1. Introduction

Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome represents a complex interplay of cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic disorders that significantly affect global health. These interconnected conditions are prevalent globally, with cardiovascular diseases (CVD) being the leading cause of death in the United States and the co-occurrence of diabetes and kidney impairment compounding health risks for millions.[

1] The rising incidence of obesity and metabolic disorders has exacerbated this crisis, highlighting the necessity for a comprehensive understanding of CKM disease and the therapeutic approaches to manage it effectively[

2]. The pathophysiology of CKM disease is complex, driven by shared mechanisms such as hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and neurohormonal activation, which contribute to a cycle of worsening renal and cardiovascular function[

3]. This syndrome encompasses a spectrum of conditions including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular diseases, which often coexist and exacerbate one another[

4].

A comprehensive approach to managing cardiometabolic kidney (CKM) disease incorporates a variety of pharmacological strategies aimed at slowing disease progression and reducing cardiovascular (CV) risk. The therapeutic interventions of well known risk factors for CKM include sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), and non-steroidal selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, like Finrenone. These medications are rapidly changing the armamentarium available to clinicians to address CKM and can be implemented in a varied set of clinical scenarios to mitigate overall progression of disease. Additionally, the risk factors for CKM continue to be further elucidated and newer therapeutic targets are being uncovered. Clinical data associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) as well as Lipoprotein-a (Lp(a)) have been linked to the development of worsening metabolic disease and clinical outcomes[

5,

6]. Novel technologies involving liver-specific TRβ agonists, RNA-based therapies, such as Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) and Small Interfering RNAs (siRNA) in addition to Interleukin 6 blockers, Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors, and angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3) are undergoing clinical trials and have the ability to drastically change the treatment options for CKM in the coming years. Finally, the current explosion of artificial intelligence has the potential to synthesize a patient's multitude of biomarkers, help forcast disease progression and potentially help individualize therapies.

This paper aims to bring awareness to the current fund of knowledge regarding known therapies in the treatment of CKM and help understand their mechanisms. Furthermore, we strive to discuss the importance of new therapeutic targets and the associated therapies that are showing promise in current clinical trials. The advancement in biomedical and artificial intelligence technology will play an important role in the future treatment of CKM.

2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive narrative literature review was conducted to evaluate the pathogenesis of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome using major databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The search employed a combination of keywords such as “Metabolic associated steatotic liver disease,” “non fibrotic Metabolic associated steatohepatitis,” “Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,” “Metabolic syndrome,” “Cardiovascular disease,” “Heart failure”, “Cardiorenal syndrome,” “Cardiometabolic syndrome,” “Chronic kidney disease”, and “antifibrotic therapies,” “goal directed medical therapy,” along with Boolean operators (AND, OR) and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms to refine results and ensure relevance.

Inclusion criteria encompassed studies, review articles, and meta-analyses focusing on the relationship between MASLD, MASH, NASH, NAFLD, Metabolic syndrome and Cardiovascular disease (CVD), Chronic kidney disease (CKD), diagnostic approaches, treatment modalities, and articles exploring the pathophysiological mechanisms linking cardiorenal and metabolic syndrome. Exclusion criteria included non-English publications, studies unrelated to metabolic syndrome, studies focusing solely on non-cardiac manifestations of metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease, conference abstracts, editorials, and opinion pieces.

The study selection process involved title and abstract screening to assess relevance, followed by full-text review to confirm alignment with study objectives. Data were systematically extracted using a predefined framework, and findings were summarized qualitatively, focusing on key themes such as pathophysiology, the impact of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome, morbidity and mortality, therapeutic targets and emerging research gaps and opportunities.

3. Current and Emerging Therapeutics

Current and emerging therapeutics for cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome target the complex interplay between cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic disorders. Established treatments include SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists like finerenone, which have demonstrated benefits in reducing cardiovascular events, slowing CKD progression, and improving metabolic parameters. Emerging therapies focus on novel targets such as Lipoprotein(a), inflammatory pathways, and hepatic fat accumulation. RNA-based therapies like antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNAs show promise in modulating gene expression related to lipid metabolism. Additionally, artificial intelligence is increasingly being leveraged to enhance risk prediction, treatment selection, and personalized management strategies in CKM syndrome.

3.1. Sodium Glucose Co-Transport 2 Inhibitors:

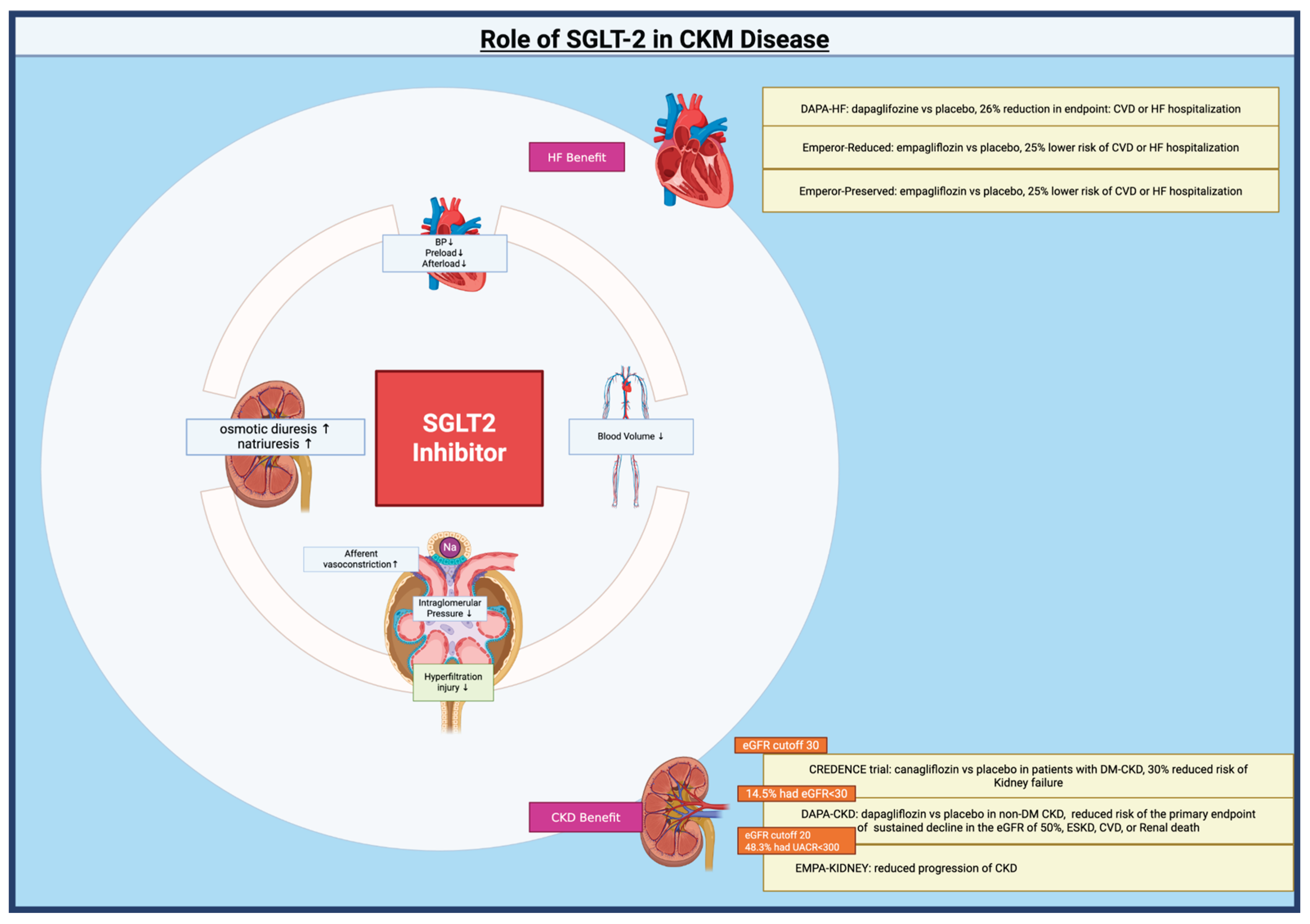

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors were originally developed for the management of type II diabetes mellitus. However, their use has now expanded into the cardiorenal and metabolic fields. This expansion is due to the growing recognition of the interconnections between diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). SGLT2 inhibitors provide cardiorenal protection through multiple, interrelated mechanisms that extend beyond glycemic control. The primary renal mechanism is the restoration of tubuloglomerular feedback via increased sodium delivery to the macula densa, leading to afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction, reduced intraglomerular pressure, and mitigation of hyperfiltration injury[

7,

8]. This effect is central to nephroprotection and is consistently highlighted in both clinical trials and mechanistic studies[

9]. SGLT2 inhibitors also induce osmotic diuresis and natriuresis, resulting in plasma volume contraction, lower blood pressure, and reduced cardiac preload and afterload, which are key contributors to heart failure benefit[

10]. Anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and antioxidative effects—mediated by reduced macrophage activation, decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines, and improved mitochondrial function—further contribute to both cardiac and renal protection[

11,

12].

Initial studies evaluating cardiovascular outcomes include DAPA-HF which found dapagliflozin resulted in a 26% reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization compared to placebo[

13]. The EMPEROR-Reduced trial further exemplified the benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors as there was a 25% lower combined risk of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization in patients receiving empagliflozin vs placebo[

14]. The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology both recognize these multifactorial mechanisms as the basis for the cardiorenal benefits observed in large outcome trials[

15]. In fact, SGLT2 inhibitors are now an essential component of goal directed medical therapy (GDMT) in the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)[

16]. The EMPEROR-preserved trial found that empagliflozin reduced the risk of the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure by 21% in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)[

17]. This finding was consistent amongst generally all subgroups; including those with or without diabetes[

17]. Ultimately, these findings have allowed for SGLT2 inhibitors to become a key player in the treatment of HFrEF/HFpEF. In addition, a meta-analysis of 11 trials involving SGLT2 inhibitors, which assessed rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), ultimately determined that the observed reduction in cardiovascular mortality is primarily attributable to a decrease in deaths related to heart failure and sudden cardiac death[

18]. Notably, the observed reduction in cardiovascular-related mortality was evident among patients exhibiting some degree of albuminuria, as these individuals experienced twice the event rate compared to those without albuminuria. This observation underscores the necessity to further investigate albuminuria in conjunction with the therapeutic benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors in the management of chronic kidney disease (CKD)[

18].

Albuminuria has been found to be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events, kidney failure, and death[

19]. The CREDENCE trial evaluated the role of SGLT2 inhibitors, more specifically Canagliflozin, in patients with diabetic CKD. They found that canagliflozin reduced the risk of kidney failure by 30% in this population[

19]. The role of SGLT2 inhibitors were further expanded as evidence supported their role in patients without diabetes mellitus and more advanced CKD. The DAPA-CKD trial showed a reduced risk of the primary endpoint of sustained decline in the estimated GFR of at least 50%, end-stage kidney disease, or death from renal or cardiovascular when compared to placebo[

20]. This study broadened the treatment population as the benefits of dapagliflozin were noted independent of diabetes mellitus. The study included 14.5% participants that had an eGFR less than 30 which was a contrast to the CREDENCE trial which had included a cut off of eGFR of 30[

19,

20]. The role of SGLT2 inhibitors in advanced CKD was further solidified as the EMPA-KIDNEY trial enrolled members with an eGFR as low as 20[

21]. This study also included a population with a wide range of levels of albuminuria with 48.3% with a urinary albumin to creatinine (UACR) less than 300. This group was also found to have a reduction in progression of CKD in comparison with placebo[

21]. This underscores the significance of SGLT2 inhibitors in managing various stages of CKD.

In summary, SGLT2 inhibitors are a cornerstone therapy for CKM syndrome, providing integrated cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic protection as endorsed by the American Heart Association, American Diabetes Association, and KDIGO. Their benefits extend beyond glycemic control and include reduction in progression of CKD, hospitalization for heart failure, major adverse cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality, with efficacy demonstrated in patients both with and without diabetes. [

Figure 1]

3.2. Glucagon-like-Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists:

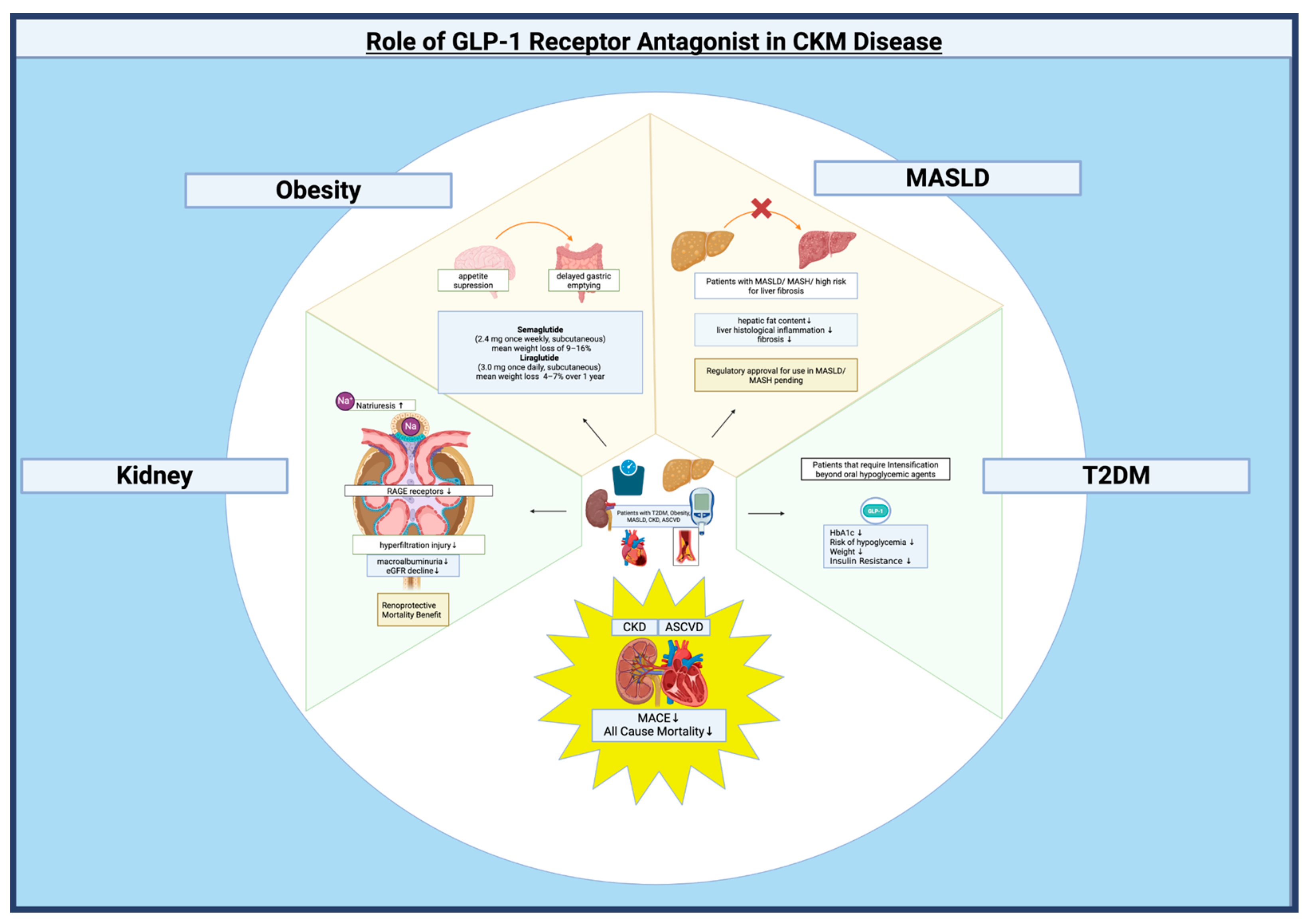

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) play a central role in the management of CKM syndrome, particularly in patients with type 2 diabetes, obesity, and/or chronic kidney disease (CKD). GLP-1RA were initially developed for treatment of type 2 diabetes. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) recommend GLP-1 RAs as a preferred first injectable therapy before insulin in most patients with T2D who require intensification beyond oral agents, due to their efficacy in lowering HbA1c, low risk of hypoglycemia, and favorable effects on weight[

22,

23]. These pharmacological agents effectively manage glycemic levels, facilitate weight reduction, and have been shown to substantially decrease major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and all-cause mortality in high-risk cohorts, particularly individuals with CKD and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)[

24,

25].

GLP-1 RAs are recommended as adjunctive therapy for adults with type 2 diabetes, overweight or obesity, and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), particularly when metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH) or high risk for liver fibrosis is present[

26]. Multiple phase II and phase III trials have highlighted the efficacy of GLP-1RAs in reducing hepatic fat content and liver histological inflammation and fibrosis among MASLD patients[

27,

28,

29]. Mechanistically, GLP-1 RAs exert their hepatic benefits primarily through indirect pathways, including weight reduction, improved insulin sensitivity, and decreased systemic inflammation, rather than direct action on hepatocytes. These agents also improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes, which is particularly relevant given the high cardiometabolic risk in MASLD/MASH[

30,

31]. Despite these advances, no GLP-1 RA is currently approved specifically for MASLD or MASH, and regulatory approval is pending further outcome data.

GLP-1RAs are now approved as adjunctive therapy in adults with T2D and chronic kidney disease (CKD) to improve glycemic control and potentially slow progression of kidney disease, with preference for agents with demonstrated cardiorenal benefit (liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide)[

25]. GLP-1RAs demonstrate a decrease in albuminuria and decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), with benefits observed even in patients with reduced eGFR (<60 mL/min/1.73 m²) in patients with T2D and CKD. A clinical trial focusing on diabetes management in patients with CKD indicates that GLP-1 receptor agonists reduce the likelihood of experiencing a composite endpoint related to kidney function deterioration including macroalbuminuria, eGFR decline, progression to kidney failure, or death from kidney disease[

25]. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in patients with chronic kidney disease treated with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists provided evidence of this, demonstrating improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes, as well as enhanced survival[

32].

Clinical guidelines highlight the substantial cardiovascular benefits of GLP-1RAs proving particularly valuable for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). These agents have demonstrated a robust capacity to reduce major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and all-cause mortality, making them a key consideration in managing this vulnerable population[

22,

23]. Beyond cardiovascular outcomes, GLP-1RAs exhibit several additional properties that contribute to their renoprotective effects. Their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant actions mitigate cellular damage and oxidative stress, while their natriuretic properties promote sodium excretion, aiding in fluid balance[

33]. Moreover, these drugs have been shown to reduce hyperfiltration, a maladaptive process that can accelerate kidney damage, and to downregulate receptors for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), thereby reducing inflammation triggered by these molecules[

34]. Taken together, these multifaceted mechanisms position GLP-1 receptor agonists as compelling therapeutic options for individuals with CKD, offering both cardiovascular protection and direct renoprotective benefits.

GLP-1 RAs are recommended as pharmacologic options for the management of obesity, particularly semaglutide and liraglutide, by the American Gastroenterological Association[

35]. GLP-1 RAs exert their weight-lowering effects primarily through central appetite suppression, delayed gastric emptying, and modulation of energy intake, with additional benefits on glycemic control, blood pressure, and lipid profiles[

36]. Building on these recommendations, robust clinical trials and meta-analytic data further clarify the role of GLP-1 receptor agonists as effective agents for weight loss in adults with obesity, regardless of diabetes status. Randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews consistently demonstrate that GLP-1 RAs, particularly semaglutide (2.4 mg once weekly, subcutaneous) and liraglutide (3.0 mg once daily, subcutaneous), produce clinically meaningful reductions in body weight, with semaglutide achieving mean weight loss of 9–16% and liraglutide 4–7% over 1 year, and a substantial proportion of patients achieving ≥10% weight loss. These effects are superior to those of first-generation anti-obesity drugs and lifestyle modification alone[

37].

Overall, GLP-1 receptor agonists are generally preferred in CKM syndrome when weight loss, glycemic control, and ASCVD risk reduction are primary goals,are now established as a cornerstone pharmacologic therapy for obesity management, with demonstrated efficacy for weight loss, metabolic improvement, and potential cardiovascular benefit, as supported by multiple high-quality studies and consensus from major professional societies[

22,

38,

39]. [

Figure 2]

3.3. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist:

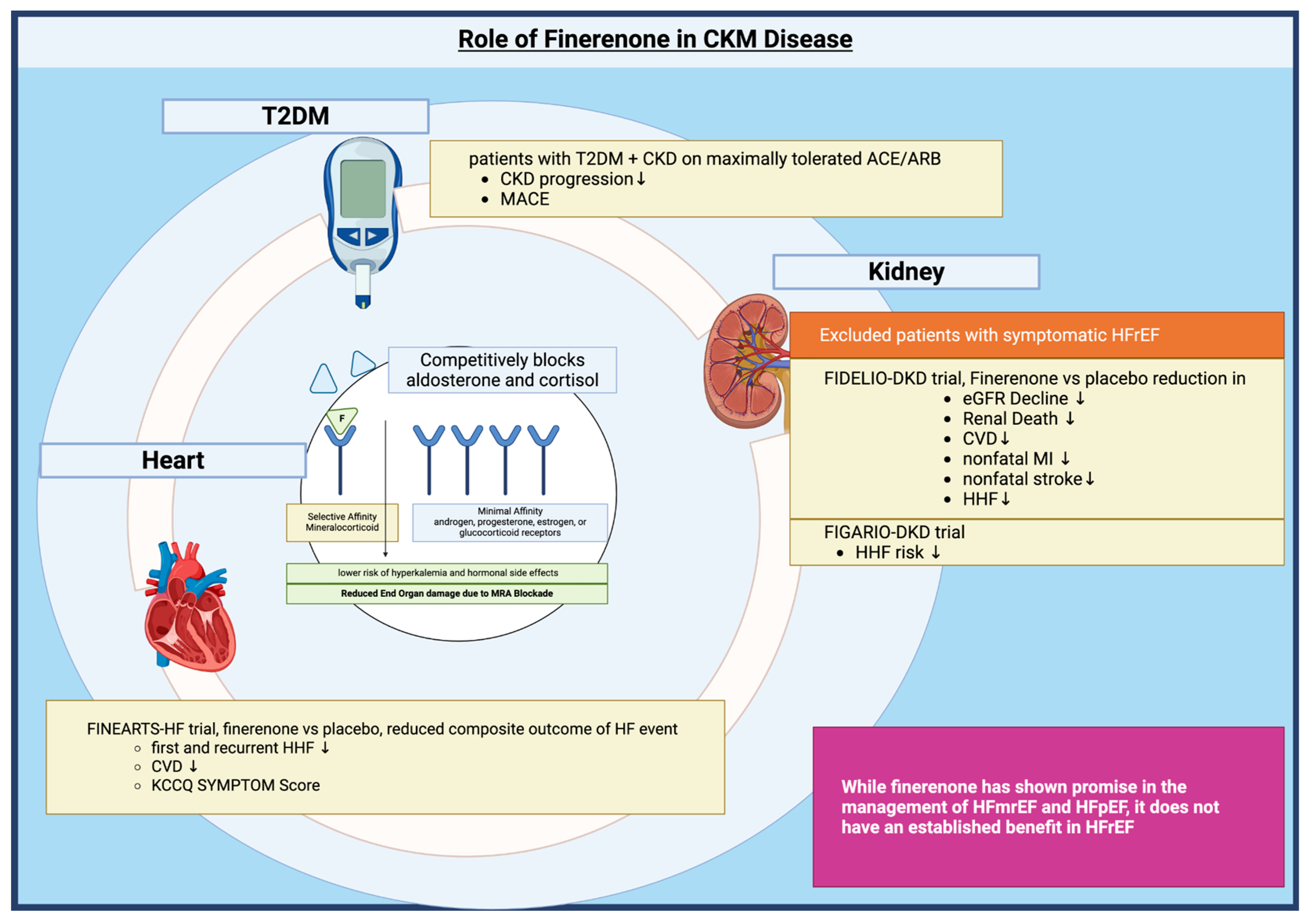

Finerenone is a nonsteroidal, selective antagonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). Its mechanism of action involves competitively blocking the binding of aldosterone and cortisol to the MR, thereby inhibiting MR-mediated gene transcription[

40]. Finerenone exhibits high potency and selectivity for the MR, with minimal affinity for androgen, progesterone, estrogen, or glucocorticoid receptors, distinguishing it from steroidal MRAs such as spironolactone and eplerenone. Compared to these agents, finerenone demonstrates a more balanced tissue distribution between the heart and kidney and exerts more potent anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects, with a lower risk of hyperkalemia and hormonal side effects[

41]. This blockade occurs in both epithelial tissues (such as the kidney, where it reduces sodium reabsorption) and non epithelial tissues (including the heart and vasculature), leading to reduced inflammation and fibrosis which are the key drivers of cardiorenal disease progression in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and type 2 diabetes[

42].

The over activation of the mineralocorticoid receptor has been implicated in end organ damage primarily through promotion of inflammation and fibrosis on top of known sodium retention leading to hypertension[

43]. There is well established data on the role of mineralocorticoid receptor benefits in the treatment of HFrEF but use has been limited by side effects such as hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury; especially seen in patients with concomitant advanced CKD[

43]. Finerenone through its selective binding to these receptors results in a more targeted approach compared to steroidal MRAs, potentially leading to fewer side effects while maintaining efficacy[

41]. A few key trials have highlighted both cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with T2DM. The FIDELIO-DKD trial looked at the primary outcome of kidney failure, a decrease in baseline eGFR by at least 40%, or death from renal causes and a secondary outcome of death from CV causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure[

44]. Barkis et al.[

44] found there was a statistically significant decrease in both primary and secondary outcomes in those treated with Finerenone compared with placebo. The FIGARIO-DKD trial published the following year showed Finerenone reduced the risk of hospitalization for heart failure (HHF) and other cardiovascular events. The study included patients with stage 1-4 CKD, including those with moderately increased albuminuria[

45].

Finerenone provides benefit in heart failure primarily by reducing the risk of worsening heart failure events and cardiovascular death in patients with heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction (HFmrEF/HFpEF)[

46,

47]. In the FINEARTS-HF trial, finerenone, significantly lowered the rate of a composite outcome of total worsening heart failure events (including first and recurrent unplanned hospitalizations or urgent visits for heart failure) and death from cardiovascular causes compared to placebo (rate ratio 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74–0.95; P=0.007) over a median follow-up of 32 months[

46]. The benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups, and the reduction in events was observed for both components of the primary outcome. Finerenone also led to a modest improvement in patient-reported health status, as measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) total symptom score, but did not significantly improve NYHA functional class or kidney composite outcomes in this population[

48].

While finerenone has shown promise in the management of HFmrEF and HFpEF, it does not have an established benefit in HFrEF. The pivotal clinical trials of finerenone, including FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD, specifically excluded patients with symptomatic HFrEF, and the observed cardiovascular benefit, including reduction in heart failure hospitalizations, was demonstrated in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes, not in those with established HFrEF[

49]. Ongoing and future trials may clarify the role of finerenone in HFrEF, but as of now, finerenone should not be considered a substitute for established MRAs in HFrEF[

40].

Finerenone has a defined role in the management of CKM syndrome, particularly in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD. In this population, finerenone has been shown to reduce the risk of CKD progression and major adverse cardiovascular events, especially heart failure hospitalizations, when added to maximally tolerated renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade (ACE inhibitor or ARB)[

4]. The American Diabetes Association and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) consensus, as well as the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI), recommend finerenone as an adjunctive, risk-based therapy for patients with T2D, CKD, and albuminuria (UACR >30 mg/g), particularly when residual risk persists despite optimized RAS inhibition and, when possible, SGLT2 inhibitor therapy[

25,

50]. [

Figure 3]

3.4. Thyroid Receptor Beta Agonists:

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a significant global health concern, affecting over 30% of the adult population[

6]. Characterized by the accumulation of fat in the liver due to metabolic dysfunctions such as insulin resistance (IR) and chronic low-grade inflammation, MASLD is associated with a heightened risk of cardiovascular complications[

51]. In fact, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality among affected individuals[

51]. While MASLD remains a broad category, MASH represents a more severe form, characterized by inflammation, liver damage, and an increased risk of fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer[

52]. The clinical implications of MASLD extend beyond hepatic health, emphasizing the importance of a holistic understanding of its cardiovascular consequences.

Management of MASLD primarily revolves around lifestyle modifications and pharmacological interventions. One promising therapeutic approach involves liver-specific TRβ agonists, such as GC-1 (sobetirome), KB-2115 (eprotirome), and MGL-3196 (resmetirom). Hepatocytes express thyroid hormone receptor beta (THR-β), whose activation by T3 regulates several key metabolic functions, including mitochondrial fatty acid uptake and β-oxidation, mitochondrial biogenesis, upregulation of hepatic LDL receptor expression, and reduction in circulating LDL cholesterol[

53]. These agents have shown encouraging results in reducing hepatic steatosis and improving lipid profiles. However, clinical development has encountered setbacks. Phase 2 trials for sobetirome have not yet been conducted, and a phase 3 trial for eprotirome was discontinued after animal studies revealed cartilage damage in dogs. Additionally, a significant increase in liver enzymes was observed during the study period[

53]. Resmetirom has emerged as the first Food and Drug Administration-approved drug for effective management of MASLD[

54].

Resmetirom is a selective TRβ agonist with 28-fold greater affinity for TRβ in the liver. This reduces the creation of new fats, increases the breakdown of fatty acids, and offers benefits against inflammation and scarring[

55]. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of Resmetirom in treating non-cirrhotic MASH with moderate to advanced fibrosis. In a randomized, double-blind Phase 2 trial (NCT02912260), patients with MASH (fibrosis stages F1–F3) received either resmetirom (80 mg/day, n=78) or placebo (n=38) for 36 weeks. Resmetirom significantly reduced hepatic fat at both 12 and 36 weeks compared with placebo[

55]. Following Phase 2 results, MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 phase 3 trial (NCT04197479) was conducted. The MAESTRO-NASH trial (NCT03900429) showed that resmetirom (80 mg and 100 mg) achieved 26% and 30% NASH resolution rates, respectively, versus 10% with placebo, significantly reduced LDL cholesterol, and had mild gastrointestinal side effects. Both 52-week trials were randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled[

54]. Younossi et al.[

56] assessed health-related quality of life (HRQL) in 125 NASH patients treated with resmetirom (n=84) or placebo (n=41) over 36 weeks. Resmetirom significantly improved HRQL scores compared to placebo[

56].

Resmetirom demonstrated a favorable safety profile in Phase 3 trials, with mostly mild to moderate gastrointestinal symptoms[

6]. Serious adverse event rates were comparable between resmetirom and placebo, and no drug-induced liver injury was reported. Cancer rates, major cardiovascular events, bone fractures, and significant BMD changes were not increased with resmetirom[

6]. Resmetirom was approved in the US in 2024 for noncirrhotic NASH with moderate to advanced fibrosis, alongside diet and exercise, based on its safety profile in trials. It reduces liver fat, lowers liver enzyme levels, improves liver fibrogenesis indicators, reduces liver stiffness, and improves cardiovascular profile by lowering serum lipid levels, including LDL cholesterol[

57]. Ongoing investigations are assessing the applicability of this drug in pediatric, adolescent, and adult patients diagnosed with cirrhosis. Commercially distributed as Rezdiffra, it is presented in tablet formulations of 60 mg, 80 mg, and 100 mg strengths. The prescribed daily dose is 80 mg for adult individuals weighing below 100 kg and 100 mg for those with a weight of 100 kg or greater[

58].

Currently, five ongoing clinical trials are evaluating resmetirom (NCT02912260, NCT04197479, NCT03900429, NCT04951219, NCT04643795)[

59]. Further longitudinal investigations and post-marketing surveillance are essential to confirm the long-term safety of resmetirom and to detect any unforeseen off-target effects.

3.5. Lipoprotein-a (Lp(a))

Lipoprotein-a (Lp(a)) is increasingly recognized as a significant risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and heart failure (HF)[

60]. The American Heart Association's recent scientific statement highlights the causal role of elevated Lp(a) in ASCVD, a conclusion supported by extensive observational, genetic, and mechanistic evidence accumulated over decades[

60]. Unlike traditional lipids, Lp(a) levels are predominantly genetically determined and remain stable throughout an individual's lifespan, rendering them a promising candidate for early cardiovascular risk stratification[

60]. Potential mechanisms linking Lp(a) to heart failure (HF) include its proinflammatory and prothrombotic effects, as well as its role in promoting coronary atherosclerosis[

61,

62]. Some studies suggest that the relationship between Lp(a) and HF may be partially mediated by myocardial infarction and aortic valve stenosis, although independent pathways are also likely involved[

61]. The CASABLANCA study, which assessed patients undergoing coronary angiography, identified a link between elevated Lp(a) and oxidized phospholipids with progression toward symptomatic HF, independent of coronary artery disease (CAD) severity[

5]. A meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies corroborates that higher genetically predicted Lp(a) levels are significantly associated with an increased risk of HF, suggesting a potential causal relationship[

63]. These findings are consistent with other large cohort studies that have identified elevated Lp(a) as a risk factor for both the development of HF and adverse outcomes, including mortality, in individuals with established heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)[

61,

62].

Notable complexities exist in the relationship between Lp(a) and cardiovascular risk. Research indicates that elevated Lp(a) was predictive of heart failure (HF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) specifically within White participant cohorts, potentially indicative of genetic or environmental factors influencing Lp(a) risk manifestation[

64]. Further research is warranted to identify these specific modifiers and elucidate the mechanisms through which they influence Lp(a)'s impact on HF and HFpEF development in diverse populations. Furthermore, a more pronounced impact of elevated Lp(a) has been observed in individuals with diabetes mellitus[

65]. This heightened risk in the diabetic population underscores the critical need for Lp(a) screening within the context of comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment in these individuals. Identifying individuals with both diabetes and elevated Lp(a) may allow for more targeted and intensified preventive strategies within the CKM framework.

While statin therapy has become a cornerstone in the management of hypercholesterolemia and the subsequent reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), leading to a significant decrease in the risk of ASCVD) its efficacy does not extend to Lp(a)[

66]. Compelling evidence, notably from the landmark JUPITER trial, has revealed that even in individuals receiving effective statin treatment and achieving target LDL-C levels, elevated Lp(a) concentrations continue to pose an independent and significant cardiovascular risk. This finding underscores a critical unmet clinical need for therapeutic interventions specifically designed to target and lower Lp(a) levels[

66]. In this context, antisense oligonucleotides (e.g., APO(a)LRx) represent a promising new class of agents, with early-phase clinical trials demonstrating potent, selective reductions in Lp(a) levels with good safety profiles[

67]. The future of preventive cardiology and heart failure management may be significantly impacted by these Lp(a)-lowering therapies. If subsequent large-scale clinical trials can definitively establish a direct correlation between the reduction of Lp(a) levels achieved with agents like APO(a)LRx and a tangible decrease in the incidence of heart failure events or a demonstrable improvement in overall survival rates, these targeted treatments would represent a major breakthrough.

The available data strongly indicates that Lipoprotein(a) is not merely a residual risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, but a significant and potentially modifiable factor in the development and progression of heart failure. Routine measurement of Lipoprotein(a) may be justified in clinical practice, particularly for patients with unexplained heart failure, premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, or a family history of early-onset cardiovascular disease. As innovative therapeutic approaches continue to be developed, the identification and targeted treatment of elevated Lipoprotein(a) levels may become a fundamental component of individualized cardiovascular prevention strategies.

3.6. Phase 3 Trial Drugs for CKM Syndrome

New therapies are in the pipeline for Cardio-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome. Contemporary management includes lifestyle modifications and traditional pharmacotherapies. Newer therapies rapidly expanded the options available in the armamentarium against CKM syndrome.

RNA-based therapies, such as Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) and Small Interfering RNAs (siRNA) in addition to Interleukin 6 blockers, Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors, and angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3) Inhibition, are currently the face of such therapies[

68]. RNA-based therapies focus on modulating gene expression or RNA interference. Volanesorsen, an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), specifically targets hepatic APOC3 mRNA, leading to its cleavage and degradation. This process reduces plasma apolipoprotein C-III levels. Apolipoprotein C-III acts as an inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity and also impedes an LPL-independent pathway for the clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Consequently, reducing apolipoprotein C-III effectively decreases plasma triglycerides, thereby mitigating the risk of pancreatitis in individuals with Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (FCS)[

69,

70]. siRNAs, such as Plozasiran, are double-stranded RNAs that engage with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), leading to the degradation (silencing) of the targeted mRNA[

68]. Plozasiran, when used against APOC3 mRNA, achieves the same outcome as Volanesorsen, though it operates through a different mechanism.

Inclisiran is a siRNA that targets the hepatic synthesis of proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9 (PCSK9), significantly lowering LDL cholesterol levels[

71]. As established previously, higher levels of Lipoprotein(a), Lp(a) have an association with increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease[

60]. It consists of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoprotein that is covalently bound to apolipoprotein(a). Apolipoprotein(a) gene (LPA) controls the expression of Lp(a). Olpasiran is a siRNA that disrupts the expression of LPA, resulting in lower levels of apolipoprotein(a) synthesis and the final product, Lp(a). Phase III trials are currently underway to assess the effects of MACE reduction with Olpasiran in those with a history of ASCVD and Lp(a)≥ 200 nmol/L[

72].

These novel therapeutic approaches targeting different aspects of cardiovascular disease pathophysiology highlight the ongoing advancements in the field. While Olpasiran focuses on reducing Lp(a) levels, Ziltivekimab addresses the inflammatory component of atherosclerosis, both of which are significant risk factors in cardiovascular disease progression[

73]. The fully human monoclonal antibody, Ziltivekimab, targets IL-6 ligand and has been shown to reduce hsCRP, a biomarker of inflammation and thrombosis, in a Phase II trial[

73]. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) facilitates the transfer of cholesterol from high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles, thereby increasing the concentration of the latter two. Previous attempts at CETP inhibition had failed until the arrival of Obicetrapib, a CETP inhibitor that has been shown to lower LDL-C effectively in combination with high-intensity statins[

74,

75].

Angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3) is an inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase and endothelial lipase, resulting in increased concentration of triglycerides and LDL-C. Another fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits ANGPTL3 has resulted in a significant reduction of LDL-C levels in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia with a mechanism independent of LDL receptors. Finally, emerging RNA-based therapies now target hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, cardiac remodeling, cardiomyocyte regeneration, AKI, and diabetic nephropathy[

68].. The development of these targeted therapies underscores the importance of addressing multiple pathways in the management of cardiovascular risk, especially in high-risk populations such as those with CKD.

3.7. Role of Artificial Intelligence

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in CKM management has the potential to revolutionize patient care by providing personalized treatment plans based on individual risk profiles using large datasets to identify multifaceted patterns. Recent studies show that innovations in AI have further enhanced cardiovascular medicine including drug design, procession therapeutics and personalised inference from clinical trials. A study focusing on a machine learning model for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) by Zhu H., et al[

76] states that AI-driven models can predict risk of CVD in patients with CKD by evaluating electronic health records and recognizing essential predictive factors like age, medical history and biochemical markers that support clinical decision making in CKM disease. While its predictive capability is extremely beneficial considering the high incidence of CVD in CKD patients, AI also plays a role in optimizing management of CKM diseases. Its ability to integrate multisource data sets, to further enable disease risk prediction and population categorization allows streamlined management of multiple independent factors like blood glucose, blood pressure, nutrition, etc which are crucial in patients with CKM diseases.

AI provides comprehensive data-informed evidence that guides clinical decision-making and enhances patient care. These systems can integrate diverse data sources including electronic health records, laboratory results, imaging studies, and even genetic information to create a holistic view of a patient's condition. By applying machine learning algorithms to this comprehensive dataset, AI can identify subtle patterns and risk factors that may not be immediately apparent to human clinicians, potentially leading to earlier interventions and more personalized treatment plans. The American Heart Association's recent recommendations highlight the critical role that AI can play in advancing CKM[

77]. By developing and implementing sophisticated predictive algorithms, healthcare providers can more accurately forecast disease progression, treatment responses, and potential complications[

77].

Furthermore, AI-powered decision support tools can assist clinicians in navigating complex treatment decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations tailored to individual patient profiles, thus aligning with the growing emphasis on precision medicine in nephrology. Machine learning aids in early intervention through diagnosis of acute kidney injury prior to biochemical changes, identification of modifiable risk factors that cause CKD progression and accurate diagnosis of renal tumors[

78].

Therefore, AI can play an increasingly important role in the diagnosis, risk stratification, and management of CKM syndrome. AI models, particularly those using machine learning and deep learning, can integrate multimodal data including clinical, laboratory, imaging, and omics data to improve early detection of metabolic syndrome, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease, all of which are core components of CKM syndrome[

79,

80,

81]. Despite these advances, challenges remain regarding data quality, model interpretability, workflow integration, and regulatory oversight, which must be addressed to ensure safe and effective clinical implementation[

82,

83].

Table 1.

Overview of selected publications defining CKM syndrome and major meta-analyses evaluating therapies relevant to CKM components (Cardiovascular Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease, Type 2 Diabetes/Metabolic issue).

Table 1.

Overview of selected publications defining CKM syndrome and major meta-analyses evaluating therapies relevant to CKM components (Cardiovascular Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease, Type 2 Diabetes/Metabolic issue).

| Paper Name |

Authors* |

Year |

Study Type |

Population Studied |

Key Findings |

Inclusion Criteria / Indication |

Outcome Trial Results (with p-value if available) |

Side Effect Profile* |

| Defining CKM Syndrome |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association |

AHA (Ndumele CE, et al.)[77] |

2023 |

Presidential Advisory / Scientific Statement |

General US population; focus on individuals with/at risk for CVD, CKD, T2D, Obesity. |

Defines CKM syndrome as a health disorder linking obesity, diabetes, CKD, and CVD. Proposes staging (0-4) based on risk factors and disease presence. Emphasizes prevention, integrated care, and addressing social determinants of health (SDOH). |

N/A (Definitional document) |

N/A (Definitional document) |

N/A (Recommends therapies like SGLT2i/GLP-1 RA for appropriate stages) |

| An Overview of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome |

Ferdinand KC et al.[84] |

2024 |

Review |

General overview of CKM syndrome patients. |

Reinforces CKM definition, staging. Highlights role of excess/dysfunctional adipose tissue, inflammation, oxidative stress. Notes impact of SDOH and additional risk factors (chronic inflammation, family history, sleep/mental health). |

N/A (Review) |

N/A (Review) |

N/A (Review) |

| Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) syndrome: A state-of-the-art review |

Sebastian SA et al.[3] |

2024 |

Review |

Epidemiological data from NHANES and AHA reports, highlighting prevalence across different demographics |

CKM syndrome involves interconnected metabolic, cardiovascular, and renal diseases. Key mechanisms include insulin resistance, RAAS activation, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and lipotoxicity. The syndrome progresses through five stages, from no risk factors to symptomatic cardiovascular disease with kidney failure. Management focuses on screening, early intervention, and multidisciplinary care to reduce adverse outcomes. |

N/A (Review) |

N/A (Review) |

1. GLP-1 RA: Primarily causes gastrointestinal issues like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

2. SGLT2 inhibitors: Increase the risk of genital and urinary tract infections

3. Finerenone: May lead to hyperkalemia |

| SGLT2 Inhibitor Trials (Meta-Analyses) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with stage 3/4 CKD: A meta-analysis |

Li N, et al.[85] |

2022 |

Meta-analysis |

11 RCTs; 27,823 patients with stage 3/4 CKD. |

SGLT2i significantly reduced primary CV outcomes (CV death/HHF) across stage 3a, 3b, and 4 CKD, irrespective of T2D or HF status. |

Patients with stage 3/4 CKD included in RCTs comparing SGLT2i vs placebo. |

Reduced primary CV outcome risk by 26% (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.69–0.80, p<0.001 inferred). Consistent benefit across CKD stages (p interaction = 0.71). |

General Class Effects: Genitourinary infections, potential for volume depletion/hypotension, rare risk of DKA. |

| Effect of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular Outcomes Across Various Patient Populations |

Usman, et al.[86] |

2023 |

Meta-analysis |

13 RCTs; >90,000 patients with HF, T2D, CKD or combinations. |

SGLT2i consistently reduced the composite of first HHF or CV death (~23-24%) across HF, T2D, and CKD populations and combinations. Also reduced CV death (~12-16%) and HHF (~29-32%) separately. |

Patients with HF, T2D, or CKD in large RCTs comparing SGLT2i vs placebo. |

Reduced HHF/CV Death by ~24% (HR ~0.76-0.77, p<0.001 inferred). Reduced CV Death by ~12-16% (p<0.001 inferred). Reduced HHF by ~29-32% (p<0.001 inferred). |

General Class Effects: Genitourinary infections, potential for volume depletion/hypotension, rare risk of DKA.

|

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Trials (Meta-Analyses) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kidney and Cardiovascular Outcomes Among Patients With CKD Receiving GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials |

Chen et al.[32] |

2024 |

Meta-analysis |

12 RCTs; 17,996 participants with baseline eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2. |

GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced composite kidney outcome, risk of >30/40/50% eGFR decline, all-cause mortality, and composite CV outcomes in patients with CKD. |

Adults with varying kidney function (incl. CKD eGFR<60) in RCTs comparing GLP-1 RA vs control. |

Reduced composite kidney outcome (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.77-0.94, P=0.001). Reduced all-cause mortality (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.60-0.98, P=0.03). Reduced composite CV outcomes (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.74-0.99, P=0.03). |

General Class Effects: Gastrointestinal side effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), injection site reactions, rare risk of pancreatitis/thyroid tumors. |

| Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on kidney and cardiovascular disease outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

Badve et al.[87] |

2024 |

Meta-analysis (incl. SELECT trial) |

11 RCTs; 85,373 participants (mostly T2D, one trial non-diabetic obesity/CVD). |

GLP-1 RAs reduced composite kidney outcome, kidney failure, MACE, and all-cause death in T2D patients. Similar effects when non-diabetic SELECT trial included. |

Participants (mostly T2D, one non-diabetic obesity/CVD trial) in large RCTs comparing GLP-1 RA vs placebo. |

Reduced composite kidney outcome by 18% (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73-0.93). Reduced kidney failure by 16% (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.72-0.99). Reduced MACE by 13% (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.81-0.93). Reduced all-cause death by 12% (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.83-0.93). |

Higher treatment discontinuation due to AEs (RR 1.51). No difference in serious AEs vs placebo. |

Table 2.

The indications, mechanisms of action, outcomes, and adverse effects of phase III drugs for CKM.

Table 2.

The indications, mechanisms of action, outcomes, and adverse effects of phase III drugs for CKM.

| Drugs |

Phase 3 Trials |

Principal investigator |

Indication |

MOA |

Outcome |

Adverse effects |

| Volanesorsen |

NCT02211209 |

Gaudet et al.[58] |

Hypertriglyceridemia, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (FCS) |

ASO targeting ApoC-III |

77% decrease in mean triglyceride levels(TG). |

Thrombocytopenia and injection site reaction. |

| Olezarsen |

NCT04568434 |

Stroes et al.[88] |

Hypertriglyceridemia, Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), FCS |

Gal- NAc3 conjugated ASO targeting ApoC-III |

Reduction in the fasting triglyceride level of at least 70% at 6 months. |

Abdominal pain, and diarrhea. |

| Mipomersen |

NCT00794664 |

McGowan et al.[89] |

Hypercholesterolemia, Dyslipidemias |

Induces ApoB100 degradation |

Reduced LDL-C by 36% |

Injection site reactions, flu-like symptoms. |

| Pelacarsen |

NCT05305664 |

Novartis Pharmaceuticals[90] |

ACS, Hyperlipoproteinemia |

ASO targeting Lp(a) |

Pending results |

Mild injection site reactions. |

| Plozasiran |

NCT06347016 |

Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals[91] |

Mixed dyslipidemia, Hypertriglyceridemia, FCS |

siRNA targeting apoC-III mRNA |

Currently recruiting. |

Worsening glycemic control, diarrhea, urinary tract infection. |

| Inclisiran |

NCT03399370 |

Ray KK et al.[92] |

Coronary artery disease (CAD), Familial hypercholesterolemia (FHS), ACS |

siRNA targeting PCSK9 |

50% reduction in low density lipoprotein (LDL) |

Injection site reactions. |

| Lepodisiran |

NCT06292013 |

Ferdinand et al.[93] |

Cardiovascular disorders (CVD), Metabolic disorders |

siRNA targeting ApoA |

Currently recruiting. |

Injection site reactions, hypersensitivity reactions, hepatobiliary adverse events. |

| Olpasiran |

NCT05581303 |

UCSD Health[94] |

CAD, elevated Lp(a) |

siRNA targeting Lp(a) |

Pre-recruitment stage |

Injection-site reactions |

| Ziltivekimab |

NCT05021835 |

Ridker et al.[95] |

CVD, Chronic kidney disease (CKD) |

IL-6 Blocker |

Currently recruiting |

Injection-site reactions |

| Obicetrapib |

NCT05142722 |

Ditmarsch et al.[96] |

Heterozygous FHS, CAD |

CETP Inhibitors |

Completed, pending publication of results. |

Nausea, urinary tract infection, and headache. |

| Evinacumab |

NCT05611528 |

Gaudet et al.[97] |

Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia |

ANGPTL3 Inhibition |

47.1% reduction in LDL |

Nasopharyngitis, influenza-like illness, headache. |

4. Conclusions

CKM syndrome represents a critical intersection of cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic diseases, necessitating an integrated approach to treatment. Current therapies, including SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and Finerenone, demonstrate promising advancements in addressing CKM complexities. Additionally, RNA-based therapies and AI-driven healthcare innovations hold potential for personalized disease management. Understanding CKM syndrome’s pathophysiology, risk factors, and evolving therapeutic landscape is essential for improving outcomes and reducing global disease burden. Future research should focus on refining treatment strategies, optimizing multi-organ protection, and leveraging technological advancements to enhance patient care and clinical decision-making in CKM-related diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B. and K.V.; methodology, I.B., K.V.; writing–original draft preparation, I.B.; writing—sections, K.P., J.M., T.U., A.K., A.S., P.G., J.K.; visualization-–figures and tables, I.B., A.B., T.U.; writing—review and editing, I.B., E.T., S.A., V.M.; supervision, K.V.; project administration, K.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Scispace and Open Evidence for the purposes of literature review. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADA |

American Diabetes Association |

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ACEi |

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor |

| ARB |

Angiotensin receptor blocker |

| ASO |

Antisense Oligonucleotides |

| ANGPTL3 |

angiopoietin-like 3 |

| ASCVD |

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| CETP |

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein |

| CKM |

Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| CKD |

Chronic kidney disease |

| EASD |

European Association for the Study of Diabetes |

| GLP1-RA |

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists |

| HFPEF |

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFREF |

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| KDIGO |

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| KDOQI |

National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative |

| LDL |

Low density lipoprotein |

| MACE |

Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MASLD |

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| PCSK9 |

Proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9 |

| RAS |

Renin angiotensin system |

| SGLT2i |

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors |

| TRβ |

Thyroid receptor beta |

References

- Marassi M, Fadini GP. The cardio-renal-metabolic connection: a review of the evidence. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023; 22: 195. [CrossRef]

- Schnell O, Almandoz J, Anderson L, Barnard-Kelly K, Battelino T, Blüher M, Busetto L, Catrinou D, Ceriello A, Cos X, Danne T, Dayan CM, Del Prato S, Fernández-Fernández B, Fioretto P, Forst T, Gavin JR, Giorgino F, Groop P-H, Harsch IA, Heerspink HJL, Heinemann L, Ibrahim M, Jadoul M, Jarvis S, Ji L, Kanumilli N, Kosiborod M, Landmesser U, Macieira S, Mankovsky B, Marx N, Mathieu C, McGowan B, Milenkovic T, Moser O, Müller-Wieland D, Papanas N, Patel DC, Pfeiffer AFH, Rahelić D, Rodbard HW, Rydén L, Schaeffner E, Spearman CW, Stirban A, Tacke F, Topsever P, Van Gaal L, Standl E. CVOT summit report 2024: new cardiovascular, kidney, and metabolic outcomes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2025; 24: 187. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian SA, Padda I, Johal G. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) syndrome: A state-of-the-art review. Curr Probl Cardiol 2024; 49: 102344. [CrossRef]

- Ndumele CE, Neeland IJ, Tuttle KR, Chow SL, Mathew RO, Khan SS, Coresh J, Baker-Smith CM, Carnethon MR, Després J-P, Ho JE, Joseph JJ, Kernan WN, Khera A, Kosiborod MN, Lekavich CL, Lewis EF, Lo KB, Ozkan B, Palaniappan LP, Patel SS, Pencina MJ, Powell-Wiley TM, Sperling LS, Virani SS, Wright JT, Rajgopal Singh R, Elkind MSV, Rangaswami J, on behalf of the American Heart Association. A Synopsis of the Evidence for the Science and Clinical Management of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023; 148: 1636–1664. [CrossRef]

- Januzzi JL, Van Kimmenade RRJ, Liu Y, Hu X, Browne A, Plutzky J, Tsimikas S, Blankstein R, Natarajan P. Lipoprotein(a), Oxidized Phospholipids, and Progression to Symptomatic Heart Failure: The CASABLANCA Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2024; 13: e034774. [CrossRef]

- Petta S, Targher G, Romeo S, Pajvani UB, Zheng M, Aghemo A, Valenti LVC. The first MASH drug therapy on the horizon: Current perspectives of resmetirom. Liver Int 2024; 44: 1526–1536. [CrossRef]

- Heerspink HJL, Perkins BA, Fitchett DH, Husain M, Cherney DZI. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus: Cardiovascular and Kidney Effects, Potential Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Circulation 2016; 134: 752–772. [CrossRef]

- Di Costanzo A, Esposito G, Indolfi C, Spaccarotella CAM. SGLT2 Inhibitors: A New Therapeutical Strategy to Improve Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Kidney Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24: 8732. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Correa JI, Correa-Rotter R. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors Mechanisms of Action: A Review. Front Med 2021; 8: 777861. [CrossRef]

- Vallon V, Verma S. Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Kidney and Cardiovascular Function. Annu Rev Physiol 2021; 83: 503–528. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Hocher C-F, Shen L, Krämer BK, Hocher B. Reno- and cardioprotective molecular mechanisms of SGLT2 inhibitors beyond glycemic control: from bedside to bench. Am J Physiol-Cell Physiol 2023; 325: C661–C681. [CrossRef]

- Salvatore T, Galiero R, Caturano A, Rinaldi L, Di Martino A, Albanese G, Di Salvo J, Epifani R, Marfella R, Docimo G, Lettieri M, Sardu C, Sasso FC. An Overview of the Cardiorenal Protective Mechanisms of SGLT2 Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23: 3651. [CrossRef]

- McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Anand IS, Bělohlávek J, Böhm M, Chiang C-E, Chopra VK, De Boer RA, Desai AS, Diez M, Drozdz J, Dukát A, Ge J, Howlett JG, Katova T, Kitakaze M, Ljungman CEA, Merkely B, Nicolau JC, O’Meara E, Petrie MC, Vinh PN, Schou M, Tereshchenko S, Verma S, Held C, DeMets DL, Docherty KF, Jhund PS, Bengtsson O, Sjöstrand M, Langkilde A-M. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1995–2008. [CrossRef]

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Januzzi J, Verma S, Tsutsui H, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Kimura K, Schnee J, Zeller C, Cotton D, Bocchi E, Böhm M, Choi D-J, Chopra V, Chuquiure E, Giannetti N, Janssens S, Zhang J, Gonzalez Juanatey JR, Kaul S, Brunner-La Rocca H-P, Merkely B, Nicholls SJ, Perrone S, Pina I, Ponikowski P, Sattar N, Senni M, Seronde M-F, Spinar J, Squire I, Taddei S, Wanner C, Zannad F. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1413–1424. [CrossRef]

- Rangaswami J, Bhalla V, De Boer IH, Staruschenko A, Sharp JA, Singh RR, Lo KB, Tuttle K, Vaduganathan M, Ventura H, McCullough PA, On behalf of the American Heart Association Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Cardiorenal Protection With the Newer Antidiabetic Agents in Patients With Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020; 142. [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, Deswal A, Drazner MH, Dunlay SM, Evers LR, Fang JC, Fedson SE, Fonarow GC, Hayek SS, Hernandez AF, Khazanie P, Kittleson MM, Lee CS, Link MS, Milano CA, Nnacheta LC, Sandhu AT, Stevenson LW, Vardeny O, Vest AR, Yancy CW. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022; 145. [CrossRef]

- Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, Böhm M, Brunner–La Rocca H-P, Choi D-J, Chopra V, Chuquiure-Valenzuela E, Giannetti N, Gomez-Mesa JE, Janssens S, Januzzi JL, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Merkely B, Nicholls SJ, Perrone SV, Piña IL, Ponikowski P, Senni M, Sim D, Spinar J, Squire I, Taddei S, Tsutsui H, Verma S, Vinereanu D, Zhang J, Carson P, Lam CSP, Marx N, Zeller C, Sattar N, Jamal W, Schnaidt S, Schnee JM, Brueckmann M, Pocock SJ, Zannad F, Packer M. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: 1451–1461. [CrossRef]

- Patel SM, Kang YM, Im K, Neuen BL, Anker SD, Bhatt DL, Butler J, Cherney DZI, Claggett BL, Fletcher RA, Herrington WG, Inzucchi SE, Jardine MJ, Mahaffey KW, McGuire DK, McMurray JJV, Neal B, Packer M, Perkovic V, Solomon SD, Staplin N, Vaduganathan M, Wanner C, Wheeler DC, Zannad F, Zhao Y, Heerspink HJL, Sabatine MS, Wiviott SD. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes: A SMART-C Collaborative Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2024; 149: 1789–1801. [CrossRef]

- Neuen BL, Ohkuma T, Neal B, Matthews DR, De Zeeuw D, Mahaffey KW, Fulcher G, Li Q, Jardine M, Oh R, Heerspink HL, Perkovic V. Effect of Canagliflozin on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes across Different Levels of Albuminuria: Data from the CANVAS Program. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 30: 2229–2242. [CrossRef]

- Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou F-F, Mann JFE, McMurray JJV, Lindberg M, Rossing P, Sjöström CD, Toto RD, Langkilde A-M, Wheeler DC. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1436–1446. [CrossRef]

- The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med 2023; 388: 117–127. [CrossRef]

- Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, Gabbay RA, Green J, Maruthur NM, Rosas SE, Del Prato S, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, Rossing P, Tankova T, Tsapas A, Buse JB. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2022. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2022; 45: 2753–2786. [CrossRef]

- Blonde L, Umpierrez GE, Reddy SS, McGill JB, Berga SL, Bush M, Chandrasekaran S, DeFronzo RA, Einhorn D, Galindo RJ, Gardner TW, Garg R, Garvey WT, Hirsch IB, Hurley DL, Izuora K, Kosiborod M, Olson D, Patel SB, Pop-Busui R, Sadhu AR, Samson SL, Stec C, Tamborlane WV, Tuttle KR, Twining C, Vella A, Vellanki P, Weber SL. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan—2022 Update. Endocr Pract 2022; 28: 923–1049. [CrossRef]

- Abdelmalek MF, Harrison SA, Sanyal AJ. The role of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2024; 26: 2001–2016. [CrossRef]

- De Boer IH, Khunti K, Sadusky T, Tuttle KR, Neumiller JJ, Rhee CM, Rosas SE, Rossing P, Bakris G. Diabetes management in chronic kidney disease: a consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2022; 102: 974–989. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee, ElSayed NA, McCoy RG, Aleppo G, Bajaj M, Balapattabi K, Beverly EA, Briggs Early K, Bruemmer D, Cusi K, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Ekhlaspour L, Fleming TK, Garg R, Khunti K, Lal R, Levin SR, Lingvay I, Matfin G, Napoli N, Pandya N, Parish SJ, Pekas EJ, Pilla SJ, Pirih FQ, Polsky S, Segal AR, Jeffrie Seley J, Stanton RC, Verduzco-Gutierrez M, Younossi ZM, Bannuru RR. 4. Comprehensive Medical Evaluation and Assessment of Comorbidities: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025; 48: S59–S85. [CrossRef]

- Loomba R, Hartman ML, Lawitz EJ, Vuppalanchi R, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Yoneda M, Behling C, Cummings OW, Tang Y, Brouwers B, Robins DA, Nikooie A, Bunck MC, Haupt A, Sanyal AJ. Tirzepatide for Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatohepatitis with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2024; 391: 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Sanyal AJ, Bedossa P, Fraessdorf M, Neff GW, Lawitz E, Bugianesi E, Anstee QM, Hussain SA, Newsome PN, Ratziu V, Hosseini-Tabatabaei A, Schattenberg JM, Noureddin M, Alkhouri N, Younes R. A Phase 2 Randomized Trial of Survodutide in MASH and Fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2024; 391: 311–319. [CrossRef]

- Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, Linder M, Okanoue T, Ratziu V, Sanyal AJ, Sejling A-S, Harrison SA. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1113–1124. [CrossRef]

- Alkhouri N, Charlton M, Gray M, Noureddin M. Alkhouri, Naim, Michael Charlton, Meagan Gray, and Mazen Noureddin. “The Pleiotropic Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis: A Review for Gastroenterologists.” Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 34, no. 3 (March 4, 2025): 169–95. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2025; 34: 169–195. [CrossRef]

- Yabut JM, Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor-based Therapeutics for Metabolic Liver Disease. Endocr Rev 2023; 44: 14–32. [CrossRef]

- Chen J-Y, Hsu T-W, Liu J-H, Pan H-C, Lai C-F, Yang S-Y, Wu V-C. Kidney and Cardiovascular Outcomes Among Patients With CKD Receiving GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Am J Kidney Dis 2025; 85: 555-569.e1. [CrossRef]

- Trevella P, Ekinci EI, MacIsaac RJ. Potential kidney protective effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. Nephrol Carlton Vic 2024; 29: 457–469. PMID: 39030739. [CrossRef]

- Sourris KC, Ding Y, Maxwell SS, Al-Sharea A, Kantharidis P, Mohan M, Rosado CJ, Penfold SA, Haase C, Xu Y, Forbes JM, Crawford S, Ramm G, Harcourt BE, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Advani A, Murphy AJ, Timmermann DB, Karihaloo A, Knudsen LB, El-Osta A, Drucker DJ, Cooper ME, Coughlan MT. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling modifies the extent of diabetic kidney disease through dampening the receptor for advanced glycation end products-induced inflammation. Kidney Int 2024; 105: 132–149. PMID: 38069998. [CrossRef]

- Grunvald E, Shah R, Hernaez R, Chandar AK, Pickett-Blakely O, Teigen LM, Harindhanavudhi T, Sultan S, Singh S, Davitkov P. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on Pharmacological Interventions for Adults With Obesity. Gastroenterology 2022; 163: 1198–1225. [CrossRef]

- Moiz A, Filion KB, Tsoukas MA, Yu OHy, Peters TM, Eisenberg MJ. Mechanisms of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist-Induced Weight Loss: A Review of Central and Peripheral Pathways in Appetite and Energy Regulation. Am J Med 2025; 138: 934–940. [CrossRef]

- Taha MB, Yahya T, Satish P, Laird R, Agatston AS, Cainzos-Achirica M, Patel KV, Nasir K. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists: A Medication for Obesity Management. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2022; 24: 643–654. [CrossRef]

- Ansari HUH, Qazi SU, Sajid F, Altaf Z, Ghazanfar S, Naveed N, Ashfaq AS, Siddiqui AH, Iqbal H, Qazi S. Efficacy and Safety of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Parameters in Individuals With Obesity and Without Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocr Pract 2024; 30: 160–171. [CrossRef]

- Xie W, Hong Z, Li B, Huang B, Dong S, Cai Y, Ruan L, Xu Q, Mou L, Zhang Y. Influence of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on fat accumulation in patients with diabetes mellitus and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. J Diabetes Complications 2024; 38: 108743. [CrossRef]

- Pandey AK, Bhatt DL, Cosentino F, Marx N, Rotstein O, Pitt B, Pandey A, Butler J, Verma S. Non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in cardiorenal disease. Eur Heart J 2022; 43: 2931–2945. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal R, Kolkhof P, Bakris G, Bauersachs J, Haller H, Wada T, Zannad F. Agarwal, Rajiv, Peter Kolkhof, George Bakris, Johann Bauersachs, Hermann Haller, Takashi Wada, and Faiez Zannad. “Steroidal and Non-Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Cardiorenal Medicine.” European Heart Journal 42, no. 2 (January 7, 2021): 152–61. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: 152–161. [CrossRef]

- González-Juanatey JR, Górriz JL, Ortiz A, Valle A, Soler MJ, Facila L. Cardiorenal benefits of finerenone: protecting kidney and heart. Ann Med 2023; 55: 502–513. [CrossRef]

- Georgianos PI, Agarwal R. The Nonsteroidal Mineralocorticoid-Receptor-Antagonist Finerenone in Cardiorenal Medicine: A State-of-the-Art Review of the Literature. Am J Hypertens 2023; 36: 135–143. [CrossRef]

- Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, Kolkhof P, Nowack C, Schloemer P, Joseph A, Filippatos G. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 2219–2229. [CrossRef]

- Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Bakris GL, Rossing P, Joseph A, Kolkhof P, Nowack C, Schloemer P, Ruilope LM. Cardiovascular Events with Finerenone in Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: 2252–2263. [CrossRef]

- Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Vaduganathan M, Claggett B, Jhund PS, Desai AS, Henderson AD, Lam CSP, Pitt B, Senni M, Shah SJ, Voors AA, Zannad F, Abidin IZ, Alcocer-Gamba MA, Atherton JJ, Bauersachs J, Chang-Sheng M, Chiang C-E, Chioncel O, Chopra V, Comin-Colet J, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gajos G, Goland S, Goncalvesova E, Kang S, Katova T, Kosiborod MN, Latkovskis G, Lee AP-W, Linssen GCM, Llamas-Esperón G, Mareev V, Martinez FA, Melenovský V, Merkely B, Nodari S, Petrie MC, Saldarriaga CI, Saraiva JFK, Sato N, Schou M, Sharma K, Troughton R, Udell JA, Ukkonen H, Vardeny O, Verma S, Von Lewinski D, Voronkov L, Yilmaz MB, Zieroth S, Lay-Flurrie J, Van Gameren I, Amarante F, Kolkhof P, Viswanathan P. Finerenone in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2024; 391: 1475–1485. [CrossRef]

- Ismahel H, Docherty KF. The role of finerenone in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2025; : S1050173825000659. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Henderson AD, Talebi A, Atherton JJ, Chiang C-E, Chopra V, Comin-Colet J, Kosiborod MN, Kerr Saraiva JF, Claggett BL, Desai AS, Kolkhof P, Viswanathan P, Lage A, Lam CSP, Senni M, Shah SJ, Rohwedder K, Voors AA, Zannad F, Pitt B, Vaduganathan M, Jhund PS, Solomon SD, McMurray JJV. Effect of Finerenone on the KCCQ in Patients With HFmrEF/HFpEF. J Am Coll Cardiol 2025; 85: 120–136. [CrossRef]

- Filippatos G, Anker SD, Agarwal R, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, Bakris GL, Tasto C, Joseph A, Kolkhof P, Lage A, Pitt B, on behalf of the FIGARO-DKD Investigators. Finerenone Reduces Risk of Incident Heart Failure in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Analyses From the FIGARO-DKD Trial. Circulation 2022; 145: 437–447. [CrossRef]

- Navaneethan SD, Bansal N, Cavanaugh KL, Chang A, Crowley S, Delgado C, Estrella MM, Ghossein C, Ikizler TA, Koncicki H, St. Peter W, Tuttle KR, William J. KDOQI US Commentary on the KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2025; 85: 135–176. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Wang T, Song J. A review regarding the article ‘Electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated Steatotic liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis.’ Curr Probl Cardiol 2024; 49: 102626. [CrossRef]

- Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Castro Narro GE, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW-S, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol 2023; 79: 1542–1556. [CrossRef]

- Cho SW. Selective Agonists of Thyroid Hormone Receptor Beta: Promising Tools for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Endocrinol Metab 2024; 39: 285–287. [CrossRef]

- Harrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, Schattenberg JM, Loomba R, Taub R, Labriola D, Moussa SE, Neff GW, Rinella ME, Anstee QM, Abdelmalek MF, Younossi Z, Baum SJ, Francque S, Charlton MR, Newsome PN, Lanthier N, Schiefke I, Mangia A, Pericàs JM, Patil R, Sanyal AJ, Noureddin M, Bansal MB, Alkhouri N, Castera L, Rudraraju M, Ratziu V. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2024; 390: 497–509. [CrossRef]

- Harrison SA, Bashir MR, Guy CD, Zhou R, Moylan CA, Frias JP, Alkhouri N, Bansal MB, Baum S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Taub R, Moussa SE. Resmetirom (MGL-3196) for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. The Lancet 2019; 394: 2012–2024. [CrossRef]

- Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Taub RA, Barbone JM, Harrison SA. Hepatic Fat Reduction Due to Resmetirom in Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Is Associated With Improvement of Quality of Life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 20: 1354-1361.e7. [CrossRef]

- Karim G, Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai Israel, New York, NY, USA, Bansal MB, Division of Liver Diseases, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA. Resmetirom: An Orally Administered, Small-molecule, Liver-directed, β-selective THR Agonist for the Treatment of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Eur Endocrinol 2023; 19: 60. [CrossRef]

- A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Study of ISIS 304801 Administered Subcutaneously to Patients with Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (FCS). 2022. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02211209.

- Marino L, Kim A, Ni B, Celi FS. Thyroid hormone action and liver disease, a complex interplay. Hepatology 2025; 81: 651–669. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Soffer G, Ginsberg HN, Berglund L, Duell PB, Heffron SP, Kamstrup PR, Lloyd-Jones DM, Marcovina SM, Yeang C, Koschinsky ML, on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Lipoprotein(a): A Genetically Determined, Causal, and Prevalent Risk Factor for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2022; 42. [CrossRef]

- Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated Lipoprotein(a) Levels, LPA Risk Genotypes, and Increased Risk of Heart Failure in the General Population. JACC Heart Fail 2016; 4: 78–87. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Liu J, Shen J, Chen Y, He L, Li M, Xie X. Association of lipoprotein (a) and 1 year prognosis in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail 2022; 9: 2399–2406. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Baars DP, Aggarwal K, Desai R, Singh D, Pinto-Sietsma S-J. Association between lipoprotein (a) and risk of heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies. Curr Probl Cardiol 2024; 49: 102439. [CrossRef]

- Steffen BT, Duprez D, Bertoni AG, Guan W, Tsai MY. Lp(a) [Lipoprotein(a)]-Related Risk of Heart Failure Is Evident in Whites but Not in Other Racial/Ethnic Groups: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2018; 38: 2498–2504. [CrossRef]

- Wu B, Zhang Z, Long J, Zhao H, Zeng F. Association between lipoprotein (a) and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction development. J Clin Lab Anal 2022; 36: e24083. [CrossRef]

- Khera AV, Everett BM, Caulfield MP, Hantash FM, Wohlgemuth J, Ridker PM, Mora S. Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations, Rosuvastatin Therapy, and Residual Vascular Risk: An Analysis From the JUPITER Trial (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin). Circulation 2014; 129: 635–642. [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas S, Viney NJ, Hughes SG, Singleton W, Graham MJ, Baker BF, Burkey JL, Yang Q, Marcovina SM, Geary RS, Crooke RM, Witztum JL. Antisense therapy targeting apolipoprotein(a): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 study. The Lancet 2015; 386: 1472–1483. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi A, Karimian A, Shokri K, Mohammadi A, Hazhir-Karzar N, Bahar R, Radfar A, Pakyari M, Tehrani B. RNA Therapies in Cardio-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome: Advancing Disease Management. J Cardiovasc Transl Res (e-pub ahead of print 13 March 2025; [CrossRef]

- Witztum JL, Gaudet D, Freedman SD, Alexander VJ, Digenio A, Williams KR, Yang Q, Hughes SG, Geary RS, Arca M, Stroes ESG, Bergeron J, Soran H, Civeira F, Hemphill L, Tsimikas S, Blom DJ, O’Dea L, Bruckert E. Volanesorsen and Triglyceride Levels in Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 531–542. [CrossRef]

- Stitziel NO. Reducing the Risk of Pancreatitis by Inhibiting APOC3. N Engl J Med 2025; 392: 197–199. [CrossRef]

- Raal FJ, Kallend D, Ray KK, Turner T, Koenig W, Wright RS, Wijngaard PLJ, Curcio D, Jaros MJ, Leiter LA, Kastelein JJP. Inclisiran for the Treatment of Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1520–1530. [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue ML, Rosenson RS, López JAG, Lepor NE, Baum SJ, Stout E, Gaudet D, Knusel B, Kuder JF, Murphy SA, Wang H, Wu Y, Shah T, Wang J, Wilmanski T, Sohn W, Kassahun H, Sabatine MS. The Off-Treatment Effects of Olpasiran on Lipoprotein(a) Lowering. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024; 84: 790–797. [CrossRef]

- Ridker PM, Devalaraja M, Baeres FMM, Engelmann MDM, Hovingh GK, Ivkovic M, Lo L, Kling D, Pergola P, Raj D, Libby P, Davidson M. IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. The Lancet 2021; 397: 2060–2069. [CrossRef]

- Chang B, Laffin LJ, Sarraju A, Nissen SE. Obicetrapib—the Rebirth of CETP Inhibitors? Curr Atheroscler Rep 2024; 26: 603–608. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls SJ, Ditmarsch M, Kastelein JJ, Rigby SP, Kling D, Curcio DL, Alp NJ, Davidson MH. Lipid lowering effects of the CETP inhibitor obicetrapib in combination with high-intensity statins: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med 2022; 28: 1672–1678. [CrossRef]

- Zhu H, Qiao S, Zhao D, Wang K, Wang B, Niu Y, Shang S, Dong Z, Zhang W, Zheng Y, Chen X. Machine learning model for cardiovascular disease prediction in patients with chronic kidney disease. Front Endocrinol 2024; 15: 1390729. [CrossRef]

- Ndumele CE, Rangaswami J, Chow SL, Neeland IJ, Tuttle KR, Khan SS, Coresh J, Mathew RO, Baker-Smith CM, Carnethon MR, Despres J-P, Ho JE, Joseph JJ, Kernan WN, Khera A, Kosiborod MN, Lekavich CL, Lewis EF, Lo KB, Ozkan B, Palaniappan LP, Patel SS, Pencina MJ, Powell-Wiley TM, Sperling LS, Virani SS, Wright JT, Rajgopal Singh R, Elkind MSV, on behalf of the American Heart Association. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023; 148: 1606–1635. [CrossRef]

- Loftus TJ, Shickel B, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Ren Y, Glicksberg BS, Cao J, Singh K, Chan L, Nadkarni GN, Bihorac A. Artificial intelligence-enabled decision support in nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022; 18: 452–465. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Liu Z, Liu C, Sun H, Li X, Yang Y. Integrating Artificial Intelligence in the Diagnosis and Management of Metabolic Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2025; 41: e70039. [CrossRef]

- Muse ED, Topol EJ. Transforming the cardiometabolic disease landscape: Multimodal AI-powered approaches in prevention and management. Cell Metab 2024; 36: 670–683. [CrossRef]

- Vrbaški D, Vrbaški M, Kupusinac A, Ivanović D, Stokić E, Ivetić D, Doroslovački K. Methods for algorithmic diagnosis of metabolic syndrome. Artif Intell Med 2019; 101: 101708. [CrossRef]