Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Brief Concept of Weyl Type Gravity

3. Cosmological Field Equations

4. Cosmological Solutions

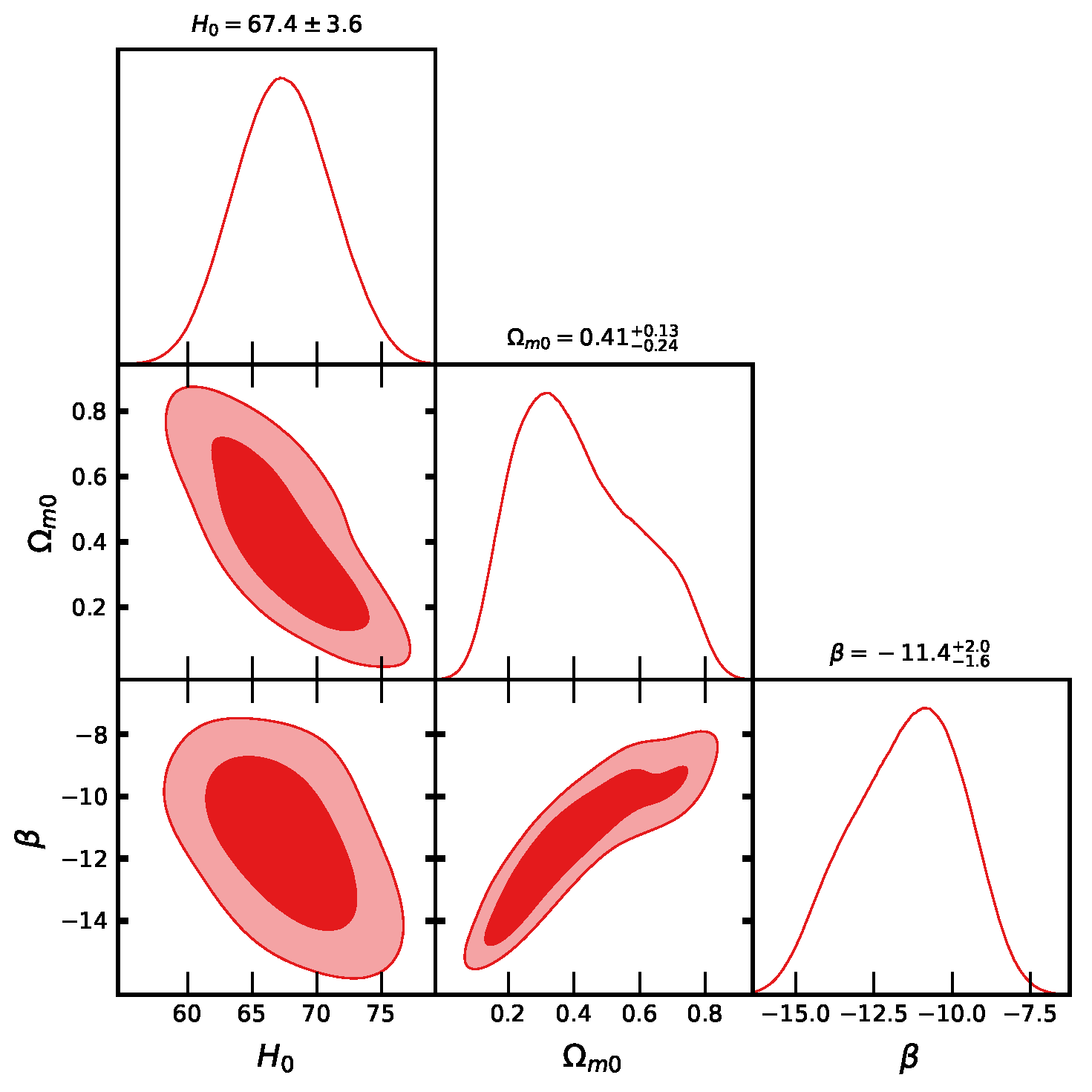

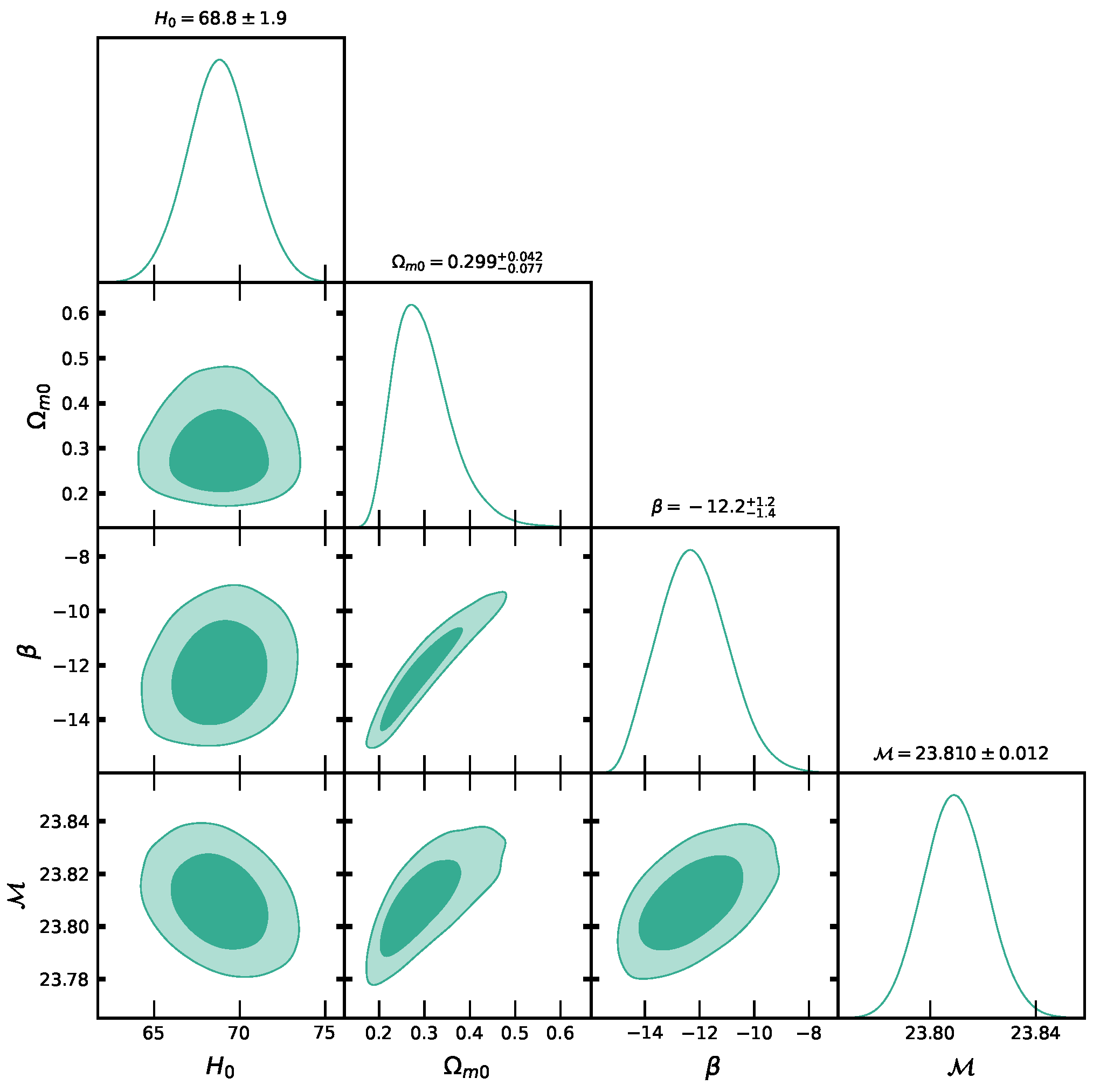

5. Cosmological Constraints

5.1. Hubble Data

5.2. Apparent Magnitude

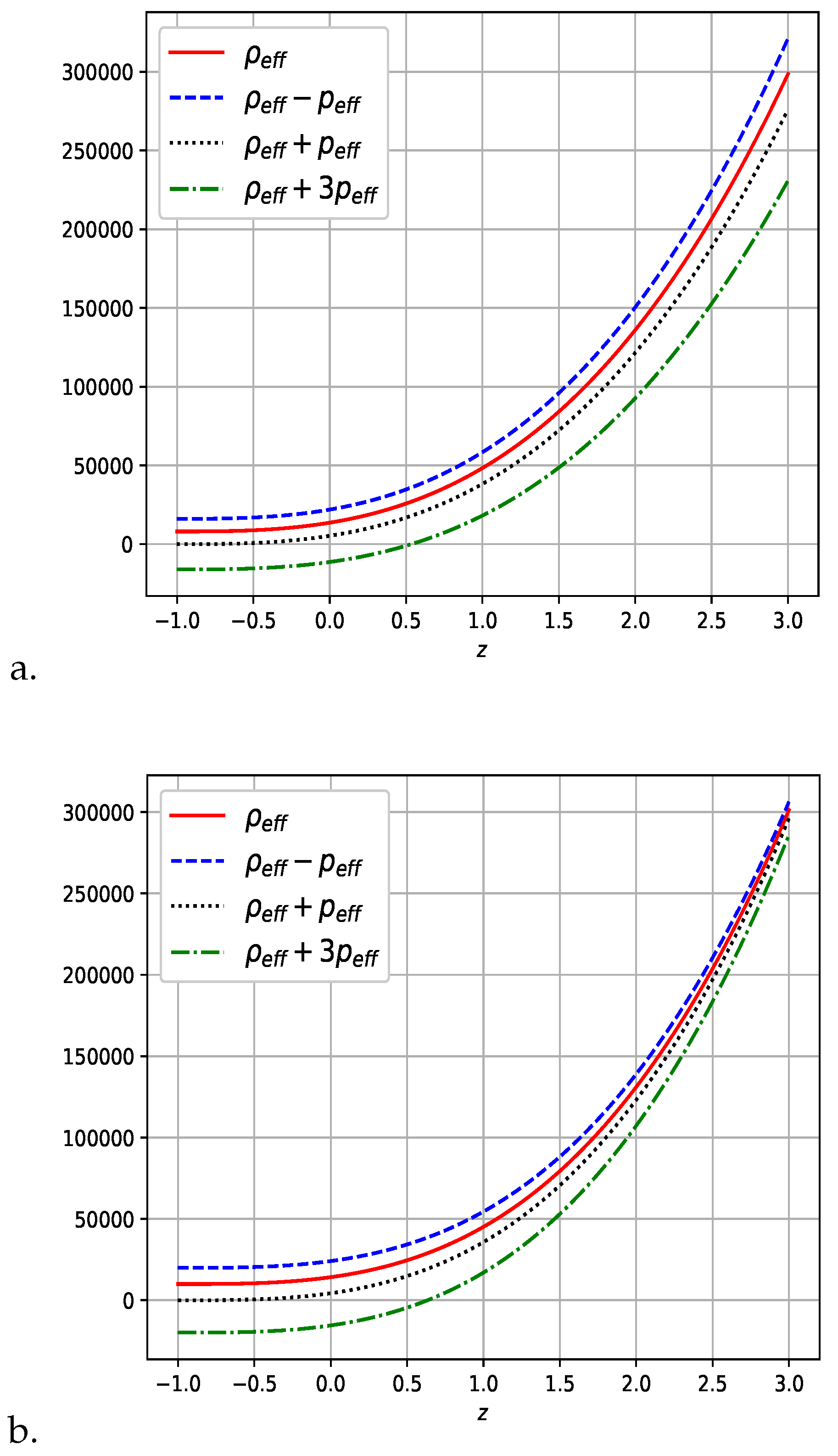

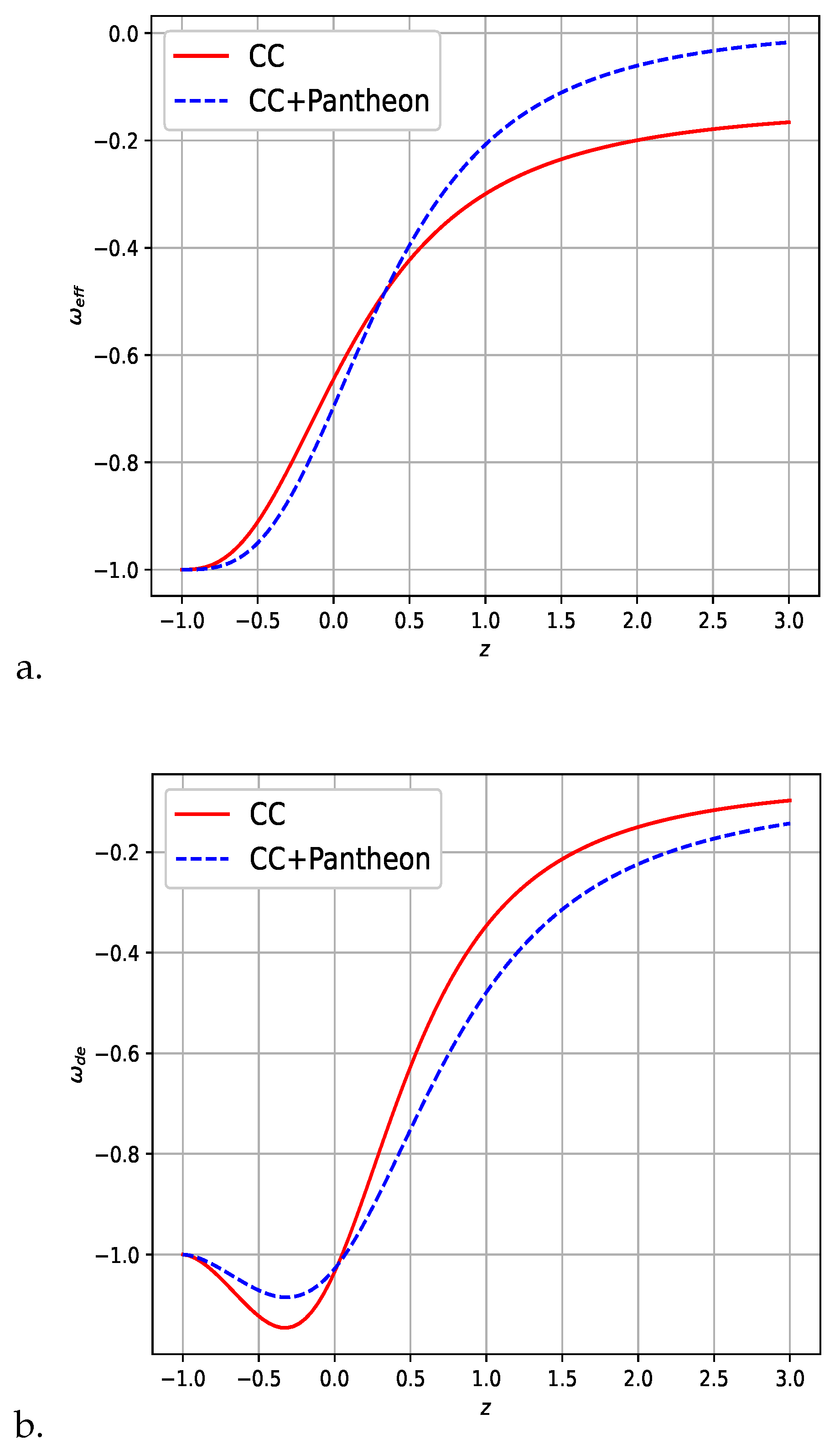

6. Result Discussions

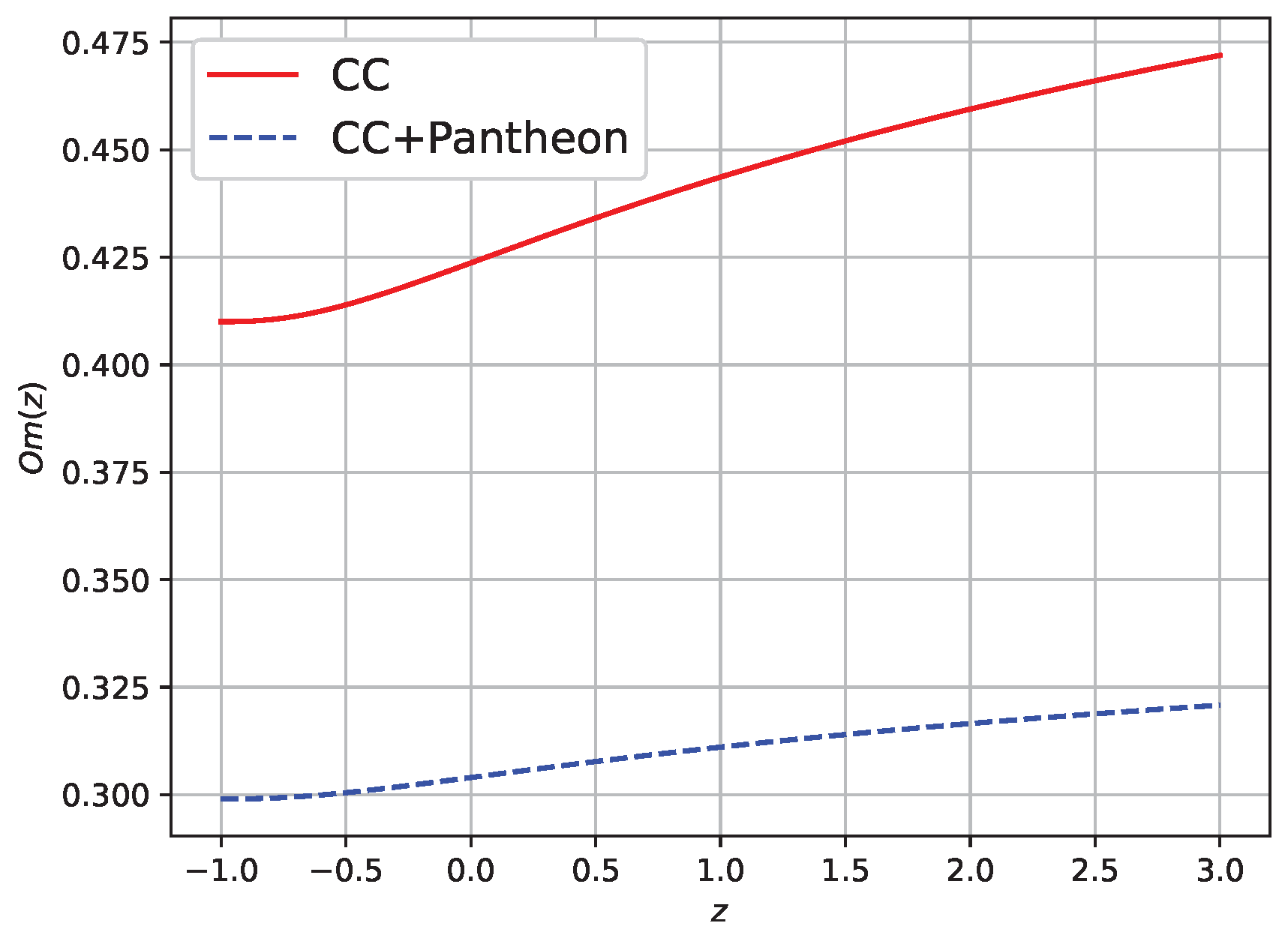

6.1. Om Diagnostic

7. Age of the Universe

8. Conclusions

- We identified a transit phase characterized by deceleration in the past and acceleration in the late time, exhibiting phantom behavior in the dark energy model, which aligns well with recent observations.

- We found the Hubble constant value as Km/s/Mpc, along with CC data, and Km/s/Mpc along with joint data CC+Pantheon.

- We found the matter energy density parameter value as , and effective EoS parameter with dark energy EoS parameter as along CC data and along joint data CC+Pantheon which are in good agreement with recent observations.

- We looked into the model parameters , , m, and that are non-vanishing. These show how different factors affect the Weyl-type gravity theory.

- We found that the current value of the deceleration parameter is along the CC data and along the joint data CC+Pantheon. Both of these values are negative , which means that the universe model is speeding up right now.

- The current age of the universe is determined to be billion years based on the CC dataset. When incorporating both the CC and Pantheon datasets, the estimated age is refined to billion years.

- We found that our derived model satisfied all energy conditions except SEC which produces accelerating phase of the expanding universe.

- The Om diagnostic analysis reveals the phantom dark energy behavior of the model.

Acknowledgments

References

- S. Perlmutter, G. Aldering, G. Goldhaber, et al., Measurements of Omega and Lambda from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae, Astrophys. J. 517 (1999) 565-586, [arXiv:astro-ph/9812133].

- A. G. Riess, A. V. Filippenko, P. Challis, et al., Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant, Astron. J. 116 (1998) 1009-1038, [arXiv:astro-ph/9805201].

- A.G. Riess et al., Type Ia Supernova Discoveries at z > 1 from the Hubble Space Telescope: Evidence for Past Deceleration and Constraints on Dark Energy Evolution*. Astophys. J. 2004, 607, 665–687. [CrossRef]

- S. Hanany et al., MAXIMA-1: A Measurement of the Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropy on angular scales of 10 arcminutes to 5 degrees, Astrophys. J, 545, L5 (2000).

- D.N. Spergel et al., Three-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Implications for Cosmology, Astrophys. J Suppl., 170, 377 (2007).

- E. Komatsu et al., Seven-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP*) Observations: Cosmological Interpretation, Astrophys. J. Suppl., 192, 18 (2011).

- D.J. Eisenstein et al., Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies, Astrophys. J., 633, 560-574 (2005).

- H.A. Buchdahl, Non-Linear Lagrangians and Cosmological Theory, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc., 150, 1 (1970).

- T. Harko, F.S.N. Lobo, S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, f(R,T) gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 024020.

- Cai, Yi-Fu and Capozziello, Salvatore and De Laurentis, Mariafelicia and Saridakis, Emmanuel N, f(T) teleparallel gravity and cosmology, Rep. Prog. Phys. 79(10) 106901 (2016). arXiv:1511.07586 [gr-qc].

- R. Ferraro, F. Fiorini, Modified teleparallel gravity: Inflation without an inflaton, Phys. Rev. D, 75, 084031 (2007).

- R. Myrzakulov, Accelerating universe from F(T) gravity, Eur. Phys. J. C, 71, 1752 (2011).

- S. Capozziello, V. F. Cardone, H. Farajollahi, A. Ravanpak, Cosmography in f(T) gravity, Phys. Rev. D, 84, 043527 (2011).

- J.B. Jimenez, L. Heisenberg, T. Koivisto, Coincident general relativity, Phys. Rev. D, 98, 044048 (2018).

- J. M. Nester and H. J. Yo, Symmetric teleparallel general relativity, Chin. J. Phys. 37 (1999) 113.

- Y. Xu, G. Li, T. Harko and S. D. Liang, f(Q,T) gravity, Eur. Phys. J. C 79 (2019) 708.

- S. Arora, S.K.J. Pacif, S. Bhattacharjee, f(Q,T) gravity models with observational constraints, P.K. Sahoo, Phys. Dark Univ., 30, 100664 (2020).

- S. Arora, A. Parida, P.K. Sahoo, Constraining effective equation of state in f(Q,T) gravity. Eur. Phys. J. C 2021, 81, 555. [CrossRef]

- R. Zia, D.C. Maurya, A.K. Shukla, Transit cosmological models in modified F(Q,T) gravity, Int. J. Geom. Meth. Mod. Phys., 18(04) 2150051 (2021). [CrossRef]

- E. Alvarez, S. Gonzalez-Martin, Weyl gravity revisited, J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys., 02, 011 (2017).

- C. Gomes, O. Bertolami, Nonminimally coupled Weyl gravity, Class. Quantum Grav. 2019, 36, 235016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, T. Harko, S. Shahidi, et al., Weyl type f(Q,T) gravity, and its cosmological implications, Eur. Phys. J. C 80 449 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J-Z. Yang, S. Shahidi, T. Harko, S-D. Liang, Geodesic deviation, Raychaudhuri equation, Newtonian limit, and tidal forces in Weyl-type f(Q,T) gravity, Eur. Phys. J. C, 81, 111 (2021).

- G. Gadbail, S. Arora, P.K. Sahoo, Power-law cosmology in Weyl-type f(Q,T) gravity, Eur. Phys. J. Plus, 136(10), 1040 (2021).

- J. T. Wheeler, Weyl gravity as general relativity, Phys. Rev. D, 90, 025027 (2014).

- R. Bhagat, S.A. Narawade, B. Mishra, Weyl type f(Q,T) gravity observational constrained cosmological models, Phys. Dark Univ. 41 (2023) 101250.

- G.N. Gadbail, S. Arora, P.K. Sahoo, Viscous cosmology in the Weyl-type f(Q,T) gravity. Eur. Phys. J. C 2021, 81, 1088. [CrossRef]

- M. Koussour, A model-independent method with phantom divide line crossing in Weyl-type f(Q,T) gravity, Chinese J. Phys. 83 (2023) 454-466.

- A.H.A. Alfedeel, M. Koussour, N. Myrzakulov, Probing Weyl-type f(Q,T) gravity: Cosmological implications and constraints, Astronomy and Computing 47 (2024) 100821.

- G. N. Gadbail, S. Arora, P. Kumar, P.K. Sahoo, Interaction of divergence-free deceleration parameter in Weyl-type f(Q,T) gravity. Chinese J. Phys. 2022, 79, 246–255. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Copeland, M. Sami and S. Tsujikawa, Dynamics of dark energy, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 15, 1753 (2006), [arXiv:hep-th/0603057].

- J. Simon, L. Verde, R. Jimenez, Constraints on the redshift dependence of the dark energy potential, Phys. Rev. D 71, 123001 (2005).

- G. S. Sharov, V. O. Vasiliev, How predictions of cosmological models depend on Hubble parameter data sets, Math. Model. Geom. 6, 1-20 (2018).

- K. Asvesta, L. Kazantzidis, L. Perivolaropoulos, C.G. Tsagas, Observational constraints on the deceleration parameter in a tilted universe. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 513, 2394–2406. [CrossRef]

- D.W. Hogg and D.F. Mackey, Data analysis recipes: Using Markov Chain Monte Carlo, The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 236 (2018) 18. [arXiv:1710.06068 [astro-ph.IM]].

- R. Jimenez and A. Loeb, Constraining Cosmological Parameters Based on Relative Galaxy Ages, ApJ 573 (2002) 37.

- G. Ellis, R. Maartens, M. MacCallum, Relativistic Cosmology (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012). [CrossRef]

- A. Conley et al., Supernova constrants and systemetic uncertainities from the first three years of the supernova legacy survey*, ApJ 192 (2011) 1.

- D. M. Scolnic et al., The Complete Light-curve Sample of Spectroscopically Confirmed SNe Ia from Pan-STARRS1 and Cosmological Constraints from the Combined Pantheon Sample, ApJ 859 (2018) 101.

- Dong Zhao, Yong Zhou, Zhe Chang, Anisotropy of the Universe via the Pantheon supernovae sample revisited, MNRS 486 (2019) 5679-5689.

- L. Kazantzidis, L. Perivolaropoulos, Hints of a local matter underdensity or modified gravity in the low z Pantheon data. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 102, 023520. [CrossRef]

- D. Sapone, et al., Is there any measurable redshift dependence on the SN Ia absolute magnitude? Phys. Dark Univ. 2021, 32, 100814. [CrossRef]

- L. Kazantzidis, H. Koo, S. Nesseris, L. Perivolaropoulos, A. Shafieloo, Hints for possible low redshift oscillation around the best-fitting ΛCDM model in the expansion history of the Universe, MNRS 501 (2021) 3421-3426.

- M. G. Dainotti et al., On the Hubble Constant Tension in the SNe Ia Pantheon Sample, ApJ 912 (2021) 150.

- M. G. Dainotti et al., On the Evolution of the Hubble Constant with the SNe Ia Pantheon Sample and Baryon Acoustic Oscillations: A Feasibility Study for GRB-Cosmology in 2030. Galaxies 2022, 10, 24. [CrossRef]

- G. Alestas, L. Kazantzidis, L. Perivolaropoulos, w-M phantom transition at zt≃0.1 as a resolution of the Hubble tension. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 103, 083517. [CrossRef]

- D. Camarena, V. Marra, On the use of the local prior on the absolute magnitude of Type Ia supernovae in cosmological inference, MNRS 504 (2021) 5164-5171.

- V. Marra, L. Perivolaropoulos, Rapid transition of Geff at zt≃0.01 as a possible solution of the Hubble and growth tensions. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, L021303. [CrossRef]

- G. Alestas, I. Antoniou L. Perivolaropoulos, Hints for a Gravitational Transition in Tully-Fisher Data, Universe 7 (2021) 366. [CrossRef]

- L. Perivolaropoulos, Is the Hubble crisis connected with the extinction of dinosaurs?, arXiv:2201.08997 [astro-ph.EP].

- D. C. Maurya, Late-time accelerating cosmological models in f(R,Lm,T)-gravity with observational constraints. Phys. Dark Universe 2024, 46, 101722. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Maurya, K. Yesmakhanova, R. Myrzakulov, G. Nugmanova, FLRW Cosmology in Metric-Affine F(R,Q) Gravity, Chinese Phys. C 48(12) 125101 (2024).

- D. C. Maurya, Transit dark energy models in Hoyle-Narlikar gravity with observational constraints. Phys. Dark Univ. 2025, 47, 101782. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Maurya, Constrained transit cosmological models in f(R,Lm,T)-gravity, Int. J. Geom. Meth. Mod. Phys. 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Maurya, Accelerating cosmological models in Hoyle-Narlikar gravity with observational constraints, Int. J. Geom. Meth. Mod. Phys., (2025). [CrossRef]

- A.R. Lalke, G.P. Singh, A. Singh, Cosmic dynamics with late-time constraints on the parametric deceleration parameter model. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2024, 139, 288. [CrossRef]

- S. Mandal, A. Singh, R. Chaubey, Late-time constraints on barotropic fluid cosmology. Phys. Lett. A 2024, 519, 129714. [CrossRef]

- A. Singh, S. Krishnannair, Affine EoS cosmologies: Observational and dynamical system constraints. Astronomy and Computing 2024, 47, 100827. [CrossRef]

- S. Capozziello, O. Farooq, O. Luongo, et al., Cosmographic bounds on the cosmological deceleration-acceleration transition redshift in f(R) gravity, Phys. Rev. D 90, 044016 (2014), [arXiv:1403.1421v1 [gr-qc]].

- S. Capozziello, O. Luongo, E. N. Saridakis, Transition redshift in f(T) cosmology and observational constraints, Phys. Rev. D 91 124037 (2015), [arXiv:1503.02832v2 [gr-qc]].

- S. Capozziello, P. K. S. Dunsby, O. Luongo, Model independent reconstruction of cosmological accelerated-decelerated phase, MNRAS 509 (2022) 5399-5415, [arXiv:2106.15579v2 [astro-ph.CO]].

- M. Muccino, O. Luongo, D. Jain, Constraints on the transition redshift from the calibrated Gamma-ray Burst Ep-Eiso correlation, MNRAS 523 (2023) 4938-4948, [arXiv:2208.13700v3 [astro-ph.CO]].

- A. C. Alfano, S. Capozziello, O. Luongo, et al., Cosmological transition epoch from gamma-ray burst correlations, (2024) [arXiv:2402.18967v1 [astro-ph.CO]].

- A. C. Alfano, C. Cafaro, S. Capozziello, et al., Dark energy-matter equivalence by the evolution of cosmic equation of state, Phys. Dark Univ. 42 101298 (2023), [arXiv:2306.08396v2 [astro-ph.CO]].

- M. Sharif and A. Ikram, Energy conditions in f(G,T) gravity, Eur. Phys. J. C 76 (2016) 640. arXiv:1608.01182v3 [gr-qc].

- S. Carroll, Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity, Addison Wesley (2004).

- R. Schoen and S. T. Yau, Proof of the positive mass theorem. II. Commun. Math. Phys. 1981, 79, 231. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Hawking and G. F. R. Ellis, The Large Scale Structure of Space-time, Cambridge University Press, (1973).

- V. Sahni, A. Shafieloo, A. A. Starobinsky, Two new diagnostics of dark energy. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 78, 103502. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Prior | CC | CC+Pantheon |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | |||

| - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).