1. Introduction

In the past few decades, green building technologies (GBTs) have become a vital approach to addressing sustainability challenges by reducing ecological impacts throughout the building’s lifecycle. The integration of ecological principles in civil engineering has its roots in the pro-environment initiatives of the 1960s and was further accelerated by the energy crises of the 1970s. Over time, these principles have become deeply embedded in policies, legislation, scientific research, and educational initiatives aimed at reducing energy consumption in the construction sector. The construction industry is responsible for approximately 40% of global carbon dioxide emissions posing significant environmental impacts due substantial resource extraction, energy-intensive production processes, and excessive waste generation [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The major contributor to the industry's carbon footprint is concrete, which is one of the fundamental and most widely used construction material. This is largely due to its key component, cement, which remains irreplaceable in modern construction and accounts for approximately 8% of global CO₂ emissions [

5,

6]. In addition to that, excavation of aggregates, transportation, and intensive water consumption during concrete production further exacerbate its environmental impact [

7,

8]. Steel is another industrialized construction material that has a significant environmental footprint during its production [

6]. Steel contribution to CO

2 emissions combined with cement amounts to 12% [

9].

The raise of public concern on the negative impacts brought by the construction industry to the environment in recent years has led towards a growing attention from different stakeholders to adopt advanced building mechanisms that reduce carbon emissions in different stages of the building life cycle [

1,

10]. However, promotion and realization of ecological undertakings, assumed on the global scale, are not distributed uniformly. They are more effectively implemented in highly developed countries and less pronounced in the developing economies like Tanzania. Sustainable development in civil engineering, especially in the context of intensified urbanization stimulated by the increasing world population (projected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030 and 9.7 billion by 2050) must be perceived in a pro-environment and pro-human way with a consideration of climate, economy, social and policy related factors [

6,

11,

12].

Green building technologies present a viable solution to equilibrate the increasing demand for construction especially in urban agglomerations while simultaneously mitigating environmental degradation [

13]. Tanzania has already begun to embrace the green building initiatives in order to promote energy efficiency and sustainable use of resources in response to climate change. Green building potential lies in both advanced scientific innovations and traditional low-tech solutions, which offer sustainable and low-carbon alternatives. Integrating simple and traditional construction methods alongside modern technologies can reduce reliance on high-tech materials, creating opportunities for developing countries where large-scale and high-tech green buildings may not be economically viable to a larger extent.

The Tanzania Green Building Council (TZGBC) in cooperation with various international organizations have played a pivotal role in advocating for eco-friendly building designs that incorporate renewable energy sources, water conservation systems, and sustainable construction materials. Despite these efforts, the green building sector in Tanzania faces numerous challenges; however, with continued investment, restructuring of policies together with increased public awareness, the country has a great potential to expand its green building footprint to ensure that urban growth is both sustainable and resilient to climate change [

14,

15,

16]. Thus, this review paper aims to explore the current state and future prospects of GBTs implementation in Tanzania. The continued adoption of green building principles in urban, suburban and rural areas is vital in shaping a more sustainable future for the country.

1.2. Study Area Description

Tanzania is a prominent East African country located along the geographical coordinates of approximately 6.3690° S latitude and 34.8888° E longitude. The country spans an extensive area coverage of 945,087 square kilometers with a variety of topographical and ecological features including coastal lowlands, mountain ranges, valleys and plains together with inland water bodies such as Lake Victoria, Tanganyika and Lake Nyasa. According to the most recent national census conducted in 2022, Tanzania has a total population of more than 62 million people, reflecting a substantial 37% increase from the previous census held in 2012 [

17]. With an average annual intercensal growth rate of 3.2%, Tanzania continues to experience a rapid population expansion which significantly impacts its socioeconomic dynamics as well as urban development [

18]. Tanzania shares its borders with different countries, which creates a rich intercultural connectivity within the East African region (see

Figure 1).

It is bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda and Burundi to the northwest. The western boundary is shared with the Democratic Republic of Congo, whereas Zambia and Malawi are located to the southwest. Mozambique borders it to the south, while the eastern part of the country is bounded by the Indian Ocean which offers an extensive coastline that facilitates trade and tourism. The country has been experiencing unprecedented urbanization rate majorly driven by natural population growth and increased rural-urban migration [

19]. Major urbanized regions in Tanzania include Dar es Salaam which is the country’s economic hub and the business capital, Dodoma which serves as the political capital together with other cities such as Mwanza, Mbeya and Arusha which play a significant role in fostering commerce and tourism [

19].

Figure 1.

Map showing the geographical location of the study area i.e. Tanzania.

Figure 1.

Map showing the geographical location of the study area i.e. Tanzania.

1.3. Methodology

This review is based on desk research approach and literature review as its main methods to assess the current state, challenges and prospects of green building technologies (GBTs) in Tanzania. The review aimed to capture the both global advancements of the green building field and local applications in order to contextualize Tanzania’s green building progress relative to international trends. A review of existing literature was conducted, drawing insights from peer reviewed journal articles, government reports, policy documents and sustainability frameworks. Literature was collected from reputable academic databases such as ScienceDirect, Scopus, Web of Science as well as Google Scholar. The search covered publications within a timeframe of 2010 – 2025 mostly, using keywords such as “green building technologies”, “sustainable construction”, “energy efficiency”, “water management”, “developed and developing countries”. The criteria used in the inclusion of different references were; quality of the peer reviewed articles published on well indexed journals; well-known intergovernmental reports; relevance of GBTs in global and regional contexts as well as language criteria bounded to English. Sources which focused exclusively on unrelated topics or lacking relevance to the green building related field were excluded.

The selection of sources was guided by relevance, credibility and publication recency, so as to ensure the study incorporates the latest and significant perspectives. The data obtained was analyzed through a thematic synthesis approach whereas the key patterns, recurring challenges and emerging prospects were identified and categorized into relevant discussion areas. Comparison was also conducted to assess Tanzania’s green building progress relative to other countries and current trends, providing contextual insights into policy effectiveness, technological advancements and other contextual factors.

2. Concept of Green Buildings

2.1. Definition of Key Terms

2.1.1. Green Building (GB)

The World Green Building Council defines a green building as the structure whose construction, design and operation minimizes the adverse effects on the environment [

20]. The United States Environmental Protection Agency additionally described the concept of green building as the practice of creating structures and using processes that are environmentally responsible and resource-efficient throughout a building's life cycle from siting to design, construction, operation, maintenance, renovation to deconstruction [

21]. Green buildings are not only emphasized to meet environmental standards, but also to minimize energy consumption, improve productivity and promote well-being of their occupants [

22]. A study conducted by [

23] suggested four main pillars of green building which are reduction of the environmental consequences, improvement of health conditions of the inhabitants, long-term return on the investment to the developers, and the sustainable life cycle of the developed structure.

2.1.2. Green Building Technologies (GBTs)

Green building technologies refer to the innovative and sustainable construction techniques, materials, and systems designed to reduce the environmental impact of buildings while improving energy efficiency, resource conservation, and enhancing occupant well-being [

24]. Green building materials (GBMs) are energy-efficient, environmentally friendly throughout their lifecycle, with an increasing potential for reuse or modification [

2,

25]. Energy efficiency involves reducing energy use while maintaining indoor comfort—thermal, air, acoustic, and visual conditions [

26]. As defined by the European Commission [

27], it means using less energy to achieve the same outcome. It includes insulation improvements, passive design, heat recovery, and the use of renewable energy for heating, cooling, and electricity [

28,

29,

30]. Additionally, technologies which promote water efficiency in buildings such as rainwater harvesting systems and greywater recycling systems are also considered as part of the GBTs [

31].

2.2. Green Building Standards in Developed and Developing Countries

2.2.1. Green Building Standards in Developed Countries

In developed countries, green building standards are attributed to factors such as regulatory frameworks, technological advancements, and certification schemes together with economic incentives. In the United States, the government has adopted zoning regulations and building benchmarks to foster the realization of green building objectives [

32]. Regulatory frameworks are considered as the pivotal instruments in advancing green building technologies as shown by the U.S. Energy Independence Act (2007), which mandates a 30% reduction in energy consumption for federal buildings by 2015 and requires new federal buildings to achieve carbon-neutral status by 2030 [

33].

Green building regulatory authorities from different countries have established certification systems so as they can act as intermediary frameworks to assess and recognize buildings that meet sustainable environmental standards. The U.S Green Building Council developed a certification system called Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), which is the most widely used green building certification system globally [

34,

35]. LEED tends to evaluate buildings across key areas such as energy efficiency, water usage, indoor environmental quality, materials selection, and site development process [

36,

37,

38]. A study conducted by [

39] in the U.S. revealed that the pilot buildings using ERVs and HVAC systems achieved 10% higher cost-efficiency compared to other buildings.

Besides that, the UK uses the BREEAM (British Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) certification which assesses performance in energy efficiency, health and well-being, materials used, pollution control, water usage, land use and ecological parameters [

40]. Passive design strategies like building orientation and use of materials with low embodied energy are also key green building strategies in the UK [

41].

In Germany, the DGNB (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen) certification system established by the German Sustainable Building Council tends to evaluate buildings based on environmental, economic, and sociocultural criteria, with emphasis on energy efficiency and CO₂ reduction [

42]. Moreover, In 2018, the European Commission unveiled its strategic long-term vision for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, by outlining how Europe can pave the way towards climate neutrality and establish an economy with net-zero GHG emissions [

43,

44].

In addition to that, the Japanese government has consistently made diligent efforts to promote green buildings through a robust framework of laws, regulations, and policies [

45,

46]. CASBEE (Comprehensive Assessment System for Built Environment Efficiency) established in 2001 by the Japan Sustainable Building Consortium (JSBC), evaluates building’s lifecycle at different stages i.e. pre-design, construction, operation and promote high performance of buildings by taking into account the Japan’s unique urban and climatic conditions [

47,

48]. According to [

49], pilot buildings have incorporated Building Management Systems (BMS), onsite renewable energy sources such as Solar PV panels, double glazed windows, LED lights and rainwater harvesting systems to ensure water is harvested, conserved and used for different purposes.

The Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA) established the Green Star rating system which has played a significant role in certification of different types of buildings in the country [

50]. Similarly to LEED and BREEAM, the Green Star system assess energy efficiency, emission intensity, water efficiency, transport as well as material reuse [

51]. Moreover, Singapore’s Green Mark certification, assesses buildings based on criteria such as energy and water efficiency, environmental protection, indoor environmental quality, as well as the resources utilized [

52].

2.2.2. Green Building Standards in Developing Countries

In recent years, developing countries have made efforts to promote sustainable construction mechanisms through restructuring regulatory frameworks, establishment of building codes and adoption of green building certification systems to ensure that developed structures meet desirable standards. In 2013, the Chinese government introduced Green Building Action Plan so as to significantly accelerate the growth of green buildings [

53]. For instance, Shanghai enacted local legislation requiring all new buildings in the city to adhere to the GB standards [

53]. Additionally, more than 70% of the new public buildings in low-carbon development zones and key functional areas were constructed to meet the two-star standard or higher [

32].

In Vietnam, the Vietnam Green Building Council (VGBC) developed LOTUS, a market-specific green building rating system that mandates investors to implement green measures in new commercial buildings or retrofitted structures, with incentives provided for manufacturers producing green building materials [

54]. Moreover, the Malaysian government has encouraged collaboration between private sector and Non-Governmental Organizations, allowing certified green buildings to apply for tax and stamp duty exemptions [

55].

The Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies (EDGE) certification system, established by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in 2014 has been widely applied in different developing countries especially in Africa to ensure development of resource-efficient buildings [

56]. The Green Buildings Council of South Africa (GBSA) has been using EDGE certification system to assesses energy efficiency, water efficiency, and embodied energy in materials to ensure buildings are cost-effective and environmentally friendly.

To achieve EDGE certification, a building must demonstrate at least a 20% reduction in energy, water, and material impact compared to conventional buildings. A study analyzing 17 EDGE-certified residential complexes in South Africa revealed average reductions of 54% in embodied energy in materials, 31% in water usage, and 29.7% in energy consumption [

56]. Kenya has also shown early growth in green building initiatives, particularly in addressing affordable housing deficits through EDGE-certified projects [

57]. Additionally, Mauritius has also been recognized among countries with certified projects, reflecting a growing commitment to sustainable construction practices across Africa [

58].

In Tanzania, the adoption of green building certification systems is predominantly characterized by the utilization of international frameworks, notably the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) and Singapore's Green Mark. These systems are employed to assess the environmental compliance of construction activities and building materials within the country [

16]. However, the reliance on these foreign standards is accompanied by challenges, primarily due to the absence of clear government policies and regulations mandating the application of green building practices in Tanzania [

15].

Generally, there are more than 40 green buildings certification systems applied in different parts of the world, but the most common ones are LEED, BREEAM, EDGE, DGNB, Green Star, Green Mark, CASBEE as well as Haute Qualité Environnementale (HQE). These certification systems collectively promote sustainable building practices, tailored to regional priorities and context specific environmental goals [

59].

Table 1 below shows the criteria taken into consideration by different Green Building certification systems applied in different parts of the world. Most certification systems have similar criteria but in some instances some criteria are named differently or subjected as a sub-component of a particular criteria. Basically, criteria of each certification system are weighed with different credit points based on the desirable projected impact in building’s performance [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]

.

2.3. Material Solutions

According to [

1], “

people urgently need to use eco-building materials that are in harmony with the ecosystem and meet the requirements of minimal resource and energy consumption, minimal or zero pollution, optimal performance, and maximum recyclability.” Growing awareness of environmental responsibility, along with binding obligations set by international resolutions, has increasingly stimulated research on eco-friendly construction materials. This has led to a growing number of scientific publications, including several review articles [

11,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70].

2.3.1. Traditional and Industrialized Materials

Across many regions, especially in urban areas, construction still depends on conventional materials such as concrete, reinforced concrete, and steel. While they are structurally reliable and widely available, these materials have high environmental costs due to energy-intensive production and resource depletion [

71]. Their use remains central even in buildings that aim for green certification.

To reduce their impact, alternatives such as blended cements with fly ash or ground granulated blast furnace slag are increasingly adopted, in different continent such as Europe, America and Asia. These mineral additives lower carbon emissions and utilize industrial waste which is found in almost every part of the world efficiently [

7]. Another global inevitable trend is the use of recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) as a substitute for natural aggregates. Although RCA can affect concrete quality, proper mix design can help achieve acceptable performance [

70,

72,

73,

74].

In contrast, most of rural and peri-urban construction often uses natural materials like earth blocks, timber, and thatch, which are affordable, locally sourced, and low in embodied energy. In parts of Europe and Asia, traditional materials have been modernized through improved processing or hybrid designs which tends to balance sustainability with performance.

These global examples offer useful insights for countries like Tanzania, where a mix of formal and informal construction practices exists. There is an opportunity to explore the integration of eco-friendly approaches such as cements with mineral additives and upgraded traditional materials within local building practices. This blend could support more sustainable, cost-effective construction while aligning with local needs and available resources.

2.3.2. New Generation Concretes

Recent advancements in concrete technology have introduced high-performance composites that aim to improve durability, strength, and functionality. Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC) reduces the need for vibration during placement, while Self-Healing Concrete automatically seals small cracks over time Self-Cleaning Concrete contributes to aesthetics and helps purify the surrounding air [

75].

Other innovations include fibre-reinforced concretes such as HPFRC (High Performance Fibre Reinforced Concrete); UHPFRC (Ultra-High Performance Fibre Reinforced Concrete), and ECC (Engineered Cementitious Composites), which enhance tensile performance. LiTraCon, which uses optical fibers, allows light transmission while maintaining strength. These materials support more slender, durable, and architecturally unique structures [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80].

Despite their benefits, these concretes are expensive and technically complex, limiting their wide adoption even in some developed countries. For Tanzania, large-scale use may not yet be feasible due to economic and technical barriers. However, awareness of these materials offers a foundation for future adaptation. Pilot applications in different institutional or experimental projects could support a great knowledge transfer and capacity building, informing long-term strategies for sustainable construction.

2.3.3. Recycling Materials in a Contemporary Perspective

Virgin steel, which is the second most energy-consuming construction material, offers a significant sustainability advantage due to its recyclability. Producing recycled steel consumes approximately 60–75% less energy and reduces carbon emissions by 50–65%, while retaining most of its original mechanical properties [

2]. This stands in contrast to recycled concrete, which in most instances requires quality modifications so as to meet structural standards.

Recycling and upcycling help to close the material loop, supporting more environmentally responsible construction. As a result, waste materials are increasingly integrated into green building technologies as innovative and sustainable solutions. Blended cements and concretes with recycled aggregates are generally viewed as greener alternatives, often referred to as "green concretes" or "green cements." However, these terms can be somewhat symbolic, as the production processes still carry environmental impacts [

71].

True green building materials are better defined as those which are developed by using new technologies or derived from biodegradable, bio-based, or readily available eco-friendly resources. For the case of developing countries such as Tanzania, incorporating recycled or natural materials, especially those sourced locally presents a viable strategy to promote low-cost, climate-appropriate construction while contributing to circular economy goals within the building sector.

2.3.4. Innovative Advanced Building Materials

This recently, innovative building materials have started to gain global recognition due to their potential of enhancing energy efficiency and sustainability in construction. High-performance insulation materials such as aerogels and vacuum insulation panels (VIPs), along with coatings, composites, and nanomaterials, are at the forefront.

Aerogels, due to their low density and excellent thermal properties, are increasingly used for insulation in walls, windows, and roofs [

81]. Recent studies have demonstrated cost-effective aerogel production using waste cardboard, which tends to offer both environmental and economic benefits [

1,

82].

VIPs tend to provide excellent insulation in compact spaces, which is ideal for retrofitting buildings where space is limited, and can significantly reduce energy consumption [

83]. Similarly, reflective and low-emissivity coatings tend to enhance building envelopes by minimizing heat gain [

84]. Self-healing composites which are embedded with microcapsules, offer long-term durability and reduced maintenance [

75].

Phase-change materials (PCMs) also tend to store and release heat which aids indoor temperature regulation, especially when integrated into the walls [

74]. Smart materials, including those which are responsive to light and temperature, dynamically adjust to environmental changes. Thus, improves occupant comfort and energy performance [

84].

Moreover, nanomaterials tend to offer promising avenues across insulation, durability, and self-repair functions, though their high cost and limited real-world application, particularly in developing countries, remains to be a great challenge [

2]. Integrating such innovations together with local, eco-friendly materials and technologies like 3D printing offers a viable path forward [

66]. For Tanzania, learning from global applications and gradually adopting these solutions could support sustainable construction and climate-resilience.

2.3.5. Natural Materials

Natural materials are increasingly revisited due to their ecological benefits, such as renewability, low embodied energy, and recyclability. While they may not replace industrial materials, they can complement them, especially in the regions aiming to reduce environmental impact. In rural areas of developing countries, including Tanzania, their use often aligns with the local traditions and construction practices, offering a low-cost and culturally acceptable alternative.

Wood tends to remain as one of the most versatile materials, fulfilling structural and insulating functions. Engineered wood products like cross-laminated timber are gaining popularity for their strength and sustainability [

2]. Careful selection of adhesives and treatments is very essential for maintaining environmental integrity [

3]. Bamboo, which is well known for its rapid growth and low carbon footprint, offers promise in regions where it is native, although its use in urban projects is often limited to niche applications [

85].

In addition to that, cork is another renewable material that is highly valued for insulation and indoor comfort, with increasing use in modern sustainable buildings [

2]. Similarly, straw bale construction which is combined with natural plasters made of clay or lime tends to offer excellent thermal performance, suitable for hot and dry climates like those found in some parts of Tanzania. These materials, when thoughtfully integrated, can support greener and more culturally grounded construction strategies.

It is important to acknowledge that many of these natural materials are rooted in Tanzania’s vernacular architectural traditions. These traditional systems are inherently sustainable, embedded with culture, and cost-effective at the same time, making them particularly suitable for low-income settings. Emphasizing vernacular architecture not only enhances the contextual relevance of green building technologies but also promotes the integration of indigenous knowledge into modern sustainability practices.

2.3.6. Composites Blending Natural, Industrialized and Advanced Materials

Composites that tend to blend natural, industrialized, and advanced materials are gaining renewed attention for sustainable construction. Traditional earth-based composites, such as rammed earth, adobe, and cob, combine soil, clay, and fibers and are still used by over a third of the global population [

86]. These materials offer thermal insulation, durability, and low embodied carbon, making them suitable for rural settings in developing countries like Tanzania [

2].

Modern adaptations include hempcrete (hemp-lime composite) and coconut-wood-based composites, which exhibit superior strength and insulation properties. While promising, their adoption remains limited to areas with access to raw materials and suitable technologies at the same time [

1]. Innovations such as transparent or luminescent wood and nano-enhanced composites show strong potential but are still mostly in experimental phases [

10,

87]. Some research promotes integrating waste materials—like rice husk ash, fly ash, or eggshells into masonry and bricks, in order to reduce pollution while improving thermal comfort [

88]. These low-tech yet effective innovations are particularly relevant for low-rise construction in arid or rural environments.

Natural fibers, such as sisal, hemp, coconut, and palm, are abundant in Tanzania and as well as other developing countries. When processed and integrated into cement, geopolymers, or polymer matrices, these fibers improve insulation and mechanical performance [

89]. Despite the strong resource base and proven benefits, broader application remains hindered by economic constraints, weak policy support, and limited awareness challenges in different developing countries that must be addressed to unlock their full potential.

Table 2 below provides an overview of the discussed material solutions and their relevance in the context of Tanzania.

2.4. Energy Efficiency Aspect

Certification systems like LEED, BREEAM, DGNB, or EDGE treat energy efficiency as a core criterion, assessing factors such as annual primary energy use, share of renewables, energy use intensity (EUI), and CO₂ emissions per m² [

34]. However, a performance gap often exists between projected and actual performance [

90]. New buildings increasingly aim to meet nZEBs or even Positive Energy Building standards [

91,

92].

2.4.1. Technologies to Improve Energy Efficiency

Appropriate selection of construction technology and installation of technical building equipment in both existing and newly designed buildings can lead to a significant reduction in final energy consumption, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and reduction of operating costs. The greatest potential for improving energy efficiency lies in the comprehensive modernization of the existing building stock, particularly in countries where buildings built before modern energy standards predominate [

30,

93]. An integrated approach to retrofitting that includes insulating the building envelope, replacing windows and doors, upgrading heating, ventilation and cooling (HVAC) systems, and implementing energy-efficient light sources, reducing energy demand by up to 50-70%.

2.4.2. Passive Energy Systems

In green buildings, low-exergy renewable sources can partially satisfy heating, cooling, and daylighting needs, allowing for the use of less efficient systems without increasing emissions from fossil fuels. Passive design strategies—central to energy-efficient construction—aim to reduce final energy demand by shaping the architectural form and leveraging natural physical processes. These measures decrease non-renewable energy use, lower CO₂ emissions, and improve the building’s energy balance [

94,

95,

96].

Strategies for supporting heating

In Tanzania, natural strategies supporting heating should be adapted to specific climatic zones, particularly cooler highland regions such as Arusha, Njombe, and Mbeya where indoor thermal comfort may benefit from passive heat gains. These strategies aim to improve energy efficiency by maximizing solar heat gains, storing thermal energy, and minimizing heat loss using cost-effective solutions aligned with local socio-economic conditions. Key strategies include:

South-facing building orientation in colder regions to maximize solar gains during the day.

Functional zoning with day-use rooms (e.g., living spaces, classrooms) on the sunlight side, and storage or utility rooms on the shaded side.

Compact building forms to reduce surface area for heat loss.

Use of thermal mass via locally available materials such as compressed stabilized earth blocks (CSEBs), adobe, or rammed earth.

Passive solar elements like small-scale Trombe walls or thermal storage integrated into walls or floors.

Improved glazing on sun-exposed facades using uPVC or high-performance local glass, complemented by overhangs to avoid overheating.

Strategies for supporting cooling

In Tanzania’s predominantly warm and humid or semi-arid climate zones, natural cooling strategies are essential to ensure thermal comfort while reducing reliance on energy-intensive mechanical systems. These strategies focus on minimizing heat gains from solar radiation and enhancing natural ventilation by leveraging regionally appropriate and affordable solutions. Effective solutions include:

Minimizing glazing on east and west facades and using fixed eaves,

bamboo blinds or locally made shutters.

Applying light-colored, reflective finishes to building exteriors.

Shading with vegetation—e.g., tall trees and deciduous climbers.

Promoting natural cross-ventilation by placing openings on opposing walls.

Enabling night-time ventilation with secure louvers to release heat after sunset.

Using thermal mass from CSEBs, adobe, or rammed earth to buffer temperature swings.

Designing courtyards, shaded verandas, and open floor plans to enhance airflow.

Employing breathable local materials like mud bricks or straw-clay composites.

Strategies for supporting lighting

In Tanzania’s predominantly tropical and subtropical climate zones, natural daylighting is a vital strategy to reduce electricity demand while enhancing indoor comfort and occupant well-being. However, high solar intensity and prolonged sun exposure pose challenges related to glare and overheating, especially in urban and semi-arid regions like Dar es Salaam, Dodoma, and Arusha. Therefore, daylighting strategies in Tanzania must focus on balancing the use of available daylight with passive solar control methods. Suitable approaches include:

Optimizing window placement, particularly on east and west facades, while minimizing exposure from the north.

Using overhangs, bamboo blinds, or louvered shutters to balance daylight with shading.

Integrating courtyards and shaded verandas to allow light into central spaces.

Choosing glazing with appropriate light transmission and solar control properties.

Utilizing high ceilings and bright interior surfaces to enhance light distribution.

In Tanzania’s climatic and economic context, the most effective approach to sustainable building relies on passive design strategies rooted in local materials and construction traditions. Proper building orientation, natural ventilation, thermal mass, shading, and daylighting can significantly lower energy demand while ensuring comfort throughout the year.

Figure 2 below provides an overview of the passive energy strategies suitable for the Tanzania’s climatic and socio-economic context

2.4.3. Active Energy Systems

Modern energy-efficient buildings integrate passive and active systems to optimize energy consumption and incorporate renewable energy sources. Active solutions improve thermal comfort, indoor air quality and significantly reduce primary energy consumption and emissions [

97,

98]. Key technologies include:

Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS), which adjust the operation of the system in real time based on sensor data [

99].

Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery, reducing the demand for heating by up to 80% [

100].

Intelligent lighting systems that respond to motion and daylight.

Renewable Energy Sources (RES)-based heating and cooling systems, such as heat pumps and hybrid configurations.

Building Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) that combine electricity generation with thermal protection; For instance, in Malaysia solar PV technologies have been widely applied in different parts of the country which receive high amounts of solar irradiation such as Kuching, Kuala Lumpur, Taiping and Seremban to generate electricity [

101].

Heat recovery from greywater, recovering 30-60% of energy from domestic wastewater.

The synergy of these systems supports the development of nearly zero-energy buildings (nZEBs), where passive and active strategies enable climate-neutral, resilient construction.

In Tanzania, active energy systems are gradually complementing passive strategies, especially in urban and institutional buildings. While cost and infrastructure barriers limit wide adoption, selected technologies are gaining traction. Active solutions improve thermal comfort, indoor air quality and significantly reduce primary energy consumption and emissions [

97,

98].

Key applicable solutions include:

Solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, increasingly used in both grid-connected and off-grid settings, supported by high solar irradiance [

101].

Intelligent lighting systems (e.g., motion sensors, daylight controls), adopted in commercial buildings to lower energy use.

Heat pumps may have future potential in cooler highland zones, though currently rare.

BEMS and mechanical ventilation with heat recovery remain uncommon due to high costs and limited need for heating [

100]

Heat recovery from greywater is not practiced, but greywater reuse for irrigation and flushing is emerging.

The combination of passive design with selective active systems especially PV and smart lighting offers a feasible path toward energy-efficient, climate-resilient buildings in Tanzania.

2.5. Water Management

Amid climate change, urbanization, and water scarcity, integrated water management is essential in sustainable building design. Green construction increasingly employs solutions to reduce potable water use, minimize runoff, and reuse grey and rainwater. Key systems include rainwater harvesting, greywater recycling, and low-consumption fixtures, which enhance resource efficiency, lower operating costs, and improve climate resilience [

102,

103].

2.5.1. Rainwater Collection and Use

In Tanzania, rainwater harvesting (RWH) systems are increasingly used to supplement unreliable water supply, particularly in rural and peri-urban areas. These systems collect runoff from roofs and other surfaces for non-potable uses such as irrigation, toilet flushing, cleaning, and washing (see

Figure 3). Water is typically stored above the ground or underground tanks and may undergo basic mechanical filtration. Due to seasonal rainfall variability and frequent water shortages, especially in dry regions, RWH offers a low-cost and practical solution to improve water security. It is widely implemented in households, schools, health centers, and local institutions. While advanced filtration systems are rare, even simple setups help reduce potable water demand, wastewater discharge, and stormwater load, thereby supporting sustainable urban water management [

104,

105].

Figure 3.

A schematic diagram demonstrating rainwater harvesting mechanism.

Figure 3.

A schematic diagram demonstrating rainwater harvesting mechanism.

2.5.2. Recycling and Reusing Grey Water

Greywater from showers, washbasins, and laundry is increasingly recognized in Tanzania as a valuable resource for non-potable applications, particularly in water-scarce areas. While advanced treatment systems are rare, simple solutions such as gravel filters or vegetative beds are being piloted in schools, lodges, and institutional buildings. Reused greywater is mainly applied for irrigation, toilet flushing, or outdoor cleaning. These low-tech systems significantly reduce demand for potable water and lessen the burden on inadequate sewage infrastructure. Although heat recovery from greywater remains unfeasible due to technical and economic constraints, broader adoption of basic reuse systems can enhance water efficiency, especially in high-use facilities like hotels and offices [

106].

2.5.3. Water-Saving Systems

Basic water-saving fixtures are gaining relevance in Tanzania as means to address water scarcity and reduce utility costs, particularly in urban and institutional buildings. Common and affordable solutions include low-flow faucets and showerheads, dual-flush toilets, and manual leak detection. Advanced systems—such as sensor-activated fixtures, waterless urinals, or A+++ appliances—remain uncommon due to high costs and limited availability. However, integrating simple, low-cost devices in both new buildings and retrofits can yield substantial water savings without sacrificing comfort, making them a practical step toward efficient water use, especially in areas with intermittent supply [

107,

108].

2.5.4. Green Infrastructure and Local Retention

Green infrastructure offers significant potential for improving urban water management, reducing flood risk, and mitigating heat in densely built environments. From the global perspectives, Nature-based solutions such as rain gardens, green roofs, vegetated swales, and permeable pavements are increasingly recognized for their role in enhancing water retention, erosion control, and microclimate regulation. In sustainable buildings, they also boost envelope energy performance, reduce cooling and irrigation needs, and improve user well-being by enhancing aesthetics and nature access [

107,

109].

In Tanzania, due to high costs and maintenance requirements, green roofs are rare outside institutional or high-end commercial buildings [

107]. More feasible alternatives include community rain gardens or unpaved green zones, which enhance infiltration and reduce runoff in areas lacking formal drainage systems. Permeable surfaces such as gravel paths or interlocking pavers are practical for residential compounds, schoolyards, and public spaces. When integrated with vegetation, rainwater harvesting systems further support local retention and plant irrigation, especially in regions with seasonal rainfall. While advanced, layered green roofs like those in Malaysia are currently beyond the reach of most small developers in Tanzania, broader implementation of low-cost, locally adapted green infrastructure can improve water retention, reduce urban heat stress, and enhance biodiversity, making Tanzanian cities more resilient to climate extremes [

110].

Contemporary urban projects and buildings certified in the BREEAM or LEED systems more often treat green infrastructure as an indispensable component of sustainable design. Proper planning of its placement and integration with technical building systems allow for the creation of resilient, ecological and functional urban environments.

3. Green Buildings Condition in Different Parts of Tanzania

3.1. Existing Condition of Green Buildings in Tanzania’s Urban Environment

The gradual advancement of green buildings in Tanzania's major cities reflects a growing commitment towards realization of country’s sustainable development objectives. Different public, institutional, commercial and residential structures have been developed in cities such as Dar es Salaam, Dodoma, Arusha, Mwanza and Zanzibar Island with a major aim of enhancing energy efficiency, environmental conservation together with occupants’ well-being. A notable successful demonstrative project which exemplifies eco-friendly construction and energy efficient design on the side of residential structures is the Kigamboni Housing Estate (KHE) in Dar es Salaam. This project has incorporated the use of Compressed Stabilized Earth Blocks (CSEBs) and passive design strategies such as optimal building orientation as well as installation of uPVC glass windows with suitable coefficient values to minimize solar radiation while maximizing natural ventilation and daylighting [

111]. This tends to minimize reliance on artificial lighting and mechanical cooling systems, thus lowering the energy consumption [

112].

Residential buildings at KHE also utilize hydro-foam walls made by compressing stabilized soil which offers efficient thermal mass while reducing excessive use of cement in the construction process, that minimizes the pollution levels and waste generation [

112]. Additionally, this project emphasizes on the use of sustainable materials such as bamboo and recycled steel which both aligns with the global green building standards [

111]. The residential sector’s engagement with green building practices is still developing with other private residential premises also trying to integrate some sustainable practices of rainwater harvesting, installation of solar panels and smart ventilation mechanisms to some extents.

Furthermore, the integration of GBTs in Tanzania’s commercial and public buildings is also steadily transforming the urban built environment. Several high profile projects have incorporated sustainable design strategies to enhance energy efficiency, water conservation, indoor environmental quality as well as resource optimization [

113,

114]. The Luminary, is one of the most prominent commercial buildings located in Dar es Salaam which was certified by LEED, receiving a gold rating in the year 2016 [

16,

115]. The structure integrates energy-efficient lighting systems and solar energy solutions which reduces electricity bills by 10% annually [

116]. Furthermore, the building is designed to reduce heat gain and lower cooling demands due to the availability of smart building management system (BMS) which blocks different angles of the sun during the daytime, providing occupants comfort while optimizing energy consumption [

115].

CRDB Bank Headquarters in Dar es Salaam has also incorporated high level GBTs aiming at improving energy performance of daily building’s operation [

14]. The structure utilizes a combination of photovoltaic panels and energy efficient HVAC systems to minimize its carbon footprints [

117]. Additionally, high performance glazing materials as well as automated shading devices have been used to minimize solar heat gain, therefore reducing extreme reliance on air conditioning. Simultaneously, the adoption of intelligent lighting systems with use of motion sensors and LED technology significantly reduces electricity usage [

116]. In order to promote water re-use, this facility also features greywater recycling systems and rainwater harvesting mechanisms to support landscape irrigation and non-potable water applications.

Figure 4 (a) and (b), show The Luminary and CRDB Bank Headquarter, which are among the leading green building structures incorporating advanced GBTs in Tanzania.

Serengeti Breweries, which is one of the leading beverage industries in Tanzania has also integrated sustainable practices within its production facilities. The brewery has incorporated biogas digesters to manage organic waste and generate renewable energy which significantly reduces the reliance on fossil fuels [

118]. Water recycling systems have also been installed in order to improve efficiency in throughout the production process [

118]. Julius Nyerere International Convention Centre (JNICC), which is a public facility and Tanzania’s major conference centres, has incorporated multiple sustainable building features. A combination of energy efficient HVAC systems and LED lighting has been emphasized to enhance the building’s energy performance [

112,

116]. Nelson Mandela African Institute of Science and Technology (NMAIST) in Arusha has also incorporated passive solar systems, rainwater harvesting and energy efficient construction techniques to promote sustainability in institutional buildings [

116]. Similarly, the Bank of Tanzania (BoT) buildings in Dodoma and Dar es Salaam have also incorporated renewable energy solutions, advanced insulation materials as well as modern wastewater treatment systems to minimize environmental impact [

112,

116]. Other successful green buildings structures in Tanzania include Hotel Verde in Zanzibar, PSSSF Tower, TPA, NHC Kambarage and PSPF twin towers in Dar es Salaam [

14].

3.2. Existing Condition of Green Buildings in Tanzania’s Sub-Urban and Rural Environment

In the periphery i.e. sub-urban and rural areas of Tanzania, the adoption of localized GBTs demonstrate an intersection between conventional building practices together with modern sustainability principles. This is largely driven by affordable, resource efficient and climate responsive designs [

119]. The use of compressed stabilized earth blocks (CSEBs) has been widely emphasized in these areas to improve thermal performance in comparison to the conventional concrete or cement bricks [

119,

120,

121,

122]. The use of rammed earth walls made from sand, clay and gravels is also widely used in different houses and touristic hotels found in the periphery [

119]. These walls tend to enhance passive cooling by maintaining standard indoor temperature while reducing reliance on the mechanical cooling systems at the same time [

123]. This is very beneficial particularly in Tanzania’s semi-arid regions which experience excessive heat gain in dry seasons which poses challenges to the occupant’s comfort.

Thatched roofs and locally sourced timber structures have remained to be dominant in many rural areas of Tanzania, offering natural insulation and ventilation advantages. Traditional thatched roofs are usually made from dried grass and palm fronds, which effectively regulate indoor temperatures by preventing heat accumulation, making them suitable for the Tanzania’s warm tropical climate conditions [

124]. They are widely found in local villages and touristic hotels, mostly in Arusha region to provide tourists with eco-friendly atmosphere that appeals to an authentic safari experience.

Figure 5 (a) and (b) demonstrate a traditional rural house and a touristic resort built with timber, bamboo reinforcements and thatched roof.

Green roofs have not been widely adopted in most areas due the construction and management costs accompanied with them, which makes it difficult for small scale developers to go for them as a sustainable alternative for roofing, similarly to what has been observed in Malaysia [

101]. The modernization efforts made in roofing mechanisms, have led towards gradual replacement of thatched roof with corrugated metal sheets [

125]. Although, the latter are more durable than thatched roofs, they significantly contribute to higher indoor temperatures and noise pollution in occurrence of heavy rains [

126]. In this response, GB practitioners are making efforts advocating for integration of thermal insulation layers beneath the corrugated metal roofs by using materials such as bamboo, sisal fibers, solar reflective roofs or recycled textile composites in order to minimize excessive heat transfer towards the indoor environment [

127,

128].

Efficient water management systems is another critical component of localized GBTs in rural and peri-urban areas where access to clean water remains a challenge. Local rainwater harvesting systems such as rooftop catchment setups, storage tanks and first-flush diverters have been very essential to enhance water security [

129]. Numerous households and local institutions such as schools and dispensaries are highly investing in low-cost rainwater collection systems by installing gutters for the conveyance system as well as water distribution facilities to supplement the unreliable piped water supply. On the side of energy efficiency strategies, many households have adopted renewable energy by integrating solar photovoltaic panels for electricity generation which highly minimizes dependence on the national grid [

130,

131,

132]. This provides access to affordable electricity used for different purposes such as lighting, charging, functioning of small appliances and other productive uses such as water pumping and milling grains [

130].

In addition to that, passive design strategies are also being integrated into different peripheral areas of Tanzania by few stakeholders with knowledge about green buildings to enhance indoor comfort and minimize excessive energy consumption [

133]. Optimal building orientation which tends to consider prevailing wind direction and sun exposure, is often being employed so as to improve the natural ventilation and daylighting [

134,

135]. Moreover, cross ventilation techniques have also been incorporated to different households in these areas through strategic placement of windows and air vents to promote airflow and reduce excessive heat buildup within the house [

136]. Simultaneously, the extension of shaded verandas also tend to enhance cooling by preventing direct sunlight penetration into indoor spaces [

133,

135].

4. Contextual Factors of Green Buildings Implementation in Tanzania

The implementation of Green Building Technologies in Tanzania is influenced by various interrelated factors which shape the built environment. These factors include climate conditions, demographic trends, policy frameworks, economic factors, technology transfer, infrastructural mechanisms together with public awareness about sustainable building practices. Understanding these determinants is crucial in evaluating the current status and future prospects of GBT adoption across the country.

4.1. Climate Conditions

Tanzania’s diverse climate plays a significant role in shaping the green building design and construction. The country experiences a wide range of climatic conditions such as humid coastal zones in Dar es Salaam and Tanga to the semi-arid central regions including Dodoma and Singida, as well as highland temperate zones in regions such as Arusha, Njombe and Mbeya [

137]. The variation in climatic conditions, necessitates region specific interventions towards sustainable building practices [

128]. Furthermore, climatic conditions sometimes lead towards the use of locally sourced climate responsive materials which are crucial in providing natural insulation or cooling and minimizes carbon footprints brought by the use of conventional building materials [

120,

121]. In regions with higher temperatures and more intense solar radiation, passive cooling strategies are essential to enhance indoor comfort without relying on mechanical cooling systems. Contrary, in colder areas, materials with higher thermal mass are vital to retain heat especially during the night. Understanding the climate dynamics allows developers to make use of adaptive design solutions which align with both environmental sustainability and local socio-economic conditions.

4.2. Demographic Factor

Rapid population growth and urbanization trends in Tanzania has significantly impacted the demand for sustainable building solutions. The 2022 national census shows that the country’s population is more than 62 million people, with major cities such as Dar es Salaam, Arusha, Dodoma and Mwanza experiencing increased random construction activities to accommodate the growing population [

138]. The housing deficit related challenges in urban areas have led towards the proliferation of informal settlements where sustainable building practices are rarely applied due to economic related challenges [

139]. While several middle and high income households have started to incorporate energy-efficient designs, the adoption of even affordable localized green building technologies for the majority of urban dwellers remains to be a huge challenge [

140]. In rural areas, traditional building techniques that tend to incorporate locally available materials such as mud bricks, thatch, and timber remain prevalent; however, lack of technical knowledge as well as access to improved green technologies limits the potential for more sustainable, durable, and energy-efficient rural housing.

4.3. Policy Framework

The policy framework governing the green buildings in Tanzania remains to be relatively nascent, with ongoing efforts which try to integrate sustainability into building regulations and urban planning policies [

141]. Despite the emphasis made on the Tanzania National Energy Policy (2015) and the National Environmental Policy (2021) regarding the need for energy efficiency, sustainable use of resources and minimized levels of environmental pollution; there are no mandatory regulations, certification systems or green building codes enforcing GBTs across the construction industry [

14,

16]. Instead, voluntary certification systems such as EDGE and LEED have been introduced and applied in some few projects especially in the private sector [

15]. Historically, the government of Tanzania begun to incorporate sustainability criteria in urban development plans, particularly in the implementation of the Tanzania National Urban Development Strategy ad Dodoma’s Smart City Plan under the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development (MLHHSD). However, the enforcement mechanisms are still weak and the incentives for different developers to adopt GBTs such as reduced tax, subsidies and low-interest green financing are very limited [

14,

15,

16,

141].

4.4. Economic Factors

Economic factors also a play a significant role in determining to what extent GBTs can be adopted in Tanzania. In most instances, energy efficiency technologies often require higher upfront investments compared to conventional construction methods [

142,

143]. A larger number of developers tend to prioritize short-term cost savings over long-term sustainability benefits that these technologies could offer, due to financial constraints. In addition to that, limited access to green financing mechanisms such as green bonds or climate funds, hinders the transitioning towards these sustainable construction practices especially to low-income individuals [

14]. Nevertheless, the increase in utilities costs such as electricity and water in urban areas has been gradually driving the demand for designing and construction of resource-efficient buildings. Different public and commercial entities are leading the transition towards green buildings with well-known successful projects such as The Luminary, CRDB Bank Headquarters, NHC Kambarage, JNICC and others incorporating energy efficient designs to reduce operational costs [

16]. Expanding the financial incentives, especially to the small-scale developers, is essential for making GBTs viable across all the sectors of the country’s economy.

4.5. Public Awareness

The level of awareness about GBTs in many developing countries, including Tanzania, is still low especially to the low-income individuals and inhabitants of rural areas. Majority of the people lack appropriate information on the long-term benefits that GBTs could offer them. This is due to limited exposure on the advanced building practices and minimal integration of eco-friendly construction techniques in the country’s educational systems [

14]. This slows down the level of adoption of green buildings to wide extent. Community engagement programs and public awareness campaigns are necessary to ensure that the people are familiar with the benefits of green buildings in the long run [

127]. Moreover, cultural perceptions on the traditional construction methods influence the adoption of GBTs. In sub-urban and rural areas, the use of earth-based materials and naturally ventilated structures aligns with green building practices, but there is a limited recognition of these local methods as part of a formal sustainability framework [

144,

145]. Something interesting is that many rural communities unknowingly practice green building techniques through their ordinary indigenous knowledge, utilizing locally available and environmentally friendly materials that naturally support sustainability. Thus, encouraging the integration of modern technologies with traditional practices bridges the gap between contemporary sustainability efforts and indigenous knowledge.

4.6. Technology Transfer

Access to advanced technologies significantly influences the implementation of GBTs in Tanzania. Modern green building solutions often rely on cutting-edge innovative technologies such as smart energy management systems, automated sensors, renewable energy integration, water recycling technologies and advanced insulation materials [

146]. As a country, Tanzania faces technological gaps due to limited local production capabilities and high dependance on imported green technologies which is expensive. In order to address this challenge, there is a need for technology transfer through fostering international collaboration with global companies and investment in local manufacturing units. An increase in number of the local production units for local sustainable building materials could enhance affordability and encourage the adoption of GBTs even to small scale developers [

84]. Additionally, strengthening research initiatives within country’s academic and technical institutions could play a vital role in fostering homegrown innovations which are tailored to Tanzania’s unique environmental and socio-economic conditions. Without sustained efforts to bridge the technological gap, the widespread implementation of GBTs may remain limited only to high-income developments, which further widens the gap in sustainable housing accessibility.

4.7. Infrastructural Mechanisms

In most cases, the reliable electricity and water supply systems, proper waste management facilities and sustainable transportation networks determines the feasibility of integrating GBTs in both urban and rural areas. Up to this moment, several parts of Tanzania especially in rural and peri-urban areas face unreliable power supply which poses challenges towards the implementation of energy-efficient building technologies [

147]. Frequent power outages in some regions like Kagera, Mara, Simiyu and Mwanza discourages investment in high-tech green solutions such as HVAC systems, smart grid solutions and high performance lighting systems which usually requires a consistent power supply to enhance their better performance [

148]. Additionally, inadequate waste management infrastructure in Tanzania, limits the use of recycled materials in construction. Numerous green buildings worldwide usually incorporate reclaimed timber, recycled metals and repurposed concrete aggregates so as to reduce the environmental impact of construction [

82,

84]. However, the absence of well-organized recycling facilities and waste sorting mechanisms in many parts of the country, hinders the efficient extraction and use of such materials to different construction projects [

149].

5. Discussion

5.1. Effectiveness of the Current Green Building Technologies (GBTs) in Tanzania

5.1.1. Sustainable Construction Materials

The integration of appropriate building materials is pivotal towards realization of the full sustainability potential of green buildings. In the Tanzanian context, where affordability and resource accessibility are key priority aspects, blended strategies that combine natural, industrialized, and advanced building materials is vital. The use of earth-based materials in urban, suburban and rural projects from various regions such as Dar es Salaam, Arusha, Morogoro and Dodoma has strongly demonstrated the feasibility of utilizing locally available low-carbon materials for various sustainable construction purposes.

For instance, the utilization of CSEBs and thatch for roofing has been widely emphasized in different small to medium scale structures for example schools, health centers, people’s residences, traditional restaurants and touristic resorts in different parts of Tanzania such as Tembo Kijani Ecolodge, Karama Lodge as well as Ngorongoro Farm House to provide natural insulation and minimizes carbon footprints [

120,

121]. Comparably, this has also been made widely applicable in the UK and Vietnam whereas the earth-based materials have been utilized in various construction activities as sustainable reinforcement resources with longer life span [

41,

134,

150].

In large-scale commercial and institutional construction projects within urban settings of Tanzania, materials such as recycled steel are being utilized due to their structural reliability and sustainability despite their limited reliable supply and processing in comparison to virgin steel which is widely utilized. The use of engineered wood products such as cross-laminated timber and glued-laminated beams has not been widely commercialized in various parts of Tanzania, but it has started receiving growing interest, especially as a carbon-conscious alternative to concrete.

On the other hand, several advanced materials remain underutilized in the Tanzanian context due to various reasons. For instance, high level technology concretes such as Self-Compacting Concrete, Self-Healing Concrete, and Ultra-High-Performance Fibre-Reinforced Concrete as emphasized by [

75,

79] tend to require precise mixing technologies, quality-controlled environments, and more specialized knowledge, all of which poses significant challenges to the construction industry of Tanzania which is still largely reliant on conventional methods. Moreover, while materials such as aerogels, phase-change materials, and nanomaterial-based composites are highly effective in insulation and energy performance as described by [

81], they tend to remain to be highly expensive to majority of the developers and rarely available through local suppliers. The integration of these materials towards the Tanzanian construction industry, not only requires technology transfer but also investment in specialized infrastructure together with workforce training. Moreover, recent advancements of eco-engineered materials such as cements with fly ash or rice husk ash and emerging bio-based alternatives presents an opportunity to reduce carbon emissions while maintaining durability at the same time [

151,

152].

Apart from that, traditional materials also remain integral to Tanzanian construction industry. Timber, mud bricks, clay blocks, thatch together with strawbales are widely used in rural housing as well as small-scale community projects. However, many of these materials suffer from low durability, lack of standardization, and perception of inferiority [

81,

83]. Integrating them with modern eco-solutions as previously discussed offers a pathway forward. For instance, using strawbales in combination with clay or lime plasters for building insulation purposes can improve indoor thermal comfort while maintaining cost-effectiveness [

2]. Similarly, soil-based composites when reinforced with sisal or coconut fibres tend to significantly improve strength and weather resistance, but both fibres are widely available and yet underutilized in Tanzania’s current construction sector. Changing the narrative by widening the adoption of locally sourced alternatives and use of traditional eco-friendly materials significantly enhances long term sustainability of the Tanzania’s built environment in an affordable way.

5.1.2. Energy Efficiency Aspects

High-profile structures such as The Luminary and CRDB Bank Headquarters in Tanzania have incorporated advanced motion sensor lighting, advanced HVAC systems as well as solar photovoltaic (PV) systems which have definitely led to lower electricity demand and improved thermal comfort [

116]. This minimizes the dependency on conventional electricity from fossil-fuel based power plants, since the on-site power generation offsets electricity consumption from the main grid, thus lowering the peak electricity demand and energy costs. This is similar to the structures erected in various parts of Japan according to the study conducted by [

49] and [

39] in the United States, which have majorly emphasized the role of these GBTs towards enhancing energy efficiency and better insulation performance within the buildings.

Additionally, advanced HVAC systems in these buildings optimize heating, cooling and ventilation in several ways such as through energy recovery ventilation units (ERVs) which tend to capture and reuse heat from exhaust air, which reduces heating and cooling loads within the building. In the same vein, a study conducted by [

39] in the U.S. concluded that similar systems contributed to 10% more energy cost efficiency compared to buildings without HVAC systems. The installed smart thermostats as part of the HVAC systems, tend to learn usage patterns which enables them to adjust temperatures, allowing different areas of the building to have tailored temperature settings which prevents over-conditioning.

When combined, all these energy-efficient technologies significantly lower operational costs, enhance occupants' well-being, and contribute toward sustainability goals. However, despite the successes in these large-scale projects, the reliance on imported technologies remains a major barrier to widespread adoption, especially among low- and middle-income individuals, due to increased costs [

153]. Double-glazed windows, smart HVAC systems and automated lighting controls are not widely manufactured domestically and have high importation costs, making them less accessible for small scale developers particularly in the residential sector [

153]. While large scale commercial projects have incorporated these features, majority of the small and medium scale construction projects lack efficient access to these technologies [

127]. Addressing these challenges through incentives for local manufacturing, technology transfer and heavy investment in renewable energy infrastructure could further enhance the effectiveness in this sector.

Moreover, the integration of solar panels has become increasingly viable, especially in arid and semi-arid regions where solar irradiance is high throughout the year [

154]. Solar photovoltaic (PV) systems provide an effective method for offsetting energy consumption from the main grid and promoting self-sufficiency. In urban projects such as The Luminary, CRDB Headquarters, and the Julius Nyerere International Convention Center (JNICC), PV systems are complemented by Building Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV), advanced insulation materials, energy-efficient glazing, and Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS), illustrating the potential for integrated energy solutions to deliver substantial operational benefits.

Furthermore, passive design strategies are increasingly recognized for their significant contributions to energy efficiency. Solutions such as optimal building orientation, daylighting control, natural ventilation, deep-set windows, light shelves, and reflective surfaces [

95] help to minimize the need for artificial lighting and mechanical cooling. However, despite the proven benefits of these strategies, their adoption remains limited in Tanzania, especially in the private residential sector, with notable exceptions such as the Kigamboni Housing Estate (KHE). The limited integration of such features highlights the need for enhanced awareness and promotion of passive design as a cost-effective means of achieving energy efficiency.

5.1.3. Water Conservation and Recycling

The integration of rainwater harvesting and greywater recycling systems in different structures found in urban and rural areas has majorly contributed to the minimized freshwater consumption and wastage. In Tanzania, these systems are increasingly recognized as practical and sustainable water management strategies, particularly in regions facing seasonal water scarcity and limited access to centralized infrastructure. Rainwater harvesting involves collecting, storing and utilizing the rainwater that falls on the building surfaces such as rooftops or open areas (see Fig. 3). This has also widely observed in Malaysia, whereas even small-scale developers have tried to incorporate RWH systems in their households as one the GBTs as the country experiences high precipitation rates throughout the year [

101,

155].

The whole mechanism of RWH enhances green building performance due to improved water efficiency through reduced demand on municipal water supply, lowered utility costs and self-sufficiency of the building in case of water shortages. On the other hand, the integration of green infrastructure strategies such as rain gardens, permeable pavements, and infiltration tanks as previously emphasized by [

107,

109] remains largely unexplored in Tanzanian context due to factors such as limited technical awareness among developers and insufficient local case studies or pilot projects to demonstrate their feasibility and effectiveness. These nature-based solutions not only mitigate stormwater runoff but also tend to enhance biodiversity, air quality, and urban aesthetics. Thus, integration of these techniques in municipal development plans could help to ease the pressure on aging drainage infrastructure and promote decentralized water retention at the same time.

In addition to that, greywater recycling (GWR) which is one of the key pillars of GBTs has been practically emphasized by Serengeti Breweries as previously discussed in section 3.1, setting a precedent for industrial-scale sustainability in Tanzania [

118]. Since GWR involves treating and re-using wastewater for different non-potable uses instead of discharging it to the sewer, it tends to reduce freshwater consumption by up to 50%. However, there are misconceptions that tend to discourage households and institutions from considering water recycling as a safe and sustainable practice in most of developing countries including Tanzania. Large number of people confuse greywater from sources such as (sinks, showers, and laundry) with blackwater from toilets, leading to hygiene concerns and negative perceptions. Thus, there is lack of public awareness and clarity upon greywater reuse. Additionally, higher upfront cost of installing greywater systems is a barrier to most of the people coming from the low-income communities. Although they tend to offer long-term benefits such as reduced water bills and improved water security, the initial investment in plumbing, treatment units, and maintenance is often unaffordable by the majority, which hinders its integration to many low-income households.

5.2. Policy and Institutional Gaps

As a country, Tanzania lacks a comprehensive and mandatory green building code which hampers the widespread adoption of GBTs. Despite growing awareness, Tanzania still lacks standard guidelines that are tailored to the validation, approval, and scaling of green construction materials, particularly those based on indigenous or recycled content. The existing policies such as Tanzania National Energy Policy (2015) and National Environmental Policy (2021), emphasize on the necessity of promoting energy efficiency and resources conservation, but do not provide the legally enforceable mandates for green construction. The absence of performance benchmarking for the country’s locally sourced alternatives tend to hinder investors’ confidence and public approval. While voluntary certification systems such as EDGE and LEED have been applied in some certain commercial projects, there is no definite nationally recognized green certification framework to standardize the country’s sustainability requirements [

14,

15,

16].

Additionally, as the subsidies, tax breaks and low-interest green financing mechanisms remain limited, the green building investments become less attractive for small-scale developers [

117]. Thus, establishing various financial incentives which are tailored to different income groups, could widen the adoption of GBTs across different sectors. Furthermore, the absence of an integrated urban planning and green building enforcement mechanism often results towards fragmented implementation of sustainable practices. The ministries responsible for construction, urban development and energy policies tend to operate independently, leading to inefficiencies in regulating and promoting GB practices. Therefore, merging and strengthening the mandatory power of TZGBC with legal authority could definitely improve coordination and policy enforcement. Also, national and regulatory bodies should work towards institutional frameworks that recognize and certify context-specific material innovations as part of the mainstream construction practices.

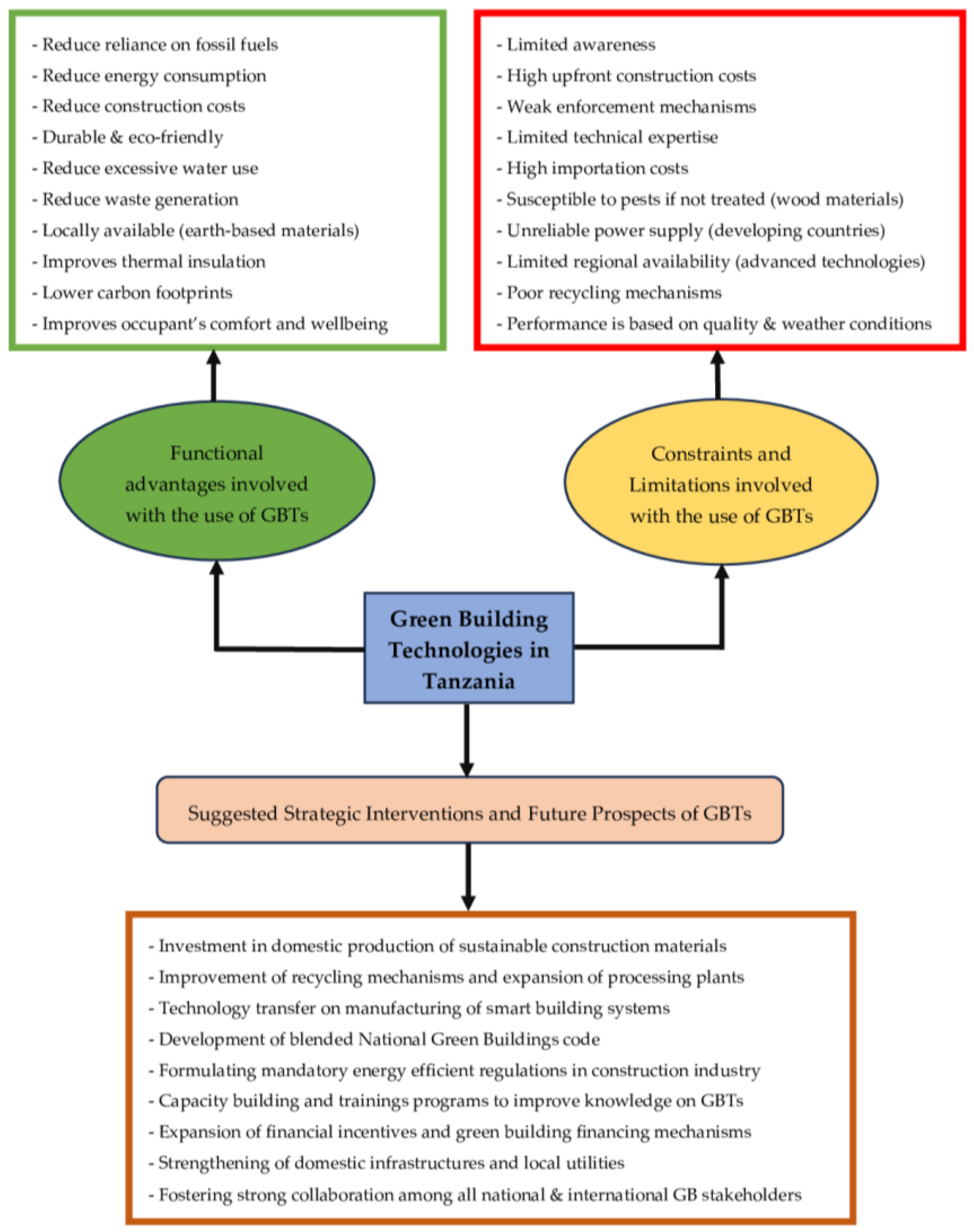

5.3. Future Prospects of the Green Building Technologies in Tanzania