1. Introduction

The railway enables the circulation of railway vehicles in a safe and comfortable manner. Prioritizing rail transport over road transport represents an effective approach to combating climate change and reducing the carbon footprint. In line with this, it is necessary to increase the capacity of the railway network by raising circulation velocity without compromising passenger safety and comfort. To achieve this, an adequate transfer of solicitations to the ground must be ensured. Given the high demands that rolling stock imposes on the rail, one of the most challenging problems is identifying the most suitable technical solutions capable of supporting an increase in traffic velocity under standardized conditions without compromising passenger comfort or vehicle ride quality.

The maximum attainable circulation velocity in railway systems is often constrained by the so-called critical velocity, which, in the context of a moving force, represents the lowest velocity at which waves can propagate through the supporting track structure. This velocity arises from the dynamic interplay between all structural components and corresponds to a resonance condition. Experimental data indicate that this threshold has already been reached under real operating conditions [

1].

To deepen our understanding of such dynamic behavior, further investigations are conducted within the well-established framework of moving load problems—a subject that continues to attract significant interest in transportation engineering. To enhance computational tractability and facilitate optimization and sensitivity analyses, many studies adopt simplified models. These simplifications can pertain to either the structure, the vehicle, or both, depending on the specific aspect under study. Besides exploring the effect of key parameters on dynamic response, major areas of interest include resonance-related critical velocities and frequencies, system instability, and the interaction between moving neighboring inertial bodies.

Common structural simplifications have led to layered models comprising beams, concentrated masses, and spring-damper elements. These configurations are favored for their simplicity and computational efficiency, finding widespread application in both research and practice. A survey of foundation modeling approaches is available in the classical work [

2], while the discrete–continuous modeling debate is discussed in [

3]. Rail tracks are frequently represented as Euler–Bernoulli infinite beams supported by continuous elastic foundations with one [

4,

5,

6,

7], two [

8,

9], or three layers [

10,

11]. Alternatively, the Euler–Bernoulli formulation may be replaced with a Timoshenko beam model to account for shear deformation and rotary inertia [

12,

13,

14]. To accurately reflect the influence of sleeper spacing, models incorporating discrete supports are also used [

15]. Despite their simplicity, such idealized models have successfully captured various phenomena in railway dynamics, as demonstrated in [

16]. Comprehensive studies on vehicle–track interactions can be found in [

17,

18,

19], further affirming the practical value of simplified modeling approaches. A taxonomy of layered models is proposed in [

20], while their experimental validation is discussed in [

21]. Naturally, the inclusion of additional layers improves the model’s ability to capture real-world behavior.

The feasibility of three-layer models in railway applications is evaluated in [

10], and comparative features of one-, two-, and three-layer systems are reviewed in [

22]. Research aimed at determining model parameters often builds upon the ballast pyramid concept [

23,

24] and the Saller hypothesis from 1932 [

25]. A detailed treatment of the pyramid model—referred to as the "stress cone model"—is presented in [

26], where it is used to derive vertical ballast stiffness and identify dynamically activated ballast mass. Refinements include overlapping cones between adjacent sleepers in both longitudinal [

27] and lateral directions [

10].

A number of studies concerning constant forces acting on an infinite structure exploit semianalytical methods. Fully analytical formulations are derived in [

28,

29]. The objectives of these two works are very similar, with some differences in the characterization of the Winkler–Pasternak foundation and critical damping. Both papers are also focused on critical velocity.

Advanced methods such as wavelet transforms are used in [

30] to investigate moving forces on a double-beam system. The Adomian decomposition method is applied to handle nonlinearity in the viscoelastic connection between beams, with the model later adapted into a two-layer version [

31] and extended to include nonlinear foundation behavior [

32,

33]. These studies directly derive steady-state solutions and compare their results with experimental observations.

Other works address the limitations of classical beam theories [

34,

35,

36]. Large deformations are handled in [

37]; initial conditions are accounted for in [

38]; non-uniform motion is analyzed in [

39]. Related problems include changes in foundation stiffness [

40,

41] or analyses concerned with non-classical ballasted tracks [

42].

Further studies related to this paper focus on sleeper spacing [

43,

44] or critical zones [

45], where more accurate mechanical descriptions of the track components are necessary, thus requiring numerical methods. When dealing with foundation models, more general formulations should be applied [

46].

Recent studies focus on the instability of moving inertial objects. In the book chapter [

47], vibrational stability of mechanical oscillators on continuous beam–foundation systems is analyzed using the D-decomposition method, comparing two models: one with a stabilizer directly connected to the car body, and another with interconnected primary suspensions. Instability of a moving bogie, with the possibility of occurring in the subcritical velocity range, is addressed in [

48]. Further subjects related to instability are discussed in the book chapters [

49,

50]. In [

51], the importance of material characterization is demonstrated through laboratory (physical and mechanical) tests and finite element modeling using four different rock materials as ballast, aiming to reduce the use of stone materials and promote an optimized, sustainable concept for new railway projects. The effects of ballast thickness on subgrade stresses are analyzed in terms of subgrade bearing capacity and permanent deformation of geotechnical materials.

In [

52], localized waves in an Euler–Bernoulli beam on a nonlinear elastic foundation with nonlinear structural damping under the action of a moving force are studied. New approximation formulas describing both linear and nonlinear damping characteristics are derived. The Ritz method and perturbation techniques are employed for this purpose. It is demonstrated that the nonlinear contribution reduces displacement amplitudes compared to the linear foundation; however, it also lowers the critical velocity. Additionally, there is never true resonance—displacements remain finite even in the absence of damping.

Machine learning and numerical approaches are compared in [

53] with the aim of evaluating track performance. In [

54], a novel perspective is presented for improving performance and reliability through material optimization based on wheel–rail interactions under variable load and track conditions in a Y25 bogie. As this involves more detailed numerical studies, finite element analysis is implemented.

In this paper, the geometry and material parameters of a three-layer railway track model are tailored to achieve favorable properties for the circulation of high-speed trains at very high velocities. Specifically, cases where the lowest critical velocity is replaced by a pseudo-critical value are optimized so that the vibration increase around this pseudo-critical velocity is negligible, and the next resonance as well as the onset of instability are as distant as possible. All results are presented (semi)analytically with very high precision and in dimensionless parameters to cover a wide range of scenarios. Then, real data are assigned to the optimal cases.

The paper is organized in the following way. In

Section 2, the model, involved parameters, and the governing equations are presented. In

Section 3, the terminology used is introduced, and issues related to the number of resonances and the role of critical and pseudo-critical velocities, including their similarities and differences, are explained, followed by the motivation for this work. In

Section 4, first, one case study is presented, followed by several methods and optimization techniques such as design of experiments, Monte Carlo analysis, parametric search, and simulated annealing. Optimized data are connected to real parameters and compared. The present paper is concluded by a discussion of the results obtained, their utility, and future challenges. After that, conclusions are drawn. The paper includes one Appendix where all numerical data are summarized for ease of comparison.

2. Governing Equations and Parameters

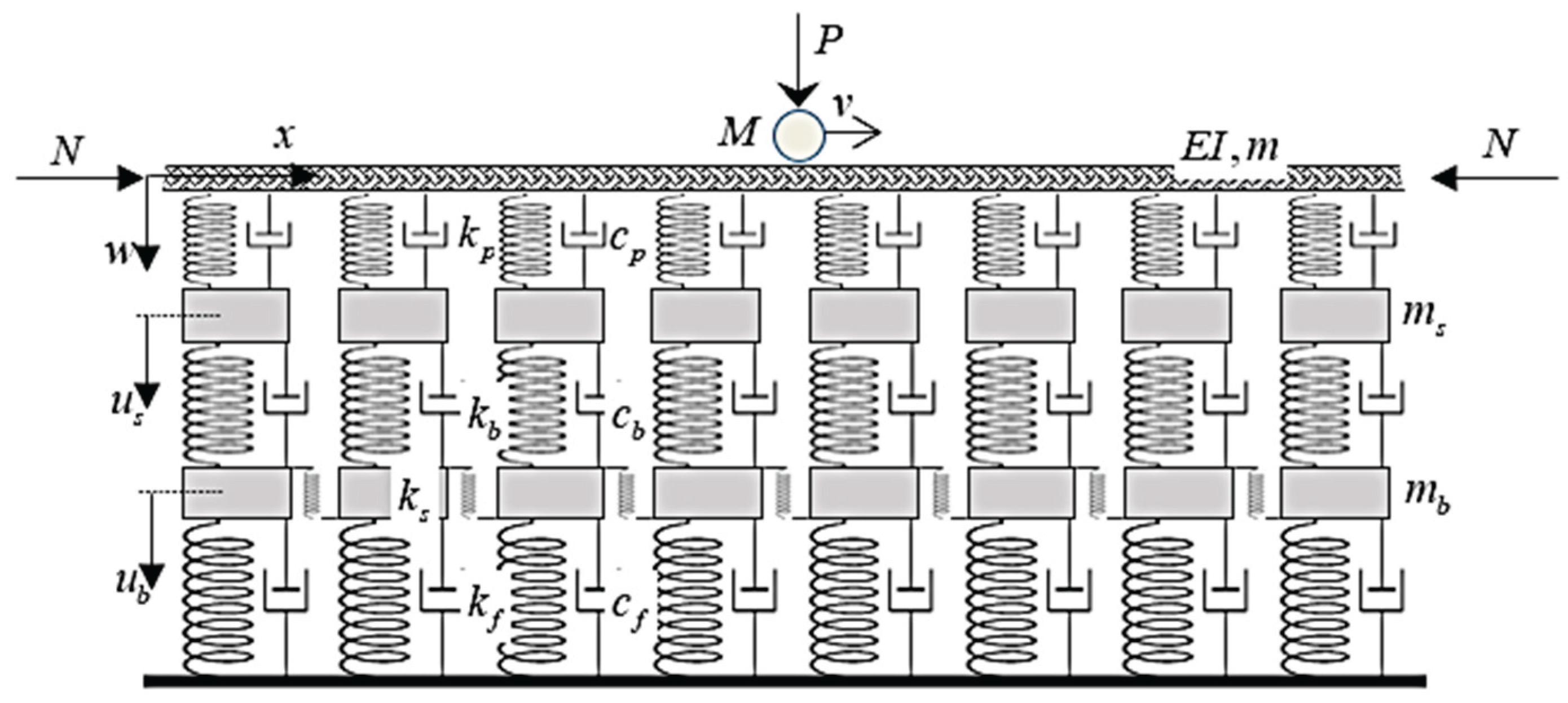

The three-layer railway track model is quite popular due to its simplicity, easy manipulability, computational efficiency, and good agreement with reality [

10]. It is schematically presented in

Figure 1 [

11].

To facilitate the analytical steps of the solution, all parameters are introduced into the governing equations in their distributed and dimensionless forms. Exploiting the symmetry, the model represents a half-track of a single-line straight section.

The governing equations in dimensionless parameters and moving coordinates read as (more details can be found in [

11]):

where

where

and

describe the Euler-Bernoulli beam on top of the model by its bending stiffness and mass per unit length. Further,

is the sleeper spacing,

and

are masses of the sleeper (half) and ballast cone,

,

,

and

are the vertical stiffnesses of the rail pads, ballast cone, and foundation, and the shear stiffness of the ballast layer, respectively, where

is usually defined as distributed, while the other values are discrete. The ballast cone theory according to [

26], and refined in [

27,

10], is essential in the definition of the governing parameters.

is the axial force and

the vertical force acting on a moving mass

that is traversing the model at constant velocity

. Unknown displacement fields of the beam

, the sleeper

, and the ballast

are functions of spatial coordinate

and time

. By switching to moving coordinates

passes to

and then to their dimensionless counterparts:

further

and other parameters in Equations (5) and (6) are masses (

and

), stiffnesses (

,

and

), damping ratios (

,

and

) and the axial force ratio (

). To complete the list of symbols

is the Dirac delta function, and derivatives are denoted by the symbol of the respective variable, preceded by a comma.

This means that a Winkler beam characterized by

,

and

is selected as the reference beam.

is inverse of its characteristic length,

is the critical velocity of a moving force, and

is therefore the velocity ratio. For identification of the moving mass instability, it is assumed that the mass is always in contact with the beam. Finally,

Considering the range of admissible parameters specified in detail in [

11], it is possible to conclude that the admissible ranges of the leading parameters are approximately as follows:

Nevertheless, it is also necessary to point out that there are general trends such as enlarging sleeper spacing, the introduction of novel lightweight materials, and other cost-saving measures, which can obviously affect these ranges.

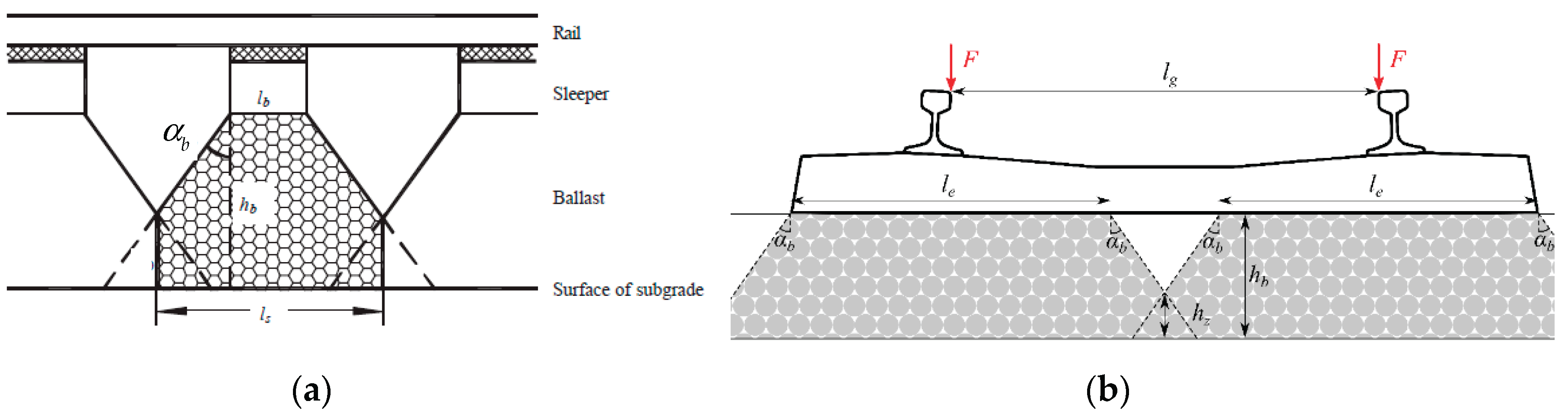

Admissible intervals in Equation (10) were obtained in the following way: first, geometrical data needed for the stress cone theory were assumed as:

All values except for

are given in [m].

,

and

are ballast height, base sleeper width, and angle of the ballast cone, as exemplified in

Figure 2, [

10].

Further,

and

are the rail gauge and the sleeper effective length. For the calculations,

is used as the most common value, and so

does not have to be introduced. Then, by using the ranges from Equation (11), the dynamically activated ballast volume

is within the range (0.065–0.7) m

3, and the parameter related to the vertical stiffness

ranges within (0.79–3.36) m (multiplication by the ballast Young´s modulus yields the correct base unit of N/m). According to [

10,

11], the range (40–160) kg is considered for

, and the ballast density

is taken within the range (1200–2600) kg/m

3. Further, values within the range (20–5000) MN/m are considered for

, and (50–400) MPa for the ballast Young’s modulus,

.

There is an obvious connection between

and

, as well as between

and

, as they are both connected to the reference beam. Their ratios must be bounded by the values determined as:

In what follows, “+” and “–“ will be used to identify the upper and lower bounds, respectively.

Additionally, it will be demonstrated that graphical representation in logarithmic scale for

and

is more advantageous, as already used in [

22,

11]. For the analysis in this paper, the full range does not have to be covered; thus, the following representation is proposed:

Which, for the ratios from Equation (13), defines a range for the difference between the indexes

and

:

3. Methods

3.1. Terminology

This subsection clarifies the adopted terminology. The moving force problem is defined as a longitudinally homogeneous supporting structure being traversed by a constant force at constant velocity. In such a case, the transient part of the solution is not very important, and if a steady-state solution exists, it is rapidly attained.

In this context: the critical velocity (CV) designates a velocity fulfilling four conditions:

(i) it marks a true resonance, meaning that when the force moves at this velocity, deflections tend to infinity in the undamped case (i.e., the steady-state solution is never reached);

(ii) this velocity marks a local minimum of the generalized mode number of an equivalent finite beam;

(iii) there is a sudden jump to zero deflection at the active point (AP) at a velocity infinitesimally higher; and

(iv) the CV value separates regions of instability in regular cases.

On the other hand, the false critical velocity (FCV), which is also a true resonance, marks a local maximum of the generalized mode number of an equivalent finite beam and has no influence on instability regions or the specific value at the AP.

In the three-layer model—as the three layers indicate—three CVs are expected, which means five resonances in the moving force problem: three corresponding to CVs and two to FCVs. In a regular case, there are five vertical asymptotes to the instability lines, marking two full branches in the first two regions delimited by the critical velocities; after that, the final branch tends to zero moving mass for infinite velocity [

22,

11].

Nevertheless, there are several exceptional cases. In fact, the number of resonances can be 1, 3, or 5. When it is less than 5, some FCVs do not exist, and CVs are replaced by pseudo-critical velocities (PCVs). Additionally, some cases at the boundary of separation regions may lead to a model exhibiting only three resonances, meaning two CVs and one FCV, or one CV and one PCV.

As already mentioned, when CVs are missing, they are replaced by PCVs. A PCV marks a peak in vibrations, but not an infinite value. Since no resonance occurs, even in the absence of damping, deflections never reach infinity. Unlike CVs, FCVs are never replaced, but they can be absent.

Determination of resonances can be done semianalytically as described in [

22], but high precision must be implemented. It is extremely important to perform such determinations in the absence of damping, which can unequivocally distinguish a vibration peak from a true resonance. Many methods used by other authors—such as the Green’s function method—require damping for numerical stability and are therefore unsuitable.

PCVs can be determined by parametric analyses. However, when the peak is hardly visible, the peak at the AP, the maximum, and the minimum over the whole beam are usually attained for different velocities, and thus its value is ambiguous. Numerical precision is also essential here. Even if the calculation must be done without damping, MATLAB can be used because the roots required for calculating the steady-state shape can be separated into those defining propagating and evanescent waves. Evanescent waves can be analyzed in the vicinity of the AP. For propagating waves, it is possible to establish an analytical envelope function that can unequivocally identify the maximum and minimum over the entire beam without enlarging the tested region around the AP.

Namely, as our interest lies in the initial region of , then when , there are two pairs of real roots and four complex roots symmetrically covering the four quadrants. Negligible damping can be introduced to correctly separate the real roots for the shape ahead of and behind AP. The four real roots define two harmonic waves with constant amplitude and zero phase. It is then possible to calculate the envelope function, which has clearly defined maximum and minimum values over the entire beam. It is then only necessary to check whether, in the vicinity of the AP, these values are exceeded due to evanescent waves. When , there is only one harmonic wave, so the amplitude is easily determined and an envelope function is unnecessary.

In the previous text, the term instability line was used. This relates to the instability of moving inertial objects. In such an analysis, the transient part of the solution is essential; without it, the problem of instability would remain hidden. Instability is not a resonance-type phenomenon; there is a velocity interval within which the object becomes unstable. At the extremities of this interval, the object remains stable, and instability is verified only within. This is characterized by an exponential increase in vibration amplitudes. Thus, although the steady-state solution usually exists and is finite, it is never reached.

Instability is determined by solving the roots of the characteristic equation. The roots always come in pairs, identifying the harmonic parts of the full solution. When this part grows exponentially, the roots are termed unstable. The instability line is traced in the ( – ) plane as a boundary between regions with a different number of unstable roots. In this paper, only one moving mass is considered. For this case, for a selected , it is possible to track real-valued frequencies until a real-valued equivalent stiffness (or flexibility) of the supporting structure is detected; then, is calculated from the characteristic equation. In this way, the analysis remains in the real domain, and the D-decomposition method used by other researchers can be avoided.

3.2. Determination of Number of Resonances and Pseudo-critical Velocities

Having the admissible range of dimensionless parameters, it is not easy to analytically indicate the regions corresponding to a particular number of resonances. Even though the base of the semianalytical solution is polynomial and all denominators are removed, the final degree is 16, and several roots are redundant. However, it is relatively easy to calculate the number of resonances semianalytically for a particular case using software with adaptable precision (e.g., Maple or Mathematica). MATLAB is not convenient in this context, as damping should not be included and high precision in root determination is required.

The number of resonances is always odd—1, 3, or 5—corresponding to 1, 2, or 3 critical velocities (CV) and 0, 1, or 2 false critical velocities (FCV), as explained in the previous section.

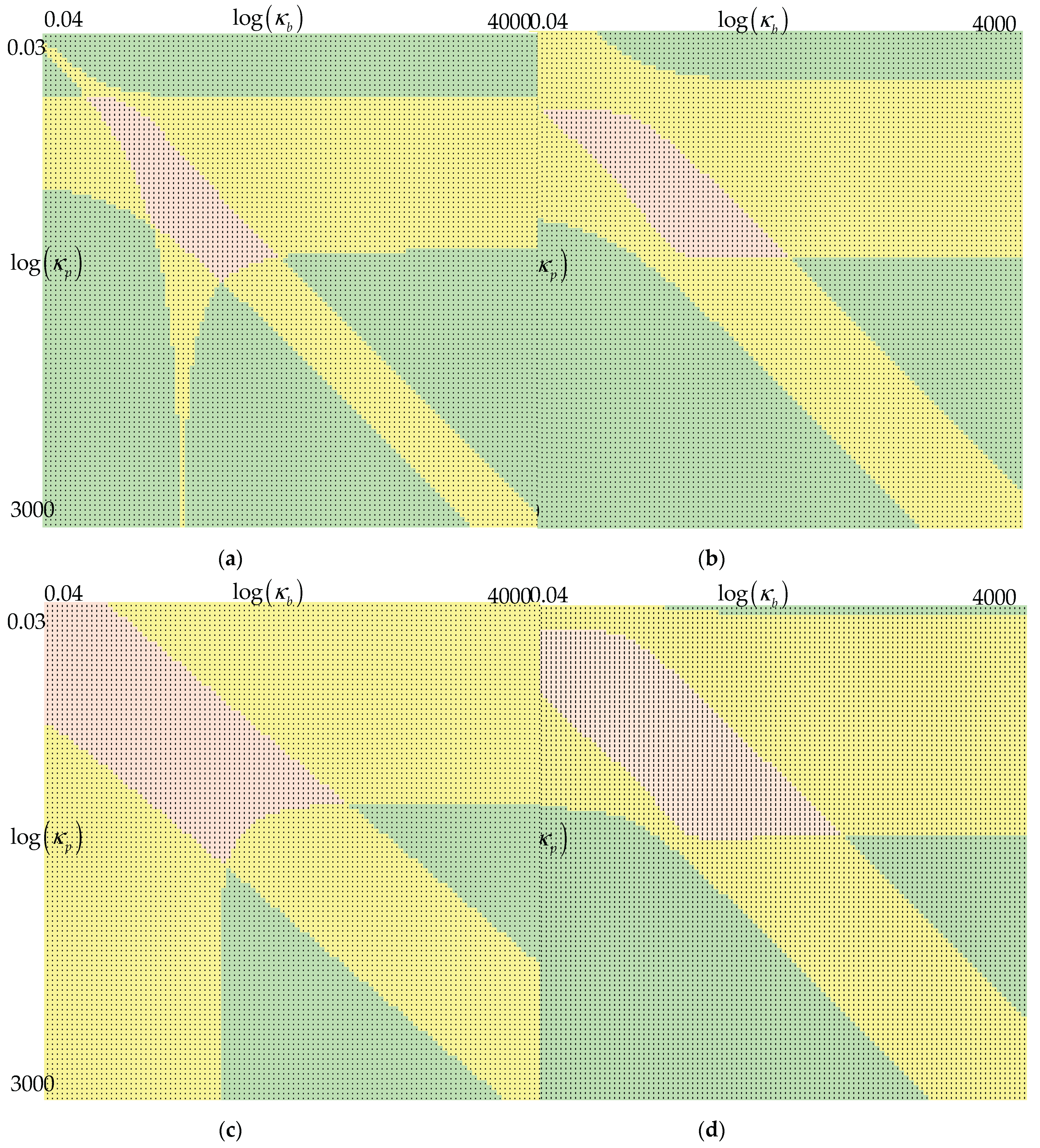

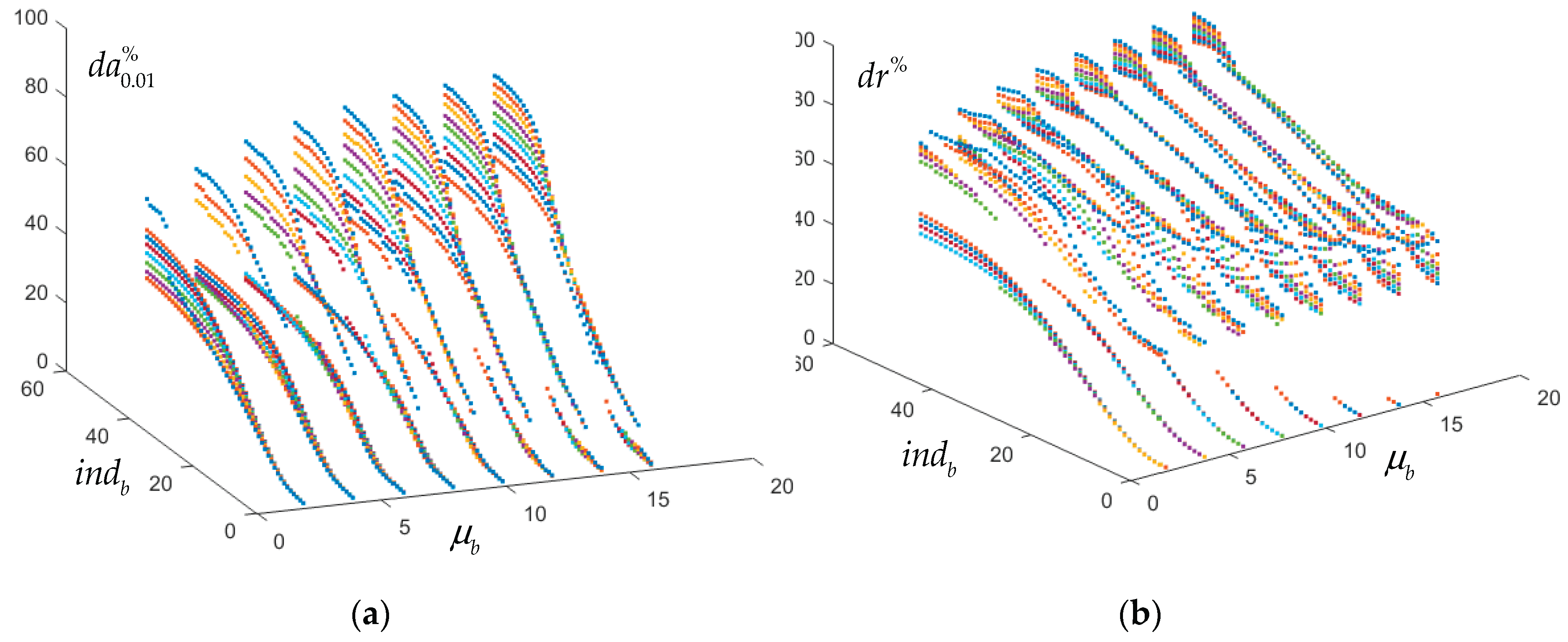

Four selected cases are shown as a demonstration in

Figure 3. It was found convenient to select

,

and

, or alternatively

and to use the logarithmic scale for

and

, as indicated in Equation (14). This means that both indexes

and

were selected for the semianalytical determination from discrete values ranging from 1 to 101 in increments of 1.

As already mentioned, these graphs can only be obtained semianalytically using Maple or similar software because MATLAB does not provide sufficient accuracy in root determination, which is essential.

Once the number of expected resonances is known, the pseudo-critical velocity (PCV) must be determined, as it is often lower than the first resonance. In such cases, the PCV plays the role of a critical velocity for track design. Specifically, in cases with fewer than 5 resonances, when the PCV is lower than the first resonance, it is identified as the velocity that should not be exceeded. Hence, it can be termed the design critical velocity (DCV).

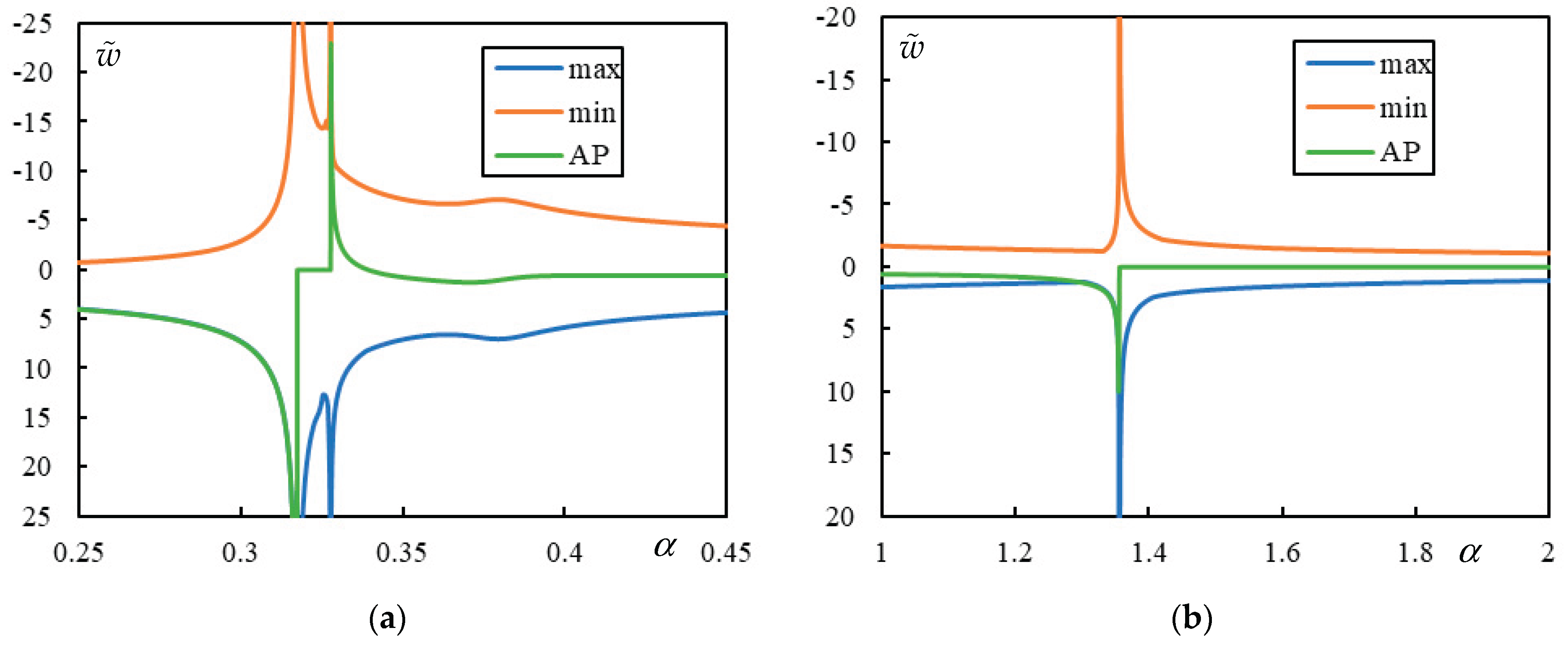

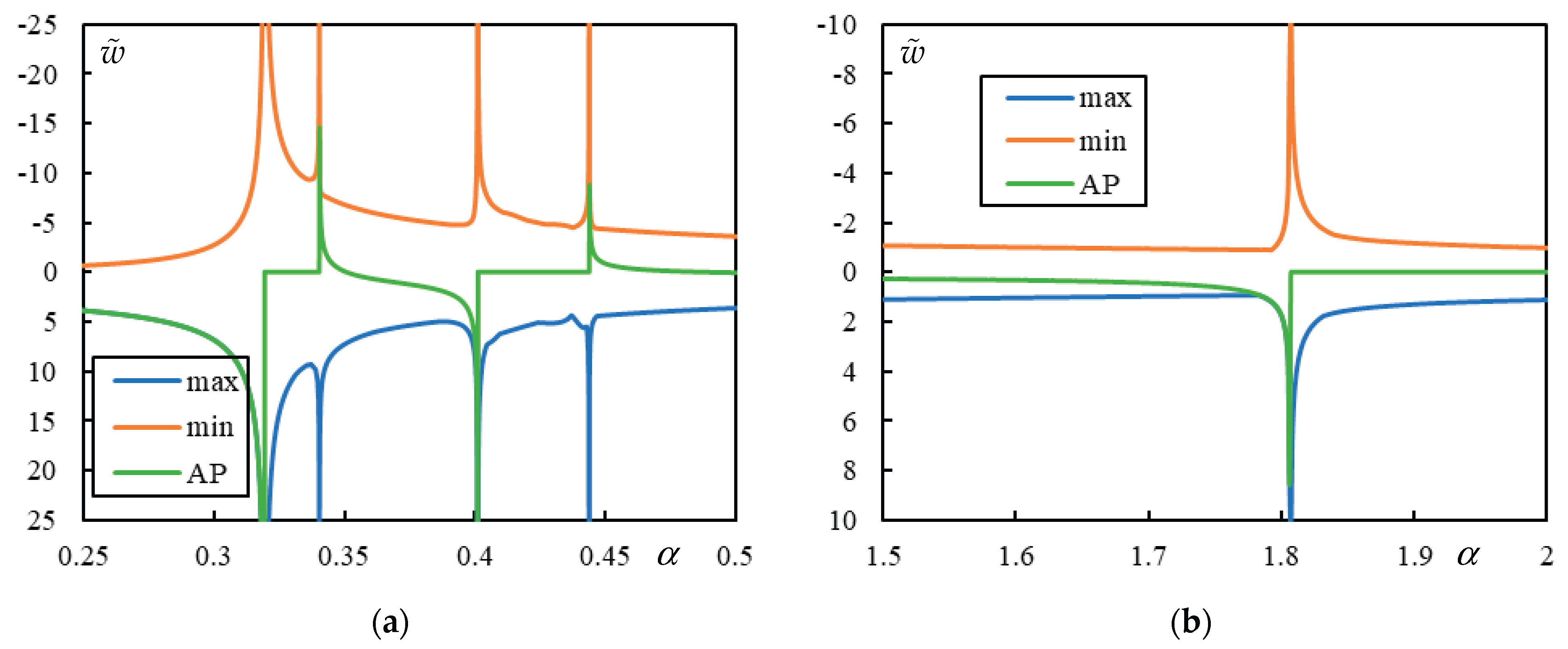

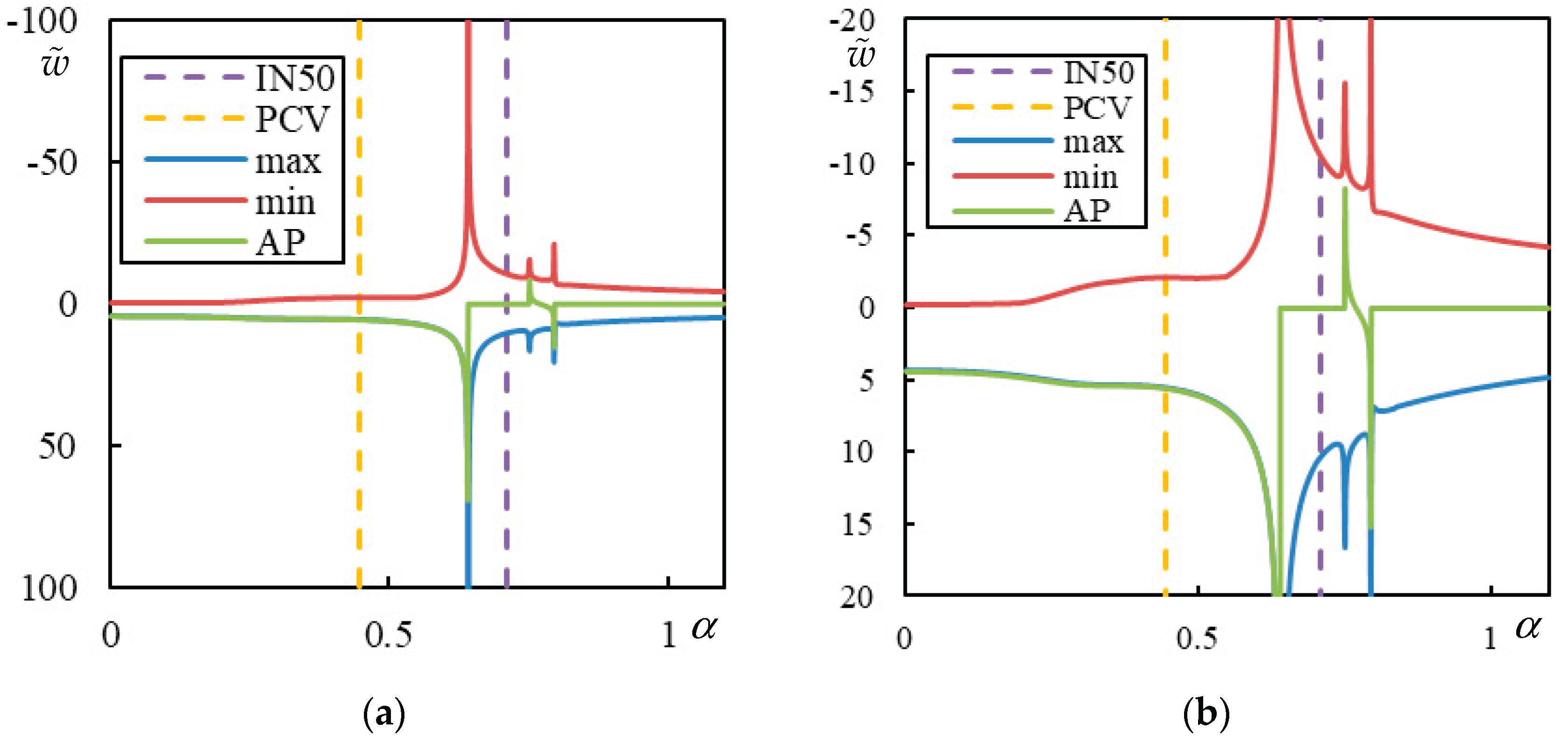

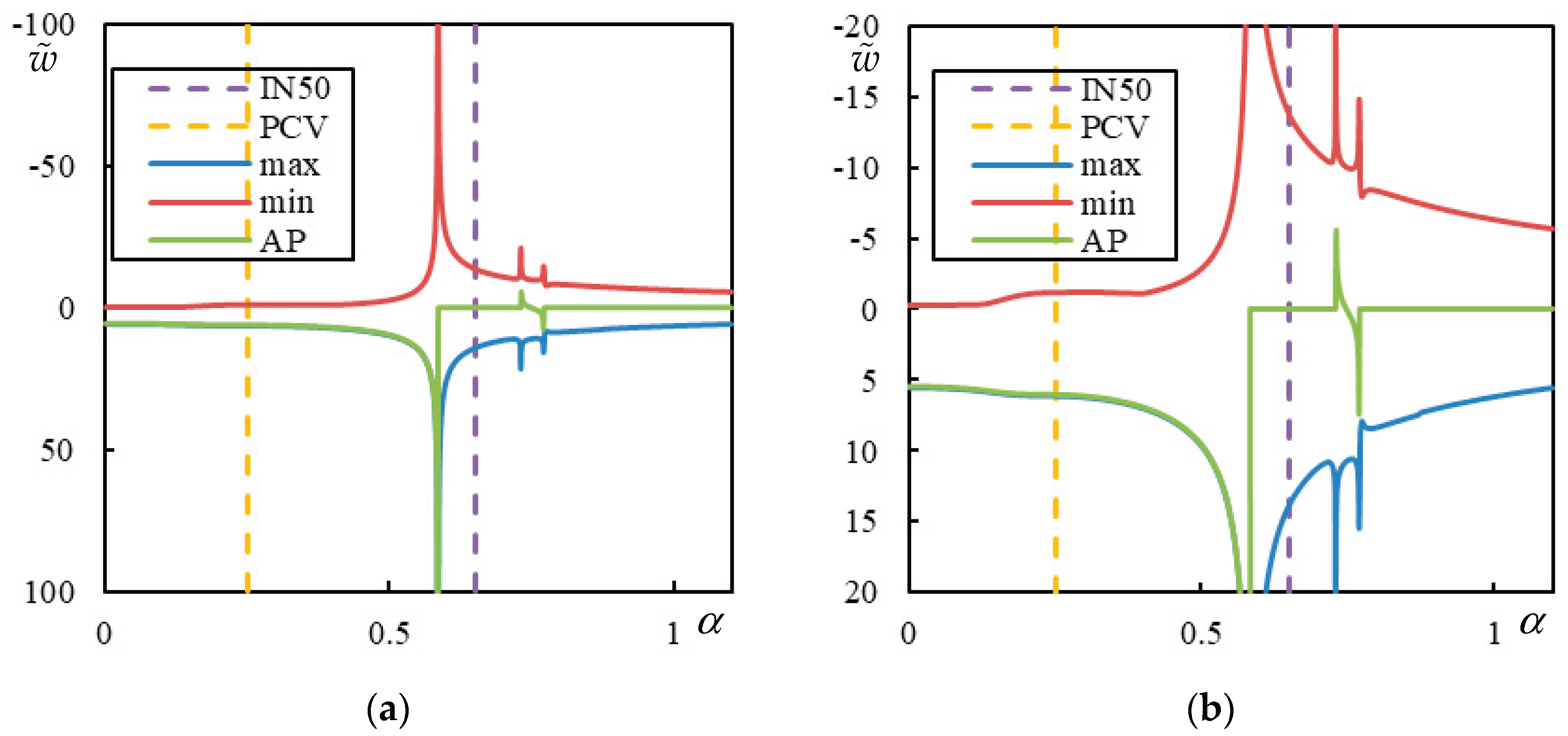

PCVs, which can be determined by parametric analysis, may be well-pronounced or ambiguous in the sense that the peaks do not always occur at the same position. The following figures explain these issues graphically. The case from

Figure 3(d) is selected first. Then, in addition to

,

and

(

) and

,

are used to identify cases with 1, 3, and 5 resonances..

In

Figure 4, the case with 1 resonance is shown. This is an exceptional case characterized by a maximum of 3 resonances. Since only one resonance is present, the FCV is absent. The PCV is relatively well-pronounced at

for both the maximum and minimum over the whole beam, while the peak at AP occurs at

. These values are determined with a precision of 0.001, which corresponds to the step size used in the parametric analysis. Resonance occurs at

.

In

Figure 5, the case with 3 resonances is shown. Two CVs are clearly marked by a sudden jump to zero at the AP:

and

. Then,

is the FCV. There is also a barely visible PCV with peaks at

for the maximum and minimum over the whole beam, while the peak at AP occurs at

. These values are determined with a precision of 0.0001, which is the step size used in the parametric analysis.

Finally, in

Figure 6, the case with 5 resonances is shown. Three CVs are clearly marked by a sudden jump to zero at the AP:

,

and

. Between them, two FCVs occur:

and

. There are no indications of other vibration peaks.

Several other cases are included in [

22,

11].

Due to the challenges in determining the PCV—first, the necessity of parametric analysis instead of semianalytical methods, and second, the ambiguity in identifying clear peaks—it is worthwhile to explore other possibilities. In

Figure 5, at least, the maxima and minima over the beam occurred at the same

, but this is not always the case. Therefore, the PCV can be ambiguous when the peaks do not coincide.

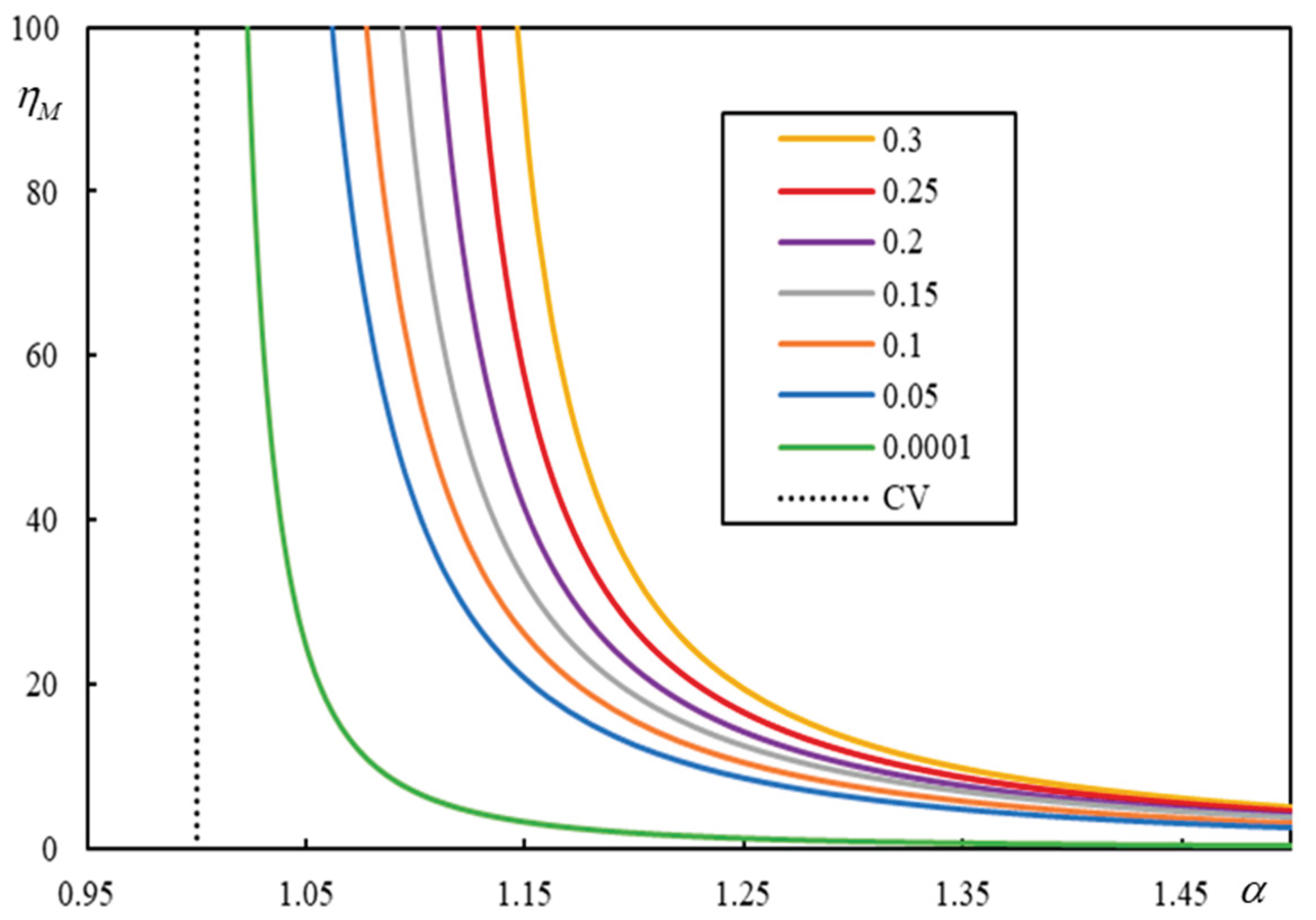

Since the PCV replaces the CV in separating instability regions, it is natural to propose that it should be predicted by

, which indicates a vertical asymptote in the instability line. This newly proposed approach exploits the regularity of the single moving mass problem, exemplified in the one-layer model in

Figure 7.

It is demonstrated in

Figure 7 that, as the damping ratio decreases, the instability lines approach the CV. Therefore, a very good estimate of the CV can be obtained by identifying the onset of instability for infinitely low damping. Such calculations can be performed semianalytically in Maple or similar software because a high number of digits of precision is required. Infinitely low damping and infinitesimally small real-valued frequency are used to find an

-value leading to a real-valued equivalent stiffness (or flexibility). The corresponding

tends to infinity.

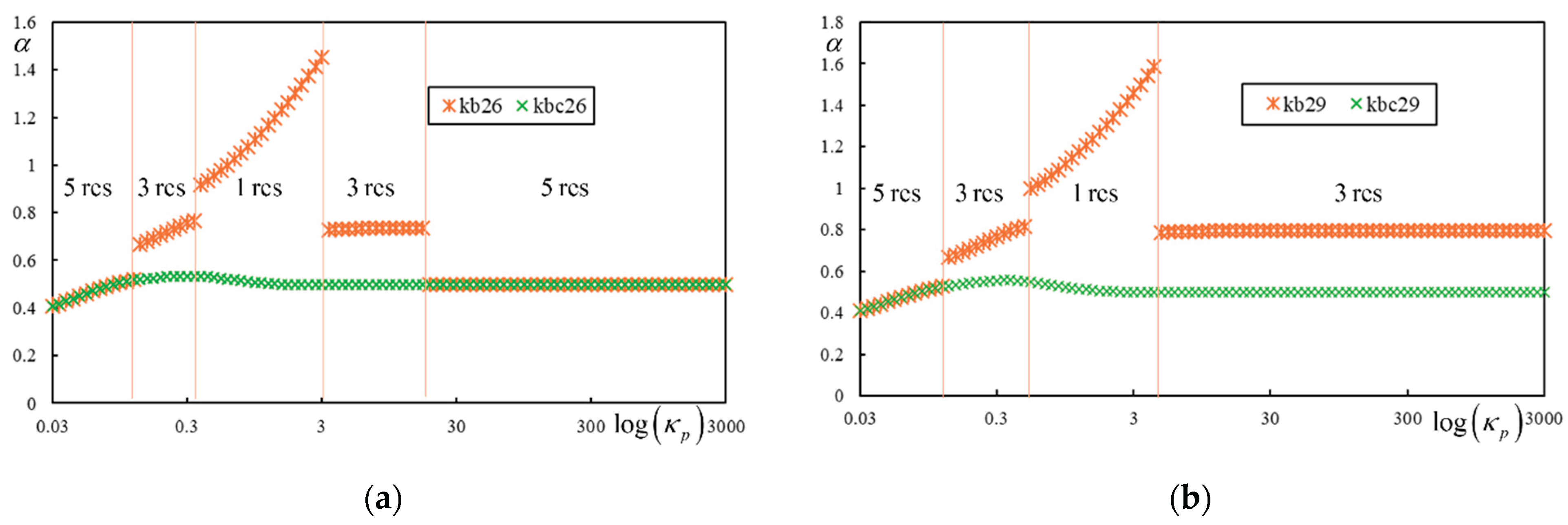

Applying the same reasoning to the three-layer model, it should be possible to identify the lowest PCV. This was tested for the case shown in

Figure 3(a) with

,

and

. In

Figure 8(a),

, and in

Figure 8(b),

. The latter case is the only one where the region of 3 resonances extends fully, and 5 resonances occur only at the very beginning.

It can be concluded from

Figure 8 that PCV identification works well: the line of green crosses is smooth, as expected. In regions with 5 resonances, the crosses coincide, while in other regions, green crosses indicate a much lower value. Nevertheless, there are cases—as already mentioned—where the maximum number of resonances is only 3. Then, the crosses match in the region of 3 resonances, as shown in

Figure 9, where the results of the parametric analysis are also included to show that no additional peaks occur (higher velocities are not shown but were tested). The graph in part (a) is plotted only up to

for clarity.

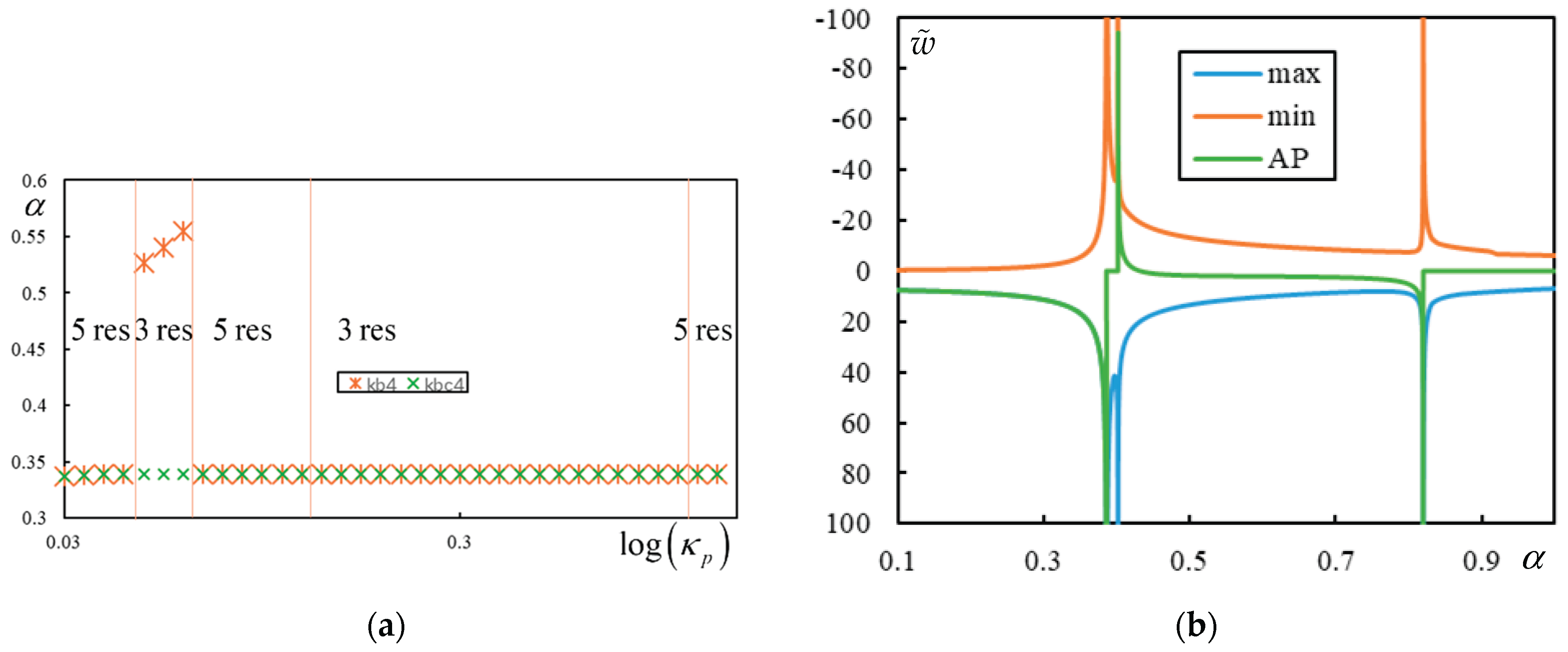

In

Figure 9(b), the resonances are: 0.339502; 0.377294 and 0.816655, corresponding to CV, FCV, and CV, respectively. The lowest asymptote is at

, which perfectly matches the lowest resonance. This shows that the proposed technique works well in most cases. However, there are exceptions where the lowest PCV is lower than the lowest asymptote. These cases are, in fact, the focus of this paper.

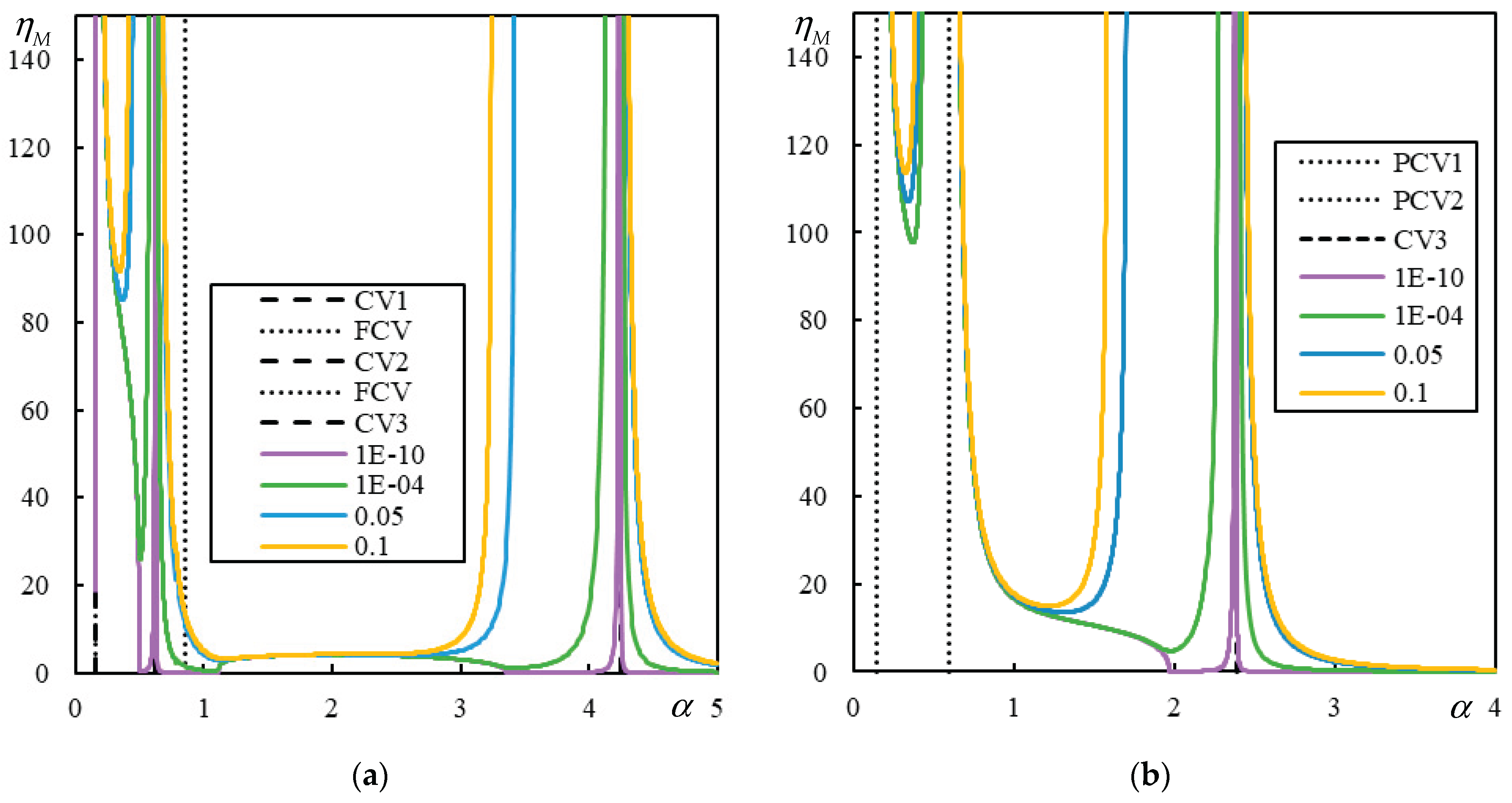

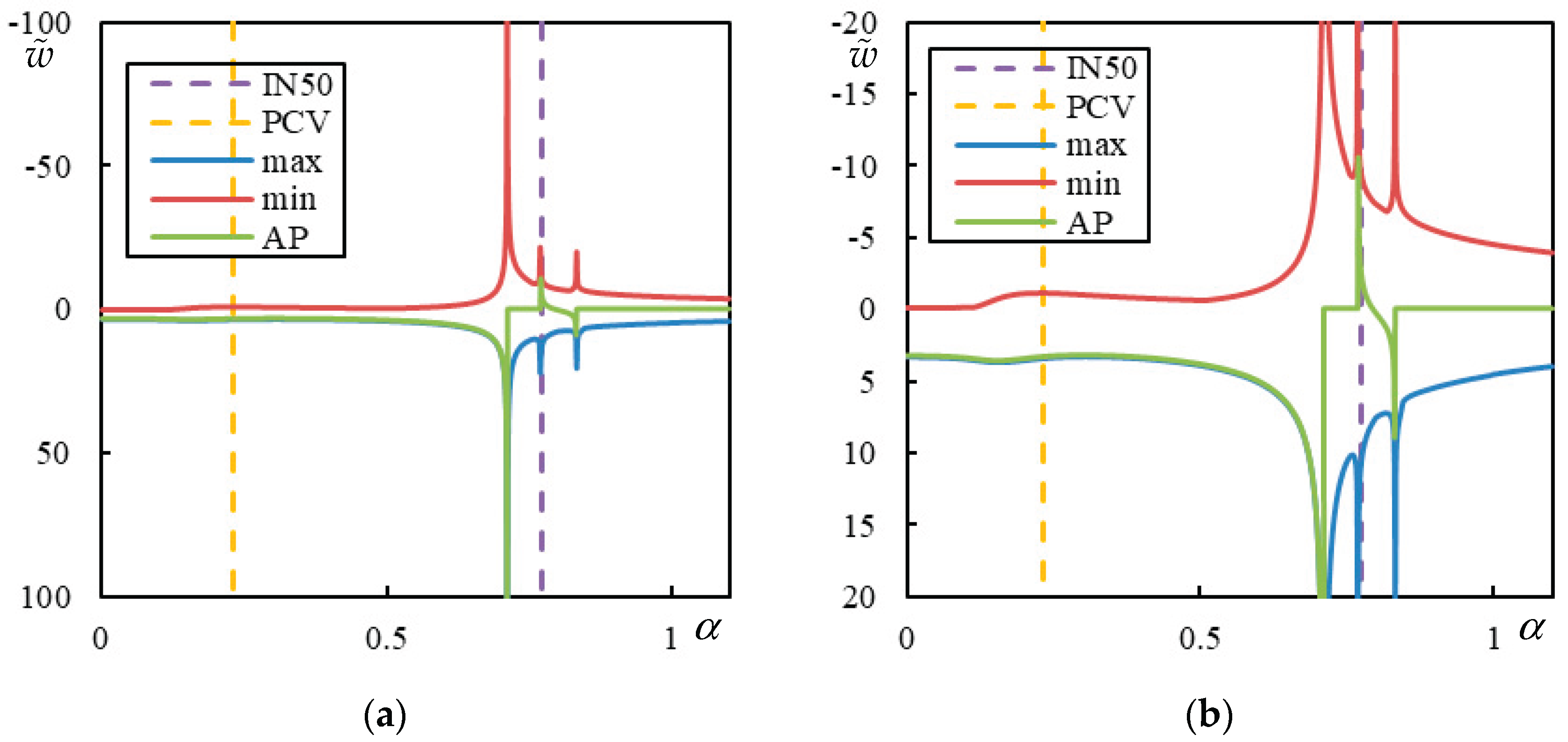

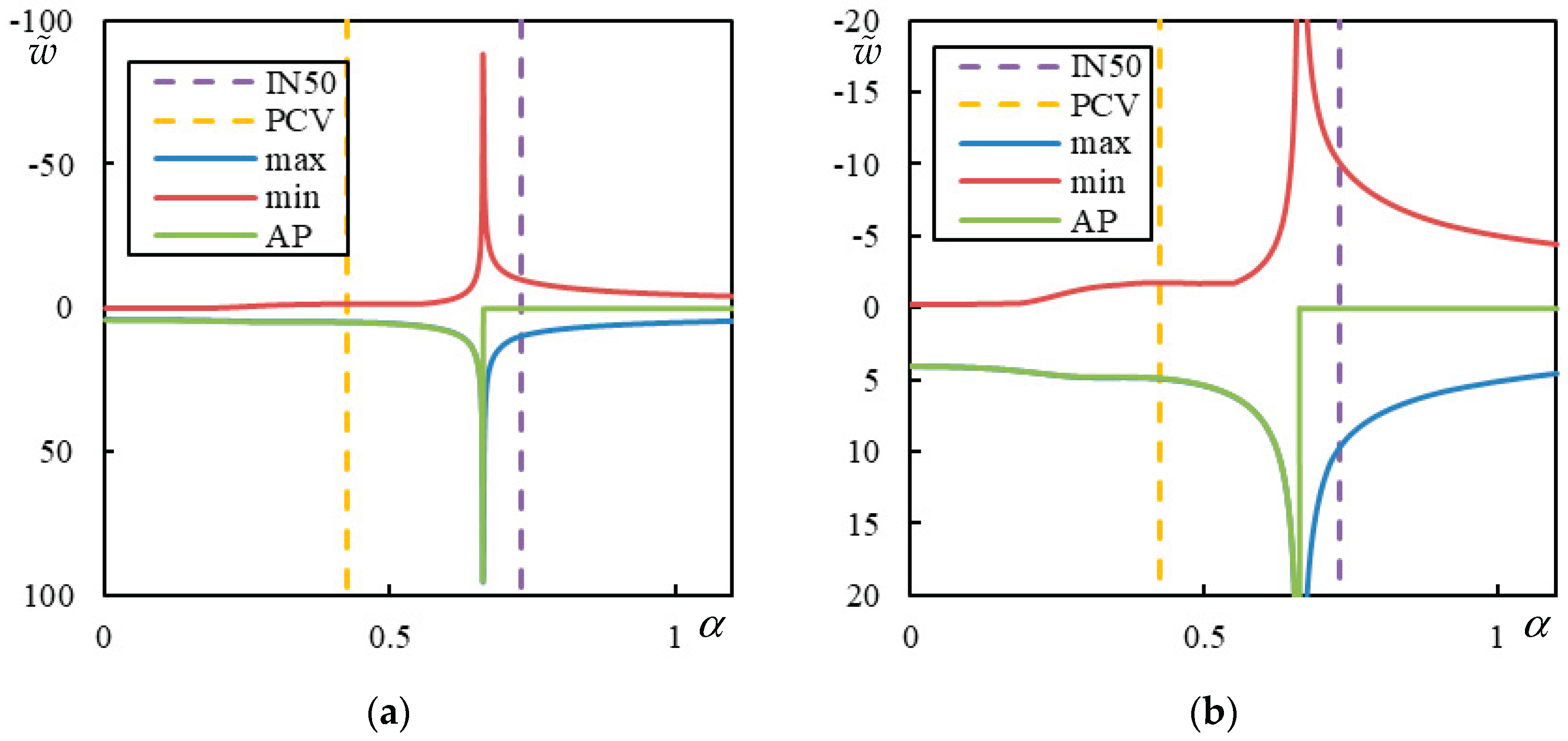

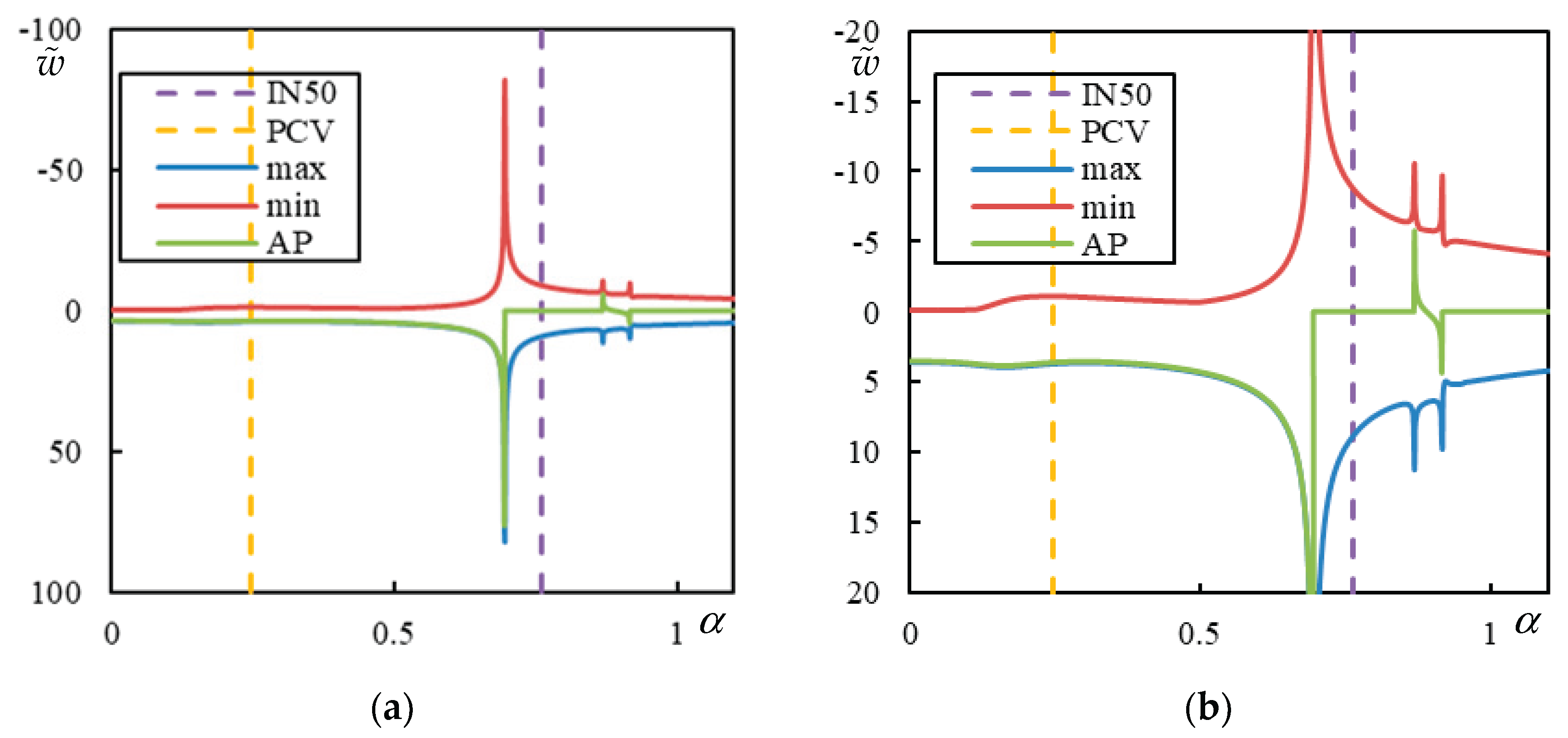

This section concludes by illustrating the effect of PCV, CV, and FCV on instability lines in typical cases. When there are 5 resonances, three of them correspond to CVs and two to FCVs. Five vertical asymptotes to the instability lines then appear, defining two full branches in the first two regions delimited by the CVs. Beyond that, the final branch tends to zero as approaches infinity. When there are fewer resonances, CVs may be replaced by PCVs. In contrast, FCVs are never replaced and may be absent, as already mentioned.

The same cases as previously shown in [

11] are selected for demonstration. These cases differ by

, highlighting how this parameter affects the number of resonances. Specifically, both cases have

,

,

and

. For

, there are 5 resonances (0.151–CV1; 0.152–FCV; 0.627–CV2; 0.851–FCV; 4.244–CV3). However, for

, there is only one (~0.149–PCV1; 0.599–PCV2; 2.388–CV3). This is demonstrated in

Figure 10.

It is clear from

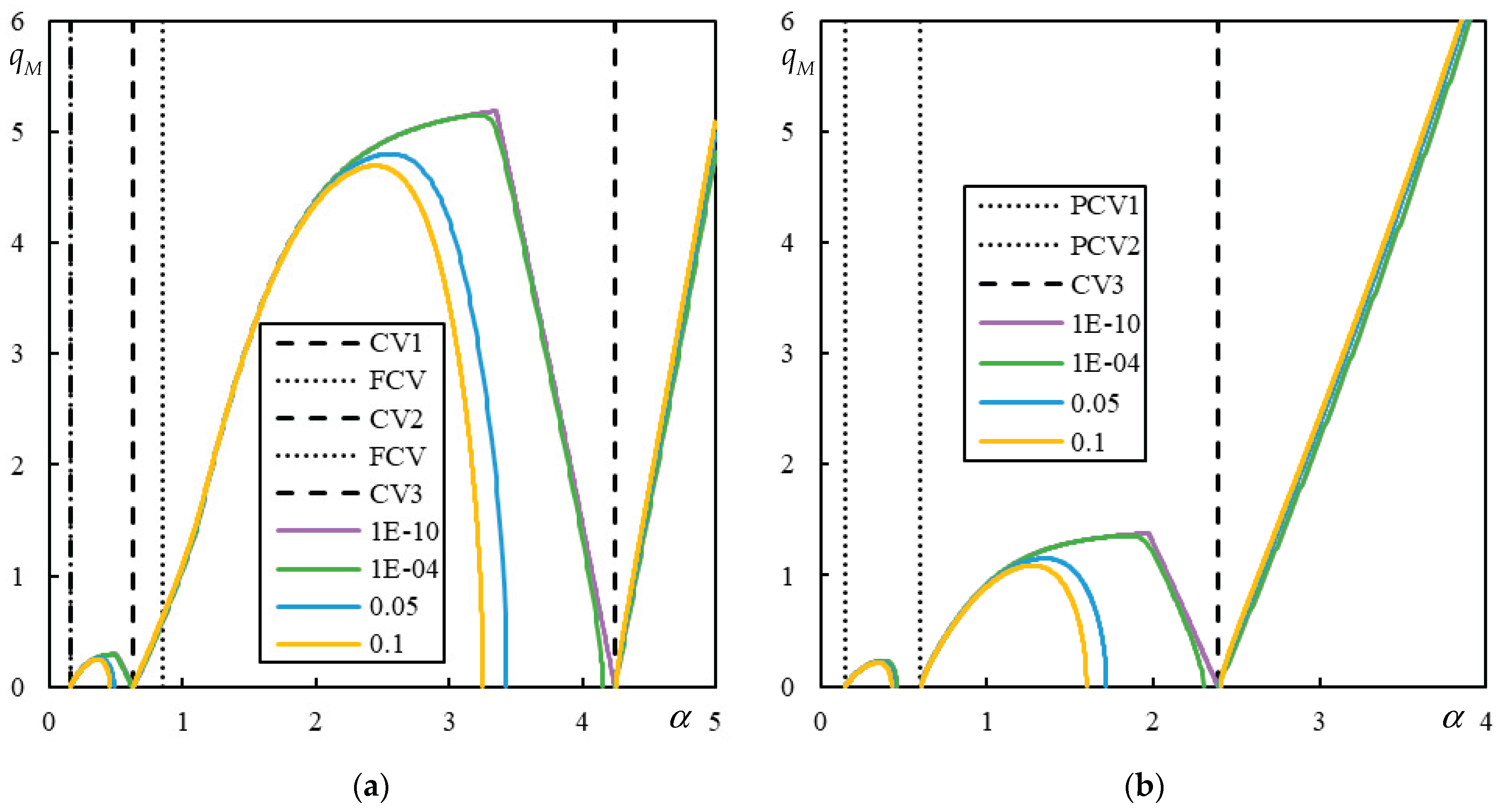

Figure 10 that the FCV does not influence the separation of instability lines into three distinct regions. It is further shown that PCVs act as CVs, and with decreasing damping, instability lines approach either the CV or PCV. In the middle region, larger deviations are observed from the right than from the left. To complete this analysis, the corresponding real-valued frequency

, which gives rise to

Figure 10 as a root of the characteristic equation, is plotted in

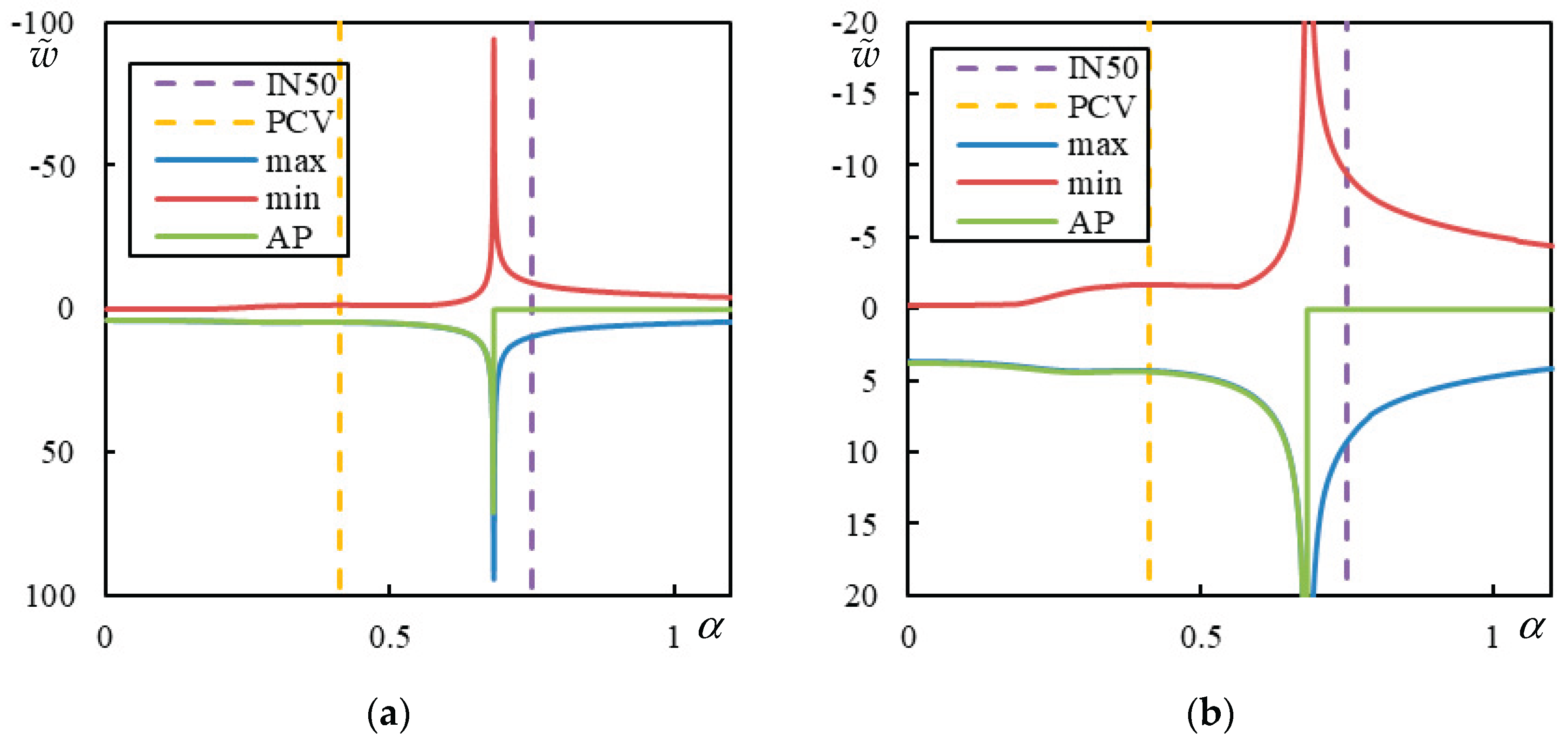

Figure 11.

Figure 11 again demonstrates that as damping decreases, CV and PCV are approached by vertical asymptotes for which

tends to zero and

tends to infinity. However, part (b) shows that in the first region, the damping level is not sufficiently low to clearly illustrate this behavior.

An interesting situation occurs when the above-described technique fails and such an asymptote does not exist. In these cases, only a slight increase in vibration is observed at the PCV. Alternatively, an asymptote may exist, but the instability line covers only unreasonably high values, so that instability cannot occur. In such cases, circulation velocities can exceed the expected critical velocity.

3.3. Motivation and Aim

As already mentioned, the motivation for this analysis lies in the observation that there are cases where the DCV is a PCV, which is not identified by a vertical asymptote. Thus, it appears possible to tailor the parameters in a way that reduces such vibrations, thereby extending the operational range into the supercritical region.

This suggests that it may be feasible to adjust the parameters of the model using optimization techniques so that the increase in vibrations remains minimal. Consequently, the DCV could be shifted to higher values without compromising safety—meaning, without the risk of excessive vibrations or potential instability. In more detail, the parameters must be adjusted such that the peak at the PCV is minimized, while simultaneously ensuring that the first resonance and the onset of instability for a reasonable value of and a moderate damping level occur at the highest possible velocity.

Mathematically, the first criterion is defined as the ratio between the highest upward displacement at the DCV = PCV, denoted , and the maximum downward displacement in the static case, . The reasoning is twofold: first, because dimensionless displacements are scaled with respect to the static displacement of a reference beam, it would not be reasonable to use unity for comparison; second, because upward displacements are more critical, they were chosen as the primary criterion.

This criterion is combined with two others: the lowest resonance

, and the velocity at the onset of instability

for a representative mass

under 1% damping ratio at all levels,

. Based on these, the performance index (PI) is defined as:

This PI also serves as the objective function, with the aim of finding its minimum within the admissible domain.

Several optimization methods were tested, beginning with statistical analyses—in particular, design of experiments (DOE) and response surface methodology—followed by parametric search (PS), the Monte Carlo method (MC), and Simulated Annealing (SA). It was also examined whether a full analysis was necessary or if some pre-selection could be applied. Certain parts required computation in Maple due to the need for increased numerical precision, while other parts could be handled in MATLAB.

6. Discussion

In the previous sections, several feasible designs for which PI was evaluated as optimal have been presented. It is worthwhile to remark that was never decisive in these cases, and the extension of DCV was always guided by . From Table 1, it is evident that and exhibit higher dispersion, while and have very similar values in all cases. Finally, appears almost exclusively, except in the MC method—likely because a zero value was improbable to be selected randomly along with other optimal parameters. Furthermore, higher generally provides larger improvements, and is always much lower than .

at minimum value of PI was gradually increased util at least one feasible design appeared in all cases, except for DOE, where, in fact, no optimization was presented. Since these designs are the first to appear, this implies that some data will lie at the limit values of the considered ranges. As such, they might seem unrealistic, but it must be noted that further increase of can lead to better selections without significantly compromising the PI value. Generally, for higher , the possible increase up to is more favorable; however, the ratio is increasing.

Parametric searches with a base value of can naturally only identify designs where this is possible—meaning designs using wooden sleepers. Nevertheless, this option was not disregarded, because it is essential to consider the possibility of using novel lightweight materials in the future.

Some of the real data from Table 2 and Table 3 may seem unreasonable, but this results from the initial ranges of possible values.

Due to the consistency of results obtained by different approaches, exploring other methods would not be useful.

The results confirm that preselection is useful and reduces calculation time, but the connections are not straightforward. It is not necessarily true that the best preselection yields the best PI and, at the same time, the highest possible increase in DCV.

When using the lowest feasible , combinations with relatively high led to the appearance of the lowest found in the literature in all feasible data shown in Table 3. Similarly, for the same reason, is relatively high, resulting in quite high DCV—difficult to attain with current train designs. This implies that although the possible increase is large, it may be practically unimportant. Nevertheless, these results may inspire new approaches and provide guidance toward optimizing track design.

Further analyses are needed to verify whether PI was defined appropriately or if it should be modified. Since instability was never found to be decisive, it can likely be excluded from this analysis, allowing more detailed investigations.

Additional tests are also necessary because although several authors use this model without shear resistance, it must be verified whether such modeling is truly valid in practical applications.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, tailoring of input geometric and material data of the railway track was presented, with the objective of identifying cases where the first increase in vibrations is negligible and can therefore be bypassed.

Several optimization techniques and approaches were employed, leading to similar conclusions. However, the results require further examination in several aspects. In particular, the adequacy of the proposed PI must be evaluated. Since all results showed very high DCV with negligible increase in vibration, the significance of a further increase diminishes. It is thus necessary to investigate whether similar outcomes could be achieved for lower real velocities, where the potential for meaningful improvements is greater.

Results were obtained semianalytically with very high precision. This was crucial for accurately determining the number of resonances and identifying the first peak in upward vibration.

It was found that DCV can be significantly increased by optimizing the design parameters. However, such cases almost exclusively result in designs where the DCV is already very high. Therefore, the practical significance of further increase becomes questionable, as already mentioned above.

In all cases, very soft rail pads emerged in the final optimized design. It is essential to verify whether such configurations are feasible. Thus, the results suggest a tendency toward:

Further research is particularly needed regarding ballast shear stiffness. In actual designs, eliminating it entirely may not be realistic. While it might be reduced via rail pretension, such an approach is not practical.

Due to the scope of this study, these aspects will be addressed in future research. It is believed that the theoretical findings presented here can contribute to the development of optimal track designs incorporating novel materials. Their implementation in real-world designs remains a subject for further investigation.

Figure 1.

The three-layer model of the railway track traversed by a moving mass, [

11].

Figure 1.

The three-layer model of the railway track traversed by a moving mass, [

11].

Figure 2.

Parameters related to stress cone theory.

Figure 2.

Parameters related to stress cone theory.

Figure 3.

Number of resonances in selected cases (1 – red, 3 – yellow, 5 – green): (a) , , ; (b) , , ; (c) , , ; (d) , , .

Figure 3.

Number of resonances in selected cases (1 – red, 3 – yellow, 5 – green): (a) , , ; (b) , , ; (c) , , ; (d) , , .

Figure 4.

Parametric analysis (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – orange displacement over the entire beam): , , , and

Figure 4.

Parametric analysis (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – orange displacement over the entire beam): , , , and

Figure 5.

Parametric analysis (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – orange displacement over the entire beam): , , , and Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale.

Figure 5.

Parametric analysis (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – orange displacement over the entire beam): , , , and Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale.

Figure 6.

Parametric analysis (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – orange displacement over the entire beam): , , , and Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale.

Figure 6.

Parametric analysis (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – orange displacement over the entire beam): , , , and Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale.

Figure 7.

Single moving mass problem on the one-layer model. Numbers in the legend represent the damping ratio. The dotted line marks the CV at .

Figure 7.

Single moving mass problem on the one-layer model. Numbers in the legend represent the damping ratio. The dotted line marks the CV at .

Figure 8.

Determination of the lowest PCV in the three-layer model. , and : (a) ; (b) . Orange crosses designate the lowest resonance; green crosses mark the lowest asymptote. Vertical orange lines separate regions based on the number of resonances.

Figure 8.

Determination of the lowest PCV in the three-layer model. , and : (a) ; (b) . Orange crosses designate the lowest resonance; green crosses mark the lowest asymptote. Vertical orange lines separate regions based on the number of resonances.

Figure 9.

Determination of the lowest PCV in the three-layer model. , and : (a) ; (b) the corresponding parametric analysis for . Orange crosses designate the lowest resonance; green crosses mark the lowest asymptote. Vertical orange lines separate regions based on the number of resonances.

Figure 9.

Determination of the lowest PCV in the three-layer model. , and : (a) ; (b) the corresponding parametric analysis for . Orange crosses designate the lowest resonance; green crosses mark the lowest asymptote. Vertical orange lines separate regions based on the number of resonances.

Figure 10.

Instability lines for , , and . (a) ; (b) . Dasher and dotted lines represent CV, FCV and PCV. Solid lines in different colors indicate different damping levels for .

Figure 10.

Instability lines for , , and . (a) ; (b) . Dasher and dotted lines represent CV, FCV and PCV. Solid lines in different colors indicate different damping levels for .

Figure 11.

Real-valued frequency for , , and . (a) ; (b) . Dasher and dotted lines represent CV, FCV and PCV. Solid lines in different colors indicate different damping levels for .

Figure 11.

Real-valued frequency for , , and . (a) ; (b) . Dasher and dotted lines represent CV, FCV and PCV. Solid lines in different colors indicate different damping levels for .

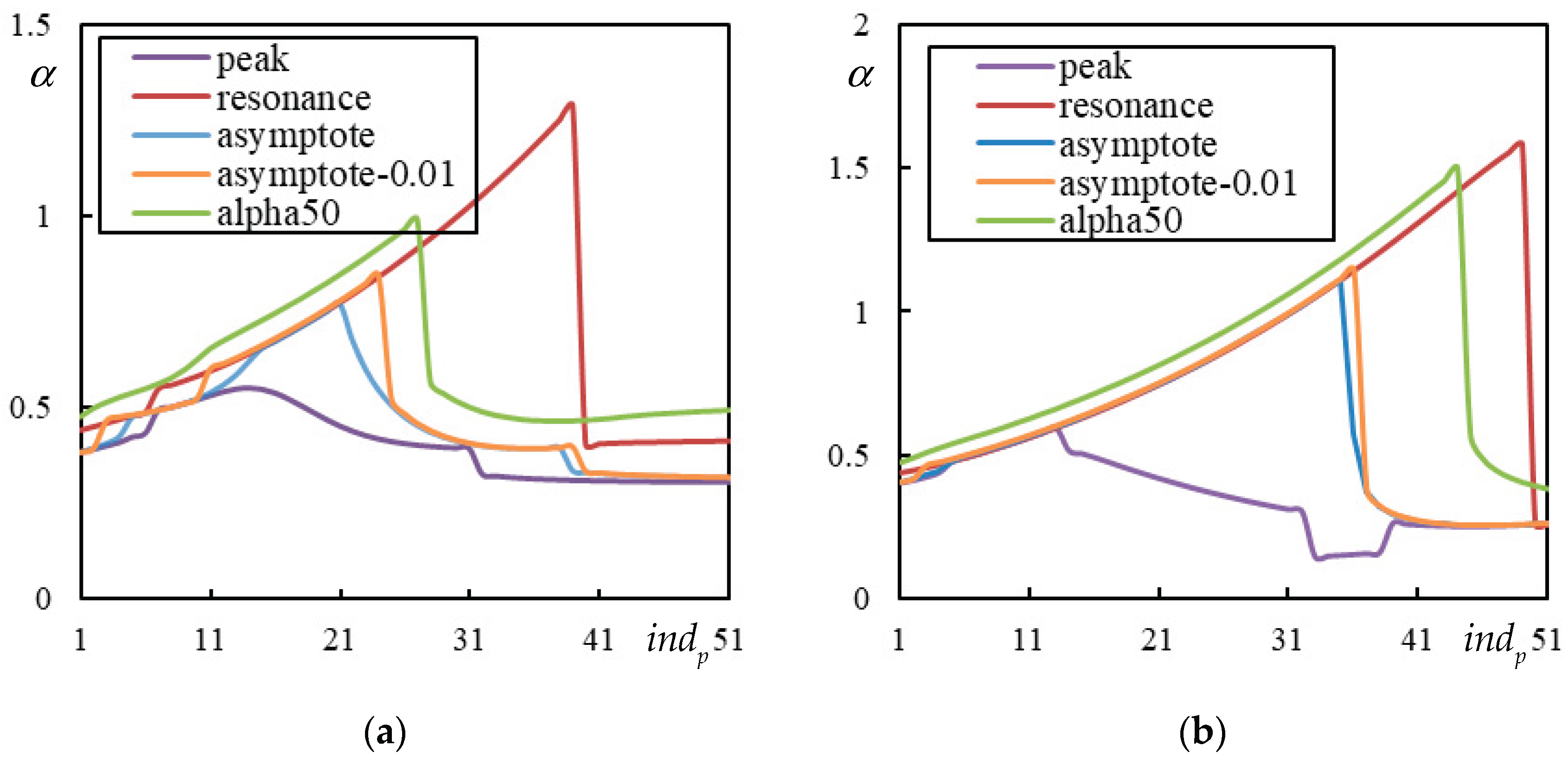

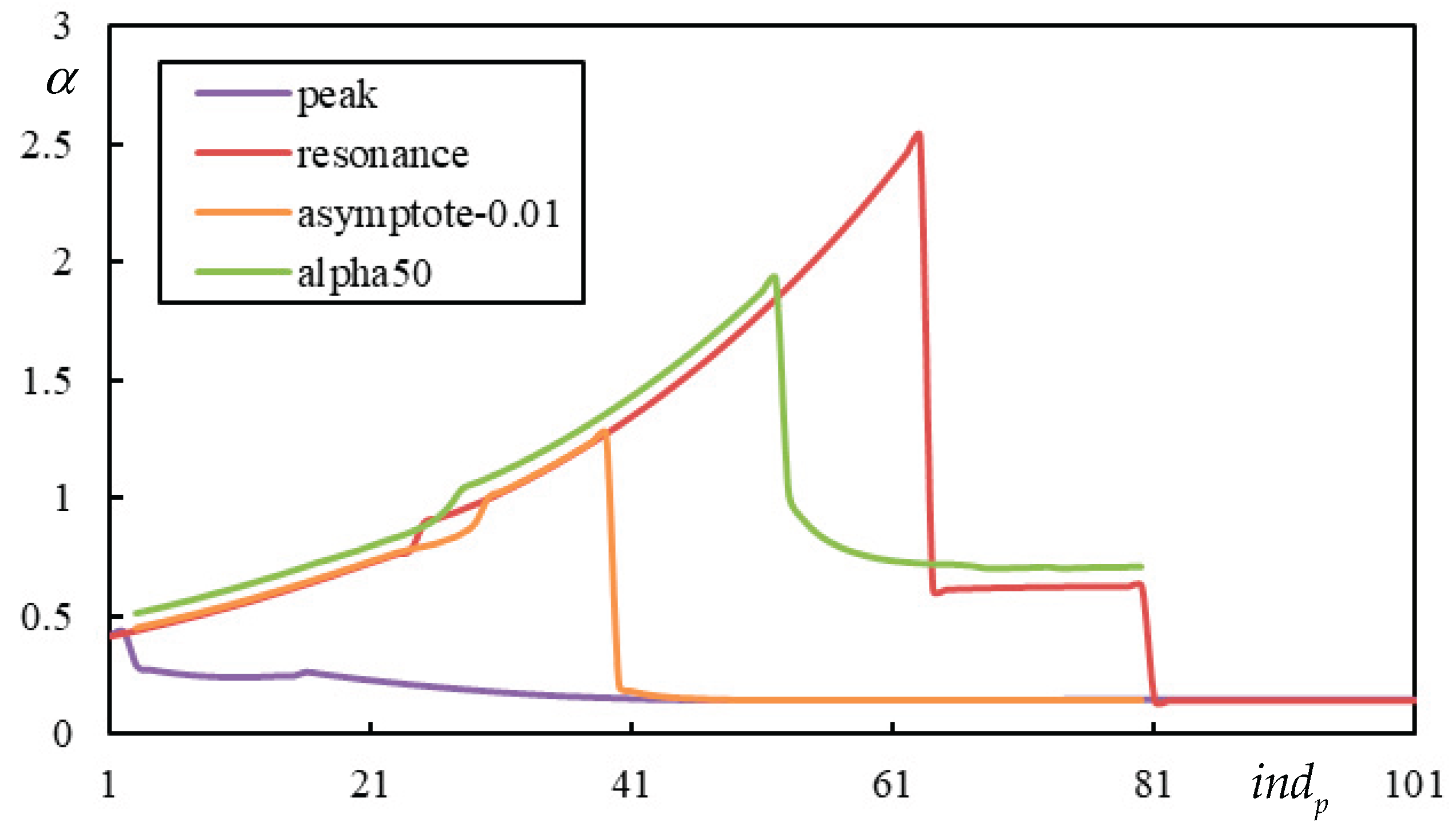

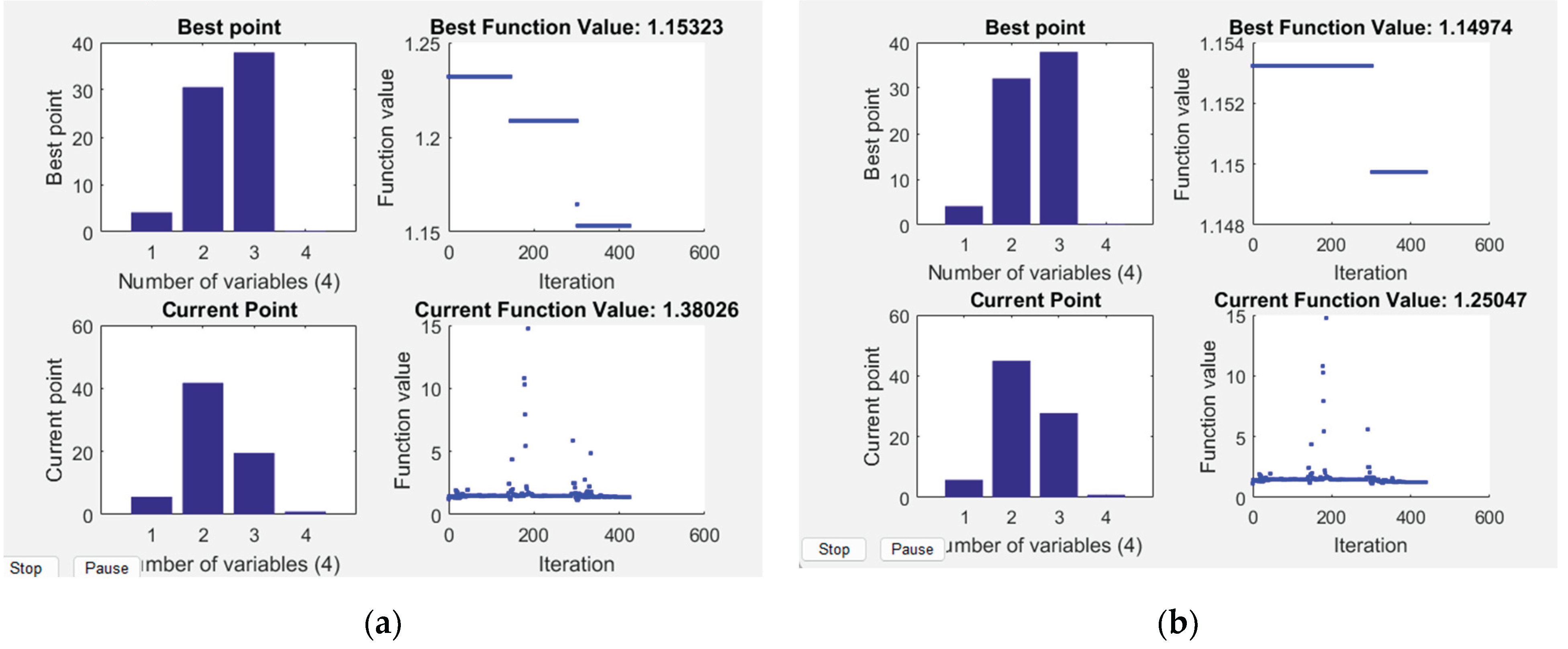

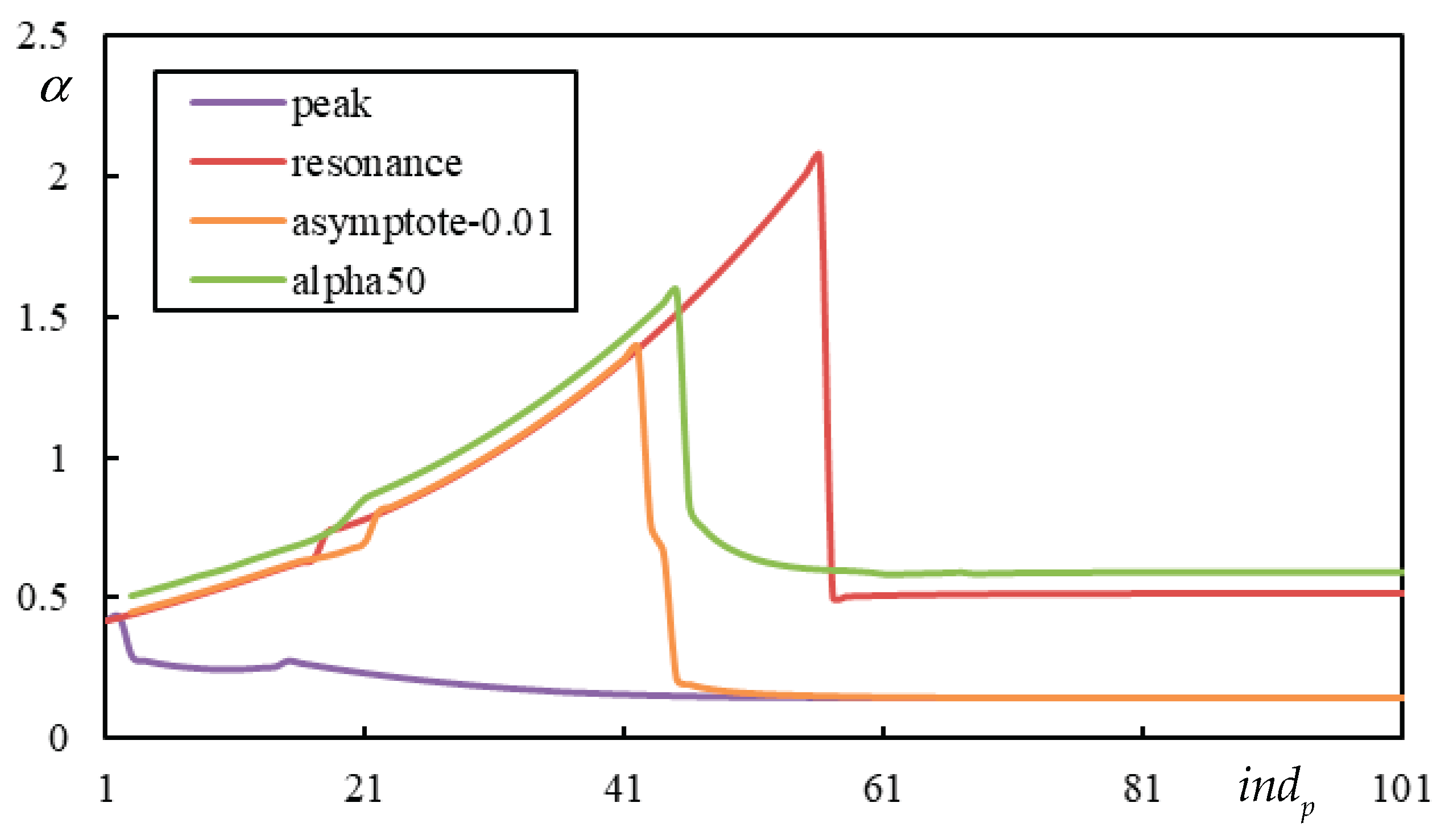

Figure 12.

Analysis related to determination of PI for , and . (a) ; (b) . In the legend: “peak” (violet) is PCV; “resonance” (red) is ; “asymptote” is at the lowest asymptote to instability lines (blue – negligible damping ; orange – 1% damping ); “alpha50” is .

Figure 12.

Analysis related to determination of PI for , and . (a) ; (b) . In the legend: “peak” (violet) is PCV; “resonance” (red) is ; “asymptote” is at the lowest asymptote to instability lines (blue – negligible damping ; orange – 1% damping ); “alpha50” is .

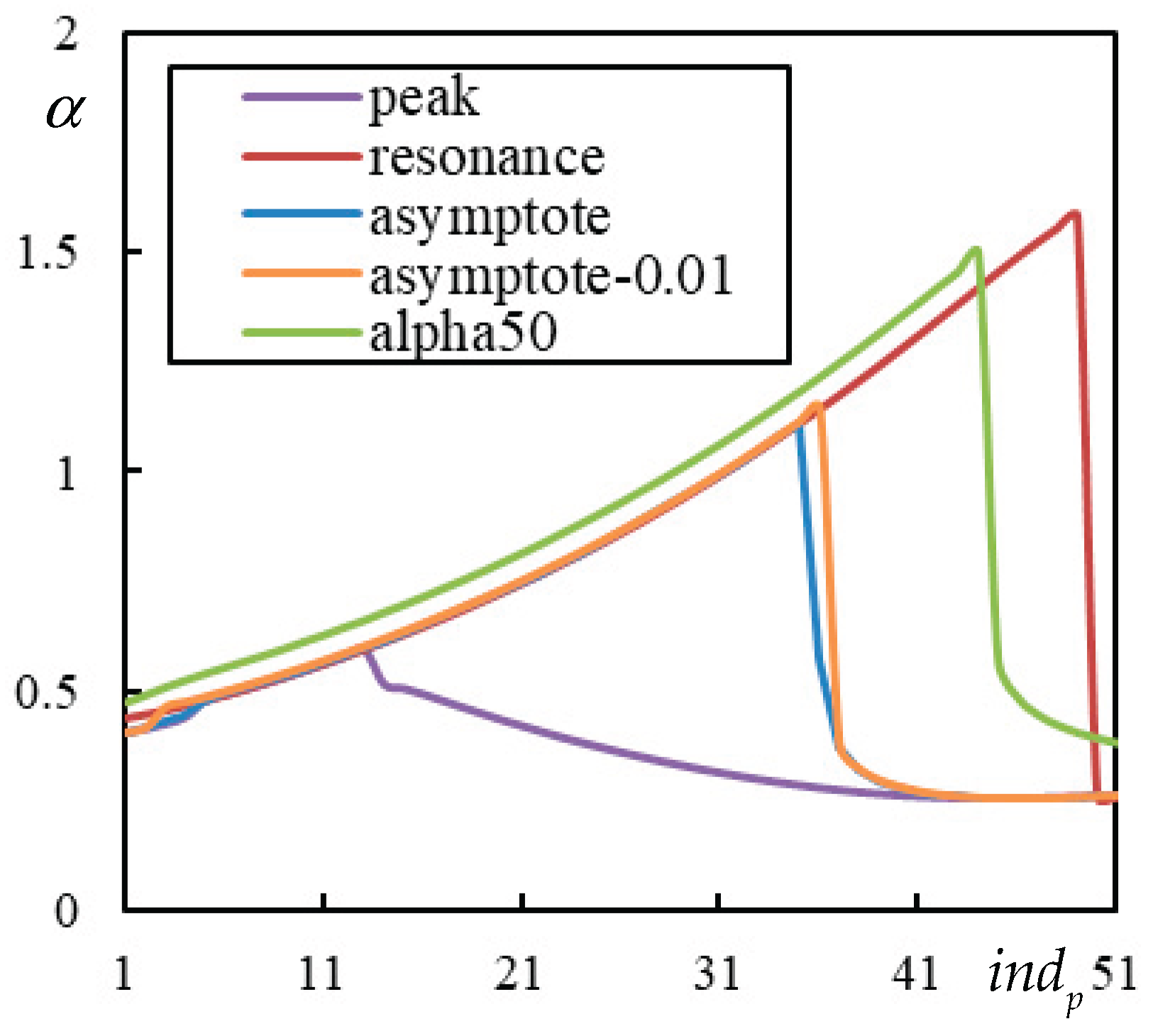

Figure 13.

Analysis related to determination of PI for , , and . In the legend: “peak” (violet) is regularized PCV; “resonance” (red) is ; “asymptote” is at the lowest asymptote to instability lines (blue – negligible damping ; orange – 1% damping ); “alpha50” is .

Figure 13.

Analysis related to determination of PI for , , and . In the legend: “peak” (violet) is regularized PCV; “resonance” (red) is ; “asymptote” is at the lowest asymptote to instability lines (blue – negligible damping ; orange – 1% damping ); “alpha50” is .

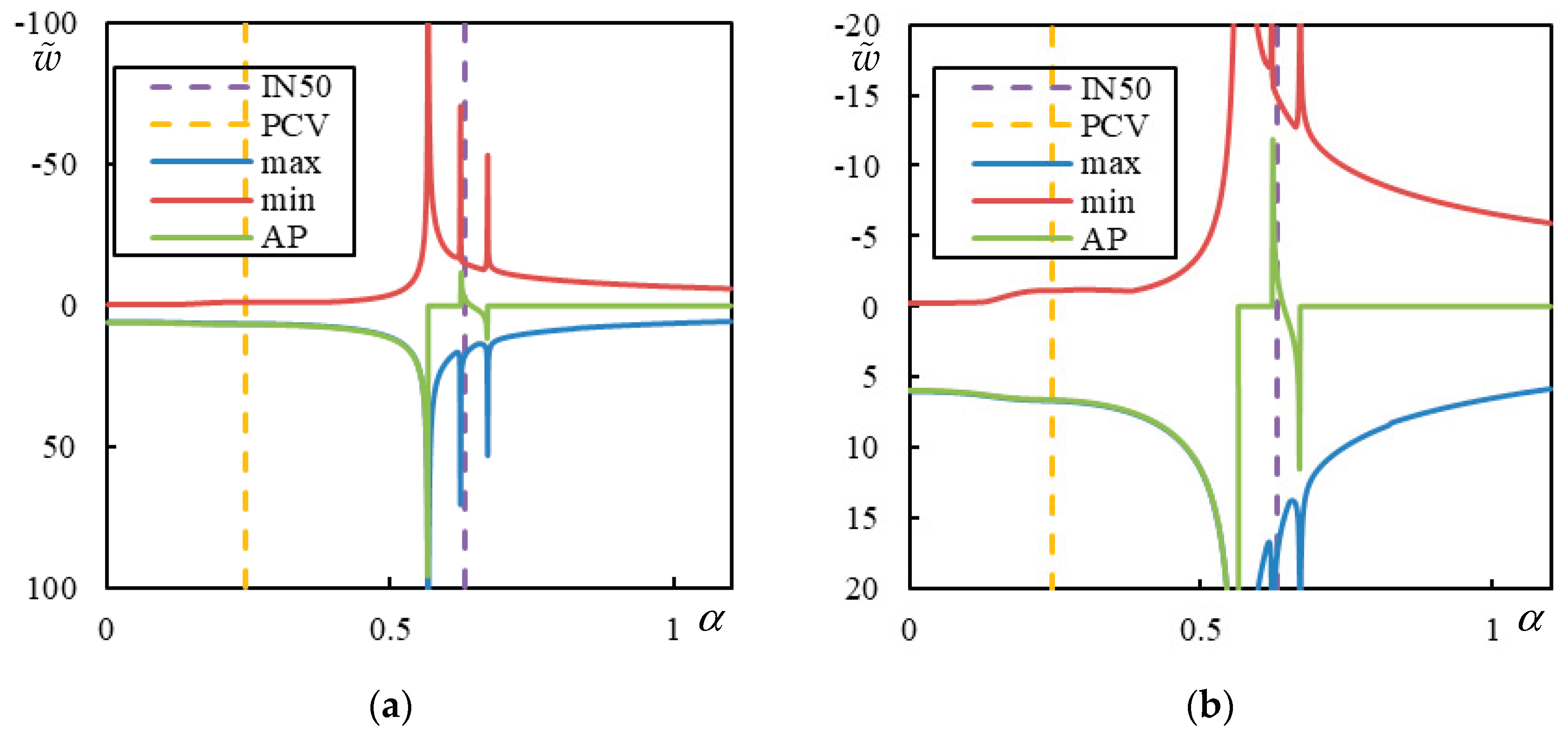

Figure 14.

Parametric analysis (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 14.

Parametric analysis (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

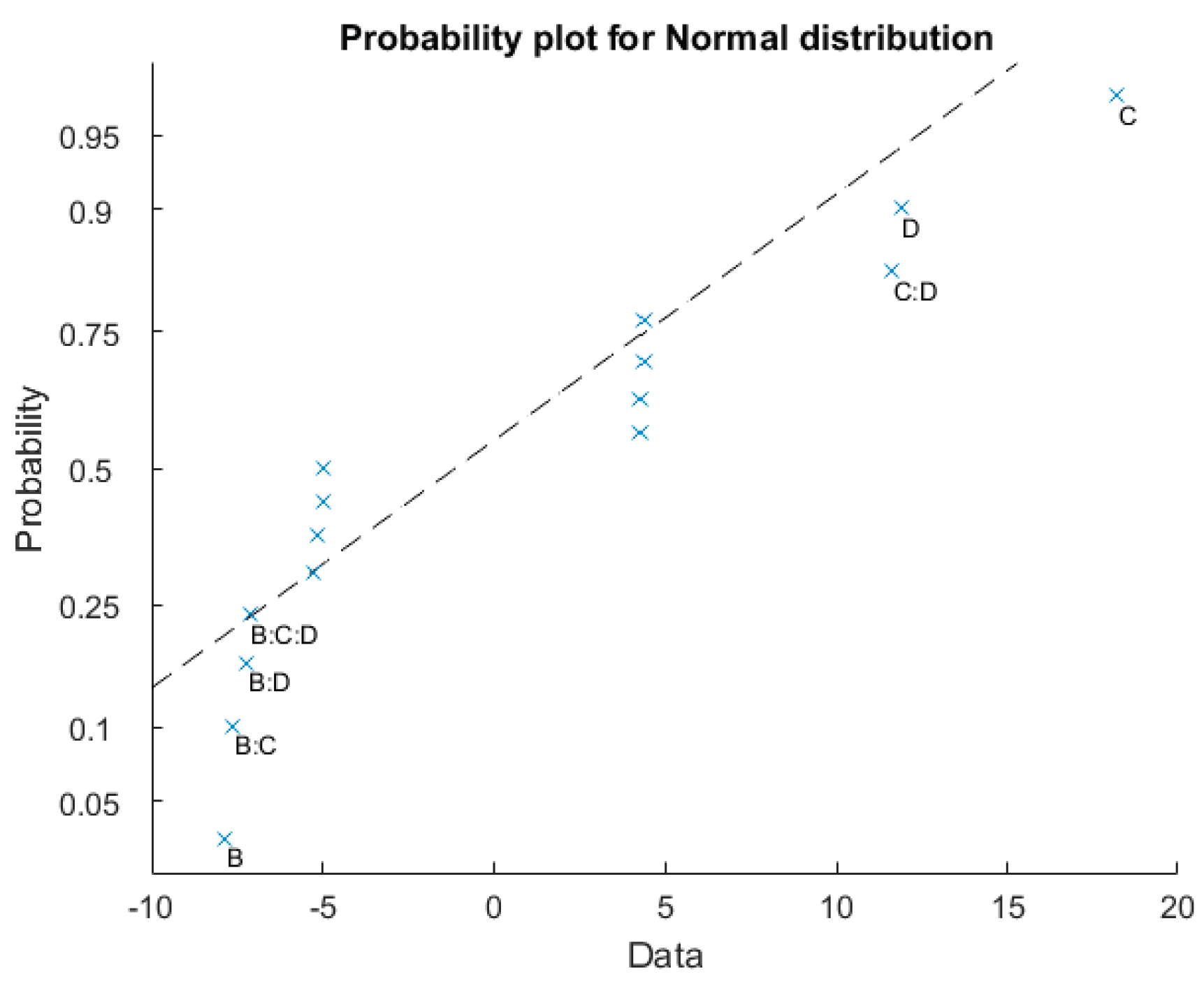

Figure 15.

Probability plot for DOE analysis. As usual, factors are designated A (), B (), C () and D (). Significant effects are indicated in the graph.

Figure 15.

Probability plot for DOE analysis. As usual, factors are designated A (), B (), C () and D (). Significant effects are indicated in the graph.

Figure 16.

Analysis related to determination of PI for , , and . In the legend: “peak” (violet) is PCV; “resonance” (red) is ; “asymptote” is at the lowest asymptote to instability lines (orange-1% damping ); “alpha50” is .

Figure 16.

Analysis related to determination of PI for , , and . In the legend: “peak” (violet) is PCV; “resonance” (red) is ; “asymptote” is at the lowest asymptote to instability lines (orange-1% damping ); “alpha50” is .

Figure 17.

Final outcome of Monte Carlo analysis and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 17.

Final outcome of Monte Carlo analysis and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

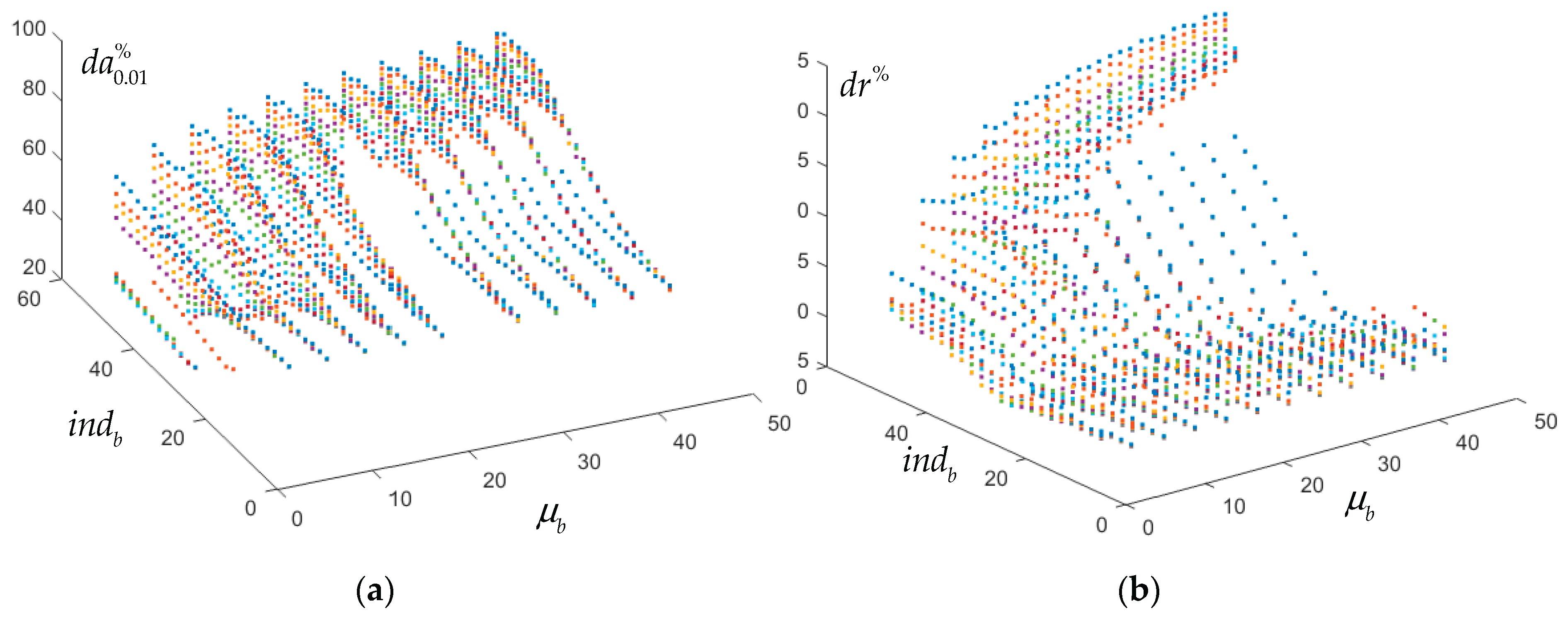

Figure 18.

Parametric search for , , and : (a) preselection according to (b) preselection according to . Different colors correspond to different , with lower values on top.

Figure 18.

Parametric search for , , and : (a) preselection according to (b) preselection according to . Different colors correspond to different , with lower values on top.

Figure 19.

Parametric search for , , and : (a) preselection according to (b) preselection according to . Different colors correspond to different , with lower values on top.

Figure 19.

Parametric search for , , and : (a) preselection according to (b) preselection according to . Different colors correspond to different , with lower values on top.

Figure 20.

Final outcome of parametric search for and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam):, , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 20.

Final outcome of parametric search for and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam):, , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 21.

Final outcome of parametric search for and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 21.

Final outcome of parametric search for and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 22.

Final outcome of parametric search for and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 22.

Final outcome of parametric search for and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 23.

Final outcome of parametric search for and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 23.

Final outcome of parametric search for and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

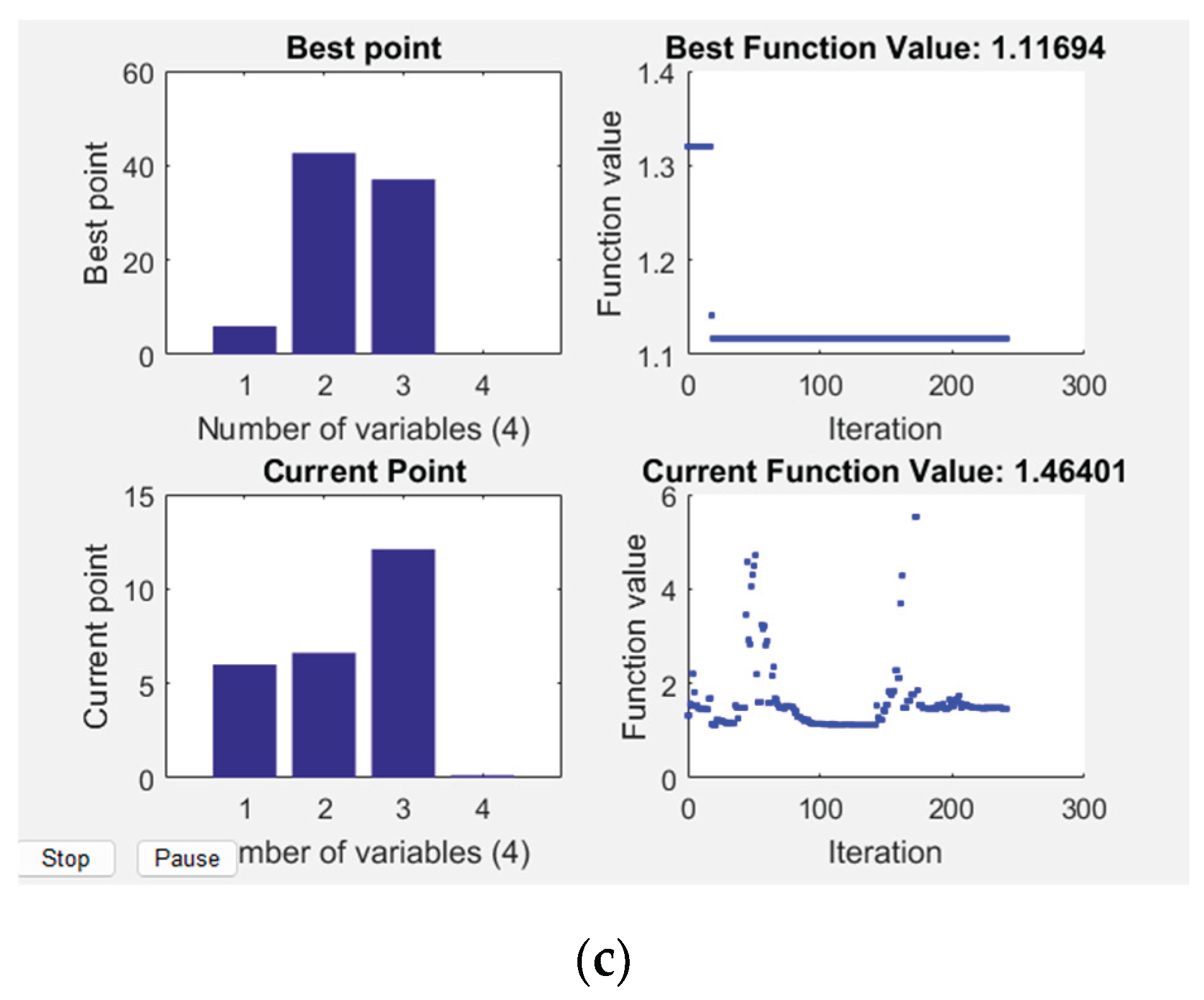

Figure 24.

Summary of different runs of SA: (a) initial set is the best set from MC simulation (5.5244; 44.1292; 44.8870; 0.1111); (b) initial set is the best set from previous simulation; (c) initial set is (4; 15; 30; 0.5).

Figure 24.

Summary of different runs of SA: (a) initial set is the best set from MC simulation (5.5244; 44.1292; 44.8870; 0.1111); (b) initial set is the best set from previous simulation; (c) initial set is (4; 15; 30; 0.5).

Figure 25.

Analysis related to determination of PI for , , and . In the legend: “peak” (violet) is PCV; “resonance” (red) is ; “asymptote” is at the lowest asymptote to instability lines (orange-1% damping ); “alpha50” is .

Figure 25.

Analysis related to determination of PI for , , and . In the legend: “peak” (violet) is PCV; “resonance” (red) is ; “asymptote” is at the lowest asymptote to instability lines (orange-1% damping ); “alpha50” is .

Figure 26.

Final outcome of Simulated Annealing optimization and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , ; and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.

Figure 26.

Final outcome of Simulated Annealing optimization and preselection according to (AP – green, Maximum – blue, Minimum – red displacement over the entire beam): , , ; and . Parts (a) and (b) refer to different -scale. PCV is marked by an orange dashed line and by a violet dashed line.