Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Review of Literature

1.2. Rationale of the Study

1.3. Statement of the Study

1.4. Objectives

- To study the Indian teachers' perception on augmented reality applications at school level.

- To assess the Indian teachers' attitudes on augmented reality applications at school level.

- To investigate the Indian teachers' overall behavior on augmented reality applications at school level.

- To explore the relationship among perceptions, attitudes and behaviors of Indian school teachers towards augmented reality applications.

- To examine the factors of having perceptions, attitudes and behaviour of Indian school teachers towards augmented reality applications at school level.

1.5. Hypotheses

- H1: There would have a significant level of perception among the teachers on augmented reality applications at school level.

- H2: Significant level of attitudes would be explored among the teachers on augmented reality applications at school level.

- H3: There would be a significant level of practices in terms of behaviour among educators towards augmented reality applications at school level.

- H4: Significant level of relationship among perception, attitudes and behaviour would be found among educators towards augmented reality applications.

- H5: Multiple factors would be observed of having perceptions, attitudes and behaviour of Indian school teachers towards augmented reality applications at school level.

1.6. Research Questions

- What are the key factors that influence Indian school teachers' perceptions of augmented reality applications in educational settings?

- How do various demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, teaching experience) influence teachers' attitudes towards the use of augmented reality in schools?

- In what ways do school-level factors (e.g., availability of resources, administrative support, training opportunities) affect teachers' behaviors in implementing augmented reality in their teaching practices?

- Are there any external factors (e.g., curriculum requirements, peer influence, student engagement) that significantly impact the adoption of augmented reality by Indian school teachers?

2. Methodology

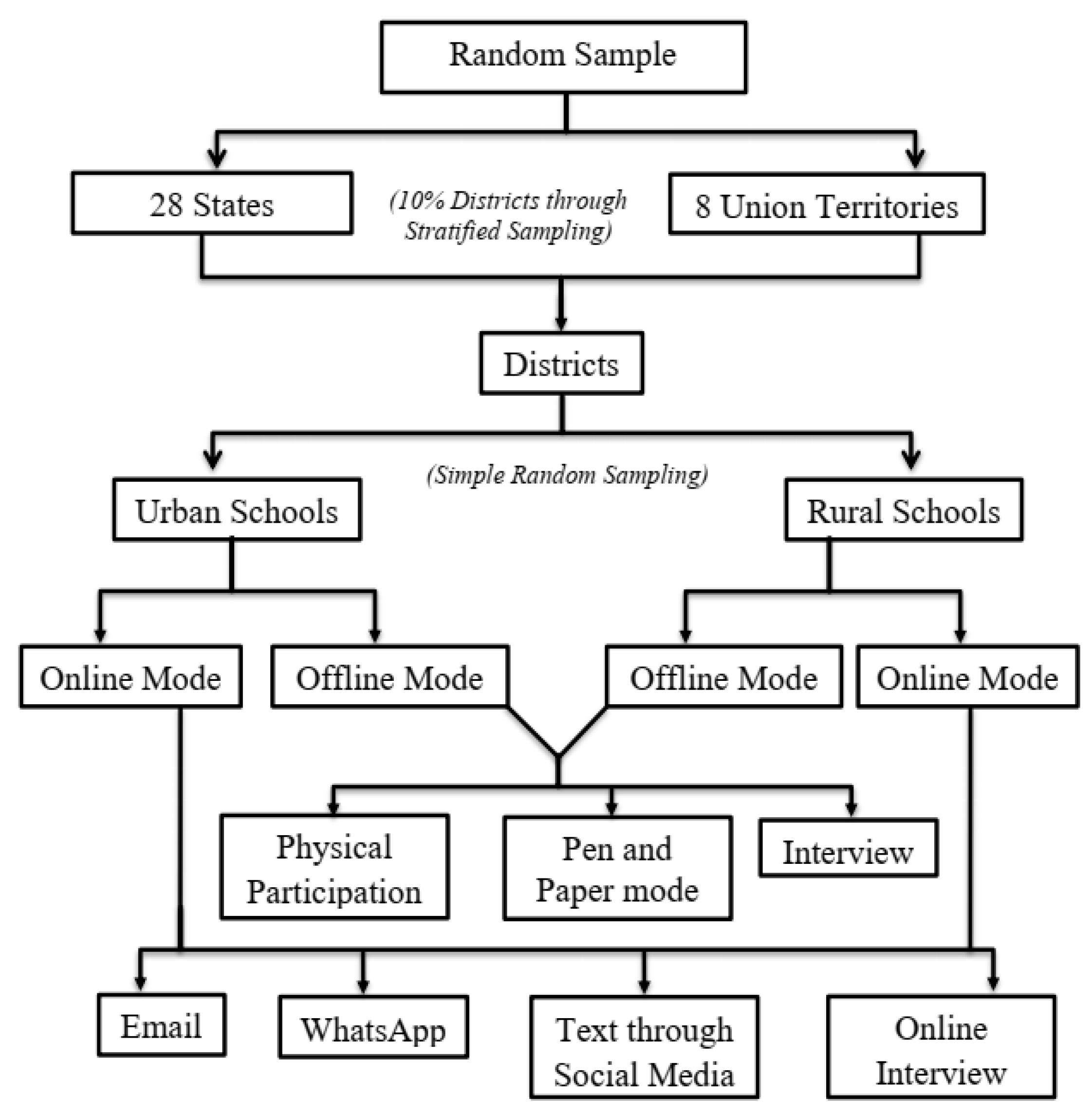

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Tools

2.4. Procedure of Data Collection

3. Result and Analysis

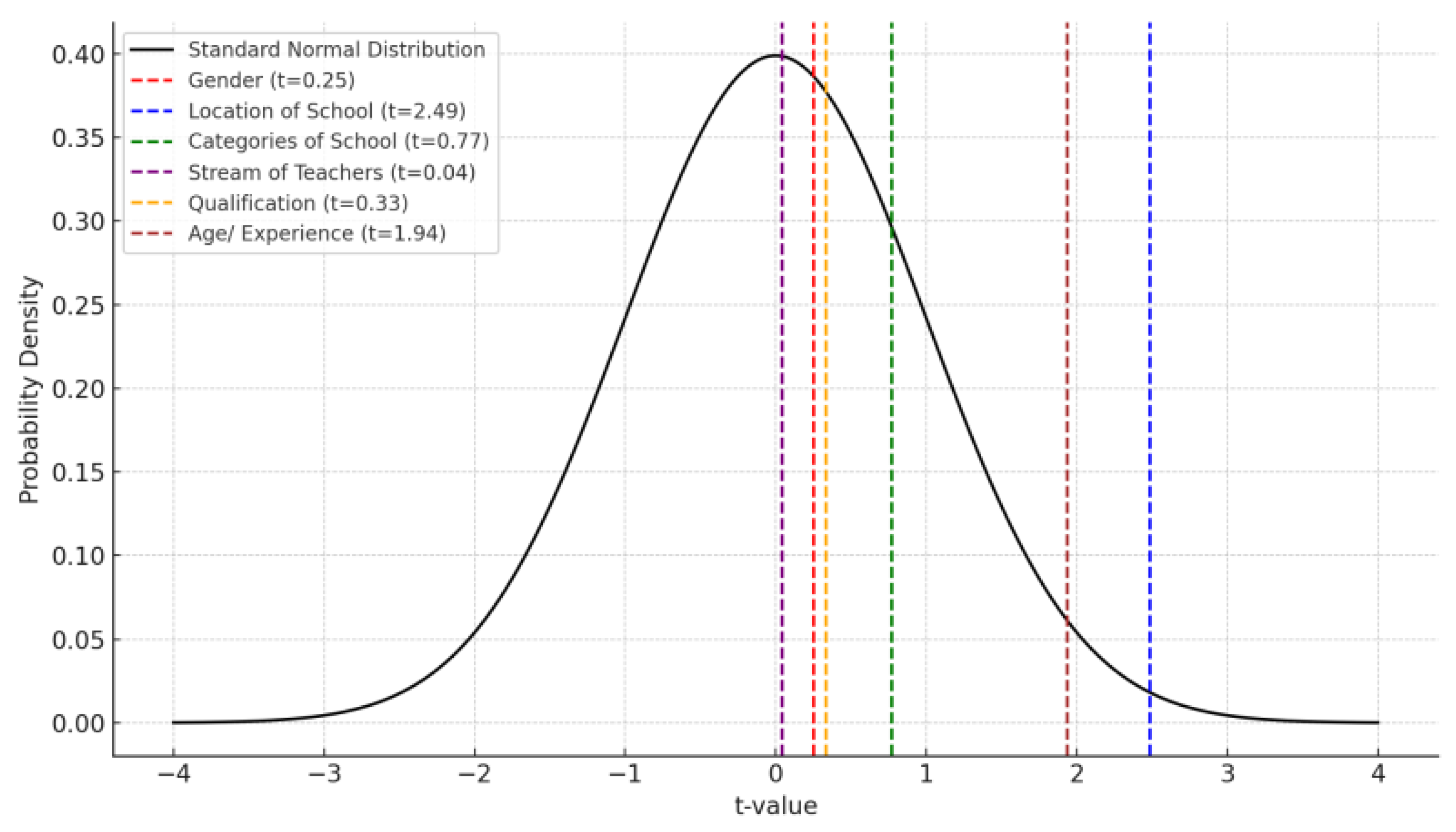

3.1. Hypothesis1

3.2. Hypothesis2

3.3. Hypothesis3

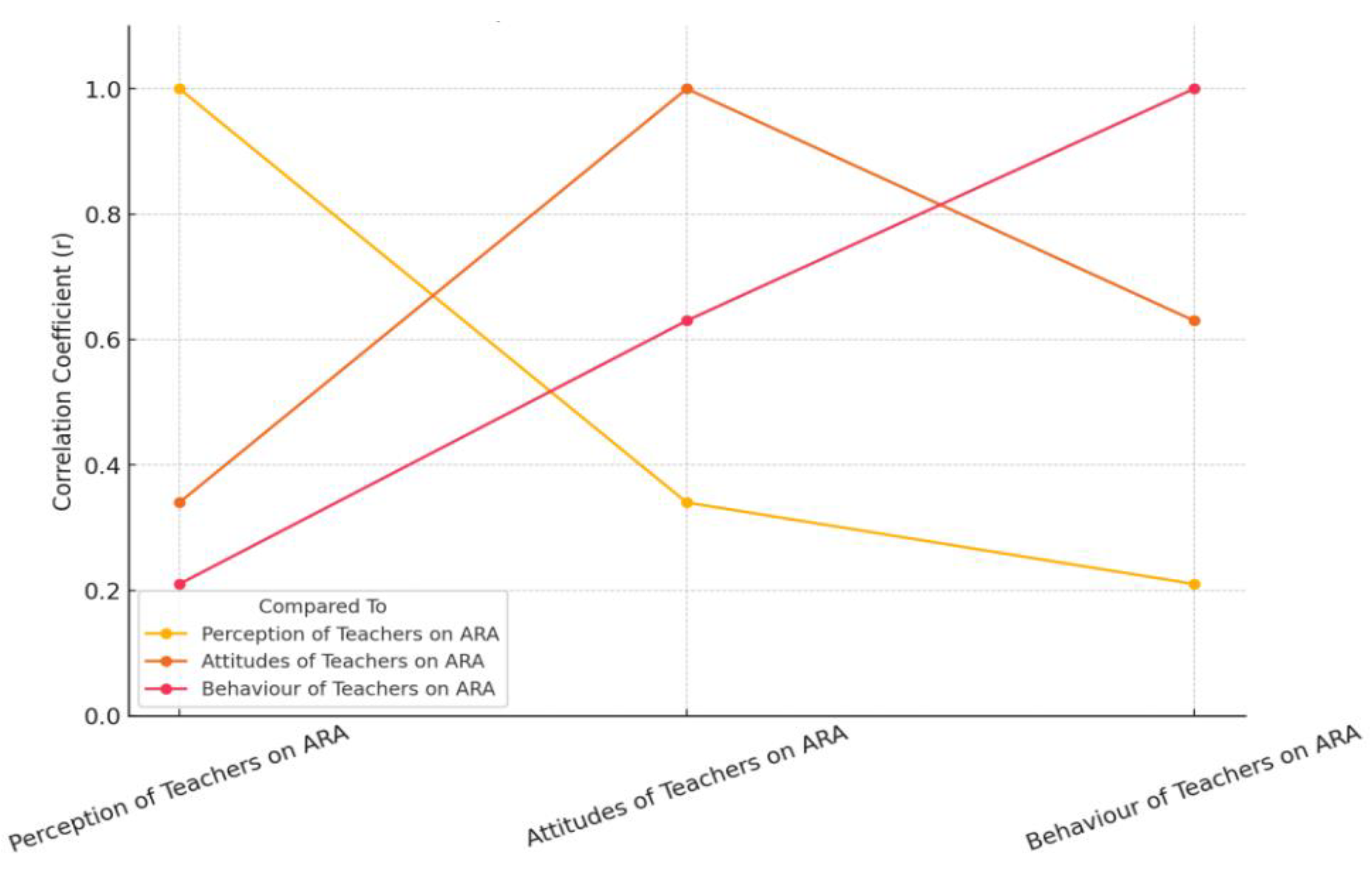

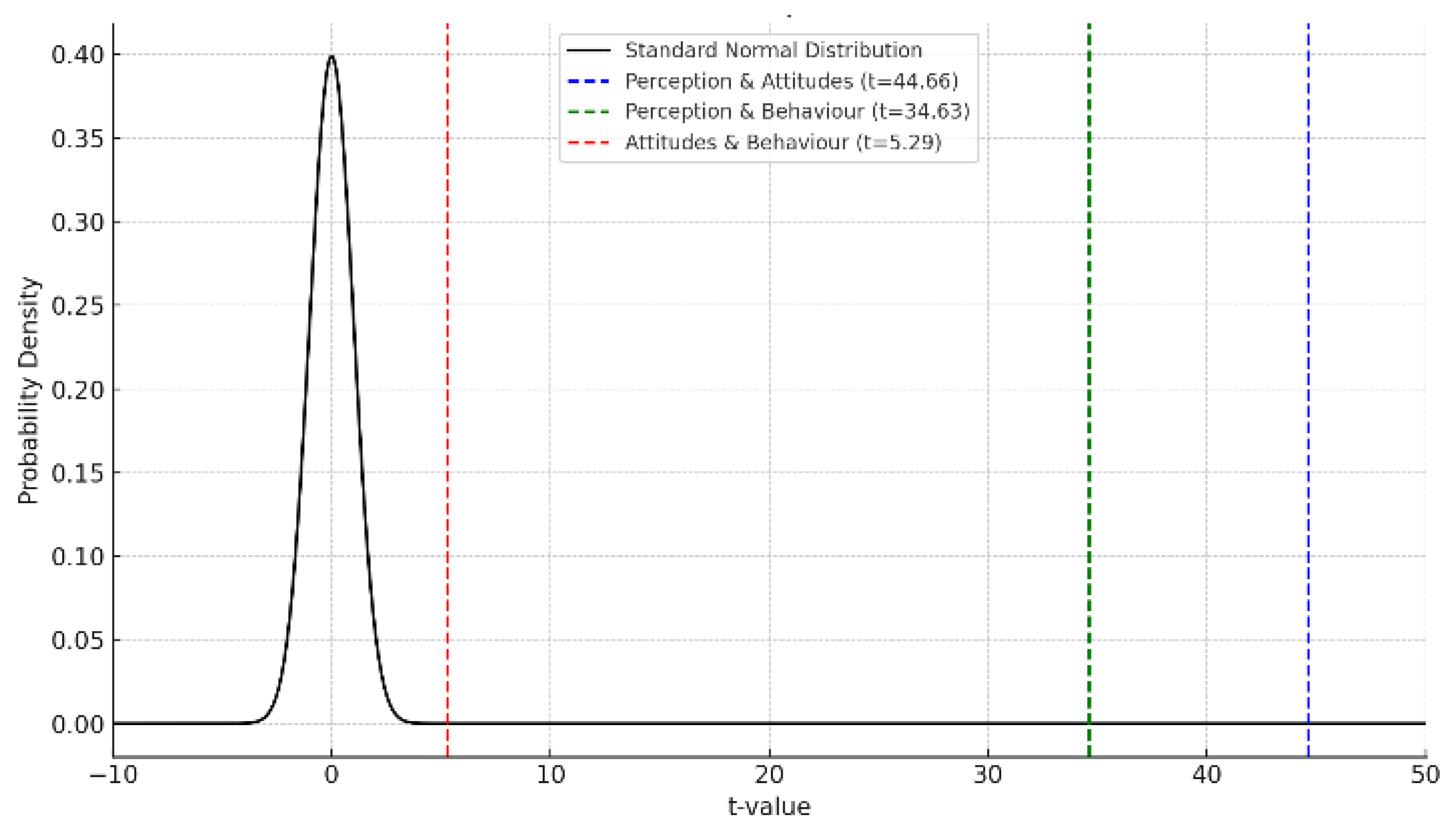

3.4. Hypothesis4

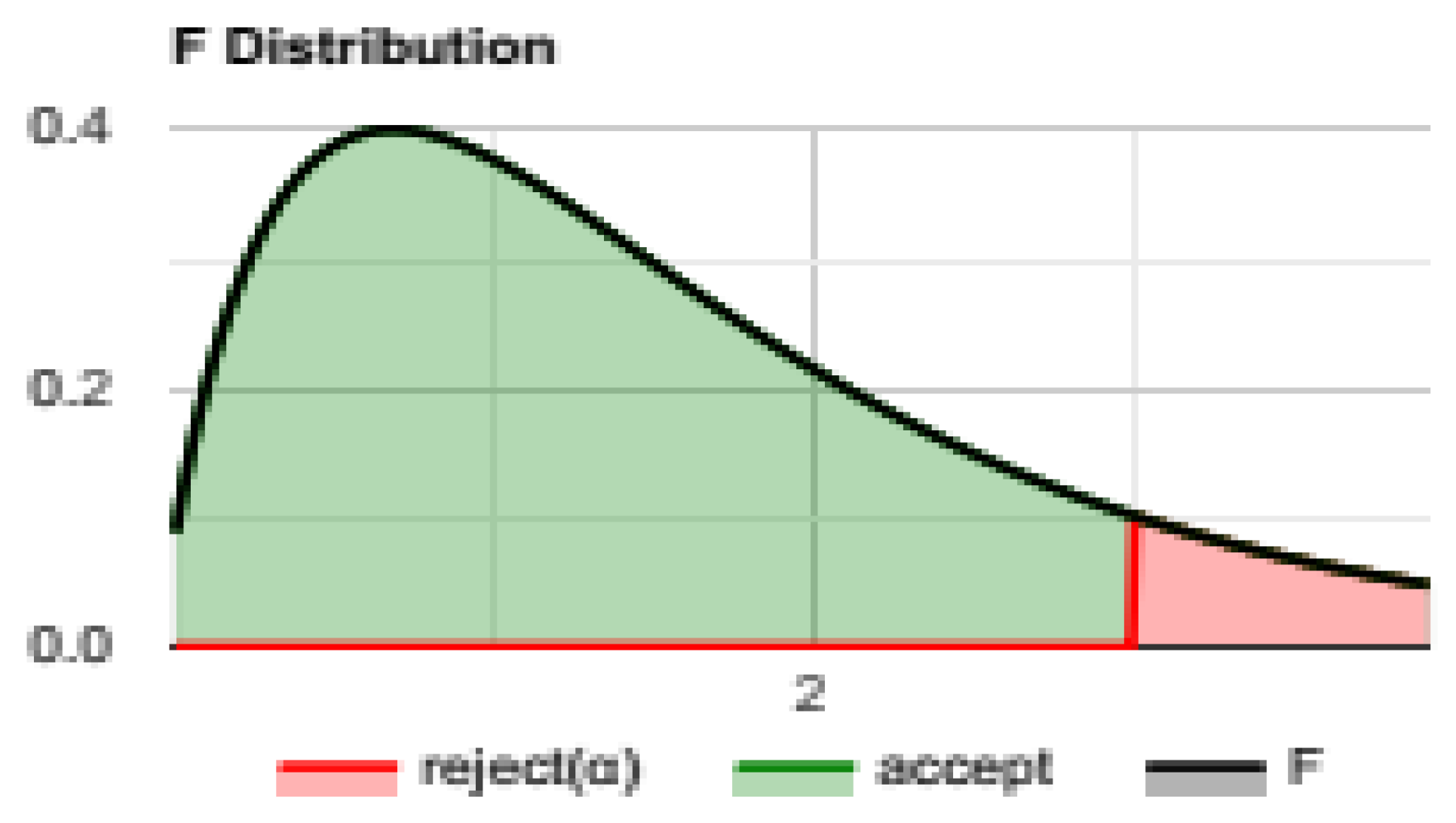

3.5. Hypothesis5 and Research Questions

Qualitative Analysis of Research Questions

3.6. Major Findings

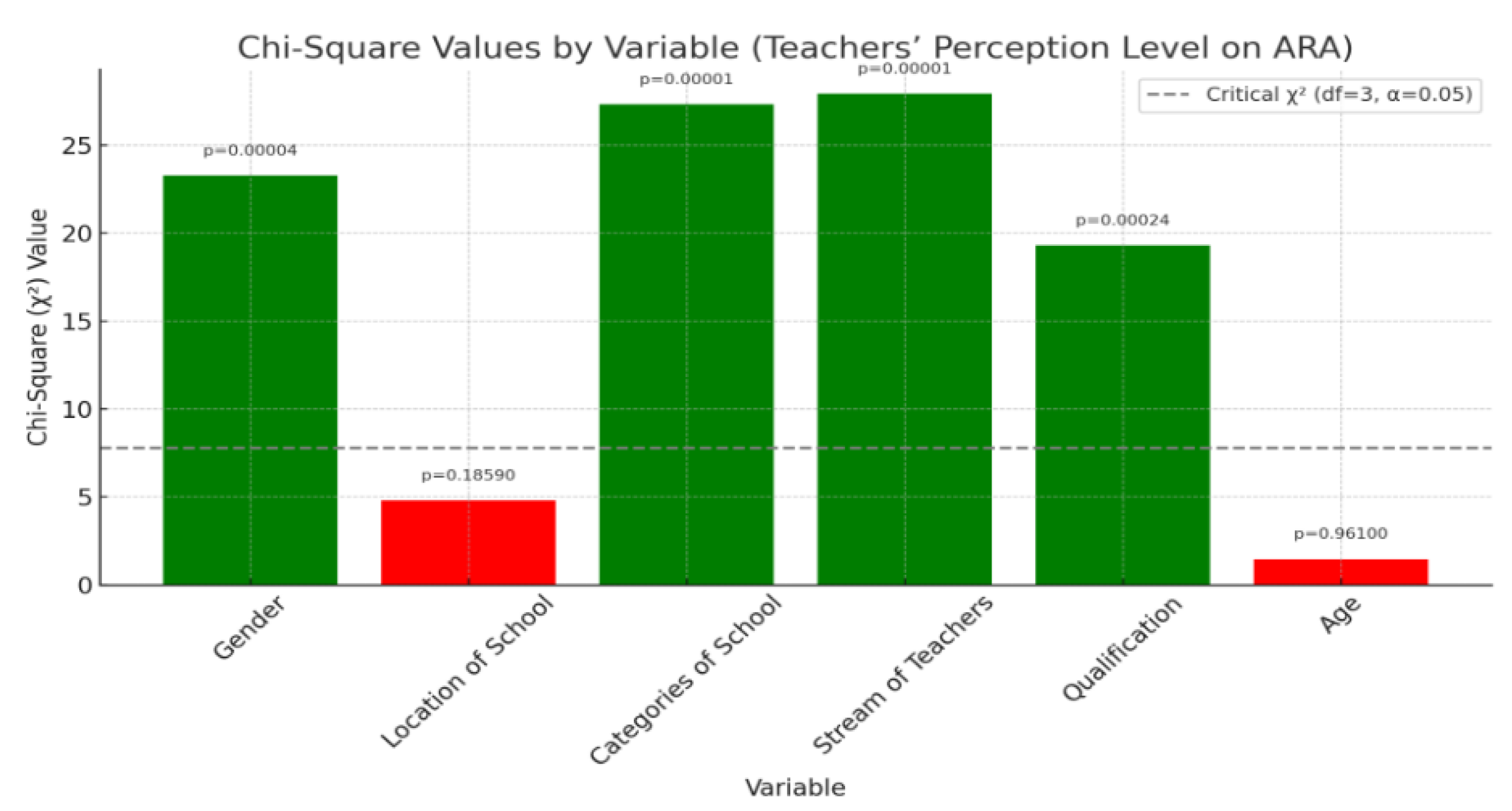

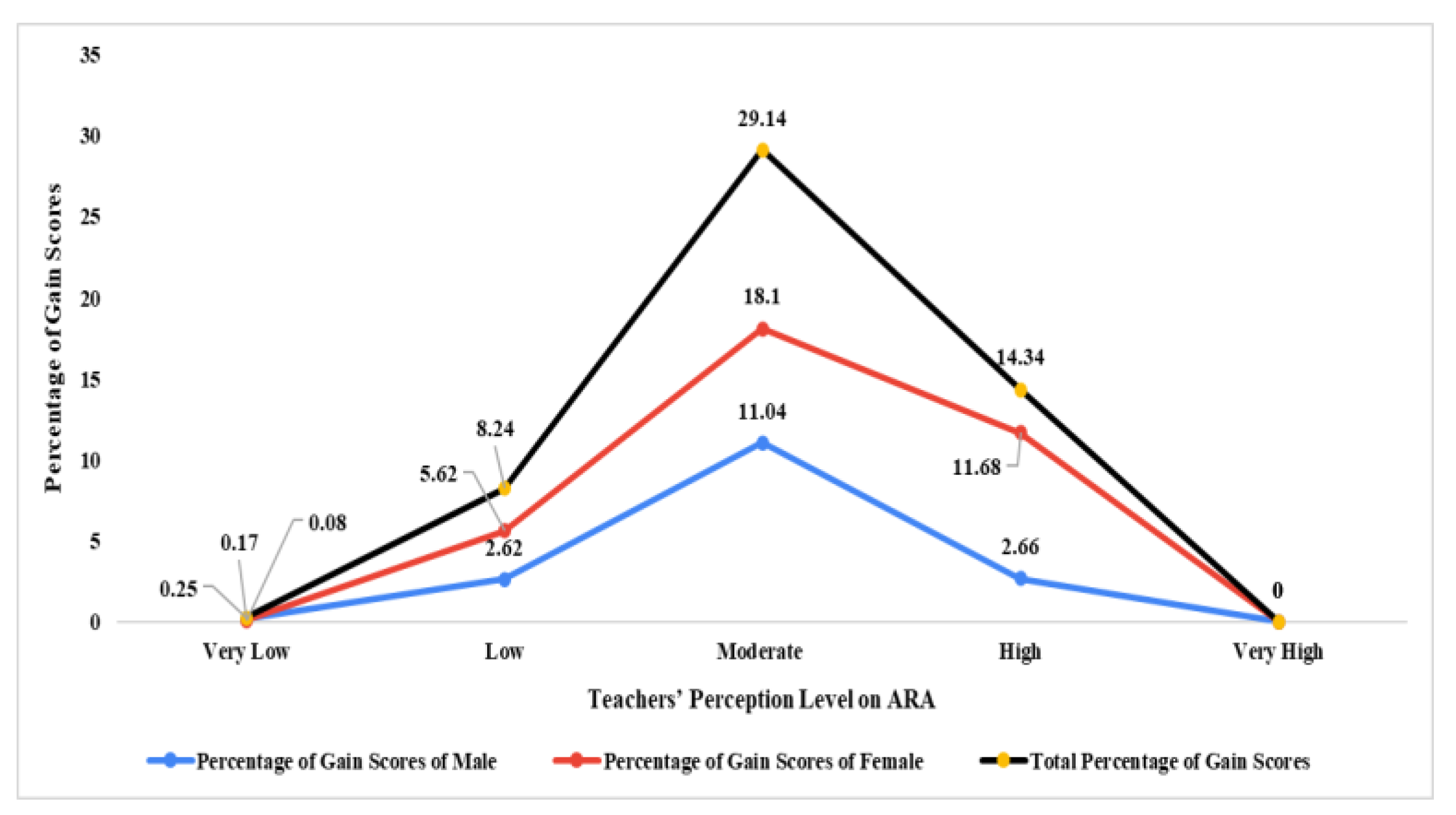

- Majority of the teachers showed moderate to high perception levels toward ARA in which females revealed higher gain scores than males, indicating significant gender differences. Similarly significant perception differences were also observed by school category, stream, designation and qualification, while age, location, and experience showed no effect.

- Maximum number of teachers exhibited high to very high attitudes toward ARA, with females scoring significantly higher, reflecting gender-based differences. Attitudes also varied significantly by school category, and age, favoring females and private schools. However, no significant differences were found across stream, qualification, designation, or experience, indicating overall uniformity.

- Highest number of teachers demonstrated moderate to high behavior levels towards ARA, with females showing higher engagement. Behavior significantly varied by gender, school location, category, stream, qualification, and age, highlighting their influence on AR adoption. However, only school location showed significant mean score differences; other factors showed no significant impact.

- Significant positive correlations exist among teachers’ perception, attitudes, and behaviour on ARA, indicating interconnectedness. Additionally, distinct mean differences were found across these domains, reflecting varied levels of perception, attitude, and behaviour. Overall, a highly significant difference highlights meaningful variation in how teachers engage with ARA across these areas.

- Qualitative findings reveal that AR integration in Indian classrooms faces barriers like limited awareness, low motivation, poor infrastructure, and lack of training. Despite this, teachers show resilience through adaptive strategies. Effective AR use requires administrative support, funding, training, collaboration, and development of discipline-specific, culturally relevant content.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

References

- Abdelmagid, M., Abdullah, N. & Aldaba, A. M. A. (2021). Exploring the acceptance of augmented reality among tesl teachers and students and its effects on motivation level: A case study in Kuwait. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 8(12). 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Abdusselam, M., & Karal, H. (2020). The effect of using augmented reality and sensing technology to teach magnetism in high school physics. Technology, Pedagogy, and Education, 29(4), 407-424. [CrossRef]

- Abed, S. S. (2021). Examining augmented reality adoption by consumers with highlights on gender and educational-level differences. Review of International Business and Strategy, 31(3), 397-415. [CrossRef]

- Aboudahr, S. M. F. M., Govindarajoo, M. V., Olowoselu, A., & Sani, R. M., (2023). Investigating moderating influence of gender on augmented reality and students satisfaction: Experiences in cultures and linguistic diversity. Asian Journal of University Education (AJUE), 19(3), 447-461.

- Aggarwal, D. (2018). Bring your own device (BYOD) to the classroom: A technology to promote green education. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews (IJRAR), 5(3).

- Aguayo, C., Cochrane, T., & Narayan, V. (2017). Key themes in mobile learning: Prospects for learner-generated learning through AR and VR. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(6), 27-40. [CrossRef]

- Akcayır, M., & Akcayır, G. (2017). Advantages and challenges associated with augmented reality for education: A systematic review of the literature. Educational Research Review, 20, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Akçayır, M., Akçayır, G., Pektaş, H. M., & Ocak, M. A. (2016). Augmented reality in science laboratories: The effects of augmented reality on university students’ laboratory skills and attitudes toward science laboratories. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 334-342. [CrossRef]

- Akinradewo, O., Hafez, M., Aliu, J., Oke, A., Aigbavboa, C., & Adekunle, S. (2025). Barriers to the adoption of augmented reality technologies for education and training in the built environment: A developing country context. Technologies, 13(2), 62. [CrossRef]

- Alagood, J., Prybutok, G., & Prybutok, V. R. (2023). Navigating privacy and data safety: The implications of increased online activity among older adults post-covid-19 induced isolation. Information, 14(6), 346. [CrossRef]

- Al-Akloby, S. B. S. F. (2023). The degree of using augmented reality technology among students of the optimum investment project for teaching personnel program and the difficulties they face at Al-Shaqra University. Journal of the College of Education for Women, 34(2), 30-47. [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, N., Cheng, L., Al-Samarraie, H., Yousef, R., Alzahrani, A. I., & Sarsam, S. M. (2020). Challenges and prospects of virtual reality and augmented reality utilization among primary school teachers: A developing country perspective. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 66, 100876. [CrossRef]

- Alam, A., & Mohanty, A. (2023). Educational technology: Exploring the convergence of technology and pedagogy through mobility, interactivity, AI, and learning tools. Cogent Engineering, 10(2), 2283282. [CrossRef]

- Alamäki, A., Dirin, A., & Suomala, J. (2021). Students' expectations and social media sharing in adopting augmented reality. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 38(2), 196-208. [CrossRef]

- Al-Anazi, M. N., & Khalaf, M. H. R. (2023). The effect of using augmented reality technology on the cognitive holding power and the attitude towards it among middle school students in Al-Qurayyat Governorate, Saudi Arabia. Information Sciences Letters, 12(2), 1053-1067. [CrossRef]

- Albishri, B., & Blackmore, K. L. (2025). Duality in barriers and enablers of augmented reality adoption in education: A systematic review of reviews. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 22(2), 167-191. [CrossRef]

- AlGerafi, M. A. M., Zhou, Y., Oubibi, M., & Wijaya, T. T. (2023). Unlocking the potential: A comprehensive evaluation of augmented reality and virtual reality in education. Electronics, 12(18), 3953. [CrossRef]

- Alhassn, I., Asiamah, N., Opuni, F. F., & Alhassan, A. (2022). The Likert scale: Exploring the unknowns and their potential to mislead the world. UDS International Journal of Development, 9(2), 867-880. [CrossRef]

- Alkhabra, Y. A., Ibrahem, U. M., & Alkhabra, S. A. (2023). Augmented reality technology in enhancing learning retention and critical thinking according to STEAM program. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Alkhattabi, M. (2017). Augmented reality as e-learning tool in primary schools’ education: Barriers to teachers’ adoption. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Almaleki, D. (2022). Designing a tool for evaluating employing augmented reality technology to distinguish between similar alphabets. International Journal of education and science, 39, 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, E. (2023). Augmented reality facilitates teachers ‘teaching and students' learning in higher education. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 10(11). 86-90. [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, T. (2021). Comparison of augmented reality and conventional teaching on special needs students’ attitudes towards science and their learning outcomes. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 20(4), 558-572. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shahrani, H. A. (2021). Examining Saudi secondary school teachers’ acceptance of augmented reality technology. Islamic University Journal for Educational and Social Sciences, 5(2), 153-179.

- Al-Shahrani, H. A. M., & Asiri, A. M. S. (2023a). The degree of secondary school teachers’ use of augmented reality technology in education from their point of view and their attitudes towards it and its relationship to some variables. Alustath Journal for Human and Social Sciences, 62(3), 56-80. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shahrani, H. A. M., & Asiri, A. M. S. (2023b). The reality of using augmented reality technology by secondary school female teachers in Abha city in teaching from their point of view. Journal of Educational and Social Research 13(3), 46-59. https://DOI:10.36941/jesr-2023-0056.

- Alzahrani, N. M. (2020). Augmented reality: A systematic review of its benefits and challenges in e-learning contexts. Applied sciences, 10(16), 5660. [CrossRef]

- Amores-Valencia, A., Burgos, D., & Branch-Bedoya, J. W. (2023). The impact of augmented reality (AR) on the academic performance of high school students. Electronics, 12(10), 2173. [CrossRef]

- Anju, V., & Thiyagu, K. (2023). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions about augmented reality (AR) applications in science learning. Indian Journal of Educational Technology, 5(2), 115–132.

- Antonioli, M., Blake, C., & Sparks, K. (2014). Augmented reality applications in education. The Journal of technology studies, 40(2), 96-107. [CrossRef]

- Arena, F., Collotta, M., Pau, G., & Termine, F. (2022). An overview of augmented reality. Computers, 11(2), 28. [CrossRef]

- Arici, F., Yilmaz, R. M., & Yilmaz, M. (2021). Affordances of augmented reality technology for science education: Views of secondary school students and science teachers. Hum Behav & Emerg Tech, 3(5), 1153-1171. [CrossRef]

- ARToolKit. (2024, October 9). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARToolKit.

- Asbulah, L. H., Sahrim, M., Soad, N. F. A. M., Rushdi, N. A. A. M., & Deris, M. A. H. M. (2022). Teachers’ attitudes towards the use of augmented reality technology in teaching Arabic in primary school Malaysia. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications,13(10), 465-474. [CrossRef]

- Ascher-Svanum, H., Novick, D., Haro, J. M., Aguado, J., & Cui, Z. (2013). Empirically driven definitions of “good,” “moderate,” and “poor” levels of functioning in the treatment of schizophrenia. Quality of Life Research, 22(8), 2085-2094. [CrossRef]

- Ashley-Welbeck, A., & Vlachopoulos, D. (2020). Teachers’ perceptions on using augmented reality for language learning in primary years programme (PYP) education. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(12), 116-135. [CrossRef]

- Asiri, M. M., & El-aasar, S. A. (2022). Employing technology acceptance model to access the reality of using augmented reality applications in teaching from teachers’ point of view in Najran. Journal of positive school psychology, 6(2), 5241-5255.

- Asokan, V., & Ponnusamy, P. (2023). Mobile augmented reality in teaching upper primary school science: Perspectives of subject handling teachers. Indian Journal of Educational Technology, 5(2), 67–74.

- Atalay, N. (2022). Augmented reality experiences of preservice classroom teachers in science teaching. International Technology and Education Journal, 6(1), 28-42.

- Ateş, H., & Garzón, J. (2023). An integrated model for examining teachers’ intentions to use augmented reality in science courses. Education and Information Technologies, 28(2), 1299-1321. [CrossRef]

- Bandla, S., Lella, S., Kola, A., Parvathaneni, K. M., & Rani, J. (2024). Association of anxiety, depression and sleep quality with binge-watching behavior in college students–An observational study. Archives of Mental Health, 25(2), 107-111. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, G., & Walunj, S. (2019, December 09-11). Exploring in-service teachers' acceptance of augmented reality. In 2019 IEEE Tenth international conference on technology for education (T4E) (pp. 186-192). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Bangga-Modesto, D. (2024). Examining student perception on mobile augmented reality integration, gender differences, learning styles, feedback, challenges, and opportunities in an online physics class. Science Education International, 35(1), 2-12.

- Basumatary, D., & Maity, R. (2024). The potential of augmented reality in Indian rural primary education. IEEE Potentials, 43(4), 26-31. [CrossRef]

- Belisario, J. S. M., Jamsek, J., Huckvale, K., O'Donoghue, J., Morrison, C. P., & Car, J. (2015). Comparison of self-administered survey questionnaire responses collected using mobile apps versus other methods. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 7, 1-99. [CrossRef]

- Berame, J. S., Bulay, M. L., Mercado, R. L., Ybanez, A. R. C., Aloyon, G. C. A., Dayupay, A. M. F., ... & Jalop, N. J. (2022). Improving grade 8 students’ academic performance and attitude in teaching science through augmented reality. American Journal of Education and Technology, 1(3), 62-72. [CrossRef]

- Berson, M., Ng, D., Shin, J., & Jenkinson, J. (2018). Assessing augmented reality in helping undergraduate students to integrate 2D and 3D representations of stereochemistry. The Journal of Biocommunication, 42(1), e4. [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, A. K. (2015). Application and performance of Google Forms for online data collection and analysis: A case of North Eastern Region of India. Indian Journal of Extension Education, 51(3 & 4), 49-53.

- Bhattacharya, S., Sau, A., Bera, P., Sardar, C., Chaudhuri, S., & Thakur, N. (2025). Teachers and technology: A comprehensive study on augmented reality awareness among school educators in India. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Management, 10(45s), 233-252. [CrossRef]

- Bock, D. E., Velleman, P. F., & Veaux, R. D. D. (2010). Stats: Modeling the world: AP Edition. Addison Wesley, Boston, MA.

- Buchner, J., Krüger, J. M., Bodemer, D., & Kerres, M. (2022). Teachers’ use of augmented reality in the classroom: Reasons, practices, and needs. In Proceedings of the 16th international conference of the learning sciences-ICLS 2022, (pp. 1133-1136). International Society of the Learning Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J., Barroso-Osuna, J., Llorente-Cejudo, C., & Fernández-Martínez, M. D. M. (2019a). Educational uses of augmented reality (AR): Experiences in educational science. Sustainability, 11(18), 4990. [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J., Fernández-Batanero, J. M., & Barroso-Osuna, J. (2019b). Adoption of augmented reality technology by university students. Heliyon, 5(5), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S., Chiang, F. K., & Wang, X. (2013). Using the augmented reality 3D technique for a convex imaging experiment in a physics course. International Journal of Engineering Education, 29(4), 858-865.

- Cao, W., & Yu, Z. (2023). Retracted article: The impact of augmented reality on student attitudes, motivation, and learning achievements—a meta-analysis (2016–2023). Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10,352, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Calle, R., Jiménez-Vivas, A., Castro, R. P., Álvarez, M. I. C., & Jenaro, C. (2022). Perceived benefits of future teachers on the usefulness of virtual and augmented reality in the teaching-learning process. Education Sciences, 12(12), 855. [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Galvis, P. A., Mendoza-Moreno, M. A., & Rodriguez-Hernandez, A. A. (2017). Educational and cultural environments enriched using augmented reality technology. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences, 4(8), 52-59.

- Cetin, H. (2022). a systematic review of studies on augmented reality based applications in primary education. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 10(2), 110-121. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., & Thakur, N. (2024). Reflections of adult learners on binge-watching and its detrimental impact on the environment in West Bengal, India. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2428895. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. Y., Binali, T., Liang, J. C., Chiou, G. L., Cheng, K. H., Lee, S. W. Y., & Tsai, C. C. (2022). Ten years of augmented reality in education: A meta-analysis of (quasi-) experimental studies to investigate the impact. Computers & Education, 191, 104641. [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. E., Chang, C. T., Hou, H. T., Sung, Y. T., Chao, H. L., & Lee, C. M. (2014). Development and behavioral pattern analysis of a mobile guide system with augmented reality for painting appreciation instruction in an art museum. Computers & education, 71(1), 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Perez, J., & Iparraguirre-Villanueva, O. (2025). Digital inclusion and accessibility through augmented reality mobile technologies in education: A systematic review. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 19(4), 48-64. https://10.3991/ijim.v19i04.52845.

- Chen, S. Y. (2022). To explore the impact of augmented reality digital picture books in environmental education courses on environmental attitudes and environmental behaviors of children from different cultures. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 1063659. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K. H., & Tsai, C. C. (2014). Children and parents' reading of an augmented reality picture book: Analyses of behavioral patterns and cognitive attainment. Computers & Education, 72, 302-312. [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J., Lee, S., Crooks, S. M., & Song, J. (2012). An investigation of mobile learning readiness in higher education based on the theory of planned behavior. Computers & Education, 59(3), 1054-1064. [CrossRef]

- Cipresso, P., Meriggi, P., Carelli, L., Solca, F., Meazzi, D., Poletti, B., ... & Silani, V. (2011, May 23). The combined use of brain computer interface and eye-tracking technology for cognitive assessment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In 2011 5th International conference on pervasive computing technologies for healthcare (Pervasive Health) and workshops (pp. 320-324). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Contreras, G., de Cabo, R. M., & Gimeno, R. (2024). Women who LinkedIn: The gender networking gap among executives. European Management Journal, 43(3), 383-398. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2023). Revisiting mixed methods research designs twenty years later. In Poth C. (Ed.), Sage handbook of mixed methods designs (pp. 623–635). Sage Publications.

- Cyril, N., Thoe, N. K., Sinniah, D. N., Rajoo, M., Sinniah, S., Adzmin, W. N.,... & Shukor, S. A. (2022). Exploring the effect of science teachers’ age group on technological knowledge, technological content and pedagogical knowledge in augmented reality. Dinamika Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Dasar, 14(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M. M. O., Teixeira, J. M. X. N., Cavalcante, P. S., & Teichrieb, V. (2019). Perspectives on how to evaluate augmented reality technology tools for education: A systematic review. Journal of the Brazilian Computer Society, 25(3), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Dahri, N. A., Yahaya, N., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Noman, H. A., Alblehai, F., Kamin, Y. B., ... & Al-Adwan, A. S. (2024). Investigating the motivating factors that influence the adoption of blended learning for teachers’ professional development. Heliyon, 10(15). [CrossRef]

- Dejonckheere, M., Lindquist-Grantz, R., Toraman, S., Haddad, K., & Vaughn, L. M. (2019). Intersection of mixed methods and community-based participatory research: A methodological review. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(4), 481-502. [CrossRef]

- De-Lima, C. B., Walton, S., & Owen, T. (2022). A critical outlook at augmented reality and its adoption in education. Computers and Education Open, 3, 100103. [CrossRef]

- Dembe, H. A. (2024). The integration of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) in classroom settings. Research Invention Journal of Engineering and Physical Sciences, 3(1), 102-113.

- Dickmann, T., Opfermann, M., Dammann, E., Lang, M., & Rumann, S. (2019). What you see is what you learn? The role of visual model comprehension for academic success in chemistry. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 20(4), 804-820. [CrossRef]

- Di-Fuccio, R., Kic-Drgas, J., & Woźniak, J. (2024). Co-created augmented reality app and its impact on the effectiveness of learning a foreign language and on cultural knowledge. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Dirin, A., Alamäki, A., & Suomala, J. (2019). Gender differences in perceptions of conventional video, virtual reality and augmented reality. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM), 13(6), 93-102. [CrossRef]

- Do, H. N., Shih, W., & Ha, Q. A. (2020). Effects of mobile augmented reality apps on impulse buying behavior: An investigation in the tourism field. Heliyon, 6(8). https://10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04667.

- Dsouza, N. P., & Hemmige, B. D. (2023). Teacher’s perspective on using augmented reality in the classroom to teach scientific concepts. Iconic Research And Engineering Journals, 6(7), 207-213.

- Dunleavy, M., Dede, C., & Mitchell, R. (2009). Affordances and limitations of immersive participatory augmented reality simulations for teaching and learning. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 18(1), 7-22. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R., Mantri, A., & Singh, G. (2022). Assess teachers’ attitude towards mobile augmented reality systems for teaching digital electronics course. ECS transactions, 107(1), 7631-7638. [CrossRef]

- Egunjobi, D., & Adeyeye, O. J. (2024). Revolutionizing learning: The impact of augmented reality(AR) and artificial intelligence (AI on education). International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 5(10), 1157-1170. [CrossRef]

- Elford, D., Lancaster, S. J., & Jones, G. A. (2022). Exploring the effect of augmented reality on cognitive load, attitude, spatial ability, and stereochemical perception. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 31(3), 322-339. [CrossRef]

- Eutsler, L., & Long, C. S. (2021). Preservice teachers’ acceptance of virtual reality to plan science instruction. Educational Technology & Society, 24(2), 28-43.

- Ewais, A., & Troyer, O. D. (2019). A usability and acceptance evaluation of the use of augmented reality for learning atoms and molecules reaction by primary school female students in Palestine. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(7), 1643-1670. [CrossRef]

- Faqih, K. M., & Jaradat, M. I. (2021). Integrating TTF and UTAUT2 theories to investigate the adoption of augmented reality technology in education: Perspective from a developing country. Technology in Society, 67, 101787. [CrossRef]

- Finkler, A. (2010). Goodness of fit statistics for sparse contingency tables. arXiv preprint arXiv:1006.2287. [CrossRef]

- Gajbhiye, D. R. S. (2024). Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) in libraries. Royal International Global Journal of Advance and Applied Research, 1(5), 8–10. [CrossRef]

- Garratt, A. M., Helgeland, J., & Gulbrandsen, P. (2011). Five-point scales outperform 10-point scales in a randomized comparison of item scaling for the patient experiences questionnaire. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 64(2), 200-207. [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, N., van der Veer, S. N., Wilson, P., & Dowding, D. (2022). How, for whom, and in which contexts or conditions augmented and virtual reality training works in upskilling health care workers: realist synthesis. JMIR serious games, 10(1), e31644. [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, Y., & Kyza, E. A. (2017, June). Investigating immersion in relation to students’ learning during a collaborative location-based augmented reality activity [Paper presentation]. International conference of computer supported collaborative learning, PA, International Society of the Learning Sciences, Philadelphia.

- Ghobadi, M., Shirowzhan, S., Ghiai, M. M., Ebrahimzadeh, F. M., & Tahmasebinia, F. (2023). Augmented reality applications in education and examining key factors affecting the users’ behaviors. Education Sciences, 13(1), 10. [CrossRef]

- Giard, F., & Guitton, M. J. (2016). Spiritus ex machina: Augmented reality, cyberghosts and externalised consciousness. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(B), 614-615. [CrossRef]

- Giasiranis, S., & Sofos, L. (2016). Production and evaluation of educational material using augmented reality for teaching the module of “representation of the information on computers” in junior high school. Creative Education, 7(9), 1270-1291. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Trigueros, I. M., & Aldecoa, C. Yde. (2021). The digital gender gap in teacher education: The TPACK framework for the 21st century. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(4), 1333-1349. [CrossRef]

- Grinshkun, A. V., Perevozchikova, M. S., Razova, E. V., & Khlobystova, I. Y. (2021). Using methods and means of the augmented reality technology when training future teachers of the digital school. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 10(2), 358-374. [CrossRef]

- Gusteti, M. U., Musdi, E., Dewata, I., & Rasli, A. M. (2025). A ten-year bibliometric study on augmented reality in mathematical education. European Journal of Educational Research, 14(3), 723-741. [CrossRef]

- Habig, S. (2020). Who can benefit from augmented reality in chemistry? Sex differences in solving stereochemistry problems using augmented reality. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(3), 629-644. [CrossRef]

- Heintz, M., Law, E .L. C., & Andrade, P. (2021). Augmented reality as educational tool: Perceptions, challenges, and requirements from teachers. In: T. De Laet, R. Klemke, C. Alario-Hoyos, I. Hilliger, & A. Ortega-Arranz (Eds.), Technology-Enhanced Learning for a Free, Safe, and Sustainable World, EC-TEL 2021, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, (pp 315–319), 12884. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Hervás-Gómez, C., Toledo-Morales, P., & Díaz-Noguera, M. D. (2017). Augmented reality applications attitude scale (ARAAS): Diagnosing the attitudes of future teachers. The New Educational Review, 50(4), 215-226. [CrossRef]

- Holly, M., Pirker, J., Resch, S., Brettschuh, S., & Gütl, C. (2021). Designing VR experiences–expectations for teaching and learning in VR. Educational Technology & Society, 24(2), 107-119.

- Holzmann, P., & Gregori, P. (2023). The promise of digital technologies for sustainable entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management, 68, 102593. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H. Y., & Wang, S. K. (2017). Integrating technology: Using Google Forms to collect and analyze data. Science Scope, 40(8), 64-67. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T. C., Chen, C. C., & Chou, Y. W. (2016). Animating eco-education: To see, feel, and discover in an augmented reality-based experiential learning environment. Computers & Education, 96, 72-82. [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, M. B., Portillo, A. U., Cabada, R. Z., & Barrón, M. L. (2020). Impact of augmented reality technology on academic achievement and motivation of students from public and private Mexican schools. A case study in a middle-school geometry course. Computers & Education, 145, 103734. [CrossRef]

- Ibili, E., Resnyansky, D., & Billinghurst, M. (2019). Applying the technology acceptance model to understand maths teachers’ perceptions towards an augmented reality tutoring system. Education and Information Technologies, 24(5), 2653-2675. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S., & Bhatti, Z. A. (2020). A qualitative exploration of teachers’ perspective on smartphones usage in higher education in developing countries. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1), 29. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Jamrus, M. H. M., & Razali, A. B. (2021). Acceptance, readiness and intention to use augmented reality (AR) in teaching English reading among secondary school teachers in Malaysia. Asian Journal of University Education (AJUE), 17(4), 312-326. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H., Zhu, D., Chugh, R., Turnbull, D., & Jin, W. (2025). Virtual reality and augmented reality-supported K-12 STEM learning: Trends, advantages and challenges. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 12827–12863. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educational Researcher, 33,(7) 14-26. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., & Pal, D. K. (2015). Likert scale: Explored and explained. British journal of applied science & technology, 7(4), 396-403. [CrossRef]

- Jung, T., & tom-Dieck, M. C. (Eds.). (2018). Augmented reality and virtual reality: Empowering human, place and business. Springer Cham. [CrossRef]

- Kamarainen, A. M., Metcalf, S., Grotzer, T., Browne, A., Mazzuca, D., Tutwiler, M. S., & Dede, C. (2013). Eco mobile: Integrating augmented reality and probeware with environmental education field trips. Computers and Education, 68, 545-556. [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, S., Shoaib, H. M., Jamjoom, Y., Saleem, M., & Mohammadi, P. (2023). Use of Augmented Reality Application in E-learning System During COVID-19 Pandemic. In: B. Alareeni, & A. Hamdan (Eds.), Explore business, technology opportunities and challenges after the Covid-19 pandemic, ICBT 2022, lecture notes in networks and systems, (pp. 241-251), 495. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Karthick, M., & Shanmugam, P. N. L. (2024). Exploring prospective teachers' awareness and perception of augmented reality (AR): A survey-based study. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(3), 2984-2991. https://Doi:10.53555/kuey.v30i3.8808.

- Kazakou, G., & Koutromanos, G. (2022). Augmented reality smart glasses in education: Teachers’ perceptions regarding the factors that influence their use in the classroom. In: M. E. Auer, & T. Tsiatsos (Eds.), New realities, mobile systems and applications, IMCL 2021, lecture notes in networks and systems, (pp. 145-155), 411. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Kececi, G., Yildirim, P., & Zengin, F. K. ( 2021). Determining the effect of science teaching using mobile augmented reality application on the secondary school students’ attitudes of toward science and technology and academic achievement. Science Education International, 32(2), 137-148. [CrossRef]

- Khan, T., Johnston, K., & Ophoff, J. (2019). The impact of an augmented reality application on learning motivation of students. Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, 2019(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Khukalenko, I. S., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., An, Y., & Iushina, V. D. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of using virtual reality technology in classrooms: A large-scale survey. Education and Information Technologies, 27(8), 11591-11613. [CrossRef]

- Köroğlu, M. (2025). Pioneering virtual assessments: Augmented reality and virtual reality adoption among teachers. Education and Information Technologies, 30(8), 9901-9948. [CrossRef]

- Koutromanos, G., & Jimoyiannis, A. (2022). Augmented reality in education: Exploring Greek teachers’ views and perceptions. In Reis, A., Barroso, J., Martins, P., Jimoyiannis, A., Huang, R.YM., Henriques, R. (Eds.), Technology and Innovation in Learning, Teaching and Education. TECH-EDU 2022. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 1720, (pp. 31-42).. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Kudale, P., & Buktar, R. (2022). Investigation of the impact of augmented reality technology on interactive teaching learning process. International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments (IJVPLE), 12(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S., & Polke, N. (2019). Implementation issues of augmented reality and virtual reality: A survey. In International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (ICICI) 2018 (pp. 853-861). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G., Keramopoulos, E., Diamantaras, K., & Evangelidis, G. (2022). Augmented reality and virtual reality in education: Public perspectives, sentiments, attitudes, and discourses. Education Sciences, 12(11), 798. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Lee, C. F. (2022). Analysis of variance and chi-square tests. In: John, L. & Cheng-Few, L. (Eds.), Essentials of Excel VBA, Python, and R (pp. 331-352). Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Lham, T., Jurmey, P., & Tshering, S. (2020). Augmented reality as a classroom teaching and learning tool: Teachers’ and students’ attitude. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 12(4), 27-35. https://10.9734/AJESS/2020/v12i430318.

- Li, Q., Liu, Q., & Chen, Y. (2023). Prospective teachers’ acceptance of virtual reality technology: a mixed study in rural China. Education and Information Technologies, 28(3), 3217-3248. [CrossRef]

- Liao, C. H. D., Wu, W. C. V., Gunawan, V., & Chang, T. C. (2024). Using an augmented-reality game-based application to enhance language learning and motivation of elementary school EFL students: A comparative study in rural and urban areas. Asia-Pacific Edu Res, 33(2), 307–319. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T. J., Duh, H. B. L., Li, N., Wang, H. Y., & Tsai, C. C. (2013). An investigation of learners' collaborative knowledge construction performances and behavior patterns in an augmented reality simulation system. Computers & Education, 68, 314-321. [CrossRef]

- Linus, A. A., Monsuir, I. A., Elizabeth, F. J., & Justina, A. A. (2025). Teachers' ICT competency and their attitude towards integrating virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) in the classroom in IJEBU-ODE local government area of OGUN state. Journal of Contemporary Research (JOCRES), 4(1), 32-48.

- Liu, E., Cai, S., Liu, Z., & Liu, C. (2023). WebART: Web-based augmented reality learning resources authoring tool and its user experience study among teachers. IEEE Transactions on learning technologies, 16(1), 53-65. https://10.1109/TLT.2022.3214854.

- Makwana, D., Engineer, P., Dabhi, A., & Chudasama, H. (2023). Sampling methods in research: A review. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development, 7(3), 762-768.

- Manna, M. (2023). Teachers as Augmented reality designers: A study on Italian as a foreign language-teacher perception. International Journal of Mobile and blended learning, 15(2), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Marín-Marín, J. A., López-Belmonte, J., Pozo-Sánchez, S., & Moreno-Guerrero, A. J. (2023). Attitudes towards the development of good practices with augmented reality in secondary education teachers in Spain. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 28(4), 1443-1459. [CrossRef]

- Marrahi-Gomez, V., & Belda-Medina, J. (2022). The integration of augmented reality (AR) in education. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 9(12), 475-487. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Gutiérrez, J., Fabiani, P., Benesova, W., Meneses, M. D., & Mora, C. E. (2015). Augmented reality to promote collaborative and autonomous learning in higher education. Computers in human behavior, 51,Par B, 752-761. [CrossRef]

- McNair, C. L., & Green, M. (2016). Preservice teachers’ perceptions of augmented reality. In E. E. Martinez, & J. Pilgrim (Eds.), Literacy Summit Yearbook (2nd ed., pp. 74-81). Specialized Literacy Professionals and Texas Association for Literacy Education.

- Meccawy, M. (2023). Teachers’ prospective attitudes towards the adoption of extended reality technologies in the classroom: Interests and concerns. Smart Learning Environments, 10(36). [CrossRef]

- Meenakshi, P. K., & Indu, H. (2025). Understanding the potential of augmented reality to improve mathematical education. Indian Journal of Educational Technology, 7(1), 190-121.

- Mena, J., Estrada-Molina, O., & Pérez-Calvo, E. (2023). Teachers’ professional training through augmented reality: A literature review. Education Sciences, 13(5), 517. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y., Xu, W., Liu, Z., & Yu, Z. G. (2024). Scientometric analyses of digital inequity in education: problems and solutions. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mercader, C., & Duran-Bellonch, M. (2021). Female Higher Education teachers use digital technologies more and better than they think. Digital Education Review, 40, 172-184. [CrossRef]

- Milad, M., & Fayez, F. (2025). Perception and attitudes towards augmented reality (AR) enhanced academic writing: Satisfaction levels. World Journal of English Language, 15(6), 268-288. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R., & Liu, K. (2023). After the virus: Disaster capitalism, digital inequity, and transformative education for the future of schooling. Education and Urban Society, 55(5), 533-554. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, T., Dutta, R., Tuli, N., & Mantri, A. (2025). Leveraging augmented reality in education involving new pedagogies with emerging societal relevance. Discover Sustainability, 6(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, S., & Husnin, H. (2023). Teachers’ perception of the use of augmented reality (AR) modules in teaching and learning. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(9), 9-34. [CrossRef]

- Mota, J. M., Ruiz-Rube, I., Dodero, J. M., & Arnedillo-Sánchez, I. (2018). Augmented reality mobile app development for all. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 65, 250-260. [CrossRef]

- Mundy, M., Hernandez, J., & Green, M. (2019). Perceptions of the effects of augmented reality in the classroom. Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, 22, 1-15.

- Naveau, P., Huser, R., Ribereau, P., & Hannart, A. (2016). Modeling jointly low, moderate, and heavy rainfall intensities without a threshold selection. Water Resources Research, 52(4), 2753-2769. [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S. A. (2024). Factors influencing student teachers’ intention to use mobile augmented reality in primary science teaching. Education and Information Technologies, 29(12), 15353-15374. [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S. A., Perifanou, M., & Economides, A. A. (2024a). Development and validation of the teachers’ augmented reality competences (TARC) scale. J. Comput. Educ., 11(4), 1041–1060. [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S. A., Perifanou, M., & Economides, A. A. (2024b). Exploring teachers’ competences to integrate augmented reality in education: Results from an international study. Tech Trends, 68(6), 1208–1221 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Nitza, D., & Roman, Y. (2017). Who needs parent-teacher meetings in the technological era?. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(1), 153-162. [CrossRef]

- Nizar, N. N. M., Rahmat, M. K., & Damio, S. M. (2020). Evaluation of pre-service teachers’ actual use towards augmented reality technology through MARLCardio. The International Journal of Academic Research in business and social sciences, 10(11), 1091-1101. [CrossRef]

- Oke, A. E., & Arowoiya, V. A. (2021). Critical barriers to augmented reality technology adoption in developing countries: a case study of Nigeria. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, 20(5), 1320-1333. [CrossRef]

- Okumuş, A., & Savaş, P. (2024). Investigating EFL teacher candidates’ acceptance and self-perceived self-efficacy of augmented reality. Education and Information Technologies, 29(13), 16571-16596. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G., Teixeira, J. G., Torres, A., & Morais, C. (2021). An exploratory study on the emergency remote education experience of higher education students and teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1357-1376. [CrossRef]

- Ozdamli, F., & Hursen, Ç. (2017). An emerging technology: Augmented reality to promote learning. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn., 12(11), 121-137. [CrossRef]

- Palada, B., Chandan, V. S., Gowda, C. P., & Nikitha, P. (2024). The Role of Augmented Reality (AR) in Education. International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET), 12(3), 1400-1408. [CrossRef]

- Paladini, M. (2018, August 14). 3 different types of AR explained: Marker-based, markerless & location. Blippar. https://www.blippar.com/.

- Panakaje, N., Rahiman, H. U., Parvin, S. M. R., Shareena, P., Madhura, K., Yatheen, & Irfana, S. (2024). Revolutionizing pedagogy: Navigating the integration of technology in higher education for teacher learning and performance enhancement. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2308430. [CrossRef]

- Papakostas, C., Troussas, C., Krouska, A., & Sgouropoulou, C. (2022). Exploring users’ behavioral intention to adopt mobile augmented reality in education through an extended technology acceptance model. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(6), 1294–1302. [CrossRef]

- Pasalidou, C., & Fachantidis, N. (2021). Teachers’ perceptions towards the use of mobile augmented reality: The case of Greek educators. In Internet of Things, Infrastructures and Mobile Applications: Proceedings of the 13th IMCL Conference 13 (pp. 1039-1050). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Pasalidou, C., Fachantidis, N., & Koiou, E. (2023). Using augmented reality and a social robot to teach geography in primary school. In P. Zaphiris, & A. Ioannou (Eds.), Learning and collaboration technologies HCII 2023, lecture notes in computer science, (pp. 371-385), 14041. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Peikos, G., & Sofianidis, A. (2024). What is the future of augmented reality in science teaching and learning? An exploratory study on primary and pre-school teacher students’ views. Education Sciences, 14(5), 480. [CrossRef]

- Perifanou, M., Economides, A. A., & Nikou, S. A. (2023). Teachers’ views on integrating augmented reality in education: Needs, opportunities, challenges and recommendations. Future Internet, 15(1), 20. [CrossRef]

- Putiorn, P., Nobnop, R., Buathong, P., & Soponronnarit, K. (2018, November 25-28). Understanding teachers' perception toward the use of an augmented reality-based application for astronomy learning in secondary schools in Northern Thailand. In 2018 Global Wireless Summit (GWS) (pp. 77-81). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Qirom, M. S., & Sukma, L. R. G. (2024). The effect of augmented reality in mathematics education: Gender perspective. In AIP Conference Proceedings, 3220(1). AIP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Radosavljevic, S., Radosavljevic, V., & Grgurovic, B. (2020). The potential of implementing augmented reality into vocational higher education through mobile learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(4), 404-418. [CrossRef]

- Radu, I., Joy, T., Bott, I., Bowman, Y., & Schneider, B. (2022, May 30-June 4). A Survey of Educational Augmented Reality in Academia and Practice: Effects on Cognition, Motivation, Collaboration, Pedagogy and Applications. In 2022 8th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN) (pp. 1-8). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, A. D., Kuswanto, H., Wilujeng, I., Putranta, H., & Ilma, A. Z. (2023). Teachers' perspective toward using augmented reality technology in science learning. Cypriot Journal of Educational Science. 18(1), 215-227. [CrossRef]

- Rahmiati, D., Sarwi, S., Sudarmin, S., & Cahyono, A. N. (2025). The use of augmented reality diorama media in natural and social sciences subjects for fourth grade elementary school. Journal La Edusci, 6(1), 61-78. [CrossRef]

- Ratmaningsih, N., Abdulkarim, A., Sopianingsih, P., Anggraini, D. N., Rahmat, R., Juhanaini, J., Halimatussadiah, R., & Adhitama, F. Y. (2024). Gender equality education through augmented reality (AR)-based flashcards in learning social studies education in schools as an embodiment of sustainable development goals (SDGs). Journal of Engineering Science and Technology, 19(4), 1365-1388.

- Rawat, A. (2025, March 12). AR in education- Use cases, benefits, challenges and more. Appinventiv. https://appinventiv.com/blog/ar-in-education/.

- Rayhan, R. U., Zheng, Y., Uddin, E., Timbol, C., Adewuyi, O., & Baraniuk, J. N. (2013). Administer and collect medical questionnaires with Google documents: a simple, safe, and free system. Applied medical informatics, 33(3), 12-21.

- Raza, S. H., Yousaf, M., Sohail, F., Munawar, R., Ogadimma, E. C., & Siang, J. M. L. D. (2021). Investigating binge-watching adverse mental health outcomes during Covid-19 pandemic: Moderating role of screen time for web series using online streaming. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 1615–1629. [CrossRef]

- Ripsam, M., & Nerdel, C. (2024). Teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy toward augmented reality in chemistry education. Front. Educ., 8:1293571. [CrossRef]

- Robles, B. F. (2017). La utilización de objetos de aprendizaje de realidad aumentada en la enseñanza universitaria de educación primaria. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 9, 90–104.

- Romano, M., Diaz, P., & Aedo, I. (2020). Empowering teachers to create really experiences: The effects on the educational experience. Interactive learning environments, 31(3), 1546-1563. [CrossRef]

- Sáez-López, J. M., Cózar-Gutiérrez, R., González-Calero, J. A., & Gómez-Carrasco, C. J. (2020). Augmented reality in higher education: An evaluation program in initial teacher training. Education Sciences, 10(2), 26. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, D., & Yilmaz, R. M. (2020). The effect of augmented reality technology in middle school students’ achievements and attitudes towards science education. Computers and Education, 144, 103710. [CrossRef]

- Şakir, A. (2025). Augmented reality in preschool settings: a cross-sectional study on adoption dynamics among educators. Interactive Learning Environments, 33(4), 2954-2977. [CrossRef]

- Salleh, A. B., Phon, D. N. E., Rahman, N. S. A., Hashim, S. B., & Lah, N. H. C. (2023, August 25-27). Examining the correlations between teacher profiling, ICT skills, and the readiness of integrating augmented reality in education. In 2023 IEEE 8th International Conference On Software Engineering and Computer Systems (ICSECS) (pp. 303-308). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Salmee, M. S. A., & Majid, A. F. (2022). A study on in-service English teachers’ perceptions towards the use of augmented reality (AR) in ESL classroom: Implications for TESL programme in higher education institutions. Asian Journal of University Education, 18(2), 499-509. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Obando, J. W., & Duque-Méndez, N. D. (2023). Augmented reality strategy as a didactic alternative in rural public schools in Colombia. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 31(3), 552-573. [CrossRef]

- Scharf, E. M., & Baldwin, L. P. (2007). Assessing multiple choice question (MCQ) tests – a mathematical perspective. Active Learning in Higher Education, 8(1), 31-47. [CrossRef]

- Schina, D., Kalemaki, I., Miron, M. I., Patsias, A., Vlachopoulos, D., Thorkelsdóttir, R. B., & Jónsdóttir, J. G. (2025). Promoting sustainable digital behaviors: Evaluation of the ecodigital curriculum in schools in Greece and Romania. In L. G. Chova, C. G. Martínez, & J. Lees (Eds.), INTED2025 Proceedings (pp. 5011-5019). IATED. [CrossRef]

- Schlomann, A., Memmer, N., & Wahl, H. W. (2022). Awareness of age-related change is associated with attitudes toward technology and technology skills among older adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 905043. [CrossRef]

- Schmidthaler, E., Anđic, B., Schmollmüller, M., Sabitzer, B., & Lavicza, Z. (2023). Mobile augmented reality in biological education: Perceptions of Austrian secondary school teachers. Journal on Efficiency and Responsibility in Education and Science, 16(2), 113-127. [CrossRef]

- Schoonenboom, J., & Johnson, R. B. (2017). How to construct a mixed methods research design. Kolner Zeitschrift fur Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 69(2), 107-131. https://DOI10.1007/s11577-017-0454-1.

- Sensorama. (2024, May 26). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sensorama.

- Sethuraman, R., Kerin, R. A., & Cron, W. L. (2005). A field study comparing online and offline data collection methods for identifying product attribute preferences using conjoint analysis. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 602-610. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S. S., & Wilk, M. B. (1965). An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika, 52(3/4), 591–611. [CrossRef]

- Shivani, & Chander, Y. (2023). Effect of online learning augmented reality programme on academic achievement in science. Indian Journal of Educational Technology, 5(2), 8-23.

- Singh, R. (2025, April 21). Types of AR experiences: Marker-based, markerless, and location-based. Twin Reality. https://twinreality.in/.

- Sirakaya, M., & Cakmak, E. K. (2018). Investigating student attitudes toward augmented reality. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology, 6(1), 30-44.

- Sırakaya, M., & Sırakaya, D. A. (2022). Augmented reality in STEM education: A systematic review. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(8), 1556-1569. [CrossRef]

- Sökmen, Y., Sarikaya, İ., & Nalçacı, A. (2024). The effect of augmented reality technology on primary school students’ achievement, attitudes towards the course, attitudes towards technology, and participation in classroom activities. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 40(15), 3936-3951. [CrossRef]

- Stojsic, I., Ostojic, N., & Stanisavljevic, J. (2022). Students’ acceptance of mobile augmented reality applications in primary and secondary biology education. International Journal of cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education, 10(3), 129-138. [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, H., Aziz, N. N., Ibrahim, E. N. M., & Isa, W. A. R. W. M. (2022). Technology acceptance in learning history subject using augmented reality towards smart mobile learning environment: Case in Malaysia. Journal of Automation, Mobile Robotics and Intelligent Systems, 16(2), 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Sulisworo, D., Drusmin, R., Kusumaningtyas, D. A., Handayani, T., Wahyuningsih, W., Jufriansah, A., ... & Prasetyo, E. (2021). The Science teachers’ optimism response to the use of marker-based augmented reality in the global warming issue. Education Research International, 2021(1), 7264230. [CrossRef]

- Syahputri, D. (2019). The effect of multisensory teaching method on the students’ reading achievement. Budapest International Research and Critics in Linguistics and Education, 2(1), 124-131. [CrossRef]

- Tanujaya, B., Prahmana, R. C. I., & Mumu, J. (2022). Likert scale in social sciences research: Problems and difficulties. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 16(4), 89-101. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N., & Sulaiman, Z. K. (2024). A study on the influence of social media on forming the social skills among adolescents. Tuijin Jishu/Journal of Propulsion Technology, 45(4), 554-570. [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, S., Sharmila, K., & Sufina, K. (2025). Revolutionizing education through augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR): Innovations, challenges and future prospects. Asian Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 8(1), 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Thanya, R. (2025). AR vs. VR in education: A comparative study of their impact on academic learning. Bodhi International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science, 9(2), 81-88.

- The sword of damocles (virtual reality). (2024, April 1). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sword_of_Damocles_(virtual_reality).

- Theodorio, A. O., Waghid, Z., & Wambua, A. (2024). Technology integration in teacher education: challenges and adaptations in the post-pandemic era. Discover Education, 3(1), 242. [CrossRef]

- Tiede, J., Grafe, S., & Mangina, E. (2022, May 30-June 4). Teachers’ attitudes and technology acceptance towards AR apps for teaching and learning. In 2022 8th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN), Vienna, Austria, (pp. 1-8). IEEE Xplore. [CrossRef]

- Tipton, E. (2013). Stratified sampling using cluster analysis: A sample selection strategy for improved generalizations from experiments. Evaluation Review, 37(2), 109-139. [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J., Van-de Velde, S., Vermeersch, H., & Van-Houtte, M. (2016). Gender differences in the ICT profile of University students: a quantitative analysis. Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies, 3(1), 57–77. [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, M. K., & Panda, B. N. (2021). Adaptability and awareness of augmented reality in teacher education. Educational Quest: An Int. J. of Education and Applied Social Sciences, 12(2), 107-114. [CrossRef]

- Turan, Z., Meral, E., & Sahin, I. F. (2018). The impact of mobile augmented reality in geography education: achievements, cognitive loads, and university students' views. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 42(3), 427-441. [CrossRef]

- Turhan, M. E., Metin, M., & Çevik, E. E. (2022). A content analysis of studies published in the field of augmented reality in education. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 5(1), 243–262. [CrossRef]

- Tzima, S., Styliaras, G., & Bassounas, A. (2019). Augmented reality applications in education: Teachers point of view. Education Sciences, 9(2), 99. [CrossRef]

- Uderbayeva, N., Karelkhan, N., Zharlykassov, B., Radchenko, T., & Imanova, A. (2025). Developing future teachers’ competences in IT and robotics using virtual and augmented reality: A study of teaching effectiveness. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 17(1), 119-132. [CrossRef]

- Uygur, M., Yelken, T. Y., & Akay, C. (2018). Analyzing the views of pre-service teachers on the use of augmented reality applications in education. European Journal of Educational Research, 7(4), 849-860. [CrossRef]

- Vaida, S., & Pongracz, G. A. (2022). Mobile augmented reality applications in higher education. Educatia, 21(23), 70-76. [CrossRef]

- Ventrella, F. M., & Cotnam-Kappel, M. (2024). Examining digital capital and digital inequalities in Canadian elementary schools: Insights from teachers. Telematics and Informatics, 86, 102070. [CrossRef]

- Wadkar, S. K., Singh, K., Chakravarty, R., & Argade, S. D. (2016). Assessing the reliability of attitude scale by Cronbach’s alpha. Journal of Global Communication, 9(2), 113-117. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Young, G. W., Iqbal, M. Z., & Guckin, C. M. (2024). The potential of extended reality in rural education’s future–perspectives from rural educators. Education and Information Technologies, 29(7), 8987-9011. [CrossRef]

- Weng, C., Otanga, S., Christianto, S., & Chu, R. (2020). Enhancing student’s biology learning by using augmented reality as a learning supplement. Journal of Educational Computing, 58(4), 747-770. [CrossRef]

- Wijnen, F., Molen, J. W. V. D., & Voogt, J. (2023). Primary school teachers’ attitudes toward technology use and stimulating higher-order thinking in students: A review of the literature. Journal of research on technology in education, 55(4), 545-567. [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, R., & Cellary, W. (2013). Evaluation of learners’ attitude toward learning in ARIES augmented reality environments. Computers & Education, 68, 570-585. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. K., Lee, S. W. Y., Chang, H. Y., & Liang, J. C. (2013). Current status, opportunities and challenges of augmented reality in education. Computers & Education, 62, 41-49. [CrossRef]

- Wyss, C., & Bäuerlein, K. (2024). Augmented reality in the classroom—mentor teachers’ attitudes and technology use. Virtual Worlds, 3(4), 572-585. [CrossRef]

- Wyss, C., Degonda, A., Buhrer, W., & Furrer, F. (2022). The impact of student characteristics for working with AR technologies in higher education-findings from an exploratory study with Microsoft HoloLens. MDPI, 13, 112. [CrossRef]

- Yaneva, V., Clauser, B. E., Morales, A., & Paniagua, M. (2022). Assessing the validity of test scores using response process data from an eye-tracking study: a new approach. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 27(5), 1401-1422. [CrossRef]

- Youm, S., Jung, N., & Go, S. (2024). GPS-induced disparity correction for accurate object placement in augmented reality. Applied Sciences, 14(7), 2849. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G., & Chen, M. (2022). Positioning preservice teachers’ reflections and I-positions in the context of teaching practicum: A dialogical-self theory approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117, 103734. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R., Wenling, L., & Xuemei, Z. (2025). Augmented reality and student motivation: A systematic review (2013-2024). Journal of Computers for Science and Mathematics Learning, 2(1), 38-52. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T., Hu, J., Spek, E. V., & Birk, M. (2024). Understanding the effect of fantasy in augmented reality game-based learning from a player journey perspective. In CHCHI '23: proceedings of the eleventh international symposium of Chinese CHI (pp. 55-60). Association for Computing Machinery, Inc. [CrossRef]

| Teachers’ Perception Level on ARA | Range of Scores | Frequencies | Gain Scores | Percentage of Gain Scores | Total Percentage of Gain Scores | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

| Very High | 81-100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| High | 61-80 | 28 | 125 | 1940 | 8525 | 2.66 | 11.68 | 14.34 |

| Moderate | 41-60 | 148 | 248 | 8055 | 13215 | 11.04 | 18.10 | 29.14 |

| Low | 21-40 | 54 | 116 | 1910 | 4100 | 2.62 | 5.62 | 8.24 |

| Very Low | < 20 | 7 | 4 | 125 | 60 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| Total | 730 | 12030 | 25900 | 16.49 | 35.48 | 51.97 | ||

| Variables | Teachers’ Perception Level on ARA | (f0) | (fe) | (f0 - fe)2 /fe | df | ꭕ2 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

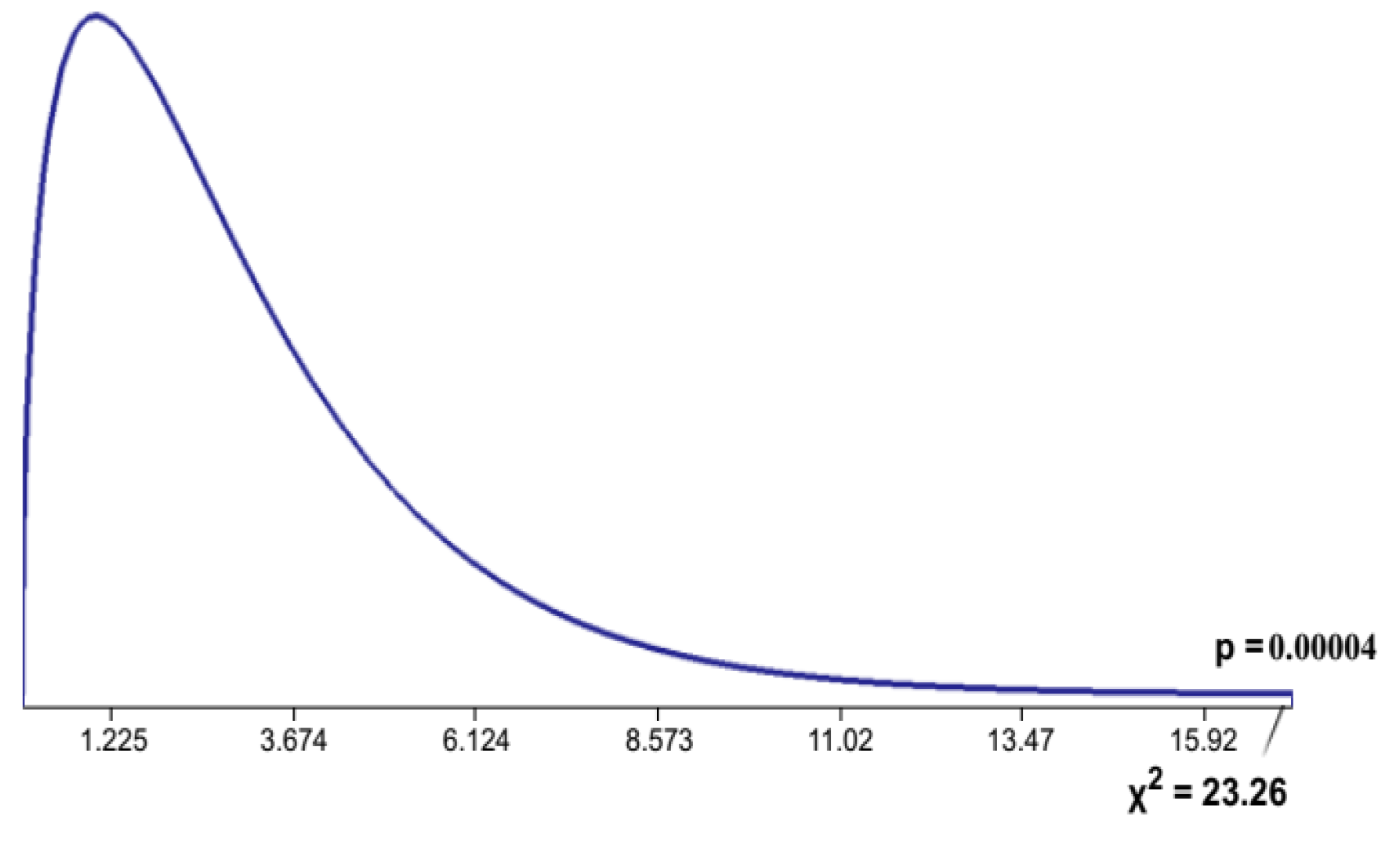

| Gender | Male | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 23.26 | 0.00004 p < .05 |

| High | 28 | 49.67 | 9.45 | |||||

| Moderate | 148 | 128.56 | 2.94 | |||||

| Low | 54 | 55.19 | 0.03 | |||||

| Very Low | 7 | 3.57 | 3.3 | |||||

| Female | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| High | 125 | 103.33 | 4.54 | |||||

| Moderate | 248 | 267.44 | 1.41 | |||||

| Low | 116 | 114.81 | 0.01 | |||||

| Very Low | 4 | 7.43 | 1.58 | |||||

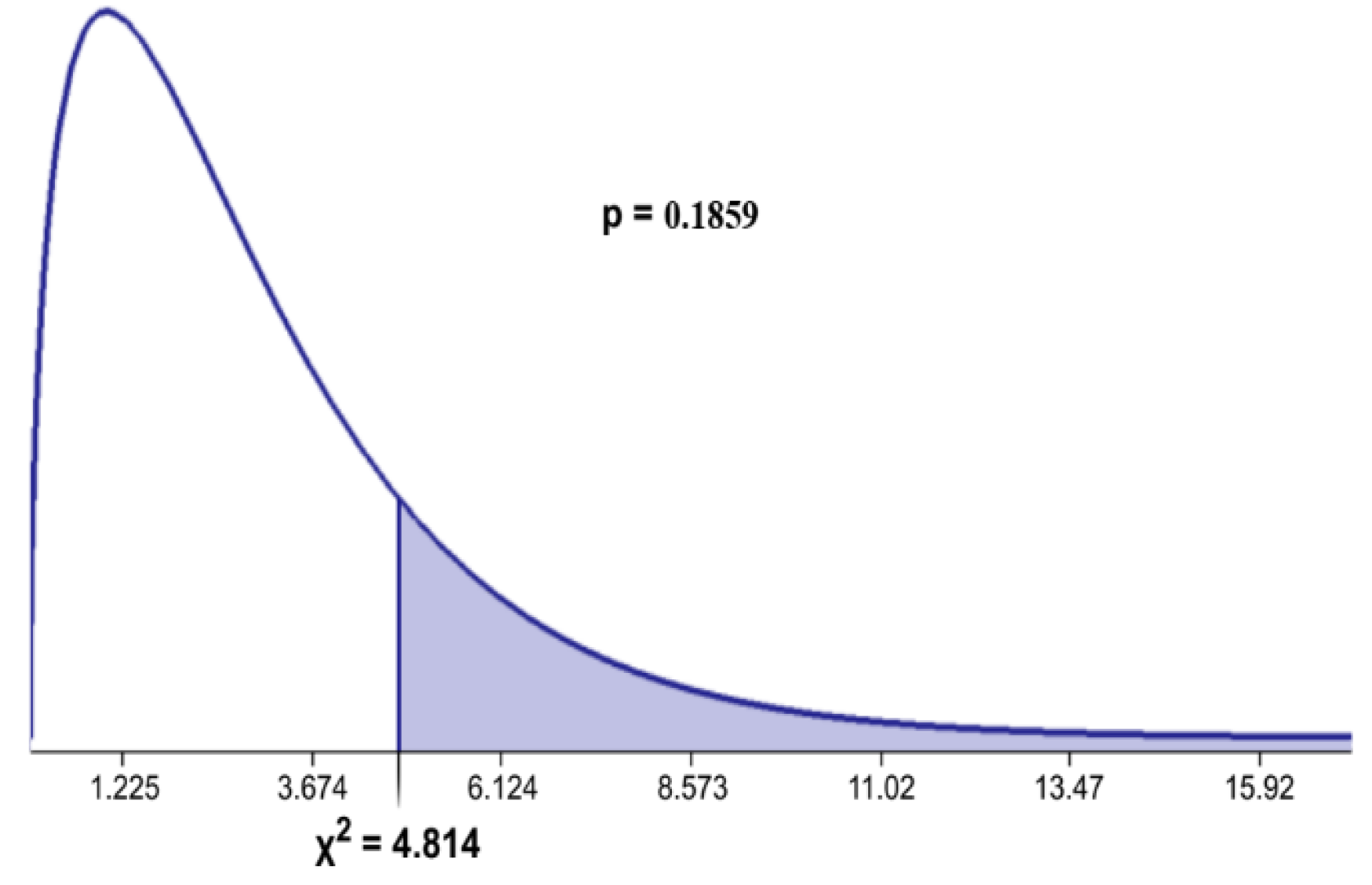

| Location of School | Rural | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4.814 | 0.1859 p > .05 |

| High | 33 | 41.71 | 1.82 | |||||

| Moderate | 114 | 107.95 | 0.34 | |||||

| Low | 47 | 46.34 | 0.01 | |||||

| Very Low | 5 | 3 | 1.33 | |||||

| Urban | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| High | 120 | 111.29 | 0.68 | |||||

| Moderate | 282 | 288.05 | 0.13 | |||||

| Low | 123 | 123.66 | 0.004 | |||||

| Very Low | 6 | 8 | 0.5 | |||||

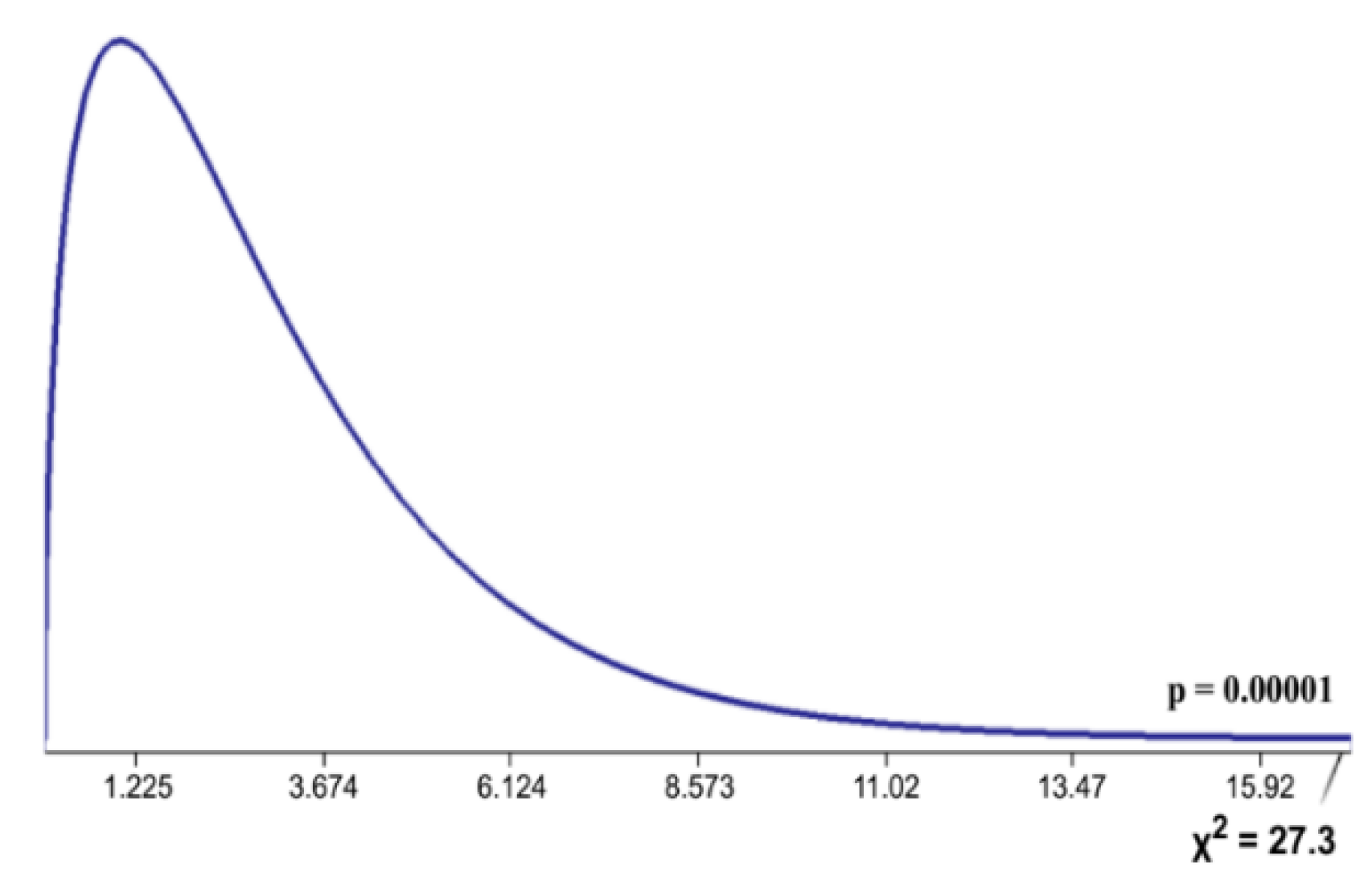

| Categories of School | Government | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 27.30 | 0.00001 p<.05 |

| High | 50 | 64.13 | 3.11 | |||||

| Moderate | 199 | 165.99 | 6.56 | |||||

| Low | 51 | 71.26 | 5.76 | |||||

| Very Low | 6 | 4.61 | 0.42 | |||||

| Private | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| High | 103 | 88.87 | 2.25 | |||||

| Moderate | 197 | 230.01 | 4.74 | |||||

| Low | 119 | 98.74 | 4.16 | |||||

| Very Low | 5 | 6.39 | 0.30 | |||||

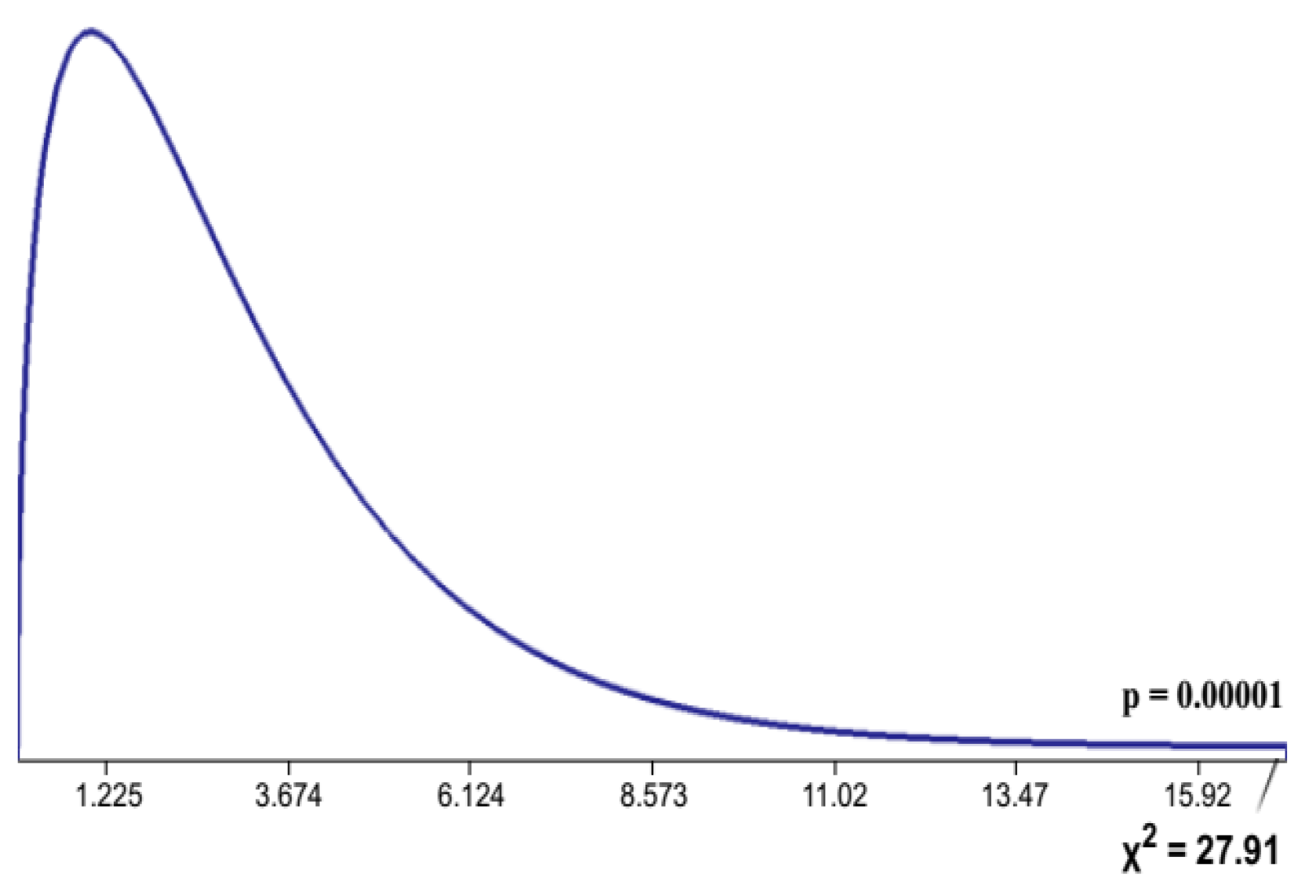

| Stream of Teachers | Science | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 27.91 | 0.00001 p<.05 |

| High | 77 | 65.39 | 2.06 | |||||

| Moderate | 143 | 169.25 | 4.07 | |||||

| Low | 92 | 72.66 | 5.15 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 4.7 | 4.7 | |||||

| Arts | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| High | 76 | 87.61 | 1.54 | |||||

| Moderate | 253 | 226.75 | 3.04 | |||||

| Low | 78 | 97.34 | 3.84 | |||||

| Very Low | 11 | 6.3 | 3.51 | |||||

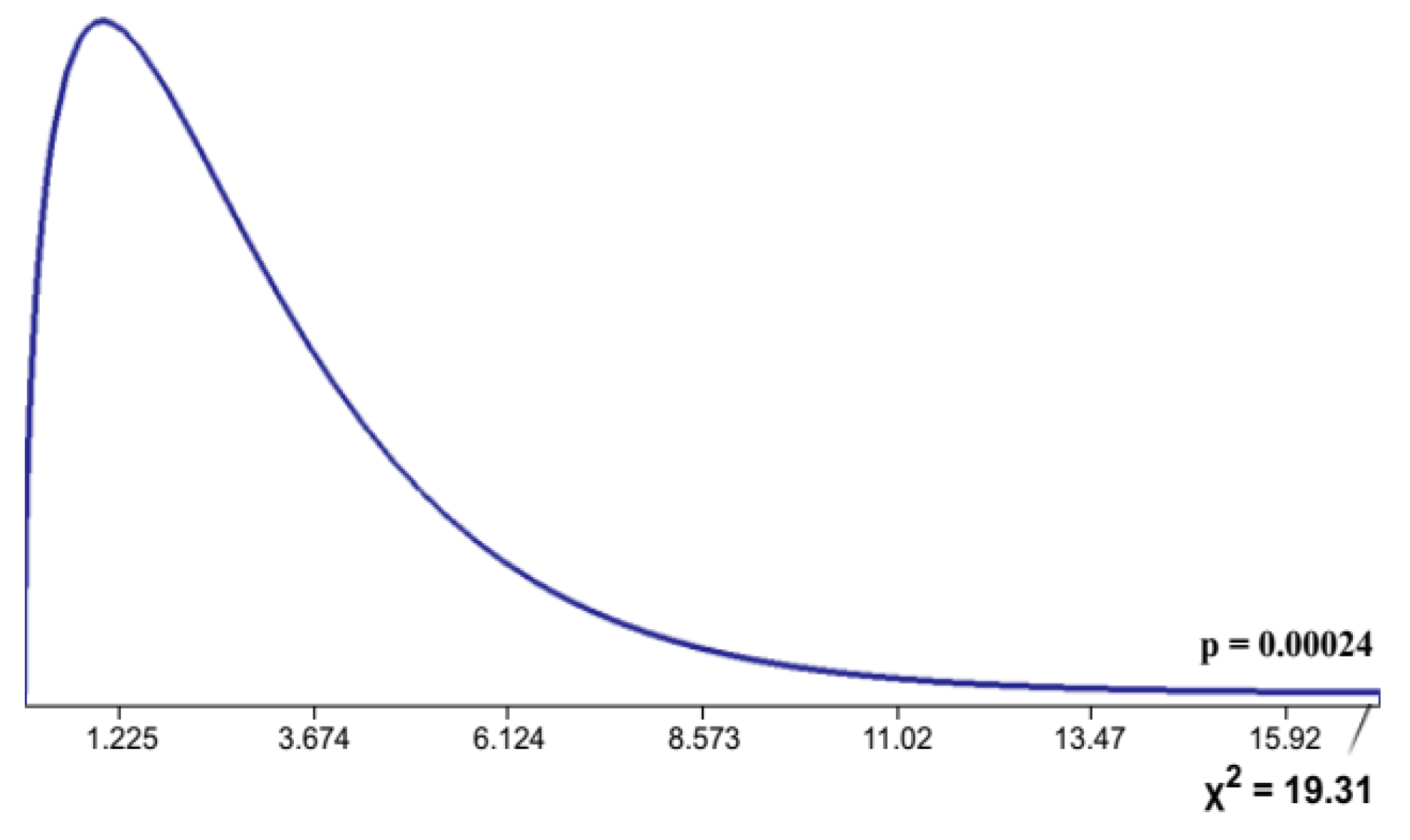

| Qualification | TGT | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 19.31 | 0.00024 p<.05 |

| High | 135 | 124.5 | 0.89 | |||||

| Moderate | 327 | 322.22 | 0.07 | |||||

| Low | 121 | 138.33 | 2.17 | |||||

| Very Low | 11 | 8.95 | 0.47 | |||||

| PGT | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| High | 18 | 28.5 | 3.87 | |||||

| Moderate | 69 | 73.78 | 0.31 | |||||

| Low | 49 | 31.67 | 9.48 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 2.05 | 2.05 | |||||

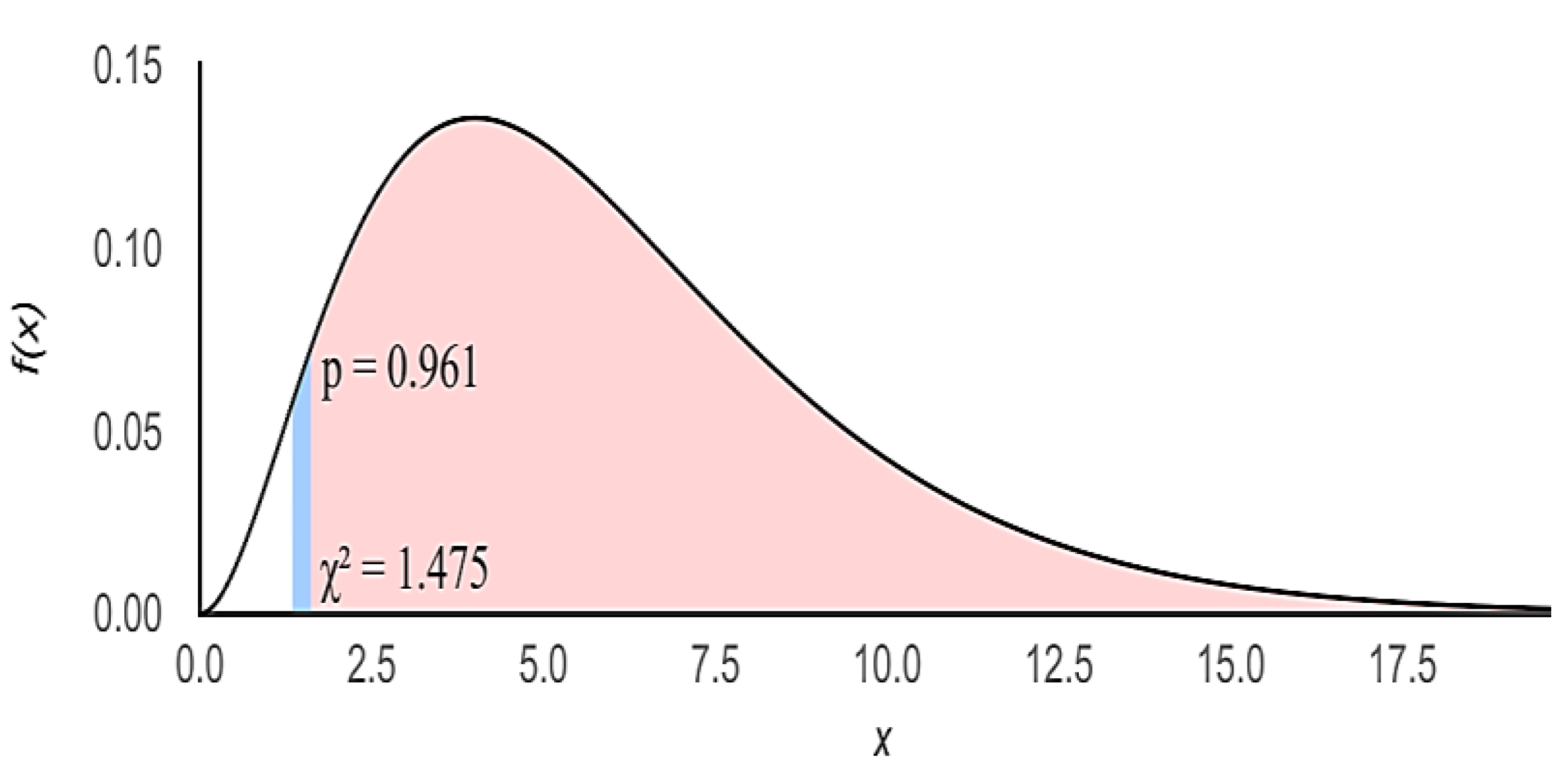

| Age | 20-33 | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1.4751 | 0.961 p>.05 |

| High | 102 | 104.17 | 0.045 | |||||

| Moderate | 272 | 269.61 | 0.02 | |||||

| Low | 115 | 115.74 | 0.005 | |||||

| Very Low | 8 | 7.49 | 0.03 | |||||

| 34-47 | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| High | 47 | 44.85 | 0.10 | |||||

| Moderate | 112 | 116.09 | 0.14 | |||||

| Low | 52 | 49.84 | 0.09 | |||||

| Very Low | 3 | 3.22 | 0.015 | |||||

| 48-60 & Above | Very High | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| High | 4 | 3.98 | 0.0001 | |||||

| Moderate | 12 | 10.31 | 0.28 | |||||

| Low | 3 | 4.42 | 0.46 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0.29 | 0.29 | |||||

| Overall | 3 | 416.553 | .00001 p < .05. |

|||||

| Variables | Mean | SEM | N | SD | SED | Df | t-value | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

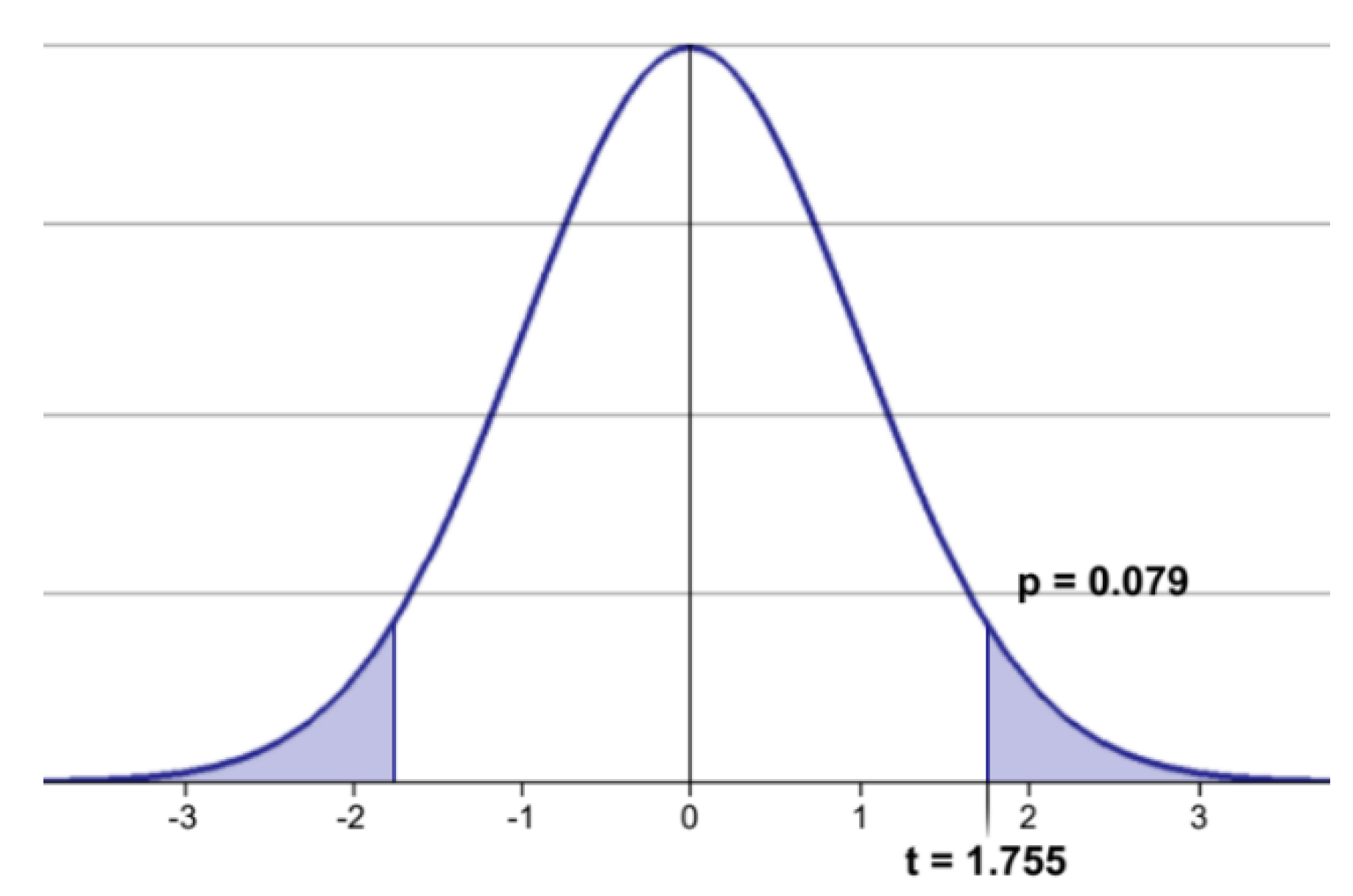

| Gender | Male | M1 | 50.76 | SEM1 | 0.82 | N1 | 237 | SD1 | 12.67 | 1.012 | 728 | 1.755 | 0.079 |

| Female | M2 | 52.54 | SEM2 | 0.58 | N2 | 493 | SD2 | 12.86 | |||||

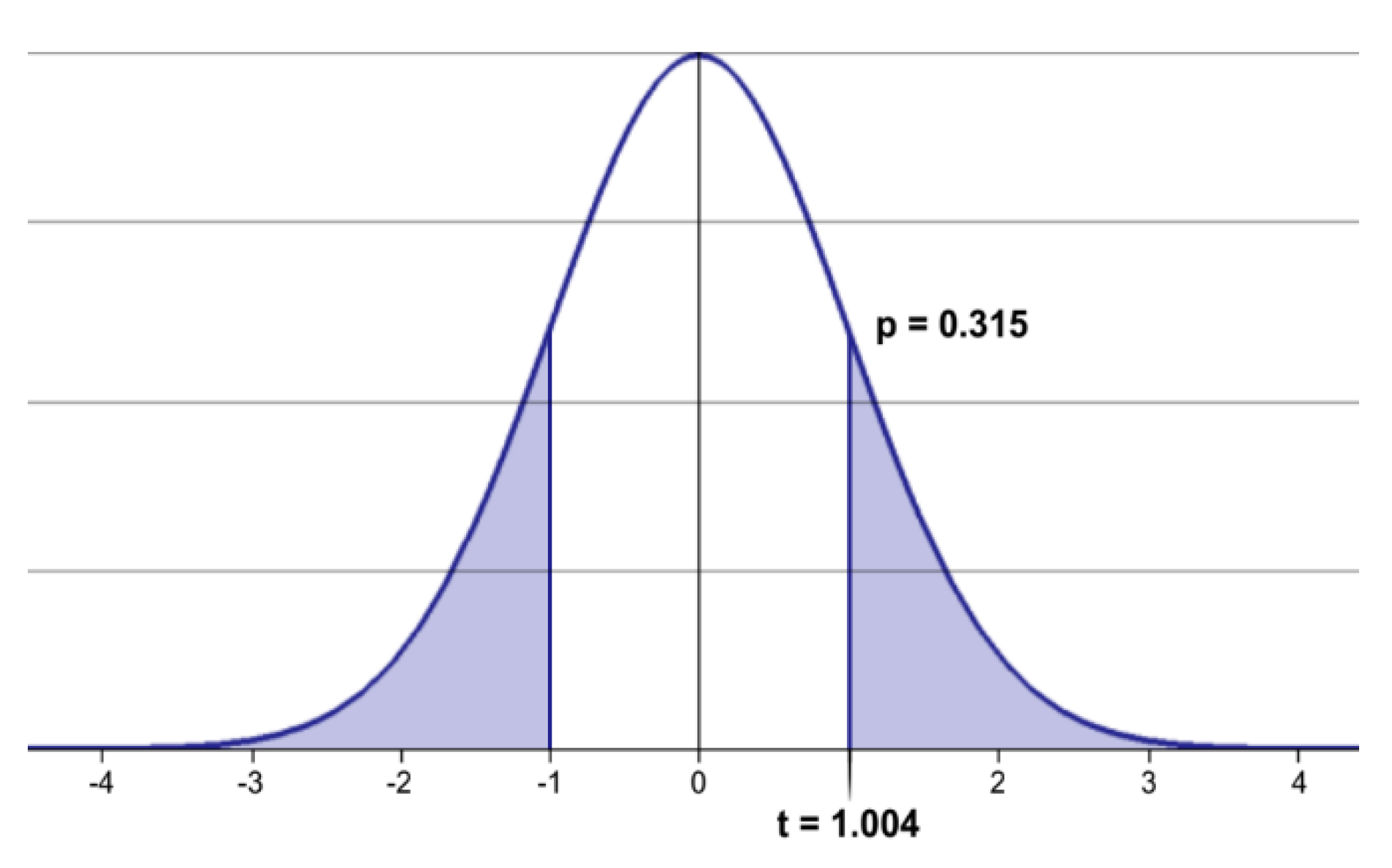

| Location | Rural | M1 | 51.18 | SEM1 | 0.89 | N1 | 199 | SD1 | 12.59 | 1.065 | 728 | 1.004 | 0.315 |

| Urban | M2 | 52.25 | SEM2 | 0.56 | N2 | 531 | SD2 | 12.90 | |||||

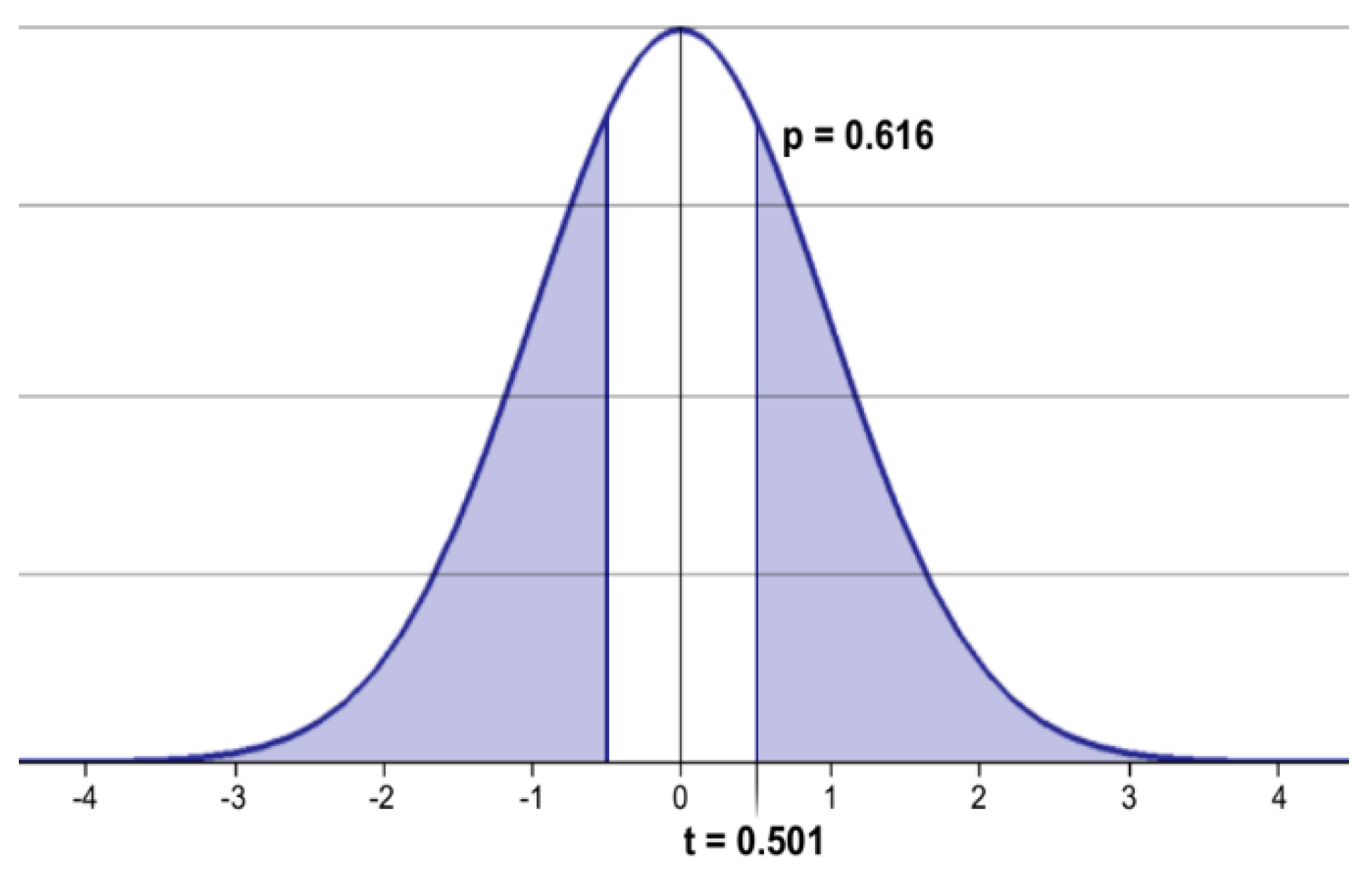

| Types of Organisations | Government | M1 | 52.24 | SEM1 | 0.70 | N1 | 306 | SD1 | 12.23 | 0.962 | 728 | 0.501 | 0.616 |

| Private | M2 | 51.76 | SEM2 | 0.64 | N2 | 424 | SD2 | 13.24 | |||||

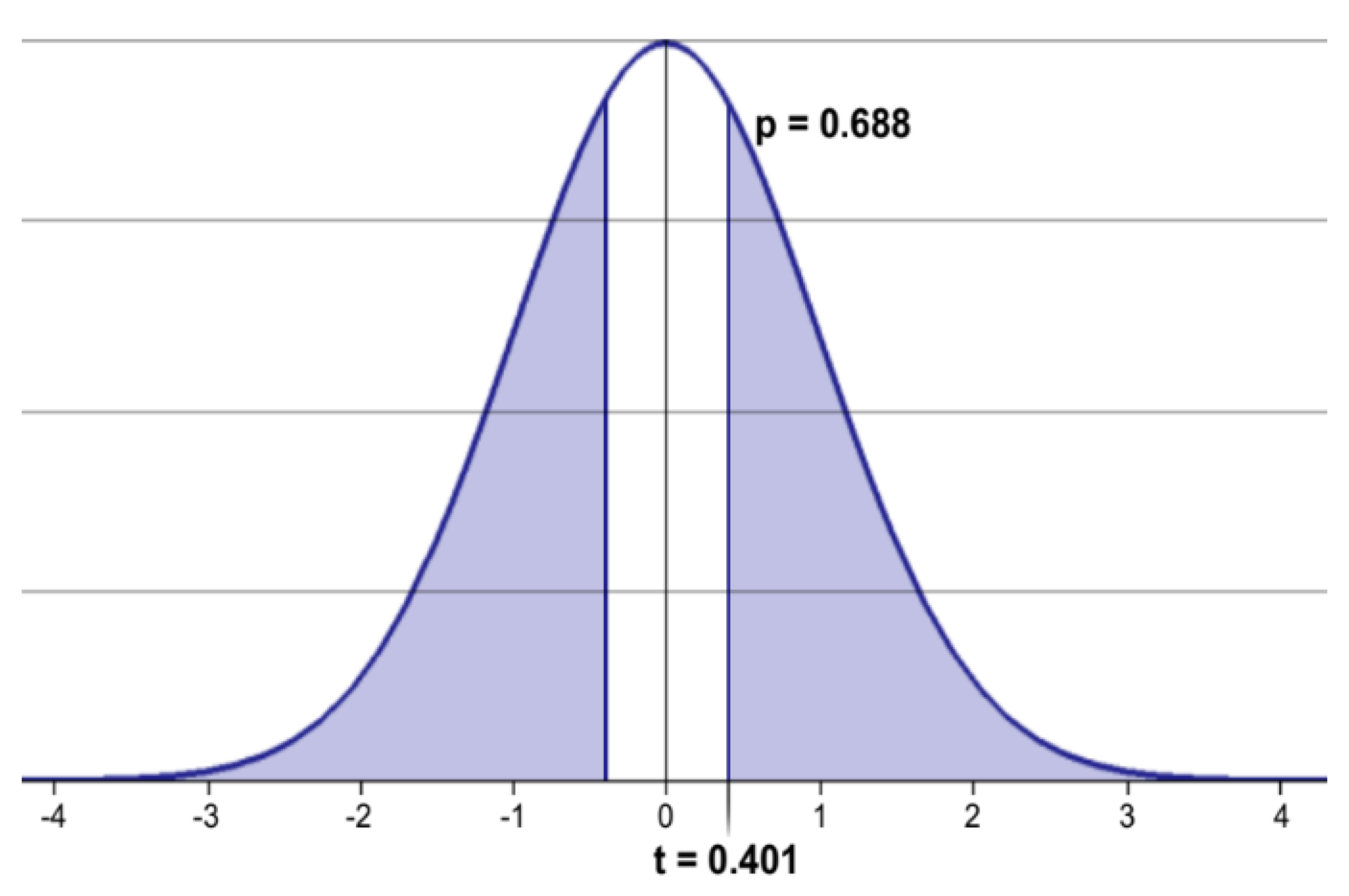

| Academic Streams | Science | M1 | 52.18 | SEM1 | 0.77 | N1 | 312 | SD1 | 13.61 | 0.960 | 728 | 0.401 | 0.688 |

| Arts | M2 | 51.79 | SEM2 | 0.60 | N2 | 418 | SD2 | 12.21 | |||||

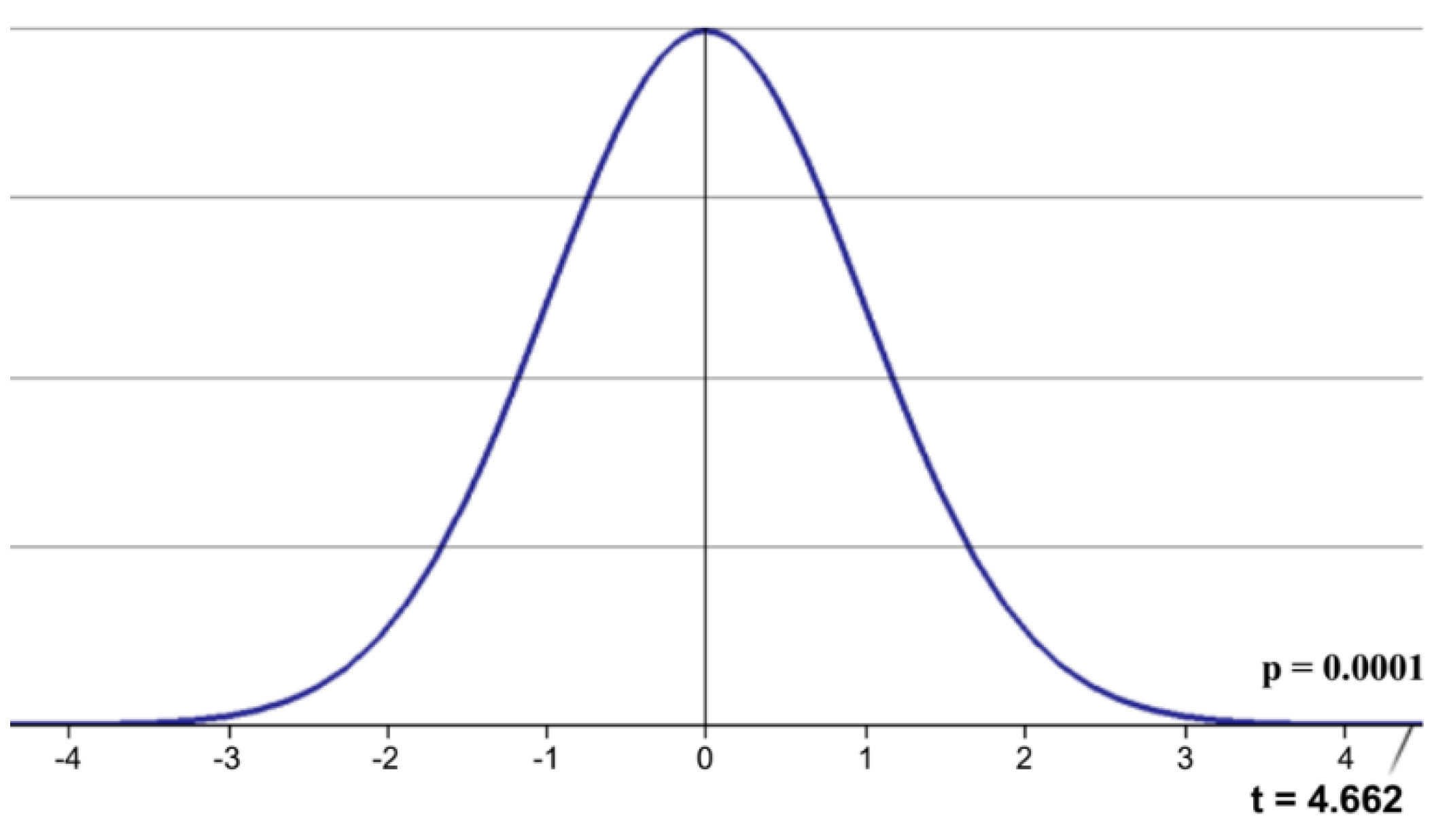

| Designation | TGT | M1 | 47.07 | SEM1 | 1.26 | N1 | 121 | SD1 | 13.84 | 1.258 | 728 | 4.662 | 0.0001 |

| PGT | M2 | 52.93 | SEM2 | 0.50 | N2 | 609 | SD2 | 12.39 | |||||

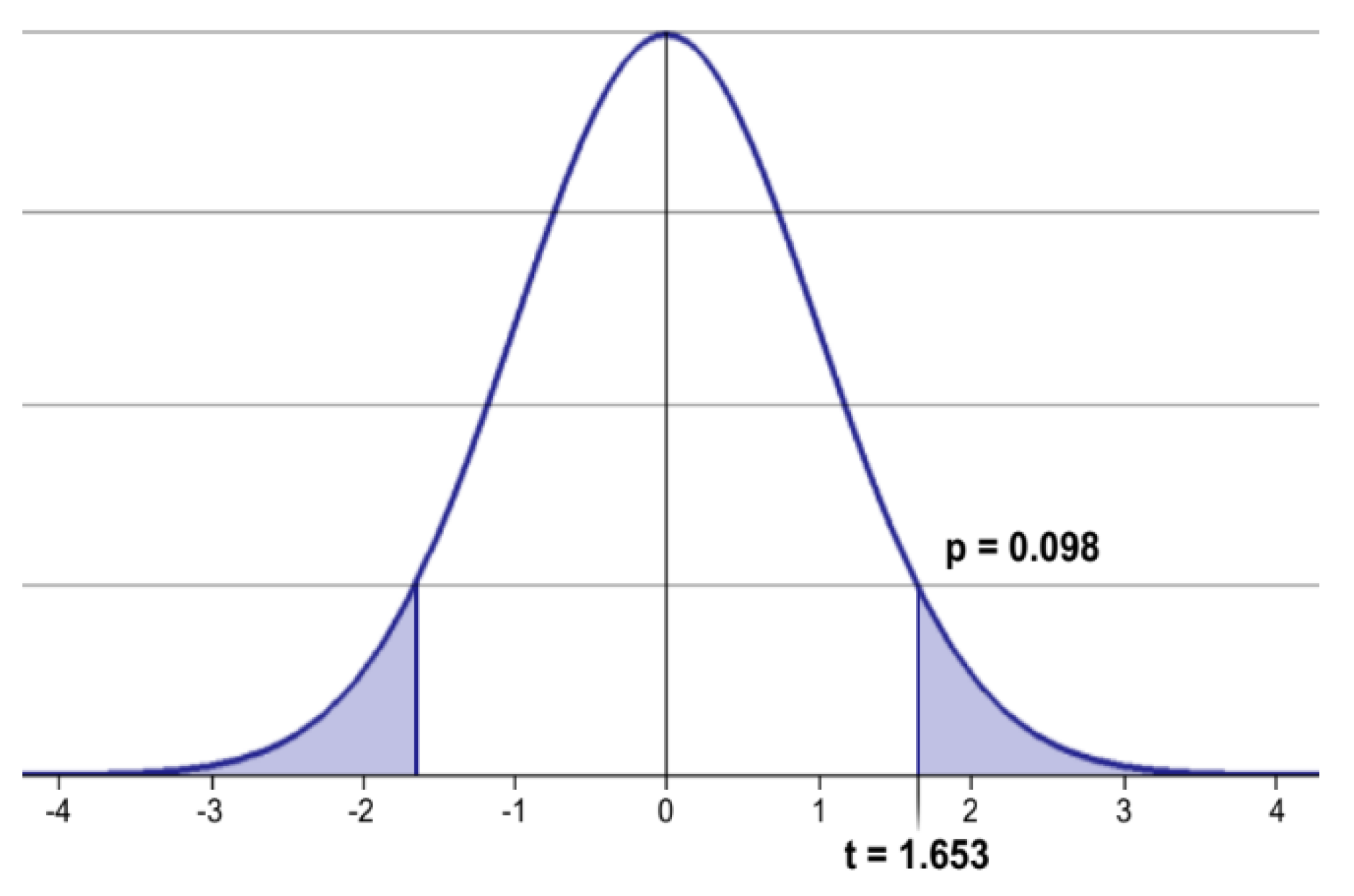

| Experience | High Experience (41-60 years & above) | M1 | 54.02 | SEM1 | 1.06 | N1 | 92 | SD1 | 10.14 | 1.428 | 728 | 1.653 | 0.098 |

| Low Experience (20-40 years) | M2 | 51.66 | SEM2 | 0.52 | N2 | 638 | SD2 | 13.14 | |||||

| Teachers’ Attitudes Level on ARA | Range of Scores | Frequencies |

Gain Scores |

Percentage of Gain Scores | Total Percentage of Gain Scores | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

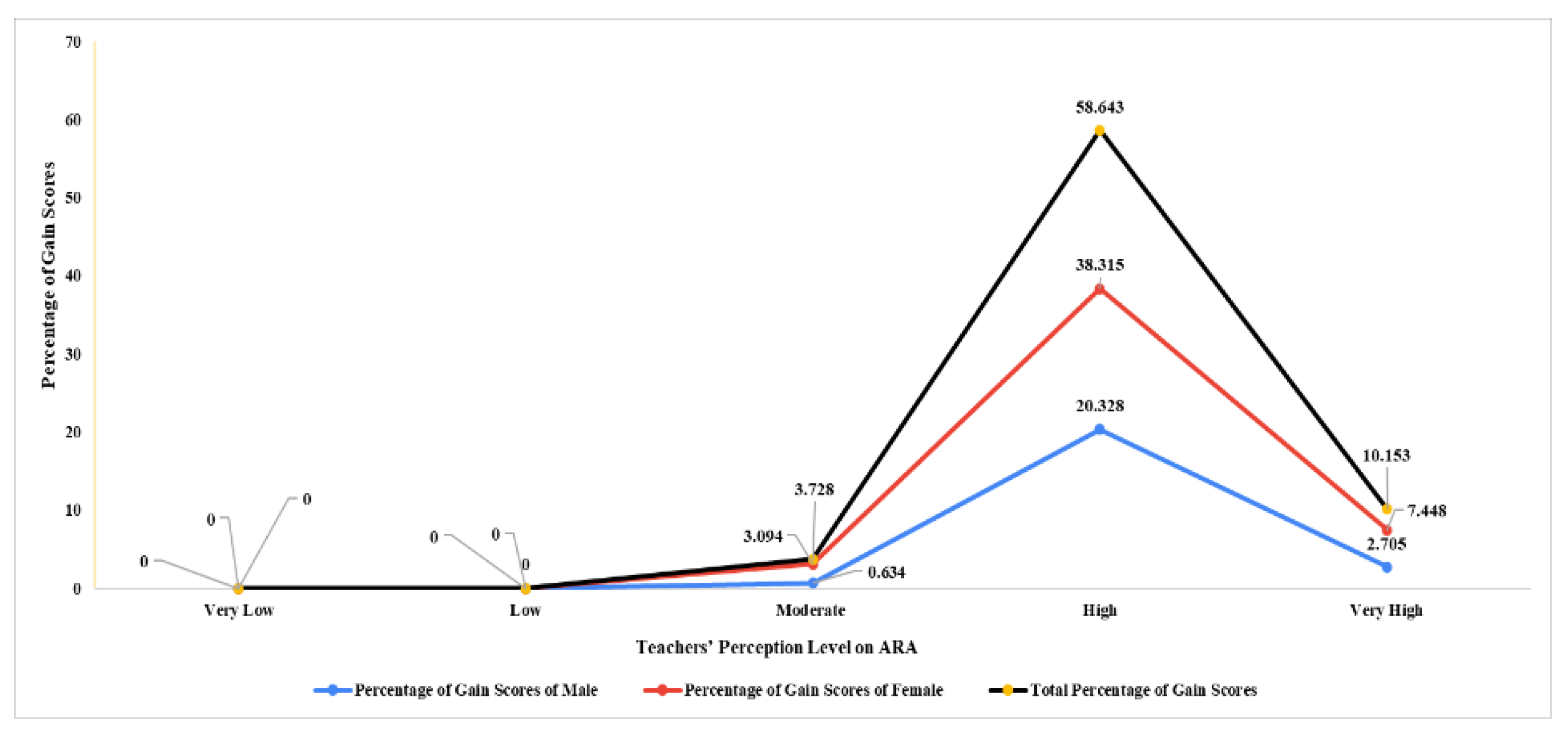

| Very High | 81-100 | 24 | 66 | 1975 | 5437 | 2.705 | 7.448 | 10.153 |

| High | 61-80 | 204 | 387 | 14840 | 27970 | 20.328 | 38.315 | 58.643 |

| Moderate | 41-60 | 9 | 40 | 463 | 2259 | 0.634 | 3.094 | 3.728 |

| Low | 21-40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Very Low | < 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 730 | 17278 | 35666 | 23.667 | 48.857 | 72.524 | ||

| Variables | Teachers’ Attitudes Level on ARA | (f0) | (fe) | (f0 - fe)2 /fe | df | ꭕ2 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

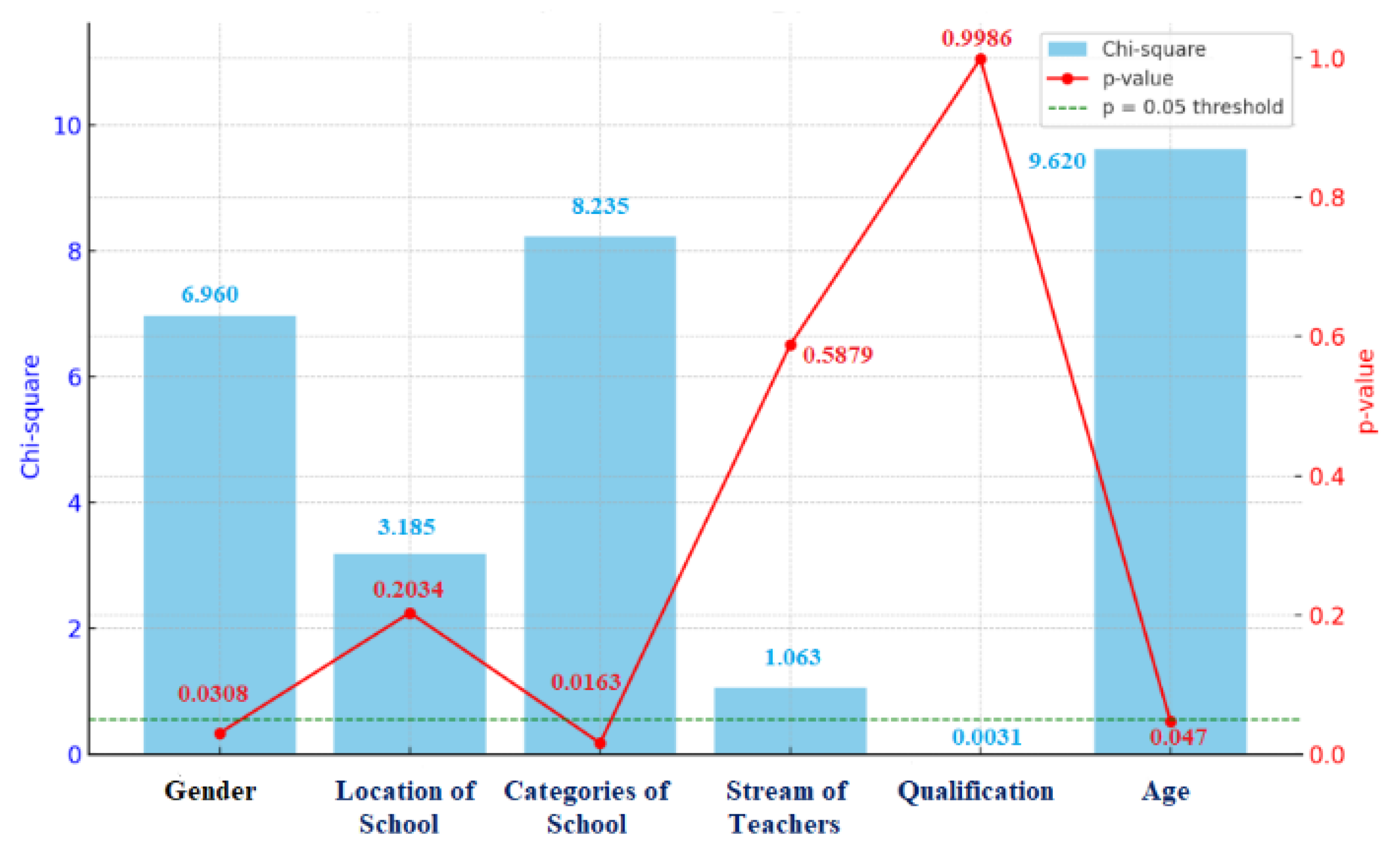

| Gender | Male | Very High | 24 | 29.22 | 0.932 | 2 |

6.960 |

0.0308 p < .05 |

| High | 204 | 191.87 | 0.767 | |||||

| Moderate | 9 | 15.91 | 3.001 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Female | Very High | 66 | 60.78 | 0.448 | ||||

| High | 387 | 399.13 | 0.369 | |||||

| Moderate | 40 | 33.09 | 1.443 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Location of School | Rural | Very High | 21 | 24.53 | 0.508 | 2 | 3.185 | 0.2034 p > .05 |

| High | 169 | 161.11 | 0.386 | |||||

| Moderate | 9 | 13.36 | 1.423 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Urban | Very High | 69 | 65.47 | 0.190 | ||||

| High | 422 | 429.89 | 0.145 | |||||

| Moderate | 40 | 35.64 | 0.533 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Categories of School | Government | Very High | 26 | 37.73 | 3.647 | 2 | 8.235 | 0.0163 p < .05 |

| High | 262 | 247.73 | 0.822 | |||||

| Moderate | 18 | 20.54 | 0.314 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Private | Very High | 64 | 52.27 | 2.632 | ||||

| High | 329 | 343.27 | 0.593 | |||||

| Moderate | 31 | 28.46 | 0.227 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Stream of Teachers | Science | Very High | 35 | 38.47 | 0.313 | 2 | 1.063 | 0.5879 p > .05 |

| High | 258 | 252.59 | 0.116 | |||||

| Moderate | 19 | 20.94 | 0.180 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Arts | Very High | 55 | 51.53 | 0.234 | ||||

| High | 333 | 338.41 | 0.086 | |||||

| Moderate | 30 | 28.06 | 0.134 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Qualification | TGT | Very High | 15 | 14.92 | 0.0004 | 2 | 0.0031 | 0.9986 p > .05 |

| High | 98 | 97.96 | 0.00002 | |||||

| Moderate | 8 | 8.12 | 0.0021 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| PGT | Very High | 75 | 75.08 | 0.0001 | ||||

| High | 493 | 493.04 | 0.000003 | |||||

| Moderate | 41 | 40.88 | 0.0005 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Age | 20-33 | Very High | 51 | 61.27 | 1.721 | 4 | 9.620 | 0.047 p < .05 |

| High | 413 | 402.37 | 0.290 | |||||

| Moderate | 33 | 33.36 | 0.010 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 34-47 | Very High | 35 | 26.38 | 2.817 | ||||

| High | 166 | 173.25 | 0.303 | |||||

| Moderate | 13 | 14.36 | 0.140 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 48-60 | Very High | 4 | 2.34 | 1.178 | ||||

| High | 12 | 15.38 | 0.850 | |||||

| Moderate | 3 | 1.28 | 2.311 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Overall | 2 | 748.558 | 0.00001 p < .05 |

|||||

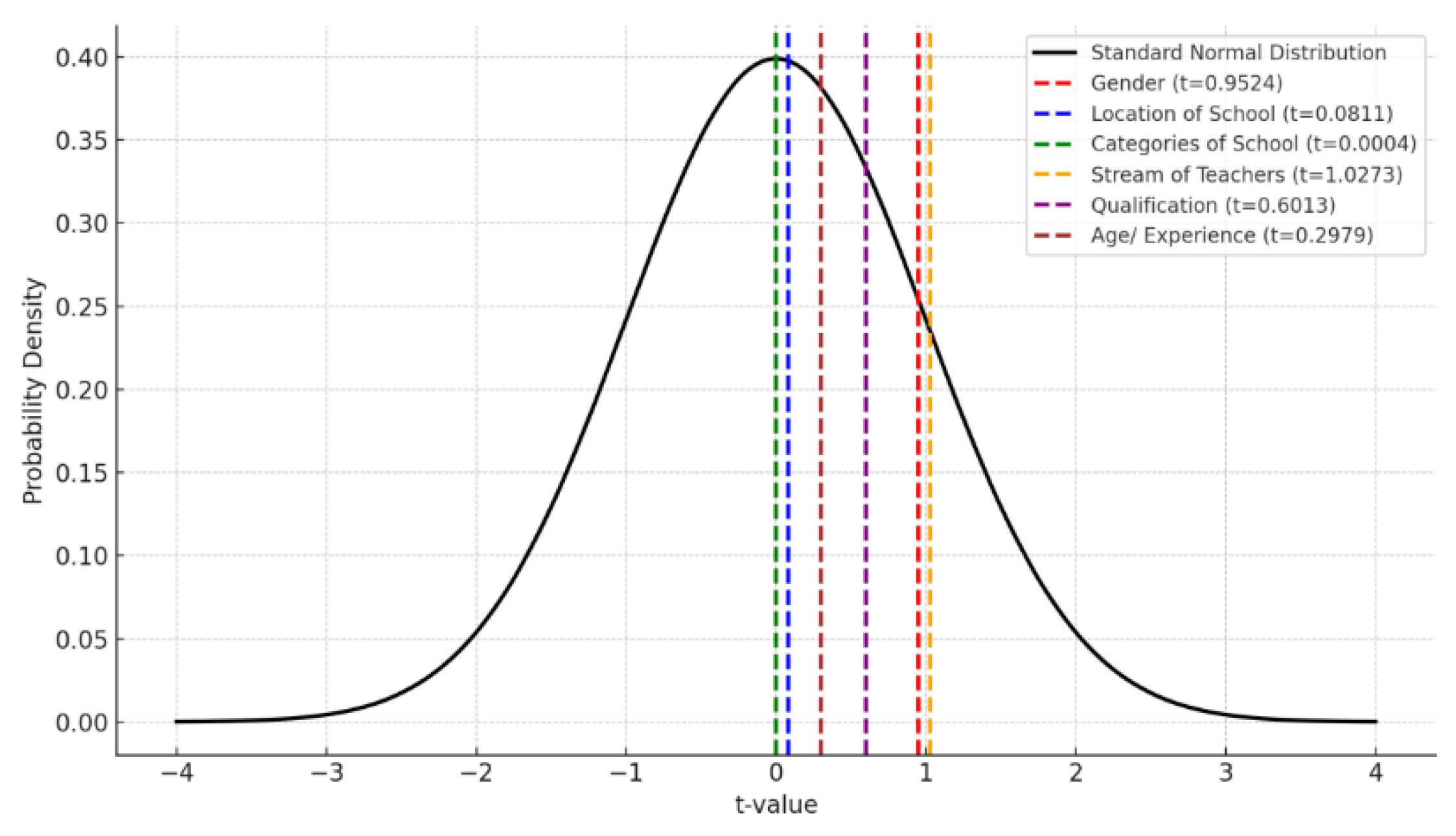

| Variables | Mean | SEM | N | SD | SED | df | t-value | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | M1 | 72.90 | SEM1 | 0.46 | N1 | 237 | SD1 | 7.01 | 0.586 | 728 | 0.9524 |

0.3412 p >0.05 |

| Female | M2 | 72.34 | SEM2 | 0.34 | N2 | 493 | SD2 | 7.60 | |||||

| Location | Urban | M1 | 72.54 | SEM1 | 0.33 | N1 | 531 | SD1 | 7.61 | 0.617 | 728 | 0.0811 | 0.9354 p >0.05 |

| Rural | M2 | 72.49 | SEM2 | 0.49 | N2 | 199 | SD2 | 6.87 | |||||

| Types of Organisations | Government | M1 | 72.526 | SEM1 | 0.40 | N1 | 306 | SD1 | 6.95 | 0.556 |

728 | 0.0004 | 0.9997 p >0.05 |

| Private | M2 | 72.5259 | SEM2 | 0.38 | N2 | 424 | SD2 | 7.74 | |||||

| Academic Streams | Science | M1 | 72.79 | SEM1 | 0.41 | N1 | 312 | SD1 | 7.19 | 0.555 | 728 | 1.0273 | 0.3046 p >0.05 |

| Arts | M2 | 72.22 | SEM2 | 0.37 | N2 | 418 | SD2 | 7.58 | |||||

| Designation | TGT | M1 | 72.17 | SEM1 | 0.71 | N1 | 131 | SD1 | 7.81 | 0.715 | 728 | 0.6013 | 0.5478 p >0.05 |

| PGT | M2 | 72.60 | SEM2 | 0.30 | N2 | 609 | SD2 | 7.34 | |||||

| Experience | High Experience (41-60 years) | M1 | 72.72 | SEM1 | 0.30 | N1 | 92 | SD1 | 7.54 | 0.738 | 728 | 0.2979 | 0.7659 p >0.05 |

| Low Experience (20-40 years) | M2 | 72.50 | SEM2 | 0.68 | N2 | 638 | SD2 | 6.48 | |||||

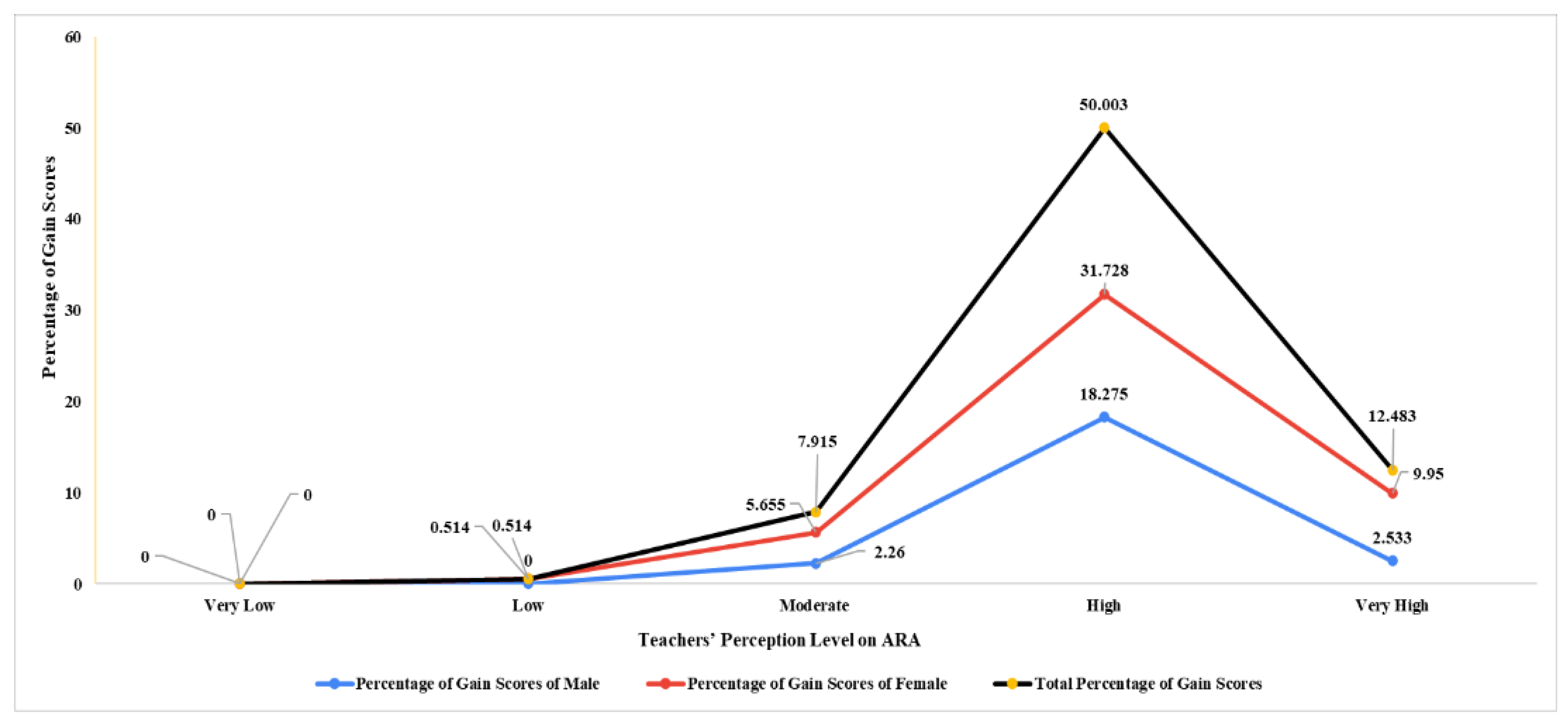

| Teachers’ Behaviour Level on ARA | Range of Scores | Frequencies |

Gain Scores |

Percentage of Gain Scores | Total Percentage of Gain Scores | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

| Very High | 81-100 | 22 | 86 | 1849 | 7265 | 2.533 | 9.950 | 12.483 |

| High | 61-80 | 183 | 322 | 13341 | 23162 | 18.275 | 31.728 | 50.003 |

| Moderate | 41-60 | 32 | 75 | 1651 | 4128 | 2.260 | 5.655 | 7.915 |

| Low | 21-40 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 375 | 0 | 0.514 | 0.514 |

| Very Low | < 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 730 | 16841 | 34930 | 23.068 | 47.847 | 70.915 | ||

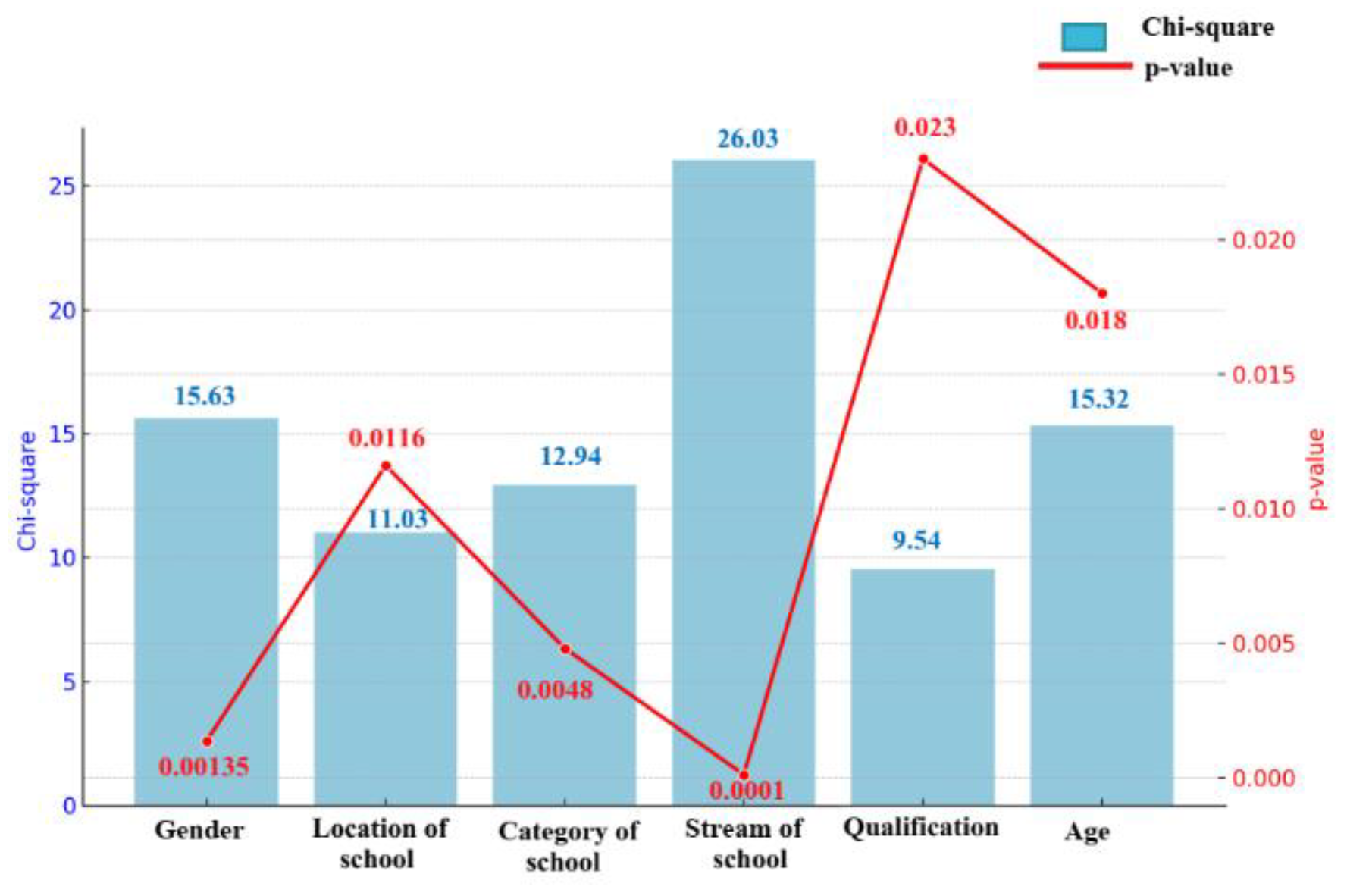

| Variables | Teachers’ Behavioural Level on ARA | (f0) | (fe) | (f0 - fe)2 /fe | df | ꭕ2 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gende | Male | Very High | 22 | 35.07 | 4.87 | 3 | 15.63 | 0.00135 p< .05 |

| High | 183 | 163.97 | 2.22 | |||||

| Moderate | 32 | 34.74 | 0.22 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 3.25 | 3.25 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Female | Very High | 86 | 72.93 | 2.34 | ||||

| High | 322 | 341.03 | 1.06 | |||||

| Moderate | 75 | 72.26 | 0.10 | |||||

| Low | 10 | 6.75 | 1.57 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Location of School | Rural | Very High | 36 | 29.44 | 1.46 | 3 | 11.03 | 0.0116 p<0.05 |

| High | 144 | 137.66 | 0.29 | |||||

| Moderate | 19 | 29.17 | 3.54 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 2.73 | 2.73 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Urban | Very High | 72 | 78.56 | 0.55 | ||||

| High | 361 | 367.34 | 0.11 | |||||

| Moderate | 88 | 77.83 | 1.33 | |||||

| Low | 10 | 7.27 | 1.02 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Categories of School | Government | Very High | 39 | 45.27 | 0.88 | 3 | 12.94 | 0.0048 p<0.05 |

| High | 229 | 211.68 | 1.41 | |||||

| Moderate | 38 | 44.85 | 1.05 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 4.19 | 4.19 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Private | Very High | 69 | 62.73 | 0.63 | ||||

| High | 276 | 293.32 | 1.02 | |||||

| Moderate | 69 | 62.15 | 0.75 | |||||

| Low | 10 | 5.81 | 3.01 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Stream of Teachers | Science | Very High | 62 | 46.14 | 5.47 | 3 | 26.03 | 0.0001 p<0.05 |

| High | 198 | 215.67 | 1.44 | |||||

| Moderate | 42 | 45.73 | 0.30 | |||||

| Low | 10 | 4.27 | 7.71 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Arts | Very High | 46 | 61.86 | 4.08 | ||||

| High | 307 | 289.33 | 1.07 | |||||

| Moderate | 65 | 61.27 | 0.23 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 5.73 | 5.73 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Qualification | TGT | Very High | 20 | 17.90 | 0.25 | 3 | 9.54 | 0.023 p < .05 |

| High | 76 | 83.66 | 0.71 | |||||

| Moderate | 20 | 17.73 | 0.29 | |||||

| Low | 5 | 1.66 | 6.70 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| PGT | Very High | 88 | 90.10 | 0.05 | ||||

| High | 429 | 421.34 | 0.14 | |||||

| Moderate | 87 | 89.27 | 0.06 | |||||

| Low | 5 | 8.34 | 1.34 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

|

Age |

20-33 | Very High | 81 | 73.47 | 0.77 | 6 | 15.32 | 0.018 p<0.05 |

| High | 339 | 343.44 | 0.057 | |||||

| Moderate | 67 | 72.77 | 0.458 | |||||

| Low | 10 | 6.80 | 1.507 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 34-47 | Very High | 26 | 31.64 | 1.005 | ||||

| High | 155 | 148.04 | 0.327 | |||||

| Moderate | 33 | 31.33 | 0.088 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 2.93 | 2.93 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 48-60 & Above | Very High | 1 | 2.81 | 1.164 | ||||

| High | 11 | 13.16 | 0.354 | |||||

| Moderate | 7 | 2.78 | 6.35 | |||||

| Low | 0 | 0.26 | 0.26 | |||||

| Very Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Overall | 3 | 800.47 |

0.00001 p<0.05 |

|||||

| Variables | Mean | SEM | N | SD | SED | df | t-value | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | M1 | 71.06 | SEM1 | 0.63 | N1 | 237 | SD1 | 9.77 | 0.828 | 728 | 0.2503 | 0.8024 |

| Female | M2 | 70.85 | SEM2 | 0.49 | N2 | 493 | SD2 | 10.79 | |||||

| Location | Urban | M1 | 70.33 | SEM1 | 0.47 | N1 | 531 | SD1 | 10.93 | 0.867 | 728 | 2.4879 | 0.0131 |

| Rural | M2 | 72.49 | SEM2 | 0.63 | N2 | 199 | SD2 | 8.93 | |||||

| Types of Organisations | Government | M1 | 71.27 | SEM1 | 0.56 | N1 | 306 | SD1 | 9.88 | 0.785 | 728 | 0.7721 | 0.4403 |

| Private | M2 | 70.67 | SEM2 | 0.53 | N2 | 424 | SD2 | 10.87 | |||||

| Academic Streams | Science | M1 | 70.90 | SEM1 | 0.64 | N1 | 312 | SD1 | 11.22 | 0.783 | 728 | 0.0413 | 0.9670 |

| Arts | M2 | 70.93 | SEM2 | 0.48 | N2 | 418 | SD2 | 9.87 | |||||

| Designation | TGT | M1 | 70.63 | SEM1 | 1.01 | N1 | 121 | SD1 | 11.13 | 1.042 | 728 | 0.3348 | 0.7378 |

| PGT | M2 | 70.98 | SEM2 | 0.42 | N2 | 609 | SD2 | 10.33 | |||||

| Experience | High Experience (41-60 years) | M1 | 68.95 | SEM1 | 1.03 | N1 | 92 | SD1 | 9.89 | 1.165 | 728 | 1.9389 | 0.0529 |

| Low Experience (20-40 years) | M2 | 71.20 | SEM2 | 0.42 | N2 | 638 | SD2 | 10.52 | |||||

| Multiple Correlations Coefficient | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain of Teachers | Perception of Teachers on ARA | Attitudes of Teachers on ARA | Behaviour of Teachers on ARA | |

| Perception of Teachers on ARA | Correlation r | 1.00 | 0.34 | 0.21 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | - | p <.001 | p<.001 | |

| N | 730 | 730 | 730 | |

| Attitudes of Teachers on ARA | Correlation r | 0.34 | 1.00 | 0.63 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | p<.001 | - | p<.001 | |

| N | 730 | 730 | 730 | |

| Behaviour of Teachers on ARA | Correlation r | 0.21 | 0.63 | 1.00 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | p<.001 | p<.001 | - | |

| N | 730 | 730 | 730 | |

| Coefficient of Multiple Correlation (R) = 0.39 | ||||

| Variables | Mean | SEM1 | N | SD | SED | df | t-value | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception | M1 | 51.96 | SEM1 | 0.47 | 730 | SD1 | 12.82 | 0.461 | 729 | 44.6612 | <0.0001 |

| Attitudes | M2 | 72.53 | SEM1 | 0.27 | SD2 | 7.41 | |||||

| Perception | M1 | 51.96 | SEM1 | 0.47 | 730 | SD1 | 12.82 | 0.547 | 729 | 34.6312 | <0.0001 |

| Behaviour | M2 | 70.92 | SEM1 | 0.39 | SD2 | 10.46 | |||||

| Attitudes | M1 | 72.53 | SEM1 | 0.27 | 730 | SD1 | 7.41 | 0.304 | 729 | 5.2867 | <0.0001 |

| Behaviour | M2 | 70.92 | SEM1 | 0.39 | SD2 | 10.46 | |||||

| Domain | Source of Variation | SS | df | MS | F value | p value |

| Teachers’ perception, attitudes and behaviour on ARA | Between Groups | 191036.2556 | 2 | 95518.1278 | 871.5964 | < 0.001 |

| Within Groups | 239673.0137 | 2187 | 109.59 | |||

| Corrected Total | 430709.2693 | 2189 | 196.76 |

| Theme | Summary | Sample data as examples |

|---|---|---|

| Thematic analysis of the participant’s based on the given questions | ||

| RQ1. What are the strategies that you think suitable for using Augmented Reality applications in the classroom situation? | ||

| Basic factors and suitable strategies for using Augmented Reality applications in the classroom. | Limited knowledge, lack of interest, and low motivation influence Indian school teachers' perceptions, attitudes and behaviours of augmented reality applications in educational settings. |

R19, R33: ‘I have seen AR being used in various videos several times, but I still don’t fully understand how it is applied in practice……since I teach in a rural school, neither the administration nor my fellow teachers show much interest in exploring new ideas or technologies.’ R1, R11, R70: ‘…. strategies for using AR in normal classroom is difficult… …..according to me teachers can use their own mobile if they are familiar to use AR in the class room situation… ...it totally depends upon the will power and interest of the teachers….’ R20, R81, R88, R57: ‘….in my school, most teachers are not interested in exploring new knowledge…...since I have some basic understanding of using AR…….I use my own smartphone and divide the class into small groups, allowing each group 5 minutes with the AR activity…….group-based approach by using a single device, I am able to make my classes more engaging and interactive with AR.’ R79, R31: ‘Although using AR in our school is challenging, I make an effort to incorporate it whenever possible……due to poor internet connectivity, I download AR models for my subject in advance, allowing me to teach without relying on an internet connection.’ |

| Passionate teachers can apply various approaches in the classroom, such as Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) or Use Your Own Gadgets (UYOG), group activities using a single device, and pre-downloading AR content. | R5, R61: ‘If a teacher is personally interested in using AR, they can effectively use their own mobile device…..any compatible gadget to benefit the students.’ R2, R10: ‘……if teachers are aware about the AR then they can simply use BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) approach for their learners……it’s all about how passionate you are in the teaching profession…’ R12: ‘Instead of having traditional way of teaching teachers can easily use their own smartphone i.e. UYOG (Use Your Own Gadgets) for applying AR in their class room situation.’ R4, R87: ‘…there are many free Apps for AR for all types of subjects…….if teachers are aware they can without difficulty use it by their smartphone in the class….’ |

|