the color chips is glossy, due to specular reflection, some color chips showed white glare in some images (

Figure 1). The color detected from image analysis for these color chips obviously did not represent their true color. Therefore, these colors chips were excluded from the analysis and in total, there were 219 color chips used in the data analysis. Also, each color chip has a unique published color in the Munsell color book. These published Munsell color parameters were used as a benchmark for the validation of the reference color measurements (measured with FieldSpec 4 as described in the next section).

The third type of objects were soil samples. These soil samples were collected from sites in three Canadian provinces: New Brunswick (NB), Prince Edward Island (PEI), and Manitoba (MB) with 10 samples from each site and a total of 30 soil samples. These samples were selected because they represented the range of soil colors observed in Canada, from the blackish Chernozem in the prairies, to the yellowish Luvisolic and Podzolic soils in eastern Canada and the distinct red soil in PEI. On each site, the samples were taken along a transect going down the slope so that the samples also represented the soil catena along the slope, typically having a range of nutrient levels, especially soil organic carbon content. All samples were air-dried, passed through a 2-mm mesh sieve, and evenly spread (~1 cm thick) in petri dishes for measurement or imaging.

2.2. Reference Color Values Measured with FieldSpec 4

The color reflectance for all objects were measured with FieldSpec 4 (Malvern Panalytical, Boulder, CO, USA), a high resolution spectroradiometer. This instrument operates across a spectral range of 350–2500 nm, providing precise reflectance data that are often used to serve as a benchmark of accurate color measurements [

17]. All measurements were conducted in a lab and CIE standard illuminant A was selected to minimize external light variability. During the measurement, the probe was positioned at a fixed distance of 3 cm and held at a 45-degree angle towards the object. A white reference panel was used before every ten measurements to standardize the reflectance values and maintain the accuracy of the data. Three replicate measurements were taken for each object and each measurement consisted of ten spectral reflectance readings, which were averaged to improve the accuracy of the data.

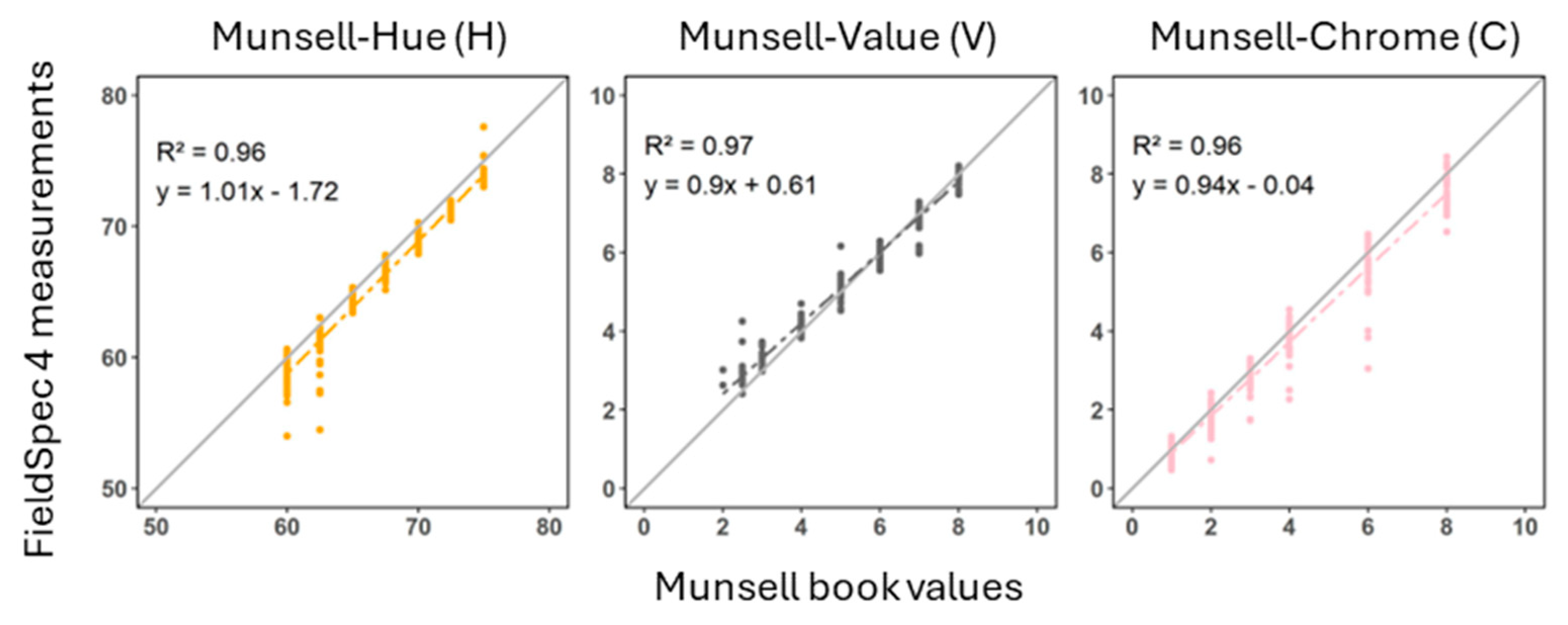

The spectral reflectance values were averaged for specific wavelength ranges corresponding to the blue (450–495 nm), green (495–570 nm), and red (620–750 nm) color channels. These values were then scaled to an 8-bit format (0–255) as the three color parameters: Red (R), Green (G) and Blue (B) for the RGB color space. The RGB values were converted to the Munsell Hue (H), Value (V), and Chroma (C) values using the munsellinterpol package in R [

32]. An adjustment was applied to the H values to account for the circular nature of the hue scale, which represents continuous transitions between different types of colors. The R package used a 0 to 100 scale for H with the values of 0 and 100 corresponding to a red color. For a soil with a H value close to 0, a small error may result in huge difference in H value (e.g., a H value of 1 showed as 99 with an error of 2 H unit). Given that red hues were common among the soil samples in this study, we applied a shift of 50 units so that the starting and ending H centred at the rarely observed blue hues, minimizing the effects of the circular scale on error analysis. This adjustment was applied to all hue values in this study.

2.3. Image Acquisition

The three types of objects were place on a table and arranged with the color plate and one soil sample in the middle whereas the Munsell color book sheets on the sides (

Figure 1). While there was only one soil sample in one picture, the same color plate and Munsell color book sheets were in every picture. Four smartphones were used, including an iPhone 14 (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA), a Huawei Mate 10 (Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), a Samsung Galaxy S23, and a Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra (Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Suwon, South Korea). These smartphones were selected because they were produced in different years, by different companies or of different models. As a result, the camera specifications for these four smartphones vary a lot, potentially influencing their color acquisition performance (

Table 1).

The images were captured under six lighting conditions, including two indoor and four outdoor lighting conditions. These conditions were chosen to represent typical lighting conditions in both laboratory and field studies. The two indoor lighting conditions, Inside-Dim and Inside-Normal, were set by turning on two thirds and all of the lights in the room, respectively, to represent different lighting conditions in a lab. The four outdoor lighting conditions, Overcast-AM, Overcast-PM, Sunny-AM and Sunny-PM, were designed to represent the lighting condition at different times in a day (morning and afternoon) in typical weather conditions (overcast or sunny) for field experiments.

All images were taken from a fixed top-down perspective, with the smartphones pointed straight down and positioned approximately 30 cm above the table surface. The default mode was selected with auto-focus and auto-exposure enabled to allow each device to adjust to the lighting conditions by default, but flash and HDR modes were disabled to prevent artificial color enhancement. Each layout (thus every soil sample) was photographed three times for each lighting condition with each smartphone. There was a total of 2160 photos taken. The photos were saved in their original image format (jpeg) without compression.

2.4. Image Processing and Color Calibration

The image was scaled, rotated, and cropped to a standardized resolution of 2821 × 3520 pixels using the GIMP software. A Region Of Interest (ROI) was defined for each object in the photo (

Figure 1). The ROI areas were 30 × 30, 5 × 5 and 300 × 300 pixel areas for the color plate squares, Munsell book chips and soil samples, respectively, all in the centre areas of the objects. For each image, there were a total of 244 ROIs, including one for the soil samples and 24 and 219 for the color plate squares and Munsell book chips respectively. For each ROI, the RGB values for all pixels were extracted and averaged using the magick package in R [

33]. The RGB values were then converted to Munsell HVC values using the munsellinterpol package in R. These RGB and HVC values were used as the raw data before the color calibration.

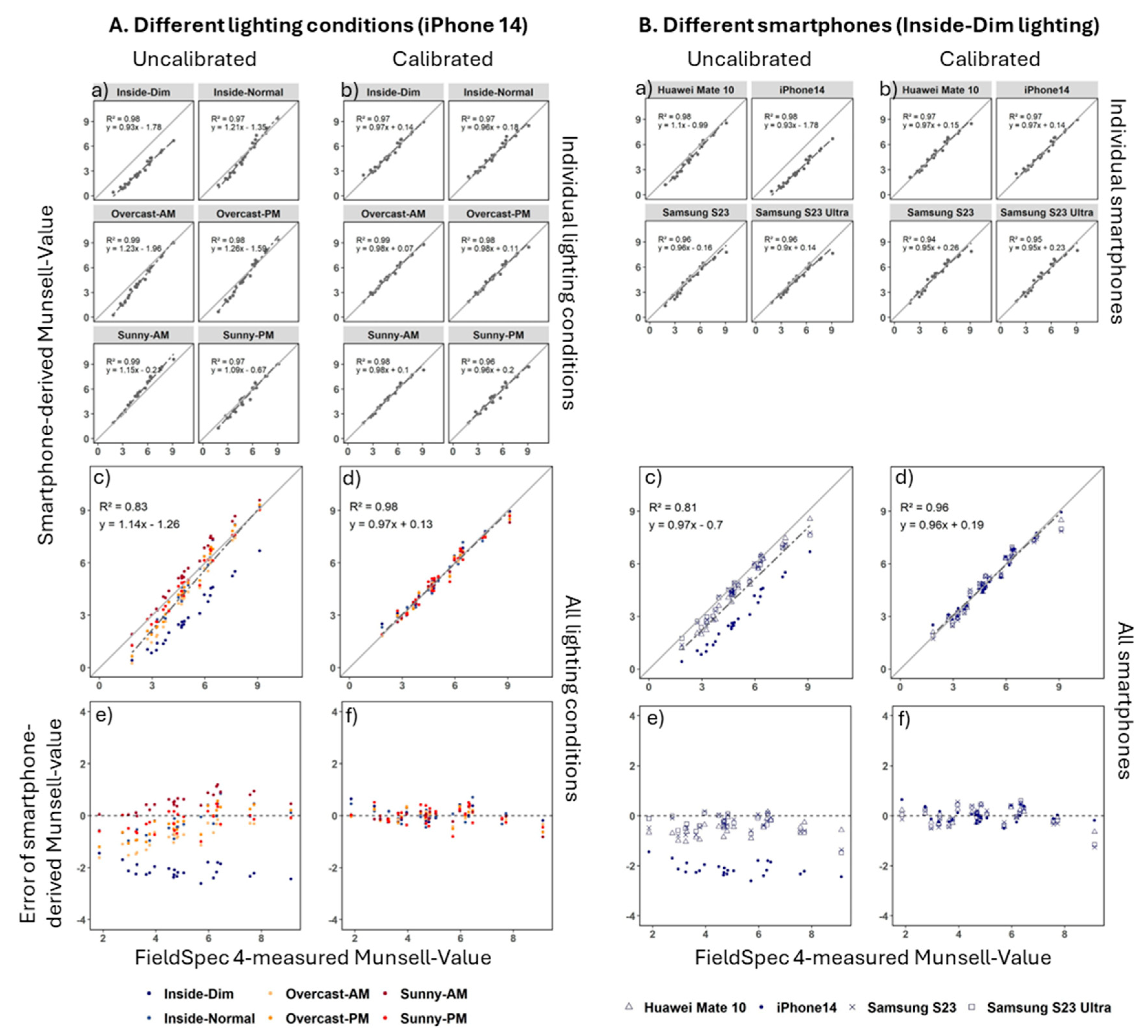

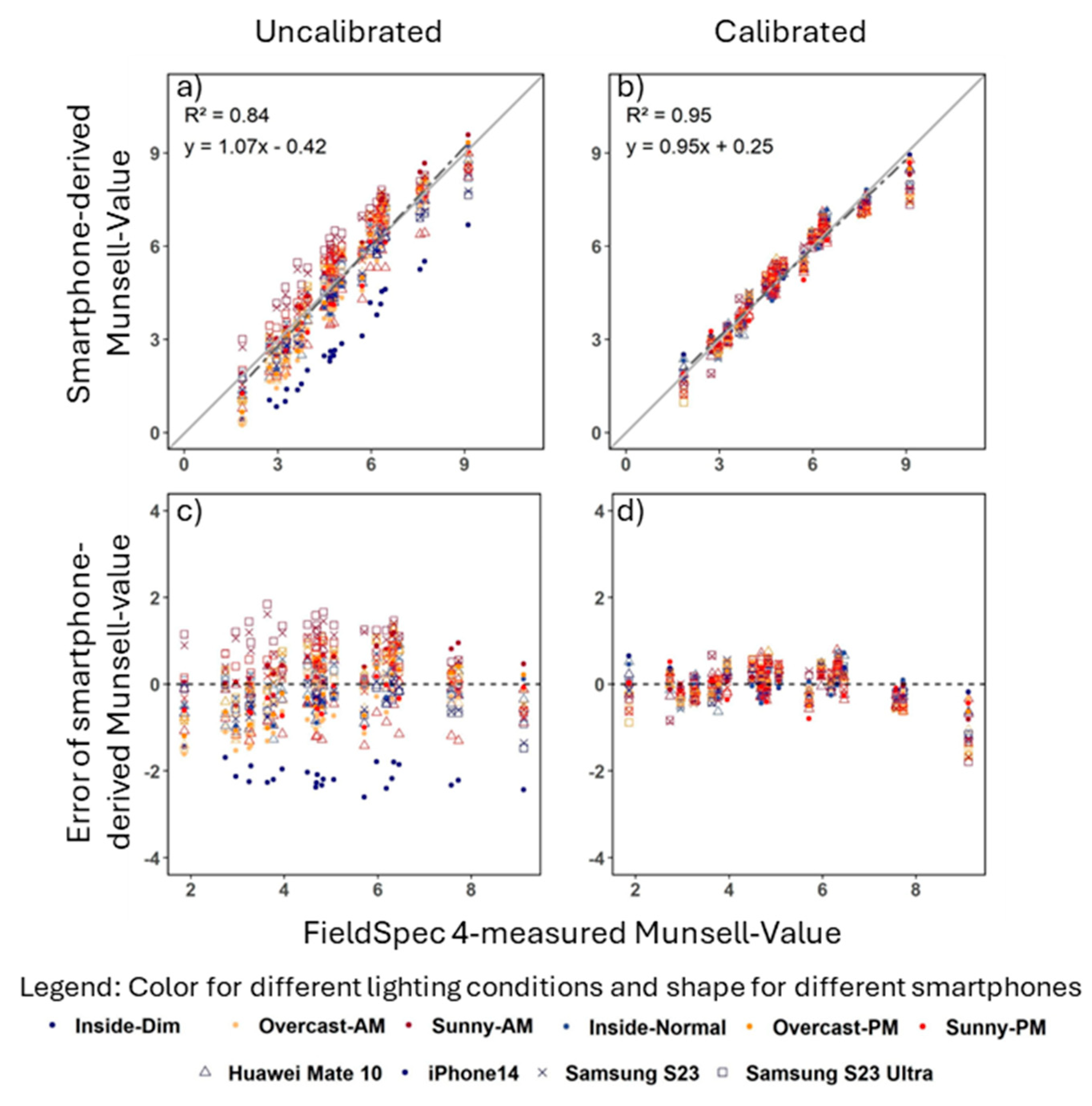

The color calibration was done for each color parameter in each image separately based on the image-derived versus the FieldSpec 4-measured values for the reference color plate. The image-derived raw color parameter values were plotted against the corresponding FeildSpec4-devrived values. A linear regression model was established for each color parameter between the two sets of data for the color plate squares. The regression model for a given color parameter was then applied back to each object on the image to obtain the calibrated value (aligned to the FeildSpec4 measurements) for this color parameter. This process went through one by one color parameter for all objects in the image. In the end, each object in the image will have a set of new values, considered as the calibrated (or corrected) values, for all color parameters. It should be noted that for the color plate squares, the calibration followed a leave-one-out cross-validation procedure (also called jackknife cross-validation). To calculate the calibrated value for a given square, the linear regression model was built on the data for the other 23 squares, leaving out only the square to be calculated. By doing so, potential bias due to the square in question itself being included in the regression analysis can be avoided. However, for the Munsell book chips and the soil samples, all 24 squares were used in building the regression models.

2.5. Precision and Accuracy Assessment for the Uncalibrated and Calibrated Data

All data analyses were conducted in R using the tidyversepackage [

34]. For the FieldSpec 4 spectrometer data, mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV) were calculated from the three repeated measurements for each color parameter of each object. Statistical metrics (mean, minimum, maximum, percentiles and range) were calculated for each type of objects for the above mean, SD and CV (calculated from the three repeats) to assess the precision and accuracy of the FieldSpec 4 measurements.

To assess precision and accuracy of the smartphone image analysis data, the smartphone-derived values were plotted against the FieldSpec 4-measured values, and a linear regression model was established for these two sets of data via regression analysis. The coefficient of determination (R2) of the model and the slope of the regression line and its distance to the 1:1 line were used to assess the accuracy and precision of the smartphone-derived values. Error of the smartphone-derived value for each color parameter of each object in each image was calculated by subtracting it by the corresponding FieldSpec 4-measured value. Mean and SD of the errors for a given object under different lighting conditions were calculated for each phone. Statistical metrics (mean, minimum, maximum, percentiles and range) for the means and SDs among all the objects of a given type were calculated to assess the effects of lighting conditions on the accuracy and precision of the color parameters. Similarly, Mean and SD of the errors for a given object were calculated for different smartphones under each lighting condition and statistical metrics of these means and SDs among all objects of a given type were calculated to assess the effects of smartphones on the accuracy and precision of the color parameters. These analyses were done for each color parameter separately and for the uncalibrated and calibrated smartphone-derived values separately so that the enhancement of the calibration for each individual color parameter can be quantified.

It should be noted that for the same layout of a specific soil sample (the color plate and all the Munsell book sheets were in every photo), although three images were taken with a specific smartphone under a specific lighting condition, only one image was used in the above mentioned analyses. This was done because analysis with the three images showed that the repeatability of the data derived from the three images were very high and errors were negligible (typically less than 0.1%). By using only one image, the results reflect the citizen science scenario more realistically since the requirement for taking three pictures could be a hurdle for ordinary citizens to participate in such exercises. In the same vein, for the color plate square and Munsell book chip data analysis, only photos for one soil sample should be used because the color plate and Munsell book sheets were in every photo and as such, for the same smartphone of the same lighting condition, there were 30 photos, each for one soil sample. The results were almost identical no matter which soil sample was picked. The data presented in this manuscript was for a randomly selected soil sample (BR-317) from the New Brunswick site.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.; methodology, S.L., F.Z., Y.K., A.K, D.L., M.G.; software, F.Z., A.K.; validation, S.L., F.Z.; formal analysis, F.Z., S.L.; investigation, F.Z., Y.K., S.L., A.K., M.G., D.L.; resources, S.L., D.L.; data curation, Y.K., F.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L., F.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.L., F.Z., Y.K., A.K., D.L., M.G.; visualization, F.Z., S.L., Y.K.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, S.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Layout of the objects in the photos.

Figure 1.

Layout of the objects in the photos.

Figure 2.

Measurements derived from FieldSpec 4 compared to values provided in the Munsell soil color book.

Figure 2.

Measurements derived from FieldSpec 4 compared to values provided in the Munsell soil color book.

Figure 3.

Uncalibrated (a, c, e) and calibrated (b, d, f) smartphone-derived values compared to FieldSpec 4-measured values of Munsell-V (a, b, c, d) and the associated errors of the smartphone-derived values (e, f) as examples to show the effects of the calibration method on correcting color parameters under: A. different lighting conditions (photos all taken with iPhone 14), and B. with different smartphones (photos all taken under Inside-Dim lighting condition) for color plate squares.

Figure 3.

Uncalibrated (a, c, e) and calibrated (b, d, f) smartphone-derived values compared to FieldSpec 4-measured values of Munsell-V (a, b, c, d) and the associated errors of the smartphone-derived values (e, f) as examples to show the effects of the calibration method on correcting color parameters under: A. different lighting conditions (photos all taken with iPhone 14), and B. with different smartphones (photos all taken under Inside-Dim lighting condition) for color plate squares.

Figure 4.

Uncalibrated (a) and calibrated (b) smartphone-derived values compared to FieldSpec 4-measured values of Munsell-V and the associated errors of the smartphone-derived values (c, d) as examples to show the effects of the calibration method on correcting color parameters for both lighting conditions and smartphones for color plate squares.

Figure 4.

Uncalibrated (a) and calibrated (b) smartphone-derived values compared to FieldSpec 4-measured values of Munsell-V and the associated errors of the smartphone-derived values (c, d) as examples to show the effects of the calibration method on correcting color parameters for both lighting conditions and smartphones for color plate squares.

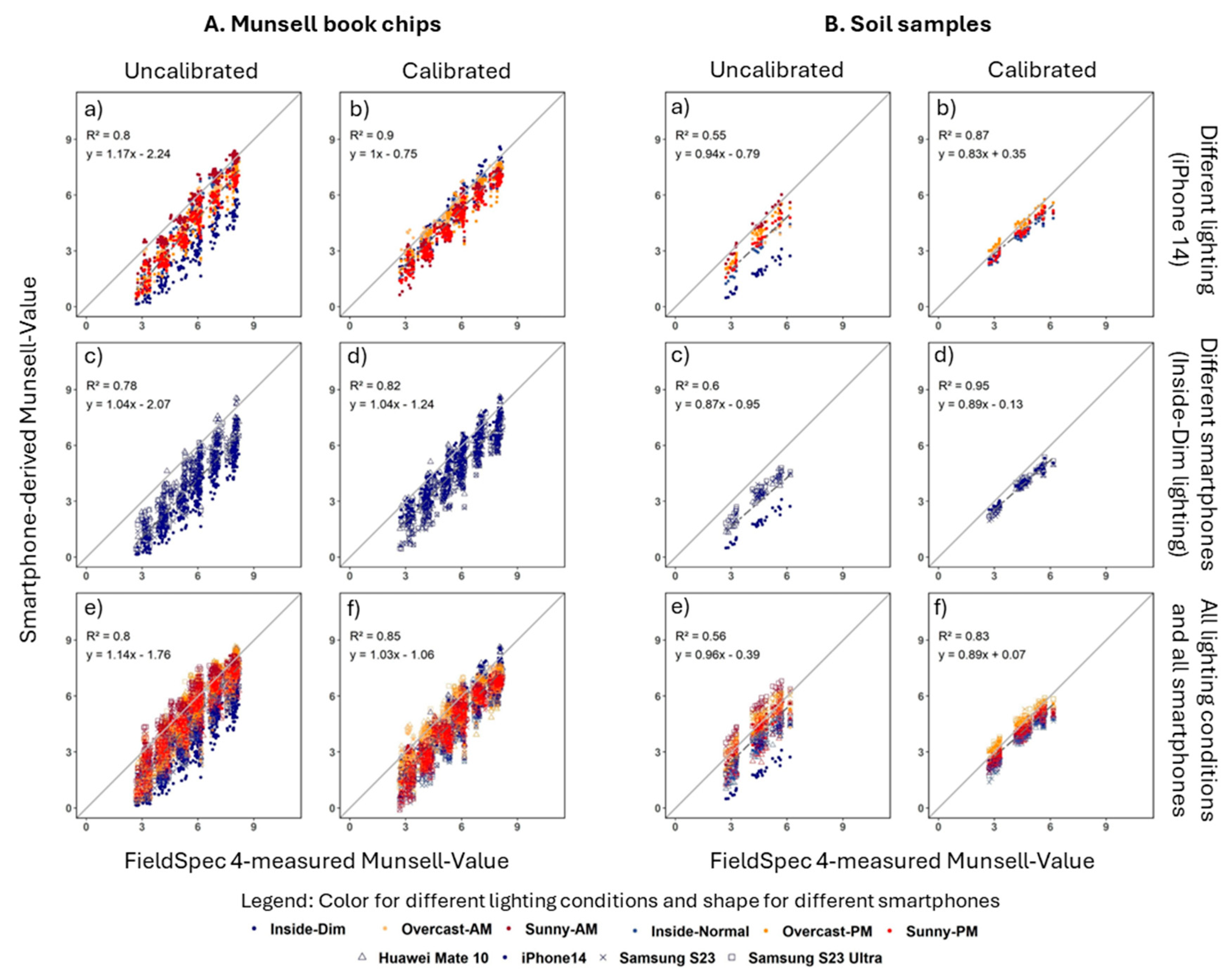

Figure 5.

Uncalibrated (a, c, e) and calibrated (b, d, f) smartphone-derived values compared to FieldSpec 4-measured values of Munsell-value as examples to show the effects of the calibration method on correcting color parameters for lighting conditions and smartphones, respectively and combined for: A. Munsell book chips, and B. soil samples.

Figure 5.

Uncalibrated (a, c, e) and calibrated (b, d, f) smartphone-derived values compared to FieldSpec 4-measured values of Munsell-value as examples to show the effects of the calibration method on correcting color parameters for lighting conditions and smartphones, respectively and combined for: A. Munsell book chips, and B. soil samples.

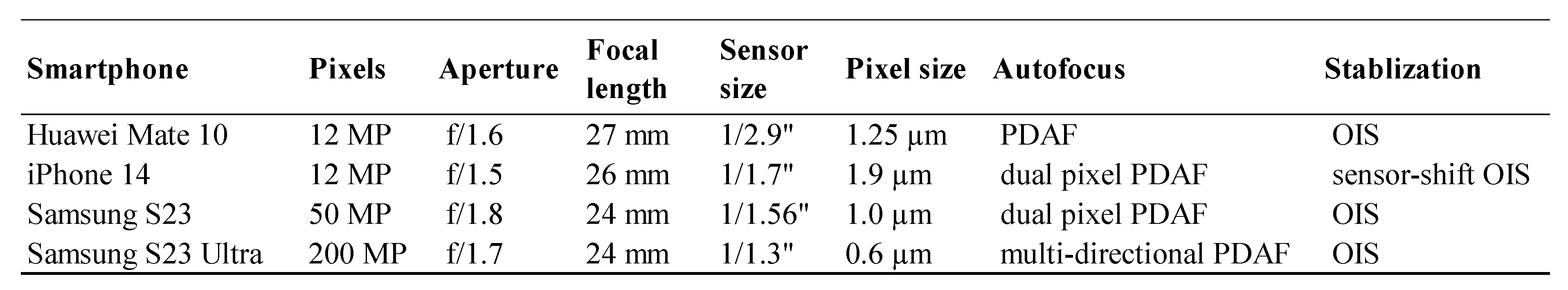

Table 1.

Specifications for the main camera for the four smartphones used in this study.

Table 1.

Specifications for the main camera for the four smartphones used in this study.

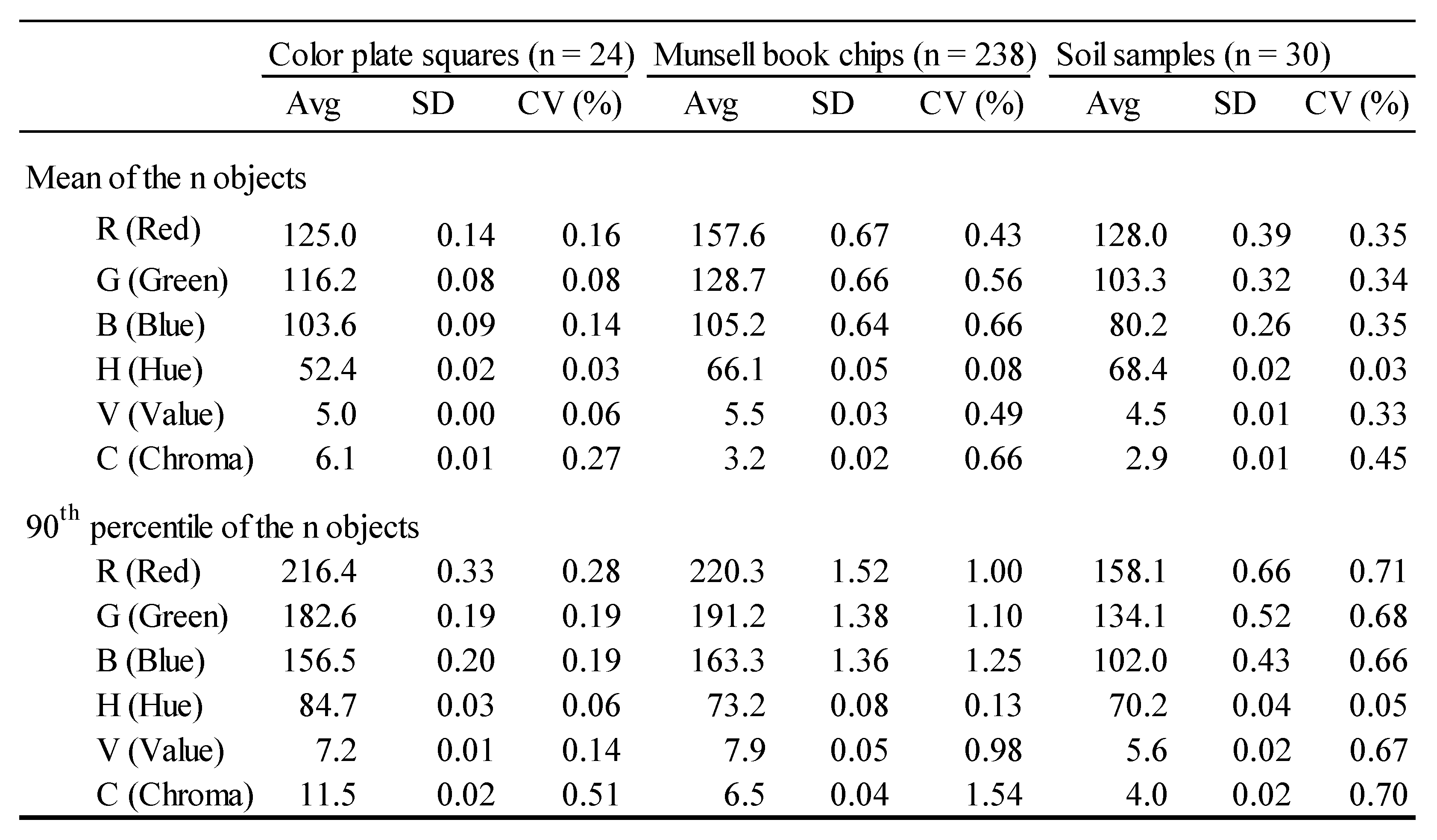

Table 2.

Means and 90th percentiles statistics (Avg = average/mean, SD = Standard Deviation, CV = coefficient of variance) of the three repeats among the number of objects within each object type.

Table 2.

Means and 90th percentiles statistics (Avg = average/mean, SD = Standard Deviation, CV = coefficient of variance) of the three repeats among the number of objects within each object type.

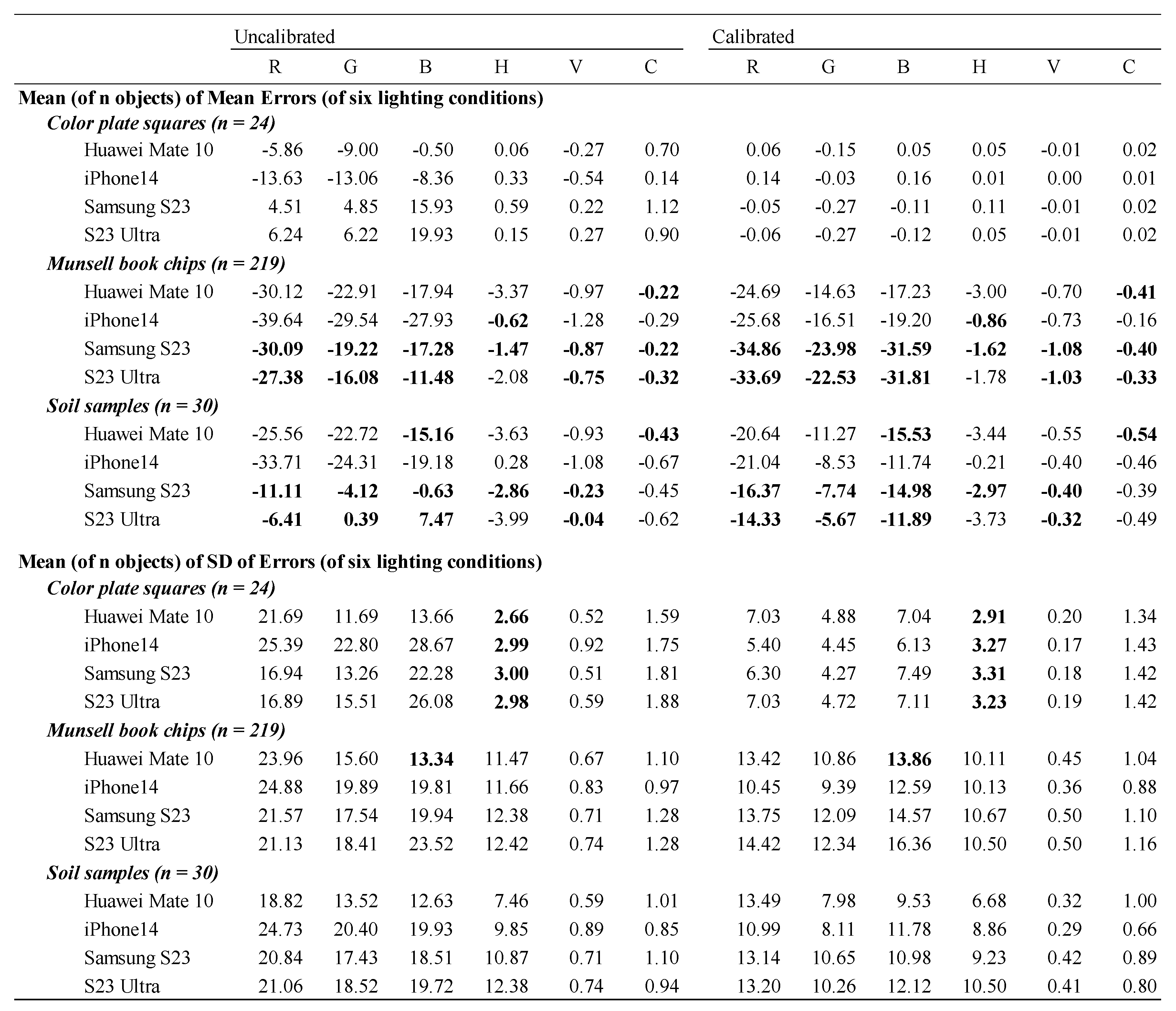

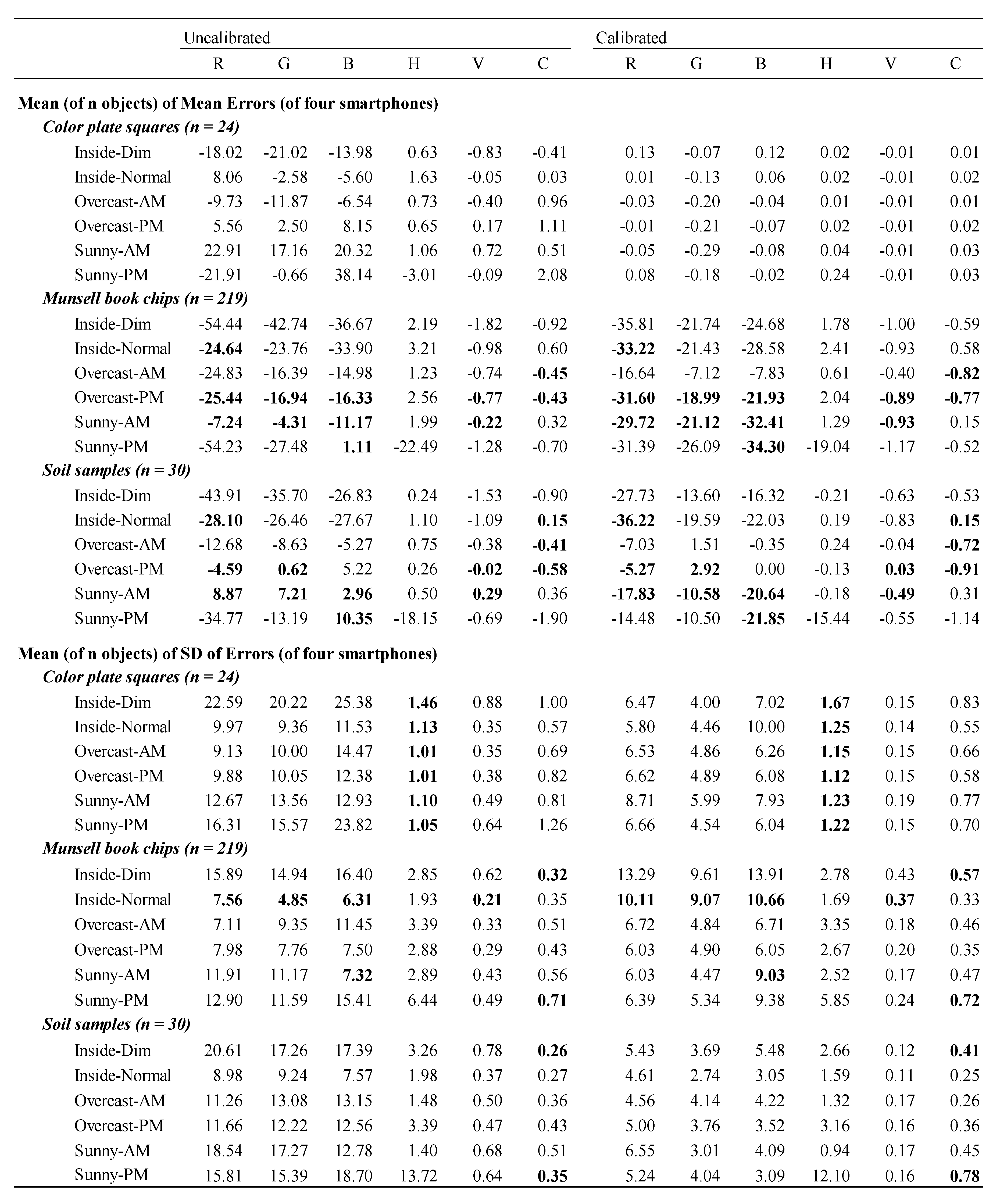

Table 3.

Means of the mean errors and standard deviation (SD) of errors for the six lighting conditions among the number of objects in each object type for the uncalibrated and clalibrated data of the six color parameters (R = Red, G = Green, B = Blue, H = Hue, V = Value and C = Chrome; bold numbers indicate the absolute values of the calibrated data are greater than those of the uncalibrated data).

Table 3.

Means of the mean errors and standard deviation (SD) of errors for the six lighting conditions among the number of objects in each object type for the uncalibrated and clalibrated data of the six color parameters (R = Red, G = Green, B = Blue, H = Hue, V = Value and C = Chrome; bold numbers indicate the absolute values of the calibrated data are greater than those of the uncalibrated data).

Table 4.

Means of the mean errors and standard deviation (SD) of errors for the four smartphones among the number of objects in each object type for the uncalibrated and calibrated data of the six color parameters (R = Red, G = Green, B = Blue, H = Hue, V = Value and C = Chrome; bold numbers indicate the absolute values of the calibrated data are greater than those of the uncalibrated data).

Table 4.

Means of the mean errors and standard deviation (SD) of errors for the four smartphones among the number of objects in each object type for the uncalibrated and calibrated data of the six color parameters (R = Red, G = Green, B = Blue, H = Hue, V = Value and C = Chrome; bold numbers indicate the absolute values of the calibrated data are greater than those of the uncalibrated data).