Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Approach

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Step I: Quantum-Chemical Calculations of the Gas-Phase Enthalpies of Formation

3.2. Step II: Evaluation of the Thermodynamic Functions of Vaporisation

3.2.1. Absolute Vapor Pressures and Vaporisation Enthalpies

3.2.2. Validation of Vaporisation Enthalpies by Structure-Property Correlations

3.2.3. Validation of Vaporisation Enthalpies Using Correlation with the Kovats Indices Jx

3.2.4. Standard Molar Vaporisation Entropies

3.3. Step III: Thermodynamic Analysis of the LOHC Systems Based on Aromatic Ethers

3.3.1. Reaction Enthalpies, Entropies and Gibbs Energies of the LOHC Hydrogenation

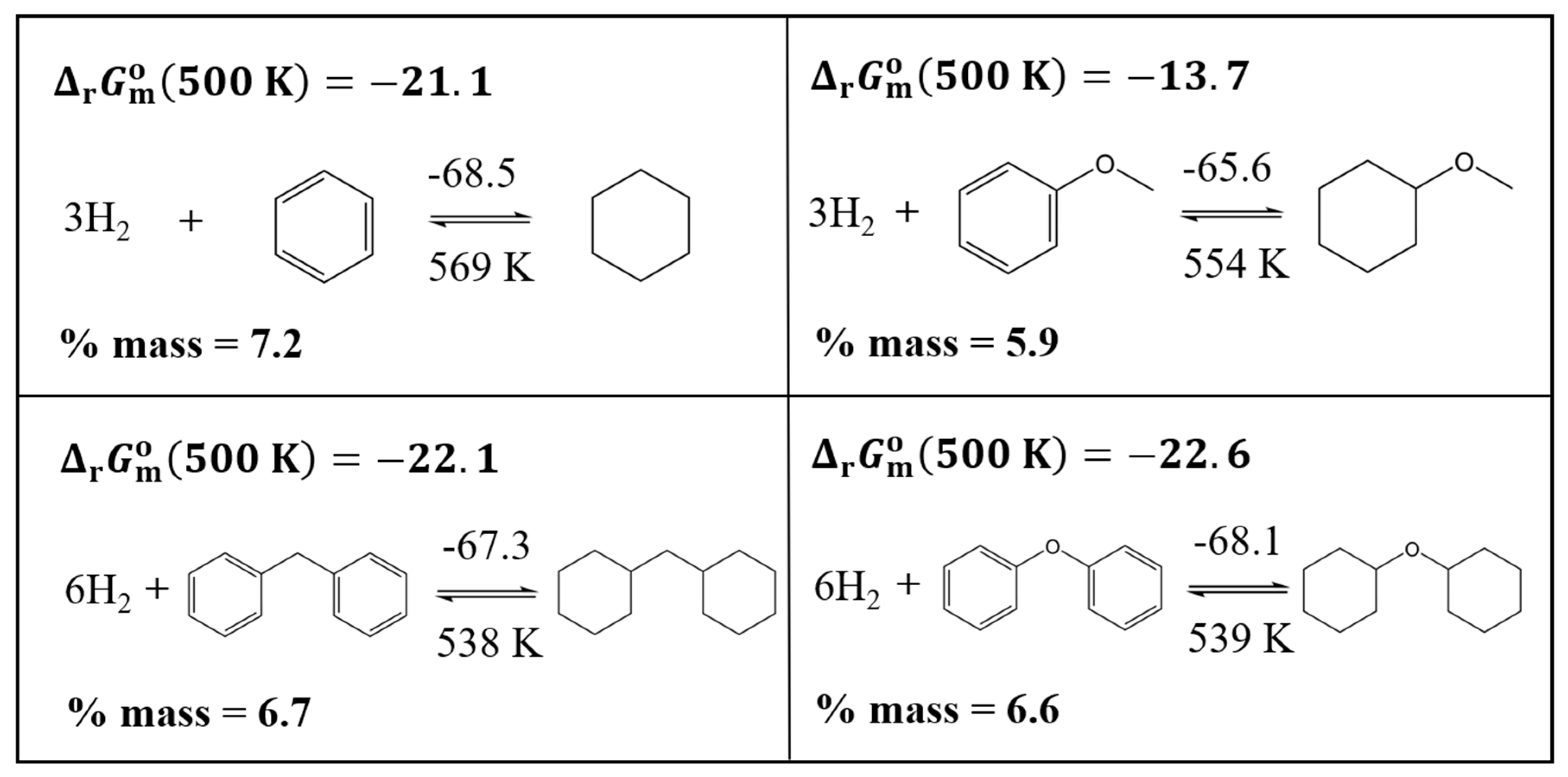

3.3.2. Comparison of the Thermodynamics of Hydrogenation Reactions with and Without Oxygen Functionality

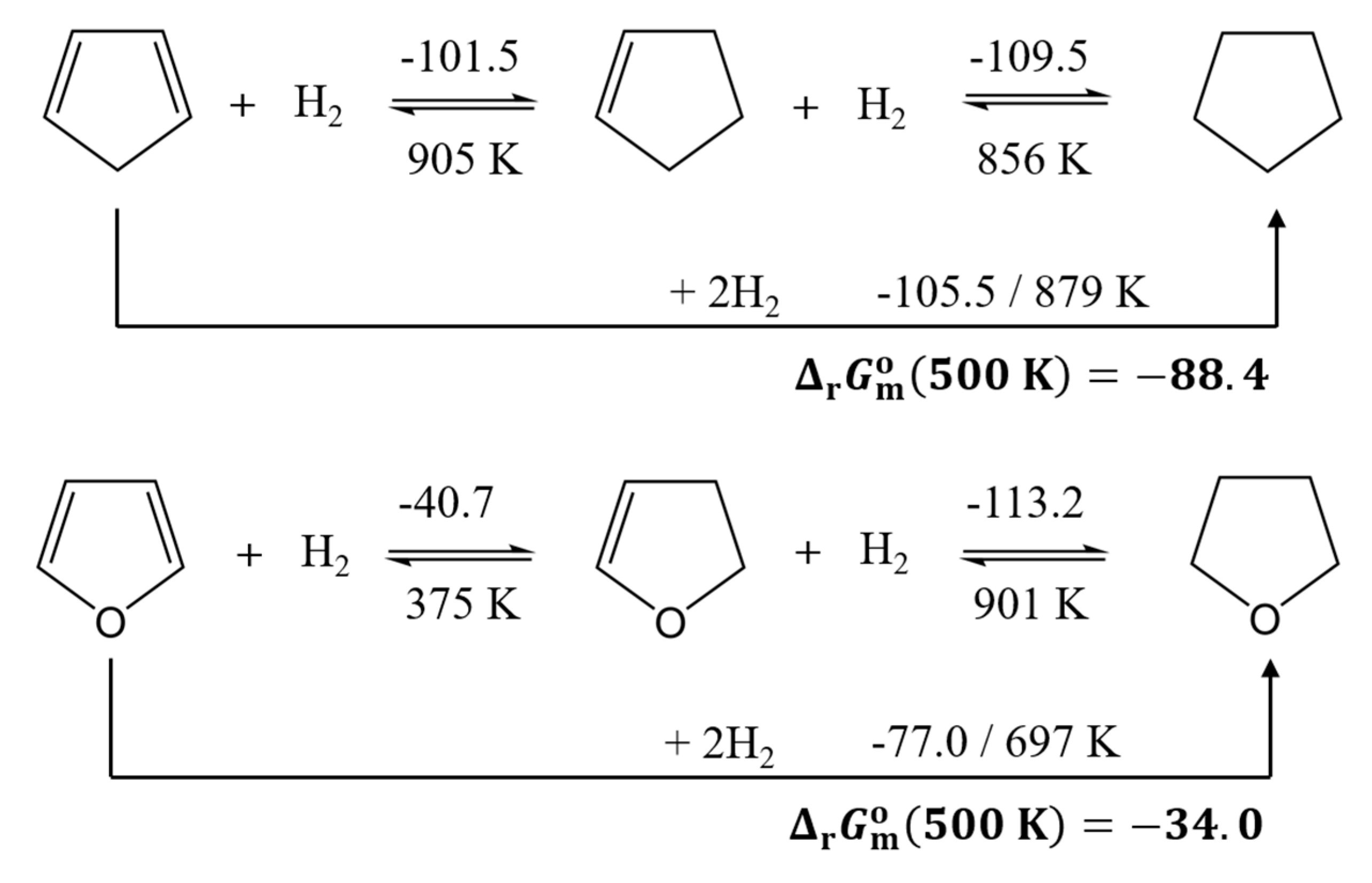

3.3.3. Comparison of Reactions Involving Five-Membered Aliphatic Rings

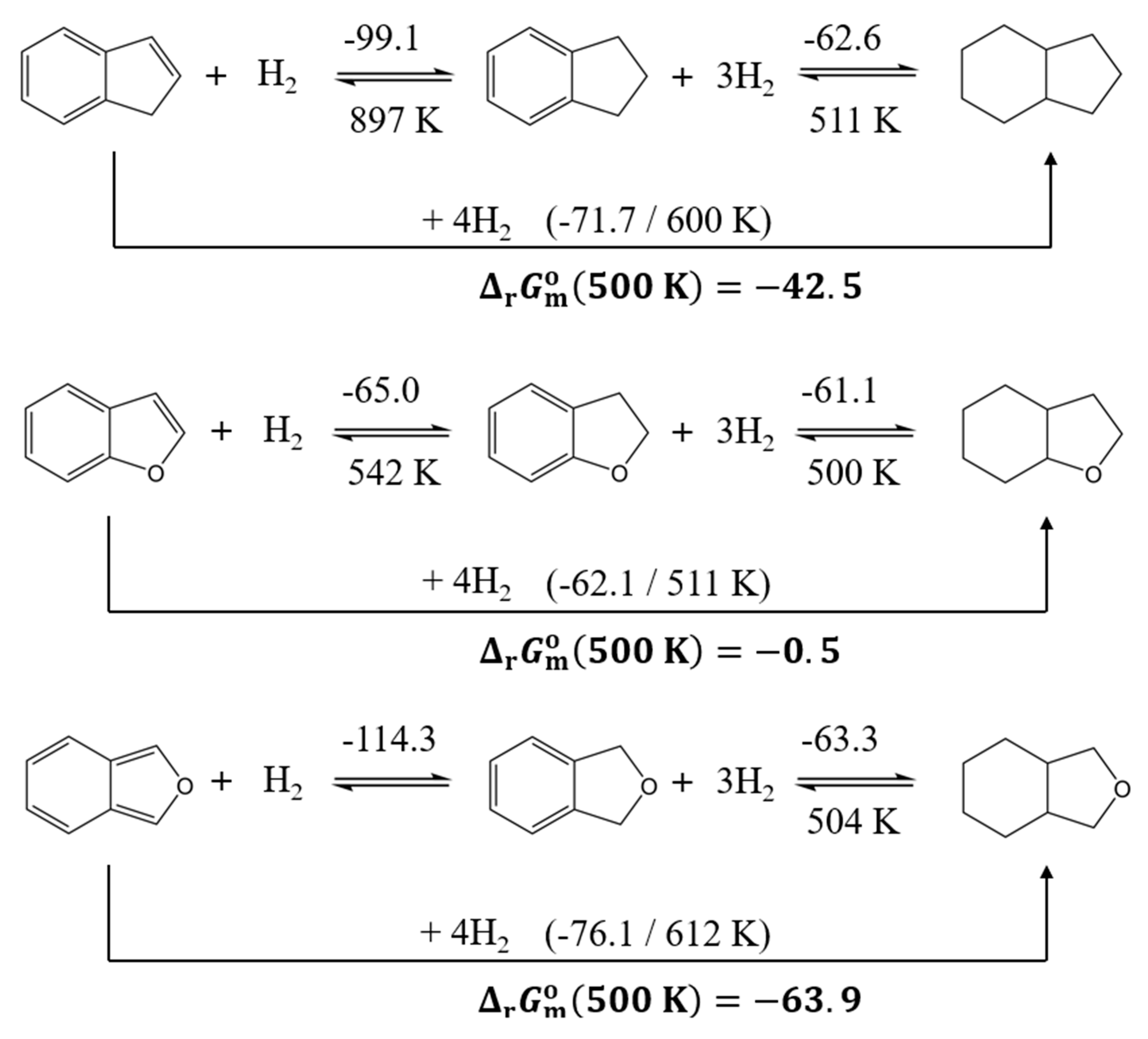

3.3.4. Comparison of Reactions Involving Aromatic Ethers with Attached Five-Membered Aliphatic Ring

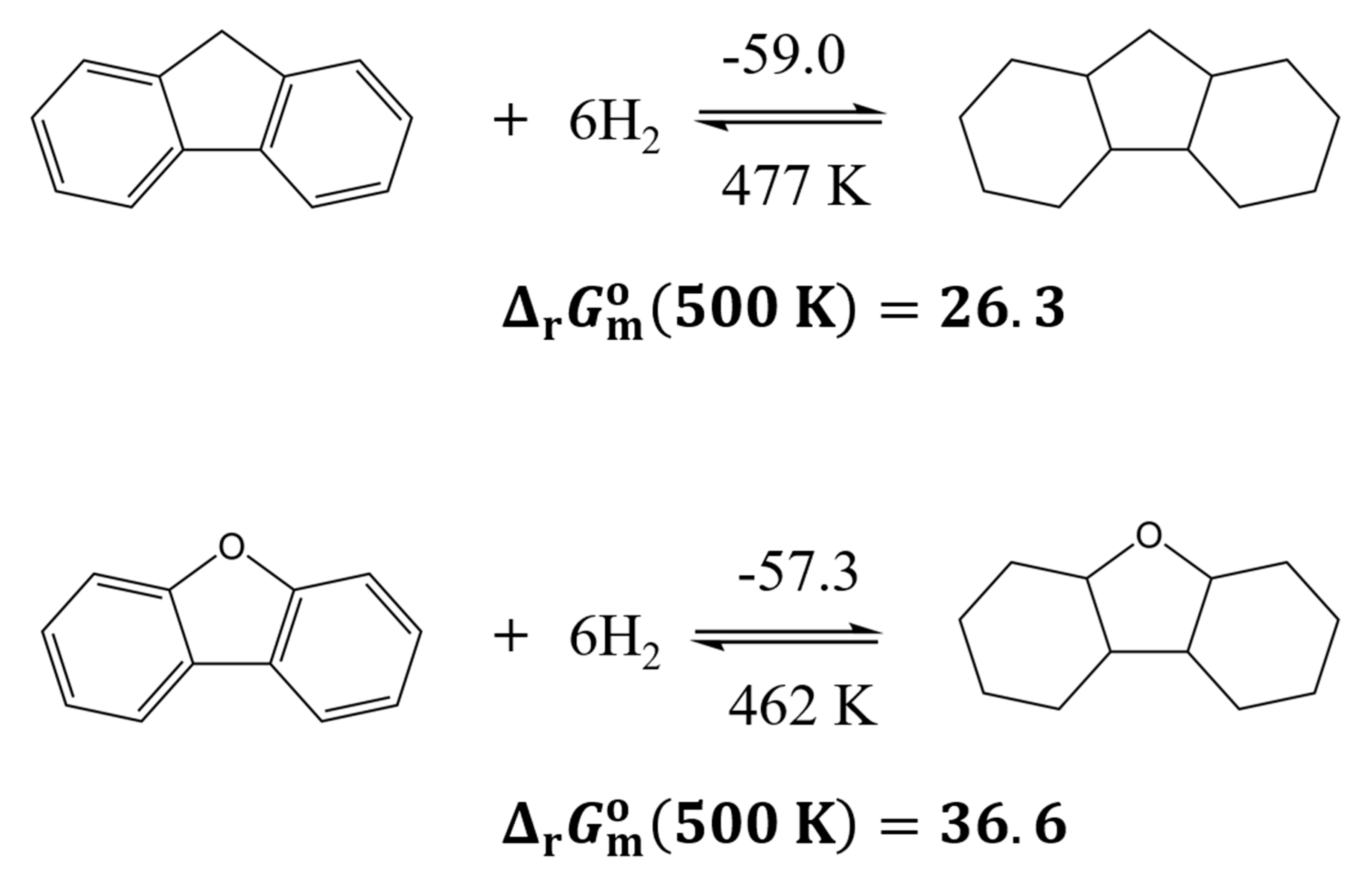

3.3.5. Comparison of Reactions Involving a Five-Membered Aliphatic Ring Fused to Two Benzene Rings

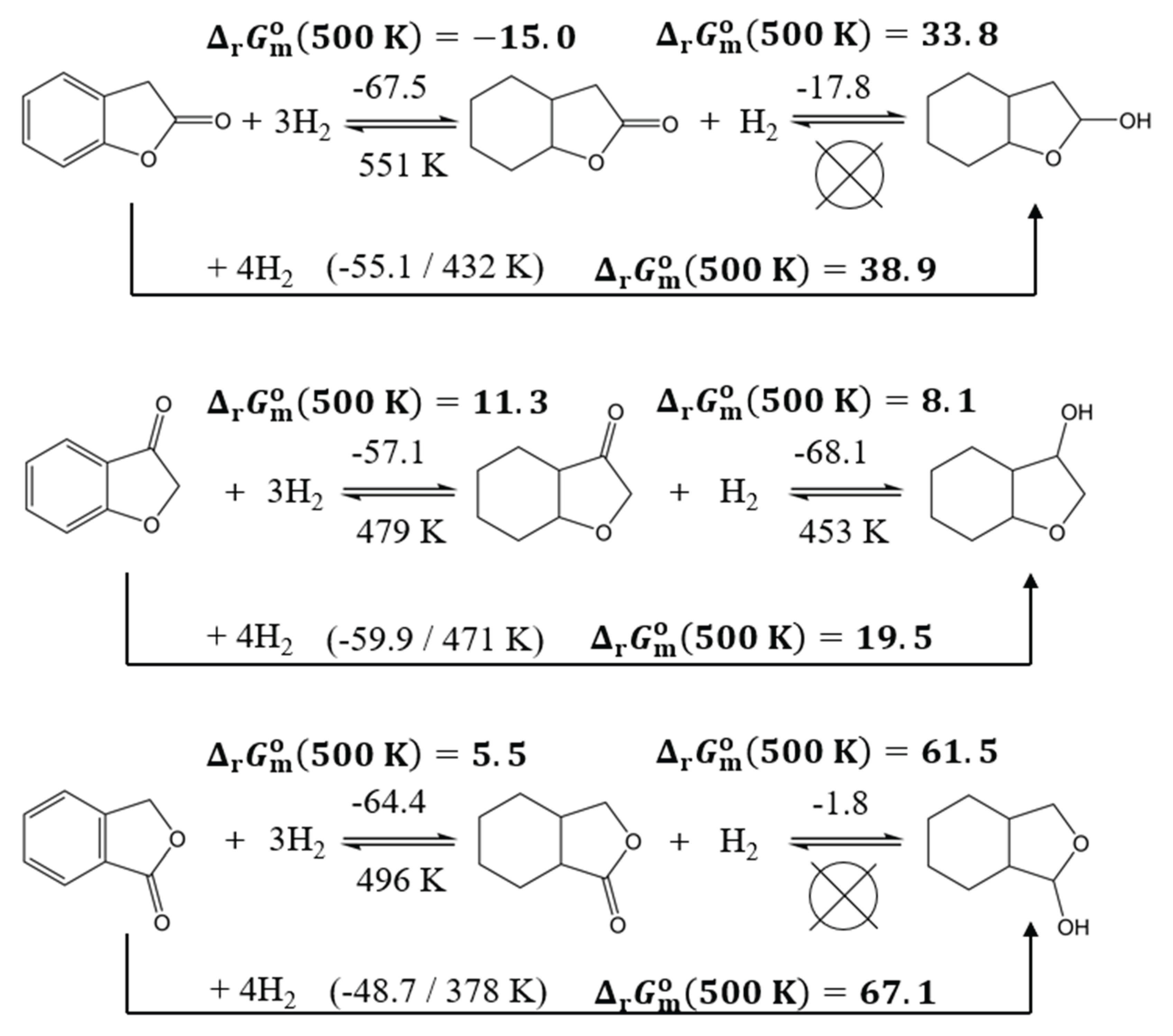

3.3.6. Could the Lactone Ring Improve Hydrogen Storage Thermodynamics?

3.3.7. Thermodynamic Analysis of the Reversible Hydrogenation/Dehydrogenation Process

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Teichmann, D.; Arlt, W.; Wasserscheid, P.; Freymann, R. A Future Energy Supply Based on Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHC). Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2767. [CrossRef]

- Zakgeym, D.; Hofmann, J.D.; Maurer, L.A.; Auer, F.; Müller, K.; Wolf, M.; Wasserscheid, P. Better through Oxygen Functionality? The Benzophenone/Dicyclohexylmethanol LOHC-System. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 1213–1222. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P.; Samarov, A.A.; Vostrikov, S. V. Does the Oxygen Functionality Really Improve the Thermodynamics of Reversible Hydrogen Storage with Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers? Oxygen 2024, 4, 266–284. [CrossRef]

- Ghahremanpour, M.M.; van Maaren, P.J.; Ditz, J.C.; Lindh, R.; van der Spoel, D. Large-Scale Calculations of Gas Phase Thermochemistry: Enthalpy of Formation, Standard Entropy, and Heat Capacity. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 114305. [CrossRef]

- Pracht, P.; Bohle, F.; Grimme, S. Automated Exploration of the Low-Energy Chemical Space with Fast Quantum Chemical Methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 7169–7192. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01 Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT. 2016.

- Wheeler, S.E.; Houk, K.N.; Schleyer, P. v. R.; Allen, W.D. A Hierarchy of Homodesmotic Reactions for Thermochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2547–2560. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P.; Emel’yanenko, V.N.; Notario, R.; Roux, M.V.; Chickos, J.S.; Liebman, J.F. Rediscovering the Wheel. Thermochemical Analysis of Energetics of the Aromatic Diazines. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 3454–3459. [CrossRef]

- Notario, R.; Victoria Roux, M.; Castaño, O. The Enthalpy of Formation of Dibenzofuran and Some Related Oxygen-Containing Heterocycles in the Gas Phase. A GAUSSIAN-3 Theoretical Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001, 3, 3717–3721. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.C.S.; Matos, M.A.R.; Santos, L.M.N.B.F.; Morais, V.M.F. Reprint of: Energetics of 2- and 3-Coumaranone Isomers: A Combined Calorimetric and Computational Study. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2014, 73, 283–289. [CrossRef]

- Steele, W.V.; Chirico, R.D. Thermodynamics and the Hydrodeoxygenation of 2,3-Benzofuran; 1990;

- Verevkin, S.P.; Emel’yanenko, V.N.; Pimerzin, A.A.; Vishnevskaya, E.E. Thermodynamic Analysis of Strain in Heteroatom Derivatives of Indene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 12271–12279. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P.; Emel’yanenko, V.N.; Pimerzin, A.A.; Vishnevskaya, E.E. Thermodynamic Analysis of Strain in the Five-Membered Oxygen and Nitrogen Heterocyclic Compounds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 1992–2004. [CrossRef]

- Steele, W. V.; Chirico, R.D.; Knipmeyer, S.E.; Nguyen, A.; Smith, N.K.; Tasker, I.R. Thermodynamic Properties and Ideal-Gas Enthalpies of Formation for Cyclohexene, Phthalan (2,5-Dihydrobenzo-3,4-Furan), Isoxazole, Octylamine, Dioctylamine, Trioctylamine, Phenyl Isocyanate, and 1,4,5,6-Tetrahydropyrimidine. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1996, 41, 1269–1284. [CrossRef]

- Chirico, R..; Gammon, B..; Knipmeyer, S..; Nguyen, A.; Strube, M..; Tsonopoulos, C.; Steele, W.. The Thermodynamic Properties of Dibenzofuran. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 1990, 22, 1075–1096. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P. Enthalpy of Sublimation of Dibenzofuran: A Redetermination. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 710–712. [CrossRef]

- Rakus, K.; Verevkin, S.P.; Schätzer, J.; Beckhaus, H.; Rüchardt, C. Thermolabile Hydrocarbons, 33. Thermochemistry and Thermal Decomposition of 9,9′-Bifluorenyl and 9,9′-Dimethyl-9,9′-bifluorenyl – The Stabilization Energy of 9-Fluorenyl Radicals. Chem. Ber. 1994, 127, 1095–1103. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P. Vapor Pressure Measurements on Fluorene and Methyl-Fluorenes. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2004, 225, 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Tavernier, P. Donnees Thermochimiques Relatives Aux Constituants Des Poudres. Mem. Poudres 1956, 301–327.

- Freitas, V.L.S.; Santos, C.P.F.; Ribeiro da Silva, M.D.M.C.; Ribeiro da Silva, M.A.V. The Effect of Ketone Groups on the Energetic Properties of Phthalan Derivatives. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2016, 96, 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.M.; Malanowski, S. Handbook of the Thermodynamics of Organic Compounds; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1987; ISBN 978-94-010-7923-5.

- Gobble, C.; Chickos, J.S. The Vapor Pressure and Vaporization Enthalpy of R-(+)-Menthofuran, a Hepatotoxin Metabolically Derived from the Abortifacient Terpene, (R)-(+)-Pulegone by Correlation Gas Chromatography. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2016, 98, 135–139. [CrossRef]

- Stull, D.R. Vapor Pressure of Pure Substances. Organic and Inorganic Compounds. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1947, 39, 517–540. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P. Weaving a Web of Reliable Thermochemistry around Lignin Building Blocks: Phenol, Benzaldehyde, and Anisole. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 6073–6085. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P.; Samarov, A.A.; Vostrikov, S. V. Thermodynamics of Reversible Hydrogen Storage: Are Methoxy-Substituted Biphenyls Better through Oxygen Functionality? Hydrogen 2023, 4, 862–880. [CrossRef]

- Samarov, A.A.; Verevkin, S.P. Hydrogen Storage Technologies: Methyl-Substituted Biphenyls as an Auspicious Alternative to Conventional Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHC). J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2022, 165, 106648. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P.; Andreeva, I. V.; Zherikova, K. V.; Pimerzin, A.A. Prediction of Thermodynamic Properties: Centerpiece Approach—How Do We Avoid Confusion and Get Reliable Results? J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 8525–8534. [CrossRef]

- Benson, S.W. Thermochemical Kinetics, 2nd Ed. John Wiley & Sons, New York-London-Sydney-Toronto. 1976, 1–320.

- Verevkin, S.P.; Emel’yanenko, V.N.; Diky, V.; Muzny, C.D.; Chirico, R.D.; Frenkel, M. New Group-Contribution Approach to Thermochemical Properties of Organic Compounds: Hydrocarbons and Oxygen-Containing Compounds. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2013, 42, 033102. [CrossRef]

- Kováts, E. Gas-chromatographische Charakterisierung Organischer Verbindungen. Teil 1: Retentionsindices Aliphatischer Halogenide, Alkohole, Aldehyde Und Ketone. Helv. Chim. Acta 1958, 41, 1915–1932. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P. Vapour Pressures and Enthalpies of Vaporization of a Series of the Linear N-Alkyl-Benzenes. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2006, 38, 1111–1123. [CrossRef]

- NIST Chemistry WebBook. Available Online: Https://Webbook.Nist.Gov/Chemistry/ (Accessed on 15.06.2025).

- Majer, V.; Svoboda, V. Enthalpies of Vaporization of Organic Compounds: A Critical Review and Data Compilation, Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford; 1985;

- Steele, W. V.; Chirico, R.D.; Knipmeyer, S.E.; Nguyen, A. Measurements of Vapor Pressure, Heat Capacity, and Density along the Saturation Line for Cyclopropane Carboxylic Acid, N , N -Diethylethanolamine, 2,3-Dihydrofuran, 5-Hexen-2-One, Perfluorobutanoic Acid, and 2-Phenylpropionaldehyde. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2002, 47, 715–724. [CrossRef]

- Steele, W. V.; Chirico, R.D. Thermodynamics and the Hydrodeoxygenation of 2,3-Benzofuran NIPER-457. Publ. by DOE Foss. Energy, Bartlesv. Proj. Off. Available from NTIS, Rep. No. DE-90000218 1990.

- Chirico, R.D.; Nguyen, A.; Steele, W.V.; Strube, M.M.; Hossenlopp, I.A.; Gammon, B.E. Thermochemical and Thermophysical Properties of Organic Compounds Derived from Fossil Substances. Chemical Thermodynamic Properties of Organic Oxygen Compounds Found in Fossil Materials. NIPER Rep. 1986, 135, 42.

- Sasse, K.; Jose, J.; Merlin, J.-C. A Static Apparatus for Measurement of Low Vapor Pressures. Experimental Results on High Molecular-Weight Hydrocarbons. Fluid Phase Equilib. 1988, 42, 287–304. [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, G.B.; Scott, D.W.; Hubbard, W.N.; Katz, C.; McCullough, J.P.; Gross, M.E.; Williamson, K.D.; Waddington, G. Thermodynamic Properties of Furan. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 4662–4669. [CrossRef]

- Parsana, V.M.; Parikh, S.; Ziniya, K.; Dave, H.; Gadhiya, P.; Joshi, K.; Gandhi, D.; Vlugt, T.J.H.; Ramdin, M. Isobaric Vapor–Liquid Equilibrium Data for Tetrahydrofuran + Acetic Acid and Tetrahydrofuran + Trichloroethylene Mixtures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2023, 68, 349–357. [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, B.V.; Lityagov, V.Y. Calorimetric Study of Tetrahydrofuran and Its Polymerization in the Temperature Range 0–400°K. Vysok. Soedin. 1977, A19, 2283–2290.

- Furuyama, S.; Golden, D.M.; Benson, S.W. Thermochemistry of Cyclopentene and Cyclopentadiene from Studies of Gas-Phase Equilibria. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 1970, 2, 161–169. [CrossRef]

- Beckett, C.W.; Freeman, N.K.; Pitzer, K.S. The Thermodynamic Properties and Molecular Structure of Cyclopentene and Cyclohexene 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 4227–4230. [CrossRef]

- Huffman, H.M.; Eaton, M.; Oliver, G.D. The Heat Capacities, Heats of Transition, Heats of Fusion and Entropies of Cyclopentene and Cyclohexene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 2911–2914. [CrossRef]

- Douslin, D.R.; Huffman, H.M. The Heat Capacities, Heats of Transition, Heats of Fusion and Entropies of Cyclopentane, Methylcyclopentane and Methylcyclohexane 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1946, 68, 173–176. [CrossRef]

- Stull, D.R.; Sinke, G.C.; McDonald, R.A.; Hatton, W.E.; Hildebrand, D.L. Thermodynamic Properties of Indane and Indene. Pure Appl. Chem. 1961, 2, 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Finke, H..; McCullough, J..; Messerly, J..; Osborn, A.; Douslin, D.. Cis- and Trans-Hexahydroindan. Chemical Thermodynamic Properties and Isomerization Equilibrium. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 1972, 4, 477–494. [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, S.P.; Samarov, A.A.; Vostrikov, S. V.; Wasserscheid, P.; Müller, K. Comprehensive Thermodynamic Study of Alkyl-Cyclohexanes as Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers Motifs. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 42–59. [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Völkl, J.; Arlt, W. Thermodynamic Evaluation of Potential Organic Hydrogen Carriers. Energy Technol. 2013, 1, 20–24. [CrossRef]

| Compound |

(g) b G3MP2/AT |

(g) c G3MP2//B3LYP |

(g) d G3MP2 |

(g)QC e |

(g) f (exp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

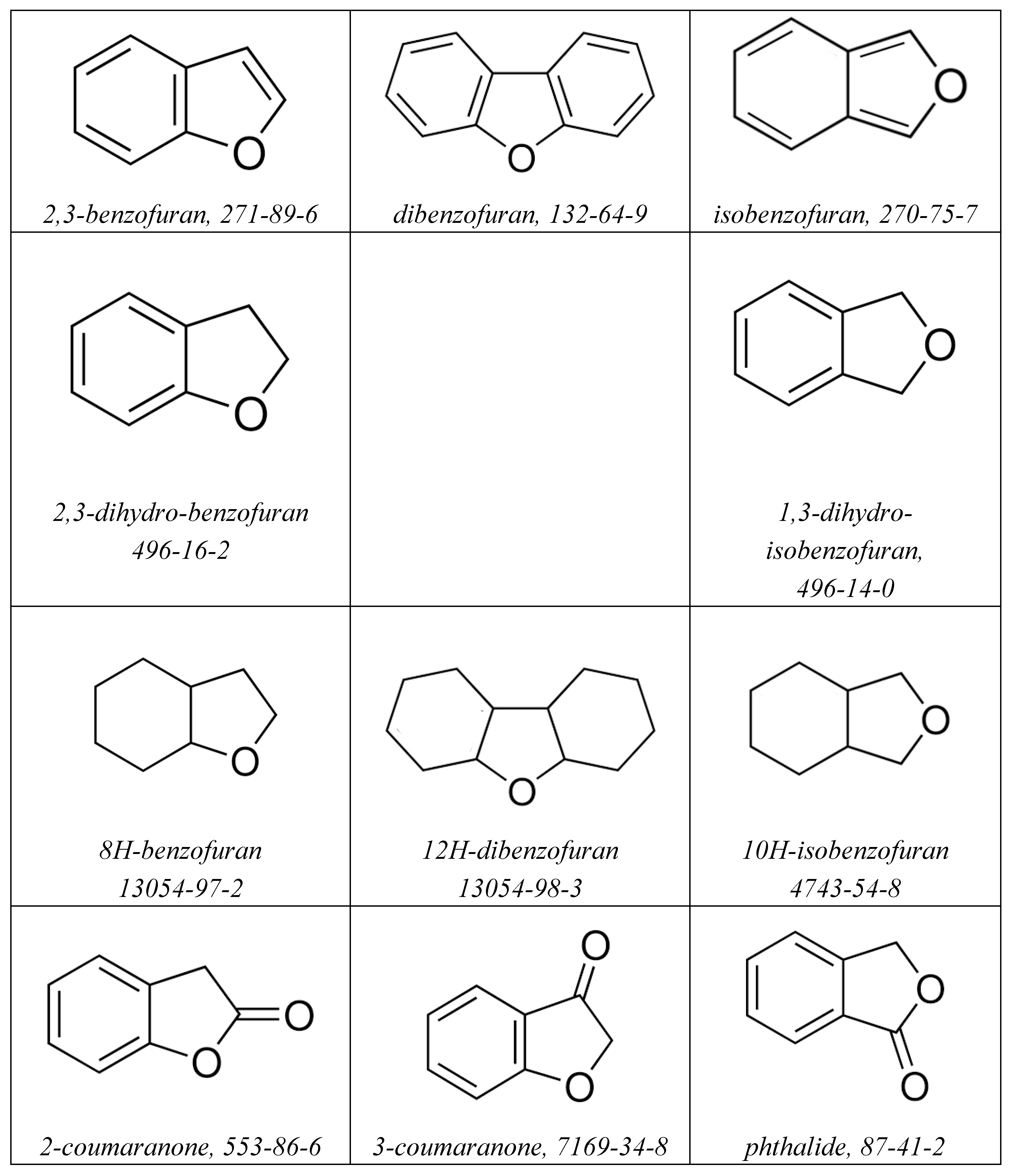

| 2,3-benzofuran | 17.2±4.1 | 16.6±4.0 | 16.9±2.9 | 13.9±0.7 | |

| 2,3-dihydrobenzofuran | -47.1±4.1 | -45.5±4.0 | -46.3±2.9 | -46.7±0.9 | |

| isobenzofuran | 79.3±4.1 | 79.3±4.1 | |||

| 1,3-dihydro-isobenzofuran | -26.3±4.1 | -26.0±4.0 | -26.1±2.9 | -30.6±1.2 | |

| dibenzofuran | 50.1±4.1 | 48.9±4.0 | 49.5±2.9 | 52.9±0.7 | |

| 2-coumaranone | -222.7±4.1 | -217.5±2.8 | -218.1±3.4 | -218.7±1.9 | (-210.8±4.0) |

| 3-coumaranone | -166.3±4.1 | -162.1±2.6 | -162.3±3.4 | -162.9±1.9 | -168.8±2.4 |

| phthalide | -224.1±4.1 | -220.4±3.4 | -220.7±4.4 | -221.4±2.3 | -220.6±2.8 |

| Compounds | (liq or cr) | b | (g)expc | (g)QCd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,3-benzofuran [271-89-6] (liq) | -34.8±0.7 [11] | |||

| -35.3±1.6 [12] | ||||

| -34.9±0.6 | 48.4±0.4 | 13.9±0.7 | 16.9±2.9 | |

| 2,3-dihydro-benzofuran [496-16-2] (liq) | -99.8±0.7 [11] | |||

| -100.6±1.9 [13] | ||||

| -99.9±0.8 | 53.2±0.3 | -46.7±0.9 | -46.3±2.9 | |

| 1,3-dihydro-isobenzofuran [496-14-0] (liq) | -83.8±0.9 [14] | 53.2±0.8 | -30.6±1.2 | -26.1±2.9 |

| dibenzofuran [132-64-9] (cr) | -29.1±0.6 [15] | 82.0±0.3 [16] | 52.9±0.7 | 49.5±2.9 |

| fluorene [86-73-7] (cr) | 89.9±1.4 [17] | 86.1±0.1 [18] | 176.0±1.4 | - |

| 2-coumaranone [553-86-6] (cr) | (-292.4±3.7) [10] | 81.6±1.4 f | (-210.8±4.0) | -218.7±1.9 |

| 3-coumaranone [7169-34-8] (cr) | -254.9±2.0 [10] | 86.1±1.4 g | -168.8±2.4 | -162.9±1.9 |

| phthalide [87-41-2] (cr) | (-366±10) [19] | |||

| -312.4±1.5 [20] | 92.0±2.2h | -220.6±2.8 | -221.4±2.3 |

| Compounds | Methoda |

T-range/ K |

Tav |

298.15 Kb |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,3-benzofuran [271-89-6] | n/a | 323-403 | 45.0±1.5 | 47.9±1.6 | [21] |

| E | 273.2-488.1 | 45.1±0.1 | 48.0±0.6 | [11] | |

| T | 278.7-313.4 | 49.0±0.4 | 48.8±0.6 | [12] | |

| 48.4±0.4c | average | ||||

| Jx | 49.4±1.0 | Table 4 | |||

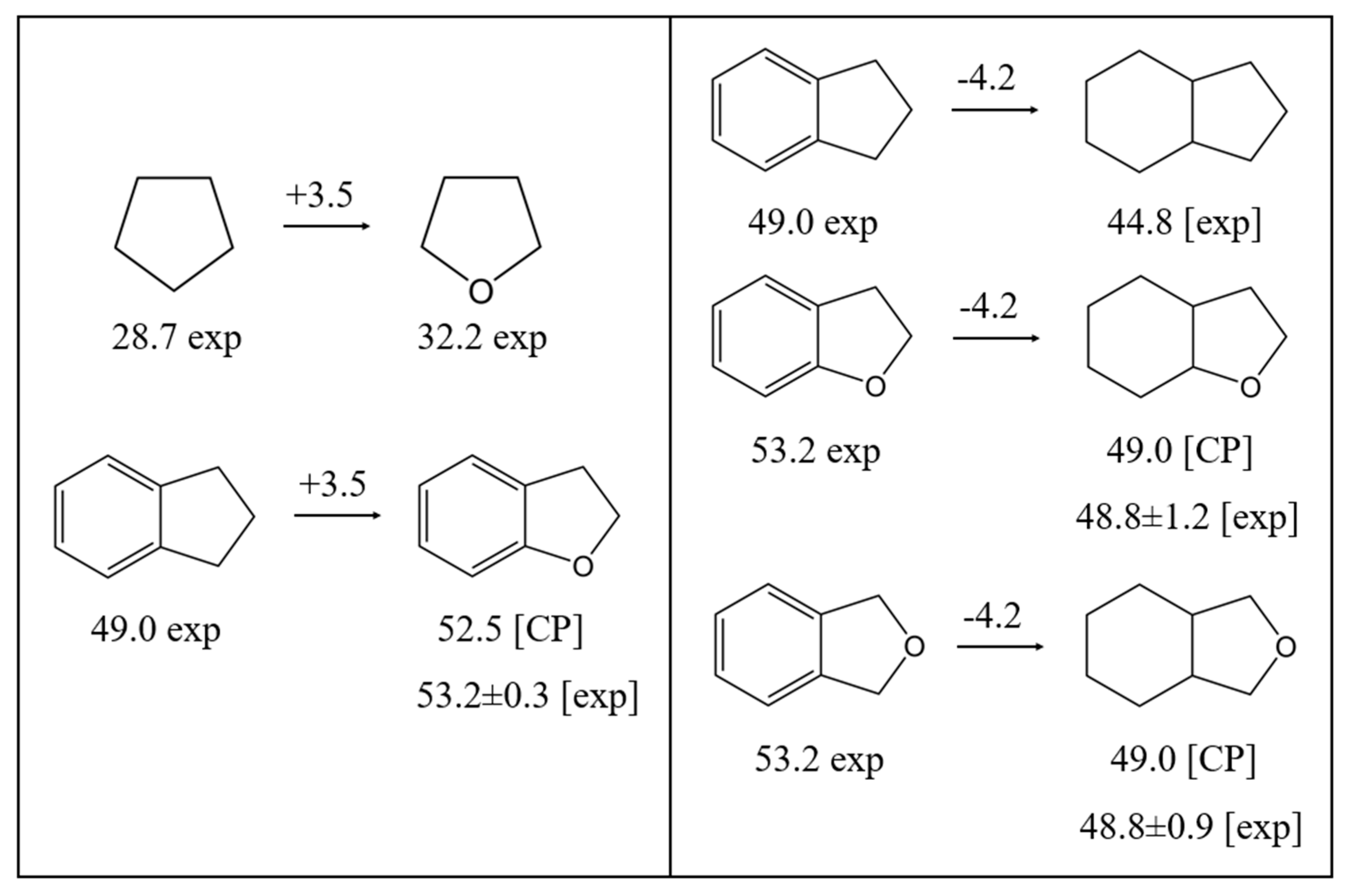

| 2,3-dihydro-benzofuran [496-16-2] | E | 285.0-503.2 | 48.7±0.1 | 53.0±0.9 | [11] |

| T | 278.7-333.0 | 52.7±0.2 | 53.2±0.4 | [13] | |

| BP | 341-465 | 47.8±0.8 | 53.2±1.3 | Table S4 | |

| 53.2±0.3c | |||||

| Jx | 52.7±1.0 | Table 4 | |||

| CP | 52.5±1.5 | Figure 3 | |||

| 1,3-dihydro-isobenzofuran [496-14-0] | E | 285.0-503.2 | 48.9±0.1 | 53.3±0.9 | [14] |

| phthalan | CGC | 298 | 52.7±2.9 | [22] | |

| BP | 318-465 | 48.0±1.1 | 53.1±1.5 | Table S4 | |

| 53.2±0.8c | average | ||||

| Jx | 52.6±1.0 | Table 4 | |||

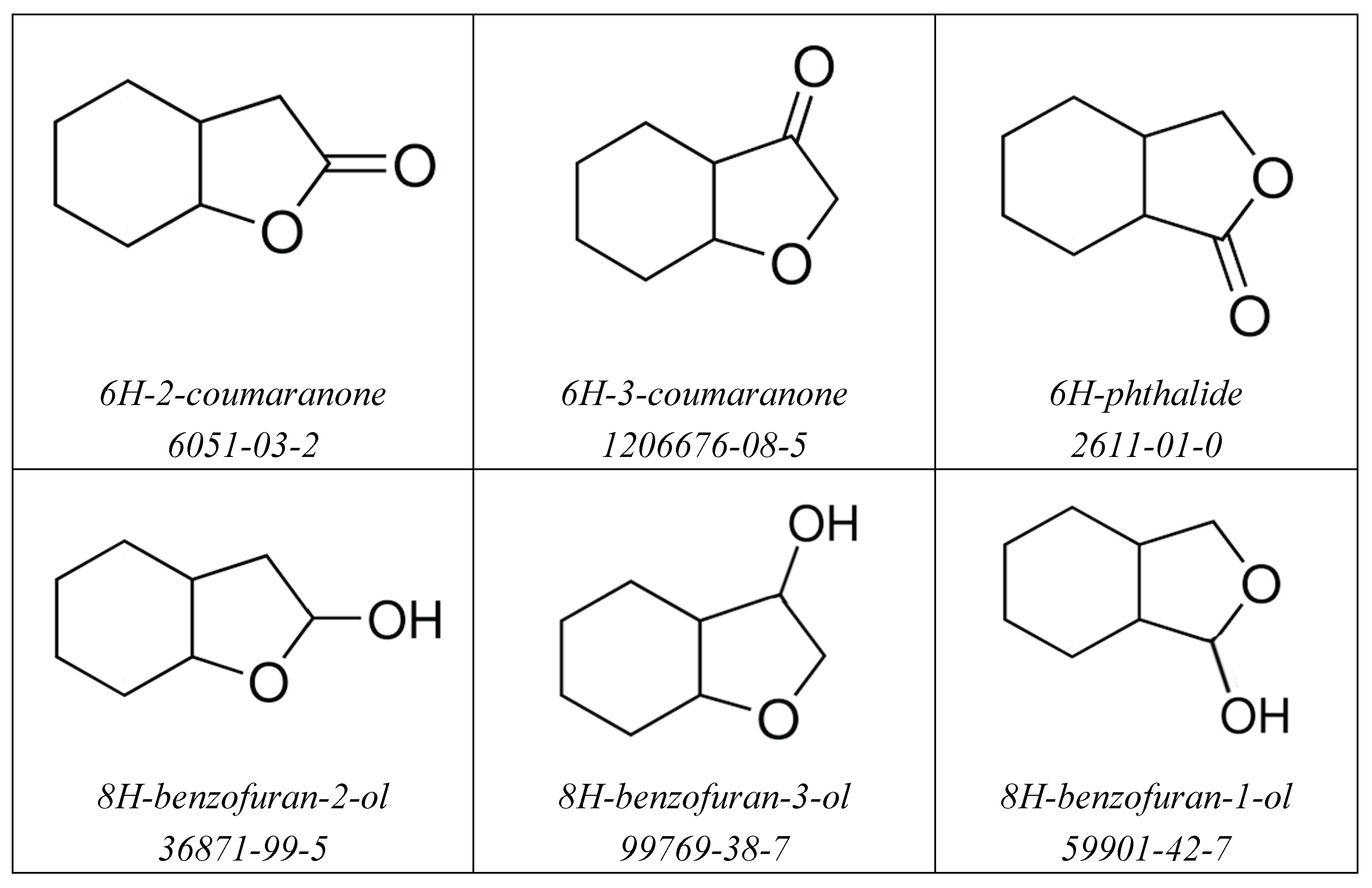

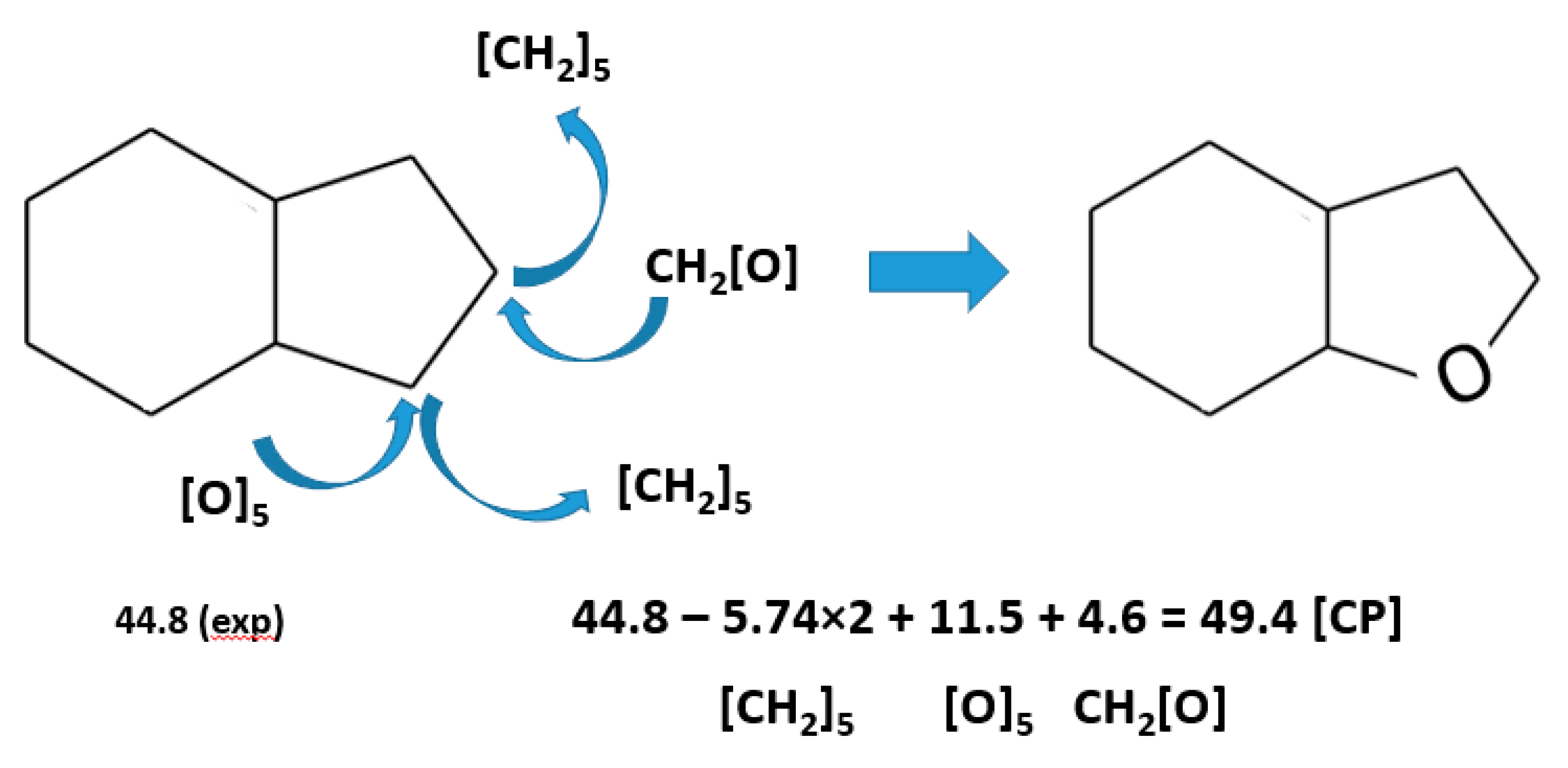

| 8H-octahydro-benzofuran | BP | 337-446 | 44.5±0.8 | 48.8±1.9 | Table S4 |

| [13054-97-2] | Tb | 48.8±1.5 | Eq. 7 | ||

| 48.8±1.2c | average | ||||

| CP | 49.0±1.5 | Figure 3 | |||

| CP | 48.3±1.5 | Figure S3 | |||

| CP | 48.4±1.5 | Figure 3 | |||

| GA | 48.9±1.5 | Figure S3 | |||

| 8H-octahydro-isobenzofuran | BP | 324-453 | 43.8±0.8 | 48.1±1.2 | Table S4 |

| [4743-54-8] | Tb | 49.9±1.5 | Eq. 7 | ||

| 48.8±0.9c | average | ||||

| CP | 48.8±1.5 | Figure 3 | |||

| CP | 48.3±1.5 | Figure 3 | |||

| CP | 48.3±1.5 | Figure S4 | |||

| GA | 48.8±1.5 | Figure S4 | |||

| 12H-dodecahydro-dibenzofuran | BP | 381-532 | 52.2±1.4 | 63.8±2.7 | Table S4 |

| [13054-98-3] | |||||

| 2(3H)-benzofuranone [553-86-6] | PhT | 298 | 61.9±2.0 | Table S3 | |

| 2-coumaranone | BP | 384-521 | 57.0±1.8 | 65.3±2.4 | Table S4 |

| Jx | 65.7±1.5 | Table 6-2 | |||

| Jx | 65.7±2.0 | Table 6-2 | |||

| CP | 67.3±1.5 | Figure S5 | |||

| CP | 66.2±1.5 | Figure S5 | |||

| 65.7±0.7 | average | ||||

| benzofuran-3(2H)-one [7169-34-8] | PhT | 298 | 67.8±2.3 | Table S3 | |

| 3-coumaranone | BP | 425-551 | 60.3±1.5 | 68.8±2.3 | Table S4 |

| CP | 66.7±1.5 | Figure S6 | |||

| CP | 67.3±1.5 | Figure S6 | |||

| CP | 65.5±1.5 | Figure S6 | |||

| 66.9±0.8c | average | ||||

| 2-benzofuran-1(3H)-one [87-41-2] | n/a | 368.7-563.0 | 58.7±1.5 | (66.9±2.2) | [23] |

| phthalide | PhT | 298 | 71.5±4.6 | Table S3 | |

| BP | 346-563 | 69.0±2.0 | 76.3±2.5 | Table S4 | |

| CP | 74.7±1.5 | Figure S7 | |||

| CP | 75.4±1.5 | Figure S7 | |||

| CP | 73.6±1.5 | Figure S7 | |||

| 74.7±0.8c | average | ||||

| 6H-hexahydro-2-coumaranone | BP | 327-537 | 56.3±1.7 | 64.3±2.3 | Table S4 |

| [6051-03-2] | |||||

| 6H-hexahydro-3-coumaranone | BP | 353-626 | 54.2±0.7 | 65.2±2.3 | Table S4 |

| [1206676-08-5] | CP | 62.5±1.5 | Figure S8 | ||

| CP | 63.0±1.5 | Figure S8 | |||

| CP | 62.2±1.5 | Figure S8 | |||

| 62.9±0.8c | average | ||||

| 6H-hexahydro-phthalide | BP | 337-503 | 72.3±0.8 | 77.6±1.3 | Table S4 |

| [2611-01-0] | |||||

| octahydro-benzofuran-2-ol | CP | 66.5±2.0 | Figure S9 | ||

| [36871-99-5] | CP | 67.2±2.0 | Figure S9 | ||

| 66.9±1.4c | average | ||||

| 8H-octahydro-benzofuran-3-ol | BP | 354-513 | 63.8±1.6 | 73.2±2.5 | Table S4 |

| [99769-38-7] | CP | 73.0±2.0 | Figure S9 | ||

| CP | 73.5±2.0 | Figure S9 | |||

| 73.2±1.2c | average | ||||

| 8H-octahydro-isobenzofuran-1-ol | CP | 66.7±2.0 | Figure S9 | ||

| [59901-42-7] | CP | 66.5±2.0 | Figure S9 | ||

| 66.6±1.4c | average | ||||

| methoxy-benzene [100-66-3] | 46.4±0.2 | [24] | |||

| methoxy-cyclohexane [931-56-6] | 43.0±0.5 | [25] |

| CAS | Compound | Jxa | (298.15 K)exp b | (298.15 K)calcc | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 109-99-9 | tetrahydrofuran | 611 | 32.6±0.2 [33] | 33.1 | -0.5 |

| 110-00-9 | furan | 468 | 27.7±0.2 [33] | 27.8 | -0.1 |

| 1191-99-7 | 2,3-dihydrofuran | 564 | 31.3±0.3 [34] | 31.3 | 0.0 |

| 1708-29-8 | 2,5-dihydrofuran | 614 | 32.6±0.2 [33] | 33.2 | -0.6 |

| 534-22-5 | 2-methyl-furan | 603 | 32.7±0.2 [33] | 32.7 | 0.0 |

| 625-86-5 | 2,5-dimethyl-furan | 729 | 37.7±0.2 [33] | 37.4 | 0.3 |

| 3208-16-0 | 2-ethyl-furan | 720 | 37.1±0.2 [33] | 37.1 | 0.0 |

| 271-89-6 | 2,3-benzofuran | 1054 | 48.8±0.3 [12] | 49.4 | -0.6 |

| 496-16-2 | 2,3-dihydrobenzofuran | 1144 | 53.2±0.4 [13] | 52.7 | 0.5 |

| 496-14-0 | phthalan | 1142e | 53.7±0.4 [14] | 52.6 | 1.1 |

| 4265-25-2 | 2-methyl-benzofuran | 1158 | 53.3±1.5 [35] | 53.2 | 0.1 |

| 132-64-9 | dibenzofuran | 1537 | 66.3±0.6 [16] | 67.2 | -0.9 |

| Compound | a | (g) b | (liq) c | (liq) d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,3-benzofuran [271-89-6] | 111.3±0.1 [11] | 328.3 | 215.6 [36] | 217.0 |

| isobenzofuran [270-75-7] | 102.4±8.0 g | 330.7 | 228.3 | |

| 2,3-dihydro-benzofuran [496-16-2] | 119.2±3.0 | 344.1 | 226.4 [36] | 224.9 |

| 1,3-dihydro-isobenzofuran [496-14-0] | 119.2±0.1 [14] | 357.5 | 238.3 | |

| dibenzofuran [132-64-9] | 128.4±2.0 [16] | 384.0 | 248.5 e | 255.6 |

| fluorene [86-73-7] | 136.7±0.4 [37] | 392.0 | 257.8 f | 255.3 |

| 2-coumaranone [553-86-6] | 132.4±3.0 | 353.8 | 221.4 | |

| 3-coumaranone [7169-34-8] | 132.2±5.1 | 355.8 | 223.6 | |

| phthalide [87-41-2] | 144.5±0.2 | 353.6 | 209.1 | |

| furan [110-00-9] | 93.4±0.2 [38] | 272.7 | 176.7 [38] | 179.3 |

| 2,3-dihydro-furan [1191-99-7] | 95.8±0.1 [34] | 294.7 | 198.9 | |

| tetrahydrofuran [109-99-9] | 96.5±0.2 [39] | 301.7 | 203.9 [40] | 205.2 |

| 8H-benzofuran [13054-97-2] | 113.1±2.6 | 365.5 | 252.4 | |

| 8H-isobenzofuran [4743-54-8] | 110.7±1.4 | 364.2 | 253.5 | |

| 12H-dibenzofuran [13054-98-3] | 135.5±4.6 | 430.7 | 295.2 | |

| 12H-fluorene | 136.0±2.7 | 434.7 | 298.7 | |

| 6H-2-coumaranone [6051-03-2] | 127.6±5.6 | 373.9 | 246.3 | |

| 6H-3-coumaronone [1206676-08-5] | 119.8±2.4 | 377.9 | 258.1 | |

| 6H-phthalide [2611-01-0] | 162.5±2.9 | 374.1 | 211.6 | |

| 8H-benzofuran-2-ol [36871-99-5] | 152.0±8.0 g | 385.9 | 233.9 | |

| 8H-benzofuran-3-ol [99769-38-7] | 151.9±5.5 | 390.3 | 238.4 | |

| 8H-isobenzofuran-1-ol [59901-42-7] | 172.0±8.0 g | 387.8 | 215.8 | |

| 1,3-cyclopentadiene [542-92-7] | 274.5 [41] | 182.7 [40] | ||

| cyclopentene [142-29-0] | 289.7 [42] | 201.3 [43] | ||

| cyclopentane [287-92-3] | 292.9 | 204.1 [44] | ||

| indene [95-13-6] | 115.4±0.6 [13] | 335.9 | 214.2 [45] | 220.5 |

| indane [496-11-7] | 110.8±0.8 [13] | 345.9 | 234.4 [45] | 235.1 |

| trans-8H-indene [3296-50-2] | 106.2±0.1 | 371.6 | 258.9 [46] | 265.4 |

| compound | (298 K)/H2 d | (298 K)/H2 | (298 K)/H2 b | (500 K)/H2 b | (298 K) | (298 K) | (298 K) b | (500 K) b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kJ·mol-1 | J·K-1·mol-1 | kJ·mol-1 | kJ·mol-1 | kJ·mol-1 | J·K-1·mol-1 | kJ·mol-1 | kJ·mol-1 | K | |

| (aliphatic)5 | |||||||||

| 1,3-cyclopentadiene | -105.5 | -120.0 | -69.7 | -44.2 | -211.0 | -240.0 | -139.4 | -88.4 | 879 |

| furan | -77.0 | -117.1 | -42.0 | -17.0 | -153.9 | -234.2 | -84.1 | -34.0 | 697 |

| (aromatic)6 + (aliphatic)5 |

|||||||||

| indene | -71.7 | -119.5 | -72.1 | -10.6 | -286.8 | -478.1 | -144.3 | -42.5 | 600 |

| 2,3-benzofuran | -62.1 | -121.5 | -25.8 | -0.1 | -248.2 | -486.0 | -103.3 | -0.5 | 511 |

| 2,3-dihydrobenzofuran | -61.1 | -122.0 | -24.7 | 1.2 | -183.2 | -366.1 | -74.0 | 3.5 | 500 |

| isobenzofuran | -76.1 | -124.4 | -39.0 | -16.0 | -304.3 | -497.6 | -155.9 | -63.9 | 612 |

| 1,3-dihydro-isobenzofuran | -63.3 | -125.6 | -25.9 | -2.6 | -190.0 | -376.9 | -77.6 | -7.7 | 504 |

| (aromatic)6 + (aliphatic)5 +(aromatic)6 |

|||||||||

| fluorene | -59.0 | -123.9 | -22.1 | 4.1 | -354.2 | -743.3 | -132.6 | 24.6 | 477 |

| dibenzofuran | -57.3 | -124.1 | -20.3 | 6.1 | -343.7 | -744.6 | -121.7 | 36.6 | 462 |

| (aromatic)6 + (lactone)5 | |||||||||

| indene | -71.7 | -119.5 | -72.1 | -10.6 | -286.8 | -478.1 | -144.3 | -42.5 | 600 |

| 2-coumaranone | -55.1 | -127.6 | -17.0 | 9.7 | -220.2 | -510.3 | -68.1 | 38.9 | 432 |

| 3-coumaranone | -59.9 | -127.0 | -22.0 | 4.9 | -239.4 | -508.0 | -87.9 | 19.5 | 471 |

| phthalide | -48.7 | -129.0 | -10.3 | 16.8 | -194.9 | -516.1 | -41.0 | 67.1 | 378 |

| open-chained ethers | |||||||||

| benzene | -68.5 | -120.3 | -32.6 | -7.0 | -205.4 | -360.9 | -97.8 | -21.1 | 569 |

| methoxy-benzene | -65.6 | -118.9 | -30.1 | -4.6 | -196.8 | -356.8 | -90.4 | -13.7 | 552 |

| diphenyl ether | -68.1 | -126.2 | -30.5 | -3.8 | -408.5 | -757.3 | -182.7 | -22.6 | 539 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).